Abstract

Purpose

Hypoxemia during a failed airway scenario is life threatening. A dual-lumen pharyngeal oxygen delivery device (PODD) was developed to fit inside a traditional oropharyngeal airway for undisrupted supraglottic oxygenation and gas analysis during laryngoscopy and intubation. We hypothesized that the PODD would provide oxygen as effectively as high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) while using lower oxygen flow rates.

Methods

We compared oxygen delivery of the PODD to HFNC in a preoxygenated, apneic manikin lung that approximated an adult functional residual capacity. Four arms were studied: HFNC at 20 and 60 liters per minute (LPM) oxygen, PODD at 10 LPM oxygen, and a control arm with no oxygen flow after initial preoxygenation. Five randomized 20-minute trials were performed for each arm (20 trials total). Descriptive statistics and analysis of variance were used with statistical significance of P < 0.05.

Results

Mean oxygen concentrations were statistically different and decreased from 97% as follows: 41 ± 0% for the control, 90 ± 1% for HFNC at 20 LPM, 88 ± 2% for HFNC at 60 LPM, and 97 ± 1% (no change) for the PODD at 10 LPM.

Conclusion

Oxygen delivery with the PODD maintained oxygen concentration longer than HFNC in this manikin model at lower flow rates than HFNC.

Keywords: Continuous oxygen delivery, high-flow nasal cannula, oropharyngeal airway, pharyngeal oxygen delivery device, supraglottic oxygenation

Hypoxemia during apnea is acutely life threatening, especially in patients with unanticipated difficult airway. Thorough examination techniques, difficult airway algorithms, and specialized adjuncts are used to better predict and prepare for critical situations, thereby reducing poor outcomes.1 Furthermore, administration of 100% oxygen via anesthesia circuit face mask prior to induction and intubation prolongs the time to desaturation and permits additional time for intubation.2,3 Adequate oxygen saturation can be maintained even longer using noninvasive, continuous flow oxygen delivered into the nose or mouth of an apneic patient during laryngoscopy and intubation.4–6

High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) delivers warm, humidified oxygen at flow rates up to 60 liters per minute (LPM). However, significant disadvantages limit routine use, including the potential for nasal trauma, the need for specialized equipment (oxygen warmer, humidifier, high-flow wall source, and downstream flow regulator), as well as labor- and time-intensive setup.7 Of note, during the COVID-19 pandemic, high utilization of HFNC led to unprecedented concerns of oxygen supply shortages.8,9 However, high flow rates do not necessarily translate to increased oxygen delivery to the lungs. In fact, prior studies have demonstrated that turbulent flow occurs during open-mouth breathing and leads to admixing of room air entrained through the mouth and oropharynx. This dilutes oxygen administered into the nasopharynx via HFNC and may result in an overall decrease in alveolar oxygen delivery.10 All of these factors contribute additional expense while rapidly consuming oxygen resources due to excessive flow rates.

Continuous oxygen administered by mouth at 10 LPM (through a modified 3.5 oral Ring-Adair-Elwyn [RAE] endotracheal tube resting beside the buccal mucosa) has also been demonstrated to prolong apneic oxygenation.11 Although this is a lower cost alternative to HFNC (both in equipment and oxygen resource utilization), this method delivers oxygen at the level of the cheek, requires preinduction preparation to secure the modified RAE tube to the outer cheek, and may have the same potential for admixing of entrained air as has been demonstrated with HFNC.

Thus, there is a clinical need for a low-cost device that can be easily placed directly above the glottic opening to deliver oxygen and measure expired gas concentration, thus prolonging apneic oxygenation at routine oxygen flow rates. Herein, we present an easily placed, novel pharyngeal oxygen delivery device (PODD) that we hypothesize will maintain oxygen delivery to the lungs as effectively as HFNC in the apneic preoxygenated patient, yet at lower oxygen flow rates.

METHODS

This study received institutional review board exemption and the requirement for written consent was waived because it did not involve human or animal subjects.

PODD design and creation

The PODD was designed using computer-aided design software, such that the shape matched the curvature of a Berman oropharyngeal airway (OPA) and nested securely within the side channel using a coupling mechanism (Figure 1). The internal chamber was divided longitudinally into two separate lumens: a larger diameter lumen for oxygen administration and a smaller diameter lumen with a Luer lock connection for multigas analyzer tubing. After digital design was complete, the shape and dimensions were confirmed by physically reproducing the prototype using 3-dimensional stereolithography printing (Figure 2). Thereafter, graduated sizes of PODDs were produced to correspond with various Berman OPAs for use in adult and pediatric airways.

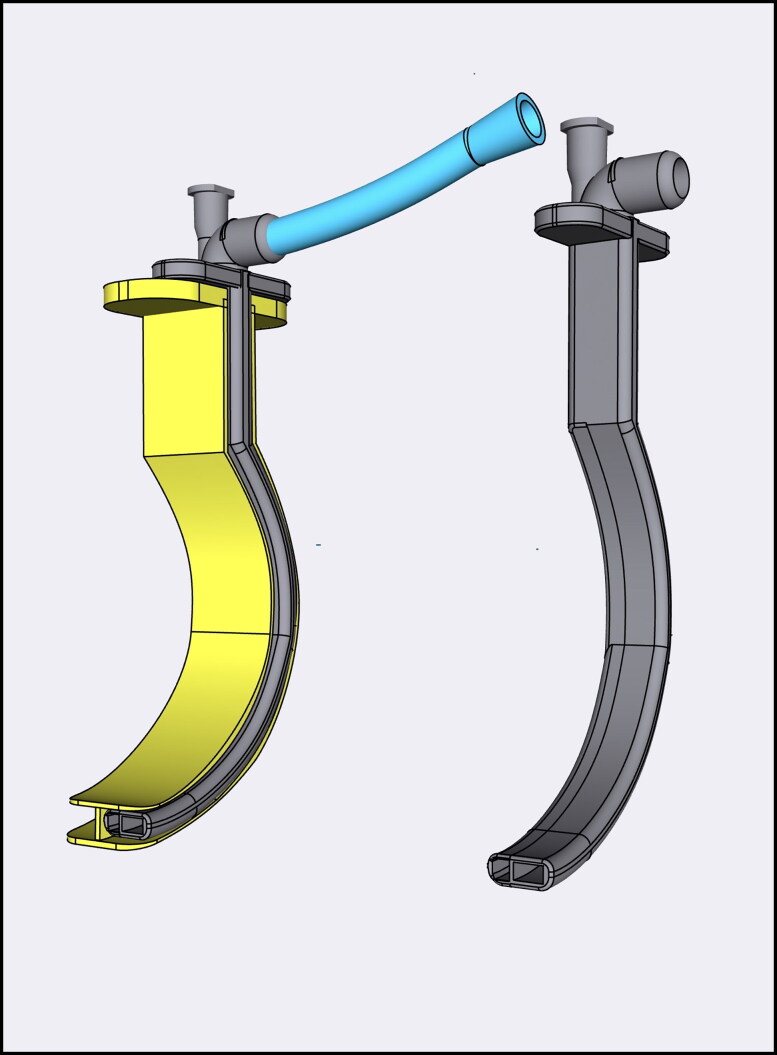

Figure 1.

Pharyngeal oxygen delivery device (PODD) with oxygen tubing coupled with Berman oropharyngeal airway (left) and uncoupled from oropharyngeal airway (right).

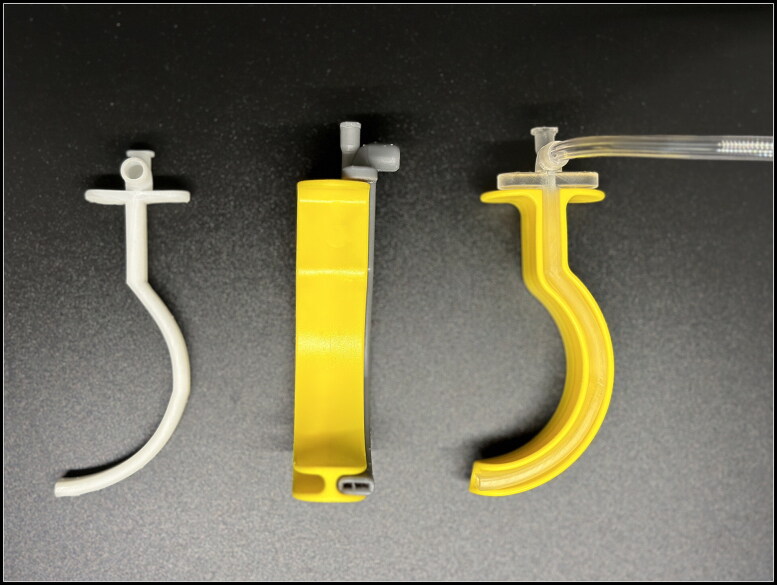

Figure 2.

Side view of pharyngeal oxygen delivery device (PODD) uncoupled from Berman oropharyngeal airway (left); distal view of PODD dual-lumen design coupled with oropharyngeal airway (middle); and side view of PODD with oxygen tubing coupled with oropharyngeal airway (right).

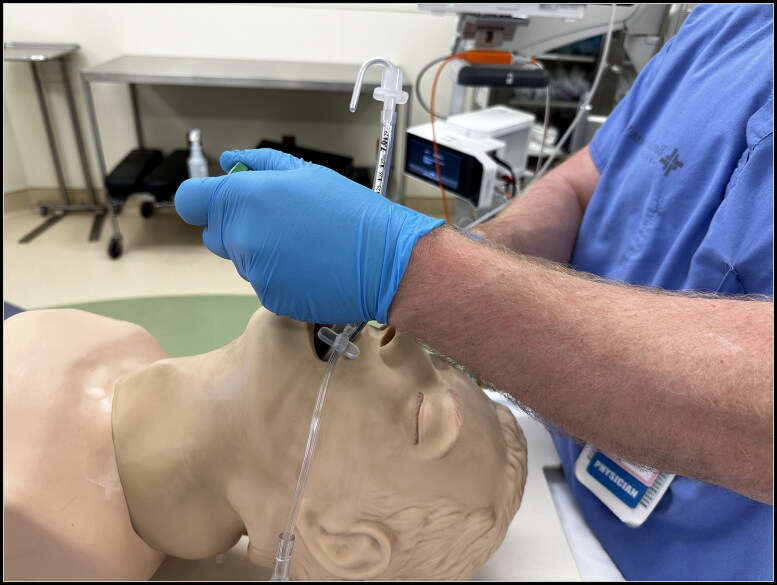

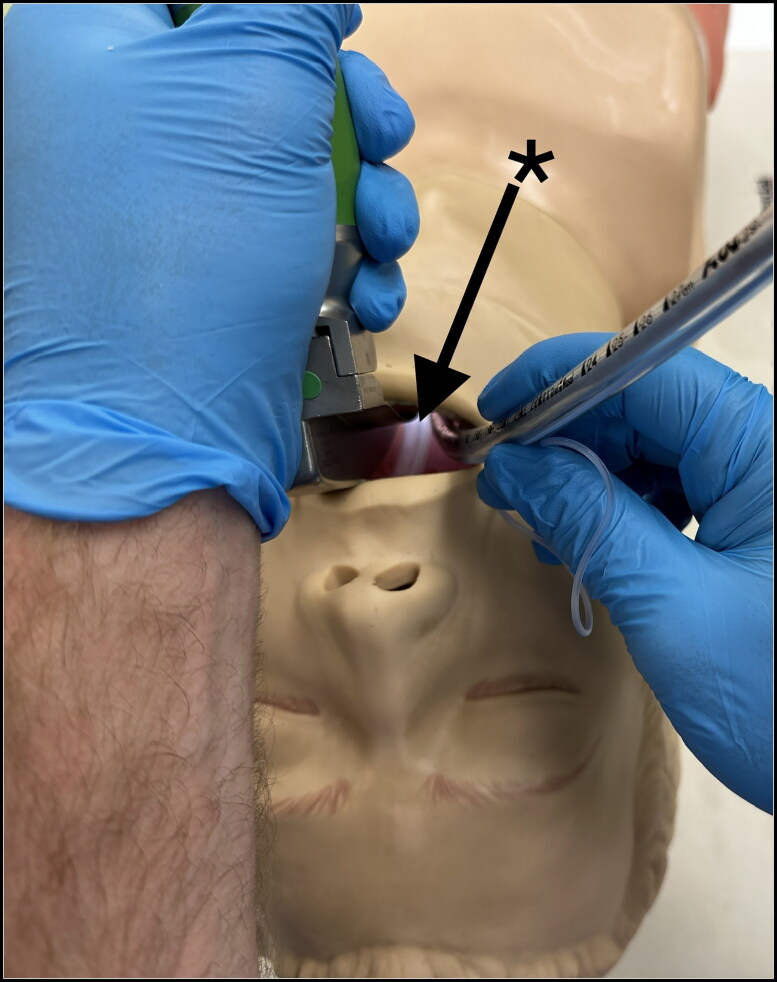

Initial testing of a prototype PODD was performed to validate the structural integrity, functionality, and design in relation to an airway manikin. The PODD was nested within a 90-mm Berman OPA and cohesion of the coupling mechanism was verified by repeatedly connecting and disconnecting the PODD from the OPA. An anatomic airway manikin (Laerdal Airway Management Trainer, Laerdal Medical, Norway) was then used to verify ease of placement, location of distal lumen directly above the glottic opening, and ease of uncoupling within the airway. The uncoupled OPA was then removed, leaving only the PODD in the airway to continuously deliver oxygen during laryngoscopy and intubation (Figures 3 and 4). The PODD remained in place at the left side of the mouth, where its low-profile design provided no interference with laryngoscope blade or endotracheal tube placement in the manikin.

Figure 3.

Side view of uncoupled pharyngeal oxygen delivery device (PODD) at the left side of the mouth during laryngoscopy demonstrating the unobtrusive nature of the device.

Figure 4.

Laryngoscope view of uncoupled pharyngeal oxygen delivery device (PODD)’s low-profile design (asterisk with arrow) that provides no interference with the laryngoscope blade or endotracheal tube placement in the manikin, while continuously delivering oxygen directly above the glottic opening.

Experimental design

The airway training manikin was then retrofitted by connecting each bronchial tube to a separate test lung. The test lung was a closed container with a volume of 2.5 L, providing a physiologic surrogate for an adult functional residual capacity. Multigas analyzer tubing was secured to the base of the lung and connected to a Draeger Perseus A500 anesthesia workstation (Drägerwerk AG & Co. KgaA, Lübeck, Germany). The multigas analyzer sampled lung oxygen concentrations at a rate of 200 mL/min, consistent with physiologic lung oxygen consumption. The manikin’s head remained in a neutral position throughout the experiment. The manikin airway was only manipulated for placement of the PODD and OPA and remained in an open position for all trials.

Experimental procedure

Twenty random trials (five trials in each of the four study arms) were performed in the static manikin model designed to simulate apneic oxygenation (Figure 5). The trials were randomized using a random number generator. Each trial was initiated immediately following preoxygenation to an oxygen concentration of 97% measured at the base of the test lung, as follows:

Figure 5.

Side view of pharyngeal oxygen delivery device (PODD) with oxygen tubing coupled with Berman oropharyngeal airway in manikin model.

HFNC arms: Two HFNC arms were analyzed using 100% oxygen at a flow rate of 20 LPM in one arm and 60 LPM in the second arm. An HFNC device (Fisher & Paykel Healthcare Model MR 810) was connected to the wall oxygen source with a downstream flow regulator. The fresh gas was then warmed and humidified in the manner specified for in vivo use. The HFNC prongs were applied to the manikin’s nares, and oxygen administration via HFNC was initiated immediately following completion of preoxygenation.

PODD arm: The PODD was coupled with a Berman OPA and placed in the manikin’s airway at an oxygen flow rate of 10 LPM. The auxiliary oxygen outlet on the anesthesia machine was used as the oxygen source and flow initiated immediately following completion of preoxygenation.

Control arm: Oxygen therapy was discontinued at the completion of preoxygenation.

The manikin was preoxygenated prior to each trial. Since each trial was independent and selected randomly, the time required for preoxygenation varied based on the ending oxygenation concentration from the previous trial. Regardless, every trial was begun after a uniform oxygen concentration of 97% or greater was established, thereby assuring a consistent starting value. Thereafter, the oxygen concentration resulting from the delivery method designated in each study arm was measured at the base of the test lung and recorded each minute for 20 minutes.

Statistical analysis

Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests determined that the data were not normally distributed. The Friedman test was used to determine if there was a statistically significant difference between the means of the oxygen concentration at each minute between the different study arms and reported as mean and standard deviation. Post hoc pairwise Wilcoxon rank sum tests with a Bonferroni correction were used to assess which arms had different oxygen concentrations. Statistical significance was set at a P value < 0.05.

This manuscript adheres to the applicable CONSORT guidelines.

RESULTS

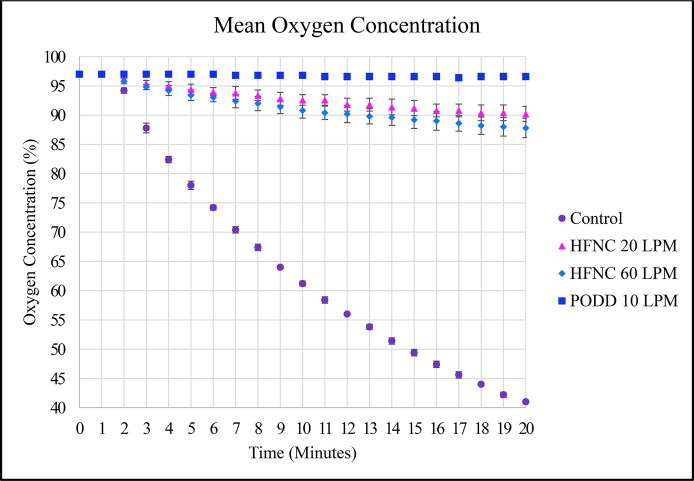

The PODD 10 LPM arm demonstrated no statistically significant drop in oxygen concentration at the base of the test lung during each trial, remaining at 97% ± 1% throughout (Figure 6). The HFNC groups decreased to 90% ± 2% for the 20 LPM arm and to 88% ± 2% for the 60 LPM arm. The control arm dropped from 97% to 41% ± 0%. The mean oxygen concentration across time in the four study arms was significantly different (P < 0.0001).

Figure 6.

Mean lung oxygenation concentration over time during apnea. Note that the pharyngeal oxygen delivery device (PODD) maintains higher oxygen levels than high-flow nasal cannula.

DISCUSSION

A novel pharyngeal oxygen delivery device was designed using low-cost resin materials to meet the clinical need for continuous oxygen delivery directly above the glottic opening during laryngoscopy and intubation. Prototypes were refined and tested using an anatomic airway manikin to validate the simulated apneic oxygenation design as well as the device coupling function with a Berman OPA. Finally, an experimental model was designed to measure the oxygen concentration reaching the base of the test lung with each experimental delivery method. In our simulated apneic oxygenation model comparing the PODD to HFNC and room air control, the PODD was the only device to maintain the baseline oxygen concentration of 97% for the entire test period. All other arms demonstrated reduction in oxygen concentrations beginning within the first 2 minutes, with a nadir after 20 minutes of 90% ± 2% for HFNC 20 LPM, 88% ± 2% for HFNC 60 LPM, and 41% ± 0% for the room air control.

In vivo, apneic oxygenation is made possible by aventilatory mass flow to the lung base wherein alveolar oxygen transfer and carbon dioxide (CO2) uptake from the pulmonary vasculature creates a negative pressure gradient (around 20 cmH2O) between the alveoli and glottic opening.6 Assuming open communication between the lungs and the environment, gases at the pharynx will be pulled toward the lungs. If oxygen delivery to the pharynx is sufficient to create a concentrated oxygen reservoir at the glottic opening, the increased oxygen concentration in the gases pulled toward the lung result in increased alveolar oxygen transfer and extended apnea time.12 This may explain why oxygen concentrations measured at the lung base in this model were higher for the PODD than HFNC since concentrated oxygen delivery was directly at the glottic opening. It is important to note that this manikin model measured oxygen concentration delivered at the lung base, which should directly correlate with tissue oxygen saturation, but does not account for tissue metabolism that occurs in vivo.

Though oxygenation is maintained, significant ventilation does not occur, so arterial CO2 concentration increases (about 12 to 13 mm Hg in the first minute and 2 to 4 mm Hg each minute thereafter).13–15 Thus, prolonged apnea periods may result in hypercarbia, respiratory acidosis, ventricular arrhythmias, and decreased cerebral perfusion despite adequate oxygenation.13,16 The use of HFNC may be associated with a slower rise in arterial CO2, though this has not been consistently demonstrated.6,17,18 It is as yet unclear what role continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) plays in the mechanism of HFNC or if flow through the PODD delivered directly at the pharyngeal opening will result in elevated CPAP and improved washout of CO2 in comparison to HFNC.19,20

Potential clinical applications for the PODD are currently being explored. The PODD delivers oxygen distal to pharyngeal soft tissue, bypassing a common source of airway obstruction in patients with difficult mask ventilation. It can uncouple from an OPA and continue oxygen delivery during laryngoscopy and intubation, providing a bridge of continued oxygenation while securing a difficult airway. If these results are reproduced in vivo, the PODD may add value to the difficult airway algorithm as an apneic oxygenation device that allows additional and prolonged airway management attempts with advanced techniques while avoiding hypoxemia. Finally, the PODD may have utility for passive oxygenation during compressions-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

The PODD has several advantages over other noninvasive oxygen delivery devices. First, it bypasses the friable nasopharyngeal mucosa, making oxygen warming and humidification unnecessary. Furthermore, routine oxygen flow rates through the PODD are sufficient to create a pharyngeal oxygen reservoir, allowing use of standard tubing and oxygen sources (wall outlet or E-cylinder tank). In contrast to buccal devices, the PODD delivers oxygen at the glottic opening, reducing the risk of air admixing, which may reduce the pharyngeal oxygen reservoir. Admixing is postulated to result from turbulence created by high oxygen flow that entrains room air and reduces the effective inspired oxygen concentration.21 In our simulated model, the final mean oxygen concentration in the HFNC 60 LPM arm was lower than the 20 LPM arm, which aligns with this theory and with trends demonstrated in other high-flow simulated apneic oxygenation studies. Finally, the PODD’s simple design makes it ideal for routine use in both out-of-hospital settings by emergency medical personnel and in-hospital settings by practitioners in the emergency department, intensive care units, general hospital floors, and perioperative areas.

Despite multiple advantages, the PODD’s utility is limited in certain clinical settings in vivo. Oral airway devices are not well tolerated in awake patients with intact gag reflexes. Second, malposition of the distal tip can lead to occlusion of the outlet and/or failure to deliver oxygen directly above the glottic opening. Third, the PODD provides substantial oxygenation, but its role in ventilation is unknown. The rise in arterial CO2 concentration during apnea may lead to significant acidosis and adverse outcomes in patients sensitive to hypercarbia, despite adequate oxygenation. Finally, it is not known whether (even at low flow rates) the PODD may cause esophageal insufflation due to the development of CPAP, as HFNC has been demonstrated to do with ultra-high oxygen flow rates.22 The PODD was tested in our manikin model at 10 LPM gas flow rate and at no time during any trial was overt esophageal insufflation noted, but future human studies are necessary to determine safe maximum flow rates. As with HFNC, the PODD will likely require lower maximum flow rates in pediatric patients.

Limitations of this pilot study include a prototype device and manikin model, which cannot perfectly mimic variables that may affect outcomes in vivo. Furthermore, the PODD’s superior performance at delivering higher baseline oxygen concentrations to the manikin lung base may not necessarily translate to superior tissue oxygen saturations in vivo. Although this pilot study demonstrates PODD efficacy at oxygenation, future studies should examine possible risks including mucosal injury and theoretical risks of volutrauma and/or barotrauma, particularly if used simultaneously with a bag valve mask. These risks may be mitigated by limiting the PODD’s use to short periods of time, considering soft materials for construction, and educating operators to avoid high airway pressures if using the PODD in conjunction with positive pressure ventilation.

Despite these limitations, the PODD maintains clear advantages over other noninvasive oxygen delivery devices in maintaining apneic supraglottic oxygenation in unconscious patients. It is low cost (both in terms of equipment and resources necessary) because it uses standard gas flow rates and requires no additional bulky equipment. Oropharyngeal airway placement is considered a basic airway management skill, so airway management practitioners can easily provide supraglottic oxygenation with only minimal additional training to familiarize themselves with proper use of the coupling mechanism. Finally, the PODD’s compact design and ability to connect to any wall oxygen source or oxygen tank makes it ideal for use throughout the hospital and in prehospital or austere environments that rely on portable or finite oxygen supplies. This pilot study demonstrates proof of concept. Our goal after initial publication is to pursue Food and Drug Administration authorization for human subject testing after securing 510(k) similar device classification. Initial testing in human subjects would include testing for function, effectiveness, and side effect or complication profile.

Based on our current data in a simulated apneic oxygenation model, the PODD offers a viable alternative with significant advantages to high-flow nasal cannula for prolonging safe apnea duration during airway management, and future study is warranted.

Disclosure statement

JBH has patent interests in the airway device described herein. All other authors report no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest. Funding sources include departmental support only. No other commercial or noncommercial affiliations, associations, or consultancies exist.

References

- 1.Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Connis RT, et al. American Society of Anesthesiologists practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 2022;136(1):31–81. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nimmagadda U, Salem MR, Crystal GJ.. Preoxygenation: Physiologic basis, benefits, and potential risks. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(2):507–517. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baraka AS, Taha SK, Aouad MT, El-Khatib MF, Kawkabani NI.. Preoxygenation: comparison of maximal breathing and tidal volume breathing techniques. Anesthesiology. 1999;91(3):612–616. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199909000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gleason JM, Christian BR, Barton ED.. Nasal cannula apneic oxygenation prevents desaturation during endotracheal intubation: an integrative literature review. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19(2):403–411. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2017.12.34699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuo HC, Liu WC, Li CC, et al. A comparison of high-flow nasal cannula and standard facemask as pre-oxygenation technique for general anesthesia: a PRISMA-compliant systemic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(10):e28903. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000028903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel A, Nouraei SA.. Transnasal humidified rapid-insufflation ventilatory exchange (THRIVE): a physiological method of increasing apnoea time in patients with difficult airways. Anaesthesia. 2015;70(3):323–329. doi: 10.1111/anae.12923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishimura M. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy devices. Respir Care. 2019;64(6):735–742. doi: 10.4187/respcare.06718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feinmann J. How COVID-19 revealed the scandal of medical oxygen supplies worldwide. BMJ. 2021;373:n1166. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatt N, Nepal S, Pinder RJ, Lucero-Prisno DE, Budhathoki SS.. Challenges of hospital oxygen management during the COVID-19 pandemic in rural Nepal. [published online ahead of print, 2022 Feb 18] Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2022;106(4):997–999. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.21-0669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wetsch WA, Herff H, Schroeder DC, Sander D, Böttiger BW, Finke SR.. Efficiency of different flows for apneic oxygenation when using high flow nasal oxygen application—a technical simulation. BMC Anesthesiol. 2021;21(1):239. doi: 10.1186/s12871-021-01461-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heard A, Toner AJ, Evans JR, Aranda Palacios AM, Lauer S.. Apneic oxygenation during prolonged laryngoscopy in obese patients: A randomized, controlled trial of buccal RAE tube oxygen administration. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(4):1162–1167. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teller LE, Alexander CM, Frumin MJ, Gross JB.. Pharyngeal insufflation of oxygen prevents arterial desaturation during apnea. Anesthesiology. 1988;69(6):980–982. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198812000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frumin MJ, Epstein RM, Cohen G.. Apneic oxygenation in man. Anesthesiology. 1959;20(6):789–798. doi: 10.1097/00000542-195911000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stock MC, Schisler JQ, McSweeney TD.. The PaCO2 rate of rise in anesthetized patients with airway obstruction. J Clin Anesth. 1989;1(5):328–332. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(89)90070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eger EI, Severinghaus JW.. The rate of rise of PaCO2 in the apneic anesthetized patient. Anesthesiology. 1961;22(3):419–425. doi: 10.1097/00000542-196105000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fraioli RL, Sheffer LA, Steffenson JL.. Pulmonary and cardiovascular effects of apneic oxygenation in man. Anesthesiology. 1973;39(6):588–596. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197312000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riva T, Greif R, Kaiser H, et al. Carbon dioxide changes during high-flow nasal oxygenation in apneic patients: a single-center randomized controlled noninferiority trial. Anesthesiology. 2022;136(1):82–92. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000004025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toner AJ. Carbon dioxide clearance during apnoea with high-flow nasal oxygen: epiphenomenon or a failure to THRIVE? Anaesthesia. 2020;75(5):580–582. doi: 10.1111/anae.14848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Shaikh B, Stacey S.. Essentials of Anaesthetic Equipment. 4th ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nielsen KR, Ellington LE, Gray AJ, Stanberry LI, Smith LS, DiBlasi RM.. Effect of high-flow nasal cannula on expiratory pressure and ventilation in infant, pediatric, and adult models. Respir Care. 2018;63(2):147–157. doi: 10.4187/respcare.05728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herff H, Wetsch WA, Finke S, et al. Oxygenation laryngoscope vs. nasal standard and nasal high flow oxygenation in a technical simulation of apnoeic oxygenation. BMC Emerg Med. 2021;21(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12873-021-00407-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arizono S, Oomagari M, Tawara Y, et al. Effects of different high-flow nasal cannula flow rates on swallowing function. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2021;89:105477. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2021.105477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]