Abstract

The updated edition of the German, Austrian and Swiss Guidelines for Systemic Treatment of Gastric Cancer was completed in August 2023, incorporating new evidence that emerged after publication of the previous edition. It consists of a text-based “Diagnosis” part and a “Therapy” part including recommendations and treatment algorithms. The treatment part includes a comprehensive description regarding perioperative and palliative systemic therapy for gastric cancer and summarizes recommended standard of care for surgery and endoscopic resection. The guidelines are based on a literature search and evaluation by a multidisciplinary panel of experts nominated by the hematology and oncology scientific societies of the three involved countries.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Perioperative, Neoadjuvant, Chemotherapy, Immunotherapy, Targeted therapy

Preface

Outcomes of patients with cancer depend highly on access to high-quality care. Part of the established quality-of-care criteria is adherence to evidence-based treatment recommendations. To provide practising oncologists in the three German-speaking countries in Europe, comprising a population of approximately 100 million inhabitants, with up-to-date evidence-based guidelines for patient care, the scientific German, Austrian, and Swiss societies of hematology and oncology nominated a multidisciplinary group of experts to revise consensus-based oncology treatment guidelines based on available scientific evidence. This process is coordinated by the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO). Here, we report on the treatment recommendations from the latest version of the multidisciplinary guidelines for gastric cancer (Onkopedia), finalized in August 2023. This article focusses on locally advanced and metastatic stages (IB-IV). In summary, systemic perioperative chemotherapy is recommended as a mainstay of treatment for patients presenting with localized gastric cancer (stages IB-III). In stage IV gastric cancer patients, treatment goals are palliative in most patients. Sequential lines of chemotherapy have shown to provide the best chances for prolonging patients’ survival, providing symptom control and lead to a better maintenance of quality of life. The assessment of tumor tissue for the expression of programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1), human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) and DNA mismatch repair (MMR) enzymes informs the recommendation for complementing systemic treatment with PD-1-directed immune checkpoint inhibition or HER-2-directed targeted treatment.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Initial diagnosis

Endoscopy is considered the most sensitive and specific diagnostic method. Using high-resolution video-assisted endoscopy, it is possible to detect even discrete changes in color, mucosal surface, and architecture of the gastric mucosa. Endoscopic detection of early lesions can be improved by chromoendoscopy.

The aims of further diagnostics are to determine the stage of the disease and to guide therapy, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Diagnostic procedures and staging in gastric cancer

| Investigation | Note |

|---|---|

| Physical examination | |

| laboratory (blood) | Blood count, liver and kidney function parameters, coagulation, tumor markers (CEA, CA 19–9, CA 72–4) |

| Endoscopy upper gastrointestinal tract | Optional addition of chromoendoscopy |

| Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)1 | For therapy planning in case of localized disease |

| Computed tomography of thorax, abdomen, and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast media | For visualization of locoregional and distant tumor spread |

| Abdominal ultrasound | Complementary to computed tomography |

| Laparoscopy, if indicated plus cytology2 | In cT2/cT3/cT4 without evidence of other distant metastases, to detect/exclude peritoneal metastasis |

1see Chapter 1.1.3.1

2Laparoscopy with cytologic examination of the lavage samples helps to detect clinically occult metastasis to the peritoneum in locally resectable tumors. The detection of macroscopic peritoneal metastasis has immediate implications for treatment planning [87]. Cytologic evidence of malignant cells in the lavage samples is an unfavorable prognostic factor, but—outside of clinical studies—has no definite impact on treatment recommendation to date. Laparoscopically abnormal findings are more frequently found in T3/T4 classified tumors [88]

Histology and subtypes

Histologic diagnosis of gastric cancer should be made from a biopsy, which is evaluated by two experienced pathologists [1].

Laurén classification

Histologically, gastric cancer is characterized by a strong heterogeneity, as several different histological features may be present in one tumor. Over the past decades, histologic classification has been based on the Laurén classification [2]:

Intestinal type, approximately 54%

Diffuse type, approx. 32

Indeterminant, approx. 15%

The diffuse subtype is found more in women and people of younger age, while the intestinal type is more common in men and people of older age and is associated with intestinal metaplasia and Helicobacter pylori infection [3].

World Health Organization (WHO) classification of gastric cancer

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification distinguishes four definitive types of gastric cancer [4].

Tubular

Papillary

Mucinous

Poorly cohesive (including signet ring cell carcinoma).

The classification is based on the predominant histologic pattern of the carcinoma, which often coexists with less dominant features or other histologic patterns.

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) classification

Molecular genetic studies divide gastric cancer into molecular subtypes based on studies of the genome, transcriptome, epigenome, and proteome. The most popular molecular subtyping according to TCGA distinguishes four subtypes [5]:

Chromosomal instability—CIN

Epstein–Barr virus-associated—EBV

Microsatellite instability—MSI

Genomically stable—GS

This classification currently has limited impact on treatment selection.

Stages and staging

TNM staging

The classification of the extent of the primary tumor and metastasis is based on the UICC/AJCC TNM criteria [2, 4, 6]. Since January 1, 2017, the 8th edition has been used in Europe [4]. The TNM criteria are summarized in Table 2, and the staging is summarized in Table 3.

Table 2.

UICC-TNM classification of gastric cancer [4]

| Classification | Tumor |

|---|---|

| T | Primary tumor |

| T1 | Superficial infiltrating tumor |

| T1a | Tumor infiltrating lamina propria or muscularis mucosae |

| T1b | Tumor infiltrating submucosa |

| T2 | Tumor infiltrating muscularis propria |

| T3 | Tumor infiltrating subserosa without invasion of visceral peritoneum |

| T4a | Tumor penetrating subserosa (visceral peritoneum) |

| T4b | Tumor infiltrating adjacent structures |

| N | Regional lymph nodes |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastases |

| N1 | Metastases in 1–2 lymph nodes |

| N2 | Metastases in 3–6 lymph nodes |

| N3a | Metastases in 7–15 lymph nodes |

| N3b | Metastases in 16 or more lymph nodes |

| M | Distant metastases |

| M0 | No distant metastases |

| M1 | Distant metastases or positive peritoneal cytology |

Table 3.

Classification of tumor stages [4]

| UICC stage | Primary tumor | Lymph nodes | Distant metastases |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| IA |

T1a T1b |

N0 N0 |

M0 M0 |

| IB |

T2 T1 |

N0 N1 |

M0 M0 |

| IIA |

T3 T2 T1 |

N0 N1 N2 |

M0 M0 M0 |

| IIB |

T4a T3 T2 T1 |

N0 N1 N2 N3 |

M0 M0 M0 M0 |

| IIIA |

T4a T3 T2 |

N1 N2 N3 |

M0 M0 M0 |

| IIIB |

T4b T4a T3 |

N0/1 N2 N3 |

M0 M0 M0 |

| IIIC |

T4b T4a |

N2/3 N3 |

M0 M0 |

| IV | Any T | Any N | M1 |

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is particularly suitable for determining the clinical T category, as it can best visualize the different layers of the gastric wall. EUS should, therefore, be part of primary staging in a patient with a curative therapeutic approach.

The following characteristics serve to identify malignant lymph nodes on CT slice imaging [7]:

Diameter ≥ 6–8 mm (shorter axis) in perigastric lymph nodes

Round shape

Central necrosis

Loss of the fat hilus

Heterogeneous or enhanced contrast agent uptake

The sensitivity of CT for lymph node staging is variably estimated at 62.5–91.9% in systematic reviews [8].

EUS improves the accurate determination of the T and N categories and can help determine the proximal and distal margins of the tumor. EUS is less accurate for tumors of the antrum. EUS is considered more accurate than CT in diagnosing malignant lymph nodes.

Signs of malignancy on EUS include [9]:

Hypoechoic

Round shape

Blurred demarcation from the surrounding area

Size in the longest diameter > 1 cm

Therapy

Therapy structure

Multidisciplinary planning is required for any initial treatment recommendation. It should be developed in a qualified multidisciplinary tumor board.

Core members of the multidisciplinary board include the following disciplines: Visceral Surgery, Medical Oncology, Radiation Oncology, Gastroenterology, Radiology and Pathology. Whenever possible, patients should be treated in clinical trials.

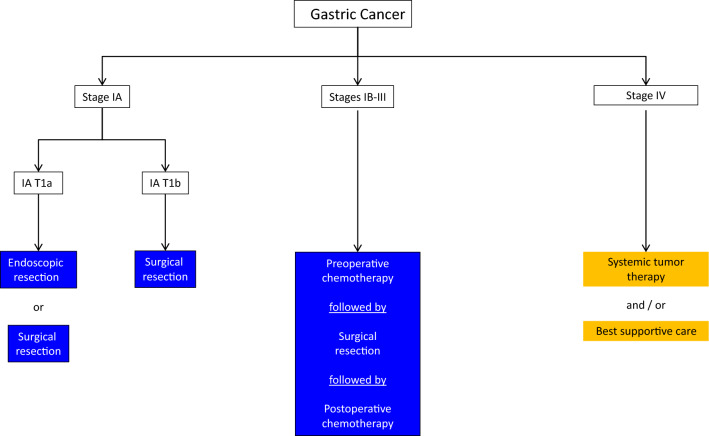

Therapy is stage adapted. A treatment algorithm for the stage-adapted management of gastric cancer is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for stage-adapted management of gastric cancer

Stage IA—T1a

Since the probability of lymph node metastasis in mucosal gastric cancer (T1a) is very low, endoscopic resection (ER) may be sufficient [10]. If histopathologic workup after endoscopic resection reveals that tumor infiltration extends into the submucosa (T1b), surgical resection with systematic lymphadenectomy should be performed, as lymph node metastases may already be present in up to 30% of cases.

Gastric cancers classified as pT1a cN0 cM0 should be treated with endoscopic resection, considering the adapted Japanese criteria [1, 11]. A (limited) surgical approach is an alternative.

Perioperative or adjuvant chemotherapy is not indicated for stage IA (T1a) patients.

Stage IA—T1b

For stage IA gastric cancer with infiltration of the submucosa, the risk of lymph node metastases is 25–28%. The 5-year survival rate is 70.8% for all stage IA in the SEER database [12], and the cancer-specific survival rate at 10 years is 93% in the Italian IRGGC analysis. Therapy of choice in stage I (T1b category) is radical surgical resection (subtotal, total, or transhiatal extended gastrectomy). Limited resection can be recommended only in exceptional cases due to the imprecise accuracy of pre-therapeutic staging.

A benefit from perioperative or adjuvant chemotherapy has not been established for stage IA (T1b) patients.

Stage IB—III

In stage IB—III, resection should consist of radical resection (subtotal, total, or transhiatal extended gastrectomy) in combination with D2- lymphadenectomy. Subtotal gastrectomy can be performed if safe free tumor margins can be achieved. The previously recommended tumor-free margins of 5 and 8 cm for intestinal and diffuse tumor growth types, respectively, are no longer accepted. The scientific evidence for definitive recommendations is low. A negative oral margin in the intraoperative frozen section is crucial.

Perioperative chemotherapy with a platinum derivative, a fluoropyrimidine, and an anthracycline significantly prolonged overall survival in patients with resectable gastric cancer in the MAGIC trial [13]. In the French FNCLCC/FFCD multicenter study, perioperative chemotherapy with a platinum derivative and a fluoropyrimidine without anthracycline showed a comparable effect size on improving survival [14]. Currently, neither chemotherapy regimen is the first choice.

Treatment according to the FLOT regimen (5-fluorouracil/folinic acid/oxaliplatin/docetaxel) further improved progression-free survival (hazard ratio, HR 0.75) and overall survival (HR 0.77) in patients with stage ≥ cT2 and/or cN + compared with therapy analogous to MAGIC. The relatively higher efficacy of FLOT was shown to be consistent across relevant subgroup analyses such as age, histology, and tumor location. The rate of perioperative complications was comparable [15].

For patients with gastric cancer ≥ stage IB who received resection without prior chemotherapy (e.g., due to misdiagnosed tumor stage prior to surgery), adjuvant chemotherapy may be recommended.

In HER2-positive tumors, a benefit from combining perioperative chemotherapy with a HER2 antibody in the perioperative setting in terms of overall survival has not been proven, and therefore cannot be recommended outside of clinical trials. The AIO-PETRARCA phase 2 study showed a higher histopathologic remission rate when FLOT chemotherapy was combined with trastuzumab + pertuzumab and a trend in favor of better progression-free and overall survival [16]. These data require validation in larger and independent cohorts.

In microsatellite instability (MSI-H) localized gastric carcinoma, the efficacy of perioperative chemotherapy, based on retrospective data analyses [17], has been controversially discussed. However, more recent data from the DANTE trial show that complete and subtotal tumor remissions can be achieved with FLOT chemotherapy even in MSI-H subtype gastric carcinomas [18]. Thus, according to the current status, perioperative chemotherapy with the FLOT regimen remains indicated for MSI-H gastric cancers if tumor response is pursued. The FFCD-NEONIPIGA phase 2 study showed a high histopathologic remission rate after 12 weeks of therapy with nivolumab + ipilimumab without chemotherapy in resectable MSI-H cancers [19]. Data require validation in larger and independent patient cohorts.

After R1 resection, adjuvant radiochemotherapy may be considered.

Stage IV

The aim of therapy is usually non-curative. The first priority is systemic drug therapy, supplemented in individual cases by local therapeutic measures. Active symptom control and supportive measures such as nutritional counseling, psychosocial support, and palliative care are an integral part of treatment. The prognosis of patients with locally advanced and irresectable or metastatic (pooled here as "advanced") gastric cancer is unfavorable. Studies evaluating the benefit from chemotherapy have shown a median survival of less than 1 year [20]. However, there is evidence that chemotherapy can prolong the survival of patients with advanced gastric cancer compared to best supportive therapy alone and maintain quality of life longer [21].

Systemic tumor therapy

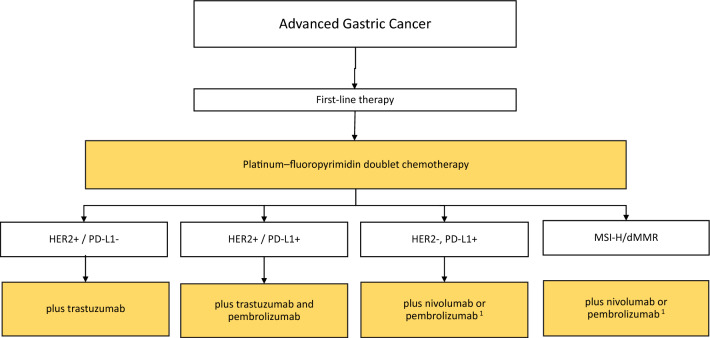

The current recommended algorithms for drug therapy of patients with advanced gastric cancer are shown in Figs. 2, 3, and 4.

Fig. 2.

Algorithm for first-line therapy of advanced gastric cancer. 1Nivolumab is approved in Europe for PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5 according to Checkmate-649; pembrolizumab is approved in Europe for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and esophago-gastric junction for PD-L1 CPS ≥ 10 according to Keynote-590. Positive phase III trial results in patients with PD-L1 CPS-positive gastric cancer were also reported from Keynote-859 and subgroup analyses from several first-line studies (Checkmate-649, Keynote-062, Keynote-859) show benefit for nivolumab or pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy in patients with MSI-H/dMMR tumors

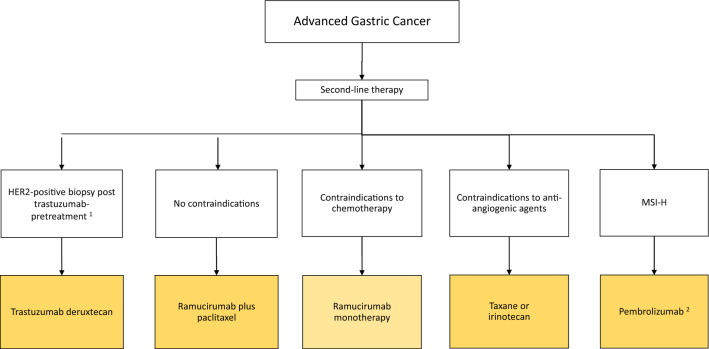

Fig. 3.

Algorithm for second-line therapy of advanced gastric cancer. 1Since many tumors lose HER2 overexpression after trastuzumab failure, reassessment of HER2 status using a fresh biopsy is recommended prior to second-line trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) therapy. 2Pembrolizumab in second line for MSI-high advanced gastric cancer is not recommended when immunotherapy was administered in first-line treatment

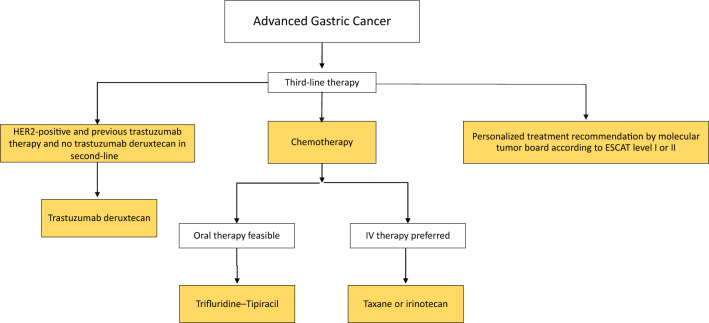

Fig. 4.

Algorithm for third-line therapy of advanced gastric cancer. 1According to the Destiny Gastric 01 study, re-testing of HER2 status is not mandatory for third-line T-DXd therapy, 2 if not administered in second-line treatment

First-line chemotherapy, molecular targeted therapy, and immunotherapy

Chemotherapy

The standard of care for first-line chemotherapy of advanced gastric cancer is a platinum–fluoropyrimidine doublet. Oxaliplatin and cisplatin are comparably effective, with a more favorable side effect profile for oxaliplatin. This may contribute to a trend toward better efficacy, especially in patients > 65 years [6, 22]. Fluoropyrimidines can be administered as infusion (5-FU) or orally (capecitabine or S-1). Oral fluoropyrimidines are comparably effective to infused 5-FU [23–26]. Capecitabine is approved in combination with a platinum derivative and has been studied with both cis- and oxaliplatin in European patients. S-1 is established as a standard of care in Japan and approved in Europe for palliative first-line therapy in combination with cisplatin. Infused 5-FU should be preferred over oral medications in patients with dysphagia or other feeding problems. In elderly or frail patients, results of the phase III GO-2 trial support a dose-reduced application of oxaliplatin–fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy (to 80 or 60% of the standard dose from the beginning), resulting in fewer side effects with comparable efficacy [27].

The addition of docetaxel to a platinum–fluoropyrimidine combination (three-weekly DCF regimen) improved radiographic response rates and prolonged overall survival in a historical phase III trial, but also resulted in significantly increased side effects [28]. Other phase II trials examined modified docetaxel–platinum–fluoropyrimidine triplets and showed reduced toxicity compared with DCF in some cases [29–32]. However, the higher response rate of a triplet (37% vs. 25% [28] does not translate into prolonged survival in recent trials, which included effective second-line regimens. In the phase III JCOG1013 trial, patients with advanced gastric cancer received either cisplatin plus S-1 or cisplatin plus S-1 and docetaxel. There were no differences in radiographic response, progression-free survival, or overall survival [33]. Therefore, with increased toxicity and uncertain impact on overall survival, no recommendation can be made for first-line docetaxel–platinum–fluoropyrimidine therapy, so that a platinum–fluoropyrimidine doublet remains the standard approach. In individual cases, e.g., when fast tumor regression is urgently required, first-line therapy with a platinum–fluoropyrimidine–docetaxel triplet may be indicated.

Irinotecan-5-FU has been compared with cisplatin-5-FU and with epirubicin–cisplatin–capecitabine in randomized phase III trials and showed comparable survival with controllable side effects [34, 35]. Irinotecan-5-FU can, therefore, be considered a treatment alternative to platinum–fluoropyrimidine doublets according to scientific evidence; however, irinotecan has no formal approval in Europe for gastric cancer.

HER2-positive gastric cancer

HER2 positivity is defined in gastric cancer as the presence of protein expression with immunohistochemistry score [IHC] of 3 + or IHC 2 + and concomitant gene amplification on in situ hybridization [ISH], HER2/CEP17 ratio ≥ 2.0. HER2 diagnosis should be quality controlled [36, 37]. Trastuzumab should be added to chemotherapy in patients with HER2-positive advanced gastric cancer [21, 38]. The recommendation is based on data from the phase III ToGA trial, showing a higher response rate and prolonged survival for trastuzumab–cisplatin–fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy alone using the above selection criteria; the additional trastuzumab side effects are minor and controllable [38]. Combinations of trastuzumab and oxaliplatin plus fluoropyrimidine show comparable results to the historical cisplatin-containing ToGA regimen [39–41]. Based on data from the not yet fully reported results of the Keynote-811 study, the Commission for Human Medical Products (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) published a positive opinion for pembrolizumab plus trastuzumab and chemotherapy as first-line treatment for HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) adenocarcinoma expressing PD-L1 (CPS ≥ 1) on 20th of July 2023 (https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/summaries-opinion/keytruda-10). If available, this combination should be preferred over trastuzumab plus chemotherapy in the respective patient population (Fig. 2).

Immunotherapy

The phase III CheckMate 649 trial evaluated the addition of nivolumab to chemotherapy (capecitabine-oxaliplatin or 5-FU/folinic acid-oxaliplatin) in patients with previously untreated gastric, esophago-gastric junction, or esophageal adenocarcinoma [42]. The study included patients regardless of tumor PD-L1 status; the dual primary endpoints were overall survival and progression-free survival. Approximately 60% of the study population had tumors with a PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5. Nivolumab plus chemotherapy yielded a significant improvement over chemotherapy alone in overall survival (14.4 vs. 11.1 months, HR 0.71 [98.4% CI 0.59–0.86]; p < 0.0001) and progression-free survival (7.7 vs. 6.0 months, HR 0.68 [98% CI 0.56–0.81]; p < 0.0001) in patients with a PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5. Overall survival benefit was enriched in patients with MSI-H tumors with nivolumab plus chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy (unstratified hazard ratio 0.38; 95% confidence interval 0.17, 0.84).

The Asian phase II/III ATTRACTION-04 trial also showed a significant improvement in progression-free survival with nivolumab and first-line chemotherapy, but with no significant improvement in overall survival compared to first-line chemotherapy alone. The most likely reason for the lack of survival benefit (> 17 months in both arms) is that many patients received post-progression therapies including immunotherapy after first-line therapy [43].

The multinational randomized phase III Keynote-859 trial included 1589 patients with advanced incurable gastric cancer. Patients received either platinum–fluoropyrimidine plus pembrolizumab or the same chemotherapy plus placebo every 3 weeks. Overall survival was prolonged in the pembrolizumab group (HR 0.78 [95% CI 0.70–0.87], p < 0.0001). The effect was more pronounced in the subgroup with a PD-L1 CPS ≥ 10 (HR 0.64), whereas efficacy was lower for CPS < 10 (HR 0.86). Overall survival benefit was enriched in patients with MSI-H tumors with pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy (hazard ratio 0.34; 95% confidence interval 0.176, 0.663) [44]. The results, thus, complement the positive trial data from the phase III Keynote-590 study, which led to EU approval of pembrolizumab in combination with platinum–fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and esophago-gastric junction [45].

Positive phase III trial data were also presented on two immune checkpoint (PD-1) inhibitors not currently approved in Europe. Sintilimab in combination with oxaliplatin and capecitabine improved overall survival in the phase III ORIENT-16 trial [46]. In the phase III Rationale-305 study, tislelizumab prolonged overall survival in combination with platinum–fluoropyrimidine or platinum-investigator-choice chemotherapy in patients with a positive PD-L1 score. PD-L1 was evaluated according to a scoring system not yet established internationally (the so-called Tumor Area Proportion score, TAP) [47]. ORIENT-16 and Rationale-305 have not been fully published to date, but support the overall assessment that PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitors can improve the efficacy of chemotherapy (depending on PD-L1 expression).

Claudin 18.2

Data from the multinational phase III Spotlight trial were recently published. These show that in patients with advanced irresectable gastric cancer and tumor claudin 18.2 expression in ≥ 75% of tumor cells, zolbetuximab, a chimeric monoclonal IgG1 antibody directed against claudin 18.2, in combination with FOLFOX chemotherapy prolongs overall survival (median 18.23 vs. 15.54 months, HR 0.750, p = 0.0053). The main side effects of zolbetuximab are nausea and vomiting, especially during the first applications [48]. The results of the phase III Spotlight trial are largely confirmed by the multinational phase III GLOW trial, in which the chemotherapy doublet was used as a control therapy or combination partner for zolbetuximab [49]. It remains to be seen whether the European Medicines Agency will grant approval to zolbetuximab in patients with claudin 18.2-positive metastatic and previously untreated gastric cancer.

Second-line and third-line therapy chemotherapy and anti-angiogenic therapy

Figures 3 and 4 show the algorithm for second- and third-line therapy for patients with advanced gastric cancer. The evidence-based chemotherapy options in this setting are paclitaxel, docetaxel, and irinotecan, which have comparable efficacy with different specific toxicities [21, 50–52]. Irinotecan may be preferred in patients with preexisting neuropathy; however, there is no EU approval. 5-FU/folinic acid plus irinotecan (FOLFIRI) is also occasionally used, but the scientific evidence for its use in second- and third-line treatment is limited [53]. Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel is the recommended standard for second-line therapy and is approved in the EU. The addition of the anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) antibody ramucirumab to paclitaxel increases tumor response rates and prolongs progression-free and overall survival according to the results of the phase III RAINBOW trial [54]. Already in the phase III REGARD trial, ramucirumab monotherapy showed prolonged survival compared to placebo, albeit with a low radiological response rate [55].

Immunotherapy in second- and third-line therapy

In the phase III KEYNOTE-061 trial, pembrolizumab monotherapy did not show prolonged overall survival compared with chemotherapy [56]. However, an exploratory subgroup analysis recognized a clear benefit for anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in patients with MSI-H gastric cancer [57]. Therefore, PD-1 inhibition is recommended in advanced MSI-H carcinomas at the latest in second-line treatment. Pembrolizumab has European approval for this indication based on the Keynote-061 and Keynote-158 trials [58]. Of note, pembrolizumab in second line for MSI-High advanced gastric cancer is not recommended when immunotherapy was administered in first-line treatment. Other biomarkers, particularly EBV and tumor mutation burden, are also discussed as predictive factors for PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor efficacy [59–61]. However, the evidence to date is insufficient to support a positive recommendation for immunotherapy based upon the presence of these biomarkers.

HER2-targeted therapy

Studies evaluating trastuzumab, lapatinib, and trastuzumab emtansine for second-line treatment in patients with HER2-positive carcinomas were negative [62–65]. Therefore, these drugs should not be used in gastric cancer outside of clinical trials. A randomized phase II trial showed an improvement in tumor response rate and overall survival for the antibody–drug conjugate trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) compared with standard chemotherapy in patients with pretreated HER2-positive advanced gastric cancer [66]. Destiny-GC-04 is an ongoing study, assessing the efficacy and safety of T-DXd compared with ramucirumab and paclitaxel in participants with HER2-positive (defined as immunohistochemistry [IHC] 3 + or IHC 2 + /in situ hybridization [ISH] +) gastric or esophago-gastric junction adenocarcinoma who have progressed on or after a trastuzumab-containing regimen and have not received any additional systemic therapy (https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04704934).

Prerequisites for inclusion in the Destiny-GC-01 study were at least two prior lines of therapy, prior treatment with a platinum derivative, a fluoropyrimidine, and trastuzumab, and previously confirmed HER2 positivity. The study was recruited exclusively in East Asia. The results of Destiny-GC-01 were largely confirmed in the single-arm phase II Destiny-GC-02 trial, which included non-Asian patients in second-line therapy. Mandatory was platinum–fluoropyrimidine–trastuzumab pretreatment and confirmed HER2 positivity of the tumor in a recent re-biopsy before initiating T-DXd therapy [67].

The EU approval includes the following indication of T-DXd: monotherapy for the treatment of adult patients with advanced HER2-positive adenocarcinoma of the stomach or esophago-gastric junction who have received a prior trastuzumab-based regimen.

We recommend, according to the classically established HER2 diagnostic criteria, to check the HER2 status prior to therapy with T-DXd, especially if use in second-line therapy is planned, where a valid alternative with paclitaxel–ramucirumab is available. This recommendation is based on the inclusion criteria of the Destiny-GC-02 trial and the knowledge that loss of HER2 status occurs in approximately 30% of gastric cancers after first-line therapy with trastuzumab [62].

There is initial evidence of efficacy of T-DXd in low HER2 expression [68]. However, data are not yet sufficient to recommend its use.

Third-line therapy

For the treatment of patients with advanced gastric cancer in the third line and beyond, the best evidence is available for trifluridine–tipiracil (FTD/TPI) based on the phase III TAGS trial. Median overall survival with FTD/TPI vs. placebo was significantly improved in the overall patient cohort, in the third-line cohort, and in the fourth-line cohort [69–71]. Therefore, if oral therapy is feasible, trifluridine–tipiracil (FTD/TPI) should be used; alternatively, if intravenous therapy is preferred, irinotecan or a taxane can be given, if not already used in a previous line of therapy. As shown above, T-DXd is a very effective third-line therapy for HER2-positive carcinoma after trastuzumab pretreatment. Nivolumab also proved to be effective; however, the data from the ATTRACTION-02 trial were obtained exclusively in Asian patients [72], so that nivolumab in the third line of treatment in patients with advanced gastric cancer does not have EMA approval, and therefore cannot be recommended.

Following the recommendation of a molecular tumor board, an unapproved therapeutic option may also be preferred in justified cases, especially if the recommendation can be based on an ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of Molecular Targets (ESCAT) level I or II [73].

Surgery for metastatic gastric cancer

The randomized phase III REGATTA trial showed that gastrectomy in addition to chemotherapy for metastatic disease did not confer a survival benefit compared with chemotherapy alone [74]. International data analyses show that surgical therapy for oligometastasic disease is increasingly perceived as a treatment option [75–77]. The AIO-FLOT3 phase II trial reported results on the feasibility of resection for stage IV gastric cancer and survival in highly selected patients with oligometastatic disease that was without primary progression on FLOT chemotherapy [78]. The potential prognostic benefit of resections for oligometastatic gastric cancer is currently being evaluated in randomized phase III trials [RENAISSANCE (NCT0257836) and SURGIGAST (NCT03042169)].

In a Delphi procedure, a definition for oligometastasis was determined in a European expert group (OMEC). According to this definition, oligometastasis can be defined as the following phenotypes: 1–2 metastases in either liver, lung, retroperitoneal lymph nodes, adrenal glands, soft tissue or bone [77].

Supportive therapy and nutrition

It is recommended that nutritional and symptom screening with appropriate tools be performed regularly in all patients with advanced gastric cancer, and appropriate supportive therapies be derived. A study from China showed that early integration of supportive-palliative care is effective and suggests a survival benefit in patients with advanced gastric cancer [79].

Weight loss is a multifactorial phenomenon and may be due to digestive tract obstruction, malabsorption, or hypermetabolism. Clinical data sets show that weight loss of ≥ 10% before chemotherapy or ≥ 3% during the first cycle of chemotherapy is associated with poorer survival [80]. Also, a change in body composition with impaired muscular capacity was shown to be prognostically unfavorable in patients with advanced gastric cancer [81]. The modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (serum CRP and albumin) can be used to assess the extent of sarcopenia and the prognosis of patients with advanced gastric cancer [82].

From this, it can be concluded that screening for nutritional status should be performed in all patients with advanced gastric cancer (for example, using Nutritional Risk Screening, NRS) [83] and expert nutritional counseling and co-supervision should be offered, if nutritional deficiency is evident.

Dysphagia in proximal gastric cancer can be improved with radiotherapy or stent insertion [84]. Single-dose brachytherapy is the preferred option at some centers and results in longer-lasting symptom control and fewer complications than stent insertion. Stenting is needed for severe dysphagia and especially in patients with limited life expectancy, as the effects of the stent are immediate, whereas radiotherapy improves dysphagic symptoms only after approximately 4–6 weeks [85]. If radiotherapy or a stent are not an option, enteral nutrition via naso-gastric, naso-jejunal, or percutaneously placed feeding tubes may provide relief [86]. The indication for parenteral nutrition follows generally accepted guidelines.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.AWMF S3 guideline. Gastric carcinoma. Diagnosis and therapy of adenocarcinomas of the stomach and esophagogastric junction. 2019. http://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/032-009OL.html

- 2.Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma: an attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–34. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parsonnet J, Vandersteen D, Goates J, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in intestinal- and diffuse-type gastric adenocarcinomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:640–643. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.9.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors. In: Wittekind C, editor. Wiley-Blackwell. USA; 2016.

- 5.The Cancer Genome Atlas Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202–209. doi: 10.1038/nature13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Batran SE, Hartmann JT, Probst S, et al. Phase III trial in metastatic gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma with fluorouracil, leucovorin plus either oxaliplatin or cisplatin: a study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1435–1442. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen CY, Hsu JS, Wu DC, et al. Gastric cancer: preoperative local staging with 3D multi-detector row CT-correlation with surgical and histopathologic results. Radiology. 2007;242:472–482. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2422051557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwee R, Kwee T. Imaging in assessing lymph node status in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:6–22. doi: 10.1007/s10120-008-0492-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Catalano MF, Sivak MV, Jr, Rice T, et al. Endosonographic features predictive of lymph node metastasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:442–446. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(94)70206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett C, Wang Y, Pan T. Endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4:004276. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004276.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tada M, Tanaka Y, Matsuo N, et al. Mucosectomy for gastric cancer: current status in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15(Suppl):D98–102. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Cancer Institute: Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/stomach.html

- 13.Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ychou M, Boige V, Pignon JP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: an FNCLCC and FFCD multicenter phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1715–1721. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Batran SE, Homann N, Pauligk C, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or capecitabine plus cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced, resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): a randomised, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393:1948–1957. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32557-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofheinz RD, Merx K, Haag GM, et al. FLOT versus FLOT/trastuzumab/pertuzumab perioperative therapy of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive resectable esophagogastric adenocarcinoma: a randomized phase II trial of the AIO EGA study group. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:3750–3761. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.00380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pietrantonio F, Miceli R, Raimondi A, et al. Individual patient data meta-analysis of the value of microsatellite instability as a biomarker in gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:3392–3400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Batran SE, Lorenzen S, Homann N, et al. Pathological regression in patients with microsatellite instability (MSI) receiving perioperative atezolizumab in combination with FLOT vs. FLOT alone for resectable esophagogastric adenocarcinoma: Results from the DANTE trial of the German Gastric Group at the AIO and SAKK. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(5):1040–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.1538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.André T, Tougeron D, Piessen G, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus ipilimumab and adjuvant nivolumab in localized deficient mismatch repair/microsatellite instability-high gastric or esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma: the GERCOR NEONIPIGA phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:255–265. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.00686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van Grieken NC, Lordick F. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2020;396:635–648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagner AD, Syn NL, Moehler M, et al. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;8:004064. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004064.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cunningham D, Starling N, Rao S, et al. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced esophagogastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:36–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okines AFC, Norman AR, McCloud P, et al. Meta-analysis of the REAL-2 and ML17032 trials: evaluating capecitabine-based combination chemotherapy and infused 5-fluorouracil-based combination chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced esophago-gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1529–1534. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cassidy J, Saltz L, Twelves C, et al. Efficacy of capecitabine versus 5-fluorouracil in colorectal and gastric cancers: a meta-analysis of individual data from 6171 patients. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2604–2609. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ajani JA, Abramov M, Bondarenko I, et al. A phase III trial comparing oral S-1/cisplatin and intravenous 5-fluorouracil/cisplatin in patients with untreated diffuse gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:2142–2148. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koizumi W, Narahara H, Hara T, et al. S-1 plus cisplatin versus S-1 alone for first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:215–221. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall PS, Swinson D, Cairns DA, et al. Efficacy of reduced-intensity chemotherapy with oxaliplatin and capecitabine on quality of life and cancer control among older and frail patients with advanced gastroesophageal cancer: the GO2 phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:869–877. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, et al. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4991–4997. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lorenzen S, Hentrich M, Haberl C, et al. Split-dose docetaxel, cisplatin and leucovorin/fluorouracil as first-line therapy in advanced gastric cancer and adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction: results of a phase II trial. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1673–1679. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Batran SE, Hartmann JT, Hofheinz R, et al. Biweekly fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel (FLOT) for patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or esophagogastric junction: a phase II trial of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1882–1887. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shah MA, Janjigian YY, Stoller R, et al. Randomized multicenter phase II study of modified docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil (DCF) versus DCF plus growth factor support in patients with metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma: a study of the US Gastric Cancer Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3874–3879. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.7465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Cutsem E, Boni C, Tabernero J, et al. Docetaxel plus oxaliplatin with or without fluorouracil or capecitabine in metastatic or locally recurrent gastric cancer: a randomized phase II study. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:149–156. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamada Y, Boku N, Mizusawa J, et al. Docetaxel plus cisplatin and S-1 versus cisplatin and S-1 in patients with advanced gastric cancer (JCOG1013): an open-label, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:501–510. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dank M, Zaluski J, Barone C, et al. Randomized phase III study comparing irinotecan combined with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid to cisplatin combined with 5-fluorouracil in chemotherapy naive patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the stomach or esophagogastric junction. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1450–1457. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guimbaud R, Louvet C, Ries P, et al. Prospective, randomized, multicenter, phase III study of fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan versus epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine in advanced gastric adenocarcinoma: a French intergroup (Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie digestive, Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer, and Groupe Coopérateur Multidisciplinaire en Oncologie) study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3520–3526. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lordick F, Al-Batran SE, Dietel M, et al. HER2 testing in gastric cancer: results of a German expert meeting. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143:835–841. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2374-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haffner I, Schierle K, Raimúndez E, et al. HER2 expression, test deviations, and their impact on survival in metastatic gastric cancer: results from the prospective multicenter VARIANZ study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1468–1478. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:687–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61121-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryu MH, Yoo C, Kim JG, et al. Multicenter phase II study of trastuzumab in combination with capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rivera F, Romero C, Jimenez-Fonseca P, et al. Phase II study to evaluate the efficacy of trastuzumab in combination with capecitabine and oxaliplatin in first-line treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric cancer: HERXO trial. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2019;83:1175–1181. doi: 10.1007/s00280-019-03820-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahari D, Chin K, Ishizuka N, et al. Multicenter phase II study of trastuzumab with S-1 plus oxaliplatin for chemotherapy-naïve, HER2-positive advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2019;22:1238–1246. doi: 10.1007/s10120-019-00973-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Janjigian YY, Shitara K, Moehler M, et al. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric, gastro-oesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 649): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398:27–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00797-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kang YK, Chen LT, Ryu MH, et al. Nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy in patients with HER2-negative, untreated, unresectable advanced or recurrent gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ATTRACTION-4): a randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:234–247. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00692-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rha SY, Wyrwicz LS, Weber PEY, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy as first-line therapy for advanced HER2-negative gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer: phase III KEYNOTE-859 study. Ann Oncol. 2023;34:P319–320. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun JM, Shen L, Shah MA, et al. Keynote-590 Investigators. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for first-line treatment of advanced oesophageal cancer (KEYNOTE-590): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase study. Lancet. 2021;398:759–771. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu J, Jiang H, Pan Y, et al. Sintilimab plus chemotherapy (chemo) versus chemo as first-line treatment for advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction (G/GEJ) adenocarcinoma (ORIENT-16): First results of a randomized, double-blind, phase III study. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:1331. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.2133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Möhler MH, Kato K, Arkenau HT, et al. Rationale 305: phase 3 study of tislelizumab plus chemotherapy vs placebo plus chemotherapy as first-line treatment (1L) of advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (GC/GEJC) J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:286. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2023.41.4_suppl.286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shitara K, Lordick F, Bang YJ, et al. Zolbetuximab plus mFOLFOX6 in patients with CLDN182-positive, HER2-negative, untreated, locally advanced unresectable or metastatic gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (SPOTLIGHT): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase trial. Lancet. 2023;401:1655–1668. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00620-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu RH, Shitara K, Ajani JA, et al. Zolbetuximab + CAPOX in 1L claudin-182+/HER2- locally advanced or metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: Primary phase 3 results from GLOW. J Clin Oncolo. 2023 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2023.41.36_suppl.405736. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thuss-Patience PC, Kretzschmar A, Bichev D, et al. Survival advantage for irinotecan versus best supportive care as second-line chemotherapy in gastric cancer–a randomised phase III study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO) Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2306–2314. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hironaka S, Ueda S, Yasui H, et al. Randomized, open-label, phase III study comparing irinotecan with paclitaxel in patients with advanced gastric cancer without severe peritoneal metastasis after failure of prior combination chemotherapy using fluoropyrimidine plus platinum: WJOG 4007 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4438–4444. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.5805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ford HE, Marshall A, Bridgewater JA, et al. Docetaxel versus active symptom control for refractory oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma (COUGAR-02): an open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:78–86. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70549-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brown J, Liepa AM, Bapat B, et al. Clinical management patterns of advanced and metastatic gastro-oesophageal carcinoma after fluoropyrimidine/platinum treatment in France, Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom. Eur J Cancer Care. 2020;29:e13213. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilke H, Muro K, Van Cutsem E, et al. Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): a double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1224–1235. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70420-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fuchs CS, Tomasek J, Yong CJ, et al. Ramucirumab monotherapy for previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (REGARD): an international, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:31–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61719-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shitara K, Özgüroğlu M, Bang YJ, et al. Pembrolizumab versus paclitaxel for previously treated, advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (KEYNOTE-061): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;392:123–133. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31257-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chao J, Fuchs CS, Shitara K, et al. Assessment of pembrolizumab therapy for the treatment of microsatellite instability-high gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer among patients in the KEYNOTE-059, KEYNOTE-061, and KEYNOTE-062 clinical trials. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:895–902. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marabelle A, Fakih M, Lopez J, et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1353–1365. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.St K, Cristescu R, Bass AJ, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clinical responses to PD-1 inhibition in metastatic gastric cancer. Nat Med. 2018;9:1449–1458. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0101-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gu L, Chen M, Guo D, et al. PD-L1 and gastric cancer prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0182692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Massetti M, Lindinger M, Lorenzen S. PD-1 blockade elicits ongoing remission in two cases of refractory Epstein-Barr virus associated metastatic gastric carcinoma. Oncol Res Treat. 2022;45:375–379. doi: 10.1159/000523754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Makiyama A, Sukawa Y, Kashiwada T, et al. Randomized, phase II study of trastuzumab beyond progression in patients with HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer: WJOG7112G (T-ACT study) J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1919–1927. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Satoh T, Xu RH, Chung HC, et al. Lapatinib plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel alone in the second-line treatment of HER2-amplified advanced gastric cancer in Asian populations: TyTAN-a randomized, phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2039–2049. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lorenzen S, Riera Knorrenschild J, Haag GM, et al. Lapatinib versus lapatinib plus capecitabine as second-line treatment in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-amplified metastatic gastroesophageal cancer: a randomised phase II trial of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thuss-Patience PC, Shah MA, Ohtsu A, et al. Trastuzumab emtansine versus taxane use for previously treated HER2-positive locally advanced or metastatic gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (GATSBY): an international randomised, open-label, adaptive, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:640–653. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shitara K, Bang YJ, Iwasa S, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-positive gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2419–2430. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ku GY, Di Bartolomeo M, Smyth E, et al. Updated analysis of DESTINY-Gastric02: A phase II single-arm trial of trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) in Western patients (Pts) with HER2-positive (HER2+) unresectable/metastatic gastric/gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) cancer who progressed on or after trastuzumab-containing regimens. Ann Oncol. 2022;33:S555–S580. doi: 10.1016/annonc/annonc1065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamaguchi K, Bang YJ, Iwasa S, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 treatment-naive patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-low gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: exploratory cohort results in a phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:816–825. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.00575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shitara K, Do T, Dvorkin M, et al. Trifluridine/tipiracil versus placebo in patients with heavily pretreated metastatic gastric cancer (TAGS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1437–1448. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30739-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ilson DH, Tabernero J, Prokharau A, et al. Efficacy and safety of trifluridine/tipiracil treatment in patients with metastatic gastric cancer who had undergone gastrectomy: subgroup analyses of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:e193531. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tabernero J, Shitara K, Zaanan A, et al. Trifluridine/tipiracil versus placebo for third or later lines of treatment in metastatic gastric cancer: an exploratory subgroup analysis from the TAGS study. ESMO Open. 2021;6:100200. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kang YK, Boku N, Satoh T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer refractory to, or intolerant of, at least two previous chemotherapy regimens (ONO-4538-12, ATTRACTION-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390:2461–2471. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31827-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mateo J, Chakravarty D, Dienstmann R, et al. A framework to rank genomic alterations as targets for cancer precision medicine: the ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of molecular Targets (ESCAT) Ann Oncol. 2018;29:1895–1902. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fujitani K, Yang HK, Mizusawa J, et al. Gastrectomy plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric cancer with a single non-curable factor (REGATTA): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:309–318. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00553-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Markar SR, Mikhail S, Malietzis G, et al. Influence of surgical resection of hepatic metastases from gastric adenocarcinoma on long-term survival: systematic review and pooled analysis. Ann Surg. 2016;263:1092–1101. doi: 10.1097/SLA.00000000001542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kataoka K, Kinoshita T, Moehler M, et al. Current management of liver metastases from gastric cancer: what is common practice? New challenge of EORTC and JCOG. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:904–912. doi: 10.1007/s10120-017-0696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kroese TE, van Hillegersberg R, Schoppmann S, et al. OMEC working group. Definitions and treatment of oligometastatic esophagogastric cancer according to multidisciplinary tumor boards in Europe. Eur J Cancer. 2022;164:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Al-Batran SE, Homann N, Pauligk C, et al. Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection on survival in patients with limited metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer: The AIO-FLOT3 Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1237–1244. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lu Z, Fang Y, Liu C, et al. Early interdisciplinary supportive care in patients with previously untreated metastatic esophagogastric cancer: a phase III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:748–756. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mansoor W, Roeland EJ, Chaudhry A, et al. Early weight loss as a prognostic factor in patients with advanced gastric cancer: analyses from REGARD, RAINBOW, and RAINFALL phase III studies. Oncologist. 2021;26:e1538–e1547. doi: 10.1002/onco.13836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hacker UT, Hasenclever D, Linder N, et al. Prognostic role of body composition parameters in gastric/gastroesophageal junction cancer patients from the EXPAND trial. J Cachexia Sarcop Muscle. 2020;11:135–144. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hacker UT, Hasenclever D, Baber R, et al. Modified Glasgow prognostic score (mGPS) is correlated with sarcopenia and dominates the prognostic role of baseline body composition parameters in advanced gastric and esophagogastric junction cancer patients undergoing first-line treatment from the phase III EXPAND trial. Ann Oncol. 2022;33:685–692. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.03.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kondrup J, Allison SP, Elia M, Vellas B, Plauth M. Educational and clinical practice committee, European society of parenteral and enteral nutrition (ESPEN). ESPEN guidelines for nutrition screening 2002. Clin Nutr. 2003;22:415–421. doi: 10.1016/s0261-5614(03)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dai Y, Li C, Xie Y, et al. Interventions for dysphagia in esophageal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;10:005048. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005048.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bergquist H, Wenger U, Johnsson E, et al. Stent insertion or endoluminal brachytherapy as palliation of patients with advanced cancer of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction Results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Dis Esophagus. 2005;18:131–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2005.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mulazzani GEG, Corti F, Della Valle S, Di Bartolomeo M. Nutritional support indications in gastroesophageal cancer patients: from perioperative to palliative systemic therapy A comprehensive review of the last decade. Nutrients. 2021;13:2766. doi: 10.3390/nu13082766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jamel S, Markar SR, Malietzis G, et al. Prognostic significance of peritoneal lavage cytology in staging gastric cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21:10–18. doi: 10.1007/s10120-017-0749-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lauwers GY, Carneiro F, Graham DY. Gastric carcinoma. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, editors. WHO Classification of tumours of the digestive system. Lyon: IARC; 2010. [Google Scholar]