Abstract

Epulopiscium fishelsoni, gut symbiont of the brown surgeonfish (Acanthurus nigrofuscus) in the Red Sea, attains a larger size than any other eubacterium, varies 10- to 20-fold in length (and >2,000-fold in volume), and undergoes a complex daily life cycle. In early morning, nucleoids contain highly condensed DNA in elongate, chromosome-like structures which are physically separated from the general cytoplasm. Cell division involves production of two (rarely three) nucleoids within a cell, deposition of cell walls around expanded nucleoids, and emergence of daughter cells from the parent cell. Fluorescence measurements of DNA, RNA, and other cell components indicate the following. DNA quantity is proportional to cell volume over cell lengths of ∼30 μm to >500 μm. For cells of a given size, nucleoids of cells with two nucleoids (binucleoid) contain approximately equal amounts of DNA. And each nucleoid of a binucleoid cell contains one-half the DNA of the single nucleoid in a uninucleoid cell of the same size. The life cycle involves approximately equal subdivision of DNA among daughter cells, formation of apical caps of condensed DNA from previously decondensed and diffusely distributed DNA, and “pinching” of DNA near the middle of the cell in the absence of new wall formation. Mechanisms underlying these patterns remain unclear, but formation of daughter nucleoids and cells occurs both during diurnal periods of host feeding and bacterial cell growth and during nocturnal periods of host inactivity when mean bacterial cell size declines.

In 1985, an unusual unicellular organism was reported from the gut of brown surgeonfish, Acanthurus nigrofuscus (Acanthuridae: Teleostei), in the Red Sea (14). These organisms were named Epulopiscium fishelsoni and tentatively placed in the kingdom Protoctista by Montgomery and Pollak (23) on the basis of their maximum size (>600 μm), great variation in length (∼30 to >600 μm) and volume (>2,000-fold) both within single hosts and during a daily cycle, daily variability in nucleoid and cytoplasm structure, and a peculiar mode of reproduction (daughter cells form within parental organisms and eventually emerge as mobile cells from the maternal envelope). Similar and apparently related organisms representing at least 10 different morphotypes were later collected from surgeonfishes from the Hawaiian Islands, French Polynesia, Tuvalu, Guam, southern Japan, Papua New Guinea, the Great Barrier Reef, and South Africa (8, 13a, 15a, 22, 24a). None of these organisms (here termed “epulos” to distinguish them from other groups of bacteria) has been cultured, so all descriptions of distribution or functions within hosts and descriptions of diel changes in size or stages in the life cycle are based on samples from populations of epulos collected from hosts sacrificed at different times of day and night.

Initial electron microscopy of epulos revealed a complex ultrastructure lacking standard eukaryotic organelles (8, 14, 23). Following suggestions by Clements and Bullivant (9) that the fine structure of cytoplasm, cell wall, and flagella indicated that epulos were in fact prokaryotic, Angert et al. (2) isolated and sequenced the gene encoding the 16S rRNA subunit, placing these giant microorganisms in a group of low-G+C gram-positive bacteria related to Clostridium. In situ hybridization with fluorescein-labelled oligonucleotide probes based on cloned rRNA sequences confirmed the source of the rRNA gene. E. fishelsoni represents, therefore, the largest bacterium so far described (2, 9).

Cell size also varies more than in other bacteria. If one estimates the volume of a cigar-shaped E. fishelsoni cell as roughly the volume of two cones, each with height and radius of the base equal to half of cell length and half of its maximal diameter, respectively (V = 2/3πr2h), the volume of a very large E. fishelsoni (∼354,000 μm3 [500 by 52 μm]) is approximately 3,000-fold greater than that of a very small E. fishelsoni (∼125.6 μm3 [30 by 4 μm]). The volume of a large epulo can, therefore, exceed the volume of a bacterium such as Escherichia coli (∼2 μm3 [1 by 2 μm]) (25) by at least 5 orders of magnitude.

Cellular or molecular mechanisms that may support and control such exceptional variability in dimension, volume and surface/volume ratios of E. fishelsoni are unclear. However, cells are highly mobile, vary in mean size and structure during a 24-h period, affect the pH of the host’s gut fluids differentially during day and night (suggesting metabolic changes on a diel cycle), and construct mobile daughter cells within the parental cell (9, 14, 23, 24). The active metabolism and corresponding expectation of genomic activity supporting synthesis of macromolecules led us to predict correlations between DNA quantity or condensation state and cell size or stage in the daily life cycle.

Because E. fishelsoni and related organisms have not been cultured, we relied on collections of cells from host fishes sacrificed at different times of day and night, fluorescence cytochemistry, microfluorometry, and transmission electron microscopy to describe changes in the functional state and distribution of DNA and other cell constituents during the microbe’s life cycle. Our primary objective was to study relationships between DNA quantity and cell volume, as well as possible changes in DNA distribution and functional activity of the nucleoid during the life cycle of E. fishelsoni. In this paper, we initially demonstrate that DNA quantity is directly proportional to cell volume rather than to length or surface area, and that large quantities of DNA are almost equally divided and distributed to developing daughter cells. We then describe how coordinated changes in DNA condensation state and distribution, nucleoid expansion, and cell wall deposition lead to the formation of daughter cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens of the host surgeonfish, A. nigrofuscus, were collected by net or hand spear near the Interuniversity Institute, Steinitz Marine Biological Laboratory, Eilat, Red Sea, Israel (see reference 21 for details of the site and the collection techniques). Because surgeonfish are active only during the day, host fish intended for sampling at night were held in flowing seawater prior to sacrifice; samples obtained during the day were taken shortly after fish were collected. Epulos have not been cultured, so each fish provided a single sample of an epulo population at the time of sacrifice.

Specimens were sacrificed by a blow to the head and immediately dissected. E. fishelsoni cells were collected from the central intestine of the fish within ∼15 min of host sacrifice. Cells were either examined live at the marine laboratory or were fixed (in absolute methanol for fluorometry and in other fixatives, described below, for light and electron microscopy) at various times of day and night for subsequent analysis at our home institutions.

Lengths of epulos varied within a single host fish, and epulo size distribution changed with time of day or night. In the field, we used an ocular grid in a Zeiss binocular microscope at ×100 to assign live cells collected at different times to ∼50-μm-interval length categories (<50 μm, 50 to 101 μm, and so on [see Table 1]). Sixty haphazardly chosen cells from each of two fish were measured per time period (total n = 120 per period). Because we were unable to measure rapidly moving cells precisely with the grid available to us at our field laboratory, we created a frequency distribution among categories and calculated an approximate mean length for each time period, assuming that all cells in a particular category were the median length for that category (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Lengths of epulos collected from brown surgeonfish, Eilat, Israel (Red Sea), June 1988a

| Cell length (μm) | No. of cells at time of collection (h)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0700– 0800 | 1100– 1200 | 1400– 1500 | 2100– 2200 | 2400– 0100 | 0300– 0400 | |

| <50 | 23 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 18 | 30 |

| 50–101 | 56 | 34 | 11 | 42 | 80 | 78 |

| 102–154 | 31 | 44 | 35 | 28 | 19 | 10 |

| 155–207 | 8 | 31 | 35 | 26 | 2 | 2 |

| 208–261 | 1 | 10 | 33 | 6 | 1 | 0 |

| 262–314 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 315–367 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Estimated mean | 89 | 133 | 175 | 139 | 79 | 70 |

a Data are from 60 haphazardly chosen cells from each of two fish per time period (n = 120 cells per time period). Modes for each time period are in bold print. Estimated mean lengths per time period were calculated by assuming that all cells in a category were the median length for that category (rounded to the nearest 5 μm).

Preserved cells intended for fluorometry (see below) were returned to Tel Aviv University. There, cells falling into several narrow size ranges (5 to 10 μm for cells <250 μm long, 20 to 30 μm for cells >300 μm long [see Table 2]) were selected from samples. Samples representing different collection times were treated independently. Initially, six size categories (groups I through VI of Table 2) were established, such that cells in each of groups II through VI had volumes approximately twice those of cells in the preceding smaller group (see Table 2). A seventh group (group 0) was later added to expand the size of range of surveyed cells and included specimens of the smallest easily assayed E. fishelsoni (∼30 μm long). Cells with lengths between ∼30 and ∼150 μm were excluded due to limitations in equipment available to make precise measurements.

TABLE 2.

DNA content per cell for seven size categories of E. fishelsoni cells determined by two methodsa

| Group | Cell length (μm) | Volume (μm3, 103) | Relative volume | DNA content per cell (arbitrary units ± 95% confidence interval)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNase + berberine sulfate staining

|

Fluorescent Fuelgen reaction

|

||||||

| Measured | Relative | Measured | Relative | ||||

| 0 | 30–35 | 0.169 | 1.0 | 0.263 ± 0.007 | 1.0 | ||

| I | 150–160 | 10.72 | 63.2 (1.0) | 17.2 ± 0.9 | 65.4 (1.0) | 22.1 ± 1.0 | 1.00 |

| II | 190–200 | 20.93 | 123.4 (1.9) | 34.3 ± 1.4 | 130.4 (2.0) | 44.8 ± 1.6 | 2.03 |

| III | 240–250 | 40.88 | 241.0 (3.9) | 68.2 ± 3.0 | 259.3 (4.0) | 90.75 ± 2.1 | 4.10 |

| IV | 300–320 | 85.74 | 505.5 (8.0) | 137.7 ± 4.7 | 523.6 (8.0) | 177.5 ± 3.8 | 8.03 |

| V | 390–420 | 167.47 | 987.4 (15.6) | 274.3 ± 3.6 | 1,043.0 (15.9) | 353.1 ± 3.6 | 15.97 |

| VI | 490–520 | 340.42 | 2,007.2 (31.7) | 544.2 ± 13.4 | 2,069.2 (31.6) | 703.7 ± 5.6 | 31.8 |

a Group 0, which includes the smallest specimens examined, has not been studied in detail (see subsequent tables) but is consistent with other size groups in terms of DNA quantity-volume relationships. Relative volumes and relative measures of DNA quantity per cell for the RNase plus berberine sulfate technique (see text) are calculated, therefore, using both group 0 and group I values (parentheses) as denominators. n = 60 cells for each group.

Because epulos collected at different times of day and night show marked variability in the distribution and condensation state of DNA and in the size and location of nucleoids, initial measurements of total DNA in nucleoids were made on cells from a sample taken at approximately 0800 h. Nucleoids in this material were compact, round in shape, and located at the poles of the cell. We studied 60 cells from each group. Surveys of a variety of cells sampled at different times of day or night were then made in order to describe correlations in state or distribution of DNA and other cell components with time or stage in the epulo life cycle. We used fluorescence cytochemistry, microfluorometry, and digital analysis of fluorescently stained cells, the most sensitive methods to measure amount and state of DNA and RNA in single prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells (3, 4, 10–13, 32, 33).

Fluorescence cytochemistry had never been applied to E. fishelsoni, so we used two classical fluorescence methods to estimate relative amounts of DNA in cells: the Fuelgen reaction with acridine yellow-Schiff-type reagent (Sigma), and berberine sulfate (Sigma) staining after ribonuclease treatment (3, 4, 10). Schiff reagent reacts with aldehyde groups of free deoxyribose nucleotides liberated by acid hydrolysis. Because the intensity of the Fuelgen reaction depends on temperature and time of hydrolysis, we standardized our preparation by hydrolyzing with 6 N HCl for 10 min at room temperature before treating with Schiff reagent for 30 min. After washing (in 1 N HCl–10% NaHSO3–distilled water [1/1/18 by volume] followed by distilled water), stained bacteria were mounted in nonfluorescent glycerine for measurements. In the second technique, we stained with a 0.01% solution of berberine sulfate in ethanol for 20 min after pretreatment with ribonuclease; berberine sulfate is an intercalating agent used without the hydrolysis required by the Fuelgen technique. A conventional fluorescence objective (10 by 0.40) and measuring diaphragms corresponding to the structure being measured (whole cell or nucleoid only) were used for measuring relative amounts of DNA (Fuelgen and berberine procedures); units were arbitrary (microamperes of current). Results from these two techniques (see Table 2) validate their application in this system.

We used both morphological and cytochemical criteria following staining with acridine orange to map the locations of different cell components during different stages in the cell and life cycles. Acridine orange has been applied widely as a bacterial stain to detect and characterize soil or sediment bacteria (15, 16, 27, 31), and the metachromic red or green fluorescence of acridine orange has been used to assess viability and physiological activity of both bacteria and bacterial spores (7, 18–20, 28).

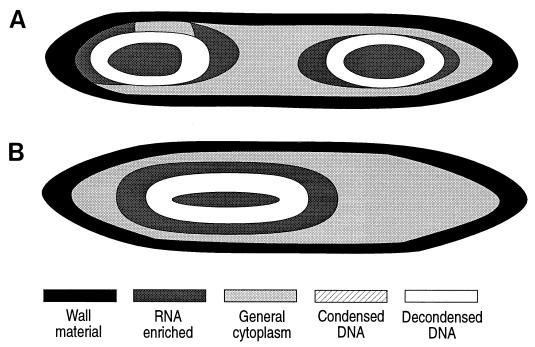

Cells stained with acridine orange were mapped according to the classes of molecules distinguished (those with condensed DNA or decondensed DNA, RNA enriched, general cytoplasm, cell wall [see Fig. 3 through 6]). The morphology of E. fishelsoni is well known from both light and electron microscope studies (9, 14, 23) (see Fig. 1 and 2), and we scanned cells stained with acridine orange under permanent visual control. We could, therefore, distinguish fluorescent signals from wall, cytoplasm, and nucleoid under the light microscope.

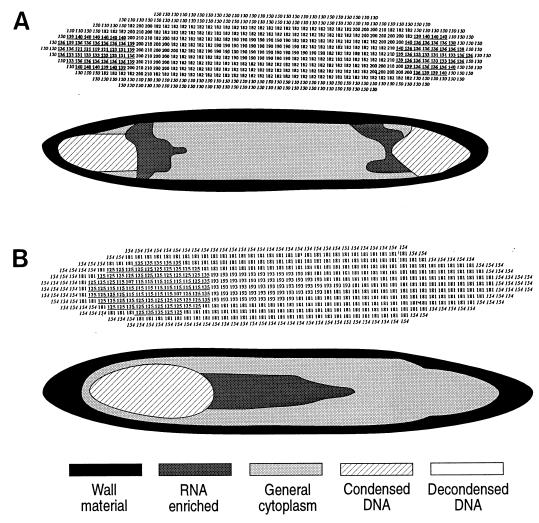

FIG. 3.

Digital images and graphical representation of the same images for binucleoid (A) and uninucleoid (B) E. fishelsoni cells collected at 0800 h and containing compact nucleoids similar to those shown in Fig. 1A and B. Both cells measured ∼520 by 65 μm. Cells were stained with acridine orange as described in the text. Values in digital images are R/G fluorescence ratios. Numbers in italics are values consistent with glycoprotein of cell walls; bold and underlined numbers are values consistent with condensed DNA or condensed DNA plus RNA; remaining values are consistent with RNA-enriched cytoplasm, with higher values reflecting higher concentrations of RNA. For visual clarity, ranges of values were identified for condensed DNA, decondensed DNA, general cytoplasm, RNA-enriched cytoplasm, and cell wall materials. Values were then replaced by distinctive shading or hatching patterns, and the edges were smoothed to more closely represent cell configuration. Subsequent figures present only the graphical images; copies of the original digital images are available from the authors and are posted on W. L. Montgomery’s web site (http://www2.nau.edu/∼wlm). In some figures generated from digital images, cell wall material appears unusually thick along sides and, particularly, apices of cells. This is due to readings of thick optical sections along strongly curved portions of whole cells. More accurate representations of walls occur in electron micrographs (Fig. 2) (14, 23).

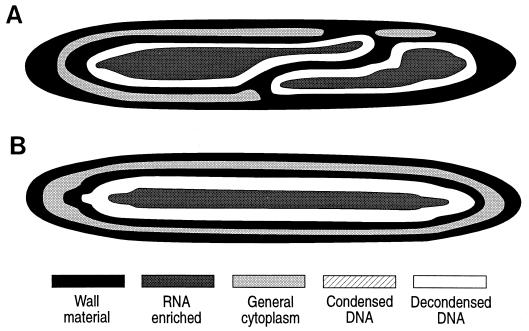

FIG. 6.

Maturing daughter cells of E. fishelsoni collected at 1640 h (A through C) and 0430 h (D through E). Other features are as described in the legend to Fig. 3. (A) Daughter cell (∼390 by 45 μm) lacking caps and with decondensed DNA evenly dispersed below the cell wall. (B) Daughter cell (∼350 by 45 μm) with two caps. (C) Daughter cell (∼350 by 45 μm) with single cap. (D) Daughter cell (∼360 by 45 μm) with two caps and DNA almost completely separated. (E) Daughter cell (∼360 by 45 μm) with two caps and DNA completely separated. Note mid-cell constriction of DNA in panels B and C that appears unrelated to additional wall formation (contrast with Fig. 4) and condensation of DNA in caps while that along periphery and in center of cell remains decondensed.

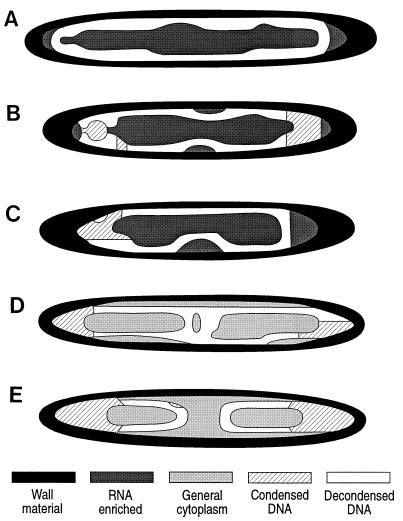

FIG. 1.

Light micrographs of stages in the life cycle of E. fishelsoni taken under differential interference contrast illumination. Bars = 50 μm. (A) A 237-μm-long cell with two compact, apical nucleoids (arrowheads). The cell was collected at 0640 h. (B) A 45-μm binucleoid (arrowheads) cell collected at 0640 h. (C) Uninucleoid and binucleoid cells with expanded nucleoids. The larger cell is 60 μm long. Unlike larger cells, small nucleoids (arrowheads) of small binucleoid cells do not overlap within the parent cell. Cells were collected at 2000 h. (D) Very small binucleoid cells with nonoverlapping nucleoids (arrowheads). The smallest cell (arrow) is 23 μm long with nucleoids that are <10 μm long. The cells were collected at 2000 h. (E) A 216-μm binucleoid cell with oval nucleoids (between arrowheads). Note the presumed spirillum (arrow) with a length of ∼18 μm. Cells were collected at 0915 h. (F) A 195-μm-long uninucleoid cell exhibiting presumed “caps” (see text) of condensed DNA (arrowhead) at apices of maximally enlarged nucleoid. Cell was collected at 1640 h. (G) A 225-μm-long uninucleoid cell with optically distinct daughter cell found only in night samples (compare with Fig. 1F). Cell was collected at 2200 h. (H) A 184-μm-long binucleoid cell with optically distinct daughter cells. Cells were collected at 0130 h.

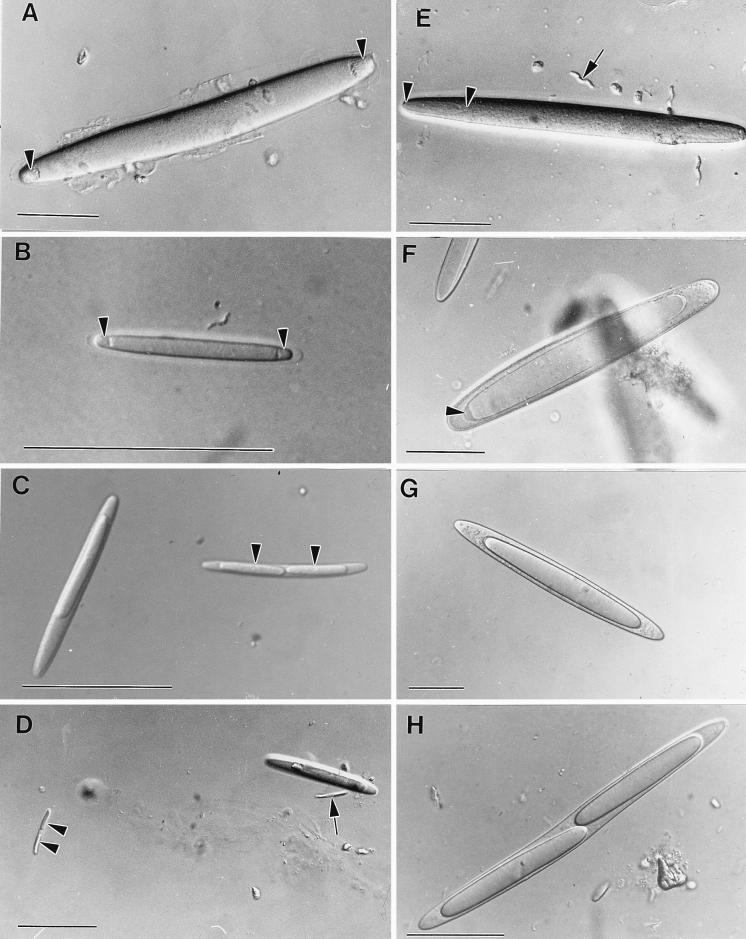

FIG. 2.

Transmission electron micrographs of compact nucleoids of E. fishelsoni collected at 0800 h. Note presumptive condensed DNA in chromosome-like bodies (arrowheads), delicate cross-striations on some of these bodies, and separation of nucleoidal material from remaining cytoplasm by structures (arrows) continuous with similar materials below the cell wall at the tip of the cell. Bars = 1 μm. (A) Cell fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde–0.05 M cacodylate in filtered seawater. (B) Cell fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde–0.25 M sucrose–0.05 M cacodylate in distilled water.

The fluorescent signals we used for this purpose are the ratios of red and green fluorescence (red fluorescence/green fluorescence × 1,000 [R/G ratio]) of acridine orange excited at 380 to 420 nm. In all treatments and stages in the life cycle (see Table 4), ratios for wall materials remained stable at 150 to 154 and thus served as a check on the comparability of the technique among treatments. Variation among samples in ratios measured for cytoplasm and nucleoids was due primarily to either RNA enrichment or the condensation state of DNA. Acridine orange fluoresces green (maximum at 530 nm with excitation at 380 to 420 nm) when intercalated near A-T (or A-U) base pairs of double-stranded nucleic acids (e.g., DNA and duplex sections of tRNAs) but fluoresces red (maximum at 620 nm) when associated with single-stranded nucleid acids. (Red and green autofluorescence of fixed, unstained cells was <5% of values for stained cells and is ignored here; red fluorescence of epulos [reported in reference 14] occurred when live cells were excited at 510 to 560 nm). Thus, nucleoids with highly condensed DNA will generate lower R/G ratios than nucleoids with decondensed DNA, those with relatively high frequency of single-stranded DNA segments, or those enriched with RNA; in fact, any sites enriched with RNA will exhibit high R/G ratios (11–13, 33).

TABLE 4.

Values of R/G fluorescence ratios in the nucleoids, cytoplasm, and peripheral areas of E. fishelsonia

| Nucleoid type | Mean R/G ratio | SD | SE | 95% confidence interval | Minimum R/G ratio | Maximum R/G ratio | DNA content (arbitrary units) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apical with condensed DNA | |||||||

| Nucleoid | 128.3 (124.8) | 7.8 (7.2) | 0.5 (0.5) | 1.0 (1.0) | 107 (115) | 210 (136) | 247 (197) |

| Cytoplasm | 184.4 (0) | 6.9 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 174 (0) | 210 (0) | 812 |

| Periphery | 151.8 (151.4) | 2.0 (1.9) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.3) | 150 (150) | 154 (154) | 460 (135) |

| Elongate with decondensed DNA | |||||||

| Nucleoid | 145.2 (136.7) | 3.4 (2.1) | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.3) | 140 (133) | 148 (139) | 232 (138) |

| Cytoplasm | 210.6 (0) | 32.4 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 182 (0) | 267 (0) | 732 |

| Periphery | 151.6 (150.9) | 2.0 (1.7) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.3) | 150 (150) | 154 (154) | 393 (131) |

| Capped with highly condensed DNA | |||||||

| Nucleoid | 111.4 (112.1) | 13.4 (3.9) | 1.0 (0.4) | 1.9 (0.8) | 92 (96) | 132 (115) | 187 (86) |

| Cytoplasm | 204.2 (0) | 24.1 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 182 (0) | 250 (0) | 547 |

| Periphery | 151.5 (151.1) | 2.6 (1.2) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.3) | 148 (150) | 154 (154) | 434 (135) |

a Values in parentheses are measurements on different cells taken from the same samples and treated with RNase before scanning with a microfluorometer. See Fig. 3 to 6 for distributions within cells at various stages in the life cycle of condensed and decondensed DNA, general and RNA-enriched cytoplasm, and peripheral materials. Note the stability of measurements for peripheral materials at all stages, in contrast to changes in degree of condensation of DNA (low ratios indicate high condensation) in the nucleoids and enrichment of cytoplasm by RNA (higher values result from enrichment).

In order to control for RNA content in nucleoids and cytoplasm of epulos, cells taken at the same life history stage and from the same samples as those scanned for Fig. 3 through 6 were treated with RNase (DNase-free RNase A; Sigma). Cells were incubated in RNase solution (100 U/ml) for 2 h at 37°C, washed in cold phosphate buffer, stained with acridine orange, and scanned as described above. This control demonstrates the impact of RNA enrichment on ratios from various samples and explains why ratios may appear to overlap for different regions of the cells. For example, R/G ratios for cytoplasm prior to RNase treatment ranged from 174 to 210 but dropped to 0 after RNase treatment as red fluorescence was eliminated. For nucleoids, ranges of ratios pre- and post-RNase treatment were 92 to 210 and 96 to 139, respectively, demonstrating that ratios for DNA did not overlap with those of cytoplasm and cell wall.

We used a special microfluorometer equipped with both conventional and contact fluorescence objectives for this work (5, 6). This included an epifluorescence illuminator (OI-30; Leningrad Optical and Mechanical Corporation) designed for work with both contact objectives (tube length, 190 mm) and conventional objectives (tube length, 160 mm), a focusing system for contact objectives, changeable filters, rectangular changeable measuring diaphragms, and a Nikon photomultiplier. To create digital images which show distribution and state of cellular components at various stages of the cell cycle, we scanned longitudinal optical sections through the central plane of cells. A fluorescence contact objective (60 by 1.15), a rectangular measuring diaphragm (5 by 10 μm), and dual-wavelength microfluorometry at 530 and 620 nm allowed us to calculate the R/G ratio and plot values for each 5-by-10-μm frame. Digital images were thus produced for uninucleoid (those with a single nucleoid) and binucleoid (those with two nucleoids) cells of approximately equal size from each separate time sample. These were then scanned into a computer, ranges of ratios representative of different compounds were replaced by distinctive shadings, and edges were smoothed to present a more realistic image (see Fig. 3 and legend for details).

Microbes intended for light and electron microscopy were fixed (2% glutaraldehyde–0.25 M sucrose–0.05 M cacodylate in distilled water or 2% glutaraldehyde–0.05 M cacodylate in filtered seawater). Light micrographs were taken on Kodak Technical Pan film on a Leitz Orthomat E microscope with differential interference contrast (Nomarsky) optics. Specimens for transmission electron microscopy were postfixed in 1% OsO4, embedded in EMBED 812 resin, thin sectioned, and viewed on a JEOL 1200exII electron microscope.

Descriptive statistics were calculated, and statistical tests were performed with Systat (version 5.03) and Sigma Plot.

RESULTS

Life cycle of E. fishelsoni.

Key events in the E. fishelsoni life cycle include changes in mean cell size as well as changes in number, size, shape and location of nucleoids and incipient daughter cells (Table 1; Fig. 1) (23). Because cell replication events occur against a backdrop of consistent, daily changes in apparent cell function and size, we distinguish the cell cycle (restricted to cell division events) from the life cycle (which includes events throughout a 24-h period). We term cells with a single nucleoid uninucleoid and those with two nucleoids binucleoid. We have encountered E. fishelsoni cells with three nucleoids, but their extreme rarity (e.g., a single trinucleoid cell was seen among 480 cells surveyed in 1988) leads us to ignore them here.

In early morning, cells contain compact, round nucleoids located near the apices of the cells (Fig. 1A and B, 2, and 3). Nucleoids elongate during the day until, in late afternoon and evening, they attain a maximum of ∼75% of the parent cell length in both uni- and binucleoid cells with lengths of >∼100 μm (23); nucleoids of smaller parent cells are usually <50% of parent cell length and, unlike nucleoids of larger cells, do not overlap within the parent (Fig. 1C and D; similar to morphotypes E, G, or J described in reference 8). Also during the day, average cell length increases (Table 1), and nucleoids of intermediate lengths are encountered (Fig. 1E), eventually growing to afternoon and evening sizes, at which they make up large fractions of parent cell volume (Fig. 1F). Occasional nucleoids in cells encountered at night (Fig. 1G and H) appeared more optically dense than usual (Fig. 1F). In any event, daughter cells are then released from the parent cell, which is destroyed in the process.

During the night, when the host fishes are inactive, binucleoid cells are common (accounting for over 70% of all cells in some samples [reference 23 and this study]), as are cells that appear to be recently released daughter cells based on their lack of incipient daughter cells, and average cell length declines (Table 1). Data are presented below for DNA content of relatively small epulos (category 0; length, ∼30 μm), but apparent epulos encountered late at night and in early morning may be much smaller (Fig. 1C and D), approaching the lengths of more commonly studied rod-shaped bacteria. These cells have not been studied, but four observations indicate that they are small forms of E. fishelsoni. They are absent from daytime samples, are largely restricted to early morning samples, consistently produce two daughter cells, and link through recognizable intermediate stages to larger epulos.

General aspects of the epulo life cycle coincide with host activities (21). Increase in modal size of cells and nucleoids occurs during the day, when hosts are actively feeding and the gut is completely filled with algal food materials; during this time, pH of gut fluids is suppressed in areas where epulos occur in profusion (23, 24). Nocturnal declines in modal cell size occur when hosts are inactive in reef shelters; no suppression of pH in gut fluids is evident at night.

Structure and DNA content of compact nucleoids.

E. fishelsoni cells collected at 0800 h included both binucleoid cells, with two compact, round nucleoids located near the poles of the cell (Fig. 2 and 3A), and uninucleoid cells, with a single compact nucleoid located at one pole (Fig. 3B). To avoid variation in dispersion and state of DNA that might be caused by comparing different stages in the cell cycle, we initially measured total DNA on cells from this morning collection (Table 2). As noted above, cells in size categories II through VI were approximately twice the volume of cells within the previous, smaller category.

Treatment of cells with fluorescent Fuelgen or RNase-berberine sulfate showed that nucleoids consisted of a dense matrix of DNA. Digital images based on acridine orange staining yielded R/G ratios characteristic of condensed, double-stranded nucleic acid (mean = 128.3; standard deviation = 7.8). Individual nucleoids differed somewhat in the range of measured ratios (e.g., 119 to 140 and 131 to 140 for Fig. 3A; 107 to 135 for Fig. 3B) and in the specific location of particular ratios within a nucleoid, although values from the periphery of nucleoids were generally higher than values from centrally located regions.

Electron micrographs of cells from the same collections (Fig. 2) support this interpretation, clearly showing condensed materials at the apices of cells. The two micrographs in Fig. 2 represent two different fixations yet have important similarities. The most electron-dense materials are arrayed in elongate strands ∼200 nm in diameter, generally appear composed of a core of darkly staining material surrounded by a halo of slightly less dense material, and exhibit striations with a periodicity of ∼40 nm. The position of the strands (dispersed in one section, clustered in the other) may be a function of the plane of the section. Also, in each case the nucleoids are surrounded and separated from the remaining cytoplasm by a line of unidentified material which appears continuous with a similar material at the perimeter of the cell.

Microfluorometric measurements of total DNA in nucleoids of either Fuelgen- or berberine sulfate-treated cells from the 0800-h sample demonstrated three patterns. First, DNA content per cell is proportional to cell volume over a considerable range of size (∼30 to 520 μm [Table 2]), and variation in total DNA content for cells of a given size, whether they were uninucleoid or binucleoid, was relatively low; coefficients of variation ranged from 3.1% (group VI) to 17.6% (group I).

Second, uninucleoid and binucleoid cells of the same size contain the same amount of DNA (Table 3). For example, the ratio of total DNA in binucleoid cells (Table 3) to DNA in the nucleoid of a uninucleoid cell of the same size group ranged from 0.96 to 1.19 in the four groups measured; the individual ratios did not differ significantly from 1.0 by the chi-square test (n = 4; ratios calculated from means of uninucleoid and binucleoid total DNA).

TABLE 3.

DNA content per nucleoid of uninucleoid and binucleoid cells as determined by RNase plus berberine treatment for four of six size groups of E. fishelsonia

| Group | DNA content per nucleoid of uninucleoid cells | Size of nucleoid measuredb | DNA content per nucleoid of binucleoid cells | Binucleoid total DNA | L/S ratioc | Bi.total/uni. ratioc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 20.3 (0.8) | Large | 10.4 (0.3) | 18.4 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.05) | 0.96 |

| Small | 8.0 (0.2) | |||||

| III | 70.4 (2.1) | Large | 43.8 (0.7) | 81.6 (1.4) | 1.2 (0.02) | 1.19 |

| Small | 37.9 (0.7) | |||||

| V | 272.6 (3.9) | Large | 145.6 (1.0) | 282.4 (1.3) | 1.1 (0.01) | 1.04 |

| Small | 136.8 (0.8) | |||||

| VI | 551.8 (11.0) | Large | 298.2 (2.5) | 564.3 (4.2) | 1.1 (0.01) | 1.04 |

| Small | 266.2 (2.8) |

a Forty uninucleoid and 40 binucleoid cells of each size group were examined. Binucleoid total DNA is the mean sum of DNA content of large and small binucleoid cells. The L/S ratio is the ratio of DNA content of large binucleoid cells/DNA content of small binucleoid cells. The Bi.total/uni. ratio is the ratio of binucleoid total DNA/uninucleoid cell DNA content. Values are means (standard errors). DNA content is given in arbitrary units.

b Differences between means of small and large nucleoids were significant at <0.001 level for all size groups (paired-sample t test).

c Ratios were not significantly different from 1.0; chi-square test, χ20.05[39] = 54.6 (for L/S ratios) or χ20.05[3] = 7.8 (for Bi.total/uni.ratios).

Third, for binucleoid cells of a particular size, the amount of DNA per nucleoid is approximately identical for the two nucleoids (Table 3). DNA content generally differs little between daughter nucleoids of individual cells, with mean ratios of DNA content in the larger of the two nucleoids relative to the smaller nucleoid ranging from 1.1 to 1.3. However, chi-square tests using individual ratios for each of the 40 cells examined per size group found no significant deviations from 1.0 in any group.

Changes in state and distribution of DNA with stages of the cell cycle.

The following sections are best interpreted in light of the general effects of RNase treatment on samples (Table 4). R/G ratios of the periphery of cells, interpreted as cell wall materials, remained unchanged at 150 to 154. Ratios for cytoplasm dropped from high values to zero due to the loss of red fluorescence from RNA. Ratios for compact, apical nucleoids declined slightly (128.3 to 124.8) and those for apical caps remained essentially unchanged (111.4 to 112.1), indicating little single-stranded nucleic acid. In contrast, the mean ratio for enlarged nucleoids declined from 145.2 to 136.7, indicating that single-stranded nucleic acid is common in such nucleoids.

(i) Morning.

As noted above, in early morning most cells contain compact, apical nucleoids (Fig. 1A and B). The DNA in these nucleoids exhibited R/G ratios characteristic of condensed DNA. Ratios for nucleoids in the samples collected at 0800 h averaged 128.3 (95% confidence interval, ±1.0 [Table 4]). Shortly before this, in samples collected at 0640 h, average R/G ratios were even lower (109.8 ± 2.5), suggesting that DNA in the 0800-h samples was partially decondensed.

R/G ratios for the general cytoplasm and the extreme periphery of cells were similar for the 0640- and 0800-h samples. High ratios characteristic of single-stranded nucleic acids, primarily RNA, occurred in cytoplasm at 0640 and 0800 h (182.1 ± 0.2 and 184.4 ± 0.5, respectively). Lower ratios characteristic of proteins and glycoproteins occurred along the edge of the cells (150.7 ± 0.2 and 151.8 ± 0.2, for the same periods, respectively), consistent with deposition of cell walls and, perhaps, membrane-associated enzymes.

(ii) Late morning.

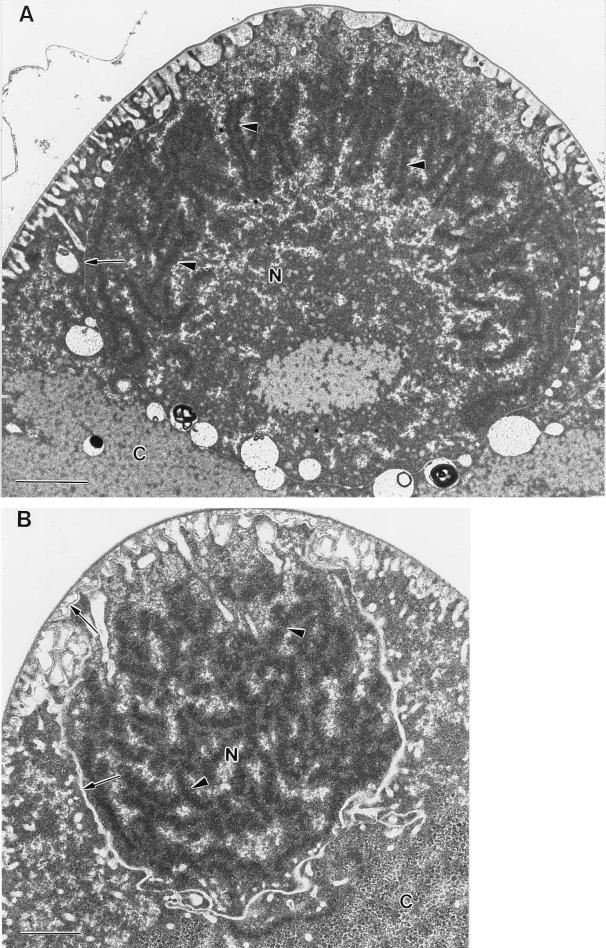

In most cells collected between 1000 and 1100 h, nucleoids in both uninucleoid and binucleoid cells had enlarged and shifted from the apices toward the center of the cell (Fig. 4). Nucleoids were characterized by decondensed DNA (reflected in an increase of the R/G ratio to 140 to 148; mean, 145.2 ± 0.4 [Table 4]) distributed evenly around the periphery of the nucleoid and core areas rich in RNA (R/G ratios of 267 [Fig. 4]). This is likely the stage described and shown by Robinow and Kellenberger (26). RNA-rich areas, with ratios in the 250 to 259 range, also occurred in the cytoplasm external but adjacent to the nucleoids. The cytoplasmic mean R/G ratio (210.6 ± 2.3) was higher than that for earlier periods when DNA was condensed, suggesting more active RNA synthesis and transport to the cytoplasm with decondensation of DNA. R/G ratios for peripheral portions of the cell remained unchanged from earlier samples (151.6 ± 0.2 [Table 4]).

FIG. 4.

Binucleoid and uninucleoid E. fishelsoni collected at 1000 h. Dimensions: ∼320 by 45 μm (A) and ∼330 by 55 μm (B). Other features are as described in the legend for Fig. 3. Note expansion of nucleoids, their shift toward the center of the cells, the concentration of decondensed DNA along periphery of nucleoid, and the high concentration of RNA in core of nucleoids.

(iii) Early afternoon.

Elongation of nucleoids continues until those of both uninucleoid and binucleoid cells reach approximately 75% of cell length (23). During this period of elongation, which in our samples extended until at least 1430 h, R/G ratios remained much as described for the samples from 1000 to 1100 h (Fig. 4). DNA remained decondensed (ratios of 140 to 149) and evenly dispersed around the periphery of the nucleoid. The interior core of the nucleoids, as well as areas immediately external to the nucleoidal DNA layer, continued to exhibit R/G ratios indicating RNA enrichment (245 to 255), cytoplasm external to these enriched areas remained high at ∼184 to 187, and the cell edge was unchanged at ∼150.

(iv) Evening.

Late in the day and into night (1640 and 2200 h), nucleoids within both uninucleoid and binucleoid cells were surrounded by material producing ratios previously seen only at the edge of cells (R/G ratio, ∼150) and were separated from the parent cell’s periphery by a layer of material yielding ratios characteristic of general cytoplasm (R/G ratio, 182 to 186 [Fig. 5]). Shifting between fluorescence and transmitted light microscopy demonstrated that the areas with R/G ratios of ∼150 were thickened zones surrounding nucleoids and that they were separated from, but structurally and visually similar to, the parental cell wall. This is consistent with electron micrographs which show nucleoids surrounded with thick, laminar material (23) (Fig. 3 and 5 and our unpublished results). We interpret this new layer as cell wall formation around maturing daughter cells.

FIG. 5.

Formation of mature daughter cells in binucleoid and uninucleoid E. fishelsoni collected at 1640 h. Dimensions: ∼520 by 65 μm (A) and ∼530 by 65 μm (B). Other features are as described in the legend for Fig. 3. Note formation of presumptive cell wall material around nucleoids and the separation of this wall material from the parental wall by a thin layer of cytoplasm. Cells for this figure were collected at the same time as those shown in Fig. 6A through C, emphasizing that stages in the epulo life cycle are not precisely synchronized in time and between individual host fish.

Evening samples also contained cells with well-developed walls, with DNA evenly dispersed immediately below the walls, and with little or no cytoplasm external to the DNA layer. Such cells were of a size and structure similar to daughter cells within parent cells and are interpreted as daughter cells following their release.

(v) Early morning.

In some daughter cells collected between 1640 and 0500 h, the DNA located at one or both apices of the cell was very highly condensed (R/G ratio, 96 to 115; mean, 111.4 ± 1.9 [Table 4]) compared to the peripheral DNA (R/G ratios, 130 to 140; mean, 138.3), and DNA near the apices appeared thicker than that along the lateral walls (Fig. 6B C). We termed these condensed, thickened areas of apical DNA “caps.”

Throughout the night, one encounters daughter cells with no (Fig. 6A), one (Fig. 6C), or two caps (Fig. 1F and 6B). In many cells collected at 0430 and 0500 h, however, the DNA was arranged in a figure-8 form, with the apical caps of condensed DNA located at the top and bottom of the “8,” and with decondensed DNA near the center of the cell displaced inward (Fig. 6B and C) to produce a pinched appearance. This pinching appears to be independent of any obvious cytological changes such as formation of cross walls.

Other cells sampled during these hours, also with distinct caps of condensed DNA, exhibited complete or nearly complete separation of the decondensed DNA located more centrally (Fig. 6D and E), suggesting that this stage represents a step en route from diffuse distribution of decondensed DNA to its segregation to form daughter nucleoids. Additional condensation and aggregation of the DNA around the caps could subsequently produce the next distinct stage of condensed, apical DNA masses noted in samples from 0640 h (above). During this period of apparent dynamism with respect to DNA distribution and state, R/G ratios for cytoplasm (204.2 ± 2.0 [Table 4]) and periphery (151.5 ± 0.2) remained similar to those recorded at other stages in the life cycle.

DISCUSSION

The morning nucleoid.

Previously published electron micrographs (14, 23) show specimens fixed in late afternoon or evening and show considerable complexity of epulo ultrastructure, including a trend for the nucleoid regions to be clearly separated from surrounding materials. Where a structure responsible for this separation has been visible, it has generally appeared thick and occasionally laminar and has been interpreted as wall material. Specimens used for Fig. 2 were fixed shortly after the first appearance of apical nucleoids of condensed DNA in early morning and demonstrate that even at this early stage in the life cycle, the nucleoid appears to be separated from the cytoplasm. This is clearest in Fig. 2A, where a fine, smoothly curving line surrounds the nucleoid. The identity of the delineating feature and its significance remain unclear, but spore formation in Bacillus subtilis involves the surrounding of an incipient spore by maternal cell membrane and the subsequent formation of a spore coat (17). Angert et al. (1) suggest that similar events occur during daughter cell and endospore formation in a close relative of E. fishelsoni, Metabacterium polyspora.

Internally, the nucleoid at this time appears dominated by elongate and possibly folded strands reminiscent of condensed chromosomes of dinoflagellates and other bacteria (see Fig. 3, 4, and 27 in reference 30 and the discussion of them in reference 26). We assume these structures are composed primarily of DNA because similar materials are not evident in other parts of the cell, and fluorescence staining with acridine orange (mean R/G ratio = 128.3, typical of condensed DNA) and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (reference 23 and our unpublished results) demonstrates the presence of condensed DNA only in these nucleoids. Possible coarse aggregation of prokaryote DNA (reviewed in reference 26) in fixatives containing glutaraldehyde cannot account for the condensed strands seen in electron micrographs (Fig. 2), because dispersed nucleoidal materials similar to more conventional views of bacterial nucleoids are evident in micrographs of cells treated with the same fixatives but later in the cell cycle (14, 23).

Finally, R/G ratios in zones adjacent to the nucleoids indicate some RNA enrichment (R/G ratio = 193 to 210 [Fig. 3A and B]), but values are much lower than those recorded for late-morning cells with decondensed DNA (R/G ratio = 250 to 267). While not definitive, this suggests less transcriptional activity of condensed nucleic acid compared to decondensed material, parallelling observations from eukaryote chromosomes.

Treatment with RNase generated additional support for this hypothesis (Table 4). First, the highest values of R/G ratios in cytoplasm occurred either in cells with enlarged nucleoids (mean R/G = 210) or in those in transition with some DNA in condensed caps and some remaining dispersed (mean = 204). Note that ratios for cytoplasm dropped to zero after RNase treatment due to the loss of all red fluorescence from single-stranded nucleic acid. Second, ratios for apical nucleoids declined slightly (128.3 to 124.8) and those for apical caps remained essentially unchanged (111.4 to 112.1), supporting the interpretation that there is little RNA in the nucleoids during such periods and that DNA is condensed, double stranded, and generally not transcribing. In contrast, the mean ratio for the elongate nucleoids declined from 145.2 to 136.7. This decline is consistent with the contention that RNA is common in such nucleoids, as indicated by RNA-enriched zones within nucleoids in Fig. 4. Digestion of RNA in cells with expanded nucleoids left a ratio higher (136.7) than that for similarly treated cells with compact nucleoids (112.1 and 124.8), indicating that a greater fraction of the DNA in enlarged nucleoids is in single-stranded form than in compact nucleoids. Finally, ratios in small areas of enlarged nucleoids (results not shown but available from the authors) declined to zero after RNase treatment (zeros were not used in calculations of R/G ratios for Table 4), again emphasizing the apparent concentration of RNA within the central regions of expanded nucleoids.

Cell size, volume, and DNA content.

E. fishelsoni appears to be not only the largest known eubacterium but the most variable in size as well. Most of our data derive from studies on large cells (length, >150 μm), supplemented by work with one much smaller group (30 to 35 μm). Four observations make it clear that group 0 cells in fact are small E. fishelsoni. First, the production of one or two nucleoids or daughter cells within the parent cell as well as the elongate cigar shape of E. fishelsoni cells is consistent throughout the size range and may, in fact, extend well below this range (Fig. 1C and D).

Second, length-width relationships (from which volume was estimated) are consistent among epulo cells across the size range. We performed a linear regression on log10(length) and log10(volume) data for groups 0 and I to VI (Table 2) supplemented with data from cells of intermediate length not used for DNA analyses (length ranges of four groups: 46 to 55, 65 to 75, 94 to 109, and 113 to 137 μm); the regression [log10(volume) = −5.1 + 2.8 log10(length); r2 = 0.99, df = 9] indicates consistent length-volume, and therefore length-width, relationships across the entire span of cell sizes.

Third, there is a consistent pattern in the range of sizes of cells collected from hosts taken at different times of day and night (Table 1) (23). Small- to medium-sized cells (length, ∼30 to 150 μm) prevail in the morning (0600 to 0800 h), average length increases during the day to a maximum in late afternoon (ca. 1600 h), and length declines thereafter to a minimum in very early morning (2400 to 0400 h). Consistent with this, very small (length, <50 μm) cells are essentially absent during the day, occur in combination with a wide length range of cells prior to midnight, often dominate epulos in fish sacrificed between midnight and 0400 h, and decline in frequency and eventually disappear in later morning samples.

Finally, preliminary staining of very early morning samples with fluorescent probes developed by Angert et al. (2) for large E. fishelsoni yielded positive binding to small as well as intermediate sized cells (data not shown).

The roughly 30-fold increase in both cell volume and total DNA for groups I to VI clearly exceeds the ∼3.3-fold difference or the ∼10.6-fold difference expected if DNA quantity were proportional to length or surface area, respectively. Inclusion of group 0 in calculations demonstrates a direct correlation between cell volume and DNA content across the entire size range of E. fishelsoni measured (length, ∼30 to 500 μm), with DNA content differing >2,000-fold among these cells. If structurally similar cells in the 10-to-15-μm size range (Fig. 1) are in fact E. fishelsoni and adhere to the same pattern of proportionality, as we suspect based on observations of intermediate sized cells, they would extend the ratio of cell volume and DNA in largest to smallest cells by at least an additional order of magnitude (based on the regression described above, a 10-μm-long cell [the approximate size of daughter cells in the smallest parent cell of Fig. 1D] would have a volume of ∼0.005 μm3, ∼1/68,000 the volume and DNA content of a 500-μm-long cell.

DNA content and distribution to daughter cells.

Flow cytometric studies of E. coli show that DNA content varies systematically among other bacterial cells, and to some degree with cell size, but this variation usually represents only two- to eightfold increases over the amount of DNA within a single genome (29). We do not know the size of a unit genome in E. fishelsoni, but copy number in large cells appears to be very great. There are large quantities of DNA in large cells, there is localization of DNA-specific stains to nucleoids, and fluorescence ratios indicate condensation of DNA when electron micrographs show darkly staining, elongate structures in the nucleoids.

Many copies of a unit genome may support the growth, mobility, and apparently active metabolism described for these giant bacteria (9, 24, 26). Multiple copies of an entire genome would also support rapid production of daughter cells by uncoupling potentially rate-limiting DNA replication from DNA-subdivision and other cell division events.

In epulos there is low variance in DNA content for cells of a given size, an arithmetic increase in DNA content with cell volume, and a ratio of DNA in the two nucleoids of binucleoid cells that is not significantly different from 1.0 (Table 3). Thus, there appears to be a mechanism for approximately equal subdivision of large quantities of DNA between two daughter cells during the two rather distinct diurnal and nocturnal phases of the life cycle. During the day, organized subdivision of DNA to daughter cells occurs when both parent cells and nucleoids are growing, and replication must be active to maintain the ratio of DNA to cell volume. At night, parental cells produce smaller daughter cells (usually 50 to 75% of parent cell length) and replication is likely halted or perhaps proceeding at low levels.

The mechanism for subdivision of DNA may be more complex than that inferred by simple formation of equivalent daughter cells. We have recorded E. fishelsoni cells with three daughter cells of roughly equal size, and some morphotypes consistently produce up to seven similarly sized daughter cells (8). We lack data on DNA content and dynamics in these morphotypes.

Changes in state and distribution of DNA with stages of the cell cycle.

Clearly, a complex series of events attends growth and maturation of epulos. Quantitative fluorescence cytochemistry demonstrates that DNA in the largest epulos exceeds amounts in the smallest cells by 4 to 5 orders of magnitude and probably exceeds amounts in most other bacteria by an even greater margin. Such large quantities of DNA could pose problems for a cell undergoing the dynamic processes of DNA replication, condensation and decondensation, and systematic distribution to duplicate nucleoids.

Organization of DNA into discrete structures, as suggested by electron micrographs and strong, localized fluorescence signals from small, delimited morning nucleoids, may overcome some of these problems. Structures apparent within early-morning nucleoids (collected between 0640 and 0900 h) are reminiscent of condensed chromosomes of other bacteria and dinoflagellates (26, 30), but we lack details of their fate during the remainder of the day. Previous electron micrographs of sections through enlarged nucleoids and immature daughter cells generally lack evidence of such structures (14, 23), although diffuse, darkly staining zones are evident in the interior cytoplasm of a daughter cell shown in a figure by Clements and Bullivant (Fig. 2 of reference 9). In any event, by late morning (1000 to 1100 h), the nucleoids exhibit evidence of DNA decondensation (increased R/G ratios) and increased transcriptional activity (RNA enrichment within the nucleoid and in adjacent cytoplasm), and as the day and evening progress DNA appears to continue decondensation and widespread dispersion.

Condensation of DNA and its association into duplicate caps by an unknown mechanism appear to presage the formation of daughter nucleoids and eventually daughter cells. Conversely, replication with formation of a single cap could be a mechanism for increasing DNA content of a cell line and supporting additional increases in cell dimensions within that line.

Such events may be carried out without interruption of normal cell functions. Even as caps form from highly condensed DNA, the cells retain dispersed and probably actively transcribing DNA in a layer immediately adjacent to the cytoplasm (Fig. 6B through E). Large quantities of cytoplasmic RNA, reflected in our high R/G ratios for cells throughout the life cycle, and intense, cell-wide fluorescence signals obtained when cells were probed with specific 16S ribosomal subunit sequences (2), collectively suggest that cells are metabolically active at all stages.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding was provided by the Tobias Landau Foundation; grant 3716-87 from the National Geographic Society; the Organized Research Fund of Northern Arizona University (NAU); and the Department of Zoology, Tel Aviv University.

L. Fritz performed fixations in Eilat and, assisted by M. Sellers and R. Earhart, the electron microscopy at NAU. Collections in Israel were undertaken at the Interuniversity Institute of Eilat with the gracious assistance of Avi Baranes as well as many resident faculty, technicians, and students. Collecting permits were provided by the Nature Protection Society (NPS) of Israel; particular thanks are due Nurit Popper of the NPS for assistance in arranging permits and facilitating work. Robyn O’Reilly prepared the computer maps of cells. Gordon Southam and several anonymous reviewers provided invaluable critiques of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angert E R, Brooks A E, Pace N R. Phylogenetic analyses of Metabacterium polyspora: clues to the evolutionary origin of daughter cell production in Epulopiscium species, the largest bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1451–1456. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1451-1456.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angert E R, Clements K D, Pace N R. The largest bacterium. Nature. 1993;362:239–241. doi: 10.1038/362239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arndt-Jobin D J, Jobin T M. Fluorescence labeling and microscopy of DNA. Methods Cell Biol. 1989;30:417–448. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60989-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohm N, Sprenger E, Sandritter W. Absorbance and fluorescence cytometry of nuclear Fuelgen DNA. In: Thaer A A, Sernetz M, editors. Fluorescence techniques in cell biology. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bresler V, Fishelson L. Microfluorometrical study of benzo(a)pyrene and marker xenobiotics bioaccumulation in the bivalve Donax trunculus from clean and polluted sites along the Mediterranean shore of Israel. Dis Aquat Org. 1994;19:193–202. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bresler V, Yanko V. Chemical ecology: a new approach to the study of living benthic epiphytic foraminifera. J Foraminifer Res. 1995;25:267–279. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caron G N-V, Bradley R A. Viability assessment of bacteria in mixed populations using flow cytometry. J Microsc. 1995;179:55–61. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clements K D, Sutton D C, Choat J H. Occurrence and characteristics of unusual protistan symbionts from surgeonfishes (Acanthuridae) of the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Mar Biol. 1989;102:403–414. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clements K D, Bullivant S. An unusual symbiont from the gut of surgeonfishes may be the largest known prokaryote. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5359–5362. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5359-5362.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crissman H, Steinkamp J. Cytochemical techniques for multivariate analysis of DNA and other cellular constituents. In: Melamed M, Lindmo T, Mendelsohn M, editors. Flow cytometry and sorting. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Liss; 1990. pp. 227–241. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darzynkiewicz Z. Mammalian cell cycle analysis. In: Fantes P, Brooks R, editors. The cell cycle: practical approaches. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1993. pp. 45–69. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darzynkiewicz Z, Kapuscinski J. Acridine orange: a versatile probe of nucleic acids and other cell constituents. In: Melamed M, Lindmo T, Mendelsohn M, editors. Flow cytometry and sorting. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Liss; 1990. pp. 291–314. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Domkina L K, Bresler V M, Simanovsky L N. Changes in the structure of chromatin in the nuclei of hepatocytes of rats trained to hypoxia. Bull Exp Biol (Moscow) 1976;81:370–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13a.Fishelson, L. Unpublished data.

- 14.Fishelson L, Montgomery W L, Myrberg A A., Jr A unique symbiosis in the gut of tropical herbivorous surgeonfish (Acanthuridae: Teleostei) from the Red Sea. Science. 1985;239:49–51. doi: 10.1126/science.229.4708.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghiorse W C, Balkwill D I. Enumeration and morphological characterization of bacteria indigenous to subsurface environments. Dev Ind Microbiol. 1983;24:213–222. [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Grim, N. Unpublished data.

- 16.Haugland R P. Handbook of fluorescent probes and research chemicals. 6th ed. New York, N.Y: Molecular Probes, Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Losick R, Youngman P, Piggot P J. Genetics of endospore formation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Genet. 1986;20:625–669. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.003205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McFeters G A. Acridine orange staining reaction as an index of physiological activity in Escherichia coli. J Microbiol Methods. 1991;13:87–93. doi: 10.1016/0167-7012(91)90009-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McFeters G A. Physiological assessment of bacteria using fluorochromes. J Microbiol Methods. 1995;21:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0167-7012(94)00027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Millard P J, Roth B L, Kim C H. Fluorescence-based methods for microbial characterization and viability assessment. Biotechnol Int. 1997;1:291–305. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montgomery W L, Fishelson L, Myrberg A A., Jr Feeding ecology of surgeonfishes (Acanthuridae) in the northern Red Sea, with particular reference to Acanthurus nigrofuscus (Forsskal) J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 1989;132:179–207. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montgomery W L, Galzin R. Seasonality in gonads, fat deposits and condition of tropical surgeonfishes (Teleostei: Acanthuridae) Mar Biol. 1993;115:529–536. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montgomery W L, Pollak P E. Epulopiscium fishelsoni, N.G., N. Sp., a protist of uncertain taxonomic affinities from the gut of an herbivorous reef fish. J Protozool. 1988;35:565–569. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montgomery W L, Pollak P E. Gut anatomy and pH in a Red Sea surgeonfish, Acanthurus nigrofuscus. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1988;44:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 24a.Montgomery, W. L., and P. E. Pollak. Unpublished data.

- 25.Neidhardt F C, Ingraham J L, Schaechter M. Physiology of the bacterial cell: a molecular approach. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinow C, Kellenberger E. The bacterial nucleoid revisited. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:211–232. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.2.211-232.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt E L, Paul E A. Microscopic methods for soil microorganism. In: Page A L, Miller R H, Keeney D R, editors. Methods of soil analysis, part 2. Madison, Wis: American Society for Agronomy and Soil Science Society of America; 1982. pp. 803–814. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma D K, Prasad D N. Rapid identification of viable bacterial spores using a fluorescence method. Biotech Histochem. 1992;67:27–32. doi: 10.3109/10520299209110001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skarstad K, Boye E, Steen H B. Timing of initiation of chromosome replication in individual Escherichia coli cells. EMBO J. 1986;5:1711–1717. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spector D L. Dinoflagellate nuclei. In: Spector D L, editor. Dinoflagellates. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1984. pp. 107–147. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Beelen P, Fleuren-Kemila A K, Huys M P A, van Montfort A C P, van Vlaardingen P L A. The toxic effects of pollutants on the mineralization of acetate in subsoil microcosms. Environ Toxicol Chem. 1991;10:775–789. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Dilla M A, Langlois R G, Pinkel D. Bacterial characterization by flow cytometry. Science. 1983;220:620–622. doi: 10.1126/science.6188215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yossefi S, Oschry Y, Levin L M. Chromatin condensation in hamster sperm: a flow cytometric investigation. Mol Reprod Dev. 1994;37:93–98. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080370113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]