Abstract

European starlings are one of the most abundant and problematic avian invaders in the world. From their native range across Eurasia and North Africa, they have been introduced to every continent except Antarctica. In 160 years, starlings have expanded into different environments throughout the world, making them a powerful model for understanding rapid evolutionary change and adaptive plasticity. Here, we investigate their spatiotemporal morphological variation in North America and the native range. Our dataset includes 1217 specimens; a combination of historical museum skins and modern birds. Beak length in the native range has remained unchanged during the past 206 years, but we find beak length in North American birds is now 8% longer than birds from the native range. We discuss potential drivers of this pattern including dietary adaptation or climatic pressures. Additionally, body size in North American starlings is smaller than those from the native range, which suggests a role for selection or founder effect. Taken together, our results indicate rapid recent evolutionary change in starling morphology coincident with invasion into novel environments.

Subject terms: Evolutionary ecology, Invasive species

Introduction

European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) were introduced into North America in 1890 and 1891 from their native range in Europe. From a small founder population of approximately 100 birds, their population expanded to ~ 200 million within a century but has recently been estimated between 85.9 and 93.3 million birds1–3. By 1942, starlings had spread to the West Coast of the United States and now inhabit all U.S. states, most of Mexico, and parts of Southern Canada4. They were also introduced to New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, and Argentina (between 1856 and 1987)5–7. A recent study estimated that European starlings are the second most abundant wild bird in the world, with a global population of 1.3 billion, ranked behind only the house sparrow (Passer domesticus) at 1.6 billion8.

These multiple successful introductions of European starlings to different parts of the world make this species an exemplar of adaptation to new environments, population size expansion, and dispersal. This multi-continental single-species system can therefore offer important windows into the ecological, genetic, behavioral, and physiological variables which enable avian invasions—and, more broadly, drive evolutionary change over short time scales. Importantly, European starlings in the U.S. pose substantial ecological and economic problems by consuming agricultural crops, spreading diseases to livestock and consuming their food, colliding with aircraft, and competing with native birds such as Sapsuckers (Sphyrapicus sp)9–16. Therefore, studying this species from a comparative population perspective serves two key purposes: to better understand evolutionary change over short time scales and to illuminate aspects of their invasion history and population dynamics which can inform management efforts and conservation of native species.

Consistent with their invasion history, even a modest sampling of birds from the United Kingdom shows higher mitochondrial haplotype diversity (h = 0.972) and nucleotide diversity (π = 0.7%), than the invasive populations in North America (h = 0.876, π = 0.5%), Australia (h = 0.703, π = 0.5%), or South Africa (h = 0.779, π = 0.5%)17–19. Although, due to a lack of comprehensive genetic data from starlings across the entirety of their native range, the full extent of their native genetic diversity is not well characterized. Therefore, comparisons of genetic diversity between native and invasive ranges are currently provisional. Relatedly, the source population for many of these introductions is historically documented as Britain, but this has not been confirmed with genetic data7. Comparisons between invasive ranges show that North America (NA) harbors higher mitochondrial haplotype diversity than Australia or South Africa, which may be due to rapid expansion in NA facilitated by climate matching with the native range. Yet, the effective population size, estimated from nuclear markers, is slightly larger in Australia than in North America, possibly due to differences in propagule pressure between invasive ranges20.

There are ten recorded starling introductions to North America7. According to historical records, the only populations which became established were those from the introductions to New York (1890, 1891) and Oregon (1889, 1892). Those in Oregon persisted only until 1900. Genetic analyses of starlings in the United States have revealed a lack of geographic population structure using allozymes, mitochondria, and nuclear markers17,20,21. The apparent lack of geographic population genetic structure across the U.S. today does not refute a single New York origin for modern starlings across the entire continent. This large panmictic North American population is also likely maintained by east–west and sometimes erratic, opportunistic, migratory patterns22. This contrasts with Australia where repeated introductions, beginning in 1865 and continuing until 1881, are at least partly evident in two geographically restricted genetic groups today18,23.

Clearly, the relatively small founder population size of starlings in North America and subsequent loss of genetic diversity was not an obstacle to their invasion success, a trend which has also been observed in other invasive species24–28. The North American starling population experienced a reduction in genetic diversity followed by a rapid expansion, as shown with reduced representation genomic data20. This rapid rate of population growth following the starlings’ arrival in NA may have enabled an escape from the deleterious impact of genetic drift and, instead, provided the conditions for adaptive change. Genotype-environment analyses have identified a suite of single-nucleotide polymorphisms which are correlated with temperature and precipitation in both NA and Australian starling populations20,29. This suggests that continent-wide climatic variation may have contributed to heterogenous spatial patterns in starlings driven by adaptation, and which may be evident in external morphometric traits. This idea is supported by an earlier study of 168 starlings across NA, where wing length, beak length and other aspects of body composition covaried with latitude30. Introduced starlings in New Zealand also exhibit geographic variation in morphometric traits such as bill size and shape31. And more broadly, intraspecific clinal variation in bird body size has been shown to be driven by maximum annual summer temperatures across several taxa, although determining the contribution of selection versus plasticity remains a challenge32,33.

The unique population history of European starlings in North America, together with results from recent genetic analyses which suggest an environmental signal of selection, provide the framework for our exploration of their morphological variation. Here, three fundamental questions were addressed: (1) Is starling morphology in North America different than that of the population in the native range? (2) Has starling morphology changed since the time of their introduction to North America? (3) Is modern starling morphology spatially structured across the United States? We measured beak length, wing chord and tarsus length in 1217 birds. Historical specimens dating back to 1816 were measured from museum ornithology collections. Measurements from modern NA starlings collected at dairies and feedlots were also included (provided by the United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Wildlife Services program; USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services). Measurements were also collected from modern starlings from Wales, UK (provided by APHA Shrewsbury, Veterinary Investigation Centre, Shrewsbury, UK). The primary comparison here is between birds from North America and those from the native range in Eurasia, though we also included specimens from the starling population in New Zealand which provided another independent invasive population as comparison.

Materials and methods

Specimens

All specimens included in this study were identified by adult plumage. Data were collected from a total of 743 museum skins spanning 201 years (females = 286, males = 397, sex N/A = 60) with an additional 337 fresh specimens (females = 116, males = 221) supplied by the USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services, and 137 fresh specimens supplied by APHA Shrewsbury (sex N/A) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Starling specimens used in this study: historical skins from museum collections and modern birds.

| Starling specimens | specimen type | N | Females | Males | Sex N/A | Localities | Dates collected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America (NA) | US states | ||||||

| AMNH—NA | museum historical | 123 | 50 | 68 | 5 | AK, CT, FL, IL, MA, MD, NJ, NY, PA, RI, WI | 1889–2015 |

| DMNH—NA | museum historical | 44 | 18 | 22 | 4 | CO | 1939–2016 |

| FMNH—NA | museum historical | 289 | 128 | 134 | 27 | IL, MI, WI | 1938–2018 |

| USDA—NA | modern | 315 | 111 | 204 | – | AZ, CA, CO, IA, ID, IL, KS, MN, MO, NE, NC, NH, NV, NY, OR, TX, VT, WA, WI | 2016, 2017 |

| USDA—NA | modern | 22 | 5 | 17 | – | AZ | 2020 |

| Native range | Countries | ||||||

| AMNH—native range | museum historical | 101 | 21 | 73 | 7 | England, Germany, Latvia, Scotland, Sweden | 1816–1965 |

| FMNH—native range | museum historical | 11 | 4 | 7 | - | England, Germany | 1888–1921 |

| NHM, Tring—native range | museum historical | 107 | 38 | 57 | 12 | Azerbaijan, England, Germany, India, Iran, Iraq, Latvia | 1859–1975 |

| APHA—native range | modern | 137 | - | - | 137 | Wales, UK | 2021, 2022 |

| New Zealand | Regions | ||||||

| MONZ—NZ | museum historical | 68 | 27 | 36 | 5 | North Island, South Island, Raoul Island, Ocean Island | 1927–2017 |

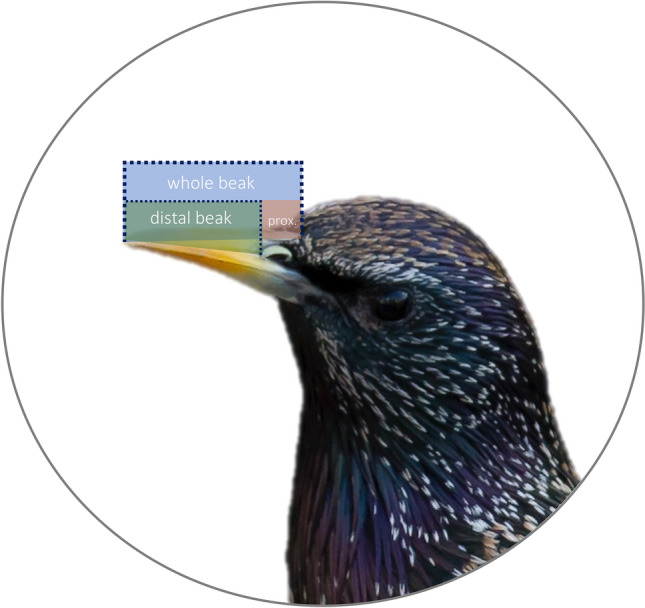

Measurements taken on all specimens were: whole beak length (or culmen length) originating at the base of the cranium, distal portion of the beak (distance between nares and distal tip of the beak), tarsus length and wing chord length34,35 . The measurement for the proximal portion of the beak, from the base of the cranium to the nares, was calculated by subtracting the distal beak measurement from the whole beak measurement (Fig. 1). Digital calipers were used for beak and tarsus measurements and stopped wing rulers were used for wing chord measurements. All digital caliper measurements were taken in millimeters to the nearest 0.01 mm, and wing chord was measured to the nearest 0.5 mm. Digital calipers were zeroed between each measurement. Each measurement was taken three times for each bird, and the average of the three measurements was used.

Figure 1.

Starling measurements: whole beak, distal beak, proximal beak. Image adapted from Wikimedia Commons, by Pierre Selim.

Museum skins were accessed from the collections of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), Field Museum of Chicago (FMNH), Denver Natural History Museum (DMNH), Natural History Museum at Tring (NHM), UK and Te Papa Museum in New Zealand (MONZ). Museum specimens from the native range included birds from England, Germany, Latvia, Azerbaijan, Iran, Iraq, and India. Subspecies distinctions have been assigned to populations from across the native range, though this classification system has not been recently reviewed. The temporal ranges of our datasets from museum specimens are: 159 years (1816–1975) for the native range; 127 years for North America (1890–2017); and 90 years for New Zealand (1927–2017). To compare with the data from museum specimens, 337 modern starlings collected from January-March 2016 and January–February 2017 at animal agriculture facilities within 20 states across the U.S. were also included (Table 1). An additional 22 starlings were collected from a landfill in Arizona in January 2020 (See supplemental material).

Three to fifteen birds were collected from each agricultural facility site, at 2–8 sites per state, and sites were selected ≥ 5 km from nearest sites to maximize the geographic range of sampling. Sample sizes greater than 15 birds were only collected from single sites within three states: Texas, Nevada, and Arizona. United States Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Services personnel used a handheld GPS unit to record the latitude and longitude of each collection site for subsequent spatial analyses.

The National Wildlife Research Center’s (USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the collection and use of starlings for this study (QA-2572, S.J. Werner- Study Director). Samples were utilized for multiple research objectives20,36. Live-trapped starlings in the U.S. were euthanized using procedures approved by the American Veterinary Medical Association, and in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines (e.g., C02). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. These bird collections were authorized by Federal Depredation Permits issued by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and, where necessary, by state scientific collection licenses. Because European starlings are invasive to the U.S., no federal scientific collecting permit was necessary for these collections. Additionally, this collection of starlings likely had no effect on the overabundant populations of starlings often found in association with animal agriculture facilities2.

Initial practice measurements were performed with three museum specimens and a sub-sample of five birds37. Once accurate replication among observers was achieved, morphometric measurements of 337 starlings were taken by three individuals in July–August 2018. Starlings were then frozen and maintained in chest freezers at − 20 °C. Birds were aged and sexed using plumage characteristics as described by Blasco-Zumeta and Heinze38.

Modern starling specimens (N = 137) were also included from the native range in Wales, UK, from salvage birds that died in collisions in 2021 and 2022 (provided by APHA Shrewsbury, Veterinary Investigation Centre, Shrewsbury, UK).

Ethics declarations

The collection of live starlings for this study was approved by the National Wildlife Research Center’s (USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (QA-2572, S.J. Werner- Study Director). All birds were euthanized using procedures approved by the American Veterinary Medical Association and authorized by Federal Depredation Permits issued by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service and, where necessary, by state scientific collection licenses.

Data analysis

Correction for museum skins versus modern specimens

Our analyses included both museum skin specimens and fresh specimens. Shrinkage over time in museum skins has been reported in various passerine bird species, such as house sparrows (Passer domesticus), Tennessee warblers (Leiothlypis peregrina), and great grey shrikes (Lanius excubitor)39–41. The precise degree of shrinkage is specific to certain anatomical elements, with wings showing more consistent trends of shrinkage than tarsi or beaks, due to the inclusion of a boney joint in the wing40. To address this issue and combine museum and fresh samples into one analysis, correction factors have been derived. These correction factors are ideally meant to be species-specific and are related to nuances in bird body size, morphology, and soft tissue anatomy40,42. Without a starling-specific correction factor for museum specimen shrinkage, we used an average for each measurement which is derived from the three aforementioned passerine species. We applied correction factors to all measurements taken from fresh specimens, where we multiplied beak length measurements by 0.969, wing chord by 0.985 and tarsus by 0.975. We then performed all analyses with these correction factors in place.

Sexual dimorphism

ANOVA [location (sex)]

To evaluate the contribution of sexual dimorphism to the variance in each trait, three ANOVA tests were run. One for each location (United States, native range, New Zealand) with sex as an independent qualitative variable, and the five measurements (wing length, tarsus length, whole beak length, proximal beak length, distal beak length) as dependent variables.

Change over time

Fixed effect regression model

To further parse the relationships between location, sex, time, and each of the five measurements, fixed effect regressions were performed where we controlled for body size.

All 1217 specimens were included here. First, a principal component analysis was run which included all five measurements together. Then, PC1 scores for each individual bird were extracted and used as a fixed effect in the model to control for body size43. Time (since 1816, the oldest specimen in our study), location (North America, native, New Zealand) and sex (F, M, N/A) were included as interaction terms, and each measurement was a dependent variable.

Linear regressions

We also performed linear regressions with time as a continuous variable with each of the five measurements (wing length, tarsus length, whole beak length, proximal beak length, distal beak length) partitioned by different regions: Native range dataset, 206 years (1816–2022) N = 392; North American dataset 130 years (1890–2020) N = 758; and New Zealand 90 years (1927–2017) N = 68 (Figs. 2a,c, 3a–c).

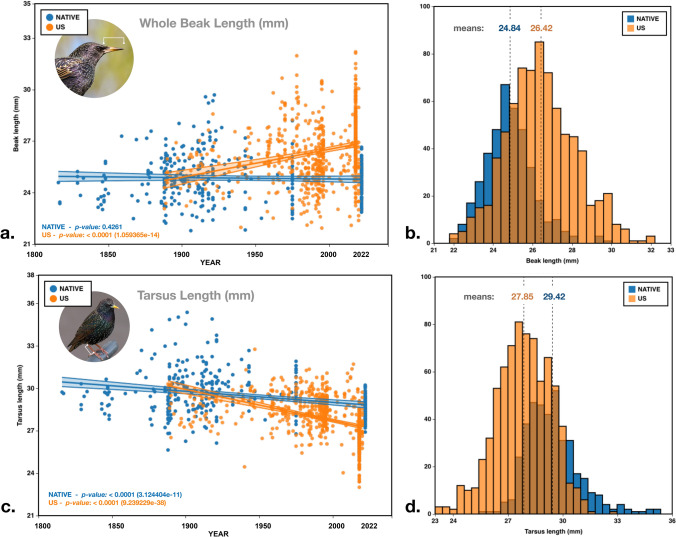

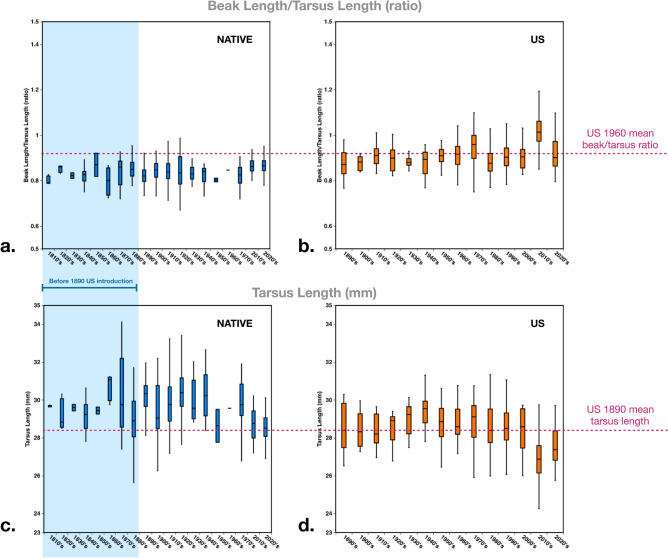

Figure 2.

(a) Whole beak length (mm) over time, native range 1816–2022 (blue), p value = 0.4261; introduced U.S. range 1890–2020 (orange), p value < 0.0001 (1.059365e−14). (b) Histogram of whole beak length (mm), native range (blue), introduced U.S. range (orange). (c) Whole tarsus length (mm) over time, native range 1816–2022 (blue), p value < 0.0001 (3.124404e−11); introduced U.S. range 1890–2020 (orange), p value < 0.0001 (9.239229e−38). (d) Histogram of whole tarsus length (mm), native range (blue), introduced U.S. range (orange).

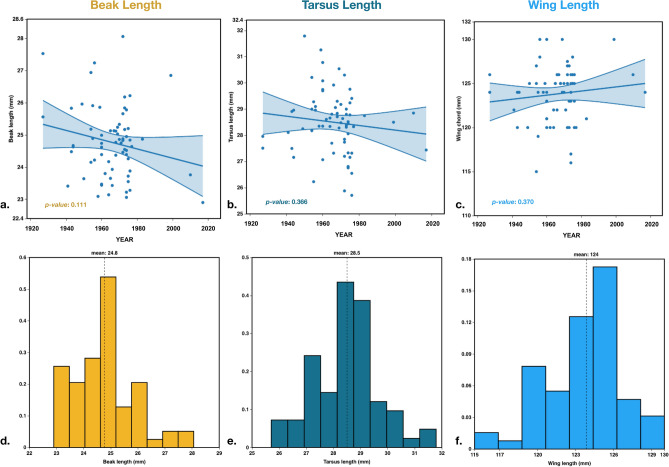

Figure 3.

(a) New Zealand: whole beak length (mm) over time, 1927–2017, p value = 0.111. (b) New Zealand: tarsus length (mm) over time, 1927–2017, p value = 0.366. (c) New Zealand: wing length (mm) over time, 1927–2017, p value = 0.370. (d) Histogram of beak lengths (mm) from New Zealand. (e) Histograms of tarsus lengths (mm) from New Zealand. (f) Histograms of wing lengths (mm) from New Zealand.

Comparisons between native range and invasive U.S. population

20 years after introduction to North America

To determine if differences between populations can be observed shortly after introduction of starlings to the United States, the North American and native range datasets were subsampled to include the same overlapping 20-year period from 1890 to 1910 (native range, N = 53; North America, N = 24), and two-tailed T-tests were performed to compare differences between population means (Table 2 bottom, Fig. 4).

Table 2.

Means for all starling measurements in this study organized by region (North America, native range, New Zealand), derived from raw data for museum specimens, and corrected values for fresh specimens (to account for potential shrinkage and enable comparison with data from historical specimens).

| Means (raw data) | Beak length (mm) | Tarsus length (mm) | Distal beak Length (mm) | Proximal beak length (mm) | Wing length (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America (NA) all | 26.42 | 27.85 | 18.25 | 8.17 | 123.10 |

| NA museum skins | 25.88 | 28.65 | 18.37 | 7.52 | 123.55 |

| NA, USDA 2017 | 27.33 | 26.68 | 18.09 | 9.24 | 122.63 |

| NA, USDA 2020—Arizona | 25.20 | 27.54 | 18.06 | 7.14 | 120.19 |

| NA 1890–1910 | 25.02 | 28.53 | 18.16 | 6.85 | 123.96 |

| NA, USDA 2017, East | 27.62 | 26.95 | 18.28 | 9.34 | 123.34 |

| NA, USDA 2017, Central | 27.51 | 26.94 | 18.16 | 9.35 | 122.70 |

| NA, USDA 2017, West | 27.37 | 26.53 | 17.94 | 9.43 | 122.37 |

| NA, USDA 2017, North | 27.55 | 26.90 | 18.14 | 9.41 | 123.10 |

| NA, USDA 2017, South | 27.28 | 26.46 | 17.97 | 9.31 | 121.62 |

| Native Range all | 24.84 | 29.42 | 17.83 | 7.01 | 126.20 |

| Native range museum skins | 24.90 | 29.86 | 17.61 | 7.29 | 125.24 |

| Native range Europe only | 24.65 | 29.81 | 17.47 | 7.18 | 125.04 |

| Native range Asia only | 26.25 | 30.08 | 18.37 | 7.88 | 126.33 |

| Native range 1890–1910 | 24.79 | 30.12 | 17.68 | 7.11 | 125.89 |

| Native range modern UK | 24.73 | 28.62 | 18.25 | 6.48 | 127.97 |

| New Zealand | 24.77 | 28.50 | 16.49 | 8.28 | 123.82 |

| T-Tests (two-tailed) | Beak length | Tarsus length | Distal beak length | Proximal beak length | Wing length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

North America (1890–1910) Native range (1890–1910) |

0.408 | < 0.001 | 0.046 | 0.265 | 0.036 |

|

North America (2016, 2017, 2020) Native range UK (2021, 2022) |

< 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.112 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

P-values from T-tests comparing means between two populations, non-significant values in italics.

Significant values are in bold.

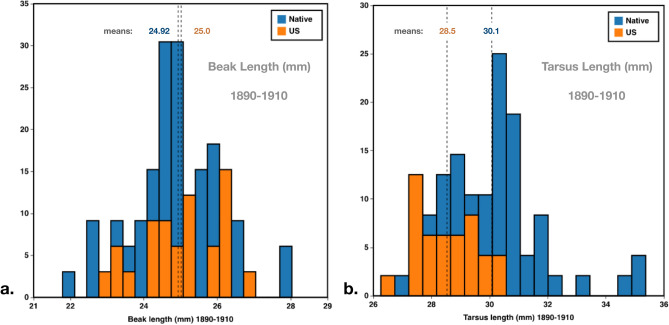

Figure 4.

(a) Histograms of beak lengths (mm) from 1890 to 1910 only, native range (blue), introduced U.S. range (orange). (b). Histograms of tarsus lengths (mm) from 1890 to 1910 only, native range (blue), introduced U.S. range (orange).

Modern starlings from native range compared with modern starlings in the U.S.

Average beak lengths from modern live-caught birds from the UK (2021, 2022) were compared to modern live-caught birds from the U.S. (2017, 2020) only. We generated a random subsample of 137 U.S. birds from those caught on agricultural facilities in 2018, combined with those caught at a non-agricultural facility in 2020. This was compared with 137 live-caught birds from a non-agricultural facility in Wales, UK (2021, 2022). Two tailed T-tests were performed to determine if the differences between means were significant (Table 2 bottom).

Comparison of modern starlings across the United States (East, Central, West; North, South)

Data from modern U.S. starlings were compared between the eastern, central, and western states and between northern and southern states (all from winter 2017, collected by USDA). Specimens were geographically grouped based on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) U.S. Climate Regions Map. ANOVAs were performed to test for differences between east, central and west, and between north and south for all five measurements (Table 4, Fig. 5a).

Table 4.

Summary statistics from ANOVA with all data separated by location (and sex within each location).

| All data (from ANOVA) | LS mean | Standard error | Lower bound | Upper bound |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEAK LENGTH | ||||

| US (all) | 26.11 | 0.08 | 25.96 | 26.26 |

| US females | 25.88 | 0.10 | 25.69 | 26.08 |

| US males | 26.91 | 0.08 | 26.75 | 27.08 |

| Native (all) | 25.02 | 0.09 | 24.85 | 25.19 |

| Native females | 24.39 | 0.15 | 24.09 | 24.69 |

| Native males | 25.13 | 0.11 | 24.91 | 25.36 |

| NZ (all) | 24.64 | 0.19 | 24.27 | 25.00 |

| NZ females | 24.70 | 0.21 | 24.27 | 25.13 |

| NZ males | 24.91 | 0.19 | 24.53 | 25.28 |

| TARSUS LENGTH | ||||

| US (all) | 28.17 | 0.07 | 28.03 | 28.30 |

| US Females | 27.81 | 0.08 | 27.64 | 27.97 |

| US Males | 27.91 | 0.07 | 27.78 | 28.05 |

| Native (all) | 29.01 | 0.08 | 28.86 | 29.16 |

| Native females | 29.66 | 0.17 | 29.32 | 30.00 |

| Native males | 30.10 | 0.13 | 29.85 | 30.35 |

| NZ females | 28.15 | 0.22 | 27.70 | 28.60 |

| NZ males | 28.67 | 0.19 | 28.28 | 29.05 |

| DISTAL BEAK LENGTH | ||||

| US (all) | 18.43 | 0.07 | 18.30 | 18.57 |

| US Females | 17.84 | 0.08 | 17.67 | 18.00 |

| US Males | 18.55 | 0.07 | 18.41 | 18.69 |

| Native (all) | 17.68 | 0.07 | 17.54 | 17.83 |

| Native females | 17.39 | 0.13 | 17.14 | 17.63 |

| Native males | 17.70 | 0.09 | 17.52 | 17.88 |

| NZ (all) | 16.61 | 0.16 | 16.30 | 16.92 |

| NZ females | 16.32 | 0.16 | 16.00 | 16.65 |

| NZ males | 16.61 | 0.14 | 16.32 | 16.89 |

| PROXIMAL BEAK LENGTH | ||||

| US (all) | 7.68 | 0.06 | 7.56 | 7.80 |

| US females | 8.05 | 0.08 | 7.89 | 8.21 |

| US males | 8.37 | 0.07 | 8.23 | 8.50 |

| Native (all) | 7.33 | 0.07 | 7.20 | 7.46 |

| Native females | 7.01 | 0.10 | 6.80 | 7.21 |

| Native males | 7.43 | 0.08 | 7.28 | 7.59 |

| NZ (all) | 7.42 | 0.14 | 7.14 | 7.70 |

| NZ females | 7.60 | 0.12 | 7.37 | 7.83 |

| NZ males | 7.75 | 0.10 | 7.55 | 7.95 |

| WING LENGTH | ||||

| US (all) | 123.50 | 0.17 | 123.16 | 123.84 |

| US females | 121.93 | 0.19 | 121.56 | 122.31 |

| US males | 123.91 | 0.16 | 123.60 | 124.23 |

| Native (all) | 125.91 | 0.19 | 125.53 | 126.29 |

| Native females | 124.10 | 0.39 | 123.32 | 124.87 |

| Native males | 126.07 | 0.29 | 125.49 | 126.65 |

| NZ (all) | 124.18 | 0.41 | 123.38 | 124.99 |

| NZ females | 122.89 | 0.58 | 121.73 | 124.05 |

| NZ males | 124.60 | 0.50 | 123.59 | 125.60 |

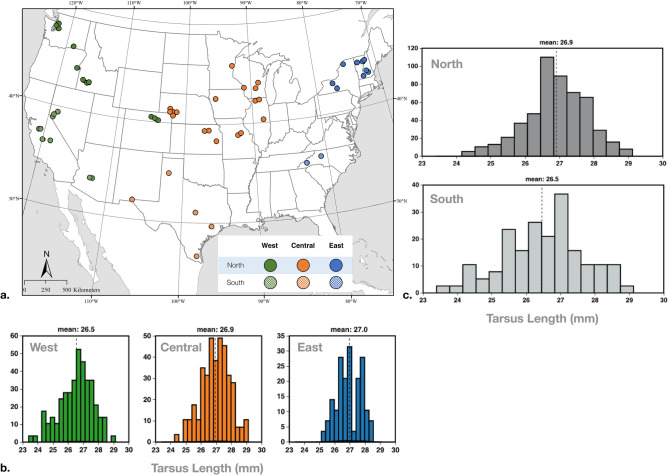

Figure 5.

(a) Map of USDA fresh specimen localities collected in winter 2017 only, data split by regions: West (green), Central (orange), East (blue); North (solid), South (dotted). Map created with ArcGIS Pro (software) 3.0.2 (version); source data for map features from ESRI ArcGIS Living Atlas (https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/en/home/). (b) Histograms of tarsus length (mm) differences between West, Central and East regions of the U.S. (c) Histograms of tarsus length (mm) differences between North and South U.S. regions.

East includes NOAA regions Northeast and Southeast: Vermont (VT), New Hampshire (NH), New York (NY), and North Carolina (NC). Central includes NOAA regions Upper Midwest, Ohio Valley, South, Northern Rockies and Plains: Wisconsin (WI), Illinois (IL), Minnesota (MN), Iowa (IA), Missouri (MO), Nebraska (NE), Kansas (KS), and Texas (TX). West includes NOAA regions Northwest, West, and Southwest: Idaho (ID), Nevada (NV), Colorado (CO), Arizona (AZ), Washington (WA), Oregon (OR), and California (CA). North includes NOAA regions Northeast, Ohio Valley, Upper Midwest, Northern Rockies and Plains, and Northwest: VT, NH, NY, WI, IL, MN, IA, MO, NE, KS, CO, ID, WA, and OR. South includes NOAA regions Southeast, South, Southwest, and West: NC, AZ, TX, NV and CA (Fig. 5a).

Software

All analyses were performed using the XLSTAT Add-in for Microsoft Excel, Version 16.54. Figures were generated with BioVinci 3.0.9, Bioturing Data Visualization Software, 2020.

Results

Sexual dimorphism

ANOVA [location (sex)]

US: ANOVA results for United States with SEX as qualitative variable showed no R2 value exceeded 0.08. Sex explained 8% of variance in total beak length and wing length: beak length (R2 = 0.08, FSEX = 63.27, p value = < 0.0001), wing length (R2 = 0.08, FSEX = 63.02, p value = < 0.0001). Sex explained 6% of the variance in distal beak length (R2 = 0.06, FSEX = 43.23, p value = < 0.0001), 1% of the variance in proximal beak length (R2 = 0.01, FSEX = 8.97, p value = 0.003), and was not significant for tarsus length (R2 = 0.001, FSEX = 0.99, p value = 0.321).

NATIVE RANGE: ANOVA results for the native range with SEX as qualitative variable showed no R2 value exceeded 0.07. Sex explained 7% of the variance in wing length (R2 = 0.07, FSEX = 16.25, p value = < 0.0001), 6% of variance in beak length (R2 = 0.06, FSEX = 15.16, p value = 0.0001), 4% of variance in proximal beak length (R2 = 0.04, FSEX = 10.77, p value = 0.001), 2% of distal beak length (R2 = 0.02, FSEX = 4.02, p value = 0.05), and was not significant for tarsus length (R2 = 0.02, FSEX = 4.30, p value = 0.04).

NZ: ANOVA results for New Zealand with SEX as qualitative variable showed only one significant result where sex explained 7% of variance in wing length (R2 = 0.07, FSEX = 4.94, p value = 0.03). All other traits for New Zealand SEX were non-significant: beak length (R2 = 0.01, FSEX = 0.53, p value = 0.47), proximal beak length (R2 = 0.02, FSEX = 1.00, p value = 0.32), distal beak length (R2 = 0.03, FSEX = 1.74, p value = 0.19), tarsus length (R2 = 0.05, FSEX = 3.06, p value = 0.09). ANOVA summary data in Table 3, LS means in Table 4.

Table 3.

Results from ANOVA with data separated by location (U.S., native, NZ) and sex within each location, and ANOVA results for U.S. regions only (north–south, east-central-west).

| ANOVA | Beak length | Tarsus length | Distal Beak length | Proximal beak length | Wing length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL LOCATIONS | |||||

| US (F + M) | |||||

| R2 | 0.08 | 0.001 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.08 |

| F | 63.27 | 0.99 | 43.23 | 8.97 | 63.02 |

| Pr > F | < 0.001 | 0.321 | < 0.001 | 0.003 | < 0.001 |

| NATIVE (F + M) | |||||

| R2 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| F | 15.16 | 4.30 | 4.02 | 10.77 | 16.25 |

| Pr > F | 0.0001 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.001 | < 0.0001 |

| NZ (F + M) | |||||

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| F | 0.53 | 3.06 | 1.74 | 1.00 | 4.94 |

| Pr > F | 0.47 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.32 | 0.03 |

| US REGIONS ONLY | |||||

| NORTH–SOUTH | |||||

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| F | 3.71 | 9.46 | 1.35 | 2.27 | 14.26 |

| Pr > F | 0.06 | < 0.001 | 0.25 | 0.13 | < 0.001 |

| EAST–CENTRAL–WEST | |||||

| R2 | 0.004 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.002 | 0.01 |

| F | 0.56 | 5.77 | 1.47 | 0.33 | 1.61 |

| Pr > F | 0.57 | < 0.001 | 0.23 | 0.72 | 0.20 |

Significant values in bold, non-significant values in italics.

Change over time

Fixed effect regression model

Results from fixed effect regressions which controlled for body size and included sex as an interaction term (measurement) ~ (PC1) + (time)*(location)*(sex) showed the following trends (Table 5):

Table 5.

Results from fixed effect regressions using all starling measurements, PC1 as a fixed effect to control for body size, and time*sex*location as interaction terms.

| All Data − fixed effect regressions − (measurement) ~ (PC1) + (TIME)*(LOCATION)*(SEX) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Increase/Decrease over time | Value | Standard error | DF | t | Pr >|t| | Lower bound (95%) | Upper bound (95%) |

| BEAK LENGTH | ||||||||

| Intercept | 24.65 | 0.16 | 1190.70 | 156.94 | < 0.0001 | 24.34 | 24.95 | |

| PC1 | 0.48 | 0.06 | 1193.00 | 7.57 | < 0.0001 | 0.35 | 0.60 | |

| Native females | Not significant | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | − 1.92 | 0.055 | − 0.01 | 0.00 |

| NZ females | Increase | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 4.87 | < 0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| US females | Increase | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 7.58 | < 0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Native males | Not significant | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 1.41 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| NZ Males | Increase | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 5.50 | < 0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| US males | Increase | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 13.40 | < 0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| TARSUS LENGTH | ||||||||

| Intercept | 28.93 | 0.12 | 1191.20 | 233.67 | < 0.0001 | 28.68 | 29.17 | |

| PC1 | 0.96 | 0.05 | 1193.00 | 19.30 | < 0.0001 | 0.86 | 1.05 | |

| Native females | Increase | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 2.16 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| NZ females | Increase | 0.03 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 10.13 | < 0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| US females | Decrease | − 0.01 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | − 7.45 | < 0.0001 | − 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Native males | Increase | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 4.39 | < 0.0001 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| NZ males | Increase | 0.03 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 11.84 | < 0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| US males | Decrease | − 0.01 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | − 9.39 | < 0.0001 | − 0.01 | − 0.01 |

| DISTAL BEAK LENGTH | ||||||||

| Intercept | 17.24 | 0.09 | 1190.60 | 190.90 | < 0.0001 | 17.07 | 17.42 | |

| PC1 | 1.44 | 0.04 | 1193.00 | 39.93 | < 0.0001 | 1.37 | 1.52 | |

| Native females | Decrease | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | − 3.04 | 0.002 | − 0.01 | 0.00 |

| NZ females | Increase | 0.04 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 21.94 | < 0.0001 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| US females | Increase | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 7.35 | < 0.0001 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Native males | Decrease | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | − 3.44 | 0.001 | − 0.01 | 0.00 |

| NZ males | Increase | 0.04 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 23.50 | < 0.0001 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| US males | Increase | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 10.83 | < 0.0001 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| PROXIMAL BEAK LENGTH | ||||||||

| Intercept | 7.40 | 0.10 | 1190.90 | 73.28 | < 0.0001 | 7.20 | 7.59 | |

| PC1 | − 0.96 | 0.04 | 1193.00 | − 23.81 | < 0.0001 | − 1.04 | − 0.88 | |

| Native females | Not significant | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | − 0.24 | 0.81 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| NZ females | Decrease | − 0.03 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | − 14.47 | < 0.0001 | − 0.03 | − 0.03 |

| US females | Increase | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 5.28 | < 0.0001 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Native males | Increase | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 5.30 | < 0.0001 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| NZ males | Decrease | − 0.03 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | − 14.31 | < 0.0001 | − 0.03 | − 0.02 |

| US males | Increase | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 11.21 | < 0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| WING LENGTH | ||||||||

| Intercept | 122.70 | 0.29 | 1188.30 | 417.24 | < 0.0001 | 122.12 | 123.27 | |

| PC1 | 2.68 | 0.12 | 1193.00 | 22.76 | < 0.0001 | 2.45 | 2.91 | |

| Native females | Not significant | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 0.38 | 0.70 | − 0.01 | 0.01 |

| NZ females | Increase | 0.09 | 0.01 | 1193.00 | 14.67 | < 0.0001 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| US females | Not significant | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | − 1.16 | 0.25 | − 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Native males | Increase | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 4.91 | < 0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| NZ males | Increase | 0.09 | 0.01 | 1193.00 | 17.18 | < 0.0001 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| US males | Increase | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1193.00 | 2.28 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

US: whole beak length (Females, Males), distal beak length (F, M) and proximal beak length (F, M) increased over time. Tarsus length (F, M) decreased over time, and change in wing length over time increased in males but was not statistically significant in females.

NATIVE RANGE: whole beak length was not statistically significant in females or males, and therefore not characterized by change over time. Tarsus length increased over time (F, M). Distal beak length in the native range decreased over time (F, M). Proximal beak length, and wing length increased in males, but was not statistically significant in females.

NZ: whole beak length (F, M), tarsus length (F, M), distal beak length (F, M), and wing length increased over time (F, M). Proximal beak (F, M) was the only trait that decreased over time in this population.

Linear regressions

Results from linear regressions in the native range show no change in whole beak length over time from all localities over a 206 year-period from 1816 to 2022 (N = 392), (p value = 0.426, R2 = 0.001) (Fig. 2a), or from a restricted dataset including only England and Germany, from the same time-period (p value = 0.620, R2 = 0.0007). We do find a statistically significant change over time in the native range in proximal beak length—shorter over time (p value = < 0.0001, R2 = 0.042); distal beak length—longer over time (p value < 0.0001, R2 = 0.056); tarsus length (a proxy for body size)—shorter over time (p value < 0.0001, R2 = 0.107); and wing length—longer over time (p value < 0.0001, R2 = 0.0846), (Fig. 2c).

In North American starlings, we find statistically significant changes in all measurements from 1890 to 2020. The change in whole beak length shows the beak getting longer over time (p value < 0.0001, R2 = 0.076) (Fig. 2a). We also find a statistically significant change in proximal beak length—longer over time (p value < 0.0001, R2 = 0.2994); while distal beak length is shorter with time (p value < 0.0003, R2 = 0.0172); tarsus length (a proxy for body size)—shorter over time (p value < 0.0001, R2 = 0.196); and wing length—shorter over time (p value < 0.0001, R2 = 0.0206), (Fig. 2c).

In starlings in New Zealand 1927–2017 (N = 68) we find no statistically significant changes over time in any measurement: beak, tarsus, or wing (Fig. 3a–c).

Comparisons between native range and invasive U.S. population

20 years after introduction to North America

When we compare the native range to North America between 1890 and 1910 we do not find statistically significant differences between means for the whole beak or proximal beak (Table 3, Fig. 4a). Tarsus length (T-test: p value < 0.00001) and wing lengths (T-test: p value = 0.036) differ between populations, with both measurements smaller in the North American population (Tarsus: NA = 28.53 mm, native = 30.12 mm; Wing: NA = 123.96, native = 125.89 mm), (Table 2, Fig. 4b). Means in Table 2 are based on raw data for museum specimens, compared with fresh specimens which are corrected for comparison with museum specimens.

Beak length averages in the starling population from New Zealand were equivalent to the native range (Beak: NZ = 24.77 mm, native = 24.84 mm, NA = 26.42 mm), but tarsus and wing lengths were closer to that in North America (Tarsus: NZ = 28.50 mm; Wing: NZ = 123.82), (Table 2, Fig. 3d-f).

Modern starlings from native range compared with modern starlings in the U.S.

From a random subsample of modern U.S. birds, the average beak length in U.S. was 27.03 mm, this was compared with the average beak length from 137 live-caught birds from a non-agricultural facility in Wales, UK (24.73 mm). The difference in means is 8%.

Comparison of modern starlings across the United States (East, Central, West; North, South)

Results from ANOVA analyses for eastern, central and western regions of the United States showed no statistically significant differences in group means except for tarsus length values (p value = 0.004), with differences between east–west and central-west, where birds from the west have shorter average tarsus lengths. Analyses comparing north and south showed statistically significant differences between tarsus (p value = 0.002) and wing measurements only (p value = < 0.00001), where tarsus and wings are shorter in the South versus the North (Table 3, U.S. regions only).

Discussion

Body size

North American starlings have shorter tarsi than those in the native range (North America = 27.85 mm, native range = 29.42 mm). Tarsus length can serve as proxy for bird body size44. Smaller birds in NA, versus larger birds in the parent population, occurred rapidly on arrival and this trend has persisted in the modern NA starling population today (Figs. 2c,d, 4b). Differences in sex did not explain the variance in tarsus length in NA or NZ and explained only 2% of the variance in this trait for the native range (Table 3). Average tarsus length in New Zealand is 28.5 mm and has increased over time in both sexes. However, only 68 specimens from this population were included, so this trend is preliminary.

Reduction in body size has been observed across 52 North American migratory avian taxa and is interpreted as a consequence of global warming45. Results here from fixed effect regressions demonstrate that tarsus length in the North American range has decreased over time in both sexes (Table 5). This reduction in body size in NA is evident upon introduction in 1890, which is prior to the 40-year period in Weeks et al. (1978–2016), (see Fig. 6c,d, dotted line). This suggests that global warming is not the primary explanation for this continent-specific trend in North America. Instead, smaller body size in North America could have been selectively advantageous due to warmer average summer temperatures than those in the native range, a pressure which starlings would have experienced during the few first months after introduction.

Figure 6.

(a) Ratio of whole beak length (mm) over tarsus length (mm), to correct for body size, plotted over each decade, native range 1816–2022 (blue), shaded blue area indicates time-period prior to 1890 introduction to the U.S. (b) Ratio of beak length/tarsus length in introduced U.S. range (orange) 1890–2020, pink dotted line across indicates mean for U.S. in 1960’s. (c) Tarsus length (mm) plotted over each decade, native range 1816–2022 (blue). (d) Tarsus length (mm) in introduced U.S. range (orange) 1890–2020, pink dotted line across indicates mean for U.S. in 1890’s.

For the spatial comparison across the United States (2017 only), we find that mean tarsus length decreases further west (averages: East = 26.95 mm, Central = 26.94 mm, West = 26.53 mm), and further south (North = 26.90 mm, South = 26.46 mm), (Table 2; Fig. 5b,c). These subtle trends across the U.S., where tarsus length is smaller in regions further west and south are also supported by ANOVA results which detect a statistically significant difference in this trait between north–south, and east-central-west (Table 3). Differences in temperature, seasonality and/or aridity across the country may play a role in shaping these patterns. Our results here are different to a previous analysis of North American starlings which did not find a relationship between tarsus length variation and any climatic variables30. Lack of congruence between this study and ours may be due to differences in sample size, where the previous study included only 168 birds. Therefore, additional analyses with fine-scaled spatiotemporal climatic variables could further clarify the specific drivers of these intriguing patterns.

Taken together, the rapid onset of the change in body size in North America upon arrival, coupled with the results from the spatial analysis, support that smaller body size in North American starlings may be partly due to selection or developmental plasticity in response to warmer summer temperatures than the native range. Though genetic drift upon arrival and/or the founder population of birds randomly consisting of smaller bodied birds cannot be ruled out here.

Wing length

Consistent with differences in body size, wing length is longer in the native range than in the NA range, and longer in males than females. Fixed effect regressions which control for body size and account for sex show that wing length increased over time in males, but not in females in both the native and North American ranges. This result is consistent with previous studies which have shown that males tend to differentiate more so than females in introduced bird populations31. An increase in wing length has also been observed across several North American migratory avian taxa as a compensatory adaptation to maintain migration efficiency when body size declines45.

Bitton and Graham found that starlings over a 120-year period in NA showed an increased roundedness of the wing caused by an increase in the length of secondary feathers4. They suggest that the wing shape change in NA starlings may have been adaptive, conferring more efficient foraging and predator avoidance.

We also find that wing length is slightly longer in starlings in the Northern U.S. versus those in the South (North = 123.10 mm, South = 121.62 mm), these trends are also supported by ANOVA results (Table 3). This result is also consistent with differences in body size between these two regions, where birds are also slightly smaller in the South than the North.

Beak length

One of the more robust trends in our data is that whole beak length has increased over time in the invasive North American starling population (in both sexes) with no change over time in the native range. This trend is supported by the results from linear regressions (Fig. 2a,c), and fixed effect regressions which controlled for body size and considered sexes separately (Table 5). ANOVA results show that sex explains 8% of whole beak length variation in the U.S., and 6% in the native range, but this was not a main driver in the overall trends over time. In New Zealand, the average beak length (24.77 mm) was closer to the native range (24.84 mm) than to NA (26.42 mm). Proximal beak length increased over time in the North American range (in both sexes), and in native range males only. Relatedly, sex explained only 1% of proximal beak length in the U.S., and 4% in the native range. Distal beak length increased over time in North America (in both sexes), but decreased over time in the native range (in both sexes), though variation due to differences in beak wear may complicate interpretations of this trend. These changes are evident from a 128-year period in NA, compared with a 206-year period in the native range.

Changes in beak morphology over short time scales have served as a classic example of evolutionary change within bird populations, and between species, for decades46–48. These morphological adaptations have been primarily attributed to shifts in food availability, although thermoregulation may also play an important role49–51. Additionally, the distal portion of the beak can be subject to different degrees of seasonal wear depending on the environmental substrates with which they regularly interact52. Below, we discuss thermoregulation, beak wear, and dietary adaptation as potential mechanisms for the patterns we observe in our beak measurement data.

Beak thermoregulation

Longer appendages are adaptive as a cooling mechanism in warmer environments (i.e., Allen’s Rule) which has been documented in wild bird populations and tested in controlled experiments53–55. Beak development responds to temperature, initiating a plastic response that generates longer beaks in warmer temperatures. Longer beaks then have increased surface area to allow for more efficient cooling in warmer climates56,57. A recent review summarizes the evidence that thermoregulation due to climate warming may be driving increased beak length across several avian taxa51. Following this trend, beak surface area in introduced Australian starlings is larger in those populations living in hotter and wetter climates58.

If global warming were driving the beak length changes we observe in starlings, this trend should be evident across all global populations. Instead, we observe beak length stasis in the native range over 206 years and elongation in North America. This indicates that global warming may not be the primary factor that explains the change observed in NA. Especially since the northern regions of the native range have experienced more extreme changes in average annual temperature over time than equivalent changes in North America59. The timing of the observed change in beak length in the U.S. also does not coincide with the most consistent climbing trend in average yearly global temperatures, which began approximately in 198060,61. Instead, we observe an initial overlap in beak length in native and NA starlings after their arrival in North America (1890), but by 1960, lengths in NA are above those found in any specimen from the native range (Figs. 2a, 6a,b).

An alternate climate-driven explanation could be that changes in beak length were impacted due to North American starlings entering a novel climate with more dramatic seasonal temperature fluctuations and higher maximum temperatures than their native range. A recent study of starling beak morphology and genetics in Australia found that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) correlated with beak surface area were most strongly associated with patterns of daily temperature variation across their range29.

We address the possibility of temperature variation as a driver of starling beak morphology in NA by partitioning our modern dataset across the United States within the well-sampled one-year winter period in 2017. We do not find any geographic differences in average beak length across the United States in either east–west or north–south directions (Tables 2 and 3). This suggests that North American starling beak length changes may not be solely the result of thermoregulation due to different regional climates.

Although we found no evidence for differences in beak length across the United States, four individuals from Arizona (collected in 2017 from feedlots) had exceptionally long beaks ranging from 36.83 to 41.34 mm (Image S1). These outliers were removed from all analyses. To determine if this trait was stable in the population from this region, 22 additional individuals were collected from Arizona in January 2020 (from a landfill). None of the additional birds from Arizona showed unusually long beaks, with an average beak length of 25.20 mm (Table 2). See supplementary materials for further discussion of this trend.

Beak wear

Are starling beaks longer in North America than in their native range because they are experiencing less wear due to differences in environmental substrates or foraging behaviors?

The rhamphotheca, or keratinized outer layer of the beak, grows continuously throughout a bird’s lifetime—and can experience different degrees of wear from seasonal variation in foraging strategies and frequency of behaviors such as bill wiping and preening52,62–64. Bill wiping, a mechanism by which birds wear down their beaks by repeatedly drawing them over a surface, has been shown to decrease in starlings feeding on drier foods as compared to foods with a stickier consistency, such as fruit65,66. Additionally, in fall and winter, starling beaks are darker colored due to the increased presence of melanin granules which results in a mechanistically harder beak that wears down at a slower rate than their yellow beaks in spring and summer67.

Starling’s feeding strategy during warmer months is frequent open bill probing, where they insert their beak into soil, engage the masseter muscle, and rapidly grasp for invertebrates68. In the absence of open bill probing, where starlings eat above-ground dry foods from farms primarily in the winter months, beaks may not experience the same degree of abrasion. This seasonal change in foraging behavior, together with harder melanic beaks and a potential decrease in bill-wiping behavior from feeding on drier foods, could collectively contribute to an increased overall beak length in starlings in winter months. The longest beaks we observed in our data were found in the modern USDA dataset, where birds were collected from dairies and feedlots in the winter months, January–March 2016, 2017 (average = 27.33 mm) (Table 2). This suggests a plastic seasonal response to fluctuations in environmental substrate and food availability and not necessarily a developmental or genetic change.

However, our measure of the proximal beak length, from the base of the cranium to the nares, serves as a means of addressing the question of whether seasonal beak wear at the distal end of the beak is driving the differences in beak length we observe. The proximal region of the beak, or frontonasal region, cannot be subject to different degrees of wear throughout the lifetime of the individual; therefore, we use this measurement as a closer approximation of changes at the developmental and genetic levels69. We find that the mean proximal beak is 1.166 mm longer (95% CI [1.170,1.163]) in starlings from North America compared with those from the native range and shows a marked increase in length over time (Tables 2 and 5). This supports a potential role for heritable change in beak length over time in North American starlings.

Dietary adaptation

Beak morphology is known to be partly heritable, and several genes associated with modifications in beak length (COL4A5, BMP4, CaM), beak size (HMGA2), and overall shape (ALX1) show evidence of selection in different avian taxa70–73. In light of these elegant studies—which link beak phenotype with genotype—we can better understand how beak morphology evolves in response to natural selection even in the absence of genetic data. Focusing on proximal beak changes in NA starlings, we observe a robust signal where this portion of the beak is getting longer over time. This cannot be explained by lack of beak wear, as stated prior.

Therefore, after considering multiple possible pressures on beak length, we propose that the trend of beak lengthening in North American starlings suggests that dietary adaptation may be contributing to this change. The most dramatic difference between starling diet in the U.S. and their native range is the intensity of their foraging at dairies and feedlots in the U.S., where they consume substantial amounts of food intended for livestock1. In this context, grain-based feed consisting of various combinations of grain (e.g., corn, wheat, sorghum), silage, hay, and high energy fat nuggets is distributed in feed troughs or bunks. Since 1960, corn production in the U.S. has increased exponentially, which has also enabled a concurrent expansion of the cattle industry74. By the 1960’s feedlot operators in several states were reporting major starling disturbance75–78. In our data, 1960 is when we observe a marked increase in proximal starling beak length in the U.S. beyond what is observed in the native range at any time.

Today, the majority of cattle in the U.S. are fed outdoors in winter months, compared with Europe, where cattle primarily graze on grass outdoors in warmer months and in winter are often provisioned indoors (8–10 months in Northern Europe)79,80. Starlings in Britain do consume grain feed for livestock, however, the geographic range of this dietary behavior is not equivalent in scale to that in the U.S.—and does not uniformly occur across the entirety of their native range, such as in North Africa or Pakistan81–84. In New Zealand, substantially fewer cows are supplemented with corn than in the U.S., and starling damage on farms is concentrated on fruit crops85,86.

Starling flocks on U.S. dairies can exceed 10,000 birds and cause an estimated $800 million dollars of annual lost revenue across the country12,87. It has been estimated that starlings spend 90 days at livestock facilities in winter, obtain half (0.5) of their winter diet from these facilities, and each bird consumes 0.0625 lbs (0.283 kg) of feed per day88. Using the lower bound of current starling population size estimates in the U.S. (85.9 million)3, and assuming 0.75% of that population feed at livestock facilities (64.4 million), we estimate that starlings may consume 136,125,000 lbs (61,745 metric tons) of livestock feed per year in the United States. An individual bird can eat up to 2.2 lbs (1 kg) of feed per month, and 1000 birds can consume 630 lbs (286 kg) every hour spent foraging at feedlots89,90. Starling feeding experiments show that starlings avoid fibrous food sources such as hay and straw while selecting the more nutritional components of corn and other grains13. In these experimental studies, birds preferentially selected steam-flaked corn, a small (5.7 mm) lightweight flat flake, high in starch and distributed to livestock scattered throughout bundles of alfalfa hay87. Notably, beak length can be a limiting factor in their access to this vertically distributed food source, as certain feeding tray depths were too deep for their access to grains in these experiments (S. Deliberto, personal communication, 2018). When probing for grass grubs, starling beaks reach less than 2 cm depth into soil, and it has been suggested that longer beaks may also improve their access to invertebrates58,91.

A study of the morphology, genetics, and behavior of great tits showed that populations that are provisioned from bird feeders in the UK have evolved longer beaks than continental European populations which are not exposed to bird feeders70. Here, we infer that large-scale dairies and feedlots across the United States may have driven starlings to evolve longer beaks to more efficiently forage in this highly modified, energy-rich agricultural landscape. A confounding variable is that starlings regularly utilizing feedlots may also experience less beak wear than those probing for invertebrates in the ground, so careful analyses of seasonal phenotypic changes in all aspects of beak morphology require further examination. The data we report here provide a powerful and unique opportunity to better understand an invasive species’ response to a historically recent, continent-wide anthropomorphic pressure and further illuminate the evolutionary and ecological dynamics between diet, phenotype, plasticity, and adaptation in birds.

Conclusions

Results presented here show morphological differences between invasive North American starlings and those from their native range, with additional directional change in the North American population through time. In invasive starlings in North America, beak length has increased over 130 years, and tarsus length has decreased. In our sample of modern starlings only, beak length differences are not spatially structured across the United States, consistent with expectations for a heritable trait under stabilizing selection in a panmictic population. This suite of morphological traits in the invasive North American range now contrasts with the starling population in the native range, where beak length has stayed constant during the past 206-years and tarsus length has increased slightly.

European starlings present a rich opportunity to better understand how evolutionary forces such as founder effect, selection, and phenotypic plasticity may have enabled repeated invasions on multiple continents. Humans and invasive European starlings have a deeply entangled ecological history, with several deliberate introductions on multiple continents followed by starlings’ swift and continued exploitation of human modified environments such as urban centers and agroecosystems. Disentangling the precise contributions of evolutionary, ecological, and environmental variables which have shaped these changes present intriguing directions for additional studies.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Lee Ann Rollins, UNSW, and Christopher Raxworthy, AMNH for providing feedback on an earlier draft of this manuscript. We also thank the following people for providing access to museum specimens: Brian Smith, AMNH; Paul Sweet, AMNH; Peter Capainolo, AMNH; Alex Bond, NHM, Tring; Hein Van Grouw, NHM, Tring; Colin Miskelly, Te Papa Museum. Hailey Ellis, Corin Klonowski, Carrie Olson, Cole Suckow and Brian Allen performed initial measurements on USDA-APHIS and DMNS specimens. Jensine Raihan and Kaira Mediratta, AMNH SRMP collected preliminary data for this project. We thank Justin Fischer for creating map of USDA fresh specimen collection locations (Fig. 5a), and Shahrina Chowdhury for guidance regarding statistical methods. We also thank USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services staff in the following states for 2016 and 2017 sample collections: Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Author contributions

J.Z. conceived of the research; J.Z., S.W., S.D., A.P. conducted background research; J.Z., S.W., S.D. analyzed data and wrote the paper; J.Z., S.W., S.D., A.P., P.H. collected measurement data from specimens.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-49623-y.

References

- 1.Feare CJ. The Starling. Oxford University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cabe PR. European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris), version 1.0. In: Billerman SM, editor. Birds of the World. Cornell Lab of Ornithology; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg KV, Dokter AM, Blancher PJ, Sauer JR, Smith AC, Smith PA, Stanton JC, Panjabi A, Helft L, Parr M, Marra PP. Decline of the North American avifauna. Science. 2019;366(6461):120–124. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bitton PP, Graham BA. Change in wing morphology of the European starling during and after colonization of North America. J. Zool. 2015;295(4):254–260. doi: 10.1111/jzo.12200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leck CF. Avian Introductions Naturalized Birds of the World. Christopher Lever; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navas JR. Introduced and naturalized exotic birds in Argentina. Rev. Mus. Arg. Cienc. Nat. 2002;4:191–202. doi: 10.22179/REVMACN.4.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stuart KC, Hofmeister NR, Zichello JM, Rollins LA. Global invasion history and native decline of the common starling: insights through genetics. Biol. Invasions. 2023;25(5):1291–1316. doi: 10.1007/s10530-022-02982-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callaghan CT, Nakagawa S, Cornwell WK. Global abundance estimates for 9700 bird species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118(21):e2023170118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2023170118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabe PR. European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) as vectors and reservoirs of pathogens affecting humans and domestic livestock. Animals. 2021;11(2):466. doi: 10.3390/ani11020466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandler JC, Anders JE, Blouin NA, Carlson JC, LeJeune JT, Goodridge LD, Wang B, Day LA, Mangan AM, Reid DA, Coleman SM. The role of European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) in the dissemination of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli among concentrated animal feeding operations. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64544-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linz, G. M., Homan, H. J., Gaulker, S. M., Penry, L. B. & Bleier, W. J. European Starlings: A Review of an Invasive Species with Far-Reaching Impacts (2007).

- 12.Pimentel D, Zuniga R, Morrison D. Update on the environmental and economic costs associated with alien-invasive species in the United States. Ecol. Econ. 2005;52(3):273–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlson JC, Stahl RS, DeLiberto ST, Wagner JJ, Engle TE, Engeman RM, Olson CS, Ellis JW, Werner SJ. Nutritional depletion of total mixed rations by European starlings: Projected effects on dairy cow performance and potential intervention strategies to mitigate damage. J. Dairy Sci. 2018;101(2):1777–1784. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-12858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark, L. & McLean, R. G. A Review of Pathogens of Agricultural and Human Health Interest Found in Blackbirds (2003).

- 15.Barras, S. C., Wright, S. E. & Seamans, T. E. Blackbird and starling strikes to civil aircraft in the United States, 1990–2001 200 (USDA National Wildlife Research Center-Staff Publications, 2003)

- 16.Koenig WD. European Starlings and their effect on native cavity-nesting birds. Conserv. Biol. 2003;17(4):1134–1140. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.02262.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bodt LH, Rollins LA, Zichello JM. Contrasting mitochondrial diversity of European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) across three invasive continental distributions. Ecol. Evol. 2020;10(18):10186–10195. doi: 10.1002/ece3.6679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rollins LA, Woolnough AP, Sinclair R, Mooney NJ, Sherwin WB. Mitochondrial DNA offers unique insights into invasion history of the common starling. Mol. Ecol. 2011;20(11):2307–2317. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berthouly-Salazar C, Hui C, Blackburn TM, Gaboriaud C, Van Rensburg BJ, Van Vuuren BJ, Le Roux JJ. Long-distance dispersal maximizes evolutionary potential during rapid geographic range expansion. Mol. Ecol. 2013;22(23):5793–5804. doi: 10.1111/mec.12538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hofmeister NR, Werner SJ, Lovette IJ. Environmental correlates of genetic variation in the invasive European starling in North America. Mol. Ecol. 2021;30(5):1251–1263. doi: 10.1111/mec.15806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cabe PR. The effects of founding bottlenecks on genetic variation in the European starling (Sturnus vulgaris) in North America. Heredity. 1998;80(4):519–525. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2540.1998.00296.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brewer D. Wrens, Dippers and Thrashers. Bloomsbury Publishing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stuart KC, Cardilini AP, Cassey P, Richardson MF, Sherwin WB, Rollins LA, Sherman CD. Signatures of selection in a recent invasion reveal adaptive divergence in a highly vagile invasive species. Mol. Ecol. 2021;30(6):1419–1434. doi: 10.1111/mec.15601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Estoup A, Guillemaud T. Reconstructing routes of invasion using genetic data: Why, how and so what? Mol. Ecol. 2010;19(19):4113–4130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wares, J. P. Mechanisms that drive evolutionary change. Insights from species introduction and invasions. Species Invasions: Insights into Ecology, Evolution, and Biogeography 229–257 (2005)

- 26.Uller T, Leimu R. Founder events predict changes in genetic diversity during human-mediated range expansions. Glob. Change Biol. 2011;17(11):3478–3485. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02509.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rollins LA, Moles AT, Lam S, Buitenwerf R, Buswell JM, Brandenburger CR, Flores-Moreno H, Nielsen KB, Couchman E, Brown GS, Thomson FJ. High genetic diversity is not essential for successful introduction. Ecol. Evol. 2013;3(13):4501–4517. doi: 10.1002/ece3.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dlugosch KM, Anderson SR, Braasch J, Cang FA, Gillette HD. The devil is in the details: Genetic variation in introduced populations and its contributions to invasion. Mol. Ecol. 2015;24(9):2095–2111. doi: 10.1111/mec.13183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stuart KC, Sherwin WB, Cardilini AP, Rollins LA. Genetics and plasticity are responsible for ecogeographical patterns in a recent invasion. Front. Genet. 2022;13:824424. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.824424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blem CR. Geographic variation in mid-winter body composition of starlings. The Condor. 1981;83(4):370–376. doi: 10.2307/1367508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross HA, Baker AJ. Variation in the size and shape of introduced starlings, Sturnus vulgaris (Aves: Sturninae), New Zealand. Can. J. Zool. 1982;60(12):3316–3325. doi: 10.1139/z82-420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andrew SC, Awasthy M, Griffith AD, Nakagawa S, Griffith SC. Clinal variation in avian body size is better explained by summer maximum temperatures during development than by cold winter temperatures. The Auk. 2018;135(2):206–217. doi: 10.1642/AUK-17-129.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weeks BC, Klemz M, Wada H, Darling R, Dias T, O'Brien BK, Probst CM, Zhang M, Zimova M. Temperature, size and developmental plasticity in birds. Biol. Lett. 2022;18(12):20220357. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2022.0357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baldwin SP, Oberholser HC, Worley LG. Measurements of birds. Sci. Publ. Clevel. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1931;2:1–165. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borras A, Pascual J, Senar JC. What do different bill measures measure and what is the best method to use in granivorous birds? J. Field Ornithol. 2000;71:606–611. doi: 10.1648/0273-8570-71.4.606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Werner SJ, Fischer JW, Hobson KA. Multi-isotopic (δ 2H, δ 13C, δ 15N) tracing of molt origin for European starlings associated with US dairies and feedlots. PLos ONE. 2020;15(8):e0237137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winker K. Suggestions for measuring external characters of birds. Ornitol. Neotrop. 1998;9:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blasco-Zumeta, J. & Heinze, G. Ibercaja Aula en Red. Ageing and sexing. http://aulaenred.ibercaja.es/wp-content/uploads/197_WoodcockSrusticola.pdf. (2006).

- 39.Bjordal H. Effects of deep freezing, freeze-drying and skinning on body dimensions of House Sparrows (Passer domesticus) Cinclus. 1983;6:105–108. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winker K. Specimen shrinkage in Tennessee warblers and “Traill's” flycatchers (Se encojen especímenes de Vermivora peregrina y Empidonax traillii) J. Field Ornithol. 1993;1993:331–336. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuczynski L, Tryjanowski P, Antczak M, Skoracki M, Hromada M. Repeatability of measurements and shrinkage after skinning: the case of the Great Grey Shrike (Lanius excubitor) Bonner Zool. Beiträge. 2002;51:127–130. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mathys BA, Lockwood JL. Contemporary morphological diversification of passerine birds introduced to the Hawaiian archipelago. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2011;278(1716):2392–2400. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bookstein FL. "Size and shape": A comment on semantics. Syst. Zool. 1989;38(2):173–180. doi: 10.2307/2992387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Senar JC, Pascual J. Keel and tarsus length may provide a good predictor of avian body size. Ardea. 1997;85:269–274. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weeks BC, Willard DE, Zimova M, Ellis AA, Witynski ML, Hennen M, Winger BM. Shared morphological consequences of global warming in North American migratory birds. Ecol. Lett. 2020;23(2):316–325. doi: 10.1111/ele.13434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boag PT, Grant PR. Intense natural selection in a population of Darwin's finches (Geospizinae) in the Galapagos. Science. 1981;214(4516):82–85. doi: 10.1126/science.214.4516.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bardwell E, Benkman CW, Gould WR. Adaptive geographic variation in western scrub-jays. Ecology. 2001;82(9):2617–2627. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[2617:AGVIWS]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olsen AM. Feeding ecology is the primary driver of beak shape diversification in waterfowl. Funct. Ecol. 2017;31(10):1985–1995. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12890. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tattersall GJ, Arnaout B, Symonds MR. The evolution of the avian bill as a thermoregulatory organ. Biol. Rev. 2017;92(3):1630–1656. doi: 10.1111/brv.12299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friedman NR, Miller ET, Ball JR, Kasuga H, Remeš V, Economo EP. Evolution of a multifunctional trait: Shared effects of foraging ecology and thermoregulation on beak morphology, with consequences for song evolution. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2019;286(1917):20192474. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2019.2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ryding S, Klaassen M, Tattersall GJ, Gardner JL, Symonds MR. Shape-shifting: Changing animal morphologies as a response to climatic warming. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2021;36(11):1036–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2021.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van de Pol M, Ens BJ, Oosterbeek K, Brouwer L, Verhulst S, Tinbergen JM, Rutten AL, De Jong M. Oystercatchers' bill shapes as a proxy for diet specialization: more differentiation than meets the eye. Ardea. 2009;97(3):335–347. doi: 10.5253/078.097.0309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.NeSmith, C. C. The Effect of the Physical Environment on the Development of Red-Winged Blackbird Nestlings: A Laboratory Experiment. Doctoral Dissertation (Florida State University, 1985).

- 54.James FC, NeSmith C. Nongenetic effects in geographic differences among nestling populations of Red-winged Blackbirds. Acta XIX Congressus Int. Orthinol. 1988;2:1424–1433. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Greenberg R, Cadena V, Danner RM, Tattersall G. Heat loss may explain bill size differences between birds occupying different habitats. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e40933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tattersall GJ, Chaves JA, Danner RM. Thermoregulatory windows in Darwin's finches. Funct. Ecol. 2018;32(2):358–368. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Romano A, Séchaud R, Roulin A. Geographical variation in bill size provides evidence for Allen’s rule in a cosmopolitan raptor. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2020;29(1):65–75. doi: 10.1111/geb.13007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cardilini A, Buchanan KL, Sherman CD, Cassey P, Symonds MR. Tests of ecogeographical relationships in a non-native species: What rules avian morphology? Oecologia. 2016;181(3):783–793. doi: 10.1007/s00442-016-3590-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McKinnon KA, Rhines A, Tingley MP, Huybers P. The changing shape of Northern Hemisphere summer temperature distributions. J. Geophys. Res. 2016;121(15):8849–8868. doi: 10.1002/2016JD025292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jones PD. Hemispheric surface air temperature variations: Recent trends and an update to 1987. J. Clim. 1988;1(6):654–660. doi: 10.1175/1520-0442(1988)001<0654:HSATVR>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Allen, M. et al. 2018. Global warming of 15°C An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty. (2018).

- 62.Stettenheim P. The integument of birds. Avian Biol. 1972;2:1–63. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Matthysen ERIK. Seasonal variation in bill morphology of nuthatches Sitta europaea: dietary adaptations or consequences. Ardea. 1989;77(1):117–125. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clayton DH, Moyer BR, Bush SE, Jones TG, Gardiner DW, Rhodes BB, Goller F. Adaptive significance of avian beak morphology for ectoparasite control. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2005;272(1565):811–817. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hardy JW. Epigamic and reproductive behavior of the Orange-fronted Parakeet. The Condor. 1963;65(3):169–199. doi: 10.2307/1365664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cuthill I, Witter M, Clarke L. The function of bill-wiping. Anim. Behav. 1992;43(1):103–115. doi: 10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80076-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bonser RH, Mark S, Witter Indentation hardness of the bill keratin of the European starling. Condor. 1993;95:736–738. doi: 10.2307/1369622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Beecher, W. J. Feeding Adaptations and Evolution in the Starlings (1978).

- 69.Wu P, Jiang TX, Shen JY, Widelitz RB, Chuong CM. Morphoregulation of avian beaks: Comparative mapping of growth zone activities and morphological evolution. Dev. Dyn. 2006;235(5):1400–1412. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bosse M, Spurgin LG, Laine VN, Cole EF, Firth JA, Gienapp P, Gosler AG, McMahon K, Poissant J, Verhagen I, Groenen MA. Recent natural selection causes adaptive evolution of an avian polygenic trait. Science. 2017;358(6361):365–368. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lamichhaney S, Berglund J, Almén MS, Maqbool K, Grabherr M, Martinez-Barrio A, Promerová M, Rubin CJ, Wang C, Zamani N, Grant BR. Evolution of Darwin’s finches and their beaks revealed by genome sequencing. Nature. 2015;518(7539):371–375. doi: 10.1038/nature14181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Abzhanov A, Kuo WP, Hartmann C, Grant BR, Grant PR, Tabin CJ. The calmodulin pathway and evolution of elongated beak morphology in Darwin's finches. Nature. 2006;442(7102):563–567. doi: 10.1038/nature04843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schneider RA. How to tweak a beak: molecular techniques for studying the evolution of size and shape in Darwin's finches and other birds. Bioessays. 2007;29(1):1–6. doi: 10.1002/bies.20517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wagner JJ, Archibeque SL, Feuz DM. The modern feedlot for finishing cattle. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2014;2(1):535–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-022513-114239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bailey EP. Abundance and activity of starlings in winter in northern Utah. The Condor. 1966;68(2):152–162. doi: 10.2307/1365713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.West RR. Reduction of a winter starling population by baiting its preroosting areas. J. Wildl. Manag. 1968;32:637–640. doi: 10.2307/3798951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Besser JF, Royall WC, Jr, Degrazio JW. Baiting starlings with DRC-1339 at a cattle feedlot. J. Wildl. Manag. 1967;31:48–51. doi: 10.2307/3798359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Palmer, T. K. Pest Bird Damage Control in Cattle Feedlots: The Integrated Systems Approach (1976).

- 79.van Arendonk JA, Liinamo AE. Dairy cattle production in Europe. Theriogenology. 2003;59(2):563–569. doi: 10.1016/S0093-691X(02)01240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smith HG, Bruun M. The effect of pasture on starling (Sturnus vulgaris) breeding success and population density in a heterogeneous agricultural landscape in southern Sweden. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2002;92(1):107–114. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8809(01)00266-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Feare CJ, Wadsworth JT. Starling damage on farms using the complete diet system of feeding dairy cows. Anim. Sci. 1981;32(2):179–183. doi: 10.1017/S0003356100024983. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Feare CJ, McGinnity N. The relative importance of invertebrates and barley in the diet of Starlings Sturnus vulgaris. Bird Study. 1986;33(3):164–167. doi: 10.1080/00063658609476915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Djennas-Merrar K, Berrai H, Marniche F, Doumandji S. Fall-winter diet of the starling (Sturnus vulgaris) between foraging areas and resting areas near Algiers. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2016;10(8):11–19. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mahmood T, Usman-ul-Hassan SMM, Nadeem MS, Kayani AR. Population and diet of migratory Common Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) wintering in agricultural areas of Sialkot district, Pakistan. Forktail. 2013;29:143–144. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nelson, P. C. Bird problems in New Zealand-methods of control. In Proceedings of the Vertebrate Pest Conference (Vol. 14, No. 14) (1990).

- 86.McCall DG, Clark DA. Optimized dairy grazing systems in the northeast United States and New Zealand. II. System analysis. J. Dairy Sci. 1999;82(8):1808–1816. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(99)75411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Depenbusch BE, Drouillard JS, Lee CD. Feed depredation by European starlings in a Kansas feedlot. Human-Wildl. Interact. 2011;5(1):58–65. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Johnson, R. J. & Timm, R. M. Wildlife Damage to Agriculture in Nebraska: A Preliminary Cost Assessment (1987).