Abstract

BACKGROUND

The study aimed to assess the differences in anxiety management types between German and Polish samples. The research was conducted in the context of health-related variables and anxiety management types during the period of March to April 2020. The research project was approved by the Ethical Committee at the Institute of Psychology at the University of Gdansk, Poland.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

German Sample: Consisted of 323 subjects with an average age of 46 years. 73% were females, and 26% were males. Polish Sample: Included 100 subjects with an average age of 42 years. 73% were females, and 27% were males. The study collected data on various health-related variables and anxiety management types using specific measurement procedures.

RESULTS

There were significant differences in the frequency distribution of anxiety management types between the Polish and German samples (p < .001). In the Polish sample, 60% showed negative anxiety management types (Sensitizer, Repressor, Highly anxious), compared to the German sample with 52%. 40% of the Polish and 48% of the German sample showed positive expressions. There were stronger significant differences in both samples regarding health-related variables, with the Polish sample being at a disadvantage.

CONCLUSIONS

The study provides a comprehensive insight into the anxiety management types between German and Polish samples, revealing distinct differences in their responses. The Polish sample exhibited a higher prevalence of negative anxiety management types compared to the German sample. These disparities can be attributed to a myriad of factors, including historical traumas, transgenerational experiences, and the influence of dominant religions in each country. The findings underscore the importance of considering cultural, historical, and religious contexts when assessing and addressing mental health and coping mechanisms across different populations. Further research with larger samples and diverse groups could offer a more nuanced understanding of these patterns and their underlying causes.

Keywords: COVID-19, anxiety, coping, psychological health, biocentric health theory

BACKGROUND

One of the most prevalent stress reactions during the COVID lockdown was fear and anxiety (Armitage & Nellums, 2020; Bidzan-Bluma et al., 2020; Dillard et al., 2022; Di Maggio et al., 2023; Roy et al., 2020). In the Pandemic Management Theory of Stueck (2021) the following most expressed fears during the first lockdown in Germany were found: fear of losing autonomy (70%), fear of getting sick (70%), fear of losing energy (66%), fear of the future (64%), fear of entering into a relationship with others (59%), fear of setting limits (56%) and fear of aggression by others (56%) (Stueck, 2021).

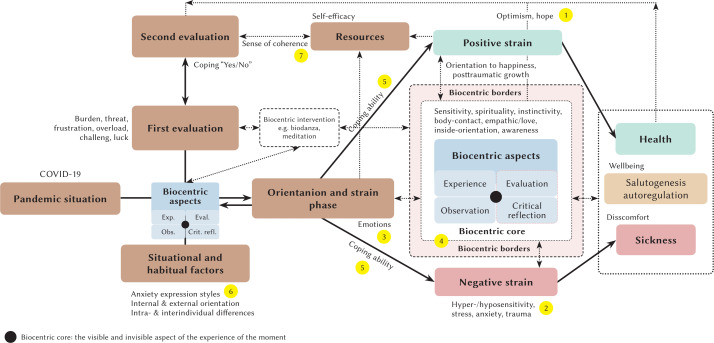

In this article we focus on the cognitive mechanisms related to the management of anxiety. Furthermore, we investigated the relationship of anxiety management types to selected health variables within the first COVID-19 lockdown period (March and April 2020) in Germany and Poland (Bidzan-Bluma et al., 2020). This study was embedded in the international project “Corona and Psyche”. It was based on the model of the biocentric health theory in pandemic situations, which is shown in Figure 1. The model describes the psychological processing of the stress situation during the lockdown and was published as “Pandemic Management Theory” by Stueck (2021). In the model, it can be seen that the pandemic situation (e.g., COVID-19) triggers a series of evaluation and regulation mechanisms in the psychological sense. The stress-strain (cf. Scott & Charteris, 2003) process begins with two appraisal phases (psychological evaluation of the situation). In the first appraisal phase, the situation is interpreted in terms of the degree of stress, e.g., in terms of threat, under/overload, but also in terms of positive interpretations (challenge, curiosity) (cf. Stueck, 2021). The second, parallel appraisal process assesses the situation in terms of its manageability and resources. This transactional appraisal cycle in the generation of stress was described by Lazarus and Launier (1978). Especially threat appraisal plays a major role in the generation of anxiety, as a specific stress response. Factors influencing these evaluation processes include, according to the biocentric health theory, the degree of external orientation of a person and the cognitive styles of the personality. These are personality-dependent cognitive, habitual perceptual peculiarities in the evaluation of situations. They include introversion and extraversion, but also the anxiety management types of personality studied in this article. For example, there are people who suppress certain pandemic situations or those who need a lot of information to cope with the fear that occurs (Sensitizers). The above-mentioned evaluation processes and the factors influencing them, such as anxiety management types, then trigger stress reactions. Depending on the ability to cope with the situation, either positive stress consequences arise, for example, when the situation is evaluated as a challenge, which leads to optimism (Schröder, 1992; Stueck, 2021), or negative strain consequences arise, for example stress and anxiety due to a threat evaluation (Rohmert & Rutenfranz, 1975; Schröder, 1992; Stueck, 2021). The difference between strain response and strain consequences is that the strain response occurs situationally and strain consequences represent a permanent manifestation of the situation. For example, the feeling of frustration occurs permanently and chronically. Through these mechanisms of action and coping resources, the state of the immune system and health and well-being can also be explained. In addition to these so-called anthropocentric impact factors, where the focus is on solving or coping with the stress problem, there are deeper biocentric impact factors that influence this stress-strain mechanism. Biocentric impact factors include, for example, confidence and relaxation. Stress reactions that counteract an unfolding of the biocentric effect factors are described as biocentric boundaries. These limits include, among others, the anxiety and tendency not to be honest (social desirability) studied in this article.

Figure 1.

Biocentric health theory in pandemics (simplified representation according to Stueck, 2021)

In the present article, the above-mentioned biocentric borders are primarily examined. These biocentric borders become visible, among other things, in the negative stress and strain contexts, in the anthropocentric effective circle of the model (Stueck et al., 2023). In contrast to biopoietic jumps, which imply growth, the anthropocentric effective circle is about coping with strain. This is a self-regulatory ability to adapt to changing conditions (“ability to switch off”). This ability begins in the appraisal of the pandemic situation. Anxiety management types have an effect on this appraisal, which are then also related to the cognitive, behavioral and emotional reactions or strain. The health variables analyzed in this study can be divided into the following subsections: emotional, behavioral, cognitive, coping-related health variables, and resource variables (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Variable plan

| Variables | Measurement method |

|---|---|

| Emotional health variables | |

| Optimism [1] | Self-Evaluation Scale “Are you optimistic about solving this crisis?” 1 (not at alt) - 10 (very optimistic) (Stueck, 2021) |

| Trauma (Peritraumatic Distress Inventory) [2] | Self-Evaluation Scale for 13 items. 1 (do not agree) - 5 (totally agree). Brunet’s (2001) Peritraumatic Stress Questionnaire serves as an indicator of experiencing a high degree of strain and chronic stress. The stress experienced is characterized by intense fear, helplessness or horror (Brunet et al., 2001). |

| Feeling of helplessness [3] | Single-Item Scale from the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory. 1 (do not agree) - 5 (totally agree) (Brunet et al., 2001) |

| Feeling of sadness and emotional pain [4] | Single-Item Scale from the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory. 1 (do not agree) - 5 (totally agree) (Brunet et al., 2001) |

| Fear of losing safety [4] | Single-Item Scale from the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory. 1 (do not agree) - 5 (totally agree) (Brunet et al., 2001) |

| Losing control of emotions [4] | Single-Item Scale from the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory. 1 (do not agree) - 5 (totally agree) (Brunet et al., 2001) |

| Feeling of frustration and anger [3] | Single-Item Scale from the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory. 1 (do not agree) - 5 (totally agree) (Brunet et al., 2001) |

| Coping variable Ability to “switch off” [5] | Single-Items-Scale to evaluate the ability to “switch off”. 1 (without problems) - 10 (huge problems) (Stueck, 2021) |

| Behavioral health variable | |

| Urge to move [6] | Self-evaluation Scale. 1 (low) - 6 (high) |

| Resource variable | |

| Sense of coherence [7] | Leipzig Sence of Coherence Scale |

| Cognitive health variable | |

| Sensitizer; Repressor; Non-defensive; Highly anxious [6] | R-S construct by Krohne (Byrne, 1961; Krohne, 1974; cit. in Grimm, 2013) |

| Shame for own emotional reactions [4] | Single-Item Scale from the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory. 1 (do not agree) - 5 (totally agree) (Brunet et al., 2001) |

| Feeling of guilt [4] | Single-Item Scale from the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory. 1 (do not agree) - 5 (totally agree) (Brunet et al., 2001) |

Note. [1-7] – indicator for position in the model (Figure 1).

The central aim of the present article is to examine the relationship between anxiety management types (see Table 1) and health variables (see Table 2) or psychological resources (sense of coherence). Another aim is to get an overview of the distributional differences of the anxiety management types between Germany and Poland.

Table 1.

Cognitive styles of dealing with threatening situations

| Defensive avoidance of unpleasant emotions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||

| Anxiety Trait Anxiety |

Low | Non-defensive, flexible, situation-adaptive mode | Repressor, consistent-avoiding mode |

| High tolerance for emotional arousal and uncertainty, situation-adapted processing of threatening information | Low tolerance for emotional arousal and high tolerance for uncertainty, no absorption of threatening information (low vigilance, cognitive avoider) | ||

| High | Sensitizer, monitoring mode | Highly anxious, inconsistent mode | |

| High tolerance for emotional arousal and low tolerance for uncertainty, high absorption of threatening information (high vigilance, cognitive sensitizer) | Either low tolerance for emotional arousal and/or for uncertainty, very inconsistent processing of threatening information, in consistent, unpredictable, and emotion-driven behavior | ||

Anxiety coping types are recorded according to the “repressor-sensitizer construct” (Byrne, 1961; Grimm, 2013; Krohne, 1986). This construct examines two variables, trait anxiety and social desirability, which when combined yield four cognitive styles of anxiety management (see Table 1).

To form these anxiety management types, a person’s anxiety is measured first as an enduring personality trait (trait anxiety) and second, his or her tendency to defensively avoid unpleasant emotions, in terms of social desirability (Krohne & Rogner, 1985). The latter is typically measured using a “social desirability” scale, as individuals who are strongly motivated to behave in socially desirable ways are thought to try to cognitively ward off their anxiety (defensive avoiders). That is, they describe less anxiety because anxiety tends to be something socially undesirable.

The data shown in Table 1 can be described as follows:

Individuals with low trait anxiety and low scores in defensiveness are thereby referred to as non-defensive. Non-defensive individuals are characterized by their high tolerance of emotional arousal and feelings of uncertainty. Depending on the situation, they decide to take a closer look at threatening information or ignore it. It is a flexible, situation-adaptive mode.

Repressors show little anxiety (exhibit low anxiety scores) and high levels of anxiety denial (high social desirability scores). Repressors suffer from low tolerance to arousal and high tolerance to uncertainty. They are classified as low vigilant, meaning there is no absorption and processing of threatening information (Krohne, 2010). It is cognitive avoidance (turning attention away from threatening information), i.e., through consistent stimulus avoidance, they escape emotionally arousing situations. This behavior can be classified as “consistent avoidance” (Krohne & Egloff, 1999). The defender ‘sees’ less, he also ‘talks’ less about it (Herrmann, 1991). It is a rigidly avoidant mode of stimulus processing.

Sensitizers show a lot of anxiety (exhibit high anxiety scores) and only a low tendency to deny anxiety (low social desirability scores). This configuration of high anxiety and low defensiveness has psychological implications. Limits to tolerance of uncertainty are low, whereas those to arousal are high. Their behavior can be described as highly consistently monitoring (vigilant). That is, sensitizers, in order to control their situation, form a kind of cognitive expectancy template to be prepared for all threats. They are armed against the accompanying emotional arousal, and the permanent vigilance keeps their behavior stable. It is a rigidly monitoring mode.

The fourth group, with high anxiety and high defensiveness scores, can be described as highly anxious individuals with a dysfunctional or inconsistent anxiety management pattern. Their threshold and tolerance are markedly low with respect to both uncertainty and emotional arousal. Since at least one of the two ambivalent dimensions, or both, are high (arousal by confronting the stimulus and/or uncertainty by not confronting it), the individuals are in a predicament. This results in unstable behavior: The counterpart to the highly anxious individuals in this construct are the non-defensive individuals.

Studies on the four types of anxiety management have a long and varied tradition. It has been shown that the repressor perspective is a successful perspective in the short term, in contrast to the sensitization perspective (Krohne & Egloff, 1999). These studies cannot be presented in more depth within the scope of this article due to space limitations. However, some studies are interesting with regard to our question concerning the influence of anxiety management types on health psychological variables in the context of the COVID-19 lockdown. There are few direct studies on the association of the COVID-19 lockdown, anxiety management types, and health-related variables. One was conducted in 2020 by Mueller-Haugk and Stueck (2022), who confirmed the findings of Krohne and Egloff (1999) that the repressor perspective appears to be a successful short-term coping strategy and thus increased positive correlations with health variables were observed (cf. Mueller-Haugk & Stueck, 2022).

In a study by Bidzan-Bluma et al. (2020), it was found that the older population aged 60 years and older had significantly better coping skills with a higher score of wellbeing during COVID-19, in contrast to middle age and young age. These results were confirmed by another sample from Portugal (Candeias et al., 2021). In the Pandemic Management Theory from Stueck (2021), wellbeing and psychological health are related to the anxiety management types. Sensitizers, repressors, and highly anxious can be summarized as problematic anxiety management types.

In the von Hoor (2008) study on the influence of anxiety management type on certain forms of empathy, it was found that the negative anxiety management types (highly anxious, sensitizer and repressor) showed higher empathy in fictional situations than the “non-defensive” anxiety management type. This showed a significant mean difference between the “non-defensives” and the “sensitizers” (p = .016). In a study by Stueck et al. (2013) for a differentiated view of empathy, it was found that individuals with high affective empathy also showed significantly high values in negative behaviors, related to their professional situation. These included, for example, excessive professional commitment, a high tendency for exhaustion and a low ability to distance oneself from the problems of work and career (Stueck et al., 2013).

Regarding the relationship between the anxiety management types and the health psychological variables related to COVID-19, there are very few studies. Therefore, in addition to the anxiety management types, different variables were investigated by means of R-S construct analysis, which are shown in Table 2.

In the context of anxiety management types, the experience of coherence plays a significant role. Coherence can be defined as “a global orientation that expresses the extent to which one has a generalized, enduring, and dynamic sense of confidence that one’s internal and external environment is predictable and that there is a high probability that things will turn out as one might reasonably expect” (Antonovsky, 1979, p. 123). The coherence model shows positive correlations to various health-related parameters such as well-being and mental health (Schuhmacher et al., 2000). Likewise, there is a connection between the coherence experience and physiological health parameters here; however, not so clearly and intensively, it is assumed that the quasi-coherence takes an indirect mediating role and the physical health is expressed through the actual coping behavior in stressful situations (Schumacher et al., 2000).

AIM AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The aim of our project was to assess to what extent the distributions of anxiety management types differ between the German and Polish samples.

Question 1: To what extent do the distributions of anxiety management types differ between the samples from Germany and Poland?

Question 2: What are the differences in health variables between Germany and Poland?

Question 3: What are the differences in the coping-related, self-regulatory health variable of “being able to switch off” in relation to the anxiety management types between the population of Germany and the population of Poland?

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

The present study was methodologically implemented as follows.

SCHEDULE

The study started 5 days after the corona-related lockdown in Germany, as of 03/27/2020. The lockdown in Germany was decided on 03/16/2020 and implemented on 03/22/2020 and lasted for seven weeks. During this period of intense public restriction, a second process survey was conducted on health-related variables and anxiety management types. The data collection period for the present study of the German and Polish samples was March to April 2020.

The research project was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee (decision no. 30/2020) at the Institute of Psychology at the University of Gdansk, Poland.

SAMPLING PLAN

The German sample consisted of 323 subjects with an average age of 46 years (SD = 12.5). The Polish sample consisted of 100 subjects with an average age of 42 years (SD = 15.4). In both the Polish and German samples, females accounted for 73%. The proportion of men in the German sample was 26% and in the Polish sample 27%.

VARIABLE PLAN AND METHODS OF DATA COLLECTION FOR THE QUESTIONS

In the present study, the following health-related variables and anxiety management types were collected using the measurement procedures presented in Table 2.

Methods of data analysis for research question 1. In the context of this study, among others, the anxiety management types were analyzed according to Krohne’s multidimensional R-S construct (Byrne, 1961; Krohne, 1974; cit. in Grimm, 2013). The analysis of these anxiety management types was conducted using the statistical processing of two standardized scales: the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Laux, 1981) and the Social Desirability Questionnaire (Kemper et al., 2012). Using t-value transformation and z-value analysis, the anxiety types were then classified. This means that participants with low values (t-value < 55) for anxiety and social desirability were classified as “non-defensive”, while participants with low values for anxiety but high values (t-value > 55.1) for social desirability were classified as “repressors”. According to this scheme, participants with high anxiety values and low social desirability values were classified as “sensitizers” and participants with high anxiety and social desirability values were classified as “highly anxious”.

The results were presented as descriptive statistics (percentage frequency distributions). Comparison in terms of distribution differences was performed using descriptive statistics.

Methods of data analysis for research question 2. The data were first examined for their normal distribution, using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Due to the analysis of independent samples divided into two groups, a t-test for independent samples was applied in the further course if a normal distribution was present; if a normal distribution was not present, the Mann-Whitney U test was used as a non-parametric test. The results were assessed according to the usual guidelines: p ≤ .01 highly significant; p ≤ .05 significant; p ≤ .10 statistical trend (Döring & Bortz, 2015). Subsequently, the effect size of significance was calculated using Cohen’s r (Cohen, 1992). According to Cohen, the intervals for evaluating the effect size are r = 0.1 (low), r = 0.3 (medium), r = 0.5 (strong).

Methods of data analysis for research question 3. The anxiety management types analyzed as described above were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In the absence of normal distribution, the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test was used for comparative analysis, and pairwise comparisons of means were made using the Dunn-Bonferroni post hoc test. In the presence of a normal distribution, simple ANOVA was used. The effect size of the significances was calculated using Cohen’s r (cf. Cohen, 1992). According to Cohen, the intervals for evaluating the effect strength are r = 0.1 (low), r = 0.3 (medium), r = 0.5 (strong).

RESULTS

RESULTS FOR QUESTION 1

The results regarding question 1 are presented in Tables 3 and 4. The frequency distribution of the anxiety management types of the Polish and German samples shows significant differences (p < .001).

Table 3.

Frequency distribution for anxiety management types – German sample

| Anxiety management type | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Non-defensive | 155 | 48.0 |

| Sensitizer | 57 | 17.6 |

| Repressor | 94 | 29.1 |

| Highly anxious | 17 | 5.3 |

| Total | 323 | 100.0 |

Table 4.

Frequency distribution for anxiety management types – Polish sample

| Anxiety management type | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Non-defensive | 40 | 40.0 |

| Sensitizer | 33 | 33.0 |

| Repressor | 18 | 18.0 |

| Highly anxious | 9 | 9.0 |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 |

RESULTS FOR QUESTION 2

With regard to country specificity, ten of twelve variables examined showed significant mean differences with small to medium effect sizes; see Table 5 to Table 9.

Table 5.

Resources variable mean difference between Germany and Poland

| Variable | Germany | Poland | p | r | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Coherence | 48.89 | 8.92 | 42.51 | 9.68 | .001 | .29 |

Table 9.

Behavioral variable mean difference between Germany and Poland

| Variable | Germany | Poland | p | r | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Urge to move | 3.31 | 0.97 | 3.59 | 1.39 | .042 | .10 |

Table 6.

Coping variable mean difference between Germany and Poland

| Variable | Germany | Poland | p | r | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Ability to switch off | 3.90 | 2.40 | 4.45 | 2.93 | .142 | .07 |

Table 7.

Cognitive variable mean difference between Germany and Poland

| Variable | Germany | Poland | p | r | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Ashamed emotional reaction | 1.29 | 0.70 | 1.40 | 0.92 | .392 | .04 |

| Felt guilty that more was not done | 1.31 | 0.67 | 1.75 | 1.23 | .001 | .17 |

Table 8.

Emotional variable mean difference between Germany and Poland

| Variable | Germany | Poland | p | r | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Trauma | 21.63 | 7.06 | 27.17 | 9.11 | .001 | .28 |

| Optimism | 6.67 | 2.33 | 5.99 | 2.30 | .010 | .13 |

| Nervous free of complaints | 4.68 | 1.68 | 3.35 | 1.38 | .001 | .33 |

| Feeling helpless | 1.91 | 1.09 | 2.56 | 1.18 | .001 | .25 |

| Sadness | 2.04 | 1.15 | 2.52 | 1.32 | .001 | .16 |

| Fear of personal safety | 1.84 | 1.08 | 2.75 | 1.31 | .001 | .32 |

| Losing control over feelings | 1.37 | .82 | 1.79 | 1.18 | .001 | .20 |

| Frustrated angry | 2.26 | 1.20 | 2.77 | 1.29 | .001 | .17 |

RESULTS FOR QUESTION 3

Regarding question 3, no significant differences (p = .142) were found between the nationalities German and Polish in the expression of the characteristic “ability to switch off”. The results of the Kruskal-Wallis test showed significant differences between the individual anxiety management types for both nationalities (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Kruskal-Wallis test for “ability to switch off” in relation to the anxiety management types – German sample

Note. alow value = high ability to switch off.

Figure 3.

Kruskal-Wallis test for “ability to switch off” in relation to the anxiety management types – Polish sample

Note. alow value = high ability to switch off.

For the German sample the following four significant differences between the individual anxiety management types were found:

Highly anxious – Repressor (p < .001),

Highly anxious – Non-defensive (p = .001),

Repressor – Sensitizer (p < .001),

Sensitizer – Non-defensive (p < .001).

Two significant differences in anxiety management types were found in the Polish sample:

Non-defensive – Sensitizer (p < .001),

Repressor – Sensitizer (p = .029).

DISCUSSION

An important aim of our project was to assess to what extent the distributions of anxiety management types differ between the samples of Germany and Poland.

In the Polish sample, 60% showed negative anxiety management types (Sensitizer, Repressor, Highly anxious), compared to the German sample with 52%. Accordingly, 40% of the Polish and 48% of the German sample showed positive expressions.

Since there are stronger significant differences in both samples regarding the health-related variables to the disadvantage of the Polish sample, it can be concluded that these variables are subject to a nationality-specific influence. This concerns both the cognitive variables (guilt) and all emotional health-related variables as well as the resource variable “sense of coherence”.

Cross-country differences in anxiety severity and coping-related, self-regulatory health variable of “being able to switch off” in relation to the anxiety management types may be related to such things as different histories. Poland has faced many negative historical experiences, including 123 years of being conquered and oppressed, followed by two world wars and fifty years of communism (Zarycki & Warczok, 2020). Consequently, Poles may experience transgenerational transmission of trauma (Nowak & Łucka, 2014). Some researchers suggest that transgenerational trauma may be national in nature, and Poles are said to be a traumatized nation (which is manifested in such things as a tendency to experience unpleasant feelings or triggering a non-defensive or sensitizer anxiety management type) (Zarycki & Warczok, 2020). Research shows that the impact of the war-related trauma is not limited to veterans but also extends to their children and partners, who are negatively affected as they surround and care for the war veteran (Dirkzwager et al., 2005; Pearrow & Cosgrove, 2009; Rosenheck & Fontana, 1998).

Whether or not we can speak of a transgenerational trauma depends on many factors, primarily on whether our parent or grandparent was able to cope with the experience. There are many various emotions that emerge from trauma. Some people are in denial as they wish to avoid going through the emotions associated with a traumatic experience.

The results we obtained related to the emotional health variables may also be related to the religions dominant in the studied countries, namely Protestantism in Germany, which is closely related to the cult of work and being able to handle things, and Catholicism in Poland, which is one of the Christian religions associated with the feeling of guilt (Walinga et al., 2005). This may be related to feeling guilty, which is characteristic of Poles, whereas in the case of Germany, it is about mobilizing effective methods of coping with stress or greater optimism.

In addition, it should be noted that Poland has a very high percentage of religious people in the population (> 95%), whereas in Germany only 50% of the population belongs to a religion (FoWiD, 2021; University Luzern, 2019). The official data on the distribution of religious denomination affiliation in Poland confirm a high affiliation to the Catholic Church for the age group that participated in our study (Ciecieląg et al., 2019).

The results we obtained regarding the Polish population also show a lower sense of coherence (SOC), which is considered a protective factor for mental health in a crisis that might also be decisive during the COVID-19 pandemic, but the mechanisms are not yet well understood (Kulcar et al., 2023). It should be pointed out that a sense of coherence is an important concept within salutogenesis and is connected to the individual experiences affecting how we manage and use resources and how we cope with stressors, which in the case of the Polish population is less effective than in the German population (Antonovsky, 1979, 1997; Blättner, 2007).

A different lifestyle, including health-related, and by extension mobilizing different styles of anxiety management type or manifestations of emotional variables in the face of a pandemic in the background may be rooted in socialism, although a part of Germany (i.e. the German Democratic Republic) was also a socialist country.

Braga et al. (2012) emphasized that not just traumatic encounters, but also patterns of resilience can be passed on to and cultivated by the succeeding generation. Therefore, one must keep in mind that even when we experience trauma, it does not necessarily need to translate into experiencing negative symptoms such as anxiety or stress; on the contrary, many people experience post-traumatic growth (Rush, 2021; Skrodzka et al., 2020).

Furthermore, it must be noted that the factors influencing the ability to cope with the pandemic-related challenge are much more far-reaching. For example, socio-demographic aspects such as age, level of education or even economic independence play an important role in the ability to cope with challenges and promote mental health (Bardehle et al., 2001; Kondirolli & Sunder, 2022).

Concerning the necessary intervention, it can be deduced that coping offers should be submitted regarding an improvement of emotion regulation, as well as cognitive-oriented intervention regarding the reduction of stress perception. It would be interesting to investigate further to what extent ethical values and moral concepts or religious influences play a role. Regarding the sense of coherence, it has to be stated that the lower value in the Polish sample shows the necessity for using interventions. Usually, the sense of coherence can be promoted through relaxation methods, the promotion of reflective activities in the form of discussion circles, self-actualization training, etc. Further recommendations in this regard can be found in the action areas of the Pandemic Management Theory (Stueck, 2021) – among others, an increase in effective communication, promotion of lively corporality, expansion of ethical awareness, and strengthening of life potentials (creativity, vitality, transcendence/spirituality). Pre-post-test analyses would have to further investigate to what extent emotion-oriented and cognition-oriented interventions can raise the sense of coherence. This conjecture is fed by the correlative relationships that could be demonstrated in the Polish sample. With reference to the scientific study by Liu et al. (2021) in China, in which the influence of lockdown techniques on the mental well-being of residents was investigated, it was found that lockdown measures have a proven negative effect. In this context, it can be assumed that the complexity of mental health is subject to a multitude of influencing variables and thus a purely statistical study will not be sufficient to reflect this.

The results concerning the correlations between “not being able to switch off” and the negative anxiety types in both groups can be interpreted to the effect that this correlation is obviously independent of nationality, since it can be seen in both samples that the forms of expression of the variable “not being able to switch off” in relation to the anxiety management styles are mostly similar. The negative anxiety management styles are associated with a significantly worsened “ability to switch off”. This result suggests that the cognitive styles for coping with anxiety are, on the one hand, of great importance from a health psychological point of view and, on the other hand, apparently represent a highly manifested personality trait. As Francesco et al. (2010) also found, relaxation methods lead to an improvement in the individual’s sense of anxiety. With reference to this study, the question arises whether the individuals have a better anxiety management type due to their personal relaxation ability or whether this in turn influences the relaxation ability. Continuing studies should examine the consistency of the cognitive anxiety management styles in a long-term comparison to look at this hypothesis in more detail. In assessing the scientific quality of the present article, the following aspects need to be considered. First, the sample size should be noted as a key consideration. Here it is pointed out that the sample was relatively small, which precludes the representativeness of the results. In order to be able to draw more meaningful conclusions, a larger and more diverse sample would be desirable.

Another critical point concerns the recording of anxiety management types by means of an indirect measurement procedure. This approach has both advantages and disadvantages. Indirect measurement can help to capture unconscious or hard-to-reach aspects that might not be obtained through direct questioning. However, uncertainties and problems of interpretation may also be associated with them. It is important to consider the limitations of such measurement methods and to interpret the results accordingly.

The holistic approach of the article and the use of a variety of anxiety management questions should be highlighted. The use of a wide range of questions can help to cover different dimensions of anxiety management and provide a more comprehensive picture. This aspect contributes to strengthening scientific quality.

However, it should also be criticized that many questions in the survey were self-generated. This may pose potential problems in terms of validity and reliability. Self-generated questions may not have the same quality as standardized and validated measurement instruments. A more comprehensive consideration of the underlying psychometric properties of the questions would be desirable.

Furthermore, the back translation method was used for the translation of the individual questions. It should be noted that this method may have certain limitations. In this method, the text is back-translated to check for consistency with the original text. However, cultural differences or nuances may be lost in the process.

It is necessary to note that the results of this study are not representative due to the fact of the amount of study participants and the unequal distribution between the German (n = 323) and Polish (n = 100) sample.

Footnotes

TO CITE THIS ARTICLE – Mueller-Haugk, S., Bidzan-Bluma, I., Bidzan-Wiącek, M., Bulathwatta, D. T., & Stueck, M. (2023). Anxiety and coping during COVID-19. Investigation of anxiety management types in a German and Polish sample. Health Psychology Report, 11(4), 282–294. https://doi.org/10.5114/hpr/171884

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Antonovsky, A. (1979). Health, stress and coping: New perspectives on mental and physical well-being. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky, A. (1997). Salutogenese: Zur Entmystifizierung der Gesundheit [Salutogenesis: Demystifying health]. German Society for Behavioral Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, R. J., & Nellums, L. B. (2020). COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. The Lancet. Public Health, 5, e256. 10.1016/s2468-2667(20)30061-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardehle, D., Blettner, M., & Laaser, U. (2001). Gesundheits-und soziodemographische (sozialepidemiologische) Indikatoren in der Gesundheits-und Sozialberichterstattung [Health and sociodemographic (social epidemiological) indicators in health and social reporting]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt–Gesundheitsforschung–Gesundheitsschutz, 44, 382–393. 10.1007/s001030050456 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bidzan-Bluma, I., Bidzan, M., Jurek, P., Bidzan, L., Knietzsch, J., Stueck, M., & Bidzan, M. (2020). A Polish and German population study of quality of life, well-being, and life satisfaction in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 585813. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.585813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blättner, B. (2007). Das Modell der Salutogenese [The model of salutogenesis]. Prevention and Health Promotion, 2, 67–73. 10.1007/s11553-007-0063-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braga, L. L., Mello, M. F., & Fiks, J. P. (2012). Transgenerational transmission of trauma and resilience: a qualitative study with Brazilian offspring of Holocaust survivors. BMC Psychiatry, 12, 134. 10.1186/1471-244X-12-134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet, A., Weiss, D. J., Metzler, T. J., Best, S. R., Neylan, T. C., Rogers, C. E., Fagan, J., & Marmar, C. R. (2001). The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory: a proposed measure of PTSD criterion A2. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 1480–1485. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, D. (1961). The Repression-Sensitization Scale: Rational, reliability and validity. Journal of Personality, 29, 334–349. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1961.tb01666.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candeias, A., Galindo, E., Stueck, M., Portelada, A. F. S., & Knietzsch, J. (2021). Psychological adjustment, quality of life and well-being in a german and portuguese adult population during COVID-19 pandemics crisis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 674660. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.674660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciecieląg, P., Bieńkuńska, A., Góralczyk, A., Gudaszewski, G., Piasecki, T., & Sadłoń, W. (2019). Religious denominations in Poland 2015-2018. Główny Urząd Statystyczny.

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Quantitative methods in psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155–159. 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirkzwager, A. J. E., Bramsen, I., Ader, H., & van der Ploeg, H. M. (2005). Secondary traumatization in partners and parents of Dutch peacekeeping soldiers. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 217–226. 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillard, A. J., Lester, J. C., & Holyfield, H. (2022). Associations between COVID-19 risk perceptions, behavior intentions and worry. Health Psychology Report, 10, 139–148. 10.5114/hpr.2022.114477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Maggio, I., Romola, M., Lacava, E., Maressa, R., & Bruno, F. (2022). Dealing with COVID-19 stressful events, stress and anxiety: The mediating role of emotion regulation strategies in Italian women. Health Psychology Report, 11, 70–80. 10.5114/hpr/152331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döring, N., & Bortz, J. (2015). Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften. [Research methods and evaluation in the social and human sciences]. Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- FoWiD (2021). Religionszugehörigkeiten 2021 [Religious affiliations 2021]. Forschungsgruppe Weltanschauung in Deutschland. Retrieved from https://fowid.de/meldung/religionszugehoerigkeiten-2021 [accessed July 10, 2023]

- Francesco, P., Mauro, M. G., Gianluca, C., & Enrico, M. (2010). The efficacy of relaxation training in treating anxiety. The International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 5, 264–269. 10.1037/h0100887 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, J. (2013). Repression-Sensitization Scale nach Byrne-Krohne [Repression-Sensitization Scale by Byrne-Krohne]. Retrieved from https://empcom.univie.ac.at/fileadmin/user_upload/p_empcom/pdfs/Grimm2013_Sensitization-Repression_MFWorkPaper2013-01.pdf [accessed April 5, 2023]

- Herrmann, T. (1991). Lehrbuch der empirischen Persönlichkeitsforschung [Textbook of empirical personality research]. Hogrefe

- Kemper, C. J., Beierlein, C., Bensch, D., Kovaleva, A., & Rammstedt, B. (2012). Eine Kurzskala zur Erfassung des Gamma-Faktors sozial erwünschten Antwortverhaltens: Die Kurzskala Soziale Erwünschtheit-Gamma (KSE-G) [A short scale to assess the gamma factor of socially desirable response behaviour: The Social Desirability Gamma (KSE-G) short scale]. GESIS – Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Kondirolli, F., & Sunder, N. (2022). Mental health effects of education. Health Economics, 31, 22–39. 10.1002/hec.4565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krohne, H. (1974). Untersuchungen mit einer deutschen Form der Repression-Sensitization-Scale [Studies with a German form of the Repression-Sensitization Scale]. Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie, 3, 238–260. [Google Scholar]

- Krohne, H. (1986). Die Messung von Angstbewältigungs Dispositionen I. Theoretische Grundlagen und Konstruktionsprinzipien [The measurement of anxiety coping dispositions I. Theoretical foundations and construction principles]. Psychologisches Institut, Johannes-Gutenberg-Universität.

- Krohne, H. (2010). Psychologie der Angst: Ein Lehrbuch [Psychology of anxiety: a textbook]. Kohlhammer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Krohne, H., & Rogner, J. (1985). Mehrvariablen-Diagnostik in der Bewältigungsforschung [Multivariate assessment in coping research]. In H. W. Krohne (Ed.), Angstbewältigung in Leistungssituationen [Coping with fear in performance situations] (pp. 45–62). Edition Psychologic [Google Scholar]

- Krohne, H. W., & Egloff, B. (1999). Das Angstbewältigungsinventar: ABI. Manual [The Anxiety Management Inventory]. Swets Test Services [Google Scholar]

- Kulcar, V., Kreh, A., Juen, B., Siller, H. (2023). The role of sense of coherence during the COVID-19 crisis: Does it exercise a moderating or a mediating effect on university students’ wellbeing? Sage Open, 13, 21582440231160123. 10.1177/21582440231160123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laux, L. (1981). Das State-Trait-Angstinventar: theoret. Grundlagen und Handanweisung [The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: theory. Basics and manual]. Beltz. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Launier, R. (1978). Stress-related transactions between person and environment. In L. A. Pervin & M. Lewis (Eds.), Perspectives in interactional psychology (pp. 287–327). Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4613-3997-7_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., Zhou, D., & Geng, X. (2021). Can closed-off management in communities alleviate the psychological anxiety and stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic? International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 37, 228–241. 10.1002/hpm.3330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller-Haugk, S., & Stueck, M. (2022). Relationship of anxiety management types and health-related variables of people during lockdown in a German sample. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly, 8, 65–76. 10.32598/hdq.8.1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, P., & Łucka, I. (2014). A young Pole after experiences of the war. The might of transgenerational transmission of trauma. Psychiatria i Psychologia Kliniczna, 14, 84–88. 10.15557/Pipk.2014.0010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearrow, M., & Cosgrove, L. (2009). The aftermath of combat-related PTSD: Toward an understanding of transgenerational trauma. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 30, 77–82. 10.1177/1525740108328227 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rohmert, W., & Rutenfranz, J. (1975). Arbeitswissenschaftliche Beurteilung der Belastung und Beanspruchung an unterschiedlichen industriellen Arbeitsplätzen [Occupational science assessment of stress and strain at different industrial workplaces]. Der Bundesminister für Arbeit und Sozialordnung.

- Rosenheck, R., & Fontana, A. (1998). Transgenerational effects of abuse violence on the children of Vietnam combat veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 11, 731–742. 10.1023/A:1024445416821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy, D., Tripathy, S., Kar, S. K., Sharma, N., Verma, S. K., & Kaushal, V. (2020). Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety and perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102083. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush, A. (2021). Exploring trauma, loss, and posttraumatic growth in poles who survived the Second World War and their descendants [Ph.D. dissertation]. Montclair State University. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.montclair.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1759&context=etd [accessed July 25, 2023]

- Schröder, H. (1992). Emotionen–Persönlichkeit–Gesundheitsrisiko [Emotions–personality–health risk]. Psychomed Zeitschrift Für Psychologie Und Medizin, 4, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, J., Gunzelmann, T., & Brähler, E. (2000). Sense of Coherence Scale von Antonovsky. Teststatistische Überprüfung in einer repräsentativen Bevölkerungsstichprobe und Konstruktion einer Kurzskala [Sense of Coherence Scale by Antonovsky. Test statistic verification in a representative population sample and construction of a short scale]. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie, 50, 472–482. 10.1055/s-2000-9207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, P., & Charteris, J. (2003). Stress, strain–what’s in a name? Ergonomics SA, 15, 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Skrodzka, M., Hansen, K., Olko, J., & Bilewicz, M. (2020). The twofold role of a minority language in historical trauma: The case of Lemko minority in Poland. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 39, 551–556. 10.1177/0261927X20932629 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stueck, M. (2021). The Pandemic Management Theory. COVID-19 and biocentric development. Health Psychology Report, 9, 101–128. 10.5114/hpr.2021.103123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stueck, M., Sakti Kaloeti, D. V., Kankeh, H., Farokhi, M., & Bidzan, M. (2023). Biocentric development: Studies on the consequences of COVID-19 towards human growth and sustainability. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1176314. 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1176314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stueck, M., Schoppe, S., Lahn, F., & Toro, R. (2013). Was nützt es sich in jemanden hineinzuversetzen, ohne zu handeln? Untersuchung zur Integration des prosozialen Handelns in das westliche Empathiekonzept in Form eines Messinstruments zur ganzheitlichen Erfassung von Empathie [What good is it to empathize with someone without acting? Investigation into the integration of prosocial action into the Western concept of empathy in the form of a measurement instrument for the holistic assessment of empathy]. ErgoMed, 6, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- University Luzern (2019). Dataset comparison – Poland in period 2006-2015. Swiss Metadatabase of Religious Affiliation in Europe. Retrieved from https://www.smredata.ch/en/data_exploring/region_cockpit#/mode/dataset_comparison/region/POL/period/2010/presentation/table [accessed June 7, 2023]

- Van Hoor, M. (2008). Der Einfluss des Reizwechsels auf die Empathie bei der Krimirezeption unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Dimension Angstbewältigung Eine empirische Untersuchung anhand der amerikanischen Krimiserie CSI und der deutschen Krimiserie RIS [Magisterarbeit] [The influence of stimulus change on empathy in crime reception with special consideration of the dimension of coping with fear an empirical investigation based on the American crime series CSI and the German crime series RIS (Master’s thesis)]. Universität Wien.

- Walinga, P., Corveleyn, J., & Van Saane, J. (2005). Guilt and Religion: The influence of orthodox Protestant and orthodox Catholic conceptions of guilt on guilt-experience. Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 27, 113–135. 10.1163/008467206774355330 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zarycki, T., & Warczok, T. (2020). The social construction of historical traumas: The Polish experience of the uses of history in an intelligentsia-dominated polity. European Review, 28, 911–931. 10.1017/S1062798720000344 [DOI] [Google Scholar]