Abstract

Objective

Adequate iodine intake is essential for growing children, and thyroid volume (Tvol) is considered as an indicator of iodine status. We investigated Tvol and goiter using ultrasonography (US) and their association with iodine status in 228 6-year-old children living in Korea.

Methods

Iodine status was assessed using urine iodine concentration (UIC) and categorized as deficient (<100 μg/L), adequate (100–299 μg/L), mild excess (300–499 μg/L), moderate excess (500–999 μg/L), and severe excess (≥1000 μg/L). Tvol was measured using US, and a goiter on the US (goiter-US) was defined as Tvol greater than 97th percentile value by age- and body surface area (BSA)-specific international references.

Results

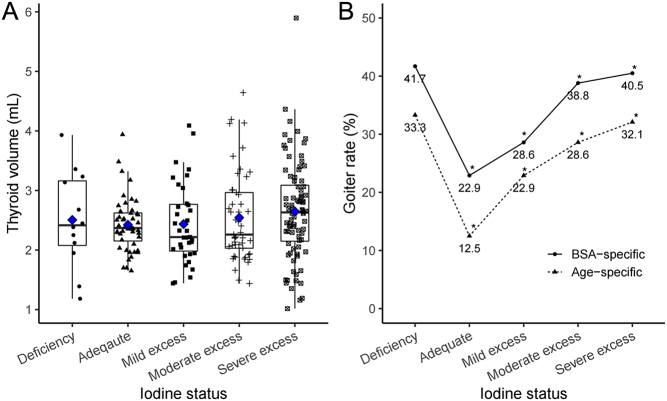

The median Tvol was 2.4 mL, larger than the international reference value (1.6 mL). The age- and BSA-specific goiter-US rates were 25.9% (n = 59) and 34.6% (n = 79), respectively. The prevalence of excess iodine was 73.7% (n = 168). As iodine status increased from adequate to severe excess, the goiter-US rate significantly increased (P for trend <0.05). The moderate and severe iodine excess groups showed higher risk of goiter-US (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 3.1 (95% CI: 1.1–9.2) and aOR = 3.1 (95% CI: 1.2–8.3), respectively; age-specific criteria) than the iodine-adequate group.

Conclusions

Excess iodine was prevalent in Korean children, and their Tvol was higher than the international reference values. Goiter rate was associated with iodine excess, which significantly increased in the moderate and severe iodine excess groups. Further studies are warranted to define optimal iodine intake in children.

Keywords: iodine, thyroid, goiter, Republic of Korea

Introduction

Adequate iodine intake is essential in growing children because both iodine deficiency and excess can adversely affect thyroid function (1, 2). Thyroid volume (Tvol) and goiter rate have been regarded as indicators of the long-term iodine nutritional status in the population. A total goiter rate of ≥ 5% in school-aged children has been used as a criterion for iodine deficiency (3).

With successful iodine fortification and monitoring programs, goiters associated with iodine deficiency have nearly disappeared in many countries (4). Nevertheless, there is increasing concern regarding the adverse effects of excess iodine intake (1). Some studies have revealed increased risk of goiter, much higher than 5%, in children with excess iodine intake (5, 6, 7, 8). However, the impact of excess iodine intake on thyroid function and the possibility of goiter in children remains unclear.

Iodine excess is defined as a urine iodine concentration (UIC) over 300 μg/L based on the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria (3); however, optimal iodine intake ranges in children have not been determined. For example, a study performed in an international sample of 6–12-year-old children reported that UIC ≥ 500 μg/day was related to increasing Tvol (5), whereas another study including 7–14-year-old Chinese children suggested that Tvol and goiter rate showed a nonlinear association, with a threshold iodine intake of 150 μg/day (6).

South Korea is an iodine-sufficient area (9), and a recent nationwide study reported an association between excess iodine and thyroid dysfunction in adolescents (10). In our previous study, we reported the effects of excess iodine on thyroid hormone levels in 6-year-old children (11). However, there is lack of evidence regarding the relationship between iodine status and thyroid US findings in healthy Korean children. Herein, we evaluated the Tvol, goiter rate, the presence of focal lesions assessed by thyroid ultrasound (US), and the relationship between iodine status and Tvol and goiter rate to determine the optimal iodine intake in 6-year-old Korean children.

Materials and methods

Participants

This study used the data of the Environment and Development of Children (EDC) cohort study, which investigated the influence of early-life environmental exposures on physical and neurobehavioral development in children (12). Among the 574 6-year-old children examined during 2015–2017, 230 children underwent thyroid US in 2016. After excluding two children with congenital hypothyroidism, 228 children (123 boys) were included in this study. This study was performed in accordance with the guidelines of Helsinki Declaration. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB no. 1704-118-848) and informed consent was waived.

Clinical assessments

Height (cm) and weight (kg) were measured, and the body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight divided by squared height (kg/m2). Height, weight, and BMI Z-scores were calculated according to the 2007 Korean National Growth Charts (13). Body surface area (BSA) was calculated as follows: BSA (m2) = weight (kg)0.425 × height (cm)0.725 × 71.84 × 10−4 (14). Two pediatric endocrinologists evaluated for goiter on physical examination (goiter-PE) by palpation. Data on socioeconomic status and parental history of thyroid disease were collected.

Iodine status

Urine iodine concentration (UIC, μg/L) and urinary creatinine (Cr) levels were measured from spot morning urine samples collected within 3 days prior to thyroid US examination. Detailed methods of UIC and Cr measurements have been previously described (11). Iodine status was categorized as follows: iodine deficient (UIC: <100 μg/L), adequate (UIC: 100–299 μg/L), and excess (UIC: ≥ 300 μg/L) (15). The excess group was divided into mild excess (UIC: 300–499 μg/L), moderate excess (UIC: 500–999 μg/L), and severe excess (UIC: ≥1000 μg/L) subgroups for the analysis. Estimated 24 h-urine iodine excretion (UIE) (μg/day) was calculated as follows: estimated 24 h-UIE (μg/day) = iodine/Cr (μg/g) × predicted 24 h-Cr excretion (g/day) (16).

Thyroid ultrasound evaluation

Thyroid US was performed on the day of blood testing by a single experienced operator who was blinded to the iodine status and thyroid function of the participants using a US device equipped with a 5–15 MHz linear transducer (Logiq E9, GE Healthcare). First, each middle lobe’s maximum width, length, and depth were measured to evaluate Tvol. The Tvol of each lobe was calculated using the formula Tvol (mL) = 0.479 × width (cm) × length (cm) × depth (cm) (17), and the lobe volumes were summed, excluding the volume of the isthmus. Goiter on the US (goiter-US) was defined as Tvol greater than 97th percentile by age- or BSA-specific reference values of Tvol according to the international reference (18). Second, the findings of focal lesions such as thyroid cysts, nodules, or intrathyroidal thymus (ITT) were investigated. The detected thyroid nodules or ITTs were followed up. The size and characteristics of the thyroid nodules were evaluated using the Korean Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (K-TIRADS) (19).

Measurements of thyroid function

Free thyroxine (FT4) and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) were measured using a chemiluminescent microparticle immune assay on an ARCHITECT i2000 System (Abbott Korea). The reference range was defined as 0.70–1.48 ng/dL (9.01–19.05 pmol/L) for FT4 and 0.38–4.94 mIU/L for TSH, respectively. Subclinical hypothyroidism was defined as TSH levels at 5–10 mIU/L with normal FT4 levels (20).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using the R statistical software package (version 4.0.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). After testing for normality, all continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or as the median with interquartile range (IQR). The iodine variables and TSH levels were naturally log-transformed for analysis. The participants’ characteristics were compared using Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test, one-way analysis of variance or Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables, and the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Linear and logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate the relationships between iodine status, Tvol, and goiter. Multivariate models were constructed with covariates, including age, sex, and BMI Z-scores, derived from a directed acyclic graph. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Clinical characteristics of participants

Table 1 shows clinical characteristics of 228 children (123 boys and 105 girls). The mean age at evaluation was 5.9 ± 0.1 years. The mean BMI Z-score was −0.1 and BSA was 0.8 m2 without sex-differences. Palpable goiter-PE was found in 43 (18.9%) patients with higher proportion in girls (32.4% vs 7.3%, P < 0.001). The median TSH level was 2.5 mIU/L (IQR: 1.8–3.3) and 15 (6.6%) patients had subclinical hypothyroidism. No children had a TSH level greater than 10 mIU/L. The median UIC and estimated 24 h-UIE was 623.5 μg/L (IQR: 278.0–1468.9) and 327.3 μg/day (IQR: 156.1–771.9), respectively. Iodine was deficient in 12 (5.3%), adequate in 48 (21.2%), and excessive in 168 (73.7%). As most of the children had iodine excess, the excess group was divided into mild excess (UIC: 300 to 499 μg/L, n = 35, 15.4%), moderate excess (UIC: 500–999 μg/L, n = 49, 21.5%), and severe excess group (UIC: ≥ 1000 μg/L, n = 84, 36.8%) for further analysis. There were no significant differences in clinical characteristics among the five iodine status groups (Supplementary Table 1, see the section on supplementary materials given at the end of this article).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of study participants. Data are expressed as the mean ± s.d., median (interquartile range), or n (%).

| Variables | Total | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 228 | 123 | 105 |

| Age, years | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 5.9 ± 0.1 |

| Height, cm | 115.7 ± 4.4 | 115.8 ± 4.7 | 115.5 ± 4.1 |

| Weight, kg | 21.1 ± 3.0 | 21.2 ± 3.1 | 21.0 ± 2.8 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 15.7 ± 1.5 | 15.7 ± 1.5 | 15.7 ± 1.6 |

| Height Z-score | 0.39 ± 0.96 | 0.30 ± 0.99 | 0.48 ± 0.92 |

| Weight Z-score | 0.11 ± 0.95 | −0.01 ± 0.94a | 0.24 ± 0.94a |

| BMI Z-score | −0.13 ± 0.96 | −0.19 ± 0.92 | −0.06 ± 1.00 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 0.82 ± 0.06 |

| Palpable goiter at PE | 43 (18.9) | 9 (7.3)a | 34 (32.4)a |

| Parental history of thyroid disease | 10 (4.4) | 8 (6.5) | 2 (1.9) |

| Maternal education level ≥ college | 196 (86.0) | 108 (87.8) | 88 (83.8) |

| UIC, μg/L | 623.5 (278.0–1468.9) | 669.4 (343.2–1497.0) | 565.4 (230.5–1369.7) |

| UIC category | |||

| Iodine deficient (UIC: <100 μg/L) | 12 (5.3) | 3 (2.4) | 9 (8.6) |

| Adequate (UIC: 100–299 μg/L) | 48 (21.1) | 22 (17.9) | 26 (24.8) |

| Excess (UIC: ≥300 μg/L) | 168 (73.7) | 98 (79.7)a | 70 (66.7)a |

| Estimated 24 h-UIE, μg/day | 327.3 (156.1–771.9) | 336.3 (184.4–803.9) | 297.5 (136.0–732.3) |

| Free thyroxine, ng/dL | 1.15 ± 0.11 | 1.16 ± 0.11 | 1.15 ± 0.12 |

| TSH, mIU/L | 2.5 (1.8–3.3) | 2.5 (1.8–3.4) | 2.5 (1.9–3.3) |

| Subclinical hypothyroidism | 15 (6.6) | 8 (6.5) | 7 (6.7) |

| Thyroid volume, mL | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 0.8 |

| Goiter on US (age-specific) | 59 (25.9) | 29 (23.6) | 30 (28.6) |

| Goiter on US (BSA-specific) | 79 (34.6) | 36 (29.3) | 43 (41.0) |

| Focal lesion | |||

| None | 153 (67.1) | 83 (67.5) | 70 (66.7) |

| Cyst | 59 (25.9) | 31 (25.2) | 28 (26.7) |

| Nodule | 3 (1.3) | 2 (1.6) | 1 (1.0) |

| ITT | 13 (5.7) | 7 (5.7) | 6 (5.7) |

aP < 0.05 between boys and girls.

BSA, body surface area; ; ITT, intrathyroidal thymus; PE, physical examination; UIC, urine iodine concentration; UIE, urine iodine excretion; US, ultrasound.

Thyroid volume measurements

The mean Tvol was 2.5 mL and the prevalence of age- and BSA-specific goiter-US was 25.9% (n = 59) and 34.6% (n = 79), respectively, without sex difference (Table 1). Detailed distributions of Tvol according to sex and BSA are described in Supplementary Table 2. The values of 50th and 97th percentile were 2.33 mL and 4.03 mL for boys and 2.52 mL and 4.16 mL for girls, respectively.

Clinical factors associated with thyroid volume and the presence of goiter

Clinical characteristics were compared according to the presence of goiter on the US based on age or BSA-specific criteria. For age-specific criteria, children with goiter-US had higher BMI Z-scores (0.11 vs −0.21, P = 0.030) and palpable goiter at physical examination (33.9% vs 13.6%, P = 0.001) than those without goiter. There were no significant differences in sex, BSA, family history, or thyroid function between the groups (Table 2). For BSA-specific criteria, there were no differences between goiter-US groups in clinical characteristics and thyroid function except palpable goiter rate at physical examination (Supplementary Table 3). There was significant association between BMI Z-scores (β = 0.15, P = 0.002) and BSA (β = 2.23, P = 0.001) and Tvol (Supplementary Table 4).

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical characteristics according to the presence of goiter on the US based on age-specific criteria. Data are expressed as the mean ± s.d., median (interquartile range), or n (%).

| Variables | Goiter-US (−) | Goiter-US (+) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 169 | 59 | |

| Boys, n (%) | 94 (55.6) | 29 (49.2) | 0.999 |

| BMI Z-score | −0.21 ± 0.94 | 0.11 ± 0.97 | 0.030 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 0.83 ± 0.06 | 0.051 |

| Palpable goiter at physical examination | 23 (13.6) | 20 (33.9) | 0.001 |

| Parental history of thyroid disease | 7 (4.1) | 3 (5.1) | 0.999 |

| Maternal education level ≥ college | 146 (86.4) | 50 (84.8) | 0.924 |

| Free thyroxine, ng/dL | 1.17 ± 0.10 | 1.15 ± 0.12 | 0.177 |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone, mIU/L | 2.5 (1.8–3.4) | 2.5 (1.9–3.1) | 0.974 |

| Subclinical hypothyroidism | 13 (7.7) | 2 (3.4) | 0.399 |

| Thyroid volume, mL | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | <0.001 |

| Goiter-US based on BSA-specific criteria | 22 (13.0) | 57 (96.6) | <0.001 |

| Focal lesiona | 44 (26.0) | 31 (52.5) | <0.001 |

aFocal lesion was defined as thyroid cysts, nodules, or intrathyroidal thymus.

BSA, body surface area; US, ultrasound.

Relationship of iodine status with thyroid volume and goiter

The distributions of Tvol and the prevalence of goiter-US among the iodine categories are shown in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1. There were no significant differences in Tvol or goiter-US rate among the five iodine groups. The iodine adequate group showed a lower mean Tvol (2.4 ± 0.5 mL) and goiter-US rate (12.5% for age-specific criteria and 22.9% for BSA-specific criteria, respectively) compared to the iodine deficient or excess groups without statistical significance (Fig. 1A and B). As iodine status increased from adequate to severe excess, the goiter-US rate significantly increased (P for trend = 0.012 for age-specific criteria, 0.028 for BSA-specific criteria, Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Thyroid volume (mL) and (B) goiter on the US rate (%) among the iodine status groups. Iodine status was categorized as iodine deficient (UIC < 100 μg/L), adequate (UIC 100–299 μg/L), mild excess (UIC 300–499 μg/L), moderate excess (UIC 500–999 μg/L), or severe excess (UIC ≥ 1000 μg/L). (A) The blue rhombus indicates the mean values of thyroid volume in each group. (B) Goiter-US was defined as thyroid volume greater than 97th percentile using the World Health Organization age- and body surface area-specific criteria. *P for trend <0.05. UIC, urine iodine concentration; US, ultrasound.

We investigated the association between iodine status and Tvol or goiter rate with the iodine adequate group as the reference category (Table 3). Iodine status was not associated with Tvol after adjustment. However, the moderate and severe iodine excess group showed a significantly higher risk of goiter-US (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 3.1, P = 0.038 for the moderate excess group; aOR = 3.1, P = 0.024 for the severe excess group; age-specific criteria) than the adequate group after adjusting for covariates including age, sex, and BMI Z-scores.

Table 3.

Association between iodine status and thyroid volume and goiter-US.

| Category | UIC, μg/L | n | Thyroid volume (β, 95% CI) | Goiter-US (OR, 95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-specific criteria | BSA-specific criteria | |||||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |||

| Adequate | 100–299 | 48 | 0 (reference) | 0 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Deficient | <100 | 12 | 0.09 (−0.38, 0.54) | 0.07 (−0.39, 0.52) | 3.50 (0.81, 15.29) | 3.40 (0.76, 15.18) | 2.41 (0.64, 9.09) | 2.12 (0.55, 8.13) |

| Mild excessive | 300–499 | 35 | 0.02 (−0.31, 0.33) | −0.01 (−0.33, 0.3) | 2.08 (0.65, 6.65) | 1.94 (0.59, 6.35) | 1.35 (0.5, 3.65) | 1.46 (0.53, 4.01) |

| Moderate excessive | 500–999 | 49 | 0.12 (−0.17, 0.41) | 0.16 (−0.12, 0.45) | 2.80 (0.98, 8.06) | 3.14 (1.07, 9.21)b | 2.14 (0.88, 5.17) | 2.35 (0.95, 5.81) |

| Severe excessive | ≥ 1000 | 84 | 0.23 (−0.04, 0.49) | 0.18 (−0.07, 0.44) | 3.32 (1.26, 8.76)b | 3.11 (1.16, 8.34)b | 2.29 (1.03, 5.10)b | 2.49 (1.09, 5.66)b |

aAdjusted for age, sex, and body mass index Z-scores; bP < 0.05.

OR, odds ratio; UIC, urine iodine concentration; US, ultrasound..

To focus on iodine excess, we performed regression analysis after excluding 12 iodine-deficient children. Log-transformed UIC was significantly associated with risk of goiter-US after adjusting for covariates (aOR = 1.40, P = 0.032 for age-specific criteria; Table 4). Log-transformed estimated 24 h-UIE showed a similar trend, although the result was not statistically significant after adjustment.

Table 4.

Association between continuous iodine variables and thyroid volume and goiter-US. Twelve children with iodine deficiency were excluded from the analysis.

| Variables | Thyroid volume (β, 95% CI) | Goiter-US (OR, 95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-specific criteria | BSA-specific criteria | |||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |

| LT UIC, μg/L | 0.07 (−0.01, 0.18) | 0.08 (−0.02, 0.17) | 1.41 (1.04, 1.90)b | 1.40 (1.03, 1.90)b | 1.36 (1.03, 1.80)b | 1.41 (1.06, 1.87)b |

| LT estimated 24 h-UIE, μg/day | 0.08 (−0.01, 0.18) | 0.07 (−0.03, 0.16) | 1.36 (1.01, 1.84)b | 1.21 (0.91, 1.61) | 1.19 (0.90, 1.57) | 1.21 (0.91, 1.61) |

aAdjusted for age, sex, and body mass index Z-scores; b P < 0.05.

LT, log-transformed; OR, odds ratio; UIC, urine iodine concentration; UIE, urine iodine excretion; US, ultrasound.

Focal lesions on thyroid ultrasound and follow-up

Focal lesions were found in 75 children (32.9%): 59 with thyroid cysts (25.9%), 3 with nodules (1.3%), and 13 with ITT (5.7%) without sex differences (Table 1). Children with goiter-US had a higher proportion of focal lesions (52.5% vs 26.0%, P < 0.001 age-specific criteria, Table 2). Children with focal lesions showed higher Tvol (2.9 vs 2.4 mL, P < 0.001) and proportion of goiter-US (41.3% vs 18.3%, P < 0.001, age-specific criteria) compared to those without focal lesions. No significant associations were observed between UIC and the presence of thyroid cysts or nodules (data not shown).

In three cases of ITT, there were small (median size = 0.7 cm; range: 0.3–1.0 cm) well-defined hypoechoic nodules with numerous internal non-shadowing hyperechoic foci, typical of normal thymic echotexture. All thyroid nodules were less than 1 cm (range: 0.5–0.9 cm) with K-TIRADS scores of 3 (n = 2) and 4 (n = 1) at the time of detection. When follow-up US evaluation was performed in those with nodules, one nodule decreased in size, while others remained unchanged during the median follow-up of 3.9 years. No patient underwent fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB).

Discussion

Among 6-year-old children living in an iodine-sufficient area, the median Tvol was 2.4 mL, and the prevalence of goiter-US was 25.9–34.6% according to age- and BSA-specific criteria. The goiter rate significantly increased as iodine status increased from adequate to severe excess. The moderate and severe iodine excess groups had a higher risk of goiter compared with iodine-adequate group. Thyroid cysts or nodules were found in 25.9% and 1.3% of the children, respectively. No significant relationship was found between the iodine status and the presence of focal lesions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association between iodine status and Tvol or goiter rate in Korean children.

We found a high prevalence of goiter-US (up to 34.6%) in young Korean children, and their median Tvol was larger than that of the international reference value (Supplementary Table 7) (18). In this study, the median UIC was 624 μg/L, and 73.7% of the children had excess iodine, comparable to a recent nationwide study (10). Tvol and goiter rates are classic indicators of long-term iodine status.(3) Thus, the higher goiter rate with increased iodine status in our young children was in line with previous results that showed increased Tvol or prevalence of goiter in children with excess iodine (5, 6, 7, 8).

Variations in Tvol and goiter rates in children have been reported even in long-standing iodine-sufficient countries (Table 5) (18, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27). Genetic and environmental factors, including obesity, dietary habits, and exposure to iodine and other goitrogens, can affect the differences in Tvol among countries (18, 28, 29). Although the WHO has adopted international reference values for Tvol (3), significant differences among countries suggest the need for population-specific criteria, especially in countries with long-standing iodine sufficiency (7, 18, 30). Currently, there has been only one study investigating Tvol in Korean children using computed tomography (27), and our study is the first to evaluate Tvol in healthy children using thyroid US.

Table 5.

Comparison of iodine status and thyroid volume in 6-year-old children living in iodine-sufficient areas.

| Country | Median UICa, μg/L | Iodine excess a, % | Total | Boys | Girls | Reference | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Tvol, mL | Goiter rate, % | n | Tvol, mL | n | Tvol, mL | ||||||||

| P50 | P97 | AS | BSA-S | P50 | P97 | P50 | P97 | |||||||

| South Korea | 623.5 | 73.7 | 228 | 2.4 | 4.1 | 25.9 | 34.6 | 123 | 2.3 | 4.0 | 105 | 2.5 | 4.2 | This study |

| Six countriesb | 203 | 26.4 | 468 | – | – | – | – | – | 1.6 | 2.9 | – | 1.6 | 2.8 | Zimmermann et al. (18) |

| Japan | 281 | 45.9 | 37 | 1.9 | 3.9 | 5.8 | 6.5c | 19 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 18 | 1.9 | 3.8 | Fuse et al. (21) |

| Sweden | 125 | 3.0 | 95 | – | – | 15.7 | 22.3c | 47 | 2.6d | ns | 48 | 2.6d | ns | Nystrom et al. (22) |

| Algeriae | 565 | 84.0 | 55 | 3.0 | ns | 58.2 | ns | – | – | – | – | – | – | Henjum et al. (23) |

| Chinaf | 170 | 18.8 | 416 | – | – | – | – | 209 | 2.7 | ns | 207 | 2.8 | ns | Zou et al. (24) |

| Japan | – | – | 1594 | – | – | – | – | 822 | ns | 5.2 | 772 | ns | 5.1 | Suzuki et al. (25) |

| Spain | 120 | ns | – | – | – | 32 | 5c | – | ns | 3.9 | – | ns | 4.1 | Garcia-Ascaso et al. (26) |

| Koreaf,g | – | – | 61 | – | – | – | – | 37 | 3.6d | ns | 24 | 3.2d | ns | Sea et al. (27) |

aMedian UIC values and prevalence of iodine excess (UIC ≥ 300 µg/L) were derived from study participants of all ages; bCountries include Switzerland, Bahrain, South Africa, Peru, USA, and Japan; cData from all age groups; dMean value; eSaharawi refugee camp; fData from participants 3–6 years of age; gTvol was assessed using computed tomography.

AS, age-specific; BSA-S, body surface area specific; ns, not stated; P50, 50th percentile; P97, 97th percentile; Tvol, thyroid volume; UIC, urine iodine concentration.

In this study, as iodine status increased from adequate to severe excess, the prevalence of goiter on the US increased to 40.5%. The risk of a goiter on the US was positively related to UICs and significantly higher in the moderate to severe iodine excess group (UIC ≥500 μg/L) than in the adequate group, in line with a previous international study reporting an increased Tvol at a UIC of >500 μg/L in school-aged children (5). Several pediatric studies have shown a positive association between iodine intake and Tvol or goiter rate (5, 6, 31, 32), although other studies have shown no significant associations (7, 21, 22, 24, 33). Inconsistent results may be due to the various levels of iodine exposure, genetic predispositions (21), or other environmental factors (34). Excess iodine intake is prevalent among Korean children and adolescents (10); thus, close monitoring for possible health concerns is warranted.

The possible mechanisms of excess iodine-induced thyroid enlargement include autoimmune-mediated lymphocytic infiltration of the thyroid gland or a compensatory increase in TSH levels due to decreased thyroid hormone synthesis, leading to stimulation and proliferation of the thyroid gland (35, 36, 37). However, in this study, thyroid parenchymal changes suggestive of lymphocytic infiltrations were not observed, and TSH levels were not associated with Tvol, which may be explained by the young age and the small sample size of our participants. In this study, we could not evaluate thyroid autoantibody status, which can support the effects of autoimmunity on Tvol. Further research is needed to elucidate the mechanisms for the association between iodine excess and thyroid enlargement in prepubertal children.

Focal lesions were identified in 32.9% of 6-year-old healthy children, with thyroid cysts in 25.9%, nodules in 1.3%, and ITTs in 5.7%, without significant association with iodine status. A few pediatric studies have investigated focal lesions on thyroid US and reported a wide range of prevalence of cysts as 0.2–56.9%, nodules as 0.0–1.7%, and ITTs as 0.3–2.0%, respectively (38, 39, 40, 41, 42). The prevalence of thyroid cysts or nodules in our cohort was comparable to that in previous studies, and most of the patients with thyroid nodules showed a decrease in size, and none needed FNAB during the follow-up. Although a relationship between iodine intake and the risk of thyroid nodules or cancer has been suggested in adults (43, 44), the cross-sectional association between iodine status and focal lesions in our children was not significant, which was limited by the small sample size.

This study has some limitations. First, the cross-sectional design and small sample size limit confirm the causal relationship between iodine status and Tvol. Second, a single spot urine sample was used to assess iodine status in this study, which can be limited by intra- and interindividual variations in urine iodine excretion. However, we collected the morning urine samples after overnight fasting and also included the data of urinary Cr-adjusted values (estimated 24 h-UIE) to complement UIC. Third, we used the international reference for Tvol due to the lack of Korean pediatric reference values, which may have influenced the high prevalence of goiter in this study. As Tvol and goiter rate can be affected by genetic or environmental factors, further studies are needed to determine population-specific Tvol criteria in Korean children. Moreover, we could not evaluate the sources of iodine exposures, which limits our ability to suggest the specific dietary recommendation on the basis of our study. Further studies investigating the environmental sources of iodine excess, and its long-term consequences in childhood health are needed.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found a high prevalence of iodine excess and goiter in 6-year-old Korean children. Furthermore, as the iodine status increased from adequate to severe excess, the risk of goiter significantly increased, especially when UIC ≥ 500 μg/L. The optimal intake of iodine and cut-offs for excessive iodine intake in children need further evaluation.

Supplementary Materials

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationship that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

The EDC study was initially supported by grants from the Environmental Health Center funded by the Korean Ministry of Environment and a grant from the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2018 (18162MFDS121) and Center for Environmental Health through the Ministry of Environment. This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MEST) of the Korean government (No. 2021R1A2C1011241). The research was supported by Research Program 2017 funded by the Seoul National University College of Medicine Research Foundation (No. 800-20170140). This study was supported by a grant from the SNUH Research Fund (No. 04-2016-3020).

Author contribution statement

YJL performed the initial analyses, drafted the initial document, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. YHC, YHL, BNK, JIK, YCH, YJP, and CHS conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. SWC and YAL conceptualized and designed the study, collected data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved submission of the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Kyung-shin Lee, Jin-A Park, Ji-Young Lee, and Yumi Choi for their assistance with data collection. The biospecimens and data used in this study were provided by the biobank of Seoul National University Hospital, a member of the Korea Biobank Network.

References

- 1.Leung AM & Braverman LE. Consequences of excess iodine. Nature Reviews. Endocrinology 201410136–142. ( 10.1038/nrendo.2013.251) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmermann MB & Boelaert K. Iodine deficiency and thyroid disorders. The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology 20153286–295. ( 10.1016/S2213-8587(1470225-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Assessment of Iodine Deficiency Disorders and Monitoring Their Elimination: A Guide for Programme Managers, 3rd ed.Geneva: WHO; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Guideline: Fortification of Food-grade Salt with Iodine for the Prevention and Control of Iodine Deficiency Disorders. Geneva: WHO; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmermann MB Ito Y Hess SY Fujieda K & Molinari L. High thyroid volume in children with excess dietary iodine intakes. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 200581840–844. ( 10.1093/ajcn/81.4.840) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen W, Li X, Wu Y, Bian J, Shen J, Jiang W, Tan L, Wang X, Wang W, Pearce EN, et al. Associations between iodine intake, thyroid volume, and goiter rate in school-aged Chinese children from areas with high iodine drinking water concentrations. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2017105228–233. ( 10.3945/ajcn.116.139725) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mo Z Lou X Mao G Wang Z Zhu W Chen Z & Wang X. Larger thyroid volume and adequate iodine nutrition in Chinese schoolchildren: local normative reference values compared with WHO/IGN. International Journal of Endocrinology 201620168079704. ( 10.1155/2016/8079704) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lv S Xu D Wang Y Chong Z Du Y Jia L Zhao J & Ma J. Goitre prevalence and epidemiological features in children living in areas with mildly excessive iodine in drinking-water. British Journal of Nutrition 201411186–92. ( 10.1017/S0007114513001906) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Iodine Global Network. Global Scorecard of Iodine Nutrition in 2020 in the General Population Based on School-Age Children (SAC). Ottawa, Canada: IGN; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang MJ Hwang IT & Chung HR. Excessive iodine intake and subclinical hypothyroidism in children and adolescents aged 6–19 years: results of the sixth Korean national health and nutrition examination survey, 2013–2015. Thyroid 201828773–779. ( 10.1089/thy.2017.0507) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee YJ Cho SW Lim YH Kim BN Kim JI Hong YC Park YJ Shin CH & Lee YA. Relationship of iodine excess with thyroid function in 6-year-old children living in an iodine-replete area. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2023141099824. ( 10.3389/fendo.2023.1099824) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim KN Lim YH Shin CH Lee YA Kim BN Kim JI Hwang IG Hwang MS Suh JH & Hong YC. Cohort Profile: the Environment and Development of Children (EDC) study: a prospective children's cohort. International Journal of Epidemiology 2018471049–1050. ( 10.1093/ije/dyy070) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moon JS, Lee SY, Nam CM, Choi JM, Choi BK, Seo JW, Oh K, Jang MJ, Hwang SS, Yo MH, et al. Korean National Growth Chart: review of developmental process and an outlook. Korean Journal of Pediatrics 2007511–25. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du Bois D & Du Bois EF. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. Nutrition 19161989303–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.UNICEF. Guidance on the Monitoring of Salt Iodization Programmes and Determination of Population Iodine Status. New York: United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Remer T Neubert A & Maser-Gluth C. Anthropometry-based reference values for 24-h urinary creatinine excretion during growth and their use in endocrine and nutritional research. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 200275561–569. ( 10.1093/ajcn/75.3.561) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunn J Block U Ruf G Bos I Kunze WP & Scriba PC. Volumetric analysis of thyroid lobes by real-time ultrasound (author's transl). Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift 19811061338–1340. ( 10.1055/s-2008-1070506) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmermann MB, Hess SY, Molinari L, De Benoist B, Delange F, Braverman LE, Fujieda K, Ito Y, Jooste PL, Moosa K, et al. New reference values for thyroid volume by ultrasound in iodine-sufficient schoolchildren: a World Health Organization/Nutrition for Health and Development Iodine Deficiency Study Group Report. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 200479231–237. ( 10.1093/ajcn/79.2.231) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ha EJ, Chung SR, Na DG, Ahn HS, Chung J, Lee JY, Park JS, Yoo RE, Baek JH, Baek SM, et al. 2021 Korean thyroid imaging reporting and data system and imaging-based management of thyroid nodules: Korean society of thyroid radiology consensus statement and recommendations. Korean Journal of Radiology 2021222094–2123. ( 10.3348/kjr.2021.0713) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Metwalley KA & Farghaly HS. Subclinical hypothyroidism in children: updates for pediatricians. Annals of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism 20212680–85. ( 10.6065/apem.2040242.121) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuse Y Saito N Tsuchiya T Shishiba Y & Irie M. Smaller thyroid gland volume with high urinary iodine excretion in Japanese schoolchildren: normative reference values in an iodine-sufficient area and comparison with the WHO/ICCIDD reference. Thyroid 200717145–155. ( 10.1089/thy.2006.0209) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Filipsson Nystrom H Andersson M Berg G Eggertsen R Gramatkowski E Hansson M Hulthén L Milakovic M & Nyström E. Thyroid volume in Swedish school children: a national, stratified, population-based survey. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2010641289–1295. ( 10.1038/ejcn.2010.162) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henjum S Barikmo I Gjerlaug AK Mohamed-Lehabib A Oshaug A Strand TA & Torheim LE. Endemic goitre and excessive iodine in urine and drinking water among Saharawi refugee children. Public Health Nutrition 2010131472–1477. ( 10.1017/S1368980010000650) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zou Y Ding G Lou X Zhu W Mao G Zhou J & Mo Z. Factors influencing thyroid volume in Chinese children. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2013671138–1141. ( 10.1038/ejcn.2013.173) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki S, Midorikawa S, Fukushima T, Shimura H, Ohira T, Ohtsuru A, Abe M, Shibata Y, Yamashita S, Suzuki S, et al. Systematic determination of thyroid volume by ultrasound examination from infancy to adolescence in Japan: the Fukushima Health Management Survey. Endocrine Journal 201562261–268. ( 10.1507/endocrj.EJ14-0478) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia-Ascaso MT Ares Segura S Ros Perez P Pineiro Perez R & Alfageme Zubillaga M. Thyroid volume assessment in 3–14 year-old Spanish children from an iodine-replete area. European Thyroid Journal 20198196–201. ( 10.1159/000499103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sea JH Ji H You SK Lee JE Lee SM & Cho HH. Age-dependent reference values of the thyroid gland in pediatric population; from routine computed tomography data. Clinical Imaging 20195688–92. ( 10.1016/j.clinimag.2019.04.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Angelis S, Bagnasco M, Moleti M, Regalbuto C, Tonacchera M, Vermiglio F, Medda E, Rotondi D, Di Cosmo C, Dimida A, et al. Obesity and monitoring iodine nutritional status in schoolchildren: is body mass index a factor to consider? Thyroid 202131829–840. ( 10.1089/thy.2020.0189) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heo YJ & Kim HS. Ambient air pollution and endocrinologic disorders in childhood. Annals of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism 202126158–170. ( 10.6065/apem.2142132.066) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen W Zhang Q Wu Y Wang W Wang X Pearce EN Tan L Shen J & Zhang W. Shift of reference values for thyroid volume by ultrasound in 8- to 13-year-olds with sufficient iodine intake in China. Thyroid 201929405–411. ( 10.1089/thy.2018.0412) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zou Y Lou X Ding G Mo Z Zhu W Mao G & Zhou J. An assessment of iodine nutritional status and thyroid hormone levels in children aged 8–10 years living in Zhejiang Province, China: a cross-sectional study. European Journal of Pediatrics 2014173929–934. ( 10.1007/s00431-014-2273-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sang Z Chen W Shen J Tan L Zhao N Liu H Wen S Wei W Zhang G & Zhang W. Long-term exposure to excessive iodine from water is associated with thyroid dysfunction in children. Journal of Nutrition 20131432038–2043. ( 10.3945/jn.113.179135) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao N Zhou C Xie J Li X Zhou Q Chen J & Zhou S. Assessment of the iodine nutritional status among Chinese school-aged children. Endocrine Connections 20209379–386. ( 10.1530/EC-19-0568) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Calsolaro V Pasqualetti G Niccolai F Caraccio N & Monzani F. Thyroid disrupting chemicals. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017182583. ( 10.3390/ijms18122583) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farebrother J Zimmermann MB & Andersson M. Excess iodine intake: sources, assessment, and effects on thyroid function. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2019144644–65. ( 10.1111/nyas.14041) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laurberg P Cerqueira C Ovesen L Rasmussen LB Perrild H Andersen S Pedersen IB & Carle A. Iodine intake as a determinant of thyroid disorders in populations. Best Practice and Research. Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 20102413–27. ( 10.1016/j.beem.2009.08.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalarani IB & Veerabathiran R. Impact of iodine intake on the pathogenesis of autoimmune thyroid disease in children and adults. Annals of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism 202227256–264. ( 10.6065/apem.2244186.093) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duarte GC Tomimori EK de Camargo RY Catarino RM Ferreira JE Knobel M & Medeiros-Neto G. Excessive iodine intake and ultrasonographic thyroid abnormalities in schoolchildren. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism 200922327–334. ( 10.1515/jpem.2009.22.4.327) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ishigaki K Namba H Takamura N Saiwai H Parshin V Ohashi T Kanematsu T & Yamashita S. Urinary iodine levels and thyroid diseases in children; comparison between Nagasaki and Chernobyl. Endocrine Journal 200148591–595. ( 10.1507/endocrj.48.591) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayashida N, Imaizumi M, Shimura H, Okubo N, Asari Y, Nigawara T, Midorikawa S, Kotani K, Nakaji S, Otsuru A, et al. Thyroid ultrasound findings in children from three Japanese prefectures: Aomori, Yamanashi and Nagasaki. PLoS One 20138e83220. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0083220) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 41.Avula S Daneman A Navarro OM Moineddin R Urbach S & Daneman D. Incidental thyroid abnormalities identified on neck US for non-thyroid disorders. Pediatric Radiology 2010401774–1780. ( 10.1007/s00247-010-1684-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nam BD Chang Y-W Hong SS Hwang J-Y Lim HK Lee JH & Lee DH. Characteristic sonographic and follow up features of thyroid nodules according to childhood age groups. Journal of the Korean Society of Radiology 201675126–132. ( 10.3348/jksr.2016.75.2.126) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zimmermann MB & Galetti V. Iodine intake as a risk factor for thyroid cancer: a comprehensive review of animal and human studies. Thyroid Research 201588. ( 10.1186/s13044-015-0020-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cao LZ Peng XD Xie JP Yang FH Wen HL & Li S. The relationship between iodine intake and the risk of thyroid cancer: a meta-analysis. Medicine 201796e6734. ( 10.1097/MD.0000000000006734) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a