Abstract

The galactose operon of Streptococcus mutans is transcriptionally regulated by a repressor protein (GalR) encoded by the galR gene, which is divergently oriented from the structural genes of the gal operon. To study the regulatory function of GalR, we partially purified the protein and examined its DNA binding activity by gel mobility shift and DNase I footprinting experiments. The protein specifically bound to the galR-galK intergenic region at an operator sequence, the position of which would suggest that GalR plays a role in the regulation of the gal operon as well as autoregulation. To further examine this hypothesis, transcriptional start sites of the gal operon and the galR gene were determined. Primer extension analysis showed that both promoters overlap the operator, indicating that GalR most likely represses transcription initiation of both promoters. Finally, the results from in vitro binding experiments with potential effector molecules suggest that galactose is a true intracellular inducer of the galactose operon.

Streptococcus mutans is the major causative agent of dental caries, and sugar metabolism is known to play an important role in causing this disease. S. mutans possesses different mechanisms for the utilization of sugars, and recently the operon involved in galactose metabolism via the Leloir pathway has been cloned and characterized (2). The transcription of the structural genes (galK, galT and galE) comprising the gal operon is repressed in the absence of galactose and is subject to catabolite repression in the presence of glucose (2). The galR gene of S. mutans has been shown to specify a repressor of the galactose operon; unlike in Escherichia coli and Streptomyces lividans, this gene is located immediately upstream and is divergently oriented from the structural genes (see Fig. 8) (2). Computer analysis has shown that GalR belongs to the GalR-LacI family of transcriptional regulators that bind as a dimer to the specific DNA sequence (16, 26, 27).

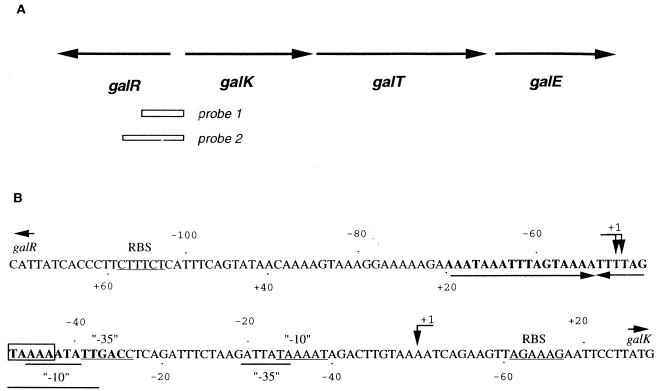

FIG. 8.

S. mutans gal operon and nucleotide sequence of the galR-galK intergenic region. (A) galR, galactose repressor gene; galK, galactokinase gene; galT, galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase gene; galE, UDP glucose-4-epimerase gene. Arrows show orientation of transcription of the genes; open boxes represent probes used in gel mobility shift (probe 1) and footprinting (probe 2) assays. (B) The sequence protected by GalR from DNase I digestion is in boldface; putative promoters are underlined. Predictions for −10 and −35 promoter regions were based on the gram-positive organism promoter consensus sequence (9) and/or the promoter consensus sequence for the genus Streptococcus (17). The operator region mutated by site-directed mutagenesis is boxed; the region of dyad symmetry is indicated by horizontal arrows. RBS stands for ribosome binding site; vertical arrows indicate the transcriptional start sites. Numbers below and above the sequence refer to galR and galK genes, respectively.

To study the regulation of the S. mutans gal operon at the molecular level, GalR was partially purified and used in gel mobility shift and footprinting assays. In this report, we demonstrate that transcriptional regulation of the gal operon of S. mutans is mediated by a protein product of the galR gene (GalR). In the absence of galactose, GalR binds to a palindromic sequence which overlaps the galR and gal operon promoters and probably represses their initiation of transcription.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth conditions.

E. coli strains were grown in LB or M9 medium (20) supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; and rifampin, 200 μg/ml). S. mutans strains were grown in semidefined medium (18, 24) supplemented with either galactose or glucose and kanamycin (400 μg/ml) when necessary.

DNA manipulations and sequencing.

Protocols for plasmid extraction, digestion of DNA with restriction enzymes, gel purification of DNA fragments, DNA ligation, and agarose and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis have been described elsewhere (20). Sequencing reactions were done with a Sequenase version 2.0 kit (U.S. Biochemical) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Overexpression of galR.

Plasmid pSF813, used for overexpression of galR, was constructed by cloning a 1.8-kb HindIII-EcoRI fragment, which contains the galR gene and its own translation signals (2), into the pT7T318U expression vector (Pharmacia), thereby positioning galR under the control of the T7 promoter. A second plasmid, pGP1-2, was used as a source of the T7 RNA polymerase gene, whose expression is under the control of a temperature-sensitive λ repressor cI857) (22).

The E. coli expression strain (JM109 transformed with pSF813 and pGP1-2) and control strain (JM109 transformed with pT7T318U and pGP1-2) were grown to an A600 of 0.5 to 0.6 in 1 ml of M9 medium supplemented with ampicillin, kanamycin, 0.05 mM thiamine and 0.1% Casamino Acids. The culture was then incubated at 42°C for 30 min, then rifampin was added, and incubation continued for 20 min at 42°C. Cells were pelleted, washed twice with M9 medium, resuspended in labeling medium (M9 supplemented with ampicillin, kanamycin, 0.05 mM thiamine, and rifampin), and incubated at 42°C for 10 min. After addition of 20 μCi of l-[35S]methionine-cysteine (ICN), the cells were incubated for 2 h at 30°C, pelleted, washed twice with Tris-EDTA, and resuspended in loading buffer (0.08 M Tris [pH 6.8], 0.1 M dithiothreitol, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 10% glycerol, 0.1 mg of bromphenol blue per ml). The cells were then denatured at 95°C for 5 min, and the proteins were analyzed on an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel.

Partial purification of GalR.

E. coli JT34 [F− Strr his relA1 ΔgalR(B-C)::Cmr] (25), transformed with plasmids pGP1-2 and pSF813, was grown in 500 ml of LB medium supplemented with ampicillin (200 μg/ml) and kanamycin to an A600 of 0.5. galR was induced by increasing the culture temperature to 42°C for 45 min, and the cells were grown at 37°C for another 4 h in the presence of rifampin. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed two times in buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]), suspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, DNase I [1 μg/ml], RNase I [1 μg/ml]) (15), and lysed by use of a French press (100 MPa). Cell debris was removed by consecutive centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 10 min followed by 60 min at 100,000 × g. The supernatant was removed, and approximately 15 mg of total proteins was loaded on a 9-ml heparin column (Affi-Gel heparin gel; Bio-Rad) that had been equilibrated and washed with buffer A. Proteins were eluted with a 0.2 to 1.2 M NaCl gradient made in buffer A. The 1 M NaCl fraction, which contained most of the GalR protein, was concentrated by centrifugation in Centriprep 10 and Centricon 10 (Amicon) concentrators. The control protein extract from JT34 transformed with vectors only (pT7T318U and pGP1-2) was isolated by the same procedure. The protein concentration was determined by using a Pierce protein determination kit with bovine serum albumin as a standard. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of GalR was determined by the Molecular Biology Resource Facility of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center.

Gel mobility shift assay.

The probe used for the gel mobility shift assay was prepared by digesting plasmid pSF806 (2) with EcoRI and XbaI to give a 200-bp fragment. This fragment was separated on a 5% polyacrylamide gel, electroeluted, and end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol) and T4 kinase after dephosphorylation (20). The radiolabeled probe (5 to 10 ng) was mixed with different concentrations of partially purified GalR (32.5 to 227.5 ng) in binding buffer [25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 50 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 50 mM KCl, 25 μg of poly(dI-dC)–poly(dI-dC) per ml] in a total volume of 20 μl. Sugars were added to the reaction mixture 5 min before radiolabeled probe was added, at a final concentration of 0.5% (28 mM), when indicated. Incubation was carried out for 15 min at room temperature. The DNA-protein complex was separated from the unbound DNA fragment on a 5% native polyacrylamide gel, using 1× Tris-borate-EDTA (20) as the electrophoresis buffer. d-(+)-Galactose (SigmaUltra; catalog no. G-6404) and other sugars were purchased from Sigma.

DNase I footprinting analysis.

For DNase I footprinting, the 468-bp EcoRI-PstI DNA fragment from pSF806 (2) was electroeluted from a 5% polyacrylamide gel and labeled at the 3′ end with [α-32P]dATP (800 Ci/mmol) via the large fragment of DNA polymerase I (20). The reaction mixture contained the same components as the mixture used for the gel mobility shift assay, except that the concentrations of protein extract were 0.5 to 3 μg and the concentrations of the DNA fragments were 50 to 80 ng in a total volume of 40 μl. Incubation was carried out for 45 min at room temperature. This was followed by digestion with 20 mU of DNase I (Sigma) in an appropriate buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 500 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2) for 2 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped with 20 μl of 25 mM EDTA, ethanol precipitated, and resuspended in a sequencing loading buffer. DNA fragments were separated on a 6% sequencing gel.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the GalR-binding sequence was performed by using an Altered Sites II in vitro mutagenesis system kit (Promega) as recommended by the manufacturer. The mutagenic oligonucleotide was 5′-ATCTGAGGTCAATATGGATCCTAAAATTTTACTAA-3′ (positions −28 to −62 relative to the gal operon transcriptional start site). The control mutagenic oligonucleotide was 5′-GATAATGGCTACATTAGGATCCATTGCAAAATTAGC-3′ (positions −115 to −150 relative to the gal operon transcriptional start site). The underlined sequences of five nucleotides replaced the wild-type sequences (TAAAA and TCTTT, respectively). Fragments that carry the altered operator sequences were purified and end labeled as described above.

RNA isolation.

Total cellular RNA was isolated from an S. mutans LT11 (23) exponential-phase culture by the hot acidic phenol method (14), with modifications. Lysis of the cells was accomplished by a Mini Beadbeater (Biospec Products, Inc.) using zirconia-silica beads (0.1-mm diameter). The concentration of RNA was determined by A260 measurements, and the quality of RNA was analyzed on a conventional Tris-borate-ethidium bromide agarose gel (12).

Primer extension.

To determine the transcriptional start site of the galR and gal operons, oligonucleotides 5′-CATCTTTGTTCAATACTC (positions +127 to +144 relative to the galR transcriptional start site) and 5′-GTAGCGTCTGCTTCTCTTCC (positions +68 to +88 relative to the gal operon transcriptional start site), respectively, were used. Primer extension analysis was performed by using avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase as described previously (11).

RESULTS

Overproduction and partial purification of GalR.

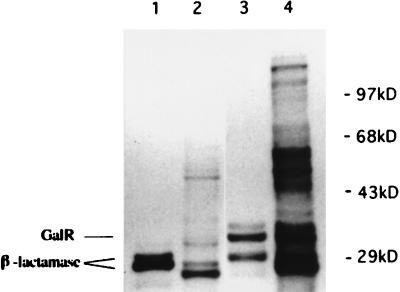

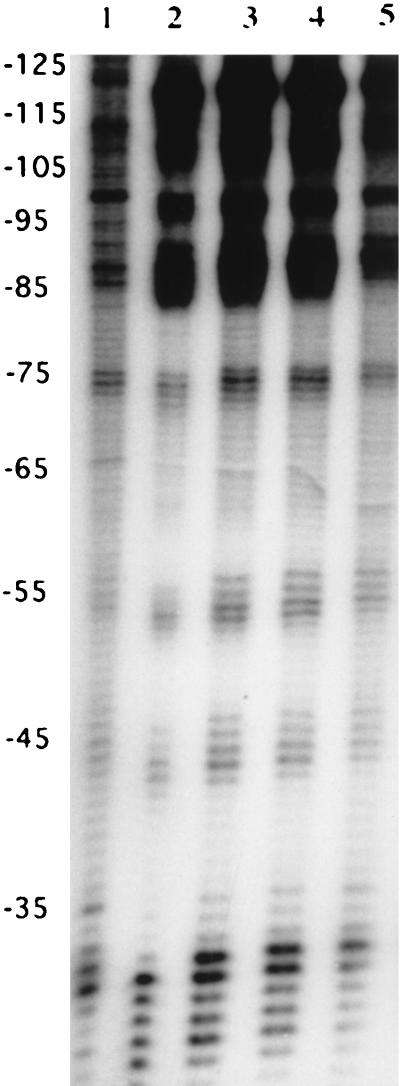

Because most cellular regulatory proteins are present at a relatively low level, we have overexpressed the galR gene in E. coli. galR was placed under the control of the T7 promoter of the pT7T318U vector, forming pSF813. This plasmid was then introduced into a strain containing a second plasmid, pGP1-2, that carries the T7 RNA polymerase gene under the control of a temperature-sensitive λ repressor (22). Expression of galR in a strain containing both plasmids was activated by increasing the temperature to 42°C, resulting in derepression of the T7 RNA polymerase and consequently transcription and translation of the galR as well as β-lactamase, since there are no terminators on the pT7T318U vector. The same E. coli host transformed with pT7T318U and pGP1-2 was used as a control, and a comparable experiment was performed. Rifampin was used to inhibit the E. coli RNA polymerase of both strains. The proteins observed by autoradiography of an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, after induction and labeling with [35S]methionine, are shown in Fig. 1. Two proteins of similar molecular weight (MW) were radioactively labeled in the induced control strain (Fig. 1, lane 1), whereas two different-MW proteins were visible in the induced galR expression strain (Fig. 1, lane 3). A 29-kDa protein is β-lactamase precursor, whereas a 27-kDa protein is processed β-lactamase (22). A 37-kDa protein was present in the induced galR expression strain only (Fig. 1, lane 3), and it migrated with a mobility which corresponded to that predicted from the deduced amino acid sequence of GalR (2).

FIG. 1.

Autoradiograph showing overexpression of galR in E. coli. Lane 1, control protein extract of E. coli cells harboring pT7T318U and pGP1-2 (the culture was induced at 42°C); lane 2, control protein extract of E. coli cells harboring pT7T318U and pGP1-2 (the culture was not induced [30°C]); lane 3, protein extracts of E. coli cells harboring expression plasmid pSF813 (galR in pT7T318U) and pGP1-2 (the culture was induced at 42°C); lane 4, protein extracts of E. coli cells harboring expression plasmid pSF813 (galR in pT7T318U) and pGP1-2 (the culture was not induced [30°C]). Rifampin was added in all samples except the one in lane 4. Since a prestained protein MW standard was used, positions of the bands were marked on the autoradiograph according to their positions on the polyacrylamide gel.

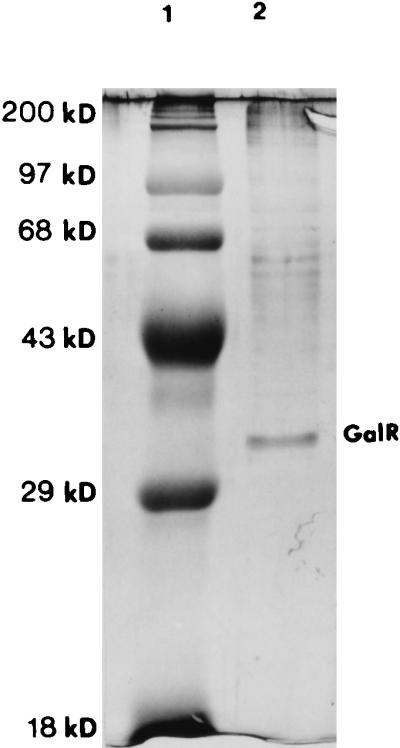

Previous experiments had shown that GalR from S. mutans could be successfully produced in E. coli; thus, it was decided to overexpress and partially purify the product of galR starting with a 500-ml culture of the galR expression strain (as described in Materials and Methods). Many DNA-binding proteins show affinity for heparin-agarose, and in this study we used heparin chromatography for partial purification of GalR. Fractions of the protein extract eluted from a heparin-agarose column with an NaCl gradient were analyzed on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel. The major band visible in the 1 M NaCl fraction, which migrated as a 37-kDa protein (Fig. 2), was sequenced. Nine amino acids of this protein, obtained by N-terminal protein sequencing, were identical to the deduced amino acid sequence of GalR. This partially purified GalR was then used for in vitro DNA binding experiments.

FIG. 2.

Partially purified GalR. A 1 M NaCl protein fraction was analyzed on an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel after chromatography on a heparin-agarose column. Proteins in the gel were detected with Coomassie blue staining (20). Lane 1, MW protein standard; lane 2, partially purified GalR protein extract.

Specific binding of GalR to the gal operon promoter region.

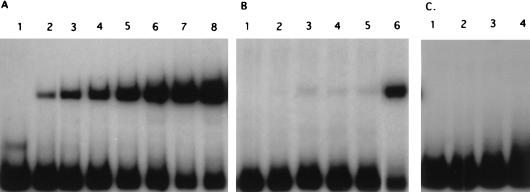

The DNA binding activity of the partially purified GalR was determined in a gel mobility shift assay. As shown in Fig. 3A, the mobility of the specific 200-bp DNA fragment that contained the galR-galK intergenic region was shifted upon addition of the partially purified GalR. The fraction of retarded DNA fragments increased as the protein concentration increased. Only one shifted band was observed in the autoradiograph if the protein concentration added to the reaction mixture was in the range of 32.5 to 227.5 ng/reaction, indicating that one DNA-protein complex was formed.

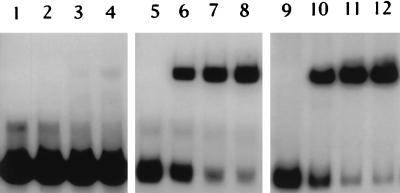

FIG. 3.

Specific binding of GalR to the galR-galK intergenic region. Autoradiographs of a gel mobility shift assay on a 5% polyacrylamide gel are shown. Approximately 10 ng of the specific (200-bp) end-labeled DNA fragment that contained galR and gal operon promoters and different, partially purified protein extracts were used in each assay. (A) Titration gel mobility shift assay using partially purified GalR protein extract. Concentrations of the protein extract: lane 1, 0 ng; lane 2, 32.5 ng; lane 3, 65 ng; lane 4, 97.5 ng; lane 5, 130 ng; lane 6, 162.5 ng; lane 7, 195 ng; lane 8, 227.5 ng. (B) Competition gel mobility shift assay. The concentration of the identical but unlabeled specific DNA fragment (added 5 min before labeled DNA) was approximately 20 ng per reaction. The unlabeled fragment was not added in lane 6. Concentrations of partially purified GalR protein extract: lane 1, 0 ng; lane 2, 32.5 ng; lane 3, 97.5 ng; lane 4, 162.5 ng; lane 5, 227.5 ng; lane 6, 97.5 ng. (C) Control gel mobility shift assay using control protein extract partially purified from the E. coli host carrying the vector without a galR insert. Concentrations of the protein extract: lane 1, 0 ng; lane 2, 97.5 ng; lane 3, 162.5 ng; lane 4, 227.5 ng.

To further analyze the binding of the GalR protein extract, competition experiments were performed. Binding was almost completely abolished if a specific competitor (20 ng of unlabeled identical DNA fragment) was added to the reaction mixture 5 min before addition of labeled DNA (10 ng) (Fig. 3B), whereas an excess amount (0.5 to 1 μg) of a nonspecific competitor, poly(dI-dC)–poly(dI-dC), that was routinely used in gel mobility shift experiments had no effect on binding. Furthermore, when the gel mobility shift assay was performed with a protein extract prepared from the culture that contained a vector with no insert, a specific DNA-protein complex was not formed (Fig. 3C), suggesting specific binding of GalR to the galR-galK intergenic region. GalR binding was not observed with DNA fragments either upstream (0.4 kb) or downstream (0.25 kb) of the specific DNA fragment or with the fragment carrying the galT-galE intergenic region (results not shown).

Effect of d-galactose on repressor binding.

To determine if different sugars play a role in GalR binding to the specific DNA fragment, we performed gel mobility shift experiments using different sugars in each reaction mixture (galactose, glucose, maltose, fructose, melibiose, raffinose, lactose, glucose-1,6-biphosphate, fructose-1,6-biphosphate, and all intermediates of the Leloir pathway for galactose metabolism [galactose-1-phosphate, UDP galactose, UDP glucose, glucose-1-phosphate, and glucose-6-phosphate]). Addition of d-galactose, the inducer of the gal operon (2), in the reaction mixture almost completely abolished binding of partially purified GalR to the specific DNA fragment (Fig. 4, lanes 1 to 4), suggesting that d-galactose is a true intracellular inducer of the gal operon. None of the other sugars had an effect on GalR binding.

FIG. 4.

Autoradiograph of a gel mobility shift assay showing the effect of d-galactose on repressor binding. Specific end-labeled DNA fragment (approximately 10 ng) was mixed with different amounts of the GalR protein extract, with (lanes 1 to 4) or without (lanes 5 to 9) d-galactose (which was added 5 min before the labeled probe in a final concentration of 0.5%). Free DNA fragments were separated from the DNA-protein complex on a 5% polyacrylamide gel. Concentrations of partially purified GalR: lanes 1 and 6, 250 ng; lanes 2 and 7, 180 ng; lanes 3 and 8, 110 ng; lanes 4 and 9, 40 ng; lane 5, 0 ng.

Identification of repressor-binding region.

The location of the repressor-binding site was identified by a DNase I footprinting assay using the partially purified GalR and an end-labeled 468-bp DNA fragment that contained the galR-galK intergenic region and 5′ end of the galR gene. The protected region extended from −35 to −70 starting from the transcriptional start site of the first structural gene (galK) of the gal operon (Fig. 5). Several hypersensitive sites, between positions −90 and −120, were visible on the autoradiograph upon addition of the protein extract and DNase I digestion, suggesting a major conformational change of substrate DNA upon repressor binding.

FIG. 5.

DNase I footprinting of GalR. The DNA fragments were separated on a 6.5% sequencing gel. Concentrations of partially purified GalR: lane 1, 0 μg; lane 2, 3 μg; lane 3, 1.5 μg; lane 4, 1 μg; lane 5, 0.75 μg. The amount of the specific, 468-bp 3′-labeled DNA fragment was approximately 50 ng/reaction. Nucleotide positions are given on the left relative to the galK transcriptional start site.

It is known that DNA-binding proteins often bind to regions in which the nucleotide sequence displays dyad symmetry. Sequence analysis of the protected region revealed an imperfect palindrome (see Fig. 8). To further examine the same region, a 5-bp change (TAAAA to GATCC; positions −43 to −47) in the right half of the palindrome was created by site-directed mutagenesis. As a control, a 5-bp change (TCTTT to GATCC; positions −130 to −134) was created outside the detected palindromic sequence, and both mutations were verified by DNA sequencing. When the mutated operator was used as a probe for a gel mobility shift assay, formation of a DNA-protein complex was decreased considerably (Fig. 6, lanes 1 to 4), whereas the control mutation had no effect on DNA-protein binding (Fig. 6, lanes 5 to 8), suggesting that the detected protected region is the true operator of the gal operon.

FIG. 6.

Effects of mutations in the operator region on formation of the DNA-protein complex. The DNA fragment with mutations in the operator region was used for gel mobility shift assays in lanes 1 to 4; the DNA fragment that carries mutations outside of the operator region was used for gel mobility shift assays in lanes 5 to 8; nonmutated DNA fragment was used for gel mobility shift assays in lanes 9 to 12. Concentrations of the partially purified GalR: lanes 1, 5, and 9, 0 ng; lanes 2, 6, and 10, 130 ng; lanes 3, 7, and 11, 162.5 ng; lanes 4, 8, and 12, 195 ng.

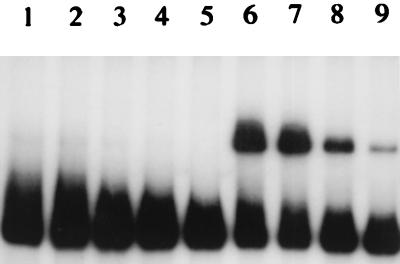

Determination of the gal operon and galR transcriptional start sites.

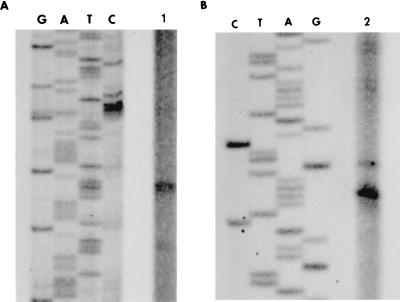

The orientation of the regulatory and structural genes of the gal operon suggested that their transcription originated within the galR-galK intergenic region. Several attempts to detect a galR transcriptional start site have failed, most likely because of the low level of specific mRNA present. To enrich the amount of mRNA, galR was cloned into shuttle vector pDL276 (7), and S. mutans LT11 was transformed with this construct. Total RNA was then isolated, and a primer extension experiment was performed. Two extension products, with 5′ ends mapping at a location 68 and 69 nucleotides upstream of the galR translational start site, were detected (Fig. 7A), and so the exact transcription initiation site remains conjectural. No product was detected after primer extension analysis performed with total RNA isolated from S. mutans LT11 carrying a vector without the insert (data not shown). The galR transcriptional start site revealed that the galR promoter overlaps the gal operon promoter and that its −10 region overlaps the operator (Fig. 8).To determine a transcriptional start point of the gal operon structural genes, total RNA was isolated from S. mutans LT11 cultures grown in semidefined medium supplemented with galactose, and primer extension analysis was performed with a specific primer. The 5′ end of the mRNA for the gal operon was located 25 nucleotides upstream of the galK translational start site (Fig. 7B), in agreement with the location of the promoter predicted from the nucleotide sequence. The −35 region of this promoter overlaps with the operator sequence (Fig. 8).

FIG. 7.

Primer extension analysis of galR and gal operon transcription in S. mutans. Total RNA from S. mutans LT11 cells grown in semidefined medium supplemented with galactose was isolated, and approximately 20 μg of total RNA was used for the primer extension reactions. Sequencing reactions were prepared with the same primer used for primer extension analysis. (A) Lane 1, determination of the 5′ end of the galR transcript; (B) lane 2, determination of the 5′ end of the gal operon transcript.

DISCUSSION

Sequence analysis of GalR has shown that this protein possesses a helix-turn-helix motif at its N terminus, which is typical for DNA-binding proteins (16, 26, 27). Additionally, it has been shown that mutation in galR leads to constitutive expression of galK, the first structural gene of the S. mutans gal operon, which suggests that GalR is a repressor of the galactose operon (2). To verify that GalR indeed regulates the genes responsible for metabolism of galactose via protein-DNA interaction, GalR was overproduced in E. coli, partially purified, and used in an in vitro binding study. Gel mobility shift, DNase I footprinting, and site-directed mutagenesis analyses showed that GalR binds to the galR-galK intergenic region at a position that is equidistant from the two genes. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the repressor-protected region revealed that it spans an imperfect inverted repeat. The dyad symmetry of the repressor-protected region and the presence of a dimerization region at the C-terminal part of the GalR amino acid sequence suggests that this repressor binds to its cis-active sequence as a dimer, where each monomer interacts with one half of the palindrome. Furthermore, site-specific mutagenesis of the right half of the operator considerably decreased but did not completely abolish binding of GalR to its operator in vitro, which might mean that the GalR dimer was still able to partially interact with the nonmutated half of the operator through one monomer.

Our previous results showed that the most effective inducer of the gal operon was galactose itself (2), although a high level of induction was also obtained with raffinose, a galactose-containing carbohydrate. The uptake of raffinose eventually results in an increase in galactose concentration in the cell, since the galactose moiety of raffinose is released intracellularly by α-galactosidase. To determine whether galactose is a bona fide intracellular inducer, gel mobility shift experiments were repeated in the presence of different sugars. Our observation that galactose abolishes binding of GalR, whereas none of the other tested sugars, including intermediates of the Leloir pathway, had no effect on DNA-protein interaction, strongly suggests that galactose is the true intracellular inducer of the gal operon.

Primer extension analysis of the galR and the gal operon transcriptional start site has shown that there are two divergent, overlapping promoters in the galR-galK intergenic region. One of these promoters is responsible for galR transcription, whereas the other enables transcription of the structural genes of the operon. As shown in Fig. 8, the −10 promoter region of galR and part of the −35 region of the gal operon promoter overlap the operator, strongly suggesting that GalR, if bound to this operator, interferes with transcription from both promoters. Previous analyses have shown that GalR negatively regulates expression of the gal operon. It has also been shown that several repressors negatively regulate their own expression (10, 19, 21, 29). To study further the nature of GalR autoregulation, primer extension experiments were done under maximal inducing and repressing conditions; the same products were detected, although the level of transcription of galR was higher in galactose-grown cells. These results, as well as the overlapping position of the gal operator and galR promoter, indicate that GalR probably negatively regulates its own synthesis. To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating negative autoregulation of galR transcription. Our results also suggest that there is a basal level of gal operon transcription when glucose is present in the growth medium, which correlates with previous results of galactokinase assays (2). It has been shown that UDP galactose 4-epimerase (GalE) is required for glycosylation and cell wall synthesis in E. coli (1, 6). Even if galactose is not present in the growth medium, UDP galactose is generated from UDP glucose by GalE, which is necessary for galactosyl lipid synthesis. In order to fulfill the same requirement, galE of S. lividans must be transcribed from its constitutive promoter located immediately upstream of the gene (8). Analysis of the chemical composition of S. mutans purified cell walls revealed that galactose is one of the components (28), and GalE might also be necessary for cell wall synthesis in this organism. Since we did not observe promoter activity in the galT-galE intergenic region under tested conditions (data not shown), the basal level of transcription from the gal operon promoter might be necessary to fulfill a requirement for constitutive galE expression.

Our results indicate that the structural organization and regulation of the gal operon of S. mutans are different from those in E. coli and S. lividans. The genes comprising the E. coli gal operon are transcribed from two overlapping promoters (P1 and P2) which are negatively regulated by the galactose repressor (GalR) (1, 6). GalR binds as a dimer to two operator sites located outside the promoters. Repression of the gal operon promoters requires the presence of histone-like HU protein, which mediates loop formation through contact of the GalR dimers bound to the operators (3, 4, 13). A similar situation is observed in S. lividans, where the genes responsible for galactose utilization, as in E. coli, are organized in a polycistronic manner, and two identified promoters (galP1 and galP2) have been shown to be independently regulated (8). galP1, which is located immediately upstream of the operon, is induced in the presence of galactose, whereas galP2, the internal promoter located upstream of the galE gene, is responsible for constitutive expression of the galE and galT genes. Transcription of the S. mutans gal operon is driven by a single promoter located upstream of galK, the first structural gene. This promoter sequence overlaps a single operator, and evidence presented here indicates that binding of the S. mutans GalR to the operator represses RNA polymerase binding to the gal operon promoter, although it cannot be ruled out that both GalR and RNA polymerase are able to bind simultaneously. GalR would then inhibit a step of initiation subsequent to polymerase binding through GalR-RNA polymerase interactions. Furthermore, the same operator overlaps the galR promoter, which, unlike the case for E. coli, suggests dual function of the GalR: regulation of the gal operon transcription as well as autoregulation.

These studies enabled us to formulate a simple model for regulation of the galactose operon by the gal repressor. When galactose is not present in the growth medium, binding of GalR to its operator represses initiation of transcription from both promoters. Addition of galactose inactivates the repressor, allowing transcription to proceed. It has been known that steric hindrance could occur between RNA polymerase molecules attempting to bind simultaneously to the overlapping promoters (5). This competition could reduce the activity of one promoter (in this case probably the galR promoter) and increase the activity of the other. Indeed, our results showed that the gal operon promoter is about 10 times stronger than the galR promoter (unpublished data). This type of control might be necessary for expression of the gal operon genes in order for their products to be present in a fixed molar ratio. When the concentration of galactose decreases, GalR molecules are able to bind their operator again. This model does not exclude the possibility that another protein directly or indirectly affects regulation of the gal operon. It has been shown recently that, besides the Gal repressor, the histone-like protein HU is required for transcriptional regulation of the gal operon in E. coli (3, 4, 13). Whether such a protein is also required for transcriptional regulation of the S. mutans gal operon remains to be determined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This investigation was supported by USPHS research grant DE08191 from the National Institutes of Health.

We acknowledge W. M. McShan and R. E. McLaughlin for helpful discussions and review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adhya S. The galactose operon. In: Neidhardt F C, Ingraham L J, Low K B, Magasanik B, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1987. pp. 1503–1512. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ajdic D, Sutcliffe I C, Russell R R B, Ferretti J J. Organization and nucleotide sequence of the Streptococcus mutans galactose operon. Gene. 1996;180:137–144. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00434-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aki T, Adhya S. Repressor induced site-specific binding of HU for transcriptional regulation. EMBO J. 1997;16:3666–3674. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aki T, Choy H E, Adhya S. Histone-like protein HU as a specific transcriptional regulator: co-factor role in repression of gal transcription by GAL repressor. Genes Cells. 1996;1:179–188. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.d01-236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck C F, Warren R A J. Divergent promoters, a common form of gene organization. Microbiol Rev. 1988;52:318–326. doi: 10.1128/mr.52.3.318-326.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Crombrugghe B, Pastan I. Cyclic AMP, the cyclic AMP receptor protein, and the dual control of the galactose operon. In: Miller J H, Reznikoff W S, editors. The operon. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1980. pp. 303–324. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunny G M, Lee L N, LeBlanc D J. Improved electroporation and cloning vector system for gram-positive bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1194–1201. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.4.1194-1201.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fornwald J A, Schmidt F J, Adams C W, Rosenberg M, Brawner A M. Two promoters, one inducible and one constitutive, control transcription of the Streptomyces lividans galactose operon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2130–2134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graves M C, Rabinowitz J C. In vivo and in vitro transcription of the Clostridium pasteurianum ferredoxin gene. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:11409–11415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunsalus R P, Yanofsky C. Nucleotide sequence and expression of E. coli trpR, the structural gene for the trp aporepressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:7117–7121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivanisevic R, Milic M, Ajdic D, Rakonjac J, Savic D J. Nucleotide sequence, mutational analysis, transcriptional start site, and product analysis of nov, the gene which affects Escherichia coli K-12 resistance to the gyrase inhibitor novobiocin. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1766–1771. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.7.1766-1771.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lunsford R D. Recovery of RNA from oral streptococci. BioTechniques. 1995;18:412–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyubchenko Y L, Shlyakhtenko L S, Aki T, Adhya S. Atomic force microscopic demonstration of DNA looping by GalR and HU. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:873–876. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.4.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magni C, Marini P, de Mendoza D. Extraction of RNA from Gram-positive bacteria. BioTechniques. 1995;19:882–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohr C D, Hibler N S, Deretic V. AlgR, a response regulator controlling mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, binds to the FUS sites of the algD promoter located unusually far upstream from the mRNA start site. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5136–5143. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.16.5136-5143.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen C C, Saier M H. Phylogenetic, structural and functional analyses of the LacI-GalR family of bacterial transcription factors. FEBS Lett. 1995;377:98–102. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01344-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Podbielski A, Peterson J A, Cleary P. Surface protein-CAT reporter fusions demonstrate differential gene expression in the vir regulon of S. pyogenes. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2253–2265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Russell R R B. Purification of Streptococcus mutans glucosyltransferase by polyethylene glycol precipitation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1979;6:197–199. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saint-Girons I, Duchange N, Cohen G N, Zakin M M. Structure and autoregulation of the metJ regulatory gene in E. coli. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:14282–14285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schell M A. Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:597–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabor S, Richardson C C. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1074–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tao L, MacAlister T J, Tanzer J M. Transformation efficiency of EMS-induced mutants of S. mutans of altered cell shape. J Dent Res. 1993;72:1032–1039. doi: 10.1177/00220345930720060701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terleckyj B, Willett N P, Shockman G D. Growth of several cariogenic strains of oral streptococci in a chemically defined medium. Infect Immun. 1975;11:649–655. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.4.649-655.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tokeson G P, Garger E, Adhya S. Further inducibility of a constitutive system: ultrainduction of the gal operon. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2319–2327. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.7.2319-2327.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weickert M J, Adhya S. A family of bacterial regulators homologous to gal and lac repressors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15869–15874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weickert M J, Adhya S. Isorepressor of the gal regulon in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:69–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wetherell J J R, Bleiweis A S. Antigens of Streptococcus mutans: isolation of a serotype-specific and a cross-reactive antigen from walls of strain V-100 (serotype e) Infect Immun. 1978;19:160–169. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.1.160-169.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson R L, Stauffer G V. DNA sequence and characterization of GcvA, a LysR family regulatory protein for the Escherichia coli glycine cleavage enzyme system. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2862–2868. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2862-2868.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]