Abstract

Two differentially regulated catalase genes have been identified in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. The catA gene belongs to a class whose transcripts are specifically induced during asexual sporulation (conidiation) and encodes a catalase accumulated in conidia. Using a developmental mutant affected in the brlA gene, which is unable to form conidia but capable of producing sexual spores (ascospores), we demonstrated that the catA mRNA accumulated during induction of conidiation but did not produce CatA protein. In contrast, high levels of catalase A activity were detected in the ascospores produced by this mutant, indicating that the catA gene is posttranscriptionally regulated. The same type of regulation was observed for a catA::lacZ translational gene fusion, suggesting that the catA message 5′ untranslated region could be involved in translational control during development. In a wild-type strain, β-galactosidase activity driven from the catA::lacZ gene fusion was low in hyphae and increased 50-fold during conidiation and 620-fold in isolated conidia. Consistent with this finding spatial expression of the reporter gene was restricted to metulae, phialides, and conidia. Conidium-associated expression was maintained in a stuA mutant, in which the conidiophore cell pattern is severely deranged. catA mRNA accumulation was also observed when vegetative mycelia was subject to oxidative, osmotic, and nitrogen or carbon starvation stress. Nevertheless, catalase A activity was restricted to the conidia produced under nutrient starvation. Our results provide support for a model in which translation of the catA message, accumulated during conidiation or in response to different types of stress, is linked to the morphogenetic processes involved in asexual and sexual spore formation. Our findings also indicate that brlA-independent mechanisms regulate the expression of genes encoding spore-specific products.

The asexual sporulation (conidiation) pathway of the fungus Aspergillus nidulans represents an excellent model system for studying the mechanisms controlling development and pattern formation in multicellular eukaryotes. The formation of the asexual reproductive apparatus is initiated when nondifferentiated hyphae are exposed to air or starved for nutrients in liquid culture (11, 30, 34). The asexual spores (conidia) are produced by the conidiophore, a multicellular structure composed of a basal foot cell, an aerial stalk terminating in a multinucleate vesicle, a layer of uninucleate cells called metulae, and a layer of uninucleate, sporogenous cells or phialides (28). This developmental pathway is dependent on the brlA regulatory gene (1, 11), which is necessary for expression of most of the conidiation-specific genes that have been identified (35).

Although conidiophore differentiation involves the activation of several hundred genes (21, 34, 35), the functions of only a few have been elucidated. The yA gene, encoding a conidial laccase (5, 12), the wA gene, encoding a polyketide synthase necessary for conidium pigmentation (22), the rodA and dewA genes, which encode conidial cell wall-associated hydrophobic proteins (32, 33), and the catA gene, encoding the conidium-associated catalase A (27), are examples of known functions related to conidial attributes. In contrast to the yA, wA, rodA, and dewA genes, catA mRNA accumulation is not dependent on the brlA gene (27).

Two divergent and differentially regulated catalase genes have been found in A. nidulans (19, 27). Conidia from catA null mutants are H2O2 sensitive (27), whereas catB null mutants, unable to produce the vegetative catalase B, are H2O2 sensitive at the hyphal stage (18). More recently, a catalase C has been detected in catA catB double mutants (18a). The mechanisms that mediate the differential regulation of these catalases during development and oxidative stress are not known.

In this work, we studied the mechanisms responsible for the cell-type-specific localization of catalase A. We present evidence indicating that the catA message accumulates in a translationally inactive form under a variety of stress conditions and that catA translation is linked to morphogenetic processes involved in formation of metulae, phialides, and asexual or sexual spores. We found that regulatory sequences present in the catA message 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR) and first four codons are sufficient to confer catA-like regulation to the reporter gene lacZ under different conditions.

The operation of brlA-independent mechanisms regulating the expression of a gene encoding a spore-specific product such as catalase A suggests that this could represent a general mechanism during development in A. nidulans and other fungi.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth manipulations.

The genotypes of A. nidulans strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains CRN1 and CRN8 are sexual progeny from TRN3 × CRN10, CRN10 is from cross AJC9.47 (A. J. Clutterbuck), CRN2 is from TRN3 × UI-7, and CRN6 is from TRN1 × CRN10. All strains were grown in supplemented minimal-nitrate or minimal-ammonium (20 mM ammonium tartrate) medium (18). Developmental cultures were conducted as described previously (27). For brlA mutants, mycelia were scraped from 5-day-old colonies in petri dishes, fragmented, and used to inoculate liquid cultures (3). Standard genetic (29) and transformation (36) techniques were used.

TABLE 1.

A. nidulans strains used in this work

| Strain | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| AJC7.1 | biA1; brlA1 veA1 | 8 |

| CRN1 | catA (∼1400 p/l)::lacZ (argB+/argB::CAT); metG1; niiA4 brlA17 veA1 | This work |

| CRN10 | biA1; argB2; pyroA4; niiA4 brlA17 veA1 | A. J. Clutterbuck |

| CRN2 | stuA1 pabaA1 catA (∼1400 p/l)::lacZ (argB+/argB::CAT); trpC801 veA1 | This work |

| CRN6 | pabaA1 ΔargB::trpCΔB catA::argB trpC801 niiA4 brlA17 veA1 | This work |

| CRN8 | pabaA1; catA (∼1400 p/l)::lacZ (argB+/argB::CAT); niiA4 brlA17 veA1 | This work |

| FGSC-26 | biA1; veA1 | Fungal Genetic Stock Center |

| PW1 | biA1; argB2; metG1; veA1 | P. Weglenski |

| RMS011 | pabaA1 yA2; ΔargB::trpCΔB; veA1 trpC801 | 32 |

| TLK12 | pabaA1 yA2; ΔargB::trpCΔB; ΔcatB trpC801 veA1 | 18 |

| TRN1 | pabaA1 yA2; ΔargB::trpCΔB catA::argB; trpC801 veA1 | This work |

| TRN3 | biA1; catA (∼1400 p/l)::lacZ (argB+/argB::CAT); metG1; veA1 | This work |

| UI-7 | stuA1 yA2 pabaA1; trpC801 veA1 | B. Miller |

Plasmids.

A ∼6-kb EcoRI catA-containing fragment from cosmid SW22C01 (27) was cloned into Bluescript KS− (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) to generate pREN3. pREN3 was digested with SpeI and religated to remove most of the catA coding region and generate plasmid pREN7. A ∼1.4-kb KpnI-NotI fragment containing the putative catA upstream regulatory sequences was obtained from pREN7 and used to replace the yA promoter in plasmid pRA42 (6), to generate pREN8. This results in a gene fusion consisting of catA upstream regulatory sequences, the first four codons of catA, and two extra codons (Ser and Arg) derived from Bluescript sequences, fused to the lacZ region contained in pRA42 (see Fig. 2). Plasmid pREN5, used to transform strain RMS011 (32) to generate the catA-disrupted strain TRN1, was made by cloning the ∼600-bp BamHI catA fragment from pOS1A (27) into plasmid pDC1 (4).

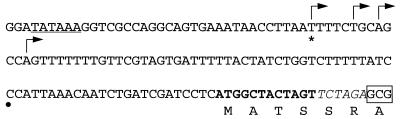

FIG. 2.

catA regulatory and coding sequences present in the catA::lacZ gene fusion included in pREN8. Arrows indicate transcription initiation sites determined by primer extension previously (27) or in this work (∗). A black dot indicates the 5′ end of catA cDNA clone C1g07a1.r2 reported in the A. nidulans expressed sequence tag database (29a). catA putative coding sequences are shown in boldface; a putative TATA box is underlined (27). The first codon from E. coli lacZ containing plasmid pRA42 (6) is boxed.

Nucleic acid isolation, manipulation, and hybridization analysis.

Total RNA was isolated by using TRIZOL (GIBCO BRL), fractionated in formaldehyde-agarose gels, transferred to Hybond-N nylon membranes (Amersham), and hybridized as suggested by the manufacturer. Radioactive probes were 32P labeled by using random primers (GIBCO BRL). Probes were the 1.5-kb PstI fragment from pCAN5 (27) for catA, the 2-kb KpnI-BamHI fragment from pSF5 (14) for actin, the 3-kb PstI-EcoRI fragment from pREN8 for lacZ, and the 1.7-kb EcoRI fragment from pDC1 for argB. Southern blot analysis was used to select transformants carrying a single copy of pREN8 integrated at the argB locus. Total DNA was isolated as described by Timberlake (34). Transcription initiation sites for catA and catA::lacZ genes were determined by primer extension reactions using oligonucleotide prenu4707 (5′ tgcggccgccatgaggatcgatcaga 3′).

Enzyme activity determination.

Catalase activity was determined in native polyacrylamide gels (20 to 40 μg of protein) as described previously (27). β-Galactosidase activity in protein extracts and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) staining were determined as reported elsewhere (3). Total protein was determined by the method of Bradford (9) or Smith et al. (31) for diluted samples.

Submerged sporulation.

For starvation experiments, 50-ml cultures in 250-ml flasks were grown for 18 h, filtered through Miracloth, washed once with minimal-glucose nitrate-free medium, resuspended in 50 ml of either glucose-free or nitrogen-free medium (250 ml flask), and incubated further as reported elsewhere (30).

RESULTS

catA mRNA translation is linked to spore formation.

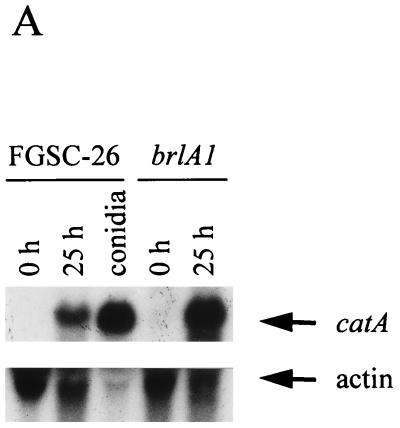

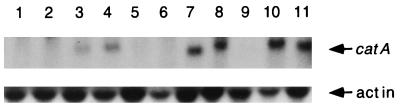

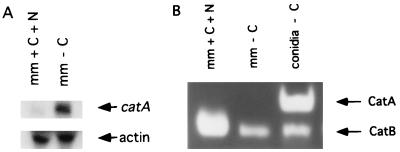

We have reported that the catA mRNA accumulates during conidiation in A. nidulans developmental mutants affected in the brlA gene (27). Except for the stalk, brlA null mutants fail to produce all conidiophore cell types. However, they are able to undergo sexual development and produce meiotic spores called ascospores (11). Results in Fig. 1A show that the catA message was virtually undetectable during growth (0 h of conidiation) in either wild-type or brlA1 null mutant strains, whereas high levels of catA mRNA were apparent in both strains after 25 h of conidiation. When protein extracts from these samples were used to determine catalase activity in native gels, CatA activity was detected in 25-h samples from the wild-type strain but not from the brlA1 mutant (Fig. 1B). In contrast, ascospores formed by a brlA null mutant, which requires several days of incubation, contained high levels of a catalase activity that comigrated with CatA. This activity was absent in ascospores from a brlA17 catA double mutant, thus confirming that CatA accumulates to high levels in sexual spores (Fig. 1B) just as it does in asexual spores (27). An antibody that recognizes CatA failed to detect the CatA antigen in a Western blot analysis using 25-h protein samples from the brlA1 mutant (not shown), arguing against the presence of an inactive form of CatA in those samples. These results suggested that the catA mRNA detected in a brlA mutant induced to conidiate is not translated unless spores are formed, in this case by the alternative sexual developmental pathway.

FIG. 1.

catA mRNA accumulation and catalase activity during growth and conidiation in wild-type and brlA1 mutant strains. (A) Total RNA extracted from growing mycelia (0 h of conidiation), mycelia induced to conidiate for 25 h, or isolated conidia were fractionated in formaldehyde-agarose gels, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized to the catA PstI fragment from pCAN5 and an actin-specific probe from pSF5. (B) Cell-free soluble protein extracts, prepared from samples at 0 and 25 h of conidiation, isolated conidia (20 μg), or ascospores (40 μg), were separated in a native polyacrylamide gel and stained for catalase activity (27). Samples corresponding to strains FGSC-26 (wild type), AJC7.1 (brlA1), and CRN6 (brlA17 catA) are indicated. Catalase A and B positions are shown by arrows.

A catA::lacZ fusion containing catA message 5′ UTR is regulated during sporulation and highly expressed in spores.

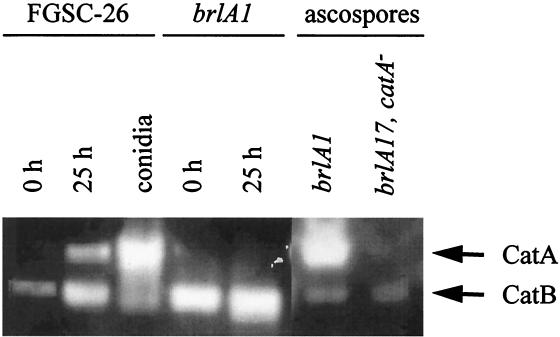

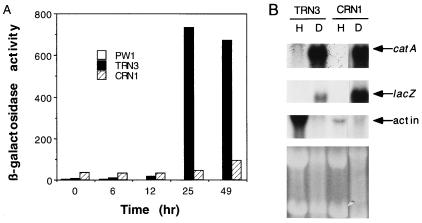

To further understand the regulation of the catA gene, we constructed plasmid pREN8, containing catA upstream sequences extending from the proposed fourth codon to ca. bp 1400 fused to the Escherichia coli lacZ gene (Fig. 2). pREN8 also contained the argB::CAT fusion to direct integration of this construct to the argB locus (17). Eighteen Arg+ transformants obtained after transforming strain PW1 with plasmid pREN8 were subjected to Southern blot analysis. Strain TRN3, which contains a single copy of pREN8 integrated at argB, was chosen for further analysis. Results in Fig. 3A show low levels of β-galactosidase specific activity (7 to 14 U) in samples from 0 to 12 h of development. In contrast, high levels of activity were detected by 25 (733 U) and 49 (670 U) h of conidiation, and much higher levels were found in isolated conidia (9,430 U). This pattern of β-galactosidase activity matched that reported for catalase A activity during conidiation (27). Control strain PW1 contained virtually undetectable levels of β-galactosidase activity during growth and conidiation.

FIG. 3.

Expression of catA and catA::lacZ reporter fusion in wild-type and brlA mutant strains during conidiation. (A) Plasmid pREN8, containing catA gene upstream sequences extending from the fourth proposed codon fused to the E. coli lacZ gene, was integrated at argB by transformation of the developmentally wild-type strain PW1. Transformant TRN3, containing a single copy of pREN8 integrated at argB, was crossed to brlA17 mutant strain CRN10 to produce the brlA17 mutant strain CRN1, containing the catA::lacZ fusion (Table 1). Both strains were grown in liquid medium for 18 h and induced to conidiate. Water-soluble protein extracts were prepared from samples harvested at the indicated times and assayed for β-galactosidase specific activity (24). The different times of development correspond to the following morphologies: 0 h of development (18 h of growth), undifferentiated hyphae; 6 h, conidiophore stalks; 12 h, conidiophores and first immature conidia; 25 h, mature conidiophores and conidia. β-Galactosidase activity in isolated conidia corresponded to 9,430 U. β-Galactosidase activities corresponding to strains TRN3 and CRN1 shown here and those indicated in the text are mean values from two independent experiments, with a maximum variation of 21% with respect to the mean. (B) Total RNA extracted from growing hyphae (H; 18 h of growth) or developmental cultures (D; 49 h of conidiation) was fractionated in formaldehyde-agarose gels, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized to catA-, lacZ-, and actin-specific probes. The bottom part shows rRNA bands in the ethidium bromide-stained gel used to prepare the blot.

To evaluate if the catA::lacZ fusion was regulated as the bona fide catA gene in a brlA null mutant background, the reporter gene was introduced by genetic crosses into a brlA17 background, to generate strain CRN1. As shown in Fig. 3A, 34 U of β-galactosidase activity was detected before induction of conidiation. Virtually no increase in enzyme activity was observed after 25 h of conidiation, and only a minor increase was detected after 49 h (Fig. 3A), whereas the catA::lacZ message was accumulated in samples from both CRN1 and the wild-type strain TRN3 after 25 (not shown) and 49 (Fig. 3B) h. Ascospores formed by the brlA17 null mutant strain CRN8 contained high levels of β-galactosidase activity (884 U), as opposed to ascospores formed by a brlA17 mutant lacking the catA::lacZ fusion, which showed undetectable levels of enzyme activity.

The transcription initiation sites of the catA::lacZ reporter gene were determined by primer extension using RNA from wild-type and brlA17 mutant strains, and no differences were detected between them. An initiation site in addition to those previously reported (27) was detected in both catA and catA::lacZ (Fig. 2). Therefore, the catA::lacZ fusion used here contains the sequences necessary for proper regulation during development. The catA message 5′ UTR is likely responsible for coupling translation to either asexual or sexual spore formation.

Spatial expression of the catA::lacZ fusion in wild-type and stuA mutant strains.

The spatial expression of the catA::lacZ reporter was determined by in situ β-galactosidase activity detection using the chromogenic substrate X-Gal. Results in Fig. 4 show that conidiophore cell types corresponding to metulae, phialides, and spores were all stained in strain TRN3 (Fig. 4A), whereas no staining was detected in control strain PW1 (Fig. 4B). This staining pattern is consistent with the time course results shown in Fig. 3, since the increase in β-galactosidase activity by 25 h corresponded with the presence of fully developed conidiophores, containing metulae, phialides, and conidiospores.

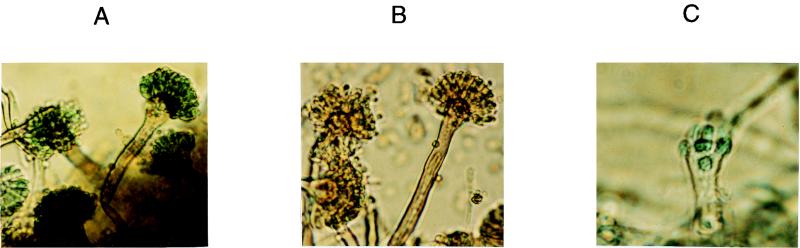

FIG. 4.

Spatial expression of the catA::lacZ reporter gene in wild-type strains and a stuA developmental mutant during conidiation. Developmentally wild-type strains TRN3 (A) and PW1 (B) and stuA mutant strain CRN2 (C) were grown in petri dishes until colonies conidiated, stained with X-Gal, and examined microscopically as reported previously (2, 3). Blue-stained cell types in conidiophores shown in panel A correspond to metulae, phialides, and conidia. Blue-stained cell types in panel C correspond to conidia formed on top of the vesicle of a stunted conidiophore. Magnifications: ×240 (A and B) and ×480 (C).

The stuA gene encodes a transcriptional repressor (13) necessary for the proper spatial expression of the brlA regulatory gene (3) and for normal conidiophore pattern formation and ascosporogenesis (11, 25). We examined the spatial expression of the catA::lacZ reporter in a stuA mutant background. stuA null mutants produce short conidiophores often lacking metulae and phialides but are able to produce conidia (3, 11). Results in Fig. 4C show that β-galactosidase activity was mainly detected in conidia formed directly from vesicles or in some cases from abnormal phialides. The β-galactosidase specific activity in isolated conidia was 393 U, which corresponded to an 8.3-fold increase over the level in samples from 0 h of conidiation. These results indicate that at least part of the conidium-specific expression of the catA::lacZ gene fusion can occur in the absence of a functional stuA gene.

Different types of stress induce catA mRNA accumulation but not catalase A activity.

Two catalase genes have been identified in A. nidulans (19, 27). The activity of the enzyme encoded by the catB gene is induced by oxidative and other types of stress (19). When the same kinds of stresses (Fig. 5) were applied for 3 h to the catB-deleted strain TLK12 grown for 12 h, no catalase A activity was detected (not shown), despite the fact that osmotic stress caused by NaCl or sorbitol, starvation for carbon or nitrogen, and to lesser extent H2O2 or paraquat treatment all induced catA mRNA accumulation (Fig. 5). These results show that in addition to air exposure (Fig. 1), other types of stress that do not result in spore production can lead to catA mRNA accumulation without catalase A activity production.

FIG. 5.

catA mRNA accumulation during different stress conditions. Mycelia from strain TLK12, grown for 12 h in minimal medium at 37°C, were transferred to minimal medium and subjected to the following treatments: lanes 1 and 2, 2 and 3 h in minimal medium, respectively (controls); lane 3, 5 mM paraquat for 2 h; lane 4, 0.5 mM hydrogen peroxide for 2 h; lane 5, 0.8 mg of uric acid per ml as the sole nitrogen source for 2 h; lane 6, 42°C for 3 h; lane 7, 1 M sorbitol for 3 h; lane 8, 1 M sodium chloride for 3 h; lane 9, 4% ethanol as the sole carbon source for 3 h; lane 10, minimal medium lacking glucose for 3 h; lane 11, minimal medium lacking nitrate for 3 h. Total RNA from the indicated conditions was fractionated in formaldehyde-agarose gels, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized to a catA-specific probe. The same membrane was hybridized to an actin probe as a loading control.

A. nidulans conidiates in liquid culture after 24 h of carbon and/or nitrogen starvation (30). Since a 3-h starvation for these nutrients resulted in catA message accumulation (Fig. 5, lanes 10 and 11), we used strain TRN3 to investigate if catalase A activity was detectable in mycelia starved for glucose during longer times or, if in this case, catalase A activity would also be restricted to conidia. Although the catA message was detected in mycelia starved for carbon during 24 h (Fig. 6A, lane 2), catalase A activity was confined to the conidia produced under those conditions (Fig. 6B, lane 3). In agreement with these results, we detected 45 U of β-galactosidase activity in mycelia starved for glucose during 24 h, compared with 468 U in isolated spores.

FIG. 6.

catA mRNA and catalase activity accumulation during starvation-induced submerged sporulation. Strain TRN3 was grown for 18 h in glucose medium and shifted to standard medium (mm + C + N) or medium lacking glucose (mm − C). Samples taken at 24 h were filtered through Miracloth to retain mycelia. The resulting filtrate was passed and rinsed through 0.22-μm-pore-size Millipore membranes to collect the conidia produced during starvation. (A) Total RNA obtained from starved mycelia was subjected to Northern blot analysis using a catA- or actin-specific probe. (B) Corresponding protein extracts were fractionated in a native polyacrylamide gel and used to determine catalase activity (27).

Taken together, our results provide support for a model in which translation of the catA message, which accumulates in response to induction of conidiation or during exposure to different types of stress, is linked to the morphogenetic processes involved in the formation of metulae, phialides, and asexual or sexual spores. In this model, translational regulation would be mediated by the 5′ UTR sequences present at the catA message.

DISCUSSION

The A. nidulans catalase A activity and corresponding mRNA are highly accumulated in conidiospores, where the enzyme provides protection against exogenous H2O2 (27). The results presented in this report show that the catA gene is subject to posttranscriptional controls and that translational regulation seems to play a major role in the cell-type-specific localization of catalase A.

brlA mutants blocked in asexual but not in sexual sporulation accumulated catA mRNA after exposure to air but failed to produce a CatA polypeptide. Nevertheless, ascospores formed by a brlA mutant contained high levels of catalase A activity, suggesting that translation of the catA message did not occur until either asexual or sexual spores started to be formed. This interpretation was further supported by the fact that temporal and spatial expression of a catA::lacZ translational fusion during development in both wild-type and brlA mutants paralleled catalase A activity. Because the transcription initiation sites of the catA::lacZ reporter corresponded to those of catA, elements present in the catA message 5′ UTR would be responsible for translational regulation during development. The catA::lacZ fusion used here contained the first four predicted CatA codons (Fig. 2). It remains to be determined if they play any specific role in translational control.

Conidial localization of β-galactosidase derived from catA::lacZ was maintained in a mutant affected in the stuA gene (Fig. 4C). However, enzyme activity in samples from 0 h of conidiation was higher in the stuA mutant than in a wild-type strain (47 and 9 U, respectively).

Exposure of nondifferentiated mycelia to different stress conditions, particularly to carbon or nitrogen starvation, also led to catA mRNA accumulation (Fig. 5). However, translational repression still restricted catalase A to the conidia produced under carbon starvation (Fig. 6). In these conditions, β-galactosidase activities derived from the catA::lacZ gene were ∼10- and 20-fold higher in isolated conidia than in starved or nonstarved mycelia, respectively. Differences in β-galactosidase activity levels were observed in comparisons of conidia and ascospores or of conidia produced in air and those formed in liquid, which might result from differences in the sporulation process per se. Despite these differences, β-galactosidase activity was always severalfold higher in spores than in mycelia.

We propose that the cell-type-specific localization of catalase A is mediated by the 5′ UTR of the catA mRNA and occurs in a two-step process. First, the catA message would accumulate in a translationally inactive form, in response to different stressful conditions, including exposure to air. This can result from increased catA transcription and/or message stabilization. Preliminary results indicate that the stability of the catA message changes under different physiological conditions (26a). In a second step, accumulated catA mRNA would be targeted to the proper location (metulae, phialides, conidiospores, and ascospores), where it would be translated. Such a process could be related to cytoskeleton remodeling during the shift from polar to budding growth associated with conidiation. The moderate increase in β-galactosidase activity observed in a brlA null mutant (Fig. 3A) indicates that translational repression of the catA::lacZ mRNA was not complete. It remains to be resolved if the catA mRNA 3′ UTR sequences play a role in translational repression or other aspects of catA posttranscriptional control.

Notable examples of mRNA localization and translational regulation during development are represented by the bicoid and nanos mRNAs. The translation of both messages at their respective locations is crucial to embryonic polarity in Drosophila. For both mRNAs, cis-acting determinants have been confined to the 3′ UTR and microtubules have been implicated in their polarized distribution (reviewed in references 15 and 23). Asymmetrical distribution of mRNA and protein occurs during Saccharomyces cerevisiae mating-type switching, which requires the HO gene. HO transcription is prevented in daughter cells by the preferential accumulation of the unstable transcriptional repressor Ash1p and the ASH1 mRNA. This process is dependent on actin, myosin, and a cis-acting element present at the 3′ UTR of the ASH1 mRNA (20, 26).

Translational regulation of the ferritin mRNA is mediated by cis-acting sequences included at the 5′ UTR, which form a stable hairpin structure termed the iron-responsive element, where a protein binds to inhibit translation (7). Recently, Gu and Hecht (16) reported that a 65-kDa protein binds to the 5′ UTR of a testis-specific Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase mRNA and specifically inhibits its in vitro translation. Also, the redox-sensitive binding of a protein to the 3′ UTR of mouse and human catalase mRNAs has been reported (10). BLAST searches using the primary sequence of the 81- to 69-nucleotide pyrimidine-rich catA mRNA 5′ UTR (27) (Fig. 2) found neither clear similarities to known sequences nor short upstream open reading frames that could mediate translational regulation. On the other hand, secondary structure analysis using the computer programs FOLD and SQUIGGLES showed only a low stability stem-loop structure (minimum free energy of −6.4), whose significance remains to be studied.

Further research is required to understand the specific mechanisms by which the catA gene is posttranscriptionally regulated and to what extent it is regulated at the transcription level. catA provides the first example of a gene encoding a conidium-specific product whose mRNA accumulates independently from the brlA regulatory gene, but it could represent a general mechanism for other genes such as those corresponding to cDNA clones CAN65, CAN11, CAN77, and CAN32 (8).

A. nidulans also contains the catB-encoded catalase B. It is interesting that different types of stress result in the accumulation of both catA and catB messages but that only the catB mRNA is readily translated (17a, 18). It is not clear why catalase A is so tightly regulated, but its targeting to spores produced by two very different developmental pathways suggests a fundamental role in spore protection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants 400346-5-2246PN from CONACyT and IN206097 from DGAPA-UNAM, México. R.E.N. was supported by a scholarship from DGAPA-UNAM.

We thank Fernando Lledías and Wilhelm Hansberg for providing the catalase antibody and A. J. Clutterbuck for providing brlA17 mutants. J. Heitman, R. Wharton, and W. Hansberg are acknowledged for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams T H, Boylan M T, Timberlake W E. brlA is necessary and sufficient to direct conidiophore development in Aspergillus nidulans. Cell. 1988;54:353–362. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90198-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguirre J, Adams T H, Timberlake W E. Spatial control of developmental regulatory genes in Aspergillus nidulans. Exp Mycol. 1990;14:290–293. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aguirre J. Spatial and temporal controls of the Aspergillus brlA developmental regulatory gene. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:211–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aramayo R, Adams T H, Timberlake W E. A large cluster of highly expressed genes is dispensable for growth and development in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics. 1989;122:65–71. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aramayo R, Timberlake W E. Sequence and molecular structure of the Aspergillus nidulans yA (laccase I) gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.11.3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aramayo R, Timberlake W E. The Aspergillus nidulans yA gene is regulated by abaA. EMBO J. 1993;12:2039–2048. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basilion J P, Rouault T A, Massinople C M, Klausner R D, Burgess W H. The iron-responsive element-binding protein: localization of the RNA-binding site to the aconitase active-site cleft. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:574–578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boylan M T, Mirabito P M, Willett C E, Zimmerman C R, Timberlake W E. Isolation and physical characterization of three essential conidiation genes from Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:3113–3118. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.9.3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clerch L B. A 3′ untranslated region of catalase mRNA composed of a stem-loop and dinucleotide repeat elements binds a 69-kDa redox-sensitive protein. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;317:267–274. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clutterbuck A J. A mutational analysis of conidial development in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics. 1969;63:317–327. doi: 10.1093/genetics/63.2.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clutterbuck A J. Absence of laccase from yellow-spored mutants of Aspergillus nidulans. J Gen Microbiol. 1972;70:423–435. doi: 10.1099/00221287-70-3-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dutton J R, Johns S, Miller B L. StuAp is a sequence-specific transcription factor that regulates developmental complexity in Aspergillus nidulans. EMBO J. 1997;16:5710–5721. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fidel S, Doonan J H, Morris N R. Aspergillus nidulans contains a single actin gene which has unique intron locations and encodes a γ-actin. Gene. 1988;70:283–293. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gavis E R. Expeditions to the pole: RNA localization in Xenopus and Drosophila. Trends Cell Biol. 1997;7:485–492. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)01162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu W, Hecht N R. Translation of a testis-specific Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD-1) mRNA is regulated by a 65-kilodalton protein which binds to its 5′ untranslated region. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4535–4543. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamer J E, Timberlake W E. Functional organization of the Aspergillus nidulans trpC promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2352–2359. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.7.2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Käfer E. Meiotic and mitotic recombination in Aspergillus and its chromosomal aberrations. Adv Genet. 1977;19:33–131. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Kawasaki, L., and J. Aguirre. Unpublished data.

- 19.Kawasaki L, Wysong D, Diamond R, Aguirre J. Two divergent catalase genes are differentially regulated during Aspergillus nidulans development and oxidative stress. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3284–3292. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3284-3292.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Long R M, Singer R H, Meng X, Gonzalez I, Nasmyth K, Jansen R P. Mating type switching in yeast controlled by asymmetric localization of ASH1 mRNA. Science. 1997;277:383–387. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinelli S D, Clutterbuck A J. A quantitative survey of conidiation mutants in Aspergillus nidulans. J Gen Microbiol. 1971;69:261–268. doi: 10.1099/00221287-69-2-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayorga M E, Timberlake W E. The developmentally regulated Aspergillus nidulans wA gene encodes a polypeptide homologous to polyketide and fatty acid synthases. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;235:205–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00279362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Micklem D R. mRNA localisation during development. Dev Biol. 1995;172:377–395. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.8048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller K Y. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller K Y, Wu J, Miller B L. StuA is required for cell pattern formation in Aspergillus. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1770–1782. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nasmyth K, Jansen R. The cytoskeleton in mRNA localization and cell differentiation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:396–400. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26a.Navarro, R. E., and J. Aguirre. Unpublished data.

- 27.Navarro R E, Stringer M A, Hansberg W, Timberlake W E, Aguirre J. catA, a new Aspergillus nidulans gene encoding a developmentally regulated catalase. Curr Genet. 1996;29:352–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliver P T P. Conidiophore and spore development in Aspergillus nidulans. J Gen Microbiol. 1972;73:45–54. doi: 10.1099/00221287-73-1-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pontecorvo G, Roper J A, Hemmons L M, MacDonald K D, Bufton A W J. The genetics of Aspergillus nidulans. Adv Genet. 1953;5:141–283. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60408-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Roe, B. A., D. Kupfer, S. Clifton, and R. Prade.Aspergillus nidulans cDNA sequencing project. http://www.genome.ou.edu/asper.html.

- 30.Skromne I, Sanchez O, Aguirre J. Starvation stress modulates the expression of the Aspergillus nidulans brlA regulatory gene. Microbiology. 1995;141:21–28. doi: 10.1099/00221287-141-1-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith P K, Krohn R I, Hermanson G T, Mallia A K, Gartner F H, Provenzano M D, Fujimoto E K, Goeke N M, Olson B J, Klenk D C. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stringer M A, Dean R A, Sewall T C, Timberlake W E. Rodletless, a new Aspergillus developmental mutant induced by directed gene inactivation. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1161–1171. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.7.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stringer M A, Timberlake W E. dewA encodes a fungal hydrophobin component of the Aspergillus spore wall. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:33–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Timberlake W E. Developmental gene regulation in Aspergillus nidulans. Dev Biol. 1980;78:497–510. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(80)90349-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Timberlake W E, Clutterbuck A J. Genetic regulation of conidiation. Prog Ind Microbiol. 1994;29:383–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yelton M M, Hamer J E, Timberlake W E. Transformation of Aspergillus nidulans by using a trpC plasmid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1470–1474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]