Abstract

COVID-19-related coagulopathy is a known complication of SARS-CoV-2 infection and can lead to intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), one of the most feared complications of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). We sought to evaluate the incidence and etiology of ICH in patients with COVID-19 requiring ECMO. Patients at two academic medical centers with COVID-19 who required venovenous-ECMO support for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) were evaluated retrospectively. During the study period, 33 patients required ECMO support; 16 (48.5%) were discharged alive, 13 died (39.4%), and 4 (12.1%) had ongoing care. Eleven patients had ICH (33.3%). All ICH events occurred in patients who received intravenous anticoagulation. The ICH group had higher C-reactive protein (P = 0.04), procalcitonin levels (P = 0.02), and IL-6 levels (P = 0.05), lower blood pH before and after ECMO (P < 0.01), and higher activated partial thromboplastin times throughout the hospital stay (P < 0.0001). ICH-free survival was lower in COVID-19 patients than in patients on ECMO for ARDS caused by other viruses (49% vs. 79%, P= 0.02). In conclusion, patients with COVID-19 can be successfully bridged to recovery using ECMO but may suffer higher rates of ICH compared to those with other viral respiratory infections.

Keywords: Anticoagulation, COVID-19, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, inflammatory markers, intracranial hemorrhage

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), can result in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) requiring mechanical ventilation (1). Large cohort studies from China and the United States have described rates of invasive mechanical ventilation in patients hospitalized for COVID-19 between 2.3% and 20.2% (2, 3). Reports focusing exclusively on patients with COVID-19 who require admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) describe mortality rates between 17% and 26% (4, 5).

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), whereby gas exchange occurs via cardiopulmonary bypass, has long been studied as an intervention for severe refractory ARDS (6, 7). Recent randomized controlled trials (RCT) and retrospective studies suggest favorable outcomes with the use of ECMO in patients with ARDS or severe viral pneumonia (6, 8, 9). Early single-center series have recently reported the use of ECMO to support patients with COVID-19 with variable results (10–12). A recent study of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) registry reported an in-hospital mortality 90 days after initiation of ECMO at 38.0% in COVID-19 patients (13). In an attempt to standardize ECMO indications and patient selection, guidance for the use of ECMO in patients with COVID-19 has been issued by ELSO, the American Society for Artificial Internal Organs (ASAIO), and the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (14–16).

Considering the limited experience with the use of ECMO in COVID-19 patients, most centers have implemented the standard ECMO management strategies used in ARDS when treating COVID-19 patients, including lung protective ventilation, sedation, medication dosing, and intravenous anticoagulation for the ECMO circuit (17). However, early clinical reports of COVID-19 suggest the presence of a severe inflammatory response as an intrinsic coagulopathy associated with a high rate of thromboembolic events including pulmonary embolism, venous thromboembolism, and major thrombotic complications while on ECMO support (18, 19). The presence of coagulopathy and abnormal coagulation parameters in COVID-19 patients has been associated with poor prognosis (20). In fact, treatment with anticoagulants has been associated with decreased mortality (21). Coagulopathy has also been proposed as a possible mechanism for patients who present with thrombotic events as a result of COVID-19, including large-vessel cerebrovascular events (22). Based on early concerns of increased thrombotic complications in patients with COVID-19, most ECMO centers have considered strict and aggressive anticoagulation during ECMO support using intravenous unfractionated heparin or direct thrombin inhibitors.

One of the most devastating complications of ECMO is intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), which is most frequently observed in patients supported with venoarterial (VA) ECMO, but which also occurs in patients on venovenous (VV) ECMO. An analysis of the ELSO registry data of nearly 5,000 patients supported by VV-ECMO for respiratory failure reported a relatively low prevalence of ICH—3.6% of cases (23). Data from the ELSO Registry found a higher rate of central nervous system hemorrhage at 6% in COVID-19 patients (13). Additionally, several reports have recently been published describing intracranial hemorrhage in patients with COVID-19 supported with ECMO (24–27). The exact pathophysiology of ICH in patients supported with ECMO is unknown, but may be related to disruption of the blood–brain barrier, alteration in hemostasis, acquired von Willebrand factor deficiency, pump-induced platelet dysfunction, consumptive coagulopathy, and the deliberate use of systemic anticoagulation to prevent - thrombosis (28, 29).

Given the known risk of ICH with ECMO support and the coagulopathy associated with COVID-19, we decided to investigate the factors related to increased ICH in patients with COVID-19 who received ECMO support and compare rates of ICH to those with other viral respiratory infections.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design and data collection

We studied adult patients with COVID-19 who required VV-ECMO support at the Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, Mass) and the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pa) between March 12, 2020 and July 21, 2020. ECMO insertion at both institutions was done using peripheral cannulation with the Seldinger technique under ultrasound guidance with a bolus of 5,000 to 10,000 U of intravenous heparin. Femoral vein and right internal jugular vein access was obtained in all cases. Therapeutic anticoagulation was achieved with either intravenous unfractionated heparin or direct thrombin inhibitors (bivalirudin and argatroban). In some cases, patients received aspirin plus subcutaneous heparin for prophylactic anticoagulation. Anticoagulation was held at the physician’s discretion. After implementation of therapeutic anticoagulation, activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) was recorded every 6 h after a dose change or bolus. Once within range for 24 h, aPTT checks were reduced to twice daily. By protocol, the goal aPTT range at one institution was set by the physician at either 63 to 83 s versus 70 to 100 s. These higher than typical targets were due to hospital testing reagents that resulted in higher than normal aPTT therapeutic ranges. At the other institution, goal aPTT was kept at 45 to 60 s. Alternatively, goal aPTT ranges could be adjusted at the physician’s discretion on a case-by-case basis.

Intracranial hemorrhage was identified by imaging, and the patients were divided into two cohorts based on the presence of ICH. In one patient, ICH was identified clinically via neurological examination rather than by imaging. When imaging was available, the location and size of the lesions were described. Demographic data and comorbidities were reported. The most recent laboratory values prior to cannulation were noted, as were arterial blood gas values immediately before and after cannulation. The highest laboratory values for interleukin-6 (IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin, ferritin, and D-dimer during the hospital stay were recorded to measure the potential impact of these inflammatory markers. The Murray Score for acute lung injury was calculated to gauge severity of respiratory illness, as was the PaO2/ FiO2 ratio. COVID-19-directed therapies, ICU therapies, and anticoagulatory agents administered were also included in the analysis.

Outcomes included in-hospital mortality and cause of death. Days from admission to intubation and intubation to ECMO were also noted. Days on ECMO, ICU length of stay, and hospital length of stay were calculated up until the censoring date. Non-neurologic complications of ECMO, including bleeding requiring transfusion, oropharyngeal bleeding, pulmonary hemorrhage, acute kidney injury requiring dialysis, and circuit thrombosis or failure requiring membrane replacement, were also assessed.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were analyzed using the Fisher exact test and reported as counts and percentages. Continuous variables were compared using either the Mann-Whitney U test, reporting median and interquartile range (IQR), or the two-tailed Student’s t test, reporting mean standard deviation. A historical control group of 45 patients supported with VV-ECMO for non-COVID-19 viral ARDS at the same institutions was identified. These patients were treated between January 1, 2014 and February 28, 2020, and their diagnoses included influenza A, influenza B, influenza H1N1, and parainfluenza. The patients were propensity-score matched with the COVID patients by age and sex with replacement using the method of nearest neighbors with a 30% caliper and distance measured on the logit scale to generate 33 propensity-matched pairs. Survival free of ICH in patients who required VV-ECMO support for COVID-19 and in patients requiring VV-ECMO support for ARDS of other viral etiologies was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (v8.4.2, GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif) and R version 4.0.0. This project was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both participating centers (IRB # 2020P001636 and IRB# 843370).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics, laboratory values, and interventions

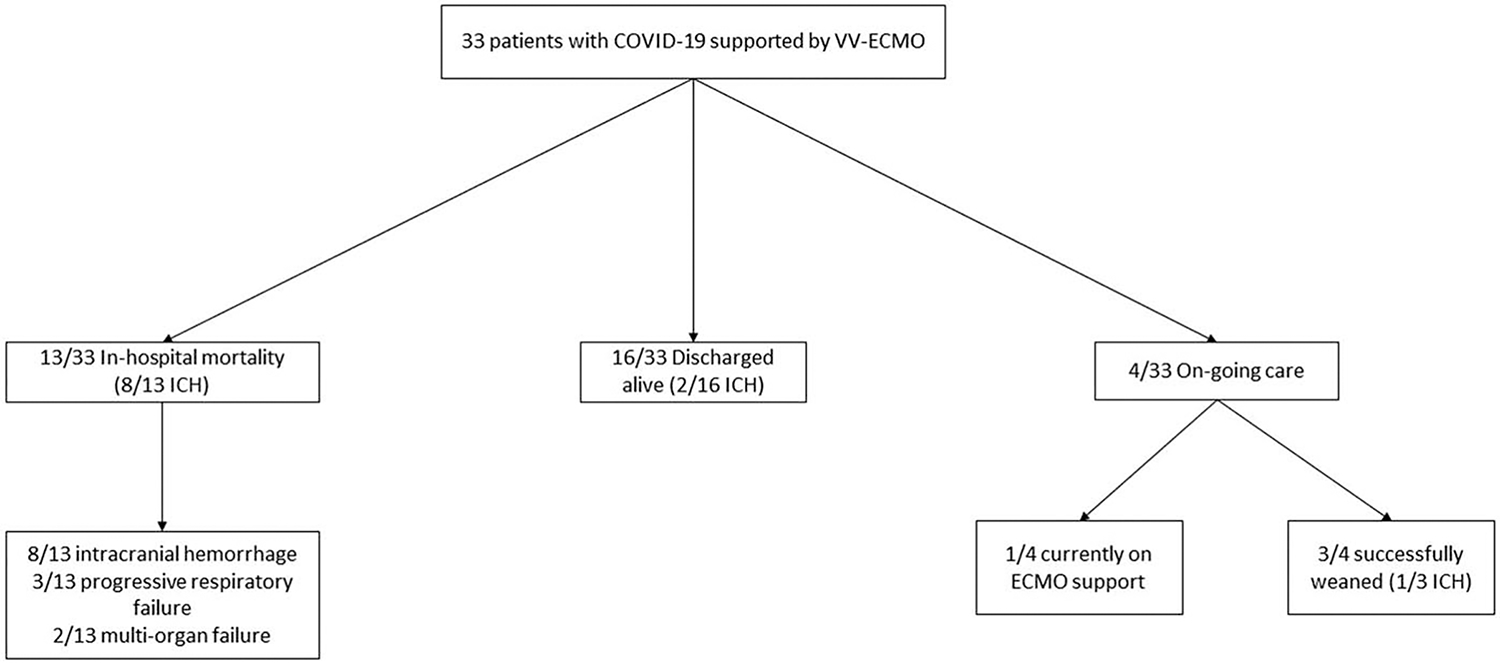

A total of 33 patients with COVID-19 required ECMO support during the study period (Fig. 1). Their median age on admission was 53 years (IQR 42–59), and most were male (24 patients, 73%). Their median body mass index was 33 (IQR 30–35), and the most common comorbidities were hypertension (39%) and diabetes (27%). ICH occurred in 11 patients (33%). Analysis of patients with ICH versus patients without ICH demonstrated no significant differences in demographics, comorbidities, and laboratory values at cannulation (Table 1).

FIG. 1. Study flow chart.

ECMO indicates extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; MOF, multi-organ failure; VV, venovenous.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Intracranial hemorrhage (n = 11) |

No intracranial hemorrhage (n = 22) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Demographics | |||

| Age, median (IQR) | 53 (42–59) | 53 (41–59) | 0.83 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 8 (73) | 16 (73) | >0.99 |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 33 (27–34) | 33 (31–37) | 0.62 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 6 (55) | 7 (32) | 0.27 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (45) | 4 (18) | 0.12 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1 (9) | 1 (5) | >0.99 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0 | 0 | >0.99 |

| Heart failure | 0 | 1 (5) | >0.99 |

| Prior CVA | 1 (9) | 0 | 0.31 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 0 | 3 (14) | 0.53 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1 (9) | 1 (5) | >0.99 |

| Malignancy | 0 | 0 | >0.99 |

| Laboratory values at cannulation, median (IQR) | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.5 (8.8–13.8) | 11.0 (9.8–12.7) | 0.35 |

| White blood cell count (K/uL) | 10.2 (6.9–19.8) | 13.5 (11.0–16.0) | 0.45 |

| Platelets (K/uL) | 275 (182–303) | 283 (219–335) | 0.27 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 30 (13–54) | 26 (14–36) | 0.74 |

| Creatinine, serum (mg/dL) | 1.58 (0.78–3.45) | 1.15 (0.72–1.56) | 0.31 |

| Lactic acid (mmol/L) | 1.8 (1.0–4.3) | 1.7 (1.3–2.5) | 0.86 |

| INR | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 0.90 |

BMI indicates body mass index; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CRP C-reactive protein; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; INR, international normalized ratio; IQR, interquartile range; PTT, partial thromboplastin time.

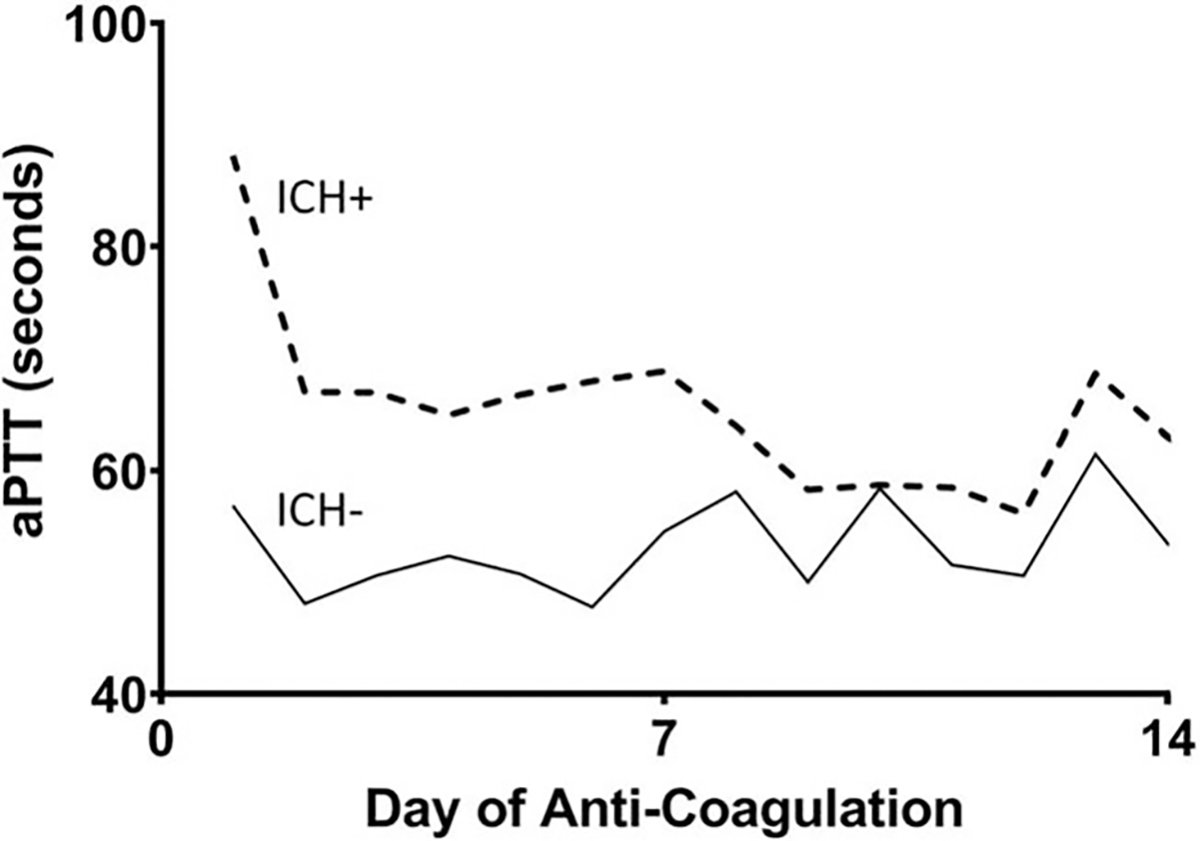

At the time of cannulation, there were no significant differences in Murray Score or prior utilization of COVID-19-specific or ARDS-related therapeutic interventions between the two groups (Table 2). Patients who developed ICH were significantly more acidemic before (pH 7.21 vs. 7.32, P < 0.01) and after (pH 7.30 vs. 7.38, P <0.001) cannulation. Serum bicarbonate was also lower after cannulation in the ICH group (21 vs. 26, P < 0.01). Unfractionated heparin, argatroban, and bivalirudin were used as intravenous anticoagulants. All ICH events occurred in patients who received intravenous anticoagulation. None of the patients who received prophylactic anticoagulation, defined as aspirin used in combination with subcutaneous heparin, developed ICH (Table 2). The overall mean aPTT was higher in the ICH cohort (57.6 s vs. 45.4 s, P < 0.0001), as was the mean highest-per-day aPTT (63.6s vs. 41.2s, P < 0.0001). Of note, the mean highest aPTT on any given day of anticoagulation was generally lower in the cohort without intracranial bleeding (Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

Respiratory characteristics and interventions

| Intracranial hemorrhage (n = 11) |

No intracranial hemorrhage (n = 22) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Respiratory illness severity, median (IQR) | |||

| pO2/FiO2 ratio | 66 (52–96) | 78 (60–95) | 0.72 |

| Murray score | 3.7 (3.3–3.8) | 3.5 (3.5–3.8) | 0.30 |

| ABG prior to cannulation, median (IQR) | |||

| PH | 7.21 (7.15–7.27) | 7.32 (7.27–7.36) | <0.01 |

| pCO2 (mm Hg) | 68 (49–87) | 53 (46–63) | 0.19 |

| pO2 (mm Hg) | 66 (52–93) | 69 (62–87) | 0.64 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 23 (22–30) | 27 (24–32) | 0.22 |

| ABG after cannulation, median (IQR) | |||

| pH | 7.30 (7.26–7.34) | 7.38 (7.34–7.44) | <0.001 |

| pCO2 (mm Hg) | 45 (40–47) | 43 (35–53) | 0.67 |

| pO2 (mm Hg) | 133 (92–172) | 104 (89–145) | 0.33 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 21 (20–23) | 26 (22–28) | <0.01 |

| COVID-19 therapies, n (%) | |||

| Glucocorticoids | 5 (45) | 12 (55) | 0.72 |

| Statin | 3 (27) | 8 (37) | 0.71 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 6 (55) | 12 (55) | >0.99 |

| Azithromycin | 8 (73) | 15 (68) | >0.99 |

| Remdesivir | 3 (27) | 7 (32) | >0.99 |

| Tocilizumab | 3 (27) | 12 (55) | 0.27 |

| Convalescent Plasma | 4 (36) | 8 (36) | >0.99 |

| ARDS therapies, n (%) | |||

| Neuromuscular blockade | 11 (100) | 20 (91) | 0.54 |

| Prone positioning | 10 (91) | 21 (95) | >0.99 |

| Inhaled pulmonary vasodilators | 7 (64) | 14 (64) | >0.99 |

| Vasopressors | 11 (100) | 22 (100) | >0.99 |

| Anticoagulant, n (%) | |||

| Intravenous Anticoagulation | 11 (100) | 17 (77) | 0.14* |

| Heparin | 10 | 15 | |

| Bivalirudin | 2 | 2 | |

| Argatroban | 1 | 0 | |

| Aspirin + Subcutaneous Heparin | 0 | 5 (23) | |

P value reflects Fisher exact test between those receiving intravenous anticoagulation versus aspirin plus subcutaneous heparin.

FiO2 indicates fraction of inspired oxygen; IQR, interquartile range; pCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; pO2, partial pressure of oxygen.

FIG. 2. Mean highest daily aPTT is higher in patients who developed ICH as compared with patients without ICH.

Data shown includes the first 14 days, which is the median number of days on anticoagulation.

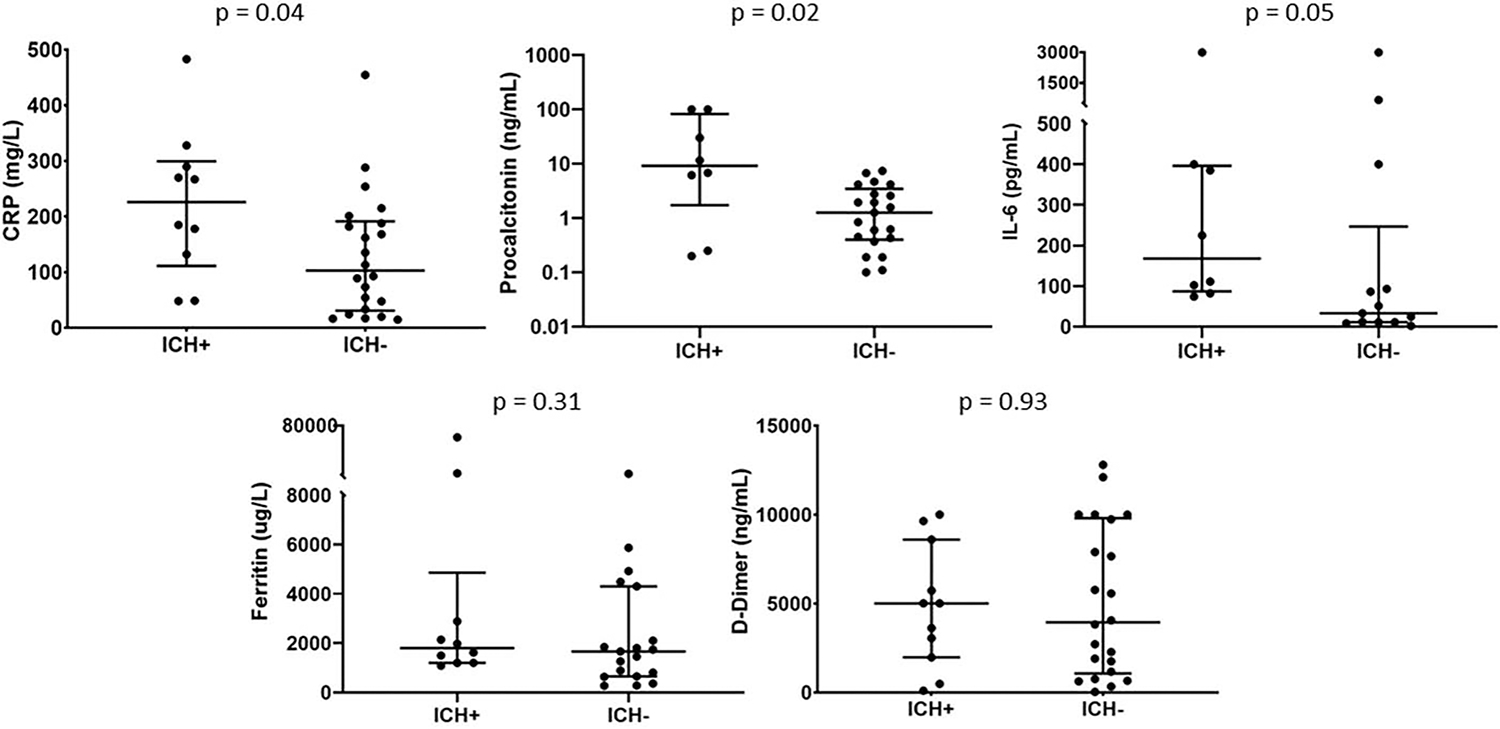

When we compared the peak values of five inflammatory markers, the patients who developed ICH had significantly higher CRP (226mg/L vs. 103mg/L, P = 0.04) and procalcitonin (9.2ng/mL vs. 1.3ng/mL, P = 0.02) than the patients without ICH. There was a trend toward a significantly higher median peak level of IL-6 in the ICH group as well (168pg/ml vs. 33pg/mL, P = 0.05). There were no significant differences in ferritin (1,795ug/L vs. 1,663ug/L, P = 0.31) and D-dimer (5,009ng/mL vs. 3,941ng/mL, P = 0.93) between the two patient groups (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3. Highest laboratory values for inflammatory markers during hospitalization.

ICH+ vs. ICH− median values: CRP 226 mg/L vs. 103 mg/L, P = 0.04; procalcitonin 9.2 ng/mL vs. 1.3 ng/mL, P = 0.02; IL-6 168 pg/mL vs. 33 pg/mL, P = 0.05; ferritin 1795 ug/L vs. 1663 ug/L, P = 0.31, D-Dimer 5009 ng/mL vs. 3941 ng/mL, P = 0.93.

Outcomes

Of the 33 patients with COVID-19 who required ECMO support, 16 were successfully discharged (48.4%) and 13 died during the hospital stay (39.4%). At the time of data censorship to complete this analysis, four patients (12.1%) remained hospitalized. Of these, three patients had been successfully weaned from ECMO and one remained on support (Fig. 1). In-hospital mortality was significantly higher in the ICH group than in the non-ICH group (82% vs. 18%, P < 0.001; Table 3). Two patients who suffered ICH were discharged. Length of stay in the ICU was significantly longer in the non-ICH cohort (16 vs. 32 days, P = 0.01). Non-neurologic ECMO complications were not significantly different between groups (Table 3). Additional data regarding the timing of intracranial hemorrhage by case can be found in the supplement (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SHK/B211, which shows days from ECMO cannulation to ICH, total days on ECMO, and cause of death for each case in the intracranial hemorrhage cohort).

TABLE 3.

Mortality, length of stay, and complications

| Intracranial hemorrhage (n = 11) |

No intracranial hemorrhage (n = 22) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 9 (82) | 4 (18) | <0.001 |

| Cause of death, n (%) | |||

| Intracranial Hemorrhage | 8 (89) | - | - |

| Multi-organ failure | 0 | 2 (50) | 0.08 |

| Respiratory failure | 1 (11) | 2 (50) | 0.20 |

| Length of stay, median (IQR) | |||

| Days from admission to intubation | 0 (0–4) | 3 (1–8) | 0.07 |

| Days from intubation to ECMO | 6 (1–8) | 3 (2–6) | 0.36 |

| Days on ECMO | 9 (3–23) | 18 (8–29) | 0.13 |

| ICU length of stay | 16 (11–31) | 32 (25–60) | 0.01 |

| Hospital length of stay | 21 (14–37) | 38 (31–76) | <0.01 |

| Non-neurologic ECMO complications, n (%) | |||

| Bleeding requiring transfusion | 4 (36) | 13 (59) | 0.28 |

| Oral bleeding | 1 (9) | 1 (5) | >0.99 |

| Pulmonary Hemorrhage | 1 (9) | 1 (5) | >0.99 |

| Acute kidney injury requiring dialysis | 6 (55) | 8 (36) | 0.46 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 1 (9) | 4(18) | 0.64 |

| ECMO circuit failure* | 0 | 2 (9) | 0.54 |

Circuit failure was caused by oxygenator thrombosis and required emergent exchange.

ECMO indicates extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IQR, interquartile range.

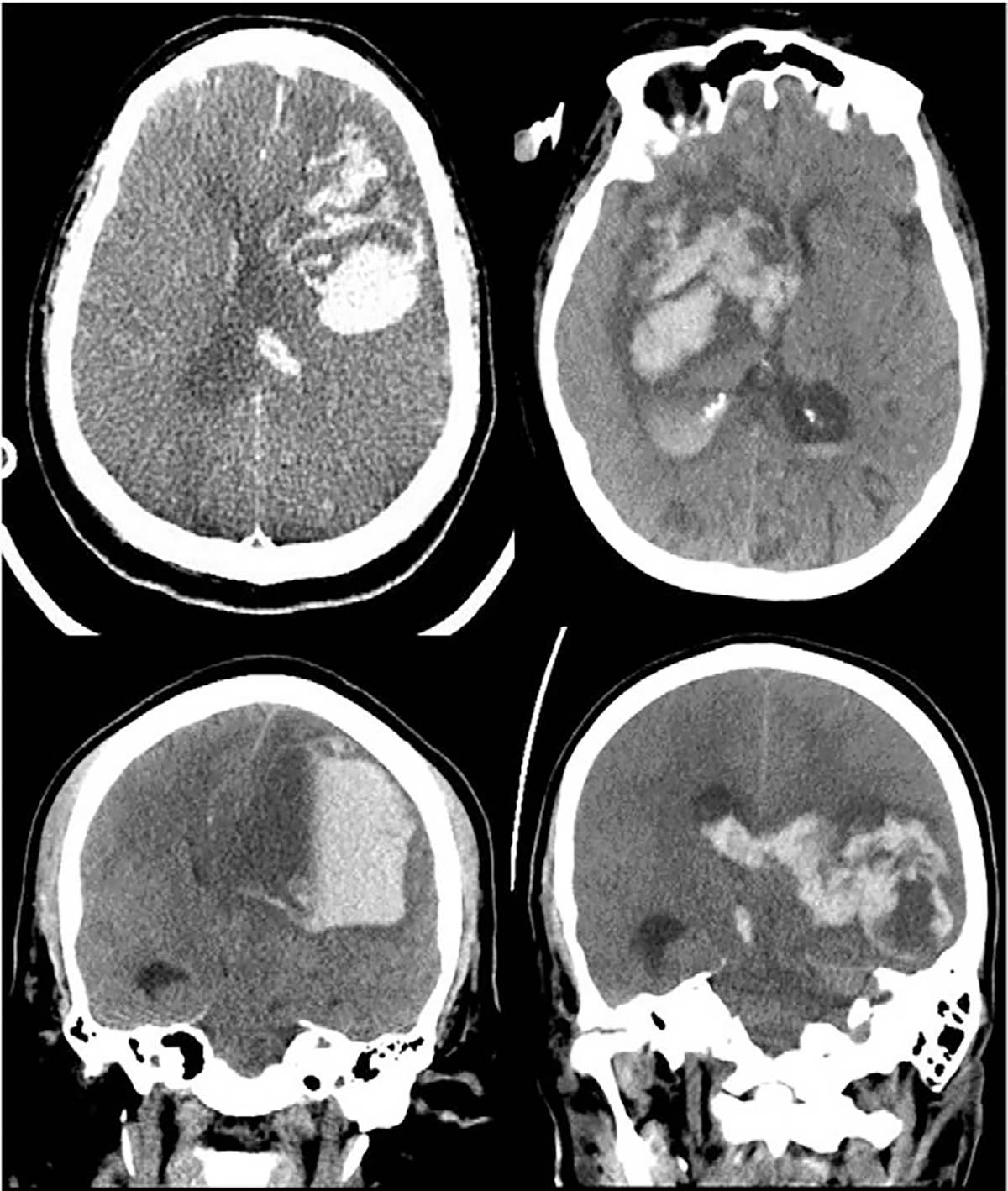

In six patients, ICH was characterized as “large” on CT and involved primarily the frontal lobe in three patients, primarily the temporal lobe in two patients, and the basal ganglia in one patient (Fig. 4). One patient suffered a small subarachnoid hemorrhage, also most notable in the frontal lobes. In one patient, who died while on ECMO, ICH was diagnosed clinically on the basis of the sudden onset of fixed, dilated pupils followed by profoundly worsening shock, and an imaging study was not performed. In two patients, ICH was discovered on MRI as multifocal punctate hemorrhages found after decannulation, but these ICHs are thought to have occurred while the patients were on ECMO. In one patient, a fatal large right cerebellar hemorrhage occurred 4 days after ECMO decannulation.

FIG. 4. Selected CT images of ICH in four patients.

Top left: large left frontal intraparenchymal hemorrhage with surrounding edema and rightward midline shift. Top right: large right basal ganglia intraparenchymal hemorrhage with surrounding edema, effacement of the right lateral ventricle, and leftward midline shift. Bottom left: large left frontal intraparenchymal hemorrhage with surrounding edema, fluid level, and near complete effacement of the left lateral ventricle. Bottom right: large left temporal hematoma compressing the ventricular system with surrounding edema and rightward midline shift with associated intraventricular hemorrhage and right midline shift.

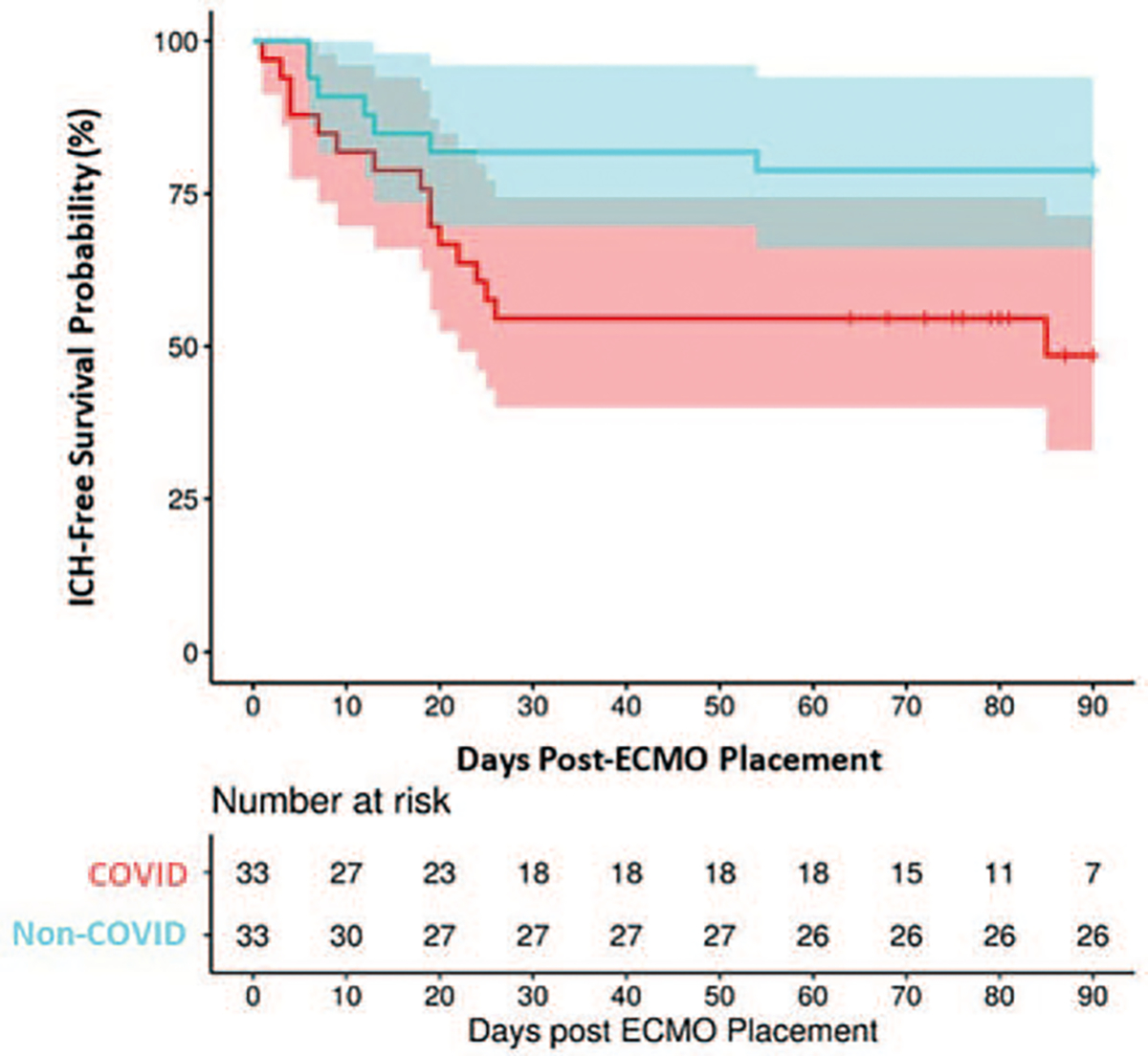

To evaluate if outcomes after ECMO support in patients with COVID-19 were similar to the outcomes of patients requiring ECMO support for ARDS caused by other viruses, the patients in this study were propensity matched with a historical control group of 33 patients supported with VV-ECMO for non-COVID-19 viral ARDS (Table 4). Ninety-day ICH-free survival of COVID-19 patients with ARDS supported on ECMO was significantly lower than ICH-free survival in matched patients supported for ARDS secondary to other viral etiologies (49% vs. 79%, P = 0.02) (Fig. 5).

TABLE 4.

Propensity-matched patients requiring ECMO support for COVID-19 versus non-COVID-19 viral etiologies

| COVID-19 (n = 33) |

Non-COVID-19 (n = 33) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Demographics | |||

| Age, median (IQR) | 53 (42–59) | 51 (44–56) | 0.58 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 24 (73) | 24 (73) | >0.99 |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 33 (30–35) | 30 (28–36) | 0.14 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 13 (39) | 9 (27) | 0.43 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 (27) | 6 (18) | 0.56 |

| Coronary artery disease | 2 (6) | 1 (3) | >0.99 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0 | 0 | >0.99 |

| Heart failure | 1 (3) | 0 | >0.99 |

| Prior CVA | 1 (3.0) | 0 | >0.99 |

| Chronic Pulmonary disease | 3 (9) | 6 (18.2) | 0.48 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2 (6.1) | 0 | 0.49 |

| Malignancy | 0 | 0 | >0.99 |

| Respiratory illness severity, median (IQR) | |||

| pO2/FiO2 ratio | 79 (59–96) | 66 (54–71) | 0.06 |

| Murray score | 3.6 (3.5–3.8) | 3.7 (3.5–3.7) | 0.95 |

| ABG prior to cannulation, median (IQR) | |||

| PH | 7.30 (7.20–7.30) | 7.30 (7.20–7.30) | 0.66 |

| pCO2 (mm Hg) | 54 (46–67) | 53 (50–68) | 0.79 |

| pO2 (mm Hg) | 69 (60–87) | 63 (54–71) | 0.08 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 26 (23–31) | 22 (20–29) | 0.11 |

| Days on ECMO, median (IQR) | 12 (5–23) | 10 (5–16) | 0.81 |

| Anticoagulant, n (%) | |||

| Intravenous Anticoagulation | 28 (85) | 33 (100) | |

| Heparin | 25 | 30 | 0.05* |

| Bivalirudin | 4 | 2 | |

| Argatroban | 1 | 1 | |

| Aspirin + Subcutaneous Heparin | 5 (15) | 0 | |

| Timing of ICH, days post-cannulation, median (IQR) | 9 (4–20) | 7 (5–17) | 0.75 |

| Incidence of ICH, n (%) | 11 (33) | 4 (12) | 0.04 |

| In-hospital mortality | 13 (39) | 9 (27) | 0.29 |

| Causes of death, n (%) | |||

| ICH | 8 (62) | 3 (33) | 0.19 |

| Respiratory failure | 3 (23) | 5 (56) | 0.12 |

| Multi-organ failure | 2 (15) | 1 (11) | 0.77 |

P value reflects Fisher exact test between those receiving intravenous anticoagulation versus aspirin plus subcutaneous heparin.

ABG indicates arterial blood gas; BMI, body mass index; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; IQR, interquartile range; pCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; pO2, partial pressure of oxygen.

FIG. 5. ICH-free survival probability in COVID-19 patients (49%; 95% CI: 33%, 72%) as compared with matched patients with non-COVID viral ARDS (79%; 95% CI: 66%, 94%) (P = 0.02).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we retrospectively evaluated our initial experience, at two large academic institutions, with the use of VV-ECMO in patients who developed severe refractory respiratory failure secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection. We report that ECMO can be safely implemented in this relatively new patient population as a bridge to successful recovery. However, an unexpectedly high rate of ICH (one-third) in patients supported with ECMO due to ARDS from COVID-19 raises concerns and questions regarding the causes of this complication. Direct viral vascular and parenchymal involvement and the safety of a strict anticoagulation strategy in COVID-19 patients should be considered, especially in light of multiple studies reporting a high rate of thrombotic events in patients with COVID-19 (22,30,31). We also observed in our study that overall short-term (90 day) survival free of ICH in COVID-19 patients was significantly lower than ICH-free survival in patients supported on ECMO at the same institutions for ARDS secondary to other viral infections.

Neurologic injuries in patients on ECMO can be severe and life-threatening. During VA-ECMO, up to 15% of patients are expected to suffer from neurological complications usually related to anoxic injury in the presence of profound shock or direct arterial cannulation and secondary thromboembolic events (32). Further, neurological symptoms are common in patients with COVID-19. An autopsy analysis suggested evidence of pronounced brain involvement in fatal COVID-19, with massive ICH as a frequent cause of death in patients younger than 65 years of age. The authors found that in addition to viral pneumonia, a pronounced central nervous system (CNS) involvement with pan-encephalitis, meningitis, and brainstem neuronal cell damage was a key event in all fatalities (33). In a recently published, large study of 214 patients with COVID-19, 78 patients (36.4%) had neurological manifestations, such as headache, dizziness, acute cerebrovascular disease, and impaired consciousness. In 40 of these patients (18.7%), the neurological manifestations were considered severe (34).

Additionally, a COVID-associated coagulopathy seems to be frequently present in patients suffering from SARS-CoV-2 (35). The thrombotic events related to SARS-CoV-2 infection are thought to be secondary to inflammatory activation of the endothelial layer resulting in a hypercoagulable state (36). This hypercoagulable state manifests clinically in COVID-19 patients with an increased rate of venous thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism, which has been observed in 11% to 20% of patients (37). Concordant with these data, venous thromboembolism was observed in 9% and 18% of subjects with and without ICH in our study, respectively. That being said, there were no differences between ICH and non-ICH cohorts with regard to venous thromboembolism or ECMO circuit occlusions.

We observed a significant increase in acute markers of inflammation, including CRP (P = 0.04) and procalcitonin (P = 0.02), and nearly significantly higher IL-6 levels (P = 0.05), in COVID-19 patients who suffered ICH as compared to patients without ICH. Similarly, von Weyhern and colleagues observed high levels of IL-6 in patients with COVID-19 and pathologic confirmation of fatal ICH (33). Although their findings were suggestive of clear encephalitis, meningitis, and petechial bleeding, the authors could not determine in an autopsy study whether the observed lesions were a direct consequence of virus infiltration or resulted from an immune and inflammatory response. Elevated levels of IL-6, one of the major regulators of the acute phase response, have been associated with higher in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 (18, 38).

The inflammatory response and coagulopathy seen as a consequence of COVID-19 might be worsened during ECMO by the continuous contact between patient blood and the extracorporeal circuit, which is known to cause an independent systemic inflammatory response that is also characterized by elevation of IL-6, and increased consumption of coagulation factors (39–41). The resultant imbalance between pro-coagulant and anticoagulant states can then result in uncontrolled thrombosis or bleeding (39). Interestingly, and as an unexpected finding, our study cohort was mainly characterized by bleeding complications and only two cases of oxygenator thrombosis requiring emergent exchange occurred (5%), differing from recent series suggesting a higher risk of thrombotic events in COVID-19 patients on ECMO including a 17% reported incidence of oxygenator thrombosis (19).

The highly inflammatory state of COVID-19 may be accentuated by the use of extracorporeal ECMO surfaces. This, combined with the potential for viral CNS parenchymal involvement, may increase the risk for ICH. Additionally, the situation can become even more dire due to the delicate balance between clotting and thrombosis and the need for anticoagulation in patients supported with ECMO. The optimal anticoagulation strategy, monitoring test, and target ranges during VV-ECMO are still debated, even in non-COVID patients (42). Our approach to anticoagulation was individualized for each patient, guided by protocols for non-COVID-19 patients and weighing the risks of bleeding and thrombosis as best we could based on the limited evidence available since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the most important findings of our study is that patients who developed ICH had significantly higher aPTT levels, measured both over the course of admission and as the highest value recorded daily.

In this study, ICH occurred in patients receiving intravenous anticoagulation, but there were no ICH events in patients receiving aspirin plus subcutaneous heparin. These findings suggest that when considering the balance between clotting and bleeding, lower aPTT levels or anti-Xa levels should be targeted in patients with COVID-19 who require ECMO support, especially when the patient exhibits signs of an active systemic inflammatory response with tendency for hypotension or the presence of significantly elevated inflammatory markers (IL-6, CRP, procalcitonin) who may have, by definition, increased vascular permeability. Based on the current lack of studies to support this concept and the concerns of a pro-coagulable state, it is unclear if all patients supported on ECMO for COVID-19 should be considered at high risk for bleeding complications on ECMO or only those with a high inflammatory profile. Furthermore, it is unclear if anticoagulation should be managed with low-dose anticoagulants, or even without anticoagulation, as has been done safely in some non-COVID-19 patients requiring VV-ECMO support (43, 44). Since the study period, both institutions have made changes to their anticoagulation protocols in an attempt to either reduce high levels of anticoagulation or aPTT variability.

Interestingly, there were large differences between rates of ICH reported in our study compared with that of the ELSO registry (33.3% vs. 6.0%) (13). That being said, mortality rates between the studies were strikingly similar (39.4% vs. 38.0%). The reason for this difference is unclear. The overall mean aPTT and mean highest-per-day aPTT were 57.6 and 63.6 s, respectively, in the ICH group. These values are arguably not outside the standard of care for patients on ECMO. Nonetheless, we are left to wonder if the higher rates of ICH in our study are due to higher aPTT levels or if ICH at our hospitals were detected at higher rates than other centers. Further, high rates of ICH early on may have skewed our perspective. Increased aPTTs in our group combined with hypervigilance and attention to ICH at our institutions may have translated into similar mortality rates between groups despite differences in rates of intracranial hemorrhage.

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective nature carries limitations common to most observational studies. Second, the small number of patients included in this series and the different anticoagulation strategies used could affect the significance of the results. Notably, the institution with higher aPTT targets (63–83s or 70–100s) had a 40% (6 of 15) ICH rate. On the other hand, the institution with the lower aPTT target (45–60 s) only had ICH in 27% (5 of 18) of cases.

Finally, some of the cases included herein have been reported in the form of case series (26, 45). However, we report ICH-free survival between patients with COVID-19 versus other viral respiratory infections and show significant differences in inflammatory markers that these reports did not.

In conclusion, patients with COVID-19 and severe refractory respiratory failure can be successfully bridged to recovery with VV-ECMO. A higher rate of ICH compared with non-COVID-19 viral respiratory infections may be observed due to a combination of a marked systemic inflammatory response and potential CNS viral involvement. For these reasons, lower aPTT targets than those typically used for ECMO may be appropriate in this patient population, especially in the presence of active inflammation. Future studies will be needed to clarify the optimal anticoagulation strategy for patients with COVID-19 who require ECMO support.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citation appears in the printed text and is provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.shockjournal.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, Huang H, Zhang L, Zhou X, Du C, et al. : Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med 180(7):934–943, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu YY, Liang W, Ou C, He J, Liu L, Shan H, Lei C, Hui DSC, et al. : Clinical characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 382(18):1708–1720, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, Barnaby DP, Becker LB, Chelico JD, Cohen SL, et al. : Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA 323(20):2052–2059, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziehr DR, Alladina J, Petri CR, Maley JH, Moskowitz A, Medoff BD, Hibbert KA, Thompson BT, Hardin CC: Respiratory pathophysiology of mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19: a cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 201(12):1560–1564, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Antonelli M, Cabrini L, Castelli A, Cereda D, Coluccello A, Foti G, Fumagalli R, et al. : Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA 323(16):1574–1581, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peek G, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, Wilson A, Allen E, Thalanany M, Hibbert C, Truesdale A, Clemens F, Cooper N, et al. : Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 374(9698):1351–1363, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Combes A, Hajage D, Capellier G, Demoule A, Lavoue S, Guervilly C, Da Silva D, Zafrani L, Tirot P, Veber B, et al. : Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. New Engl J Med 378(21):1965–1975, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alshahrani MS, Sindi A, Fayez A, Al-Omari A, El Tahan M, Alahmadi B, Zein A, Khatani N, Al-Hameed F, Alamri S, et al. : Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Ann Intensive Care 8(1):3, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies A, Jones D, Bailey M, Beca J, Bellomo R, Blackwell N, Forrest P, Gattas D, Granger E, Herkes R, et al. : Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for 2009 influenza A(H1N1) acute respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA 302(17):1888–1895, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X, Guo Z, Li B, Zhang X, Tian R, Wu W, Zhang Z, Lu Y, Chen N, Clifford SP, et al. : Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Shanghai, China. ASAIO J 66(5):475–481, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, Wu Y, Zhang L, Yu Z, Fang M, et al. : Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 8(5):475–481, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sultan I, Habertheuer A, Usman AA, Kilic A, Gnall E, Friscia ME, Zubkus D, Hirose H, Sanchez P, Okusanya O, et al. : The role of extracorporeal life support for patients with COVID-19: preliminary results from a statewide experience. J Card Surg 35(7):1410–1413, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbaro RP, MacLaren G, Boonstra PS, Iwashyna TJ, Slutsky AS, Fan E, Bartlett RH, Tonna JE, Hyslop R, Fanning JJ, et al. : Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support in COVID-19: an international cohort study of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry. Lancet 396(10257):1071–1078, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajagopal K, Keller S, Akkanti B, Bime C, Loyalka P, Cheema FH, Zwischen-berger JB, El Banayosy A, Pappalardo F, Slaughter MS, et al. : Advanced pulmonary and cardiac support of COVID-19 patients: emerging recommendations from ASAIO—a living working document. Circ Heart Fail 13(5):e007175, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartlett R, Ogino M, Brodie D, McMullan DM, Lorusso R, MacLaren G, Stead CM, Rycus P, Fraser JF, Belohlavek J, et al. : Initial ELSO Guidance Document: ECMO for COVID-19 patients with severe cardiopulmonary failure. ASAIO J 66(5):472–474, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, Loeb M, Gong MN, Fan E, Oczkowski S, Levy MM, Derde L, Dzierba A, et al. : Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Intensive Care Med 46(5):854–887, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brogan TV, Lequier L, Lorusso R, MacLaren G, Peek G: Extracorporeal Life Support: The ELSO Red Book. 5th Edition. Ann Arbor, MI: ELSO; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J,Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, et al. : Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 396(10229):1054–1062, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, Leonard-Lorant I, Ohana M, Delabranche X, Merdji H, Clere-Jehl R, Schenck M, Fagot Gandet F, et al. : High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med 46(6):1089–1098, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z: Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost 18(4):844–847, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z: Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost 18(5):1094–1099, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, Kellner CP, Shoirah H, Singh IP, De Leacy RA, Shigematsu T, Ladner TR, Yaeger KA, et al. : Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of Covid-19 in the young. N Engl J Med 382(20):e60, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorusso R, Gelsomino S, Parise O, Di Mauro M, Barili F, Geskes G, Vizzardi E, Rycus PT, Muellenbach R, Mueller T, et al. : Neurologic injury in adults supported with veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for respiratory failure: findings from the extracorporeal life support organization database. Crit Care Med 45(8):1389–1397, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heman-Ackah SM, Su YRS, Spadola M, Petrov D, Chen HI, Schuster J, Lucas T: Neurologically devastating intraparenchymal hemorrhage in COVID-19 patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a case series. Neurosurgery 87(2):E147–E151, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zahid MJ, Baig A, Galvez-Jimenez N, Martinez N: Hemorrhagic stroke in setting of severe COVID-19 infection requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 29(9):105016, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Usman AA, Han J, Acker A, Olia SE, Bermudez C, Cucchiara B, Mikkelsen ME, Wald J, Mackay E, Szeto W, et al. : A case series of devastating intracranial hemorrhage during venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for COVID-19. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 34(11):3006–3012, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masur J, Freeman CW, Mohan S: A double-edged sword: neurologic complications and mortality in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy for COVID-19–related severe acute respiratory distress syndrome at a tertiary care center. Am J Neuroradiol; 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fletcher-Sandersjöö A, Thelin EP, Bartek J, Broman M, Sallisalmi M, Elmi-Terander A, Bellander BM: Incidence, outcome, and predictors of intracranial hemorrhage in adult patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a systematic and narrative review. Front Neurol 9:548, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalbhenn J, Wittau N, Schmutz A, Zieger B, Schmidt R: Identification of acquired coagulation disorders and effects of target-controlled coagulation factor substitution on the incidence and severity of spontaneous intracranial bleeding during veno-venous ECMO therapy. Perfusion 30:675–682, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, Chuich T, Dreyfus I, Driggin E, Der Nigoghossian C, Ageno W, Madjid M, Guo Y, et al. : COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol 75(23):2950–2973, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B, Chuich T, Laracy J, Biondi-Zoccai G, Brown TS, Der Nigoghossian C, Zidar DA, Haythe J, et al. : Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 75(18):2352–2371, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorusso R, Barili F, Di Mauro M, Gelsomino S, Parise O, Rycus PT, Maessen J, Mueller T, Muellenbach R, Belohlavek J, et al. : In-hospital neurologic complications in adult patients undergoing venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: results from the extracorporeal life support organization registry. Crit Care Med 44(10):e964–e972, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Weyhern CH, Kaufmann I, Neff F, Kremer M: Early evidence of pronounced brain involvement in fatal COVID-19 outcomes. Lancet 395(10241):e109, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, Hong C, Zhou Y, Wang D, et al. : Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol 77(6):683–690, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teuwen LA, Geldhof V, Pasut A, Carmeliet P: COVID-19: the vasculature unleashed. Nat Rev Immunol 20(7):389–391, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kowalewski M, Fina D, Słomka A, Raffa GM, Martucci G, LoCoco V, DePiero ME, Ranucci M, Suwalski P, Lorusso R: COVID-19 and ECMO: the interplay between coagulation and inflammation-a narrative review. Crit Care 24(1):205, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poissy J, Goutay J, Caplan M, Parmentier E, Duburcq T, Lassalle F, Jeanpierre E, Rauch A, Labreuche J, Susen S: Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19: awareness of an increased prevalence. Circulation 142(2):184–186, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J: Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med 46(5):846–848, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Millar JE, Fanning JP, McDonald CI, McAuley DF, Fraser JF: The inflammatory response to extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO): a review of the pathophysiology. Crit Care 20(1):387, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malfertheiner MV, Pimenta LP, von Bahr V, Millar J, Obonyo N, Suen JY, Pellegrino V, Fraser JF: Acquired von Willebrand syndrome in respiratory extracorporeal life support: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Resusc 19(suppl 1):45–52, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rungatscher A, Tessari M, Stranieri C, Solani E, Linardi D, Milani E, Montresor A, Merigo F, Salvetti B, Menon T, et al. : Oxygenator is the main responsible for leukocyte activation in experimental model of extracorporeal circulation: a cautionary tale. Mediators Inflamm 2015:484979, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sklar MC, Sy E, Lequier L, Fan E, Kanji HD: Anticoagulation practices during venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for respiratory failure. A systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc 13(12):2242–2250, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aubron C, McQuilten Z, Bailey M, Board J, Buhr H, Cartwright B, Dennis M, Hodgson C, Forrest P, McIlroy D, et al. : Low-dose versus therapeutic anticoagulation in patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a pilot randomized trial. Crit Care Med 47(7):e563–e571, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carter KT, Kutcher ME, Shake JG, Panos AL, Cochran RP, Creswell LL, Copeland H: Heparin-sparing anticoagulation strategies are viable options for patients on veno-venous ECMO. J Surg Res 243:399–409, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osho AA, Moonsamy P, Hibbert KA, Shelton KT, Trahanas JM, Attia RQ, Bloom JP, Onwugbufor MT, D’Alessandro DA, Villavicencio MA, et al. : Veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for respiratory failure in COVID-19 patients: early experience from a major academic medical center in North America. Ann Surg 272(2):e75–e78, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.