Abstract

Introduction

Basosquamous carcinoma is an uncommon subtype of basal cell carcinoma (BCC), characterized by aggressive local growth and metastatic potential, that mainly develops on the nose, perinasal area, and ears, representing 1.2–2.7% of all head-neck keratinocyte carcinomas. Although systemic therapy with hedgehog inhibitors (HHIs) represents the first-line medical treatment in advanced BCC, to date, no standard therapy for advanced basosquamous carcinoma has been established. Herein, we reported a case series of patients affected by locally advanced basosquamous carcinomas, who were treated with HHIs.

Case Presentation

Data of 5 patients receiving HHIs for locally advanced basosquamous carcinomas were retrieved (2 women and 3 males, age range: 63–89 years, average age of 77 years). Skin lesions were located on the head-neck area; in particular, 4 tumors involved orbital and periorbital area and 1 tumor developed in the retro-auricular region. A clinical response was obtained in 3 out of 5 patients (2 partial responses and 1 complete response), while disease progression was observed in the remaining 2 patients. Hence, therapy was interrupted, switching to surgery or immunotherapy.

Conclusion

Increasing evidence suggests considering HHIs for large skin tumors developing in functionally and cosmetically sensitive areas, in patients with multiple comorbidities, although their use for basosquamous carcinoma require more exploration, large cohort populations, and long follow-up assessment.

Keywords: Basosquamous carcinoma, Sonic hedgehog pathway inhibitors, Vismodegib, Sonidegib, Clinical dermatology

Introduction

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common keratinocyte carcinoma in fair-skinned individuals worldwide [1]. According to the current WHO classification, the histopathologic BCC subtypes are stratified by the risk of recurrence into low risk (nodular, superficial, pigmented, infundibulocystic, fibroepithelial) and high risk (basosquamous, sclerosing/morphoeic, infiltrating, sarcomatoid differentiation, micronodular) [1].

Basosquamous carcinoma (BSC), also referred as metatypical BCC, is an uncommon subtype, characterized by aggressive local growth and metastatic potential that mainly develops on the nose, perinasal area, and ears, representing 1.2–2.7% of all head-neck keratinocyte carcinomas [2]. Systemic therapy with hedgehog inhibitors (HHIs) represent the first-line medical treatment in advanced BCC but seems to be less effective on BSC, and to date, no standard therapy for advanced BSC has been established [3, 4].

Herein, we reported a case series of patients affected by locally advanced (la) BSCs, who were treated with HHIs. We included patients with histopathological-confirmed BSC, who started therapy with HHIs at the A. Gemelli University Polyclinic – Rome, from January 2021 to January 2023. Data were obtained from the patient medical records and included demographic and epidemiological details, features of the tumor, imaging/radiologic findings, and histopathological diagnosis (Table 1). Patients included in the study signed the informed consent for the disclosure of personal clinical data and images. The CARE Checklist has been completed by the authors for this case report, attached as online supplementary material (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000535506).

Table 1.

Main clinical features, therapy, and tumor response in patients with laBSC

| Patient | Age, years | Sex | Body location | Size of tumor, cm | Therapy | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 89 | F | Lower eyelid | 4.0 × 2.4 | HHIs | PR |

| 2 | 72 | F | Orbital cavity | 1.5 × 2.3 | HHIs | DP |

| 3 | 63 | M | Lateral canthus, tarsal conjunctiva | 1 × 0.8 | HHIs | CR |

| 4 | 73 | M | Medial canthus, lower and upper eyelids | 1.8 × 0.74 | HHIs, surgery | DP |

| 5 | 89 | M | Retroauricular area | 2.4 × 1.7 | HHIs | PR |

F, female; M, male; PR, partial response; DP, disease progression; CR, complete response; laBCC, locally advanced basosquamous carcinoma.

Case Report

Five patients with laBSCs were retrieved (2 women and 3 males, age range: 63–89 years, average age of 77 years). The histopathological slides were retrospectively re-evaluated to confirm diagnosis. BSC lesions were located on the head-neck area; in particular, 4 tumors involved the orbital and periorbital area and 1 tumor developed in the retro-auricular region (Table 1). All 4 BSCs of the ocular area caused functional deficit related to the invasion of the local structures. Only 1 patient had a history of previous BCCs, 1 had never received any therapy, while 4 had previously undergone multiple surgical excisions. A clinical response was obtained in 3 out of 5 patients (2 partial responses [PRs] and 1 complete response [CR]), while disease progression (DP) was observed in the remaining 2 patients. Hence, therapy with HHIs was interrupted, switching to surgery (n = 1) or immunotherapy with anti-PD1 (n = 1). Patients who experienced DP had previously undergone multiple surgical excisions with recurrences, and in both, worsening of the disease was already evident after 6 months of therapy with HHIs. Details of each patient case are reported as following.

Patient #1

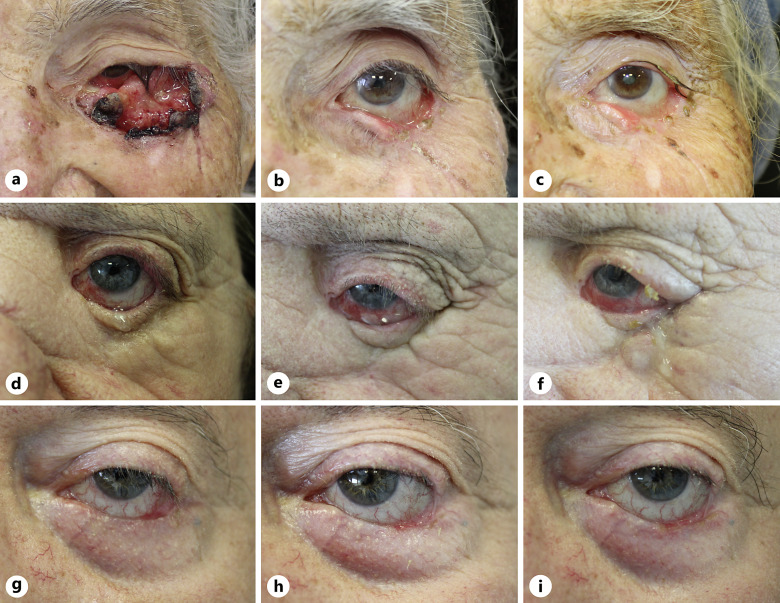

An 89-year-old female was examined for an ulcerated lesion of the left lower eyelid extending from the medial to lateral canthus. The lesion was surgical excised by the ophthalmologist, and histological report documented an ulcerated BSC with desmoplastic features. Local recurrence occurred just 1 month after surgery (Fig. 1a). A head-neck magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed the presence of a lesion with irregular margins (4.0 × 2.4 cm) in correspondence of the lower portion of the left orbit, of the eyelid, and the zygomatic process that invaded the intraconal cellulo-adipose portion without a plane of cleavage with the lower portion of the eyeball and with the insertion of the inferior rectus muscle. Due to disease recurrence, the multidisciplinary team decided to initiate therapy with sonidegib 200 mg per day. After 4 months of treatment, a PR was appreciated with an 80% reduction of the neoplastic mass (Fig. 1b); adverse events including grade II nausea and vomiting led to the treatment schedule of sonidegib 200 mg every other day. After 12 months of alternate daily dose, an excellent response with a reduction of 90% of tumor size was observed (Fig. 1c), with persistence of the same moderate-grade adverse reactions (grade II nausea and vomiting), easily managed. The patient is currently on therapy.

Fig. 1.

Clinical images of laBSCs involving the ocular area treated with sonidegib: an ulcerated plaque with superficial crusts, extending from the medial to lateral canthus (a), showing a clinical response after 4 months of therapy (b), maintained after 12 months of therapy (c); disease recurrence manifesting only with conjunctival hyperemia (d), with no clinical improvement after 6 months of therapy (e), developing a firm nodular lesion on the infraorbital region after 12 months of therapy (f); tumor enlarging on the lower eyelid margin and lateral canthus (g) that exhibits significant improvement after 12 months of therapy (h) and after 18 months of therapy (i).

Patient #2

A 72-year-old female presented with a recurrent BSC infiltrating the left orbit (Fig. 1d). Five years earlier, she had undergone surgery for a left palpebral, histopathologically confirmed BSC, with sequential radiotherapy. Head-neck MRI showed a coarse area (1.5 × 2.3 cm) in the inferior-median portion of the left orbit, in contiguity with the orbit not separated from the inferior rectus muscle.

Since the patient had severe comorbidities (i.e., cryptogenic liver cirrhosis with chronic encephalopathy, chronic nephropathy, type II diabetes mellitus, etc.), surgery and radiotherapy were considered not feasible by the multidisciplinary team, and sonidegib 200 mg/day was started. After 6 months of treatment, MRI of the head-neck area did not find significant changes compared to baseline (Fig. 1e). No drug-related adverse events were referred. At follow-up after 12 months of therapy, a firm skin nodular lesion measuring 1.5 × 1.5 cm on the left infraorbital region was clinically appreciable (Fig. 1f). Digital imaging revealed a solid area in the left orbital cavity encompassing the extrinsic muscles of the ocular globe and inferior and lateral rectus. The mass eroded the inferior wall of the orbit and partly the zygomatic bone, as well as infiltrating the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the zygomatic region. Mild drug-related adverse events were referred (grade I nausea and muscle cramps). Considering the clinical/radiological progression of the disease, the case was discussed in the multidisciplinary tumor board, giving indication to start therapy with cemiplimab.

Patient #3

A 63-year-old male patient was referred to our department by the ophthalmologist for a BSC infiltrating the external canthus and the inferior tarsal conjunctiva of the left eye (Fig. 1g). No therapy was previously administered, and the patient had mild comorbidities (hypertension, hypothyroidism). Therapy with sonidegib 200 mg/day was started, achieving a complete clinical response after 6 months; mild adverse events (grade I alopecia, ageusia, muscle cramps) led to a reduction of dosage to 200 mg every other day. After 12 months of therapy, the disease was stable with persistence of the drug-related adverse events (Fig. 1h). At 18 months of therapy, there was no disease recurrence (Fig. 1i), and an incisional biopsy performed to confirm CR resulted in healthy scar tissue. Treatment with HHI was therefore withdrawn, and adverse events resolved 3 months later. After a follow-up period of 6 months, no recurrence has been observed.

Patient #4

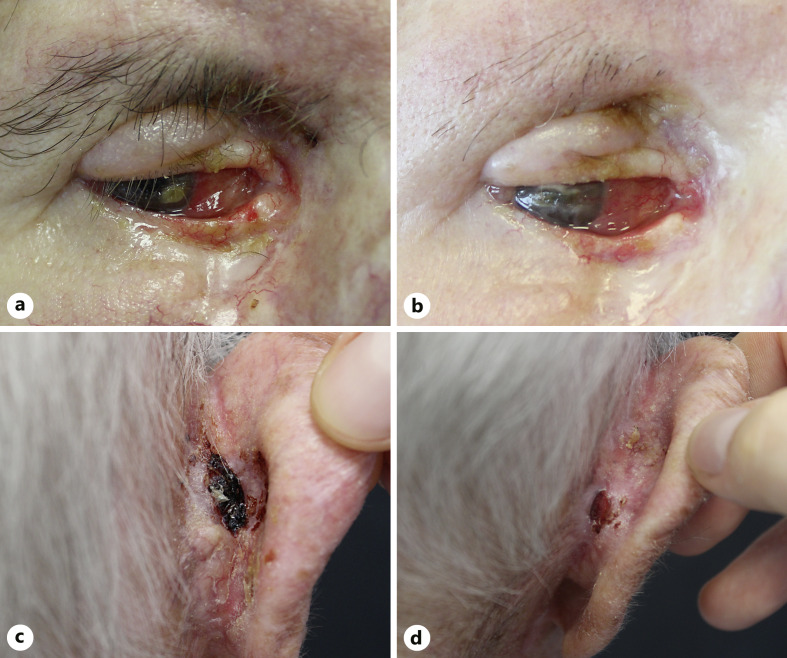

A 73-year-old male patient was evaluated for an eroded plaque that invaded the medial canthus and lower and upper eyelids of the right eye and dislocated the right ocular bulb laterally (Fig. 2a). An incisional biopsy with histological examination was diagnostic of BSC, with features of BCC with squamous metaplasia. Patient medical history revealed multiple surgical excisions and relapsing BCC of the lower right eyelid area in the last 20 years. CT of the skull revealed thickening of the tissue along the superomedial orbital wall, which encompasses the inferior oblique muscle. The tumor was close to the optic nerve, although maintaining a cleavage plane. The decision of the multidisciplinary team was to preserve the ocular bulb delaying surgery. Hence, therapy with sonidegib 200 mg per day was started, and after 6 months of treatment, partial clinical response was obtained (Fig. 2b), with mild-grade adverse events (grade I alopecia and muscle cramps). However, CT showed a slight volumetric increase of the tissue on the posterolateral side, with no cleavage plane with the optic nerve, which was displaced medially. Sonidegib was interrupted, and the patient was then treated with orbital exenterations.

Fig. 2.

Clinical images of a laBSCs involving the ocular area and the retro-auricolar area treated with sonidegib: tumor extending on the medial canthus and lower and upper eyelids (a), not showing clinical improvement after 6 months of therapy (b); an ulcerated crusted plaque with irregular margin invading the posterior area of the auricle (c), with clinical response after 3 months of therapy (d).

Patient #5

An 89-year-old male presented with numerous BCCs localized on the head-neck area. One of these lesions was an ulcerated, bleeding BSC (2.4 × 1.7 cm) located on the right retro-auricular area (Fig. 2c). Comorbidities included hypertension and atrial fibrillation on anticoagulant therapy. Given the presence of multiple skin lesions and the complexity of surgical reconstruction, sonidegib 200 mg per day was started, achieving a PR after 3 months, with a reduction of approximately 50% of the target lesion (Fig. 2d) and other BCCs. The patient then discontinued therapy due to adverse events (ageusia and elevation of serum liver enzyme values).

Discussion

Herein, we reported the use of HHIs for the treatment of laBSC not amenable to surgery or radiation therapy. Therapy with HHIs as second-line in laBCC is a well-established practice, with real-life studies showing an ORR of about 76.7% (95% CI: 82.3–68.7) for all histological subtypes, and an excellent tolerability profile [4]. However, a few case reports described the efficacy of HHIs for treatment of laBSC, with contrasting results and increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma development [5–8].

In this series, sonidegib was effective in 3 out of 5 patients, with a PR after 3–4 months in 2 patients, and a CR after 6 months in 1 patient. Disease progression observed in the remaining 2 patients led to withdrawn sonidegib, switching to immunotherapy with anti-PD1 (n = 1) or proceeding to orbital exenteration (n = 1). It might be reasonable to hypothesize drug resistance of the squamous component as a driver of DP that recently occurred in a single case where sonidegib was used for multiple BSCs in a neoadjuvant setting [6].

Although the real application of HHIs for aggressive tumors like BCSs require more exploration, large cohort populations, and long follow-up assessment, increasing evidence suggests considering these drugs for large skin tumors developing in functionally and cosmetically sensitive areas, in patients with multiple comorbidities [3, 5–7]. Herein, sonidegib was well tolerated in all cases, and the occurrence of mild to moderate adverse events was controlled with dose reduction, without a negative impact of its efficacy.

Statement of Ethics

A study approval statement was not required for this study in accordance with local/national guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of the details of their medical case and any accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Peris has received consulting fees and honoraria unrelated to this work from AbbVie, Almirall, Biogen, Celgene, Janssen Galderma, Novartis, Lilly, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Sandoz, Sanofi, and Sun Pharma; All the other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Funding Sources

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author Contributions

E.B., S.C., and G.P. contributed to the conception, design, and drafting the work; A.P.I. contributed to interpretation of data for the work; A.PA., A.D.S., and K.P. reviewed it critically; and K.P. made approval of the version to be published. All the authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding Statement

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy but are available from the corresponding author (S.C.) upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Peris K, Fargnoli MC, Garbe C, Kaufmann R, Bastholt L, Seguin NB, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guidelines. Eur J Cancer. 2019;118:10–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Garcia C, Poletti E, Crowson AN. Basosquamous carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(1):137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fotiadou C, Apalla Z, Lazaridou E. Basosquamous carcinoma: a commentary. Cancers. 2021;13(23):6146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mannino M, Piccerillo A, Fabbrocini G, Quaglino P, Argenziano G, Dika E, et al. Clinical characteristics of an Italian patient population with advanced BCC and real-life evaluation of hedgehog pathway inhibitor safety and effectiveness. Dermatology. 2023;239(6):868–76. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Toffoli L, Agozzino M, di Meo N, Zalaudek I, Conforti C. Locally advanced basosquamous carcinoma: our experience with sonidegib. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(6):e15436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dika E, Melotti B, Comito F, Tassone D, Baraldi C, Campione E, et al. Neoadjuvant treatment of basosquamous carcinomas with Sonidegib: an innovative approach. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32:2038–9. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Apalla Z, Giakouvis V, Gavros Z, Lazaridou E, Sotiriou E, Bobos M, et al. Complete response of locally advanced basosquamous carcinoma to vismodegib in two patients. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29(1):102–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gambichler T, Stricker I, Neid M, Tannapfel A, Susok L. Impressive response to four cemiplimab cycles of a sonidegib-resistant giant basosquamous carcinoma of the midface. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(6):e490–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy but are available from the corresponding author (S.C.) upon reasonable request.