Abstract

Background & Aims

Type I interferon (T1IFN) signalling is crucial for maintaining intestinal homeostasis. We previously found that the novel T1IFN, IFNε, is highly expressed by epithelial cells of the female reproductive tract, where it protects against pathogens. Its function has not been studied in the intestine. We hypothesize that IFNε is important in maintaining intestinal homeostasis.

Methods

We characterized IFNε expression in mouse and human intestine by immunostaining and studied its function in the dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) colitis model using both genetic knockouts and neutralizing antibody.

Results

We demonstrate that IFNε is expressed in human and mouse intestinal epithelium, and expression is lost in inflammation. Furthermore, we show that IFNε limits intestinal inflammation in mouse models. Regulatory T cell (Treg) frequencies were paradoxically decreased in DSS-treated IFNε-/- mice, suggesting a role for IFNε in maintaining the intestinal Treg compartment. Colitis was ameliorated by transfer of wild-type Tregs into IFNε-/- mice. This demonstrates that IFNε supports intestinal Treg function.

Conclusions

Overall, we have shown IFNε expression in intestinal epithelium and its critical role in gut homeostasis. Given its known role in the female reproductive tract, we now show IFNε has a protective role across multiple mucosal surfaces.

Keywords: Type I Interferons, Interferon Epsilon, Intestinal Inflammation, Colitis

Graphical abstract

Summary.

The novel type I interferon IFNε is expressed in human intestinal epithelium and shows a critical role in gut homeostasis. Its expression pattern makes it a promising new therapeutic agent for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease.

The intestine maintains a delicate balance between recognition of pathogens, while tolerating commensal microorganisms and food antigens. Disruption of this balance can lead to chronic inflammation and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) encompassing ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD).1 Tonic type I interferon (T1IFN) production has been implicated in maintaining intestinal homeostasis,2 and T1IFNs have been used to treat IBD with mixed success.3, 4, 5 The T1IFN family is a large family of pleiotropic cytokines and consists of 14 interferon alpha (IFNα) subtypes and of IFNβ, IFNε, IFNκ, IFNτ, and IFNω.6 All T1IFNs signal through the type I IFN receptors (IFNAR), which consists of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2, and are ubiquitously expressed.

T1IFNs contribute to the maintenance of epithelial barrier function,7, 8, 9 and IFNAR signalling has protective effects in experimental colitis, because IFNAR1-/- mice are more susceptible to dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis10 and to induction of colitis in the T-cell adoptive transfer model.11 IFNAR signalling is important for maintaining intestinal regulatory T cell (Treg) function and Treg numbers in inflamed intestine to limit intestinal damage in experimental colitis.11,12 To date, it is not known which member of the T1IFNs is responsible for these protective effects. Administration of IFNβ 5 and CpG-ODN–induced expression of IFNα/β 10 suppressed the severity of DSS-induced colitis. In contrast to this, pretreatment with an IFNβ-expressing lactobacillus resulted in increased DSS colitis severity.4 As mentioned, T1IFN, namely IFNα and IFNβ, have been used as treatments in human IBD, with conflicting results.3,5 Moreover, an elevated T1IFN signature has been described in intestinal biopsies of active IBD patients,13,14 contributing to epithelial cell death.13 These contradictory findings might be caused by the role T1IFNs play in different stages of intestinal inflammation, with a protective effect of T1IFN signalling in the acute phase of DSS-induced colitis and a proinflammatory role of T1IFNs during the recovery phase.15 Furthermore, effects of T1IFNs may be dose dependent. For example, although basal T1IFN signalling is considered protective, high levels of IFNβ induced after lipopolysaccharide injection result in mortality in a mouse model for sepsis,16 and the chronic elevated ISG signature in Trex-/- mice drives autoimmunity.17 In addition, multiple sclerosis patients treated with low dose (30 μg) IFNβ showed lower loss in brain volume than patients treated with a high dose (250 μg).18 This highlights an incomplete understanding of T1IFN signalling in maintaining intestinal homeostasis.

We previously discovered and characterized the unique T1IFN family member IFNε 19, 20, 21 and showed that IFNε is highly and constitutively expressed by epithelial cells of the female reproductive tract,19,22 where it is involved in protection against sexually transmitted pathogens.19,23,24 Although the expression of IFNε is most abundant in the female reproductive tract in mice, expression has also been shown in epithelial cells of other tissues,25 for example in rhesus macaques, where IFNε protein expression was detected in the epithelium of the jejunum and rectum,26 indicating that IFNε will likely play a role in local immune responses in the intestine.

Here we showed IFNε is expressed in human and mouse intestinal epithelium and that IFNε prevents exacerbated intestinal inflammation in the DSS colitis model by maintaining the colon FoxP3+ Treg compartment. The colitis was rescued by the transfer of wild-type (WT) Tregs into IFNε -/- mice. We show for the first time that IFNε is important in modulating intestinal immune responses and maintaining intestinal homeostasis, making IFNε a promising candidate for treatment of IBD.

Results

IFNε Is Expressed in Human and Mouse Intestinal Epithelium

To characterize IFNε expression in human large intestine, rectal biopsy samples were collected from pediatric IBD and control patients for immunohistochemical staining. IFNε expression was detected in epithelium of control (Figure 1A, upper panel) and pediatric IBD (Figure 1A, lower panel) samples, while staining was low to absent in lamina propria. There was no significant difference in expression between control and pediatric IBD samples (P = .43); however, sample size was low (n = 5 control and n = 7 IBD patients).

Figure 1.

IFNε expression in human and mouse colon. Human colon biopsies from pediatric control and IBD patients were stained for IFNε or isotype control by immunohistochemistry. IFNε appears brown. Graph shows IFNε staining intensity in control and IBD patients (A). Mouse control and inflamed colon (DSS) were stained for IFNε by immunofluorescence. Colons from IFNε-/- mice were used as negative controls. Graphs show IFNε staining intensity in control and DSS-treated colon (B). Staining intensities were determined using Aperio ImageScope software. Data are depicted as mean staining intensity + standard error of the mean and include individual data. ∗P < .05 by Mann-Whitney U test.

To study whether IFNε plays a role in intestinal immunity, we made use of a mouse model for intestinal inflammation, DSS colitis. First, we confirmed IFNε was expressed in mouse intestine. Distal colon samples were collected from both untreated control and DSS-treated WT and Ifnε-/- mice for immunofluorescence. IFNε was detected in intestinal epithelium of control WT mice but was absent in Ifnε-/- mice. (Figure 1B, top panels). After DSS treatment, IFNε expression was significantly decreased in WT mice (Figure 1B, bottom panels and graph). This may have been caused by destruction of epithelial cells, the cell type responsible for IFNε production.

Intestinal IFNε Expression Prevents Exacerbated Intestinal Inflammation

To study the role of IFNε in modulating intestinal inflammation, WT and Ifnε-/- mice were treated with 2.5% (w/v) DSS in drinking water for 7 days. Lack of IFNε expression resulted in significantly more severe clinical symptoms, with a greater loss in body weight (Figure 2A), more pronounced shortening of the colon (an average of 4.8 cm in WT and an average of 4.0 cm in IFNε-/- colon), a hallmark of experimental colitis (Figure 2B) and a higher clinical score from day 4 onward (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Role for IFNε in intestinal inflammation in the DSS colitis model. WT (n = 8) and IFNε-/- mice (n =8) were treated with DSS in drinking water for 7 days and monitored for development of clinical symptoms. Body weight as percentage of starting weight (A). Colon length at day 7 after start of DSS treatment. Dotted line indicates average colon length of untreated mice (B). Disease activity index (C). Representative pictures of colon H&E staining of untreated control colon (top panel) and after DSS treatment (lower panel). Graph displays histopathology after DSS treatment (D). WT mice were treated intraperitoneally with our IFNε-neutralizing antibody (n = 10) or with isotype control (n = 10) and received DSS in drinking water. Body weight as percentage of starting weight (E). Colon length at day 7 after start of DSS treatment. Dotted line indicates average colon length of untreated mice (F). Disease activity index (G). Histopathology after DSS treatment (H). Data are depicted as mean + standard error of the mean and include individual data (B–D). ∗P < .05,∗∗P < .01,∗∗∗P < .001 by Mann-Whitney U test.

To characterize histopathology in colon after DSS treatment, we first established whether there were basal differences in colon morphology between WT and Ifnε-/- mice. Untreated control WT and Ifnε-/- colon showed no gross morphologic differences (Figure 2D, top panels). After DSS treatment Ifnε-/- colons showed significantly more severe histopathology, with more severe inflammation, more pronounced crypt loss, and a near complete destruction of the epithelial layers (Figure 2D, lower panels and summarizing graph).

To confirm that any role observed for IFNε in limiting intestinal inflammation is not due to developmental differences between WT and Ifnε-/- mice, WT mice were treated with an in-house anti-mouse IFNε-neutralizing antibody, ME2.19 Colitis symptoms were milder than in the experiment described in Figure 2A–D; however, mice clearly exhibited colitis symptoms. Although weight loss (Figure 2E) and colon length (Figure 2F) did not significantly change after neutralizing IFNε, clinical symptoms (Figure 2G) and histopathology (Figure 2H) were more severe, confirming the role for IFNε in protection against colitis.

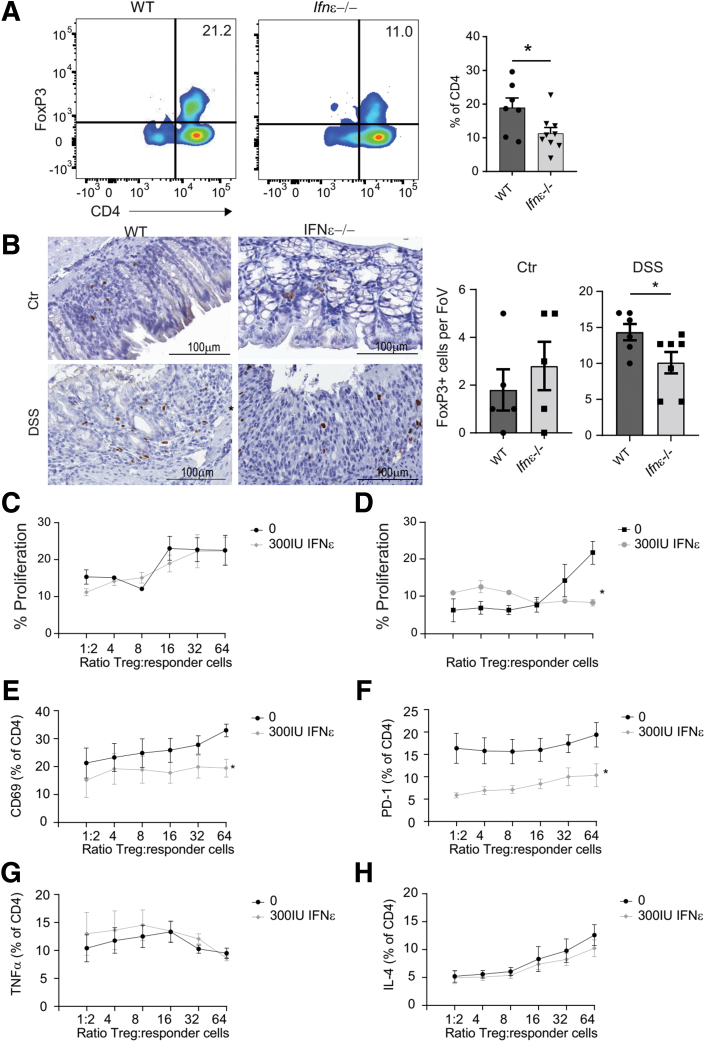

IFNε Maintains Intestinal Treg and Modulates Treg Function In Vitro

Because it is known that IFNAR signalling is important for maintaining the intestinal Treg compartment and these cells are important in maintaining intestinal homeostasis,11,12 we characterized FoxP3+ T-cell frequencies in colons of WT and Ifnε-/- mice after DSS treatment. Frequencies and absolute numbers of FoxP3+ T cells were significantly reduced in Ifnε-/- colon (Figure 3A and B), suggesting IFNε is involved in maintaining FoxP3+ cells in intestinal tissue.

Figure 3.

Modulation of Treg by IFNε. WT and IFNε-/- mice were treated with DSS in drinking water for 7 days, and colon FoxP3+ Treg were analyzed by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry. Representative picture of FoxP3 plotted against CD4 in isolated colon immune cells of WT (left) and IFNε-/- mice after DSS treatment. Graphs display summary data (A). Representative picture of FoxP3 immunohistochemistry staining in colon of WT (left) and IFNε-/- mice after DSS treatment. Graphs show numbers of FoxP3+ cells per field of view for untreated control colon (left) and after DSS treatment (right; B). WT Treg were cocultured with CFSE-labelled IFNAR1-/- CD4 responder T cells (C, E–H), or IFNAR1-/- Treg were cocultured with CFSE-labelled WT CD4 responder T cells (D). All were stimulated with CD3/CD28 beads and interleukin 2. Proliferation was characterized by measuring CFSE dilution in IFNAR1-/- responder cells cocultured with WT Treg in a ratio ranging from 1:2 to 1:64 (C) and WT responder cells cocultured with IFNAR1-/- Treg in a ratio ranging from 1:2 to 1:64 (D). Cell surface expression of CD69 (E) and PD-1 (F) in IFNAR1-/- responder cells cocultured with WT Treg in a ratio ranging from 1:2 to 1:64. Intracellular expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha (E) and interleukin 4 (F) in IFNAR1-/- responder cells cocultured with WT Treg in a ratio ranging from 1:2 to 1:64. Data are depicted as mean + standard error of the mean and include individual data (A and B). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01,∗∗∗P < .001 by Mann-Whitney U test. Data are depicted as mean + standard error of the mean of 8 mice per genotype (C–H).

Because we observed decreased numbers of FoxP3+ Treg in colons from Ifnε-/- mice after DSS treatment, we asked whether IFNε is important for Treg function. WT CD25+ Treg and carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CSFE)-labelled Ifnar1-/- CD4+ cells were cocultured for 3 days with interleukin 2 and CD3/28 beads and in presence or absence of recombinant murine (rm)IFNε. To characterize direct effects of rmIFNε on responder T cells, Ifnar1-/- CD25+ Treg and WT CSFE-labelled CD4+ cells were cocultured. rmIFNε did not affect Treg capacity to suppress proliferation, because no additional suppression of proliferation was observed when WT Treg and Ifnar1-/- responder T cells were cultured in the presence of 300 IU/mL rmIFNε (Figure 3C). Responder T-cell proliferation was directly suppressed by rmIFNε, because WT responder cells showed decreased proliferation when cultured in the presence of 300 IU/mL rmIFNε (Figure 3D).

We then characterized the phenotype of the responder T cells to see whether rmIFNε affected the capacity of Treg to modulate responder cell phenotype. CD69 expression was significantly decreased when Ifnar1-/- responder cells were cocultured with WT Treg in the presence of 300 IU/mL rmIFNε at all coculture ratios (Figure 3E). In addition, PD-1 expression was significantly suppressed when Ifnar1-/- responder cells were cultured with 300 IU/mL rmIFNε (Figure 3F). Tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 4 expression was not altered in the presence of rmIFNε (Figure 3G). This suggests that rmIFNε directly affects responder T-cell proliferation and, to a certain degree, affects Treg function.

Frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and myeloid cell populations were not significantly different between WT and Ifnε-/- mice (Figure 4A–F). Flow cytometry gating strategies for Figures 3 and 4 are explained in Figure 5 for lymphoid cell populations and in Figure 6 for myeloid cell populations.

Figure 4.

Colon immune cell frequencies in DSS-treated mice. Flow cytometry was performed on colon immune cells after DSS treatment. Gating strategies are shown in Figures 5 and 6. CD4 T cells as percentage of CD45 and expression of PD-1 and CD69 in the CD4 T cell population (A). CD8 T cells as percentage of CD45 (B). Percentage of monocytes (C) and neutrophils (D). Percentage of CD11c+ DC (E). Percentage of CD11b+ and CD11b+CD11c+ MPh and analysis of MHC II expression in these subsets (F). Data are depicted as mean + standard error of the mean of 5 mice per genotype.

Figure 5.

Colon CD4 T-cell gating. For all fluorescence activated cell sorter analysis, doublets were excluded, viable cells were selected, and total immune cells were gated using CD45. CD4 cells were selected and analyzed for PD-1 and CD69 expression as indicated.

Figure 6.

Colon myeloid cell gating strategy. For all fluorescence activated cell sorter analysis, doublets were excluded, viable cells were selected, and total immune cells were gated using CD45. Monocytes and neutrophils were gated on the basis of Ly6C and Ly6G expression. Ly6C- cells were subdivided into MPh and DC populations as indicated.

Colitis Symptoms Are Ameliorated After Treg Transfer in Ifnε-/- Mice

To test whether the reduced numbers of Tregs observed in DSS-treated Ifnε-/- mice contribute to the increased disease severity, we treated Ifnε-/- mice with WT Treg on day 4 after start of DSS treatment at the onset of clinical symptoms. The Treg-treated mice showed ameliorated symptoms as compared with the saline injected mice, with significantly decreased body weight loss (Figure 7A). Treg treatment did not significantly affect shortening of the colon (Figure 7B) but resulted in reduced severity of clinical symptoms on day 7 (Figure 7C) and significantly decreased histopathology (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

Adoptive transfer of Treg to modulate DSS severity of IFNε-/- mice. On day 4 after start of DSS treatment, IFNε-/- mice were intravenously injected with 1 × 106 WT splenic Treg or saline and monitored for development of clinical symptoms. Body weight as percentage of starting weight (A). Colon length at day 7 after start of DSS treatment. Dotted line indicates average colon length of untreated mice (B). Disease activity index (C). Representative pictures of H&E-stained colon of Treg-treated and saline-treated mice; graphs show summary data (D). Data are depicted as mean + standard error of the mean of n = 8 mice per treatment group and include individual data (B–D). ∗P < .05,∗∗P < .01,∗∗∗P < .001 by Mann-Whitney U test.

Discussion

In this study we show for the first time that IFNε is expressed in epithelial cells of the human and mouse colon and plays a crucial role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis. It has been known for a long time that IFNAR signalling, likely in response to microbial stimuli,2 is important in limiting inflammation in experimental colitis.10,11,15 Low, constitutive IFNβ expression has been described in mouse intestine27 and in lamina propria CD11c+ cells.28 Hence, in the past, the protective effects of IFNAR signalling have been attributed to IFNβ.29,30 However, pretreatment with IFNβ-expressing lactobacillus resulted in more severe colitis4 and STING activation, triggering IFNβ production exacerbates experimental colitis.31 Moreover, treatment of IBD patients with IFNβ1a showed no beneficial effects,32 and there are even reports of patients developing IBD after IFNβ treatment.33,34 In addition, high levels of IFNβ in UC patients was shown to contribute to pathogenesis.14,35 This suggests the response to IFNβ may be dose and timing dependent,15 and that IFNAR signalling in intestinal tissues is incompletely understood.

IFNε remains a relatively poorly understood T1IFN, and its function in the gastrointestinal tract has not been characterized. It is a good candidate T1IFN for the constitutive tonic IFNAR signalling in the gut because of both its exclusively epithelial expression and its known role in the genito-urinary tract. T1IFN signalling is involved in crosstalk between the host, intestinal pathogens, and the microbiome.36,37 The epithelial location of IFNε makes it a likely candidate to facilitate this interaction. The regulation of IFNε expression is an ongoing area of study. In the uterus, it is regulated hormonally, but this is not true in the vagina and cervix,19 and it seems unlikely that hormonal factors affect expression in the gastrointestinal tract. Regardless, its localization to the epithelium suggests a role in the first line of defense against intestinal pathogens and that it possibly interacts with commensal microbiota. In mouse female reproductive tract, IFNε indeed mediates interaction with pathogenic bacteria,19,38 and we have indications it interacts with the vaginal microbiome (unpublished,38). In our studies, we readily detected IFNε expression in epithelium of human and mouse colon. Although we did not observe significant differences between control and IBD samples, IFNε expression was lost in mouse colon after DSS treatment. Lack of a significant difference in human colon samples may be explained by the low sample size and perhaps because there is less destruction of the epithelium in human IBD samples when compared with the mouse DSS samples. IFNε was protective in the DSS colitis model, where treatment with DSS resulted in disruption of the epithelial layer and subsequent translocation of microbiota, resulting in loss of tolerance. While statistically significant in both the IFNε-/- model and with the neutralizing model, the effect on colon length was numerically small (Figure 2B and F).

Tregs are crucial for maintaining intestinal homeostasis, and it has been shown that T1IFN signalling is important for maintaining the intestinal Treg population.11,12 The specific T1IFN involved is not clear. Tonic IFNβ signalling was described in intestine,27 suggesting IFNβ could be involved. However, other studies show inhibitory effects of IFNβ and/or T1IFN signalling on Treg proliferation and function.39, 40, 41, 42 In line with our previous findings,19,21 IFNε directly inhibited effector T-cell proliferation in vitro. Whereas culturing mouse splenocytes in the presence of IFNε resulted in up-regulation of CD69 expression by CD4 T cells,21 when we cocultured WT murine Tregs with Ifnar1-/- responder T cells in the presence of IFNε, we observed decreased expression of CD69, indicating IFNε increased Treg function in vitro. These seemingly conflicting effects on Treg function could be explained by the lower affinity of IFNε for its receptors when compared with IFNα/β.21,38 We postulate that because of the constitutive expression pattern of IFNε and its lower affinity for its receptors, it will not have the toxicity associated with other T1IFN family members,21,38 rather it will provide a basal level of protection.

Increasing intestinal Treg numbers and function has been postulated as a promising strategy to treat IBD.43, 44, 45 IFNε has immunomodulatory properties,19,21,46,47 and whereas we did not observe differences in frequencies of intestinal T cells, B cells, or myeloid cells, we found decreased frequencies of Tregs in our DSS-treated Ifnε-/- mice. This decrease in Tregs was an important driver of disease, because transfer of WT Tregs at disease onset was able to ameliorate clinical symptoms in Ifnε-/- mice.

In summary, this article shows for the first time that IFNε is expressed by epithelial cells in the human and murine colon and in mice is crucial for maintaining intestinal homeostasis and prevents exacerbated inflammation in experimental colitis. Because of its constitutive expression, cellular distribution, and lower affinity for the IFNAR receptor when compared with IFNα/β, we propose IFNε is a highly promising therapeutic candidate for treatment of intestinal inflammation, in particular IBD.

Materials and Methods

Human Ethics and Animal Ethics

This study received ethical approval from the Monash Health Human Research Ethics Committee (Monash Health Ref: 16367A) before commencing. Written and informed patient consent was obtained before tissue collection, and parental/guardian approval was obtained in-lieu if the patient was unable to provide consent.

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with approval from the institutional animal ethics committee and performed using age-matched C57BL/6 mice.

Patient Cohort and Rectal Biopsy Collection

All patients had a clinical indication for a colonoscopy and tissue sample collection. Patient samples were divided into control and IBD samples on the basis of medical history, colonoscopy results, and pathology reports. Table 1 shows a summary of patient demographics. Rectal biopsies were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Five-μm sections were prepared and deparaffinized routinely.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Control (n = 6) | IBD (n = 8) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y (range) | 5–14 | 7–14 |

| Female | 67% | 50% |

| Histologically inflamed | 0% | 75% |

Mice

Six- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 (WT) mice were obtained from Monash Animal Services. Ifnε-/- and Ifnar1-/- mice on a C57BL/6 background were maintained in-house. Animals were housed in groups in individually ventilated and filtered cages under positive pressure in an SPF facility.

Induction and Evaluation of Experimental Colitis

Mice were given 2.5% (weight/volume) DSS (MP Biomedicals; MW 36K-50K) in autoclaved tap water for 7 days. Mice were scored daily for development of clinical symptoms. The disease activity index (DAI) was determined as follows: for loss in body weight, 0 = no loss, 1 = 0%–5%, 2 = 5%–8%, 3 = 8%–15%, 4 = greater than 15%; for faecal consistency, 0 = normal, 1 = pasty stool, 2 = semi-formed stool, 3 = mild diarrhea, 4 = severe diarrhea; for occult blood, 0 = no blood, 1 = mild occult bleeding, 2 = moderate occult bleeding, 3 = blood macroscopically visible. Feces were collected daily from day 0 onward. Mice were killed at day 7 to measure colon length and to collect tissues for postmortem analysis.

To neutralize IFNε in vivo, mice were intraperitoneally injected with 100 μg/mouse of IFNε-neutralizing antibody (ME219) on days 0 and 3. This concentration was based on unpublished pilot experiments performed in mice of similar age. For Treg transfer experiments, 1 × 106 Treg isolated from spleens of WT mice were injected intravenously on day 4.

Fecal Blood Test

To detect occult blood in feces, we made use of the peroxidase activity of hematin, a metabolite of hemoglobin. Fecal pellets were dissolved in water and spotted on nitrocellulose membrane. After air drying, peroxidase activity was detected using 1-Step Ultra TMB-Blotting Solution (Thermo Fisher). The reaction was stopped with tap water.

Histologic Evaluation

Distal colons were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Four-μm sections were prepared and deparaffinized routinely.

Sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and were graded for amount of inflammation, depth of inflammation, and the amount of crypt damage as described previously.48

Immunohistochemistry

To detect IFNε in human colon samples, heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) was performed with 10 mmol/L Trisma acetate and 1 mmol/L EDTA buffer, pH 6.0 in a microwave. IFNε was detected using rabbit anti-IFNε (Prestige Antibodies), and background staining was prevented with CAS block (Invitrogen). Biotinylated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Vector Laboratories) was used as secondary antibody. To stain FoxP3-expressing cells in mouse colon sections, HIER was done using a Biocare decloaking chamber (Biocare) in Tris-EDTA Buffer (10 mmol/L Tris Base, 1 mmol/L EDTA solution, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 9.0) at 110°C for 5 minutes under pressure. FoxP3 was detected with rat anti-mouse FoxP3 (eBioscience). Biotinylated anti-rat immunoglobulin G (Vector Laboratories) was used as secondary antibody. This was followed by incubation with VECTASTAIN Elite ABC-HRP (Vector Laboratories). Color development was performed with liquid DAB+ Substrate (Dako), and slides were counterstained with hematoxylin (Invitrogen) and coverslipped with D.P.X. neutral mounting medium.

Slides were scanned at 20× magnification with an Aperio Scanscope AT Turbo (Leica Biosystems), and intensity of staining was analyzed with Aperio ImageScope software (Leica Biosystems).

Immunofluorescence

HIER was done using a Biocare decloaking chamber in citrate buffer (10 mmol/L trisodium citrate, pH 6.0) at 110°C for 5 minutes under pressure. To detect IFNε protein expression, mouse anti-IFNε (Clone HE70; S. S. Lim, manuscript in preparation) was used at a concentration of 3 μg/mL. Background staining was prevented by using goat serum (Vector Laboratories). Biotinylated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Vector Laboratories) was used as secondary antibody, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488-labelled streptavidin (Invitrogen).

Slides were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidine-2′-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI; Molecular Probes) and coverslipped with fluorescence mounting medium (Agilent).

Slides were scanned at 20× and 40× magnification using an Aperio Scanscope FL (Leica Biosystems) and analyzed with Aperio ImageScope software (Leica Biosystems).

Isolation of Colon Immune Cells

To analyze myeloid and lymphoid immune cells frequencies in inflamed colon, colon was dissected, opened longitudinally, and rinsed with Hank’s balanced salt solution. Tissues were first digested by incubation in Hank’s balanced salt solution (Gibco) supplemented with 10 mmol/L HEPES, 25 mmol/L NaHCO3, 1 mmol/L dithioerythritol, and 10% fetal calf serum to isolate intraepithelial lymphocytes. Supernatants containing lymphocytes were kept on ice to be pooled with leukocytes isolated from lamina propria. Lamina propria cells were isolated by incubating tissues in Hank’s balanced salt solution supplemented with 1.3 mmol/L EDTA, followed by incubation in RPMI supplemented with 5 mmol/L HEPES, 1 mg/mL collagenase type III (Scimar), 2 μg/mL DNase I (Sigma), and 10% fetal calf serum. Cells were isolated by squeezing through a 70-μm filter, and leukocytes were collected using a 66%/44% isosmotic percoll gradient.

Isolation and Culture of Treg and Responder CD4 T Cells

Tregs were isolated from spleens of untreated WT and ifnar1-/- mice using the EasySep Mouse CD25 Regulatory T Cell Positive Selection Kit (STEMCELL Technologies) for isolating CD4+CD25- T cells. Negative fractions were used to isolate CD4+ T cells with EasySep Mouse CD4+ T cell Isolation Kit (STEMCELL Technologies). Both kits were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CD4+ T cells were labelled with CFSE (Molecular Probes), and Tregs and CD4+ T cells were cocultured in 96-well round bottom tissue culture plates in a ratio between 1:2 and 1:64 for 3 days. Anti-CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher), 20 IU/mL rmIL 2, and 0 IU/mL, 100 IU/mL, or 300 IU/mL rmIFNε (produced in-house21) were added to each well. Cells were cultured for 3 days, with 5 μg/mL Brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich) in the last 6 hours.

Flow Cytometry

Viability staining was performed with Zombie Red fixable viability dye (Biolegend) or with LD blue (Thermo Fisher), and Fc receptors were blocked with anti-mouse CD16/32 (eBioscience). Before performing Fc block and surface stain using anti-CD45-BV510 (BD), anti-CD4-BV785 (eBioscience), anti-CD8-APC (BD), anti-CD25-BV650 (Biolegend), anti-Ly6G-PB (Biolegend), anti-CD11b-SB702 (eBiosciences), anti-CD103-PerCP eF710 (eBiosciences), anti-Ly6C-APC eF780 (eBiosciences), anti-CD69-PE (BD), anti-PD-1-PECy7 (eBioscience), anti-MHC II-AF700, (eBioscience), and anti-CD11c-PE Cy7 (eBioscience) were used. Cells were permeabilized and fixed with the Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience) and stained with AF488-labelled anti-FoxP3. Fluorescence minus one samples were used to assist in analysis. Samples were analyzed using a Fortessa X20 flow cytometer and FlowJo V10 software (BD).

Statistical Analysis

Graphs were prepared with GraphPad Prism 9 (Graph Pad Software). Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 28 (IBM), using Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis tests where appropriate.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Monash MHTP FlowCore for assistance with flow cytometry analysis. The authors acknowledge use of the facilities and technical assistance of Monash Histology Platform, Department of Anatomy and Developmental Biology, Monash University. The authors thank Dr San Lim for production and characterisation of IFNε antibodies.

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Eveline de Geus, PhD (Conceptualization: Equal; Data curation: Lead; Formal analysis: Lead; Funding acquisition: Supporting; Investigation: Lead; Writing – original draft: Lead)

Jennifer Volaric (Formal analysis: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting)

Antony Matthews (Generating crucial reagents: Supporting)

Niamh Mangan (Conceptualization: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting)

Janet Chang (Investigation: Supporting)

Joshua Ooi (Methodology: Supporting)

Nicole de Weerd (Conceptualization: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Edward Giles (Conceptualization: Supporting; Funding acquisition: Lead; Project administration: Lead; Supervision: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Lead)

Paul Hertzog (Conceptualization: Supporting; Funding acquisition: Supporting; Supervision: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding These authors disclose the following: EDG and EG are funded by NHMRC Ideas grant number 2003918. EG was supported by a Research Establishment Fellowship from the RACP Foundation, grant number 2021REF0008. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

References

- 1.Bouma G., StroberW The immunological and genetic basis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:521–533. doi: 10.1038/nri1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotredes K.P., Thomas B., Gamero A.M. The protective role of type I interferons in the gastrointestinal tract. Front Immunol. 2017;8:410. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez-Navajas J.M., Lee J., David M., et al. Immunomodulatory functions of type I interferons. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:125–135. doi: 10.1038/nri3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McFarland A.P., Savan R., Wagage S., et al. Localized delivery of interferon-beta by Lactobacillus exacerbates experimental colitis. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neurath M.F. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:329–342. doi: 10.1038/nri3661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hertzog P.J. Overview: type I interferons as primers, activators and inhibitors of innate and adaptive immune responses. Immunol Cell Biol. 2012;90:471–473. doi: 10.1038/icb.2012.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katlinskaya Y.V., Katlinski K.V., Lasri A., et al. Type I interferons control proliferation and function of the intestinal epithelium. Mol Cell Biol. 2016;36:1124–1135. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00988-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McElrath C., Espinosa V., Lin J.D., Peng J., et al. Critical role of interferons in gastrointestinal injury repair. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2624. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22928-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tschurtschenthaler M., Wang J., Fricke C., et al. Type I interferon signalling in the intestinal epithelium affects Paneth cells, microbial ecology and epithelial regeneration. Gut. 2014;63:1921–1931. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katakura K., Lee J., Rachmilewitz D., et al. Toll-like receptor 9-induced type I IFN protects mice from experimental colitis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:695–702. doi: 10.1172/JCI22996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kole A., He J., Rivollier A., et al. Type I IFNs regulate effector and regulatory T cell accumulation and anti-inflammatory cytokine production during T cell-mediated colitis. J Immunol. 2013;191:2771–2779. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S.E., Li X., Kim J.C., et al. Type I interferons maintain Foxp3 expression and T-regulatory cell functions under inflammatory conditions in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:145–154. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flood P., Fanning A., Woznicki J.A., et al. DNA sensor-associated type I interferon signaling is increased in ulcerative colitis and induces JAK-dependent inflammatory cell death in colonic organoids. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2022;323:G439–G460. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00104.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ostvik A.E., Svendsen T.D., Granlund A.V.B., et al. Intestinal epithelial cells express immunomodulatory ISG15 during active ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:920–934. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rauch I., Hainzl E., Rosebrock F., et al. Type I interferons have opposing effects during the emergence and recovery phases of colitis. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44:2749–2760. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Weerd N.A., Vivian J.P., Nguyen T.K., et al. Structural basis of a unique interferon-beta signaling axis mediated via the receptor IFNAR1. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:901–907. doi: 10.1038/ni.2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gall A., Treuting P., Elkon K.B., et al. Autoimmunity initiates in nonhematopoietic cells and progresses via lymphocytes in an interferon-dependent autoimmune disease. Immunity. 2012;36:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan O., Bao F., Shah M., et al. Effect of disease-modifying therapies on brain volume in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results of a five-year brain MRI study. J Neurol Sci. 2012;312:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fung K.Y., Mangan N.E., Cumming H., et al. Interferon-epsilon protects the female reproductive tract from viral and bacterial infection. Science. 2013;339:1088–1092. doi: 10.1126/science.1233321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardy M.P., Owczarek C.M., Jermiin L.S., et al. Characterization of the type I interferon locus and identification of novel genes. Genomics. 2004;84:331–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stifter S.A., Matthews A.Y., Mangan N.E., et al. Defining the distinct, intrinsic properties of the novel type I interferon, IFN. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:3168–3179. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.800755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourke N.M., Achilles S.L., Huang S.U., et al. Spatiotemporal regulation of human IFNepsilon and innate immunity in the female reproductive tract. JCI Insight. 2022 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.135407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Minambres A., Eid S.G., Mangan N.E., et al. Interferon epsilon promotes HIV restriction at multiple steps of viral replication. Immunol Cell Biol. 2017;95:478–483. doi: 10.1038/icb.2016.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coldbeck-Shackley R.C., Romeo O., Rosli R., et al. Constitutive expression and distinct properties of IFN-epsilon protect the female reproductive tract from Zika virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2023 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010843. (accepted for publication) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao F.R., Wang W., Zheng Q., et al. The regulation of antiviral activity of interferon epsilon. Front Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1006481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demers A., Kang G., Ma F., et al. The mucosal expression pattern of interferon-epsilon in rhesus macaques. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;96:1101–1107. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3A0214-088RRR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lienenklaus S., Cornitescu M., Zietara N., et al. Novel reporter mouse reveals constitutive and inflammatory expression of IFN-beta in vivo. J Immunol. 2009;183:3229–3236. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chirdo F.G., Millington O.R., Beacock-Sharp H., et al. Immunomodulatory dendritic cells in intestinal lamina propria. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1831–1840. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abe K., Nguyen K.P., Fine S.D., et al. Conventional dendritic cells regulate the outcome of colonic inflammation independently of T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17022–17027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708469104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofmann C., Dunger N., Grunwald N., et al. T cell-dependent protective effects of CpG motifs of bacterial DNA in experimental colitis are mediated by CD11c+ dendritic cells. Gut. 2010;59:1347–1354. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.193177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin G.R., Blomquist C.M., Henare K.L., et al. Stimulator of interferon genes (STING) activation exacerbates experimental colitis in mice. Sci Rep. 2019;9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50656-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Musch E., Andus T., Kruis W., et al. Interferon-beta-1a for the treatment of steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:581–586. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodrigues S., Magro F., Soares J., et al. Case series: ulcerative colitis, multiple sclerosis, and interferon-beta 1a. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:2001–2003. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schott E., Paul F., Wuerfel J.T., et al. Development of ulcerative colitis in a patient with multiple sclerosis following treatment with interferon beta 1a. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3638–3640. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i26.3638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flood P., Fanning A., Woznicki J.A., et al. DNA sensor associated type I interferon signalling is increased in ulcerative colitis and induces JAK-dependent inflammatory cell death in colonic organoids. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2022 doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00104.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pott J., Stockinger S. Type I and III interferon in the gut: tight balance between host protection and immunopathology. Front Immunol. 2017;8:258. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erttmann S.F., Swacha P., Aung K.M., et al. The gut microbiota prime systemic antiviral immunity via the cGAS-STING-IFN-I axis. Immunity. 2022;55:847–861 e10. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2022.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marks Z.R.C., Campbell N., deWeerd N.A., et al. Properties and functions of the novel type I interferon epsilon. Semin Immunol. 2019;43 doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2019.101328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srivastava S., Koch L.K., Campbell D.J. IFNalphaR signaling in effector but not regulatory T cells is required for immune dysregulation during type I IFN-dependent inflammatory disease. J Immunol. 2014;193:2733–2742. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Srivastava S., Koch M.A., Pepper M., et al. Type I interferons directly inhibit regulatory T cells to allow optimal antiviral T cell responses during acute LCMV infection. J Exp Med. 2014;211:961–974. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee S., Hirota K., Schuette V., et al. Attenuation of regulatory T cell function by type I IFN signaling in an MDA5 gain-of-function mutant mouse model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022;629:171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gangaplara A., Martens C., Dahlstrom E., et al. Type I interferon signaling attenuates regulatory T cell function in viral infection and in the tumor microenvironment. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Canavan J.B., Scotta C., Vossenkamper A., et al. Developing in vitro expanded CD45RA+ regulatory T cells as an adoptive cell therapy for Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2016;65:584–594. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-306919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clough J.N., Omer O.S., Tasker S., et al. Regulatory T-cell therapy in Crohn’s disease: challenges and advances. Gut. 2020;69:942–952. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giuffrida P., Cococcia S., Delliponti M., et al. Controlling gut inflammation by restoring anti-inflammatory pathways in inflammatory bowel disease. Cells. 2019;8 doi: 10.3390/cells8050397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Day S.L., Ramshaw I.A., Ramsay A.J., et al. Differential effects of the type I interferons α4, β, and ε on antiviral activity and vaccine efficacy. J Immunol. 2008;180:7158–7166. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tasker C., Subbian S., Gao P., et al. IFN-epsilon protects primary macrophages against HIV infection. JCI Insight. 2016;1 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.88255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dieleman L.A., Palmen M.J., Akol H., et al. Chronic experimental colitis induced by dextran sulphate sodium (DSS) is characterized by Th1 and Th2 cytokines. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;114:385–391. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]