Abstract

Primary aldosteronism (PA) is the most common cause of secondary hypertension and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality when compared with blood pressure–matched cases of primary hypertension. Current limitations in patient care stem from delayed recognition of the condition, limited access to key diagnostic procedures, and lack of a definitive therapy option for nonsurgical candidates. However, several recent advances have the potential to address these barriers to optimal care. From a diagnostic perspective, machine-learning algorithms have shown promise in the prediction of PA subtypes, while the development of noninvasive alternatives to adrenal vein sampling (including molecular positron emission tomography imaging) has made accurate localization of functioning adrenal nodules possible. In parallel, more selective approaches to targeting the causative aldosterone-producing adrenal adenoma/nodule (APA/APN) have emerged with the advent of partial adrenalectomy or precision ablation. Additionally, the development of novel pharmacological agents may help to mitigate off-target effects of aldosterone and improve clinical efficacy and outcomes. Here, we consider how each of these innovations might change our approach to the patient with PA, to allow more tailored investigation and treatment plans, with corresponding improvement in clinical outcomes and resource utilization, for this highly prevalent disorder.

Keywords: functional/molecular imaging, adrenal vein sampling, machine learning, metabolomics, ablation, adrenal sparing surgery, partial adrenalectomy

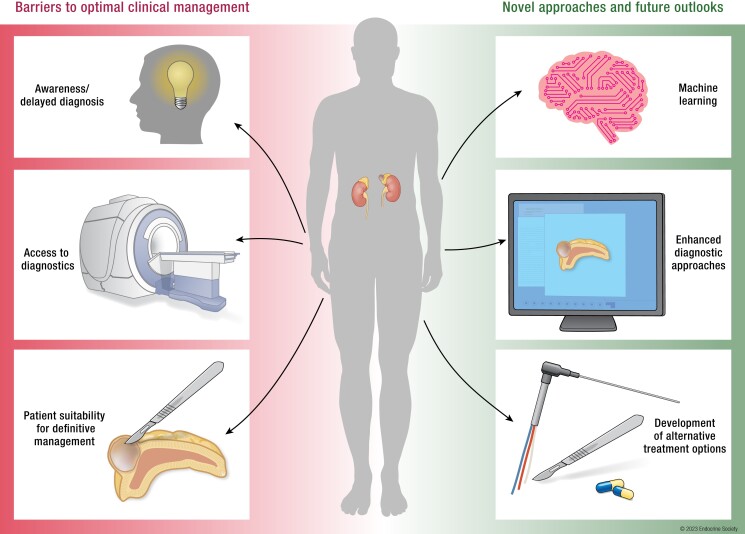

Graphical Abstract

Essential Points.

Despite being a common cause of hypertension, many cases of primary aldosteronism (PA) remain undiagnosed or are only recognized at a late stage when treatment benefits are diminished; challenges in screening and confirmation of diagnosis remain significant hurdles to effective management

Recent advances in metabolomics and machine learning have the potential to increase the diagnosis of PA by identifying patients who should be considered for screening and, at the same time, aiding clinical decision making through prediction of disease subtype

Currently, only a small proportion of patients with PA progress to adrenal surgery, reflecting the challenges inherent in securing a diagnosis of unilateral disease; for others, pharmacotherapy with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) is advised, but is not always well tolerated or efficacious

Recent advances in diagnostic techniques, including segmental adrenal vein sampling and molecular (functional) imaging (eg, positron emission tomography/computed tomography) have allowed the focus of attention to switch from simple adrenal lateralization to more accurate tumor(s) localization

The ability to localize aldosterone producing adenomas/nodules ultimately paves the way for the use of more focal treatment options (including partial adrenalectomy or adrenal adenoma/nodule ablation), which may in turn open up avenues for intervention in patients with previously deemed inoperable disease (including bilateral PA)

More selective pharmacological agents, including nonsteroidal MRAs, aldosterone synthase inhibitors, and molecules that target calcium signaling are under investigation to permit pharmacotherapy which more effectively alleviates aldosterone excess with fewer adverse effects

The field of research in PA requires high-quality, prospective evidence to progress research advances to clinical care

Introduction: Current Approaches and Challenges in the Diagnosis and Management of Primary Aldosteronism

Primary Aldosteronism: A Common but Under-recognized Cause of Hypertension

Hypertension is the single greatest cause of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, affecting >1 billion adults worldwide and up to 30% of certain adult populations (1). While primary hypertension (where no clear cause is identified) accounts for the majority (70-85%) of cases, some 15% to 30% of patients have an identifiable endocrine or renal cause (secondary hypertension) (2, 3). Primary aldosteronism (PA) represents the commonest secondary cause of hypertension, with an estimated prevalence between 3.2% and 14% among primary care populations (4-8), increasing to 10% to 20% in the hospital outpatient setting (5, 6, 9). Significant challenges exist in screening and diagnosing PA and therefore current estimates of prevalence may be modest in the overall context of disease (10-12). Despite its commonality as a secondary cause of hypertension, PA has not been a key consideration in the design of over 40 randomized control trials which have investigated the management of hypertension over the past 30 years. Therefore, screening rates for PA remain low, clinical recognition is poor, and current hypertension guidelines do not emphasize the need to investigate for PA in patients presenting with hypertension to their primary care physicians or general internists.

PA arises from excessive, unregulated secretion of the steroid hormone aldosterone. This is most commonly attributable to an aldosterone-producing adenoma (APA), or other neoplasia/hyperplasia of aldosterone-producing cells within the zona glomerulosa (ZG) of the adrenal cortex, with recent consensus reached for nomenclature to describe the underlying histopathological findings (Table 1) (13).

Table 1.

Summary of the HISTALDO (histopathology of primary aldosteronism) consensus nomenclature

| Histopathological finding | Features | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Aldosterone producing adenoma (APA) | CYP11B2 positive solitary neoplasm ≥10 mm in diameter | Nonfunctioning adenomas may be of similar size/morphology under H&E staining. Hence, differentiation requires a combination of clinical assessment (eg, through the demonstration of ipsilateral aldosterone hypersecretion on adrenal vein sampling) and histologic analysis using CYP11B2 immunostaining with a validated CYP11B2 antibody. APAs exhibit positive CYP11B2 staining, which is either homogenously distributed, or of a diffusely heterogeneous pattern throughout the neoplasm. |

| Aldosterone producing nodule (APN) | CYP11B2 positive lesion <10 mm in diameter | APNs are smaller in size than APAs and are morphologically visible using H&E staining. There is often a polarity of CYP11B2 staining within the nodule, which decreases in intensity from the outer to inner part of the lesion. |

| Aldosterone producing micronodule (APM): formally known as “aldosterone-producing cell cluster” | CYP11B2 positive lesion <10 mm in diameter confined to the outer margin of the subcapsular ZG | APMs do not differ in morphology from surrounding ZG on H&E staining. There is often a polarity of CYP11B2 staining within the nodule, which decreases in intensity from the outer to inner part of the lesion. |

| Multiple aldosterone-producing nodules (MAPNs) or multiple aldosterone-producing micronodules (MAPM): formally known as “micronodular hyperplasia” | Multiple CPY11B2 positive lesions within the same adrenal that coexist with regions of normal ZG | Both MAPN and MAPM can exist within the same adrenal. |

| Aldosterone-producing diffuse hyperplasia (APDH) | The presence of a broad, uninterrupted strip of hyperplastic ZG cells with CPY11B2 positive immunostaining in >50% of cells | The term “aldosterone-producing diffuse hyperplasia” should be applied irrespective of the presence of APN in the same adrenal. |

Table adapted with permission from Williams et al JCEM, 2021; 106(1): 42-54. © The Endocrine Society (13).

Abbreviations: CYP11B2, aldosterone synthase, H&E, hematoxylin & eosin staining; ZG, zona glomerulosa.

Clinically, PA results in stage/grade I to III hypertension in >97% of patients, and spontaneous or drug induced hypokalemia in approximately 50% of cases with an apparent APA (6). PA is associated with higher cardiovascular morbidity than age- and blood pressure (BP)–matched primary hypertension (6, 14-22). This has been demonstrated consistently across several observational studies and confirmed in a recent meta-analysis (15). Individuals with PA demonstrate higher risk of atrial fibrillation (odds ratio 3.52), stroke (2.58), coronary artery disease (1.77), heart failure (2.05), diabetes (1.33), metabolic syndrome (1.53), and left ventricular hypertrophy (2.29) than patients with primary hypertension (15). Elevated aldosterone levels are associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality, especially in cases where aldosterone levels misalign with renin levels and sodium intake (20, 23-27). In this regard, Hundemer and colleagues have highlighted that renin de-suppression (to within the reference range) in addition to BP control, either by medical therapy or adrenalectomy, is necessary to reduce excess risk to levels seen in those with primary hypertension (28-32). Therefore, it is desirable in PA to target both BP and biochemical outcomes (ie, renin desuppression).

Current challenges in screening

PA is underdiagnosed and undertreated in current clinical practice, where screening and diagnosis are the principal challenges that limit effective management (33-35) (traditional diagnosis/treatment workflow for PA highlighted in Figs. 1 and Figs. 2). Overall, there is no consensus on recommended screening for PA in hypertensive individuals, within either primary or secondary care settings. The Endocrine Society guidelines for the diagnosis and management of PA recommend screening up to 50% of “at risk” patients for PA. Screening under these recommendations should be carried out using the aldosterone–renin ratio (ARR) with particular attention paid to those with (1) severe hypertension; (2) hypertension with spontaneous or diuretic-induced hypokalemia; (3) an adrenal mass; (4) sleep apnea; (5) a family history of early-onset hypertension; (6) stroke at a young age; or (7) a first-degree relative who has PA (36). American Heart Association guidelines for the diagnosis and management of hypertension, align with the Endocrine Society guidelines in terms of recognized risk factors which should trigger screening for PA; in contrast, European Society of Cardiology/European Society of Hypertension guidance do not emphasize the need to screen for PA except in patients with treatment-resistant hypertension (approximately 5% of all patients) (37, 38). Some national guidelines for the management of hypertension, such as those of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK, do not specifically reference screening for PA (39, 40).

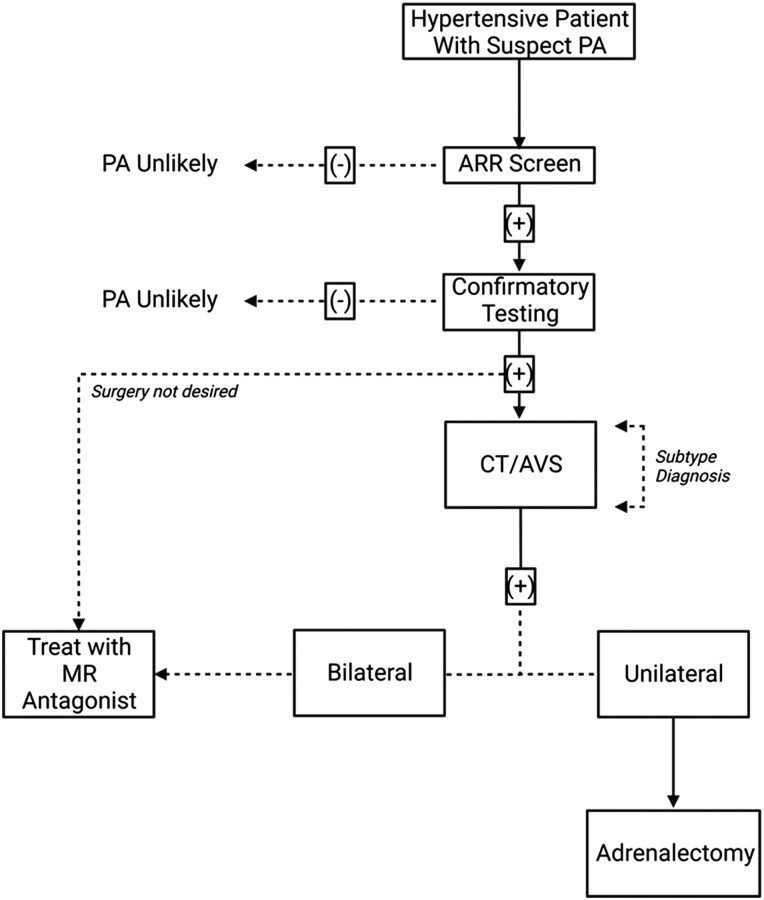

Figure 1.

The traditional approach to the diagnosis and management of patients with PA: Initial diagnosis is determined by a positive aldosterone–renin ratio (ARR) screen with at least 1 positive confirmatory test (discussed in “Screening, Diagnosis, and the Spectrum of Disease”). Following diagnosis, subtype diagnosis (ie, lateralization) is sought through use of adrenal imaging/adrenal vein sampling (AVS) (discussed in “Current Approach to Lateralization”). Unilateral disease is commonly treated with adrenalectomy of the diseased adrenal whereas in cases of bilateral disease, mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) antagonists are commonly prescribed (discussed in “Advances in Pharmacotherapy”).

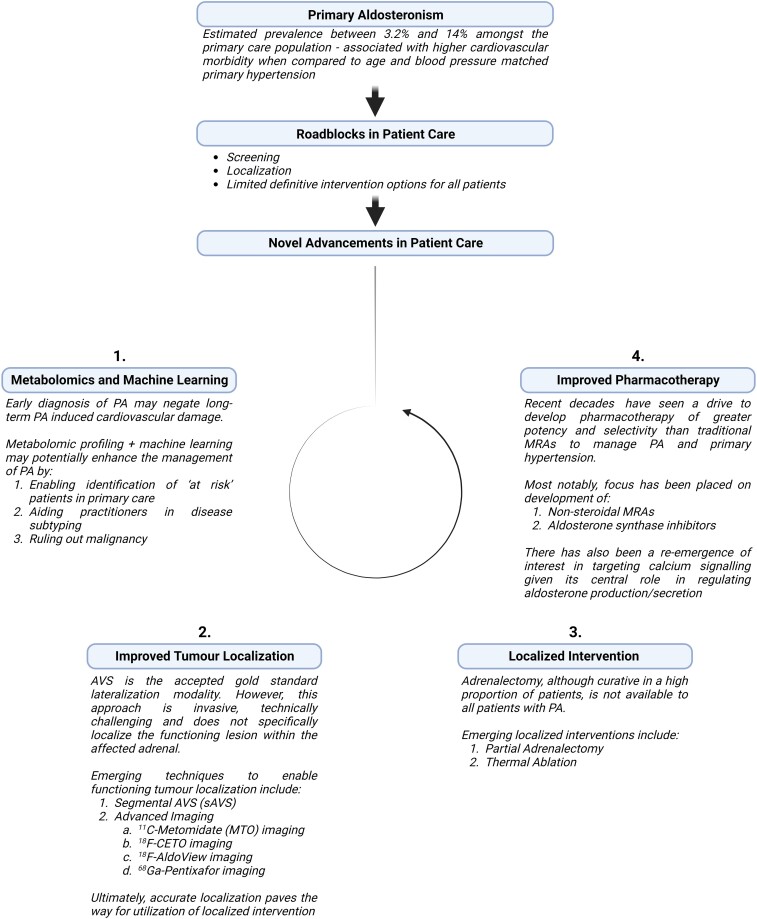

Figure 2.

Outline of current “roadblocks” in primary aldosteronism (PA) care, with suggested approaches to addressing these, including: 1. Improved screening for, and diagnosis of PA through application of metabolomics and machine learning; 2. Utilization of advanced lateralization techniques including molecular (functional) imaging to permit precise tumor localization; 3. Use of focal adrenal-sparing interventions (eg, adrenal-sparing surgery or thermal ablation) where appropriate; 4. Continued development of more selective pharmacological agents. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Overall, screening rates for PA are low. In spite of Endocrine Society and American Heart Association guidelines, a population-based retrospective cohort study in Canada reported a screening rate of only 3.9% of all patients with hypokalemia (K+ <3.0 mEq/L) and hypertension, and 1% of patients who were on 4 or more antihypertensive agents. Screening was higher for patients attending a cardiologist, endocrinologist, or nephrologist (41). European data, collected from patient cohorts in Germany and Italy where there is higher awareness of PA, still observed screening rates within a primary care setting that were <8% (36, 42, 43). These findings are important because the diagnosis and management of hypertension is mostly undertaken in primary care or by generalists and it is important therefore to understand the roadblocks to screening among these professionals (Fig. 2).

Typically, low screening rates for PA are matched with less awareness of specific guidelines for its diagnosis and management (such as those of the Endocrine Society (36)), and a greater reliance on more general hypertension guidelines (which are frequently more treat to target oriented). In addition, screening for PA in a primary care setting may be particularly challenging (eg, when there is restricted access to aldosterone and renin assays) (5, 42, 44). Even where available, screening is often not routinely deployed (42, 44). The reasons for this are likely multifactorial and include clinician and/or patient reluctance to countenance withdrawal of potential confounding antihypertensive agents (summarized in Table 2) because of the fear of loss of BP control, coupled with a lack of familiarity with alternative noninterfering medications. These “roadblocks” were highlighted in a qualitative study that probed the experience of 16 general practitioners in screening for PA where knowledge gaps, practical limitations of performing the ARR, and errors in diagnostic reasoning were the main challenges associated with routine PA screening (44).

Table 2.

List of antihypertensive interfering medications

| Medications | Aldosterone levels | Renin Levels | Effect on ARR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-adrenergic blockers | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Central alpha-2 agonists | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| NSAIDs | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Dihydropyridines | →↓ | →↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| K+ -wasting diuretics | →↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| K+ -sparing diuretics | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| ACE inhibitors | ↓ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| ARBs | ↓ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Renin inhibitors | ↓ | ↓*↑ | ↑(FP)* OR ↓(FN)* |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker; ARR, aldosterone–renin ratio; FN, false negative; FP, false positive; K+, potassium; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; ↓, reduces; ↓↓, significantly reduces; ↑, increases; ↑↑, significantly increases; →, no effect; ↓↑, may reduce or increase; → ↑, no effect, or increases.

*Renin inhibitors lower plasma renin activity (PRA) but raise plasmas renin concentrations (PRC). This would be expected to yield false positive ARR levels for renin measured as PRA and false negatives for renin measured as DRC.

Table adapted from Shidlovski et al., 2019 with minor modifications in compliance with the attribution 4.0 international (CC BY 4.0) guidelines (45).

As a result of low screening and a lack of awareness of PA, patients are often hypertensive for many years (eg, 5-20) before BP that is suboptimally controlled on multiple agents triggers the necessary investigations to permit the diagnosis (46). While PA is both a curable and treatable form of hypertension, the effectiveness of targeted intervention may be significantly attenuated by a late diagnosis. Prolonged hypertension induces permanent vascular remodeling and, in turn, persistent, ongoing hypertension following definitive treatment of PA (9, 47-49). Therefore, to improve the outcomes of PA at a population level, greater focus on removing the current “roadblocks” that exist in primary and secondary care is necessary to deliver increased rates of screening and diagnosis (Fig. 2). One such approach is to actively increase awareness of PA in primary care, and among generalists and cardiologists. The potential benefits of this approach have been highlighted in a prospective study within a primary care setting by Libianto and colleagues, where a 30-minute education session was provided to primary care physicians, across 31 practices, to encourage screening for PA in newly diagnosed, treatment naïve cases of hypertension (8). Of 247 treatment naïve patients who were screened for PA, 25% had an elevated ARR, with 14% subsequently confirmed to have PA by saline suppression test (8).

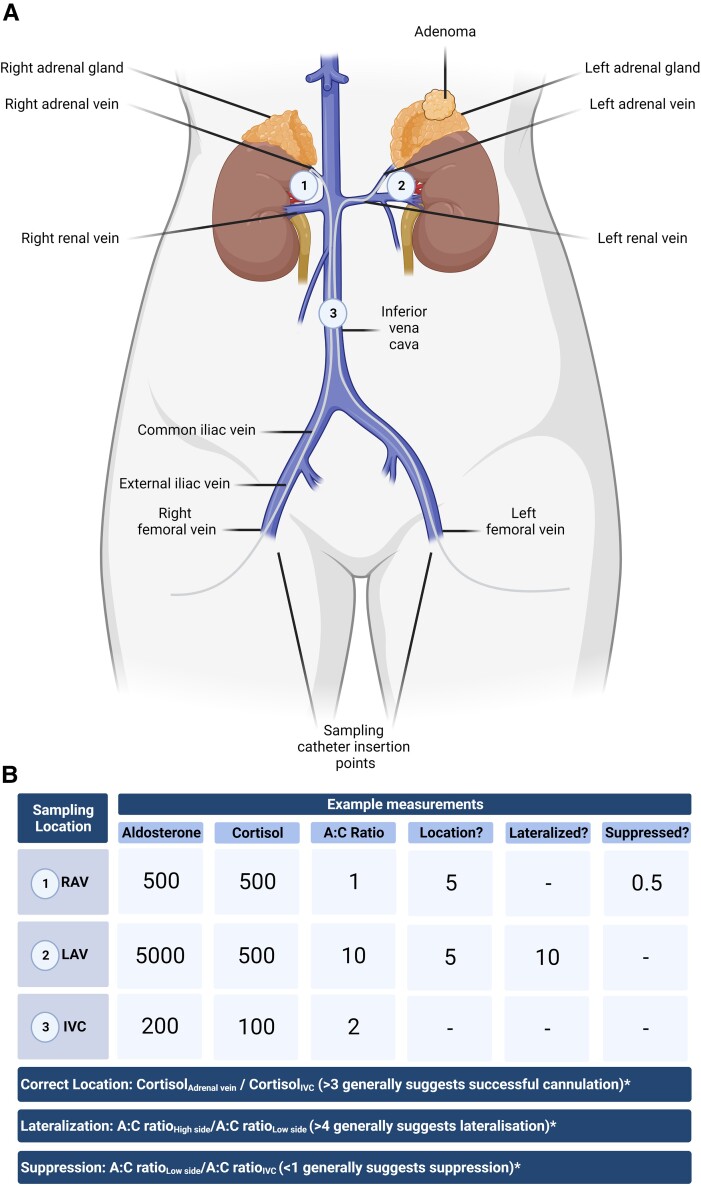

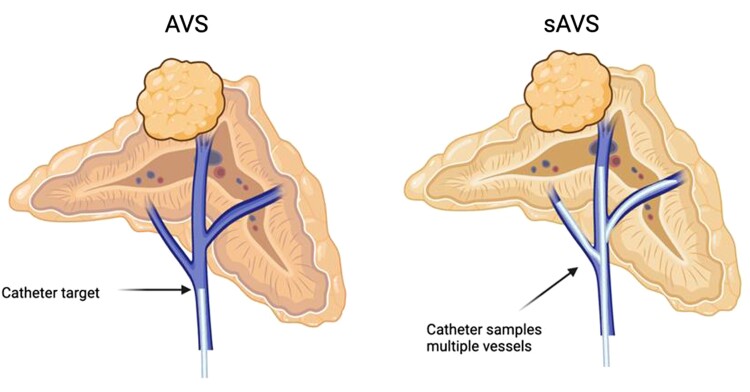

Figure 3.

(A) Outline of the adrenal vein sampling (AVS) procedure. A sampling catheter is inserted in either the left or right femoral vein for sampling the left and right adrenal vein in the presence or absence of cosyntropin stimulation. Aldosterone and cortisol are sampled from locations 1-3 and, for each location, the aldosterone to cortisol ratio is calculated. Together, these values are used to determine: (1) Selectivity index: Did sampling occur from the correct location, ie, right adrenal vein (RAV), left adrenal vein (LAV), and inferior vena cava (IVC)? (2) Lateralization: Are 1 or both adrenals the source of aldosterone excess? (3) Is contralateral suppression present? (B) Example measurements demonstrating successful cannulation of both adrenal glands (location) under basal, unstimulated conditions (both locations return a selectivity index >3), with lateralization to the left adrenal and the presence of contralateral suppression. *Note, the cut-offs described in this diagram are arbitrarily defined for illustrative purposes. As is indicated by Quencher and colleagues 2021 there are marked procedural and cut-off heterogeneity between centers (64). Figure created with Biorender.com.

Screening, diagnosis, and the spectrum of disease

Current screening for PA relies on simultaneous measurement of plasma aldosterone concentration and plasma (direct) renin concentration or plasma renin activity, which allow calculation of the ARR. In all but a handful of cases (eg, young age, with marked aldosteronism [hypertension and hypokalemia] and complete renin suppression), a positive ARR screen is followed by confirmatory dynamic testing: (1) saline infusion test (SIT), (2) oral salt suppression test, (3) captopril challenge test, or (4) fludrocortisone suppression test (Fig. 1) (36).

Although this approach is generally advocated by specialists in the field, there remains considerable heterogeneity with respect to the diagnostic thresholds employed for each of these tests. Furthermore, in recent years an “expanding spectrum of primary aldosteronism” has been acknowledged such that PA may not be readily diagnosed or distinguished on the basis of rigid diagnostic cut-offs alone (50, 51). For instance, Vaidya et al, describe a spectrum of disease ranging from clinically overt PA (patients with severe and/or resistant hypertension) that is readily detectable using current thresholds for biochemical confirmation, to unrecognized yet biochemically overt PA (in patients with normotension or mild/moderate hypertension). These findings suggest the existence of “subclinical” or “nonclassical” categories of PA (normotensive patients with autonomous aldosterone secretion) who are likely to go unnoticed because they do not meet current screening indications for PA (50). Expert consensus on a broader classification of PA has yet to be reached, and defining the full spectrum of disease is challenging given the limitations of current clinical testing (discussed further in “Metabolomics and Machine Learning”).

Notwithstanding ongoing work to more comprehensively define this spectrum, current clinical practice still relies on the use of screening and diagnostic thresholds or “cut-offs” to biochemically confirm or exclude the condition (36, 50, 52, 53). However, even here, there can be significant variation between centers reflecting differing background reference populations, laboratory assay architecture (eg, activity vs direct renin measurement; chemiluminescence assay vs liquid chromatography mass spectrometry [LC-MS/MS]; assay performance) (54-56). Reference ranges for aldosterone and renin also differ between the sexes, and in women according to the stage of the reproductive cycle (54, 57-60).

Opinion differs in relation to optimum conditions for ARR screening. Many advocate screening only in the absence of interfering medications (58-60), while others recommend that initial screening be undertaken irrespective of antihypertensive management, and the results interpreted in the context of the expected antihypertensive interference (46, 61). Endocrine Society guidelines recommend (where feasible) that thiazide diuretics, beta-blockers and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) should be withdrawn prior to screening for PA (36). While there is consensus that all individuals should be normokalemic at the time of ARR determination, there is no clear guidance around salt intake prior to screening for PA. In this regard, dietary sodium intake has been shown to significantly affect plasma renin measurements (62). Postural measurement of the ARR is no longer commonly undertaken and current practice is to sample midmorning, seated for 15 minutes, and following a period of at least 2 hours of ambulation (36, 58).

Irrespective of diagnostic thresholds and/or sampling conditions, interpretation of the ARR is also challenged by the lack of consensus as to whether or not the ARR threshold alone is sufficient to trigger further testing, or if the ARR threshold should be accompanied by a minimum aldosterone cut-off. In this context the performance of the ARR as a screening test varies significantly. For example, in one cohort of patients with hypertension the use of conjunctive standards to define a “positive” screen (ie, ARR >30 ng/dL per ng/ml/h and aldosterone >10 ng/dL) identified 13.9% (232/1672) with possible PA, of whom 99 (ie, 5.9% of the total cohort), were subsequently confirmed to have PA (34). In another cohort of patients with hypertension who were receiving a high dietary sodium intake, the use of an ARR threshold of >20 ng/dL per ng/ml/h, without the requirement to exceed a minimum aldosterone threshold, returned a positive screening rate of 32.7% (79/241), which in turn yielded a higher rate of actual cases (19%, 48/241) following confirmatory testing (62). It is important to note however, that this difference could, at least in part, reflect selection bias whereby only patients considered “at risk” for PA were screened. This differs from other work (34) which carried out universal screening on a hypertensive population. Additional work is therefore still necessary to clarify whether or not ARR threshold alone vs combined aldosterone and ARR thresholds should be employed in PA screening.

Similarly, the gold standard status of confirmatory testing has recently been called in to question in a comprehensive meta-analysis (55 studies; 7357 patients) of the 4 commonly used investigations (SIT, salt-loading test, fludrocortisone suppression test, and captopril challenge test) (63). In analyses of the recumbent SIT (26 studies), seated SIT (4 studies), oral salt-loading test (2 studies), fludrocortisone suppression test (7 studies), and captopril challenge test (25 studies) the authors concluded that overall there was a low standard of evidence to support the use of current confirmatory testing in PA. Specifically, the majority of studies demonstrated significant verification and spectrum bias, which led to overestimation of test accuracy (by 5- to 7-fold) with an excess of missed cases, such that many patients were overlooked for treatment. Of particular concern was the finding that verification of the true diagnosis of PA varied across the study spectrum with inconsistent reference standards. Acknowledging the limitations highlighted within this metanalysis, the fludrocortisone challenge test demonstrated the best performance as a confirmatory test, followed by the recumbent SIT and the captopril challenge test.

In summary, a high-quality, common gold standard to calibrate diagnostic testing is currently absent in the field of PA and this in turn challenges the estimation of PA prevalence in general. It is clearly important that consensus is reached among the expert community as to what constitutes (1) a positive screen to trigger confirmatory testing for PA and (2) a confirmed diagnosis of PA. Ideally validation of a best diagnostic approach would be carried out through multicenter, prospective studies, using an agreed diagnostic standard. However, while a diagnostic standard is more easily established for unilateral PA on the basis of surgical outcomes, deciding upon a comparable standard for bilateral disease is more challenging.

Current approach to lateralization

Lateralization (ie, discrimination between left and right adrenal causes of PA) is commonly assessed as part of the diagnostic work-up of PA (Fig. 1); however, challenges remain in more precisely localizing the site(s) of functioning lesion(s) responsible for unregulated aldosterone secretion. Current guidelines recommend that the invasive procedure adrenal vein sampling (AVS) is performed in the majority of patients who are being considered for surgery, to discriminate unilateral and bilateral causes of PA, and to identify the affected adrenal in unilateral PA (UPA) (AVS procedure outlined in Fig. 3) (36). AVS is therefore considered the gold standard for lateralization, and the use of cross-sectional (anatomical) imaging (eg, computed tomography [CT]) alone is not generally advised (discussed in more detail below). Yet, conventional AVS does not specifically localize disease within the adrenal, but instead lateralizes to the entire gland.

Several studies have compared CT and AVS in the lateralization of PA and the majority of these studies have reported CT to be an inferior lateralization modality. A meta-analysis of studies which compared the performance of cross-sectional imaging (CT/magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) against an AVS reference standard demonstrated an overall pooled specificity for CT/MRI of 57% in identifying a unilateral APA (65). This meta-analysis included 25 studies, carried out between 2000 and 2020, and involving 4669 patients. In age-related subanalysis of individuals aged <40 years, specificity was 79%. The authors concluded that cross-sectional imaging was not a reliable lateralization modality, even in younger patients, where 21% would have been inappropriately recommended for adrenalectomy. However, there was significant variation in study design, and in the reference standards used for the diagnosis of PA and AVS lateralization across the studies. Additionally, AVS was used as the lateralization reference standard rather than clinical outcomes (eg, response to adrenalectomy). Clinical outcome is difficult to report in PA as this approach usually selects outcomes for UPA only, given that this cohort most commonly undergo adrenalectomy. There is no consensus on a defined clinical outcome, linked to confirmation of disease, for medical therapy in the setting of bilateral PA.

Few large studies have used clinical outcomes to address the question of lateralization using cross-sectional imaging vs AVS for APA lateralization (66, 67). One report retrospectively analyzed 158 patients who underwent AVS (before and after cosyntropin administration) and CT (66). Within this study, CT lateralization agreed with AVS in only 51% of patients, and CT imaging alone was deemed to have significantly overestimated the presence of a unilateral adenoma (CT:114/158 vs AVS:55/158). However, only those who lateralized using AVS (after cosyntropin) underwent surgery (55 patients in total) and therefore, while clinical outcomes are reported in this study, the study design primarily uses AVS lateralization rather than clinical outcomes as the standard for intervention per se. In that regard, the study cannot be described as directly comparing AVS and CT as lateralization modalities, but rather as comparing the performance of CT with that of AVS. Within this study, CT was used to guide partial adrenalectomy of a clearly identified nodule in 3 patients who also lateralized using AVS. However, in 2 of these patients there was persistence of PA due to another lesion in the ipsilateral adrenal, not identified on CT. Additionally, immunohistochemistry with CYP11B2 staining demonstrated that the radiologically identified nodules were not always the culprit lesions for PA, but rather smaller adjacent lesions were responsible, which had not been identified using CT alone. Given the weight of the combined evidence which questioned the performance of CT, the authors justifiably recommended against using CT as a lateralization modality on the basis of these findings (66).

To date, only a single prospective study (SPARTACUS) has directly compared the lateralization of APAs with CT vs AVS, using clinical outcomes as the reference standard in individuals with an adrenal nodule and a confirmed diagnosis of PA (68). In this study the clinical treatment outcomes (intensity of drug treatment to achieve target BP; biochemical outcome in adrenalectomized patients) did not differ after 1 year of follow-up when comparing CT vs AVS findings (68). On the basis of these findings, the authors suggested that lateralization of PA in the presence of an adrenal nodule was equivalent for AVS and CT. However, while prospective, significant concerns have been raised in relation to the trial design, most notably with respect to selection bias, choice of endpoint criteria, and the potential for being underpowered within the adrenalectomy group (69, 70). Therefore, commentary and concern regarding the study design for SPARTACUS has limited the application of its recommendations in the clinical setting. Consequently, CT-guided lateralization of UPA does not currently represent the best standard of practice, with AVS representing the favored gold standard (36). However, in a similar manner to confirmatory testing, the evidence to support AVS as a true gold standard in the lateralization of PA is open to challenge. For instance, while its positive predictive value is well described in the literature, there is a lack of data to describe its negative predictive value; in essence, for patients deemed not suitable for, or who do not lateralize on AVS, a validated, alternative lateralization or localization modality has been notably absent to this point. Consensus is also lacking in relation to the methodological approach and cut-offs for AVS. We discuss the role of AVS and CT, as well as the rise and utility of molecular imaging modalities in the lateralization and localization of PA in further detail within “Advances in Lateralization and Localization.”

Current management and outcomes

With early diagnosis, adrenalectomy is potentially curative in unilateral disease. Current management of bilateral disease relies on medical therapy, with MRAs taking primacy (Fig. 1).

There are 6 consensus outcomes of surgical intervention that are described in the Primary Aldosteronism Surgery Outcome (PASO) study (summarized in Table 3) (49). Using these criteria, adrenalectomy has been reported to deliver complete biochemical success and complete clinical success in 94% and 37% of patients, respectively, ratifying accepted recommendations for adrenalectomy as the first-line therapy in the treatment of UPA (36, 49). Laparoscopic or retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy is preferred in most centers, being less invasive than open surgery (36, 71). In particular, duration of anesthesia, recovery period, and length of hospitalization are significantly lower for laparoscopic approaches. Varying degrees of postoperative adrenal insufficiency have been reported in the literature following unilateral adrenalectomy. However, postoperative adrenal insufficiency following treatment of UPA is typically partial and while it has been described in up to 27% of patients, it is almost always subclinical in nature and transient (72-76). Accordingly, patients seldom require regular glucocorticoid replacement but may require cover for intercurrent illness/emergencies as appropriate. Hypoaldosteronism, requiring fludrocortisone replacement therapy has been reported following unilateral adrenalectomy in more severe cases of PA (particularly in cases where there is evidence of significant contralateral gland suppression at AVS) (77-79). Again, it is potentially reversible.

Table 3.

The international standardized outcome criteria following unilateral adrenalectomy described according to the Primary Aldosteronism Surgical Outcome (PASO) study (49)

| Clinical outcome | |

|---|---|

| Complete clinical success | Normal blood pressurea, without the aid of antihypertensive medications. |

| Partial clinical success | The same blood pressure as before surgery, with less antihypertensive medication or a reduction in blood pressure with either the same amount or less antihypertensive medication. |

| Absent clinical success | Unchanged or increased blood pressure, with either the same amount or an increase in antihypertensive medication. |

| Biochemical outcome | |

| Complete biochemical success | Correction of hypokalemiab (if present pre-surgery) and normalization of the aldosterone-to-renin ratioc; in patients with a raised aldosterone to renin ratio postsurgery, aldosterone secretion should be suppressed in a confirmatory test. |

| Partial biochemical success | Correction of hypokalemiab (if present pre-surgery) and a raised aldosterone to renin ratio with 1 or both of the following (compared with presurgery): ≥50% decrease in baseline plasma aldosterone concentration; or abnormal but improved postsurgery confirmatory test result. |

| Absent biochemical success | Persistent hypokalemia (if present presurgery) or persistent raised aldosterone to renin ratio, or both, with failure to suppress aldosterone secretion with a postsurgery confirmatory test. |

Following surgery, outcomes should be assessed: within 3 months, at 6-12 months (the principal timepoint for gauging success), and annually.

Table adapted with permission from Williams et al, 2017 (49).

abc For specific guidance on reference ranges, please refer to Williams et al, 2017.

Recently, a potential role for adrenal surgery in patients with bilateral PA has been considered. Specifically, for a small group of patients who cannot be controlled on medical therapy unilateral adrenalectomy may be performed even when bilateral disease has been confirmed (75, 80-82). In this context, unilateral adrenalectomy does not offer disease cure, but rather it may improve BP in patients uncontrolled on/or intolerant of multiple antihypertensives. Similarly, a potential role for bilateral adrenal surgery (eg, total adrenalectomy on 1 side and partial adrenalectomy on the other side, or bilateral partial adrenalectomies) has been reported (81). However, the decision whether to proceed with adrenal surgery in a patient with bilateral PA remains a very challenging management dilemma (83-85).

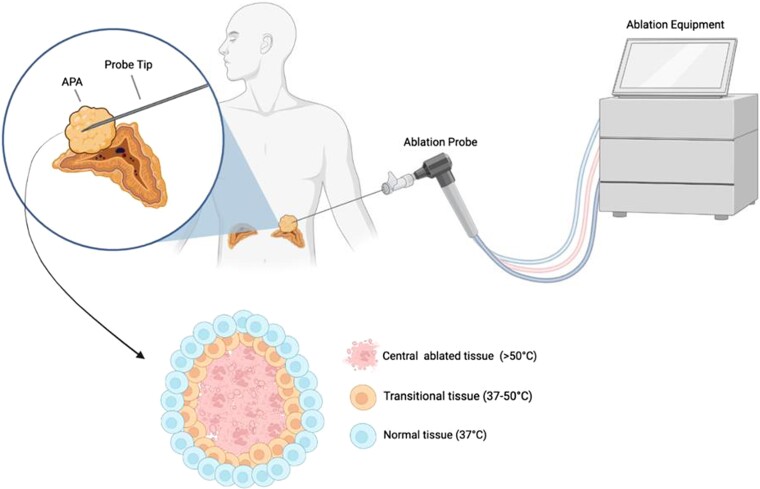

Approaches which can selectively target or remove offending aldosterone-producing lesions might therefore be preferable to unilateral adrenalectomy for bilateral disease. In this regard, localized therapies such as selective adenoma/nodule ablation or adrenal-sparing surgery could have an important role to play in the future management of both unilateral and bilateral PA (discussed in “Partial Adrenalectomy: Targeted Tumor Resection” and “Thermal Ablation: A Targeted Minimally Invasive Therapeutic Approach”). However, before such an approach can be recommended, more reliable and precise localization of culprit APAs and/or APNs is required: (1) to render these therapies feasible; (2) to avoid incorrectly targeting nonfunctioning tumors; (3) to spare as much normal adjacent tissue as possible in cases of bilateral intervention; and (4) to monitor therapeutic success postintervention (74, 75) (Fig. 6). Both APAs and APNs may be more amenable to localized intervention, with APAs occurring in up to one third of PA cases (5, 86). Multiple aldosterone-producing nodules and APDH present a greater challenge for targeted intervention, due to the difficulty in localizing the former, and inability to localize the latter given that hyperplasia normally extends throughout the entire perimeter of the affected gland(s) (13).

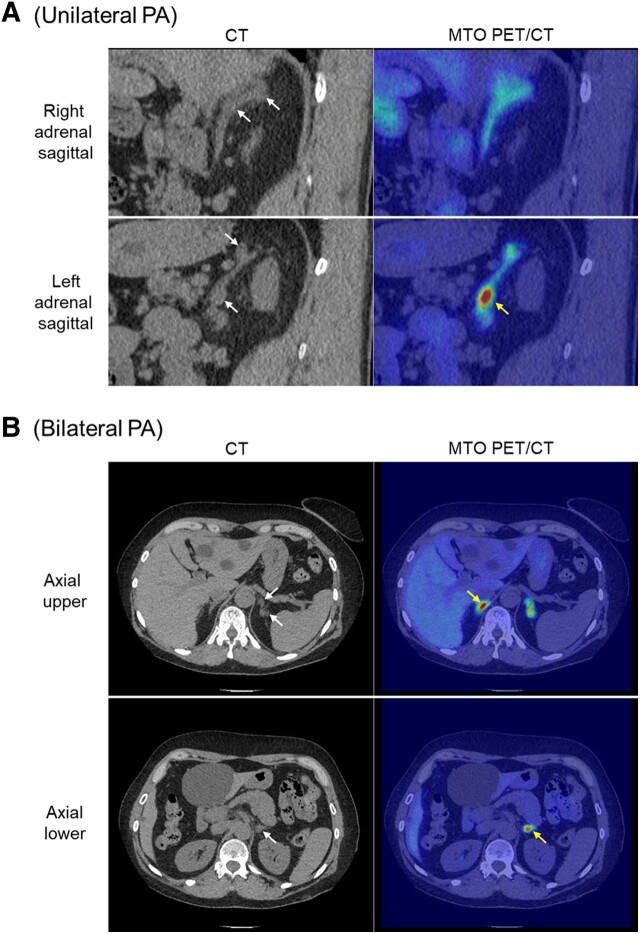

Figure 6.

11C-metomidate PET/CT allows localization of aldosterone-secreting adenomas/nodules in unilateral and bilateral PA. (A) Sagittal CT demonstrating 2 discrete nodules within the left adrenal gland, but with only the inferior 1 showing high focal tracer uptake; the right adrenal gland shows normal background radiotracer uptake despite the initial suspicion of possible nodularity. Following left unilateral adrenalectomy, the patient achieved full clinical and biochemical remission and immunohistochemistry confirmed that the metomidate-avid nodule exhibited strong staining for CYP11B2; in contrast the superior nodule showed only mild CYP11B1 staining. (B) Axial CT and MTO PET/CT in a patient with bilateral PA. Both adrenal glands demonstrate focal high radiotracer uptake; within the left adrenal, the most inferior of 3 discrete nodules shows greatest metomidate uptake. The patient was managed with primary medical therapy. White arrows denote sites of suspected nodules on CT; yellow arrows identify nodules with greatest metomidate avidity.

PA therefore remains an area with significant potential for the rapid translation of clinical, laboratory, radiological, and procedural innovations, which are urgently required to allow more effective management of this common condition. This review focusses on emerging and novel approaches to the diagnosis, localization, and management of PA. In “Improving the Diagnosis of PA,” we examine metabolomics and artificial intelligence approaches in screening and diagnosis of PA, with particular reference to the broader spectrum of disease and how this may be identifiable using newer technologies. In “Advances in Lateralization and Localization,” we examine current approaches to lateralization and discuss how emerging molecular imaging can enable precise localization of disease within the adrenal glands. In “Novel Treatment Approaches,” we discuss the feasibility of localized interventions, both minimally invasive and surgical, in the management of unilateral and bilateral disease. Finally, in “Advances in Pharmacotherapy,” we summarize the clinical trial data and reference emerging pharmacotherapy for the medical management of PA, with particular reference to the management of patients where definitive therapy is not possible.

Improving the Diagnosis of PA

Overcoming Challenges of the Current Diagnostic Approach

Early diagnosis of PA predicts response to therapy (35, 36). Ideally screening should be undertaken in primary care or by generalists (ie, at the time when hypertension is first recognized), using laboratory tests which are readily available and easy to interpret. Current screening for PA typically relies on determining the ARR. Measurement of plasma aldosterone and plasma renin, and interpretation of the ARR, is challenged by (1) assay availability, (2) stability of renin at room temperature following venesection, (3) requirement for specific sampling conditions (midmorning, seated for 15 minutes following 2 hours ambulation), (4) assay interpretation in the face of interfering antihypertensive medications, (5) requirement for confirmatory testing to establish the diagnosis due to low specificity of the ARR (approx. 65%), and (6) the intraindividual variability in screening aldosterone concentrations, renin measurements (plasma renin concentration and plasma renin activity), and their corresponding ARRs (87, 88). Consequently, given these apparent complexities, apprehension among primary care physicians and generalists means that even a 50% screening threshold of “at risk” patients is rarely achieved, let alone the recommendation by some experts that all hypertensive patients should be assessed for PA at the time of diagnosis of hypertension (89).

The finding of a low serum potassium in a patient with hypertension has traditionally been viewed as a key trigger to screen for PA. However, not only does this overlook the significant proportion of patients with PA who do not exhibit hypokalemia, but even when present low serum potassium might not be evident if there are delays in samples reaching the laboratory as may occur with more rural practices, with resultant sample hemolysis (90).

A more pragmatic and practical approach is therefore required to (1) improve recognition of patients who should be prioritized for PA screening, (2) facilitate interpretation of ARR or other screening tests in the face of potential medication interference, and (3) increase access to laboratory assays which do not require specialist sample handling within primary care, and which therefore have greater potential to reveal the presence of PA in hypertensive patients. In this regard, the introduction of laboratory assays/methods that can be more easily performed on samples (blood or urine) collected in a nonspecialist setting should offer the prospect of getting many more patients over the first hurdle and onwards toward successful treatment.

Metabolomics and Machine Learning

Metabolomics measures several steroids, their metabolites, fatty acids, monoamines, polyamines and other endocrine mediators from a single urine or blood sample. In general, urine samples are preferred because (1) analytes are typically collected over a 24-hour period giving a more complete analysis rather than a single point in time analysis obtained from a blood sample; (2) urine and its metabolite content remain stable at room temperature and can be stored at temperatures between −20 °C and +4 °C for prolonged periods, therefore allowing sampling within environments which are remote to the analyzing laboratory (91). In recent years, metabolomic profiling, with analyses supported by machine-learning algorithms, has demonstrated potential utility in the diagnosis and management of Cushing syndrome and adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) (92, 93) (Fig. 4). Emerging data in hypertension and PA also points to a possible role in establishing or excluding the diagnosis of PA and in subtype categorization.

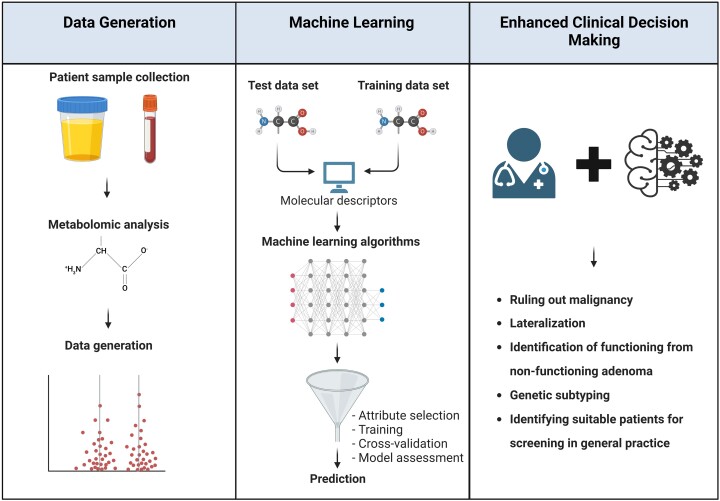

Figure 4.

Outline of metabolomics/machine-learning workflow. Following patient sample collection, metabolomic analysis is usually carried out using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry, yielding a large amount of data. Through combination with machine learning, a detailed metabolomic fingerprint can be generated of disease subtypes to streamline clinical decision making. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Several metabolomics studies have investigated hypertensive cohorts (including PA patients) in an effort to distinguish between primary and secondary hypertension, and between unilateral and bilateral PA (Table 4). These studies have identified numerous differences in metabolomic patterns which may enable distinction between different hypertension subtypes. Table 4 summarizes these studies and the performance of metabolomic analyses in diagnosing PA or distinguishing between primary and secondary hypertension. However, as yet, these findings have not translated to the adoption of metabolomics into the diagnostic pathway for PA or secondary hypertension. Consistent with their largely observational and retrospective nature, the study designs have varied significantly, with some reporting untargeted analyses (using “off the shelf” analytical kits), while others have pursued more bespoke targeted analysis (using locally validated analyte panels). Many were designed only to screen for primary hypertension, vs all-cause secondary hypertension, and most were conducted with samples collected across multiple centers without rigid standardization of collection methods, storage, or diagnostic standards. Additionally, interpretation of metabolomic data can be challenging. Prospective studies, with prior assay optimization/validation and standardization of analytical methods to permit accurate test interpretation, will therefore be required before a metabolomics-based approach to the investigation of suspected PA is a feature of routine clinical practice and can be adopted into clinical guidelines.

Table 4.

Recent data utilizing metabolomics and machine learning to identify PA and subtypes

| Study | Cohort | Reference standard for diagnosis | Findings | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constantinescu et al, 2022 (94) This study served to demonstrate the integration of artificial intelligence and plasma steroidomics with laboratory information management systems |

22 patients tested for PA | PA was screened using the ARR, with a cut-off of 31 pmol/mU. PA was confirmed with a positive saline infusion test | Based on a negative ARR screen—18 patients were excluded of PA diagnosis. The other 4 patients had a positive screen The probability of PA in this cohort was predicted using 3 machine-learning models (SVM, RF, and LDA): Probabilities of PA ranged from 89% to 100% (median 99%) in patients with PA and from 2% to 90% (median 21%) in those without PAa aSensitivities/specificities/AUC not defined SVM, support vector machine; RF, random forest; LDA, linear discriminant analysis |

Machine learning specified unilateral PA in all 4 patients (probability range: 73-100% (median 91%), with a consistently high likelihood of KCNJ5 mutations in 3 patients |

| Erlic et al, 2021 (95) Retrospective Targeted metabolomics on plasma samples using LC-MS/MS. Analyzed with classical approach (using a series of univariate and multivariate analyses) or machine learning (random forest) |

Primary hypertension: 282 Secondary hypertension: 223 total, 40 CS, 107 PA, and 76 PPGL |

Not specifically defined: (“The diagnosis (primary hypertension, CS, PA, PPGL) was made according to the current guidelines for screening and management of the specific diseases” with reference to Funder et al, 2016) |

a

AUC

Using metabolites: 80% Using metabolite ratios: 77% bSpecificity for secondary hypertension: Using metabolites: 45% Using metabolite ratios: 37% aCalculated based on the performance of the top 15 metabolites bSensitivity/specificity was reported for differentiation of several forms of secondary hypertension (PA, PPGL, and CS) from primary hypertension |

Classical approach: When comparing primary hypertension and PA, 35 metabolites and 7 metabolite ratios had a significant association with the clinical diagnosis after controlling for sex and age group Machine-learning approach: When comparing primary hypertension and PA, 28 metabolites and 12 ratios were seen as key identifiers |

| Eu Jeong Ku et al, 2021 (96) Prospective multicenter study Targeted metabolomics on serum samples using LC-MS/MS with machine-learning algorithms for differentiation of PA, CS, or NFA (Decision tree, random forest, extreme gradient boost) |

NFA: 73 CS: 30 PA: 40 |

PA was screened using the ARR, with a cut-off value of 30. Positive ARR patients (ARR ≥30) were investigated using 1 or more confirmatory tests including: saline infusion or a high salt loading. PA was defined when aldosterone was not suppressed during confirmatory suppression testing |

Test cohort data:

AUC for PA: a 0.838, b0.933, c0.881 AUC for CS:a0.776, b0.925, 0.911c Sensitivity for PA:a88%, b93%, c95% Sensitivity for CS:a40%, b93%, c93% Sensitivity for NFA:a89%, b99%, c99% Specificity for PA:a92%, b100%, c99% Specificity for CS:a99%, b99%, c99% Specificity for NFA:a69%, b93%, c96% aDecision tree bRandom forest cExtreme gradient boosting |

There were 15 adrenal steroids simultaneously analyzed with each model, with 3 being classified as important discriminator of either NFA, CS or PA: tetrahydrocortisone, 18-hydroxycortisol, and dehydroepiandrosterone No validation cohort was included in the analyses |

| Kaneko et al, 2021 (97) Retrospective cross-sectional study Targeted metabolomics on serum samples using LC-MS/MS, with machine-learning algorithms for differentiation of unilateral PA and bilateral PA (Logistic regression, support vector machines, random forests, and extreme gradient boosting) |

Total PA patients: 229 Unilateral PA: 91 Bilateral PA: 138 Test cohort patient criteria |

For PA diagnosis: Patients were diagnosed with PA according to guidelines of the Japan Endocrine Society (98) and Japanese Society of Hypertension (99) with confirmation of diagnosis with at least 1 confirmatory test (captopril challenge or saline infusion test) For lateralization: AVS with ACTH stimulation (selectivity index >5, lateralization index ≥4). |

For Unilateral PA prediction:

Test cohort data: AUC: a0.948, b0.966, c0.990, d0.976, e0.95 Sensitivity:a83.3, b66.7, c94.4, d72.2, e83.3% Specificity:a92.9, b96.4, c96.4, d96.4, e92.9% Validation cohort data: AUC: a0.877, b0.875, c0.872, d0.848, e0.826 Sensitivity:a69%, b65.5, c69%, d69%, e72.4% Specificity:a94.5%, b95.6, c94.5%, d94.5%, e89.1% aLogistic regression bSupport vector machines cRandom forest dExtreme gradient boosting eOptimized random forest model |

The optimized random forest model was developed with 3 variables: serum potassium, plasma aldosterone concentration, and serum sodium levels |

| Diao et al, 2021 (100) Retrospective Development of a machine-learning model based on up to 79 clinical indicators for subtype diagnosis of either primary aldosteronism, renovascular hypertension, Thyroid dysfunction or aortic stenosis (extreme gradient boosting model) |

Renovascular hypertension: 505 PA: 400 Thyroid dysfunction: 139 Aortic stenosis: 71 |

Not specifically defined. |

For PA prediction

Test cohort data: AUC: 0.961 Sensitivity: 83.6% Specificity: 95.9% Validation cohort data: AUC: 0.965 Sensitivity: 84.4% Specificity: 93.0% |

For the PA model, 21 clinical indicators were used with the top 10 being: Upright ARR, serum potassium, supine ARR, supine plasma aldosterone, upright plasma aldosterone, glycated hemoglobin, nifedipine, albumin to creatinine ratio, 24-hour urinary aldosterone, serum sodium |

| Burrello et al, 2021 (101) Retrospective Development of several machine-learning diagnostic models and a 16-point Primary aldosteronism confirmatory testing (PACT) score using machine-learning and regression analysis to discriminate patients with a confirmed diagnosis of PA |

PA: 1024 | PA was screened using the ARR (developmental cohort, ie, training and internal validation: aldosterone to renin activity or in the external validation cohort: aldosterone to direct renin concentration) with cut-offs of an ARR >30 ng/dL/ng*mL−1*h−1 and aldosterone concentration higher than 10 ng/dL for a positive screen PA was confirmed by either an intravenous saline loading test or a captopril challenge test Subtype diagnosis (lateralization) was determined by CT imaging and AVS |

With a score of ≥8

Training cohort data: AUC: 0.879 Sensitivity: 92.2% Specificity: 71.0% Validation cohort data: AUC: b0.877 Sensitivity:a91.9%, b78.6% Specificity:a73.3%, b83.9% aInternal validation (Turin, Italy) bExternal validation (Munich, Germany) |

The 6 parameters that were selected by regression analysis included: female sex, antihypertensive medications, plasma renin activity at screening, aldosterone at screening, lowest potassium, and organ damage For patients with a score <5, PA diagnosis was excluded without a confirmation test; for patients with a score ≥13, PA diagnosis was confirmed without further tests. |

| Burrello et al, 2020 (102) Retrospective Supervised machine-learning algorithms and regression models were used to develop and validate 2 prediction models (Linear discriminant analysis and random forest), and a CLR score—a 19-point score system to distinguish unilateral PA from bilateral PA in cases of a unilateral successful AVS procedure, with the presence of contralateral suppression of aldosterone secretion |

Patients who successfully underwent AVS: 158 Unilateral PA: 126 Bilateral PA: 32 |

PA was screened using the ARR (aldosterone to plasma renin activity ratio) with a cut-off of 30 ng/dL/ng*mL−1*h for a positive screen PA was confirmed by either an intravenous saline loading test or a captopril challenge test Subtype diagnosis (lateralization) was determined using CT imaging and AVS where an adrenal nodule was reported if a mass of >8 mm was evident AVS was performed both under basal conditions (selectivity index ≥3) or with ACTH stimulation (selectivity index ≥5). Diagnosis of unilateral disease was determined by presence of a lateralization index of at least 4 |

For discrimination of unilateral PA vs bilateral PA

AUC: c 0.971: Generated from the combined cohort (training and external validation n = 158) Training cohort data: Sensitivity:a90.6%, b95.8%, c95.5% Specificity:a99.4%, b94.9%, c100% External validation cohort data: Sensitivity:a84.7%, b83.6%, c94.7% Specificity:a84.2%, b80%, c90% aLinear discriminant analysis bRandom Forest cCLR scoring system with best accuracy (>11) |

In the training cohort, a CLR score greater than 11 displayed the greatest accuracy (96.4%) |

| Eisenhofer et al, 2020 (103) Retrospective Targeted metabolomics of serum samples, with machine-learning analysis (random forest or a nonlinear radial basis function kernel [SVM]) for identification and subtype classification in PA particularly for patients with unilateral adenomas due to pathogenic KCNJ5 sequence variants |

PA: 273 Bilateral: 134 Unilateral: 139, of whom 58 had an APA due to KCNJ5 variant, and 81 did not |

PA was screened for using the ARR (cutoffs used not clearly defined). PA was confirmed using 1 or more of the endocrine society recommended confirmatory tests (oral salt loading test, saline infusion test, fludrocortisone challenge test, Captopril challenge test—specifics not clearly defined) Subtype diagnosis (lateralization) was determined using AVS under basal nonstimulated conditions using a selectivity index of >2 and a lateralization index of >4 or alternatively >3 in the presence of contralateral suppression. |

For PA Prediction

Learning cohort data: a AUC: a0.815, b0.841 aSensitivity:a69%, b70% aSpecificity:a94%, b98% External validation cohort data: aAUC: a0.926, b0.875 aSensitivity:a85%, b78% aSpecificity:a100%, b97% For PA with KCNJ5 prediction Learning cohort data: AUC:a0.714, b0.909 bSensitivity:a46%, b85% bSpecificity:a97%, b97% Validation cohort data: AUC:a0.908, b0.991 bSensitivity:a83%, b100% bSpecificity:a98%, b98% aRandom forest bSVM |

An assortment of 7 steroids + the aldosterone to renin ratio showed improved effectiveness for PA diagnosis over either strategy alone Aldosterone, 18-oxocortisol, and 18-hydroxycortisol had the most discriminatory power although this was model dependent. A random forest model provided optimal performance for the classification of patients with and without PA, whereas an SVM model was optimal for patients with APAs due to KCNJ5 |

Abbreviations: ARR, aldosterone to renin ratio; CS, Cushing syndrome; LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry; NFA, nonfunctioning adenoma; PA, primary aldosteronism; PPGL, pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma.

A key challenge in the roll out of metabolomics for screening and diagnosing disease has been the generation of large quantities of data and its subsequent handling, analysis and interpretation (95). While, on the one hand, this presents an opportunity to better understand the pathophysiology of PA and to develop more sensitive and specific tools for diagnosis, on the other hand, it also represents a significant challenge in terms of the accuracy of interpretation and subsequent categorization of disease. This challenge is being increasingly addressed using machine learning to analyze and interpret data generated from metabolomics studies with greater efficiency, consistency, and accuracy.

Machine learning requires careful design, training and validation. Appropriate algorithms must be chosen and optimized to best match the data and the analysis. Ideally the performance of machine learning–based analysis should be tested against, and compared with, human expert analysis. In turn, the quality of the outputs provided by machine learning–based analysis is reliant upon (1) robust study design at the outset, (2) the input of high-quality data that has been collected appropriately, (3) the reference standards against which the machine learns, (4) the availability of sufficient numbers of samples in training, and (5) appropriately selected/recruited verification cohorts. Prior to mainstream clinical use, properly carried out prospective validation studies, in accordance with the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) guidance, are required (104). In the context of the screening and diagnosis of PA, the current diagnostic tests and reference standards, against which metabolomic datasets are trained for interpretation by machine learning, are not yet supported by high quality evidence as previously discussed in “Screening, Diagnosis, and the Spectrum of Disease.” Secondly, the performance of traditional diagnostic testing is variable and diagnostic thresholds do not generally recognize the likely full spectrum of disease represented by PA.

Steroid metabolomic profiling

Steroid metabolomic profiling has been used clinically for many years to aid in the diagnosis of disorders of adrenal biosynthesis and metabolism (105). It has also gained widespread clinical use in the analysis and detection of patterns of steroid metabolite excretion which reveal the use of performance-enhancing drugs in sport (106, 107). The more mainstream options for steroid metabolomic assays are gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS/MS) or liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The former is a labor-intensive and expensive technique, requiring significant expertise and set-up, and which is limited to a handful of international centers. In contrast, LC-MS/MS, a high-throughput technique which is more widely available, provides precise, well-validated, clinical laboratory–based assays for large steroid metabolite panels in both urine and blood. Detailed steroid metabolomic profiling of functioning adrenal tumors, supported by machine-learning analysis has advanced significantly over the past decade. Arlt et al, first used this approach to define the metabolomic signature of ACC when compared with benign functioning adrenocortical adenomas, including PA (92). This was followed by a prospective, multicenter Evaluation of Urine Steroid Metabolomics for the Differential Diagnosis of Adrenocortical Tumours (EURINE-ACT) which combined spectrometry-based urinary steroid metabolite profiling and machine learning–based data analysis for detection of malignant lesions (108). The optimum diagnostic performance for the detection of malignant ACC in this study was superior to radiologic characterization combined with traditional biochemistry. The combined criteria: tumor diameter >4 cm, unenhanced CT tumor attenuation greater than 20 HU, and machine-learning analysis of urine steroid metabolomics achieved a positive predictive value of 76.4% and a negative predictive value of 99.7%. This study was a prospective validation of a prior study which compared the performance of a wider GC-MS panel when compared with a smaller, high-throughput LC-MS/MS steroid metabolite panel and, as such, provides a useful model for future studies of metabolomics in PA and hypertension. A generalized linear model was used to determine an overall score for ACC diagnosis rather than individualized interpretation of each steroid metabolite. The findings of this study preceded an evaluation of the ability of metabolomic profiling to predict the recurrence of ACC, in the presence of corticosteroid replacement and mitotane therapy (which interfere with the interpretation of blood-based assay of cortisol and cortisol metabolism) (93). A smaller number of patients with ACC had longitudinal, 24-hour urine collections for urine steroid metabolomics from prerecurrence and postrecurrence states. Blinded analysis of steroid metabolomics alone by 3 clinical experts detected 69% to 92% of recurrence by the time of radiological diagnosis, where preoperative urine samples were available. There was significant variability in the sensitivity of recurrence diagnosis when interpreted by clinical experts. However, machine learning was consistent in picking up 75% of recurrence, without the variability of sensitivity when challenged with the same data on multiple occasions. In this study, metabolomics outperformed imaging in 22% of patients where recurrence was detected by metabolomics 2 months in advance of radiological recurrence. The study was small and the data availability was incomplete and subject to selection bias often seen in early observational studies which evaluate the follow-up and outcomes of rare diseases. The findings of this study therefore need to be tested in a prospective, longitudinal manner in larger patient cohorts.

The importance of these studies is that they illustrate the potential of steroid metabolomics to accurately diagnose and distinguish with high specificity, between endocrinopathies which are driven by steroid-producing adrenal tumors. They also show the potential for machine learning to overcome observer bias in this context and to provide more consistent sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis, when compared with human interpretation. They demonstrate the opportunity for longitudinal monitoring of disease cure, recurrence, or progression in patients with an endocrinopathy of steroid hormone overproduction. They importantly highlight that steroid metabolomics, supported by machine learning, can be successfully used to overcome the difficulty of data interpretation in the face of interfering medications. But what about metabolomics in the context of hypertension and PA?

Metabolomic profiling of PA and hypertension

Investigation of metabolomic profiling in hypertension and PA is still at an early stage, with several retrospective studies examining 24-hour urinary steroid profiles, plasma steroid profiles, and unselected metabolomic panels. Arlt et al have also investigated the urinary steroid metabolite/metabolomic signature of PA and its subtypes. This study involved (1) a large exploratory cohort of patients with PA (103 UPA, 74 bilateral disease) and nonaldosterone producing adrenocortical adenomas (NAPACA) across subclinical Cushing (47 patients), overt adrenal Cushing syndrome (104 patients), nonfunctioning adrenal adenomas (56 patients) and healthy controls (162 individuals), and (2) a prospective validation cohort with PA (46 patients) (109). The GC-MS assay used detected higher levels of aldosterone and aldosterone metabolites in the urine of patients with a confirmed diagnosis of PA. Within this study, metabolomic profiling also demonstrated phenotypes of PA not previously recognized, whereby some degree of glucocorticoid cosecretion could be inferred from an excess of cortisol and total glucocorticoid metabolites in addition to the expected mineralocorticoid metabolite profile. In patients diagnosed with PA, the percentage difference in total glucocorticoid excretion relative to healthy controls was +25.0% (109). The authors coined the term “Connshing's syndrome” in order to describe this phenomenon. “Connshing's syndrome” was not associated with overt hypercortisolism/features of overt Cushing syndrome and patients demonstrating this metabolomic profile neither failed screening for Cushing syndrome with the overnight dexamethasone suppression test, nor did they demonstrate the typically suppressed adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) level associated with adrenal Cushing syndrome. Higher glucocorticoid metabolite levels in the urine of patients with PA was associated with higher CYP11B1 expression on immunohistochemistry and higher overall urinary cortisol and glucocorticoid metabolite levels than those seen in patients with subclinical Cushing. Higher glucocorticoid metabolites in the urine in PA was also accompanied by production of higher rather than lower androgen metabolites, in contrast to the typical androgen suppression associated with benign adrenal Cushing syndrome or mild autonomous cortisol secretion (110, 111). Post hoc correlation analysis across the total cohort identified an association between high glucocorticoid metabolite excretion and several markers of an adverse metabolic profile. The authors suggested that MRA alone within this subgroup of PA patients were sufficient to control hypertension and desuppress renin, but may not be sufficient to control a disease phenotype driven by aldosterone and cortisol. Resolution of the metabolomic abnormality for mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid metabolites was demonstrated following adrenalectomy in patients with UPA.

This pattern of steroid secretome/metabolome was not expected within the PA cohort and suggested that mild steroid cosecretion occurs at a frequency not previously anticipated. The study was appropriately designed and powered to distinguish between PA, other adrenal endocrinopathies and healthy controls. A well-validated GC-MS metabolomic assay system was used within an internationally recognized center. There was however a degree of selection bias in the recruited subjects, which favored patients with UPA and overt Cushing syndrome when compared to the typical prevalence of UPA within the spectrum of PA, and the prevalence of endocrinopathy in the setting of an adrenal nodule. The confirmatory cohort all had a diagnosis of PA. The study did not directly examine the potential effects of medication interference on the diagnosis of PA using steroid metabolomics. Finally, the study was not designed nor powered to address the clinical significance of the glucocorticoid metabolite cosecretion in patients with PA, and as such assigning the name Connshing syndrome may be premature until further prospective studies are carried out to add clarity to the true clinical significance of what is, in essence, a biochemical entity. Nonetheless, this study has provoked discussion relating to the greater PA disease spectrum and the possibility of greater disease diversity of PA which may explain metabolic disease, cardiovascular outcomes and sleep apnea in this population (109).

While Arlt and colleagues have demonstrated high mineralocorticoid metabolite levels in the urine of patients with PA, other authors have described challenges with this technique. In general, GC-MS rather than LC-MS/MS is used for the detection of mineralocorticoid and aldosterone metabolites in urine. Due to their low concentration in the urine, these can fall below the lower limits of assay detection using standard analysis in many commercial laboratories. As a consequence, many patients with PA may demonstrate a normal profile and are indistinguishable from primary hypertension at baseline, and in the absence of salt loading. This highlights the reliance upon machine sensitivity and the specific technical expertise required to run these assays which makes their current availability more challenging.

Urine analysis offers the convenience of noninvasive sampling and sample stability for screening (or diagnostic) samples which have been collected in locations remote from the analyzing laboratory. It also provides measurements reflective of a longer period of time. However, urine sampling requires adherence to a sampling procedure over 24 hours and is not always convenient for, or properly collected by, patients. In this regard, a more detailed steroid analysis of a single blood sample collected at the time of ARR screening offers the potential to conveniently and accurately diagnose PA. In a study using targeted plasma steroid metabolomics (LC-MS/MS), analyzed using machine learning, Eisenhofer et al, (103) demonstrated the utility of a multianalyte steroid profile drawn at the time of ARR measurement: (1) to distinguish between primary hypertension and PA with greater sensitivity and specificity than the ARR alone and (2) to identify patients with unilateral adenomas, driven by KCNJ5 mutations vs KCNJ5 wildtype. A score derived from a total combination of 7 steroids was useful in stratifying PA subtypes. The top 3 ranking steroids were consistently identified as aldosterone, 18-oxocortisol, and 18-hydroxycortisol. Patients with KCNJ5 mutations demonstrated considerably higher levels of all 3 steroids than other PA subtypes. While this steroid combination had previously been identified as distinguishing between PA and primary hypertension, this study differed from others in using machine learning (random forest model) to interpret the results of the plasma steroid profile combined with the ARR. The area under the receiver operated curve was higher using the machine-learning analysis when than ARR alone for distinguishing PA from primary hypertension (0.92 [0.899-0.946] vs 0.89 [0.856-0.916]) and considerably higher for identifying UPA driven by KCNJ5 mutations vs primary hypertension and all other PA (area under the curve: 0.95 [0.922-0.969] vs 0.817 [0.758-0.863]) (Table 4). Albeit retrospective, this was a well-executed study which was designed and powered from the outset to address the ability of steroid profiling to identify and classify subtypes of PA. The machine-learning approach was carefully developed and the validation cohort yielded similar results to the initial test cohorts. Within the overall participant patient group however, there was a selection bias towards UPA (60%), probably reflective of the centers from which patients were recruited. The study was retrospective, with analysis performed on biobanked samples. Traditional standards of diagnosis for PA across multiple recruitment-sites were used (see “Screening, Diagnosis, and the Spectrum of Disease”) and the machine-learning algorithm was trained against these data, with consequent unavoidable heterogeneity. However, the results of the study were validated against surgical outcome data, which were available for a large number of patients with UPA (157/304 PA patients) who had undergone adrenalectomy. The authors concluded that their findings highlight the potential for the metabolomic model, supported by machine learning, to identify patients who would benefit most from surgical intervention (103). They also contended that biochemical distinction between unilateral and bilateral forms of PA, particularly in identifying KCNJ5 mutations may facilitate improved confidence in the interpretation of adrenal CT as a lateralization modality.

In another study by the same researchers, plasma metabolomic steroid profiling was combined with plasma metanephrines and tumor size on CT in an effort to distinguish between the underlying pathologies of different types of adrenal incidentaloma including ACC, pheochromocytoma, and APA (112). While this was again a retrospective study, it demonstrated in a similar manner to EURINE-ACT, how the combination of radiology and steroid metabolomics offers the potential for development as a powerful tool to diagnose and distinguish between different pathologies of adrenal tumors. In this study APA was again characterized by elevated aldosterone, 18-oxocortisol and 18-hydroxycortisol. ACC was distinguishable by 11-deoxycortisol, 11-dexoycorticosterone, 17-hydroxyprogesterone, androstenedione, and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate. When combined with cortisol, corticosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, and plasma metanephrines, this metabolomic panel plus tumor size demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing between pheochromocytoma, PA, and other adrenal tumor types. Overall, subtype classification of adrenal incidentalomas demonstrated optimized sensitivities for ACC, PA, and pheochromocytoma of 83.3% (66.1-100%), 90.8% (83.7%-97.8%), and 94.8% (89.8%-99.8%), respectively, with specificities of 98.0% (96.9%-99.2%), 92.0% (89.6%-94.3%), and 98.6% (97.6%-99.6%), respectively (Table 4) (112). Acknowledging that this study was again retrospective, the data are compelling when taken in context of other studies such as EURINE-ACT and earlier studies by Eisenhofer et al, that plasma and/or urine steroid metabolomic panels offer greater sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing APA with a higher degree of accuracy than traditional approaches. In this study plasma profiling was used which, as highlighted previously, does not offer the ease of sample collection or analyte stability upon storage when compared with urinary analysis (91). It may also be argued that the current diagnostic pathway is sufficient for distinguishing between ACC, APA, and pheochromocytoma with a high degree of accuracy, using readily available and relatively cheap tests combined with clinical judgment. The challenge with the diagnosis of PA does not usually arise from distinguishing between it and other types of adrenal incidentalomas, but rather in differentiating between primary hypertension and PA.

In this regard, Erlic et al, tested plasma metabolomic analysis using a large “off the shelf” LC-MS/MS–based assay system to distinguish between primary and endocrine hypertension. The principal aim of the study was to identify a prescreening panel which could be measured in a single plasma sample and which would identify patients suitable for further more specific screening/investigation for endocrine hypertension, including PA, Cushing (ACTH-dependent and -independent), and pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma. This investigation used targeted metabolomics in an unselected and exploratory manner rather than using steroid metabolites or other analytes specific to the underlying pathology of different types of endocrine hypertension. The metabolomic panel used an unselected set of 188 metabolites (157 of which were detectable and included in the analysis) across acylcarnitines, biogenic amines, and glycerophospholipids. A classical statistical approach, using regression analysis was compared with a machine-learning, random forest approach, with similar results. Physician interpretation of the results was not undertaken (95). When comparing primary hypertension and PA, the machine-learning model selected 28 metabolites and 12 metabolite ratios which could differentiate between the 2 (Table 4). However, there was considerable overlap between metabolites across the various forms of endocrine hypertension and distinction between different types of endocrine hypertension could not be made. Overall, the best performance of this analysis compared primary hypertension against the composite outcome of all endocrine hypertension (PA, Cushing syndrome, and pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma inclusive). The analysis selected distinguishing metabolites and built a receiver operating characteristic curve using machine learning and classical statistical analyses, which provided respective areas under the curve (AUC) values of 0.83 and 0.86 (95% CI 0.806-0.907) for the differentiation of primary from composite endocrine hypertension. While the study identified differences between the endocrine and primary hypertension groups, the results are exploratory and preliminary, and need to be prospectively validated. The overall study cohort was small and probably underpowered to detect true differences between the study groups, given (1) the number of analytes investigated, (2) the number of study groups (4 in total), and (3) the need for training and validation cohorts within the machine-learning group. The cohort also demonstrated a selection bias towards endocrine hypertension, reflective of the clinical centers from which patients were recruited. There was a sex bias within certain groups, which may have affected the findings of the study. Diet and smoking were not taken into account in the analysis, which could be considered a weakness given the metabolites which were measured. Finally, as a prescreening approach, the analysis required an LC-MS/MS analysis on a plasma sample, which was expensive, difficult to analyze and which would not overcome the multiple sample processing challenges which currently limit screening in primary care, such as sample storage and sample stability at room temperature.

When taken together, the cumulative findings of the studies presented here and in Table 4 suggest that a combined approach which employs metabolomics, tumor size, and character on CT, and analyzed using machine learning offers the prospect of improving diagnostic efficiency for PA and distinguishing primary and endocrine hypertension. This combination approach may also offer the prospect of better informing intervention or even personalizing therapy (medical or interventional) for PA (as well as other forms of hypertension) to achieve the best individualized patient outcome. In the context of urinary collection, there is a clear benefit in patients providing samples with relative ease, which reflect a 24-hour or overnight time-course and which remain analytically stable, such that they can be collected (with very little processing) in locations remote from the analyzing laboratory, such as primary care. However, while encouraging, these studies must be interpreted with caution. The majority are retrospective and exploratory. There is therefore a significant need to test these diagnostic approaches prospectively in large multicenter studies, which are informed by clinical outcomes. Prior to further investigation there is also a pressing need for consensus to standardize the current diagnostic approach for PA, such that future diagnostic studies using a combined approach can be compared to a robust gold standard (discussed previously in “Screening, Diagnosis, and the Spectrum of Disease”).

Machine learning to interpret traditional parameters

The use of machine learning to interpret clinical and laboratory parameters that are routinely collected during the initial assessment and diagnostic work-up of hypertension could help practitioners in primary and nonspecialist care to identify patients who should be offered screening for PA and referral for specialist care and/or confirmatory testing. This may improve patient outcomes and direct resources more appropriately. However, any use of machine learning must be prospectively analyzed and must show clear and consistent benefit over clinical decision-making alone. Additionally, any machine-learning approach must be clearly interpretable and designed to simplify the diagnostic pathway, rather than adding a layer of complexity.