Abstract

Objectives:

To determine the number of top-ranked U.S. academic institutions that require ethics consultation for specific adult clinical circumstances (e.g., family requests for potentially inappropriate treatment) and to detail those circumstances and the specific clinical scenarios for which consultations are mandated.

Design:

Cross-sectional survey study, conducted online or over the phone between July 2016 and October 2017.

Setting:

We identified the top 50 research medical schools through the 2016 U.S. News and World Report rankings. The primary teaching hospital for each medical school was included.

Subjects:

The chair/director of each hospital’s adult clinical ethics committee, or a suitable alternate representative familiar with ethics consultation services, was identified for study recruitment.

Interventions:

None.

Measurements and Main Results:

A representative from the adult ethics consultation service at each of the 50 target hospitals was identified. Thirty-six of 50 sites (72%) consented to participate in the study, and 18 (50%) reported having at least one current mandatory consultation policy. Of the 17 sites that completed the survey and listed their triggers for mandatory ethics consultations, 20 trigger scenarios were provided, with three sites listing two distinct clinical situations. The majority of these triggers addressed family requests for potentially inappropriate treatment (9/20, 45%) or medical decision-making for unrepresented patients lacking decision-making capacity (7/20, 35%). Other triggers included organ donation after circulatory death, initiation of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, denial of valve replacement in patients with subacute bacterial endocarditis, and posthumous donation of sperm. Twelve (67%) of the 18 sites with mandatory policies reported that their protocol(s) was formally documented in writing.

Conclusions:

Among top-ranked academic medical centers, the existence and content of official policies regarding situations that mandate ethics consultations are variable. This finding suggests that, despite recent critical care consensus guidelines recommending institutional review as standard practice in particular scenarios, formal adoption of such policies has yet to become widespread and uniform.

Keywords: clinical protocols, ethics committees, ethics consultation, healthcare surveys, terminal care, withholding treatment

Hospital ethics committees exist to address perceived gaps in providing moral, ethically justified medical treatment, especially in medically and ethically complex cases, and are thus particularly relevant to the practice of critical care (1). Traditionally, ethics committees depend on clinicians, patients, and families to exercise their judgment and discretion in reporting potentially appropriate situations for committee review. These decisions to consult the committee are typically optional on the part of the reporting parties (2).

One approach to promote the consistent implementation of ethical principles and expert guidance in ethically fraught or complex cases is for hospitals to institute policies that mandate ethics consultation when specific clinical situations arise. Several examples of such “trigger” situations have been recommended by multiple professional societies relevant to ICUs and the medical ethics literature. A multi-society statement with approval from various critical care societies, including the Society of Critical Care Medicine, recommends that early expert ethics consultation should be uniformly initiated when surrogate decision-makers request what may be perceived by the medical team as potentially inappropriate medical treatments for patients who lack capacity (3). In addition, the American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics states that, for incapacitated patients, clinicians should “…seek consultation through an ethics committee or other appropriate resource in keeping with ethics guidance…” in cases of: 1) physician-surrogate disagreements around withdrawing life-supporting treatment, 2) patients who lack a surrogate decision-maker (i.e., decisions to limit life support for unrepresented patients), and 3) staff concerns that a surrogate may be acting against the known values of the patient (4). Regarding decisions to limit life support for unrepresented patients (those who lack capacity and do not have a surrogate decision-maker or advance directive), one ICU study estimated that such decisions are currently made by the physician alone 89% of the time without formal review by an ethics committee or court of law (5). This study’s authors and others argue that lack of discussion of such significant decisions with additional stakeholders including ethics consultants may potentially render the care of unrepresented patients vulnerable to individual provider biases (6).

Prior survey studies of ethics consultation services in the United States have mostly focused on establishing the prevalence of ethics consultations services among U.S. hospitals, understanding the background and training of ethics team members, and characterizing how these teams meet and conduct consultations (7). To date, there has not been an attempt to understand hospital policies with regards to specific situations in which an ethics consultation is considered by an institution to be nonoptional. In this study, we examined mandatory ethics consultation policies of the top-ranked academic teaching hospitals in the United States. We aimed to determine the prevalence of these mandatory policies and the clinical situations in adult medicine that they address, the process by which these committees identify and document these consultations, and potential variability in processes and policies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Summary of Study Design and Ethics Exemption Statement

We used a cross-sectional survey study design. This study was submitted to the Yale University Human Investigation Committee and was determined to be exempt from formal review. Study recruitment and survey completion occurred between July 2016 and October 2017.

Setting/Participants

We contacted a representative of the adult ethics committee for the primary academic teaching hospital of each medical school listed in the top 50 of the 2016 U.S. News and World Report Best Medical Schools: Research Ranking (8). We focused on these institutions from a publicly available ranking to characterize practices at referral centers where complex medical and ethical scenarios in the community may often be transferred. The director or chair of each hospital’s consultation service or a suitable alternative was identified through institution websites, calls to ethics departments, and correspondence with hospital staff. Once identified, potential participants were contacted by a single study investigator (J.B.N.) via both phone and e-mail. Once informed of the study purpose, survey duration, and confidentiality/data storage protocols, participants indicated verbal consent for participation in the survey either by phone or via online correspondence. No incentives were provided for participation.

Variables/Data Sources/Measurement

For data collection, we developed a survey with 14 questions that asked participants to report on several topics related to mandatory ethics consultations at their respective hospitals: whether their hospitals had a policy or policies for mandatory ethics consultations in place, either currently or in the past; whether such policies were in place for perceived legal requirements; how the consults mandated by such policies were operationalized; and the clinical situations for which such policies had been put in place. For those centers that reported having written mandatory policies, the survey requested that participants provide us with a copy of the policy if they were able to do so, with reassurances that the institution associated with each policy would be kept confidential by our team. Of note, the exact meaning of the term “mandatory” was otherwise left open-ended in the survey so that the study would err on the side of being inclusive with regards to collected data. The survey questions underwent an iterative review and revision process among the authors, including ethicists and critical care clinicians at four academic teaching hospitals, to optimize content and face validity. The full text of the final survey version is available in the supplemental document (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/F452).

The survey was first piloted as a phone interview among 12 participants, with responses manually entered into a Qualtrics (Provo, UT) form by a single study investigator (J.B.N.). After feedback from participants during this initial pilot period, all remaining participants in the study were given the option to complete the survey either over the phone or online (through a Qualtrics link). If the participant preferred completing the survey over the phone, the study investigator entered the responses directly into Qualtrics. No additional changes were made to the content of the survey following the initial piloting and feedback period.

In addition, general characteristics of the 50 hospitals targeted in this study were collected from 2016 to 2017 U.S. News and World Report Best Hospitals Rankings and Ratings website (9).

Bias

To minimize nonresponse bias, we made at least three attempts by phone and/or email to contact the appropriate individual for each hospital. We collected hospital characteristic data for both participating and nonparticipating institutions for the purposes of comparison.

Study Size

We specifically designed this study to be a cross-section of major U.S. teaching hospitals. As mentioned above, we focused on the top 50 research institutions from publicly available rankings to characterize practices at referral centers, where complex medical and ethical scenarios in the community may often be transferred.

Statistical Methods

Survey responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics for categorical data, with chi-square analyses for comparing hospital characteristics between participating and nonparticipating institutions conducted in Stata Statistical Software: Release 12 (College Station, TX). All survey responses were included in the analysis, including those from incomplete surveys that were completed directly online. For free-text survey responses where participants described situations in which ethics consultations were mandated, all responses were reviewed by two members of the study team (J.B.N., D.Y.H.), and a qualitative analysis was performed to assign the protocols into thematic categories. All of the written protocols received by our team were also reviewed in full by two members of the study team (J.B.N., D.Y.H.), with special attention to the exact language in the protocol where ethics consultation was expressed as being “mandatory.”

RESULTS

We were able to identify a representative from the ethics consultation service at each of the 50 hospitals. Of the 50 sites, 36 (72%) consented to participate, 12 (24%) did not respond, and two (4%) declined to participate. Table 1 lists institutional characteristics of the 36 participating sites and lists characteristics of the 14 nonparticipating sites for comparison. In comparison to the cohort of nonparticipating centers, the cohort of participating centers trended toward a higher proportion of large metropolitan hospitals (83% vs 50%; p = 0.05 across hospital types) and a lower proportion of hospitals in the U.S. West region (14% vs 43%; p = 0.04 across all regions). We did not detect a statistically significant difference in hospital bed count or volume of annual admissions between participants and nonparticipants. Among the 36 participating sites, 13 (36%) did so by phone and 23 (64%) did so by direct online survey.

TABLE 1.

Institutional Characteristics of Survey Participants and Nonparticipants

| Characteristic | Participants, n = 36, n (%) | Nonparticipants, n = 14, n (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital type | 0.05 | ||

| Large metro | 30 (83) | 7 (50) | |

| Large rural | 2 (6) | 3 (21) | |

| Medium metro | 4 (11) | 4 (29) | |

| Bed count | 0.40 | ||

| < 500 | 5 (14) | 4 (29) | |

| 500–999 | 19 (53) | 8 (57) | |

| 1,000–1,500 | 9 (25) | 2 (14) | |

| > 1,500 | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | |

| Region | 0.04 | ||

| Midwest | 11 (31) | 1 (7) | |

| Northeast | 12 (33) | 2 (14) | |

| South | 8 (22) | 5 (36) | |

| West | 5 (14) | 6 (43) | |

| Annual admissions | 0.60 | ||

| < 25,000 | 6 (17) | 3 (21) | |

| 25,000–50,000 | 20 (56) | 9 (64) | |

| > 50,000 | 10 (28) | 2 (14) |

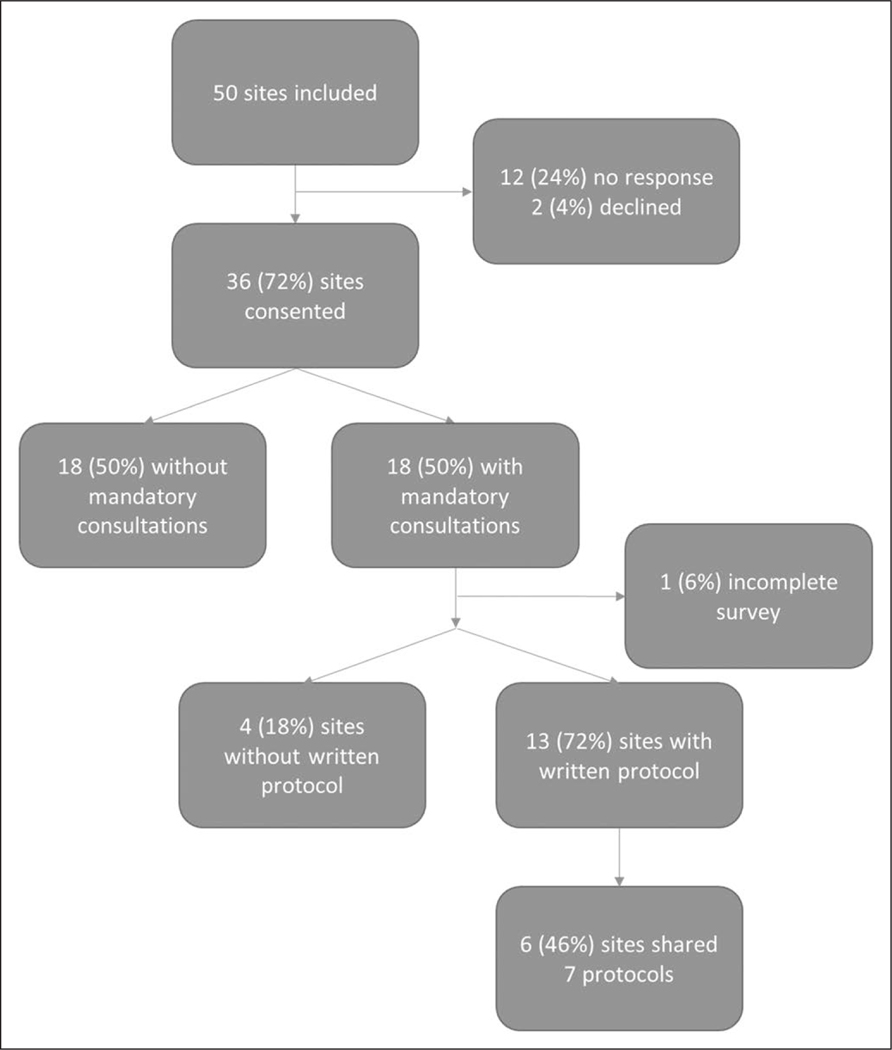

Of the 36 sites that participated, 18 (50%) reported that at least one clinical situation required a mandatory consultation from the adult ethics committee at their institution (Fig. 1). Of the 18 surveys reporting a mandatory policy, one online survey was submitted incomplete for all remaining survey questions. Among those sites that reported not having a current policy, three sites reported that a previous policy was discontinued due to obsolescence, interference with the delivery of care, or a change in legal requirements.

Figure 1.

Participation flowchart. Of the 18 surveys that had a mandatory policy, one online survey was submitted incomplete for all remaining survey questions.

For the 18 sites reporting a mandatory policy, Table 2 highlights several survey questions that address the circumstances surrounding these consultations. Half of participants (9) stated that their policies addressed specific requirements in state law. Eleven sites (61%) reported that a mandatory consult must be formally completed once triggered, while six (33%) reported that a triggered consult could subsequently be canceled based on the judgment of the primary clinical or ethics consultation team. All sites, aside from the one incomplete survey, reported that documentation of a completed consult was included in the patient hospital medical record, and seven (39%) sites also maintained separate documentation among internal ethics committee records. Only a single site (6%) reported that their committee received financial support to enable proactive screening by the ethics team for mandatory consult situations.

TABLE 2.

Nature of Mandatory Consult Policies

| Question Responses | n | % Mandatory |

|---|---|---|

| Does your mandatory consultation policy address requirements presented by state law? | ||

| Yes | 9 | 50 |

| No | 4 | 22 |

| Not sure | 4 | 22 |

| Not answered | 1 | 6 |

| Where are mandatory consultations documented (medical record, committee documents, other)? | ||

| Medical record | 10 | 56 |

| Medical record and committee docs | 7 | 39 |

| Not answered | 1 | 6 |

| If a mandatory consult is triggered, does a formal consult need to be completed? | ||

| Must be completed | 11 | 61 |

| Can be canceled | 6 | 33 |

| Not answered | 1 | 6 |

| Does your ethics consultation service receive financial support to enable screening for potential mandatory consults? | ||

| Yes | 1 | 6 |

| No | 14 | 78 |

| Not sure | 2 | 11 |

| Not answered | 1 | 6 |

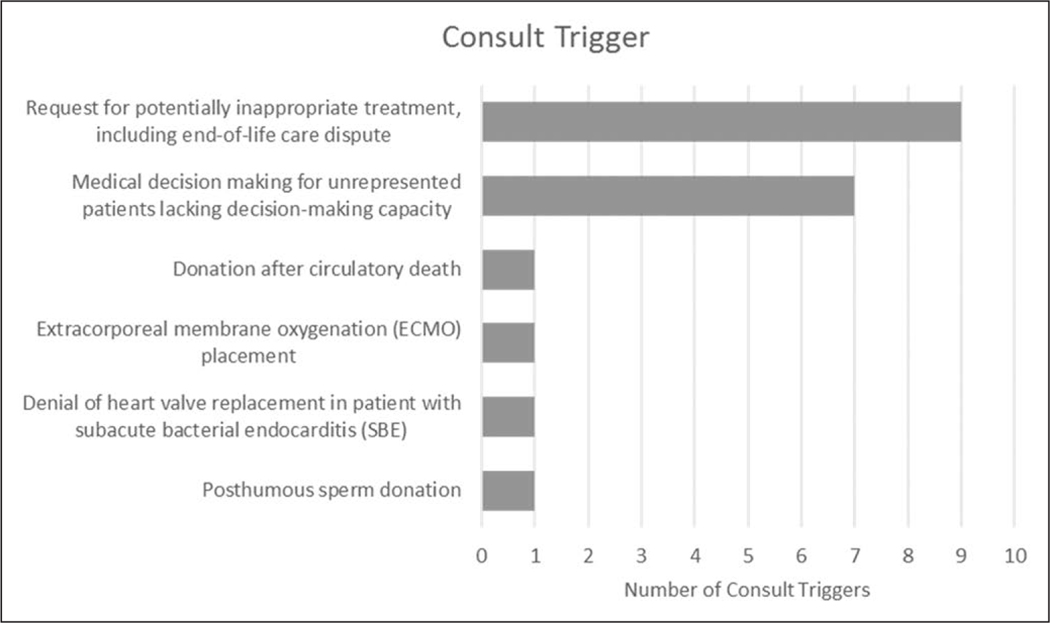

For institutions with mandatory policies in place, Figure 2 highlights the categorical themes of the triggers, or clinical situations, that were reported. Of the 17 sites that listed triggers, 20 trigger scenarios were provided, with three sites listing two distinct clinical situations. The majority of these triggers addressed family requests for potentially inappropriate care—including end-of-life care disputes (9/20, 45%)—or medical decision-making for unrepresented patients lacking decision-making capacity (7/20, 35%). Other triggers were only used at a single institution; they addressed organ donation after circulatory death, initiation of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, denial of valve replacement in patients with subacute bacterial endocarditis, and posthumous donation of sperm. All responses to the survey question regarding specific clinical triggers are listed in eTable 1 (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/CCM/F453) in full.

Figure 2.

Categories of mandatory consultation triggers. Twenty consult triggers were identified at 17 separate sites. Three sites had two unique consult triggers.

Of the 18 sites that reported a mandatory policy, 13 (72%) stated that written protocols existed. Of these 13 sites, six (46%) indicated in the survey that they would be willing to share a copy of the protocol. From this group, six institutions ultimately shared seven total protocols, as summarized in Table 3. In addition to the variety of clinical situations addressed, Table 3 summarizes specific language in the each of the collected policies that expresses its “mandatory” nature. Four addressed the request for potentially inappropriate treatment, including end-of-life care dispute. In addition, two addressed medical decision-making for unrepresented patients lacking decision-making capacity, and one addressed posthumous sperm donation. Six of the protocols used language that clearly indicated the consultation was “mandatory” (i.e., indicated by stating consultation “will,” “shall,” or “must” occur). One protocol simply stated that the consultation “should” occur for situations involving potentially inappropriate treatment. Of note, only one protocol, which addressed the specific situation where an external social worker proxy—for a patient lacking decisional capacity—requests to withdraw or withhold life-prolonging treatment, stated that contacting the ethics committee about such specific situations is mandated by state law.

TABLE 3.

Summary of Written Protocols

| Hospital Protocol | Reason for Mandatory Consult | Consult Trigger Category | Mandatory Language |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | “…attending physician objects to a surrogate’s decision to withhold or withdraw artificial feeding and hydration for an adult who is not terminally ill or permanently unconscious…” | Request for potentially inappropriate treatment, including end-of-life care dispute | “…in certain … circumstances must the Ethics Review Committee convene … when a patient lacks decision-making capacity.” |

| 2 | “…consensus regarding an order to withhold or withdraw treatment does not exist … or that a physician is unwilling to abide by a patient’s Advance Directive or the direction of the patient’s surrogate decision-maker…” | Request for potentially inappropriate treatment, including end-of-life care dispute | “An involved party should seek an ethics consultation…” |

| 3a | “Disagreements in determining what constitutes non-beneficial treatment may arise between the patient or patient’s surrogate and healthcare providers.” | Request for potentially inappropriate treatment, including end-of-life care dispute | “…attending physician shall request an ethics consultation.” |

| 3b | “…treatment decisions on behalf of persons who lack healthcare decision-making capacity and for whom there is no surrogate decision maker.” | Medical decision-making for unrepresented patients lacking decision-making capacity | “Ethics consultation will be obtained.” |

| 4 | “…situations which are not life-threatening emergencies, if the patient has no known relatives and none can be found after reasonable attempts to locate them…” | Medical decision-making for unrepresented patients lacking decision-making capacity | “…an Ethics consult shall be requested…” |

| 5 | “…decisions by external social workers serving as proxies if the proxy requests withdrawing or withholding of life-prolonging treatment.” | Medical decision-making for unrepresented patients lacking decision-making capacity | “A physician or designee on the case must email (from secure system) the chair of the Ethics Committee … as appropriate … the chair can agree with the decision to withdraw or withhold treatment.” |

| 6 | “Posthumous/live sperm procurement…” | Posthumous sperm donation | “Ethics committee consultation must be obtained…” |

Reasons for mandatory consults are quoted directly from submitted protocols. One institution submitted two separate protocols (3a and 3b).

DISCUSSION

Only half of the participating academic medical centers in our study reported that they had mandatory ethics consultation policies currently in place at their institution. We found significant variability in the types of clinical scenarios addressed by those policies. Within the written protocols that we were able to collect, the exact phrases used to indicate the extent to which consults are “mandated” were, for the most part, definitive. Only one institution reported having financial resources for the ethics team to proactively screen their hospital census for situations where conditions for a mandatory ethics consultation had been met.

Differences in patient populations served and the practical role of ethics committees across institutions likely contributes to the variability we found. However, we conducted this study in the context of professional consensus statements, including those published by critical care organizations, and other literature arguing that mandatory ethics team consultations should nevertheless be best practice for a number of common clinical scenarios (3, 4), given their potential value (10). To our knowledge, this study is the first to characterize the prevalence and nature of mandatory ethics consultation policies across U.S. hospitals. Romano et al (11) published a single center experience of implementing a mandatory ethics consultation policy for requests of removal of life support for patients who lack decisional capacity. This policy was enacted in accordance with state law, and it addressed all requests to discontinue life support in the ICU setting. The authors classified patients’ medical prognoses as “poor” or “terminal” in 89% of the sample of consults studied, with the most common indication for consultation being a request to withhold or withdraw treatment. Over the study period, there was an increase of 84% in ethics consultation volume. The authors suggested from their experience that implementing such a protocol may also have indirect benefits, including strengthening the clinical presence of ethics consultants and improving staff education on ethical issues. However, even in the case that a mandatory consultation policy is instituted, efforts must be made on an institutional level to raise awareness of the policy and to monitor compliance.

Regarding limitations of this study, we surveyed a focused cohort of academic medical centers and were not able to obtain responses from 28% of our prespecified cohort. We included an analysis of the characteristics of our nonparticipating sites to assess for some possible sources of bias, and we did find some differences between participating and nonparticipating institutions with regards to hospital type and U.S. region. We surmise that the low prevalence and high variability of mandatory ethics protocols among participating sites may allow one to infer a similarly low prevalence and high variability of such policies among the larger population of U.S. community and referral centers. However, given that we only targeted hospitals associated with the top 50 research medical schools in public rankings and experienced a 28% nonresponse rate, the generalizability of our results to community hospitals is nevertheless limited to some degree. In addition, we did not assess how long mandatory protocols have been in place or who were involved in the drafting of these protocols.

It should be noted that a hospital’s having a mandatory policy in place and the reliability of an ethics team being consulted for appropriate situations are likely related but two distinct questions, the latter of which our study does not fully address. Furthermore, this study also does not determine the specific training of individual committee members (12) or the quality (i.e., “value added”) of the consultations that they are able to provide (13).

We allowed broad latitude with regards to how the word “mandatory” was interpreted when asking whether their institutions had mandatory consultation policies in place. Exact interpretations of this word may have affected how sites responded to our survey, although the definition was intentionally kept broad in hopes of characterizing as many responses from sites as possible. In the written protocols we did receive, we found that the language used, to indicate that an ethics consultation was required for the given clinical situation, was mostly unequivocal. Finally, although 18 institutions reported having mandatory consultation policies in our study, only six ended up providing copies of their written protocols to us. Despite reassurances regarding our maintaining confidentiality for study participants, institutions nevertheless may have had a number of reasons to not share their written protocols; including concern regarding information identifying their institutions in their protocols, legal liabilities, hospital rules about external sharing of policies, and the perceived quality of their protocols.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study reveal the low prevalence and high variability of mandatory ethics consultation practices at academic regional referral centers, despite recent consensus ICU guidelines recommending early intervention of a multidisciplinary ethics team for multiple clinical situations (3, 4). Our study did not assess compliance with these protocols or monitoring of patient, family, or clinician outcomes associated with the associated ethics consultations. Understanding whether the ethics team members performing these consultations have been trained in published core competencies for consultants is critical (14). Additional investigation into barriers to creating and implementing these protocols would be insightful, although we suspect a combination of challenges relating to committee funding, training, staffing, competing priorities, and institutional support. We conclude more research is needed to determine the impact of implementing mandatory consultation policies on 1) the frequency of ethics teams being consulted at hospitals and within ICUs, with and without active screening by the ethics team for appropriate cases; 2) the compliance of hospital policies with the laws of their respective states; and 3) the perceptions of quality of care by clinicians, patients, and families.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Drs. Pearlman and Tolchin disclosed being government employees. Dr. White’s institution received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Institute of Nursing Research (including a K24 mentoring award [HL148314]), and he received funding from UptoDate. Dr. Tolchin’s institution received funding from U.S. Veteran Administration (VA) VISN1 Career Development Award and the VA Pain Research, Informatics, Multimorbidities, and Education Center of Innovation; he received funding from the C. G. Swebilius Trust; and he has received honoraria from Columbia University Medical Center, the International League against Epilepsy, and the American Academy of Neurology. Dr. Sheth received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Hwang received support from Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute and funding from Society of Critical Care Medicine Family Engagement Collaborative.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal).

The views expressed herein represent those of the author and not the government or Department of Veterans Affairs.

Written work prepared by employees of the Federal Government as part of their official duties is, under the U.S. Copyright Act, a “work of the United States Government” for which copyright protection under Title 17 of the United States Code is not available. As such, copyright does not extend to the contributions of employees of the Federal Government.

The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosner F: Hospital medical ethics committees: A review of their development. JAMA 1985; 253:2693–2697 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White DB, Curtis JR, Wolf LE, et al. : Life support for patients without a surrogate decision maker: Who decides? Ann Intern Med 2007; 147:34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosslet GT, Pope TM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. ; American Thoracic Society ad hoc Committee on Futile and Potentially Inappropriate Treatment; American Thoracic Society; American Association for Critical Care Nurses; American College of Chest Physicians; European Society for Intensive Care Medicine; Society of Critical Care: An official ATS/AACN/ACCP/ESICM/SCCM policy statement: Responding to requests for potentially inappropriate treatments in intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 191:1318–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Medical Association Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs: Opinions on caring for patients at the end of life. In: Code of Medical Ethics of the American Medical Association, Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 10.7.1. Chicago, American Medical Association, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 5.White DB, Curtis JR, Lo B, et al. : Decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment for critically ill patients who lack both decision-making capacity and surrogate decision-makers. Crit Care Med 2006; 34:2053–2059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pope TM: Making medical decisions for patients without surrogates. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:1976–1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox E, Myers S, Pearlman RA: Ethics consultation in United States hospitals: A national survey. Am J Bioeth 2007; 7:13–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.2016. U.S. News and World Report Best Medical Schools: Research Ranking. 2015. Available at: https://www.usnews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-medical-schools/research-rankings. Accessed June 13, 2016

- 9.2016-2017. U.S. News and World Report Best Hospitals Rankings and Ratings. 2016. Available at: https://health.usnews.com/best-hospitals/. Accessed August 21, 2017

- 10.Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD, et al. : Effect of ethics consultations on nonbeneficial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003; 290:1166–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romano ME, Wahlander SB, Lang BH, et al. : Mandatory ethics consultation policy. Mayo Clin Proc 2009; 84:581–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegler M: The ASBH approach to certify clinical ethics consultants is both premature and inadequate. J Clin Ethics 2019; 30:109–116 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bliss SE, Oppenlander J, Dahlke JM, et al. : Measuring quality in ethics consultation. J Clin Ethics 2016; 27:163–175 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarzian AJ; Asbh Core Competencies Update Task Force 1: Health care ethics consultation: An update on core competencies and emerging standards from the American Society For Bioethics and Humanities’ core competencies update task force. Am J Bioeth 2013; 13:3–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.