Abstract

The extraordinary and unique properties of persistent luminescent (PerLum) nanostructures like storage of charge carriers, extended afterglow, and some other fascinating characteristics like no need for in-situ excitation, and rechargeable luminescence make such materials a primary candidate in the fields of bio-imaging and therapeutics. Apart from this, due to their extraordinary properties they have also found their place in the fields of anti-counterfeiting, latent fingerprinting (LPF), luminescent markings, photocatalysis, solid-state lighting devices, glow-in-dark toys, etc. Over the past few years, persistent luminescent nanoparticles (PLNPs) have been extensively used for targeted drug delivery, bio-imaging guided photodynamic and photo-thermal therapy, biosensing for cancer detection and subsequent treatment, latent fingerprinting, and anti-counterfeiting owing to their enhanced charge storage ability, in-vitro excitation, increased duration of time between excitation and emission, low tissue absorption, high signal-to-noise ratio, etc. In this review, we have focused on most of the key aspects related to PLNPs, including the different mechanisms leading to such phenomena, key fabrication techniques, properties of hosts and different activators, emission, and excitation characteristics, and important properties of trap states. This review article focuses on recent advances in cancer theranostics with the help of PLNPs. Recent advances in using PLNPs for anti-counterfeiting and latent fingerprinting are also discussed in this review.

Keywords: Persistent luminescence, Nanophosphors, Cancer theranostics, Biomedical, Imaging, Security technologies, Anti-counterfeiting, Latent fingerprinting

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Luminescence is a term commonly used to describe the excitation of electrons using UV or visible radiation, whose energy is then emitted as visible light. The excitation source can be of a chemical, biological, or physical nature [1]. In this review, our focus is on radiation sources of a physical nature, for which the term photoluminescence would be used [2]. It is a process in which a molecule is excited using visible or ultraviolet photons, sending its electrons to excited electronic states. Photoluminescence can be categorized into two categories: one is fluorescence, which is a transition from a singlet excited state to a singlet ground state, thus being spin-allowed and hence causing instantaneous photon emission with a lifetime of the order of nanoseconds after excitation [3,4]. The second is phosphorescence, which is the phenomenon of delayed photon emission post-excitation caused by the transition from an excited triplet state to a singlet ground state; as this transition is not spin-mediated (mediated by spin-orbit coupling), de-excitation takes a longer duration, ranging from a few milliseconds to some minutes [5]. With phosphorescence, the emission intensity shows a gradual decrease over time, whereas with fluorescence, the emission intensity shows an exponential decrease over time. After the initial absorption of visible or UV light, the molecule goes into an excited electronic state, and then, after being subjected to collisions with surrounding molecules, it loses energy non-radiatively, thus going down to the lowest vibrational level of the excited molecular state [3]. Finally, the molecule undergoes a radiative transition from the lowest vibrational level of the excited molecular state to the ground state. Fluorescence is a singlet-singlet transition that follows Hund's rule and thus has a very short afterglow of the order of nanoseconds (S1–S0), but the long-lasting afterglow (phosphorescence) is caused by the spin-forbidden triplet-singlet (T1-S0) transition delayed because of intersystem crossing [6]. These transitions can be clearly understood using the Jablonski diagram shown in Fig. 1 [7]. Trapping of charge carriers in trap states leads to extending the duration of the afterglow in the case of phosphorescence to a couple of hours, preferably known as persistent luminescence (PerLum) [8]. This phenomenon can be understood as the continuous emission of radiation for extended durations after the removal of the excitation source in some luminescent materials called PerLum materials and sometimes afterglow [9,10]. In 1996, Matsuzawa et al. [8], reported a green-emitting SrAl2O4: Eu2+, Dy3+ phosphor with very bright and long-lasting phosphorescence that was over 10 times brighter than ZnS: Cu, Co. This aluminate phosphor exhibited properties of extreme brightness and an extended afterglow lasting for over 30 h before the emission intensity was observed to drop to 0.32 mcd/m2, which is the minimum emission intensity detectable by the naked human eye [8]. A variety of PerLum nanostructures are being fabricated and are frequently utilized in various fields, including bio-imaging, phototherapy, information storage, latent fingerprinting, and anti-counterfeiting, because of their distinctive optical qualities. With a higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and increased sensitivity, PerLum-based bio-imaging may allow for guided cancer therapy [[11], [12], [13]]. Hence, such nanostructures represent a novel class of nanomaterials with so many benefits in biomedicine [14]. By using such materials, the background fluorescence and deep probing issues caused by excitation energies like UV–Vis, which are frequently used in luminescent imaging of different organisms, are eliminated [15]. Technologies that can perform therapeutics and diagnostics, called theranostic devices, have been brought about using PerLum nanomaterials. Currently, studies on therapies involving photo-thermal therapy [16], photodynamic therapy [17], gene therapy, and sensing have been stimulated by the quest for non-invasive and customized procedures for treatment. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) relies on the production of reactive oxygen species and singlet oxygen ions, which makes it a fascinating field of study that can render the use of traditional systems useless, thus allowing the use of PerLum materials in this technique of therapy [17]. Because there is no need for in-situ stimulation, PerLum nanomaterials possess a significant potential for biological imaging due to their extremely long decay times and excellent SNR. PerLum materials have proven excellent frameworks for developing multifunctional devices in imaging-guided drug distribution and theranostics when functionalized appropriately [18]. PerLum materials also have a lot of possibilities in fields related to informational technologies like information storage, latent fingerprinting, and anti-counterfeiting because of the extended reading window offered by their characteristics [19].

Fig. 1.

Jablonski diagram explaining fluorescence (S1–S0 transition) and phosphorescence (T1-S0 transition) along with other undergoing transitions.

Matsuzawa et al. [8], marked the beginning of a renewed search for the underlying mechanism of PerLum, while until then, relatively little research was conducted on this subject. They described the mechanism of PerLum using the hole trapping and de-trapping model: when the Eu2+ ion is excited by an incident photon, a hole escapes to the valance band (VB), leaving behind an Eu+ ion, while the liberated hole is then captured by the co-doping Dy3+ ion, creating a Dy4+ ion. In the same year, Tanabe proposed a new model in which Eu3+ was created by leaving an electron in the conduction band (CB) while the Dy3+ ion captures the escaped electron through the CB and gets converted into Dy2+. This discovery prompted the search for more intense and long-lasting phosphors, and hence, 24 years after this breakthrough, many lanthanide-doped phosphors, with examples such as CaAl2O4: Eu2+, Nd3+ [20], Sr4Al14O25:Eu2+, Dy3+ [8] Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+, Dy3+ [21] and many others [22,23], have been fabricated to achieve this milestone. All such materials have found many uses in the current decade; for example, phosphors with blue and green emission colors have a vast range of civil applications and are readily available on the market [24]. In contrast to them, a very limited number of red and reddish-orange phosphors such as Y2O2S: Eu3+, Mg2+, Ti4+ [[25], [26], [27]], and (Ca1-xSrx)S: Eu2+ have gained access to the market. For some particular phosphors, the afterglow has also been found to last for a couple of hours, with examples of CaAl2O4: Eu2+, Nd3+, and SrAl2O4: Eu2+, Dy3+ phosphors [8,20]. PerLum has a large number of applications ranging from luminous watches and clocks to medical diagnostics, night-vision surveillance, displays, in-vivo bio-imaging, and thermal sensors [8,[28], [29], [30], [31], [32]]. Sherman et al., [33] reported in 2007 the use of PerLum nanostructures for real-time imaging in small animals for a duration longer than 1 h where, after in-vitro excitation, this phosphor emitted dark red NIR light and thus could be used as a promising contrast agent for a long time in-vivo optical imaging. Research on optical imaging, also known as fluorescence imaging, has rapidly grown in recent years with its application in brain imaging, sub-diffraction-limit imaging, molecular oncology, etc. [28,[34], [35], [36]].

The PerLum property of a material is due to the presence of lattice defects in the host material. Energy sources such as UV light, X-rays, and visible light are used to generate electron-hole pairs, which are then trapped in trap centers generated by lattice defects and impurities [37,38]. These electron-hole pairs then recombine because of thermal stimulation, due to which PerLum is observed. Co-dopants such as transition and lanthanide metal ions are introduced to enhance the traps within the material, which can increase the intensity of PerLum by several orders of magnitude [8,39,40]. In this review, we discuss different aspects of PerLum starting from various mechanisms that have been used to explain this phenomenon, such as the VB and CB models, the Hoogeustraten model, the oxygen vacancy model, etc., along with different fabrication techniques used to synthesize such phosphors with such properties such as solid-state reactions, hydrothermal reactions, combustion reactions, etc. These materials, as already mentioned, show the emission of photons long after the excitation process is stopped due to the trapping of charge carriers. Thus, their property of lasting in emission for extended periods of time has earned them the name "long-lasting phosphor (LLP)" [41]. Several reviews have been published focused on the phenomenon of PerLum but lacking in some aspects of synthesis techniques, properties, or applications [19,24,[42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52]]. Thus, to counter this problem and provide up-to-date details related to such materials, this review provides detailed information regarding a variety of synthesis techniques, their advantages and disadvantages, as well as focusing on the various hosts used and different activators employed in them. It also has a special section dedicated to the emission and excitation characteristics of such materials, along with the properties of traps, which possess primary importance in the afterglow properties of PerLum materials. Because of the very detailed nature of this review, it is expected that it will act as a compiled source of information for the research community. The application part of this review also shows the importance of this field of study and will be helpful in providing enough motivation for future researchers. In this review, we will also focus on some frequently used PerLum materials with different activators used to improve their emission characteristics, along with some important properties of such LLPs. Finally, in this review, our focus will be on the biomedical and security applications of PerLum materials, as shown in Fig. 2. Over time, many attempts have been made to explain the phenomenon of PerLum. Although it is still not known with perfect certainty how this phenomenon exactly comes to be, some of the most prominent and accurate mechanisms used to explain PerLum have been explained.

Fig. 2.

Illustration representing different applications related to long-lasting phosphors.

2. Mechanism of PerLum

The mechanism of PerLum remained unexplored until the 1990s [8,20], thus no information was available until then, although ZnS:Cu materials had been well-researched and were available in the market [53]. During the study of this phenomenon, it was observed that some particular phosphor materials exhibit thermally stimulated PerLum at room temperature (∼20–25 °C or 293–298 K) when subjected to extremely high temperatures during their fabrication [54,55] The mechanism behind this phenomenon is still a topic of discussion [9,[56], [57], [58], [59]]. Research has shown that there are two types of activation centers: traps and emission centers [60]. Rare-earth (RE3+) ions such as Dy3+, according to Holsa et al. [61], may only serve as trap centers to get trap distribution via charge compensation. It was also found that by using Sm3+ as a co-dopant in SrAl2O4: Eu afterglow exhibited by this aluminate phosphor was improved as the RE co-dopant was observed to change the energy of traps while affecting the deeper traps more prominently. In almost all cases, the emission centers and trap centers have been found to be within the forbidden energy gap while being located more near the bottom of the CB with electron traps or slightly above the VB with hole traps, with a respective energy difference of approximately 1 eV or slightly more depending on the trap depth [54,55,57].

The trapping mechanism can be physically understood as a four-step process, (a) excitation of PerLum phosphor: where it is externally excited by high energy radiation such as ultraviolet, visible, or near-infrared, the afterglow phosphors release charge carriers (electrons or holes, or even both) if the external radiation has an energy greater than a certain threshold value. (b) The second step involves the storage of charge carriers at trap sites, which are then captured by electron and hole traps through the CB and VB, respectively, instead of being radiatively relaxed. These electron and hole traps do not radiate energy instantaneously but store it for an extended time, earning them the name "optical battery" [49,62]. The storage capacity of trapping states depends on the carrier concentration and defects present in the luminescent material. (c) In the third step, carriers are released from the trapping states after excitation has taken place. Once the excitation is halted, the carriers can start releasing charge because of mechanical [63,64], optical, or, in most cases, thermal excitation [[65], [66], [67], [68], [69]]. This process is called as de-trapping process. (d) The last step involves the recombination of excited charge carriers, where these charge carriers, after de-excitation, move back to the emission center, giving rise to PerLum owing to the recombination process. The properties of the emission center determine the frequency of emitted photons, while the intensity and duration of PerLum at a specific temperature are mainly determined by trap density, trap depth, and concentration of doping For the trapping and detrapping processes in persistent phosphor, trap types and trap concentrations, along with their depths, must be taken into consideration as they have a significant effect on the afterglow properties of a different material [56,57,69,70]. (1) Trap type: with LLP, the traps are generated because of lattice defects that can be intrinsic or may arise because of any added impurity [5,37,71,72] or because of high-energy radiation that may fall on the phosphor material [59,73]. The nature of traps generated by the above approaches is very hard to characterize, and it is thus very hard to decide which defect is responsible for the trapping of carriers. (2) The concentration of trap states is the second important aspect that plays a very important role for PerLum, as the probability of the charge carrier getting captured increases as the trap density rises. Enhanced electron reservoir potential is a significant task to enhance the afterglow in PerLum materials [72,[74], [75], [76]]. (3) The depth of traps governs the release rate of carriers captured in traps and at the same time as affects the intensity of PerLum and the afterglow time of phosphors post-excitation. At room temperature, shallow traps are drained quickly, thus generating intense phosphorescence that is assisted by the quick-release rate of charge carriers. Charge carriers stored in deep traps with a slow rate of release are barely drained at room temperature. The slow-release rate of these deeply trapped carriers results in a reduced intensity of phosphorescence and a long afterglow time [75,77]. In the case of RE dopants, the trapping mechanism is related to electron delocalization and tunnelling, where an electron is excited to the CB before it is delocalized into a trap [78]. This can be brought about by employing one of the three ways. (a) The dopant can be ionized by single-photon excitation to the 5d level, which is located inside the CB and from which the electron is finally sent to the CB The luminescence is completely quenched if all the 5d levels are inside the CB [79] (b) The RE-ion can be thermally ionized with the electron being sent to the CB if it is excited to the 5d level, just below the CB [80]. (c) Multiple-step photoionization can be employed to delocalize an electron to a trap if the 5d level is far below the CB [81,82].

2.1. VB and CB model

Trapping charge carriers is essential for the long-lasting afterglow of phosphorescence, and it is the fundamental process of energy storage in PerLum [72,[83], [84], [85]]. The trapping of such charge carriers is brought about by their delocalization near VB or CB, and when the charge carriers are excited, they get captured by the trapping state to be released later, after excitation. When the charge carrier is trapped in the VB or CB, it is free to move until its recombination or until it gets trapped again. According to this model, the CB and VB take part in excitation, delocalization through electronic bands, and the capture and release of charge carriers [52]. A good amount of research has been done on thermoluminescence glow curves and trap depths that point toward its popularity [54,86,87]. The discovery of SrAl2O4:Eu2+, Dy3+ by Matsuzawa and others marked the beginning of research on the mechanism of PerLum, and afterward, many attempts were made to explain this phenomenon, for example, the hole/electron model, quantum tunneling model, intrinsic defect model (also known as the oxygen vacancy model), etc. Pieter Dorenbos put forward the electronic level schemes of VB and CB of the host, energy levels of the ground, and excited states of activation centers. Because of his theory, it became possible to explain the phenomenon of PerLum and the process of trapping [[88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94]].

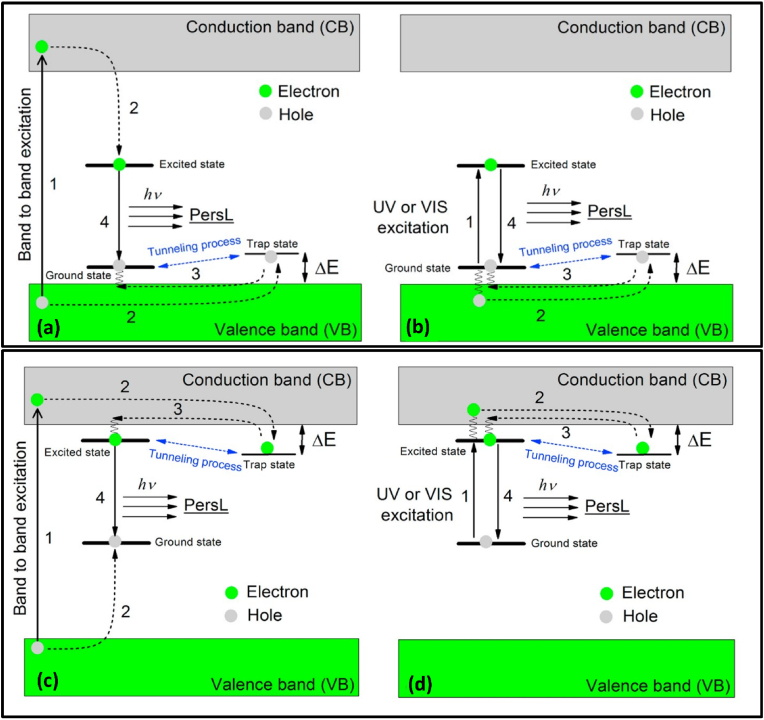

2.1.1. Matsuzawa model

Also known as the hole model this model considers holes as the main charge carriers. This model was put forth by Matsuzawa et al., in a very famous research paper published in 1996, where they announced the discovery of Eu2+-activated SrAl2O4 phosphor co-doped with Dy3+ [8]. They based their assumption on results published by Abbruscato in 1971 about the optical and electrical properties of SrAl2O4 doped with Eu2+ [95]; there, it was proposed that the charge transfer mechanism in this sample involves the generation of a hole in VB, which can then recombine instantly or be trapped owing to lattice defects. Abbruscato further proposed that, in the sample used, almost 99 % of the total intensity is because of activation by the conduction of holes, thus considering holes as the main charge carriers [95]. Matsuzawa and others predicted that upon UV exposure (365 nm), Eu2+ excites because of the 4f to 5d transition. They argued that excitation does not occur for host material, and thus a hole is generated at the 4f ground state level, which is then thermally excited to the VB, and hence Eu+ is produced from Eu2+. They said that the hole thus generated is captured by Dy3+, which leads to the formation of Dy4+, thus trapping the hole, which is then released back to the VB after thermal stimulation. From the VB, it then recombines with the Eu + ion to form Eu2+; thus, de-excitation occurs along with the emission photon [8]. Thus, we can say that in the case of a hole, model holes are released from hole trapping centers, which recombine with electrons at the luminescent center to generate LLP. The limitation of this model is that it explains the phenomenon of PerLum in the case of doping such as Eu2+-Dy3+ and Eu + -Dy4+ in SrAl2O4 [8,[96], [97], [98], [99]], but it does not explain PerLum for SrAl2O4 with doping other than Eu2+ and Dy3+. Fig. 3 [52] give a schematic representation of the hole model to explain the phenomenon of LLP. If the hole model and electron model are analyzed correctly, then we can see that these two are mirror images of one another. In the case of the hole model, after using high-energy excitation (Fig. 3a) or direct pumping with the help of UV or visible photons (Fig. 3b), the electron is shifted to the CB, and the hole stays in the VB as a free charge carrier. The trap state then captured this free hole, while the electron gets shifted from the CB to the triplet excited state between VB and the CB. The ground state, located just above the VB, can share a hole with the trap state via the tunnelling process. The release of the charge carrier from the hole trap state is mediated by thermal energy, which recombines in the ground state to produce LLP [52]. The Matsuzawa model became quite famous in a short time [96,[100], [101], [102], [103], [104]] and has been often used to explain the phenomenon of PerLum [[105], [106], [107]]. Many experiments [20,101,[108], [109], [110], [111]] were performed to confirm this model, but the results did not comply with it. Thus, to explain the LLP of materials that do not follow the hole model, electrons were the primary charge carriers, and hence a new model was put forward known as the electron model.

Fig. 3.

Illustration of the mechanism of PerLum based on trapping and de-trapping of a hole for (a) Band-to-band excitation with the help of high-energy photons (b) Pumping of emission ions with the help of low energy ultraviolet photons or visible photons. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [52], copyright 2019, Elsevier. (c) Illustration representing a mechanism of PerLum based on trapping and de-trapping of an electron in a trap state for (d) Band-to-band excitation with the help of high-energy photons (d) Pumping of emission ions by the help of low energy ultraviolet or visible light Reproduced with permission from Ref. [52], copyright 2019, Elsevier.

2.1.2. Aitasalo model

Also called the electron model, it considers the trapping of electrons as the reason for LLP. In the case of the hole model, which involves the trapping of holes that results in creating Eu+ and Dy4+ ions, which is not likely in the case of solids [9]. Thus, an alternate mechanism for PerLum was put forward by Aitasalo in 2003, which is based on the trapping of electrons rather than holes [9]. The electrons are directly excited from the VB to the trap level, and because of this process, a hole is also generated, which migrates to a calcium vacancy. It is important to mention that holes remain as free charge carriers in the VB, which explains the observations by Abbruscato and Matsuzawa used for their description of the PerLum of SrAl2O4:Eu2+, Dy3+ [20,95]. The electron is then transferred from the trap level to the oxygen vacancy with the help of thermal energy. Aitasalo argued that the oxidation of Dy3+ and reduction of Eu2+ (in the hole model) would generate ions that are chemically unstable [38]. The presence of cation and oxygen vacancies in calcium aluminates also provided support for the Aitasalo model [95,[97], [98], [99]]. As the CB is located high above the energy level of oxygen vacancies, a thermally assisted transfer of an electron from the VB to the CB occurs, which starts the recombination process.

According to this model, either the traps are directly supplied with the excitation energy or this energy is provided through the CB, and owing to this process, the electrons are trapped in the oxygen vacancy. As the energy level of the oxygen vacancy trap is located below the CB, it allows the thermally assisted transfer of electrons to the CB, thus starting the electron-hole recombination process. The recombination mediates the excitation of Eu2+ via non-radiative transition, and according to Aitasalo, this process uses close contact between defect centers such as oxygen and calcium vacancies and the luminescent centers. The energy produced by the recombination process excites the europium to the 5d level [112], which is followed by the recombination process and by PerLum [9]. Fig. 3 [52] show the schematic representation of the electron model used to explain the LLP. In Fig. 3c, a high-frequency energy source (a mercury UV lamp) has been used for excitation, while Fig. 3d explains the pumping of the emission center with the help of low-frequency photons, such as low-energy UV photons. By absorbing energy from high-frequency photons, electrons make a transition from VB to CB, leaving behind a hole, and thus both of them are free to move in their respective bands. Afterward, the electron is trapped by the trap center while the ground state of the emission center traps the hole, and thus the process of excitation is completed. After completion of the excitation process, the charge carrier, which has already been captured, is released with the help of thermal stimulation. The probability of the release of the charge carrier from the trap level is directly related to the energy gap between the bottom of the CB and the trap level denoted by E, as the release of the charge carrier from the trap level is only possible if energy gained due to thermal energy is equal to or greater than ‘E," satisfying the condition as shown in Fig. 4a. Because of the recombination of an electron released from the trap site and the hole present in the VB, a PerLum is generated. If the excited electron is trapped due to intrinsic defects that are very shallow, then it can be released within very little time, which gives rise to an afterglow between μs or ms [[113], [114], [115], [116], [117]]. Because of thermal stimulation, the probability of release of the charge carrier from the trap site per unit of time is given by the Arrhenius equation:

| (1) |

Fig. 4.

(a) Schematic diagram representing the process of thermal assisted release of trapped charge Carriers divided into 4 steps (1) excitation by a suitable wavelength (2) trapping of an electron in trap level and shifting of a hole to recombination center (3) release of charge carrier to CB triggered by thermal energy and (4) recombination of electron and hole at recombination center which results in the production of luminescence [55]. (b) Schematic representation of the mechanism of PerLum as proposed by Dorenbos to explain the LLP in the case of aluminates and silicates.

The term ‘s’ represents frequency factor or attempt to escape factor which is temperature independent with the value ranging from 1012 – 1014 s−1.

In the year 1996, Tanabe also proposed that Eu3+ is created post-excitation when an electron shifts to the CB, which is then captured by Dy3+ to form Dy2+. This theory got strong support from the fact that Eu3+ was observed in afterglow materials after the analysis of X-ray absorption near the edge structure (XANES). The co-dopant Dy3+ ion in the electron model is considered to be contributing to defects and also increasing the oxygen vacancy in SrAl2O4. The increase in the number of lattice defects is because trivalent lanthanide ions occupy the alkaline earth sites, which are divalent, which leads to defect creation because of the charge compensation process [38]. The addition of Sm3+ to increase PerLum has the same explanation of charge compensation as it is reduced to Sm2+ during preparation, thus removing hole vacancies, such as cation vacancies. Holsa et al. [9], also proposed that Eu+ and Dy4+ were unstable in aluminate or silicate compounds, thus supporting the hole model. They also argued that by adding a RE dopant, it is possible to modulate the trap state with the help of charge compensation. They found that the addition of Sm3+ ions to SrAl2O4:Eu proved to be an important factor affecting the duration of afterglow in this phosphor as the Sm3+ ion gets reduced to Sm2+ easily in the N2–H2 atmosphere, which leads to a decrease in the concentration of traps. Based on this phenomenon, reasonable explanations were proposed for the mechanism of LLP for CaAl2O4: Eu co-doped with Nd, and for ZrO2: Ti. This group employed techniques such as EPR, XPS, and XANES, which proved oxidation of Eu2+ to Eu3+ during the process of excitation, while during experimentation no change was observed in the valency of co-dopants. It was observed that when a host was doped with two dopants instead of one, they showed a strong afterglow that lasted for a longer duration. The reason for this stronger and longer afterglow is that the co-dopant helps to regulate trap parameters [118]. The mechanism of PerLum proposed by Matsuzawa was not accepted by Clabau et al. [119], as they observed a decrease in the concentration of Eu2+ ions during excitation in EPR measurements, but as soon as excitation ended, their concentration was seen to increase, which continued until luminescence ended. Thus, they proposed that Eu2+ helps in the process of trapping and de-trapping, which is opposite to the idea of energy transfer to Eu2+ after a charge carrier is trapped.

2.1.3. Band engineering model (dorenbos model)

The electron model was accepted by Dorenbos and coworkers, but they argued that the electron model presented by Aitasalo considers that after excitation, the charge carrier remains in the ground state of Eu2+, which is a wrong assumption [120]. Because, in the case of lanthanides, energy levels are localized, in contrast to the Bloch states of VB and CB which are delocalized, thereby Dorenbos and others proposed a different mechanism of LLP in 2005 [90]. They expected electrons to be excited by Eu2+ ions in the VB and thus convert them into Eu3+ ions. As the 5d energy state of the Eu ion is located very near to CB, excited electrons can easily shift to CB, after which they combine with a trivalent RE-ion to give rise to a divalent RE-ion, as shown in Fig. 4b [19]. This model of PerLum also faced the limitation of not being able to explain LLP with SrAl2O4:Eu2+. This group proposed several approaches to calculate energy levels for different phosphors to explain their PerLum, for which it is very essential to contemplate some properties like the location of energy levels of RE2+ and RE3+-ions, the energy band gap of the host material used, and the calculation of the position of the trap level regarding the bottom of the CB of the host material. The location of trap states can be estimated with the help of thermoluminescence spectroscopy, and the energy band gap could be calculated using diffuse reflectance spectra, but the tricky part is calculating the location of the energy levels of RE-ions, i.e., RE2+ and RE3+. By taking the example of CdSiO3 doped with Tb3+, Holsa, and others predicted a method for calculating the ground state excitation energies of RE2+ and RE3+-ions [[121], [122], [123]]. They proposed that according to the previously discussed mechanisms, the energy at ground level for RE3+-ions has been independent of the host, so once the ground state energy of any RE3+-ion has been calculated, that data can be used to calculate the ground-level energy of any other RE-ion with the help of Dorenbos's model of PerLum. They also proposed that it is very important to consider the intensity of the transition to generating accurate data to explain the reason behind LLP. Based on this theory, the ground state energy levels for Sr3MgSi2O8 were calculated, and the best possible RE-ions to act as emission centers were estimated to be Eu2+, Ce3+, Tb3+, and Pr3+. These ions produce strong emissions and also possess a very low tendency for cross-relaxation and multi-photon de-excitation. One of the main requirements of LLP is that we should be able to excite a nanophosphor with a photon from the visible range, which is present in normal daylight, or with the help of UV light possessing the lowest possible energy. Now, as far as Eu2+, Ce3+, Tb3+, and Pr3+ are considered, they possess the lowest 5d energy, so they can be easily excited with the help of low-energy photons such as low-energy UV or even blue light with Eu2+. By using such atoms as dopants, overlap between the 5d excited level and the CB can also be ensured, so that transferring an electron to the trap level becomes efficient and easy [[124], [125], [126]]. The glow curves of YPO4:Ce3+, RE3+, and YPO4: Pr3+, RE3+ were studied by Bos et al. [127], and Lecointre et al., [128], respectively. The RE-used in the former case were Nd, Sm, Dy, Ho, Er, and Tm, and in the latter case, the RE-ions used were Nd, Dy, Ho, and Er. It was observed that the thermoluminescence peaks obtained in both cases matched each other perfectly, and the values of electron activation energy have been observed to be the same for both of these phosphors. This observation predicted that the addition of co-dopant plays a role in the trapping process when, typically, it is not its property.

2.1.4. Clabau model

Clabau and others also analyzed the already proposed mechanisms of PerLum and concluded that they could not explain this phenomenon with perfect accuracy and needed a modification. They also didn't accept the hole model proposed by Matsuzawa for the same reasons as those put forward by Dorenbos. They further added that EPR measurements indicate that there is a fall in the concentration of Eu2+ during the process of excitation and then a rise in its concentration after the source of excitation is switched off, which keeps on increasing until the afterglow continues. Thus, they concluded that this fall and rise in the concentration of Eu2+ must be because this ion takes part in the trapping process, which contradicts the process of energy transfer to Eu2+ after trapping as proposed by Aitasalo [119,129,130]. The model of PerLum proposed by Clabau et al. [119], as shown in Fig. 5 [57], was almost the same as the one proposed by Dorenbos, with some important modifications, such as the fact that in this model, Clabau et al. [119], considered that there was no migration of electrons via the CB but that transferring electrons was rather a direct process between the trap state and a luminescent center. Shifting of electrons between the trap state and luminescent center requires proximity of lattice defects with Eu ions, as shown by the results of photoconductivity measurements of strontium aluminate doped with Eu2+ and Dy3+ and excited with the help of UV photons. During this measurement, it was observed that up to a temperature of 250 K, the value of photoconductivity increases, which attains its peak value at a temperature of 300 K. Getting the peak value of photocurrent means that there are no more free charge carriers that could be released at this temperature, but thermoluminescence measurements show that at 300 K the process of de-trapping is going on, which led Clabau and others to conclude that interaction between the trap state and luminescent center does not take place via CB. Another important point that Clabau and others noticed was that by comparing the glow curves of undoped SrAl2O4 and SrAl2O4: Eu2+ co-doped with Dy3+, the peaks of these two glow curves were found to vary in size and location, but have a similar shape, which led them to conclude that the chemical nature of the trap does not vary with the addition of a co-dopant. Thus, they concluded that oxygen vacancies act as traps in strontium aluminate doped with Eu2+ and co-doped with RE3+ [129]. Using lanthanide co-dopants was found to assist in stabilizing the oxygen vacancies because of their lower ionization potential, and a lower value of ionization energy will attract oxygen vacancies more strongly, thus increasing the depth of traps [130]. Such results imply that if the RE co-dopant ion has a higher ionization potential, then the time of afterglow will decrease [119].

Fig. 5.

Schematic diagram explaining the phenomenon of PerLum as proposed by Clabau and coworkers for strontium aluminate doped with Eu2+ and Dy3+.

2.2. Hoogeustraten model

This model is also known as the quantum tunnelling model, which refers to a process where a particle can overcome a barrier that is not possible for it to do classically. This process takes place near the excited energy levels of activator ions and trap states. With the aid of this model, PerLum can be explained because of deep traps, as this model does not require any physical proximity of trap levels with VB or CB. This model was proposed by Hoogeustraten and others [131] in 1958. After this Tanabe and coworkers [132] also proposed a similar model to explain LLP for strontium aluminate doped with Eu2+ and Dy3+. By proceeding with the measurement of photocurrent, Tanabe and others found that the maximum number of 5d energy levels of the Eu2+ ion, which replaces Sr in the host, has a lower crystal field residing inside the CB. Based on this finding, they concluded that the trapping and de-trapping processes occur via the process of quantum tunnelling, which is in contrast with the idea that trapping and de-trapping occur via VB and CB. In the year 2012, Pan et al. [133], studied zinc gallogermanate phosphors with strong emission in the wavelength range of 650 nm–1000 nm and a very long afterglow of approximately 360 h.

Variations in the energy used in activation proved that the threshold ionization energy level in Zn3Ga2Ge2O10 lies very near to CB. These findings were very similar to the VB-CB model as represented in processes 2 and 3 of Fig. 6a [19] and process 2 and 4 in Fig. 6b [19]. During their study, they found that visible light can also produce LLP with a very weak intensity but an extra-long afterglow, because of which they proposed that another mechanism of LLP was at play in this nanophosphor, which involves the trapping and de-trapping of electrons. This mechanism of PerLum is called the quantum tunnelling model and is explained by processes 4, 6, and 7 of Fig. 6a [19] and by process 5 of Fig. 6b [19]. With the help of visible light excitation, electrons present in the ground state of the Cr3+ ion shift to deep traps with an energy lower than the threshold ionization energy. Trap states are further filled by the tunnelling process from Cr3+ energy levels whose energy matches that of trap states. Because of the reverse tunnelling process, PerLum with a weak and super-long afterglow is produced. The near-IR PerLum of LiGa5O8 also supported all these proposed phenomena doped with Cr3+ with an afterglow of 1000 h [134].

Fig. 6.

(a) schematic diagram representing the mechanism of near IR Per Lum. In the above figure, straight lines with arrowheads represent optical transition while curved lines with arrowheads represent the process of electron transfer. (b) figure representing the mechanism of near IR Per Lum and photo stimulated Per Lum in the near IR range.

2.3. Oxygen vacancy model

Yang et al. [19], proposed this mechanism of PerLum based on the study of luminescence triggered by photons from fluoro-aluminate glasses doped with Eu2+ [135], alkali-doped silicate and borate glasses doped with Ce3+ [136], strontium aluminosilicate glasses doped with Eu2+ [137], and glasses doped with gold nanoparticles [138]. By studying EPR spectra, they explained the trapping and de-trapping of charge carriers based on the model of PerLum called the oxygen vacancy model. Oxygen vacancies are stable and can explain PerLum in oxide-based hosts. In the case of the oxygen vacancy model, such vacancies act as traps for electrons and thus lead to an extended afterglow. One of the main advantages of this model of PerLum is the confirmation of such trap types instead of the theoretical approach of the VB/CB model and the quantum tunnelling model. Oxygen vacancies have been mentioned as one of the main reasons for PerLum, as Aitasalo and others considered them very important traps in their model to explain PerLum [9] in the case of strontium aluminate doped with Eu2+ and Dy3+, and Clabau and others also mentioned them as highly efficient traps for electrons [119]. As mentioned earlier, by comparing the glow curves of SrAl2O4 doped with Eu2+ and SrAl2O4 doped with Eu2+ and co-doped with Dy3+, it was found that the thermoluminescence peaks of these two phosphors varied in size and position but had similar shapes. From this study, they proposed that the use of co-dopants does not affect the chemical nature of traps, and thus only oxygen vacancies assist in the trapping and de-trapping of electrons for LLP. Lim et al. [139], studied spinal phosphors doped with Ti and concluded that red emission in the wavelength range of 620 nm is due to Mg2+ and O2− vacancies. They based this finding on the fact that in the case of pure spinal intrinsic defects known as Schottky defects, such as Mg2+ and O2− vacancies, they were present in abundance and had also appeared in pairs, thus supporting the oxygen vacancy model.

It can be said that for the generation of efficient luminescence along with extended afterglow, it is very essential to choose a suitable host along with an appropriate dopant and co-dopant. Over time, many hosts have been synthesized and afterward doped with different activators, mostly RE-ions, along with a few transition and main group elements as well. The quest to find more and more efficient PerLum nanostructures with improved luminescent and structural properties along with extended afterglow is still going on, with quite a few researchers shifting their field of study in this direction. One of the most prominent reasons behind this is the vast field of applications for such materials to be used in fields like bio-imaging, therapy, sensing, security, glow-in-the-dark signs, toys, etc.

3. Components of persistent luminescence nanophosphors

The selection of a suitable host and activator is very important for a phosphor to display the phenomenon of PerLum. The host acts as a trap carrier during activating LLP, and because of the different properties of traps, a variety of hosts may possess varying storage abilities for charge carriers. A host can possess two types of defects, and both of them aid in producing traps for charge carriers. These defects include intrinsic thermal defects, which are present in the lattice structure of the host, and extrinsic defects, which are introduced via different phenomena, such as the addition of a dopant, etc., [140]. Some particular characteristics of a PerLum nanophosphor host and dopant play a very important role because the process of luminescence is based on energy absorbed by the host lattice or dopant ions, the outcome of which is absorption and consequent emission of energy [141]. Luminescence involves excitation with the help of a suitable excitation source and the emission of visible light, which is commonly caused by an impurity ion, also called an activator ion. In some particular cases, if emission from an activator ion is too weak, a co-dopant is added to the host material. Such an added impurity, which may act as a sensitizer, possesses the property of strong energy absorption, and this absorbed energy is quickly transferred to the activator site thus, enhancing luminescence properties. Hence, for efficient luminescence and color tunability, the choice of a suitable host and dopant is very important [142,143]. In this part of the review, we will discuss the classification of host materials along with the variety of hosts used to generate PerLum.

3.1. Hosts

As already discussed, the choice of a suitable host and activator is very important for extended afterglow and strong emission. Trapping charge carriers leads to the phenomenon of PerLum, so the availability of trap states is imperative. In a PerLum nanomaterial, traps are introduced via defects that have already been mentioned as intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic defects can be of many types, such as cation vacancies, anion vacancies, thermal defects, and interstitial ions. Most of these defects are brought about by high-temperature treatment, so the volatilization temperature of the metals and metal oxides must be taken into consideration. In the case of oxides, the formation of traps has been observed in hosts whose melting point is low and volatility temperature is high, for example, ZnO, SrO, WO3, CaO, P2O5, and GeO2, but the formation of traps has also been seen with Al2O3, SnO2, Ga2O3, etc., which possess a low volatility temperature that allows faster volatilization of metal ions. Apart from the fabrication technique used and the condition of synthesis, the crystal structure of the host and the location of the activator in this crystal structure also play a very crucial role in generating afterglow. For example, with ZnGa2O4, which possesses an AB2O4-type spinal structure where A represents zinc ions and B represents gallium ions occupying tetrahedral and octahedral sites, respectively, a very peculiar property is observed in it, i.e., this spinal structure shows slight inversion characteristics in which a few zinc and gallium ions exchange their positions, thus giving rise to a crystal defect known as an anti-site defect. It has been observed that this compound displays an inversion of approximately 3 %, so almost 3 % of zinc and gallium ions exchange positions. It has also been observed that when a gallium ion takes the place of a zinc ion, it generates a defect with a positive charge, whereas when zinc replaces a gallium ion, a negatively charged defect is generated [144,145]. Li and others [146] took advantage of the inverted spinal structure property by synthesizing Zn2SnO4 and doping it with Cr, where they employed the easy replacement of Zn2+ and Sn4+ by Cr3+ ions, which gives rise to distorted octahedral-type coordination and unequal substitution. In the comparison of normal structure, the inverse spinal structure provides a different arrangement of cations, where the structure of ZnGa2O4 involves Sn cations and 50 % of zinc cations are located at octahedral sites while the other 50 % of Zn cations occupy tetrahedral sites. Because of this type of structure, despite having zinc vacancies and interstitials, it also contains some anti-site defects, which are generated when zinc and tin ions replace their positions, and hence it could be predicted that some unequal substitutional defects would be formed [147]. Apart from these intrinsic defects, some extrinsic defects can also be generated by introducing dopant ions. Research in PerLum has shown that doping can vary the properties of traps such as distribution and density along with increasing depth and concentration of traps, e.g., with SrAl2O4 doped with Eu2+, the duration of the afterglow is very short and emission intensity is also weak, but with the use of co-dopant Dy3+, the afterglow time increases while increasing the intensity of emission at the same time. Using co-dopant does indeed allow the generation of defects in the lattice structure, but it is also closely related to the properties of dopant, viz., atomic radius, doping concentration, valance state, etc. Gedekar et al. [148], studied the luminescence of Eu2+-doped BaAl2O4 and, after studying the PL spectra of this nanophosphor, they observed that the excitation spectrum featured three peaks at 270, 328, and 397 nm, as shown in Fig. 7 (I) [148]. It was observed that the 328 nm peak was five times more intense than that of 270 nm peak. This excitation spectrum was attributed to the 4f7 to 4f65d transition of the activator ion. They observed that the emission spectrum for this nanophosphor does not seem to depend on the choice of wavelength used for excitation and features two distinct peaks at 485 and 433 nm. Maximum emission was seen to be centered at 485 nm, which was attributed to the 4f65d to 4f7 transition emitting blue light. Lephoto et al. [149], also synthesized BaAl2O4:Eu2+ via the combustion method and studied the effect of using a co-dopant among the lanthanide series. They used photons in the wavelength range of 325 nm for excitation, and PL studies of this nanophosphor showed maximum intensity for co-doping of Eu3+ while the least intensity was observed for Ce3+ co-doping, as shown in Fig. 7 (II) [149]. They also observed that only Nd3+ and Dy3+ showed an afterglow of longer duration, and the same was also observed by Katsumata et al. [150], who used co-doping of Nd3+ and Dy3+ in MAl2O4:Eu2+.

Fig. 7.

(I) Photoluminescence spectra of BaAl2O4 doped with Eu2+ (a) Excitation spectrum. (b) Emission spectrum showing the effect of Eu2+ activator ion. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [148], copyright 2017, Springer Nature (II) Emission spectrum of BaAl2O4:Eu2+ co-doped with different lanthanide ions to observe the effect of RE co-doping on luminescence spectrum. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [149], Copyright 2012, Elsevier.

It has been seen that in most PerLum nanomaterials, intrinsic defects induced by thermal energy along with extrinsic defects collectively affect the duration and intensity of the afterglow. The optical properties of ZrO2:Ti3+ and ZrO2:Ti3+ co-doped with Lu3+ were studied by Holsa et al. [151], and they found that Ti3+ acted as the center of luminescence while introducing Lu3+ improved the afterglow time. They explained this phenomenon via the mechanism of the generation of oxygen vacancies, where they stated that the Lu3+-ion settles in the location of Zr4+ in ZrO2: Ti3+, Lu3+, which results in the generation of oxygen vacancies via the phenomenon of charge compensation. These oxygen vacancies act as a reason for a change in trap distribution for the host, thus acting as traps for electrons and holes in the lattice structure. Such types of extrinsic and intrinsic thermal defects were also observed in the lattice structure of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+ and co-doped with RE3+ [152]. It has been observed that in this phosphor, intrinsic defects involve oxygen vacancies, cation vacancies, as well as interstitial ions. The existence of cation vacancies is due to the replacement of RE3+ by a metal ion with a charge of +2. In many other PerLum nanomaterials, such as CdSiO3, etc., almost the same distribution of traps has been found while they are undoped or when they are doped with RE3+ ions. The reason behind such trap distribution is considered to be oxygen and cadmium vacancies, which result from CdO evaporation. Charge compensation defects result from the replacement of Cd2+ by RE-ions, which give rise to interstitial oxide ions and cadmium vacancies [121].

3.2. Activators

The phenomenon of PerLum also largely depends on the properties of emitter centers, as after absorbing energy, they should be able to emit visible radiation, which generates an emission spectrum. In nanophosphors, there are many ions used as activators, but for PerLum examples of ions used as activators, there are very few, which include some RE-ions (Ce3+, Sm3+, Eu2+, Eu3+, Tb3+, Dy3+, Yb2+, Yb3+, etc.), transition metal ions such as Cr3+, Mn4+, Mn2+, Ti4+, etc., and some elements of main groups such as Bi3+, etc. In this review, we will discuss different aspects of PerLum related to RE-ions, transition metal ions, and some elements in the main group.

3.2.1. Rare earths as activators

RE-doped PerLum has received a lot of attention over the past few years and has been extensively used in luminescent materials. One of the main advantages of the use of RE-ions as activators is that they allow excitation by almost any kind of energy source. In most cases, the efficiency of luminescence decreases sharply in the presence of lattice defects, but with PerLum nanomaterials, defects allow for an increased duration of afterglow as the defects act as traps for electrons and holes [9]. Starting in the mid-1990s, a completely different type of PerLum nanophosphors with RE-ion doping were synthesized and studied [153], such as nanophosphors having a general formula of MAl2O4 doped with Eu2+ (M = Ca, Sr) [154,155]. Apart from these nanophosphors, some other LLPs with more complex lattice structures and RE-doping were also studied [[156], [157], [158]].

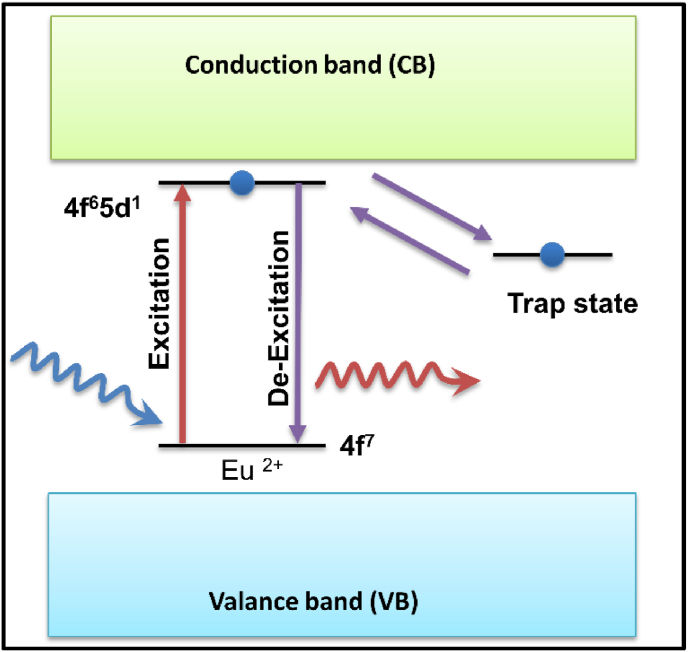

One of the most famous dopants used for PerLum is Eu2+, which is used as an activator ion and whose emission color varies depending on the electrostatic field of surrounding ions (also called the crystal field effect). With phosphors such as SrAl2O4:Eu2+ co-doped with Dy3+ [159], Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+ co-doped with Dy3+ [160] and CaAl2O4:Eu2+ co-doped with Nd3+ [20] etc., blue emission is obtained once they are excited with a suitable energy source. Some other nanophosphors display green emission once excited with photons of suitable frequency, for example, Ba2MgSi2O7:Eu2+ co-doped with Tm3+ [161], SrAl2O4:Eu2+ co-doped with Dy3+ [20], etc. For emission to appear in the colors yellow, red, or orange, it is very important that the strength of the crystal field be such that it can lower the lowest energy state of the 4d65 d1 configuration. Some of the potential candidates that show this kind of emission are Sr3SiO5:Eu2+ co-doped with Lu3+ [162,163], Sr2Al2Cl2O5:Eu2+ co-doped with Tm3+ [164], Ca2BClO3:Eu2+ co-doped with Dy3+ [7], etc. PerLum of oxides is triggered with the help of UV light, while Eu2+-doped silicates and nitrides show emission falling in the wavelength region of red light. RE-doped nanophosphors have also been observed to emit NIR PerLum, so they can be used for biological applications. For example, the red light-emitting phosphor BaMg2Al2N4:Eu2+ co-doped with Tm3+ synthesized by Ueda et al., [165] emits NIR PerLum. This luminescent material could be charged using red light and could be used for imaging biological subjects in the first biological window. Currently, research in the field of PerLum is mainly focused on aluminates and silicates, as it has been observed that the afterglow emission from such nanophosphors is strong and the afterglow time is also sufficiently long [166]. One other very important ion used as an afterglow activator is Ce3+, which possesses an electronic configuration of 4f1. Because of this property, it can display broad emission, as the 4f1 configuration ensures a strong crystal field, whose strength depends on the transition energy of the 5d-4f transition [167]. Some examples of PerLum nanophosphors with an afterglow of more than 3 h and blue-green emission are Ca2Al2SiO7 doped with Ce3+ [168], Lu2SiO5:Ce3+ [169], SrAl2O4:Ce3+ [170,171], CaAl4O7: Ce3+ [56,57], etc. Two important characteristics of nanophosphors doped with Ce3+ are that the most commonly used hosts from aluminate family and that the emission for such PerLum nanomaterials lies in the wavelength range of the blue region. Some examples of PerLum nanomaterials that display afterglow in the wavelength range of green and yellow are: Y3Sc2Ga3O12 doped with Ce3+ with bluish green emission [172,173], Lu3Al2Ga3O12:Ce3+ with bluish green emission [151], Y3Al2Ga3O12:Ce3+ with green emission [174] etc. In most nanophosphor wavelengths of photons used for excitation lie in the range of blue light, while UV light is also being used for most of the PerLum nanomaterials for exciting them to a higher energy state.

Using Eu3+ as an activator has also been studied in good detail because of its property of efficient red emission, which is due to a large number of transitions from the 5D0 excited state to the 7FJ (J = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4) energy levels of the 4f6 configuration, with the wavelength of all these transitions falling in the red-orange region of the electromagnetic spectrum. A large number of oxy-sulfide-based nanophosphors doped with Eu3+ have been studied, such as Gd2O2S: Eu2+ co-doped with Mg2+ and Ti4+ [175], Y2O2:Eu2+ co-doped with M2+ and Ti2+, where M denotes metals from the group of alkaline earth metals such as Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba, and Y2O2S: Eu3+ co-doped with Zn2+ and Ti4+ [176,177]. In case of a host such as Y2O2S and Gd2O2S, Eu3+ used as an activator replaces Y3+ and Gd3+ and thus acts as a center of emission. Co-dopants such as Mg2+ and Ti4+ used in these phosphors also replace the same sites in their respective hosts and then act as sensitizers by absorbing energy and then transferring that energy to the activator or emission center. Apart from oxy-sulphides, a large number of oxides doped with Eu3+ have been reported to show the properties of PerLum, viz., SrMg2(PO4)2: Eu3+ co-doped with Zr4+ [178], Lu2O3 doped with Eu3+ [179], Ba3Gd8Zn4O21 doped with Eu3+ [180,181], etc. Sm3+ is also a widely used activator because of its strong red emission, which is attributed to the transitions between the ground and excited electronic states of this activator. Because of its property of intense red emission, Sm3+ has been used as an activator in a large number of LLPs that involve oxides, oxy-sulphides, and fluorides such as La2Zr2O7:Sm3+ and co-doped with Ti3+ [182], CaO doped with Sm3+ [183], La2O2S doped with Sm3+ [184], KY3F10 doped with Sm3+ [185], etc., were studied in detail. To study the afterglow properties of Sm3+, a large number of stannate-based compounds have been doped with this activator, viz., Ca2SnO4 [186], Sr2SnO4 [187], CaSnSiO5 [188] etc. For the nanophosphor Sr3Sn2O4 doped with Sm3+, excitation due to ultraviolet light results in strong emission of reddish-orange light attributed to 4G5/2 to 6HJ (where J take values 5/2, 7/2, and 9/2). The afterglow from such transitions has been observed to be very bright and visible to the naked eye for an hour [189]. Similarly, UV (254 nm) excitation of Na2CaSn2Ge3O12 doped with Sm3+ results in the emission of photons in the red wavelength range. Afterglow of this emission has been observed to last for 4.8 h, ascribed to a transition from its ground state, i.e., 4G5/2 to its lower energy states [190]. Another activator that displays red emission with chromaticity coordinates of (0.68, 0.31) is Pr3+, with emission attributed to transitions of 1D2 to 3H4, 3P0 to 3H6 and 3P0 to 3F2. For the first time, a red afterglow among Pr3+-doped compounds was found in perovskite-type oxides with a chemical formula of ABO3, such as CaTiO3 [191] NaNbO3 [192] and SrZrO3 [193] etc. After this, many other PerLum nanomaterials were reported which were observed to emit photons in the wavelength range of red region, viz., CdGeO3 doped with Pr3+ [194], Y3Al5O12 doped with Pr3+ [195], ZnTa2O6 doped with Pr3+ [196], La2Ti2O7 doped with Pr3+ [182], Ca2SnO4:Pr3+ [197], etc. Strong emission in the wavelength range of green has been obtained by the use of Tb3+ as an activator, attributed to transitions from 5D4 to 7FJ (J takes values of 6, 5, 4, 3). This green emission resulted from the radiative relaxation of the excited Tb3+ ion, corresponding to transitions from the 5D4 state to the 7FJ state. The longer afterglow is because of the process of cross-relaxation between two adjacent Tb ions, which leads to the weakening of the 5D3 to 7FJ transition, thus leading to the strengthening of the 5D4 to 7FJ transition [122]. Various reported nanophosphors with doping of Tb3+ possessing afterglow emission falling in the wavelength region of green are: Lu2O3 doped with Tb3+ [198], CaSnSiO5 doped with Tb3+ [188], CaZnGe2O6 doped with Tb3+ [56], Y2O2S: Tb3+ co-doped with Sr2+, Zr4+ [199] etc. Another activator ion generally incorporated in luminescent materials for white emission is Dy3+. Its white emission is caused by transitions such as 4F9/2 to 6H15/2 and 4F9/2 to 6H13/2 of the Dy3+ ion. The main procedure for generating white light is by mixing red, green, and blue emission, also called RGB emission, but this method suffers some disadvantages, such as the fact that it does not attain optimized CRI and CCT values, and another limitation is that it is very difficult to achieve the same duration of afterglow for red, green, and blue PerLum phosphors. This activator ion possesses a huge potential for the application of white light afterglow emission. Two important emissions generated by Dy3+ ions lie in the wavelength range of 470–500 nm (4F9/2 to 6H15/2), corresponds to blue emission, and 570–600 nm (4F9/2 to 6H13/2), corresponds to yellow emission. Some other examples of PerLum nanomaterials with white afterglow resulting from doping with Dy3+ are Ca3SnSi2O9 [200] Sr2Al2SiO7 [201], CdSiO3 [121], CaMgSi2O6 [202], CaSnSiO5 [188], Sr2SiO4 [203,204] etc.

Many other RE-ions used as activators for PerLum are Tm3+, Yb2+, and Yb3+, which have been reported rarely as the centers of luminescence because of the difficulty in finding a suitable host. Su et al. [205], used Tm3+ as a dopant for Zn2P2O7 and observed a blue afterglow owing to transitions of the Tm ion, viz., 1D2 to 3H6, 1D2 to 3H4, and 1G4 to 3H6. They used UV light for excitation, and after it was switched, strong blue emission was obtained with an afterglow duration of over 1 h before its intensity decreased to less than 0.32 mcdm−2. Green afterglow has been observed with Sr4Al14O25: Yb2+ co-doped with Dy3+ [206] and SrAlxO(1+1.5x): Yb3+ (x = 3,4,5) [206]. In the case of SrS doped with Yb2+, the afterglow obtained was found to be in the wavelength range of red, and was attributed to the 4f135d1 - 4f14 transition of the Yb3+ ion [207]. Caratto et al. [208], synthesized a series of hexagonal II-type Gd oxycarbonate PerLum nanophosphors (Gd2-xYbxO2CO3), doped them with Yb3+, and got an afterglow of approximately 144 h. They observed that these nanophosphors showed a very strong emission in the near IR region, and one major advantage of this nanophosphor was that its luminescence was observed to be independent of temperature, thus making this material a potential candidate to be used as an optical bio-label for bio-imaging.

3.2.2. Transition and main group metal ions as activators

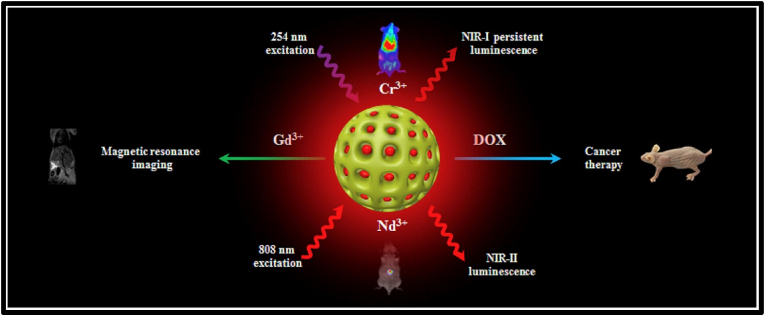

One of the most important transition metal ions used as an activator due to the 3 d5 electronic configuration, which features a broad emission starting from blue-green photons corresponding to 490 nm to the far-red wavelength corresponding to 750 nm, is Mn2+. This type of emission is attributed to the 3d–3d inter-atomic transition that is parity forbidden, going from the lowest excited state 4T1 to 6A1 ground state. The coordination number is also very important for the type of afterglow obtained in Mn2+-activated PerLum nanophosphors, as with Mn2+, tetrahedral coordination gives rise to green emission, while octahedral coordination results in orange to red emission [209,210]. For example, the afterglow of β-Zn3 (PO4) 2: Mn2+ co-doped with Ga3+ and γ-Zn3(PO4)2: Mn2+ co-doped with Ga3+ was observed to be very distinct, with the former displaying a strong red afterglow and the latter displaying a green and red afterglow. This property was attributed to two different coordination numbers, with β-Zn3(PO4)2:Mn2+, Ga3+ having a coordination number of 6 and γ-Zn3(PO4)2:Mn2+, Ga3+ possessing a coordination number of 4 as well as 6 [211]. Because of similar reasons, Mn2+-doped Zn2GeO4 displays a green afterglow [212], while Mn2+-doped compounds such as Li2ZnGeO4 [213], CdSiO3 [214], CaZnGe2O6 [215], MgGeO3 [216] display an afterglow emission in the orange-red region. Phosphorescence by Mn2+-activated compounds also includes Mn2+-doped glasses and nitrides, e.g., AlN doped with Mn2+ [217]. Mn4+ is also a very important activator ion because of its 3 d3 electronic configuration, which ensures the stabilized emission of near-IR photons in the wavelength range of 600–800 nm in a variety of hosts. This emission has been observed to depend on the strength of the crystal field environment of the host used. Li et al. [218], synthesized Mn4+-doped LLPs, viz., MAlO3, where M denotes La and Gd, and obtained a peak emission at 730 nm with an afterglow of over 20 h. Pan et al. [219], synthesized a PerLum nanophosphor Zn1+xGa2-2xSnxO4:Cr3+ with emission in the near IR range that could be activated using low energy photons and recharged with an efficiency 400 times as compared with ZnGa2O4 doped with Cr3+ (used as reference material). They observed that by tuning the field strength of the crystal and the energy of the band gap with the help of cation occupancy, red-shifted PerLum could be obtained. This shift in luminescence properties made it a potential candidate for deep tissue imaging with better efficiency.

Among transition metals, another very important ion used as an activator is Cr3+ because of its 3 d3 electronic state, which ensures a narrow emission band at 700 nm. This emission is attributed to the 2E to 4A2 transition of Cr3+, which is spin forbidden. This activator ion also features a broad emission in the wavelength range of 650–1000 nm that is spin-allowed and attributed to the 4T2 to 4A2 transition of Cr3+. PerLum from nanophosphors doped with Cr3+ was for the first time observed by Bessiere et al. [220], in the year 2011, who detected an afterglow displaying a peak at 695 nm inZnGa2O4 crystals. In the year 2012, Pan et al. [133], synthesized a novel host, Zn3Ga2Ge2O10, and doped it with Cr3+, thus achieving an afterglow of 360 h. Li et al., used a technique of partial substitution of zinc and tin in place of gallium and thus synthesized the nanophosphor Zn3Ga2SnO8. After doping this nanophosphor with 0.5 % of Cr3+, they were able to achieve a strong afterglow that lasted for 300 h in the wavelength range of near IR, thus allowing imaging of deep tissues with the advantages of being extra-long, real-time, and reliable. Most of the hosts where the activator ion used is Cr3+ are gallate-based nanophosphors, which allow the emission of photons in the visible and near-IR ranges. Afterglow in gallate-based compounds activated by Cr3+ ranges from tens of seconds [221] up to a maximum of 1000 h [222]. Some examples of such gallate-based PerLum nanomaterials are La3Ga5GeO14:Cr3+ with an afterglow of 8 h [223,224], Zn3Ga2Ge2O10: Cr3+ with an afterglow of 360 h [133,225], LiGaO5:Cr3+ with an afterglow of 1000 h [222,226,227], Ca3Ga2Ge3O12:Cr3+ co-doped with Yb3+ and Tm3+ with an afterglow of 7000 s [228,229]. In case of these gallate-based nanophosphors, Cr3+ ions replace Ga3+ ions with a coordination of 8. After gallate-based LLPs, Cr3+ can also be used as an activator in other non-gallate nanophosphors, for example, Zn2SnO4:Cr3+ and Zn(2-x)Al2xSn(1-x)O4:Cr3+, which show a broad emission spectrum ranging from 650 to 1200 nm with a peak at 800 nm and an afterglow duration of over 35 h [230].

Some of the main group elements have also been used as emission centers, and among them, Bi3+ is used as an activator for the generation of white light with light-emitting diodes. Luminescence, because of this activator ion, also depends on the coordination number of emission centers, which ensures luminescence ranging from blue to red emission. Some of the Bi3+-activated PerLum materials include CaWO4 [231,232], ZnGa2O4 [233], CdSiO3 [56,234] and Zn2GeO4 [235]. In case of all these nanophosphors, the afterglow observed was found to be in the wavelength range of UV-blue region. Also, their pattern of luminescence is influenced both by Bi2+ and Bi3+, thus giving rise to visible or near-IR PerLum.

4. Synthesis of persistent luminescence materials

Materials which show the phenomenon of PerLum are inorganic materials with high purity synthesized via different methods. A phosphor mainly comprises of a host material such as silicate, aluminate, phosphate, oxide, stannate, sulphide, titanate, nitride, halide, etc., and activator ions [209,[236], [237], [238], [239], [240], [241]]. To improve the LLPs of such phosphors, a sensitizer is also added, which acts as a mediator of energy transfer between the excitation source and activator ion [242]. For better efficiency and improved properties, phosphors must possess properties such as extra-small size, a large surface-to-volume ratio, better morphology, and a narrow particle size distribution. The method employed for the synthesis of LLPs has a very important role in determining their properties, efficiency, time of afterglow, morphology, and yield [19]. Different synthesis methods employed have their own advantages and disadvantages, which shows that it is very important to select an appropriate method of synthesis. With the solid-state method of synthesis, the strength and duration of the afterglow are improved, but the morphology and dispersibility of synthesized LLP were found to be very poor [12,14]. While combustion synthesis is advantageous in the sense that it is quick, sample, needs low energy input and generates high purity sample it also has a disadvantage of product being agglomerated along with lack of control over the morphology of the final product and shorter duration of afterglow. Other wet-chemical methods, which do not need high annealing temperatures, result in the synthesis of small molecules with improved mono-dispersity but weak emission and a shorter afterglow. Table 1 provides details about recently synthesized phosphors, along with their various characteristic properties and applications. Also, a brief description about different synthesis methods along with their merits, and demerits is discussed below.

Table 1.

Details related to some recent PerLum materials along with different dopants and co-dopants used, afterglow exhibited by them, emission wavelengths and their applications showing their importance in modern technologies and day-to-day life.

| Synthesis technique | S. No. | Host employed | Dopant/co-dopant | Afterglow duration | Emission wavelength | Application | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid state synthesis technique | 1. | ZrO2 | Tb3+ | 600 s | Radiation dosimeter in biomedical for excitation using beta rays | [243] | |

| 2. | (Ba,Sr)Ga2O4 | Sm3+ | 1400 s | 500 nm–750 nm | Multimodal material for anti-counterfeiting | [244] | |

| 3. | ZnGa2O4 | Ni2+ | More than 500 s | 1300 nm | NIR–II Window, In-vivo imaging |

[245] | |

| 4. | Ba2MgSi2O7 | Eu2+/R3+ (R=Y,La–Nd, Sm–Lu) | 6 h | 500 nm | [246] | ||

| 5. | NaGdGeO4 | Bi3+/Li+ | More than 200 h | 325 nm–525 nm, peaking at 400 nm | Biomedical | [247] | |

| 6. | BaGa2O4 | Pr3+ | 3500 s | 400 nm–550 nm | Anti-counterfeiting | [248] | |

| Combustion synthesis | 1. | (M,Ca)AlSiN3 (M = Sr, Mg) | Eu3+ | 200 min. | 500 nm–750 nm | Security, display, data storage | [249] |

| 2. | AlN | Mn2+/Si4+ | 380 s–1200 s | 600 nm | Lighting and display | [250] | |

| 3. | Ca2Ga6O14 | Pr3+ | 10.3 h | 430 nm–510 nm | Data storage | [251] | |

| 4. | Sr2MgSi2O7 | Eu/Dy | 5 h | 456 nm | Field emission display | [252] | |

| 5. | MAl2O4 (M = Sr, Ba, Ca) | Eu2+/R3+ (R=Dy, Nd, La) | 7 h | 516 nm–500 nm, 400 nm | [253] | ||

| 6. | CaAl2O4 | Eu2+/Dy3+ | 6 h | 438 nm | Displays, detectors, data storage | [254] | |

| Hydrothermal method | 1. | LiGa2O8 | Cr3+ | 10 min. | 425 nm, 610 nm | Bioimaging | [255] |

| 2. | Bi2Ga4O9 | Cr | More than 30 min | 696 nm, 706 nm | Computed tomography imaging, long term and sensitive diagnosis, | [256] | |

| 3. | Zn3Ga2SnO8 | Cr3+/Yb3+, Er3+ | 60 min | 700 nm | Advanced imaging therapy, high resolution bioimaging | [257] | |

| 4. | Zn3Ga2Ge2O10 | Cr3+ | 15 h | 697 nm | In vivo bioimaging | [258] | |

| Co-precipitation method | 1. | NaYF4 | Ln3+ | 1800 s | 480 nm–1060 nm | Optical data storage, luminescent inks | [259] |

| 2. | Sr3SiO5 | Eu2+ | 7000 s | 580 nm | White LEDs | [260] | |

| 3. | BaMoO4 | Tm3+ | 5.7 days | 453 nm, 545 nm | [261] | ||

| 4. | Ca3(PO4)2 | Mn2+, Ln3+ (Ln = Dy,Pr) | 10 min | 480 nm, 575 nm, 612 nm, 626 nm, 665 nm | In vivo imaging | [262] |

4.1. The solid-state reaction method

For the synthesis of LLP, a solid-state synthesis technique is employed, as this method ensures a longer duration of afterglow and strong luminescence. With a solid-state reaction, the physiochemical property of the synthesized material gets changed. Some of the primary factors that alter the rate of reaction are temperature and other physical conditions, reactivity, and the structural and surface properties of reactants [263]. The general procedure of solid-state reaction is shown in Fig. 8, from which we can understand the different steps involved in the process of synthesis of nanophosphors via the solid-state reaction method. In this method of synthesis, all precursors are weighted and then mixed while staring at low temperatures [264]. For decreasing the temperature needed, improving the crystallinity, and increase the rate of reaction, different fluxes such as Li2CO3, YF3, AlF3, NH4F, BAF2, boric acid, etc., are used. Apart from these, the addition of flux also helps in enhancing the temperature of the reaction must be very high because, at higher temperatures, reactants react at a faster rate, which ensures lower activation energy. The temperature during a solid-state reaction varies in a range of 1200–1600 °C, which generates a product in powder form. Other advantage of this synthesis method is that no toxic gases or waste are generated during this procedure. However, this method suffers from disadvantages such as the need for higher temperatures, a longer duration of time, weak surface morphology, low dispersibility, and homogeneity [265]. With solid-state reactions, the yield is quite good, which makes it an ideal technique for large-scale production. This technique has been most widely used for the synthesis of PerLum nanophosphors because of its already discussed advantages [[265], [266], [267], [268]]. While discussing the mechanism of LLP, as already mentioned, traps and emitters are of primary importance for this phenomenon, and high temperatures have proved very helpful for inducing lattice defects, distortions, vacancies, intrinsic defects, etc. In 2011, Pan and others [269] synthesized sunlight-activated near-IR PerLum nanophosphor via solid-state reaction. They observed that these zinc-gallogerminate ceramic discs, doped with Cr3+, displayed a very long afterglow of over 360 h. Different measurements showed that high temperatures induced the formation of oxygen and gallium vacancies, due to which trapping states with very high densities were formed. Same group also synthesized germanite-based nanophosphor LiGa2O8 doped with Cr3+ with near IR photo-stimulated LLP. This nanophosphor showed a much longer afterglow of 1000 h and was used for optical information storage [226]. Cai et al., [270] employed both high temperature solid state technique and hydrothermal technique to synthesize Cr3+ Zn1.33Ga1.34Sn0·33O4. The authors have presented that further grinding of samples can significantly impact the properties of PerLum, resulting in a reduction in intensity.

Fig. 8.

Diagram representing the general procedure of solid-state reaction for the synthesis of persistent luminescent nanomaterials.

4.2. Solution combustion method

The solution combustion method is a rather simple and easy method for the synthesis of nanophosphors. This method has the potential to save energy and time, and it can synthesize several phosphors, such as oxides, aluminates, sulphides, and highly reactive alloys [[271], [272], [273], [274], [275], [276]]. During this synthesis method, nitrates of different metals are mixed along with a suitable fuel which acts as a reducing agent, such as sucrose-PEG [277], urea-PVA [278], hexamine-PVA [278], urea-starch [279], cellulose-citric acid [271] etc. . Reducing the power of fuel is of primary importance for its selection because higher the reducing power, better will be the fuel. For this reason, urea or citric acid is used as fuel because of their high reducing power, low cost, and ease of availability. During this method of synthesis, heat is generated as it is exothermic, which results in high crystallinity in the synthesized materials. Phosphors synthesized via this method are Lu3Al5-xGaxO12 doped with Ce3+ and co-doped with Cr3+ [280], Y3Al5O12 doped with Pr3+ [281], AlN doped with Mn2+ and co-doped with Si4+ [250], Gd3Al2Ga3O12 doped with Ce3+ and co-doped with Cr3+ [282]. Synthesis of phosphors via this method primarily includes four steps (Fig. 9 [283]), viz. (a) preparation of a mixture of precursors and a suitable fuel such as urea or citric acid (b) preparation of gel by mixing them with distilled water and continuously stirring at an approximate temperature of 80–100 °C (c) Combustion of gel with the help of a furnace set at a temperature greater than 500 °C. Combustion of gel generates powder with a sub-micron size, which is crushed into fine powder. (d) This powder is then calcinated at a higher temperature to remove some extra impurities and to get better crystallinity and improved luminescence, which results in the generation of powder with high purity [273,284,285]. Some main advantages of the combustion method are better morphology, better dispersibility, easy processing, and saving energy and time, but while synthesizing PerLum materials, there are some disadvantages as well, such as a small afterglow time and a weak emission intensity.

Fig. 9.

Representation of the step-by-step process of solution combustion synthesis. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [283], Copyright 2017, Elsevier.

4.3. Template method