Abstract

Objective:

The Apathy in Dementia Methylphenidate Trial 2 (ADMET 2) found that methylphenidate was effective in treating apathy with a small-to-medium effect size but showed heterogeneity in response. We assessed clinical predictors of response to help determine individual likelihood of treatment benefit from methylphenidate.

Design:

Univariate and multivariate analyses of 22 clinical predictors of response chosen a priori.

Setting:

Data from the ADMET 2 randomized, placebo controlled multi-center clinical trial.

Participants:

Alzheimer’s disease patients with clinically significant apathy.

Measurements:

Apathy assessed with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory apathy domain (NPI-A).

Results:

In total, 177 participants (67% male, mean [SD] age 76.4 [7.9], mini-mental state examination 19.3 [4.8]) had 6-months follow up data. Six potential predictors met criteria for inclusion in multivariate modeling. Methylphenidate was more efficacious in participants without NPI anxiety (change in NPI-A −2.21, standard error [SE]:0.60) or agitation (−2.63, SE:0.68), prescribed cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEI) (−2.44, SE:0.62), between 52 and 72 years of age (−2.93, SE:1.05), had 73−80 mm Hg diastolic blood pressure (−2.43, SE: 1.03), and more functional impairment (−2.56, SE:1.16) as measured by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living scale.

Conclusion:

Individuals who were not anxious or agitated, younger, prescribed a ChEI, with optimal (73−80 mm Hg) diastolic blood pressure, or having more impaired function were more likely to benefit from methylphenidate compared to placebo. Clinicians may preferentially consider methylphenidate for apathetic AD participants already prescribed a ChEI and without baseline anxiety or agitation.

Keywords: Methylphenidate, apathy, stimulants, predictors of response

OBJECTIVE

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia, accounting for 60%−80% of all dementia diagnoses1 and affecting an estimated 6.7 million Americans aged 65 years or older in 2023.2 Apathy is the most common neuropsychiatric symptom (NPS) in AD,3,4 with a prevalence of 24%−85%.5 According to recently revised diagnostic criteria, apathy in neurocognitive disorders is defined as reduced goal-directed behavior with symptoms in at least two dimensions of diminished initiative, diminished interest and diminished emotional expression, causing significant functional impairment.6 Apathy in AD is associated with faster disease progression, greater cognitive decline, increased caregiver distress, and decreased quality of life, and hence is an important interventional target.7,8

While no treatments are currently approved for apathy in AD, growing evidence suggests that methylphenidate may provide benefit.9−11 Methylphenidate is a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that increases dopamine and norepinephrine levels. Both dopaminergic and noradrenergic dysfunction have been hypothesized to be associated with dementia related apathy.12,13 Based on this rationale, methylphenidate has been evaluated as a treatment for apathy in AD.10,11,14 The recent Apathy in Dementia Methylphenidate Trial 2 (ADMET 2) was the largest randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, phase III clinical trial that investigated the efficacy of methylphenidate for apathy in patients with mild to moderate AD.11,15 ADMET 2 found that methylphenidate treatment resulted in improvement on the neuropsychiatric inventory (NPI) apathy domain (NPI-A) with a small to medium effect size.11 However, only 43.8% of participants in the methylphenidate group, compared to 35.2% in the placebo group showed improvement on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Scale − Clinical Global Impression of Change (ADCS-CGIC), which was the coprimary outcome.11 Given the heterogeneity of response to methylphenidate in ADMET 2, we sought to identify clinical predictors that may help determine which individuals may particularly benefit from treatment.

METHODS

In ADMET 2, 200 participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive methylphenidate or placebo for 6 months. All caregivers also received a standardized psychosocial intervention at monthly study visits that consisted of a 20−30 minute counselling session with the caregiver (in addition to the participant, if they were available), the provision of educational materials (covering AD, its clinical course, symptomatic behaviors, behavioral management of apathy, expectations for medication treatments), and 24-hours availability for any crises occurring after-hours. The full inclusion and exclusion criteria have been described elsewhere.15 Briefly, participants had a diagnosis of possible or probable AD based on the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke − Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association16; with a mini-mental state exam (MMSE) score of 10−28; clinically significant apathy as evidenced by a NPI-A score of 4 or greater; pharmacological management of apathy was deemed appropriate by the study physician; availability of a caregiver who spent greater than ten hours a week with the participant; sufficient fluency of written and spoken English; and, if female, postmenopausal. Participants were excluded if they: met criteria for major depressive episode defined in the diagnostic statistical manual of mental disorder − IV (TR); had clinically significant agitation/aggression, delusions, or hallucinations on the NPI; recent changes to AD or antidepressant medications; use of trazodone greater than 50 mg or lorazepam greater than 0.5 mg for indications other than insomnia; failure to respond to past methylphenidate treatment for apathy; current or recent use of amphetamines, antipsychotics, bupropion, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants; need for acute psychiatric hospitalization or suicidal; and/or had other contraindicated medications or medical conditions.

The coprimary outcome of ADMET 2 was change on the NPI-A. The NPI measures frequency and severity of 12 NPS including apathy. Total scores are calculated by multiplying frequency (scored from 1 to 4) and severity (scored from 1 to 3); higher NPI scores indicate greater severity of symptoms.17 Measures of cognition included the MMSE and the digit span among others.15 The MMSE measures general cognition; scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating better cognitive function.18 The digit span (composed of forward and backward tests) measures working memory and short-term memory.19 The forward digit span was used in this analysis as methylphenidate was found to improve selective attention in apathetic AD patients.20 Higher scores indicate better performance on attention and verbal working memory.19 Functional abilities were assessed with the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study - Activities of Daily Living Scale (ADCS-ADL). The ADCS-ADL measures functional performance of the participant based on a structured interview with the caregiver. Higher scores indicate better performance.21

Statistical Analysis

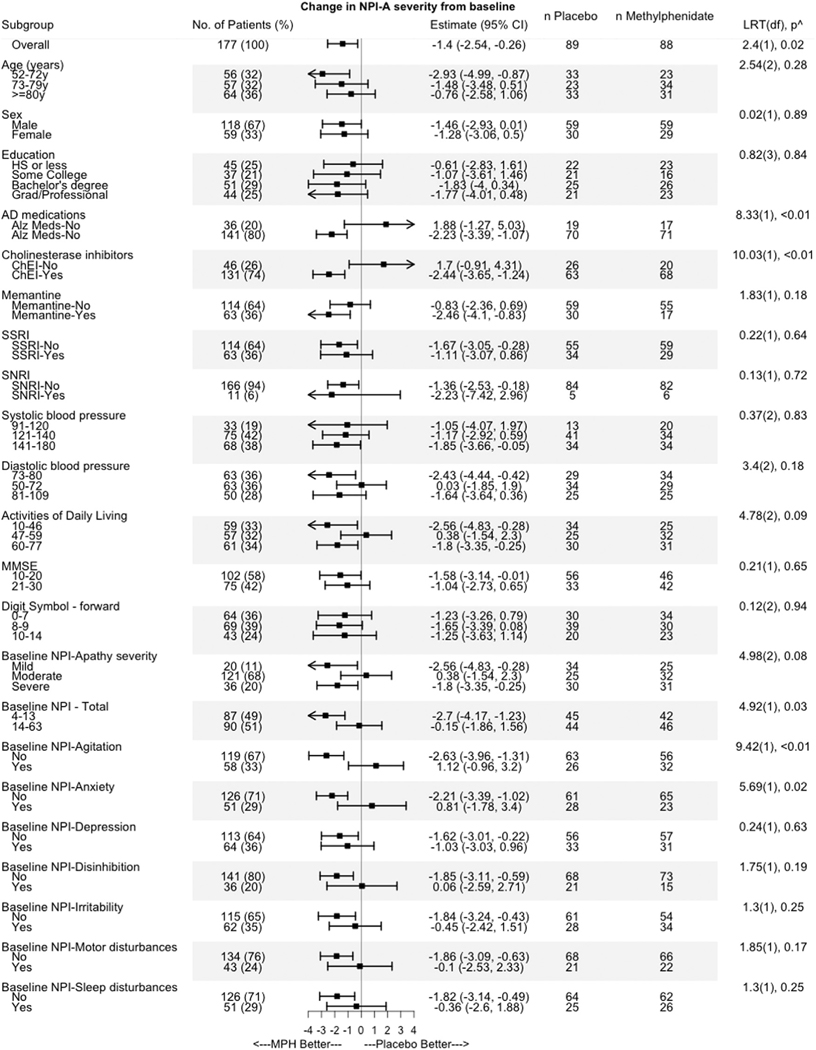

Twenty-two planned potential predictors of treatment outcome were selected based on their association with the pathophysiology of apathy and the mechanism of action of methylphenidate.13 Figure 1 describes cut-off scores for levels of each predictor. These predictors included demographics (age in three levels, sex, education in four levels), systolic and diastolic blood pressure (in three levels each), concomitant medications that may impact apathy (memantine use [yes or no], cholinesterase inhibitor use [yes or no] or AD medication use (memantine or cholinesterase inhibitors [ChEI], yes or no), SSRI use (yes or no), SNRI use (yes or no), baseline apathy severity, other NPS at baseline (NPI agitation, NPI anxiety, NPI depression, NPI disinhibition, NPI irritability, NPI aberrant motor behavior, NPI sleep disturbance - present or absent), total NPI in two levels), baseline cognition (digit span-forward in three levels, MMSE in three levels) and baseline functional impairment (ADCS-ADL in three levels). A two-step process that included a univariate and a multivariate regression to determine predictors of response was used, as done previously.22 In step one, linear regression was used to estimate the change in NPI-A from baseline to 6 months due to methylphenidate for each level of a predictor separately. Each predictor that showed a difference of at least two-points on the NPI-A between its levels was selected for the multivariate analysis (step two). A two-point difference was selected as it represented the upper bound of the overall difference between methylphenidate and placebo, which was found to be −2.03 in the ADMET 2 trial.11

FIGURE 1.

Response to methylphenidate on the NPI apathy domain score among the twenty-two planned potential predictors. AD: Alzheimer’s disease; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SNRI: serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; NPI: neuropsychiatric inventory; MMSE: mini mental state examination; ADCS-ADL: Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living. LRT(df), p^ represents the likelihood ratio test comparing models that had the independent variables treatment and predictor with or without an interaction effect, degrees of freedom, and p-value for all predictors, except for the overall analysis, which represents the t-value, degrees of freedom, and p-value.

Multivariate regression was used to model the interaction between the treatment and each predictor. This model was used to predict the change in NPI-A for each participant if they had received either placebo or methylphenidate. The difference between these two predicted NPI-A change scores determined each individual’s index score, representing the estimated treatment effect (difference between methylphenidate and placebo), given their baseline characteristics.

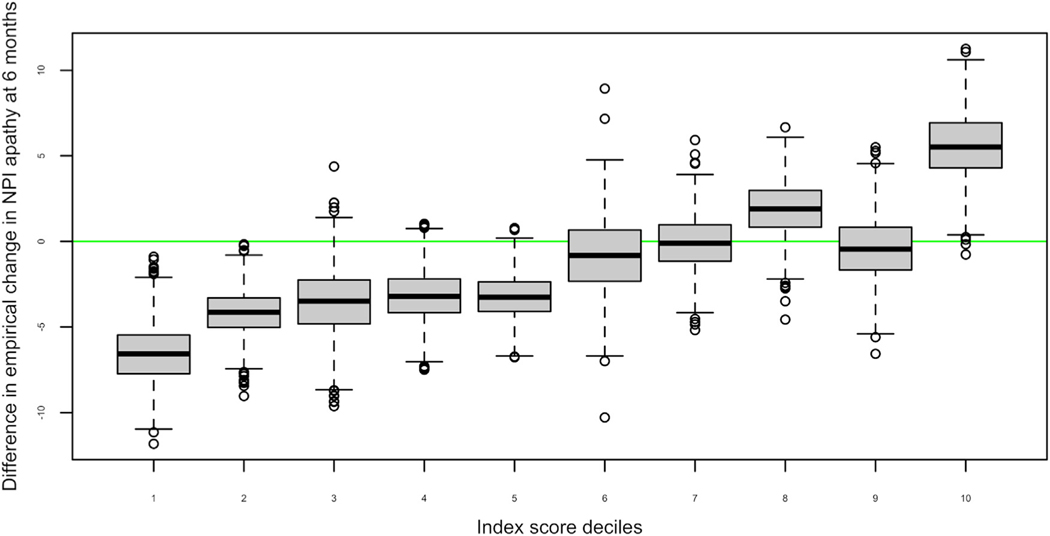

Participants were grouped into ten ordered categories (deciles) based on their index scores. Within each decile, the mean difference in the empirical change in the NPI apathy score at 6 months follow-up between participants on methylphenidate and placebo was determined, and the 95% confidence interval for each decile was estimated by bootstrapping with replacement using 1,000 iterations (Fig. 2). The proportion of responders (decrease of 4 or more points on the NPI-A) at the 3 and 6 month follow-up among those above and below the median index score at 6 months was also determined.

FIGURE 2.

Box plot of estimated change (index scores deciles) compared to empirical change in NPI-apathy after 6 months of treatment with methylphenidate. The figure shows index score deciles representing the model-based prediction of response on the NPI-A. Deciles 1−2 suggest a better response to methylphenidate, while deciles 3−9 suggest relatively little difference between methylphenidate and placebo, and decile 10 suggests a worse response on methylphenidate compared to placebo. Participant characteristics by decile group are included in Table 2.

RESULTS

The baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. In this analysis, 177 participants were included, as 23 of the original 200 ADMET 2 participants were excluded due to missing data for baseline or 6-month follow-up for NPI, medical history, MMSE or ADCS-ADL. Of these 177, 89 participants were randomized to the placebo group and 88 to the methylphenidate group. Participant demographics and baseline characteristics were similar between treatment groups. A majority of participants were male, highly educated, displayed moderate levels of apathy, and were receiving cognitive enhancing medications. As can be seen, consistent with exclusion criteria, NPI scores on agitation and depressive symptoms were relatively low (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of ADMET 2 Participants Included in Analyses

| Factor | Overall (N = 177) | Methylphenidate (n = 88) | Placebo (n = 89) | t/χ2 (df), p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 76.0 (7.8) | 76.4 (8.2) | 75.7 (7.5) | −0.88(175), 0.54 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 59 (33.3) | 29 (33.0) | 30 (33.7) | <0.01 (1), 0.99 |

| Male | 118 (66.7) | 59 (67.0) | 59 (66.3) | |

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| HS or less | 45 (25.4) | 23 (26.1) | 22 (24.7) | 0.80 (3), 0.85 |

| Some college | 37 (20.9) | 16 (18.2) | 21 (23.6) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 51 (28.8) | 26 (29.5) | 25 (28.1) | |

| Graduate/professional | 44 (24.9) | 23 (26.1) | 21 (23.6) | |

| Medications, n (%) | ||||

| Memantine | 63 (35.6) | 33 (37.5) | 30 (33.7) | 0.14 (1), 0.71 |

| Cholinesterase inhibitors | 131 (74.0) | 68 (77.3) | 63 (70.8) | 0.66 (1), 0.42 |

| SSRI | 63 (35.6) | 29 (33.0) | 34 (38.2) | 0.33 (1), 0.57 |

| SNRI | 11 (6.2) | 6 (6.8) | 5 (5.6) | <0.01 (1), 0.98 |

| Any AD medications | 141 (79.7) | 71 (80.7) | 70 (78.7) | 0.02 (1), 0.88 |

| Baseline NPI-A severity, n (%) | ||||

| Mild | 20 (11.3) | 10 (11.4) | 10 (11.2) | 1.40 (2), 0.50 |

| Moderate | 121 (68.4) | 57 (64.8) | 64 (71.9) | |

| Marked | 36 (20.3) | 21 (23.9) | 15 (16.9) | |

| Baseline blood pressure, mean (SD) | ||||

| Systolic | 136.3 (17.7) | 135.6 (18.2) | 137.0 (17.2) | 0.49 (175), 0.62 |

| Diastolic | 75.9 (10.0) | 76.4 (9.6) | 75.5 (10.3) | −0.57 (175), 0.57 |

| Baseline NPI score, mean (SD) | ||||

| Agitation | 0.8(1.3) | 0.9(1.4) | 0.7(1.2) | −0.86 (175),0.39 |

| Anxiety | 1.1(2.2) | 0.8(1.5) | 1.4(2.6) | 2.1(175),0.04a |

| Apathy | 7.9 (2.3) | 8.0 (2.4) | 7.7 (2.2) | −0.70 (175), 0.48 |

| Depression | 0.9 (1.5) | 0.8 (1.5) | 1.0 (1.5) | 0.71 (175), 0.48 |

| Disinhibition | 0.6 (1.5) | 0.4 (1.0) | 0.8 (1.9) | 1.8 (174), 0.07 |

| Irritability | 1.2 (2.1) | 1.2 (1.9) | 1.2 (2.3) | −0.2 (175), 0.82 |

| Motor | 1.1 (2.5) | 0.9 (1.8) | 1.4 (3.0) | 1.2 (175), 0.22 |

| Sleep | 1.5 (2.9) | 1.2 (2.3) | 1.6 (3.4) | 1.3 (175), 0.21 |

| Total NPI | 16.7 (10.0) | 15.6 (7.5) | 17.7 (11.9) | 1.44 (175), 0.15 |

| Baseline cognition and function, mean (SD) | ||||

| Digit span forward | 8.2 (2.4) | 8.2 (2.3) | 8.1 (2.4) | −0.04 (174), 0.97 |

| MMSE | 19.3 (4.8) | 19.6 (4.6) | 19.0 (5.0) | −0.88 (175), 0.38 |

| ADCS-ADL | 52.2 (14.0) | 53.2 (14.3) | 51.1 (13.6) | −1.03 (175), 0.31 |

Notes: Predictors were selected based on a prespecified difference of greater than or equal to two points between categories of each predictor. t/χ2 represent Student’s t-test or χ2 test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. AD: Alzheimer’s Disease; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SNRI: serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; NPI: neuropsychiatric inventory; MMSE: mini mental state examination; ADCS-ADL: Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Scale-Activities of Daily Living; HS: high school; df: degrees of freedom.

p<0.05.

The 22 predictors evaluated are shown in Figure 1. Of these 22, six predictors showed a greater than or equal to 2 point difference on the NPI-A between their levels. Methylphenidate was significantly efficacious in participants without NPI anxiety (difference in estimated change in NPI-A between levels (without and with anxiety)) or agitation, and who were prescribed ChEI, between 52 and 72 years of age, had optimal diastolic blood pressure, and greater functional impairment on the ADCS-ADL. While the use of any AD medications also met selection criteria and showed significant improvement on NPI-A with methylphenidate, ChEI prescription was selected for multivariate modeling rather than AD medications as a majority of participants considered to be using AD medications were prescribed ChEIs (Table 1).

The above six predictors were included in a multivariate model to predict change in NPI-A due to methylphenidate for each individual. The model parameters are provided in the appendix. The median index score representing the change in NPI-A due to methylphenidate compared to placebo was −1.33 [interquartile range: −3.56 to 0.15]: 79% of participants with a higher index score (>median) responded, while only 49% of those with lower index score responded. Figure 2 shows that participants in deciles 1 and 2 had a better response to methylphenidate whereas those in decile 10 showed a worse response to methylphenidate compared to placebo. The baseline characteristics of participants in these three groups are included in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of Covariates Included in Predictive Model Among Participants as per Index Score Decile Groups

| All | Deciles 1−2 | Deciles 3−9 | Decile 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Response | Better on methylphenidate | ←→ | Worse on methylphenidate | |

| Covariates | N(%) | n(%) | n(%) | n(%) |

| Cholinesterase inhibitor | 131 (74.4) | 35 (97.2) | 91 (74.0) | 5 (29.4) |

| Without agitation | 118 (67.0) | 34 (94.4) | 81 (65.9) | 3 (17.6) |

| Without anxiety | 125 (71.0) | 31 (86.1) | 90 (73.2) | 4 (23.5) |

| Age | ||||

| 52−72y | 56 (31.8) | 22 (61.1) | 29 (23.6) | 5 (29.4) |

| 73−79y | 57 (32.4) | 7 (19.4) | 46 (37.4) | 4 (23.5) |

| >=80y | 63 (35.8) | 7 (19.4) | 48 (39.0) | 8 (47.1) |

| ADCS-ADL | ||||

| 10−46 | 58 (33.0) | 21 (58.3) | 36 (29.3) | 1 (5.9) |

| 47−59 | 57 (32.4) | 2 (5.6) | 41 (33.3) | 14 (82.4) |

| 60−77 | 61 (34.7) | 13 (36.1) | 46 (37.4) | 2 (11.8) |

| Diastolic blood pressure | ||||

| 50−72 | 63 (35.8) | 2 (5.6) | 50 (40.7) | 11 (64.7) |

| 73−80 | 63 (35.8) | 19 (52.8) | 41 (33.3) | 3 (17.6) |

| 81−109 | 50 (28.4) | 15 (41.7) | 32 (26.0) | 3 (17.6) |

ADCS-ADL: Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Scale-Activities of Daily Living.

Among those randomized to methylphenidate, the model showed that the empirical proportions of response (defined a priori as >= 4pt NPI-A at month 6) were 77% among participants above the median index score (n = 44) and 38% among participants below the median index score (n = 44 each) (X2 [df = 1, N = 88) = 10.37, p = 0.0012]). We also assessed the proportion of responders at the 3-month follow-up - the response rates above and below the median index score were 73% and 40% respectively (X2 (df = 1, N = 83) = 7.42, p = 0.006). Repeating the analyses including NPI-A change scores as the dependent variable and NPI-A at baseline as a covariate did not substantially change results (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This analysis assessed potential predictors of response to methylphenidate in the ADMET 2 trial by examining 22 baseline characteristics of participants chosen a priori, based on their association with the pathophysiology of apathy and the mechanism of action of methylphenidate. The response to methylphenidate differed by at least two points on the NPI-A between the levels for six predictors. Predictors of methylphenidate response included being younger, being without baseline anxiety or agitation, prescribed a ChEI, having optimal diastolic blood pressure, and having more functional impairment. Furthermore, the six predictors were used to construct a predictive model to estimate the expected change in NPI-A, which predicted the degree of improvement in apathy from methylphenidate. By using the multivariate model, we characterized a subgroup that had a high probability of response (77%) to methylphenidate compared with placebo (38%).

This study found that individuals without baseline anxiety or agitation were more likely to respond to treatment with methylphenidate. As methylphenidate increases dopamine and norepinephrine, it may have potential activating effects. Increased sensitivity to noradrenergic signaling has been found in individuals with agitation, which may be associated with up-regulation of adrenergic receptors in the frontal lobe.23 As such, agitated AD patients with apathy may have increased noradrenergic signaling, which may reduce the potential effect of methylphenidate, reducing its efficacy. A systematic review investigating the neurochemistry of agitation in AD found that preserved dopaminergic function and diminished serotonergic activity in certain brain areas was linked to aggressive or impulsive behaviors in healthy individuals, and hyperactivity of the noradrenergic system was implicated in agitated behaviors in AD.24 As those with clinically significant agitation were excluded from the study, even low baseline levels of NPI-Agitation in those prescribed methylphenidate predicted a poorer treatment response. Norepinephrine is also involved in stress response and arousal, and dysregulation of the norepinephrine system has been shown to be involved in anxiety.25 Moreover, methylphenidate acts on the D1 and D2 dopaminergic receptors that are differentially involved in the generation of the amygdaloid anxiety response.26 As NPI-anxiety scores were higher in the placebo group, even the relatively low baseline levels of anxiety in those prescribed methylphenidate predicted a poorer treatment response. Together, the potentiating effects of methylphenidate on noradrenergic and dopaminergic circuits at the dose administered in ADMET 2 may be blunted in the presence of anxiety and agitation, thereby limiting its efficacy for apathy in AD patients.

This study also found that methylphenidate was more effective in patients taking prescribed a ChEI. In trials of ChEIs for cognition in AD, apathy as a secondary outcome was found to be improved.9 Synergistic actions of ChEI and methylphenidate could potentially boost activity in fronto-striatal circuits related to apathy, thereby resulting in more improvement in apathy symptoms. While further research is needed to determine the neurobiological basis for optimal response, the results suggest that the concomitant use of methylphenidate and ChEI medications improves apathy in AD patients.

This study did not find methylphenidate to be more effective in participants taking antidepressants, specifically SSRIs. SSRIs and SNRIs are commonly used by older adults due to their safety and tolerability profile.27 However, long-term use of these antidepressants may be associated with emotional numbness, apathy, and indifference.28 Though not demonstrated in randomized, placebo-controlled trials, studies have described apathy associated with SSRI use.29 Apathy among those on SSRIs has been shown to occur rapidly and be reversible with discontinuation of SSRIs.29 Antidepressant-induced apathy is also a problematic adverse effect of mood treatment.28 In contrast, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of methylphenidate for late life depression found that combined treatment with citalopram and methylphenidate improved mood and well-being and resulted in higher rates of remission compared to either drug alone.30 Although that study detected an improved response in measures of depression and in global clinical improvement, changes in the anxiety, apathy, and psychological resilience measures did not differ between groups on either or both medications. Those results are consistent with our findings where combined use of SSRIs and methylphenidate did not improve or worsen apathy symptoms. Given the common use of these medications in those with AD, these data suggest that the effect of methylphenidate on apathy may not be affected by concomitant SSRI use.

Methylphenidate was more efficacious in those who were in the lowest age tertile (52−72 years old) and had mid-range diastolic blood pressure (ranging from 73 to 80 mm Hg). Aging is associated with a reduction in dopamine receptors and transporters, but not synthesis, as shown in a meta-analysis.31 A positron emission tomography study found a strong negative association between D1 receptor availability and age.32 Drug-induced dopamine increase from methylphenidate administration did not decline with age, although that study cohort was relatively younger than in the present study.32 Age-related changes have also been demonstrated in the noradrenergic system.24 Importantly, in addition to any aging effects, decreased levels of dopamine and dopamine receptors12,33 and loss of neurons in the noradrenergic locus coeruleus34 are consistently observed in AD patients compared to controls. With respect to blood pressure, clinical studies have shown an association between noradrenergic tone and blood pressure regulation.35,36 Since methylphenidate increases nor-adrenergic activity, there may be a relationship between noradrenergic tone, blood pressure, and likelihood of response. As participants with diastolic blood pressure outside the middle range (below 72 mm Hg and above 80 mm Hg) did not show a greater likelihood of response, having mid-range diastolic blood pressure, indicating optimal noradrenergic tone, may be necessary for a response to methylphenidate. As the reasons for these findings are speculative, future studies may benefit from biomarkers that reflect dopaminergic and noradrenergic function.

Low functional performance was also predictive of a response to methylphenidate. Apathy has been shown to predict lower function in AD.37,38 In mild AD, neuropsychiatric symptoms including apathy were found to be the best predictors of impairment in ADL.39 Those with low function and apathy may respond better to methylphenidate due to the involvement of common neural pathways that are activated by the drug, potentially improving apathy and the ability to carry out activities of daily living. This demonstrates the importance of considering daily function (in addition to cognition) in AD outcomes, as a global cognitive measure (MMSE) did not predict response.

The multivariate model used in this paper identified the probable response of individual participants to methylphenidate given their clinical characteristics (Fig. 2). Participants with the largest predicted change on the NPI-A were grouped in deciles 1−2, who responded better to methylphenidate than placebo, while those in decile 10 responded worse. Assuming that a four point or more decline on the NPI-A represents clinically significant improvement, the multivariate model showed that at 3 months, 73% of participants on methylphenidate above the median index score were responders compared to 40% among those below the median. These effects were sustained at 6 months, as 77% on methylphenidate above the median index score were responders compared to 38% among those below the median. The multivariate model not only provides clinical utility to understand the combined relevance of patient characteristics to optimize the use of methylphenidate to improve apathy but also facilitates the individualized estimation of likely response.

Limitations were present in this analysis. Continuous predictor variables were divided into categories to facilitate understanding and interpretation, however, these divisions may be arbitrary. We did not account for multiple comparisons in the selection process, instead looking for a relatively large difference in response between methylphenidate and placebo groups. We were unable to assess predictors without sufficient data in the trial. For example, too few participants were on SNRIs and other potentially relevant concomitant medications. Similarly, very few participants living in long-term care facilities or with severe AD were recruited. However, the ADMET 2 trial attempted to recruit a sample that was representative of the real-world population, as shown by the relatively few restrictions on concomitant medications, age, and disease severity. As such, the results of the trial and this analysis reflect implications for real-world use of methylphenidate for apathy.

This post-hoc analysis found that being younger, being without baseline anxiety or agitation, prescribed a ChEI, having optimal diastolic blood pressure, and having more functional impairment characterized participants with a relatively high probability of response. These results need to be validated in further research. However, those conducting future research with methylphenidate for apathy in AD may consider excluding participants with clinically significant anxiety and agitation. It will be interesting to see if results hold using other specialized outcome measures, including those that may be more aligned with diagnostic criteria for apathy such as the NPI-C and incorporating imaging and blood-based biomarkers to advance this field and realize the potential of precision medicine in this context.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

What is the primary question addressed by this study?

Do clinical characteristics of participants in the ADMET 2 trial predict better response to methylphenidate for the treatment of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease?

What is the main finding of this study?

Participants without anxiety or agitation, who were younger, taking a cholinesterase inhibitor, with 73 −80 mm Hg diastolic blood pressure, having low functional capacity, were found to respond better to methylphenidate. Combining these characteristics in a multivariate model provided individualized prediction of treatment response.

What is the meaning of the finding?

These clinical characteristics may affect the efficacy of methylphenidate in treating apathy, and may help clinicians identify patients most likely to respond to treatment.

DISCLOSURES

Funding for ADMET 2 was provided by the National Institute on Aging (grant R01 AG046543). ST acknowledges funding support from the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging and from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Mintzer reported being an advisor for Praxis Bioresearch and Cerevel Therapeutics outside the submitted work. Dr. Lanctôt reported grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the ADMET 2 study and personal fees for serving on the advisory boards of BioXcel Therapeutics, Cerevel Therapeutics, Eisai, Exciva, Kondor Pharma, Lundbeck Otsuka, Novo Nordisk, and Sumitomo outside the submitted work. Dr. Scherer reported grants from Johns Hopkins University during the conduct of the ADMET 2 study. Dr. Rosenberg has received research grants from the National Institutes of Aging, Alzheimer’s Clinical Trials Consortium, Richman Family Precision Medicine Center of Excellence on Alzheimer’s Disease, Eisai, Functional Neuromodulation, and Lilly; honoraria from GLG, Leerink, Cerevel, Cerevance, Bioxcel, Sunovion, Acadia, Medalink, Novo Nordisk, Noble Insights, Two-Labs, Otsuka, Lundbeck, Acadia, MedaCorp, ExpertConnect, HMP Global, Synaptogenix, and Neurology Week, all outside the submitted work. Dr. Herrmann reported grants from the National Institute on Aging during the conduct of the ADMET 2 study. Dr. van Dyck reported grants from the National Institute on Aging during the conduct of the ADMET 2 study; personal fees for consulting for Roche, Eisai, Cerevel, and Ono Pharmaceutical out-side the submitted work; and grants from Roche, Eisai, Eli Lilly and Company, Biogen, Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Janssen, Genentech, UCB, Cerevel, and Merck outside the submitted work. Dr. Padala reported grants from Office of Research Development, Department of Veterans Affairs and National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the ADMET 2 study. Dr. Brawman-Mintzer reported grants from the National Institute on Aging during the conduct of the ADMET 2 study. Dr. Porsteinsson reported grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the ADMET 2 study; personal fees for serving on the data and safety monitoring boards of Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Cadent Therapeutics, Functional Neuromodulation, Novartis, and Syneos outside the submitted work; grants from Avanir Pharmaceuticals, Biogen, Eisai, Eli Lilly and Company, Genentech/Roche, Biohaven, Athira, Alector, Vaccinex, and Novartis outside the submitted work; and personal fees from Avanir, Biogen, Eisai, Alzheon, MapLight Therapeutics, Premier Healthcare Solutions, Sunovion, IQVIA, and Ono Pharmaceuticals out-side the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2023.06.002.

References

- 1.2023 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement 2023; 19(4):1598–1695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajan KB, Weuve J, Barnes LL, et al. : Population estimate of people with clinical Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in the United States (2020−2060). Alzheimer’s Dement 2021; 17(12):1966–1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lanctôt KL, Amatniek J, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. : Neuropsychiatric signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease: new treatment paradigms. Alzheimer’s Dement Transl Res Clin Interv 2017; 3 (3):440–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao QF, Tan L, Wang HF, et al. : The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2016; 190:264–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung DKY, Chan WC, Spector A, et al. : Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and apathy symptoms across dementia stages: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2021; 36(9):1330–1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller DS, Robert P, Ereshefsky L, et al. : Diagnostic criteria for apathy in neurocognitive disorders. Alzheimer’s Dement 2021; 17(12):1892–1904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nobis L, Husain M: Apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Behav Sci 2018; 22:7–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mortby ME, Adler L, Agüera-Ortiz L, et al. : Apathy as a treatment target in Alzheimer’s disease: implications for clinical trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2022; 30(2):119–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruthirakuhan MT, Herrmann N, Abraham EH, et al. : Pharmacological interventions for apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 2018(5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenberg PB, Lanctôt KL, Drye LT, et al. : Safety and efficacy of methylphenidate for apathy in Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2013; 74(8):810–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mintzer J, Lanctôt KL, Scherer RW, et al. : Effect of methylphenidate on apathy in patients with Alzheimer disease: the ADMET 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 2021; 78 (11):1324–1332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell RA, Herrmann N, Lanctôt KL: The role of dopamine in symptoms and treatment of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurosci Ther 2011; 17(5):411–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Dyck CH, Arnsten AFT, Padala PR, et al. : Neurobiologic rationale for treatment of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease with methylphenidate. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2021; 29(1):51–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Padala PR, Padala KP, Lensing SY, et al. : Methylphenidate for apathy in community-dwelling older veterans with mild Alzheimer’s disease: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2018; 175(2):159–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scherer RW, Drye L, Mintzer J, et al. : The Apathy in Dementia Methylphenidate Trial 2 (ADMET 2): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2018; 19(1):1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. : Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1984; 34(7):939–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cummings JL: The neuropsychiatric inventory. Neurology 1997; 48(5 suppl 6):10S–16S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12(3):189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wechsler D: Wechsler adult intelligence scale: revised manual. In: The Psychological Corporation. New York, 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanctôt KL, Chau SA, Herrmann N, et al. : Effect of methylphenidate on attention in apathetic AD patients in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Int Psychogeriatrics 2014; 26(2): 239–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galasko D, Bennett D, Sano M, et al. : An inventory to assess activities of daily living for clinical trials in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1997; 11(SUPPL. 2) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider LS, Frangakis C, Drye LT, et al. : Heterogeneity of treatment response to citalopram for patients with Alzheimer’s disease with aggression or agitation: the citad randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry 2016; 173(5):465–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrarini C, Russo M, Dono F, et al. : Agitation and dementia: prevention and treatment strategies in acute and chronic conditions. Front Neurol 2021; 12:644317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu KY, Stringer AE, Reeves SJ, et al. : The neurochemistry of agitation in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev 2018; 43:99–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goddard AW, Ball SG, Martinez J, et al. : Current perspectives of the roles of the central norepinephrine system in anxiety and depression. Depress Anxiety 2010; 27(4):339–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de la Mora MP, Gallegos-Cari A, Arizmendi-García Y, et al. : Role of dopamine receptor mechanisms in the amygdaloid modulation of fear and anxiety: structural and functional analysis. Prog Neurobiol 2010; 90(2):198–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crocco EA, Jaramillo S, Cruz-Ortiz C, et al. : Pharmacological management of anxiety disorders in the elderly. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry 2017; 4(1):33–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plowden KO: Antidepressant-related apathy: implications for practice. J Nurse Pract 2019; 15(2):164–170 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Padala PR, Padala KP, Majagi AS, et al. : Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors-associated apathy syndrome: a cross sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020; 99(33):e21497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lavretsky H, Reinlieb M, Cyr NS, et al. : Citalopram, methylphenidate, or their combination in geriatric depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2015; 172 (6):561–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karrer TM, Josef AK, Mata R, et al. : Reduced dopamine receptors and transporters but not synthesis capacity in normal aging adults: a meta-analysis. Neurobiol Aging 2017; 57: 36–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manza P, Shokri-Kojori E, Demiral ŞB, et al. : Age-related differences in striatal dopamine D1 receptors mediate subjective drug effects. J Clin Invest 2023; 133(1):e164799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan X, Kaminga AC, Wen SW, et al. : Dopamine and dopamine receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front Aging Neurosci 2019; 11:175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Chen T, Hou R: Locus coeruleus in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Alzheimer’s Dement Transl Res Clin Interv 2022; 8(1):e12257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bremner JD, Krystal JH, Southwick SM, et al. : Noradrenergic mechanisms in stress and anxiety: II. Clinical studies. Synapse 1996; 23(1):39–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeQuattro V, Sullivan P, Minagawa R, et al. : Central and peripheral noradrenergic tone in primary hypertension. Fed Proc 1984; 43(1):47–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lechowski L, Benoit M, Chassagne P, et al. : Persistent apathy in Alzheimer’s disease as an independent factor of rapid functional decline: the REAL longitudinal cohort study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009; 24(4):341–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Starkstein SE, Jorge R, Mizrahi R, et al. : A prospective longitudinal study of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006; 77(1):8–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Delgado C, Vergara RC, Martínez M, et al. : Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease are the main determinants of functional impairment in advanced everyday activities. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2019; 67(1):381–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.