Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of different non-pharmacological interventions for pain management in preterm infants and provide high-quality clinical evidence.

Methods

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of various non-pharmacological interventions for pain management in preterm infants were searched from PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and the Cochrane Library from 2000 to the present (updated March 2023). The primary outcome was pain score reported as standardized mean difference (SMD). The secondary outcomes were oxygen saturation and heart rate reported as the same form.

Results

Thirty five RCTs of 2134 preterm infants were included in the meta-analysis, involving 6 interventions: olfactory stimulation, combined oral sucrose and non-nutritive sucking (OS + NNS), facilitated tucking, auditory intervention, tactile relief, and mixed intervention. Based on moderate-quality evidence, OS + NNS (OR: 3.92, 95% CI: 1.72, 6.15, SUCRA score: 0.73), facilitated tucking (OR: 2.51, 95% CI: 1.15, 3.90, SUCRA score: 0.29), auditory intervention (OR: 2.48, 95% CI: 0.91, 4.10, SUCRA score: 0.27), olfactory stimulation (OR: 1.80, 95% CI: 0.51, 3.14, SUCRA score: 0.25), and mixed intervention (OR: 2.26, 95% CI: 0.10, 4.38, SUCRA score: 0.14) were all superior to the control group for pain relief. For oxygen saturation, facilitated tucking (OR: 1.94, 95% CI: 0.66, 3.35, SUCRA score: 0.64) and auditory intervention (OR: 1.04, 95% CI: 0.22, 2.04, SUCRA score: 0.36) were superior to the control. For heart rate, none of the comparisons between the various interventions were statistically significant.

Conclusion

This study showed that there are notable variations in the effectiveness of different non-pharmacological interventions in terms of pain scores and oxygen saturation. However, there was no evidence of any improvement in heart rate.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12887-023-04488-y.

Keywords: Non-pharmacological intervention, Neonatal intensive care unit, Preterm infant, Pain, Network meta-analysis

Introduction

Preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) frequently undergo painful procedures such as venipuncture, heel-stick, and endotracheal suctioning, as well as orogastric tube insertion [1]. The pain and stress from frequent procedures can have both transient and enduring impacts on the behavior, physiology, and neurodevelopment of preterm infants [2]. Research indicated that at 7 years of age, preterm children who underwent more invasive neonatal procedures had higher salivary cortisol levels and internalizing behavior scores greater than full-term children [3]. Another research found that cumulative pain and stress were associated with neurobehavioral outcomes such as stress/abstinence and habituation responses in preterm infants [4]. Reports from South Korea, Canada and Kenya indicated that many preterm infants continued to receive highly invasive procedures without adequate analgesia, highlighting an ongoing need to improve pain management practices in this vulnerable population [5–8].

Given the suboptimal pain management practices and risk of adverse outcomes demonstrated in preterm infants, there is growing interest in identifying and evaluating effective analgesic interventions for this population. However, a review reported that commonly used anesthetic and sedative agents may have both acute and long-term detrimental neurological impacts in preterm infants [9]. The American Academy of Pediatrics also stated that the long-term effects and safety of pharmacologic analgesia are yet to be studied [10]. Clearly, there is a need to explore alternative, neuroprotective pain management strategies in this vulnerable population. In recent years, non-pharmacological interventions such as skin-to-skin contact, non-nutritive sucking, facilitated tucking position, breastfeeding, oral sucrose, olfactory stimulation, and music therapy have emerged as effective methods for pain management in preterm infants [11, 12]. Evidence has already confirmed their efficacy and safety in pain management and some other pain-related indicators such as oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, and heart rate [13–18].

Previous systematic reviews have primarily examined the effectiveness of individual or combined non-pharmacologic interventions for the treatment of pain in preterm infants [13–15, 17, 18]. While there have been several recent systematic reviews assessing the effectiveness of different non-pharmacological interventions, it is important to note that these reviews have not encompassed the entire spectrum of interventions, and the evidence has not been consolidated [11, 16, 19, 20]. As such, the objective of this network meta-analysis is to integrate various non-pharmacological interventions and evaluate their efficacy in managing pain in preterm infants, providing high-quality clinical evidence for improving pain care.

Methods

Search strategy

The review was conducted and reported following the PRISMA guidelines [21]. The protocol for this meta-analysis has been registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42023412200). We searched PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and the Cochrane Library for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) from 2000 to the present (updated March 2023) using the targeted search strategy provided in the Data Supplement (Additional file 1: Appendix Table 1). The search was restricted to English articles. The search strategy used both medical subject heading terms and keywords for pain, infant, preterm, neonatal intensive care unit and so on.

Study selection

Two authors (Yuwei Weng and Jie Zhang) independently evaluated the articles to determine their eligibility for inclusion, and differences were addressed by agreement. The eligible full texts were reviewed after they were screened for titles and abstracts (Fig. 1). The criteria for inclusion were as follows: (1) The participants were preterm infants in the NICU (gestational age < 37 weeks). (2) Studies were RCTs. (3) The experimental group implemented tactile relief (Kangaroo mother care, massage, etc.), auditory intervention (mothers’ voice, white noise, lullaby, etc.), olfactory stimulation (maternal breast milk odor, vanilla odor, amniotic fluid odor, etc.), combined oral sucrose and non-nutritive sucking (OS + NNS), facilitated tucking, or mixed intervention. (4) The control group received routine nursing care, including placebo, pacifier, and incubator. The criteria for exclusion were as follows: (1) Full-term infants or other non-preterm infants. (2) Results of pain score, oxygen saturation and heart rate were ambiguous or missing. (3) Non-RCTs, non-English literature, non-human studies, repeated publications, reviews, and meta-analyses were excluded.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study inclusion and exclusion

Data extraction

Two authors (Yuwei Weng and Jie Zhang) independently reviewed the article and extracted relevant data and parameters. The EndNote X9 software was used to import all the retrieved articles, and duplicates were removed. After a preliminary selection of titles and abstracts, the remaining eligible articles were checked for full text according to the prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria. When the eligible articles were reviewed, the following parameters were extracted: first author, publication year, RCT design, participants, intervention and control groups (sample size), gestational age and birth weight, painful procedures, and outcomes. Any discrepancies were resolved with the assistance of the third author (Zhifang Chen) throughout the entire process of study search, article review, and data extraction.

Quality assessment

To assess the risk of bias in the included RCTs, two authors (Yuwei Weng and Jie Zhang) independently used the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool [22]. This tool evaluated six aspects of the studies, namely selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other bias. Each aspect was evaluated through one or more items and was classified as low, high, or unclear risk. Due to the large number of interventions and articles involved in this meta-analysis, if there was any disagreement in the evaluation process, consensus would be reached through discussion. In addition, the certainty of evidence was assessed using the Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis (CINEMA) [23] framework, which comprises six domains: within-study bias, reporting bias, indirectness, imprecision, heterogeneity, and incoherence. The certainty of the results was graded as high, moderate, low, or very low.

Outcomes

The main outcome was pain score. The extraction of pain data was based on the last time node. Data were expressed as continuous variables (SMD). The results of the pain score were evaluated using the Premature Infant Pain Profifile (PIPP) [24]. The scale is a tool designed to assess pain in preterm infants who are between 28 to 36 weeks of gestation. It consists of seven items, which are further categorized into three behavioral items, two physiological items, and two contextual items. The scale was revised and promoted in 2014 to improve its accuracy and sensitivity in consideration of psychometric properties for extremely low gestational age (ELGA) infants and feedback from clinical medical staff on the percentage calculation problem [25]. The scale measures pain on a range of 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating more significant pain. The secondary outcomes measured were oxygen saturation and heart rate. The form of data presentation and the time nodes extracted were consistent with the pain score.

Statistical analysis

Standardized mean differences were initially chosen based on the expression of continuous variables. Following this, the Cochran’s Q statistic and the I2 statistic were used to explore the heterogeneity among studies. The random-effects model was chosen when there was heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 50%). Otherwise, the fixed-effects model was chosen [26, 27]. Afterwords, the efficacy of various interventions was assessed using network meta-analysis, with the consistency of direct and indirect comparisons being evaluated using the loop inconsistency test, and the efficacy ranking of the interventions was observed. Subsequent to the main analysis, sensitivity analyses were carried out and the possibility of publication bias was evaluated through the use of funnel plots. Ultimately, all statistical assessments were conducted with the aid of Stata version 17.0 and the gemte package in R software [28].

Results

Study selection

A comprehensive search was conducted on PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and the Cochrane Library, resulting in the identification of 14,456 publications. After removing duplicates, 9,996 publications were reviewed. Through preliminary screening of titles and abstracts, 130 studies were identified that focused on non-pharmacological interventions for pain in preterm infants. Of these, 1 was excluded because the full text was unavailable. After reviewing the remaining 129 publications, 13 were excluded due to the fact that the study subjects were not preterm infants. Additionally, 10 publications were excluded because the study sites were not NICUs. 26 publications were excluded due to incomplete or missing outcome data, while 15 were excluded because the control group received non-routine care. Therefore, 35 RCTs of 2134 preterm infants included at the end [29–63]. The PRISMA flow diagram of the included studies is presented in Fig. 1.

Table 1 presents the categorization of the studies based on their characteristics. The studies included in this analysis were published between 2000 to the present (updated March 2023), and the sample size ranged from 20 [35] to 200 [57]. The mean gestational age of preterm infants varied between 26 [45, 60] to 37 [31, 38, 58, 63] weeks, while the mean birth weight ranged from 932.3 [62] to 2,299.03 [30] grams. In addition, the design of RCTs, painful procedures, details of grouping, and outcomes for all studies were also summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| First author, year | RCT design | Participants/Intervention/Control (sample size) | Gestational age(week)/Birth weight(g) | Painful procedures | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baudesson de Chaville, 2017 [34] | Double-blind, placebo-controlled, RCT, two parallel groups |

G1: MBMO (n = 16) G2: control: an odorless diffuser (n = 17) |

Total: 33.2 (31.6–34.1) Total: 1790 (1647–1947) |

Venipuncture | PIPP score |

| Jebreili 2015 [44] | RCT, three parallel groups |

G1: MBMO (n = 45) G2: vanilla odor (n = 45) G3: control: routine nursing care (n = 45) |

G1: 31.64 ± 2.1/1,566.9 ± 414.89 G2: 30.93 ± 2 /1,505.3 ± 409.12 G3: 31.46 ± 1.96 /1,569.8 ± 405.93 |

Venipuncture | PIPP score |

| Alemdar, 2017 [48] | RCT, four parallel groups |

G1: amniotic fluid odor (n = 21) G2: MBMO (n = 22) G3: mother odor (n = 20) G4: control: routine nursing care (n = 22) |

G1: 33.95 ± 3.20 /2,235.04 ± 801.76 G2: 32.09 ± 3.42 /1,939.00 ± 836.78 G3: 33.05 ± 3.17 /2,120.10 ± 797.15 G4: 33.40 ± 3.11 /2,193.06 ± 679.80 |

Heel-stick |

PIPP score Heart rate Oxygen saturation |

| Alemdar, 2020 [30] | RCT, two parallel groups |

G1: amniotic fluid odor (n = 30) G2: control: routine nursing care (n = 31) |

G1: 31.30 ± 2.57 /1,734.73 ± 599.04 G2: 33.90 ± 3.17 /2,299.03 ± 758.21 |

Peripheral cannulation | PIPP score |

| Usta, 2021 [61] | Double-blind, placebo-controlled, RCT, two parallel groups |

G1: lavender oil odor (n = 31) G2: control: distilled, odorless water (n = 30) |

G1: 32.45 ± 2.29 /1834.45 ± 448.51 G2: 33.10 ± 2.75 /1961.93 ± 522.82 |

Heel lance | PIPP-R score |

| Rad, 2021 [55] | Single-blind, placebo-controlled, RCT, three parallel groups |

G1: MBMO (n = 30) G2: another mother’s breast milk odor (n = 30) G3: control: distilled water (n = 30) |

G1: 32.9 ± 2.4 /1806 ± 553 G2: 30.3 ± 3.2 /1620 ± 425 G3: 32.5 ± 2.4 /1688 ± 404 |

HBV injection |

PIPP score Heart rate Oxygen saturation |

| Asmerom, 2013 [33] | Double-blind, RCT, three parallel groups |

G1: OS + NNS (n = 44) G2: sterile water + NNS (n = 45) G3: control: routine nursing care (n = 42) |

G1: 30.1 ± 3.1 /1374.1 ± 552 G2: 31.5 ± 2.1 /1498.4 ± 706 G3: 30.5 ± 2.6 /1456.4 ± 502 |

Heel lance |

PIPP score Heart rate Oxygen saturation |

| Dilli, 2014 [37] | Placebo-controlled, RCT, two parallel groups |

G1: OS + NNS (n = 32) G2: control: sterile water + pacifier (n = 32) |

G1: 28.2 ± 2.7 /1248 ± 392 G2: 28.8 ± 2.9 /1360 ± 530 |

ROP screening | PIPP score |

| Gao, 2018 [41] | RCT, four parallel groups |

G1: OS (n = 21) G2: NNS (n = 22) G3: OS + NNS (n = 22) G4: control: routine nursing care (n = 21) |

G1: 31.7 ± 0.9 /1780.8 ± 304.6 G2: 31.9 ± 1.1 /1767.3 ± 302.7 G3: 32.0 ± 0.8 /1697.1 ± 254.7 G4: 31.3 ± 0.6 /1682.7 ± 200.2 |

Heel-stick |

PIPP score Heart rate Oxygen saturation |

| Liaw, 2012 [51] | RCT, three cross-over groups |

G1: FT (n = 34) G2: NNS (n = 34) G3: control: routine nursing care (n = 34) |

Total: 33.98 ± 2.0 Total: 1705.9 ± 363.3 |

Heel-stick | PIPP score |

| Sundaram, 2013 [59] | Single-blind, RCT, two cross-over groups |

G1: FT (n = 20) G2: control: routine nursing care (n = 20) |

Total: 34.11 ± 2.29 Total: 2153 ± 532.84 |

Heel-stick | PIPP score |

| Alinejad-Naeini, 2014 [31] | RCT, two cross-over groups |

G1: FT (n = 34) G2: control: routine nursing care (n = 34) |

Total: 29 ~ 37 weeks Total: ≥ 1200 g |

Endotracheal suctioning | PIPP score |

| Hill, 2005 [42] | RCT, two cross-over groups |

G1: FT (n = 12) G2: control: routine nursing care (n = 12) |

Total: 28.8 ± 2.8 Total: 1410 ± 473 |

Routine care (nasogastric tube insertion) | PIPP score |

| Ward-Larson, 2004 [62] | RCT, two cross-over groups |

G1: FT (n = 40) G2: control: routine nursing care (n = 40) |

Total: 27.313 ± 2.430 Total: 932.30 ± 284.05 |

Endotracheal suctioning | PIPP score |

| Davari, 2019 [36] | RCT, two cross-over groups |

G1: FT (n = 40) G2: control: routine nursing care (n = 40) |

Total: 32 ~ 36 weeks Total: ≥ 1200 g |

Heel-stick | PIPP score |

| Apaydin, 2020 [32] | RCT, six parallel groups |

G1: swaddling (n = 30) G2: FT (n = 32) G3: EBM (n = 31) G4: swaddling + EBM (n = 30) G5: FT + EBM (n = 31) G6: control: routine nursing care (n = 33) |

Total: 33.11 ± 0.84 Total: 1989.41 ± 369.51 |

Orogastric tube insertion |

PIPP score Heart rate Oxygen saturation |

| Döra, 2021 [38] | RCT, three parallel groups |

G1: white noise (n = 22) G2: lullaby (n = 22) G3: control: routine nursing care (n = 22) |

Total: 32 ~ 37 weeks Total: ≥ 1001 g |

Venous blood collection |

PIPP score Heart rate Oxygen saturation |

| Yu, 2022 [63] | Double-blind, RCT, two parallel groups |

G1: maternal heart sounds (n = 32) G2: control: routine nursing care (n = 32) |

Total: < 37 weeks Total: 1860.92 ± 506.26 |

Heel-stick |

Heart rate Oxygen saturation |

| Kahraman, 2020 [47] | RCT, four parallel groups |

G1: white noise (n = 16) G2: mothers’ voice (n = 16) G3: MiniMuffs (n = 16) G4: control: routine nursing care (n = 16) |

G1: 33.8 ± 1.75 /1909 ± 340 G2: 34.0 ± 1.50 /1904 ± 325 G3: 34.06 ± 1.76 /2186 ± 621 G4: 34.25 ± 1.65 /2201 ± 615 |

Heel lance |

Heart rate Oxygen saturation |

| Kurdahi Badr, 2017 [50] | Double-blind, RCT, three cross-over groups |

G1: lullaby (n = 42) G2: mother's music (n = 42) G3: control: routine nursing care + headphones (n = 42) |

Total: 31.78 ± 2.8 Total: 1577 ± 499.2 |

Heel-stick |

Heart rate Oxygen saturation |

| Kucukoglu, 2016 [49] | RCT, two parallel groups |

G1: white noise (n = 35) G2: control: routine nursing care (n = 40) |

G1: 31.77 ± 3.30 /1673.29 ± 321.16 G2: 31.30 ± 2.50 /1530.62 ± 347.25 |

HBV injection |

PIPP score Heart rate Oxygen saturation |

| Taplak, 2021 [60] | RCT, four parallel groups |

G1: BMO (n = 20) G2: white noise (n = 20) G3: FT (n = 20) G4: control: routine nursing care (n = 20) |

Total: 26 ~ 35.6 weeks Total: ≤ 1500 g (n = 38), ≥ 1501 g (n = 42) |

Endotracheal suctioning |

PIPP-R score Heart rate Oxygen saturation |

| Alemdar, 2018 [29] | RCT, four parallel groups |

G1: BMO (n = 32) G2: maternal voice (n = 30) G3: incubator cover (n = 31) G4: control: routine nursing care (n = 32) |

G1: 30.26 ± 0.69 /1430.70 ± 146.00 G2: 30.06 ± 0.63 /1460.50 ± 133.36 G3: 30.22 ± 0.66 /1404.80 ± 99.23 G4: 30.25 ± 0.50 /1503.80 ± 194.86 |

Peripheral cannulation | PIPP score |

| Mitchell, 2013 [52] | RCT, two parallel groups |

G1: KC (n = 19) G2: control: routine nursing care (n = 19) |

Total: 27 ~ 30 weeks G1: 1311.5 ± 216.3 G2: 1213.2 ± 186.4 |

Routine care (suctioning via tracheal or nasal routes) | PIPP score |

| Cong, 2011 [35] | RCT, two cross-over groups |

G1: KC (n = 10) G2: control: routine nursing care (n = 10) |

Total: 30 ~ 32 weeks Total: 1577 ± 327 |

Heel-stick | PIPP score |

| Srivastava, 2022 [58] | Open label, RCT, two parallel groups |

G1: KMC (n = 40) G2: control: routine nursing care (n = 40) |

Total: 28 ~ 37 weeks Total: 1500-2499 g |

Orogastric tube insertion | PIPP-R score |

| Johnston, 2008 [46] | Single-blind, RCT, two cross-over groups |

G1: KMC (n = 61) G2: control: routine nursing care (n = 61) |

Total: 28 0/7 ~ 31 0/7 weeks | Heel lance | PIPP score |

| Johnston, 2013 [45] | RCT, two parallel groups |

G1: therapeutic touch (n = 27) G2: control: routine nursing care (n = 28) |

Total: 26 0/7 ~ 28 6/7 weeks G1: 974.54 ± 188 G2: 977.44 ± 210 |

Heel lance | PIPP score |

| Fatollahzade, 2022 [40] | RCT, two cross-over groups |

G1: GHT (n = 34) G2: control: routine nursing care (n = 34) |

Total: 27 ~ 34 weeks Total: ≥ 1200 g |

Endotracheal suctioning | PIPP score |

| Sezer Efe, 2022 [56] | Assessor-blind, RCT, two parallel groups |

G1: GHT (n = 25) G2: control: routine nursing care (n = 25) |

G1: 34.95 ± 1.61 /2272.70 ± 430.19 G2: 35.3 ± 1.83 /2289.37 ± 630.80 |

Heel lance |

Heart rate Oxygen saturation |

| Dur, 2020 [39] | RCT, three parallel groups |

G1: GHT (n = 30) G2: Yakson touch (n = 30) G3: control: routine nursing care + pacifier (n = 30) |

Total: 33.44 ± 1.74 Total: 1960.83 ± 413.75 |

Heel lance |

Heart rate Oxygen saturation |

| Jain, 2006 [43] | Double-blind, RCT, two cross-over groups |

G1: massage (n = 23) G2: control: routine nursing care (n = 23) |

Total: 31.1 ± 1.9 Total: 1693 ± 396 |

Heel-stick |

Heart rate Oxygen saturation |

| Qiu, 2017 [54] | RCT, two parallel groups |

G1: music + GHT (n = 30) G2: control: routine nursing care (n = 32) |

G1: 34.30 ± 0.67 /1930 ± 130 G2: 33.33 ± 0.54 /2000 ± 70 |

Routine care (tracheal aspiration, nasal aspiration, removal of intravenous lines, etc.) | PIPP score |

| Shukla, 2018 [57] | Double-blind, RCT, four parallel groups |

G1: KMC (n = 50) G2: music therapy (n = 49) G3: KMC + music therapy (n = 50) G4: control: routine nursing care (n = 51) |

Total: 34.0 ± 2.32 Total: 1910 ± 340 |

Heel prick | PIPP score |

| Perroteau 2018 [53] | RCT, two parallel groups |

G1: FT + NNS (n = 30) G2: control: routine nursing care + pacifier (n = 29) |

Total: 29.0 (28.0–31.0) Total: 1300.0 (1130.0–1530.0) |

Heel-stick | PIPP score |

MBMO Maternal breast milk odor, BMO Breast milk odor, EBM Expressed breast milk, OS Oral sucrose, NNS Non-nutritive sucking, FT Facilitated tucking, KC Kangaroo care, KMC Kangaroo mother care, GHT Gentle human touch

Risk of bias in included studies

Figure 2 reported the results of the bias risk assessment for the included studies. Of the allocation concealment methods, 3 studies [53, 56, 58] were marked as high risk for not applying, 17 [29–31, 36, 39–42, 44, 46, 48, 49, 51, 52, 54, 55, 62] were marked as unclear risk for not being mentioned in the study, and the remaining were marked as low risk. In the blinding of participants and personnel, 2 studies [58, 59] took a high risk since they couldn’t apply the blinding, and 28 [29–32, 35, 36, 38–42, 44–57, 60, 62, 63] were marked as unclear risk. In the blinding of outcome assessment, 8 studies [29, 30, 33, 35, 47, 48, 51, 52] were found to be marked as high risk for not applying the blinding and 10 [31, 36–39, 41, 42, 58, 61, 62] were marked as unclear risk. Among other bias, 1 study [56] was marked as high risk as the study personnel and outcome assessment was the same person. In addition, all studies explained the use of randomization methods and were accordingly marked as low risk. Incomplete outcome data and selective reporting were also not found in the studies.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias graph

PIPP scores

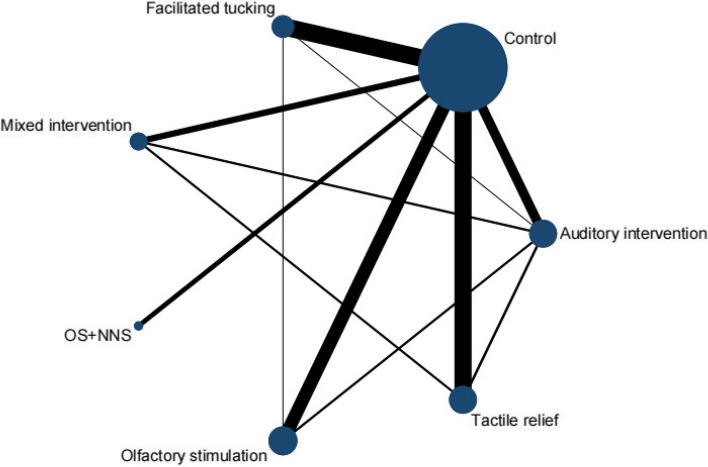

A total of 29 RCTs [29–38, 40–42, 44–46, 48, 49, 51–55, 57–62] were included in this meta-analysis by PIPP score, involving 6 interventions. Olfactory stimulation (8 RCTs), OS + NNS (3 RCTs), facilitated tucking (8 RCTs), auditory intervention (5 RCTs), tactile relief (7 RCTs), and mixed intervention (3 RCTs) were included. A total of 7 nodes were included in this meta-analysis, with each node representing an intervention or control (Fig. 3). The nodes with more significant interactions were control (34 interactions), olfactory stimulation (11 interactions), auditory intervention (10 interactions), facilitated tucking (9 interactions), and tactile relief (8 interactions). The results of the consistency analysis was shown in Additional file 1: Appendix Table 2. The results of the heterogeneity test indicated a high degree of heterogeneity with an I2 value of 97.1%.

Fig. 3.

Network evidence diagram (PIPP score)

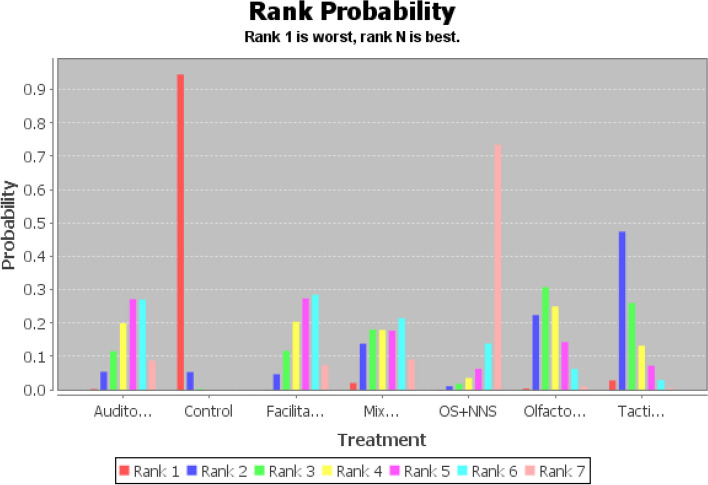

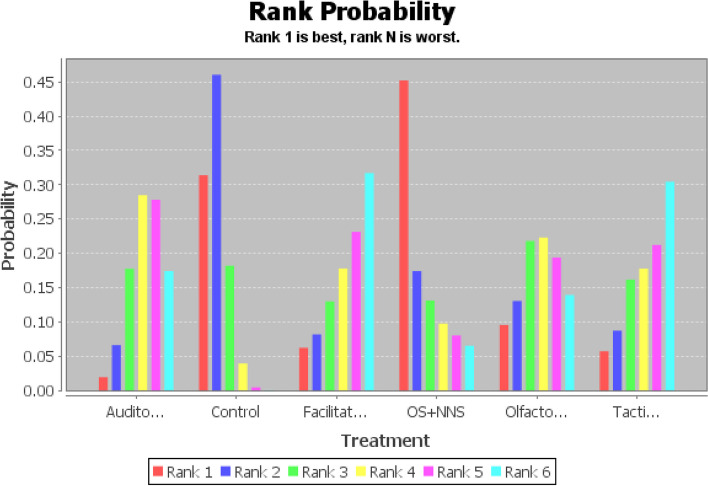

Based on moderate-quality evidence (Additional file 1: Appendix Table 5), OS + NNS had the greatest SUCRA score, followed by facilitated tucking, auditory intervention, olfactory stimulation, tactile relief, mixed intervention, and control group (Fig. 4 and Additional file 1: Appendix Table 3). Compared to the control group, OS + NNS was 3.92 (95% CI: 1.72,6.15, SUCRA score: 0.73) lower, facilitated tucking was 2.51 (95% CI: 1.15,3.90, SUCRA score: 0.29) lower, auditory intervention was 2.48 (95% CI: 0.91. 4.10, SUCRA score: 0.27) lower, olfactory stimulation was 1.80 (95% CI:0.51,3.14, SUCRA score: 0.25) lower, and mixed intervention was 2.26 (95% CI:0.10,4.38, SUCRA score: 0.14) lower (Table 2). This study found that the comparison between tactile relief and the control group wasn’t statistically significant (OR: 1.38, 95% CI: -0.11,2.87, SUCRA score: 0.26). Therefore, the complete probability ranking was OS + NNS (73%) > facilitated tucking (29%) > auditory intervention (27%) > olfactory stimulation (25%) > mixed intervention (14%) > control group (94%) (Additional file 1: Appendix Table 3). The stability and credibility of the results were demonstrated in Additional file 1: Appendix Table 4 through the sensitivity analysis.

Fig. 4.

Probability ranking diagram of best interventions (PIPP score)

Table 2.

The results of network meta-analysis (consistency model, PIPP score)

| Auditory intervention | 2.48 (0.91, 4.10) | -0.04 (-2.03, 2.01) | 0.22 (-2.33, 2.77) | -1.45 (-4.16, 1.31) | 0.68 (-1.19, 2.56) | 1.10 (-1.00, 3.22) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -2.48 (-4.10, -0.91) | Control | -2.51 (-3.90, -1.15) | -2.26 (-4.38, -0.10) | -3.92 (-6.15, -1.72) | -1.80 (-3.14, -0.51) | -1.38 (-2.87, 0.11) |

| 0.04 (-2.01, 2.03) | 2.51 (1.15, 3.90) | Facilitated tucking | 0.25 (-2.25, 2.78) | -1.41 (-4.02, 1.23) | 0.70 (-1.15, 2.50) | 1.14 (-0.95, 3.10) |

| -0.22 (-2.77, 2.33) | 2.26 (0.10, 4.38) | -0.25 (-2.78, 2.25) | Mixed intervention | -1.66 (-4.78, 1.40) | 0.45 (-2.04, 2.95) | 0.88 (-1.61, 3.32) |

| 1.45 (-1.31, 4.16) | 3.92 (1.72, 6.15) | 1.41 (-1.23, 4.02) | 1.66 (-1.40, 4.78) | OS + NNS | 2.11 (-0.52, 4.72) | 2.53 (-0.06, 5.25) |

| -0.68 (-2.56, 1.19) | 1.80 (0.51, 3.14) | -0.70 (-2.50, 1.15) | -0.45 (-2.95, 2.04) | -2.11 (-4.72, 0.52) | Olfactory stimulation | 0.43 (-1.55, 2.43) |

| -1.10 (-3.22, 1.00) | 1.38 (-0.11, 2.87) | -1.14 (-3.10, 0.95) | -0.88 (-3.32, 1.61) | -2.53 (-5.25, 0.06) | -0.43 (-2.43, 1.55) | Tactile relief |

Oxygen saturation

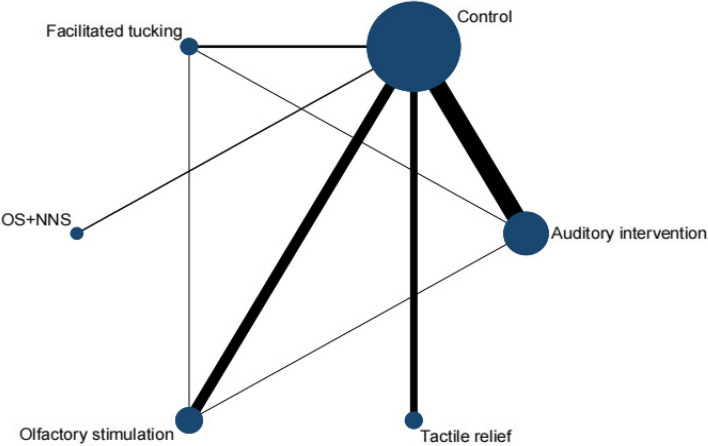

A total of 14 RCTs [32, 33, 38, 39, 41, 43, 47–50, 55, 56, 60, 63] were included in this meta-analysis by oxygen saturation, involving 5 interventions. Olfactory stimulation (3 RCTs), OS + NNS (2 RCTs), facilitated tucking (2 RCTs), auditory intervention (6 RCTs), and tactile relief (3 RCTs) were included. A total of 6 nodes were included in this meta-analysis, with each node representing an intervention or control (Fig. 5). The nodes with more significant interactions were control (16 interactions), auditory intervention (8 interactions), olfactory stimulation (5 interactions), and facilitated tucking (5 interactions). The results of the consistency analysis was shown in Additional file 1: Appendix Table 6. The results of the heterogeneity test indicated a high degree of heterogeneity with an I2 value of 81.5%.

Fig. 5.

Network evidence diagram (oxygen saturation)

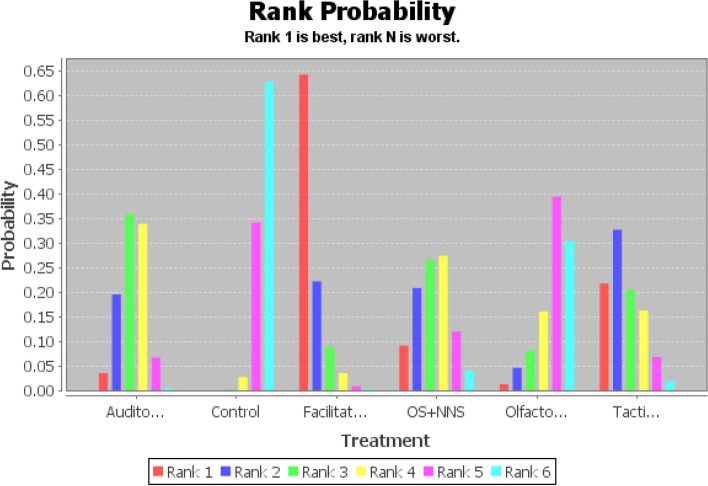

Based on moderate-quality evidence (Additional file 1: Appendix Table 9), facilitated tucking had the greatest SUCRA score, followed by tactile relief, auditory intervention, OS + NNS, olfactory stimulation, and control group (Fig. 6 and Additional file 1: Appendix Table 7). Compared to the control group, facilitated tucking was 1.94 (95% CI: 0.66,3.35, SUCRA score: 0.64) higher, the auditory intervention was 1.04 (95% CI: 0.22,2.04, SUCRA score: 0.36) higher, and the remaining comparisons were not statistically significant (Table 3). Therefore, the complete probability ranking was facilitated tucking (64%) > auditory intervention (36%) > control (63%) (Additional file 1: Appendix Table 7). The stability and credibility of the results were demonstrated in Additional file 1: Appendix Table 8 through the sensitivity analysis.

Fig. 6.

Probability ranking diagram of best interventions (oxygen saturation)

Table 3.

The results of network meta-analysis (consistency model, oxygen saturation)

| Auditory intervention | -1.04 (-2.04, -0.22) | 0.89 (-0.62, 2.32) | 0.00 (-1.66, 1.62) | -0.75 (-2.08, 0.86) | 0.34 (-1.39, 1.91) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.04 (0.22, 2.04) | Control | 1.94 (0.66, 3.35) | 1.04 (-0.24, 2.52) | 0.30 (-0.95, 1.96) | 1.38 (0.00, 2.80) |

| -0.89 (-2.32, 0.62) | -1.94 (-3.35, -0.66) | Facilitated tucking | -0.90 (-2.78, 1.05) | -1.64 (-3.15, 0.15) | -0.57 (-2.54, 1.37) |

| -0.00 (-1.62, 1.66) | -1.04 (-2.52, 0.24) | 0.90 (-1.05, 2.78) | OS + NNS | -0.75 (-2.55, 1.34) | 0.33 (-1.67, 2.23) |

| 0.75 (-0.86, 2.08) | -0.30 (-1.96, 0.95) | 1.64 (-0.15, 3.15) | 0.75 (-1.34, 2.55) | Olfactory stimulation | 1.06(-1.01, 2.91) |

| -0.34 (-1.91, 1.39) | -1.38 (-2.80, -0.00) | 0.57 (-1.37, 2.54) | -0.33 (-2.23, 1.67) | -1.06 (-2.91, 1.01) | Tactile relief |

Heart rate

A total of 14 RCTs [32, 33, 38, 39, 41, 43, 47–50, 55, 56, 60, 63] were included in this meta-analysis by heart rate, involving 5 interventions. Olfactory stimulation (3 RCTs), OS + NNS (2 RCTs), facilitated tucking (2 RCTs), auditory intervention (6 RCTs), and tactile relief (3 RCTs) were included. A total of 6 nodes were included in this meta-analysis, with each node representing an intervention or control (Fig. 7). The nodes with more significant interactions were control (16 interactions), auditory intervention (8 interactions), olfactory stimulation (5 interactions), and facilitated tucking (5 interactions). The results of the consistency analysis was shown in Additional file 1: Appendix Table 10. The results of the heterogeneity test indicated a high degree of heterogeneity with an I2 value of 99.3%.

Fig. 7.

Network evidence diagram (heart rate)

Based on moderate-quality evidence (Additional file 1: Appendix Table 13), OS + NNS had the greatest SUCRA score, followed by control group, olfactory stimulation, auditory intervention, facilitated tucking, and tactile relief (Fig. 8 and Additional file 1: Appendix Table 11). However, this study found that there were no statistical differences between the interventions based on the data in Table 4. Therefore, the probability ranking analysis shown in Additional file 1: Appendix Table 11 was invalid. The stability and credibility of the results were demonstrated in Additional file 1: Appendix Table 12 through the sensitivity analysis.

Fig. 8.

Probability ranking diagram of best interventions (heart rate)

Table 4.

The results of network meta-analysis (consistency model, heart rate)

| Auditory intervention | 6.63 (-1.51, 15.03) | -0.94 (-15.22, 13.49) | 6.86 (-9.77, 23.62) | 1.50 (-11.14, 15.07) | -0.70 (-15.22, 14.39) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -6.63 (-15.03, 1.51) | Control | -7.62 (-20.63, 5.55) | 0.14 (-14.41, 14.89) | -5.08 (-16.46, 6.11) | -7.20 (-19.54, 4.63) |

| 0.94 (-13.49, 15.22) | 7.62 (-5.55, 20.63) | Facilitated tucking | 7.74 (-11.61, 27.44) | 2.45 (-12.94, 18.37) | 0.44 (-17.73, 18.14) |

| -6.86 (-23.62, 9.77) | -0.14 (-14.89, 14.41) | -7.74 (-27.44, 11.61) | OS + NNS | -5.11 (-23.76, 13.10) | -7.39 (-26.57, 11.60) |

| -1.50 (-15.07, 11.14) | 5.08 (-6.11, 16.46) | -2.45 (-18.37, 12.94) | 5.11 (-13.10, 23.76) | Olfactory stimulation | -2.12 (-18.71, 14.29) |

| 0.70 (-14.39, 15.22) | 7.20 (-4.63, 19.54) | -0.44 (-18.14, 17.73) | 7.39 (-11.60, 26.57) | 2.12 (-14.29, 18.71) | Tactile relief |

Discussion

This study conducted a network meta-analysis of 35 RCTs consisting of 2134 preterm infants to compare the efficacy of different interventions for pain relief. The results showed that in addition to tactile relief, interventions such as OS + NNS, facilitated tucking, auditory intervention, olfactory stimulation, and mixed intervention were significantly more effective in reducing pain compared to the control group. Among these interventions, OS + NNS was relatively more effective, while the mixed intervention was relatively less effective. In addition to analyzing the effects of the interventions on pain scores, the study also investigated their effects on oxygen saturation and heart rate. The results showed that only facilitated tucking and auditory intervention had a statistically significant improvement in oxygen saturation compared to the control group. However, none of the interventions exerted a significant effect on heart rate.

Research studies have indicated that multiple acute pain procedures in NICUs can result in “a chronically painful state” for preterm infants [64, 65], which is detrimental to pain recovery, neurodevelopment, and psychosocial health [66]. Non-pharmacological interventions for managing pain have gained significant attention in recent years. However, the effectiveness of these interventions has not yet been clear and remains an area of ongoing research [66, 67]. Based on this, this meta-analysis compared their efficacy and found that OS + NNS, facilitated tucking and auditory intervention were relatively more effective. According to the results of network meta-analysis, this study evaluated the combined intervention of OS + NNS. However, the role of OS + NNS in reducing pain among preterm infants did not reach a consensus. A systematic review [68] investigating the impact of non-pharmacological analgesic interventions during heel prick showed that OS + NNS did not significantly reduce pain scores, oxygen saturation, and heart rate. The difference in results may be due to variations in concentration and dose of sucrose solution used, as has been observed in other studies [69–72]. Subsequent studies can compare varying concentrations and dosages of sucrose solutions to more comprehensively observe their impact on pain levels among preterm infants.

Overall, the role of facilitated tucking in reducing pain scores and improving oxygen saturation was more pronounced. A systematic review [73] of the effects of different body positions on procedural pain in NICUs indicated that facilitating tucking by parents for at least 30 min was optimal for alleviating pain and stabilizing physiological, hormonal, and behavioral responses of the newborns. Notably, this meta-analysis only focused on facilitated tucking and did not include other postural interventions. A recent review [74] found that 7 different modified positions have positive effects on sleep, flexion maintenance, and pain management in preterm infants. This indicates that facilitated tucking is not necessarily the best position to reduce pain, and the efficacy and safety of different positions should be analyzed according to their different physiological conditions.

The third ranked non-pharmacological intervention was auditory intervention, which involves exposing preterm infants to sound stimulation through audio playback of white noise, mother's voice, lullabies, and maternal heart sounds [29, 38, 47, 49, 50, 60, 63]. Recent studies [18, 19] have demonstrated that this intervention has a positive impact on reducing pain levels, increasing comfort, improving physiological indicators, and promoting feeding outcomes among preterm infants. However, a systematic review [75] of 39 studies further differentiated auditory intervention, categorizing music-based interventions into music medicine and music therapy. Music medicine involves using recorded audio to stimulate preterm infants, while music therapy involves the use of live music interventions that are clinically and evidence-based and guided by a therapist. The results indicated that music medicine interventions were linked to pain relief, while music therapy had a beneficial impact on cardiac and respiratory function, as well as weight and eating behaviors. This indicates that the effects of the two auditory interventions are different, and subsequent studies can be discussed in this respect.

While traditional meta-analyses focus on comparing individual or the same category of interventions, this meta-analysis underwent a detailed search to systematically integrate published articles on pain management in preterm infants in English, and used a network meta-analysis to compare the relationship and efficacy between six non-pharmacological interventions. This study is closely relevant to clinical practice and may help medical professionals to adopt more effective interventions to reduce the pain and stress suffered from preterm infants during repeated painful procedures. In addition, this study recommends that clinical practitioners adopt a systematic, specialized, and multidisciplinary model for managing pain in preterm infants, paying attention to the combined effects of non-pharmacological interventions and their possible shortcomings in implementation.

Although this meta-analysis has provided some insights, it is crucial to recognize the limitations of this study. One of the major limitations was the high level of heterogeneity, which may be related to the differences in non-pharmacological interventions, the setting in which preterm infants were treated, variations in painful procedures, and the sample sizes used in the studies. Another was the publication bias suggested by funnel plots (Additional file 1: Appendix Figs. 1, 2 and 3), which may be relevant to the inclusion of several studies with poor study design or small scale in this meta-analysis. To increase the validity of these findings, it is necessary to conduct more high-quality studies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study found that non-pharmacological interventions had different levels of efficacy in reducing pain scores and improving oxygen saturation, but no impact on heart rate was observed. Specifically, OS + NNS was found to be the relatively more effective intervention in reducing pain for preterm infants, while facilitated tucking was the relatively more effective in improving oxygen saturation. In addition, we hope for the development of more non-pharmacological interventions to ease the pain experienced by preterm infants during painful procedures, and we also aspire that our study can offer some support to clinical practices.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

None.

Authors’ contributions

Yuwei Weng wrote the main manuscript text. Yuwei Weng and Jie Zhang prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8, Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4, and the supplementary material. Zhifang Chen strictly supervised the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Research Project of Nantong Municipal Health Commission (MS12021040).

Availability of data and materials

All data used in this review are derived from published studies.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Carbajal R, Rousset A, Danan C, et al. Epidemiology and treatment of painful procedures in neonates in intensive care units[J] JAMA. 2008;300(1):60–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Field T. Preterm newborn pain research review[J] Infant Behav Dev. 2017;49:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brummelte S, Grunau RE, Zaidman-Zait A, et al. Cortisol levels in relation to maternal interaction and child internalizing behavior in preterm and full-term children at 18 months corrected age[J] Dev Psychobiol. 2011;53(2):184–195. doi: 10.1002/dev.20511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cong X, Wu J, Vittner D, et al. The impact of cumulative pain/stress on neurobehavioral development of preterm infants in the NICU[J] Early Hum Dev. 2017;108:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeong IS, Park SM, Lee JM, et al. Perceptions on pain management among Korean nurses in neonatal intensive care units[J] Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2014;8(4):261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyololo OM, Stevens B, Gastaldo D, et al. Procedural pain in neonatal units in Kenya[J] Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99(6):F464–F467. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyololo OM, Stevens BJ, Songok J. Procedural pain in hospitalized neonates in Kenya[J] J Pediatr Nurs. 2021;58:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston C, Barrington KJ, Taddio A, et al. Pain in Canadian NICUs: have we improved over the past 12 years?[J] Clin J Pain. 2011;27(3):225–232. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181fe14cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mcpherson C, Grunau RE. Neonatal pain control and neurologic effects of anesthetics and sedatives in preterm infants[J] Clin Perinatol. 2014;41(1):209–227. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim Y, Godambe S. Prevention and management of procedural pain in the neonate: an update, American Academy of Pediatrics, 2016[J] Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2017;102(5):254–256. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai Q, Luo W, Zhou Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of non-pharmacological interventions for endotracheal suctioning pain in preterm infants: a systematic review[J] Nurs Open. 2023;10(2):424–434. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeller B, Giebe J. Pain in the neonate: focus on nonpharmacologic interventions[J] Neonatal Netw. 2014;33(6):336–340. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.33.6.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Çamur Z, Erdoğan Ç. The effects of breastfeeding and breast milk taste or smell on mitigating painful procedures in newborns: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials[J] Breastfeed Med. 2022;17(10):793–804. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2022.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Clifford-Faugere G, Lavallée A, Khadra C, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of olfactive stimulation interventions to manage procedural pain in preterm and full-term neonates[J] Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;110:103697. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomes Neto M, Da Silva LIA, Araujo A, et al. The effect of facilitated tucking position during painful procedure in pain management of preterm infants in neonatal intensive care unit: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J] Eur J Pediatr. 2020;179(5):699–709. doi: 10.1007/s00431-020-03640-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatfield LA, Murphy N, Karp K, et al. A Systematic review of behavioral and environmental interventions for procedural pain management in preterm infants[J] J Pediatr Nurs. 2019;44:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Q, Tan X, Li X, et al. Efficacy and safety of combined oral sucrose and nonnutritive sucking in pain management for infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J] PLoS ONE. 2022;17(5):e0268033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yue W, Han X, Luo J, et al. Effect of music therapy on preterm infants in neonatal intensive care unit: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials[J] J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(2):635–652. doi: 10.1111/jan.14630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Zhang J, Yang C, et al. Effects of maternal sound stimulation on preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J] Int J Nurs Pract. 2023;29(2):e13039. doi: 10.1111/ijn.13039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo W, Liu X, Zhou X, et al. Efficacy and safety of combined nonpharmacological interventions for repeated procedural pain in preterm neonates: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials[J] Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;102:103471. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement[J] PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials[J] BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nikolakopoulou A, Higgins JPT, Papakonstantinou T, et al. CINeMA: an approach for assessing confidence in the results of a network meta-analysis[J] PLoS Med. 2020;17(4):e1003082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevens B, Johnston C, Petryshen P, et al. Premature infant pain profile: development and initial validation[J] Clin J Pain. 1996;12(1):13–22. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevens BJ, Gibbins S, Yamada J, et al. The premature infant pain profile-revised (PIPP-R): initial validation and feasibility[J] Clin J Pain. 2014;30(3):238–243. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182906aed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, et al. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis[J] Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):97–111. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses[J] BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shim SR, Kim SJ, Lee J, et al. Network meta-analysis: application and practice using R software[J] Epidemiol Health. 2019;41:e2019013. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2019013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alemdar DK. Effect of recorded maternal voice, breast milk odor, and incubator cover on pain and comfort during peripheral cannulation in preterm infants[J] Appl Nurs Res. 2018;40:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alemdar DK, Tüfekci FG. Effects of smelling amniotic fluid on preterm infant’s pain and stress during peripheral cannulation: a randomized controlled trial[J] Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2020;17(3):e12317. doi: 10.1111/jjns.12317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alinejad-Naeini M, Mohagheghi P, Peyrovi H, et al. The effect of facilitated tucking during endotracheal suctioning on procedural pain in preterm neonates: a randomized controlled crossover study[J] Glob J Health Sci. 2014;6(4):278–284. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v6n4p278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Apaydin Cirik V, Efe E. The effect of expressed breast milk, swaddling and facilitated tucking methods in reducing the pain caused by orogastric tube insertion in preterm infants: a randomized controlled trial[J] Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;104:103532. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asmerom Y, Slater L, Boskovic DS, et al. Oral sucrose for heel lance increases adenosine triphosphate use and oxidative stress in preterm neonates[J] J Pediatr. 2013;163(1):29–35.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.12.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De BaudessonChanville A, Brevaut-Malaty V, Garbi A, et al. Analgesic effect of maternal human milk odor on premature neonates: a randomized controlled Trial[J] J Hum Lact. 2017;33(2):300–308. doi: 10.1177/0890334417693225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cong X, Ludington-Hoe SM, Walsh S. Randomized crossover trial of kangaroo care to reduce biobehavioral pain responses in preterm infants: a pilot study[J] Biol Res Nurs. 2011;13(2):204–216. doi: 10.1177/1099800410385839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davari S, Borimnejad L, Khosravi S, et al. The effect of the facilitated tucking position on pain intensity during heel stick blood sampling in premature infants: a surprising result[J] J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32(20):3427–3430. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1465550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dilli D, İlarslan NE, Kabataş EU, et al. Oral sucrose and non-nutritive sucking goes some way to reducing pain during retinopathy of prematurity eye examinations[J] Acta Paediatr. 2014;103(2):e76–e79. doi: 10.1111/apa.12454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Döra Ö, Büyük ET. Effect of white noise and lullabies on pain and vital signs in invasive interventions applied to premature babies[J] Pain Manag Nurs. 2021;22(6):724–729. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2021.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dur Ş, Çağlar S, Yıldız NU, et al. The effect of Yakson and Gentle Human Touch methods on pain and physiological parameters in preterm infants during heel lancing[J] Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2020;61:102886. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fatollahzade M, Parvizi S, Kashaki M, et al. The effect of gentle human touch during endotracheal suctioning on procedural pain response in preterm infant admitted to neonatal intensive care units: a randomized controlled crossover study[J] J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(7):1370–1376. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1755649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao H, Li M, Gao H, et al. Effect of non-nutritive sucking and sucrose alone and in combination for repeated procedural pain in preterm infants: a randomized controlled trial[J] Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;83:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hill S, Engle S, Jorgensen J, et al. Effects of facilitated tucking during routine care of infants born preterm[J] Pediatr Phys Ther. 2005;17(2):158–163. doi: 10.1097/01.PEP.0000163097.38957.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jain S, Kumar P, Mcmillan DD. Prior leg massage decreases pain responses to heel stick in preterm babies[J] J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42(9):505–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jebreili M, Neshat H, Seyyedrasouli A, et al. Comparison of breastmilk odor and vanilla odor on mitigating premature infants’ response to pain during and after venipuncture[J] Breastfeed Med. 2015;10(7):362–365. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2015.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnston C, Campbell-Yeo M, Rich B, et al. Therapeutic touch is not therapeutic for procedural pain in very preterm neonates: a randomized trial[J] Clin J Pain. 2013;29(9):824–829. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182757650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnston CC, Filion F, Campbell-Yeo M, et al. Kangaroo mother care diminishes pain from heel lance in very preterm neonates: a crossover trial[J] BMC Pediatr. 2008;8:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kahraman A, Gümüş M, Akar M, et al. The effects of auditory interventions on pain and comfort in premature newborns in the neonatal intensive care unit; a randomised controlled trial[J] Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2020;61:102904. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Küçük Alemdar D, Kardaş ÖF. Effects of having preterm infants smell amniotic fluid, mother’s milk, and mother’s odor during heel stick procedure on pain, physiological parameters, and crying duration[J] Breastfeed Med. 2017;12:297–304. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2017.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kucukoglu S, Aytekin A, Celebioglu A, et al. Effect of white noise in relieving vaccination pain in premature infants[J] Pain Manag Nurs. 2016;17(6):392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kurdahi Badr L, Demerjian T, Daaboul T, et al. Preterm infants exhibited less pain during a heel stick when they were played the same music their mothers listened to during pregnancy[J] Acta Paediatr. 2017;106(3):438–445. doi: 10.1111/apa.13666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liaw JJ, Yang L, Katherine Wang KW, et al. Non-nutritive sucking and facilitated tucking relieve preterm infant pain during heel-stick procedures: a prospective, randomised controlled crossover trial[J] Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(3):300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mitchell AJ, Yates CC, Williams DK, et al. Does daily kangaroo care provide sustained pain and stress relief in preterm infants?[J] J Neonatal Perinatal Med. 2013;6(1):45–52. doi: 10.3233/NPM-1364212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perroteau A, Nanquette MC, Rousseau A, et al. Efficacy of facilitated tucking combined with non-nutritive sucking on very preterm infants’ pain during the heel-stick procedure: a randomized controlled trial[J] Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;86:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qiu J, Jiang YF, Li F, et al. Effect of combined music and touch intervention on pain response and β-endorphin and cortisol concentrations in late preterm infants[J] BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12887-016-0755-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rad ZA, Aziznejadroshan P, Amiri AS, et al. The effect of inhaling mother’s breast milk odor on the behavioral responses to pain caused by hepatitis B vaccine in preterm infants: a randomized clinical trial[J] BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s12887-021-02519-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sezer Efe Y, Erdem E, Caner N, et al. The effect of gentle human touch on pain, comfort and physiological parameters in preterm infants during heel lancing[J] Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2022;48:101622. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2022.101622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shukla VV, Bansal S, Nimbalkar A, et al. Pain control interventions in preterm neonates: a randomized controlled trial[J] Indian Pediatr. 2018;55(4):292–296. doi: 10.1007/s13312-018-1270-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Srivastava G, Garg A, Chhavi N, et al. Effect of kangaroo mother care on pain during orogastric tube insertion in low-birthweight newborns: an open label, randomised trial[J] J Paediatr Child Health. 2022;58(12):2248–2253. doi: 10.1111/jpc.16212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sundaram B, Shrivastava S, Pandian JS, et al. Facilitated tucking on pain in pre-term newborns during neonatal intensive care: a single blinded randomized controlled cross-over pilot trial[J] J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2013;6(1):19–27. doi: 10.3233/PRM-130233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taplak A, Bayat M. Comparison the effect of breast milk smell, white noise and facilitated tucking applied to Turkish preterm infants during endotracheal suctioning on pain and physiological parameters[J] J Pediatr Nurs. 2021;56:e19–e26. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Usta C, Tanyeri-Bayraktar B, Bayraktar S. Pain control with lavender oil in premature infants: a double-blind randomized controlled study[J] J Altern Complement Med. 2021;27(2):136–141. doi: 10.1089/acm.2020.0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ward-Larson C, Horn RA, Gosnell F. The efficacy of facilitated tucking for relieving procedural pain of endotracheal suctioning in very low birthweight infants[J] MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2004;29(3):151–156. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200405000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu WC, Chiang MC, Lin KC, et al. Effects of maternal voice on pain and mother-Infant bonding in premature infants in Taiwan: a randomized controlled trial[J] J Pediatr Nurs. 2022;63:e136–e142. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2021.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pillai Riddell RR, Stevens BJ, Mckeever P, et al. Chronic pain in hospitalized infants: health professionals’ perspectives[J] J Pain. 2009;10(12):1217–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dilorenzo M, Pillai Riddell R, Holsti L. Beyond acute pain: understanding chronic pain in infancy[J] Children (Basel). 2016;3(4):26. doi: 10.3390/children3040026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shiff I, Bucsea O, Pillai RR. Psychosocial and neurobiological vulnerabilities of the hospitalized preterm infant and relevant non-pharmacological pain mitigation strategies[J] Front Pediatr. 2021;9:568755. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.568755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mangat AK, Oei JL, Chen K, et al. A review of non-pharmacological treatments for pain management in newborn infants[J] Children (Basel) 2018;5(10):130. doi: 10.3390/children5100130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.García-Valdivieso I, Yáñez-Araque B, Moncunill-Martínez E, et al. Effect of non-pharmacological methods in the reduction of neonatal pain: systematic review and meta-analysis[J] Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):3226. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20043226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stevens B, Yamada J, Campbell-Yeo M, et al. The minimally effective dose of sucrose for procedural pain relief in neonates: a randomized controlled trial[J] BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s12887-018-1026-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tanyeri-Bayraktar B, Bayraktar S, Hepokur M, et al. Comparison of two different doses of sucrose in pain relief[J] Pediatr Int. 2019;61(8):797–801. doi: 10.1111/ped.13914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kristoffersen L, Malahleha M, Duze Z, et al. Randomised controlled trial showed that neonates received better pain relief from a higher dose of sucrose during venepuncture[J] Acta Paediatr. 2018;107(12):2071–2078. doi: 10.1111/apa.14567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kumari S, Datta V, Rehan H. Comparison of the efficacy of oral 25% glucose with oral 24% sucrose for pain relief during heel lance in preterm neonates: a double blind randomized controlled trial[J] J Trop Pediatr. 2017;63(1):30–35. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmw045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Francisco A, Montemezzo D, Ribeiro S, et al. Positioning effects for procedural pain relief in NICU: systematic review[J] Pain Manag Nurs. 2021;22(2):121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang L, Fu H, Zhang L. A systematic review of improved positions and supporting devices for premature infants in the NICU[J] Heliyon. 2023;9(3):e14388. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Costa VS, Bündchen DC, Sousa H, et al. Clinical benefits of music-based interventions on preterm infants’ health: a systematic review of randomised trials[J] Acta Paediatr. 2022;111(3):478–489. doi: 10.1111/apa.16222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this review are derived from published studies.