Abstract

Objective:

Men's heavy drinking behaviors are related to their engagement in sexual aggression and may be amplified by other factors, such as precarious masculinity (i.e., perceiving masculinity as tenuous in nature). Yet, researchers’ understanding of how alcohol consumption, in combination with precarious masculinity, may increase risk of sexual aggression is lacking. The goal of this study was to assess if precarious masculinity moderated the relationship between men's heavy drinking and their sexual aggression.

Method:

Young adult men (958 men, M age = 21.1 years, SD = 3.1) completed a web-administered questionnaire assessing sexual aggression, heavy drinking, and precarious masculinity.

Results:

We ran a logistic regression examining the association between heavy drinking, precarious masculinity, and their interactive effect on men's engagement in sexual aggression. Heavy drinking (odds ratio [OR] = 1.17) and precarious masculinity (OR = 1.73) were independently and positively associated with men's sexual aggression; however, the interaction was not significant.

Conclusions:

In line with prior research, men's heavy drinking behaviors continue to be positively associated with sexual aggression. Building on masculinity literature, men viewing their masculinity as precarious and vulnerable appears to be associated with sexual aggression, potentially because engaging in sexual aggression can offset men's masculinity insecurities. Collectively, results suggest that both alcohol consumption and masculinity should be targeted in sexual assault prevention programs.

Sexual Aggression is defined as nonconsensual sexual acts in which perpetrators use coercion, force, or other means (e.g., purposeful intoxication) to obtain sex from victims (Cantor et al., 2017). There is strong evidence documenting the relationship between alcohol consumption and sexual aggression (Abbey, 2002; Abbey et al., 2014; Davis, 2010; Testa, 2002). Yet, research examining factors that may moderate this relationship is more limited (Abbey et al., 2014; Benbouriche et al., 2019; Giancola et al., 2011; Kirwan, Lanni, et al., 2019; Norona et al., 2021). This is somewhat surprising because men's alcohol consumption is thought to be related to different personality characteristics commonly associated with sexual aggression (Abbey et al., 2011; Norona et al., 2021; Tharp et al., 2013) such as masculinity (Davis et al., 2015; Gallagher & Parrott, 2011; Leone et al., 2022; Norris et al., 1999). As such, the goal of this study was to assess the relationship between heavy drinking and precarious masculinity (i.e., perceiving masculinity as tenuous in nature) on men's likelihood to have been sexually aggressive.

Heavy drinking and sexual aggression

Heavy drinking is defined as consuming five or more drinks in one sitting (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA], 2020) and is positively related to men's engagement in sexual aggression (Abbey, 2011; Crane et al., 2016; Kirwan, Parkhill, et al., 2019; Shorey et al., 2014, 2015). The relationship between men's heavy drinking and sexual aggression may be explained by alcohol myopia theory (AMT; Steele & Josephs, 1990). AMT posits that alcohol consumption impairs in-the-moment higher order cognitive functioning, which creates disruptions in people's ability to plan and manage their response inhibition. Intoxicated individuals also tend to focus on the most salient and provocative cues in a situation rather than distal or less provocative cues (Abbey, 2002). Given that sexual aggression can begin with consensual sexual activity (Flack et al., 2016), men's alcohol consumption may cause them to (a) focus more on their desire for sex and initial consent cues they may have interpreted from their partner, (b) focus less on distal cues, particularly those signaling refusal, and (c) decrease their response inhibition, resulting in them using aggressive tactics to obtain sex without their partner's consent. In addition, the relationship between heavy drinking and men's sexual aggression may be explained by characteristics associated with both behaviors, such as alcohol expectancies, impulsivity, or masculinity (Abbey et al., 2022; Kirwan et al., 2023; Testa & Cleveland, 2017).

Precarious masculinity and sexual aggression

Alcohol consumption facilitates aggression to a greater extent among those who have risk factors for aggressive behaviors (Gallagher & Parrott, 2016; Tharp et al., 2013), such as precarious masculinity. Precarious masculinity is men's cognitive appraisals of their masculinity as tenuous in nature (Bosson et al., 2009; Vandello et al., 2008). According to precarious masculinity, because men's masculinity is vulnerable, men may feel threatened or challenged in gender-relevant situations (e.g., approaching someone for sex), which creates gender role stress and results in a defensive response or need to reaffirm their masculinity (Gallagher & Parrott, 2016; Smith et al., 2015; Vandello et al., 2008). Men may engage in traditional heterosexual masculine behaviors such as drinking alcohol to affirm masculinity. Specifically, compared with men who did not have their masculinity threatened, those who did consumed more alcohol (Fugitt & Ham, 2018). Further, men high in precarious masculinity and who experience stress associated with their masculinity may be at greater risk to sexually aggress (Leone et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2015) because sexual aggression provides a clear example of “manhood” (i.e., having sex with women; Seabrook et al., 2018).

Heavy drinking, precarious masculinity, and sexual aggression

Men's heavy drinking is positively associated with their engagement in sexual aggression (Crane et al., 2016; Kirwan, Parkhill, et al., 2019). However, the extent to which precarious masculinity influences this effect is less well understood (Leone & Parrott, 2018; Smith et al., 2015). The reviewed literature indicates that alcohol is associated with aggression via heightened focus on salient, aggression-promoting cues. The need to reaffirm one's masculinity is highly salient to men who are high in precarious masculinity; as such, heavy alcohol use should heighten the focus on the precariousness of their masculinity and the need to reaffirm it for these men. Thus, the positive association between heavy alcohol use and sexual aggression should be strongest among men who endorse high, relative to low, precarious masculinity.

Current study

The goal of this study was to assess how men's heavy drinking and precarious masculinity relate to their engagement in sexual aggression. We hypothesized that higher levels of heavy drinking would increase the likelihood of sexual aggression perpetration to a greater extent in men who reported high, relative to low, levels of precarious masculinity.

Method

Participants

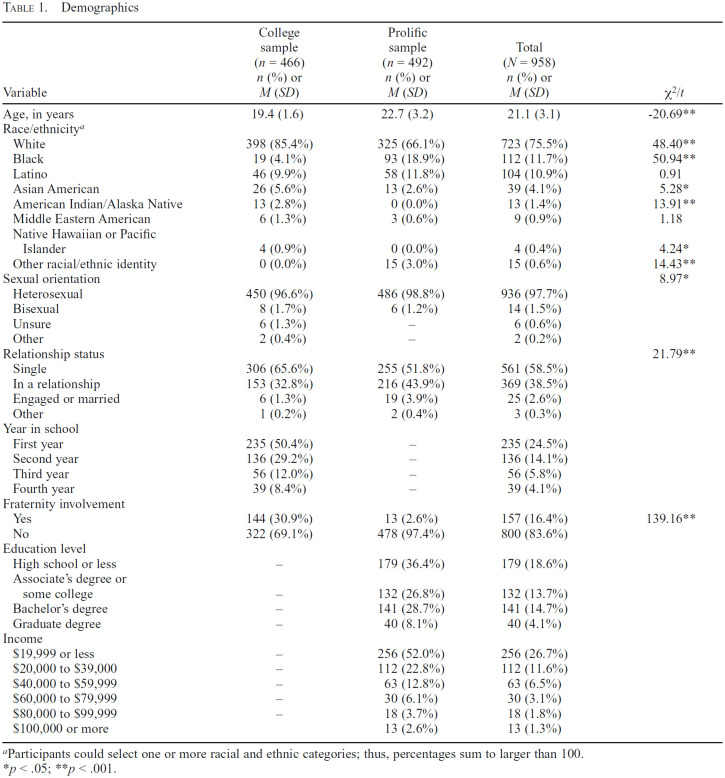

Young adult men (18–30 years old) were recruited through the University of Arkansas's Psychology Department's SONA System (n = 552) and Prolific—a sample aggregator (n = 521). We removed 114 people for failing reading checks, not completing measures, or not being attracted to women. The total analytical sample included was 958 men. Participants predominantly identified as White, and most men identified as heterosexual or bisexual and were single at the time of the study. Educational background and experience were diverse across the groups (Table 1).1

Table 1.

Demographics

| Variable | College sample (n = 466) n (%) or M (SD) | Prolific sample (n = 492) n (%) or M (SD) | Total (N = 958) n (%) or M (SD) | χ2/t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, in years | 19.4(1.6) | 22.7 (3.2) | 21.1 (3.1) | -20.69** |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||

| White | 398 (85.4%) | 325 (66.1%) | 723 (75.5%) | 48.40** |

| Black | 19 (4.1%) | 93 (18.9%) | 112 (11.7%) | 50.94** |

| Latino | 46 (9.9%) | 58 (11.8%) | 104 (10.9%) | 0.91 |

| Asian American | 26 (5.6%) | 13 (2.6%) | 39 (4.1%) | 5.28* |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 13 (2.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (1.4%) | 13.91** |

| Middle Eastern American | 6 (1.3%) | 3 (0.6%) | 9 (0.9%) | 1.18 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific | ||||

| Islander | 4 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (0.4%) | 4.24* |

| Other racial/ethnic identity | 0 (0.0%) | 15 (3.0%) | 15 (0.6%) | 14.43** |

| Sexual orientation | 8.97* | |||

| Heterosexual | 450 (96.6%) | 486 (98.8%) | 936 (97.7%) | |

| Bisexual | 8 (1.7%) | 6 (1.2%) | 14(1.5%) | |

| Unsure | 6 (1.3%) | - | 6 (0.6%) | |

| Other | 2 (0.4%) | - | 2 (0.2%) | |

| Relationship status | 21.79** | |||

| Single | 306 (65.6%) | 255 (51.8%) | 561 (58.5%) | |

| In a relationship | 153 (32.8%) | 216 (43.9%) | 369 (38.5%) | |

| Engaged or married | 6 (1.3%) | 19 (3.9%) | 25 (2.6%) | |

| Other | 1 (0.2%) | 2 (0.4%) | 3 (0.3%) | |

| Year in school | ||||

| First year | 235 (50.4%) | - | 235 (24.5%) | |

| Second year | 136 (29.2%) | - | 136 (14.1%) | |

| Third year | 56 (12.0%) | - | 56 (5.8%) | |

| Fourth year | 39 (8.4%) | - | 39 (4.1%) | |

| Fraternity involvement | ||||

| Yes | 144 (30.9%) | 13 (2.6%) | 157 (16.4%) | 139.16** |

| No | 322 (69.1%) | 478 (97.4%) | 800 (83.6%) | |

| Education level | ||||

| High school or less | - | 179 (36.4%) | 179 (18.6%) | |

| Associate's degree or | ||||

| some college | - | 132 (26.8%) | 132 (13.7%) | |

| Bachelor's degree | - | 141 (28.7%) | 141 (14.7%) | |

| Graduate degree | - | 40 (8.1%) | 40 (4.1%) | |

| Income | ||||

| $19,999 or less | - | 256 (52.0%) | 256 (26.7%) | |

| $20,000 to $39,000 | - | 112 (22.8%) | 112 (11.6%) | |

| $40,000 to $59,999 | - | 63 (12.8%) | 63 (6.5%) | |

| $60,000 to $79,999 | - | 30 (6.1%) | 30 (3.1%) | |

| $80,000 to $99,999 | - | 18 (3.7%) | 18 (1.8%) | |

| $100,000 or more | 13 (2.6%) | 13 (1.3%) |

aParticipants could select one or more racial and ethnic categories; thus, percentages sum to larger than 100.

p < .05;

p < .001.

Procedure

Men reviewed an informed consent and completed a battery of assessments focused on masculinity, drinking behaviors, and sexual aggression. Men who completed the study through the SONA system received course credit. Men recruited through Prolific earned credits that were redeemed for cash value.

Measures

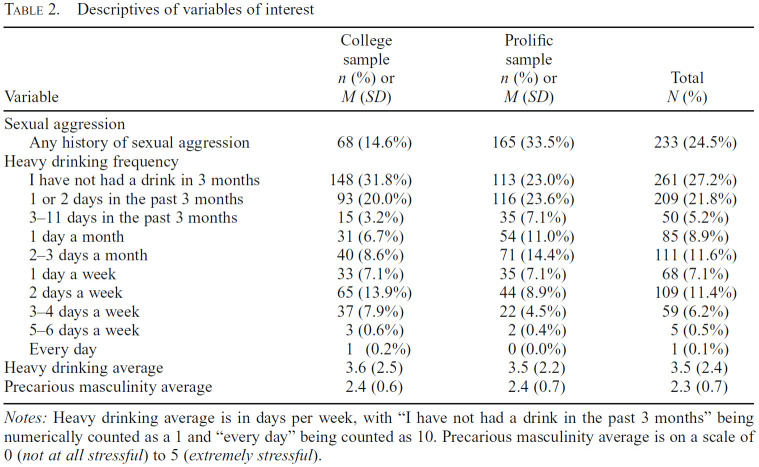

Heavy drinking. Heavy drinking was assessed using an adapted and modified version of NIAAA's (2022) recommended item, “During the past 32 months, how often did you have 5 or more drinks containing any kind of alcohol within a 2-hour period?” Response options are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptives of variables of interest

| Variable | College sample n (%) or M (SD) | College sample n (%) or M (SD) | Total N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual aggression | |||

| Any history of sexual aggression | 68(14.6%) | 165 (33.5%) | 233 (24.5%) |

| Heavy drinking frequency | |||

| I have not had a drink in 3 months | 148 (31.8%) | 113.(23.0%) | 261.(27.2%) |

| 1 or 2 days in the past 3 months | 93 (20.0%) | 116(23.6%) | 209 (21.8%) |

| 3-11 days in the past 3 months | 15(3.2%) | 35.(7.1%) | 50.(5.2%) |

| 1 day a month | 31(6.7%) | 54(11.0%) | 85 (8.9%) |

| 2-3 days a month | 40(8.6%) | 71.(14.4%) | 111.(11.6%) |

| 1 day a week | 33 (7.1%) | 35 (7.1%) | 68 (7.1%) |

| 2 days a week | 65(13.9%) | 44.(8.9%) | 109.(11.4%) |

| 3-4 days a week | 37 (7.9%) | 22 (4.5%) | 59.(6.2%) |

| 5-6 days a week | 3 (0.6%) | 2.(0.4%) | 5.(0.5%) |

| Every day | 1 (0.2%) | 0(0.0%) | 1.(0.1%) |

| Heavy drinking average | 3.6 (2.5) | 3.5 (2.2) | 3.5 (2.4) |

| Precarious masculinity average | 2.4 (0.6) | 2.4 (0.7) | 2.3 (0.7) |

Notes: Heavy drinking average is in days per week, with “I have not had a drink in the past 3 months” being numerically counted as a 1 and “every day” being counted as 10. Precarious masculinity average is on a scale of 0 (not at all stressful) to 5 (extremely stressful).

Precarious masculinity. Men's tendency to cognitively appraise situations that involve traditional male gender norms as stressful was assessed using the Abbreviated Masculine Gender Role Stress Scale (AMGRS; Swartout et al., 2015).

The AMGRS includes 15 items on a scale from 0 (not at all stressful) to 5 (extremely stressful), with higher scores reflecting greater endorsement of viewing masculinity as stressful and representative of precarious masculinity. Examples include “Being perceived as gay” and “Losing in a sports competition.” The AMGRS had high internal consistency in this study (α = .870) and has shown similar reliability in other studies with similar samples (Leone et al., 2022; Swartout et al., 2015).

Sexual aggression. Men were presented a list of 53 different strategies they used to obtain sex (oral, vaginal, or anal) from a nonconsenting woman in their lifetime (Sexual Strategies Scale–Revised; Strang et al., 2013). The strategies included varying levels of sexual aggression, as well as “fillers” that described consensual behavior. An example item is, “After she initially says no to sex, acting angry, upset, or withdrawn until she gives into sex.” Sexual aggression was dichotomized into ever engaging in sexual aggression (1) or not (0).

Analysis plan

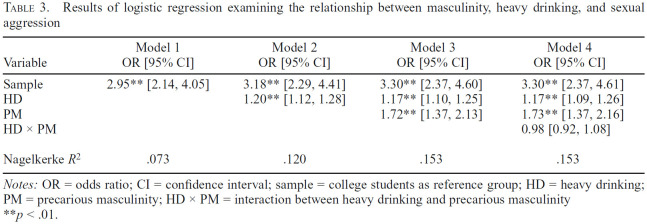

First, using chi-square and independent sample t test, we assessed if heavy drinking, precarious masculinity, and sexual aggression differed between the two samples. Second, to examine the relationship between heavy drinking, precarious masculinity, and sexual aggression we ran a logistic regression. Heavy drinking was mean centered and entered on Step 1, precarious masculinity was mean centered and entered on Step 2, and the interaction of heavy drinking and precarious masculinity was entered on Step 3.

Results

Rates of sexual aggression and alcohol consumption

Across our study, 24.3% (n = 233) of men reported a history of sexual aggression (Table 2). Men recruited through Prolific had a greater likelihood of reporting a history of sexual aggression compared with the sample of college men: χ2 (1, 958) = 46.66, p < .001, Cramér's V = .221. A quarter of the sample (25.3%, n = 242) reported heavy drinking at least once per week and men reported experiencing slight levels of stress associated with precarious masculinity (M = 2.4, SD = 0.69; Table 2). Heavy drinking and precarious masculinity were positively correlated (r = .16, p < .001). We found no difference between the samples on heavy drinking (p = .513) or precarious masculinity (p = .411). Because the samples differed in their sexual aggression history, we included sample type as an independent variable in our final model.

Multivariate model

In Step 1, we entered the sample type. Men recruited through Prolific had a greater likelihood to report a history of sexual aggression than men recruited from the college campus. In Step 2, we entered heavy drinking and found that as men's frequency of heavy drinking increased, so did their odds of engaging in sexual aggression; sample type remained significant at Step 2. In Step 3, we included precarious masculinity and found that as men's precarious masculinity increased, their odds of being sexually aggressive increased; sample type and heavy drinking remained significant at Step 3. Finally, at Step 4, we entered the interaction between heavy drinking and precarious masculinity. We did not find a significant interaction effect; however, the main effects of sample type, heavy drinking, and precarious masculinity remained (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of logistic regression examining the relationship between masculinity, heavy drinking, and sexual aggression

| Variable | Model 1 OR [95% CI] | Model 2 OR [95% CI] | Model 3 OR [95% CI] | Model 4 OR [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | 2.95** [2.14, 4.05] | 3.18** [2.29, 4.41] | 3.30** [2.37, 4.60] | 3.30** [2.37, 4.61] |

| HD | 1.20** [1.12, 1.28] | 1.17** [1.10, 1.25] | 1.17** [1.09, 1.26] | |

| PM | 1.72** [1.37, 2.13] | 1.73** [1.37, 2.16] | ||

| HD X PM | 0.98 [0.92, 1.08] | |||

| Nagelkerke R2 | .073 | .120 | .153 | .153 |

Notes: OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; sample = college students as reference group; HD = heavy drinking; PM = precarious masculinity; HD × PM = interaction between heavy drinking and precarious masculinity

p < .01.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to assess the relationship between heavy drinking, precarious masculinity, and men's sexual aggression. Our results suggest that heavy drinking frequency and precarious masculinity exert independent effects on sexual aggression; however, an interactive effect was not present. Men's heavy drinking frequency may relate to their engagement in sexual aggression because men may be experiencing the cognitive deficits brought on by alcohol more regularly (Abbey, 2002), which may cause them to focus on their desire for sexual activity and block attention to inhibitory cues (George et al., 2000). Consequently, when the perceived opportunity for sexual activity presents itself, men who are intoxicated and focused on obtaining sex may not focus on cues that disconfirm their beliefs (i.e., a refusal).

Second, men who engage in heavy drinking more frequently may also visit bars or parties more frequently— such settings can facilitate sexual aggression by providing men access to potential victims (Testa & Cleveland, 2016). Relating these findings to our study, heavy drinking may increase men's likelihood to be sexually aggressive because when men drink heavily, they are more likely to be in environments that facilitate their aggressive behaviors. Moving forward, researchers may consider measuring men's heavy drinking behaviors and their attendance in different drinking environments to assess both constructs’ relationship with sexual aggression.

Precarious masculinity was also significantly associated with sexual aggression, potentially because sexual aggression may function to attenuate men's insecurities about masculinity (Cowan & Mills, 2004; Gallagher & Parrott, 2011) and men's need to address those insecurities (Moore & Stuart, 2004). In line with our findings, sexual aggression may be an effective masculine behavior to reestablish masculinity because sexual aggression is a clear example of what it means to be a “man” (Seabrook et al., 2018). In fact, men who perceived less sexual interest from a sexual partner reported using more verbal persuasion and physical force against her (Testa et al., 2019). Men may have used these sexually aggressive tactics against a woman because they perceived her lack of interest as a challenge to their masculinity.

We did not find a relationship between heavy drinking and precarious masculinity potentially because precarious masculinity theory suggests that aggression is more likely to occur when men view their masculinity as precarious and those cognitions are activated via a stressful gender-relevant situation (Vandello et al., 2008). In addition, if intoxicated during this stressful gender–relevant situation—AMT (Steele & Josephs, 1990) would suggest that men may become myopically focused on their precarious masculinity and reaffirming it—potentially through sexual aggression. Therefore, to assess how alcohol consumption and precarious masculinity increase the risk of sexual aggression and test this theoretical connection, researchers may need to use experimental or laboratory methods that challenge masculinity and isolate the pharmacological effects of alcohol to assess how these two constructs, in the moment, increase the risk of sexual aggression.

Limitations and future directions

First, our data include convenience samples collected via a psychology pool at one university and a sample aggregator. In addition, our samples primarily comprised men who identified as White. Continued efforts are needed to examine sexual aggression and risk factors among diverse groups. Second, our study is focused on men who aggress against women; however, there is a need to examine sexual aggression rates among sexual and gender minority people and associated risk factors. Sexual violence research with sexual and gender minority people is particularly needed as this group experiences comparable, if not elevated, rates of sexual violence and there is less research examining how alcohol or masculinity relates to sexual and gender minorities’ experience of sexual violence (Parrott et al., 2023). Third, our findings are cross-sectional and correlational, creating concerns with recall biases and temporal associations. Given time differences between our variables (drinking in the past 3 months and lifetime sexual aggression), our findings should be taken with caution. Our findings should be complemented by more advanced methodologies such as alcohol administration studies that could examine the acute causal effects of alcohol intoxication and threats to masculinity on men's risk of sexual aggression (Leone & Parrott, 2018). Longitudinal studies would also be beneficial to detect temporal effects of alcohol use and masculinity on men's likelihood to be sexually aggressive to complement our correlational findings.

Implications

We found that heavy drinking and precarious masculinity were associated with men's sexual aggression. Despite alcohol consumption being consistently associated with sexual aggression, alcohol is rarely a focus in sexual assault interventions (DeGue et al., 2014; Denhard et al., 2020). Given the shared relationship between alcohol and sexual aggression, developing integrative interventions for both behaviors is warranted. Within these integrated programs, interventionalists should use effective tools that help reduce drinking behaviors (e.g., motivational interviewing, social norms approaches; Gilmore et al., 2015; Morean et al., 2021; Orchowski et al., 2018). Interventionalists should also be working to challenge maladaptive norms surrounding alcohol environments (e.g., bars/parties) that may normalize and condone men's heavy drinking and sexual aggression.

Finally, in-person interventions, but also larger social norms and media interventions, should address precarious masculinity—with an emphasis on reaching wider audiences. Masculinity is a learned social construct, suggesting that men are taught, through societal norms and encounters, to feel precarious about their masculinity. Because men are taught these ideals we can also restructure and alter them (Dworkin et al., 2015; Gupta et al., 2008; Leone & Parrott, 2018). Thus, intervention initiatives at the individual and larger societal level can focus on addressing precarious masculinity norms and teaching positive conceptualizations of masculinity to all men, not just those attending college (Leone & Parrott, 2018).

Footnotes

This project and publication was supported by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) of the National Institutes of Health under award number F31AA027150 and L30AA031129 (both to Tiffany Lynn Marcantonio).The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAAA or National Institute of Health.

There were demographic differences between the SONA and Prolific samples. Men recruited from Prolific were older, more racially and ethnically diverse, and had more diverse relationship statuses then college men. College men had more diverse sexual orientations and were at greater likelihood to have involvement with campus fraternity systems.

The original NIAAA item assesses participants’ alcohol use over 12 months. We adjusted the time frame for this item because this study was part of a larger alcohol administration project and was used as a screener tool to assess participants’ eligibility for the alcohol administration study.

References

- Abbey A. Alcohol-related sexual assault: A common problem among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(Supplement 14):118–128. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A. Alcohol's role in sexual violence perpetration: Theoretical explanations, existing evidence and future directions. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2011;30(5):481–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A., McDaniel C., Jilani Z. Alcohol and men's sexual aggression: Review of research and implications for prevention. In: Orchowski L., Berkowitz A., editors. Engaging boys and men in sexual assault prevention. 2022. pp. 183–210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A., Wegner R., Woerner J., Pegram S. E., Pierce J. Review of survey and experimental research that examines the relationship between alcohol consumption and men's sexual aggression perpetration. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2014;15(4):265–282. doi: 10.1177/1524838014521031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benbouriche M., Testé B., Guay J.-P., Lavoie M. E. The role of rape-supportive attitudes, alcohol, and sexual arousal in sexual (mis) perception: An experimental study. Journal of Sex Research. 2019;56(6):766–777. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2018.1496221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosson J. K., Vandello J. A., Burnaford R. M., Weaver J. R., Arzu Wasti S. Precarious manhood and displays of physical aggression. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2009;35(5):623–634. doi: 10.1177/0146167208331161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor D., Fisher B., Chibnall S., Townsend R., Lee H., Bruce C., Thomas G. Association of American Universities; 2017. Report on the AAU campus climate survey on sexual assault and sexual misconduct.https://www.aau.edu/key-issues/aau-climate-survey-sexual-assault-and-sexual-misconduct-2015 [Google Scholar]

- Cowan G., Mills R. D. Personal inadequacy and intimacy predictors of men's hostility toward women. Sex Roles. 2004;51(1/2):67–78. doi: 10.1023/B:SERS.0000032310.16273.da. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crane C. A., Godleski S. A., Przybyla S. M., Schlauch R. C., Testa M. The proximal effects of acute alcohol consumption on male-to-female aggression: A meta-analytic review of the experimental literature. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2016;17(5):520–531. doi: 10.1177/1524838015584374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K. C. The influence of alcohol expectancies and intoxication on men's aggressive unprotected sexual intentions. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;18(5):418–428. doi: 10.1037/a0020510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K. C., Danube C. L., Stappenbeck C. A., Norris J., George W. H. Background predictors and event-specific characteristics of sexual aggression incidents: The roles of alcohol and other factors. Violence Against Women. 2015;21(8):997–1017. doi: 10.1177/1077801215589379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGue S., Valle L. A., Holt M. K., Massetti G. M., Matjasko J. L., Tharp A. T. A systematic review of primary prevention strategies for sexual violence perpetration. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2014;19(4):346–362. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denhard L., Mahoney P., Kim E., Gielen A. A review of alcohol use interventions on college campuses and sexual assault outcomes. Current Epidemiology Reports. 2020;7(4):363–375. doi: 10.1007/s40471-020-00253-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin S. L., Fleming P. J., Colvin C. J. The promises and limitations of gender-transformative health programming with men: Critical reflections from the field. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2015;17(sup2):128–143. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1035751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler R. M., Skidmore J. R. Masculine gender role stress. Scale development and component factors in the appraisal of stressful situations. Behavior Modification. 1987;11(2):123–136. doi: 10.1177/01454455870112001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flack W. F., Hansen B. E., Hopper A. B., Bryant L. A., Lang K. W., Massa A. A., Whalen J. E. Some types of hookups may be riskier than others for campus sexual assault. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2016;8(4):413–420. doi: 10.1037/tra0000090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fugitt J. L., Ham L. S. Beer for “brohood”: A laboratory simulation of masculinity confirmation through alcohol use behaviors in men. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2018;32(3):358–364. doi: 10.1037/adb0000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher K. E., Parrott D. J. What accounts for men's hostile attitudes toward women? The influence of hegemonic male role norms and masculine gender role stress. Violence Against Women. 2011;17(5):568–583. doi: 10.1177/1077801211407296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher K. E., Parrott D. J. A self-awareness intervention manipulation for heavy-drinking men's alcohol-related aggression toward women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2016;84(9):813–823. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George W. H., Stoner S. A., Norris J., Lopez P. A., Lehman G. L. Alcohol expectancies and sexuality: A self-fulfilling prophecy analysis of dyadic perceptions and behavior. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61(1):168–176. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola P. R., Duke A. A., Ritz K. Z. Alcohol, violence, and the Alcohol Myopia Model: Preliminary findings and implications for prevention. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(10):1019–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore A. K., Lewis M. A., George W. H. A randomized controlled trial targeting alcohol use and sexual assault risk among college women at high risk for victimization. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2015;74:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta G. R., Parkhurst J. O., Ogden J. A., Aggleton P., Mahal A. Structural approaches to HIV prevention. The Lancet. 2008;372(9640):764–775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan M., Lanni D. J., Warnke A., Pickett S. M., Parkhill M. R. Emotion regulation moderates the relationship between alcohol consumption and the perpetration of sexual aggression. Violence Against Women. 2019;25(9):1053–1073. doi: 10.1177/1077801218808396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan M., Parkhill M. R., Schuetz B. A., Cox A. A within-subjects analysis of men's alcohol-involved and nonalcohol-involved sexual assaults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2019;34(16):3392–3413. doi: 10.1177/0886260516670179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan M., VanDaalen R. A., Eldridge N., Davis K. C. Sensation seeking and alcohol expectancies regarding sexual aggression as moderators of the relationship between alcohol use and coercive condom use resistance intentions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2023;37(2):309–317. doi: 10.1037/adb0000822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone R. M., Haikalis M., Parrott D. J., Teten Tharp A. A laboratory study of the effects of men's acute alcohol intoxication, perceptions of women's intoxication, and masculine gender role stress on the perpetration of sexual aggression. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2022;46(1):166–176. doi: 10.1111/acer.14753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone R. M., Parrott D. J. Hegemonic masculinity and aggression. In The Routledge international handbook of human aggression: Current issues and perspectives. 2018:31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor & Francis. Moore T. M., Stuart G. L. Effects of masculine gender role stress on men's cognitive, affective, physiological, and aggressive responses to intimate conflict situations. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2004;5(2):132–142. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.5.2.132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morean M. E., Darling N., Smit J., DeFeis J., Wergeles M., Kurzer-Yashin D., Custer K.2021Preventing and responding to sexual misconduct: Preliminary efficacy of a peer-led bystander training program for preventing sexual misconduct and reducing heavy drinking among collegiate athletes Journal of Interpersonal Violence 367-8NP3453–NP3479 10.1177/0886260518777555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murnen S. K., Wright C., Kaluzny G. If “boys will be boys,” then girls will be victims? A meta-analytic review of the research that relates masculine ideology to sexual aggression. Sex Roles. 2002;46:359–375. doi: 10.1023/A:1020488928736. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking levels defined. 2020. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism 2022Screen and assess: Use quick, effective methods https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/health-professionals-communities/core-resource-on-alcohol/screen-and-assess-use-quick-effective-methods#:~:text=The%20NIAAA%20Single%20Alcohol%20Screening,positive…%2C”%20below).

- Norona J. C., Borsari B., Oesterle D. W., Orchowski L. M.2021Alcohol use and risk factors for sexual aggression: Differences according to relationship status Journal of Interpersonal Violence 369-10NP5125–NP5147 10.1177/0886260518795169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris J., George W. H., Davis K. C., Martell J., Leonesio R. J. Alcohol and hypermasculinity as determinants of men's empathic responses to violent pornography. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14(7):683–700. doi: 10.1177/088626099014007001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orchowski L. M., Barnett N. P., Berkowitz A., Borsari B., Oesterle D., Zlotnick C. Sexual assault prevention for heavy drinking college men: Development and feasibility of an integrated approach. Violence Against Women. 2018;24(11):1369–1396. doi: 10.1177/1077801218787928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott D. J., Leone R. M., Schipani-McLaughlin A. M., Salazar L. F., Nizam Z., Gilmore A. Alcohol-related sexual violence perpetration toward sexual and gender minority populations: A critical review and call to action. In: DiLillo D., Gervais S. J., McChargue D. E., editors. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Alcohol and Sexual Violence. Vol. 68. Springer; 2023. pp. 105–138. Advance online publication. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-24426-15. [Google Scholar]

- Seabrook R. C., Ward L. M., Giaccardi S. Why is fraternity membership associated with sexual assault? Exploring the roles of conformity to masculine norms, pressure to uphold masculinity, and objectification of women. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2018;19(1):3–13. doi: 10.1037/men0000076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., Brasfield H., Zapor H. Z., Febres J., Stuart G. L. The relation between alcohol use and psychological, physical, and sexual dating violence perpetration among male college students. Violence Against Women. 2015;21(2):151–164. doi: 10.1177/1077801214564689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., Stuart G. L., McNulty J. K., Moore T. M. Acute alcohol use temporally increases the odds of male perpetrated dating violence: A 90-day diary analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(1):365–368. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. M., Parrott D. J., Swartout K. M., Tharp A. T. Deconstructing hegemonic masculinity: The roles of antifemininity, subordination to women, and sexual dominance in men's perpetration of sexual aggression. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2015;16(2):160–169. doi: 10.1037/a0035956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele C. M., Josephs R. A. Alcohol myopia. Its prized and dangerous effects. The American Psychologist. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang E., Peterson Z. D., Hill Y. N., Heiman J. R. Discrepant responding across self-report measures of men's coercive and aggressive sexual strategies. Journal of Sex Research. 2013;50(5):458–469. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.646393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartout K. M., Parrott D. J., Cohn A. M., Hagman B. T., Gallagher K. E. Development of the Abbreviated Masculine Gender Role Stress Scale. Psychological Assessment. 2015;27(2):489–500. doi: 10.1037/a0038443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M. The impact of men's alcohol consumption on perpetration of sexual aggression. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22(8):1239–1263. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(02)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Brown W. C., Wang W. Do men use more sexually aggressive tactics when intoxicated? A within-person examination of naturally occurring episodes of sex. Psychology of Violence. 2019;9(5):546–554. doi: 10.1037/vio0000186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Cleveland M. J. Does alcohol contribute to college men's sexual assault perpetration? Between-and within-person effects over five semesters. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2017;78(1):5–13. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharp A. T., DeGue S., Valle L. A., Brookmeyer K. A., Massetti G. M., Matjasko J. L. A systematic qualitative review of risk and protective factors for sexual violence perpetration. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2013;14(2):133–167. doi: 10.1177/1524838012470031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandello J. A., Bosson J. K., Cohen D., Burnaford R. M., Weaver J. R. Precarious manhood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95(6):1325–1339. doi: 10.1037/a0012453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]