Abstract

Tuft cells are chemosensory cells associated with luminal homeostasis, immune response, and tumorigenesis in the gastrointestinal tract. We aimed to elucidate alterations in tuft cell populations during gastric atrophy and tumorigenesis in humans with correlative comparison to relevant mouse models. Tuft cell distribution was determined in human stomachs from organ donors and in gastric pathologies including Ménétrier's disease, Helicobacter pylori gastritis, intestinal metaplasia (IM), and gastric tumors. Tuft cell populations were examined in Lrig1‐Kras G12D , Mist1‐Kras G12D , and MT‐TGFα mice. Tuft cells were evenly distributed throughout the entire normal human stomach, primarily concentrated in the isthmal region in the fundus. Ménétrier's disease stomach showed increased tuft cells. Similarly, Lrig1‐Kras mice and mice overexpressing TGFα showed marked foveolar hyperplasia and expanded tuft cell populations. Human stomach with IM or dysplasia also showed increased tuft cell numbers. Similarly, Mist1‐Kras mice had increased numbers of tuft cells during metaplasia and dysplasia development. In human gastric cancers, tuft cells were rarely observed, but showed positive associations with well‐differentiated lesions. In mouse gastric cancer xenografts, tuft cells were restricted to dysplastic well‐differentiated mucinous cysts and were lost in less differentiated cancers. Taken together, tuft cell populations increased in atrophic human gastric pathologies, metaplasia, and dysplasia, but were decreased in gastric cancers. Similar findings were observed in mouse models, suggesting that, while tuft cells are associated with precancerous pathologies, their loss is most associated with the progression to invasive cancer.

Keywords: tuft cell, gastric atrophy, gastric metaplasia, gastric cancer

Introduction

Tuft cells are specialized chemosensory cells with distinct tufted apical microvilli, which are found in multiple organs such as intestine, stomach, trachea, and thymus [1]. While tuft cells are epithelial in origin, their primary functions are akin to immune cells, mediating the host response to various microbial infections in the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts [2]. The best characterized role of tuft cells is to recognize helminth and protist infection in the intestinal lumen, initiating a type 2 immune response to promote parasite expulsion [3, 4]. Upon sensing parasites through taste receptors or succinate receptor 1, intestinal tuft cells release IL‐25, stimulating type 2 innate lymphoid cells to produce IL‐13, which in turn stimulates differentiation of intestinal stem cells toward tuft‐ and goblet cell lineages [3, 4]. Besides this luminal sensing of microbes, tuft cells have been linked to a wide variety of functions, such as epithelial repair and remodeling [5], cross talk with the nervous system [6], and T cell tolerance [7]. Thus, it is not surprising to find that tuft cells are involved in allergy [8, 9], acute and chronic duodenitis [10], inflammatory bowel disease [11, 12, 13], and even cancer initiation and progression [14, 15].

While recognition of the key role for tuft cells in regulating the immune response to pathogens comes from the study of intestine, their roles in inflammation, tissue injury, and tumorigenesis have also been actively investigated in the pancreas and colon. Even though tuft cells are normally absent in the murine pancreas, they appear in response to chronic injury [16] or expression of tumor‐initiating Kras mutation [17, 18]. Tuft cell formation first occurs in acinar‐to‐ductal metaplasia and remains high in early pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN), although they become less abundant in late PanIN and rare in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [17]. Most recently, these tuft cells have been identified to reduce the severity of pancreatic injury and limit tumor progression by producing prostaglandin D2 (PGD2), indicating a protective role of tuft cells in tissue injury and tumorigenesis in the pancreas [15].

Similar to the pancreas, the stomach also develops intestinal‐type gastric cancer through a sequence of chronic inflammation to metaplasia to dysplasia. In addition, activation of the RTK‐RAS pathway is observed in greater than 40% of intestinal‐type gastric cancers [19]. Thus, it is likely that gastric tuft cells may also play a crucial role during gastric carcinogenesis. However, in contrast to the extensive studies on the dynamics and functional implications of tuft cells in the intestine and pancreas, there are few published studies investigating the functional role of gastric tuft cells [20]. The tuft cell population is expanded in several mouse models of oxyntic atrophy and metaplasia induced by DMP‐777, L‐635, Helicobacter felis infection, Areg deficiency, or Kras activation [21, 22, 23, 24]. A large number of tuft cells have been observed in gastric tumors that developed in the junction between the forestomach and the glandular epithelium in SMAD3‐deficient mice [25]. Most studies on tuft cells in the stomach have been performed in mouse models, while only few studies have examined tuft cells in human stomach and their relation to gastric diseases [22, 26, 27].

In this study, we have aimed to provide a more comprehensive analysis of the dynamics of tuft cells in the normal human stomach and during oxyntic atrophy, metaplasia, and cancer. We have defined the global distribution of tuft cells within normal entire human stomach and investigated their dynamics during the progression of precancerous lesions to gastric cancer. We have correlated our findings on tuft cell populations in humans with relevant mouse models of oxyntic atrophy, foveolar hyperplasia, metaplasia, and cancer. These studies demonstrate the dynamics of tuft cells in the stomach following oxyntic atrophy and metaplasia and their diminution during the final stages of cancer progression.

Materials and methods

Mice

The care, maintenance, and treatment of the mice used in this study followed protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Vanderbilt University. The generation of Lrig1‐Kras, Lrig1‐CreERT2 Tg/+ ; LSL‐Kras(G12D) Tg/+ mice and Mist1‐Kras, Mist1‐CreERT2 Tg/+ ; LSL‐Kras(G12D) Tg/+ mice has been previously described [28, 29]. To induce active Kras in gastric stem/progenitor cells or chief cells, LSL‐Kras(G12D) Tg/+ mice were bred with Lrig1‐CreERT2 Tg/+ mice or Mist1‐CreERT2 Tg/+ mice, respectively. Lrig1‐CreERT2 Tg/+ , Mist1‐CreERT2 Tg/+ , or LSL‐Kras(G12D) Tg/+ mice were maintained on a C57BL6 background. For Lrig1‐Kras mouse studies, 8‐week‐old Lrig1‐Kras mice were administered with 2 mg of tamoxifen (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in corn oil by intraperitoneal injection and were sacrificed 2 months after tamoxifen treatment (n = 3). For Mist1‐Kras mouse studies, 8‐week‐old Mist1‐Kras mice were administered with 5 mg of tamoxifen (Sigma) in corn oil with 10% ethanol by subcutaneous injection for three consecutive days and were sacrificed 1 month, 2 months, and 4 months after tamoxifen treatment (n = 3).

Human tissue acquisition and tissue arrays

Under an Institutional Review Board (IRB)‐approved protocol, entire stomachs were obtained from three human donors, and tissue microarrays (TMAs) were constructed for each donor stomach in the Vanderbilt Translational Pathology Shared Resource, as previously described [30]. Information on the characteristics of the organ donors is detailed in supplementary material, Table S1. Human tissue array sets containing Helicobacter pylori‐gastritis, intestinal metaplasia (IM), gastric adenomas, and gastric cancers were constructed using specimens obtained from patients who underwent curative endoscopic or surgical resection for gastric tumors at Jeju National University Hospital in South Korea. Clinicopathological information of patients is detailed in supplementary material, Table S2. Tissue array construction was described previously [31, 32]. Tissue collection or array construction for histological examination was approved by the IRB of Jeju National University Hospital (IRB protocol no. 2022‐01‐009).

Metallothionein‐TGFα transgenic mice and patient with Ménétrier's disease

Unstained paraffin‐embedded sections from metallothionein (MT)‐TGFα transgenic mice were retrieved from a prior investigation [33]. The transgenic mice expressed TGFα under the control of the heavy metal‐inducible promoter/enhancer MT upon exposure to supplemental zinc [33]. Two nontransgenic mice and three MT‐TGFα transgenic mice were administered 25 mmol/l ZnSO4 in their drinking water at 1 month of age and sacrificed 2 weeks later. Additionally, one gastric specimen from a patient with Ménétrier's disease was available from a previous study [34], exhibiting characteristic histologic features of the disease, such as marked foveolar hyperplasia and distortion.

Dysplastic stem cell‐derived tumors in nude mice

Invasive cancer formation in nude mice derived from dysplastic stem cells has been previously reported [35], and unstained paraffin‐embedded sections from these experiments were obtained. In brief, CD133+/CD166+ double‐positive dysplastic stem cells were isolated from Meta4 organoids using fluorescence‐activated cell sorting. Following cell sorting, 30,000 cells were subcutaneously injected into both flanks of 6‐week‐old female Nu/J nude mice. At 7–13 weeks after injection, all mice were sacrificed and tumors were resected. For the passaged tumor formation, tumor spheres generated from either cystic adenocarcinoma or tubular adenocarcinoma were dissociated, and 30,000 cells were injected. All resected tumors were used for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunostaining.

Immunostaining including multiplexed immunofluorescence

Paraffin‐embedded tissues were sectioned at a thickness of 5 μm and stained with H&E. For immunostaining, unstained paraffin‐embedded tissues or organoid sections were deparaffinized in Histoclear and rehydrated through a serial dilution of ethanol. Antigen retrieval was performed in target retrieval solution (Dako, Santa Clara, CA, USA) using a pressure cooker for 15 min. Sections were rinsed in dH2O and incubated with serum‐free protein block solution (Dako) for 1.5 h at room temperature (RT). Primary antibody incubation was performed at 4 °C overnight. For immunohistochemistry, sections were incubated with HRP‐conjugated secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories, Newark, CA, USA) for 15 min at RT. Then, sections were visualized using the Dako Envision+ Detection System Peroxidase/DAB substrate (Dako) according to the manufacturer's instructions and counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After dehydration, sections were scanned on an SCN400 slide scanner (Leica Biosystems, Deer Park, IL, USA) at ×20 magnification. For multiplexed immunofluorescence (IF), Alexa Fluor‐conjugated secondary antibodies were incubated at RT for 1 h. For nuclear staining, sections were incubated with Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 5 min at RT. Information on primary antibodies and their dilutions are detailed in supplementary material, Table S3. Images were captured on a Zeiss Axio Imager M2 microscope using Axiovision digital imaging system at ×10, ×20, or ×40 magnification.

Histopathologic analysis and quantitation

For mouse stomach sections, at least five representative images of the proximal stomach corpus were captured from each mouse (n = 3) at ×20 magnification. To determine the number of tuft cells or enteroendocrine cells per gastric unit, cells positive for DCLK1 or chromogranin‐A (CgA) in all images were manually counted and divided by the total number of glands. To determine the proportion of tuft cells according to their location, we segmented gastric glands into lower, middle, and upper regions and manually counted the number of tuft cells within each area along the gastric units. In the case of cancer sections from nude mice, the histological differentiation of cancer was evaluated using the same criteria as that used for human gastric cancers, where well‐differentiated cancer comprised >95% of glands, moderately differentiated cancer comprised 50–95% of glands, and poorly differentiated cancer comprised <50% of glands. At least five representative images were captured from each tumor at ×20 magnification, and cells positive for DCLK1, UEA1, or Ki‐67 were counted. We assessed the association between tuft cell numbers and histological differentiation, as well as between tuft cell numbers and UEA1 or Ki‐67‐positive cells. CLDN3 expression in cancer was determined by staining intensity and the percentage of cancer cells positive for CLDN3. Histoscores (H scores) were calculated by multiplying the intensity (0 = negative; 1 = weak; 2 = moderate; 3 = strong) and the percentage of positive cells (range = 0–100), with scores ranging from 0 to 300. We examined the association between CLDN3 H scores and DCLK1‐positive cell number per 0.09 mm2.

In human TMA samples, to measure the number of tuft cells per gastric unit, cells positive for POU2F3 or ChAT in each TMA core were manually counted and divided by the total number of glands. The extent of inflammation, neutrophilic activity, atrophy, and IM was determined based on the Sydney Classification [36] by two gastrointestinal pathologists (BJ and SHL). In brief, chronic inflammation was graded as mild, moderate, and marked based on the density of the chronic inflammatory cell infiltration, such as lymphocytes and plasma cells in the lamina propria. Likewise, neutrophilic activity was assessed by the extent of neutrophilic infiltration in the lamina propria and superficial epithelium. Atrophy of the gastric mucosa was defined as loss of corpus or antral glands and IM was graded by the extent of replacement of gastric epithelium by metaplastic epithelium.

Organoid culture

Meta4 organoids were established from Mist1‐CreERT2Tg/+;LSL‐Kras(G12D)Tg/+ (Mist1‐Kras) transgenic mice [28, 37]. These organoids were maintained as previously described [35], cultured in Cultrex® Reduced Growth Factor Basement Membrane Extract, Type R1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and Mouse IntestiCult™ Intestinal Organoid Growth Medium (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada), supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in 48‐well plates. Organoids were monitored using an EVOS M7000 inverted microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to obtain phase‐contrast images. All experiments were repeated at least two to three times.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Unpaired two‐tailed Student's t‐test was utilized for two‐group comparisons to determine statistical significance and calculate p values. For multiple comparisons, one‐way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test was performed. Each experiment was replicated independently two to three times. The variation (mean ± standard deviation) and statistical tests (p values) are reported in the figure legends.

Results

Distribution of tuft cells in the normal human stomach

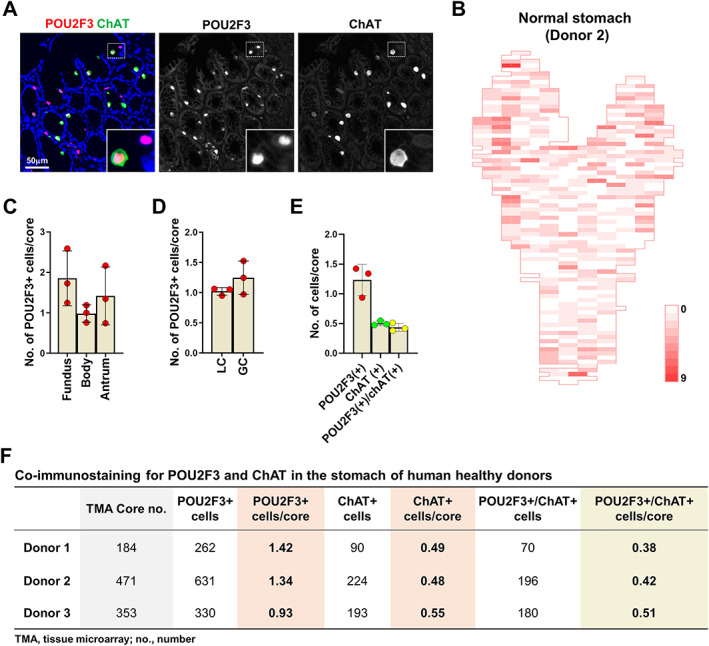

Despite many discoveries on tuft cells, their significance in the human stomach remains largely unknown. In particular, the distribution of tuft cells in the human stomach has never been studied. We have previously defined the geographic anatomy of cell lineages within the human stomach using tissue arrays covering the entire stomachs of three organ donors, but at that time no antibodies were available to define human tuft cells [30]. With the same tissue arrays, we performed immunohistochemical staining for POU2F3, a transcription factor required for tuft cell differentiation, and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), which is considered a marker of tuft cell maturation. We considered POU2F3‐positive cells as tuft cells based on the fact that POU2F3 expression is present in both mature and immature tuft cells [38]. In normal stomachs, tuft cells were only seen near the isthmus/neck area with very low frequency, but in some cases, they were observed conglomerated and co‐positive for ChAT (Figure 1A). Based on the number of tuft cells per tissue array core, we generated 2‐dimensional heatmaps showing the distribution of tuft cells in normal human stomachs (Figure 1B and supplementary material, Figure S1). Tuft cell numbers appeared to be slightly higher in the fundus and antrum than in the corpus, but this difference was not statistically significant (Figure 1C). There was also no significant difference in tuft cell numbers between the lesser curvature and greater curvature (Figure 1D). Overall, normal stomachs contained approximately one tuft cell per core (0.06–0.09 per gastric unit), and 30–50% of POU2F3‐positive tuft cells expressed ChAT (Figure 1E,F).

Figure 1.

Distribution of tuft cells in the normal human stomach. (A) Immunostaining for POU2F3 and ChAT in the corpus of normal human stomach. (B) Two‐dimensional map of the numbers of POU2F3‐positive cells in the entire stomach of a human donor (C and D) Quantitation of POU2F3‐positive cells per tissue array core in the stomachs of three human organ donors according to the location of stomach; fundus, body, and antrum (C) or lesser curvature and greater curvature (D). (E) Quantitation of POU2F3‐ or ChAT‐positive cells per tissue array core in the stomachs of three organ donors. (F) Table showing the total number or average number per core of POU2F3‐positive, ChAT‐positive, or double‐positive cells in each stomach.

Increased tuft cell numbers associated with foveolar hyperplasia and parietal cell loss

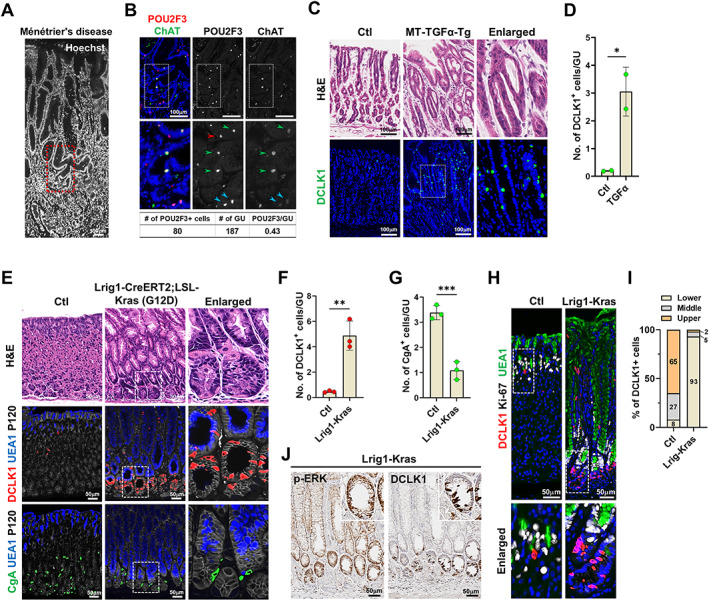

Ménétrier's disease is a rare disorder characterized by diffuse hypertrophic gastric folds in the body and fundus, primarily due to massive foveolar hyperplasia resulting from the overexpression of TGFα [33, 39]. Examination of a gastric specimen from a patient with Ménétrier's disease revealed corkscrew morphology of the foveolar epithelium with marked hyperplasia [34], along with a significantly higher number of tuft cells per gastric unit (0.43) compared to that in normal stomach tissue (0.06–0.09) (Figure 2A,B). Interestingly, POU2F3‐positive cells exhibited varying levels of ChAT expression, suggesting expanded tuft cell populations in the disease may have different maturity (Figure 2B and supplementary material, Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Expansion of doublecortin‐like kinase 1 (DCLK1)‐positive cells in human Ménétrier's disease and mouse models of foveolar hyperplasia. (A and B) Images of Hoechst (A) and co‐immunostaining for POU2F3 and ChAT (B) in the stomach of patient with Ménétrier's disease. Panel (B) corresponds to the red dotted box area in panel (A). (C and D) Representative images of H&E and immunostaining for DCLK1 in the corpus from control and MT‐transforming growth factor α transgenic (MT‐TGFα‐Tg) mice 2 weeks after induction (C) and quantitation of tuft cells per gland in the stomachs of control (n = 2) and MT‐TFGα‐Tg (n = 2) mice (D). (E) Representative images of H&E or co‐immunostaining for DCLK1, UEA1, P120, or CgA in the corpus from control and Lrig1‐Kras mice at 2 months after induction. Dotted box depicts enlarged area. (F and G) Quantitation of DCLK1‐positive (F) and CgA‐positive cells (G) in control (Ctl, n = 3) and Lrig1‐Kras (n = 3) mice. (H) Co‐immunostaining for DCLK1, Ki‐67, and UEA1. (I) Proportion of tuft cells in the lower, middle, and upper areas of gastric glands. (J) Immunohistochemistry for p‐ERK and DCLK1 in Lrig1‐Kras mice at 2 months after induction. No., number; GU, gastric unit. Mean ± SD. Unpaired Student's t‐test or one‐way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Given that TGFα overexpression is thought to be responsible for the pathology of Ménétrier's disease [33, 40], we also investigated the tuft cell population in the stomachs of MT‐TGFα transgenic mice [33]. Two weeks after induction with zinc, TGFα transgenic mice exhibited marked hyperplasia of the foveolar epithelium and higher numbers of tuft cells compared to control mice (Figure 2C,D), consistent with the results observed in the patient with Ménétrier's disease.

Ménétrier's disease has been linked to ERK activation in isthmal progenitor cells [34]. Lrig1‐Kras mice with targeted activation of Kras in isthmal progenitor cells display a similar pattern of massive foveolar hyperplasia [29]. Lrig1‐Kras mice develop foveolar hyperplasia at 2 months after induction. We examined whether active Kras affects populations of tuft cells or enteroendocrine cells by immunostaining with their specific markers; DCLK1 or CgA (Figure 2E). Remarkably, foveolar hyperplastic glands in Lrig1‐Kras mice showed a dramatically increased number of tuft cells (Figure 2F), whereas enteroendocrine cell numbers significantly decreased compared with control group (Figure 2G). Under normal conditions, gastric tuft cells were usually observed near the isthmus/neck region and below the proliferative area (Figure 2H). In Lrig1‐Kras mice, the proliferation center shifted downward to the base (Figure 2H) and a majority of tuft cells were located at the lower third of gastric glands (Figure 2I). Furthermore, tuft cell expansion was restricted to the hyperplastic glands expressing phospho‐ERK (p‐ERK) (Figure 2J and supplementary material, Figure S3). These results demonstrate that foveolar hyperplasia in the stomach is associated with expansion of tuft cells in the corpus mucosa.

Associations between emergence of tuft cells and pathological features of human gastric lesions

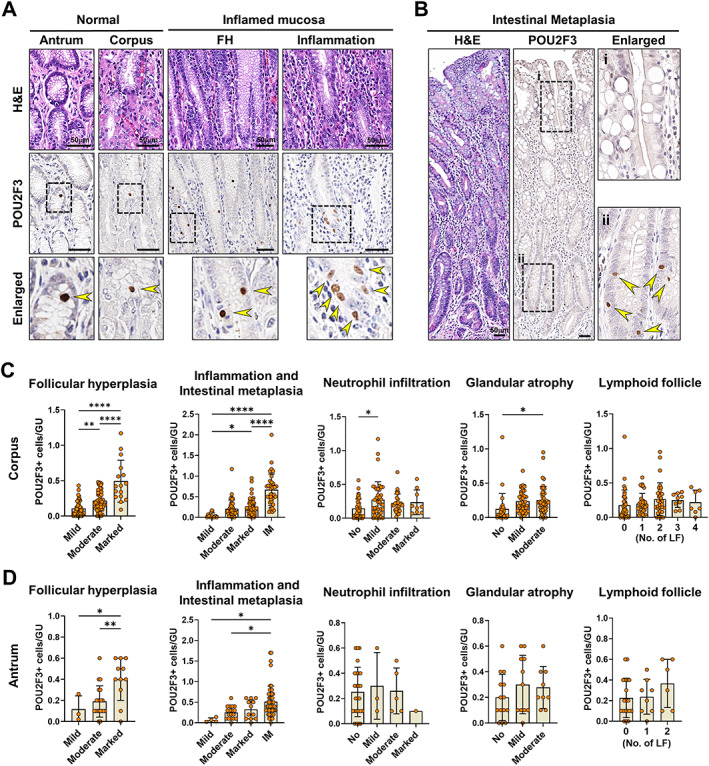

In contrast to Ménétrier's disease, an extremely rare disorder, H. pylori infection in the stomach is prevalent worldwide and is the primary cause of chronic atrophic gastritis followed by IM and intestinal‐type gastric cancers. In a previous report, we demonstrated increased tuft cell numbers in H. felis‐infected mice [21], suggesting that tuft cells can actively respond to H. pylori infection in human stomach. We therefore sought to investigate the dynamics of tuft cells during H. pylori‐induced inflammation and metaplasia through immunostaining for POU2F3 in tissue arrays containing a range of human gastric specimens. Compared to normal gastric mucosa, inflamed atrophic (Figure 3A) and metaplastic (Figure 3B) gastric glands exhibited increased numbers of tuft cells. As observed in Ménétrier's disease, we occasionally detected conglomerated tuft cells in the isthmic area (Figure 3A), suggesting that tuft cells might be newly generated from stem/progenitor cell populations.

Figure 3.

Associations between tuft cells and pathological features of human gastric lesions. (A) Representative images of H&E and immunostaining for POU2F3 in the normal antrum and corpus and gastric mucosa with foveolar hyperplasia (FH) or inflammation. (B) H&E and immunostaining for POU2F3 in the IM of stomach. (C and D) Quantitation of POU2F3‐positive cells per gastric unit according to the pathological features such as FH, chronic inflammation, activity, glandular atrophy, IM, and lymphoid follicles (LFs) in the antrum (C) and corpus (D). GU, gastric unit. Mean ± SD. One‐way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

We applied the Sydney system used in the classification of gastritis to evaluate the extent of neutrophil activity, chronic inflammation, atrophy, and IM, and examined the correlation between each of the pathological variables and the numbers of tuft cells. Tuft cell numbers had significant positive associations with the extent of foveolar hyperplasia, chronic inflammation, and IM in both the corpus and antrum (Figure 3C,D). The presence of IM was the strongest factor positively associated with tuft cell expansion, and tuft cells in IM were mostly localized at the base of glands (Figure 3B). This finding contrasts with the pattern for tuft cells in the small intestine, where they are more frequently observed in the villi than in the crypts [41]. Mild neutrophilic infiltration and moderate atrophy were also associated with a significant increase in tuft cells in the corpus, whereas the presence of lymphoid follicles did not appear to affect the tuft cell population (Figure 3C,D).

Additionally, to characterize further the expanded tuft cells observed in gastritis and IM, we performed multiple IF staining for POU2F3 and ChAT. In the small intestine, mature tuft cells in the villi typically displayed an elongated shape and strong ChAT expression, whereas tuft cells in the crypts tended to have a round to oval shape and occasionally lacked ChAT expression (supplementary material, Figure S4). Notably, tuft cells in the stomach with chronic inflammation or IM showed a round to oval shape with varying levels of ChAT expression (supplementary material, Figure S5). Furthermore, we demonstrated that these POU2F3‐positive cells co‐expressed pan‐cytokeratin, confirming their epithelial lineage (supplementary material, Figure S6). Comparing the proportions of POU2F3 single‐positive, ChAT single‐positive, and POU2F3/ChAT double‐positive cells in the small intestine, colon, and stomach, POU2F3 single‐positive cells were significantly more abundant in the stomach than in intestines (supplementary material, Figure S5). This increased POU2F3 single‐positive population may represent an expansion of immature tuft cells in response to inflammation induced by H. pylori infection. These findings suggest that human gastric tuft cells expand in response to inflammation and IM and display a different morphological phenotype from their counterparts in the small and large intestines.

Expansion of DCLK1‐positive tuft cells in the Mist1‐Kras mouse model of metaplasia and dysplasia

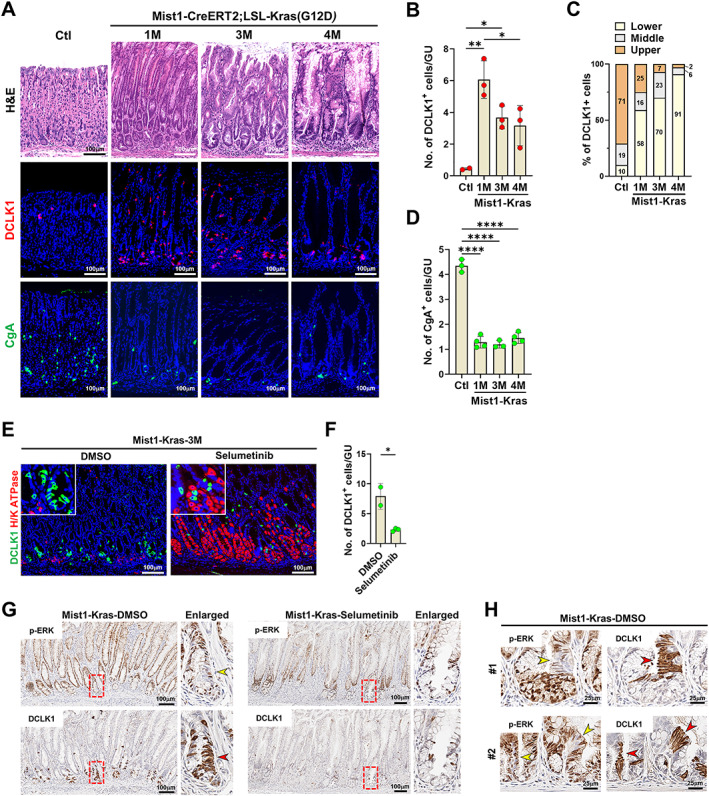

In previous studies, we have generated a model of induction of spasmolytic polypeptide‐expressing metaplasia (SPEM) and IM in Mist1‐Kras mice with tamoxifen‐inducible expression of constitutively active Kras(G12D) in Mist1+ mature chief cells in the gastric mucosa [28]. Mist1‐Kras mice display pyloric metaplasia glands with SPEM cell lineages at 1 month and dysplastic glands at 4 months after induction and SPEM, and metaplastic and dysplastic cells can be identified by the markers CD44v9 and TROP2, respectively [31]. Beginning at 1 month after induction, Mist1‐Kras mice exhibited a markedly increased number of tuft cells and a decreased number of enteroendocrine cells compared with controls (Figure 4A–D). Notably, tuft cells were located at the bases of glands along with metaplasia and dysplasia progression (Figure 4C). The tuft cell lineages expanded in association with metaplasia induction had an elongated morphology similar to normal tuft cells in the small intestine, and co‐expressed other tuft cell markers such as POU2F3, phospho‐EGFR (p‐EGFR), and advillin (supplementary material, Figure S7). Tuft cells did not express either CD44v9 or TROP2 (supplementary material, Figure S8), suggesting that tuft cells represent a distinct cell lineage in Kras‐induced metaplastic or dysplastic glands.

Figure 4.

Expression of tuft cells in the Mist1‐Kras mouse model of metaplasia and cancer. (A) H&E and co‐immunostaining for DCLK1 or CgA in control mice and Mist1‐Kras mice at 1, 3, and 4 months (M) after induction. (B and C) Quantitation of DCLK1‐positive cells (B) and their location in the corpus of control (n = 3) and Mist1‐Kras (n = 3) mouse stomachs. (D) Quantitation of CgA‐positive cells. (E and F) Co‐immunostaining for DCLK1, H/K ATPase at 3 months after induction in Mist1‐Kras mice treated with DMSO (n = 2) or selumetinib (n = 3) for 2 weeks (E) and quantitation of DCLK1‐positive cells in the corpus of stomach (F). (G) Serial sections from Mist1‐Kras mice treated with DMSO or selumetinib for 2 weeks stained for p‐ERK or DCLK1. Red boxes indicate regions shown in enlarged view at right. (H) Serial sections from two Mist1‐Kras mice treated with DMSO stained for p‐ERK or DCLK1 demonstrating the lack of p‐ERK expression in tuft cells. No., number, GU, gastric unit. Mean ± SD. Unpaired Student's t‐test or one‐way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

To examine the effect of MEK/ERK signaling inhibition on the tuft cell population in vivo, Mist1‐Kras mice at 3 months after induction were treated with selumetinib for 2 weeks. Consistent with previous findings [28], MEK inhibition restored normal oxyntic glands containing parietal cells (Figure 4E). Furthermore, tuft cell numbers were significantly decreased in selumetinib‐treated mice compared to vehicle‐treated control mice (Figure 4E,F). Interestingly, while other epithelial cells are strongly positive for p‐ERK following Kras activation, tuft cells appeared to be negative for p‐ERK (Figure 4G,H), suggesting that MEK/ERK activity is necessary for tuft cell generation, but is not required to maintain mature tuft cells.

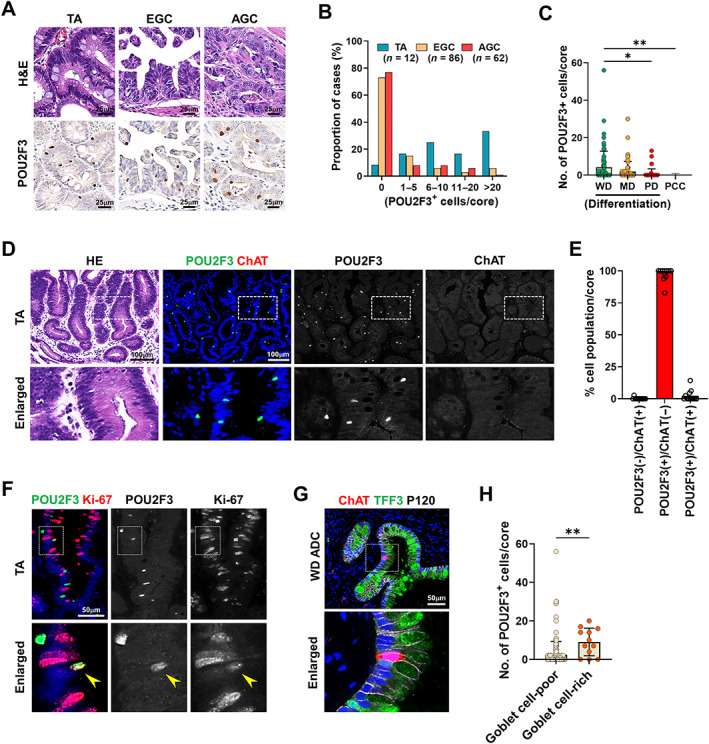

Characteristics of tuft cells in human gastric adenomas and gastric cancers

We next investigated tuft cell populations in human gastric tumors using TMAs that contain a set of tubular adenomas (TAs), early gastric cancers (EGC), and advanced gastric cancers (AGC) (Figure 5A). POU2F3‐positive cells were frequently observed in most TAs, but were rare in gastric cancers (Figure 5B). Of the TAs analyzed, 33% exhibited 20 or more tuft cells per core, and 92% had at least one tuft cell per core. Conversely, no tuft cells were observed in 73% of EGC cases and 77% of AGC cases (Figure 5B). Although tuft cell numbers in gastric cancers were minimal, a positive correlation with histologic differentiation was still noted (Figure 5C). Intriguingly, the majority of tuft cells observed in TAs were negative for ChAT (Figure 5D,E), whereas approximately 30–50% of tuft cells in normal or inflamed gastric mucosa were ChAT‐positive (Figure 1G and supplementary material, Figure S5). This difference may suggest that tuft cells in gastric adenomas possess unique functional characteristics or have not completed full differentiation. Additionally, despite high levels of proliferation activity in gastric tumors, only rare tuft cells were positive for Ki‐67, indicating that tuft cells in tumors remain postmitotic (Figure 5F). Notably, rare cases of gastric cancers with numerous tuft cells tend to have many goblet cells (Figure 5G,H), indicating a potential dependence on the ability of tumor stem cells to give rise to fully differentiated cells.

Figure 5.

Characteristics of tuft cells in human gastric adenomas and cancers. (A) Representative images of H&E and immunostaining for POU2F3 in the TAs, EGC, and AGC. (B) Percentages of cases with various numbers of POU2F3‐positive cells in the TA (n = 8), EGC (n = 86), and AGC (n = 62). (C) Quantitation of POU2F3‐positive cells per core according to differentiation of cancer glands (WD, well differentiated, n = 73; MD, moderately differentiated, n = 87; PD, poorly differentiated, n = 43; PCC, poorly cohesive carcinoma, n = 33). (D and E) H&E and co‐immunostaining for POU2F3 and ChAT in TAs (D) and proportions of cells according to POU2F3 and ChAT positivity (E). (F) Co‐immunostaining for POU2F3 and Ki‐67 in TA. (G and H) Co‐immunostaining for ChAT, TFF3, and P120 in WD adenocarcinoma (G) and quantitation of POU2F3‐positive cells per core in goblet cell‐poor or goblet cell‐rich gastric cancers (H). No., number. Mean ± SD. Unpaired Student's t‐test or one‐way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

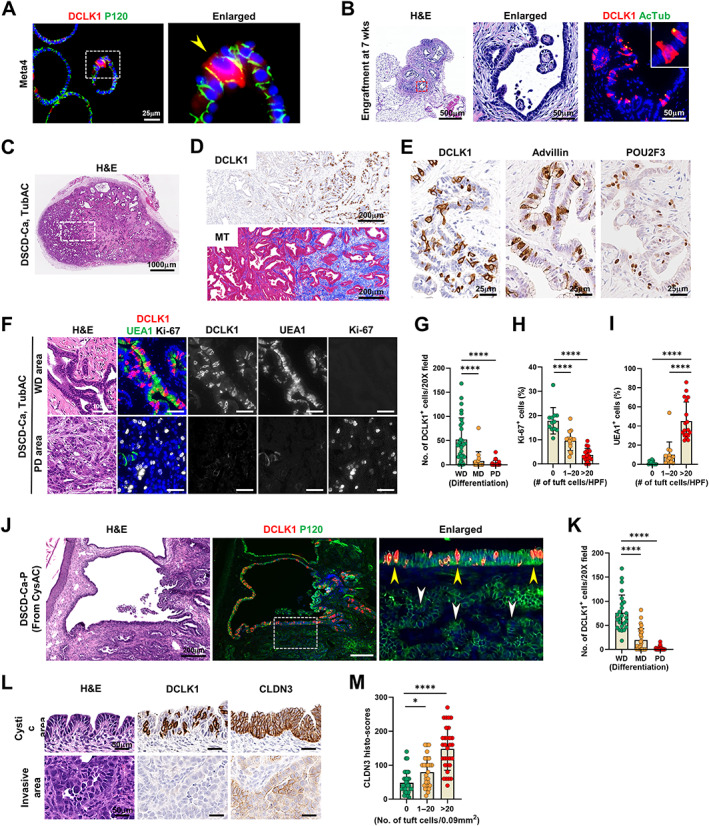

Expression of tuft cells in mouse dysplastic stem cell‐derived cancers

To provide a correlative analysis in mouse tissues, we next investigated tuft cell dynamics during progression of dysplasia to invasive cancers by evaluating cancers that develop from Meta4 gastroid‐derived dysplastic stem cells (DSCD‐Ca) in nude mice [35]. Meta4 organoids normally contain a small number of tuft cells (Figure 6A). At 7 weeks after implantation, dysplastic stem cells sorted from Meta4 gastroids formed a small nodule, composed of cystic and tubular glands with an abundant stroma (Figure 6B). In contrast to Meta4 organoids, glands in the nodule were enriched for tuft cells which were positive for acetylated‐tubulin (Figure 6B). At 13 weeks after implantation, larger nodules with invasive cancers developed and these DSCD‐Ca were defined histologically as either cystic (CysAC) or tubular (TubAC) adenocarcinoma (Figure 6C). Notably, numerous tuft cells were still present in the cystic lesions surrounded by dense fibrotic stroma (Figure 6D). Tuft cells were positive for advillin and POU2F3, as observed in dysplastic glands in Mist1‐Kras mice (Figure 6E). Interestingly, we noted that tuft cells were restricted to well‐differentiated glands composed of mucus cells with very low proliferative activity (Figure 6F and supplementary material, Figures S9 and S10). Indeed, tuft cell numbers showed a negative correlation with tumor differentiation (Figure 6G) and Ki‐67‐positive cells (Figure 6H), but a positive correlation with UEA1‐positive mucus cells (Figure 6I). Furthermore, since tuft cells appeared to be concentrated in glands with abundant stroma, we explored whether the tuft cell population was associated with a specific fibroblast subtype. However, no significant difference was observed in the staining for fibroblast markers, including PDGFRα, PDGFRβ, and α‐SMA between tuft cell‐rich and tuft cell‐poor areas (supplementary material, Figure S11).

Figure 6.

Tuft cell expansion in mouse dysplastic stem cell‐derived cancers in the nude mice. (A) Co‐immunostaining for DCLK1 and P120 in Meta4 organoids. Yellow arrowhead indicates a DCLK1‐positive tuft cell. (B) H&E and co‐immunostaining for DCLK1 and acetylated tubulin (AcTub) in the engraftment formed at 7 weeks after implanting dysplastic stem cells (D133/CD166 double‐positive cells, DSCs) from Meta4 organoids in the nude mice. Red dotted box depicts enlarged area. (C and D) Representative images of H&E (C), immunostaining for DCLK1 and Masson‐trichrome (MT) staining (D) in DSC‐derived cancer (DSCD‐Ca), histologically tubular adenocarcinoma (TubAC), formed at 13 weeks (wks) after implanting DSCs in the nude mice (n = 8). (E) Immunostaining for DCLK1, advillin, and POU2F3 in TubAC. (F and G) H&E and co‐immunostaining for DCLK1, UEA1, and Ki‐67 in the well‐differentiated (WD) or poorly differentiated (PD) areas in TubAC (F) and quantitation of DCLK1‐positive cells according to differentiation of cancer (G). (H and I) Quantitation of Ki‐67‐poisitive cells (H) and UEA1‐positive cells (I) according to the number of tuft cells at high power field (HPF) in TubAC. (J) H&E and co‐immunostaining for DCLK1 and P120 in passaged DSCD‐Ca (DSCD‐Ca‐P) generated by re‐inoculating cystic adenocarcinoma (CysAC) in nude mice. (K) Quantitation of DCLK1‐positive cells according to differentiation of cancer (n = 8). Yellow arrow heads indicate cystic area harboring many tuft cells, whereas white ones indicate adjacent invasive glands with no tuft cells. (L and M) H&E and immunostaining for DCLK1 and CLDN3 in tuft cell‐rich and ‐poor areas (L) and quantitation of CLDN3 histoscores according to the number of tuft cells at high power field in DSCD‐Ca‐P (n = 8) (M). No., number. Mean ± SD. One‐way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test. *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001.

Passaged DSCD‐Ca (DSCD‐Ca‐P), generated by re‐implanting CysAC or TubAC cells back into nude mice, rapidly developed solid and cystic nodules within 3–7 weeks. Tuft cells with POU2F3 and advillin expression were continuously observed in the glands with cystic structures (Figure 6J and supplementary material, Figure S12), whereas adjacent poorly differentiated cancer glands had no or few tuft cells (Figure 6J,K and supplementary material, Figure S13). Claudin3 (CLDN3) is an integral component of the tight junction in epithelia, and reduced CLDN3 expression was associated with the progression and metastasis of lung cancer [42]. We found that invasive cancer glands are formed in tumors 7 weeks after the passaged CysAC cell injection. The invasive cancer glands expressed lower levels of CLDN3 compared to cystic glands and tuft cells showed a positive association with CLDN3 expression (Figure 6L,M and supplementary material, Figure S14). These findings suggest that the tuft cell generation in cancers appears to rely on epithelial integrity and loss of differentiation in cancer cells may coincide a loss of tuft cells, as seen in human cancer samples.

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that active oxyntic atrophy associated with foveolar hyperplasia, metaplasia, or dysplasia can lead to expansion of the tuft cell population in the gastric mucosa. Remarkably, tuft cell alterations in human gastric pathologies were recapitulated in relevant mouse models. For instance, foveolar hyperplasia with parietal cell loss seen in Lrig1‐Kras mice is commonly observed in Ménétrier's disease. More importantly, tuft cell expansion occurred in both IM and gastric adenomas in the human stomach, in line with the results from Mist1‐Kras mice, suggesting that tuft cells might be functionally involved in metaplasia to dysplasia transition. Nevertheless, tuft cells decreased markedly in association with loss of differentiation in cancers in both humans and mice.

In the Mist1‐Kras mouse model, tuft cell numbers appeared to reach their peak during the transition from SPEM through IM, dysplasia, and cancer. However, the differences between SPEM and IM were not statistically significant, consistent with human IM cases. Importantly, unlike the Mist1‐Kras mouse where a distinct SPEM stage is evident at 1‐month after induction, human stomach specimens with inflammation usually lack a distinct SPEM‐only stage. Instead, most human samples showed IM‐predominant changes due to H. pylori‐induced inflammation. Consequently, our study is limited in evaluating tuft cell populations in the SPEM‐only stage in human stomachs, leaving uncertainties regarding potential differences in tuft cell numbers between SPEM and IM stages.

In both Lrig1‐ and Mist1‐Kras mouse models, we observed an increase in tuft cells, while enteroendocrine cell numbers decreased, suggesting that selective lineage commitment also occurs during Kras‐induced oxyntic atrophy. This specific tuft cell expansion following Kras activation was also reported in acinar‐to‐ductal metaplasia in pancreas where tuft cells limited tumor progression by suppressing specific immune responses [43] or by production of PGD2 [15]. In both studies, tuft cells had an impact on tumor progression by influencing the tumor microenvironment. In this study, we also addressed the histologic characteristics associated with increases in tuft cells, particularly during dysplasia progression to cancer. Using invasive cancers generated in the nude mice, we have identified that tuft cells have a strong preference for well‐differentiated cystic or tubular structures with mucin production and they completely disappear in highly invasive areas where structural integrity or cellular adhesion is disrupted. This finding might reflect the process whereby cancer cells become less differentiated and lose their ability to give rise to functional cell lineages such as goblet cells and tuft cells. The precise molecular mechanism of this spatial restriction of tuft cells needs to be investigated further. Moreover, it remains to be elucidated whether tuft cells play a tumor suppressive role in gastric tumorigenesis in the same way as in the pancreas.

Through the analysis of various human gastric specimens representing different pathologies, we have observed that the expansion of tuft cells persists during the chronic inflammation–metaplasia–dysplasia sequence. Similar expression profiles of tuft cells have been observed in the pancreas during pancreatitis [16] and neoplastic progression in mice [15]. This observation leads us to speculate that tuft cell populations expand in response to parietal cell loss during severe tissue damage and might be involved in inflammation‐associated cancer development through their ability to synthesize inflammatory cytokines such as IL‐25, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes. These mediators are also implicated in tumor initiation or progression [44, 45]. For colitis‐associated carcinogenesis, tuft cells have been found to be protective in chronic colitis models [5, 11, 13] and increased in inflammation‐induced carcinogenesis [46]. By contrast, two studies of human inflammatory bowel disease patients reported a reduced number of tuft cells in colon biopsies from quiescent ulcerative colitis [12] and inflamed ileal tissues from Crohn's disease [11]. Since prominent increases in tuft cells occurred during metaplasia evolution both in the stomach and pancreas, the decrease of tuft cells in human inflammatory bowel disease patients may be in part due to the lack of a metaplastic process in the colon. Further investigations are needed to determine whether tuft cells in metaplasia, for example acinar‐to‐ductal metaplasia in the pancreas and SPEM/IM in the stomach, may have unique functional features compared to normal tuft cells.

In summary, tuft cell expansion occurs during metaplasia and dysplasia development induced by oxyntic atrophy in both mouse and human stomach, supporting the concept that tuft cells are not only responders to tissue injury, but also represent an important link to tissue regeneration and adaptation. Future studies are necessary to define molecular mechanisms by which discrete tuft cell populations interact with the microenvironment, and to develop strategies to target tuft cells and harness their beneficial effects in mucosal repair and regeneration.

Author contributions statement

BJ and HK developed the study design and performed experiments. SL and YW performed experiments and edited the manuscript. IK and RJC provided materials and revised the manuscript. EC and JRG developed the study design, analyzed data and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Distribution of tuft cells in the normal stomach of human donors

Figure S2. Tuft cell hyperplasia in the stomach of Ménétrier's disease

Figure S3. Tuft cell expansion confined to the hyperplastic glands induced by Kras activation

Figure S4. Tuft cells in the crypts and villi of normal small intestine

Figure S5. Characteristics of newly emerged tuft cells in chronic gastritis and IM of human stomach

Figure S6. Tuft cells in IM

Figure S7. Expression of tuft cell markers in DCLK1‐positive cells in Mist1‐Kras mice

Figure S8. Associations of tuft cells with metaplastic and dysplastic markers

Figure S9. Enrichment of tuft cells in mucin‐rich tumor glands in dysplastic stem cell‐derived cancers

Figure S10. Histologic characteristics of microenvironment for tuft cell population in dysplastic stem cell‐derived cancers

Figure S11. Expression of fibroblast markers around tuft cell‐rich tumor glands dysplastic stem cell‐derived cancers

Figure S12. Tuft cell markers' expression in dysplastic stem cell‐derived cancers in nude mice

Figure S13. Representative images of immunostaining for DCLK1 in passaged dysplastic stem cell‐derived cancers formed at 3 or 7 weeks after re‐inoculating cystic or tubular adenocarcinoma cells in nude mice

Figure S14. Representative images of H&E and immunostaining for DCLK1 or CLDN3 in passaged dysplastic stem cell‐derived cancers formed at 7 weeks after re‐inoculating cystic adenocarcinoma (CysAC) cells in nude mice

Table S1. Characteristics of human stomach donors

Table S2. Characteristics of gastric tumor patients

Table S3. List of primary antibodies for immunostaining

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding to JRG from grants from a Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award IBX000930, DOD CA190172, and NIH R01 DK101332, to EC from grants from NIH R37 CA244970, NCI R01 CA272687 and an AGA Research Foundation Funderburg Award (AGA2022‐32‐01), and to BJ and HS from grants from National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT, 2021R1C1C1011172 and 2020R1I1A1A01069168). The Vanderbilt Cell Imaging Shared Resource and the Vanderbilt Digital Histology Shared Resource are supported by the Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center (P30 CA068485) and the Vanderbilt Digestive Disease Research Center (P30 DK058404). The Translational Pathology Shared Resource is supported by NCI/NIH Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA68485). The Digital Histology Shared Resource is supported by VA Shared Equipment grant 1IS1BX003097 and the Vanderbilt Digestive Disease Research Center (P30 DK058404).

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Data availability statement

All of the data for this study are contained within the paper and its supplementary files.

References

- 1. Ting H‐A, von Moltke J. The immune function of tuft cells at gut mucosal surfaces and beyond. J Immunol 2019; 202: 1321–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Strine MS, Wilen CB. Tuft cells are key mediators of interkingdom interactions at mucosal barrier surfaces. PLoS Pathog 2022; 18: e1010318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gerbe F, Sidot E, Smyth DJ, et al. Intestinal epithelial tuft cells initiate type 2 mucosal immunity to helminth parasites. Nature 2016; 529: 226–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Howitt MR, Lavoie S, Michaud M, et al. Tuft cells, taste‐chemosensory cells, orchestrate parasite type 2 immunity in the gut. Science 2016; 351: 1329–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yi J, Bergstrom K, Fu J, et al. Dclk1 in tuft cells promotes inflammation‐driven epithelial restitution and mitigates chronic colitis. Cell Death Differ 2019; 26: 1656–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matsumoto I, Ohmoto M, Narukawa M, et al. Skn‐1a (Pou2f3) specifies taste receptor cell lineage. Nat Neurosci 2011; 14: 685–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miller CN, Proekt I, von Moltke J, et al. Thymic tuft cells promote an IL‐4‐enriched medulla and shape thymocyte development. Nature 2018; 559: 627–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ualiyeva S, Hallen N, Kanaoka Y, et al. Airway brush cells generate cysteinyl leukotrienes through the ATP sensor P2Y2. Sci Immunol 2020; 5: eaax7224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leyva‐Castillo J‐M, Galand C, Kam C, et al. Mechanical skin injury promotes food anaphylaxis by driving intestinal mast cell expansion. Immunity 2019; 50: 1262–1275.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huh WJ, Te Roland J, Asai M, et al. Distribution of duodenal tuft cells is altered in pediatric patients with acute and chronic enteropathy. Biomed Res 2020; 41: 113–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Banerjee A, Herring CA, Chen B, et al. Succinate produced by intestinal microbes promotes specification of tuft cells to suppress ileal inflammation. Gastroenterology 2020; 159: 2101–2115.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kjærgaard S, Jensen TS, Feddersen UR, et al. Decreased number of colonic tuft cells in quiescent ulcerative colitis patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 33: 817–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Qu D, Weygant N, May R, et al. Ablation of doublecortin‐like kinase 1 in the colonic epithelium exacerbates dextran sulfate sodium‐induced colitis. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0134212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang Y‐H, Klingbeil O, He X‐Y, et al. POU2F3 is a master regulator of a tuft cell‐like variant of small cell lung cancer. Genes Dev 2018; 32: 915–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. DelGiorno KE, Chung C‐Y, Vavinskaya V, et al. Tuft cells inhibit pancreatic tumorigenesis in mice by producing prostaglandin D2. Gastroenterology 2020; 159: 1866–1881.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. DelGiorno KE, Naeem RF, Fang L, et al. Tuft cell formation reflects epithelial plasticity in pancreatic injury: implications for modeling human pancreatitis. Front Physiol 2020; 11: 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bailey JM, Alsina J, Rasheed ZA, et al. DCLK1 marks a morphologically distinct subpopulation of cells with stem cell properties in preinvasive pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology 2014; 146: 245–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. DelGiorno KE, Hall JC, Takeuchi KK, et al. Identification and manipulation of biliary metaplasia in pancreatic tumors. Gastroenterology 2014; 146: 233–244.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network . Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014; 513: 202–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hayakawa Y, Sakitani K, Konishi M, et al. Nerve growth factor promotes gastric tumorigenesis through aberrant cholinergic signaling. Cancer Cell 2017; 31: 21–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Choi E, Petersen CP, Lapierre LA, et al. Dynamic expansion of gastric mucosal doublecortin‐like kinase 1‐expressing cells in response to parietal cell loss is regulated by gastrin. Am J Pathol 2015; 185: 2219–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saqui‐Salces M, Keeley TM, Grosse AS, et al. Gastric tuft cells express DCLK1 and are expanded in hyperplasia. Histochem Cell Biol 2011; 136: 191–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kinoshita H, Hayakawa Y, Konishi M, et al. Three types of metaplasia model through Kras activation, Pten deletion, or Cdh1 deletion in the gastric epithelium. J Pathol 2019; 247: 35–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Okumura T, Ericksen RE, Takaishi S, et al. K‐ras mutation targeted to gastric tissue progenitor cells results in chronic inflammation, an altered microenvironment, and progression to intraepithelial neoplasia. Cancer Res 2010; 70: 8435–8445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nam KT, O'Neal R, Lee YS, et al. Gastric tumor development in Smad3‐deficient mice initiates from forestomach/glandular transition zone along the lesser curvature. Lab Invest 2012; 92: 883–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schütz B, Ruppert A‐L, Strobel O, et al. Distribution pattern and molecular signature of cholinergic tuft cells in human gastro‐intestinal and pancreatic‐biliary tract. Sci Rep 2019; 9: 17466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mutoh H, Sashikawa M, Sakamoto H, et al. Cyclooxygenase 2 in gastric carcinoma is expressed in doublecortin‐ and CaM kinase‐like‐1‐positive tuft cells. Gut Liver 2014; 8: 508–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Choi E, Hendley AM, Bailey JM, et al. Expression of activated Ras in gastric chief cells of mice leads to the full spectrum of metaplastic lineage transitions. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 918–930.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Choi E, Means AL, Coffey RJ, et al. Active Kras expression in gastric isthmal progenitor cells induces foveolar hyperplasia but not metaplasia. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 7: 251–253.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Choi E, Roland JT, Barlow BJ, et al. Cell lineage distribution atlas of the human stomach reveals heterogeneous gland populations in the gastric antrum. Gut 2014; 63: 1711–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Riera KM, Jang B, Min J, et al. Trop2 is upregulated in the transition to dysplasia in the metaplastic gastric mucosa. J Pathol 2020; 251: 336–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee S‐H, Jang B, Min J, et al. Up‐regulation of aquaporin 5 defines spasmolytic polypeptide‐expressing metaplasia and progression to incomplete intestinal metaplasia. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 13: 199–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dempsey PJ, Goldenring JR, Soroka CJ, et al. Possible role of transforming growth factor α in the pathogenesis of Ménétrier's disease: supportive evidence from humans and transgenic mice. Gastroenterology 1992; 103: 1950–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Burdick JS, Chung E, Tanner G, et al. Treatment of Menetrier's disease with a monoclonal antibody against the epidermal growth factor receptor. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 1697–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Min J, Zhang C, Bliton RJ, et al. Dysplastic stem cell plasticity functions as a driving force for neoplastic transformation of precancerous gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology 2022; 163: 875–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, et al. Classification and grading of gastritis: the updated Sydney system. Am J Surg Pathol 1996; 20: 1161–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Min J, Vega PN, Engevik AC, et al. Heterogeneity and dynamics of active Kras‐induced dysplastic lineages from mouse corpus stomach. Nat Commun 2019; 10: 5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lindholm HT, Parmar N, Drurey C, et al. BMP signaling in the intestinal epithelium drives a critical feedback loop to restrain IL‐13‐driven tuft cell hyperplasia. Sci Immunol 2022; 7: eabl6543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Huh WJ, Coffey RJ, Washington MK. Ménétrier's disease: its mimickers and pathogenesis. J Pathol Transl Med 2016; 50: 10–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nomura S, Settle SH, Leys CM, et al. Evidence for repatterning of the gastric fundic epithelium associated with Ménétrier's disease and TGFα overexpression. Gastroenterology 2005; 128: 1292–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McKinley ET, Sui Y, Al‐Kofahi Y, et al. Optimized multiplex immunofluorescence single‐cell analysis reveals tuft cell heterogeneity. JCI Insight 2017; 2: e93487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Che J, Yue D, Zhang B, et al. Claudin‐3 inhibits lung squamous cell carcinoma cell epithelial–mesenchymal transition and invasion via suppression of the Wnt/β‐catenin signaling pathway. Int J Med Sci 2018; 15: 339–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hoffman MT, Kemp SB, Salas‐Escabillas DJ, et al. The gustatory sensory G‐protein GNAT3 suppresses pancreatic cancer progression in mice. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 11: 349–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhao H, Wu L, Yan G, et al. Inflammation and tumor progression: signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021; 6: 263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang D, DuBois RN. Eicosanoids and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2010; 10: 181–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Westphalen CB, Asfaha S, Hayakawa Y, et al. Long‐lived intestinal tuft cells serve as colon cancer‐initiating cells. J Clin Invest 2014; 124: 1283–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Distribution of tuft cells in the normal stomach of human donors

Figure S2. Tuft cell hyperplasia in the stomach of Ménétrier's disease

Figure S3. Tuft cell expansion confined to the hyperplastic glands induced by Kras activation

Figure S4. Tuft cells in the crypts and villi of normal small intestine

Figure S5. Characteristics of newly emerged tuft cells in chronic gastritis and IM of human stomach

Figure S6. Tuft cells in IM

Figure S7. Expression of tuft cell markers in DCLK1‐positive cells in Mist1‐Kras mice

Figure S8. Associations of tuft cells with metaplastic and dysplastic markers

Figure S9. Enrichment of tuft cells in mucin‐rich tumor glands in dysplastic stem cell‐derived cancers

Figure S10. Histologic characteristics of microenvironment for tuft cell population in dysplastic stem cell‐derived cancers

Figure S11. Expression of fibroblast markers around tuft cell‐rich tumor glands dysplastic stem cell‐derived cancers

Figure S12. Tuft cell markers' expression in dysplastic stem cell‐derived cancers in nude mice

Figure S13. Representative images of immunostaining for DCLK1 in passaged dysplastic stem cell‐derived cancers formed at 3 or 7 weeks after re‐inoculating cystic or tubular adenocarcinoma cells in nude mice

Figure S14. Representative images of H&E and immunostaining for DCLK1 or CLDN3 in passaged dysplastic stem cell‐derived cancers formed at 7 weeks after re‐inoculating cystic adenocarcinoma (CysAC) cells in nude mice

Table S1. Characteristics of human stomach donors

Table S2. Characteristics of gastric tumor patients

Table S3. List of primary antibodies for immunostaining

Data Availability Statement

All of the data for this study are contained within the paper and its supplementary files.