Abstract

Background and Objectives

Immune-mediated small fiber neuropathy (SFN) is increasingly recognized. Acute-onset SFN (AOSFN) remains poorly described. Herein, we report a series of AOSFN cases in which immune origins are debatable.

Methods

We included consecutive patients with probable or definite AOSFN. Diagnosis of SFN was based on the NEURODIAB criteria. Acute onset was considered when the maximum intensity and extension of both symptoms and signs were reached within 28 days. We performed the following investigations: clinical examination, neurophysiologic assessment encompassing a nerve conduction study to rule out large fiber neuropathy, laser-evoked potentials (LEPs), warm detection thresholds (WDTs), electrochemical skin conductance (ESC), epidermal nerve fiber density (ENF), and patient serum reactivity against mouse sciatic nerve teased fibers, mouse dorsal root ganglion (DRG) sections, and cultured DRG. The serum reactivity of healthy subjects (n = 10) and diseased controls (n = 12) was also analyzed. Data on baseline characteristics, biological investigations, and disease course were collected.

Results

Twenty patients presenting AOSFN were identified (60% women; median age: 44.2 years [interquartile range: 35.7–56.2]). SFN was definite in 18 patients (90%) and probable in 2 patients. A precipitating event was present in 16 patients (80%). The median duration of the progression phase was 14 days [5–28]. Pain was present in 17 patients (85%). Twelve patients (60%) reported autonomic involvement. The clinical pattern was predominantly non–length-dependent (85%). Diagnosis was confirmed by abnormal LEPs (60%), ENF (55%), WDT (39%), or ESC (31%). CSF analysis was normal in 5 of 5 patients. Antifibroblast growth factor 3 antibodies were positive in 4 of 18 patients (22%) and anticontactin-associated protein-2 antibodies in one patient. In vitro studies showed IgG immunoreactivity against nerve tissue in 14 patients (70%), but not in healthy subjects or diseased controls. Patient serum antibodies bound to unmyelinated fibers, Schwann cells, juxtaparanodes, paranodes, or DRG. Patients' condition improved after a short course of oral corticosteroids (3/3). Thirteen patients (65%) showed partial or complete recovery. Others displayed relapses or a chronic course.

Discussion

AOSFN primarily presents as an acute, non–length-dependent, symmetric painful neuropathy with a variable disease course. An immune-mediated origin has been suggested based on in vitro immunohistochemical studies.

Introduction

Small fiber neuropathies (SFNs) are characterized by preferential involvement of thinly myelinated Aδ-fibers and unmyelinated C-fibers.1 Immune-mediated SFNs are increasingly recognized2-5 and might be immunotherapy responsive.6,7

Diagnosis of SFN is challenging. Indeed, SFN diagnostic criteria regularly evolve8-10 but remain controversial.11 Among the NEURODIAB criteria, SFN is typically chronic length-dependent polyneuropathy.1,9 However, several phenotypes have been described, such as non–length-dependent SFN12 and acute-onset SFN (AOSFN).13

The clinical presentation of AOSFN may be initially misleading, characterized by isolated acute neuropathic pain or pure sensory symptoms, and normal nerve conduction studies.6,13-16 Descriptions of AOSFN are rare, mainly reported as single cases or small series without systematic investigations.6,13-20 Some AOSFNs are associated with the transient presence of antibodies of unknown specificity.15 We report a series of AOSFN cases with clinical, neurophysiologic, pathologic, and experimental assessment.

Methods

Patient Population

Between April 2017 and April 2022, we included all consecutive inpatients and outpatients referred to our tertiary neuromuscular center for AOSFN that is probable or definite SFN according to the NEURODIAB criteria,9 with a maximal 4-week onset.

All patients underwent a complete clinical examination, including evoked pain and thermal sensory assessment, by 2 neurologists (TG and AC). The diagnosis of probable SFN was based on the NEURODIAB criteria according to the presence of symptoms and clinical signs of small fiber damage in an anatomical distribution compatible with peripheral neuropathy and without any clinical or neurophysiologic signs of large fiber involvement.9 Indeed, patients were excluded if they presented any clinical signs of large fiber involvement (including ataxia, muscle weakness, proprioceptive impairment, or vibration sensation alteration) or abnormal nerve conduction study (NCS) at the time of the first investigation. Positive symptoms (neuropathic pain or paresthesia), negative symptoms (reduced or absent sensitivity to cold, heat, or noxious stimuli), positive signs of mechanical or thermal stimuli (allodynia or hyperalgesia), and negative signs (thermal or pain hypoesthesia) were considered compatible with small fiber involvement.

Acute onset was defined as the extension and maximal intensity of both symptoms and signs reached within 28 days.

A length-dependent pattern, based on patient history and clinical examination, was defined as predominant distal symmetric neuropathy, beginning at the feet and involving the fingers when it ascends up to the knees.21 Other patterns were considered non–length-dependent.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

This study was approved by an Independent Ethics Committee (CO-15-006; Bicêtre, December 18, 2015). All patients provided a written informed consent before participation.

Neurophysiologic Assessment

Large Fiber Assessment

Conventional electrodiagnostic studies, including NCS and needle EMG, were performed before inclusion and were normal for all patients.

Small Fiber Assessment

The laser-evoked potentials (LEPs) were used to assess the function of Aδ-fibers. LEPs were recorded by laser stimulation of the dorsum of the hands (radial nerve territory) and feet (superficial fibular nerve territory) on both sides using an ND:YAP laser (Stimul 1,340 laser, Electronic Engineering, Florence, Italy). Each stimulus consisted of a brief radiant heat pulse (laser beam diameter 4 mm, pulse duration 5 ms, energy progressively increased from 1.5 to 2.5J by steps of 0.25J, resulting in energy density between 120 and 200 mJ/mm2).22 Habituation, sensitization, and nociceptor fatigue were minimized by slightly moving the laser beam between stimuli. LEPs were recorded using a scalp electrode placed at Cz, according to the International 10–20 EEG System, referenced to the linked earlobes. A Velcro bracelet strapped around the left forearm was used as the ground electrode. The electrooculogram was recorded using pregelled surface adhesive electrodes placed at the right infraorbital lateral margin. Two blocks of 10–12 trials were performed, and the results were averaged offline. The signal was filtered (bandpass: 0.5–30 Hz), and trials contaminated by eye blinks, ocular movements (saccades), or any raw signal exceeding 70 μV were excluded from averaging. The N2-P2 complex was studied by measuring N2-P2 peak-to-peak amplitude and N2 latency. The LEPs were abnormal if latencies were above 170 ms at upper limbs (UL) or 237 ms at lower limbs (LL) or the amplitude was below 15 μV at UL or 13 μV at LL.

Quantitative sensory testing (QST) was performed on the dorsum of the hands and feet (the same territories used for LEPs). The detection thresholds for warm stimuli (WDT) were used to assess the function of the sensory C-fibers. We measured WDT using a 16 cm2 Peltier probe connected to a Thermal Sensory Analyzer TSA 2001 (Medoc, Ramat Yishai, Israel)23 and the method of limits.24 After an adaptation period at a neutral temperature of 32°C, the temperature increased (heating up to 50°C) at a linear rate of 1°C/s, until the patient pressed a signal button when they began to feel warm (‘first perception’ or ‘detection’ threshold). The detection thresholds (in °C) were determined as the average value from 3 trials and the absolute difference between the measured threshold and the neutral baseline temperature of 32°C. The WDT were abnormal if they were above 5.8°C at UL or 10.5°C at LL. These normative values have been established in a large number of healthy subjects and are evenly distributed for age and sex.25

Electrochemical skin conductance (ESC) was used to assess autonomic C-fibers. ESC was performed with Sudoscan® (Impeto Medical, Paris, France).26,27 The patient stood placing both palms and soles on large nickel electrode plates through which low-voltage direct current (less than 4 V) was delivered for 2 minutes. The electrodes were alternately used as anode and cathode, and the current between the electrodes was generated by reverse iontophoresis. The local conductance (in microsiemens, μS) was measured simultaneously at the 4 extremities from the electrochemical reaction between sweat chloride ions released by the sweat glands and the nickel electrode plates delivering the direct current. The ESC was considered abnormal if it was below 64 μS at the UL or 67 μS at the LL.

Pathologic Investigation

Epidermal innervation was assessed using 3-mm punch skin biopsies taken from the right calf (10 cm above the lateral malleolus) and the proximal lateral right thigh (20 cm below the anterosuperior iliac spine).28 The skin biopsies were fixed, cryoprotected, sectioned, and immunostained with polyclonal antibodies against panaxonal marker, protein gene product 9.5. Observers assessed the linear density/mm of ENF from 3 to 6 50-μm thick sections selected at random from each biopsy specimen. ENF was considered abnormal in the calf if it was below the fifth percentile values of previously published age-normative and sex-normative data.29 There were no normative data for ENF in the thigh. However, normal ENF in the thigh is reported to be 130% higher than the ENF in the calf.30 Therefore, we considered abnormal ENF in the thigh if it was below the fifth percentile values of previously published age-normative and sex-normative data for the calf or if it was below the value of ENF in the calf in the same patient (i.e., ENFthigh/ENFcalf ratio <1).

Amyloid staining was ruled out with a minor salivary gland biopsy in 9 patients.

Biological Investigation

The following tests were performed: complete blood count (20 patients), renal (20), liver (20) and thyroid (20) function tests, lipid screen (20), C-reactive protein (20), fasting blood glucose (20), glycosylated hemoglobin (20), antinuclear antibody (20), anti-SSA and SSB antibodies (19), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (14), serum immunofixation (19), cryoglobulin (7), hepatitis B and C titers (18), Lyme titer (15), HIV titer (18), vitamin B12 and folate levels (18), antitransglutaminase and antiendomysium antibodies (13), antithyroperoxydase (anti-TPO) and antithyroglobulin antibodies (anti-Tg) (7), antiganglioside antibodies (10), onconeural antibodies such as antiHu antibodies (13), anticontactin-associated protein-2 antibodies (anti-CASPR2, 20), antibodies targeting the node and the paranode of Ranvier [anticontactin-associated protein (anti-CASPR1), anticontactin (anti-CNTN1), antineurofascin 155 (anti-Nfasc155) antibodies, 20], antifibroblast growth factor 3 antibodies (anti-FGFR3, 18), genetic testing for TTR (5), genetic testing for SCN9A, SCN10A, and SCN11A (4), and CSF analyses (5).

Other Investigations

Spinal cord MRI was performed on 10 patients. Several patients underwent chest radiography and chest and abdominal tomography. History ruled out neurotoxic drugs, heavy metal intoxication, or occupational exposure.

Nerve and DRG Immunohistochemical Labeling

Sciatic nerve teased fibers and dorsal root ganglion (DRG) sections were prepared from adult C57BL/6J mice, as previously described.31 Tissues were postfixed with acetone for 10 minutes at −20°C, washed, blocked for 1 hour with blocking solution (5% fish skin gelatin, 0.1% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline), and then incubated overnight at 4°C with the patients' sera diluted at 1:200 and goat anticontactin-1 antibodies (1:2000; R&D Systems) to label paranodes or chicken antiperipherin antibodies (1:500; Aves Labs) to stain unmyelinated axons. The next day, the slides were washed 3 times and incubated for 1 hour with donkey anti-human IgG conjugated to Alexa 488, donkey anti-human IgM conjugated to Alexa 594, and donkey anti-goat IgG conjugated to Alexa 647 (1:500; Jackson Immunoresearch). The slides were mounted and counterstained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to stain the nuclei. Sera from healthy subjects (n = 10), patients with PMP22 duplication (n = 7), and patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (n = 5) were also analyzed.

Neuron-Based Assay

Cultured DRG were prepared from 1-month-old C57Bl/6J mice on 12-mm coverslips and maintained for 3 days in vitro. Live neurons were incubated with patients' sera diluted 1:50 in DMEM (Thermo Fisher) for 1 hour at 37°C, washed several times, and fixed for 20 minutes with 2% paraformaldehyde. The cells were permeabilized with blocking solution, incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with chicken antibodies against neurofilament heavy (1:2,000; Ab5539; Merck Millipore), and incubated with secondary antibodies. Sera from healthy subjects and diseased controls were also analyzed.

Statistical Analyses

We performed the descriptive analyses with Microsoft Excel. We calculated percentages for qualitative data and medians and interquartile ranges for quantitative data.

Data Availability

Data are available on request to the corresponding author.

Results

Clinical Features

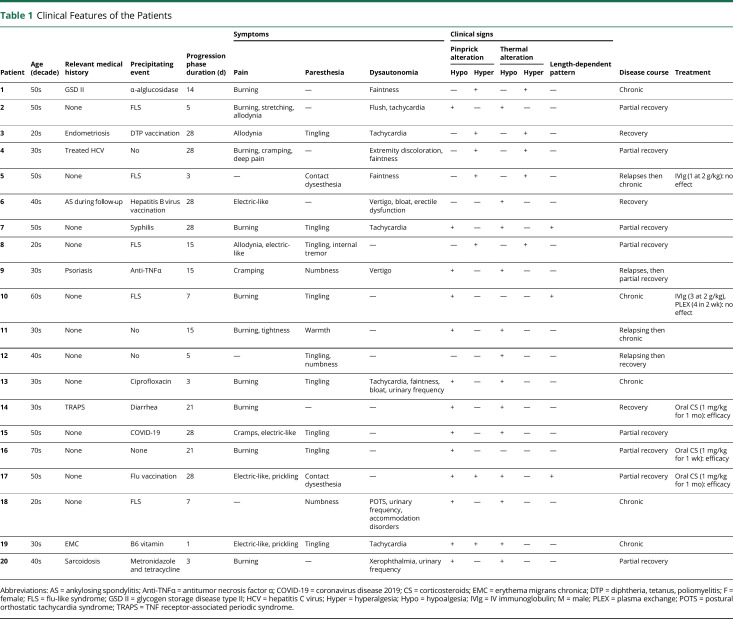

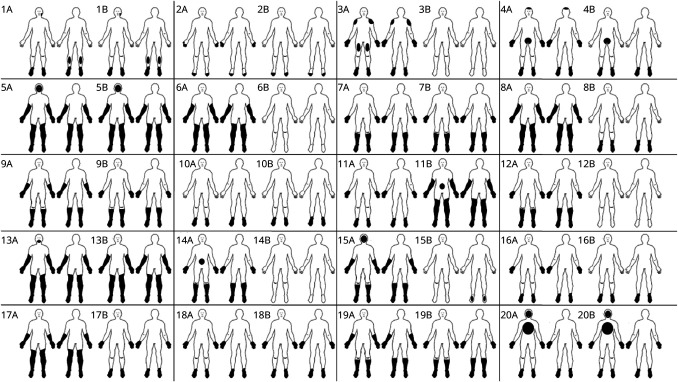

Twenty patients were included (60% women, median age [interquartile range] 44.2 years [35.7–56.2]). The clinical features of the patients are shown in Table 1. A precipitating event was present in 16 patients (80%): an infectious event in 8 [flu-like syndrome with negative Sars-Cov2 testing (5), syphilis (1), diarrhea (1), and COVID-19 (1)], a recently introduced treatment in 5 (antibiotics in 2, antitumor necrosis factor α, vitamin, enzyme replacement therapy), and vaccination (flu, hepatitis B virus, and diphtheria-tetanus-poliomyelitis) in 3. The median duration of the progression phase was 14 days [5–28]. Seventeen patients reported pain (85%). Paresthesia was observed in 14 patients (70%). The symptom distributions at onset and last follow-up are presented individually in Figure 1. Autonomic involvement was reported in 12 patients (60%), mainly faintness and tachycardia. Pinprick alteration was present in 18 patients (90%), including hypoalgesia in 11 patients, hyperalgesia in 5, or both in different sites in 2 patients. Responses to heat and cold were altered in 18 patients (90%), including hypoalgesia in 13 patients and hyperalgesia or allodynia in 5. The clinical pattern was not length-dependent in 17 patients (85%).

Table 1.

Clinical Features of the Patients

| Patient | Age (decade) | Relevant medical history | Precipitating event | Progression phase duration (d) | Symptoms | Clinical signs | Disease course | Treatment | ||||||

| Pain | Paresthesia | Dysautonomia | Pinprick alteration | Thermal alteration | Length-dependent pattern | |||||||||

| Hypo | Hyper | Hypo | Hyper | |||||||||||

| 1 | 50s | GSD II | α-alglucosidase | 14 | Burning | — | Faintness | — | + | — | + | — | Chronic | |

| 2 | 50s | None | FLS | 5 | Burning, stretching, allodynia | — | Flush, tachycardia | + | — | + | — | — | Partial recovery | |

| 3 | 20s | Endometriosis | DTP vaccination | 28 | Allodynia | Tingling | Tachycardia | — | + | — | + | — | Recovery | |

| 4 | 30s | Treated HCV | No | 28 | Burning, cramping, deep pain | — | Extremity discoloration, faintness | — | + | — | + | — | Partial recovery | |

| 5 | 50s | None | FLS | 3 | — | Contact dysesthesia | Faintness | — | + | — | + | — | Relapses then chronic | IVIg (1 at 2 g/kg): no effect |

| 6 | 40s | AS during follow-up | Hepatitis B virus vaccination | 28 | Electric-like | — | Vertigo, bloat, erectile dysfunction | — | — | + | — | — | Recovery | |

| 7 | 50s | None | Syphilis | 28 | Burning | Tingling | Tachycardia | + | — | + | — | + | Partial recovery | |

| 8 | 20s | None | FLS | 15 | Allodynia, electric-like | Tingling, internal tremor | — | — | + | — | + | — | Partial recovery | |

| 9 | 30s | Psoriasis | Anti-TNFα | 15 | Cramping | Numbness | Vertigo | + | — | + | — | — | Relapses, then partial recovery | |

| 10 | 60s | None | FLS | 7 | Burning | Tingling | — | + | — | — | — | + | Chronic | IVIg (3 at 2 g/kg), PLEX (4 in 2 wk): no effect |

| 11 | 30s | None | No | 15 | Burning, tightness | Warmth | — | + | — | + | — | — | Relapsing then chronic | |

| 12 | 40s | None | No | 5 | — | Tingling, numbness | — | — | — | + | — | — | Relapsing then recovery | |

| 13 | 30s | None | Ciprofloxacin | 3 | Burning | Tingling | Tachycardia, faintness, bloat, urinary frequency | + | — | + | — | — | Chronic | |

| 14 | 30s | TRAPS | Diarrhea | 21 | Burning | — | — | + | — | + | — | — | Recovery | Oral CS (1 mg/kg for 1 mo): efficacy |

| 15 | 50s | None | COVID-19 | 28 | Cramps, electric-like | Tingling | — | + | — | + | — | — | Partial recovery | |

| 16 | 70s | None | None | 21 | Burning | Tingling | — | + | — | — | — | — | Partial recovery | Oral CS (1 mg/kg for 1 wk): efficacy |

| 17 | 50s | None | Flu vaccination | 28 | Electric-like, prickling | Contact dysesthesia | — | + | + | + | — | + | Partial recovery | Oral CS (1 mg/kg for 1 mo): efficacy |

| 18 | 20s | None | FLS | 7 | — | Numbness | POTS, urinary frequency, accommodation disorders | + | — | + | — | — | Chronic | |

| 19 | 30s | EMC | B6 vitamin | 1 | Electric-like, prickling | Tingling | Tachycardia | + | + | + | — | — | Chronic | |

| 20 | 40s | Sarcoidosis | Metronidazole and tetracycline | 3 | Burning | — | Xerophthalmia, urinary frequency | + | — | + | — | — | Partial recovery | |

Abbreviations: AS = ankylosing spondylitis; Anti-TNFα = antitumor necrosis factor α; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; CS = corticosteroids; EMC = erythema migrans chronica; DTP = diphtheria, tetanus, poliomyelitis; F = female; FLS = flu-like syndrome; GSD II = glycogen storage disease type II; HCV = hepatitis C virus; Hyper = hyperalgesia; Hypo = hypoalgesia; IVIg = IV immunoglobulin; M = male; PLEX = plasma exchange; POTS = postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome; TRAPS = TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome.

Figure 1. Individual Distribution of Sensory Symptoms at the Peak and the Last Follow-Up.

Body diagrams representing the regional distribution of sensory symptoms at the peak (A) and last follow-up (B) for the front (left) and back (right) of 20 patients with acute-onset small fiber neuropathy. The numbers on the top left of each figure correspond to the patient numbers in Tables 1–3.

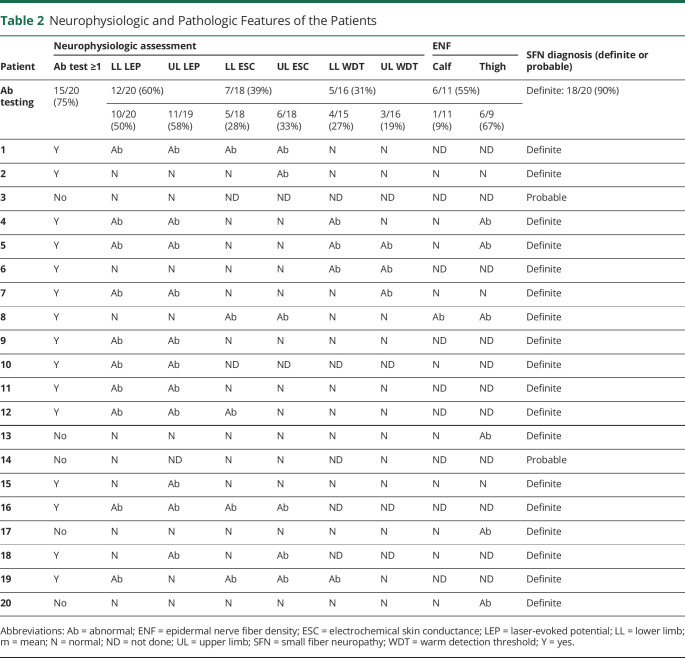

Diagnostic Evaluation

The neurophysiologic and pathologic features are presented in Table 2. All the patients underwent at least one neurophysiologic test. These tests showed evidence of small fiber involvement in 15 patients (75%). The recording of LEPs was the most sensitive test (60%). The sensitivities of WDT and ESC were lower (39% and 31%). Among the 5 patients with normal neurophysiologic findings, patient 3 was assessed after spontaneous complete recovery of symptoms. Eleven patients underwent skin biopsies. ENF was reduced in 6 patients (55%). Five patients had normal ENF in the calf but exclusively reduced in the thigh. Therefore, considering both neurophysiologic studies and ENF, SFN was definite in 18 patients (90%) and remained probable in 2 patients.

Table 2.

Neurophysiologic and Pathologic Features of the Patients

| Patient | Neurophysiologic assessment | ENF | SFN diagnosis (definite or probable) | |||||||

| Ab test ≥1 | LL LEP | UL LEP | LL ESC | UL ESC | LL WDT | UL WDT | Calf | Thigh | ||

| Ab testing | 15/20 (75%) | 12/20 (60%) | 7/18 (39%) | 5/16 (31%) | 6/11 (55%) | Definite: 18/20 (90%) | ||||

| 10/20 (50%) | 11/19 (58%) | 5/18 (28%) | 6/18 (33%) | 4/15 (27%) | 3/16 (19%) | 1/11 (9%) | 6/9 (67%) | |||

| 1 | Y | Ab | Ab | Ab | Ab | N | N | ND | ND | Definite |

| 2 | Y | N | N | N | Ab | N | N | N | N | Definite |

| 3 | No | N | N | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | Probable |

| 4 | Y | Ab | Ab | N | N | Ab | N | N | Ab | Definite |

| 5 | Y | Ab | Ab | N | N | Ab | Ab | N | Ab | Definite |

| 6 | Y | N | N | N | N | Ab | Ab | ND | ND | Definite |

| 7 | Y | Ab | Ab | N | N | N | Ab | N | N | Definite |

| 8 | Y | N | N | Ab | Ab | N | N | Ab | Ab | Definite |

| 9 | Y | Ab | Ab | N | N | N | N | ND | ND | Definite |

| 10 | Y | Ab | Ab | ND | ND | ND | ND | N | ND | Definite |

| 11 | Y | Ab | Ab | N | N | N | N | ND | ND | Definite |

| 12 | Y | Ab | Ab | Ab | N | N | N | ND | ND | Definite |

| 13 | No | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Ab | Definite |

| 14 | No | N | ND | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND | Probable |

| 15 | Y | N | Ab | N | N | N | N | N | N | Definite |

| 16 | Y | Ab | Ab | Ab | Ab | ND | ND | ND | ND | Definite |

| 17 | No | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Ab | Definite |

| 18 | Y | N | Ab | N | Ab | ND | ND | N | ND | Definite |

| 19 | Y | Ab | N | Ab | Ab | Ab | N | ND | ND | Definite |

| 20 | No | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Ab | Definite |

Abbreviations: Ab = abnormal; ENF = epidermal nerve fiber density; ESC = electrochemical skin conductance; LEP = laser-evoked potential; LL = lower limb; m = mean; N = normal; ND = not done; UL = upper limb; SFN = small fiber neuropathy; WDT = warm detection threshold; Y = yes.

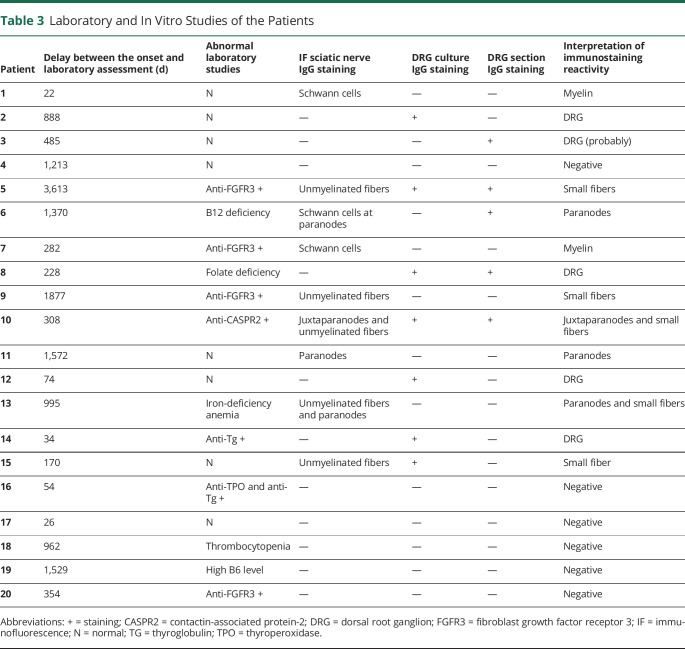

Immunologic Studies

CSF analyses revealed normal white cell counts and protein levels in all 5 tested patients. Oligoclonal bands were absent in one patient. One patient tested negative for CSF onconeural and neural surface antibodies.

Abnormal laboratory results and immunologic features of the patients are presented in Table 3. Anti-CASPR2 IgG antibodies were present in 1 of 20 patients, as we previously reported.32 Anti-FGFR3 IgG antibodies were positive for 4 of 18 patients. Two of the 7 tested patients had antithyroid antibodies.

Table 3.

Laboratory and In Vitro Studies of the Patients

| Patient | Delay between the onset and laboratory assessment (d) | Abnormal laboratory studies | IF sciatic nerve IgG staining |

DRG culture IgG staining | DRG section IgG staining | Interpretation of immunostaining reactivity |

| 1 | 22 | N | Schwann cells | — | — | Myelin |

| 2 | 888 | N | — | + | — | DRG |

| 3 | 485 | N | — | — | + | DRG (probably) |

| 4 | 1,213 | N | — | — | — | Negative |

| 5 | 3,613 | Anti-FGFR3 + | Unmyelinated fibers | + | + | Small fibers |

| 6 | 1,370 | B12 deficiency | Schwann cells at paranodes | — | + | Paranodes |

| 7 | 282 | Anti-FGFR3 + | Schwann cells | — | — | Myelin |

| 8 | 228 | Folate deficiency | — | + | + | DRG |

| 9 | 1877 | Anti-FGFR3 + | Unmyelinated fibers | — | — | Small fibers |

| 10 | 308 | Anti-CASPR2 + | Juxtaparanodes and unmyelinated fibers | + | + | Juxtaparanodes and small fibers |

| 11 | 1,572 | N | Paranodes | — | — | Paranodes |

| 12 | 74 | N | — | + | — | DRG |

| 13 | 995 | Iron-deficiency anemia | Unmyelinated fibers and paranodes | — | — | Paranodes and small fibers |

| 14 | 34 | Anti-Tg + | — | + | — | DRG |

| 15 | 170 | N | Unmyelinated fibers | + | — | Small fiber |

| 16 | 54 | Anti-TPO and anti-Tg + | — | — | — | Negative |

| 17 | 26 | N | — | — | — | Negative |

| 18 | 962 | Thrombocytopenia | — | — | — | Negative |

| 19 | 1,529 | High B6 level | — | — | — | Negative |

| 20 | 354 | Anti-FGFR3 + | — | — | — | Negative |

Abbreviations: + = staining; CASPR2 = contactin-associated protein-2; DRG = dorsal root ganglion; FGFR3 = fibroblast growth factor receptor 3; IF = immunofluorescence; N = normal; TG = thyroglobulin; TPO = thyroperoxidase.

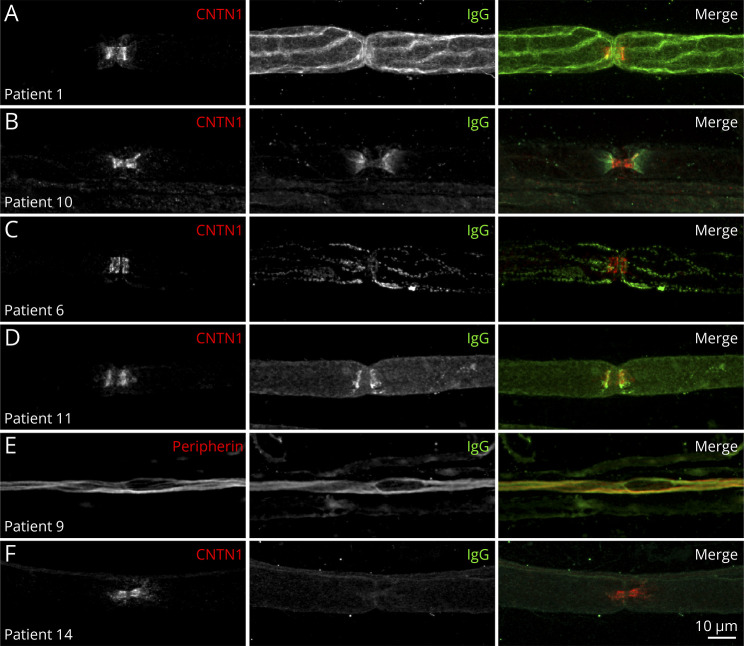

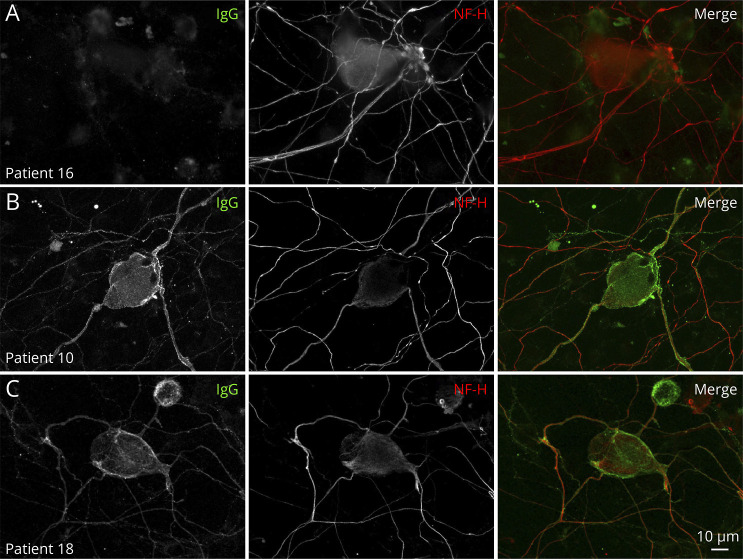

In vitro studies revealed mouse sciatic nerve fiber or DRG immunostaining with the sera from 14 patients (70%). Immunostaining was not observed with sera from either healthy subjects or diseased controls. Immunostaining was obtained only with anti-IgG, but not with anti-IgM antibodies. Different immunostaining patterns in sciatic nerve fibers and DRG are shown in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. The sera from 3 patients contained antibodies that lead to paranodal immunostaining of Schwann cells (No. 6) or axons (Nos. 11 and 13). The serum from patient No. 10 had antibodies that caused juxtaparanode immunostaining, consistent with not only circulating anti-CASPR2 antibodies but also unmyelinated fiber immunostaining.32 The sera from 5 patients lead to unmyelinated fiber immunostaining. The sera from a total of 5 of the tested patients contained antibodies for DRG.

Figure 2. Patterns of Nerve Fiber Staining.

This figure shows teased fibers from mouse sciatic nerves immunostained with patient IgG (green), goat anti-contactin-1 IgG (CNTN1; red) to localize to the node of Ranvier (A, B, C, D, F), or chicken antiperipherin IgG (red) to localize unmyelinated axons (E). IgG deposition was observed on Schwann cells (A), at the juxtaparanodes in patients with circulating anti-CASPR2 antibodies (B), on the surface of Schwann cells near the paranodal region (C), at paranodes (D), or on unmyelinated fibers (E). IgG deposition was not observed in some patients (F). Scale bar: 10 µm.

Figure 3. Patterns of Cultured Dorsal Root Ganglion Staining.

Live dorsal root ganglia (DRG) were incubated with patient sera, fixed, and immunostained for human IgG (green) and antibodies against neurofilament heavy (NF-H; red) to stain DRG. Some patients did not show reactivity toward the DRG (A). Other patients showed strong IgG reactivity against surface antigens expressed by both large and small cells in DRG (B-C). Patient No. 10, who presented with circulating anti-CASPR2 antibodies, showed strong reactivity against the soma and axons of the DRG (B). Patient No. 8, without any identified antibody target, also showed strong reactivity against the DRG soma and axons (C). Scale bar: 10 µm.

Disease Course and Treatment Response

The disease course varied (Table 1). Thirteen patients (65%) reported recovery of symptoms, complete in 4 patients, or partial in 9. Five patients (25%) experienced a steady and chronic course after an acute onset. Four patients (20%) reported relapses, followed by a chronic clinical condition in 2, complete recovery in one, and partial recovery in one. Three patients received a 1-month course of oral corticosteroids at 1 mg/kg during the acute phase and presented with complete or partial recovery. Two patients received IV immunoglobulin (IVIg) after the acute phase, without any efficacy. Patient No. 10, with anti-CASPR2 antibodies, also underwent plasma exchange without any efficacy. None of the 20 patients had developed large fiber involvement at the last follow-up (median 4.8 years [3.2–8.0]).

Discussion

We report a series of AOSFN cases with 20 patients collected over 5 years from a tertiary center, suggesting that it is a rare condition. To date, only a few small series have been reported ranging from one to 6 patients, some of which are them restricted to postvaccinal or postinfectious contexts (eTable 1, links.lww.com/NXI/A972).6,13-20 In the present series, we draw a picture of AOSFN, including clinical, neurophysiologic, pathologic, and experimental features. Patients with AOSFN have variable disease courses, and one-third of patients have unfavorable outcomes. In vitro analyses provided arguments for a possible immune-mediated process.

The diagnosis of AOSFN may be challenging in clinical practice. Patients usually present with acute symmetric non–length-dependent neuropathic pain, frequently preceded by a particular event, such as infection or vaccination. In a previous cohort of non–length-dependent SFN, one-third of patients had an acute onset.12 However, patients may be painless, as in other SFN presentations.33 During the acute phase, the absence of large fiber involvement on clinical examination and NCS study ruled out acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy.34 In addition, we found normal CSF while results were more discrepant in previous studies.6,13-15 Functional neurologic disorders should be considered in the context of a predominantly painful presentation with normal investigations. Indeed, patients with functional neurologic disorders frequently present subjective symptoms potentially mimicking SFN.35 However, this was not the case in our series of patients who presented clinical signs of sensory disorders and abnormal neurophysiologic or neuropathologic findings, leading to the diagnosis of definite SFN in 90% of patients. Two patients were diagnosed with probable SFN because their neurophysiologic findings were normal, but a skin biopsy was unfortunately not performed. In this study, we used a battery of neurophysiologic tests to assess Aδ and C sensory fibers and C autonomic fibers. In previously published series, neurophysiologic assessment was rarely performed or limited to a single test. Interestingly, LEPs have been the most sensitive indicator of SFN. By contrast, thermal QST and ESC exhibited poor sensitivity, below 40%. This is consistent with our previously published data on the sensitivity of neurophysiologic tests for diagnosing SFN.25 By contrast, ENF was reduced more often in the thigh than in the calf, which is consistent with non–length-dependent neuropathy. In this context, other laboratory tests investigating small nerve fibers would have been useful to perform, such as corneal confocal microscopy.36 Symptoms associated with small nerve fibers involvement, such as pain, can be explained not only by lesions of these fibers but also by their dysfunction (leading to nerve hyperexcitability37) or a combination of these phenomena.38 Thus, the normality of neuropathologic and neurophysiologic investigations cannot rule out the involvement of small fibers in a clinical picture characterized by only positive sensory symptoms. In this series, the patients had variable disease courses which require caution to differentiate relapses from functional neurologic fluctuations. The heterogeneity of the disease course is usual in acute-onset inflammatory neuropathies affecting large-diameter fibers. AOSFN may have complete recovery or sequelae, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome,39 or may be the onset of chronic neuropathy, such as acute-onset chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy.40 One cannot exclude that patients may later develop an associated large-fiber involvement, although the median follow-up was 4.8 years in this study. The proportion of patients with an unfavorable course may be overestimated because our hospital is a tertiary neuromuscular center. Therefore, patients with AOSFN whose symptoms had complete and rapid resolution may not have benefited from neurologic evaluation at our center, which may have been requested for patients with a more prolonged course of the disease.

This investigation suggests that immune dysfunction is probably the cause of AOSFN. A precipitating event was frequently found, either infection or vaccination, as in previous series of AOSFN,13-16,19,20 as well as other types of immune neuropathies, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome39 or post-COVID neuropathy.41,42 In 3 patients with AOSFN, their sera showed transient immunoreactivity to murine small fibers during the acute phase.15 The present in vitro studies are also compatible with antibody-associated pathophysiology. Indeed, in vitro studies demonstrated IgG immunostaining by the sera of most patients with AOSFN. Although heterogeneous binding sites suggest nonspecific findings, the absence of immunostaining from the sera of healthy subjects or diseased controls supports an immune-mediated process in AOSFN. Patient sera contained antibodies to unmyelinated or thinly myelinated fibers, including the paranodal region, and DRGs. IgG deposits on nerves have also been found in other types of chronic inflammatory neuropathy.43 However, one cannot exclude the possibility that these immunoreactions were a consequence of peripheral nervous system lesions and not the cause of these lesions. Indeed, an antibody probably responsible for the occurrence of AOSFN was identified in only one previously reported patient with CASPR2-related juxtaparanodopathy, which exclusively involved small nerve fibers.32,44 The number of autoantibodies associated with SFN has increased in recent years, including anti-TS-HDS and anti-FGFR-3 antibodies which have been associated with AOSFN in some cases.3,45 However, their pathogenicity in SFN remains uncertain.46 Moreover, we observed IgG cell membrane immunostaining. This contrasts with the reported anti-TS-HDS antibodies which are IgM.3 It also contrasts with anti-FGFR-3 IgG antibodies which usually target the intracellular portion of FGFR-3.47 Thus, the extracellular immunostaining pattern in this study is not consistent with anti-FGFR-3 antibody reactivity, despite circulating anti-FGFR-3 antibodies being identified in 20% of our patients. Anti-plexin D1 IgG antibodies seem to be frequently found in painful neuropathies in Japanese patients2,48 and induce hyperexcitability of DRG sensory neurons.49 It would be interesting to look for the presence of antiplexin D1 antibodies, notably in patients with immunostaining involving DRG. Our in vitro studies did not reveal signs of autoimmunity in some patients. However, patients' sera were collected several months after the disease onset, and this may have led to missing a transient immune process.15 Finally, although paraneoplastic neuropathies were excluded from our series on the basis of the negativity of onconeural antibodies and clinical follow-up, such a cause could be possibly encountered in a context of AOSFN, even if we lack data to make this assumption.

In conclusion, the present cohort supports the concept of AOSFN and refines its clinical description. The typical clinical pattern is associated with acute non–length-dependent symmetric painful neuropathy with a monophasic or relapsing chronic course. In vitro studies have provided clues regarding immune pathogenesis. Regarding treatment, corticosteroids in the acute phase could have a beneficial effect, whereas IVIg infusions were ineffective in 2 patients who were treated for chronic symptoms long after the acute phase.

Glossary

- AOSFN

acute-onset SFN

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- ENF

epidermal nerve fiber density

- ESC

electrochemical skin conductance

- LEP

laser-evoked potential

- NCS

nerve conduction study

- QST

quantitative Sensory Testing

- SFN

small fiber neuropathy

- WDT

warm detection threshold

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Thierry Gendre, MD | Service de Neurologie, CHU Henri Mondor APHP, Créteil; Centre de Référence des Maladies Neuromusculaires Nord/Est/Ile-de-France | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Jean-Pascal Lefaucheur, MD, PhD | Centre de Référence des Maladies Neuromusculaires Nord/Est/Ile-de-France; Unité de Neurophysiologie Clinique, CHU Henri Mondor APHP; Unité de Recherche EA 4391, Faculté de Santé, Université Paris Est Créteil, France | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Tarik Nordine, MD | Centre de Référence des Maladies Neuromusculaires Nord/Est/Ile-de-France; Unité de Neurophysiologie Clinique, CHU Henri Mondor APHP; Unité de Recherche EA 4391, Faculté de Santé, Université Paris Est Créteil, France | Major role in the acquisition of data; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Yasmine Baba-Amer, PhD | IMRB INSERM U955-Equipe 10, Université Paris Est Créteil, France | Major role in the acquisition of data |

| François-Jérôme Authier, MD, PhD | Centre de Référence des Maladies Neuromusculaires Nord/Est/Ile-de-France; IMRB INSERM U955-Equipe 10, Université Paris Est Créteil; Service d’Anatomo-Pathologie, CHU Henri Mondor APHP, Créteil, France | Major role in the acquisition of data |

| Jérôme Devaux, PhD | Institut de Génomique Fonctionnelle, Université de Montpellier, CNRS, INSERM, France | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Alain Créange | Service de Neurologie, CHU Henri Mondor APHP, Créteil; Centre de Référence des Maladies Neuromusculaires Nord/Est/Ile-de-France; Unité de Recherche EA 4391, Faculté de Santé, Université Paris Est Créteil, France | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

Study Funding

The authors report no targeted funding.

Disclosure

T. Gendre received consulting fees from Alnylam, symposium fees from ArgenX, and supports for congress from Alnylam, Pfizer, LFB, CSL Behring, and Elivie. J.P. Lefaucheur reports no conflict of interest. T. Nordine reports no conflict of interest. Y. Baba-Amer reports no conflict of interest. F.J. Authier reports no conflict of interest. J. Devaux received a research grant form CSL Behring and is conducting a research contract with ArgenX. A. Créange received grants and nonfinancial support from Medday, personal fees from Merck, grants and personal fees from Alexion, Biogen, Novartis, and Roche outside the submitted work. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Terkelsen AJ, Karlsson P, Lauria G, Freeman R, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS. The diagnostic challenge of small fibre neuropathy: clinical presentations, evaluations, and causes. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(11):934-944. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30329-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujii T, Yamasaki R, Iinuma K, et al. A novel autoantibody against Plexin D1 in patients with neuropathic pain. Ann Neurol. 2018;84(2):208-224. doi: 10.1002/ana.25279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine TD, Kafaie J, Zeidman LA, et al. Cryptogenic small‐fiber neuropathies: serum autoantibody binding to trisulfated heparan disaccharide and fibroblast growth factor receptor‐3. Muscle Nerve. 2020;61(4):512-515. doi: 10.1002/mus.26748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tiwana HK, Lawson VH. Green shoots but deep roots: new antibodies in small fiber neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2020;61(4):433-435. doi: 10.1002/mus.26818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu M, Bennett DLH, Querol LA, et al. Pain and the immune system: emerging concepts of IgG-mediated autoimmune pain and immunotherapies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(2):177-188. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dabby R, Gilad R, Sadeh M, Lampl Y, Watemberg N. Acute steroid responsive small-fiber sensory neuropathy: a new entity? J Peripher nervous Syst. 2006;11(1):47-52. doi: 10.1111/j.1085-9489.2006.00062.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu X, Treister R, Lang M, Oaklander AL. IVIg for apparently autoimmune small-fiber polyneuropathy: first analysis of efficacy and safety. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2018;11:1756285617744484. doi: 10.1177/1756285617744484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devigili G, Tugnoli V, Penza P, et al. The diagnostic criteria for small fibre neuropathy: from symptoms to neuropathology. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 7):1912-1925. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tesfaye S, Boulton AJM, Dyck PJ, et al. Diabetic neuropathies: update on definitions, diagnostic criteria, estimation of severity, and treatments. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(10):2285-2293. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freeman R, Gewandter JS, Faber CG, et al. Idiopathic distal sensory polyneuropathy: ACTTION diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 2020;95(22):1005-1014. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haroutounian S, Todorovic MS, Leinders M, et al. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic small fiber neuropathy: a systematic review. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(2):170-177. doi: 10.1002/mus.27070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorson KC, Herrmann DN, Thiagarajan R, et al. Non-length dependent small fibre neuropathy/ganglionopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(2):163-169. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.128801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seneviratne U, Gunasekera S. Acute small fibre sensory neuropathy: another variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72(4):540-542. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.4.540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Souayah N, Ajroud-Driss S, Sander HW, Brannagan TH, Hays AP, Chin RL. Small fiber neuropathy following vaccination for rabies, varicella or Lyme disease. Vaccine. 2009;27(52):7322-7325. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.09.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuki N, Chan AC, Wong AHY, et al. Acute painful autoimmune neuropathy: a variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2018;57(2):320-324. doi: 10.1002/mus.25738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbott MG, Allawi Z, Hofer M, et al. Acute small fiber neuropathy after Oxford-AstraZeneca ChAdOx1-S vaccination: a report of three cases and review of the literature. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2022;27(4):325-329. doi: 10.1111/jns.12509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paticoff J, Valovska A, Nedeljkovic SS, Oaklander AL. Defining a treatable cause of erythromelalgia: acute adolescent autoimmune small-fiber axonopathy. Anesth Analg. 2007;104(2):438-441. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000252965.83347.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyazaki Y, Koike H, Ito M, et al. Acute superficial sensory neuropathy with generalized anhidrosis, anosmia, and ageusia. Muscle Nerve. 2011;43(2):286-288. doi: 10.1002/mus.21865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kafaie J, Kim M, Krause E. Small fiber neuropathy following vaccination. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2016;18(1):37-40. doi: 10.1097/CND.0000000000000130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faignart N, Nguyen K, Soroken C, et al. Acute monophasic erythromelalgia pain in five children diagnosed as small-fiber neuropathy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2020;28:198-204. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2020.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willison HJ, Winer JB. Clinical evaluation and investigation of neuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(suppl 2):ii3-ii8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.suppl_2.ii3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lefaucheur J-P, Abbas SA, Lefaucheur-Ménard I, et al. Small nerve fiber selectivity of laser and intraepidermal electrical stimulation: a comparative study between glabrous and hairy skin. Neurophysiol Clin Clin Neurophysiol. 2021;51(4):357-374. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2021.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yarnitsky D, Sprecher E. Thermal testing: normative data and repeatability for various test algorithms. J Neurol Sci. 1994;125(1):39-45. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)90239-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fruhstorfer H, Lindblom U, Schmidt WC. Method for quantitative estimation of thermal thresholds in patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1976;39(11):1071-1075. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.39.11.1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lefaucheur J-P, Wahab A, Planté-Bordeneuve V, et al. Diagnosis of small fiber neuropathy: a comparative study of five neurophysiological tests. Neurophysiol Clin Neurophysiol. 2015;45(6):445-455. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2015.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayaudon H, Miloche P-O, Bauduceau B. A new simple method for assessing sudomotor function: relevance in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2010;36(6 Pt 1):450-454. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2010.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gin H, Baudoin R, Raffaitin CH, Rigalleau V, Gonzalez C. Non-invasive and quantitative assessment of sudomotor function for peripheral diabetic neuropathy evaluation. Diabetes Metab. 2011;37(6):527-532. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2011.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lauria G, Cornblath DR, Johansson O, et al. EFNS guidelines on the use of skin biopsy in the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy. Eur J Neurol. 2005:12(10):747-758. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01260.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lauria G, Bakkers M, Schmitz C, et al. Intraepidermal nerve fiber density at the distal leg: a worldwide normative reference study. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2010;15(3):202-207. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2010.00271.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Umapathi T, Tan WL, Tan NCK, Chan YH. Determinants of epidermal nerve fiber density in normal individuals. Muscle Nerve. 2006;33(6):742-746. doi: 10.1002/mus.20528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lonigro A, Devaux JJ. Disruption of neurofascin and gliomedin at nodes of Ranvier precedes demyelination in experimental allergic neuritis. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 1):260-273. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gendre T, Lefaucheur J, Devaux J, Créange A. A patient with distal lower extremity neuropathic pain and anti‐contactin‐associated protein‐ 2 antibodies. Muscle Nerve. 2021;64(3):E15-E17. doi: 10.1002/mus.27364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Devigili G, Rinaldo S, Lombardi R, et al. Diagnostic criteria for small fibre neuropathy in clinical practice and research. Brain. 2019;142(12):3728-3736. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oh SJ, LaGanke C, Claussen GC. Sensory Guillain-Barré syndrome. Neurology. 2001;56(1):82-86. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stone J, Vermeulen M. Functional sensory symptoms. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;139:271-281. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801772-2.00024-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gemignani F, Ferrari G, Vitetta F, Giovanelli M, Macaluso C, Marbini A. Non-length-dependent small fibre neuropathy. Confocal microscopy study of the corneal innervation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(7):731-733. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.177303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Serra J, Bostock H, Solà R, et al. Microneurographic identification of spontaneous activity in C-nociceptors in neuropathic pain states in humans and rats. PAIN. 2012;153(1):42-55. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finnerup NB, Kuner R, Jensen TS. Neuropathic pain: from mechanisms to treatment. Physiol Rev. 2021;101(1):259-301. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shahrizaila N, Lehmann HC, Kuwabara S. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Lancet. 2021;397(10280):1214-1228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00517-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruts L, Drenthen J, Jacobs BC, van Doorn PA, Dutch GBS Study Group. Distinguishing acute-onset CIDP from fluctuating Guillain-Barre syndrome: a prospective study. Neurology. 2010;74(21):1680-1686. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e07d14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dalakas MC. Guillain-Barré syndrome: the first documented COVID-19-triggered autoimmune neurologic disease: more to come with myositis in the offing. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020;7(5):e781. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oaklander AL, Mills AJ, Kelley M, et al. Peripheral neuropathy evaluations of patients with prolonged long COVID. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2022;9(3):e1146. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000001146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dalakas MC, Engel WK. Immunoglobulin and complement deposits in nerves of patients with chronic relapsing polyneuropathy. Arch Neurol. 1980;37(10):637-640. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1980.00500590061010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramanathan S, Tseng M, Davies AJ, et al. Leucine‐rich Glioma‐Inactivated 1 versus contactin‐associated protein‐like 2 antibody neuropathic pain: clinical and biological comparisons. Ann Neurol. 2021;90(4):683-690. doi: 10.1002/ana.26189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tholance Y, Moritz CP, Rosier C, et al. Clinical characterisation of sensory neuropathy with anti-FGFR3 autoantibodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(1):49-57. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2019-321849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chompoopong P, Rezk M, Mirman I, et al. TS-HDS autoantibody: clinical characterization and utility from real-world tertiary care center experience. J Neurol. 2023;270(9):4523-4528. doi: 10.1007/s00415-023-11798-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tholance Y, Antoine J-C, Mohr L, et al. Anti-FGFR3 antibody epitopes are functional sites and correlate with the neuropathy pattern. J Neuroimmunol. 2021;361:577757. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2021.577757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fujii T, Yamasaki R, Miyachi Y, Iinuma K, Kira J. Anti‐plexin D1 antibody–mediated neuropathic pain. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2020;11(S1):48-52. doi: 10.1111/cen3.12570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fujii T, Lee E-J, Miyachi Y, et al. Antiplexin D1 antibodies relate to small fiber neuropathy and induce neuropathic pain in animals. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021;8(5):e1028. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000001028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request to the corresponding author.