Abstract

A Bacteroides fragilis mutant resistant to hydrogen peroxide and alkyl peroxide was isolated by enrichment in increasing concentrations of hydrogen peroxide. The mutant strain was constitutively resistant to 100 mM H2O2 and 5 mM cumene hydroperoxide (15-min exposure). In contrast, the parent strain was protected against <10 mM H2O2 when the peroxide response was induced with a sublethal concentration of H2O2, and no protection was observed in untreated cells. In addition, catalase activity in the mutant strain was not repressed in anaerobic cultures as reported previously for the parent strain. Comparison of the protein profile of crude extracts of the B. fragilis strains revealed that at least three oxidative stress-induced proteins in the parent strain were constitutively expressed in the mutant as detected by nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. N-terminal amino acid sequence of these overexpressed proteins confirmed the presence of a deregulated catalase (KatB), an alkyl hydroperoxidase reductase subunit C (AhpC), and a Dps/PexB homologue. Northern blot analysis and katB::cat transcriptional fusion studies revealed that in the mutant, katB was deregulated compared to the parent and that katB was controlled by a trans-acting regulatory mechanism. Moreover, constitutive expression of KatB and of the AhpC and Dps homologues in the H2O2-resistant mutant suggests that these proteins may share a common oxidative stress transcriptional regulator and may be involved in B. fragilis peroxide resistance.

Microorganisms have developed highly efficient mechanisms that allow them to adapt rapidly and survive a variety of physical and chemical stress conditions such as oxygen availability, redox potential, temperature, pH, and osmolarity (33). One of these adaptations is the utilization of molecular oxygen as a final electron acceptor when facultative bacteria are shifted from anaerobic to aerobic conditions (45). Consequently, during aerobic growth, generation of the reactive oxygen species (ROS) superoxide anion (O2−) and of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is unavoidable, and the highly reactive oxidant hydroxyl radical (OH·) also may be formed through the Fenton reaction of H2O2 with free transition metals such as ferrous iron (14). ROS are potent cellular oxidizing agents that damage proteins, membrane lipids, and DNA (14, 19, 40). To minimize this damage, microorganisms eliminate the harmful effect of oxygen by-products by the synthesis of ROS-scavenging enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, catalases, and peroxidases, oxidative damage-repairing enzymes, and other proteins with unknown functions (14, 40).

One important aspect of this ROS response is that treatment of facultative and aerobic bacteria with sublethal concentrations of H2O2 induces a protection of the cells against levels of H2O2 that would be otherwise lethal (4, 9, 10, 25). This peroxide response in Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli results in the synthesis of at least 30 proteins, of which 9 are under OxyR regulatory control. These include catalase (KatG), alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpCF), glutathione reductase (GorA), and a nonspecific DNA-binding protein (Dps/PexB) involved in protection of DNA against oxidative damage (1, 14, 20). Similarly, in response to both oxidative stress and stationary phase, Bacillus subtilis induces the synthesis of KatA, AhpCF, Dps and MrgA, an oxidative stress and metalloregulated Dps homologue (3, 8, 17).

Generally there is a paucity of information about the adaptive mechanisms that confer aerotolerance and survival of anaerobic bacteria in the presence of either oxygen or ROS. However, induction of an oxidative stress response has been shown to occur in the aerotolerant opportunistic human pathogen Bacteroides fragilis (29, 35, 37). B. fragilis is among the most aerotolerant of anaerobic bacteria and is able to resist the presence of molecular oxygen for up to 2 to 3 days without a significant loss of viability (32, 42). This aerotolerance is dependent on the ability to synthesize new proteins immediately following a shift to aerobic conditions or treatment with sublethal concentrations of H2O2 (29, 35, 37). At least 28 newly synthesized proteins are induced upon oxygen exposure or addition of exogenous H2O2 to mid-log-phase anaerobic cultures. Among these oxidative stress induced proteins are the ROS-scavenging enzymes catalase KatB (29) and superoxide dismutase (16), but the mechanism(s) regulating the synthesis of these proteins is not understood. Recently, we have shown that expression of the B. fragilis katB gene is transcriptionally regulated by oxidative stress and by carbon and energy limitation in the absence of oxygen (30). Investigations of the regulatory mechanisms as well as the roles that these proteins play in the aerotolerance of B. fragilis have led us to the isolation of a constitutive H2O2-resistant mutant. In this study, we present physiological and genetics analysis of this mutant which contribute to our understanding of the gene(s) involved and the regulation of inducible protection against peroxides in aerotolerant anaerobic bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

B. fragilis 638R (27) was grown anaerobically in brain heart infusion broth supplemented with hemin, cysteine, and NaHCO3 (BHIS) for routine cultures (38). Cultures were also grown in chemically defined medium (44) for some enzyme analysis in crude extracts.

Killing assays.

Induction of the peroxide stress response with a sublethal concentration of H2O2 was carried out as follows. Mid-log-phase cells grown in BHIS to an A550 of 0.3 (approximately 2 × 108 to 4 × 108 cells/ml) were pretreated with 150 μM 2,2′-bipyridyl and 50 μM H2O2 for 15 min followed by a second addition of 50 μM H2O2 for 15 min. Treatment with bipyridyl was shown to be necessary for accurate viable counts (29). Then the cultures were split in 10-ml aliquots and challenged with H2O2 ranging from 0 to 100 mM for 15 min. For studies with cumene hydroperoxide (CHP), the cultures were pretreated as described above, and then CHP (in dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) was added to final concentration of 0 to 5 mM. To determine viable counts, treated cultures were diluted in brain heart infusion broth containing 150 μM 2,2′-bipyridyl and 10 μg of bovine liver catalase per ml, plated on BHIS agar, and incubated for 3 to 5 days at 37°C. All procedures were performed within an anaerobic chamber. Exposure of anaerobic cultures to aerobic conditions was carried out as previously described (29).

Mutant selection.

The procedure for isolation of the H2O2-resistant mutant described in this study was a modification of the continuous enrichment/selection method described by Hartford and Dowds (17). Briefly, B. fragilis 638R was grown in 10 ml of BHIS to approximately 2 × 108 to 4 × 108 cells/ml, treated with 10 mM H2O2 for 15 min, and then plated on BHIS agar for 24 to 48 h. One of the surviving clones was grown overnight in BHIS containing 10 mM H2O2. The resulting culture then was successively passaged overnight in BHIS containing 20, 30, 40, and then 50 mM H2O2. The B. fragilis culture resistant to 50 mM H2O2 was isolated on BHIS agar, and a single colony (designated IB263) was selected for further experiments.

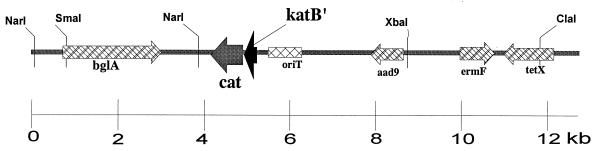

Construction of a katB::cat transcriptional fusion.

A katB::cat transcriptional fusion was constructed and integrated into the B. fragilis chromosome in order to study trans-acting regulation of the katB promoter. Briefly, a 0.8-kb blunt-ended TaqI DNA fragment containing the ribosome-binding site and coding region of the Tn9 chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) gene was ligated into the internal EcoRV and MscI sites of katB in pFD567 (28). Restriction digestion of the new construct pFD605(katB′::cat) showed that the cat gene was in the same orientation as katB. Subsequently, a 2.5-kb SmaI/NarI fragment from pFD605(katB′::cat) was cloned into the unique SmaI/NarI sites of the suicide vector pFD516 (39). Then a 3.8-kb NarI fragment from pFD620 carrying B. fragilis β-glucosidase bglA gene (Genbank accession no. AF006658) was cloned in the unique NarI site of the construct to provide a target for single-crossover-targeted insertion in the B. fragilis chromosome. The bglA gene is not essential for growth in BHIS, and there is at least one additional β-glucosidase gene in B. fragilis (31). The new construct, pFD688(katB′::cat) (Fig. 1), was mobilized from Escherichia coli DH5α by triparental mating into B. fragilis 638R and IB263, using standard filter mating protocols (36). Southern blotting hybridization analysis revealed that pFD688 was integrated into the B. fragilis bglA locus, creating strains 638R (katB+ katB′::cat) and IB263 (katB+ katB′::cat). Total RNA extraction and Northern blot analysis of katB mRNA were carried out exactly as previously described (30). The densitometry analysis of the autoradiograph was normalized to the relative intensity of total 23S and 16S rRNAs detected on the ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel.

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the suicide shuttle vector pFD688 containing the transcriptional fusion katB′::cat and the bglA locus for targeted insertion into the chromosome of B. fragilis. Construction of the strains 638R (katB+ katB′::cat) and IB263 (katB+ katB′::cat) by using pFD688 is described in Materials and Methods.

Catalase and CAT enzyme assays.

Catalase activity was measured spectrophotometrically as previously described (28). One unit of catalase is the amount of enzyme which decomposes 1 μmol of H2O2 per min at 25°C. The spectrophotometric assay for CAT was performed in crude extracts essentially as described by Brosius and Lupski (7).

Partial protein purification and PAGE.

Partial purification of oxidative stress proteins was obtained by electroelution of the bacterial crude extract on a polyacrylamide gel at 40-mA constant current, using a Prep-Cell model 491 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Melville, N.Y.). Fractions containing the proteins of interest were pooled and concentrated. Preparative and analytical nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and denaturing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-PAGE were performed as described by Laemmli (21). Following electrophoresis, proteins were detected by staining the gel with either Coomassie blue R250 or Ponceau S. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (6), using lysozyme as a standard.

N-terminal amino acid sequence and database comparison.

The proteins resolved by SDS-PAGE were blotted to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane in 10 mM CAPS (3-[cyclohexylamino-1-propanesulfonic acid])–10% methanol, pH 11.0 (23). The blotted proteins were subjected to fully automated solid-phase Edman degradation to determine the N-terminal amino acid sequence. The N-terminal sequencing was performed by D. Klapper, University North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Computer analyses of N-terminal amino acid sequences were performed with the University of Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group DNA sequence analysis software (11).

RESULTS

Isolation and characterization of a hydrogen peroxide-resistant mutant.

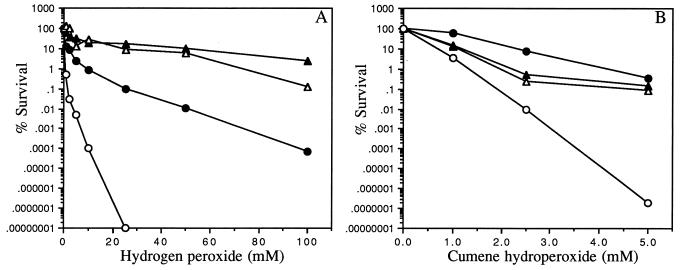

A B. fragilis hydrogen peroxide-resistant strain, IB263, was isolated following enrichment of the 638R cultures in increasing concentrations of H2O2. After several passages in BHIS in the absence of H2O2, cell viable counts were performed to determine whether resistance to H2O2 was constitutively expressed in IB263. The mutant strain IB263 was no longer killed by passage in media containing as much as 50 mM H2O2, suggesting that there was constitutive resistance to H2O2 due to a stable mutation(s) rather than a reversible and temporary physiological adaptation. This possibility was supported by the results in Fig. 2A, where it is clearly shown that IB263 was highly resistant up to 100 mM H2O2 with or without H2O2 induction. In contrast, the parent strain lost about 2 orders of magnitude in viability in the presence of 5 mM H2O2 when the peroxide response was induced, and there was essentially no protection in untreated cells.

FIG. 2.

Survival of mid-log-phase cells of B. fragilis 638R and IB263 following addition of hydrogen peroxide (A) and CHP (B) for 15 min. Data points represent B. fragilis 638R cultures pretreated (•) and not pretreated (○) with H2O2 and B. fragilis IB263 cultures pretreated (▴) and not pretreated (▵) with H2O2.

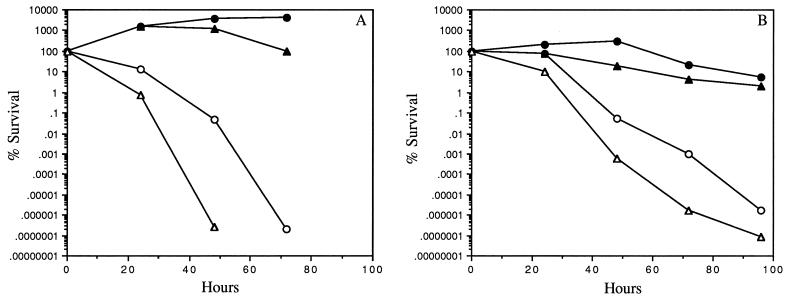

The results in Fig. 2B showed that IB263 also was constitutively resistant to the organic peroxide CHP up to 5 mM in the presence of bipyridyl. In the parent strain, resistance to higher concentrations of CHP required induction by pretreatment with H2O2. Pretreatment of the parent cultures with 50 μM CHP induced a similar response, suggesting that either hydrogen or alkyl peroxide is able to induce resistance to organic peroxide (data not shown). In contrast to the increased peroxide resistance, the mutant strain was not altered or slightly more sensitive to molecular oxygen compared to the parent strain (Fig. 3). Mid-log-phase cells of the peroxide-resistant strain exposed to oxygen for 48 h had about a 5-log decrease in the number of viable cells compared to that of the parent culture control, which took 72 h to decrease to approximately the same number of survival cells. Stationary-phase mutant cells shifted to aerobic conditions also were slightly more sensitive to oxygen than the parent, but overall stationary-phase cells were less sensitive to oxygen than log-phase cells. No apparent difference was noted for the anaerobic condition culture controls.

FIG. 3.

Survival of anaerobic B. fragilis 638R (•) and IB263 (▴) mid-log-phase (A) and stationary-phase (B) cells shifted to aerobic conditions (○ and ▵, respectively). Cultures of mid-log-phase cells (A550 = 0.3) or early-stationary-phase cells (A550 = 1.1) were divided at time zero; one half was shaken at 250 rpm in air, and the other half was maintained anaerobically. Viable cell counts were determined at the times shown.

Deregulation of catalase activity and evidence for a trans-acting regulatory mechanism.

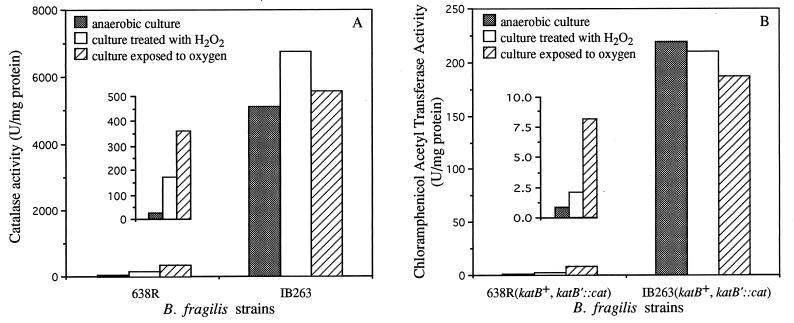

Previous work had shown that induction of catalase was essential for full protection against exogenous H2O2 (29). Thus, to investigate whether constitutive resistance to H2O2 was correlated to an increase in catalase activity, both parent and mutant strains were tested by catalase assays (Fig. 4A). Catalase activity of approximately 5,100 U/mg of protein was found in crude extracts of the mutant strain grown in chemically defined medium, indicating that it was no longer repressed under anaerobic conditions. There was a >180-fold increase over the much lower activity (27 U/mg protein) found in the anaerobic cultures of the parent strain, suggesting that the mechanism(s) that controls catalase expression in the parent strain is no longer functional in the mutant. In addition, there was no further significant induction of catalase activity when anaerobic cultures of IB263 were exposed to oxygen or treated with hydrogen peroxide (6,700 and 5,600 U/mg of protein, respectively). In contrast there was approximately a 15-fold-higher activity induced in the parent strain following exposure to the same oxidative stress conditions (170 and 360 U/mg of protein, respectively). As the catalase regulation in the parent strain occurs at the transcriptional level (30), Northern blot hybridization analysis of the mutant was carried out. The results revealed that the level of katB mRNA present in strain IB263 under anaerobic conditions was approximately 20-fold higher than in the anaerobic culture of the parent strain (Fig. 5). katB mRNA obtained from the mutant exposed to oxygen or treated with hydrogen peroxide showed a slight increase in expression which was similar to the induction seen for the parent strain (between 30- and 35-fold increase). These results strongly suggest that the high levels of catalase in the mutant strain were due to the transcriptional deregulation of katB mRNA expression.

FIG. 4.

Catalase (A) and CAT (B) activities in crude extracts of mid-log-phase cells of B. fragilis strains grown in chemically defined medium under different oxidative stress conditions. The insets show amplified scales of the B. fragilis 638R catalase and CAT activities.

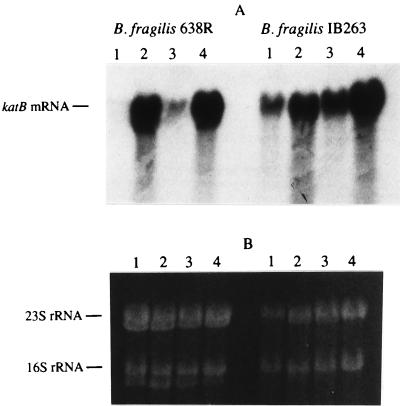

FIG. 5.

Northern hybridization analysis of mid-log-phase B. fragilis 638R and IB263 cells under different oxidative stress conditions. (A) Autoradiograph of a Northern blot probed with the katB internal fragment. (B) Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel loaded with 30 μg of total RNA in each lane. The 23S and 16S rRNAs are also indicated. Lanes: 1, anaerobic cultures; 2, cultures treated with 500 μM H2O2; 3, culture treated with 1 mM potassium ferricyanide; 4, cultures exposed to aeration for 1 h.

The regulation was further investigated by using a katB::cat transcriptional fusion integrated into the bglA locus of both the parent and the mutant strain. The CAT activities in crude extracts of mid-log-phase cells of strains 638R (katB+ katB′::cat) and IB263 (katB+ katB′::cat) are shown in Fig. 4B. There was an increase of approximately 200-fold in CAT activity in the mutant strain (219 U/mg of protein) compared to the anaerobic culture of the parent strain (0.8 U/mg of protein). No further induction by oxygen exposure and treatment with H2O2 (210 and 190 U/mg of protein, respectively) was observed in IB263; in contrast, CAT activity was induced by oxidative stress conditions in the parent strain. Comparison of data for the parent and mutant strains in Fig. 4 clearly shows that the mutant lost the wild-type regulation in both the katB+ gene and the katB′::cat fusion. These results indicate that the deregulation of catalase expression is due to a mutation in a trans-acting regulatory element rather than a cis-acting mutation in the katB regulatory region.

Identification of overexpressed proteins in IB263.

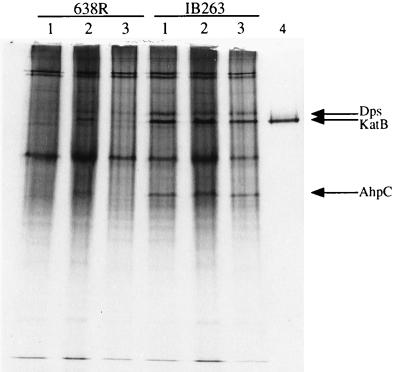

The data from the H2O2 and CHP survival studies suggested that the regulatory mutation in IB263 may affect the global oxidative stress response. Therefore, additional studies were performed to see if other oxidative stress proteins were constitutively expressed in the mutant strain. Nondenaturing PAGE of crude extracts from B. fragilis 638R and IB263 exposed to oxygen and hydrogen peroxide revealed several candidate oxidative stress proteins (Fig. 6). One overexpressed protein had an electrophoretic mobility identical to that of B. fragilis catalase KatB previously purified (28), which together with the results shown above confirms our findings showing that catalase is overexpressed in the mutant strain.

FIG. 6.

Nondenaturing PAGE (7.5 to 20% gradient polyacrylamide gel) of mid-log-phase crude extracts of B. fragilis 638R and IB263. Lanes: 1, anaerobic cultures; 2, anaerobic cultures pretreated with H2O2; 3, anaerobic cultures exposed to oxygen for 1 h; 4, approximately 2.5 μg of purified B. fragilis catalase KatB (28). Lanes 1 to 3 were loaded with approximately 50 μg of total protein; the gel was stained with Coomassie blue. Arrows show the major protein bands that are overexpressed in the mutant strain.

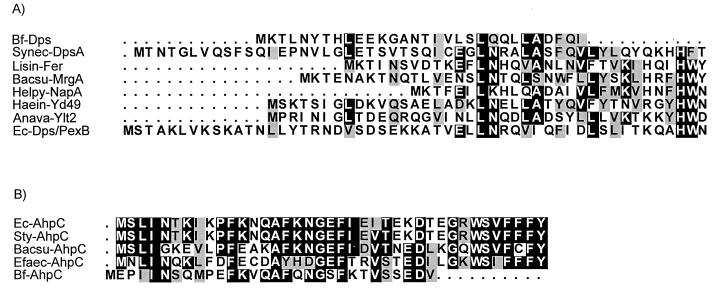

Two of the overexpressed proteins were characterized further following partial purification using preparative nondenaturing PAGE and SDS-PAGE. One protein had a single-subunit molecular weight of approximately 18,000 as determined by SDS-PAGE; the protein was electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and the N-terminal amino acid sequence was determined. Alignment of the first 30 amino acid residues of the N terminus with amino acid sequences available from the GenBank database showed similarity to the Dps protein family of DNA-binding proteins (Fig. 7A). Comparison of the B. fragilis Dps-like protein to members of the Dps group of proteins revealed 27% identity (38% similarity) to E. coli Dps/PexB protein, 21% identity (38% similarity) to an Haemophilus influenzae Dps homologue, 30% identity (33% similarity) to Synechococcus strain PCC7942 nutrient stress-induced DNA-binding hemoprotein (DpsA), 23% identity (37% similarity) to an Anabaena variabilis low-temperature-induced protein, 25% identity (35% similarity) to Helicobacter pylori neutrophil-activating protein A (NapA; bacterioferritin), 20% identity (30% similarity) to B. subtilis MrgA, and 23% identity (30% similarity) to Listeria innocua nonheme iron-binding ferritin.

FIG. 7.

(A) Alignment of the N-terminal amino acid sequence of a B. fragilis Dps homologue (Bf-Dps) with those of Synechococcus strain PCC7942 (Synec-DpsA) (26), nonheme iron-binding ferritin of L. innocua (Lisin-Fer) (5), B. subtilis MrgA (Bacsu-MrgA) (8), H. pylori NapA (Helpy-NapA) (13), H. influenzae (Haein-YD49; GenBank accession no. P45173), A. variabilis low-temperature-induced protein (Anava-YLT2; GenBank accession no. P29712), and E. coli Dps/PexB (Ec-Dps/PexB) (1). (B) Alignment of the N-terminal amino acid sequence of a B. fragilis AhpC homologue (Bf-AhpC) with those of E. coli AhpC (Ec-AhpC; GenBank accession no. D90701), S. typhimurium AhpC (Sty-AhpC; GenBank accession no. P19479), B. subtilis AhpC (Bacsu-AhpC) (17), and E. faecalis AhpC (Efaec-AhpC; GenBank accession no. AF016233). Consensus of at least 50% identical amino acid residues is denoted by black boxes; conserved amino acid substitutions are depicted by grey boxes.

Another constitutively expressed protein that was characterized had a single subunit with a molecular weight of approximately 22,000 (data not shown). Alignment of the first 30 N-terminal amino acids revealed strong homology to bacterial alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C (AhpC) and to the thiol-specific antioxidant family of antioxidant proteins from prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Alignment of B. fragilis AhpC with other bacterial alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C is shown in Fig. 7B. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of B. fragilis AhpC revealed 39% identity (46% similarity) to E. coli AhpC, 43% identity (46% similarity) to S. typhimurium AhpC, 34% identity (41% similarity) to B. subtilis AhpC, and 35% identity (52% similarity) to Enterococcus faecalis AhpC.

DISCUSSION

When mid-log-phase cells of B. fragilis are shifted from anaerobic to aerobic conditions, they are no longer able to maintain cell division but cell viability remains high even after oxygen exposure for up to 3 days. We are interested in understanding the physiological adaptations that occur during this period of reversible growth arrest under aerobic conditions. The initial studies suggested that the ROS-scavenging enzymes superoxide dismutase and catalase were important for aerotolerance in B. fragilis (24). More recently, Rocha et al. (29) have shown that response to oxidative stress in B. fragilis induces the synthesis of at least 28 proteins in the presence of oxygen or hydrogen peroxide. This finding is very interesting since this obligate anaerobe is not able to shift to an aerobic metabolism and maintain growth under aerobic conditions but does respond with the synthesis of a protective mechanism against the toxic effects of ROS. In this study, we describe the isolation and partial characterization of a B. fragilis H2O2- and organic peroxide-resistant mutant and identification of constitutively expressed proteins that may be potentially involved in protection against ROS in anaerobic bacteria.

The resistance to high levels of H2O2 in mutant strain IB263 was correlated with constitutive catalase activity, and the important role that KatB plays in protection against an exogenous source of H2O2 is consistent with this observation (29). In addition, evidence showing that B. fragilis produces homologues of AhpC and Dps, which are known to be involved in resistance to peroxides and oxidative DNA damage, was presented (1, 22, 41). Taken together, the constitutive resistance to hydrogen peroxide and organic peroxide and the overexpression of KatB, AhpC, and Dps in IB263 suggest that these activities are linked to a peroxide resistance response and may be under a common transcriptional regulator. Strong support for this idea was provided by the promoter fusion experiments. The findings in Fig. 4B clearly showed that the wild-type katB promoter was deregulated in IB263 but regulated normally in the parent, which suggests that a trans-acting regulatory mechanism controlling the peroxide response exists in B. fragilis. However, at this point it is not possible to rule out the formal possibility that the deregulation of KatB, AhpC, and Dps resulted from multiple mutations induced by the H2O2 enrichment technique. This matter will be clarified in further studies on complementation or isolation of the mutation.

The peroxide response in facultative and aerobic bacteria has been extensively studied and found to be complex and tightly regulated. In E. coli and S. typhimurium, the H2O2 redox sensor and transcriptional activator OxyR induces in mid-log-phase cells the synthesis of nine proteins, including KatG, AhpCF, GorA, and Dps (2, 9). A constitutive OxyR mutant confers overexpression of these proteins and resistance to hydrogen peroxide (9). More recently, Zheng et al. (47) have shown that two OxyR conserved cysteine residues specifically sense peroxides, forming disulfide bonds leading to intramolecular conformational changes and activation of OxyR. In B. subtilis, a hydrogen peroxide-resistant mutant overexpresses KatA, AhpC, and MrgA (a metalloregulated Dps homologue), possibly due to a mutation in a transcriptional repressor (17) that may contain a redox-active metal ion cofactor (8). Thus, there are a variety of mechanisms able to sense oxidative stress in cells, and it will be of interest to determine the mode of control in anaerobic organisms.

Dps protein has been found in several aerobic organisms (1, 5, 8, 13, 26, 46), and one of its major functions is to protect DNA against oxidative damage (22). However, Dps may participate in gene regulation in stationary-phase and in peroxide-consuming reactions located at the chromosome (1, 26). Dps protein is related to the ferritin/bacterioferritin family of iron storage proteins, suggesting the possibility of divergence from a common ancestor (5, 26). Moreover, both AhpC and Dps in S. typhimurium (15, 43) and AhpC in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (12) were induced during interactions with macrophages, suggesting that these oxidative stress proteins may participate in survival to the macrophage oxidative burst killing mechanisms. These findings raise several questions as to how anaerobic bacteria have acquired genes involved in detoxification and protection against toxic ROS since they are adapted to live in the absence of molecular oxygen.

Despite the high resistance to hydrogen peroxide in B. fragilis IB263 under anaerobic conditions, there is no corresponding increase in resistance to oxygen exposure. In contrast, it seems that the mutant strain was slightly more sensitive to oxygen than the parent strain. Although the peroxide response may be effective in scavenging and detoxifying peroxides formed during oxygen exposure, it is not clear whether this deregulated peroxide response would eventually affect other protective mechanisms, such as a superoxide response, that might be involved in controlling aerotolerance in this strain. On the other hand, it is possible that other secondary mutations affecting the sensitivity to oxygen are present in IB263. However, evidence supporting the possibility that oxygen toxicity is somehow different from the toxicity exerted by the H2O2 is available from previous studies showing that the effect of H2O2 on the degradation and repair of DNA differs from the effect of oxygen in irradiated B. fragilis cells (34, 37). B. fragilis Bf-2 was more sensitive to DNA-damaging agents such as far-UV radiation, N-methyl-N′-nitrosoguanidine, ethyl methanesulfonate, acriflavine, and mitomycin C in the presence of oxygen than when treated with H2O2. Aerotolerance and resistance to ROS in anaerobic bacteria may be part of a more complex mechanism which still remains to be elucidated. In this regard, we have identified several classes of genes that are differentially induced by various oxidative stresses (unpublished), and this investigation will be the focus of a future report.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grant 9513-ARG-0038 from the North Carolina Biotechnology Center and PHS grant AI-28884.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almirón M, Link A J, Furlong D, Kolter R. A novel DNA-binding protein with regulatory and protective roles in starved Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2646–2654. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altuvia S, Almirón M, Huisman G, Kolter R, Storz G. The dps promoter is activated by OxyR during growth and by IHF and ςS in stationary phase. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:265–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antelmann H, Engelmann S, Schmid R, Sorokin A, Lapidus A, Hecker M. Expression of a stress- and starvation-induced dps/pexB-homologous gene is controlled by the alternative sigma factor ςB in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7251–7256. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7251-7256.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bol D K, Yasbin R E. Characterization of an inducible oxidative stress system in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3503–3506. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3503-3506.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bozzi M, Mignogna G, Stefanini S, Barra D, Longhi C, Valenti P, Chiancone E. A novel non-heme iron-binding ferritin related to the DNA-binding proteins of the Dps family in Listeria innocua. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3259–3265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brosius J, Lupski J R. Plasmids for the selection and analysis of procaryotic promoters. Methods Enzymol. 1987;153:54–68. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)53047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen L, Helmann J D. Bacillus subtilis MrgA is a Dps(PexB) homologue: evidence for metalloregulation of an oxidative-stress gene. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:295–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18020295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christman M F, Morgan R W, Jacobson F S, Ames B N. Positive control of a regulon for defenses against oxidative stress and some heat-shock proteins in Salmonella typhimurium. Cell. 1985;41:753–762. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demple B, Halbrook J. Inducible repair of oxidative DNA damage in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1983;304:466–468. doi: 10.1038/304466a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhandayuthapani S, Via L E, Thomas C A, Horowitz P M, Deretic D, Deretic V. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene-expression and cell biology of mycobacterial interactions with macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1994;17:901–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17050901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans D J, Evans D G, Lampert H C, Nakano H. Identification of four new prokaryotic bacterioferritins, from Helicobacter pylori, Anabaena variabilis, Bacillus subtilis and Treponema pallidum, by analysis of gene sequences. Gene. 1995;153:123–127. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00774-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farr S B, Kogoma T. Oxidative stress responses in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:561–585. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.4.561-585.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francis K P, Taylor P D, Inchley C J, Gallagher M P. Identification of the ahp operon of Salmonella typhimurium as a macrophage-induced locus. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4046–4048. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.4046-4048.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregory E M. Characterization of the O2-induced manganese-containing superoxide dismutase from Bacteroides fragilis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;238:83–89. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartford O M, Dowds B C. Isolation and characterization of a hydrogen peroxide resistant mutant of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 1994;140:297–304. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-2-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imlay J A, Chin S M, Linn S. Toxic DNA damage by hydrogen peroxide through the Fenton reaction in vivo and in vitro. Science. 1988;240:640–642. doi: 10.1126/science.2834821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imlay J A, Linn S. DNA damage and oxygen radical toxicity. Science. 1988;240:1302–1309. doi: 10.1126/science.3287616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jamieson D J, Storz G. Transcriptional regulators of oxidative stress responses. In: Scandalios J, editor. Oxidative stress and the molecular biology of antioxidant defenses. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 91–115. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez A, Kolter R. Protection of DNA during oxidative stress by the nonspecific DNA-binding protein Dps. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5188–5194. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.16.5188-5194.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsudara P. A practical guide to protein and peptide purification for microsequencing. 2nd ed. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris J G. Oxygen tolerance/intolerance of anaerobic bacteria. In: Gottschalk G, Penning N, Werner H, editors. Anaerobes and anaerobic infections. Stuttgart, Germany: Gustav Fisher Verlag; 1980. pp. 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy P, Dowds B C A, McConnell D J, Devine K M. Oxidative stress and growth temperature in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5766–5770. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5766-5770.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peña M M O, Bullerjahn G S. The DpsA protein of Synechococcus sp. strain PCC7942 is a DNA-binding hemoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22478–22482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Privitera G, Dublanchet A, Sebald M. Transfer of multiple antibiotic resistance between subspecies of Bacteroides fragilis. J Infect Dis. 1979;139:97–101. doi: 10.1093/infdis/139.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rocha E R, Smith C J. Biochemical and genetic analyses of a catalase from the anaerobic bacterium Bacteroides fragilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3111–3119. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3111-3119.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocha E R, Selby T, Coleman J P, Smith C J. The oxidative stress response in an anaerobe, Bacteroides fragilis: a role for catalase in protection against hydrogen peroxide. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6895–6903. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6895-6903.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rocha E R, Smith C J. Regulation of Bacteroides fragilis katB mRNA expression by oxidative stress and carbon limitation. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7033–7039. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7033-7039.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rocha, E. R., and C. J. Smith. Unpublished data.

- 32.Rolfe R D, Hentges D J, Barrett J T, Campbell B J. Oxygen tolerance of human intestinal anaerobes. Am J Clin Nutr. 1977;30:1762–1769. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/30.11.1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roszak D B, Colwell R R. Survival strategies of bacteria in the natural environment. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:365–379. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.3.365-379.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schumann J P, Jones D T, Woods D R. UV light induction of proteins in Bacteroides fragilis under anaerobic conditions. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:44–47. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.1.44-47.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schumann J P, Jones D T, Woods D R. Induction of proteins during phage reactivation induced by UV irradiation, oxygen and peroxide in Bacteroides fragilis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1984;23:131–135. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shoemaker N B, Getty C, Gardner J F, Salyers A A. Tn4351 in Bacteroides spp. and mediates the integration of plasmid R751 into the Bacteroides chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:929–936. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.3.929-936.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slade H J K, Jones D T, Woods D R. Effect of oxygen and peroxide on Bacteroides fragilis cell and phage survival after treatment with DNA damaging agents. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1984;24:159–163. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith C J. Characterization of Bacteroides ovatus plasmid pBI136 and structure of its clindamycin resistance region. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:1069–1073. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.3.1069-1073.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith C J, Rollins L A, Parker A C. Nucleotide sequence determination and genetic analysis of the Bacteroides plasmid, pBI143. Plasmid. 1995;34:211–222. doi: 10.1006/plas.1995.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Storz G, Tartaglia L A, Farr S B, Ames B N. Bacterial defenses against oxidative stress. Trends Genet. 1990;6:363–368. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(90)90278-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Storz G, Jacobson F S, Tartaglia L A, Morgan R W, Silveira L A, Ames B N. An alkyl hydroperoxide reductase induced by oxidative stress in Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli: genetic characterization and cloning of ahp. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2049–2055. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.4.2049-2055.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tally F P, Stewart P R, Sutter V L, Rosenblatt J E. Oxygen tolerance of fresh clinical anaerobic bacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1975;1:161–164. doi: 10.1128/jcm.1.2.161-164.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valvidia R H, Falkow S. Bacterial genetics by flow cytometry: rapid isolation of Salmonella typhimurium acid-inducible promoters by differential fluorescence induction. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:367–378. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Varel V H, Bryant M P. Nutritional features of Bacteroides fragilis subsp. fragilis. Appl Microbiol. 1974;18:251–257. doi: 10.1128/am.28.2.251-257.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Unden G, Becker S, Bongaerts J, Schirawski J, Six S. Oxygen regulated gene expression in facultative bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1994;66:3–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00871629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walfield A M, Roche E S, Zounes M C, Kirkpatrick H, Wild M A, Textor G, Tsai P K, Richardson C. Primary structure of an oligomeric antigen of Treponema pallidum. Infect Immun. 1989;57:633–635. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.2.633-635.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng M, Aslund F, Storz G. Activation of the OxyR transcription factor by reversible disulfide bond formation. Science. 1998;279:1718–1721. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5357.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]