Abstract

The small DNA binding protein Fis is involved in several different biological processes in Escherichia coli. It has been shown to stimulate DNA inversion reactions mediated by the Hin family of recombinases, stimulate integration and excision of phage λ genome, regulate the transcription of several different genes including those of stable RNA operons, and regulate the initiation of DNA replication at oriC. fis has also been isolated from Salmonella typhimurium, and the genomic sequence of Haemophilus influenzae reveals its presence in this bacteria. This work extends the characterization of fis to other organisms. Very similar fis operon structures were identified in the enteric bacteria Klebsiella pneumoniae, Serratia marcescens, Erwinia carotovora, and Proteus vulgaris but not in several nonenteric bacteria. We found that the deduced amino acid sequences for Fis are 100% identical in K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. coli, and S. typhimurium and 96 to 98% identical when E. carotovora and P. vulgaris Fis are considered. The deduced amino acid sequence for H. influenzae Fis is about 80% identical and 90% similar to Fis in enteric bacteria. However, in spite of these similarities, the E. carotovora, P. vulgaris, and H. influenzae Fis proteins are not functionally identical. An open reading frame (ORF1) preceding fis in E. coli is also found in all these bacteria, and their deduced amino acid sequences are also very similar. The sequence preceding ORF1 in the enteric bacteria showed a very strong similarity to the E. coli fis P region from −53 to +27 and the region around −116 containing an ihf binding site. Both β-galactosidase assays and primer extension assays showed that these regions function as promoters in vivo and are subject to growth phase-dependent regulation. However, their promoter strengths vary, as do their responses to Fis autoregulation and integration host factor stimulation.

Escherichia coli harbors several abundant small DNA binding proteins collectively referred to as nucleoid-associated proteins (NAPs) because of their potential to bind large quantities of DNA and contribute to the structure of the bacterial nucleoid (12, 49, 50). These include HU, H-NS, integration host factor (IHF), and factor for inversion stimulation (Fis). In addition, these proteins can affect various biological processes involved in site-specific DNA recombination, DNA replication, or transcription (12, 16, 49). In some cases, two or more of these proteins may cooperate in the same process. For example, Fis and HU participate in Hin-mediated DNA recombination (26) and Fis and IHF aid in promoting site-specific recombination of λ DNA (3, 4, 16, 54). In other cases, these proteins can play opposing roles, as with Fis and H-NS on transcription of hns (13) or IHF and Fis on transcription of fis (45).

The abundance of NAPs may vary depending on the growth phase. For instance, Fis mRNA and protein levels are extremely low during stationary phase but rapidly increase over 500-fold during early logarithmic growth phase (5, 37, 38, 54). IHF levels are 5- to 10-fold higher in the stationary growth phase than in the logarithmic growth phase (11). Both the homodimeric α and heterodimeric αβ HU are detected during exponential growth, while the heterodimeric form of HU predominates during stationary phase (9). H-NS protein levels, on the other hand, remain relatively constant throughout the different growth phases (18). The relative abundance of these proteins can potentially affect the nucleoid structure and the specific processes they mediate.

Fis is a basic homodimer, with each subunit consisting of 98 amino acids. Its crystal structure shows that each subunit contains a β-hairpin (residues 11 to 26) followed by four α-helices (A, B, C, and D) separated by short turns (30, 31, 47, 57). Residues within the β-hairpin, in particular Val16, Asp20, and Val22, are required for stimulation of Hin-mediated DNA inversion and presumably participate in transient interactions between Fis and the Hin recombinase (29, 41, 47). Residues within helix A and the loop between helices C and D are required for stimulation of transcription of rrnB P1 (23). Presumably, residues in this loop region interact with RNA polymerase at this promoter to stimulate transcription (22). Finally, residues comprising the carboxy-terminal helices C and D form a helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif required for DNA binding and bending (29, 31, 41, 57).

An open reading frame (ORF1) of unknown function, consisting of 321 codons, precedes fis in both E. coli and Salmonella typhimurium (5, 38, 42). A single promoter preceding ORF1 transcribes both ORF1 and fis as an approximately 1,400-base mRNA (5, 38). When cells in stationary phase are batch cultured in a nutritionally rich medium, fis mRNA levels increase more than 1,000-fold within the time required to initiate logarithmic cell division. Thereafter, fis mRNA levels decline, reaching less than 1% of their peak values as the cells enter stationary phase. A similar expression pattern is observed at the Fis protein level (5, 37, 54). Since the fis mRNA half-lives remain close to 2 min throughout this period of fis expression, growth phase-dependent expression is not significantly influenced by mRNA decay (45). Hence, the fis expression pattern is controlled primarily at the level of transcription.

Transcription from the fis promoter (fis P) is negatively regulated by Fis. Although six Fis binding sites have been identified in this promoter region (5), Fis site II (overlapping the −35 region) plays a predominant role in this function, whereas Fis site I (extending from +11 to +37) plays a secondary role (38, 45). Recently, we showed that transcription from fis P was stimulated 3.8-fold by IHF, an effect that requires IHF binding to a site centered close to −116 relative to fis P (45).

Little is known about the existence, function, or regulation of fis in organisms other than E. coli and S. typhimurium (5, 16, 38, 42, 45). A homology search revealed that the Haemophilus influenzae genome contains a good match to fis, but its product has not been previously examined. In this work, we extend the characterization of the fis operon to several other bacteria. We identify, clone, and sequence the fis operons from Klebsiella pneumoniae, Serratia marcescens, Erwinia carotovora, and Proteus vulgaris and compare them to those of E. coli, S. typhimurium, and H. influenzae. In addition, several aspects of the function and regulation of fis from these bacteria are examined. We found that the fis operon is highly conserved among enteric bacteria. Although Fis is strikingly similar among enteric bacteria, certain amino acid differences affect its ability to participate in some processes characterized in E. coli and S. typhimurium. For all enteric fis promoters studied here, expression in E. coli is growth phase dependent, but promoter strengths and regulatory responses to IHF and Fis vary.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals, enzymes, and growth media.

All chemicals were from Sigma Chemical Co., Fisher Scientific Co., VWR Scientific, or Life Technologies Inc. (Gibco BRL). Avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase was from Promega Corp., and all other enzymes were from New England Biolabs Inc. or Promega Corp., unless otherwise indicated. Bacterial culture media were from Difco Laboratories. The radioisotopes [γ-32P]ATP and [α-32P]dATP were from Amersham Life Science Inc. Oligonucleotides were synthesized in a Perkin-Elmer automatic DNA synthesizer in the Department of Biological Sciences, University at Albany, Albany, N.Y. Chromosomal DNA samples from K. pneumoniae, Shigella flexneri, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, P. vulgaris, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Micrococcus luteus, Vibrio cholerae, Bacillus subtilis, Caulobacter crescentus, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae were a generous gift from Kevin McEntee (University of California, Los Angeles, Calif.). A DNA clone (GHIDO76) containing fis from H. influenzae was obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR).

Bacterial cultures were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or on MacConkey agar medium supplemented with 1% lactose (35). To select for appropriate drug resistance, 100 μg of ampicillin per ml, 50 μg of kanamycin per ml, 75 μg of spectinomycin per ml, 50 μg of streptomycin per ml, or 12 μg of tetracycline per ml were added to the growth media.

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

E. coli RZ211 [F− Δ(lac-pro) thi ara str recA56 strL] (28) and RJ1561 (RZ211 fis::767) (25) were used to monitor fis promoter activity in β-galactosidase or primer extension assays. MC4100 [F− λ− araD139 Δ(argF-lac) U169 rpsL1 relA1 deoC1 ptsF25 rboR flb5301] and HP4110 (MC4100 ihfA::Tn10) were obtained from Prassanta Datta (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.) and were also used for β-galactosidase assays. RJ2539 (CSH26 fis::767 recA56 srl str λfla406 ‘OFF’/pKH66/F′ proAB lacIsqZU118Y+) was used to examine the ability of fis to stimulate Hin-mediated DNA inversion (41). The λ lysogen RJ1765 [fis::767 Δ(lac-pro) ara rpsL λcI857 Sam7 F′ proAB lacIsqZU118] was used in λ excision assays (3). The λ lysogen RO796 [fis::767 Δ(lac-pro) ara str λRJ1083 F′ proAB lacIq/pMS421] was used to assay repression of the fis promoter by different Fis proteins in β-galactosidase assays (5). λRJ1083 carries a lacZ fusion to the fis promoter region from −375 to +78 within λRS45 (52). λfla406 ‘OFF’ (7) contains the S. typhimurium invertible DNA region (including hixL, hixR, and the recombinational enhancer) inserted upstream of lacZ such that a promoter within the invertible DNA region transcribes away from lacZ (‘OFF’ orientation).

Plasmid pKH66 carries the S. typhimurium hin under tac promoter control. Other plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. Plasmid GHIDO76, carrying H. influenzae fis, was obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR). The fis-, ORF1-, and fis P-containing DNA fragments from K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, P. vulgaris, and H. influenzae that were cloned into pUC18 or pRJ807 were synthesized by PCR. Plasmid pRJ807 is a pKK223-3-based expression vector carrying E. coli fis (41).

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this work

| Plasmid | Description | Source or referenceb |

|---|---|---|

| GHIDO76 | H. influenzae fis cloned into SmaI of pUC18 | TIGR |

| pCK186 | K. pneumoniae fis P region (−1193 to +78) cloned into XbaI of pRJ800 | |

| pMB178 | K. pneumoniae fis cloned into BamHI of pUC18 | |

| pMB180 | P. vulgaris fis cloned into BamHI of pUC18 | |

| pMB182 | E. carotovora fis cloned into BamHI of pUC18 | |

| pMB183 | S. marcescens fis cloned into BamHI of pUC18 | |

| pMB193 | P. vulgaris fis P region (−306 to +78) cloned into XbaI of pRJ800 | |

| pMB194 | S. marcescens fis P region (−377 to +78) cloned into XbaI of pRJ800 | |

| pMB195 | K. pneumoniae ORF1 cloned into PstI of pACYC177 | |

| pMB196 | S. marcescens ORF1 cloned into PstI of pACYC177 | |

| pMB231 | P. vulgaris ORF1 cloned into PstI of pACYC177 | |

| pMB237 | E. carotovora ORF1 cloned into HincII and PstI of pACYC177 | |

| pMB238 | S. marcescens 3′ end of fis cloned into XbaI and SmaI of pUC18 | |

| pMB239 | E. carotovora 3′ end of fis cloned into XbaI and SmaI of pUC18 | |

| pMB258 | E. carotovora fis P region (−1270 and +78) cloned into XbaI of pRJ800 | |

| pMB260 | E. carotovora fis P region (−168 to +78) cloned within EcoRI and XbaI of pRJ800 | |

| pMB261 | K. pneumoniae fis P region (−168 to +78) cloned within EcoRI and XbaI of pRJ800 | |

| pMB262 | P. vulgaris fis P region (−172 to +78) cloned within EcoRI and XbaI of pRJ800 | |

| pMB263 | S. marcescens fis P region (−172 to +78) cloned within EcoRI and XbaI of pRJ800 | |

| pMB283 | H. influenzae fis cloned into EcoRI and XmnI of pRJ807 | |

| pMB284 | E. carotovora fis cloned into EcoRI and XmnI of pRJ807 | |

| pMB285 | P. vulgaris fis cloned into EcoRI and XmnI of pRJ807 | |

| pMB314 | E. coli fis mutated to encode P. vulgaris Fis within pRJ807 | |

| pMB315 | E. coli fis mutated to encode E. carotovora Fis within pRJ807 | |

| pMS421 | pSC101 (lacIq Strr Spcr) | M. Susskind |

| pMS621 | pKK223-3 (Ampr Kanr) expression vector | 27 |

| pRJ800 | pBR322-based plasmid carrying the (trp-lac)W200 fusion preceded by the pUC18 polylinker region (Ampr) | 5 |

| pRJ807 | E. coli fis cloned into EcoRI and HindIII in pMS621 | 41 |

| pRJ1028 | E. coli fis P region (−375 to +78) cloned within HincII of pRJ800 | 45 |

| pRJ1070a | E. coli fis P region (−315 to +78) cloned within HincII and KpnI of pRJ800 | |

| pRJ1071 | E. coli fis P region (−168 to +78) cloned within HincII and KpnI of pRJ800 | 45 |

| pRJ1122 | pRJ807Δfis | 42 |

Made from pRJ1028 by R. Osuna and R. C. Johnson by a described exonuclease III digestion procedure (45).

Unless otherwise indicated, all plasmids were constructed during the course of this work.

Southern blot hybridization.

Southern blot hybridizations were performed at 42°C with a 50% formamide solution as described previously (48). The EcoRI-HindIII DNA fragment from pRJ807 (41), which contained fis, was labeled with 32P by the random-priming method (48) and used as a probe.

PCR.

PCRs were performed with Taq polymerase from Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals as described by the manufacturer. To verify the sequence data presented here, clones from two independent PCRs were sequenced or an independent PCR product was sequenced directly. To synthesize fis from several bacterial chromosomal DNAs, two degenerate oligonucleotides (oRO145 and oRO146), designed to anneal with the first and last six codons of E. coli fis, respectively, without altering the amino acid specification of codons, were used. The PCR products were cleaved with BglII and cloned into the BamHI site of pUC18 to make pMB178, pMB180, pMB182, and pMB183 (Table 1). The S. flexneri fis obtained in this fashion contained a DNA sequence identical to that in E. coli and was thus not analyzed further.

To verify the DNA sequences of the first six codons of fis, PCR products were obtained from chromosomal DNA by using an oligonucleotide that annealed to the various fis sequences with an oligonucleotide that annealed to the beginning of ORF1 or sequences with upstream of ORF1. The products, containing NsiI sites at their ends, were cleaved with NsiI and cloned into the PstI site of pACYC177 to yield pMB195, pMB196, and pMB231. The PCR product carrying the E. carotovora ORF1 contained an NsiI site at its downstream end only. After cleavage with NsiI, this DNA fragment was cloned into the HincII and PstI sites of pACYC177 to yield pMB237 (Table 1). These plasmids were used to obtain DNA sequence from the upstream fis region and the various ORF1s from different bacteria. To verify the sequences of the last six codons of S. marcescens and E. carotovora fis, we used a primer that annealed to the antisense strands of the fis genes and a second random primer that we hoped would anneal to sequences downstream of fis, allowing polymerization toward fis. Such PCR products were cleaved with XbaI at one end and cloned into the XbaI and SmaI sites of pUC18 to yield pMB238 and pMB239, and their sequences were obtained. Attempts to similarly verify the sequence comprising the final six codons in K. pneumoniae and P. vulgaris were unsuccessful.

The fis genes of E. carotovora and P. vulgaris were subcloned into the EcoRI and XmnI sites of pRJ807 to make pMB284 and pMB285, respectively. DNA fragments carrying these two genes were synthesized by PCR with pMB180 and pMB182 as DNA templates and oligonucleotides that annealed to the 5′ and 3′ ends of these fis sequences while generating XbaI and PvuII restriction sites. After cleavage with XbaI and PvuII, the XbaI ends were filled in with Klenow enzyme and all four deoxynucleoside triphosphates as described previously (48) and the fragments were cloned into the EcoRI (filled in) and XmnI sites in pRJ807, such that the E. coli fis was replaced by that of E. carotovora or P. vulgaris. A similar procedure was used to clone the H. influenzae fis from plasmid GHIDO76 into pRJ807 to make pMB283.

To facilitate the expression of E. carotovora and P. vulgaris fis in E. coli strains, site-directed mutations were performed on E. coli fis to match the codon specificities of E. carotovora and P. vulgaris while preserving the E. coli codon bias. Only the minimal mutations necessary to change the appropriate amino acids were made in each case. Two oligonucleotides that annealed to E. coli fis in pRJ807 while introducing the two changes in codon specificity were used, and PCR was performed. The PCR products were then used as a megaprimer in a second PCR together with another primer that annealed to the upstream region of fis and created an EcoRI site. This PCR product was used as a megaprimer for yet a third PCR with an additional primer that annealed to sequences about 386 bp downstream of fis and created a HindIII site. The final product was cleaved with EcoRI and HindIII and cloned into these sites in pRJ807. Plasmid pMB315 contains coding sequences for E. carotovora Fis, and pMB314 contains coding sequences for P. vulgaris Fis (Table 1). The following specific changes were made (nucleotide numbering as in Fig. 1): 59A→C and 143A→G for pMB315, and 40T→G, 42T→C, 236T→A, and 237G→A for pMB314. All clones made with PCR products were analyzed by DNA sequencing.

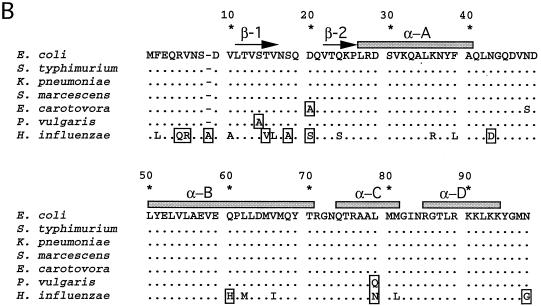

FIG. 1.

fis DNA and deduced amino acid sequences from several bacteria. (A) fis nucleotide sequences from several bacteria are aligned with that of E. coli for comparison. Identical nucleotides are indicated by dots, and nucleotide changes are indicated by the appropriate letters. Dashes denote gaps used to facilitate alignment with H. influenzae fis. The termination (Stop) codon is underlined and labeled above the sequence. Nucleotide positions are given according to their positions in fis from enteric bacteria. The sequences comprising the last six codons in K. pneumoniae and P. vulgaris have not been independently confirmed. (B) Deduced Fis amino acid sequences. Sequence alignment is formatted as in panel A. Amino acid changes from the E. coli sequence are shown by the appropriate letters. Nonconservative changes are boxed, while strictly conservative changes are not. Residues are numbered according to their positions in Fis from E. coli. Arrows above the sequence represent residues in the E. coli Fis crystal structure known to form two β-strands (47); shaded rectangles represent residues forming four α-helices (30, 57).

To synthesize DNA fragments carrying the fis promoter regions from various bacterial DNA, we performed PCR with a degenerate oligonucleotide that annealed to the various ORF1 sequences and a second degenerate oligonucleotide that hybridized to a region of the upstream E. coli gene prmA (55). The fis promoter sequences downstream of nucleotide −170 were verified in each case by sequencing two independent PCR clones. The products were cleaved with XbaI and cloned within this site in pRJ800 such that a promoter transcribing ORF1 could drive expression of the (trp-lac)W200 fusion. This procedure was used to construct plasmids pCK186, pMB193, pMB194, and pMB258 (Table 1). These clones were transformed into RJ1561 and screened by monitoring the appearance of red colonies on MacConkey-lactose agar medium. Correct orientation of these clones were verified by DNA sequencing. The insert sizes were subsequently reduced to approximately similar lengths to include the fis promoter regions from −172 or −168 to +78 relative to the predominant transcription start site. This was done by PCR with plasmids pCK186, pMB193, pMB194, and pMB258 as templates, an oligonucleotide that annealed to the respective upstream fis P regions and generated EcoRI sites, and the same oligonucleotides used above that annealed to ORF1 sequences and generated XbaI sites. The products were cleaved with EcoRI and XbaI and cloned into these sites in pRJ800 such that the fis promoter transcribed the trp-lac fusion to make pMB260, pMB261, pMB262, and pMB263 (Table 1).

DNA sequencing.

DNA sequencing was performed on alkali-denatured double-stranded plasmid DNA with Sequenase version 2.0 (U.S. Biochemicals) as specified by the supplier. The fis operon DNA sequences from S. marcescens, P. vulgaris, K. pneumoniae, and E. carotovora have been deposited with GenBank (see below).

β-Galactosidase assays.

β-Galactosidase assays were performed as described previously (35). Saturated bacterial cultures were diluted 50-fold in LB medium and grown at 37°C for 75 min with constant shaking. When testing for IHF stimulation of the various fis P regions, saturated cultures of MC4100 and HP4110 carrying fis P regions within pRJ800 were diluted 75-fold in LB medium containing ampicillin and grown at 37°C with shaking. β-Galactosidase assays were performed at various times after subculturing, and the maximum levels in the two strains were compared. All values represent an average of at least three independent assays.

Primer extensions.

Total RNA preparations and primer extension reactions were as described previously (8, 24, 45). Primers were used that hybridized to the E. coli, K. pneumoniae, or P. vulgaris fis promoter regions from +36 to +52 or to the S. marcescens or E. carotovora fis promoter regions from +35 to +51.

DNase I footprints.

Analyses of DNase I protection by Fis were performed essentially as described previously (6). The EcoRI-BamHI DNA fragments from pMB193 and pCK186 were labeled with [α-32P]dATP at their downstream BamHI sites, using Klenow enzyme, and were gel purified by the crush-and-soak method as described previously (48). The binding reactions were performed with 0, 5, 10, or 20 ng of purified E. coli Fis with 40,000 cpm of labeled DNA fragment in 45 μl of buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 80 mM NaCl), and the mixtures were incubated for 20 min at room temperature. Chemical cleavage reactions specific for G and A (34) were also performed with the same DNA fragments and used as sequence references.

Database searches.

Database searches were performed with the BLAST server (1) from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (found at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST and http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/unfinishedgenome.html). Parameters were as follows: tblastn program, default filter, expect threshold of 10, and nr database. Codon usage data were obtained from CUTG (Codon Usage Tabulated from GenBank) at http://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/∼nakamura/CUTG.html.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The fis operon DNA sequences from S. marcescens, P. vulgaris, K. pneumoniae, and E. carotovora have been given GenBank accession no. AF040378, AF040379, AF040380, and AF040381, respectively.

RESULTS

Identification of fis in other bacteria.

Southern blot analysis with E. coli fis as a 32P-labeled probe allowed the detection of fis in DNA from the enteric bacteria K. pneumoniae, S. flexneri, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris (results not shown). On the other hand, chromosomal DNA from the gram-negative V. cholerae, P. aeruginosa, and C. crescentus, the gram-positive M. luteus and B. subtilis, or the eukaryotic S. cerevisiae gave no detectable hybridization signals, suggesting either that fis sequences are not present in these organisms or that they are too divergent from that of E. coli to be detected under our hybridization conditions. However, a homology search revealed the presence of fis within the genome of H. influenzae, demonstrating its existence within nonenteric gram-negative bacteria.

The fis genes from K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris were synthesized by PCR, cloned, and sequenced (Fig. 1A). Subsequent PCR and DNA sequencing reactions confirmed the sequences of the first six codons in these four fis genes and of the last six codons in S. marcescens and E. carotovora fis. A comparison of these fis sequences together with those of E. coli, S. typhimurium, and H. influenzae showed 85 to 98%, identity with sequences from K. pneumoniae, S. typhimurium, and E. coli showing 97 to 98% identity. H. influenzae fis is about 67 to 73% identical to the various fis sequences in enteric bacteria. Most of the nucleotide differences occur at the third nucleotide codon positions, resulting in few changes in codon specificities.

Based on our DNA sequence data, the deduced Fis amino acid sequences from K. pneumoniae and S. marcescens are 100% identical to each other (Fig. 1B) as well as to those previously identified in E. coli and S. typhimurium (5, 38, 42). E. carotovora Fis contained only two amino acid changes with respect to Fis in all other enteric bacteria tested: residue 20 is alanine instead of the more common aspartic acid, and residue 48 is serine instead of asparagine. P. vulgaris also contained two amino acid differences compared to Fis in the other enteric bacteria: residue 14 is alanine instead of the more common serine, and residue 79 is glutamine instead of leucine. These results demonstrate that Fis is very highly conserved among enteric bacteria. The deduced Fis amino acid sequence for H. influenzae is about 80% identical and 90% similar to Fis in enteric bacteria. There are 19 residue differences in H. influenzae Fis compared with Fis in enteric bacteria, 9 of which are conservative changes.

Functional comparisons among the various bacterial Fis proteins.

Since the deduced Fis amino acid sequences from K. pneumoniae and S. marcescens were identical to those in E. coli and S. typhimurium, we did not analyze these proteins further. However, it was of interest to examine the abilities of Fis from E. carotovora, P. vulgaris, and H. influenzae to mediate some of the known functions of Fis in E. coli. Hence, their respective genes were cloned into a pKK223-3-based expression vector, which allows expression to be under the control of the isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible tac promoter, to make pMB283, pMB284, and pMB285 and transformed into various E. coli strains. However, based on Western blot analysis and Coomassie blue staining of total proteins, only expression of E. coli and H. influenzae fis from pRJ807 and pMB283, respectively, could be detected in vivo. It was possible that codon usage in P. vulgaris and E. carotovora fis limited their expression in E. coli. We therefore introduced the minimum nucleotide changes within E. coli fis to make pMB314 and pMB315 encoding P. vulgaris and E. carotovora Fis, respectively. Based on Western blot analysis, noninduced intracellular levels of Fis derived from these plasmids are comparable (within twofold) to those obtained with pRJ807 (results not shown). Noninduced levels from pRJ807 are also comparable to those of chromosomally encoded fis in E. coli or S. typhimurium during mid-logarithmic growth phase (41, 42). Therefore, IPTG was not used in assays examining Fis function in vivo.

To qualitatively examine the ability of these proteins to stimulate Hin-mediated DNA inversion, we transformed RJ2539 with pRJ807, pMB314, pMB315, pMB283, or pRJ1122. This strain contains a lacZ fusion to the S. typhimurium DNA invertible region present within the E. coli chromosome, such that the promoter contained within this region transcribes away from lacZ (41). Hence, RJ2539 cells grow as white colonies on MacConkey-lactose agar medium. However, when fis is supplied in trans on a plasmid, DNA inversion may be stimulated, resulting in expression of lacZ and growth of red colonies on MacConkey-lactose. As expected, E. coli fis in pRJ807 yielded fully red colonies after 36 h of growth at 37°C, whereas the control plasmid pRJ1122 (lacking fis) yielded only white colonies even after 96 h. After 48 h of growth, P. vulgaris fis in pMB314 yielded red colonies and H. influenzae fis in pMB283 gave colonies with red centers (Table 2). After 96 h of growth, E. carotovora fis in pMB315 gave colonies that were mostly white with very small red centers. These results indicate that P. vulgaris and H. influenzae fis are capable of stimulating Hin-mediated DNA inversion with various efficiencies, whereas E. carotovora fis is almost completely unable to mediate this function.

TABLE 2.

Functional analysis of various different Fis proteins

| Plasmid | Fis protein | Hin- mediated inversiona | λ phage yield (PFU/ml) |

fis P repression

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Galb | % Repres-sionc | ||||

| pRJ807 | E. coli | ++++ | 5 × 1010 | 255 ± 25 | 100 |

| pRJ1122 | None | − | 3 × 107 | 719 ± 38 | 0 |

| pMB314 | P. vulgaris | +++ | 1 × 109 | 196 ± 8 | 113 |

| pMB315 | E. carotovora | +/− | 3.5 × 1010 | 494 ± 25 | 49 |

| pMB283 | H. influenzae | ++ | 3 × 1011 | 326 ± 50 | 85 |

In vivo Hin-mediated inversion phenotypes were scored in RJ2539 carrying the indicated plasmids as follows: ++++, strong stimulation (red colonies within 36 h); +++ and ++, moderate levels of stimulation (red colonies within 36 to 60 h); +, very weak stimulation (colonies with small red centers within 72 to 96 h); −, no stimulation (colonies remain white after 96 h).

β-Galactosidase (β-Gal) activities are given in Miller units (35) and represent the means and standard deviations of three independent assays.

Percent repression is calculated with a 100% scale where β-galactosidase activity with pRJ122 (no repression) is set to 0% repression and the activity with pRJ807 (E. coli fis) is set to 100% repression.

The thermolysogenic strain RJ1765 carrying pRJ807 gave phage yields (5 × 1010 PFU/ml) more than 1,600-fold higher than in the same strain carrying pRJ1122 (Table 2). This effect has been attributed to a Fis-dependent stimulation of λ DNA excision from the chromosome (3). Similarly, when E. carotovora fis was supplied in pMB315, phage yields (3.5 × 1010 PFU/ml) were more than 1,100-fold higher than in the absence of fis. The H. influenzae fis in pMB283 showed the greatest effect, with about a 10,000-fold increase in phage yield (3 × 1011 PFU/ml). However, P. vulgaris fis caused only about a 33-fold increase in phage yields (1 × 109 PFU/ml). These results indicate that the E. carotovora and H. influenzae fis are able to efficiently stimulate λ excision, while the P. vulgaris fis gives relatively lower levels of stimulation compared to E. coli fis in pRJ807.

A third function tested was the ability of Fis to repress transcription from the E. coli fis promoter fused to lacZ on the chromosome in RO796. In the absence of fis (with pRJ1122), these cells yielded 719 U of β-galactosidase activity (Table 2). The E. coli, P. vulgaris, H. influenzae, and E. carotovora fis resulted in 255, 196, 326, and 493 U of β-galactosidase activity, respectively. Therefore, these Fis proteins were able to repress fis P to various extents; P. vulgaris Fis was the most efficient repressor, and E. carotovora Fis was the least efficient.

ORF1 sequences.

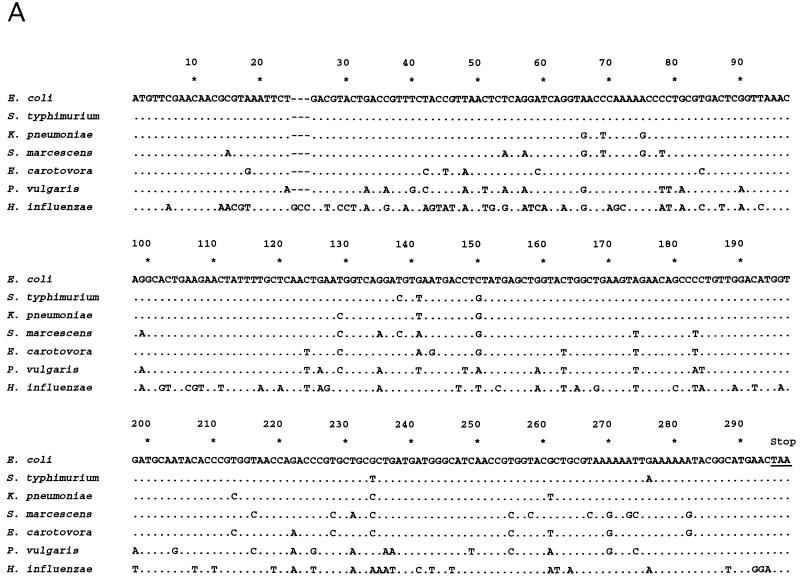

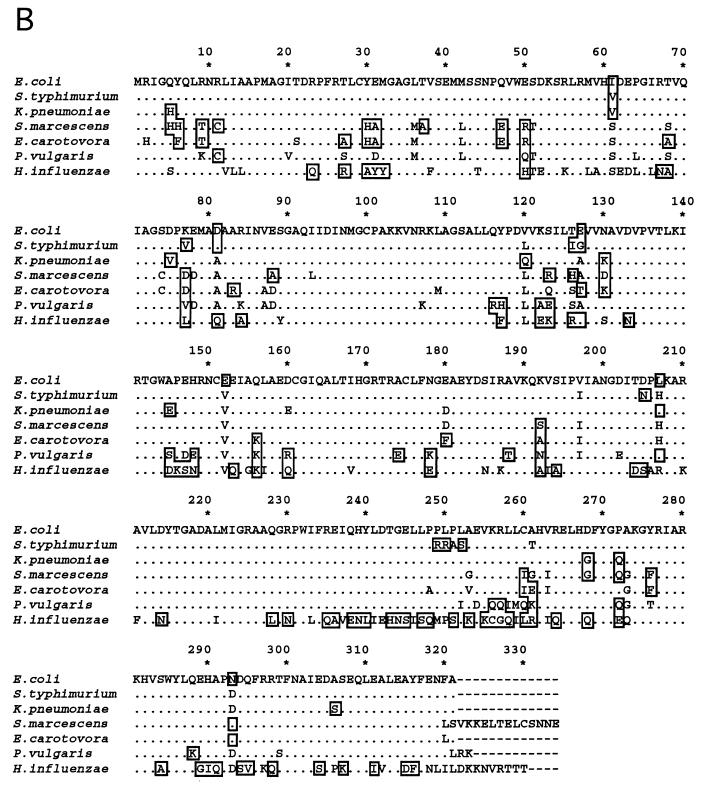

DNA sequences for ORF1, known to precede fis on the E. coli chromosome (5, 38), were obtained from K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris by PCR (Fig. 2A). In each case, ORF1 was found to be either immediately upstream or overlapping the first six codons of fis (Fig. 3A). ORF1 DNA sequences from E. coli, S. typhimurium, and K. pneumoniae show the greatest similarity among themselves (89 to 92% identity). These three sequences, in turn, are about 75 to 81% identical to ORF1 from S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris, and all these sequences are about 60 to 66% identical to that from H. influenzae.

FIG. 2.

DNA and deduced amino acid sequences of ORF1 from several bacteria. Sequence alignments are as described in the legend to Fig. 1. (A) Nucleotide sequences of ORF1. Termination codons for ORF1 are indicated by open boxes; initiation codons for fis are enclosed within ovals. Nucleotide positions are numbered on the right. Gaps would improve the sequence alignment in the intergenic regions. (B) Deduced ORF1 amino acid sequences. Residues identical to those in E. coli are indicated by dots; amino acid differences are shown by the appropriate letters. Nonconservative changes are boxed, while strictly conservative changes are not. Residue positions are shown above the sequence.

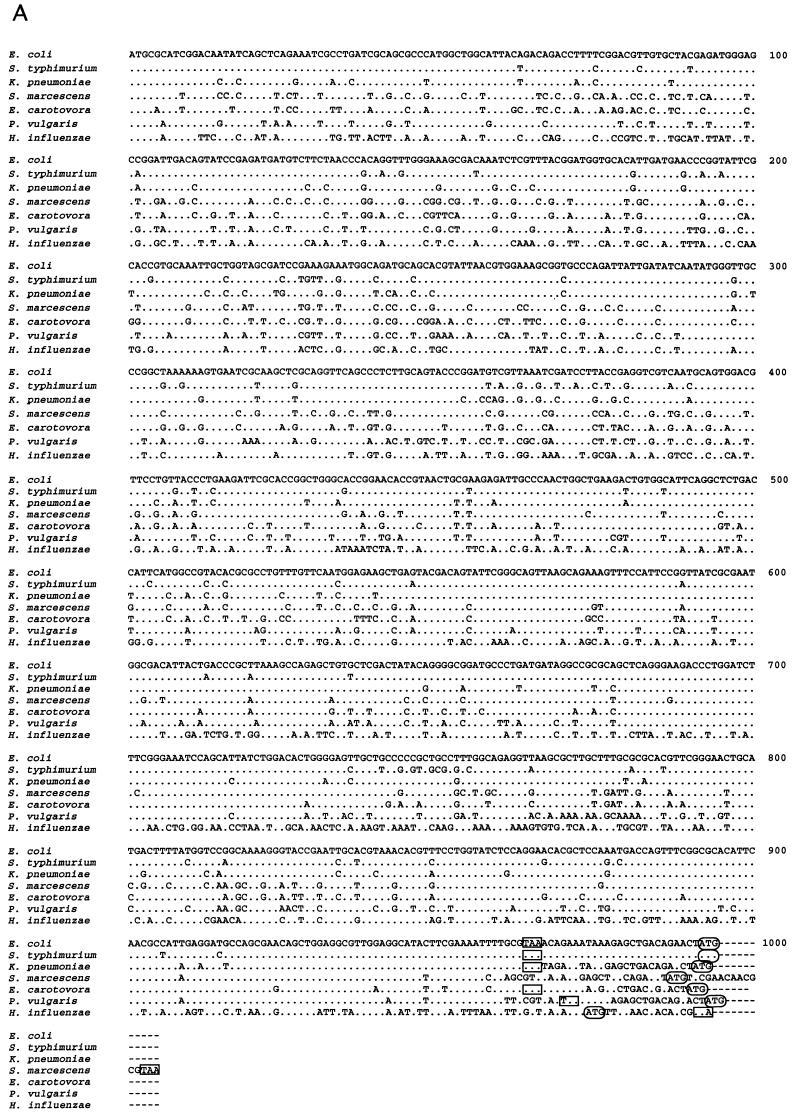

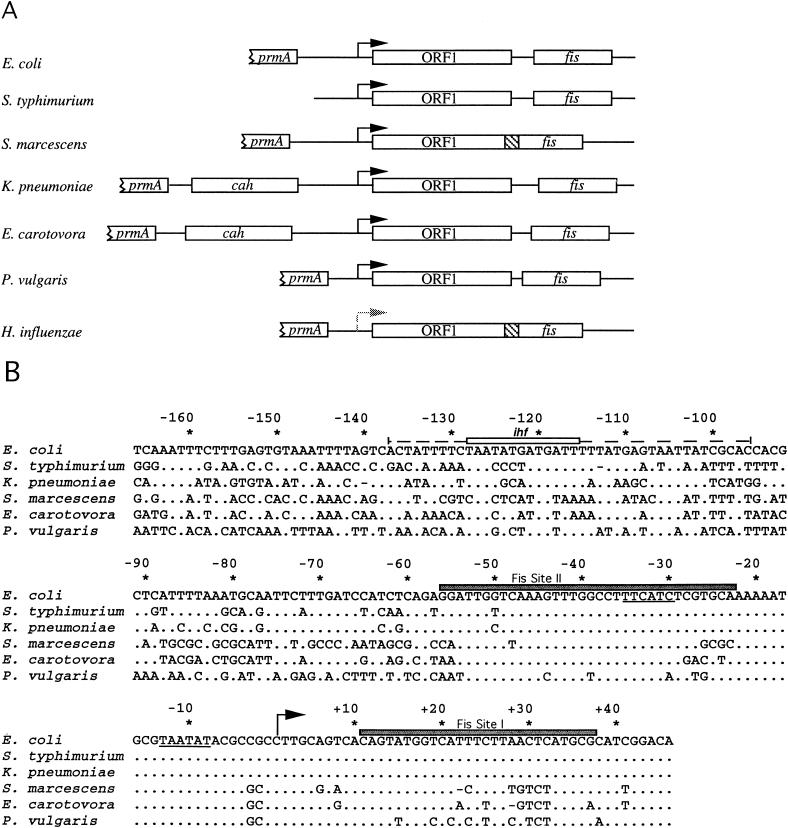

FIG. 3.

The fis operon and promoter region. (A) Schematic representation of the fis operons in various bacterial species. Black arrows represent promoters transcribing in the direction of ORF1 and fis; the shaded arrow represents a DNA region preceding the H. influenzae ORF1 which contains a good match to the consensus sequence for ς70 promoters, but its function in vivo remains untested. Relative positions in DNA regions corresponding to fis, ORF1, prmA, and cah are represented by open rectangles (not to scale). Regions where ORF1 and fis overlap are indicated by hatched boxes. (B) Nucleotide sequences of fis promoter regions from various bacteria. Sequence alignments are as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The arrow indicates the position of the predominant transcription start sites (+1). The nucleotide positions are numbered relative to this transcriptional start site, which represents an adjustment to a numbering used previously (5, 38, 45). Sequences resembling −10 and −35 promoter regions are underlined. Shaded rectangles represent two regions protected by Fis from DNase I cleavage in the E. coli fis P region, denoted Fis sites I and II (5). The open rectangle indicates a region containing a match to the ihf consensus sequence, and the broken line indicates the region protected by IHF from DNase I cleavage in the E. coli fis P region (45).

The deduced amino acid sequences from ORF1 in the various bacteria considered here vary in length: E. coli, S. typhimurium, K. pneumoniae, and E. carotovora ORF1 products are 321 residues long, while ORF1-encoded amino acid sequences from P. vulgaris, H. influenzae, and S. marcescens are 323, 330, and 334 residues long, respectively (Fig. 2B). Differences in length are attributed to variations in the position of the termination codon. K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and S. typhimurium ORF1-encoded amino acid sequences are 93 to 95% identical to each other and about 83 to 88% identical to those in S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris. The ORF1-encoded amino acid sequence from H. influenzae shows about 61 to 65% identity and 77 to 81% similarity to those from the rest of the enteric bacteria analyzed here. These results demonstrate that ORF1 is well conserved in these bacteria, suggesting that the protein it encodes plays an important role. Certain regions of the ORF1-encoded proteins show particularly high levels of conservation (Fig. 2B) and may be important for the preservation of their overall structure and function.

fis promoter sequences.

In E. coli (55) and H. influenzae, the gene encoding the ribosomal protein L11 methyltransferase (prmA) is located upstream of the fis promoter region. Therefore, we attempted to obtain fis promoter sequences from K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris by PCR with degenerate primers that annealed to a region near the 3′ end of prmA and primers that annealed near the 5′ end of ORF1. These DNA products were cloned upstream of the (trp-lac)W200 fusion in pRJ800 and sequenced. In all these constructs, sequences closely resembling the E. coli fis promoter were found to precede ORF1, suggesting that the fis operon structure has been conserved (Fig. 3). However, prmA immediately precedes the fis promoter region only in E. coli, S. marcescens, and P. vulgaris (Fig. 3A). In K. pneumoniae and E. carotovora, the gene encoding carbonic anhydrase (cah) resides between prmA and the fis P region. In H. influenzae, sequences preceding ORF1 show little or no resemblance to the fis P region in E. coli. However, sequences resembling a ς70-dependent −10 (TATAAA) and −35 (TTGTCG) promoter sequence with a 17-bp spacing can be identified 34 bp upstream of ORF1, suggesting that the overall operon structure has been preserved in this organism as well. The DNA sequence corresponding to the E. coli fis P region from −53 to +27 is 99% identical among E. coli, S. typhimurium, and K. pneumoniae and about 84 to 89% identical among the other three enteric bacteria. Based on DNase I protection analysis, ς70 RNA polymerase binds to the E. coli fis P region from −50 to +22 (5). Thus, the high level of conservation in this region suggests that RNA polymerase may interact similarly with these promoter regions. In contrast, the fis P regions from −55 to −135 in these bacteria were only 32 to 70% identical, averaging 47% identity overall.

Transcription from the fis P regions.

Before examining the sequences thought to contain the various fis promoter regions, it was important to determine if other promoters that could significantly contribute to fis expression were present within ORF1. DNA fragments carrying only the sequences from the start codon of ORF1 to the beginning of fis from K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris were synthesized by PCR and cloned in pRJ800 such that a promoter transcribing in the direction of fis would be able to express the trp-lac fusion in this plasmid. Negligible levels of β-galactosidase activity (less than 10 Miller units) were detected when the plasmids containing these DNA sequences from K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, and E. carotovora were present in RJ1561 cells (RZ211 fis::Kan), indicating that these regions lacked promoter activity. The same DNA region from P. vulgaris gave low levels of β-galactosidase activity (35 U) when similarly cloned in pRJ800 and transformed into RJ1561, suggesting the presence of a very weak promoter in this region. However, even this activity represented less than 5% that obtained from the E. coli fis promoter in pRJ1070 (804 U) or pRJ1071 (794 U) present in RJ1561.

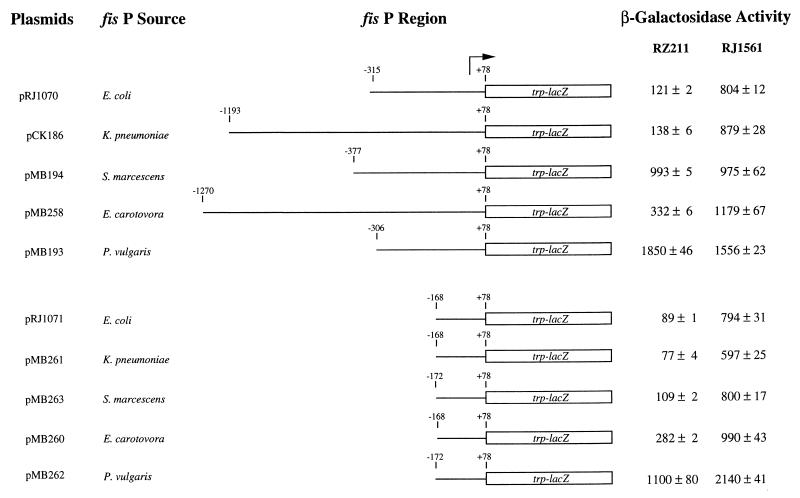

To determine if DNA sequences preceding ORF1 in these bacteria could function as promoters in vivo, the regions between ORF1 and the upstream prmA in these bacteria were cloned in pRJ800 to make pCK186, pMB194, pMB258, and pMB193 and tested for their ability to drive the expression of trp-lac in this plasmid. β-Galactosidase assays on RJ1561 containing these plasmids indicated that these DNA sequences generated significant transcription activity (Fig. 4). Therefore, these DNA regions contained promoters (fis P) that could originate the transcription of ORF1 and fis. β-Galactosidase activities were similar for E. coli (804 U), K. pneumoniae (879 U), and S. marcescens (974 U) fis P regions; in E. carotovora and P. vulgaris, transcription was about 1.5-fold (1,179 U) and 1.9-fold (1,556 U) higher, respectively, than that in E. coli. In the presence of Fis (RZ211), β-galactosidase activities generated from the E. coli (121 U) and K. pneumoniae (138 U) fis P regions were similar, whereas the fis P regions from E. carotovora, S. marcescens, and P. vulgaris, gave 2.7-fold (332 U), 8.2-fold (993 U), and 15-fold (1,850 U) higher β-galactosidase levels, respectively, compared to the E. coli fis P.

FIG. 4.

β-Galactosidase activities from various fis P regions. fis P regions fused to trp-lacZ (in pRJ800) are schematically represented. The arrow represents the position of fis P. Numbers above the lines indicate nucleotide positions relative to the start of transcription. The plasmids used and bacterial sources of the fis P regions they contain are listed on the left. β-Galactosidase activities are given in Miller units for RZ211 and RJ1561 (RZ211fis) carrying each of the DNA constructs. Values represent means and standard deviations from at least three independent assays. pRJ800 vector alone gives 3 ± 0.2 and 6 ± 0.5 U in RZ211 and RJ1561, respectively.

Plasmid copy numbers for several pRJ800-derived plasmids have been compared in RZ211 and RJ1561 and found to be very similar (within 8% of each other [45]). When β-galactosidase activities measured in RZ211 and RJ1561 carrying different fis promoter regions in plasmids pRJ1070, pCK186, and pMB258 were compared, negative regulation by Fis could be observed in each case (Fig. 4). However, Fis repression was not observed if these two strains carried pMB194 (S. marcescens fis P) or pMB193 (P. vulgaris fis P). Because DNA sequences used in these comparisons were of variable lengths, the significance of the discrepancies in Fis repression was uncertain. Since we had previously shown that the important regulatory sequences for the E. coli fis P reside in the region from −168 to +78 relative to the predominant transcription start site (45), we synthesized shorter DNA fragments containing the various fis P regions from either −172 or −168 to +78 and fused them to the (trp-lac)W200 sequence in pRJ800 to make pMB260, pMB261, pMB262, and pMB263. Again, transcription activity was detected in all cases (Fig. 4). However, in these constructs, Fis repression could be detected in all the promoters. This effect was highest with the E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and S. marcescens fis P regions, ranging from 8.9- to 7.3-fold reduction in transcription activity, but was only 3.5-fold with the E. carotovora and 2.2-fold with P. vulgaris fis P regions.

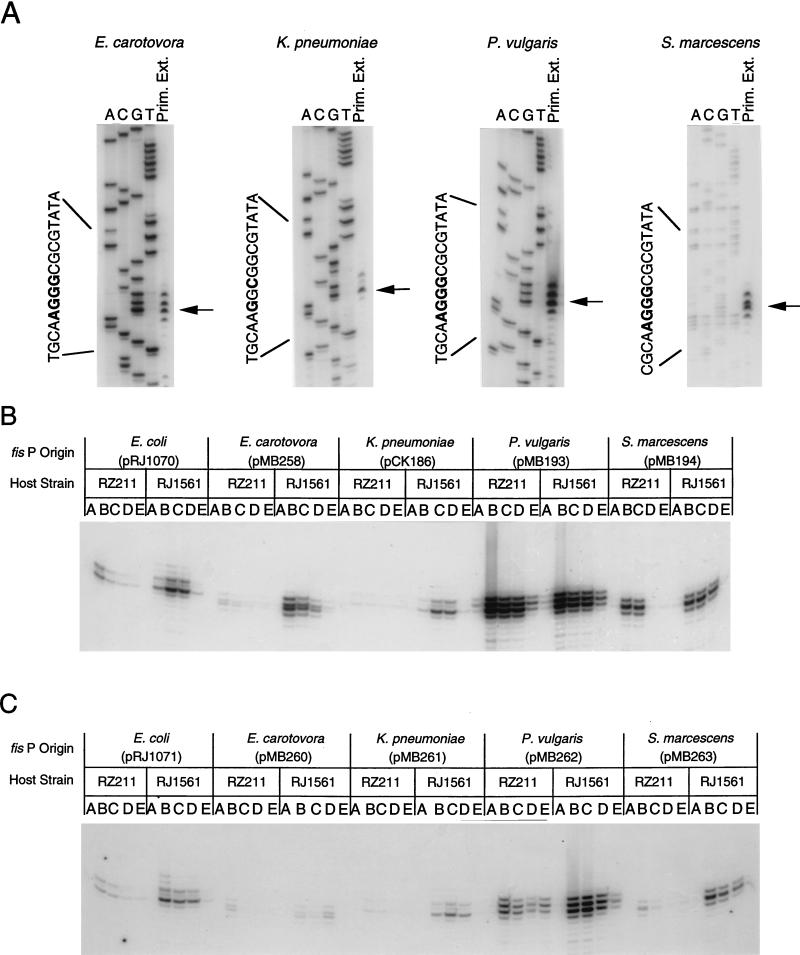

The most dramatic effect of having deleted DNA sequences upstream of −172 was observed for the S. marcescens fis P region. In this case, the DNA region from −377 to +78 in pMB194 showed no Fis regulation, whereas the region from −172 to +78 in pMB263 showed a 7.3-fold repression. A less dramatic yet similar effect was observed for the fis P region of P. vulgaris. No repression was noted with pMB193, but a 2.2-fold repression was seen with pMB262. To more precisely determine if these effects occurred at the fis promoter, primer extension analysis was performed to detect mRNA levels initiating at fis P. Transcription initiating at fis P could be detected in all promoters analyzed (Fig. 5A). When the longer fis promoter regions were used, Fis repression could be observed with E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and E. carotovora fis P but not with P. vulgaris fis P and slightly with S. marcescens fis P (Fig. 5B). However, when the shorter fis promoter regions were analyzed, Fis repression could be detected for all enteric bacteria, with the smallest effect observed for the P. vulgaris fis P (Fig. 5C). These results are consistent with those of the β-galactosidase assays and suggest that the observed differences in β-galactosidase activities in RZ211 and RJ1561 can be attributed to differences in regulation of the fis promoters themselves. These observations point to a complex mechanism of regulation by Fis on these promoters that are not yet understood. Seemingly, sequences upstream of −172 in the P. vulgaris and S. marcescens fis P regions are capable of interfering with the ability of Fis to regulate transcription at fis P.

FIG. 5.

Primer extension analysis of E. carotovora, K. pneumoniae, P. vulgaris, and S. marcescens fis promoter regions. (A) Primer extension analyses were performed with 32P-labeled primers specific for each fis promoter region and 10 μg of total RNA obtained from RJ1561 carrying pMB258, pCK186, pMB193, or pMB194. The respective sources of fis promoters contained in these plasmids are indicated above the gels. DNA-sequencing reactions from each promoter region were performed with the same specific primers, and the products were electrophoresed in parallel with primer-extended products on 8% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gels. Lanes containing sequencing reaction products for A, C, G, and T or primer extension products (Prim. Ext.) are labeled accordingly. Arrows point to major primer extension signals. Nucleotide positions of transcriptional start sites are shown in bold on the sequences of antisense strands on the left side of each data set. (B) Primer extension analyses were performed with 10 μg of RNA isolated from RZ211 or RJ1561 (RZ211fis) carrying (from left to right) pRJ1070, pMB258, pCK186, pMB193, or pMB194. Bacterial sources of fis P regions are indicated at the top. Host strains (RZ211 or RJ1561) are also indicated above the gels. Lanes A contain primer extension reaction mixtures with RNA isolated after 18 h of growth in LB, and lanes B to E contain primer extension reaction mixtures with RNA isolated after 45, 100, 150, and 300 min of growth, respectively. (C) Primer extension analyses were as in panel B, except that shorter versions of fis P regions (in pRJ1071, pMB260, pMB261, pMB262, and pMB263 [from left to right]) were analyzed instead.

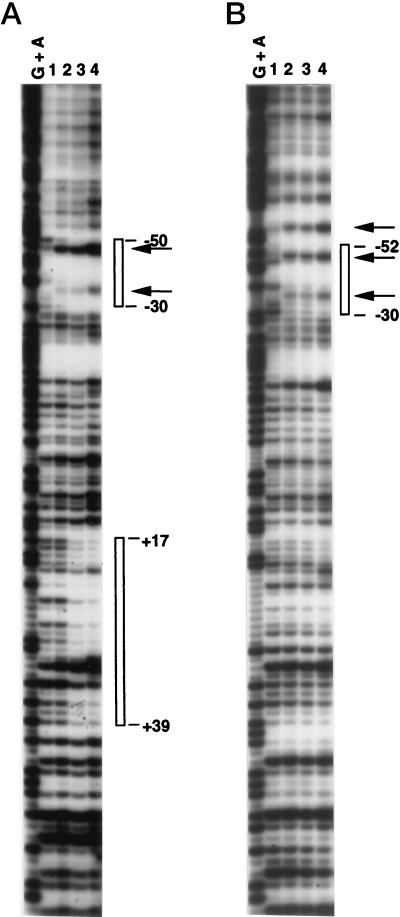

In the E. coli fis P region, Fis binding sites I (from +11 to +37) and II (from −56 to −23) play significant roles in autoregulation (38, 45). While Fis site II is very well conserved in all the fis promoters analyzed here, some variations exist in the region corresponding to Fis site I in S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris (Fig. 3B), with the most severe disruptions to the Fis consensus sequence occurring in P. vulgaris. To determine if a correlation could exist between Fis repression and the ability of Fis to bind to sites I and II, we performed DNase I protection experiments with a DNA fragment containing the strongly repressed K. pneumoniae fis P and a fragment containing the poorly repressed P. vulgaris fis P (Fig. 6). The results show that Fis sites I and II are protected from DNase I cleavage by the E. coli Fis at the K. pneumoniae fis P, while only Fis site II is protected at the P. vulgaris fis P.

FIG. 6.

fis P regions protected by Fis from DNase I cleavage. EcoRI-BamHI DNA fragments containing the K. pneumoniae fis P region from −1193 to +78 (A) or the P. vulgaris fis P region from −306 to +78 (B) were used as substrates. The top strands (as shown in Fig. 3B) were labeled with 32P at their BamHI sites. DNase I cleavage reactions in lanes 1 to 4 were performed after addition of 0, 5, 10, and 20 ng of purified E. coli Fis, respectively. The products of Maxam-and-Gilbert DNA cleavage reactions for G + A were electrophoresed in parallel for sequence reference. Regions protected by Fis are indicated by open bars on the sides; the numbers indicate the nucleotide positions of protected boundaries. Arrows point to Fis-induced DNase I hypersensitivity signals.

Growth phase-dependent regulation could be observed in all the promoter constructs analyzed by primer extension (Fig. 5). In cells grown in batch culture for 16 h, mRNA originating at fis P was not detectable in most of the constructs and was barely detectable in P. vulgaris fis P in pMB193. However, when these cells were subcultured in LB, mRNA levels initiating at fis P became maximal during the early logarithmic growth phase (after 45 or 100 min) and declined thereafter, such that they were minimal or undetected by the time the cells entered the stationary phase (after 300 min in these experiments). P. vulgaris fis P generated detectable levels of mRNA after 300 min of growth in batch cultures. In this promoter, A replaces the C nucleotide that is present in all the other promoters at −30. This change creates a better match to the E. coli ς70 −35 promoter sequence in this region from TTCATC to TTCATA (matches to consensus underlined), which may be responsible for the higher transcription levels from this promoter.

Transcription from E. coli fis P can be stimulated about 3.8-fold by IHF (45). This requires IHF binding to a site centered at −116 relative to the transcription initiation site at fis P (Fig. 3B). Very similar sequences for ihf sites were found in the promoter regions of S. typhimurium, K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris (Table 3), suggesting that they might also be regulated by IHF. To examine this possibility, we measured β-galactosidase activity in MC4100 and HP4110 (MC4100 ihfA::Tn10) carrying pMB260, pMB261, pMB262, and pMB263 (Table 4). A 3-fold stimulation by IHF could be detected for fis P from K. pneumoniae, and a 2.4-fold stimulation could be detected for fis P from P. vulgaris. pRJ800-based plasmids have been found to have a slightly higher copy number (about 20% higher) in HP4110 than in MC4100 (45). Therefore, IHF stimulation effects in these two strains could represent a small underestimation. For fis P from S. marcescens and E. carotovora, no significant stimulation was observed.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of putative ihf sites

| Source of fis P region | ihf site sequencea |

|---|---|

| E. coli | AATCATCATATTA |

| S. typhimurium | AATCATAGGGTTA |

| K. pneumoniae | AATCATTGCATTA |

| S. marcescens | TTACAATGAGTTG |

| E. carotovora | TAACAATATGTTA |

| P. vulgaris | AAACATAGTCTTA |

| Consensus sequence | WATCAANNNNTTR |

The match to the ihf site sequence in the E. coli fis P region extends from −116 to −128 and was functionally verified based on deletions, point mutations, and DNase I protection analysis (45). These sequences are located at these same positions relative to the transcriptional start sites, except for that in S. typhimurium, which is 1 bp closer to the fis promoter. Matches to the ihf consensus sequence (10, 19–21) are underlined; mismatches are shown in bold.

TABLE 4.

Effect of IHF on fis promoter activities

| Source of fis P | Plasmid | β-Galactosidase activitya in:

|

Fold stimulationb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC4100 | HP4110 | |||

| E. coli | pRJ1028 | 456 ± 35 | 119 ± 9 | 3.8c |

| K. pneumoniae | pMB261 | 888 ± 177 | 295 ± 8.5 | 3.0 |

| S. marscecens | pMB263 | 890 ± 170 | 683 ± 202 | 1.3 |

| E. carotovora | pMB260 | 1,138 ± 34 | 902 ± 55 | 1.3 |

| P. vulgaris | pMB262 | 2,467 ± 384 | 1,033 ± 141 | 2.4 |

| None | pRJ800 | 17 ± 2 | 17 ± 12 | 1.0c |

β-Galactosidase activities are given in Miller units (35) and represent the means and standard deviations of three independent assays.

Fold IHF stimulation was calculated for each DNA construct by dividing the β-galactosidase activities in MC4100 cells by those in HP4110 (MC4100 ihfA) cells.

Determined previously (45).

DISCUSSION

fis operons in enteric bacteria.

The results presented in this paper demonstrate that very similar fis operons exist in the enteric bacteria K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris and that they are also very similar to those previously found in E. coli and S. typhimurium (5, 38, 42). The fact that the genome of the nonenteric bacterium H. influenzae also carries fis preceded by ORF1 indicates that these genes are not exclusive to enteric bacteria. However, we have not yet been able to detect fis in other nonenteric organisms such as B. subtilis, P. aeruginosa, V. cholerae, M. luteus, C. crescentus, and the eukaryote S. cerevisiae, suggesting that fis may not be ubiquitous among microorganisms or that its sequence varies substantially beyond the enteric bacteria. Indeed, fis and ORF1 in H. influenzae differ the most from the rest of the fis operons in enteric bacteria.

From a listing of DNA and amino acid sequence identities for 74 genes in E. coli and S. typhimurium (51), a mean value of 84.3% ± 6.1% DNA sequence identity and 92.7% ± 5.8% amino acid sequence identity can be obtained. Since ORF1 DNA and amino acid sequences in these two organisms are 91.8 and 95.3% identical, respectively, they are more highly conserved than average yet fall within expected values. However, there is an unusually high level of conservation of fis in these two organisms, since their DNA sequences are 98% identical and amino acid sequences are 100% identical. A similar high level of conservation (97% DNA sequence identity and 100% amino acid sequence identity) is observed between E. coli and K. pneumoniae and between S. typhimurium and K. pneumoniae. The number of nucleotide changes that do not alter the codon specificity (synonymous changes) in S. marcescens, E. carotovora, and P. vulgaris fis is somewhat larger. This results in slightly lower DNA sequence identities of about 91, 92, and 86% to fis in E. coli, S. typhimurium, and K. pneumoniae, respectively, while the amino acid sequence identities in these three species are still 100% for S. marcescens and 98% for E. carotovora and P. vulgaris. This striking conservation of fis could reflect a selective advantage conferred by its structure, allowing it to participate in processes as consequential as stimulating transcription from stable RNA promoters (36, 46), regulating initiation of DNA replication (15, 56), or altering the structure of the chromosomal DNA (50). However, it is also possible that fis was more recently acquired (e.g., by horizontal transfer) than most other genes in enteric bacteria. Perhaps consistent with this notion is the relatively high content of rare codons (ranging from 12% in E. coli to 33% in S. marcescens) and small number of synonymous changes in fis. Also, the G+C contents of fis from E. coli (47%), S. typhimurium (46%), K. pneumoniae (48%), S. marcescens (49%), and E. carotovora (48%) are lower than those of a large number of coding sequences obtained from CUTG (Codon Usage Tabulated from GenBank) in these organisms (51.6, 53.1, 56.7, 58.7, and 51.1%, respectively).

The deduced amino acid sequences for ORF1 examined in this work are also highly conserved, albeit not as highly as Fis. Recent BLAST searches within various DNA databases revealed that 26 other organisms, including S. cerevisiae and Caenorhabditis elegans, contained ORF1-like sequences (Table 5), suggesting that ORF1 is involved in functions that are beneficial to a variety of organisms. Very similar genes, referred to as nifR3 or nifR3-like, are found within the nifR3-ntrB-ntrC operon in Rhodobacter capsulatus and within the ORF1-ntrB-ntrC operons in Rhizobium leguminosarum and Azospirillum brasilense (17, 33, 43). Thus, it is possible that the function of ORF1 is somehow related to nitrogen-regulated processes. Nonetheless, the function of nifR3 in these organisms is also unknown. Interestingly, the C-terminal region of Fis is also very similar to the corresponding region of NTRC, a transcriptional regulator of nitrogen-activated promoters (39), suggesting a possible evolutionary relationship between fis operons and the nifR3-ntrB-ntrC operon. Aside from the organisms considered in this work, this search revealed sequences bearing significant resemblance to fis in Yersinia pestis, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Pasteurella haemolytica, Neisseria spp., and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

TABLE 5.

Organisms containing ORF1- or fis-like sequences

| Organisma | ORF1b | fisb |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | + | + |

| Salmonella typhimurium | + | + |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | + | + |

| Erwinia carotovora | + | + |

| Serratia marcescens | + | + |

| Proteus vulgaris | + | + |

| Yersinia pestis | + | + |

| Haemophilus influenzae | + | + |

| Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans | + | + |

| Pasteurella haemolytica | NAc | + |

| Neisseria meningitidis | + | + |

| Neisseria gonorrhea | + | + |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | + | + |

| Vibrio cholerae | + | |

| Helicobacter pylori | + | |

| Rhizobium leguminosarum | + | |

| Azospirillum brasilense | + | |

| Rhodobacter capsulatus | + | |

| Bacillus subtilis | + | |

| Deinococcus radiodurans | + | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | + | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | + | |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | + | |

| Clostridium acetobutylium | + | |

| Synechosystis sp. | + | |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | + | |

| Campylobacter jejuni | + | |

| Thermotoga maritima | + | |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | + | |

| Mycobacterium leprae | + | |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | + | |

| Treponema pallidium | + | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | +/− | |

| Caenorhabditis elegans | +/− |

Upon completion of this work, new ORF1 and fis sequences were identified from several other organisms included here based on BLAST searches.

+, clear homologue of the E. coli sequence; +/−, weaker match to the E. coli homologue.

NA, DNA region expected to contain ORF1 was not available.

Comparison of Fis functions.

Previous genetic and biochemical analysis of E. coli Fis demonstrated the existence of at least two functional regions (29, 41). A carboxy-terminal region, which included a helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif, was required for efficient DNA binding and bending and hence was essential for the stimulation of Hin-mediated DNA inversion, λ DNA excision from the chromosome, and repression of the fis promoter (5, 29, 41). However, the amino-terminal region was uniquely required for Hin-mediated DNA inversion, presumably because this region is required for specific contacts with the Hin recombinase during this process (41, 47). Apparently, only the DNA binding and bending functions of Fis are needed for stimulation of λ excision and perhaps also for fis P repression.

Because Fis in E. coli, S. typhimurium, K. pneumoniae, and S. marcescens are 100% identical, they are fully interchangeable. However, in E. carotovora Fis, Asp20, which is required only for DNA inversion mediated by the Hin family of recombinases (41, 47), is replaced with Ala. Indeed, we found that this protein is virtually unable to stimulate Hin-mediated DNA recombination in vivo. A second amino acid change is the replacement of Asn48 with Ser. Neither of these mutations caused a significant effect on the ability of Fis to stimulate λ DNA excision from the E. coli chromosome, which requires efficient DNA binding and bending. However, an approximately twofold reduction in its ability to repress fis P was reproducibly observed. Since the intracellular levels of this protein were comparable to or greater than those of E. coli Fis generated from pRJ807, the reduction in the ability to repress fis P could not be attributed to lower intracellular concentrations of E. carotovora Fis. It was previously shown that an N-terminal Fis region including Asp20 is not required for fis P repression (5). Perhaps Asn48 is somehow required to more efficiently repress transcription. The position of Asn48 in the crystal structure (14, 30, 31, 57) is such that it might participate in DNA contacts.

In P. vulgaris Fis, Ser14 is replaced with Ala and Leu79 is replaced with Gln. This protein is able to efficiently stimulate Hin-mediated DNA inversion and fis P repression and to weakly stimulate λ DNA excision. Since it had been previously shown that the amino-terminal region of Fis is not required for stimulation of λ excision (29, 41), the decrease in λ excision stimulation is probably due to the replacement of Leu79 with Gln. This residue forms part of the first helix of the helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif (helix C), and Gln at this position might somehow interfere with Fis binding at the λ Fis site. Interestingly, the relatively shorter side chain of Asn at this position in H. influenzae Fis allows efficient stimulation of λ excision.

The H. influenzae Fis contains 19 amino acid changes compared to the E. coli Fis. Six of these occur in the β-hairpin loop region from residues 10 to 25, including a replacement of Asp20 with Ser. Two of the substitutions occur in helix C at residues 79 and 81, and another occurs at residue 98, which has been proposed to possibly contact the DNA phosphate backbone (14). In spite of all these changes, this protein is able to efficiently promote λ DNA excision and fis P repression and to moderately stimulate Hin-mediated DNA inversion. These results, taken together, demonstrate that the high level of conservation of Fis sequences is not necessarily related to a strict conservation of function.

The fis promoter region.

A very highly conserved fis promoter region from −53 to +27, relative to the predominant transcriptional start site, was observed in the enteric bacteria examined. The fact that they all showed growth phase-dependent expression was not unexpected, since it was demonstrated that the E. coli fis P region from −38 to +5 carries sufficient information to generate this unusual expression pattern (38, 45). This also suggests that at least some of the functions played by Fis (and perhaps also the product of ORF1) in these bacteria are related to its growth phase-dependent expression. For instance, Fis stimulates transcription from rRNA and tRNA genes in E. coli (36, 46), a function that is most critical during exponential cell growth (2). On the other hand, constitutive fis expression in S. typhimurium and E. coli was found to be deleterious to cell viability during the stationary phase, suggesting that its misexpression can interfere with vital processes specific to the stationary phase (5, 42).

Results from both primer extension analyses and β-galactosidase assays showed that the transcription activity of P. vulgaris fis P was significantly higher than that of the other fis promoters. A comparison of the minimal promoter sequences revealed six nucleotides that are unique to P. vulgaris fis P (Fig. 3B). Of these, −30A might contribute to this increase, since it creates an improved −35 promoter sequence in this region. It is also possible that sequences upstream of −53 (which differ significantly among all fis promoters) contribute to positive regulation of the P. vulgaris fis promoter.

Fis repression was detected for all fis promoters when the short constructs (from −168 or −172 to +78) were assayed, although their regulation efficiencies varied. This effect was highest for fis P from E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and S. marcescens (7.3- to 8.9-fold), moderate from E. carotovora (3.5-fold), and lowest from P. vulgaris (2.2-fold). DNase I protection analysis showed that Fis binds the K. pneumoniae fis P regions corresponding to Fis sites I and II, whereas only the Fis site II is bound in the P. vulgaris fis P region. Thus, the reduction in the repression efficiency of P. vulgaris fis P can be attributed to the loss of Fis site I in this promoter. Curiously, results of both β-galactosidase and primer extension assays indicate that the presence of sequences upstream of −173 in the S. marcescens fis P region may somehow prevent repression by Fis. A similar yet less dramatic effect was observed when sequences upstream of −173 were also present in the P. vulgaris fis P region. DNA deletion analysis of this region might help to better characterize this effect.

Stimulation by IHF also varied in these promoters. In the presence of IHF, transcription from E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. vulgaris fis promoters was stimulated with different efficiencies (3.8- to 2.4-fold). However, the presence of IHF caused only a slight stimulatory effect (1.3-fold) on the S. marcescens and E. carotovora fis promoters. Both the P. vulgaris and S. marcescens ihf sites centered at −116 contain only two mismatches from the E. coli ihf consensus sequence (Table 3), whereas the ihf sites for all other fis promoters contain only one mismatch. Thus, the lack of IHF stimulation in S. marcescens and E. carotovora were unexpected. It is possible that a more efficient stimulation by IHF occurs with these promoters in their natural hosts.

Clearly, information provided by DNA sequences surrounding the fis promoter in the various enteric bacteria confers differences in the level of transcription and their responses to Fis and IHF regulation. However, growth phase-dependent regulation is retained in the various fis promoters examined, and similar expression patterns will probably be observed in their natural hosts.

The origin of fis and its distribution among microorganisms remain uncertain. BLAST searches revealed additional organisms that contain ORF1 and fis. Although the upstream ORF1 appears to be more widespread among bacteria and even among certain simple eukaryotic organisms, fis has been found only in enteric bacteria, the closely related H. influenzae, A. actinomycetemcomitans, and Pasteurella haemolytica, and in Neisseria spp. and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Table 5). Nevertheless, by use of less stringent detection methods than those used here, fis may be found in more divergent bacteria. fis may reside within other operon contexts in other bacteria, or it may have been fragmented to become segments of other genes. Consistent with the latter notion is the finding that the carboxy-terminal portion of Fis is similar to the carboxy-terminal portion of NTRC (39).

The potential role that the abundant nucleoid-associated proteins could play in compacting the bacterial chromosome clearly underscores their importance. Surprisingly, however, null mutations in genes encoding NAPs in E. coli (with the exception of H-NS [32]) generally have minor consequences for the cell (12, 16, 49). This may reflect a certain amount of functional redundancy among these proteins. HU, IHF, and H-NS can be found among the enteric bacteria and some gram-negative nonenteric bacteria, including various types of purple bacteria. HU-like proteins have even been found in Bacillus stearothermophilus and Anabaena spp. (12). Some E. coli NAPs may be functionally similar to other DNA binding proteins in other organisms. For example, the mammalian HMG1 and HMG2 proteins and their homologues in S. cerevisiae and the trypanosome Crithidia fasciculata can efficiently replace HU in its ability to facilitate DNA looping during Hin-mediated DNA inversion (44). In B. subtilis, the small DNA binding protein AbrB resembles Fis in that it is transcriptionally activated by environmental conditions in a growth phase-dependent manner, particularly in the period spanning the transition between the lag and exponential growth phases (40). Thereafter the levels of AbrB transcript decrease sharply, although its protein levels decrease gradually. In addition, this protein regulates the expression of a number of other genes (53). Hence, despite their lack of sequence similarity, AbrB is a good candidate for a B. subtilis NAP that may replace Fis. It is likely that other functional analogs of the E. coli NAPs will continue to be found in other organisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. McEntee (University of California, Los Angeles) for supplying chromosomal DNA samples from various microorganisms. Sequence data for H. influenzae fis operon were obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research website at http://www.tigr.org. We thank various members of our laboratory: C. Koniaris for synthesizing and cloning fis P from K. pneumoniae, T. S. Pratt for assisting in certain aspects of this work, and K. A. Walker for helpful revisions.

This work was supported by funds from PHS grant GM52051.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appleman J A, Ross W, Salomon J, Gourse R L. Activation of Escherichia coli rRNA transcription by FIS during a growth cycle. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1525–1532. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.6.1525-1532.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ball C A, Johnson R C. Efficient excision of phage lambda from the Escherichia coli chromosome requires the Fis protein. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4027–4031. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.4027-4031.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ball C A, Johnson R C. Multiple effects of Fis on integration and the control of lysogeny in phage λ. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4032–4038. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.4032-4038.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ball C A, Osuna R, Ferguson K C, Johnson R C. Dramatic changes in Fis levels upon nutrient upshift in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:8043–8056. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.24.8043-8056.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruist M F, Glasgow A C, Johnson R C, Simon M I. Fis binding to the recombinational enhancer of the Hin DNA inversion system. Genes Dev. 1987;1:762–772. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.8.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruist M F, Simon M I. Phase variation and the Hin protein: in vivo activity measurements, protein overproduction and purification. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:71–79. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.1.71-79.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Case C C, Roels S M, Gonzalez J E, Simons E, Simons R. Analysis of the promoters and transcripts involved in IS10 anti-sense transcriptional RNA control. Gene. 1988;72:219–236. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claret L, Rouviere-Yaniv J. Variation in HU composition during growth of Escherichia coli: the heterodimer is required for long term survival. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:93–104. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craig N L, Nash H A. E. coli integration host factor binds to specific sites in DNA. Cell. 1984;39:707–716. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90478-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ditto M D, Roberts D, Weisberg R A. Growth phase variation of integration host factor level in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3738–3748. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.12.3738-3748.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drlica K, Rouviere-Yaniv J. Histonelike proteins of bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:301–319. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.3.301-319.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falconi M, Brandi A, Teana A L, Gualerzi C O, Pon C L. Antagonistic involvement of FIS and H-NS proteins in the transcriptional control of hns expression. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:965–975. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.436961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng J-A, Yuan H S, Finkel S E, Johnson R C, Kaczor-Grzeskowiac M, Dickerson R E. The interaction of Fis protein with its DNA-binding sequences. In: Sarma R H, Sarma M H, editors. Structure and function. 2. Proteins. Schenectady, N.Y: Adenine Press; 1992. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filutowicz M, Ross W, Wild J, Gourse R L. Involvement of Fis protein in replication of the Escherichia coli chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:398–407. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.398-407.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finkel S E, Johnson R C. The Fis protein: it’s not just for DNA inversion anymore. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3257–3265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster-Hartnett D, Gabbert K K, Cullen P J, Kranz R G. Sequence, genetic, and lacZ fusion analyses of a nifR3-ntrB-ntrC operon in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:903–914. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Free A, Dorman C J. Coupling of Escherichia coli hns mRNA levels to DNA synthesis by autoregulation: implications for growth phase control. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:101–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18010101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedman D I. Integration host factor: a protein for all reasons. Cell. 1988;55:545–554. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodrich J A, Schwartz M L, McClure W R. Searching for and predicting the activity of sites for DNA binding proteins: compilation and analysis of the binding sites for Escherichia coli integration host factor (IHF) Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4993–5000. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.17.4993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goosen N, Van de Putte P. The regulation of transcriptional initiation by integration host factor. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gosink K K, Gaal T, Bokal IV A J, Gourse R L. A positive control mutant of the transcription activator protein FIS. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5181–5187. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5182-5187.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gosink K K, Ross W, Leirmo S, Osuna R, Finkel S E, Johnson R C, Gourse R L. DNA binding and bending are necessary but not sufficient for Fis-dependent activation of rrnB P1. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1580–1589. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1580-1589.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartz D, McPheeters D S, Traut R, Gold L. Extension inhibition analysis of translation initiation complexes. Methods Enzymol. 1988;164:419–425. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(88)64058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson R C, Ball C A, Pfeiffer D, Simon M I. Isolation of the gene encoding the Hin recombinational enhancer binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:3484–3488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.10.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson R C, Bruist M F, Simon M I. Host protein requirements for in vitro site-specific DNA inversion. Cell. 1986;46:531–539. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90878-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson R C, Simon M I. Hin-mediated site-specific recombination requires two 26 bp recombination sites and a 60 bp recombinational enhancer. Cell. 1985;41:781–791. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson R C, Yin J C P, Reznikoff W S. Control of Tn5 transposition in Escherichia coli is mediated by protein from the right repeat. Cell. 1982;30:873–882. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koch C, Ninnemann O, Fuss H, Kahmann R. The N-terminal part of the E. coli DNA binding protein Fis is essential for stimulating site-specific DNA inversion but is not required for specific DNA binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5915–5922. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.21.5915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kostrewa D, Granzin J, Koch C, Choe H W, Raghunathan S, Wolf W, Labahn J, Kahmann R, Saenger W. Three-dimensional structure of the E. coli DNA binding protein FIS. Nature (London) 1991;348:178–180. doi: 10.1038/349178a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kostrewa D, Granzin J, Choe H W, Labahn J, Saenger W. Crystal structure of the factor for inversion stimulation FIS at 2.0 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:209–226. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lejeune P, Danchin A. Mutations in the bglY gene increase the frequency of spontaneous deletions in Escherichia coli K-12. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:360–363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Machado H B, Yates M B, Funayama S, Rigo L U, Steffens M B, Souza E M, Pedrosa F O. The ntrBC genes of Azospirillum brasilense are part of a nifR3-like-ntrB-ntrC operon and are negatively regulated. Can J Microbiol. 1995;41:674–684. doi: 10.1139/m95-093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maxam A, Gilbert W. A new method for sequencing DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:560–564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.2.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nilsson L, Vanet A, Vijgenboom E, Bosch L. The role of Fis in trans activation of stable RNA operons in E. coli. EMBO J. 1990;9:727–734. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nilsson L, Verbeek H, Vijgenboom E, van Drunen C, Vanet A, Bosch L. Fis-dependent trans activation of stable RNA operons of Escherichia coli under various growth conditions. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:921–929. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.921-929.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ninnemann O, Koch C, Kahmann R. The E. coli fis promoter is subject to stringent control and autoregulation. EMBO J. 1992;11:1075–1083. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.North A K, Klose K E, Stedman K M, Kustu S. Prokaryotic enhancer-binding proteins reflect eukaryote-like modularity: the puzzle of nitrogen regulatory protein C.J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:4267–4273. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.14.4267-4273.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Reilly M, Devine K M. Expression of AbrB, a transition state regulator from Bacillus subtilis, is growth phase dependent in a manner resembling that of Fis, the nucleoid binding protein from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:522–529. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.522-529.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osuna R, Finkel S E, Johnson R C. Identification of two functional regions in Fis: the N-terminus is required to promote Hin-mediated DNA inversion but not λ excision. EMBO J. 1991;10:1593–1603. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07680.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Osuna R, Lienau D, Hughes K, Johnson R C. Sequence, regulation, and functions of fis in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2021–2032. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2021-2032.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patriarca E J, Riccio A, Taté R, Colonna-Romano S, Iaccarino M, Defez R. The ntrBC genes of Rhizobium leguminosarum are part of a complex operon subject to negative regulation. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:569–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paull T T, Haykinson M J, Johnson R C. HU and functional analogs in eukaryotes promote Hin invertasome assembly. Biochimie. 1994;76:992–1004. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(94)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pratt T S, Steiner T, Feldman L S, Walker K A, Osuna R. Deletion analysis of the fis promoter region in Escherichia coli: antagonistic effects of integration host factor and Fis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6367–6377. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6367-6377.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ross W J, Thompson J F, Newlands J T, Gourse R L. E. coli Fis protein activates ribosomal RNA transcription in vitro and in vivo. EMBO J. 1990;9:3733–3742. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Safo M K, Yang W-Z, Corselli L, Cramton S E, Yuan H S, Johnson R C. The transactivation region of the Fis protein that controls site-specific DNA inversion contains extended mobile β-hairpin arms. EMBO J. 1998;16:6860–6873. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.22.6860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmid M B. More than just “histone-like” proteins. Cell. 1990;63:451–453. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90438-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]