Abstract

ROS1 rearrangement is found in 0.9%–2.6% of people with non-small-cell lung cancers (NSCLCs). Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) target ROS1 and can block tumor growth and provide clinical benefits to patients. This review summarizes the current knowledge on ROS1 rearrangements in NSCLCs, including the mechanisms of ROS1 oncogenicity, epidemiology of ROS1-positive tumors, methods for detecting rearrangements, molecular characteristics, therapeutic agents, and mechanisms of drug resistance.

Keywords: ROS1 rearrangement, fusion gene, tyrosine kinase inhibitor, drug resistance, non-small-cell lung cancer

1 Introduction

Lung cancer remains the most fatal malignant tumor, with approximately 85% of cases being non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Of those with NSCLC, about 25% carry positive-driven gene changes that can benefit from the corresponding molecular-targeted therapy (Siegel et al., 2022). Compared with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangements, the genetic proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase-1 (ROS1) is less prevalent in NSCLC, accounting for approximately 0.9%–2.6% of cases (Bergethon et al., 2012; Cai et al., 2013). The results of prospective Phase I/II clinical trials have confirmed the effectiveness of crizotinib in ROS1-positive NSCLC (Shaw et al., 2019a), and in recent years, several targeted drugs, including entrectinib, ceritinib, and lorlatinib, have also shown excellent antitumor activity (Shaw et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2020; Dziadziuszko et al., 2021). This article provides an overview of the progress regarding research on NSCLC with the ROS1 rearrangement.

2 ROS1 gene

The ROS1 gene was discovered in the 1980s in the products of bird myeloma virus RNA UR2 (Balduzzi et al., 1981). The human ROS1 gene is located on chromosome 6q21 (Nagarajan et al., 1986), which belongs to the family insulin receptor genes of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), which encode intermembrane proteins consisting of 2,347 amino acids, including hydrophobic extracellular domains, a transmembrane region, and intracellular parts of the tyrosine kinase domain (Roskoski, 2017). Rikova et al. first reported the role of the ROS1 oncogene in NSCLC in 2007 and identified two new protein fusion transcription factors, SLC34A2 and CD74 (Rikova et al., 2007). With the continuous improvement in modern sequencing technology, an increasing number of fusion species have been discovered, and their role as carcinogenic genes in multiple cancers has been gradually confirmed (Dagogo-Jack et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019).

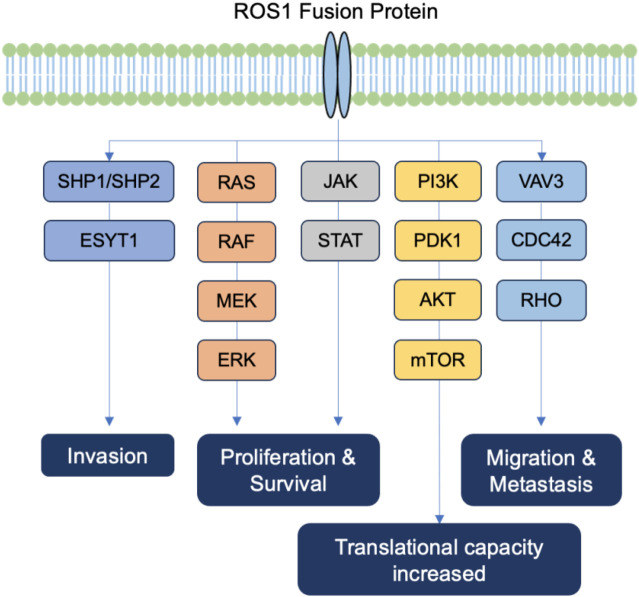

ROS1 plays an important role in activating multiple signaling pathways, including those involved in cell differentiation, proliferation, growth, and survival (Figure 1). ROS1 rearrangement causes disorders in enzyme-active proteins and the abnormal activation of the associated signaling pathways by forming phosphate thyroxine recruitment spots at the end of the ROS, including tyrosine phosphatase tumor suppressor SHP1/SHP2, pro-mitotic protein extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-1/2, insulin-receptor substrate (IRS)-1, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), protein kinase B (AKT), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-3, and the VAV3-related signaling pathway (Huang et al., 2020).

FIGURE 1.

The ROS1 signaling pathway.

3 Epidemiological and clinical features

Among the people with NSCLC in China, approximately 2.59% carry the ROS1 fusion gene, and approximately 17,000 new cases of ROS1-positive NSCLC are estimated to occur annually in China. ROS1 rearrangements are more common in young, female, and nonsmoking patients (Fu et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2015). The main pathological types are adhesive, vesicular, or solid glandular cancers; a few are squamous-cell, multicellular, or large-cell cancer (Park et al., 2019), more than 90% of which express thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1), mostly diagnosed as phase III–IV, high incidence of brain transfusions (Drilon et al., 2021). Compared to other types of NSCLC, ROS1-positive NSCLC has a significantly increased risk of developing thromboembolic diseases (Shah et al., 2021; Woodford et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2021), but the underlying mechanism remains unclear.

4 Molecular characteristics

4.1 Fusion partners

The most common fusion partners of the ROS1 gene include CD74 (38%–54%), EZR (13%–24%), SDC4 (9%–13%), and SLC34A2 (5%–10%) (Cui et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2021a). With the continuous improvement in DNA- and RNA-sequencing technology, new fusion partners have been discovered, such as CCCKC6, TFG, SLMAP, MYO5C, FIG, LIMA1, CLTC, GOPC, ZZCCHC8, CEP72, MLL3, KDELR2, LRIG3, MSN, MPRIP, WNK1, SLC6A17, TMEM106B, FAM135B, TPM3, and TDP52L1 (Li et al., 2018). People with NSCLC with the CD74–ROS1 rearrangement have longer progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) than those with other types of rearrangements (Li et al., 2018), but no similar conclusions have been found in other studies (Cui et al., 2020). Currently, the relationship between the fusion partners and prognosis remains unclear.

4.2 Co-occurring genetic mutations

Approximately 36% of people with NSCLC with ROS1 rearrangements have co-occurring genetic mutations. Those with co-mutation have a worse prognosis than non-co-mutant patients (PFS 8.5 months versus 15.5 months, p = 0.0213) (Zeng et al., 2018). ROS1 rearrangement typically does not simultaneously occur with mutations in other genes (such as EGFR, ALK, and KRAS). However, in recent years, occasional cases of ROS1 rearrangements associated with mutations in other driving genes have been reported (Zhu et al., 2016; Uguen et al., 2017). Lambros et al. reported 15 cases of NSCLC with an ROS1 mutation in conjunction with an EGFR mutation, including 9 cases of 19 deletion, 5 cases of L858R mutation, and 1 case of 20 insertion. ROS1 rearrangement may be one of the mechanisms of resistance to EGFR inhibitors, and the combination of EGFR inhibitors with crizotinib may be an effective treatment (Lambros et al., 2018). Crizotinib, as a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, binds to the ATP-binding site of the ROS1 kinase domain, inhibiting its enzymatic activity. By blocking ROS1 signaling, crizotinib disrupts the intracellular pathways that drive cancer cell proliferation and survival.

Co-mutations in both ROS1 and ALK are rare but occasionally reported. Both mutations were found to be sensitive to crizotinib, which may be a more suitable treatment option. Uguen et al. and Song et al. respectively reported a lung adenocarcinoma patient with concurrent ALK/ROS1 rearrangements confirmed by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analyses, and both patients showed response to crizotinib (Song et al., 2017; Uguen et al., 2017).

ROS1 and KRAS co-mutations are rare and can be primary or successive. In a study involving six patients with the KRAS–ROS1 comutation, only one patient benefitted from crizotinib treatment, while KRASG13D- or G12V-mutation carriers showed no response (Lin et al., 2017).

ROS1–MET comutations are extremely rare. Tang et al. reported one ROS-1–MET co-mutation in a series of 15 patients, however, no treatment information was provided (Tang et al., 2018). Rihawi et al. noted one case of NSCLC with a ROS1–MET co-mutation, and MET inhibitor capmatinib treatment failed, followed by crizotinib treatment, and a PFS of up to 11 months (Rihawi et al., 2018). Zeng et al. reported a case of NSCLC with ROS1 rearrangement and MET expansion, with disease progression occurring 1.5 months after crizotinib treatment (Zeng et al., 2018). Therefore, the combined use of highly selective MET inhibitors based on crizotinib treatment is necessary for patients with this type of comutation. Therefore, further clinical research and practice are required.

Comutations in ROS1 and BRAF have been reported, but no reports on combined treatment with an ROS1 inhibitor with BRAF inhibitors have been published (Wiesweg et al., 2017). Furthermore, it was reported that comutations with TP53 may be associated with a shorter survival time (Lindeman et al., 2018) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of co-occurring genetic mutation of ROS1.

| Co-occurring genetic mutation of ROS1 | Effect |

|---|---|

| ROS1-EGFR | ROS1 rearrangement may be one of the mechanisms of resistance to EGFR inhibitors; Combination of EGFR inhibitors with crizotinib may be effective |

| ROS1-ALK | Both mutations are sensitive to crizotinib, suggesting crizotinib as a potential treatment |

| ROS1-KRAS | Limited response to crizotinib; Variable treatment outcomes |

| ROS1-MET | Variable treatment outcomes; Combined use of highly selective MET inhibitors with crizotinib is necessary |

| ROS1-BRAF | Limited information on treatment outcomes; No published reports on combined treatment with ROS1 and BRAF inhibitors |

| ROS1-TP53 | Associated with a shorter survival time |

5 Methods of ROS1 detection

The detection of ROS1 is currently recommended in all patients with non-squamous-cell cancer to determine the indication for the selection of the corresponding targeted drug.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is the gold standard for diagnosing ROS1 rearrangements. FISH uses a two-probe (3′ and 5′) separation design and can detect ≥50 tumor cells; the result is considered positive when more than 15% of the cells show 3′- and 5′-probe separation or separate 3′ signals. The disadvantages of FISH include its high cost, technical difficulty, and time consumption. At present, probes that can detect both ROS1 and ALK rearrangements have been put into clinical use as they have less strict requirements for tumor samples (Ginestet et al., 2018; Zito Marino et al., 2020).

The immunohistochemistry (IHC) technique is commonly used to screen for ROS1 arrangements owing to its convenience, low cost, and ease of operation; IHC has a sensitivity of approximately 90%–100% and a specificity of approximately 70%–90%. False-positive outcomes may occur in one-third of patients, especially in those with adhesive or adenomatous EGFR-mutant glandular cancer (Wang et al., 2020; Makarem et al., 2021). Therefore, positive or suspicious IHC results require further confirmation by FISH, reverse -transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), or next-generation sequencing (NGS) (Hofman et al., 2019; Cheung et al., 2021; Fielder et al., 2022).

Two situations should be noted: 1) IHC positivity and FISH negativity, indicating the presence of another carcinogen-driven mutation not included in FISH detection and requiring further confirmation by RT-qPCR or NGS testing (Kim et al., 2021); 2) FISH may result in false-negative results for some fusion partners, mainly GOPC–ROS1 or EZR–ROS1. In the latter, the 5′-ROS1 gene is usually lacking, and the corresponding FISH detection uses a separate 3′ probe (Capizzi et al., 2019). In a recent study, the authors detected a rare case of NSCLC with ROS1 fusion (SQSTM1), ROS1 mutation, and ROS1 expansion with positive IHC expression using NGS technology (Huang et al., 2021b). Therefore, if the results remain uncertain after both IHC and FISH testing, NGS should be performed to confirm the presence of unusual fusion genotypes.

With RT-qPCR, the unique primers detecting ROS1 rearrangements are used; the method has a sensitivity of up to 100% and a specificity of 85.1%. The disadvantage of the method is its technical difficulty, requiring several steps, including RNA extraction, complementary DNA synthesis, quantitative PCR, and data analysis, which are currently more commonly applied in laboratories: few clinical applications are lacking (Shan et al., 2015).

NGS can be used to theoretically identify all fusion partners, including new variation types and other carcinogenic genetic variations. The requirements for the samples are no strict, and tumor tissues or blood plasma can be used as test samples. Recent advances in NGS technology for detecting ROS1 rearrangements involve both DNA and RNA approaches. DNA-based methods, such as targeted sequencing, whole exome sequencing (WES), and whole genome sequencing (WGS), target specific genomic regions or the entire genome to identify structural alterations. RNA-based techniques, including targeted RNA sequencing and RNA-Seq, directly detect fusion transcripts, providing valuable information on gene rearrangements. Hybrid approaches integrating DNA and RNA analyses enhance sensitivity and specificity. Improved bioinformatics tools and the use of single-molecule sequencing technologies contribute to increased accuracy, while emerging liquid biopsy methods offer less invasive options. Combining these approaches allows for a comprehensive and precise assessment of ROS1 rearrangements in lung cancer genomes (Clave et al., 2019). NGS was used to detect many novel uncommon ROS1 fusions, most of which were reported to be sensitive to matched targeted therapy, similar to the canonical fusions. The clinical significance of some genomic breakpoints remained unclear and could be explored further via NGS technology (Li et al., 2022). The disadvantages are that the cost is higher and the results cannot be quickly obtained (Mosele et al., 2020).

6 Treatment of NSCLC with ROS1 rearrangement

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved crizotinib and entrectinib as first-line treatments for patients with unresectable NSCLC with ROS1 rearrangements. Other tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), including ceritinib and lorlatinib, also exhibit excellent antitumor activity.

6.1 Crizotinib

Crizotinib is a small molecule inhibitor with a complex molecular structure. It contains various functional groups, including pyrazole, pyridine, and piperidine rings. The three-dimensional structure allows it to bind to the ATP-binding site of the ROS1 kinase domain, inhibiting its activity. The Phase I PROFILE 1001 study included 50 people with ROS1-positive advanced NSCLC receiving crizotinib (250 mg twice daily). The objective remission rate (ORR) was 72%; disease control rate (DCR) was 90%; median duration of response (DOR) was 24.7 months; and median PFS and OS were 19.3 months and 51.4 months, respectively. The most common adverse events included visual impairment (82%), diarrhea (44%), nausea (40%), edema (40%), constipation (34%), vomiting (34%), elevated transaminase (22%), fatigue (20%), and taste disturbance (18%). Most adverse reactions were grade 1 to 24.

Compared with the PROFILE 1001 study, in the AcSé Phase I/II study based on 37 patients, the effectiveness of crizotinib was relatively poor, with an ORR of 47.2%, and median PFS and OS of 5.5 and 17.2 months, respectively. The researchers presumed that more patients with a higher performance status (PS) score of two points (25% vs. 2%) were grouped in the AcSé study (Wu et al., 2018). The results of the EUCROSS and METROS studies from Europe were similar to those of the PROFILE 1001 study, with ORRs of 70% and 65%, and median PFS values of 20 and 22.8 months, respectively (Michels et al., 2019).

Although crizotinib showed excellent anti-tumor activity in the treatment of ROS1-positive NSCLC, its blood–brain barrier penetration rate was low, and brain metastases (47%) became the main area of disease progression. In addition, approximately 36% those with ROS1-positive NSCLCs also experienced brain metastases at the baseline level. Therefore, ROS1–TKIs that can better cross the blood–brain barrier should be developed in the future.

6.2 Entrectinib

Entrectinib is a multitarget inhibitor of ROS1, ALK, and pan-tropomyosin receptor kinase (TRK). Its molecular structure consists of various cyclic and aromatic structures, including a tetrahydropyrrolopyrazine ring. Entrectinib is designed to penetrate the blood-brain barrier, making it effective against central nervous system metastases. In in vitro experiments, its anti-ROS1 activity was 40 times stronger than that of crizotinib (Rolfo et al., 2015). The results of two Phase I/II studies showed antitumor activity and good tolerance to entrectinib (Drilon et al., 2017). The most common side effects included discomfort in taste (41.4%), fatigue (27.9%), dizziness (25.4%), constipation (23.7%), diarrhea (22.8%), nausea (20.8%), and weight gain (19.4%). The results of the STARTRK-2 study confirmed the efficacy of entrectinib in ROS1-positive NSCLC involving a total of 161 patients who had not previously received anti-ROS1 treatment. Of these, 34.8% people also experienced baseline brain metastases. The ORR was 67.1%, PFS median was 15.7 months, and 1-year OS rate was 81%. For 24 patients at the baseline with measurable brain metastases, the intracerebral ORR was 79.2%, and intracerebral PFS was 12 months (Drilon et al., 2020).

6.3 Lorlatinib

Lorlatinib is a third-generation ROS1 inhibitor designed to overcome resistance mutations that may develop during treatment with earlier-generation inhibitors. It has a more intricate structure compared to crizotinib, with multiple fused rings and functional groups, increasing the permeability of the blood–brain barrier by reducing P-glucose-1-mediated exudation. Lorlatinib exhibits activity against ROS1 as well as ALK. In a Phase I/II study, 61 people with ROS1-positive NSCLC were included, including 21 patients treated with primary TKIs and 40 patients previously treated with crizotinib. The ORR of the primary TKI patients was 62%, their median PFS was 21 months, their intracerebral ORR was 64%, and intracerebral PFS was not achieved. The ORR, median PFS, and intracerebral ORR of the patients treated with crizotinib were 35%, 8.5 months, and 50%, respectively. The most common adverse events included hypocholesterolemia (65%), hypoglycemia (42%), peripheral edema (39%), surrounding neuropathy (35%), cognitive changes (26%), weight gain (16%), and mood disorders (16%). The incidences of grade 3 and 4 adverse reactions were 43% and 6%, respectively (Shaw et al., 2019b). Monitoring the plasma concentration of lorlatinib may help control adverse events without altering the effectiveness of this antitumor therapy (Chen et al., 2021). When resistance mutations, such as ROS1 K1991E or ROS1 S1986F , appear after treatment with crizotinib, lorlatinib may have a stronger effect; however, it has a minor effect on the resistance mutation type ROS1 G2032R .

6.4 Ceritinib

Ceritinib is an ALK inhibitor that exhibits antitumor activity and intracerebral effects in those with ALK-positive NSCLC (Shaw et al., 2017). The molecular structure of ceritinib includes various aromatic rings and functional groups. In vitro experiments showed that ceritinib has potential anti-ROS1 rearrangement activity. In a Phase II study involving 32 patients with ROS1-positive NSCLC, the ORR for ceritinib treatment was 62%, and the median PFS was 9.3 months. In the subgroup (n = 30) that was not treated with crizotinib, the median PFS was 19.3 months, and its effectiveness was comparable to that of other TKIs. The ORR in the brain metastasis subgroup (n = 8) was 63%. Its tolerance was similar to that of other TKIs, with an incidence of 37% of adverse events of grade 3 or above (Drilon et al., 2016).

6.5 Cabozantinib

Cabozantinib is a small-molecule TKI and consists of a pyridine ring with a fluorine atom and a 3-(morpholin-4-yl) propoxy group attached to it, as well as a 3-aminopyridine-2-carboxamide group and a 4-(6-(propan-2-yl) pyridin-3-yl) benzoic acid group (Maroto et al., 2022). It targets ROS1, MET, VEGFR-2, RET, and AXL and has a strong ability to penetrate the blood–brain barrier. The results of preclinical studies and case reports have indicated that cabozantinib is effective for treating patients with resistance to other TKIs (crizotinib, entrectinib, and ceritinib) and resistance mutations (such as D2033N or G2032R) (Sun et al., 2019). Therefore, cabozantinib is clinically used as a treatment option after the development of resistance to other TKIs.

6.6 Brigatinib

Brigatinib is a kinase inhibitor with a complex structure. It contains pyrimidine, pyridine, and aniline moieties, among others, arranged in a way that allows it to inhibit the activity of certain tyrosine kinases, it is a multitarget inhibitor of ROS1 and ALK and has antitumor activity against EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Brigatinib exhibits antitumor activity against several drug-resistant ROS1 mutations. In one study, researchers assessed the efficacy and tolerance of brigatinib in eight patients with ROS1-positive NSCLC, one of whom did not receive TKI treatment, and seven of whom developed disease progression after crizotinib treatment (Dudnik et al., 2020). The ORRs for the total population and the crizotinib-treated subgroups were 37% and 29%, respectively. No Grade 3 or 4 adverse events were observed. In one case report, the disease progressed after prior treatment with several ROS1-TKIs, and brigatinib therapy remained effective (Hegde et al., 2019). In vitro experiments showed that Bugatti has strong anti-tumor activity against NSCLC carrying the L2026M mutation but is ineffective against the G2032R mutation (Camidge et al., 2018).

6.7 Repotrectinib

Repotrectinib (TPX-0005) is also a multitarget TKI that can target ROS1, TRK, and ALK and effectively cross the blood–brain barrier. It contains various functional groups, including cyclic structures and heteroatoms like nitrogen and oxygen. The specific arrangement of atoms in Repotrectinib allows it to interact with the ATP-binding sites of these kinases, inhibiting their activity and disrupting the signaling pathways that contribute to cancer cell growth. In preclinical studies, repotrectinib showed strong antitumor activity in NSCLC models with ROS1-positive brain metastases, prior ROS1-TKI treatment, and ROS1 G2032R mutations (Yun et al., 2020). A Phase I/II clinical trial (NCT03093116) to evaluate the safety and efficacy of repotrectinib in ROS1-positive NSCLC is currently underway.

6.8 Taletrectinib

Taletrectinib (DS-6051B) is an inhibitor targeting ROS1 and NTRK and shows antitumor activity against crizotinib-resistant NSCLC, including in patients carrying the G2032R mutation. In in vitro experiments, taletrectinib showed strong activity against resistance mutations, such as G2032R, L1951R, S1986F, and L2026M. Two Phase I clinical trials conducted in the United States and Japan evaluated the effectiveness of taletrectinib in patients with ROS1-positive NSCLC. The former included 46 patients with an ORR of 33% in patients with crizotinib resistance; the latter included 15 patients with ORRs of 58.3% and 66.7% in all patients and in patients with no prior crizotinib treatment, respectively (Papadopoulos et al., 2020).

6.9 Ensartinib

Ensartinib is an ALK-TKI that demonstrated 10-times higher anti-ALK activity than crizotinib in in vitro experiments. A Phase II trial of ROS1-positive NSCLC (NCT03608007) showed a certain therapeutic effectiveness, with an ORR of 27%, and intracerebral disease control was achieved in three out of four patients with brain metastases (Ai et al., 2021).

6.10 Other treatments

Chemotherapy remains the recommended second-line treatment after the failure of crizotinib treatment. The combination of antivascular therapy with ROS1-TKIs is another potentially effective treatment strategy. In in vitro experiments, the combined use of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) blockers and ROS1-TKI increased antitumor activity (Watanabe et al., 2021). In a clinical trial involving 14 patients, those with NSCLC that was ALK-positive, ROS1-positive, or had MET expansion showed an ORR was 58.3% with good tolerance; however, 3 patients discontinued treatment due to hepatotoxicity or hemorrhage (Saito et al., 2019).

The effectiveness of immunotherapy in ROS1-positive NSCLC has not yet been fully elucidated. In in vitro experiments, ROS1 was found to regulate the expression of programmed death protein ligand-1 (PD-L1) by activating the MEK–ERK and ROS1–SHP2 signaling pathways. Most ROS1-positive tumors do not express PD-L1 and have a low tumor mutation burden (TMB) (Choudhury et al., 2021). The results of small-sample studies have shown that the ORR of people with ROS1-positive NSCLC receiving mono-immunotherapy was 13%–17% (Mazieres et al., 2019), and the ORR of immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy was 83% (Guisier et al., 2020). Choudhury et al. (Choudhury et al., 2021) found no noticeable differences in the expression levels of PD-L1 between patients who received effective and ineffective immunotherapies. In patients with TKI resistance, combined immunotherapy has a high clinical application value, but potential toxic reactions to sequential immunotherapy with TKIs must be monitored.

7 Resistance mechanisms of ROS1 inhibitors

7.1 Resistance mechanisms of crizotinib

7.1.1 Structural domain mutations

ROS1 kinase structural domain mutation is the most common resistance mechanism to crizotinib, accounting for approximately 40%–55% of the total. G2032R is the most common type of mutation, occurring in the solvent area of the ATP binding site, accounting for approximately 33%–41% of cases (Awad et al., 2013). In in vitro studies, the ROS1 G2032R mutation increased the expression of TWIST1, promoting epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), cell migration, and resistance to ROS1-TKIs by modifying the combination of location points and spatial blockages (Gou et al., 2018). Currently, repotrectinib, topotrectinib, and cabozantinib have shown improved anti-ROS1G2032R activity (Gou et al., 2018).

Other common mutations include D2033N (2.4%–6%), S1986Y/F (2.4%–6%), L2026M (1%), L2155S (1%), L1951R (1%), and S1886 (1%) (Katayama et al., 2015) (Table 2). ROS1 D2033N induces the modification of ATP-binding pockets, resulting in the weakening of the ability of tumor cells to bind to ROS1-TKIs. In in vitro experiments, ROS1 D2033N led to resistance to crizotinib, entrectinib, and ceritinib, but remained sensitive to lorlatinib, repotrectinib, and cabozantinib. ROS1 S1986F results in resistance to crizotinib, entrectinib, and ceritinib by changing the position of a ring structure rich in glycine at the end of the C spiral (Facchinetti et al., 2016).

TABLE 2.

Common mutation types of crizotinib resistance and effective inhibitors.

| Type of ROS1 fusion | Mutation site | Mechanisms | Effective TKI |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD74-ROS1 | G2032R | Altered spatial structure of ROS1 domain interferes with drug binding and leads to resistance to ROS1 inhibitors | cabozantinib |

| repotrectinib | |||

| D2033N | Alteration in the electrostatic force on the outer surface of the ATP-binding site and a rearrangement of ATP-binding site | lorlatinib | |

| cabozantinib | |||

| repotrectinib | |||

| L2026M | Leucine to methionine substitution | ceritinib | |

| lorlatinib | |||

| cabozantinib | |||

| repotrectinib | |||

| SLC34A2-ROS1 | L2155S | Protein dysfunction | lorlatinib |

| cabozantinib | |||

| repotrectinib | |||

| EZR-ROS1 | S1986F/Y | Increased kinase activity | lorlatinib |

| cabozantinib | |||

| repotrectinib |

7.1.2 Activation of other signaling pathways

Crizotinib resistance may also be associated with the activation of other signaling pathways downstream of ROS1. The activation of these downstream signaling pathways can lead to the following: 1) stimulation of the signaling pathway that resists ROS1-TKIs and 2) the production of new mutations or expansions at the level of other oncogenes. For example, SHP2 activation of the MAPK/MEK/ERK pathway can lead to TKI resistance. In in vitro experiments, a combination of SHP2 inhibitors and ROS1-TKI increased the inhibition of tumor growth (Li et al., 2021). Additionally, mutations or proliferation of ALK (Li et al., 2021), BRAF (Ren et al., 2021), KRAS, and MET (Wang et al., 2021) can lead to resistance to ROS1-TKIs.

7.1.3 Phenotype transformation

In a related case report, small-cell cancer transformation may occur after the resistance to ROS1-TKIs (Yang et al., 2021). According to these findings, this phenotype transformation may be associated with the inactivation of the retinoblastoma 1 (RB1) and TP53 genes (Fares et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2020).

7.2 Resistance mechanisms of lorlatinib

The mechanisms underlying the resistance to TKIs other than crizotinib are not fully understood. Lin et al. analyzed 28 cases of post-lorlatinib progressive tumor tissue samples and found mutations in the kinase structural domain, especially G2032K and L2086F mutations (Lin et al., 2021). The results of in vitro experiments showed that the ROS1 G2032K mutation conferred resistance to crizotinib, entrectinib, and lorlatinib. For the ROS1 L2086F mutation, the related models showed that it was equally resistant to crizotinib, entrectinib, and lorlatinib, whereas cabozantinib may have a therapeutic effect (Mazieres et al., 2015). Other resistance mechanisms to lorlatinib include MET expansion (4%), KRAS G12C mutation (4%), KRAS expansion (4), and NRAS extension (4%) (Papadopoulos et al., 2020).

8 Conclusion

Targeted therapy is the foundation for the treatment of people with unresectable NSCLC with ROS1 rearrangements. Crizotinib and entrectinib are currently recommended as the standard first-line therapeutic drugs. In future drug development, antitumor activity and brain permeation are important indicators for measuring the effectiveness of ROS1-TKIs. The new TKIs, entrectinib and lorlatinib, have a higher rate of blood–brain barrier permeation and are expected to provide increased control of brain metastases. For the primary mutants of ROS1 G2302R , repotrectinib and taletrectinib also showed high clinical efficacy.

In cases of disease progression after crizotinib treatment, the choice of secondary treatment should depend on the type of progression and specific resistance mechanisms. In the case of oligometastasis, topical treatment, represented by radiation or surgery, should be quickly administered, especially in patients with brain metastases. When multiorgan progression occurs, a whole-body treatment scheme based on chemotherapy containing platinum is still the current standard treatment. Targeted drugs may be more suitable treatment options for patients who have undergone genetic testing to clearly identify resistance mechanisms.

Author contributions

XY carried out the primary literature search, drafted, and revised the manuscript. JL and YL contributed to drafting and revising of the manuscript. JJ and JL helped modify the manuscript. ZT and YL carried out the literature analysis and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Ai X., Wang Q., Cheng Y., Liu X., Cao L., Chen J., et al. (2021). Safety but limited efficacy of ensartinib in ROS1-positive NSCLC: a single-arm, multicenter phase 2 study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 16 (11), 1959–1963. 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad M. M., Engelman J. A., Shaw A. T. (2013). Acquired resistance to crizotinib from a mutation in CD74-ROS1. N. Engl. J. Med. 369 (12), 1173. 10.1056/NEJMc1309091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balduzzi P. C., Notter M. F., Morgan H. R., Shibuya M. (1981). Some biological properties of two new avian sarcoma viruses. J. Virol. 40 (1), 268–275. 10.1128/JVI.40.1.268-275.1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergethon K., Shaw A. T., Ou S. H., Katayama R., Lovly C. M., McDonald N. T., et al. (2012). ROS1 rearrangements define a unique molecular class of lung cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 30 (8), 863–870. 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W., Li X., Su C., Fan L., Zheng L., Fei K., et al. (2013). ROS1 fusions in Chinese patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 24 (7), 1822–1827. 10.1093/annonc/mdt071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camidge D. R., Kim D. W., Tiseo M., Langer C. J., Ahn M. J., Shaw A. T., et al. (2018). Exploratory analysis of brigatinib activity in patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small-cell lung cancer and brain metastases in two clinical trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 36 (26), 2693–2701. 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.5841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capizzi E., Dall'Olio F. G., Gruppioni E., Sperandi F., Altimari A., Giunchi F., et al. (2019). Clinical significance of ROS1 5' deletions in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 135, 88–91. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Ruiz-Garcia A., James L. P., Peltz G., Thurm H., Clancy J., et al. (2021). Lorlatinib exposure-response analyses for safety and efficacy in a phase I/II trial to support benefit-risk assessment in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 110 (5), 1273–1281. 10.1002/cpt.2228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung C. C., Smith A. C., Albadine R., Bigras G., Bojarski A., Couture C., et al. (2021). Canadian ROS proto-oncogene 1 study (CROS) for multi-institutional implementation of ROS1 testing in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 160, 127–135. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury N. J., Schneider J. L., Patil T., Zhu V. W., Goldman D. A., Yang S. R., et al. (2021). Response to immune checkpoint inhibition as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy in metastatic ROS1-rearranged lung cancers. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2 (7), 100187. 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2021.100187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clave S., Rodon N., Pijuan L., Díaz O., Lorenzo M., Rocha P., et al. (2019). Next-generation sequencing for ALK and ROS1 rearrangement detection in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: implications of FISH-positive patterns. Clin. Lung Cancer 20 (4), e421–e429. 10.1016/j.cllc.2019.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M., Han Y., Li P., Zhang J., Ou Q., Tong X., et al. (2020). Molecular and clinicopathological characteristics of ROS1-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancers identified by next-generation sequencing. Mol. Oncol. 14 (11), 2787–2795. 10.1002/1878-0261.12789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagogo-Jack I., Rooney M., Nagy R. J., Lin J. J., Chin E., Ferris L. A., et al. (2019). Molecular analysis of plasma from patients with ROS1-positive NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 14 (5), 816–824. 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drilon A., Jenkins C., Iyer S., Schoenfeld A., Keddy C., Davare M. A. (2021). ROS1-dependent cancers - biology, diagnostics and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18 (1), 35–55. 10.1038/s41571-020-0408-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drilon A., Siena S., Dziadziuszko R., Barlesi F., Krebs M. G., Shaw A. T., et al. (2020). Entrectinib in ROS1 fusion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: integrated analysis of three phase 1-2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 21 (2), 261–270. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30690-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drilon A., Siena S., Ou S. I., Patel M., Ahn M. J., Lee J., et al. (2017). Safety and antitumor activity of the multitargeted pan-TRK, ROS1, and ALK inhibitor entrectinib: combined results from two phase I trials (ALKA-372-001 and STARTRK-1). Cancer Discov. 7 (4), 400–409. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drilon A., Somwar R., Wagner J. P., Vellore N. A., Eide C. A., Zabriskie M. S., et al. (2016). A novel crizotinib-resistant solvent-front mutation responsive to cabozantinib therapy in a patient with ROS1-rearranged lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 22 (10), 2351–2358. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudnik E., Agbarya A., Grinberg R., Cyjon A., Bar J., Moskovitz M., et al. (2020). Clinical activity of brigatinib in ROS1-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 22 (12), 2303–2311. 10.1007/s12094-020-02376-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziadziuszko R., Krebs M. G., De Braud F., Siena S., Drilon A., Doebele R. C., et al. (2021). Updated integrated analysis of the efficacy and safety of entrectinib in locally advanced or metastatic ROS1 fusion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 39 (11), 1253–1263. 10.1200/JCO.20.03025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facchinetti F., Loriot Y., Kuo M. S., Mahjoubi L., Lacroix L., Planchard D., et al. (2016). Crizotinib-resistant ROS1 mutations reveal a predictive kinase inhibitor sensitivity model for ROS1- and ALK-rearranged lung cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 22 (24), 5983–5991. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fares A. F., Lok B. H., Zhang T., Cabanero M., Lau S. C. M., Stockley T., et al. (2020). ALK-rearranged lung adenocarcinoma transformation into high-grade large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: clinical and molecular description of two cases. Lung Cancer 146, 350–354. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielder T., Butler J., Tierney G., Holmes M., Lam K. Y., Satgunaseelan L., et al. (2022). ROS1 rearrangements in lung adenocarcinomas are defined by diffuse strong immunohistochemical expression of ROS1. Pathology 54 (4), 399–403. 10.1016/j.pathol.2021.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu S., Liang Y., Lin Y. B., Wang F., Huang M. Y., Zhang Z. C., et al. (2015). The frequency and clinical implication of ROS1 and RET rearrangements in resected stage IIIA-N2 non-small cell lung cancer patients. PLoS One 10 (4), e0124354. 10.1371/journal.pone.0124354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginestet F., Lambros L., Le Flahec G., Marcorelles P., Uguen A. (2018). Evaluation of a dual ALK/ROS1 fluorescent in situ hybridization test in non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer 19 (5), e647–e653. 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou W., Zhou X., Liu Z., Wang L., Shen J., Xu X., et al. (2018). CD74-ROS1 G2032R mutation transcriptionally up-regulates Twist1 in non-small cell lung cancer cells leading to increased migration, invasion, and resistance to crizotinib. Cancer Lett. 422, 19–28. 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guisier F., Dubos-Arvis C., Vinas F., Doubre H., Ricordel C., Ropert S., et al. (2020). Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC with BRAF, HER2, or MET mutations or RET translocation: GFPC 01-2018. J. Thorac. Oncol. 15 (4), 628–636. 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.12.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde A., Hong D. S., Behrang A., Ali S. M., Juckett L., Meric-Bernstam F., et al. (2019). Activity of brigatinib in crizotinib and ceritinib-resistant ROS1- rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. JCO Precis. Oncol. 3, 1–6. 10.1200/po.18.00267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofman V., Rouquette I., Long-Mira E., Piton N., Chamorey E., Heeke S., et al. (2019). Multicenter evaluation of a novel ROS1 immunohistochemistry assay (SP384) for detection of ROS1 rearrangements in a large cohort of lung adenocarcinoma patients. J. Thorac. Oncol. 14 (7), 1204–1212. 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Jiang S., Shi Y. (2020). Tyrosine kinase inhibitors for solid tumors in the past 20 years (2001-2020). J. Hematol. Oncol. 13 (1), 143. 10.1186/s13045-020-00977-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R. S. P., Gottberg-Williams A., Vang P., Yang S., Britt N., Kaur J., et al. (2021b). Correlating ROS1 protein expression with ROS1 fusions, amplifications, and mutations. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2 (2), 100100. 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2020.100100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R. S. P., Haberberger J., Sokol E., Schrock A. B., Danziger N., Madison R., et al. (2021a). Clinicopathologic, genomic and protein expression characterization of 356 ROS1 fusion driven solid tumors cases. Int. J. Cancer 148 (7), 1778–1788. 10.1002/ijc.33447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama R., Kobayashi Y., Friboulet L., Lockerman E. L., Koike S., Shaw A. T., et al. (2015). Cabozantinib overcomes crizotinib resistance in ROS1 fusion-positive cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 21 (1), 166–174. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. W., Do S. I., Na K. (2021). External validation of ALK and ROS1 fusions detected using an oncomine comprehensive assay. Anticancer Res. 41 (9), 4609–4617. 10.21873/anticanres.15274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambros L., Guibourg B., Uguen A. (2018). ROS1-rearranged non-small cell lung cancers with concomitant oncogenic driver alterations: about some rare therapeutic dilemmas. Clin. Lung Cancer 19 (1), e73–e74. 10.1016/j.cllc.2017.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Chen Z., Huang M., Zhang D., Hu M., Jiao F., et al. (2022). Detection of ROS1 gene fusions using next-generation sequencing for patients with malignancy in China. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 1035033. 10.3389/fcell.2022.1035033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Lin Y., Chi X., Xu M., Wang H. (2021). Appearance of an ALK mutation conferring resistance to crizotinib in non-small cell lung cancer harboring oncogenic ROS1 fusion. Lung Cancer 153, 174–175. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Shen L., Ding D., Huang J., Zhang J., Chen Z., et al. (2018). Efficacy of crizotinib among different types of ROS1 fusion partners in patients with ROS1-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 13 (7), 987–995. 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. J., Choudhury N. J., Yoda S., Zhu V. W., Johnson T. W., Sakhtemani R., et al. (2021). Spectrum of mechanisms of resistance to crizotinib and lorlatinib in ROS1 fusion-positive lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 27 (10), 2899–2909. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. J., Langenbucher A., Gupta P., Yoda S., Fetter I. J., Rooney M., et al. (2020). Small cell transformation of ROS1 fusion-positive lung cancer resistant to ROS1 inhibition. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 4, 21. 10.1038/s41698-020-0127-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. J., Ritterhouse L. L., Ali S. M., Bailey M., Schrock A. B., Gainor J. F., et al. (2017). ROS1 fusions rarely overlap with other oncogenic drivers in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 12 (5), 872–877. 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeman N. I., Cagle P. T., Aisner D. L., Arcila M. E., Beasley M. B., Bernicker E. H., et al. (2018). Updated molecular testing guideline for the selection of lung cancer patients for treatment with targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors: guideline from the college of American pathologists, the international association for the study of lung cancer, and the association for molecular pathology. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 142 (3), 321–346. 10.5858/arpa.2017-0388-CP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarem M., Ezeife D. A., Smith A. C., Li J. J. N., Law J. H., Tsao M. S., et al. (2021). Reflex ROS1 IHC screening with FISH confirmation for advanced non-small cell lung cancer-A cost-efficient strategy in a public healthcare system. Curr. Oncol. 28 (5), 3268–3279. 10.3390/curroncol28050284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroto P., Porta C., Capdevila J., Apolo A. B., Viteri S., Rodriguez-Antona C., et al. (2022). Cabozantinib for the treatment of solid tumors: a systematic review. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 14, 17588359221107112. 10.1177/17588359221107112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazieres J., Drilon A., Lusque A., Mhanna L., Cortot A. B., Mezquita L., et al. (2019). Immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with advanced lung cancer and oncogenic driver alterations: results from the IMMUNOTARGET registry. Ann. Oncol. 30 (8), 1321–1328. 10.1093/annonc/mdz167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazieres J., Zalcman G., Crino L., Biondani P., Barlesi F., Filleron T., et al. (2015). Crizotinib therapy for advanced lung adenocarcinoma and a ROS1 rearrangement: results from the EUROS1 cohort. J. Clin. Oncol. 33 (9), 992–999. 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels S., Massuti B., Schildhaus H. U., Franklin J., Sebastian M., Felip E., et al. (2019). Safety and efficacy of crizotinib in patients with advanced or metastatic ROS1-rearranged lung cancer (EUCROSS): a European phase II clinical trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. 14 (7), 1266–1276. 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosele F., Remon J., Mateo J., Westphalen C. B., Barlesi F., Lolkema M. P., et al. (2020). Recommendations for the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for patients with metastatic cancers: a report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann. Oncol. 31 (11), 1491–1505. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan L., Louie E., Tsujimoto Y., Balduzzi P. C., Huebner K., Croce C. M. (1986). The human c-ros gene (ROS) is located at chromosome region 6q16----6q22. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83 (17), 6568–6572. 10.1073/pnas.83.17.6568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos K. P., Borazanci E., Shaw A. T., Katayama R., Shimizu Y., Zhu V. W., et al. (2020). U.S. Phase I first-in-human study of taletrectinib (DS-6051b/AB-106), a ROS1/TRK inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 26 (18), 4785–4794. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park E., Choi Y. L., Ahn M. J., Han J. (2019). Histopathologic characteristics of advanced-stage ROS1-rearranged non-small cell lung cancers. Pathol. Res. Pract. 215 (7), 152441. 10.1016/j.prp.2019.152441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters S., Shaw A. T., Besse B., Felip E., Solomon B. J., Soo R. A., et al. (2020). Impact of lorlatinib on patient-reported outcomes in patients with advanced ALK-positive or ROS1-positive non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 144, 10–19. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren S., Huang S., Ye X., Feng L., Lu Y., Zhou C., et al. (2021). Crizotinib resistance conferred by BRAF V600E mutation in non-small cell lung cancer harboring an oncogenic ROS1 fusion. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 27, 100377. 10.1016/j.ctarc.2021.100377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rihawi K., Cinausero M., Fiorentino M., Salvagni S., Brocchi S., Ardizzoni A. (2018). Co-Alteration of c-met and ROS1 in advanced NSCLC: ROS1 wins. J. Thorac. Oncol. 13 (3), e41–e43. 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikova K., Guo A., Zeng Q., Possemato A., Yu J., Haack H., et al. (2007). Global survey of phosphotyrosine signaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell 131 (6), 1190–1203. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfo C., Ruiz R., Giovannetti E., Gil-Bazo I., Russo A., Passiglia F., et al. (2015). Entrectinib: a potent new TRK, ROS1, and ALK inhibitor. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 24 (11), 1493–1500. 10.1517/13543784.2015.1096344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskoski R., Jr. (2017). ROS1 protein-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment of ROS1 fusion protein-driven non-small cell lung cancers. Pharmacol. Res. 121, 202–212. 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito H., Fukuhara T., Furuya N., Watanabe K., Sugawara S., Iwasawa S., et al. (2019). Erlotinib plus bevacizumab versus erlotinib alone in patients with EGFR-positive advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (NEJ026): interim analysis of an open-label, randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 20 (5), 625–635. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30035-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A. T., Bernardo R. J., Berry G. J., Kudelko K., Wakelee H. A. (2021). Two cases of pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy associated with ROS1-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer 22 (2), e153–e156. 10.1016/j.cllc.2020.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan L., Lian F., Guo L., Qiu T., Ling Y., Ying J., et al. (2015). Detection of ROS1 gene rearrangement in lung adenocarcinoma: comparison of IHC, FISH and real-time RT-PCR. PLoS One 10 (3), e0120422. 10.1371/journal.pone.0120422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw A. T., Kim T. M., Crino L., Gridelli C., Kiura K., Liu G., et al. (2017). Ceritinib versus chemotherapy in patients with ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer previously given chemotherapy and crizotinib (ASCEND-5): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 18 (7), 874–886. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30339-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw A. T., Riely G. J., Bang Y. J., Kim D. W., Camidge D. R., Solomon B. J., et al. (2019a). Crizotinib in ROS1-rearranged advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): updated results, including overall survival, from PROFILE 1001. Ann. Oncol. 30 (7), 1121–1126. 10.1093/annonc/mdz131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw A. T., Solomon B. J., Chiari R., Riely G. J., Besse B., Soo R. A., et al. (2019b). Lorlatinib in advanced ROS1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 20 (12), 1691–1701. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30655-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. L., Miller K. D., Fuchs H. E., Jemal A. (2022). Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 72 (1), 7–33. 10.3322/caac.21708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z., Zheng Y., Wang X., Su H., Zhang Y., Song Y. (2017). ALK and ROS1 rearrangements, coexistence and treatment in epidermal growth factor receptor-wild type lung adenocarcinoma: a multicenter study of 732 cases. J. Thorac. Dis. 9 (10), 3919–3926. 10.21037/jtd.2017.09.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T. Y., Niu X., Chakraborty A., Neal J. W., Wakelee H. A. (2019). Lengthy progression-free survival and intracranial activity of cabozantinib in patients with crizotinib and ceritinib-resistant ROS1-positive non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 14 (2), e21–e24. 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.08.2030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z., Zhang J., Lu X., Wang W., Chen H., Robinson M. K., et al. (2018). Coexistent genetic alterations involving ALK, RET, ROS1 or MET in 15 cases of lung adenocarcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 31 (2), 307–312. 10.1038/modpathol.2017.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uguen A., Schick U., Quere G. (2017). A rare case of ROS1 and ALK double rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 12 (6), e71–e72. 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Cheng G., Zhang G., Song Z. (2020). Evaluation of a new diagnostic immunohistochemistry approach for ROS1 rearrangement in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 146, 224–229. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Chen Z., Han X., Li J., Guo H., Shi J. (2021). Acquired MET D1228N mutations mediate crizotinib resistance in lung adenocarcinoma with ROS1 fusion: a case report. Oncologist 26 (3), 178–181. 10.1002/onco.13545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H., Ichihara E., Kayatani H., Makimoto G., Ninomiya K., Nishii K., et al. (2021). VEGFR2 blockade augments the effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors by inhibiting angiogenesis and oncogenic signaling in oncogene-driven non-small-cell lung cancers. Cancer Sci. 112 (5), 1853–1864. 10.1111/cas.14801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesweg M., Eberhardt W. E. E., Reis H., Ting S., Savvidou N., Skiba C., et al. (2017). High prevalence of concomitant oncogene mutations in prospectively identified patients with ROS1-positive metastatic lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 12 (1), 54–64. 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.08.137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodford R., Lu M., Beydoun N., Cooper W., Liu Q., Lynch J., et al. (2021). Disseminated intravascular coagulation complicating diagnosis of ROS1-mutant non-small cell lung cancer: a case report and literature review. Thorac. Cancer 12 (17), 2400–2403. 10.1111/1759-7714.14071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. L., Yang J. C., Kim D. W., Lu S., Zhou J., Seto T., et al. (2018). Phase II study of crizotinib in east asian patients with ROS1-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 36 (14), 1405–1411. 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.5587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Zhou P., Yu M., Zhang Y. (2021). Case report: high-level MET amplification as a resistance mechanism of ROS1-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in ROS1-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. Front. Oncol. 11, 645224. 10.3389/fonc.2021.645224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun M. R., Kim D. H., Kim S. Y., Joo H. S., Lee Y. W., Choi H. M., et al. (2020). Repotrectinib exhibits potent antitumor activity in treatment-naive and solvent-front-mutant ROS1-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 26 (13), 3287–3295. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L., Li Y., Xiao L., Xiong Y., Liu L., Jiang W., et al. (2018). Crizotinib presented with promising efficacy but for concomitant mutation in next-generation sequencing-identified ROS1-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 11, 6937–6945. 10.2147/OTT.S176273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Wu C., Ding W., Zhang Z., Qiu X., Mu D., et al. (2019). Prevalence of ROS1 fusion in Chinese patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac. Cancer 10 (1), 47–53. 10.1111/1759-7714.12899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q., Zhan P., Zhang X., Lv T., Song Y. (2015). Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with ROS1 fusion gene in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 4 (3), 300–309. 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2015.05.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu V. W., Zhao J. J., Gao Y., Syn N. L., Zhang S. S., Ou S. H. I., et al. (2021). Thromboembolism in ALK+ and ROS1+ NSCLC patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung Cancer 157, 147–155. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y. C., Xu C. W., Ye X. Q., Yin M. X., Zhang J. X., Du K. Q., et al. (2016). Lung cancer with concurrent EGFR mutation and ROS1 rearrangement: a case report and review of the literature. Onco Targets Ther. 9, 4301–4305. 10.2147/OTT.S109415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zito Marino F., Rossi G., Cozzolino I., Montella M., Micheli M., Bogina G., et al. (2020). Multiplex fluorescence in situ hybridisation to detect anaplastic lymphoma kinase and ROS proto-oncogene 1 receptor tyrosine kinase rearrangements in lung cancer cytological samples. J. Clin. Pathol. 73 (2), 96–101. 10.1136/jclinpath-2019-206152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]