Abstract

ermC mRNA decay was examined in a mutant of Bacillus subtilis that has a deleted pnpA gene (coding for polynucleotide phosphorylase). 5′-proximal RNA fragments less than 400 nucleotides in length were abundant in the pnpA strain but barely detectable in the wild type. On the other hand, the patterns of 3′-proximal RNA fragments were similar in the wild-type and pnpA strains. Northern blot analysis with different probes showed that the 5′ end of the decay intermediates was the native ermC 5′ end. For one prominent ermC RNA fragment, in particular, it was shown that formation of its 3′ end was directly related to the presence of a stalled ribosome. 5′-proximal decay intermediates were also detected for transcripts encoded by the yybF gene. These results suggest that PNPase activity, which may be less sensitive to structures or sequences that block exonucleolytic decay, is required for efficient decay of specific mRNA fragments. However, it was shown that even PNPase activity could be blocked in vivo at a particular RNA structure.

The ermC gene, carried on plasmid pE194 in Bacillus subtilis, encodes an rRNA methyltransferase (methylase) that confers resistance to erythromycin (EM) (28). We have studied the induced stabilization of ermC mRNA in B. subtilis, which is the result of stalling of an EM-bound ribosome near the 5′ end of the ermC message (2, 3). The fact that a ribosome stalled near the 5′ end of ermC leader RNA protects diverse mRNA sequences from decay (10) suggested that the decay-initiating nuclease must access the message from the 5′ end and then loop or track to an internal cleavage site. Cleavage at an internal site initiates decay by generating (i) an upstream RNA fragment with an unprotected 3′ end that is degraded by a 3′-to-5′ exonuclease and (ii) a downstream RNA fragment with a free 5′ end, which is accessible to the decay-initiating nuclease, leading to another round of internal cleavage and degradation (1). It has been proposed for Escherichia coli mRNA that decay from the 3′ end formed by rho-independent termination is blocked by the 3′-terminal stem-loop structure (4), perhaps in conjunction with the binding of an exonuclease-impeding factor (8).

Intermediates in ermC mRNA decay in B. subtilis have been difficult to characterize by Northern blot analysis. Apparently, once decay is initiated, the subsequent steps in the decay process are rapid. A detailed analysis of pur operon mRNA decay intermediates was possible because of the high degree of stability of these intermediates (15). Recently, decay intermediates of the Bacillus thuringiensis cry1Aa message, expressed in B. subtilis, was reported (30). Initiation of decay of cry1Aa mRNA was suggested to occur by endonuclease cleavages in specific 5′ and 3′ regions.

We have constructed a B. subtilis strain that contains a deletion in the pnpA gene, which codes for polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase) (32). In an earlier report, Deutscher and Reuven (9) used 3H-labeled poly(A) as a substrate to demonstrate that the phosphorolytic activity of PNPase is the major 3′-to-5′ exonucleolytic activity in B. subtilis—unlike the case in E. coli, where PNPase activity contributed only 10% of the exonucleolytic activity, and the major exonucleolytic activity was that of RNase II, a hydrolytic enzyme. We had expected, therefore, that disruption of the pnpA gene would have a major effect on the growth of B. subtilis, as disruption of 3′-to-5′ exonuclease activity in E. coli (by mutations in the RNase II- and PNPase-encoding genes) results in cell death (11). In fact, the B. subtilis pnpA deletion strain was not only viable but grew almost as well as the wild type at 37°C (32). Assays of bulk mRNA decay showed little difference between the wild-type and pnpA mutant strains. An exonuclease whose in vitro activity is enhanced in the presence of Mn2+ appeared to compensate for the lack of PNPase activity in this strain. The observable phenotypes of the pnpA strain were filamentous growth, cold sensitivity, and inability to grow in low levels of tetracycline.

Despite the modest effect of the absence of PNPase on bulk mRNA decay, we hypothesized that an examination of specific mRNAs in the pnpA mutant strain might allow observation of decay intermediates that are normally degraded rapidly. We show here that decay intermediates of ermC mRNA can be readily detected in the pnpA mutant strain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The wild-type B. subtilis host was BG1, which is trpC2 thr-5. The pnpA mutant host was BG119, a derivative of BG1 in which an internal portion of the pnpA gene was replaced with a kanamycin resistance cassette (32). The preparation of B. subtilis growth media and competent B. subtilis cultures was done as previously described (14). E. coli DH5α (16) was the host for plasmid constructions.

Plasmids.

The pnpA gene was reintroduced into the pnpA mutant strain by cloning into ermC-containing plasmid pYH30, which is a cointegrate of pGEM-3Zf(+) (Promega) and pBD144 joined at their unique PstI sites. Plasmid pBD144 is a pE194 derivative that carries the chloramphenicol resistance marker of pC194 on a ClaI fragment. An XbaI fragment from plasmid pNP7 (32), which carries the pnpA gene under control of the ermC promoter, was inserted into the unique XbaI site of pYH30.

The plasmid carrying wild-type ermC was pBD404, which is a cop-1 version of pBD144 that has a copy number of 200/cell (31). The ermC deletion derivatives used in the experiment shown in Fig. 6 were constructed by introducing—via oligonucleotide mutagenesis—an additional HpaI site into the ermC coding sequence, upstream of the HpaI site that is located 200 bp from the end of the ermC coding sequence (see Fig. 6). The internal HpaI fragment thus created was deleted, giving rise to various-size deletions of the ermC gene. The recipient plasmid for these deletions was pYH40 (19), which has a pE194 replicon (i.e., a copy number of 10 to 20/cell). Mutagenesis was done by the method of Kunkel et al. (21).

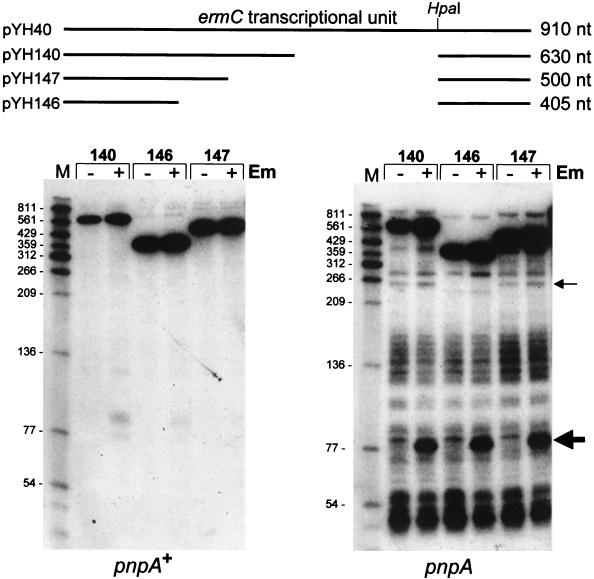

FIG. 6.

Northern blot analysis of decay intermediates from ermC deletion derivatives. Schematic diagrams of the deletion-containing ermC genes used in the analysis are presented at the top. Plasmid numbers in the pYH series are indicated, and they correspond to the numbers above the lanes at the bottom. RNAs were isolated from the wild type (pnpA+) and from the pnpA mutant strain (pnpA) in the absence (−) or presence (+) of EM. The thin arrow at the right shows the 250-nt band that was absent in the pYH146-carrying strain. The thick arrow points to the prominent 80-nt band that was observed only in the presence of EM. Molecular sizes (in nucleotides) are shown at the left.

The ermC plasmids with leader regions containing either no insert, a 9-nucleotide (nt) insert, or an 18-nt insert carried in pnpA mutant strains BE514, BE503, and BE504, respectively (see Fig. 7), were the same plasmids as those carried in wild-type strains BE177, BE207, and BE218, as described previously (18).

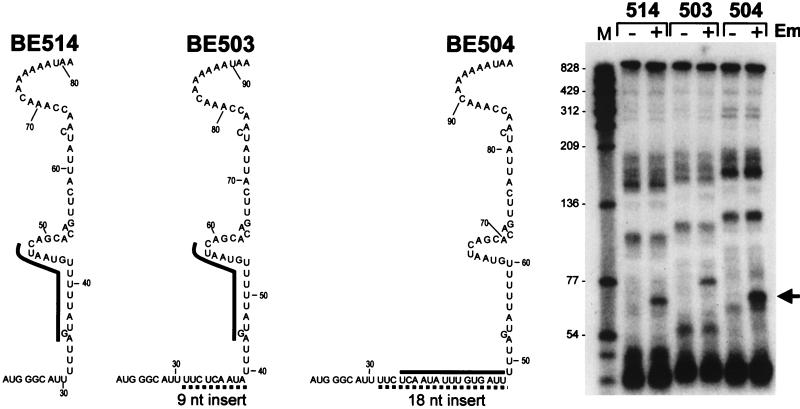

FIG. 7.

ermC leader region insertion mutations. Partial leader region sequences are shown. A sequence with no insert was carried in strain BE514. The sequences of insertions in the plasmids carried in strains BE503 and BE504 are indicated by dotted underlining. The thick line next to the sequence shows the predicted position of ribosome stalling in the presence of EM. At the right is the Northern blot analysis of ermC RNAs detected in these strains. The arrow at the right points to the prominent band induced in the presence of EM. Molecular sizes (in nucleotides) are shown on the left.

The SP82-ermC sequence, which was transcribed to give the RNA shown in Fig. 8, was constructed as follows. The HpaI-HindIII fragment of EG242, which contains the SP82 B. subtilis RNase III (Bs-RNase III) A cleavage site in an M13 vector (26), was replaced with an HpaI-HindIII fragment containing the 3′-terminal 200 bp of the ermC transcriptional unit. The fused SP82-ermC sequence was amplified by PCR, with the upstream primer providing an AflIII site such that the amplicon could be cloned between the NcoI and HindIII sites of pYH40 (19). The resulting plasmid, pYH188, was used to transform BG119.

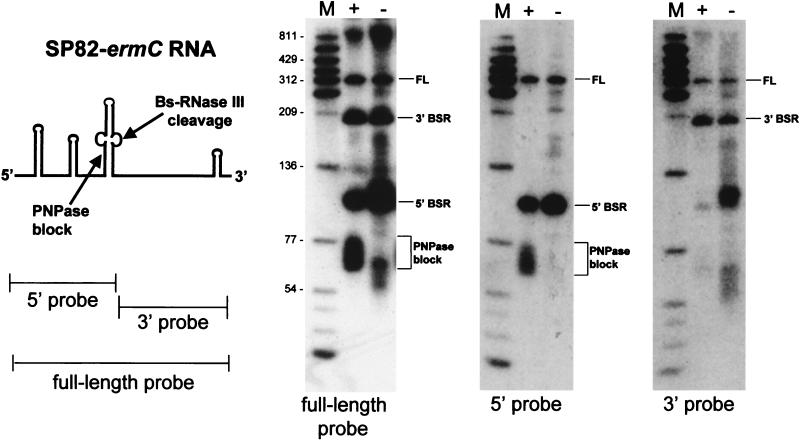

FIG. 8.

Analysis of SP82-ermC RNA. On the left, a schematic diagram of SP82-ermC RNA is shown, indicating the site of Bs-RNase III cleavage and the block to PNPase decay. Three probes were used to identify RNA species encoded by the SP82-ermC construct. The full-length (FL) probe detects four major species, one of which is the full-length RNA. The 5′ and 3′ fragments generated by Bs-RNase III cleavage are designated 5′ BSR and 3′ BSR, respectively. RNAs were isolated from the wild type (+) and the pnpA mutant strain (−). Molecular sizes (in nucleotides) are shown on the left.

The cloned B. subtilis genomic DNA containing yybF sequences was initially isolated on plasmid pTCC1, which was selected from a B. subtilis genomic library (kindly provided by A. D. Grossman) by virtue of its ability to complement the tetracycline sensitivity of BG119. The cloned B. subtilis fragment in pTCC1 was recloned as an SmaI-HindIII fragment into HpaI-HindIII-digested pYH25, which is a cointegrate of pGEM-3Zf(+) (Promega) and pBD144 joined at their unique PstI sites. The plasmid pYH25 derivative with the pTCC1 fragment inserted was named pTCC1-25. To reintroduce the pnpA gene into the pnpA strain, an XbaI fragment of pNP7 (32), which carries the pnpA gene under control of the ermC promoter, was inserted into the unique XbaI site of pTCC1-25 to give plasmid pNP15.

RNA analysis.

Strains were grown in enriched minimal medium until late logarithmic phase, and RNA was isolated as described previously (2). Enriched minimal medium contained 1× Spizizen salts with 0.5% glucose, 0.1% Casamino Acids, 0.001% yeast extract, 50-μg/ml (each) tryptophan and threonine, and 1 mM MgSO4. Northern blot analysis, using formaldehyde-agarose gels or 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gels, was done as described previously (33). Radioactivity in the bands on Northern blots was quantitated by using a PhosphorImager instrument (Molecular Dynamics). Half-lives were determined by linear regression analysis on semilogarithmic plots of percent RNA remaining versus time.

RESULTS

Detection of ermC mRNA decay products.

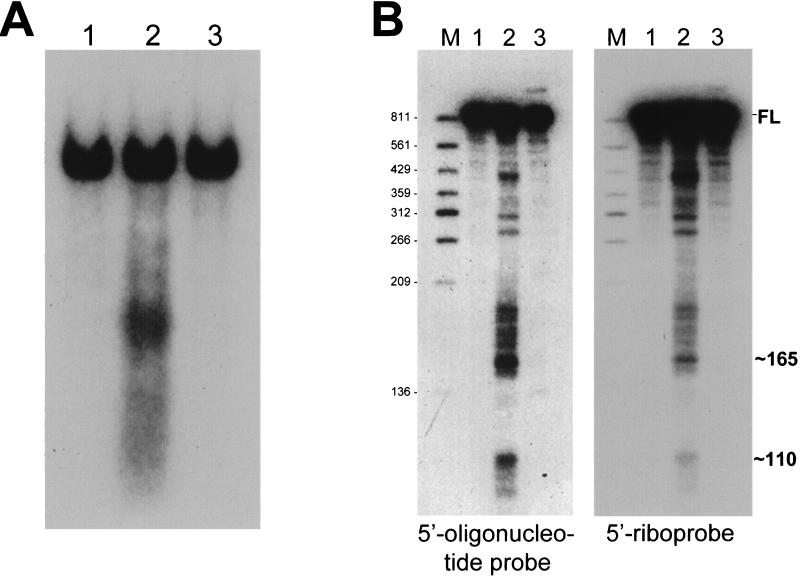

Since much of our work on mRNA decay in B. subtilis has been concerned with the 910-nt mRNA encoded by the ermC gene, ermC mRNA was examined in the pnpA background. Steady-state RNA was isolated from wild-type and pnpA strains carrying the ermC gene. The RNA was separated in a formaldehyde-agarose gel, and Northern blot analysis was performed by using a 5′-end-labeled oligonucleotide probe that was complementary to nt 10 to 27 of the ermC transcriptional unit (Fig. 1C). A difference in the pattern of ermC-specific RNA was observed in these strains (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 2). In the wild type, primarily the full-length ermC mRNA was detected, whereas in the pnpA strain, a smear of smaller RNAs was apparent. To demonstrate that these smaller RNAs arise due to the absence of PNPase, the ermC plasmid was constructed to contain also the pnpA ribosome binding site (RBS) and coding sequence transcribed from an ermC promoter. The pattern of ermC mRNA in the pnpA strain carrying this pnpA-containing plasmid was similar to that in the wild type (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 3). Thus, the detection of ermC RNA fragments in the pnpA mutant is enabled by the absence of PNPase activity.

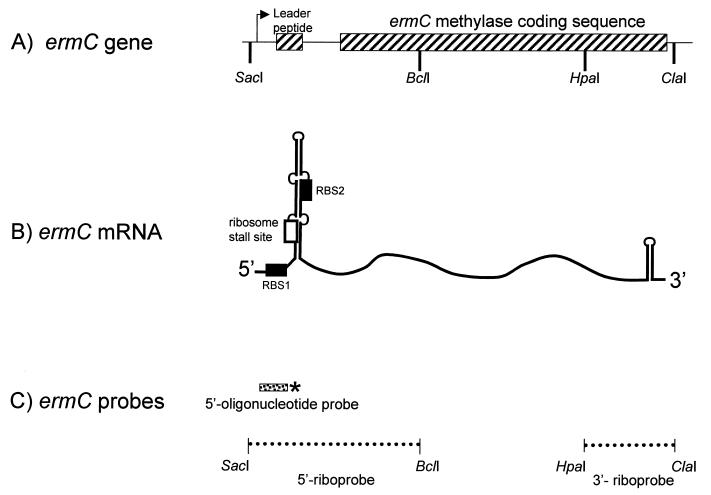

FIG. 1.

Diagrams of the ermC gene, ermC mRNA, and hybridization probes. (A) Hatched boxes represent the ermC leader peptide coding sequence and methylase coding sequence. The thin arrow indicates the location of the transcriptional start site. Relevant restriction sites are shown. (B) RBS1 and RBS2 are indicated by filled boxes. The site of ribosome stalling is indicated by the open box. Leader region RNA is shown schematically in the predicted stem-loop structure for the uninduced state (17, 23). The various portions of the ermC mRNA are not drawn to scale. (C) Probes used for Northern blot analysis. Transcription of the indicated DNA fragments generated the 5′ and 3′ riboprobes, which were uniformly labeled. The stippled bar represents the 5′ oligonucleotide probe, and the 5′-end label is indicated by the asterisk.

FIG. 2.

Northern blot analysis of steady-state ermC mRNA in wild-type and pnpA strains. (A) Formaldehyde-agarose gel, probed with the end-labeled 5′ oligonucleotide probe. RNA was isolated from the wild type (lane 1), the pnpA strain (lane 2), and the pnpA strain with the cloned pnpA gene (lane 3). (B) Denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gels probed with the end-labeled 5′ oligonucleotide probe or the 5′ riboprobe, as indicated. The migration of full-length (FL) ermC mRNA and bands of approximately 165 and 110 nt is indicated on the right. The marker lane (M) contained 5′-end-labeled DNA fragments of TaqI-digested plasmid pSE420 (5). The values to the left are molecular sizes in nucleotides.

To further explore the nature of the ermC RNA fragments, the same RNA preparations were separated in a denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel, electroblotted, and probed with both the 5′-end-labeled oligonucleotide and an ermC 5′ riboprobe that was complementary to the first 360 nt of the ermC transcriptional unit (Fig. 1C). The Northern blot analyses using these probes are shown in Fig. 2B. The ermC RNAs detected by the oligonucleotide probe appeared to be identical to those detected by the 5′ riboprobe. In experiments using shorter run times for the gels, a group of bands of approximately 45 nt was also detected (data not shown). Since the oligonucleotide probe was complementary to the 5′-terminal sequence, any RNAs detected by this probe must have as their 5′ end the native ermC transcriptional start site. A previous reverse transcriptase analysis of ermC mRNA did not detect any additional 5′ ends near the major transcriptional start site (3). Thus, the absence of PNPase allowed detection of RNA fragments whose 5′ end was at the ermC transcriptional start site and whose sizes ranged from about 40 nt to about 400 nt.

Accumulation of small ermC RNA products in the pnpA strain.

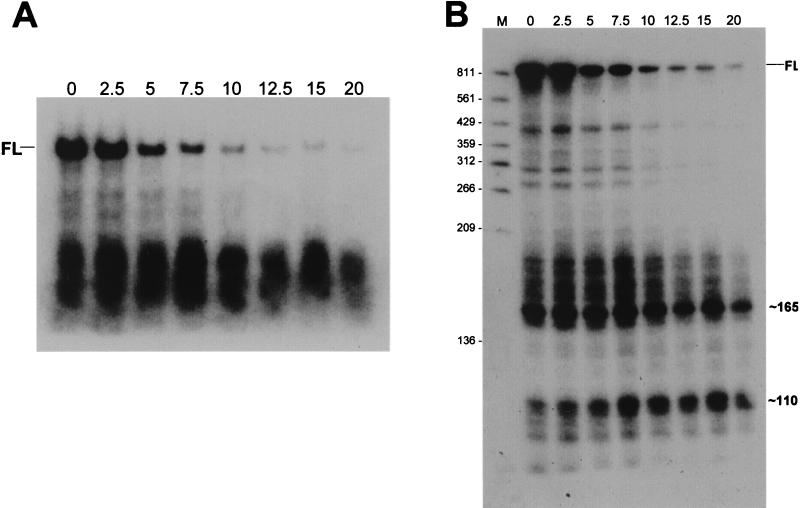

We hypothesized that the ermC RNA fragments that were readily detectable in the pnpA strain were decay intermediates that accumulated because of the absence of PNPase. The stability of these RNA fragments was measured by Northern blot analysis of RNA samples taken at various times after addition of rifampin and separated on a formaldehyde-agarose gel. The result (Fig. 3A) shows that small ermC RNA fragments are stabilized in the pnpA strain. While the half-life of the full-length ermC mRNA was 2.5 to 3 min, the smear of small RNAs was quite stable. This experiment was repeated by using a denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel and electroblotting to resolve the small RNAs (Fig. 3B). In the latter experiment, the measured half-life of full-length ermC mRNA was 3.5 min, while the prominent bands running at about 165 and 110 nt had a half-life of greater than 20 min. RNAs in the 300- to 400-nt range had half-lives of 5 to 6 min. Some of the accumulated small RNAs could come from continued breakdown of larger RNAs after rifampin addition. In fact, there appears to be a slight increase in the amount of small RNAs running above the 165-nt band and of the 110-nt band until 7.5 min after rifampin addition. However, the amount of 165- and 110-nt RNA fragments that is still present at 20 min after rifampin addition (i.e., 12.5 min after the noted accumulation at 7.5 min) suggests that these fragments are much more stable than full-length ermC mRNA, which is almost completely degraded in 12.5 min. We propose that the ability to detect small ermC RNAs in the pnpA strain is due to the stability of these fragments. Presumably, these RNAs are degraded rapidly in the wild type by PNPase and are thus not readily detectable.

FIG. 3.

Northern blot analysis of ermC mRNA decay after rifampin addition. Total RNA from the pnpA strain was separated on a formaldehyde-agarose gel (A) and on a denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel (B). The probe was the end-labeled 5′ oligonucleotide probe. Above each lane is the time (minutes) after rifampin addition. Full-length (FL) ermC mRNA, prominent small RNAs, and marker bands are indicated as in Fig. 2. Molecular sizes (in nucleotides) are shown on the left.

3′-specific ermC probe.

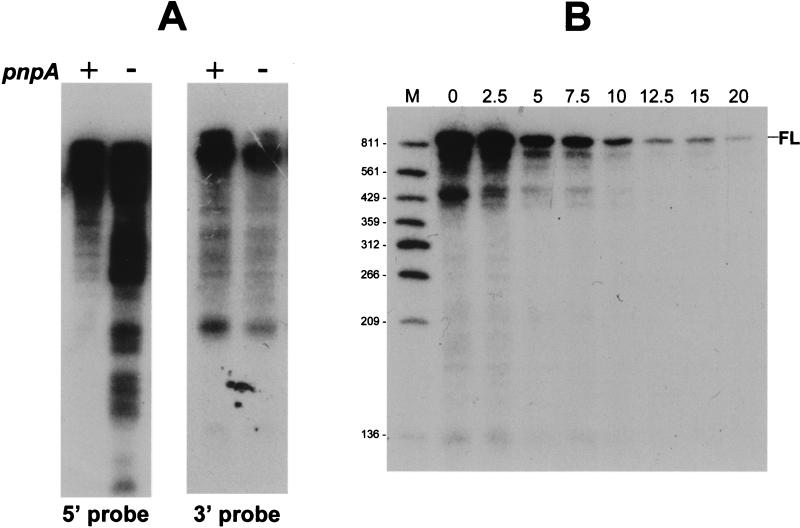

The patterns of RNA fragments in the wild-type and pnpA mutant strains were also analyzed with a riboprobe complementary to the 3′-terminal 200 nt of ermC mRNA, and the results were compared with the results obtained by using a 5′ riboprobe (Fig. 4A). Unlike those detected with the 5′ probe, the patterns of steady-state RNA detected by the 3′ probe were virtually identical in the wild-type and pnpA strains.

FIG. 4.

(A) Northern blot analysis of ermC mRNA with 5′ and 3′ riboprobes. RNA was isolated from wild-type (+) and pnpA (−) strains and separated on a denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel. (B) Northern blot analysis of ermC mRNA decay after rifampin addition, using the 3′ riboprobe. Above each lane is the time (minutes) after rifampin addition. FL, full-length ermC mRNA. Molecular sizes (in nucleotides) are shown on the left.

To analyze the decay of 3′-proximal fragments, the same RNA samples that were isolated after rifampin addition and probed with the 5′ oligonucleotide probe (Fig. 3B) were probed with the 3′ riboprobe (Fig. 4B). In striking contrast to the results obtained with the 5′ probe, no stable decay intermediates were detected with the 3′ probe. The half-lives of prominent RNA fragments of about 750 and 450 nt were similar to that of the full-length ermC mRNA. Thus, the absence of PNPase affects the degradation of RNA sequences that are in the upstream half of ermC mRNA but not that of RNA sequences that are 3′ proximal.

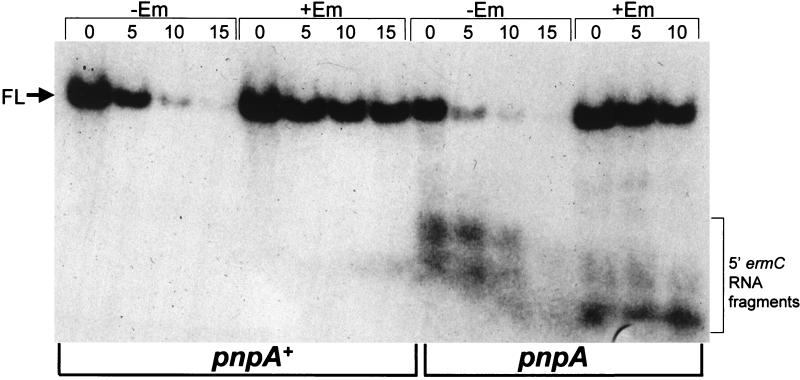

Detection of small RNAs upon induction of ermC mRNA stability.

Induction of ermC gene expression by EM is accompanied by a 20-fold increase in ermC mRNA stability (2). Stability is thought to be the result of EM-induced ribosome stalling near the 5′ end of ermC mRNA, which protects against initiation of decay (3). To examine the effect of induced stability on the pattern of 5′-proximal RNA fragments, total RNA was isolated from wild-type and pnpA mutant strains in the presence and absence of EM and examined by using the 5′ oligonucleotide probe. The results (Fig. 5) show that induced stability of full-length ermC mRNA occurs in both strains. Nevertheless, despite the induced stability in the pnpA strain, 5′-proximal RNA decay intermediates were detected in the presence of EM, as they were in the absence of EM.

FIG. 5.

Northern blot analysis of RNAs from the wild type (pnpA+) and the pnpA strain (pnpA) in the absence (−Em) and presence (+Em) of EM. RNA was separated on a formaldehyde-agarose gel and probed with the 5′ oligonucleotide probe. Aberrant running of the RNA on the gel caused the small fragments in the pnpA, −EM lanes to appear larger than the small fragments in the neighboring +Em lanes, but they are the same in size. Above each lane is the time (minutes) after rifampin addition.

mRNA decay intermediates from ermC deletion derivatives.

The effect of ermC transcript size on the formation of decay intermediates was tested by examining RNAs encoded by ermC deletion derivatives. The deletion derivatives used encoded ermC RNAs of 630, 500, and 405 nt (wild-type ermC mRNA = 910 nt; Fig. 6). (The leader region of the ermC gene used to construct these deletion derivatives is missing 42 nt of the wild-type ermC leader region; therefore, the pattern of decay intermediates differs from that of the wild type. However, induced ermC mRNA stability and methylase expression are normal.) In all cases, the deleted coding sequence retained the same reading frame. RNA was isolated either in the absence of EM or 15 min after addition of EM (inducing conditions). The results (Fig. 6) show that small RNA products were virtually undetectable in the wild-type strain but were prominent in the pnpA strain. A reduction in size to half the length of wild-type ermC RNA (pYH146) did not significantly affect the production of decay intermediates. The patterns obtained from all three deletion derivatives were similar, except for a missing 250-nt band in the strain carrying pYH146. Presumably, the RNA sequence that causes this 250-nt RNA fragment to form (e.g., an endonuclease cleavage site or a block to 3′-to-5′ exonuclease degradation) was deleted in this case. Decay intermediates were present in similar amounts whether in the presence or in the absence of EM; however, there was one particularly prominent band of about 80 nt that was observed only in the presence of EM.

Blockage of 3′-to-5′ exonuclease activity by a stalled ribosome.

We investigated further the origin of the 80-nt band that was detected only when EM was present. In the translational attenuation model of induction of ermC expression, addition of EM results in stalling of an EM-bound ribosome in the leader peptide coding sequence (Fig. 1B). Ribosome stalling results in a change of ermC leader RNA secondary structure, allowing high-level translation from RBS2 (12, 34). Changing the second leader peptide codon to a stop codon abolishes ermC induction, since the EM-bound ribosome cannot reach its stalling site (13). We determined that the prominent band observed in the presence of EM was not observed from RNA of an ermC leader region mutant in which the second codon was changed to a stop codon (data not shown), suggesting that this induced RNA fragment was a consequence of ribosome stalling.

Formation of this RNA fragment could be due to a change in the pattern of RNA decay caused by an altered leader region RNA structure or to the presence of a stalled ribosome itself. To test these possibilities, we analyzed RNA decay intermediates from two ermC leader region insertion mutations (18), which are derivatives of the ermC-containing plasmid carried in strain BE514 (partial leader region sequences are shown in Fig. 7). The first of these insertion mutations (carried in strain BE503) contained a 9-nt insert in the ermC leader region. This insert does not change the sequence of amino acids at which the ribosome stalls; however, the stalling site is 9 nt farther away from the 5′ end than in the wild type. In the second of these constructs (carried in strain BE504), an additional 9-nt insert was made such that a ribosome stalling site was created at the same distance from the 5′ end as in the wild type but upstream of the leader region secondary structure (Fig. 7 contains a comparison of ribosome stall sites in the wild type and two mutant constructs). It was shown previously (18) that although EM-induced ribosome stalling occurs in both of these constructs, only the construct carried in strain BE503 is inducible for gene expression (i.e., addition of EM results in an increase in methylase translation due to the change in leader region structure caused by ribosome stalling). The construct carried in strain BE504 is not inducible because the ribosome stalls upstream of the stem-loop structure. Thus, in strain BE504, induced ribosome stalling occurs without the induced change in leader region structure.

Northern blot analysis of ermC RNA from the wild type and two mutant constructs is shown on the right of Fig. 7. Decay intermediates from strain BE503, including the prominent EM-induced band, were clearly shifted relative to BE514, as was expected to occur due to the presence of the 9-nt insert. In the case of BE504, however, although the additional 9-nt insert caused all of the other bands to shift up, the prominent EM-induced band migrated the same distance as in the wild type. Since ribosome stalling in strain BE504 occurs at the same distance from the 5′ end as in the wild type, and an induced change in leader region structure does not occur, these data indicate strongly that the prominent band seen in the presence of EM is due to ribosome stalling itself.

Block to PNPase processivity in vivo.

One explanation for the decay intermediates observed in the pnpA strain is that these RNA fragments arise because of an inability of exonucleases other than PNPase to degrade past certain structural or sequence elements. In the wild type, PNPase attacks such RNA fragments and rapidly finishes the degradation process. The processivity of PNPase may be greater than that of any other exonuclease(s) involved in ermC mRNA decay. To test whether even PNPase activity might be blocked at particular sites in vivo, we used a substrate that had been characterized previously in vitro (26). We reported that a particular bacteriophage SP82 RNA sequence, which includes a Bs-RNase III cleavage site, contained a strong stem-loop structure that blocked B. subtilis and E. coli PNPase processivity in vitro. This SP82 sequence was cloned upstream of the 3′-terminal 200-nt segment of ermC, such that it could be transcribed in vivo to give SP82-ermC RNA (Fig. 8). Northern blot analysis was performed on RNAs isolated from the wild-type and pnpA strains. Probes complementary to the full-length RNA and to the 5′ and 3′ RNA fragments generated by Bs-RNase III cleavage were used to determine the identities of the various bands that were detected. By using the 5′ probe, a smear of hybridizing material, running below the 77-nt marker band, was detected in the wild type. Based on our previous in vitro work (26), this smear was at the expected position for RNA fragments that arise because of a block to PNPase degradation, which initiates at the 3′ end left by Bs-RNase III cleavage. In the pnpA strain, this smear was not observed, and the fragment representing the 5′ product of Bs-RNase III cleavage was more intense than in the wild type. Thus, we could observe a block to PNPase activity in the wild-type strain.

Accumulation of 5′-proximal RNA fragments from a native B. subtilis gene.

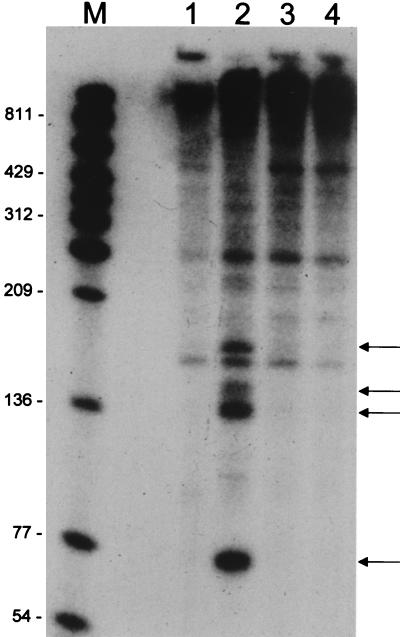

To determine whether accumulation of 5′-proximal fragments was unique to ermC, the steady-state pattern of RNA fragments was examined for the B. subtilis yybF gene. The N-terminal half of the yybF gene was cloned in a screen for B. subtilis DNA fragments that could complement the tetracycline-sensitive phenotype of the pnpA strain (33a). A plasmid carrying the yybF gene fragment, designated pTCC1-25 (TCC = tetracycline complementing), was used to transform the wild-type and pnpA mutant strains. A clear difference between the wild-type and pnpA strains, with respect to the accumulation of small RNA fragments, was observed upon Northern blot analysis (Fig. 9). The probe used was complementary to sequences near the 5′ end of the yybF transcriptional unit, which was mapped by reverse transcriptase analysis. Several prominent RNA bands were observed in the pnpA strain that were not present in the wild type (Fig. 9, lanes 1 and 2). To demonstrate that the presence of these bands in the pnpA strain was due specifically to the absence of PNPase activity, the pnpA coding region, transcribed from an ermC promoter, was cloned into the pTCC1-25 plasmid. Addition of the wild-type pnpA gene resulted in the absence of the prominent small RNA fragments in the pnpA strain (Fig. 9, lane 4). Thus, 5′-proximal yybF RNA fragments accumulated in the pnpA strain due to the loss of pnpA expression.

FIG. 9.

Northern blot analysis of yybF RNA using a 5′ yybF riboprobe. RNAs were isolated from the following: lane 1, wild type transformed with pTCC1-25; lane 2, pnpA strain transformed with pTCC1-25; lane 3, wild type transformed with pNP15 (= pTCC1-25 with the pnpA gene); lane 4, pnpA mutant strain transformed with pNP15. The arrows on the right point to prominent RNAs detected in the pnpA strain but not in the wild-type or pnpA-complemented strain. Molecular sizes (in nucleotides) are shown on the left.

DISCUSSION

The experiments described in this paper represent, to our knowledge, the first reported analysis of a specific mRNA in an RNase mutant of B. subtilis. The surprisingly healthy phenotype of the pnpA deletion strain (32) indicated that mRNA decay was not severely affected in this strain, despite earlier reports that PNPase was the major 3′-to-5′ exoribonuclease in B. subtilis (9). Measurements of bulk mRNA decay in the pnpA mutant showed only a slight difference from the wild-type decay (32). Nevertheless, the probing of ermC mRNA described here demonstrated a marked accumulation, in the pnpA strain, of what appear to be mRNA decay intermediates. In the case of yybF RNA, as well, 5′-proximal RNA decay intermediates were readily apparent in the pnpA strain (Fig. 9). There is no obvious similarity between the 5′-proximal sequences or structures of these two mRNAs that would suggest that they belong to a unique class of messages. However, since only these two mRNAs have been analyzed so far in the pnpA strain, we do not know whether our results indicate a general accumulation of 5′-proximal RNA fragments. If so, we would have to explain why measurements of bulk mRNA decay did not show a greater difference between the pnpA mutant and the wild type. Perhaps much of the accumulated RNA in the pnpA strain consists of relatively small fragments, and it is possible that our assay for bulk mRNA decay (measuring trichloroacetic acid-soluble counts) could not differentiate between these products and oligonucleotide decay products in the wild type.

How are the 5′-proximal RNA fragments generated? Two possibilities can be proposed. (i) The observed decay intermediates may be the result of a block to processivity of a 3′-to-5′ exonuclease activity (other than PNPase). This 3′-to-5′ exonuclease activity may initiate at the native 3′ end or at a 3′ end generated by internal cleavage. (ii) The observed decay intermediates may be the 5′ fragments produced by endonucleolytic cleavages in the upstream half of ermC mRNA.

The pattern of the smaller RNA fragments that were separated on denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gels, in which there were many closely spaced bands, suggests a block to 3′-to-5′ exonuclease activity. This pattern is similar to what we have observed in vitro when labeled RNA was subjected to 3′-to-5′ exonucleolytic processing and the nuclease activity was blocked at a particular site (26). The role of PNPase could be to degrade RNA fragments which are left after blocks to the processivity of other exonucleases. In a comparison of in vitro activities of E. coli RNase II and PNPase, it was shown that PNPase was less sensitive to stem-loop structure than was RNase II (24). The facts that the 3′ riboprobe did not detect a difference between the wild-type and pnpA strains (Fig. 4A) and did not detect stable decay intermediates (Fig. 4B) suggest that degradation of the 3′ region of ermC mRNA proceeds without the involvement of PNPase.

Experiments aimed at identifying the prominent band observed in the presence of EM (Fig. 6 and 7) are also consistent with a block to 3′-to-5′ exonuclease activity. The simplest interpretation of our results is that the stalled ribosome acts as a barrier to 3′-to-5′ exonucleolytic decay. (An unlikely alternative is that there is a specific endonuclease cleavage immediately downstream of the stalled ribosome.) It is not clear, however, whether the size of this band can be used to locate the leading edge of the stalled ribosome. The block to exonuclease digestion could occur some distance away from the edge of the ribosome. Experiments using endonucleolytic enzymes to digest ribosome-bound poly(U) found a protected size of 49 nt, with a distance of 23 nt from the ribosomal A site to the downstream edge (20). However, for similar experiments done 30 years ago, which used RNase II rather than endonucleases to digest the poly(U), a protected size of over 100 nt was reported (7). In any event, the absence of this prominent band in the wild type indicates that even a stalled ribosome is not a barrier to PNPase processivity. Nevertheless, we found that the SP82 RNA could block PNPase processivity in vivo (Fig. 8). It will be of interest to determine what features of this structure, which was previously determined by structure-specific RNase analysis (26), result in a block to PNPase processivity.

Although the simplest interpretation of our results is that the observed 5′-proximal fragments are normally degraded by PNPase itself, it may be that rapid and complete degradation of these fragments in the wild type is not due to PNPase directly. Rather, the activity of some other exonuclease may be affected by the presence or absence of PNPase, e.g., if this exonuclease and PNPase were in a complex similar to the degradosome of E. coli (6, 25, 27).

Multiple RNA fragments could also be the result of multiple endonucleolytic cleavages along the message or a single cleavage that gives rise to multiple bands by subsequent processing. Kennell and colleagues have argued that broad-specificity endoribonucleases are most likely to be responsible for mRNA degradation (29). In fact, Kennell’s group identified an intracellular, pyrimidine-specific endoribonuclease of B. subtilis, which was named RNase C (22). If endonuclease cleavage is responsible for the observed RNA fragments, then it should be possible to use reverse transcriptase analysis to map the 5′ ends of downstream cleavage products. Experiments with even smaller ermC derivatives, which should give a less complex pattern of decay intermediates, are currently in progress to address this point.

The process by which 5′-proximal ermC RNA fragments are generated will be highly relevant to understanding the mechanism of EM-induced ermC mRNA stability. Despite induced stability of the full-length message, a similar amount of 5′-proximal ermC RNA decay intermediates was found in the pnpA strain, whether or not EM was added (Fig. 5). If EM-induced ribosome stalling protects against decay-initiating events, we would have expected to see very little of these decay intermediates in the presence of EM. However, the observed RNA fragments could represent stable, preexisting decay intermediates that are still not degraded 15 min after addition of EM. Experiments with an ermC gene whose transcription is inducible will clarify whether ribosome stalling prevents formation of the decay intermediates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM-48804 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bechhofer D H. 5′ stabilizers. In: Belasco J, Brawerman G, editors. Control of messenger RNA decay. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1993. pp. 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bechhofer D H, Dubnau D. Induced mRNA stability in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:498–502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bechhofer D H, Zen K. Mechanism of erythromycin-induced ermC mRNA stability in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5803–5811. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.5803-5811.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belasco J G. mRNA degradation in prokaryotic cells: an overview. In: Belasco J, Brawerman G, editors. Control of messenger RNA decay. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1993. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brosius J. Compilation of superlinker vectors. Methods Enzymol. 1992;216:469–483. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)16043-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carpousis A J, Van Houwe G, Ehretsmann C, Krisch H M. Copurification of E. coli RNase E and PNPase: evidence for a specific association between two enzymes important in RNA processing and degradation. Cell. 1994;76:889–900. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castles J J, Singer M F. Degradation of polyuridylic acid by ribonuclease II: protection by ribosomes. J Mol Biol. 1969;40:1–17. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Causton H, Py B, McLaren R S, Higgins C F. mRNA degradation in Escherichia coli: a novel factor which impedes the exoribonucleolytic activity of PNPase at stem-loop structures. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:731–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deutscher M P, Reuven N B. Enzymatic basis for hydrolytic versus phosphorolytic mRNA degradation in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3277–3280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiMari J F, Bechhofer D H. Initiation of mRNA decay in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:705–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donovan W P, Kushner S R. Polynucleotide phosphorylase and ribonuclease II are required for cell viability and mRNA turnover in Escherichia coli K-12. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:120–124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.1.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubnau D. Translational attenuation: the regulation of bacterial resistance to the macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B antibiotics. Crit Rev Biochem. 1984;16:103–132. doi: 10.3109/10409238409102300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dubnau D. Induction of ermC requires translation of the leader peptide. EMBO J. 1985;4:533–537. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03661.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubnau D, Davidoff-Abelson R. Fate of transforming DNA following uptake by competent Bacillus subtilis. I. Formation and properties of the donor-recipient complex. J Mol Biol. 1971;56:209–221. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90460-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebbole D J, Zalkin H. Detection of pur operon-attenuated mRNA and accumulated degradation intermediates in Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:10894–10902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant S G N, Jessee J, Bloom F R, Hanahan D. Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs into Escherichia coli methylation-restriction mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4645–4649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gryczan T J, Grandi G, Hahn J, Grandi R, Dubnau D. Conformational alteration of mRNA structure and the posttranscriptional regulation of erythromycin-induced drug resistance. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:6081–6097. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.24.6081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hue K K, Bechhofer D H. Effect of ermC leader region mutations on induced mRNA stability. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3732–3740. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.12.3732-3740.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hue K K, Cohen S D, Bechhofer D H. A polypurine sequence that acts as a 5′ mRNA stabilizer in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3465–3471. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3465-3471.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang C, Kantor C R. Structure of ribosome-bound messenger RNA as revealed by enzymatic accessibility studies. J Mol Biol. 1985;181:241–251. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunkel T A, Bebenek K, McClary J. Efficient site-directed mutagenesis using uracil-containing DNA. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:125–139. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathur S, Cannistraro V J, Kennell D. Identification of an intracellular pyrimidine-specific endoribonuclease from Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6717–6720. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6717-6720.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayford M, Weisblum B. Messenger RNA from Staphylococcus aureus that specifies macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin resistance: demonstration of its conformation and of the leader peptide it encodes. J Mol Biol. 1985;185:769–780. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLaren R S, Newbury S F, Dance G S C, Causton H C, Higgins C F. mRNA degradation by processive 3′-to-5′ exoribonucleases in vitro and the implications for prokaryotic mRNA decay in vivo. J Mol Biol. 1991;221:81–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miczak A, Kaberdin V R, Wei C-L, Lin-Chao S. Proteins associated with RNase E in a multicomponent ribonucleolytic complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3865–3869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.3865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitra S, Bechhofer D H. In vitro processing activity of Bacillus subtilis polynucleotide phosphorylase. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:329–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.378906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Py B, Causton H, Mudd E A, Higgins C F. A protein complex mediating mRNA degradation in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:717–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shivakumar A G, Dubnau D. Characterization of a plasmid-specified ribosome methylase associated with macrolide resistance. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:2549–2562. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.11.2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Srivastava S K, Cannistraro V J, Kennell D. Broad-specificity endoribonucleases and mRNA degradation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:56–62. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.56-62.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vazquez-Cruz C, Olmedo-Alvarez G. Mechanism of decay of the cry1Aa mRNA in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6341–6348. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6341-6348.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villafane R, Bechhofer D H, Narayanan C S, Dubnau D. Replication control genes of plasmid pE194. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:4822–4829. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.10.4822-4829.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang W, Bechhofer D H. Properties of a Bacillus subtilis polynucleotide phosphorylase deletion strain. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2375–2382. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2375-2382.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang W, Bechhofer D H. Bacillus subtilis RNase III gene: cloning, function of the gene in Escherichia coli, and construction of Bacillus subtilis strains with altered rnc loci. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7379–7385. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7379-7385.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33a.Wang, W., and D. H. Bechhofer. Unpublished data.

- 34.Weisblum B. Inducible resistance to macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramin B antibiotics: the resistance phenotype, its biological diversity, and structural elements that regulate expression. In: Beckwith J, Davies J, Gallant J A, editors. Gene function in prokaryotes. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1983. pp. 91–121. [Google Scholar]