Abstract

As one of novel hallmarks of cancer, lipid metabolic reprogramming has recently been becoming fascinating and widely studied. Lipid metabolic reprogramming in cancer is shown to support carcinogenesis, progression, distal metastasis, and chemotherapy resistance by generating ATP, biosynthesizing macromolecules, and maintaining appropriate redox status. Notably, increasing evidence confirms that lipid metabolic reprogramming is under the control of dysregulated non‐coding RNAs in cancer, especially lncRNAs and circRNAs. This review highlights the present research findings on the aberrantly expressed lncRNAs and circRNAs involved in the lipid metabolic reprogramming of cancer. Emphasis is placed on their regulatory targets in lipid metabolic reprogramming and associated mechanisms, including the clinical relevance in cancer through lipid metabolism modulation. Such insights will be pivotal in identifying new theranostic targets and treatment strategies for cancer patients afflicted with lipid metabolic reprogramming.

Keywords: cancer, cholesterol, circRNAs, fatty acids, lipid metabolic reprogramming, lncRNAs

The lipid metabolism‐related lncRNAs and circRNAs have emerged as rising epigenetic binary superstars in regulating lipid metabolic reprogramming of cancers. In this review, their regulatory targets, associated mechanisms, as well as clinical relevance are summarized to cast light on identifying new theranostic targets and treatment strategies for cancer patients afflicted with lipid metabolic reprogramming.

1. Introduction

Since the recognition of metabolic reprogramming as a crucial characteristic of cancer in 2011,[ 1 ] numerous reviews have documented various features of metabolic reprogramming in different types of cancer.[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ] In response to the demands of uncontrolled proliferation and the stress derived from the surrounding microenvironment, such as hypoxia and nutrient deprivation, cancer cells require more glucose, glutamine, and fatty acids to support rapid ATP generation, increased biosynthesis of macromolecules, and redox homeostasis, compared to normal cells. Consequently, several metabolic phenotypes have emerged in cancer, including excessive glucose and/or glutamine uptake, increased aerobic glycolysis and lactate secretion, and alterations in lipid synthesis and degradation. These metabolic features are shaped by oncogenic stimuli, such as the inactivation of tumor suppressors or activation of oncogenes or imposed by the harsh tumor microenvironment.[ 7 , 8 , 9 ]

To cope with oncogenic and environmental stimuli, various metabolic enzymes and signaling pathways in regulating glucose, glutamine and lipid metabolism are activated or dysregulated. The hallmark of “aerobic glycolysis” or “Warburg effect” is the most important metabolic alteration in cancer, where cancer cells prefer glycolysis for energy and biosynthesis of biomass, rather than mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, even in the presence of oxygen. Subsequently, amino acid (e.g., glutamine, serine and glycine) and lipid (e.g., fatty acid and cholesterol) metabolism have also been identified as important metabolic aberrations for carcinogenesis, progression and metastasis. In addition to elevated expression and activation of metabolic enzymes and signaling pathways, accumulating evidences have been demonstrated that the non‐coding RNAs also respond to these oncogenic and environmental stimuli and play critical roles in metabolic reprogramming of cancer though diverse epigenetic regulatory mechanisms.[ 8 , 10 , 11 ]

With the rapid development of RNA‐seq technologies and bioinformatics analysis in the last decades, various non‐coding RNAs have been discovered to play pleiotropic functions in regulation of gene expression under physiological and pathologic conditions. Non‐coding RNAs are typically classified into three categories based on their sizes and structures: small non‐coding RNAs (less than 200 nucleotides), long non‐coding RNAs (lncRNAs, more than 200 nucleotides) and circular RNAs (circRNAs).[ 11 , 12 ] Regarding their molecular functions, microRNAs (miRNAs) are often utilized by argonaute proteins to either facilitate the degradation of targeted mRNAs or hinder their translation through full or partial complementarity. However, lncRNAs and circRNAs play diverse roles in regulating genes expression by interacting with DNA, RNA and proteins, including chromatin modification, transcriptional interference or activation as ceRNAs (competing endogenous RNAs) and scaffolds for protein complexes, even partially acing as protein/peptide translational templates.[ 12 , 13 , 14 ] Increasing evidence has confirmed that non‐coding RNAs are often dysregulated but play as key epigenetic regulators in many hallmarks of cancer, including metabolic reprogramming, facilitating uncontrolled proliferation, invasion and metastasis of cancer cells by adjusting nutrient uptake and metabolic reactions. While non‐coding RNAs are well‐documented in glucose metabolism, there is less information on their roles in lipid metabolic reprogramming of cancer, especially lncRNAs and circRNAs.[ 15 , 16 ] Therefore, this review offers a comprehensive analysis of the regulatory functions exhibited by lncRNAs and circRNAs in the lipid metabolic reprogramming of cancer. Such insights will be pivotal in identifying new theranostic targets and treatment approaches for cancer patients afflicted with lipid metabolic reprogramming.

2. Overview of Lipid Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer

Lipids in normal cells mainly consist of vast and complex groups of hydrophobic biomolecules, including fatty acids and cholesterols, which play a plethora of roles in bio‐membranes’ integrity and flexibility, energy storage and utilization, as well as protein modification and signal transduction.[ 8 ] Lipid metabolism is a dynamic biological process that entails endogenous de novo synthesis and exogenous import of fatty acid and cholesterol, fatty acid β oxidation and cholesterol efflux, biogenesis and lipolysis of lipid droplets, and more.[ 17 , 18 ] However, the lipid metabolism is rewired in almost all types of cancer to support tumorigenesis, progression, metastasis, even stemness maintenance and chemotherapy resistance, which is mediated by various key lipid‐metabolic enzymes, transcriptional factors and signaling pathways in this dynamic process.[ 5 , 17 , 19 , 20 ]

2.1. Endogenous de Novo Synthesis and Exogenous Import of Fatty Acid and Cholesterol in Cancer

While most lipids in normal somatic cells come from fatty acids and cholesterols that derive from either dietary uptake or synthesis from hepatocytes and adipocytes,[ 21 , 22 ] various cancers prefer to thrive on intracellular de novo lipogenesis rather than utilizing exogenous sources under lipids‐constrained conditions. However, upon hypoxia or in adipose‐rich environments, these cancers switch toward extracellular lipids uptake (Figures 1 and 2 ).[ 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]

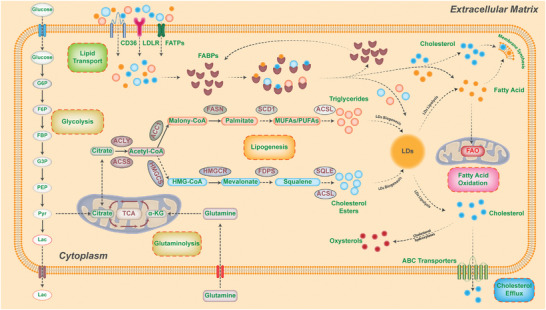

Figure 1.

Rewiring of lipid metabolism in cancer. Lipid metabolism is a dynamic biological process that involves the endogenous de novo synthesis, exogenous import of fatty acids and cholesterol, fatty acid β oxidation, cholesterol efflux, biogenesis, and lipolysis of lipid droplets. Intracellular de novo lipogenesis begins with acetyl‐coenzyme A (acetyl‐CoA) derived from acetate by ATP‐citrate lyase (ACLY) or citrate by acetyl‐CoA synthetase (ACSS). Fatty acid synthesis requires acetyl‐CoA carboxylation into malonyl‐CoA by acetyl‐CoA carboxylases (ACC1/2), followed by the condensation of seven malonyl‐CoA molecules and one acetyl‐CoA molecule into the saturated 16‐carbon palmitate (16:0) by fatty acid synthase (FASN). Palmitate is then desaturated by stearoyl‐CoA desaturases (SCD) or elongated by fatty acid elongases (ELOVL) to form the monounsaturated 16‐carbon palmitoleate (16:1 n‐7) or 18‐carbon oleate (18:1 n‐9). Biogenesis of cholesterol also begins with acetyl‐CoA via the mevalonate pathway, which results in the synthesis of squalene and finally, cholesterol. Cancer cells can acquire fatty acids and cholesterol from various extracellular sources, such as LDL particles or fatty acid transport proteins. When lipids accumulate, cancer cells use these lipids to meet their energy consumption demand and redox homeostasis through fatty acid oxidation or β‐oxidation. Excess cholesterol is exported to the blood or converted into oxysterols through oxidation processes. Surplus fatty acids are esterified with glycerol or cholesterol into triglycerides and cholesteryl esters, which are incorporated into lipid droplets (LDs). When energy or membrane synthesis is needed, lipid droplets can be rapidly lipolyzed into free fatty acids and cholesterols to facilitate cancer cell proliferation and progression.

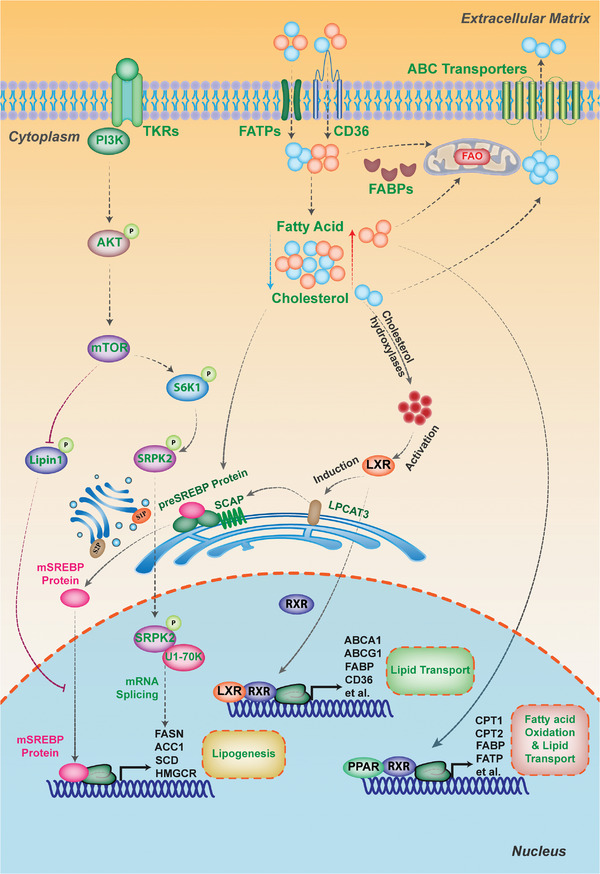

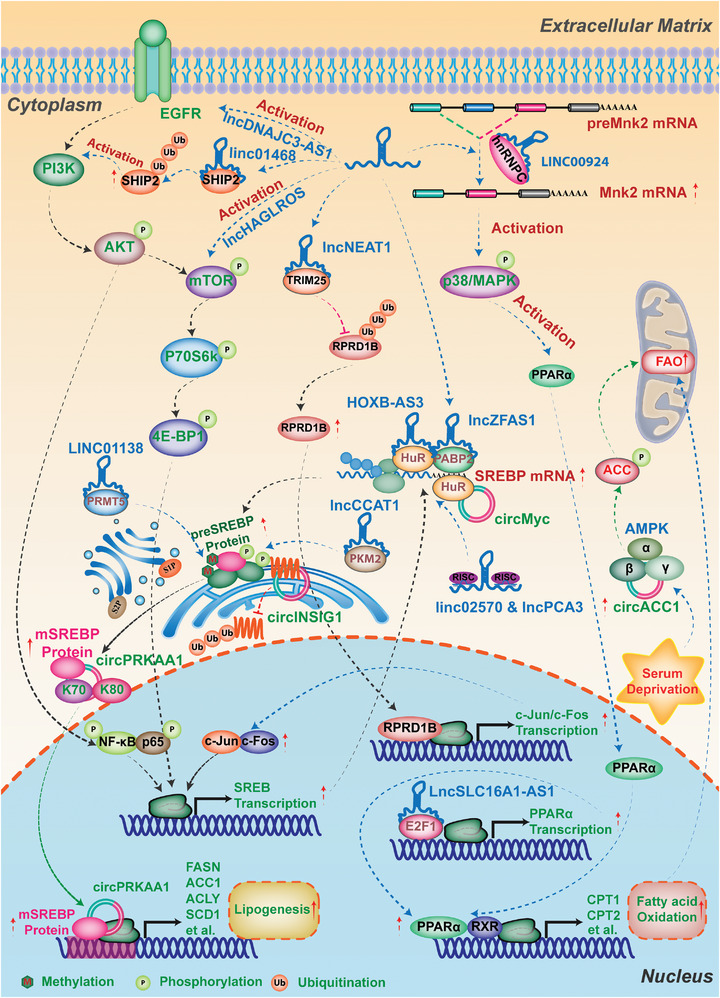

Figure 2.

Transcriptional factors and oncogenic signaling pathways in lipid metabolism of cancer. Sterol regulatory element‐binding proteins (SREBPs) act as transcriptional factors that control the expression of most lipogenic enzymes involved in cholesterol and fatty acid biosynthesis. When lipid levels decrease, SREBPs are released from the SCAP‐INSIG complex in the endoplasmic reticulum and translocate to the Golgi, where they are cleaved by site‐1 and site‐2 proteases to release their active N terminus (mature SREBPs). Mature SREBPs move into the nucleus and bind to sterol response elements (SRE) in downstream target gene promoters to initiate transcription. The PI3K‐AKT‐mTOR pathway is frequently dysregulated in human cancers and can be activated by growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). The mTOR complexes participate in lipogenesis regulation through SREBP‐dependent or independent mechanisms. The mTOR‐dependent sequestration of Lipin‐1 in the cytoplasm enhances SREBP‐transcriptional activity in the nucleus, while the mTORC1/S6K1/SRPK2/U1‐70K axis increases mRNA splicing of lipogenic genes, such as FASN and ACLY. Liver X receptor (LXR) is an additional regulator of lipogenesis and a nuclear transcription factor receptor that senses oxysterols, cholesterol derivatives, to form the LXR‐RXRα complex. This complex induces the expression of genes involved in cholesterol efflux, such as ABCA1, and several lipogenic genes, including FASN and SCD. Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptors (PPARs) are regulators of lipid metabolism and play vital roles in lipid β‐oxidation and storage in harsh environments when cellular energy is needed.

Intracellular de novo lipogenesis begins with acetyl‐coenzyme A (acetyl‐CoA), derived from acetate by ATP‐citrate lyase (ACLY) or citrate by acetyl‐CoA synthetase (ACSS), thereby connecting to other metabolic pathways like glucose and glutamine metabolism (Figure 1).[ 27 , 28 ] For de novo synthesis of fatty acids, acetyl‐CoA is initially converted into malonyl‐CoA by acetyl‐CoA carboxylases (ACC1/2), which is an essential, irreversible, and rate‐limiting step of de novo fatty acid. ACC1/2 has been identified to be active and highly expressed in several human cancers.[ 29 , 30 ] Subsequently, fatty acid synthase (FASN) condenses one molecule of acetyl‐CoA and seven malonyl‐CoA molecules into the saturated 16‐carbon palmitate (16:0). FASN is also an important but dysregulated lipid‐metabolic enzyme in many human epithelial cancers and strongly relevant with malignant progression and poor prognosis of tumors.[ 31 , 32 , 33 ] Palmitate is then desaturated by stearoyl‐CoA desaturases (SCD) or/and elongated by fatty acid elongases (ELOVL) to form the monounsaturated 16‐carbon palmitoleate (16:1 n‐7) or 18‐carbon FA oleate (18:1 n‐9), which will provide key cornerstones for the generation of complex lipids like phospholipids and glycolipids.[ 34 , 35 , 36 ] Thereinto, SCD1 overexpression has been demonstrated to contribute tumor development, inactivate the responses to sorafenib treatment, and associate with poor disease‐free survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).[ 19 , 37 ]

Concerning the de novo biogenesis of cholesterols, it also originates from acetyl‐CoA but goes through the mevalonate pathway (Figure 1). In this pathway, HMG‐CoA synthase (HMGCS) catalyzes the formation of 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl (HMG)‐CoA by condensing acetyl‐CoA and acetoacetyl‐CoA, which subsequently is reduced into mevalonate by HMG‐CoA reductase (HMGCR). The mevalonate subsequently undergoes a series of reactions to form the isoprenoid farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), which is then synthesized into squalene, and finally converted to cholesterol. Thereinto, the HMGCR and squalene epoxidase (SQLE) are the rate‐limiting enzymes of this process, and have been found to be dysregulated in multiple types of cancer, including prostate and breast cancers, gastric and colorectal cancers, and are positively associated with the growth and migration, radioresistance and poor prognosis of these cancers.[ 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 ] Alternatively, FPP can be used to produce geranylgeranyl‐pyrophosphate (GGPP), both of which are substrates for the prenylated modification of proteins, such as Rho GTPases prenylation, and synthesis of dolichol and ubiquinone (coenzyme Q10).[ 42 , 43 , 44 ]

Apart from de novo biosynthesis, fatty acids and cholesterols can be obtained from several extracellular sources (Figure 1). For instance, cholesterol from external sources is chiefly acquired through a process of endocytosis mediated by low‐density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) or scavenger receptor B1 (SR‐B1), involving plasma LDL particles. Free fatty acids can also be absorbed into cancer cells via overexpression of fatty acid translocase (CD36) or fatty acid transport proteins (FATPs). Additionally, the upregulation of fatty acid‐binding proteins (FABPs) in cancer cells has been found to aid in the uptake of exogenous fatty acids,[ 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 ] These receptors and transporters have been identified as critical factors in the proliferation, metastasis, and epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT) of various types of cancer, including glioblastoma, breast cancer, and HCC.[ 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 ]

2.2. Fatty Acid Oxidation and Cholesterol Efflux in Cancer

As the fatty acids and cholesterols from either de novo biogenesis or exogenous uptake are increasingly accumulated, cancer cells can utilize these lipids to meet their demands of energy consumption and redox homeostasis via fatty acid oxidation (FAO) or β‐oxidation in mitochondria and peroxisome under harsh tumor microenvironment (Figure 1).[ 5 , 18 ] FAO is a repeated catabolic process of fatty acids shortening, with each cycle shortening two carbons from fatty acids to produce ATP, NADH and FADH2. The NADH and FADH2 can fuel the electron transport chain (ETC) of mitochondria to produce ATP, except for maintaining redox power.[ 53 ] During this process, the carnitine palmitoyltransferase (CPT) system plays a critical role in transportation of fatty acids, composed of CPTI, CPTII, carnitine acylcarnitine translocase (CACT), and carnitine acetyltransferase (CRAT). All of them have been shown to be dysregulated in various cancers, promoting the resistance of cancer cells to energy stress.[ 54 , 55 ] For instance, as one of the rate‐limiting enzymes in FAO, CPTI can convert FA‐CoA into the carnitine derivatives to enter into the routes of mitochondrial and peroxisomal β‐oxidation.[ 56 , 57 ] No surprisingly, it has been found to be highly correlated with poor prognosis of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or ovarian cancer.[ 36 , 53 ]

In addition, surplus cholesterol can be exported to the bloodstream via ATP‐binding cassette (ABC) transporters or converted into oxysterols via oxidation processes (Figure 1). These oxysterols then directly activate the transcription factors Liver X Receptor (LXR), promoting ABCA1 and ABCG1 expressions and E3 ubiquitin ligase‐mediated LDLR degradation, thereby reducing the intracellular excessive cholesterols.[ 58 , 59 , 60 ] Recently, ABC transporters have been found to be overexpressed in multiple cancers, contributing dissemination and metastasis of cancer cells, and associated with resistance to a plethora of drugs.[ 61 ] Additionally, LXRs and their ligands have also been found to be upregulated in various cancers, such as prostate carcinoma, breast and ovaries carcinoma, and multiple myeloma, playing vital roles in the proliferation and survival of cancer cells.[ 62 ]

2.3. Biogenesis and Lipolysis of Lipid Droplets in Cancer

Besides FAO and cholesterol efflux, excess fatty acids are esterified with glycerol or cholesterol into triglycerides (TGs) and cholesteryl esters (CEs), furtherly incorporated into lipid droplets (LDs), which are cytoplasmic organelles for energy storage, redox homeostasis and entrapment of anticancer drugs in cancer cells (Figure 1).[ 63 , 64 , 65 ] The synthesis of TGs and CEs is usually conducted by endoplasmic reticulum (ER)‐resident enzymes: diacylglycerol acyltransferases (DGAT1 and DGAT2) that are involved into the synthesis of TGs, CEs are esterified by acyl‐coenzyme A:cholesterol O‐acyltransferases (ACAT1 and ACAT2).[ 17 , 66 ] These enzymes have also been found to be associated with malignant phenotypes of several cancers. For instance, ACAT1 has been identified to be overexpressed in glioblastomas, prostate or pancreas cancers, exerting pro‐tumorigenesis function, and is positively correlated with poor survival of these patients.[ 67 , 68 ]

When energy or membrane synthesis is required, LDs can be rapidly lipolyzed into free fatty acids and cholesterols to facilitate proliferation and progression of cancer cells. This process is primarily catalyzed by various lipases and activators, including adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL), hormone‐sensitive lipase (HSL), and monoglyceride lipase (MGLL) (Figure 1). Thereinto, ATGL is a rate‐limiting enzyme but its roles are complex in different types of cancer.[ 69 , 70 ] For instance, ATGL can promote proliferation and invasiveness in prostate, lung and colorectal cancer cells, but acts as a suppressor of malignancy in other types of cancers.[ 70 , 71 ] More interestingly, breast cancer cells can obtain free fatty acids to promote autologous proliferation and migration via ATGL‐dependent lipolysis in both itself and adipocytes in the local environment.[ 72 ]

2.4. Transcriptional Factors and Oncogenic Signaling Pathways in Lipid Metabolism of Cancer

As transcriptional factors, the sterol regulatory element‐binding proteins (SREBPs) play a key role in controlling most lipogenic enzymes’ expression at the transcriptional level, involving in cholesterol and fatty acid biosynthesis (Figure 2). Under normal conditions with sufficient intracellular lipid levels, SREBP proteins are translated as precursors and retained in the ER membrane by binding to the SREBP cleavage‐activating protein (SCAP)‐insulin induced gene (INSIG) complex. However, when the lipid levels decrease, SREBPs are released and translocated from SCAP‐INSIG complex in ER to the Golgi. Subsequently, the site‐1 and site‐2 proteases cleave SREBPs, producing their active N terminus (mature SPRBPs). These mature SPRBPs then enter the nucleus to bind to sterol response elements (SRE) in the promoters of downstream target genes and initiate the transcription. SREBP proteins come into three isoforms, with SREBP‐1a and SPREBP‐1c primarily governing fatty acids and TG's biosynthesis, while SREBP‐2 selectively facilitates the expression of enzymes involved in cholesterol biosynthesis.[ 73 , 74 ] These processes are highly regulated by intracellular levels of sterols, status of PI3K/Akt /mTOR signaling, and extracellular insulin and growth factors.[ 5 ] which are always dysregulated in various cancers, including glioblastomas, breast cancer and HCC.[ 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 ]

Liver X receptor (LXR), another regulator of lipogenesis, is a nuclear transcription factor receptor that regulates many genes involved in fatty acid and cholesterol homeostasis (Figure 2). LXR acts as a sensor of oxysterols, derivatives of cholesterol, to form the LXR‐RXRα (retinoid X receptor α) complex. This complex then induces the expression of genes involved in cholesterol efflux such as ABCA1 and several lipogenic genes such as FASN and SCD.[ 80 ] Therefore, using antagonists against LXR may be a new anti‐cancer choice. For instance, the tumor growth of glioblastoma, breast cancer or prostate cancer was significantly inhibited by synthetic LXR agonists GW3965 and T0901317 in vivo.[ 52 , 81 ] In addition, peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptors (PPARs), another regulator of lipid metabolism, play key roles in lipid β‐oxidation and storage. However, their roles in cancer metabolism are not fully understood.[ 80 ]

In addition to these nuclear transcription factors, some oncogenic signaling pathways take part in regulating lipid metabolism to shape the tumors’ unique lipidome.[ 45 ] The PI3K‐AKT‐mTOR pathway, which is regularly disrupted in a variety of human cancers, can be induced by activating growth‐factor receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), as shown in Figure 2.[ 82 ] When this pathway was activated, AKT is primarily involved in two crucial processes that fuel de novo lipid synthesis: transportation of metabolic intermediates to provide carbon sources and the production of reducing equivalents in the form of NADPH.[ 83 ] Additionally, mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) complexes play a vital role in regulating lipogenesis with both SREBP‐dependent and SREBP‐independent pathways: sequestrating Lipin‐1 in the cytoplasm, which enhances SREBP‐transcriptional activity in the nucleus, and increasing mRNA splicing of lipogenic genes like FASN, ACLY, and ACSS2 via the mTORC1‐S6 kinase 1 (S6K1)‐serine/arginine protein kinase 2 (SRPK2)‐U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein 70 kDa (U1‐70K) axis.[ 77 , 84 ]

3. Sketching the Potential Regulatory Mechanism of lncRNAs‐circRNAs in Gene Expression

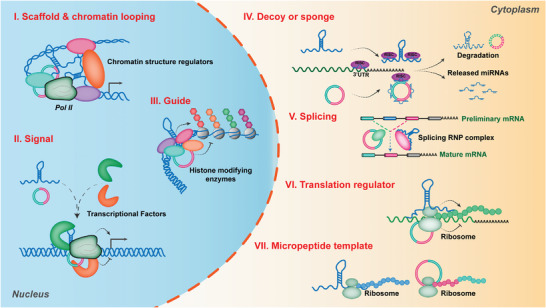

Based on their subcellular localizations, lncRNAs and circRNAs play distinct regulatory roles in the expression of target genes[ 8 , 9 , 10 , 85 ] (Figure 3 ). In the nucleus, lncRNAs and circRNAs can act as scaffolds, signals or guides to modulate chromatin conformation, transcription factor recruitment or histone modification status.[ 86 ] For instance, lncRNA HOTTIP can bind the 5′ regions of several HOXA genes cluster to form chromatin looping, which recruits the WDR5‐MLL histone methyltransferase complex to the promoters of these genes, thereby facilitating gene expression through H3K4me3 in mouse haematopoietic stem cells.[ 87 ] As a pluripotency‐associated lncRNA, lncPRESS1 can bind Sirtuin 6 to facilitate the transcription of pluripotency‐related genes with transcription‐permissive H3 acetylated at Lys56 (H3K56ac) and H3K9ac in human ESCs.[ 88 ] EIciRNAs (exon‐intron circRNAs), such as circEIF3J and circPAIP2, can interact with U1 snRNA and Pol II to form transcription complex at the promoter, thereby enhancing parental gene transcription.[ 89 ]

Figure 3.

Potential mechanisms of lncRNAs & circRNAs in regulating gene expression. I) Regulation of genes transcription as a scaffold via binding with chromatin structure regulators; II) Regulation of gene transcription as a signal via recruiting transcriptional factors on promoter of target genes; III) Regulation of gene transcription as a guide via binding with histone modifying enzymes; IV) Decoying miRNAs as sponges; V) Modulating splicing of preliminary target mRNAs; VI) regulating target mRNA translation via binding with ribosome; VII) Functioning as templates to translate into micropeptides.

In the cytoplasm, lncRNAs and circRNAs modulate the stability, splicing and translation of target gene mRNAd via RNA‐protein or RNA‐RNA interactions, such as decoying miRNAs as sponges, modulating splicing of preliminary target mRNAs, and regulating of mRNA translation via binding with ribosome. A number of lncRNAs and circRNAs bearing microRNA (miRNA)‐complementary sites can act as competitive endogenous RNAs or “sponges” of miRNAs to enhance the expression of target mRNAs, such as the lncRNA‐PNUTS/ miR‐205/ ZEB1and ZEB2 axis in the migration and invasion of breast cancer cell,[ 90 ] and the circEZH2/ miR‐133b/IGF2BP2 axis in colorectal cancer progression.[ 91 ] Moreover, lncRNAs and circRNAs can directly or indirectly facilitate the alternative splicing of target genes,[ 92 ] such as ZEB2‐anti (ZEB2‐antisense RNA) in the regulation of ZEB2 pre‐mRNA alternative splicing and translation,[ 93 ] and the circRAPGEF5/RBFOX2 splicing axis in the formation of TFRC with exon‐4 skipping.[ 94 ] Furthermore, HOXB‐AS3 has been found to regulate ribosomal RNA transcription and de novo protein synthesis via binding and guiding EBP1 to the ribosomal DNA locus.[ 95 ] In addition, a novel 161‐amino‐acid protein encoded by circRsrc1 has been recently identified to bind mitochondrial protein C1qbp to modulate the assembly of mitochondrial ribosomes during spermatogenesis.[ 96 ]

Interestingly, some lncRNAs and circRNAs have the potentials to be translated into micropeptides in cap‐dependent, or IRES‐dependent, or m6A‐dependent manners. For instance, circ‐AKT3 holds the potential to encode a novel 174 amino acid (aa) protein, which inhibits the proliferation, radiation resistance and in vivo tumorigenicity of GBM cells via interacting with phosphorylated PDK1, thereby modulating the PI3K/AKT signal intensity.[ 97 ] Moreover, consensus m6A motifs has been found to be enriched in circRNAs, which can drive translation initiation with initiation factor eIF4G2 and m6A reader YTHDF3.[ 98 ] Certain lncRNAs and circRNAs distribute in both cellular chambers, and they can shuttle between cytoplasm and nucleus to play diverse roles in regulating the expression of target genes. For example, with the help of two RBPs, HuR and GRSF1, nuclear DNA‐encoded lncRNA RMRP was imported into mitochondria to maintain structure and mediate oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondrial DNA replication.[ 99 ] LINC00473 has been identified to shuttle between mitochondria and lipid drops to modulate lipolysis and mitochondrial oxidative functions in human thermogenic adipocytes.[ 100 ]

4. LncRNAs‐circRNAs Regulate the Rewiring of Lipid Metabolism in Cancer

Apart from various key lipid metabolic enzymes, transcriptional factors and oncogenic signaling pathways as mentioned above, numerous studies have demonstrated that non‐coding RNAs, especially lncRNAs and circRNAs, are extensively dysregulated in various malignant tumors and play crucial roles in cancer metabolic reprogramming, especially in lipid metabolism. These dysregulated lncRNAs and circRNAs in lipid metabolic reprogramming (known as lipid‐metabolic related lncRNAs and circRNAs) not only support the demand of rapid ATP generation, biosynthesis of macromolecules and maintenance of appropriate redox status in cancer, but also promote cancer cells to disseminate to distal organs and resist to radiochemotherapy, even involving the mechanism of anti‐ferroptosis.[ 12 , 18 , 101 , 102 ] In the following sections, we will summarize the lipid‐metabolic related lncRNAs and circRNAs and their targets in lipid‐metabolic reprogramming of cancer, analyze their multiple regulatory mechanisms and display their various relevant biological functions in detail (Figures 4 , 5 , 6 , Tables 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ).

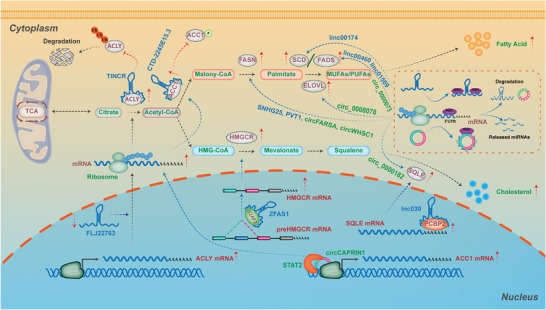

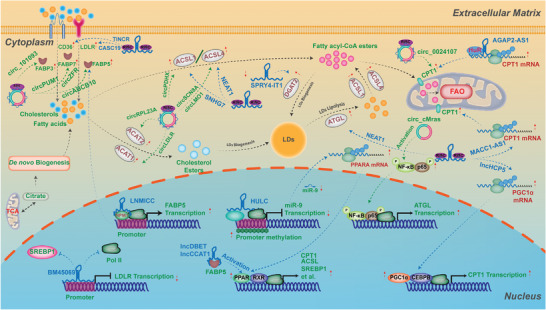

Figure 4.

The lncRNAs & circRNAs in regulating lipogenesis of cancer. During the process of de novo lipogenesis, there are multiple rate‐limiting enzymes modulated by various lipid‐related lncRNAs and circRNAs to affect lipid metabolism reprogramming in cancer with distinct regulatory mechanisms. For de novo biogenesis of fatty acids, lncRNA TINCR and FLJ22763 have been identified to modulate ACLY expression in different cancer cells. The first rate‐limiting enzyme in the de novo synthesis of fatty acid, ACC1, has been shown to be regulated by circCAPRIN1, lncRNAs CTD‐2245E15.3 and TSPEAR‐AS2. With respect to other fatty acid synthetases, there are various lncRNAs and circRNAs involving the expression of these enzymes, functioning as the sponges of miRNAs, such as the lncRNA SNHG25/miR‐497‐5p/FASN axis, the circFARSA/miR‐330‐5p and miR‐326/FASN axis, the circ_0 008078/miR‐191‐5p/ELOVL4 axis, the circ_0 008078/miR‐191‐5p/ELOVL4 axis, the linc00174/miR‐145‐5p/SCD5 axis, and the circ_0000073/ miR‐1184/ FADS2 axis. For de novo biogenesis of cholesterols, lncRNAs ZFAS1 and AT102202 have been shown to regulate the expression of HMGCR, while lnc30 and circ_0000182 have been identified to modulate the expression of SQLE. Detailed mechanisms of these lipogenesis‐related lncRNAs and circRNAs in cancer are described in the main text.

Figure 5.

The lncRNAs & circRNAs in regulating lipid transport, lipid droplets (LDs) metabolism, and lipolysis of cancer. With respect to lipid transport, lipid droplet metabolism, and lipolysis in cancer, various lipid‐related lncRNAs and circRNAs have been shown to play variable roles through the RNA‐RNA, RNA‐protein, and RNA‐DNA interactions. For the RNA‐RNA interaction, lipid‐related lncRNAs and circRNAs act as sponges of miRNAs to release miRNAs‐mediated repression of target genes, such as the circ_ABCB10/miR‐620/FABP5 axis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), the circ_101 093/FABP3/ FABP3 axis in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), and the lncHCP5/miR‐3619‐5p/CPT1 axis in gastric cancer. For the RNA‐protein interaction, these lipid‐related lncRNAs and circRNAs hold the potential to bind transcriptional factors, posttranslational modifiers, or RNA‐ binding proteins to modulate the expression, stability and activation of key rate‐limiting enzymes. For instance, lncLNMICC binds transcriptional factor‐NPM1 to promote the expression of FABP5 in cervical cancer; lncRNA CCAT1 binds USP49 to regulate FKBP51‐mediated AKT phosphorylation, thereby promoting FABP5 expression in LUAD; lncRNA AGAP2‐AS1 binds HuR protein to enhance protein stability of CPT1 in MSC‐cocultured Breast cancer (BC). For the RNA‐DNA interaction, lncRNA BM450697 has been found to directly bind the DNA of the LDLR promoter, thereby inhibiting lipid uptake in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), while lncRNA HULC is able to induce methylation of CpG islands in the promoter of miR‐9 to promote ACSL1 expression and ACSL1‐mediated lipogenesis in HCC. Detailed mechanisms of these lncRNAs and circRNAs for lipid transport, LDs metabolism and lipolysis are described in the main text.

Figure 6.

The lncRNAs & circRNAs in regulating lipid metabolic transcriptional factors and oncogenic signaling pathways of cancer. SREBP is the major transcriptional factor to regulate biogenesis of fatty acids and cholesterols at transcriptional levels. The lipid‐related lncRNAs and circRNAs in cancer can modulate the expression and stability of SREBPs through various regulatory mechanisms, including sponging miRNAs, binding protein and DNA, and affecting signaling pathways, even via modulating their regulators. Additionally, some lipid‐related lncRNAs and circRNAs have been shown to involve in regulating lipid metabolism in cancer via oncogenic signaling pathways, such as the PI3K‐AKT‐mTOR signaling pathway, the AKT/FoxO1/LXRα/RXR axis, and the p38 MAPK/PPARα signaling pathway. Detailed mechanisms of these lncRNAs and circRNAs in lipid metabolic transcriptional factors and oncogenic signaling pathways of cancer are described in the main text.

Table 1.

The lncRNAs‐circRNAs in regulating de novo synthesis of fatty acid and cholesterol of cancer.

| Lipid metabolic lncRNAs | Status in tumor | Lipid metabolic process | Cancer types | Clinical association | Functional impact | Interactor | Target/effect | Mechanistic classification | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TINCR | Up‐regulated | De novo fatty acid synthesis | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) |

Overall survival↓ Disease free survival↓ Distant‐metastasis↑ |

Proliferation↑ Metastasis↑ Cisplatin resistance↑ |

ACLY | Increasing the cellular acetyl‐CoA level to promote lipid synthesis |

Binding with protein (Binding ACLY protein to maintain its stability by inhibiting its ubiquitination‐mediated degradation) |

[103] |

| FLJ22763 | Down‐regulated | De novo fatty acid synthesis | Gastric cancer (GC) |

Histological grade↑ Depth of invasion↑ |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Invasion↑ Tumorigenesis↑ |

N.A | mRNA and protein expression of ACLY↑ | N.A | [104] |

| CTD‐2245E15.3 | Up‐regulated | De novo fatty acid synthesis | Non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | N.A | Proliferation↑ | ACC1 | Promoting ACC1‐mediated lipogenesis to facilitate tumor cell proliferation |

Binding with protein (Binding ACC1 to decrease phosphorylation of ACC1 at an inhibitory site) |

[106] |

| TSPEAR‐AS2 | Up‐regulated |

De novo fatty acid synthesis |

Colorectal cancer (CRC) | Predictor of overall survival | Fatty acid metabolism↑ | N.A | Regulating ACC1 and FASN‐mediated the fatty acid synthesis | N.A | [107] |

| CircCAPRIN1 | Up‐regulated | De novo fatty acid synthesis | Colorectal cancer (CRC) |

TNM stages↑ Clinical stages↑ Overall survival↓ DFS↓ |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ EMT↑ |

STAT2 |

Expression of ACC1↑ Fatty acid synthesis↑ |

Binding with protein (Binding to STAT2 to transcriptionally activate ACC0 gene expression) |

[105] |

| SNHG25 | Up‐regulated | De novo fatty acid synthesis | Endometrial cancer (EC) | Overall survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Invasion↑ |

miR‐497‐5p | Regulating FASN‐mediated tumor growth |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐497‐5p‐mediated repression of FASN expression) |

[108] |

| HAGLR | Up‐regulated | De novo fatty acid synthesis | Non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) |

Clinical stage↑ Lymph node metastasis status↑ Overall survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Lipogenesis↑ Invasion↑ |

FASN | Regulating FASN‐mediated lipogenesis and growth | N.A | [116] |

| HOTAIR | Up‐regulated | De novo fatty acid synthesis | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Lipogenesis↑ Invasion↑ |

N.A | Promoting FASN‐mediated lipogenesis, proliferation and invasion | N.A | [115] |

| PVT1 | Up‐regulated | De novo fatty acid synthesis | Osteosarcoma (OS) |

Metastasis status↑ Overall survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Invasion↑ Cell cycle arrest↓ Apoptosis↓ |

miR‐195 | Promoting FASN‐mediated lipogenesis, migration and invasion |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐195‐mediated repression of BCL2, CCND1 and FASN expression) |

[109] |

| CircFARSA | Up‐regulated | De novo fatty acid synthesis | Non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | Overall survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Lipogenesis↑ Invasion↑ |

miR‐330‐5p miR‐326 |

Promoting FASN‐mediated the proliferation and migration |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐330‐5p and miR‐326‐mediated repression of FASN expression) |

[110] |

| CircWHSC1 | Up‐regulated | De novo fatty acid synthesis | Breast cancer (BC) |

Tumor stages↑ Lymphatic metastasis↑ Overall survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Lipogenesis↑ Invasion↑ |

miR‐195‐5p | Promoting FASN‐mediated AMPK inhibition and mTOR activation to facilitate proliferation and migration |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐195‐5p‐mediated repression of FASN expression) |

[111] |

| CircZFAND6 | Up‐regulated | De novo fatty acid synthesis | Breast cancer (BC) | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Metastasis↑ |

miR‐647 | FASN‐mediated proliferation and metastasis↑ |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐647‐mediated repression of FASN expression) |

[112] |

| Circ_0018909 | Up‐regulated | De novo fatty acid synthesis | Pancreatic carcinoma (PC) | Clinical stage↑ |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ EMT↑ Apoptosis↓ |

miR‐545‐3p |

FASN‐mediated progression↑ M2 macrophage polarization↑ |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐545‐3p‐mediated repression of FASN expression) |

[113] |

| CircMBOAT2 (hsa_circ_0 0 07334) | Up‐regulated | De novo fatty acid synthesis | Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) |

Tumor size↑ Overall survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Colony formation↑ Cell cycle progression↑ Apoptosis↓ |

PTBP1 |

Stability of PTBP1↑ Lipid metabolism reprogramming↑ |

Binding with protein (Binding to PTBP1 to promote PTBP1‐mediated cytoplasmic export of FASN mRNA) |

[114] |

| FASRL | Up‐regulated | De novo fatty acid synthesis | Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | Overall survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Apoptosis↓ |

ACACA | Decreasing the level of phosphorylated ACACA (Ser79) |

Binding with protein (Binding ACACA to inhibit its phosphorylation, thus increasing FA synthesis) |

[117] |

| Circ_0008078 | Down‐regulated | De novo fatty acid biosynthesis‐Elongation | Esophagus cancer (EC) | Overall survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Invasion↑ Tube formation↑ |

miR‐191‐5p | Promoting ELOVL4‐mediated proliferation and migration |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐191‐5p‐mediated repression of ELOVL4 expression) |

[118] |

| Linc00174 | Up‐regulated | Fatty acid desaturation | Thymic epithelial tumors (TETs) |

Overall survival↓ Disease free survival↓ Distant‐metastasis↑ |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Lipogenesis↑ |

miR‐145‐5p | Expression of SCD5↑Lipogenesis and progression↑ |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐145‐5p‐mediated repression of SCD5 expression) |

[119] |

| UPAT | Up‐regulated | Fatty acid desaturation | Colorectal cancer (CRC) | N.A |

Viability↑ Tumorigenicity↑ |

UHRF1 | SCD1 and SPRY4 ‐mediated the survival and tumorigenicity↑ |

Binding with protein (Binding UHRF1 transcriptional factor to promote the expression of SPRY4 directly, SCD1 indirectly by interfering ubiquitination and degradation of UHRF1) |

[120] |

| SNHG16 | Up‐regulated | Fatty acid desaturation | Colorectal cancer (CRC) | Tumor stages↑ |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Lipid metabolism |

26 unique miRNA families | Expression of many lipid‐metabolism related genes↑ |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing half of 26 unique miRNA families‐mediated repression of SCD‐mediated lipid metabolism) |

[121] |

| KDM4A‐AS1 | Up‐regulated | Fatty acid desaturation | Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) | N.A |

Viability↓ Migration↓ |

N.A |

Stearoyl‐CoA desaturase↓ Fatty acid synthase expression↓ Reactive oxygen species ↑ Mitochondrial membrane potential ↓ |

KDM4AAS1‐encoded peptide inhibits the expression of SCD and FASN | [122] |

| Linc00460 | Up‐regulated | Fatty acid desaturation | Osteosarcoma (OS) |

Overall survival↓ Disease free survival↓ Distant metastasis↑ |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Invasion↑ |

miR‐1224‐5p | FADS1‐mediated proliferation and metastatic potential↑ |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐1224‐5p‐mediated repression of FADS1 expression) |

[123] |

| LINC01569 | Up‐regulated | Fatty acid desaturation | Hypopharyngeal carcinoma (HPC) | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Apoptosis↓ |

miR‐193a‐5p | FADS1‐mediated M2 macrophage polarization↑ |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐193a‐5p‐mediated repression of FADS1 expression) |

[124] |

| Circ_0000073 | Up‐regulated | Fatty acid desaturation | Osteosarcoma (OS) |

Clinical stage↑ Large tumor size↑ Metastasis↑ Overall survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Metastasis↑ |

miR‐1184 | FADS2‐mediated lipid synthesis↑ |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐1184‐mediated repression of FADS2 expression) |

[125] |

| ZFAS1 | Up‐regulated | Cholesterol biogenesis | Pancreatic carcinoma (PC) | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Invasion↑ Lipo‐metabolism↑ |

U2AF2 | HMGCR mRNA Stability↑ |

Binding with protein (Binding U2AF2 to maintains HMGCR mRNA Stabilization) |

[126] |

| AT102202 | Down‐regulated | Cholesterol biosynthesis | Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | N.A | N.A | N.A | HMGCR‐mediated cholesterol biosynthesis↑ | N.A | [127] |

| lnc030 | Up‐regulated | Cholesterol biosynthesis | Breast cancer stem cells (BCSCs) |

Lymph node metastasis↑ Pathological grade↑ Overall survival↑ |

Tumor cell stemness↑ Tumorigenesis↑ |

PCBP2 | Promoting SQLE‐mediated cholesterol synthesis to further active PI3K/Akt signaling |

Binding with protein (Cooperating with poly(rC) binding protein 2(PCBP2) to stabilize squalene epoxidase (SQLE) mRNA) |

[128] |

| Circ_0000182 | Up‐regulated | De novo fatty acid synthesis | Gastric cancer (GC) | Tumor size↑ | Cell proliferation↑ | miR‐579‐3p | SQLE‐mediated cholesterol synthesis↑ |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐579‐3p‐mediated repression of SQLE expression) |

[129] |

PS: N.A. Not Available.

Table 2.

The lncRNAs‐circRNAs in regulating lipid transport and fatty acid oxidation of cancer.

| Lipid metabolic lncRNAs | Status in tumor | Lipid metabolic process | Cancer types | Clinical association | Functional impact | Interactor | Target/effect | Mechanistic classification | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TINCR | Down‐regulated | Lipid transport | Colorectal cancer (CRC) | N.A | Tumor progression↑ | miR‐107 | Mediating CD36‐mediated proliferation and apoptosis |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐107‐mediated repression of CD36 expression) |

[130] |

| CASC19 | Up‐regulated | Lipid transport | Non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Metastasis↑ |

miR‐301b‐3p | Mediating LDLR‐mediated proliferation and metastasis |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐301b‐3p‐mediated repression of LDLR expression) |

[131] |

| BM450697 | Up‐regulated | Lipid transport | Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | N.A | Lipid uptake↓ | LDLR promoter | Mediating LDLR‐mediated LDL Uptake |

DNA binding (Directly interacting with the DNA of the LDLR promoter to block interactions with Pol II and possibly SREBP1a at the promoter of LDLR) |

[132] |

| CircRNA_101 093 (cir93) | Up‐regulated | Lipid transport | Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) |

Ferroptosis resistance↑ Overall survival↓ |

Lipid peroxidation↓ Sensitive to ferroptosis↓ |

FABP3 | Promoting FABP3‐mediated desensitizing ferroptosis |

Binding with protein (Interacted with and increased FABP3, which transported AA to react with taurine in form of NAT) |

[133] |

| Circ_ABCB10 | Up‐regulated | Lipid transport | Glioma | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Invasion↑ |

miR‐620 | Promoting FABP5‐mediated the proliferation and migration |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐620‐mediated repression of FABP5 expression) |

[134] |

| LNMICC | Up‐regulated | Lipid transport | Cervical cancer (CC) |

Tumor size↑ Stromal invasion↑ Lymph node metastasis↑ Recurrence↑ Overall survival↓ Disease free survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Lipogenesis↑ Metastasis↑ Lymphangiogenesis↑ |

NPM1 | Promoting FABP5‐mediated lipogenesis and lymph node metastasis |

Binding with protein (Directly binding transcriptional factor‐NPM1 to the promoter of the FABP5 gene, which mediated reprogramming of FA metabolism) |

[135] |

| LncDBET | Up‐regulated | Lipid transport | Bladder cancer (BCa) | Tumor volume and weight↑ |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Viability↑ Apoptosis↓ |

FABP5 |

Activating FABP5‐mediated PPAR pathway |

Binding with protein (METTL14 upregulates lncDBET by m6A modification, thereby activating the PPAR signaling pathway through direct interaction with FABP5) |

[137] |

| CCAT1 | Up‐regulated | Lipid transport | Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) |

Histology grade↑ Overall survival↓ Disease free survival↓ |

Lipogenesis↑ Proliferation↑ Angiogenesis↑ |

FABP5, USP49, RAPTOR |

Activating PPAR‐RXR transcriptional complex and mTOR pathway |

Binding with protein (Binding FABP5 to translocate FA into nuclear to facilitate PPAR/RXR transcriptional complex, and binding USP49 to regulate FKBP51‐mediated AKT phosphorylation, but also binds RAPTOR to stabilize PI3K pathway) |

[138] |

| FAM201A | Down‐regulated | Lipid transport | Neuroblastoma (NB) | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Invasion↑ |

FABP5 | Expression of FABP5↑ FABP5‐medicated MAPK signaling pathway↑ |

Encoding peptides and binding with protein (Encoding peptides‐NBASP reduced the expression of FABP5 via the ubiquitin proteasome pathway) |

[136] |

| Circ_ZFR | Up‐regulated | Lipid transport | Breast cancer (BC) | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Invasion↑ EMT↑ |

miR‐223‐3p | Promoting FABP7‐mediated tumor progression |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐223‐3p‐mediated repression of FABP7 expression) |

[140] |

| CircPUM1 | Up‐regulated | Lipid transport | Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Invasion↑ |

miR‐340‐5p | Promoting FABP7‐mediated tumor proliferation |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐340‐5p‐mediated repression of FABP7 expression) |

[139] |

| AGAP2‐AS1 | Up‐regulated | Fatty acid oxidation (FAO) | MSC‐cocultured Breast cancer (BC) | Predictor of trastuzumab response |

Tumor cell stemness↑ Trastuzumab resistance↑ |

HuR miR‐15a‐5p |

Promote CPT1‐mediated FAO to facilitated the stemness and trastuzumab resistance |

Binding with protein (Binding HuR protein to enhance protein stability of CPT1) Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐15a‐5p‐mediated repression of CPT1 expression) |

[141] |

| lncHCP5 | Up‐regulated | Fatty acid oxidation (FAO) | Gastric cancer (GC) | N.A | Tumor cell stemness↑ Chemoresistance↑ | miR‐3619‐5p |

Regulating PGC1α‐CPT1‐mediated FAO to facilitate stemness and chemo‐resistance |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐3619‐5p‐mediated repression of PPARGC1A/ PGC1α expression and facilitating PGC1α interacted with CEBPB to induce CPT1 transcription) |

[142] |

| Circ_0024107 | Up‐regulated | Fatty acid oxidation (FAO) | Gastric cancer (GC) |

TNM stages↑ Lymphatic metastasis↑ Overall survival↓ |

Migration↑ Invasion↑ |

miR‐5572 miR‐6855‐5p |

CPT1A‐mediated fatty acid oxidation↑ |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐5572 and miR‐6855‐5p‐mediated repression of CPT1A expression) |

[144] |

| MACC1‐AS1 | Up‐regulated | Fatty acid oxidation (FAO) | Gastric cancer (GC) | N.A |

Tumor cell stemness↑ Chemoresistance↑ Proliferation↑ |

miR‐145‐5p | Increasing the expression of FAO enzyme to regulate stemness and chemoresistance |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐145‐5p‐mediated repression of stemness genes and FAO enzyme expression levels) |

[143] |

| SOCS2‐AS1 | Up‐regulated | Fatty acid oxidation (FAO) | Thyroid cancer (TC) | Overall survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Progression↑ |

P53 |

P53 protein degradation↑ Fatty acid oxidation↑ |

Binding with protein (Binding P53 to regulate its protein turnover) |

[145] |

PS: N.A. Not Available.

Table 3.

The lncRNAs‐circRNAs in regulating the esterification of lipids and the metabolism of lipid droplets (LDs) in cancer.

| Lipid metabolic lncRNAs | Status in tumor | Lipid metabolic process | Cancer types | Clinical association | Functional impact | Interactor | Target/effect | Mechanistic classification | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HULC | Up‐regulated | Long‐chain fatty acids esterification | Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Lipid metabolism↑ |

miR‐9 | Regulating HCC growth through ACSL1‐mediated lipogenesis |

Epigenetic modification of miRNAs gene (Releasing miR‐9‐mediated repression of ACSL1 expression through inducing methylation of CpG islands in the promoter of miR‐9) |

[ 148 ] |

| CircPDHX | Up‐regulated | Long‐chain fatty acids esterification | Prostate cancer (PCa) | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Fatty acid metabolism↑ |

miR‐497‐5p | Promoting ACSL1‐mediated proliferation and migration |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐497‐5p‐mediated repression of ACSL1 expression) |

[ 150 ] |

| SNHG7 | Up‐regulated | Long‐chain fatty acids esterification | Thyroid cancer (TC) | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ |

miR‐449a | Promoting ACSL1‐mediated proliferation and migration |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐449a‐mediated repression of ACSL1 expression) |

[ 151 ] |

| PRADX | Up‐regulated | Long‐chain fatty acids esterification | Glioblastoma (GBM) | Poor prognosis↑ |

Energy metabolism↑ Tumorigenesis↑ |

EZH2 | Promoting ACSL1‐mediated basal respiration, proton leak and ATP production |

Binding with protein (Binding EZH2 to recruit H3K27me3 of BLCAP promoter and further to activate the phosphorylation of STAT3 and its downstream genes’ expression, including ACSL1) |

[ 149 ] |

| CBSLR | Up‐regulated | Long‐chain fatty acids esterification | Gastric cancer (GC) |

TNM stage↑ Overall survival↓ Disease free survival↓ |

Ferroptosis↓ Chemoresistance↑ |

YTHDF2 | Inhibiting ACSL4‐mediated ferroptosis under hypoxia |

Binding with protein (Binding YTHDF2 to form a CBSLR/ YTHDF2/CBS signaling axis to decrease the stability of CBS mRNA, which further reduces the methylation of the ACSL4 protein, leading to protein polyubiquitination and degradation of ACSL4.) |

[ 155 ] |

| CircLMO1 | Down‐regulated | Long‐chain fatty acids esterification | Cervical cancer | FIGO staging↑ |

Proliferation↑ Metastasis↑ |

miR‐4192 | Promoting ACSL4‐mediated ferroptosis |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐4192‐mediated repression of ACSL4 expression) |

[ 153 ] |

| CircSCN8A | Down‐regulated | Long‐chain fatty acids esterification | Non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC |

Aggressive clinicopathological characteristics↑ Poor prognosis↑ |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Invasion↑ EMT↑ |

miR‐1290 | Promoting ACSL4‐mediated ferroptosis |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐1290‐mediated repression of ACSL4 expression) |

[ 154 ] |

| NEAT1 | Up‐regulated | Long‐chain fatty acids esterification | Prostate cancer (PCa) | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Invasion↑ Docetaxel resistance↑ |

miR‐34a‐5p miR‐204‐5p |

Regulating ACSL4‐mediated docetaxel resistance |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐34a‐5p and miR‐204‐5p‐mediated repression of ACSL4 expression) |

[ 152 ] |

| CircLDLR (circ_0 0 06877) | Up‐regulated | Cholesterol esterification | Colorectal cancer (CRC) | Poor prognosis↑ |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Invasion↑ Cholesterol levels↑ |

miR‐30a‐3p | Promoting SOAT1‐mediated cell growth, migration, invasion and cholesterol levels increase |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐30a‐3p‐mediated repression of SOAT1 expression) |

[ 156 ] |

| CircRPL23A | Down‐regulated | Cholesterol esterification | Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Invasion↑ Apoptosis↓ |

miR‐1233 | Inhibiting ACAT2‐mediated suppressing cell cycle progression, proliferation, migration and invasion |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐1233‐mediated repression of ACAT2 expression) |

[ 157 ] |

| Linc01410 | Up‐regulated | Lipid Drops formation | Cervical cancer | Poor overall survival↑ |

Lipid Drop accumulation↑ Invasion↑ Migration↑ |

miR‐532‐5p | Increasing FASN and PLIN2 expression to facilitate the LD accumulation |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐532‐5p‐mediated repression of FASN expression) |

[ 158 ] |

| SPRY4‐IT1 | Up‐regulated | Lipid Drops formation | Melanoma | N.A |

Lipin 2‐mediated lipid metabolism↑ Apoptosis↓ |

lipin2 |

Accumulation of lipin2 protein↓ Expression of DGAT2↓ |

Binding with protein (Binding lipin2 to decrease its accumulation) |

[ 159 ] |

| NEAT1 | Up‐regulated | Lipolysis | Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) |

Tumor size↑ DAG and FFA levels↑ Overall survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Lipolysis↑ |

miR‐124‐3p |

ATGL‐mediated Lipolysis↑ FAO↑ |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐124‐3p‐mediated repression of ATGL expression) |

[ 160 ] |

| NEAT1 | Up‐regulated | Lipolysis | Ovarian cancer | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Invasion↑ |

Let‐7 g | Promoting ATGL‐mediated lipolysis and tumor progression |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing let‐7 g‐mediated repression of MEST expression) |

[ 197 ] |

| Circ‐cMras | Down‐regulated | Lipolysis | Lung adenocarcinoma (LAC) | N.A |

Progression↑ Tumorigenesis↑ |

N.A | Modulating ABHD5/ATGL axis mediated in the proliferation and aggression |

Signaling pathway (Regulating ABHD5 possibly via NF‐κB signaling pathway) |

[ 161 ] |

| CircRIC8B | Up‐regulated | Lipolysis | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) |

Advanced progression ↑ Poor prognosis↑ |

Proliferation↑ Lipid accumulation↑ |

miR‐199b‐5p | Promoting LPL ‐mediated lipid metabolism alteration and the progression |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐199b‐5p‐mediated repression of LPL expression) |

[ 162 ] |

| NMRAL2P | Down‐regulated | Lipolysis | Gastric cancer (GC) | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Invasion↑ Cell cycle progression↑ Apoptosis↓ |

N.A | Inhibiting ACOT7‐mediated hydrolysis of fatty acyl‐CoAs |

Epigenetic modification (Down‐regulation of ACOT7 through inducing methylation of CpG islands in its promoter by interacting DNMT3b) |

[ 163 ] |

| COL18A1‐AS1 | Down‐regulated | lipid browning | Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) |

Overall survival↓ Tumor grade and stage↑ |

Tumor progression↑ Lipid browning and consumption↑ |

miR‐1286 | Increasing the expression of KLF12 to regulate UCP1‐mediated lipid browning |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐1286‐mediated repression of KLF12 expression) |

[ 164 ] |

PS: N.A. Not Available.

Table 4.

The lncRNAs‐circRNAs in regulating lipid metabolic transcriptional factors, oncogenic signaling pathways of lipid metabolism in cancer.

| Lipid metabolic lncRNAs&circRNA | Status in tumor | Lipid metabolic process | Cancer types | Clinical association | Functional impact | Interactor | Target/effect | Mechanistic classification | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linc02570 | Up‐regulated | Transcriptional factors | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) |

Histology grade↑ Disease free survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Invasion↑ Viability↑ Lipogenesis↑ |

miR‐4649‐3p | Increasing SREBP1 and FASN expression to facilitate lipid metabolism |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐4649‐3p‐mediated repression of SREBP1 and FASN expression) |

[165] |

| PCA3 | Up‐regulated | Transcriptional factors | Prostate cancer (PCa) | N.A |

Proliferations↑ Lipid metabolic disorders↑ |

miR‐132‐3p | Increasing the expression of SREBP1 to regulate the cellular triglyceride and cholesterol levels |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐132‐3P‐mediated repression of SREBP1 expression) |

[166] |

| SNHG16 | Up‐regulated | Transcriptional factors | Pancreatic carcinoma (PC) | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Invasion↑ Lipid metabolism↑ |

miR‐195 | Increasing the expression of SREBP2 to regulate lipogenesis and progression |

Sequestration of miRNAs (Releasing miR‐195‐mediated repression of SREBP2 expression) |

[167] |

| ZFAS1 | Up‐regulated | Transcriptional factors | Colorectal cancer (CRC) |

Tumor size↑ Invasive status↑ microsatellite stability↓ |

Proliferation↑ Enrichment of lipids↑ Invasion↑ |

PABP2 | Increase SREBP1, FASN, and SCD1 expression to facilitate the accumulation of lipids |

Binding with protein (Cooperating with polyadenylate binding protein 2 to maintain SREBP1 mRNA stability) |

[171] |

| Linc01138 | Up‐regulated | Transcriptional factors | Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) |

TNM stage↑ Overall survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Lipid metabolism↑ |

PRMT5 | Regulating tumor growth through SREBP1‐mediated lipid desaturation |

Binding with protein ( Binding PRMT5 protein to enhance protein stability of SREBP1) |

[172] |

| CCAT1 | Up‐regulated | Transcriptional factors | Osteosarcoma (OS) | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Warburg effects↑ Lipogenesis↑ |

PKM2 | Upregulating the phosphorylation of SREBP2 to promote lipogenesis |

Binding with protein (Binding PKM2 to phosphorylate SREBP2 at T610 which affected the stability of SPREBP2) |

[173] |

| CircPRKAA1 | Up‐regulated | Transcriptional factors | Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | N.A | Proliferation↑ Clonogenicity↑ | Ku80/Ku70 | Promoting mSREBP1‐mediated increasing fatty acid synthesis to promote cancer growth |

Protein and DNA binding (Stabilizing mSREBP‐1 and enhancing its transcriptional activity through interaction with Ku proteins and selectively binding to the promoters of the ACC1, CLY, SCD1, and FASN genes to recruit mSREBP‐1) |

[174] |

| HOXB‐AS3 | Up‐regulated | Transcriptional factors | Endometrial cancer (EC) | Diagnostic indicator |

Proliferation↑ Invasion↑ Apoptosis↓ |

PTBP1 |

Expression of SREBP1 and its downstream SCD1 and phosphorylated ACLY Ser455↑ |

Binding with protein (Binding to PTBP1 to form an RNA protein complex, promoting the expression of SREBP1) |

[168] |

| CircMyc (hsa_circ_00 85533) | Up‐regulated | Transcriptional factors | Breast cancer (BC) |

Tumor volume↑ Clinical stages↑ Lymphatic metastasis↑ |

Proliferation↑ Invasion↑ |

HuR Myc |

SREBP1mRNA stability and transcription ↑ SREBP1‐mediated lipogenesis↑ |

Binding with protein (Binding HuR to regulate SREBP1 mRNA stability; Binding Myc to facilitate transcription of SREBP1) |

[169] |

| CircREOS | Down‐regulated | Transcriptional factors | Osteosarcoma (OS) | N.A |

Proliferation↓ Invasion↓ |

HuR | MYC‐medicated FASN activation↓ |

Binding with protein (Binding HuR to degrade MYC mRNA, further reducing ACC1 activation) |

[170] |

| LINC00326 | Down‐regulated | Transcriptional factors | Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | N.A | Proliferation↓ | CCT3 |

EGR1, CYR61 and GLIPR1‐mediated lipogenesis↓ lipolysis↑ |

Binding with protein (Binding CCT3 to impede CCT3's confinement of CREM, CREB and ATF) |

[176] |

| CircINSIG1 | Up‐regulated | Transcriptional factors | Colorectal cancer (CRC) |

TNM stages↑ Clinical stages↑ Overall survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Metastasis↑ |

INSIG1 | Cholesterol biosynthesis↑ |

Encoding peptides and binding with protein (Encoding peptides‐ circINSIG1‐121 to promote INSIG1 degradation via recruiting CUL5‐ASB6 complex, further inducing nSREBP2 increase) |

[175] |

| DNAJC3‐AS1 | Up‐regulated | Signaling Pathways | Colorectal cancer (CRC) |

Local invasion↑ Clinical stages↑ Overall survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Invasion↑ Lipid accumulation↑ |

N.A | Regulating ACC1 and FASN‐mediated the progression |

Modulating signaling pathways (Regulating the Expression of ACC1/FASN Via EGFR/PI3K/AKT/NF‐Kb/SREBP1 Signaling Pathway) |

[177] |

| HAGLROS | Up‐regulated | Signaling Pathways | Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) |

Tumor stage↑ Differentiation↓ Overall survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Lipid accumulation↑ |

mTOR signaling pathway | Activation of mTOR pathway can increase lipid metabolism‐related proteins expression and PPARγ | N.A | [178] |

| Linc01468 | Up‐regulated | Signaling Pathways | Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) associated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) |

Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C), triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), cirrhosis levels↑ Tumor size↑ Tumor stage↑ TNM stage↑ Microvascular invasion↑ Overall survival↓ |

Chemoresistance↑ Tumorigenesis↑ |

SHIP2 | Activation of Akt/mTOR signaling pathway mediated increase of intracellular TG and TC |

Binding with protein (Binding SHIP2 protein to induce CUL4A by promoting the ubiquitinated degradation of SHIP2) |

[179] |

| lncARSR | Up‐regulated | Signaling Pathways | Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) | N.A |

Proliferation↑ Migration↑ Lipid accumulation↑ |

YAP1 |

Activating IRS2/ AKT pathway to increase adipogenesis related proteins (FASN, SCD1 and GPA) and PPARγ |

Binding with protein (Binding YAP1 protein to maintain its nuclear translocation to activate IRS2/ AKT pathway) |

[180] |

| NEAT1 | Up‐regulated | Signaling Pathways | Gastric cancer (GC) | Overall survival↓ | Lymphatic metastasis↑ | TRIM25 |

Regulating RPRD1B/c‐Jun/c‐Fos/ SREBP1 axis‐mediated lipogenesis and lymph node metastasis |

Binding with protein (Binding TRIM25 to reduce the degradation of RPRD1B protein, which transcriptionally upregulates c‐Jun/c‐Fos and activate the c‐Jun/c‐Fos/SREBP1 axis) |

[181] |

| lncHR1 | Down‐regulated | Signaling Pathways | Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | N.A | N.A | N.A | SREBP‐1c‐mediated the fatty acid synthesis↑ |

Modulating signaling pathways (Suppressing the phosphorylation of DK1/AKT/FoxO1 axis to weaken the combinatorial capacity of LXRα/RXR binding to LXREs to decrease the expression of SREBP‐1c) |

[182] |

| SLC16A1‐AS1 | Up‐regulated | Signaling Pathways | Bladder cancer (BCa) | N.A |

Invasion↑ Metabolic reprogramming (increasing aerobic glycolysis, mitochondrial respiration and FAO) ↑ |

E2F1 | Regulating PPARA‐mediated FAO to promote cancer invasiveness |

Binding with protein (Binding E2F1 transcriptional factor to promote the expression of PPARA, a key mediator of fatty acid β‐oxidation) |

[183] |

| Linc00924 | Up‐regulated | Signaling Pathways | Peritoneal metastasis associated gastric cancer (GC) |

Lymph node status↑ TNM stage↑ Overall survival↓ Disease free survival↓ |

Invasion↑ Metastasis↑ |

hnRNPC | Activation of p38/PPARα signaling pathway mediated FAO and FA uptake |

Binding with protein (Binding hnRNPC to regulate the alternative splicing of Mnk2 pre‐mRNA, thereby decreasing Mnk2a splicing and activating the p38 MAPK/PPARα signaling pathway) |

[184] |

| CircACC1 (circ001391) | Up‐regulated | Signaling Pathways | Colorectal cancer (CRC) | N.A |

FAO↑ Glycolysis↑ |

AMPK β and γ Subunits |

Promoting AMPK‐mediated in inhibition of fatty acid synthesis (FAS) and stimulation of FAO via the phosphorylation of ACC1 and ACC‐2, respectively. |

Binding with protein (Binding AMPK β and γ Subunits to facilitate AMPK Holoenzyme assembly, stability, and activity) |

[185] |

| EcircCUX1 (circ30402) | Up‐regulated | Signaling Pathways | Neuroblastoma (NB) |

Poor differentiation↑ Higher mitosis karyorrhexis index↑ Advanced international neuroblastoma staging system (INSS) stages↑ Overall survival↓ |

Proliferation↑ Tumorigenesis↑ Aggressiveness↑ Fatty acid oxidation↑ Mitochondrial activity↑ |

ZRF1 BRD4 |

Promoting ALDH3A1, NDUFA1, and NDUFAF5‐mediated lipid metabolic reprogramming and mitochondrial complex I activity |

Encoding peptides and Protein biding (p113‐encoded by circCUX1, interacts with ZRF1 and BRD4 to form a transcriptional regulatory complex, facilitating ALDH3A1, NDUFA1, and NDUFAF5 transcription) |

[186] |

PS: N.A. Not Available.

4.1. The lncRNAs‐circRNAs in Regulating de Novo Synthesis of Fatty Acid and Cholesterol of Cancer

In the initial step of de novo lipogenesis, ACLY is responsible for acetyl‐CoA synthesis, which provides the primitive fuels for both fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis pathways (Figure 4 and Table 1). A novel lipid metabolic related lncRNA, TINCR, was identified to be significantly overexpressed in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), and can promote proliferation, metastasis and cisplatin resistance of NPC by affecting ACLY‐mediated de novo lipid biosynthesis. Mechanistically, TINCR interacts with ACLY directly and inhibited its ubiquitin degradation to increase cellular total acetyl‐CoA levels for lipid synthesis and histone acetylation.[ 103 ] Moreover, lncRNA FLJ22763, which is downregulated in gastric cancer (GC), negatively regulates the mRNA and protein expression of ACLY to suppress the proliferation, migration, and invasion of GC cells as a tumor suppressor gene.[ 104 ]

As the acetyl‐CoA is increasingly synthesized, it is carboxylated to form malonyl‐CoA by ACC1, which is a rate‐limiting enzyme in the de novo synthesis of fatty acid. The lipid‐metabolic related lncRNAs and circRNAs in cancers have been found to regulate the expression of ACC1 mainly through modulating its mRNA transcription and activation of protein phosphorylation (Figure 4). For instance, circCAPRIN1 is upregulated in colorectal cancer (CRC) as an oncogenic regulator. It can directly bind transcriptional factor STAT2 to facilitate the transcription of ACC1, which further promotes adipogenesis, proliferation, metastasis, and EMT of CRC.[ 105 ] Additionally, lncRNA CTD‐2245E15.3, upregulated in non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), promotes fatty acid biosynthesis of cancer cells mainly by interacting with ACC1 to promote its activity by reducing phosphorylation of an inhibitory site of ACC1.[ 106 ] Another lncRNA, TSPEAR‐AS2, is identified to regulate ACC1 and FASN‐mediated fatty acid synthesis of CRC through Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) and the construction of a prognostic signature with a ceRNA network, which is closely associated with the overall survival of CRC. However, the detailed mechanisms of how TSPEAR‐AS2 regulates ACC1 and FASN expression require to be further explored.[ 107 ]

FASN is responsible for the consecutive condensation of malonyl‐CoA and acetyl‐CoA to form long‐chain saturated fatty acids, mostly 16‐carbon palmitate. Recently, the dysregulated lipidmetabolic‐related lncRNAs and circRNAs in cancers have been demonstrated to play key roles in regulating FASN expression by the ceRNA mechanism (Figure 4). For instance, lncRNA SNHG25, upregulated in endometrial cancer, was identified to regulate FASN expression by inhibiting miR‐497‐5p‐mediated repression.[ 108 ] Other lipid‐metabolic related lncRNAs and circRNAs of cancers have also been identified to regulate FASN expression in the same ways, such as the PVT1/miR‐195/FASN axis in osteosarcoma (OS),[ 109 ] the circFARSA/miR‐330‐5p and miR‐326/FASN axis in NSCLC,[ 110 ] the circWHSC1/miR‐195‐5p/FASN and circZFAND6/ miR‐647/FASN axis in breast cancer (BC),[ 111 , 112 ] and the circ_00 18 909/miR‐545‐3p/FASN axis in pancreatic carcinoma (PC).[ 113 ] Even FASN mRNA transportation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm has been shown to be mediated by circMBOAT2, which facilitates the lipid metabolic profile and redox homeostasis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC).[ 114 ] Additionally, lncRNA HOTAIR and HAGLR, overexpressed in NSCLC and NPC, respectively, have been shown to regulate FASN expression and be involved in FASN‐mediated lipogenesis, proliferation, and invasion of cancer. However, the mechanisms of these two lncRNAs in regulating FASN expression need to be further explored in detail.[ 115 , 116 ] Recently, a novel lncRNA FASRL has been identified to promote the proliferation and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) via directly binding ACACA (acetyl‐CoA carboxylase 1) to facilitate de novo synthesis of fatty acid.[ 117 ]

To replenish the cellular pool of non‐essential FAs, such as monounsaturated 18‐carbon FA oleate (18:1) or 16‐carbon palmitoleate (16:1), de novo palmitate needs to undergo further elongation by ELOVL and SCD or fatty acid desaturases (FADS). The dysregulated lipid‐metabolic related lncRNAs and circRNAs in cancers can also play crucial roles in regulating elongation and desaturation of de novo fatty acids (Figure 4). For the elongation of de novo fatty acids, circ_0 0 08078 was identified to be downregulated in esophagus cancer (EC), which promoted ELOVL4 expression via miR‐191‐5p, and regulated the proliferation, tube formation, migration and invasion of EC.[ 118 ] For the desaturation of de novo fatty acids, these lipid‐metabolic related lncRNAs and circRNAs can involve the SCD‐mediated desaturation of de novo fatty acids. For instance, a novel linc00174 has been identified to modulate the SCD5‐meditated lipid production by absorbing miR‐145‐5p in thymic epithelial tumors (TETs).[ 119 ] Moreover, lncRNA UPAT can regulate SCD1 indirectly to improve the tumorigenicity of CRC cells by interacting with and interfering with UHRF1's ubiquitination.[ 120 ] Additionally, through RNA sequencing and mRNA/ncRNA profiling screen, lncRNA SNHG16 is discovered to be significantly upregulated in early phase of CRC and holds AGO/miRNA target sites with several miRNA families, half of which targeted the 3′‐UTR of SCD with high confidence.[ 121 ] Recently, a novel peptide encoded by KDM4A‐AS1 has been shown to repress the expression of SCD and other fatty acid synthase to weaken the viability and migratory capacity of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), in result of increasing the reactive oxygen species level and breaking mitochondrial redox homeostasis.[ 122 ] On the other hand, some lipid‐metabolic related lncRNAs and circRNAs in cancer can also regulate the FADS‐mediated desaturation of de novo fatty acids, apart from SCD. For example, linc00460 has been identified to be upregulated in osteosarcoma (OS), which functions as a sponge of miR‐1224‐5p to promote OS progression by upregulating FADS1 expression.[ 123 ] LINC01569 has been identified to enrich in hypopharyngeal carcinoma associated macrophages to promote its M2 polarization via releasing miR‐193a‐5p‐mediated repression of FADS1 expression. These polarized M2 macrophages further accelerate the progression of hypopharyngeal carcinoma.[ 124 ] Recently, Circ_0000073 has been shown to regulate the lipid synthesis of osteosarcoma in the same way of promoting the expression of FADS2 as a sponge of miR‐1184.[ 125 ]

In the process of de novo cholesterol biosynthesis, HMGCR is one of the rate‐limiting enzymes that can be regulated by dysregulated lipid‐metabolic related lncRNAs and circRNAs in cancers (Figure 4). For instance, when overexpressed in pancreatic carcinoma (PC), lncRNA ZFAS1 can stabilize and increase HMGCR mRNA to promote lipid accumulation in PC by binding to U2AF2, one component of spliceosomes.[ 126 ] Moreover, a bioinformatic analysis of the roles of lncRNA in facilitating epigallocatechin‑3‑gallate (EGCG) on cholesterol metabolism identified lncRNA AT102202 with potential to target HMGCR mRNA for regulating cholesterol metabolism of HepG2 cells. However, its mechanism needs to be further explored in the future.[ 127 ] Additionally, squalene epoxidase is another key rate‐limiting enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis. Recently, lnc030 has been shown to promote cholesterol synthesis in breast cancer stem cells (BCSCs) by cooperating with poly(rC) binding protein 2 (PCBP2) to stabilize SQLE mRNA, which leads to increased cholesterol production. This increased cholesterol, in turn, activates the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and promotes the stemness of BCSCs.[ 128 ] Circ_0000182 has been found to facilitate the proliferation and cholesterol synthesis in cholesterol synthesis in via releasing miR‐579‐3p‐mediated repression of SQLE expression.[ 129 ]

4.2. The lncRNAs‐circRNAs in Regulating Lipid Transport and Fatty Acid Oxidation of Cancer

Exogenous lipids enter into the cancer cells mainly through two known lipid transporters in the plasma membrane, CD36 or LDLR. The dysregulated lipid‐metabolic related lncRNAs and circRNAs in cancers can modulate extracellular lipids uptake by regulating these transporters (Figure 5 and Table 2). For instance, lncRNA TINCR has been found to be downregulated in CRC cells, but it can relieve the miR‐107‐mediated repression of CD36 expression, promoting apoptosis and inhibiting the proliferation of CRC cells.[ 130 ] Similarly, overexpressed lncRNA CASC19 in NSCLC can positively regulate LDLR by targeting miR‐301b‐3p to facilitate proliferation and metastasis of NSCLC cells. Additionally, some lipid‐metabolic related lncRNAs and circRNAs in cancer can modulate LDLR expression epigenetically.[ 131 ] For example, as an antisense RNA that overlaps the promoter of the LDLR gene, lncRNA BM450697 can decrease the expression of LDLR by inhibiting interaction between RNA polymerase II (Pol II) or transcription factor SREBP1a and the promoter of LDLR in HCC.[ 132 ]

The role of fatty acid‐binding proteins (FABPs) in lipid metabolism is to transport newly synthesized or extracellular fatty acids for energy supply and storage. The isoforms of FABPs have been upregulated to facilitate viability, proliferation, migration and metastasis in various cancers, in which the dysregulated lipid‐metabolic related lncRNAs and circRNAs in cancer can also play significantly important roles (Figure 5). For instance, circRNA_101 093, derived from lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) patients’ plasma exosome, has been identified to interact and increase FABP3, which then transports arachidonic acid and desensitized LUAD cells to ferroptosis.[ 133 ] Moreover, the dysregulated lipid‐metabolic related lncRNAs and circRNAs can regulate the expression of FABP5 in various cancer with different mechanisms: On the one hand, circ‐ABCB10 can promote FABP5‐mediated the proliferation and migration of glioma by absorbing miR‐620.[ 134 ] Moreover, LncLNMICC can bind transcriptional factor‐NPM1 to the promoter of the FABP5 gene to facilitate FABP5‐mediated lipogenesis, lymph node metastasis of cervical cancer (CC).[ 135 ] Neuroblastoma‐associated small protein (NBASP) encoded by lncRNA FAM201A has recently been found to inhibit the expression of FABP5 via the ubiquitin proteasome pathway in neuroblastoma, which further repressed the progression of neuroblastoma by inactivating the MAPK pathway mediated by downregulating FABP5.[ 136 ] On the other hand, m6A modified lncDBET in bladder cancer (BCa) and lncRNA CCAT1 in LUAD can both interact with FABP5 directly to activate the PPAR signaling pathway or PPAR‐RXR transcriptional complex in order to promote lipogenesis, proliferation and migration of cancers.[ 137 , 138 ] Additionally, circ_ZFR in breast cancer (BC) and circPUM1 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) can both absorb miRNAs (miR‐223‐3p and miR‐340‐5p, respectively) to regulate FABP7‐mediated proliferation and progression of these cancer cells.[ 139 , 140 ]

FAO or β‐oxidation in mitochondria and peroxisome is the major pathway for degradation of fatty acids and production of ATP and NADPH, with CPT1 being one of the most important regulatory targets. The dysregulated lipid‐metabolic related lncRNAs and circRNAs in cancer can support tumor progression, stem cell property and drug resistance by modulating this carnitine palmitoyltransferase via various regulatory strategies (Figure 5). For instance, in MSC (mesenchymal stem cell)‐cultured breast cancer cells, overexpressed lncRNA AGAP2‐AS1 not only binds to the CPT1 mRNA to increase its stability and expression by interacting with HuR (an RNA binding protein), but also serves as a sponge to release the miR‐15a‐5p‐mediated repression of CPT1 expression.[ 141 ] Similarly, lncRNA HCP5 is also induced in MSC‐cocultured gastric cancer cells, where it can upregulate the expression of PPARGC1A to increase the formation of PGC1α/CEBPB complex by sequestering miR‐3619‐5p. The PGC1α/CEBPB complex can further promote the expression of CPT1 transcriptionally.[ 142 ] Additionally, lncRNA MACC1‐AS1 has been identified to be elevated in MSC‐cultured gastric cancer cells, which promotes the expression of CPT1 directly through the MACC‐AS1/ miR‐145‐5p/CPT1 axis possibly.[ 143 ] In a similar way, circ_00 24 107, also enriched in MSC‐cultured gastric cancer cells, has been identified to mediate lymphatic metastasis of gastric cancer, in which circ_00 24 107 can promote FAO reprogramming by modulating the circ_00 24 107/ miR‑5572 and miR‑6855‑5p/CPT1A axis.[ 144 ] On the other hand, as a tumor suppressor, P53 has been recently shown to be modulated by lncRNA SOCS2‐AS1 to enhance FAO and proliferation of papillary thyroid carcinoma. SOCS2‐AS1 binds to P53 directly and facilitates its degradation, further stimulating FAO‐mediated cell proliferation.[ 145 ]

4.3. The lncRNAs‐CircRNAs in Regulating Lipid Esterification and Lipid Droplet Metabolism of Cancer

The metabolism of long‐chain fatty acids is dependent on their activation by esterification, which forms fatty acyl‐CoA esters from free long‐chain fatty acids catalyzed by long‐chain acyl‐coenzyme A synthetases (ACSLs) family. The ACSLs isoforms mainly involves both anabolic (lipogenesis) and catabolic pathways (fatty acid oxidation and lipolysis), among which ACSL1 and ACSL4 are the most extensively studied in the lipid metabolic reprogramming of cancer.[ 146 , 147 ] The lipid‐metabolic related lncRNAs and circRNAs in cancers have also been discovered to play roles in the regulation of ACSL1 and ACSL4 expressions (Figure 5 and Table 3). For instance, lncRNA HULC was identified to modulate the lipid metabolic programming of HCC. The mechanism in detail is that HULC released the miR‐9‐mediated repression of PPARA by modulating the methylation of miR‐9 promoter. The increased expression of PPARA further led to the transcriptional activation of ACSL1, resulting in triglyceride and cholesterol formation in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).[ 148 ] Moreover, highly‐expressed lncRNA PRADX activated the phosphorylation of STAT3 to promote the expression of ACSL1 by suppressing the expression of BLCAP (a tumor suppressor gene) in mesenchymal glioblastoma (GBM).[ 149 ] The upregulated ACSL1 further played roles in basal respiration, proton leak, and ATP production to promote energy metabolism and tumorigenesis of mesenchymal GBM cells. Additionally, the lncRNA SNHG7/miR‐449a/ACSL1 axis in thyroid cancer and the circPDHX/miR‐497‐5p/ACSL1 axis in prostate cancer have been identified to promote cancer cells’ proliferation and migration.[ 150 , 151 ]