To the Editors:

HIV-infected individuals are living longer, more productive lives. HIV-affected individuals and couples experience personal and social desires to reproduce for all the same reasons as uninfected individuals and couples,1 and thus require safe reproductive options. HIV prevention interventions often do not consider the childbearing desires of HIV-affected individuals or couples, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Failure to assist women with desired fertility can contribute to continued HIV transmission and must be addressed within national elimination of mother-to-child transmission (eMTCT) strategies.

A human rights perspective suggests that HIV-affected couples* should have the same ability to choose if and when to have children as HIV-unaffected couples, including access to pre-pregnancy counseling, contraceptives, and, when needed, abortion services. This holistic view includes assistance in mitigating HIV transmission risk when children are desired. In high-income countries, HIV-affected individuals and couples have access to an array of options: (1) treatment of the HIV-infected partner as prevention of transmission to the uninfected partner in conjunction with timed condomless intercourse2**; (2) preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for the uninfected partner3; (3) assisted reproductive services, including timed vaginal insemination and sperm washing with intrauterine insemination or in-vitro fertilization4,5; (4) sperm donation; and (5) adoption.1,6

In contrast, access to methods of becoming pregnant in LMICs are limited by cost, availability, and sometimes a lack of appreciation by policymakers of the desires and rights of HIV-affected individuals/couples to have children safely. Simple fertility methods may not be discussed as a component of routine HIV care and treatment counseling due to a lack of awareness or knowledge about their safety, affordability, or efficacy.7 To enhance the armamentarium of HIV prevention and reproductive services to achieve zero perinatal and sexual transmission, “safer conception”, and fertility services should be integrated into existing PMTCT strategies.

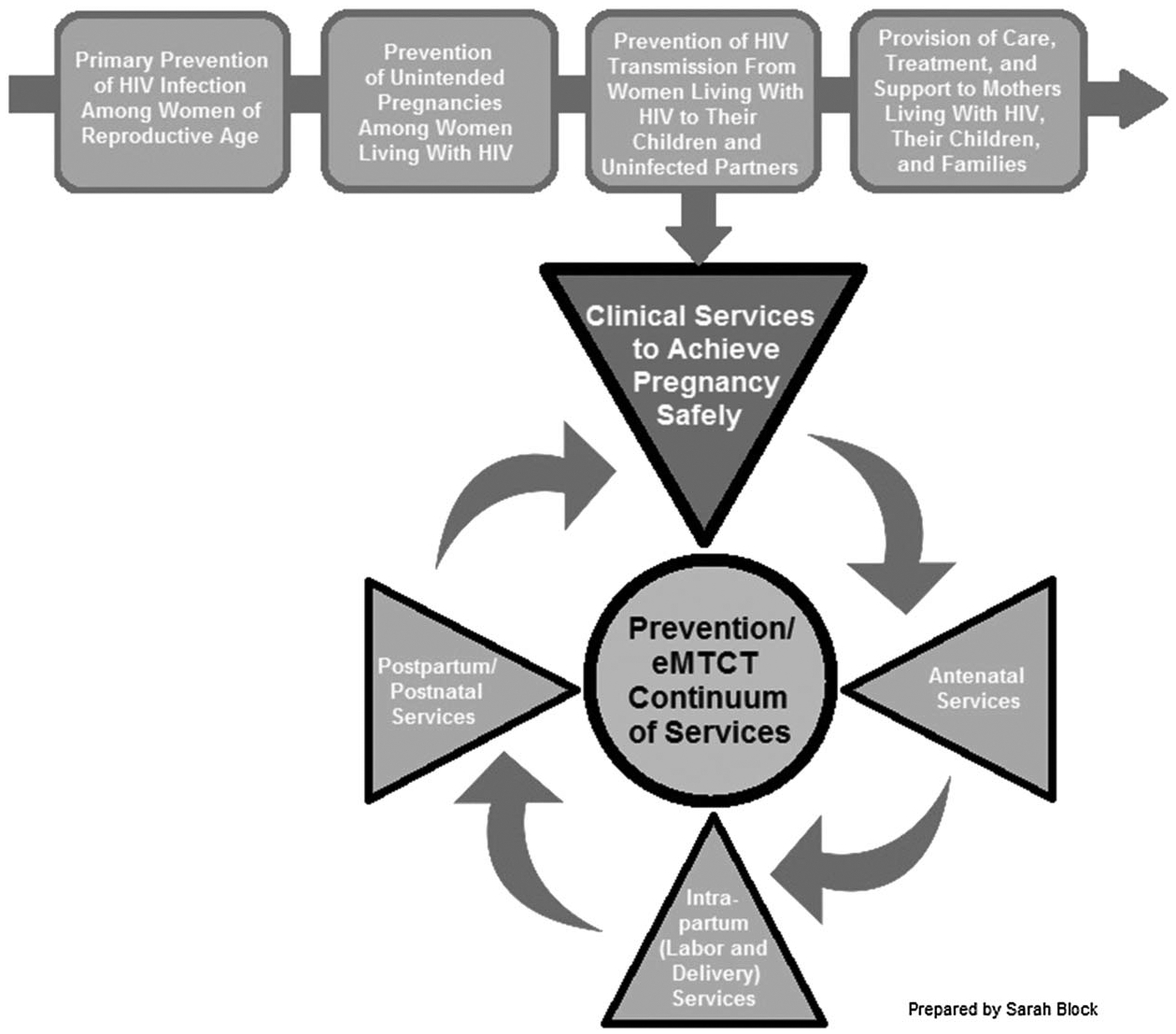

The existing four-pronged prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) strategy, developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), includes (1) prevention of HIV in women of reproductive age; (2) prevention of unintended pregnancy in women with HIV; (3) prevention of HIV transmission from mother to child; and (4) the provision of ongoing care and support to mothers, their children, and their families.8 All four prongs are rooted in prevention of sexual and perinatal HIV transmission, HIV testing, use of ART for mothers and infants, exclusive breast-feeding, and access to contraceptive services. The continuum of care services are included within the third WHO prong, including antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum/postnatal health care services (Fig. 1). However, provision of education and clinical services for achieving pregnancy safely is not uniquely addressed in the current WHO eMTCT strategy,8 and we believe that they should be included within the continuum of care services of the third prong of the strategy that addresses: “prevention of HIV transmission from mother to child.”

FIGURE 1.

Redefining the prevention/eMTCT strategy.

NEW KNOWLEDGE ON SAFER PRE-PREGNANCY OPTIONS AS HIV INTERVENTIONS

In order to broaden our reach in HIV prevention, we propose this new approach within the existing prevention strategy to expand fertility service options that will address all the reproductive desires of HIV-affected individuals and couples. They need positive guidance and support from health care providers to minimize sexual HIV transmission. Without this assistance in achieving pregnancy safely, HIV-affected individuals and couples risk HIV transmission to the uninfected partner, especially in the absence of ART, viral suppression, and/or PrEP.9 The eMTCT spectrum of care provides an ideal construct for the inclusion of pre-pregnancy services particularly when engagement of the male partner is achieved to reduce the risk of HIV transmission to the uninfected partner and developing fetus. To achieve this, advocacy groups will also need to call for policy changes to include the integration of couples counseling and fertility service options for achieving pregnancy safely into existing HIV care and prevention strategies.

PROBLEM TO BE ADDRESSED

More than 35 million people worldwide live with HIV, and up to 60% of new HIV infections occur in HIV-serodiscordant partnerships.10,11 In Kenya alone, there are an estimated 260,000 HIV-serodiscordant couples.12 In order to reduce mother-to-child transmission in Kenya to below 5% by the end of 2015, greater than 90% of HIV-infected women need to be identified, treated with ART, and offered other HIV prevention interventions.13 Theassurance of comprehensive reproductive care services that addresses the spectrum of reproductive health care needs across an HIV-infected individual’s life cycle is a component that is missing from current programs, largely due to the ignorance of their value as essential to reducing heterosexual and subsequent vertical transmission of HIV.

Before expanded access to effective ART, health care providers actively discouraged HIV-affected women from becoming pregnant.14 Although ART is now more accessible in sub-Saharan Africa, one report documented that less than half of known HIV-infected individuals in Kenya achieved viral suppression (ie, HIV RNA, 1000 copies).12 Similarly, only 30% of all HIV-infected individuals in the United States are virally suppressed as per the most recent estimates.15

Despite the shift in reproductive guidelines supporting pregnancy in HIV-affected persons,16–21 most health care facilities in sub-Saharan Africa do not offer safer options for couples attempting to become pregnant.22,23 HIV-infected women who express a desire for children often encounter the disapproval of their communities and/or health care workers.23

COMPREHENSIVE eMTCT/PMTCT STRATEGY

Incorporating pre-pregnancy and “safer conception” services into eMTCT (Fig. 1) allows healthy HIV-affected individuals to choose to achieve their reproductive goals of childbearing while minimizing risks of HIV transmission from or to their uninfected partners. Lower-cost assisted fertility interventions for achieving pregnancy safely include initiation of lifelong ART for the HIV-infected partner and/or PrEP for the HIV-uninfected partner. Other approaches include timed vaginal insemination or sperm washing with intrauterine insemination. To achieve success in global HIV prevention, a combination of interventions incorporating behavioral and biomedical interventions are required. Hence, treatment as prevention (ie, starting ART to prevent HIV transmission) coupled with timed condomless intercourse, with or without PrEP, should not be the only option for HIV-affected individuals and couples desiring children. These interventions require continued engagement in care—adherence to ART and/or PrEP as well as HIV viral load monitoring for the HIV-infected partner (Table 1). Regardless, the goals for reproductive health programs for HIV-serodiscordant couples need to both help protect the HIV-uninfected partner while ensuring the autonomy of the HIV-infected partner through the use of multiple options to achieve pregnancy safely. Finally, to address HIV-related stigma and close the gap in health care services, health care providers must be equipped with training, educational materials, and the clinical supplies required to provide safer pre-pregnancy services for HIV-affected couples desiring children.

TABLE 1.

Interventions for Achieving Pregnancy Safely in HIV-Affected Couples*

| Treatment as Prevention With Timed Condomless Intercourse | PrEP | SW-IUI | TVI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment | ||||

| High-income country† | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Low- and middle-income country† | ● | ‡ | ‡ | ● |

| HIV-serodiscordant couple | ||||

| ♂+/♀−§ | ● | ● | ● | |

| ♂−/♀+§ | ● | ● | ● | |

| Estimated risk reduction | 95%2 | 63%−73%3 | 100%4,5 | 100% |

Screening and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases decrease the risk of HIV transmission/acquisition, estimated risk reduction up to 40%.

World Bank Classification.

Not readily available in low- and middle-income country prepared by Sarah Block.

HIV viral RNA suppression should be assured, if possible.

SW-IUI, sperm washing with intrauterine insemination; TVI, timed vaginal insemination.

Prevention of HIV transmission to the uninfected male partner in female-positive HIV-serodiscordant couples is critical to ensuring male partner involvement and improved success of eMTCT interventions at the community level.24 In sub-Saharan Africa, men possess social and economic power, and often play a major role in their partners’ health decision making.25 For example, successful uptake and integration of contraceptive services into HIV care and treatment in Kenya was accelerated by the acceptance and participation of the male partner.26 Similarly, the extent to which male partner involvement can facilitate the uptake and adaptation of pre-pregnancy services requires research within the eMTCT strategy.27

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Achieving the ambitious goal of zero HIV transmission to unborn children and sexual partners requires enhancement of the existing eMTCT strategy. To achieve this, advocacy groups need to call for policy changes that integrate couples counseling and fertility service options into existing HIV care and prevention strategies. An interdisciplinary approach, inclusive of health care providers and administrators, policy makers, laboratory staff, researchers, donors, and community members, is critical to the integration and acceptance of lower cost and safer reproductive options into the eMTCT strategy for HIV-affected couples desiring children.28,29 These stakeholders should work together to promote the development of evidence-based clinical guidelines to support and integrate reproductive services into HIV care and treatment programs. At any given time along the reproductive spectrum, safer conception options must be recognized as a critical priority element of any comprehensive “family planning” initiative that are currently viewed only through the prism of contraception, child spacing, and access to safe abortion.

We encourage support for research on, and implementation of, safer pre-pregnancy interventions, including funding for the development and dissemination of educational training materials for health care providers that are relevant to LMICs.22 In the changing context of ART initiation guidelines, we must accept that some HIV-infected individuals will make the choice to delay ART.30,31 Respecting their autonomy and decision making requires the provision of safer pre-pregnancy options that may include ART and/or PrEP. Recognition and support of the childbearing desires and reproductive rights of HIV-affected individuals and couples require that fertility services be made accessible, affordable, and integrated into the prevention and eMTCT care continuum.

Acknowledgments

O.M. has received funding as an independent contractor from the World Health Organization. C.R.C. has received support as a consultant for the WHO and Symbiomix. S.V. has received funding from Mead Johnson Nutrition Company and is a member of the editorial board of the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. The remaining authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

For the purpose of this letter an HIV-affected individual/couple refers to person(s) living in an HIV endemic region where one person is HIV-infected or of unknown HIV status;

timed condomless intercourse refers to sexual intercourse without a condom timed to peak fertility during ovulation and/or in combination with antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the HIV-infected partner and/or PrEP for the uninfected partner.

REFERENCES

- 1.Matthews LT, Mukherjee JS. Strategies for harm reduction among HIV-affected couples who want to conceive. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(suppl 1):5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MS, Gay CL. Treatment to prevent transmission of HIV-1. Clin Infect Dis. 2010; 50(suppl 3):S85–S95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Semprini AE, Levi-Setti P, Bozzo M, et al. Insemination of HIV-negative women with processed semen of HIV-positive partners. Lancet. 1992;340:1317–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savasi V, Mandia L, Laoreti A, et al. Reproductive assistance in HIV serodiscordant couples. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19: 136–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mmeje O, Cohen CR, Cohan D. Evaluating safer conception options for HIV-serodiscordant couples (HIV-infected female/HIV-uninfected male): a closer look at vaginal insemination. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:587651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mmeje O, van der Poel S, Workneh M, et al. Achieving pregnancy safely: perspectives on timed vaginal insemination among HIV-serodiscordant couples and health-care providers in Kisumu, Kenya. AIDS Care. 2015; 27:10–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayashi C, Shaffer N, Souteyrand Y. Global Monitoring Framework and Strategy for the Global Plan Towards the Elimination of New HIV Infections Among Children by 2015 and Keeping Their Mothers Alive (EMTCT); 2012. World Health Organization. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75341/1/9789241504270_eng.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brubaker SG, Bukusi EA, Odoyo J, et al. Pregnancy and HIV transmission among HIV-discordant couples in a clinical trial in Kisumu, Kenya. HIV Med. 2011;12:316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV. UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2013. 2013. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/campaigns/globalreport2013/globalreport. Accessed July 8, 2015.

- 11.Dunkle KL, Stephenson R, Karita E, et al. New heterosexually transmitted HIV infections in married or cohabiting couples in urban Zambia and Rwanda: an analysis of survey and clinical data. Lancet. 2008;371:2183–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National AIDS and STI Control Programme, Ministry of Health, Kenya. Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2012: Preliminary Report; 2013. Available at: http://www.faces-kenya.org/2013/09/preliminary-report-for-kenya-aids-indicator-survey-2012/. Accessed July 8, 2015.

- 13.Sirengo M, Muthoni L, Kellogg TA, et al. Mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Kenya: results from a nationally representative study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66 (suppl 1):S66–S74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chadwick RJ, Mantell JE, Moodley J, et al. Safer conception interventions for HIV-affected couples: implications for resource-constrained settings. Top Antivir Med. 2011;19:148–155. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22156217. Accessed July 8, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley H, Hall HI, Wolitski RJ, et al. Vital Signs: HIV diagnosis, care, and treatment among persons living with HIV—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63: 1113–1117. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6347a5.htm?s_cid=mm6347a5_w. Accessed July 8, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Africa D of HR of S. National Contraception and Fertility Planning Policy and Service Delivery Guidelines. Pretoria; 2012. Available at: http://www.health-e.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/National-contraception-family-planning-policy.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clutterbuck DJ, Flowers P, Barber T, et al. UK national guideline on safer sex advice. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23:381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bekker L, Black V, Myer L, et al. Guideline on safer conception in fertile HIV-infected individuals and couples. South J HIV Med. 2011;12:31–44. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weber S, Waldura JF, Cohan D. Safer conception options for HIV serodifferent couples in the United States: the experience of the National Perinatal HIV Hotline and Clinicians’ Network. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63:e140–e141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panel on Treatment of HIV-Infected Pregnant Women and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnant HIV-1-Infected Women for Maternal Health and Interventions to Recommendations for Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnant HIV-1-Infected Women for Maternal Health and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States; 2014. Available at: http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/PerinatalGL.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2015.

- 21.Loutfy MR, Margolese S, Money DM, et al. Canadian HIV pregnancy planning guidelines. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012;34:575–590. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23125998. Accessed July 8, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myer L, Morroni C, Cooper D. Community attitudes towards sexual activity and childbearing by HIV-positive people in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2006;18:772–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaida A, Laher F, Strathdee SA, et al. Childbearing intentions of HIV-positive women of reproductive age in Soweto, South Africa: the influence of expanding access to HAART in an HIV hyperendemic setting. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:350–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Inter-Agency Task Team for Prevention and Treatment of HIV Infection in Pregnant Women, Mothers and Their Children. Preventing HIV and Unintended Pregnancies : Strategic Framework 2011–2015; 2012. Available at: http://www.unfpa.org/publications/preventing-hiv-and-unintended-pregnancies-strategic-framework-2011-2015. Accessed July 8, 2015.

- 25.Dunlap J, Foderingham N, Bussell S, et al. Male involvement for the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission: a brief review of initiatives in East, West, and Central Africa. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014;11:109–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grossman D, Onono M, Newmann SJ, et al. Integration of family planning services into HIV care and treatment in Kenya: a cluster-randomized trial. AIDS. 2013;27(suppl 1):S77–S85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aliyu M, Blevins M, Audet CM, et al. Optimizing PMTCT service delivery in rural North Central Nigeria: protocol and design for a cluster randomized study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013; 36:187–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breitnauer BT, Mmeje O, Njoroge B, et al. Community perceptions of childbearing and use of safer conception strategies among HIV-discordant couples in. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015; 18:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mmeje O, Titler M, Dalton V. A call to action: evidence-based safer conception interventions in HIV-affected couples desiring children in sub-Sharan africa. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2014; 128(1):73–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curran K, Ngure K, Shell-Duncan B, et al. “If I am given antiretrovirals I will think I am nearing the grave”: Kenyan HIV serodiscordant couples’ attitudes regarding early initiation of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2014;28:227–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts ST, Heffron R, Ngure K, et al. Preferences for daily or intermittent pre-exposure prophylaxis regimens and ability to anticipate sex among HIV uninfected members of Kenyan HIV serodiscordant couples. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:1701–1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]