Female sexual dysfunction (FSD) is a widespread condition that is least addressed in clinical practice worldwide. Vaginismus is a relatively rare FSD with a low prevalence in society but a higher reported clinical prevalence rate of 5-7%.1 The term vaginismus was coined by James Marion Sims in 1862.2

Vaginismus was defined by DSM IV-TR as “a recurrent or persistent involuntary spasm of the musculature of the outer third of the vagina, which interferes with coitus and causes distress and interpersonal difficulty”.3 Dyspareunia is characterized by genital and/or pelvic pain. Because of the challenges in differentiating these two, DSM-5 combined them into a single-entity genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder.4 However, dyspareunia is caused primarily by physical or medical factors, whereas vaginismus is caused mainly by psychological factors. Dyspareunia is associated with sexual abuse, whereas vaginismus is related to sexual and emotional abuse.5 Treatment for dyspareunia includes addressing underlying causes and pain management, whereas treatment of vaginismus focuses on alleviating fear and pelvic muscle spasms. Because the treatment approach in these two conditions differs slightly, all efforts should be taken to diagnose correctly.

According to the definition, involuntary spasm of the vaginal musculature is an important requirement for the diagnosis of vaginismus. In one study, only 28% of the vaginismus group had vaginal muscle spasms, and only 24% had spasms during attempted sexual intercourse. Similarly, two independent gynecologists agreed on the diagnosis of vaginismus only 4% of the time, adding to the diagnostic confusion.6

On induction of the vaginismus reflex, surface EMG (SEMG) or needle electromyography revealed higher vaginal/pelvic muscle (levator ani, puborectalis, and bulbocavernosus muscles) tone than the control group.6,7 However, other studies have failed to show increased muscle spasms8 in people with vaginismus, adding to the diagnostic confusion. Although some people regard pain to be a factor in the diagnosis of vaginismus, numerous professional groups (DSM, ACOS, IASP, and World Health Organization) do not include it in their criteria.

Excessive dread of pain during penetration is a common symptom reported by people with vaginismus.6,9 A phobia is defined as “a marked and persistent fear that is excessive or unreasonable that is triggered by the presence or anticipation of a specific object or situation”;10 thus, vaginismus is considered a phobia. People with dyspareunia experience pain but do not avoid vaginal penetration situations, in contrast to those with vaginismus, demonstrating that the avoidance of vaginal penetration in people with vaginismus cannot be explained merely by pain.6,11

Provoked vestibulodynia (PVD), a subtype of dyspareunia in which females develop severe intense burning pain on vestibular touch or attempted vaginal entry, has symptoms with vaginismus, such as increased pelvic/vaginal muscle tone,6,11,12 making distinction challenging. However, vaginismus is a phobic disorder characterized by significant emotional distress, fear, or anxiety with vaginal penetration, which helps to differentiate between the two. PVD often causes superficial dyspareunia, which may be detected with a cotton swab test.13 According to one study, 72.4% of women with vaginismus had dyspareunia symptoms, and 47.7% of women with dyspareunia had vaginismus symptoms.14

Before diagnosing vaginismus, always rule out secondary causes in women who had difficulty penetrating despite their expressed wish to do so.15 People with severe vaginismus refuses vaginal examinations because they were afraid of being penetration. Some people deliberately refuse vaginal penetrative intercourse with their partner for reasons such as spouse rejection and extramarital relationships. When they are brought in for clinical examination, they refuse vaginal examination purposefully, citing spurious reasons, such as fear or pain. Differentiating between people who claim to have difficulties allowing vaginal penetration and true vaginismus is challenging and requires multiple sessions of detailed history collection and clinical evaluation. Some of these people will be misdiagnosed with vaginismus, which is more accurately called “pseudo-vaginismus.” Those who avoid sexual intercourse on purpose (pseudo-vaginismus) must be distinguished from those who have actual vaginismus, in which penetration is difficult despite an expressed wish to do so.

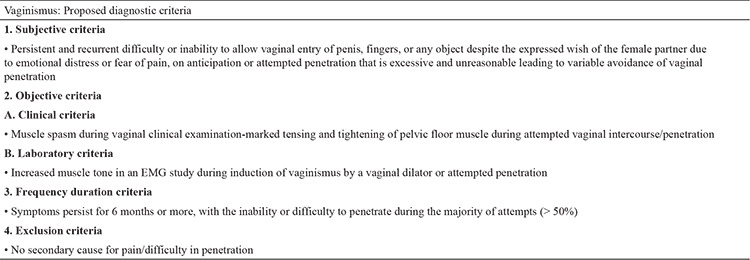

We propose criteria for diagnosing vaginismus based on our clinical experience and review of relevant literature (Table 1). It consists of subjective criteria, objective criteria, frequency duration criteria, and exclusion criteria.

Table 1. Vaginismus: Proposed Diagnostic Criteria.

The most common clinical manifestation of vaginismus is difficulty with vaginal penetration, which is typically associated with fear or emotional distress. During attempted penetration, the female partner complains of fear, pain, and discomfort, and the male partner is unable to enter and generally feels like he is “hitting a wall.” Typically, after a prolonged attempt to penetrate, the male partner would lose erection, leading to a misdiagnosis of erectile dysfunction in the male partner. Sometimes, a couple will present to an infertility clinic with an unconsummated marriage.

Associated sexual distress and interpersonal problems are included in the diagnosis of vaginismus in DSM definition. But these are not included in our proposed diagnostic criteria. We believe that distress happens due to sexual dysfunction. Distress is influenced by various factors, such as interpersonal relationships and sociocultural factors. As a result, associated distress indicates the impact of vaginismus and, in turn, its severity. Therefore, according to the proposed criteria, distress is not required for the diagnosis of vaginismus.

The presence of increased muscle spasm on per vaginal examination (partial vaginismus) or spasm leading to inability to perform per vaginal examination (total vaginismus) which is disproportionate to the anticipated pain from underlying pathology confirms the diagnosis of vaginismus and is an objective clinical criterion for making the diagnosis of vaginismus. Electromyography (EMG) or needle EMG might show the same result, confirming the diagnosis of vaginismus. According to the proposed diagnostic criteria, the presence of one of the objective clinical or laboratory (EMG) criteria is essential for diagnosing vaginismus.

In severe cases of vaginismus the patient elevates her buttocks and closes her thighs to prevent vaginal examination. In extreme cases, in addition to generalized retreat, there will be visceral reactions (e.g., palpitations, hyperventilation, sweating, severe trembling, uncontrollable shaking, screaming, hysteria, wanting to jump off the table, a feeling of becoming unconscious, nausea, vomiting, and even a desire to attack the doctor).16,17

Genital examination not only confirms increased muscle tone but also rules out secondary causes of pain on penetration in persons with suspected vaginismus.

The frequency-duration criteria include the persistence of symptoms for more than 50% of the time for a period of 6 months or longer. Those who do not meet the frequency duration criteria are diagnosed with transient vaginismus. Transient vaginismus includes situational vaginismus.

Before diagnosing vaginismus, conditions that might cause pain during vaginal penetration must be ruled out. The symptoms of vestibulodynia and dyspareunia can sometimes overlap with those of vaginismus.

Vaginismus is a phobic disorder, whereas dyspareunia is a pain disorder. Some people with painful genital conditions experience pain and spasms that are out of proportion to the underlying condition, resulting in phobic fear of penetration, a condition better called as dyspareunia vaginismus overlap syndrome. So, there will be features of both dyspareunia and vaginismus. Some people have both dyspareunia and vaginismus, and it is better considered as a spectrum of diseases, with one end being pure vaginismus and the other end being pure dyspareunia. Hence, DSM-5 classified them as genital pain/penetration disorder.4 However, they are treated differently. Therefore, it is essential to assess the contribution of each component and make a clear diagnosis to plan proper management.

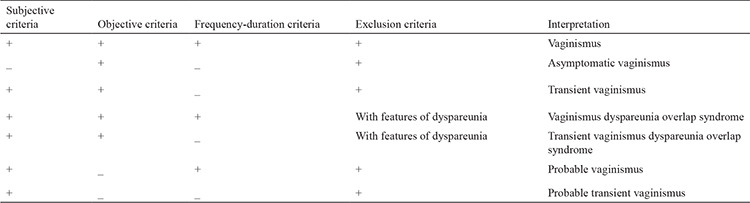

According to the newly proposed criteria, those who meet the subjective, objective, and frequency–duration criteria and the exclusion criteria are classified as having vaginismus, whereas those who do not meet the frequency duration criteria are classified as having transient vaginismus (Table 2). Those who have features of vaginismus and dyspareunia are diagnosed with vaginismus dyspareunia overlap syndrome.

Table 2. Interpretation of Diagnostic Criteria.

We expect that the proposed diagnostic criteria would be useful for practicing clinicians worldwide in confidently diagnosing vaginismus and providing appropriate care to those in need.

To summarize, vaginismus, a common female sexual disorder, is challenging to diagnose, and the proposed criteria are likely to help practicing clinicians worldwide overcome these challenges.

Footnotes

Authorship Contributions: Concept- A.V.R, P.R.; Design- A.V.R, P.R.; Data Collection or Processing- A.V.R, P.R.; Analysis or Interpretation- A.V.R, P.R.; Literature Search- A.V.R, P.R.; Writing- A.V.R, P.R.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Funding: The authors declared that this study received no financial support.

References

- 1.Spector I, Carey M. Incidence and prevalence of the sexual dysfunctions: a critical review of the empirical literature. Arch Sex Behav. 1990;19:389–396. doi: 10.1007/BF01541933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huguier PC. Dissertation sur quelques points d’anatomie, de physiologie et de pathologie. Medical thesis, Paris, France. 1834. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. American Psychiatric Association. [Internet]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Text Revision (DSM-5-TR). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2022. [Internet]

- 5.Tetik S, Yalçınkaya Alkar Ö. Vaginismus, Dyspareunia and Abuse History: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2021;18:1555–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reissing ED, Binik YM, Khalifé S, Cohen D, Amsel R. Vaginal spasm, pain, and behavior: an empirical investigation of the diagnosis of vaginismus. Arch Sex Beh. 2004;33:5–17. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000007458.32852.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shafik A, El-Sibai O. Study of the pelvic floor muscles in vaginismus: a concept of pathogenesis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;105:67–70. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(02)00115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engman M, Lindehammar H, Wijma B. Surface electromyography diagnostics in women with partial vaginismus with or without vulvar vestibulitis and in asymptomatic women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;25:281–294. doi: 10.1080/01674820400017921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward E, Ogden J. Experiencing vaginismus sufferers’ beliefs about causes and effects. Sex Marital Ther. 1994;9:33–45. [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. First MB (Ed.). American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, USA; 2000. [Internet]

- 11.De Kruiff ME, Ter Kuile MM, Weijenborg PT, Van Lankveld JJ. Vaginismus and dyspareunia: is there a difference in clinical presentation? J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;21:149–155. doi: 10.3109/01674820009075622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meana M, Binik YM, Khalife S, Cohen D. Dyspareunia: sexual dysfunction or pain syndrome? J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:561–569. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199709000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedrich EG. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. J Reprod Med. 1987;32:110–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peixoto M, Nobre P. Prevalence of female sexual problems in Portugal: A community-based study. J Sex Marital Ther. 2013;10:394. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2013.842195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weijmar Schultz W, Basson R, Binik Y, Eschenbach D, Wesselmann U, Van Lankveld J. Women’s sexual pain and its management. J Sex Med. 2005;2:301–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.20347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamont JA. Vaginismus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1978;131:633–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pacik PT. Understanding and treating vaginismus: a multimodal approach. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:1613–1620. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2421-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]