Abstract

The meningococcal hemA gene was cloned and used to construct a porphyrin biosynthesis mutant. An analysis of the hemA mutant indicated that meningococci can transport intact porphyrin from heme (Hm), hemoglobin (Hb), and Hb-haptoglobin (Hp). By constructing a HemA− HpuAB− double mutant, we demonstrated that HpuAB is required for the transport of porphyrin from Hb and Hb-Hp.

The acquisition of Fe is a well-defined determinant of bacterial pathogenesis. In response to Fe starvation, the exclusively human pathogen Neisseria meningitidis produces ligand-specific Fe transport proteins involved in the acquisition of Fe from the host Fe binding compounds transferrin, lactoferrin, heme (Hm), hemoglobin (Hb), and Hb complexed to the serum glycoprotein haptoglobin (Hb-Hp) (13, 15–18, 21, 22, 24–26). Meningococcal iron-acquisition processes, with the exception of Hm transport (2, 31), are functionally dependent on the TonB protein for transmitting energy from the cytoplasmic membrane to the outer membrane. Both single and two-component TonB-dependent transport systems for neisseriae have been described. The single-component systems each consist of a TonB-dependent outer membrane transporter and are analogous to the well-characterized siderophore receptors in many gram-negative bacteria (14, 23). The two-component systems consist of a TonB-dependent outer membrane receptor and an accessory lipoprotein. The meningococcal transferrin utilization system, which has been described in detail in a recent review, is a typical two-component transport system (7).

Two distinct systems involved in the acquisition of Fe from Hb by N. meningitidis have been described. We previously described HpuAB, a two-component receptor composed of a lipoprotein, HpuA, and a TonB-dependent transport protein, HpuB (16, 17). The HpuAB receptor mediates binding to Hb, Hb-Hp, and apo-Hp and is involved in the acquisition of Fe from both Hb and Hb-Hp. The HpuAB transporter is not involved in the acquisition of Fe from Hm. Stojiljkovic et al. described HmbR, a single-component TonB-dependent outer membrane receptor involved in both the binding to and Fe acquisition from Hb (29). HmbR is not involved in the acquisition of Fe from Hb-Hp or Hm. Some meningococcal strains appear to express either HpuAB or HmbR, while other strains express both HpuAB and HmbR (30). N. meningitidis DNM2, the strain used in this study, expresses HpuAB but not HmbR (16, 17).

How is Fe acquired from Hm-containing compounds such as Hb and Hb-Hp? Two possibilities are readily apparent. Either Hm (protoporphyrin IX plus Fe) is removed from Hb and Hb-Hp and transported into the cell or Fe is removed from Hb and Hb-Hp at the cell surface and Fe is transported into the cell. Removal and transport of intact Hm from Hb have been documented for several organisms such as Haemophilus influenzae and Yersinia enterocolitica (8, 27, 28). The N. meningitidis hmbR locus was cloned by complementation of an Escherichia coli porphyrin synthesis mutant suggesting that, in E. coli, HmbR transports Hm from Hb to supply both Fe and porphyrin to the cell (29). Conversely, Desai et al. detected the transport of 59Fe from [59Fe]Hm into gonococci but did not detect the transport of 14C from [14C]Hm (10). This suggests that Neisseria gonorrhoeae removes Fe from the Hm ring and transports only Fe into the periplasm (10), and by inference suggests that the related pathogen N. meningitidis may also extract Fe from Hm prior to transport. The goal of this study was first to determine if meningococci transport protoporphyrin IX and Fe or only transport Fe from Hm, Hb, and Hb-Hp. Second, we wished to determine the role of HpuAB in the transport of porphyrin from Hb and Hb-Hp. We constructed a porphyrin biosynthesis mutant of N. meningitidis DNM2 and determined that Hm, Hb, and Hb-Hp could supply porphyrin to support growth. Furthermore, our studies demonstrate that the HpuAB receptor complex is responsible for porphyrin transport from Hb and Hb-Hp.

Construction of a porphyrin biosynthesis (hemA) mutant.

To determine if N. meningitidis DNM2 (HpuAB+ HmbR−) was able to transport porphyrin, we sought to construct a hemA (glutamyl tRNA reductase gene) mutant which would not be able to synthesize δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA), a required precursor for tetrapyrrole synthesis (1). HemA mutants of E. coli are dependent on exogenous ALA to support growth (1).

A putative neisserial hemA gene was identified in the Gonococcal Genome Sequence database (http://www.genome.ou.edu) by using the tblastn algorithm and the E. coli HemA sequence (accession no., M30785) as a query (12). The hemA gene was amplified from both N. meningitidis DNM2 and N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 by PCR (30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C, annealing at 58°C, and extension at 72°C with the PCR Core Kit from Boehringer Mannheim) with primers designed to the putative gonococcal hemA (primer hemA449, CGGTCTATATCCATCTTCACC; primer hemA1717, CGGCGCACCGTTATTTGTCCA). A 1.3-kb DNA fragment was amplified from chromosomal DNA isolated from each of these organisms, and the amplified DNA was cloned into pCR-TOPO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) to create pDMHS2 (meningococcal hemA) and pDMHS1 (gonococcal hemA) (Table 1). The DNA sequence of each gene was determined by primer walking with an Applied Biosystems model 377XL automated DNA sequencer as previously described (6). At least two independent clones were sequenced in each case to ensure that PCR-induced mutations were not present. The meningococcal and gonococcal hemA clones contained open reading frames of 415 amino acids which were 98% identical to each other and 64% similar (54% identical) to HemA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant properties | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pDMHS1 | 1.3-kb hemA fragment from FA1090 in pCR-TOPO | This work |

| pDMHS2 | 1.3-kb hemA fragment from DNM2 in pCR-TOPO | This work |

| pDMHS3 | EcoRI fragment from pDMHS1 in the EcoRI site of pGem7zf+ | This work |

| pDMHS5 | pDMHS3 with aphA3 in HincII site (hemA::aphA3) | This work |

| N. meningitidis | ||

| DNM2 | Serogroup C, serotype 2a; Nalr | 16 |

| DNM2E4 | DNM2 hpuB::mTn3erm (hpuAB mutant); Ermr Nalr | 16 |

| DNM502 | DNM2 hemA::aphA3; Kanr Nalr | This work |

| DNM504 | DNM2E4 hemA::aphA3; Ermr Kanr Nalr | This work |

| N. gonorrhoeae | ||

| FA1090 | 19 | |

| DNG7 | FA1090 hemA::aphA3 | This work |

To confirm that the cloned gene was the meningococcal hemA locus, we constructed a knockout mutation of the putative hemA gene in N. meningitidis DNM2. The aphA3 kanamycin resistance cassette from pMGC20 (20) was ligated into HincII-digested pDMHS3 (Table 1). This resulted in the deletion of an internal 234-bp HincII fragment of hemA and the insertion of the 1.8-kb aphA3 cassette. Kanamycin-resistant (40 μg/ml) E. coli transformants were screened by restriction enzyme digestion and PCR amplification with primers hemA449 and hemA1717. A 2.8-kb fragment, consistent with the deletion of 234 bp of hemA and the insertion of 1.8-kb of aphA3 into the hemA locus, was amplified from pDMHS5 (Table 1), indicating that this plasmid contained aphA3 properly inserted in the hemA gene (data not shown). The mutated hemA was amplified (as described above) from pDMHS5 with primers which contained the neisserial uptake sequence (primer hemA449up, GCCGTCTGAACGGTCTATATCCATCTTCACC; primer hemA1717up, GCCGTCTGAACGGCGCACCGTTATTTGTCCA). One microgram of the purified PCR product was used to transform N. meningitidis DNM2 as previously described (3). Transformants were selected on GC agar containing IsoVitaleX (1%), ALA (30 μg/ml), and kanamycin (100 μg/ml). Several kanamycin-resistant transformants were isolated and analyzed by PCR with primers hemA449 and hemA1717. A 2.8-kb DNA fragment was amplified from a transformant designated DNM502. As above, this result is consistent with the proper insertion of AphA3 in the hemA locus (data not shown). As expected, a 1.3-kb fragment was amplified from DNM2 (data not shown).

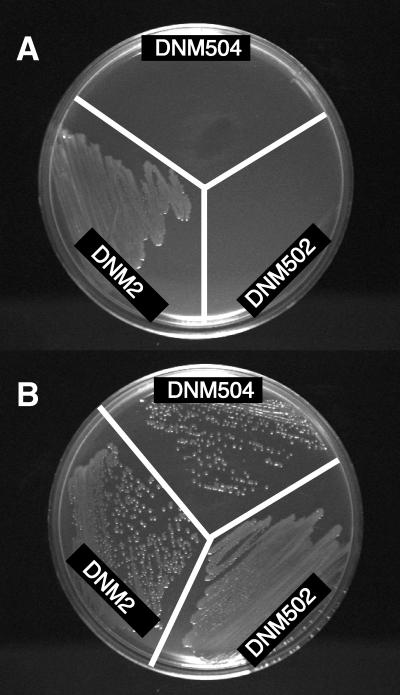

To determine if the phenotype of strain DNM502 was consistent with that produced by a hemA mutation, we examined the dependence of DNM502 on ALA. DNM2 and DNM502 were inoculated onto GC agar plates supplemented with IsoVitaleX (1%) (Fig. 1A) and onto GC agar plates supplemented with ALA (30 μg/ml) and IsoVitaleX (Fig. 1B). While DNM2 grew in the absence of exogenous ALA, DNM502 was not able to grow in the absence of exogenous ALA, consistent with the predicted phenotype produced by the putative hemA mutation.

FIG. 1.

ALA dependence of hemA mutants of N. meningitidis DNM2. Meningococci were inoculated onto GC agar plates containing IsoVitaleX (A) or IsoVitaleX and ALA (B).

Transport of porphyrin by N. meningitidis DNM2.

In E. coli, ALA is able to support the growth of a hemA mutant because ALA is transported into the cell via the dipeptide permease system (1). In laboratory strains of E. coli, Hm and Hm compounds do not support the growth of a hemA mutant because the enterobacterial outer membrane is impermeable to Hm and laboratory strains of E. coli do not possess specific transport systems for Hm or Hm compounds. In fact, E. coli hemA mutants have been used as a tool to clone Hm transport systems from several pathogenic microorganisms (9, 29).

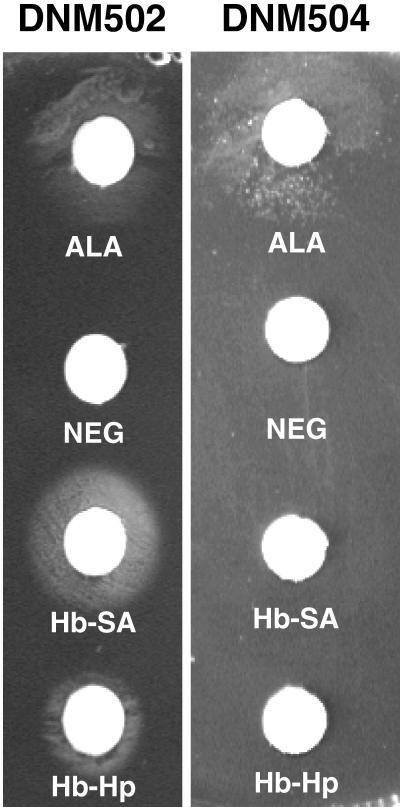

To determine if DNM2 contains specific transport systems which allow intact porphyrin to enter the cell, we examined the ability of DNM502 to grow by using Hm, Hb, and Hb-Hp in place of ALA. Hm, serum albumin (SA), Hm-SA, Hb, Hb-SA, and Hb-Hp were prepared as previously described (11, 16). SA forms a complex with Hm, and the meningococcus is not able to acquire Fe from an Hm-SA complex (11). SA was added to Hb (Hb-SA) to ensure that free Hm released from Hb was not available to the meningococcus. Hm-SA was used as a control to confirm that Hm-SA was not able to support growth. DNM2 and DNM502 were spread onto CDM-0 agar plates (4) either directly or in GC top agar (0.7% GC base agar; Difco). Sterile 6-mm-diameter filter paper discs (Whatman no. 3) were saturated with 10 μl of Hm-containing compound and applied to the surfaces of the CDM-0 plates. Whatman discs saturated with ALA or buffer were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. DNM502 grew around discs containing ALA (3 nmol) (Fig. 2), Hm (5 nmol) (data not shown), Hb + SA (1 nmol of Hb plus 15 nmol of SA) (Fig. 2), and Hb-Hp (0.5 nmol of Hb in an Hb-Hp complex) (Fig. 2). Growth was not observed around discs containing SA (20 nmol) or Hm-SA (5 nmol of Hm–20 nmol of SA) (data not shown) or around the negative-control disc (Fig. 2). The growth of wild-type DNM2 was not dependent on exogenous Hm or ALA, and thus DNM2 grew to confluence on the CDM-0 agar plates and around all discs (data not shown). The ability of DNM502 to grow in the absence of ALA when supplied with Hm, Hb + SA, or Hb-Hp suggests that DNM502 is able to transport intact porphyrin from each of these sources to overcome the hemA mutation.

FIG. 2.

HpuAB-dependent transport of porphyrin from Hb and Hb-Hp. Meningococci were inoculated onto CDM-0 agar plates. Sterile Whatman discs saturated with 10 μl of ALA, 10 mM HEPES (Neg), Hb-SA, or Hb-Hp were placed on the agar. Plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 24 h.

Transport of porphyrin by N. gonorrhoeae FA1090.

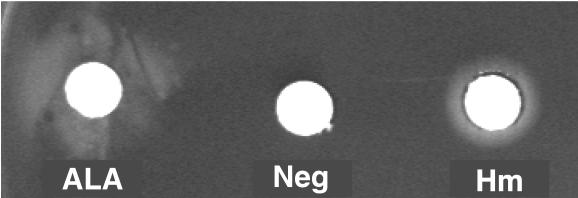

The observation that exogenous Hm can suppress the hemA growth defect in DNM502 indicates that N. meningitidis can transport intact porphyrin from Hm. This is in contrast to the observation of Desai et al., who suggested that gonococci separate Hm into Fe and porphyrin and only internalize the Fe from Hm. To determine if meningococci and gonococci differ in their abilities to transport porphyrin, we constructed a gonococcal HemA mutant and assessed the ability of this mutant to transport porphyrin from Hm. The mutated hemA gene from pDMHS5 was transferred into piliated N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 as described above, and transformants were selected on GC base agar supplemented with IsoVitaleX (1%), ALA (30 μg/ml), and kanamycin (50 μg/ml). PCR analysis with primers hemA449 and hemA1717, as described above, confirmed the proper insertion of aphA3 in the hemA locus of one kanamycin-resistant transformant, designated DNG7. The growth of DNG7 was dependent on exogenous ALA, consistent with the expected phenotype produced by a hemA mutation (Fig. 3). Surprisingly, DNG7 was able to grow in the absence of ALA, when Hm (8 nmol) was supplied as a source of porphyrin (Fig. 3). The growth of wild-type FA1090 was not dependent on exogenous ALA or Hm, and thus FA1090 grew to confluence on the CDM-0 agar plates and around all discs (data not shown). These studies indicate that FA1090, like DNM2, is able to transport porphyrin from Hm to overcome a hemA mutation.

FIG. 3.

Porphyrin transport by Neisseria gonorrhoeae FA1090. DNG7 was inoculated onto a CDM-0 agar plate, and sterile Whatman discs saturated with 10 μl of ALA, 10 mM HEPES (Neg), or Hm were placed on the agar. Plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 24 h.

Transport of intact porphyrin by HpuAB.

We have demonstrated that DNM2 transports intact porphyrin from Hm, Hb, and Hb-Hp. The only functional receptor for Hb and Hb-Hp expressed in strain DNM2 is HpuAB. Thus, we suspected that HpuAB was involved in the acquisition of porphyrin from Hb and Hb-Hp and constructed a double mutant that lacks HemA and HpuAB to test this hypothesis. Genomic DNA isolated from strain DNM502 was transformed into DNM2E4 (hpuB::mTn3erm) (16). Transformants were selected as described above (with ALA [30 μg/ml] and kanamycin [100 μg/ml]), and PCR with primers hemA449 and hemA1717 was used to confirm the proper location of the hemA mutation in the hpuB knockout strain, DNM2E4; the double mutant was designated DNM504. DNM504, like DNM502, was not able to grow in the absence of exogenous ALA (Fig. 1). Next, we assessed the ability of DNM504 to grow in the absence of ALA with Hm, Hm-SA, Hb, Hb + SA, and Hb-Hp as described above. Growth of DNM504 was observed around Whatman filter discs containing ALA or Hm (data not shown), indicating that expression of HpuAB is not required for ALA or Hm transport. Growth was not observed around discs containing SA, Hm-SA, Hb + SA, or Hb-Hp or around the negative-control disc (Fig. 2). Thisindicates that the ability to acquire porphyrin from Hb and Hb-Hp is dependent on the HpuAB transporter.

These studies demonstrate that the N. meningitidis HpuAB receptor complex transports intact porphyrin from Hb and Hb-Hp. Furthermore, our studies demonstrate that both N. meningitidis DNM2 and N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 can transport intact porphyrin from Hm. This finding directly contrasts with the observations of Desai et al., who examined Hm uptake in gonococcal strain F62 (10). Desai et al. failed to detect porphyrin transport in strain F62 with a [14C]Hm uptake assay (10). It is not possible to determine whether the [14C]Hm uptake assay used was sensitive enough to detect porphyrin transport because a positive control consisting of an organism known to transport porphyrin was not included in their experiments. In the absence of this control it is not possible to distinguish between a failure to detect the transport of porphyrin and a lack of porphyrin transport. We have not studied a HemA mutant of strain F62, and it is possible that this difference is due to strain variation between strains FA1090 and F62. The Hm transport system has not been well defined in Neisseria, although the process has been shown to be TonB independent (2, 31). Gonococcal strain F62 most likely expresses HpuAB, as this strain is able to acquire Fe from Hb-Hp (a phenotype uniquely correlated with HpuAB expression in pathogenic neisseriae) and probably contains an intact hpuAB locus (5, 11). Thus, we would expect strain F62 to transport porphyrin from Hb and Hb-Hp. To our knowledge, the present paper is the first report of the transport of intact porphyrin in the neisseriae. Stojiljkovic et al. demonstrated that the meningococcal HmbR receptor could transport porphyrin in an E. coli background; however, the transport of porphyrin by HmbR in Neisseria has not been demonstrated directly (29).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The DNA sequences for the hemA genes of N. meningitidis DNM2 and N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 were assigned GenBank accession numbers AF067427 and AF067426, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant AI38399 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beale S I. Biosynthesis of hemes. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 731–748. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biswas G D, Anderson J E, Sparling P F. Cloning and functional characterization of Neisseria gonorrhoeae tonB, exbB and exbD genes. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:169–179. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3421692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biswas G D, Sox T, Blackman E, Sparling P F. Factors affecting genetic transformation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Bacteriol. 1977;129:983–992. doi: 10.1128/jb.129.2.983-992.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanton K J, Biswas G D, Tsai J, Adams J, Dyer D W, Davis S M, Koch G G, Sen P K, Sparling P F. Genetic evidence that Neisseria gonorrhoeae produces specific receptors for transferrin and lactoferrin. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5225–5235. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.5225-5235.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, C., and P. F. Sparling. 1998. Personal communication.

- 6.Chissoe S L, Wang Y F, Clifton S W, Ma N, Sun H J, Lobsinger J S, Kenton S M, White J D, Roe B A. Strategies for rapid and accurate DNA sequencing. Methods Companion Methods Enzymol. 1991;3:55–65. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornelissen C N, Sparling P F. Iron piracy: acquisition of transferrin-bound iron by bacterial pathogens. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:843–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coulton J W, Pang J C S. Transport of hemin by Haemophilus influenzae type b. Curr Microbiol. 1983;9:93–98. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daskaleros P A, Stoebner J A, Payne S M. Iron uptake in Plesiomonas shigelloides: cloning of the genes for the heme-iron uptake system. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2706–2711. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2706-2711.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desai P J, Nzeribe R C, Genco C A. Binding and accumulation of hemin in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4634–4641. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4634-4641.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyer D W, West E P, Sparling P F. Effects of serum carrier proteins on the growth of pathogenic neisseriae with heme-bound iron. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2171–2175. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2171-2175.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gish W, States D J. Identification of protein coding regions by database similarity search. Nat New Genet. 1993;3:266–272. doi: 10.1038/ng0393-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irwin S W, Averil N, Cheng C Y, Schryvers A B. Preparation and analysis of isogenic mutants in the transferrin receptor protein genes, tbpA and tbpB, from Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:1125–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klebba P E, Rutz J M, Liu J, Murphy C K. Mechanisms of TonB-catalyzed iron transport through the enteric bacterial cell envelope. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1993;25:603–611. doi: 10.1007/BF00770247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Legrain M, Mazarin V, Irwin S W, Bouchon B, Quentin-Millet M J, Jacobs E, Schryvers A B. Cloning and characterization of Neisseria meningitidis genes encoding the transferrin-binding proteins Tbp1 and Tbp2. Gene. 1993;130:73–80. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90348-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis L A, Dyer D W. Identification of an iron-regulated outer membrane protein of Neisseria meningitidis involved in the utilization of hemoglobin complexed to haptoglobin. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1299–1306. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1299-1306.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis L A, Gray L, Wang Y P, Roe B A, Dyer D W. Molecular characterization of hpuAB, the hemoglobin-haptoglobin utilization operon of Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:737–749. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2501619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis L A, Rohde K, Gipson M, Behrens B, Gray E, Toth S I, Roe B A, Dyer D W. Identification and molecular analysis of lbpBA, which encodes the two-component meningococcal lactoferrin receptor. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3017–3023. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.3017-3023.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nachamkin I, Cannon J G, Mittler R S. Monoclonal antibodies against Neisseria gonorrhoeae: production of antibodies directed against a strain-specific cell surface antigen. Infect Immun. 1981;32:641–648. doi: 10.1128/iai.32.2.641-648.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nassif X, Puaoi D, So M. Transposition of Tn1545-Δ3 in the pathogenic neisseriae: a genetic tool for mutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2147–2154. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.7.2147-2154.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pettersson A, Klarenbeek V, van Deurzen J, Poolman J T, Tommassen J. Molecular characterization of the structural gene for the lactoferrin receptor of the meningococcal strain H44/76. Microb Pathog. 1994;17:395–408. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pettersson A, Maas A, Tommassen J. Identification of the iroA gene product of Neisseria meningitidis as a lactoferrin receptor. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1764–1766. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1764-1766.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Postle K. TonB and the Gram-negative dilemma. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:2019–2025. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quinn M L, Weyer S J, Lewis L A, Dyer D W, Wagner P M. Insertional inactivation of the gene for the meningococcal lactoferrin binding protein. Microb Pathog. 1994;17:227–237. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schryvers A B, Morris L J. Identification and characterization of the human lactoferrin-binding protein from Neisseria meningitidis. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1144–1149. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1144-1149.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schryvers A B, Morris L J. Identification and characterization of the transferrin receptor of Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 1988;2:281–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stojiljkovic I, Hantke K. Haemin uptake systems of Yersinia enterocolitica: similarities with other TonB-dependent systems in Gram-negative bacteria. EMBO J. 1992;11:4359–4367. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stojiljkovic I, Hantke K. Transport of haemin across the cytoplasmic membrane through a haemin-specific periplasmic binding protein-dependent transport system in Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:719–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stojiljkovic I, Hwa V, Martin L de S, O’Gaora P, Nassif X, Heffron F, So M. The Neisseria meningitidis haemoglobin receptor: its role in iron utilization and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:531–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stojiljkovic I, Larson J, Hwa V, Anic S, So M. HmbR outer membrane receptors of pathogenic Neisseria spp.: iron-regulated, hemoglobin-binding proteins with a high level of primary structure conservation. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4670–4678. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4670-4678.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stojiljkovic I, Srinivasan N. Neisseria meningitidis tonB, exbB, and exbD genes: Ton-dependent utilization of protein-bound iron in neisseriae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:805–812. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.805-812.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]