Abstract

Objective:

Racial disparities in adolescent sleep duration have been documented, but pathways driving these disparities are not well understood. This study examined whether neighborhood and household environments explained racial disparities in adolescent sleep duration.

Methods:

Participants came from Waves I and II of Add Health (n=13,019). Self-reported short sleep duration was defined as less than the recommended amount for age (<9 hours for 6-12 years, <8 hours for 13-18 years, and <7 hours for 18-64 years). Neighborhood factors included neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage, perceived safety and social cohesion. Household factors included living in a single parent household and household socioeconomic status (HSES). Structural equation modeling was used to assess mediation of the neighborhood and household environment in the association between race/ethnicity and short sleep duration.

Results:

Only HSES mediated racial disparities, explaining non-Hispanic (NH) African American-NH White (11.6%), NH American Indian-NH White (9.9%), and Latinx-NH White (42.4%) differences. Unexpectedly, higher HSES was positively associated with short sleep duration.

Conclusion:

Household SES may be an important pathway explaining racial disparities in adolescent sleep duration. Future studies should examine mechanisms linking household SES to sleep and identify buffers for racial/ethnic minority adolescents against the detrimental impacts that living in a higher household SES may have on sleep.

Keywords: Sleep, Race, Ethnicity, Sex, Gender, Health status disparities, Life span

1. Introduction

A large body of literature has linked short sleep duration (ranging from < 6 hours to < 8 hours) to obesity, type-2 diabetes, poorer mental health, and engagement in injury related behaviors such as tobacco use and drunk driving among adolescents [1-4]. Short sleep duration is highly prevalent among U.S. adolescents with as high as 60% of middle school and 70% of high school students reporting sleeping less than the recommended amount by age based on guidelines set by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (<9 hours for age 6-12 years and <8 hours for age 13-18 years) [5]. Furthermore, racial disparities in short sleep duration among adolescents has been well documented with racial/ethnic minority adolescents generally reporting shorter sleep duration than non-Hispanic White adolescents [6-8]. The reasons for these disparities are unclear. Understanding the mechanisms driving these disparities among adolescents can help to inform interventions to reduce these disparities in sleep duration and consequently health outcomes among adolescents.

The neighborhood context may play an important role in explaining racial differences in sleep duration among adolescents. Previous studies suggests that living in neighborhoods of higher socioeconomic disadvantage is associated with shorter sleep duration among children and adolescents [9-12]. Socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods often have fewer health promoting resources (e.g. recreational facilities, sidewalks, and healthy food stores) that could help encourage healthy sleep behaviors (e.g., physical activity, reduced sedentary behaviors such as screen time, and healthy diets) subsequently resulting in more sleep [13,14]. In addition, disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to have greater noise (e.g., traffic, police sirens, and construction work) and air pollution (e.g., PM2.5 and nitrogen oxides) that may contribute to less sleep through arousals, inflammatory pathways, and stress responses [15-17]. Moreover, neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage is correlated with poorer social environments such as greater neighborhood disorder (i.e., lack of order and social control within a community characterized by indicators including but not limited to vandalism, littering and/or loitering, and high-risk substance use), less safety, and lower social cohesion (i.e., strength of relationships and the sense of solidarity among residents in a neighborhood) [18-20] which are associated with shorter sleep duration among adolescents [21-24]. Living in these stressful neighborhood social conditions may result in hypervigilance and psychological distress that lead to physiologic hormones that interfere with sleep [25,26]. Furthermore, these neighborhood environments are patterned by race/ethnicity with racial/ethnic minorities being more likely to live in neighborhoods of lower SES and poorer social environments [27]. However, studies examining whether racial differences in neighborhood environments exacerbate or mitigate racial disparities in sleep duration among adolescents are lacking.

In addition to the neighborhood SES, household-level factors such as household SES may be an important contributor to racial disparities in sleep among adolescents. Living in households of lower SES is associated with shorter sleep duration among adolescents [28]. Parents with lower SES are more likely to be shift workers, work multiple jobs, and live in more noisy and crowded spaces interfering with the ability to establish healthy sleep habits for their children such as consistent bedtimes that are beneficial for sleep [29-31]. Additionally, adolescents of lower SES have less access to health care to prevent and/or treat medical conditions (e.g., asthma and obesity) that can negatively influence sleep. Household SES varies by race/ethnicity with racial/ethnic minority adolescents being more likely to have lower household SES than their non-Hispanic White peers [32]. Thus, household SES may be a contributor to the documented adolescent sleep disparities. However, research examining whether household SES explains racial disparities in adolescent sleep duration remain sparse.

Another household factor that may contribute to racial disparities in adolescent sleep is living in a single parent household. There is evidence to suggest that living in a single parent household is associated with shorter sleep duration [33,34]. One component of living in a single parent household that may explain shorter sleep duration is that it could reflect household SES as those living in a single parent household may have lower income than a two-parent household. Furthermore, living in a single parent household may reflect instability of the home environment that could inhibit sleep [33]. For instance, previous literature have found greater parent-child conflict among single parent families and an association between parent-child conflict and sleep problems among adolescents [35-37]. One explanation for this association is that optimal sleep is best facilitated in an environment perceived as safe and free of threat, thus repeated exposure to feelings of instability in the home environment may increase vigilance and interfere with sleep [38]. Research suggests that racial/ethnic minority adolescents may be more likely to live in single parent households in comparison to non-Hispanic White adolescents [39]. Studies have not investigated whether living in a single parent household contributes to racial differences in adolescent sleep duration.

The primary purpose of this study is to simultaneously examine whether neighborhood (e.g. neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage, safety, and social cohesion) and household environments (e.g. household SES and single parent household) explain racial disparities in sleep duration among U.S. adolescents. Using structural equation modeling, the hypotheses being tested are: 1) racial/ethnic minority adolescents are more likely to have shorter sleep duration than White adolescents, 2) living in adverse neighborhood and household environments will be positively associated with short sleep duration, and 3) racial/ethnic minority adolescents will be more likely to live in these stressful neighborhood and household environments which will lead to greater reports of short sleep duration compared to White adolescents.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

The data for this study are from Waves I and II of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). Add Health is an ongoing longitudinal, nationally representative, school-based study of adolescent health behaviors and their outcomes during adulthood. Details about the study design and procedures have been published elsewhere [40]. In brief, a school-based study design was used in which 80 high schools and 52 middle schools from the US were sampled and stratified by region of country, urbanicity, school size, school type, and ethnicity. In 1994-1995, an in-school questionnaire on topics such as school extracurricular activities, friendships, and health status were administered to 90,118 students between grades 7-12 with parental and student consent. A subset of those that completed the in-school questionnaire and those that did not complete the questionnaire but were on the school roster (n=20,745) were interviewed in their homes from 1994-1995 which formed Wave I (mean age: 16 years) of the study. Wave II (1996; mean age: 16 years) was conducted a year later and consists of a subset of Wave I participants (n=14,738). Sampling weights were constructed by the Add Health study team to be applied in analyses allowing for nationally representative estimates. Weights were unable to be constructed for participants selected out of the sampling frame for Add Health sub studies [41]. This study included only those who participated in both Waves of data collection and had complete sample weights (n=13,568). Those who did not identify as African American, American Indian, Asian, Hispanic, or White (n=124) and were long sleepers defined as sleep duration greater than the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s (AASM) recommended amount of sleep by age (>12 hours for 6-12 years, >10 hours for 13-18 year, and >9 hours for 18-64 years) (n=405) were excluded due to their small sample sizes providing a final analytic sample of 13,019. Add Health was approved by the institutional review board of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and written consent forms were obtained from adolescents and their parents.

2.2. Neighborhood Environment

Data on neighborhood environmental factors were obtained from Wave I. Participant home addresses at Wave I were geocoded using the following sources in order of priority: 1) street-segment matches from commercial geographic information system (GIS) databases; 2) global positioning system (GPS) units, when street segments were not available; 3) a ZIP+4/ZIP+2 or a 5 digit zip centroid match when neither GIS or GPS data were available; and 4) respondent’s geocoded school location [42]. The home addresses were then linked to block, group, tract, and county information from the 1990 US Census and the National Archive of Criminal Justice Data for crime information [43]. Those with missing geocoded data, missing source data, and unstable estimates due to small sample sizes were coded as missing (n=306). In addition, in-home interviews with adolescent participants were conducted in Wave I to collect information on neighborhood characteristics such as perceived safety and social cohesion and are further described below. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage was assessed with a summary score constructed by standardizing and summing the following five census tract measures that have been used in prior Add Health research: proportions of female-headed households, individuals living below the poverty threshold, individuals receiving public assistance, adults with less than a high school education, and adults who were unemployed [44,45]. A higher summary score represented greater disadvantage and was modeled continuously. Perceived neighborhood safety was assessed based on adolescent report of yes or no to the question “Do you usually feel safe in your neighborhood?” and modeled as a binary variable. Neighborhood social cohesion was evaluated using a summary score from a prior Add Health studies based on adolescent report of yes or no to the following three items: 1)” You know most of the people in your neighborhood in the past month”; 2) “You have stopped on the street to talk with someone who lives in your neighborhood”; and 3) “People in this neighborhood look out for each other” [46,47]. Responses (yes=1, no=0) were summed to generate a score ranging from 0 to 3. The summary score was modeled as a continuous variable with a higher score representing greater social cohesion.

2.3. Household Environment

Information on household environment measures were obtained from Wave I. During Wave I, an in-home interview was conducted with the adolescent and their parent to ascertain information on household sociodemographic characteristics. For this study, household environment measures included living in a single parent household and household SES. Living in a single parent household was determined by adolescent report of family structure and was modeled as a dichotomous variable [48]. Household SES was assessed by a summary measure including parental education, parental occupation, and household income. The highest parental education level was used and categorized in three groups: 1) less than high school, or high school graduate or vocational school, 2) some college, or 3) college graduate or graduate education. The highest parental occupational level was selected and classified as: 1) service industry, transportation, construction or military; 2) technical, office worker, sales; or 3) professional or manager. Household income was categorized into tertiles as low, medium, and high. A summary score was created using a weighted average of the sum of the parental education, parental occupation, and household income resulting in a score ranging from 0 to 2 with a higher score representing higher household SES.

2.4. Sleep Duration

Sleep duration data was obtained from Wave II and ascertained from adolescent participants by asking “How many hours of sleep do you usually get?” in which they were only allowed to respond in whole hours per day. Responses were categorized based on the recommended amount of sleep for age by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM): 9-12 hours for 6-12 years of age, 8-10 hours for 13-18 years of age, and 7-9 hours for 18-64 years of age [49,50]. Sleep was dichotomized as either short sleep duration (less than the amount recommended by age) or recommended sleep duration (within the recommended range by age).

2.5. Race/ethnicity

Participants were asked to provide a yes or no response to the question “Are you of Hispanic or Latino origin?” Following that question, participants were asked “What is your race?” with White, Black or African American, American Indian or Native American, Asian or Pacific Islander, or Other as possible choices and the ability to indicate more than one race. Based on recommendations by Add Health researchers [51], those that responded with yes to being of Hispanic or Latino origin were designated as Hispanic for their race/ethnicity and excluded from any race category that was selected. If participants selected "black or African American" and any other race, they were designated as African American for their race/ethnicity, and eliminated from the other selected race categories. The process was repeated for the remaining race categories in the following order: Asian, American Indian, and White. The race/ethnicity variable consisted of non-Hispanic African American, non-Hispanic American Indian, non-Hispanic Asian, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic White. Henceforth, the race/ethnicity groups will be referred to as African American, American Indian, Asian, Latinx, and White.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Study sample characteristics were examined by race/ethnicity using PROC SURVEY procedures in SAS 9.4 to account for complex sampling weights [52]. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine neighborhood and household environmental factors as mediators in the association between race/ethnicity and short sleep duration adjusting for self-reported sex (male vs. female) and age. An attempt was made to model the neighborhood and household environment as latent constructs mediating the association between race/ethnicity and short sleep, but did not meet the guidelines for identifiability [53]. Therefore, each individual neighborhood and household measure was modeled as a mediator in the SEM. White adolescents were the reference group in all pathways involving comparisons between racial/ethnic groups. The SEMs accounted for complex sampling weights and were conducted with MPlus v8.4 using the weighted least squares means and variance estimator (WLSMV) to obtain the standardized probit coefficients and standard errors (SE) for the total effect (TE), direct effect (DE), and indirect effect (IDE) of each pathway [54]. Missing data was addressed using the default missing data procedure implemented for WLSMV in MPlus [54]. Covariance of error terms between each neighborhood measure and separately each household variable were included to account for potential collinearity. Modification indices were examined and covariance of error terms between the neighborhood and household characteristics with indices greater than 10 were included to improve model fit. Model fit was assessed with root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Acceptable model fit is indicated by RMSEA<0.06, CFI>0.95, and SRMR<0.08 [55].

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

Study sample characteristics by race/ethnicity are shown in Table 1. Overall, the mean age was 15.0 years (SE=0.11), 49.8% were female, 41.6% reported short sleep duration, and 15.6%, 2.1%, 4.0%, 12.3%, and 66.1% were African American, American Indian, Asian, Latinx, and White respectively. All characteristics significantly differed by race/ethnicity (p<.001) except sex and age. African American, American Indian and Latinx adolescents were more likely to live in neighborhoods with greater socioeconomic disadvantage compared to Asian and White adolescents. A smaller percentage of African American and Latinx adolescents reported living in a safe neighborhood compared to their American Indian, Asian, and White peers. On average, African Americans and White adolescents reported greater neighborhood social cohesion compared to all other racial/ethnic groups. In terms of household factors, a higher proportion of African American, American Indian, and Latinx adolescents reported lower household SES than Asian and White adolescents. A higher proportion of African American and Hispanic adolescents reported living in a single parent household compared with their peers of other racial/ethnic groups. Furthermore, African American adolescents had the highest prevalence of short sleep duration (47.1%), followed by Asian (46.5%), American Indian (45.1%), Latinx (40.7%), and White (40.1%) adolescents.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Race/Ethnicity from Waves I and II of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, United States, 1994-96

| Characteristics | Total (N=13,019) |

African American (N= 2,790; 15.6%) |

American Indian (N=240; 2.1%) |

Asian (N=928; 4.0%) |

Latinx (N=2,210; 12.3%) |

White (N=6,851; 66.1%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SE) | 15.04 (0.11) | 15.19 (0.19) | 14.89 (0.17) | 15.23 (0.27) | 15.14 (0.21) | 14.98 (0.13) |

| Sex, Female | 49.8% | 51.3% | 43.1% | 47.6% | 48.8% | 50.0% |

| Household Socioeconomic Status, mean (SE) | 0.88 (0.03) | 0.66 (0.04) | 0.74 (.05) | 0.94 (0.06) | 0.55 (0.03) | 0.99 (0.03) |

| Single parent household | 23.6% | 47.0% | 19.4% | 15.5% | 24.9% | 18.4% |

| Neighborhood Socioeconomic Disadvantage, mean (SE) | 21.65 (0.92) | 32.5 (0.96) | 23.7 (2.26) | 19.07 (1.34) | 26.19 (1.29) | 18.34 (0.98) |

| Neighborhood Perceived as Safe | 89.8% | 82.7% | 88.3% | 88.7% | 82.8% | 92.8% |

| Neighborhood Social Cohesion, mean (SE) | 2.28 (0.02) | 2.38 (0.03) | 2.20 (0.07) | 1.90 (0.07) | 2.11 (0.03) | 2.31 (0.03) |

| Short sleep duration | 41.6% | 47.1% | 45.1% | 46.5% | 40.7% | 40.0% |

Abbreviations: SE=Standard Error

Note: Results accounted for Add Health sampling weights; p<0.001 for comparison of all characteristics except for age and sex (p’s>0.05)

3.2. Structural Equation Models

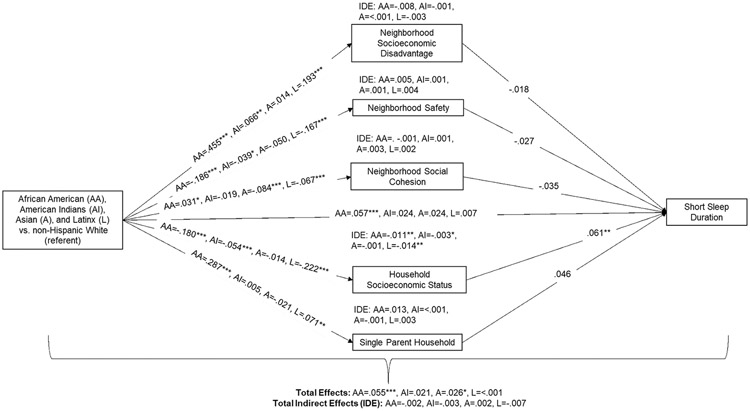

The simplified version of the results for each pathway without the SE and exact p-values are shown in Fig. 1. The estimates, SE, and p-values for the total, direct, and indirect effects of the SEM comparing short sleep duration for African American, Asian, American Indian, and Latinx to White adolescents are shown in Table 2. Model fit statistics suggested acceptable model fit (RMSEA= .014, CFI= .996, and SRMR=.025).

Fig. 1.

Structural Equation Model of the Association between Race/ethnicity and Short Sleep Duration as Mediated by Neighborhood and Household Environmental Factors. Note: Paths emanating from race/ethnicity represent a comparison of each minority group (African American, Asian, American Indian and Latinx) to non-Hispanic White. All variables were modeled simultaneously and adjusted for sex and age. Total effects, indirect effects, and direct effects were estimated for all pathways. Standardized estimates are shown in each pathway. *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001

Table 2.

Results from Structural Equation Model of the Association between Race/ethnicity and Short Sleep Duration as Mediated by Neighborhood and Household Environmental Factors

| Pathways (n=13,019) | β | SE | p- value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effects: | |||

| Race/ethnicity → Short Sleep Duration | |||

| African American | .055 | .014 | <.001 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | .021 | .013 | .095 |

| Asian | .026 | .013 | .047 |

| Latinx | <.001 | .015 | .994 |

| Direct Effects: | |||

| Race/ethnicity → Short Sleep Duration | |||

| African American | .057 | .016 | <.001 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | .024 | .013 | .058 |

| Asian | .024 | .013 | .074 |

| Latinx | .007 | .015 | .648 |

| Race/ethnicity →Neighborhood Socioeconomic Disadvantage | |||

| African American | .455 | .028 | <.001 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | .066 | .021 | .002 |

| Asian | .014 | .026 | .583 |

| Latinx | .193 | .035 | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity → Neighborhood Safety | |||

| African American | −.186 | .023 | <.001 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | −.039 | .020 | .049 |

| Asian | −.050 | .026 | .051 |

| Latinx | −.167 | .021 | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity →Neighborhood Social Cohesion | |||

| African American | .031 | .015 | .042 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | −.019 | .010 | .062 |

| Asian | −.084 | .012 | <.001 |

| Latinx | −.067 | .012 | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity → Household Socioeconomic Status | |||

| African American | −.180 | .028 | <.001 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | −.054 | .014 | <.001 |

| Asian | −.014 | .016 | .397 |

| Latinx | −.222 | .021 | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity → Single Parent Household | |||

| African American | .287 | .020 | <.001 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | .005 | .020 | .819 |

| Asian | −.021 | .016 | .195 |

| Latinx | .071 | .021 | .001 |

| Neighborhood Socioeconomic Disadvantage → Short Sleep Duration | −.018 | .020 | .373 |

| Neighborhood Safety → Short Sleep Duration | −.027 | .029 | .359 |

| Neighborhood Social Cohesion → Short Sleep Duration | −.035 | .018 | .058 |

| Household Socioeconomic Status→ Short Sleep Duration | .061 | .021 | .004 |

| Single Parent Household→ Short Sleep Duration | .046 | .026 | .078 |

| Indirect Effects: | |||

| Total: | |||

| Race/ethnicity → Short Sleep Duration | |||

| African American | −.002 | .011 | .863 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | −.003 | .002 | .181 |

| Asian | .002 | .002 | .337 |

| Latinx | −.007 | .006 | .227 |

| Specific: | |||

| Race/ethnicity → Neighborhood Socioeconomic Disadvantage → Short Sleep Duration | |||

| African American | −.008 | .009 | .375 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | −.001 | .001 | .397 |

| Asian | <.001 | <.001 | .610 |

| Latinx | −.003 | .004 | .378 |

| Race/ethnicity → Neighborhood Safety → Short Sleep Duration | |||

| African American | .005 | .006 | .371 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | .001 | .001 | .405 |

| Asian | .001 | .002 | .423 |

| Latinx | .004 | .005 | .366 |

| Race/ethnicity → Neighborhood Social Cohesion → Short Sleep Duration | |||

| African American | −.001 | .001 | .163 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | .001 | .001 | .236 |

| Asian | .003 | .002 | .085 |

| Latinx | .002 | .001 | .084 |

| Race/ethnicity → Household Socioeconomic Status → Short Sleep Duration | |||

| African American | −.011 | .004 | .007 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | −.003 | .001 | .017 |

| Asian | −.001 | .001 | .427 |

| Latinx | −.014 | .005 | .007 |

| Race/ethnicity → Single Parent Household → Short Sleep Duration | |||

| African American | .013 | .007 | .071 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | <.001 | .001 | .818 |

| Asian | −.001 | .001 | .327 |

| Latinx | .003 | .002 | .081 |

Racial/Ethnic Differences in Short Sleep Duration

African American (TE: β=.055, SE=.014, p<.001) and Asian (TE: β=.026, SE=.013, p=.047) adolescents were more likely to have short sleep duration than White adolescents. There were no statistically significant Latinx-White and American Indian-White differences.

3.2.1. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Neighborhood and Household Environments

African American adolescents were more likely to live in neighborhoods with greater socioeconomic disadvantage (DE: β=.455, SE=.028, p<.001), less safety (DE: β=−.186, SE=.023, p<.001), and more social cohesion (DE: β=.031, SE=.015, p=.042) than White adolescents. American Indian adolescents were more likely to live in greater neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage (DE: β=.066, SE=.021, p=.002) and less safety (DE: β=−.039, SE=.020, p=.049) compared with White adolescents, but there were no statistically significant differences in social cohesion. Asian adolescents were more likely to live in neighborhoods with less social cohesion than White adolescents (DE: β=−.084, SE=.012, p<.001), but there were no other statistically significant neighborhood differences. Compared to White adolescents, Latinx adolescents reported living in neighborhoods of greater socioeconomic disadvantage (DE: β=.193, SE=.035, p<.001), lower safety (DE: β=−.167, SE=.021, p<.001), and less social cohesion (DE: β=−.067, SE=.012, p<.001).

African American adolescents were more likely to live in lower household SES (DE: β=−.180, SE=.028, p<.001) and to live in a single parent household (DE: β=.287, SE=.020, p<.001) than their White peers. American Indian adolescents were more likely to have lower household SES compared to White adolescents (DE: β=−.054, SE=.014, p<.001), but no significant differences of living in a single parent household between these two groups. There were no significant differences in household characteristics between Asian and White adolescents. Latinx adolescents lived in lower household SES (DE: β=−.222, SE=.021, p<.001) and were more likely to live in a single parent household (DE: β=.071, SE=.021, p=.001) than White adolescents.

3.2.2. Neighborhood and Household Characteristics on Short Sleep Duration

Higher household SES (DE: β=.069, SE=.020, p=.001) was significantly associated with greater likelihood of short sleep. There was no statistically significant association between living in a single parent household and short sleep duration or between any of the neighborhood characteristics and short sleep duration.

3.2.3. Mediation of Neighborhood and Household Environment

There were no significant mediation by the neighborhood environment in the association between race/ethnicity and short sleep duration (IDE: p’s>.05). Household SES mediated 11.6% of African American-White (IDE: β=−.011, SE=.004, p=.007), 9.9% of American Indian-White (IDE: β=−.003, SE=.001, p=.017), and 42.4% of Latinx-White short sleep duration differences (IDE: β=−.014, SE=.005, p=.007). That is, the difference in short sleep duration between each racial/ethnic group compared to White adolescents is increased by having higher household SES. However, there were no indirect effects for living in a single parent household. Furthermore, differences in short sleep duration between Asian and White adolescents were not significantly mediated by any of the household characteristics.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is one of first studies to examine contributors to racial disparities in sleep duration among adolescents. This study comprised of racial groups beyond African American, Latinx, and White adolescents and included Asian and American Indian adolescents. In this study, African American, American Indian, and Asian adolescents were more likely to have short sleep duration than White their peers. Racial/ethnic minority adolescents were more likely to live in adverse neighborhood environments than White adolescents. Contrary to our hypotheses, these neighborhood characteristics were not related to short sleep duration and did not explain the racial differences in sleep duration between racial/ethnic minority groups and White adolescents. Furthermore, results from this study show that African American, Latinx, and American Indian adolescents were more likely to live in adverse household environments than Asian and White adolescents. Living in a single parent household was not related to sleep duration and unexpectedly living in lower SES households was related to a lower likelihood of short sleep duration. Results further suggest that household SES partially contributed to African American-White, American Indian-White, and Latinx-White differences. That is, living in a lower household SES for these racial/ethnic minority groups decreased differences in sleep duration compared to White adolescents

Consistent with prior studies, our study found a higher proportion of short sleep duration among African American, American Indian, and Asian compared to White adolescents [5,6]. However, our results did not indicate sleep duration differences between Latinx and White adolescents. Findings from prior studies comparing sleep duration between Latinx and White adolescents have been mixed with Latinx reporting shorter or longer sleep duration than Whites [56-61]. These contradictory results could be due to differences in the study population. Latinx ethnicity in some studies, including the current study, were comprised of various Hispanic subgroups (e.g., Puerto Ricans, Mexican Americans, and Cuban Americans) whereas other studies assessed individual ethnic groups (e.g. Mexican Americans) [7,56,58,62]. The diverse sociocultural context of Hispanic subgroups (e.g., migration histories and levels of acculturation) may differentially influence their sleep and may explain the various Latinx-White disparity findings [63-65]. Furthermore, the differences in the definition of short sleep duration may explain the contrasting results across studies. For instance, a study from the Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance Survey that uses a one-item question to assess sleep found no significant Hispanic-White differences in short sleep duration that was defined similar to this study using the AASM guidelines [5]. Whereas another study using data from a nationally representative sample of 8th, 10th and 12th graders with a one-item question assessment of sleep, found that Hispanics were more likely than White adolescents to have inadequate sleep which was defined as less than 7 hours [61]. Additionally, there are variations in the measurement of sleep across studies in which some studies used objective measures of sleep duration (e.g. actigraphy and polysomnography), while others use self-reported subjective measures such as parent report or time diaries. Studies conducted with actigraphy and polysomnography generally have found no significant Hispanic-White differences in sleep duration among adolescents [7,57,66,67]. Inconsistent results were more common among studies with self-reported sleep measures. For instance, a study of children in Tucson, Arizona [57] using parent report found that Hispanic adolescents reported shorter sleep duration; while a study from the Child Development Supplement of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics using a time diary survey found greater sleep duration among Hispanic compared to White adolescents [60].

Similar to our findings, some studies among adolescents found null associations between neighborhood factors and sleep duration [21,68]. However, other studies among adolescents have found associations between neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation, lack of perceived safety and social fragmentation with shorter sleep duration [10-12,21-24]. The discrepancies between study results could be due to the differences in measurement of the neighborhood characteristics such as the use of different census measures for assessment of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and varying scales to measure safety and social cohesion. Furthermore, the differences in results across studies could be the measurement of sleep duration in which some studies assessed sleep duration with actigraphy and/or self-reported sleep duration based on the sleep and wake time whereas our study used a one-item question with responses in whole hours.

Contrary to our hypothesis, living in a single parent household was not significantly associated with short sleep duration. A prior study among Black and White high school students by Troxel et al., found that living in a single parent household was associated with shorter actigraphy-assessed weekend sleep duration [33]. In the Add Health study, sleep duration was self-reported and not reported separately for weekday and weekend in Waves I and II, which precluded us from examining whether the results may have differed based on weekday and weekend sleep and comparing the results between studies.

A few studies conducted outside of the U.S. (e.g., China, India, and Turkey) [69-74] have found shorter sleep duration among higher household SES adolescents citing heavier homework demands, academic pressures, and greater access to participation in extracurricular activities (e.g., sports and private tutoring) as some of the factors explaining shorter sleep duration [75-77]. This may be the case for this study since Add Health is a school-based sample where academic pressures and participation in extracurricular activities may be more salient factors for adolescents in school compared to those not enrolled. Furthermore, these results are aligned with prior literature indicating that racial/ethnic minority adolescents may benefit less from being of higher household SES when compared to White adolescents [78-80]. Prior studies suggest that racial/ethnic minority adolescents of higher SES may be more likely to live in areas and attend schools that have predominantly White students where they experience heightened discrimination [81-84]. These experiences of discrimination may result in shorter sleep duration [85-87].

Other studies conducted among U.S. adolescents contradict our findings in which lower household SES was associated with shorter sleep duration [88-90]. The differences in results could be due to the use of actigraphy assessed sleep in these studies [88-90] whereas our study was limited to self-reported sleep in whole hours. In addition, there were variations in the measurement of household SES in which some of these studies included indicators of SES individually [88,89] instead of a composite measure. Furthermore, the discrepancy in findings may be explained by the differences in the age of the study samples in which previous studies included mainly younger adolescents in middle school [88-90] whereas our study consisted of mostly high school students. This may have led to differences in results because of the greater academic and social pressures among high school compared to middle school students.

There are at least three strengths to this study. First, this is one of the first studies to formally test neighborhood and household characteristics as contributors to racial disparities in sleep duration comparing African American, Asian, Latinx, and American Indian to White adolescents. Second, the analyses simultaneously modeled both household and neighborhood characteristics, which allowed for the decomposition of specific direct and indirect effects and accounted for the potential correlation between these variables. Finally, the study cohort was large, racially/ethnically diverse, and nationally representative which allows for greater generalizability.

Despite the strengths of this study, the results should be considered in the context of the potential limitations. Although the study attempted to include comprehensive measures of the neighborhood context, aggregate data may not represent individual level data and there may be other factors at the neighborhood level not captured in this study, such as measures of neighborhood disorder, crime data, and physical environment (e.g. noise, walkability, air pollution) that may contribute to racial disparities in sleep among adolescents [13]. Similarly, there are other household level factors such as parental sleeping habits, traumatic life events (e.g. death in family), and caregiver stress that may explain racial differences in sleep [91-95]. In addition, studies comparing self-report to actigraphy assessed sleep duration among adolescents have found that they tend to overestimate their sleep with moderate correlations between measures, suggesting that there may be random misclassification of sleep duration that resulted in the null findings [96,97]. Although there were null results in the association between neighborhood environmental measures with short sleep duration and mediation by these variables, there were numerous significant pathways detected between race/ethnicity and household environmental factors with short sleep duration and mediation by household SES. This indicates that the null findings in this study may not have been primarily due to the measurement error of self-reported sleep duration. Moreover, the adult literature has found that measurement error of self-reported sleep may vary by race/ethnicity [98,99]. Evidence of this bias in the adolescent literature is lacking, but may exist as studies have found racial differences in norms and attitudes about sleep that could influence the reporting of sleep duration [12,100]. Finally, the Add Health data used for this study was collected nearly three decades ago and cannot account for the historic changes (e.g., recessions and COVID-19 pandemic) and technological advancements (e.g., smartphones) that could affect the saliency of household and neighborhood factors on sleep duration for adolescents. However, racial/ethnic disparities in adolescent sleep and inequalities in these household and neighborhood factors that could differentially impact adolescent sleep across racial/ethnic groups persists. Thus, our findings are still relevant in providing insights to potential factors driving the current racial/ethnic disparities in adolescent sleep duration.

Given the large body of literature documenting significant racial disparities in adolescent sleep [6], understanding the contributors to these disparities is crucial for developing targeted interventions to mitigate these disparities. This study contributes to the early stages of trying to understand these pathways driving racial disparities in adolescent sleep duration and serve as a starting point for future research. Since household SES was found to be a potential pathway, it is important for future work to examine mechanisms linking varying levels of household SES to short sleep duration. In particular, future studies should be conducted within racial/ethnic groups to identify buffers that can reduce the harmful impacts that differing levels of household SES has on sleep. Knowledge on these mechanisms and buffers can be used to develop policies and intervention at the school level to improve sleep and reduce racial disparities in sleep.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (T32HL130025, R01HL125761, and F31HL151126-01A1). This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (https://addhealth.cpc.unc.edu).

References

- [1].McKnight-Eily LR, Eaton DK, Lowry R, Croft JB, Presley-Cantrell L, Perry GS. Relationships between hours of sleep and health-risk behaviors in US adolescent students. Prev Med 2011;53(4-5):271–3. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.06.020. Epub 2011/08/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Miller MA, Kruisbrink M, Wallace J, Ji C, Cappuccio FP. Sleep duration and incidence of obesity in infants, children, and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep 2018;41(4). 10.1093/sleep/zsy018. Epub 2018/02/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Dutil C, Chaput JP. Inadequate sleep as a contributor to type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents. Nutrition & Diabetes 2017;7(5). 10.1038/nutd.2017.19. e266–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wheaton AG, Olsen EO, Miller GF, Croft JB. Sleep Duration and Injury-Related Risk Behaviors Among High School Students–United States, 2007-2013. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2016;65(13):337–41. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6513a1. Epub 2016/04/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wheaton AG, Jones SE, Cooper AC, Croft JB. Short Sleep Duration Among Middle School and High School Students — United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67(3):85–90. ;67(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Guglielmo D, Gazmararian JA, Chung J, Rogers AE, Hale L. Racial/ethnic sleep disparities in US school-aged children and adolescents: a review of the literature. Sleep health 2018;4(1):68–80. 10.1016/j.sleh.2017.09.005. Epub 2018/01/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].James S, Chang AM, Buxton OM, Hale L. Disparities in adolescent sleep health by sex and ethnoracial group. SSM Popul Health 2020;11:100581. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100581. Epub 2020/05/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gillis BT, Shimizu M, Philbrook LE, El-Sheikh M. Racial disparities in adolescent sleep duration: Physical activity as a protective factor. Cultural diversity & ethnic minority psychology 2020. 10.1037/cdp0000422. Epub 2020/08/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Singh GK, Kenney MK. Rising Prevalence and Neighborhood, Social, and Behavioral Determinants of Sleep Problems in US Children and Adolescents, 2003-2012. Sleep Disorders 2013;2013. 10.1155/2013/394320. 394320-. Epub 05/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bagley EJ, Fuller-Rowell TE, Saini EK, Philbrook LE, El-Sheikh M. Neighborhood Economic Deprivation and Social Fragmentation: Associations With Children’s Sleep. Behavioral Sleep Medicine 2018;16(6):542–52. 10.1080/15402002.2016.1253011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sheehan C, Powers D, Margerison-Zilko C, McDevitt T, Cubbin C. Historical neighborhood poverty trajectories and child sleep. Sleep health 2018;4(2):127–34. 10.1016/j.sleh.2017.12.005. Epub 02/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].McLaughlin Crabtree V, Beal Korhonen J, Montgomery-Downs HE, Faye Jones V, O’Brien LM, Gozal D. Cultural influences on the bedtime behaviors of young children. Sleep Medicine 2005;6(4):319–24. 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Billings ME, Hale L, DA Johnson. Physical and Social Environment Relationship With Sleep Health and Disorders. Chest 2019. 10.1016/j.chest.2019.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mayne SL, Mitchell JA, Virudachalam S, Fiks AG, Williamson AA. Neighborhood environments and sleep among children and adolescents: A systematic review. Sleep medicine reviews 2021;57:101465. 10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Adkins A, Makarewicz C, Scanze M, Ingram M, Luhr G. Contextualizing Walkability: Do Relationships Between Built Environments and Walking Vary by Socioeconomic Context? Journal of the American Planning Association 2017;83(3):296–314. 10.1080/01944363.2017.1322527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Halperin D. Environmental noise and sleep disturbances: A threat to health? Sleep Sci 2014;7(4):209–12. 10.1016/j.slsci.2014.11.003. Epub 11/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tenero L, Piacentini G, Nosetti L, Gasperi E, Piazza M, Zaffanello M. Indoor/outdoor not-voluptuary-habit pollution and sleep-disordered breathing in children: a systematic review. Transl Pediatr 2017;6(2):104–10. 10.21037/tp.2017.03.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Diez Roux AV. Neighborhoods and Health: What Do We Know? What Should We Do? American journal of public health 2016;106(3):430–1. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ndjila S, Lovasi GS, Fry D, Friche AA. Measuring Neighborhood Order and Disorder: a Rapid Literature Review. Current environmental health reports 2019;6(4):316–26. 10.1007/s40572-019-00259-z. Epub 2019/11/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social Capital, Social Cohesion, and Health. 2014. [cited 8/13/2023]. In: Social Epidemiology [Internet]. Oxford University Press, [cited 8/13/2023]; [0].Available from: 10.1093/med/9780195377903.003.0008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pabayo R, Molnar BE, Street N, Kawachi I. The relationship between social fragmentation and sleep among adolescents living in Boston, Massachusetts. Journal of public health (Oxford, England) 2014;36(4):587–98. 10.1093/pubmed/fdu001. Epub 2014/02/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Meldrum RC, Jackson DB, Archer R, Ammons-Blanfort C. Perceived school safety, perceived neighborhood safety, and insufficient sleep among adolescents. Sleep Health 2018;4(5):429–35. 10.1016/j.sleh.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Philbrook LE, Buckhalt JA, El-Sheikh M. Community violence concerns and adolescent sleep: Physiological regulation and race as moderators. Journal of sleep research 2019. 10.1111/jsr.12897. e12897Epub 2019/07/31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Spilsbury JC, Babineau DC, Frame J, Juhas K, Rork K. Association between children’s exposure to a violent event and objectively and subjectively measured sleep characteristics: a pilot longitudinal study. Journal of sleep research 2014;23(5):585–94. 10.1111/jsr.12162. Epub 2014/05/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ribeiro AI, Amaro J, Lisi C, Fraga S. Neighborhood Socioeconomic Deprivation and Allostatic Load: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15(5):1092. 10.3390/ijerph15061092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kalmbach DA, Anderson JR, Drake CL. The impact of stress on sleep: Pathogenic sleep reactivity as a vulnerability to insomnia and circadian disorders. Journal of sleep research 2018;27(6). 10.1111/jsr.12710. e12710–e Epub 05/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kaiser P, Auchincloss AH, Moore K, Sánchez BN, Berrocal V, Allen N, et al. Associations of neighborhood socioeconomic and racial/ethnic characteristics with changes in survey-based neighborhood quality, 2000-2011. Health & Place 2016;42:30–6. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.08.001. Epub 09/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Felden ÉPG, Leite CR, Rebelatto CF, Andrade RD, Beltrame TS. Sleep in adolescents of different socioeconomic status: a systematic review. Revista Paulista de Pediatria (English Edition) 2015;33(4):467–73. 10.1016/j.rppede.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Adam EK, Snell EK, Pendry P. Sleep timing and quantity in ecological and family context: a nationally representative time-diary study. Journal of family psychology: JFP: journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43) 2007;21(1):4–19. 10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.4. Epub 2007/03/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Short MA, Gradisar M, Wright H, Lack LC, Dohnt H, Carskadon MA. Time for bed: parent-set bedtimes associated with improved sleep and daytime functioning in adolescents. Sleep 2011;34(6):797–800. 10.5665/sleep.1052. Epub 2011/06/02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pyper E, Harrington D, Manson H. Do parents’ support behaviours predict whether or not their children get sufficient sleep? A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2017;17(1). 10.1186/s12889-017-4334-4. 432-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Semega J, Kollar M, Creamer J, Abinash M. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2018. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Troxel WM, Lee L, Hall M, Matthews KA. Single-parent family structure and sleep problems in black and white adolescents. Sleep Med 2014;15(2):255–61. 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.10.012. Epub 2014/01/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Maume DJ. Social ties and adolescent sleep disruption. Journal of health and social behavior 2013;54(4):498–515. 10.1177/0022146513498512. Epub 2013/12/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Laursen B. Conflict Between Mothers and Adolescents in Single-Mother, Blended, and Two-Biological-Parent Families. Parent Sci Pract 2005;5(4):347–70. 10.1207/s15327922par0504_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Walker LJ, Hennig KH. Parent/child relationships in single-parent families. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science /Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement 1997;29(1):63–75. 10.1037/0008-400X.29.1.63. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kelly RJ, Marks BT, El-Sheikh M. Longitudinal relations between parent-child conflict and children’s adjustment: the role of children’s sleep. Journal of abnormal child psychology 2014;42(7):1175–85. 10.1007/s10802-014-9863-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Dahl RE, Lewin DS. Pathways to adolescent health sleep regulation and behavior. The Journal of adolescent health: official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine 2002;31(6 Suppl):175–84. 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00506-2. Epub 2002/12/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Livingston G. The Changing Profile of Unmarried Parents. Pew Research Center 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Harris KM, Halpern CT, Whitsel EA, Hussey JM, Killeya-Jones LA, Tabor J, et al. Cohort Profile: The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). International journal of epidemiology 2019;48(5). 10.1093/ije/dyz115. 1415-k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Chen P, Harris KM. Guidelines for Analyzing Add Health Data. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Boone-Heinonen J, Evenson KR, Song Y, Gordon-Larsen P. Built and socioeconomic environments: patterning and associations with physical activity in U.S. adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2010;7(1):45. 10.1186/1479-5868-7-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].U.S. Dept. Of Justice FBoI. Uniform Crime Reporting Program Data (United States: County-Level Detailed Arrest and Offense Data), 1992. Research I-uCfPaS. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research; 1992. editor. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Diez Roux AV, Merkin SS, Arnett D, Chambless L, Massing M, Nieto FJ, et al. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. The New England journal of medicine 2001;345(2):99–106. 10.1056/nejm200107123450205. Epub 2001/07/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Martin CL, Kane JB, Miles GL, Aiello AE, Harris KM. Neighborhood disadvantage across the transition from adolescence to adulthood and risk of metabolic syndrome. Health & place 2019;57:131–8. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.03.002. Epub 04/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Marley TL, Metzger MW. A longitudinal study of structural risk factors for obesity and diabetes among American Indian young adults, 1994-2008. Preventing Chronic Disease 2015;12. 10.5888/pcd12.140469. E69-E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Dawson CT, Wu W, Fennie KP, Ibanez G, Cano MA, Pettit JW, et al. Perceived neighborhood social cohesion moderates the relationship between neighborhood structural disadvantage and adolescent depressive symptoms. Health Place 2019;56:88–98. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.01.001. Epub 2019/02/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Harris KM, Hernandez DJ. The Health Status and Risk Behavior of Adolescents in Immigrant Families, editor. Children of Immigrants: Health, Adjustment, and Public Assistance. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. p. 286–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, Bliwise DL, Buxton OM, Buysse D, et al. Recommended Amount of Sleep for a Healthy Adult: A Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Sleep. 2015;38(6):843–4. 10.5665/sleep.4716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, Hall WA, Kotagal S, Lloyd RM, et al. Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine on the Recommended Amount of Sleep for Healthy Children: Methodology and Discussion. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(11):1549–61. 10.5664/jcsm.6288. Epub 2016/10/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Frequently Asked Questions: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Carolina Population Center; 2020. [cited 2020 5/31]. Available from: https://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/faqs/index.html#what-is-best-way-compute-race.

- [52].SAS/STAT® 15.1 User’s Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Bollen KA, Davis WR. Causal Indicator Models: Identification, Estimation, and Testing. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 2009;16(3):498–522. 10.1080/10705510903008253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Eighth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; (1998–2017). [Google Scholar]

- [55].Hu L-t, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 1999;6(1):1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Combs D, Goodwin JL, Quan SF, Morgan WJ, Parthasarathy S. Longitudinal differences in sleep duration in Hispanic and Caucasian children. Sleep Med 2016;18:61–6. 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.06.008. Epub 2015/08/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Goodwin JL, Silva GE, Kaemingk KL, Sherrill DL, Morgan WJ, Quan SF. Comparison between reported and recorded total sleep time and sleep latency in 6- to 11-year-old children: the Tucson Children’s Assessment of Sleep Apnea Study (TuCASA). Sleep and Breathing 2007;11(2):85–92. 10.1007/s11325-006-0086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Marczyk Organek KD, Taylor DJ, Petrie T, Martin S, Greenleaf C, Dietch JR, et al. Adolescent sleep disparities: sex and racial/ethnic differences. Sleep health 2015;1(1):36–9. 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.003. Epub 2015/03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Master L, Nye RT, Lee S, Nahmod NG, Mariani S, Hale L, Bidirectional, et al. Daily Temporal Associations between Sleep and Physical Activity in Adolescents. Scientific reports. 2019;9(1):7732. 10.1038/s41598-019-44059-9. Epub 2019/05/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Williams JA, Zimmerman FJ, Bell JF. Norms and trends of sleep time among US children and adolescents. JAMA pediatrics 2013;167(1):55–60. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Keyes KM, Maslowsky J, Hamilton A, Schulenberg J. The Great Sleep Recession: Changes in Sleep Duration Among US Adolescents, 1991–2012. Pediatrics 2015. 10.1542/peds.2014-2707. peds.2014-707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Roberts RE, Lee ES, Hemandez M, Solari AC. Symptoms of insomnia among adolescents in the lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Sleep 2004;27(4):751–60. 10.1093/sleep/27.4.751. Epub 2004/07/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Ebin VJ, Sneed CD, Morisky DE, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Magnusson AM, Malotte CK. Acculturation and interrelationships between problem and health-promoting behaviors among Latino adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health 2001;28(1):62–72. 10.1016/S1054-139X(00)00162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Miguez MJ, Bueno D, Perez C. Disparities in Sleep Health among Adolescents: The Role of Sex. Age, and Migration. Sleep Disorders. 2020;2020:5316364. 10.1155/2020/5316364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].McHale SM, Kim JY, Kan M, Updegraff KA. Sleep in Mexican-American adolescents: social ecological and well-being correlates. Journal of youth and adolescence 2011;40(6):666–79. 10.1007/s10964-010-9574-x. Epub 07/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Rao U, Hammen CL, Poland RE. Ethnic differences in electroencephalographic sleep patterns in adolescents. Asian journal of psychiatry 2009;2(1):17–24. 10.1016/j.ajp.2008.12.003. Epub 2009/12/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Malone SK, Zemel B, Compher C, Souders M, Chittams J, Thompson AL, et al. Characteristics Associated With Sleep Duration, Chronotype, and Social Jet Lag in Adolescents. The Journal of School Nursing 2015;32(2):120–31. 10.1177/1059840515603454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Troxel WM, Shih RA, Ewing B, Tucker JS, Nugroho A, D’Amico EJ. Examination of neighborhood disadvantage and sleep in a multi-ethnic cohort of adolescents. Health & place. 2017;45:39–45. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.03.002. Epub 03/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Seo WH, Kwon JH, Eun SH, Kim G, Han K, Choi BM. Effect of socio-economic status on sleep. Journal of paediatrics and child health. 2017;53(6):592–7. 10.1111/jpc.13485. Epub 2017/06/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Bapat R, van Geel M, Vedder P. Socio-Economic Status, Time Spending, and Sleep Duration in Indian Children and Adolescents. J Child Fam Stud 2017;26(1):80–7. 10.1007/s10826-016-0557-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Kim J, Noh JW, Kim A, Kwon YD. Demographic and Socioeconomic Influences on Sleep Patterns among Adolescent Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17(12). 10.3390/ijerph17124378. Epub 2020/06/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Arman AR, Ay P, Fis NP, Ersu R, Topuzoglu A, Isik U, et al. Association of sleep duration with socio-economic status and behavioural problems among schoolchildren. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway: 1992) 2011;100(3):420–4. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.02023.x. Epub 2010/09/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Hertog E, Zhou M. Japanese adolescents’ time use: The role of household income and parental education. Demographic research 2021;44:225–38. 10.4054/demres.2021.44.9. Epub 2021/06/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Zhang J, Li AM, Fok TF, Wing YK. Roles of parental sleep/wake patterns, socioeconomic status, and daytime activities in the sleep/wake patterns of children. J Pediatr 2010;156(4). 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.10.036. 606–12.e5 Epub 2009/12/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Luthar SS, Shoum KA, Brown PJ. Extracurricular involvement among affluent youth: a scapegoat for "ubiquitous achievement pressures"? Dev Psychol 2006;42(3):583–97. 10.1037/0012-1649.42.3.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Short MA, Gradisar M, Lack LC, Wright HR, Dewald JF, Wolfson AR, et al. A cross-cultural comparison of sleep duration between US And Australian adolescents: the effect of school start time, parent-set bedtimes, and extracurricular load. Health Educ Behav 2013;40(3):323–30. 10.1177/1090198112451266. Epub 09/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Xing Y. Restricted sleep among adolescents: prevalence, incidence, persistence, and associated factors. Behav Sleep Med 2011;9(1):18–30. 10.1080/15402002.2011.533991. Epub 2011/01/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Assari S, Preiser B, Lankarani MM, Caldwell CH. Subjective Socioeconomic Status Moderates the Association between Discrimination and Depression in African American Youth. Brain Sci 2018;8(4). 10.3390/brainsci8040071. Epub 2018/04/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Gordon-Larsen P, Adair LS, Popkin BM. The Relationship of Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Factors, and Overweight in U.S. Adolescents. Obesity Research 2003;11(1):121–9. 10.1038/oby.2003.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Mello D, Wiebe D. The Role of Socioeconomic Status in Latino Health Disparities Among Youth with Type 1 Diabetes: a Systematic Review. Current Diabetes Reports 2020;20(11):56. 10.1007/s11892-020-01346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Assari S, Gibbons FX, Simons R. Depression among Black Youth; Interaction of Class and Place. Brain Sci 2018;8(6):108. 10.3390/brainsci8060108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Assari S, Gibbons FX, Simons RL. Perceived Discrimination among Black Youth: An 18-Year Longitudinal Study. Behav Sci (Basel) 2018;8(5):44. 10.3390/bs8050044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Assari S. Does School Racial Composition Explain Why High Income Black Youth Perceive More Discrimination? A Gender Analysis. Brain Sci 2018;8(8):140. 10.3390/brainsci8080140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Colen CG, Ramey DM, Cooksey EC, Williams DR. Racial disparities in health among nonpoor African Americans and Hispanics: The role of acute and chronic discrimination. Soc Sci Med 2018;199:167–80. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.051. Epub 05/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Majeno A, Tsai KM, Huynh VW, McCreath H, Fuligni AJ. Discrimination and Sleep Difficulties during Adolescence: The Mediating Roles of Loneliness and Perceived Stress. Journal of youth and adolescence 2018;47(1):135–47. 10.1007/s10964-017-0755-8. Epub 11/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Bridget JG, Jacob EC, Whitney S-B, Taylor CR, Timothy DN. Perceived Discrimination and Adolescent Sleep in a Community Sample. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation. Journal of the Social Sciences 2018;4(4):43–61. 10.7758/rsf.2018.4.4.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Huynh VW, Gillen-O’Neel C. Discrimination and Sleep: The Protective Role of School Belonging. Youth & Society 2013;48(5):649–72. 10.1177/0044118X13506720. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Moore M, Kirchner HL, Drotar D, Johnson N, Rosen C, Redline S. Correlates of adolescent sleep time and variability in sleep time: the role of individual and health related characteristics. Sleep Med 2011;12(3):239–45. 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Marco CA, Wolfson AR, Sparling M. Azuaje A. Family socioeconomic status and sleep patterns of young adolescents. Behavioral Sleep Medicine 2011;10(1):70–80. 10.1080/15402002.2012.636298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].El-Sheikh M, Bagley EJ, Keiley M, Elmore-Staton L, Chen E, Buckhalt JA. Economic adversity and children’s sleep problems: multiple indicators and moderation of effects. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology. American Psychological Association 2013;32(8):849–59. 10.1037/a0030413. Epub 11/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Fuligni AJ, Tsai KM, Krull JL, Gonzales NA. Daily concordance between parent and adolescent sleep habits. The Journal of adolescent health: official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine 2015;56(2):244–50. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.013. Epub 2015/01/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Vidal Bustamante CM, Rodman AM, Dennison MJ, Flournoy JC, Mair P, McLaughlin KA. Within-person fluctuations in stressful life events, sleep, and anxiety and depression symptoms during adolescence: a multiwave prospective study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry.n/a(n/a). doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Schmeer KK, Tarrence J, Browning CR, Calder CA, Ford JL, Boettner B. Family contexts and sleep during adolescence. SSM - Population Health 2019;7:100320. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Hatch SL, Dohrenwend BP. Distribution of traumatic and other stressful life events by race/ethnicity, gender, SES and age: a review of the research. American journal of community psychology 2007;40(3-4):313–32. 10.1007/s10464-007-9134-z. Epub 2007/10/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Alfano CA, Smith VC, Reynolds KC, Reddy R, Dougherty LR. The Parent-Child Sleep Interactions Scale (PSIS) for Preschoolers: Factor Structure and Initial Psychometric Properties. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 2013;09(11):1153–60. 10.5664/jcsm.3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA, Acebo C, Seifer R, Fallone G, Labyak SE, et al. Evidence for the validity of a sleep habits survey for adolescents. Sleep 2003;26(2):213–6. Epub 2003/04/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Matthews KA, Hall M, Dahl RE. Sleep in healthy black and white adolescents. Pediatrics 2014;133(5). 10.1542/peds.2013-2399. e1189-e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Yan LL, Liu K, Rathouz PJ. Self-reported and measured sleep duration: how similar are they? Epidemiology 2008;19(6):838–45. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318187a7b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Jackson CL, Patel SR, Jackson WB, Lutsey PL, Redline S. Agreement between self-reported and objectively measured sleep duration among white, black, Hispanic, and Chinese adults in the United States: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Sleep 2018;41(6). 10.1093/sleep/zsy057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Spilsbury JC, Storfer-Isser A, Drotar D, Rosen CL, Kirchner HL, Redline S. Effects of the home environment on school-aged children’s sleep. Sleep 2005;28(11):1419–27. 10.1093/sleep/28.11.1419. Epub 2005/12/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (https://addhealth.cpc.unc.edu).