Abstract

The role of ςB, an alternative sigma factor of Staphylococcus aureus, has been characterized in response to environmental stress, starvation-survival and recovery, and pathogenicity. ςB was mainly expressed during the stationary phase of growth and was repressed by 1 M sodium chloride. A sigB insertionally inactivated mutant was created. In stress resistance studies, ςB was shown to be involved in recovery from heat shock at 54°C and in acid and hydrogen peroxide resistance but not in resistance to ethanol or osmotic shock. Interestingly, S. aureus acquired increased acid resistance when preincubated at a sublethal pH 4 prior to exposure to a lethal pH 2. This acid-adaptive response resulting in tolerance was mediated via sigB. However, ςB was not vital for the starvation-survival or recovery mechanisms. ςB does not have a major role in the expression of the global regulator of virulence determinant biosynthesis, staphylococcal accessory regulator (sarA), the production of a number of representative virulence factors, and pathogenicity in a mouse subcutaneous abscess model. However, SarA upregulates sigB expression in a growth-phase-dependent manner. Thus, ςB expression is linked to the processes controlling virulence determinant production. The role of ςB as a major regulator of the stress response, but not of starvation-survival, is discussed.

Staphylococcus aureus is an important human pathogen that causes a variety of both life-threatening and mild diseases, including septicemia, toxic shock syndrome, food poisoning, and skin abscesses (68). The range of possible infections reflects the ability of the bacterium to survive and adapt to a spectrum of different environments. Eradication of the organism is extremely difficult, particularly in hospitals, due to its ubiquity and its ability to survive both on the host and in the terrestrial environment. S. aureus is also carried asymptotically, mainly in the nasopharynx and on the skin.

Under deleterious conditions, such as a lack of nutrients or other environmental stresses, many bacteria induce sophisticated response mechanisms whereby they are protected against environmental stress and so allow continued growth or survival until a favorable environment ensues. The starvation and stress responses in gram-negative bacteria such as Salmonella typhimurium, Escherichia coli, and Vibrio spp. have been well characterized, and the alternative sigma factor, RpoS, has been shown to be a major regulator involved in both processes (27, 42, 43). In the human pathogen, Salmonella dublin, RpoS has a central role in the expression of the spv virulence genes, which are induced in response to stationary phase and stress, while an rpoS mutation has been shown to result in avirulence in mice (12). To date, no functional homologues of rpoS have been found in gram-positive bacteria, although the spore-forming Bacillus subtilis responds to environmental stress by induction of the activity of an alternative sigma factor ςB, which modulates expression of a wide range of stress and stationary-phase proteins (9, 33). The regulation of sigB (encoding ςB) in B. subtilis is complex and involves several interactive, regulatory proteins that are located on the sigB operon (8, 72). These both up- and downregulate ςB activity, via protein complexes, at the posttranslational level (1, 21, 31, 64, 65, 72).

In our laboratory, the long-term starvation-survival of S. aureus has recently been characterized (69). Glucose limitation was found to be the major stimulus for S. aureus to enter into the starvation-survival state, with cells remaining viable for several months. Concomitant with survival, cells undergo physiological and biochemical changes, such as reduced size and increased resistance to both acid shock and oxidative stress (69).

The ability of S. aureus to produce a multitude of virulence factors contributes to the bacterium’s survival in host tissue. These virulence determinants are often synthesized in a growth-phase-dependent manner (38), with most exoproteins (such as α-hemolysin [hla gene] and toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 [tst gene]) being expressed during the postexponential or stationary phases, in contrast to the cell wall-associated proteins (such as surface protein A [spa gene]), which are mainly produced during the log phase of growth (44). The biosynthesis of many virulence factors is coordinately regulated by at least two well-characterized, interactive global regulators: staphylococcal accessory regulator (sarA gene) and accessory gene regulator (agr gene) (13, 50, 58, 59). The agr locus controls virulence determinant gene expression via a complex, quorum-sensing signal transduction mechanism (39, 56). The sar locus encodes three overlapping transcripts, sarB, sarC, and sarA, which are expressed at different times during growth and all of which encode SarA (5). SarA is a DNA binding protein which binds to the agr regulatory region and mediates changes in virulence determinant production (15–17, 35, 51).

Recently, a ςB homologue has been identified in S. aureus with an operon organization similar to that of B. subtilis (73). Expression of S. aureus ςB is enhanced by heat shock (47). The sarC transcript, which is preferentially expressed during the stationary phase, has a promoter consensus sequence that is highly homologous to that of B. subtilis ςB (5). Recently Deora and Misra (20) have confirmed that, in vitro, a purified ςB protein interacts with core RNA polymerase to bind specifically to the sarC promoter. In this study, we have constructed a mutant insertionally inactivated in sigB. This has allowed its role in the stationary phase, in the stress response, and in virulence to be assessed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli was grown in Luria-Bertani medium and selected with ampicillin (50 μg ml−1) or kanamycin (50 μg ml−1) where appropriate. S. aureus was routinely grown at 37°C in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium containing erythromycin (5 μg ml−1), tetracycline (5 μg ml−1), kanamycin (50 μg ml−1), neomycin (50 μg ml−1), or lincomycin (25 μg ml−1) where appropriate. Phage transduction was performed as described by Novick (54) with φ11 as the transducing phage.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and/or relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. aureus | ||

| 8325-4 | Wild-type strain cured of all known prophages | 53 |

| RN4220 | Restriction minus, modification plus | 45 |

| PC6911 | agrΔ::tetM (Tetr) | 10 |

| PC1839 | sarA::km (Kanr) | 11 |

| PC400 | sigB::Tc (Tetr) | This study |

| MC90 | sigB+ sigB::lacZ (Eryr) | This study |

| MC100 | sigB+ sigB::lacZ (Eryr) | This study |

| MC102 | sigB+ sigB::lacZ sarA::km (Eryr Kanr) | This study |

| PC161 | sarA+ sarA::lacZ (Eryr) | 10 |

| PC4030 | sarA+ sarA::lacZ sigB::Tc (Eryr Tetr) | This study |

| PC322 | hla+ hla::lacZ (Eryr) | 10 |

| PC4044 | hla+ hla::lacZ sigB::Tc (Eryr Tetr) | This study |

| PC203 | spa+ spa::lacZ (Eryr) | 10 |

| PC4058 | spa+ spa::lacZ sigB::Tc (Eryr Tetr) | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | φ80dlacZΔM15 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 relA1 deoR Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 | Promega |

| TP610 | C600 (F−thi-1 thr-1 leuB6 lacY1 tonA21 supE44 λ−) hsdR hsdM recBC lop11 lig | 34 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pAZ106 | LacZ transcriptional fusion vector (Ampr, E. coli; Eryr, S. aureus) | 41 |

| pUBS1 | E. coli cloning vector (Ampr) | 25 |

| pDG1515 | Tetracycline resistance antibiotic cassette in Bluescript KS(+) (Ampr) | 30 |

| pMI1101 | Chloramphenicol resistance antibiotic cassette in a derivative of pBR322 (Ampr) | 74 |

| pMC4 | 2.3-kb XbaI-EcoRI PCR product containing upstream regulatory region and 5′ end of sigB cloned into pAZ106, cut with XbaI-EcoRI; sigB::lacZ (Ampr, E. coli; Eryr, S. aureus) | This study |

| pPC604 | 1.1-kb EcoRI-SalI PCR product containing the entire sigB gene cloned into pUBS1 cut with EcoRI-SalI (Ampr) | This study |

| pPC624 | 2.1-kb SmaI-HindIII tetracycline resistance cassette from pDG1515, end filled and cloned into pPC604 cut with EcoRV (Ampr) | This study |

| pPC716 | 1.5-kb BamHI chloramphenicol resistance cassette from pMI1101 cloned into pPC624 cut with BamHI (Ampr, E. coli; Eryr, S. aureus) | This study |

For starvation-survival studies, strains were grown in a chemically defined medium (CDM [37]) which was limiting in either amino acids, glucose, or phosphate (69). Growth conditions used to characterize the recovery response from starvation-survival were as reported by Clements and Foster (18).

For LacZ expression studies, strains were grown and LacZ assays performed as previously described (10). Results presented are representative of at least three independent experiments which showed less than 10% variability in final levels.

Stress resistance assays.

All stress resistance assays were carried out in CDM plus 0.1% (wt/vol) glucose with 5 × 106 CFU ml−1, unless otherwise stated and CFU calculated after growth on CDM agar (69). Conditions for oxidative stress in 7.5 mM hydrogen peroxide, acid resistance at pH 2, and UV resistance challenge have been previously reported (69). For heat shock studies, cells were inoculated to a starting A600 of 0.001 in BHI (10 ml) with an exponentially growing culture as the inoculum; they were then grown to an A600 of approximately 0.1, heat shocked by incubation at 54°C for 10 min (static), returned to 37°C, with shaking at 250 rpm, and monitored for growth over a 3-h period. The acid adaptive response was determined by harvesting exponential-phase cells (A600 = 0.5) by centrifugation (12,000 g, 5 min), followed by resuspension at a density of 106 CFU ml−1 in CDM plus 0.1% (wt/vol) glucose at pH 4. These were incubated at 37°C for 1 h prior to centrifugation (12,000 g, 5 min) and resuspension at the same density in CDM plus 0.1% glucose at pH 2. For 2 M NaCl and 6% (vol/vol) ethanol challenges, cultures were grown to exponential phase (A600 = 0.5) in BHI prior to the addition of either NaCl or ethanol. The stress resistance of cells was also determined after 7 days of starvation (69). The results presented here are representative of at least three independent experiments which showed a <20% variability apart from CFU experiments, which varied by <10-fold.

Catalase was measured in culture filtrates as previously described (6). Catalase activity within cell pellets was determined after resuspension of the cells in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4; 10 mM EDTA; 20 μg of lysostaphin ml−1) and repeated freeze-thawing until lysis was observed microscopically.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

MIC values were determined on microtiter plates in 0.2 ml of BHI after a seeding with bacteria to a starting A600 of 0.001 and an incubation at 37°C for 18 h with agitation.

Phenotypic characterization.

Production of extracellular proteins and virulence determinants was measured as previously described (11).

Pathogenicity study.

S. aureus strains were grown to stationary phase (T = 15 h) in BHI as described above. The bacteria were harvested and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline adjusted to 5 × 108 CFU ml−1. Female and male bald mice were inoculated subcutaneously (n = 6) with 0.2 ml of bacterial suspension. After 7 days the mice were sacrificed and skin lesions were aseptically removed and stored frozen in liquid N2. The lesions were weighed and homogenized in 5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline buffer at 4°C for approximately 30 min. The total number of bacteria recovered from the lesions (CFU lesion−1) was determined by viable cell count on BHI agar. Statistical evaluation of the data was determined by the Mann-Whitney U test. All values were reported as the means ± the standard deviations of the mean of six mice.

RNA analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from S. aureus cultures grown to exponential (A600 = 0.5), postexponential (A600 = 8.0), and late-stationary (A600 = 10.5 at T = 18 h) phases in BHI by using a FAST RNA-blue kit (Bio 101, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA samples (5 μg) were transferred onto Hybond-N nylon membrane (Amersham) by using a dot blot apparatus. An antisense RNA probe was prepared from pPC604 (Table 1) with T7 polymerase and labeled with digoxigenin (Boehringer Mannheim). RNA was hybridized with the probe, and the signal was detected as described by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim).

DNA manipulations.

All molecular biology techniques and DNA recombinant manipulations were carried out as described by Sambrook et al. (61). DNA sequencing reactions were carried out with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems) based on the dye terminator cycle sequencing method and then analyzed on an automated ABI DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Construction of a sigB+ sigB::lacZ and a sigB knockout mutant.

To construct a sigB+ sigB::lacZ strain, primers MC3 (5′-GCGCTCTAGAGCCTCAACCAGAAAAATTAGGCG-3′; nucleotides 417 to 437) and MC4 (5′-ACCGGAATTCCGGTTCATTAGCTGATTTCGACTC-3′; nucleotides 2696 to 2716) were designed based on the published sequence of the sigB operon (73), with the additional restriction sites XbaI and EcoRI introduced onto the 5′ ends of primers MC3 and MC4 (underlined), respectively. PCR was used to amplify a 2,326-bp product encompassing the putative rsbU, rsbV, and rsbW gene homologues, the upstream regulatory region, and the 5′ portion of the sigB structural gene. The PCR product was digested with XbaI and EcoRI and ligated into a lacZ transcriptional fusion vector.

pAZ106 was cut with XbaI and EcoRI and transformed into E. coli DH5α. The resulting plasmid, pMC4, was introduced into the chromosome of S. aureus RN4220 by electroporation (63) with selection on erythromycin (5 μg ml−1). A single crossover event led to the creation of strain MC90 (sigB+ sigB::lacZ). Phage transduction was used to transfer the construct into S. aureus 8325-4 to give MC100. The authenticity of the single-copy sigB::lacZ reporter fusion in the chromosome was confirmed by Southern blot analysis by using an appropriate sigB probe (results not shown).

To construct a sigB knockout mutant, a forward primer (MC7, 5′-ACCGGAATTCCGGAAGGAAGGTGACAGTTTTGATTATG-3′; nucleotides 2488 to 2509) and a reverse primer (MC8, 5′-ACGCGTCGACGTCGGGATACACATTAAACTACACT-3′; nucleotides 3577 to 3597) were designed to be complementary to upstream and downstream sequences flanking the sigB gene according to the published sequence (73) and contained the novel restrictions sites EcoRI and SalI (underlined), respectively. The 1,124-bp PCR product was cut with EcoRI and SalI, ligated into the EcoRI-SalI-cut cloning vector, pUBS1 (25), and transformed into E. coli DH5α. This plasmid pPC604 contains a unique EcoRV site internal to the sigB gene. A 2,123-bp SmaI-HindIII DNA fragment containing a tetracycline resistance antibiotic cassette from pDG1515 (30) was end filled and ligated into EcoRV-digested and dephosphorylated pPC604. This was transformed into E. coli TP610 to create plasmid pPC624. The tetracycline resistance cassette was in the same orientation as sigB. A secondary antibiotic marker for use in S. aureus was introduced into pPC624 by ligation of a 1.5-kb BamHI fragment containing a chloramphenicol resistance antibiotic cassette from pMI1101 (74) into BamHI-cut pPC624 and then transformed into E. coli TP610. The resulting construct, pPC716, was transformed into S. aureus RN4220. Recombinants which occur after a single crossover event were selected on tetracycline (5 μg ml−1) BHI agar. Transductional outcross was used to resolve the sigB mutant Tetr Cms colonies (55). Southern blot and PCR analysis were used to confirm a sigB::Tc mutant, and the strain was designated PC400.

RESULTS

Expression of sigB and the effects of environmental factors during growth.

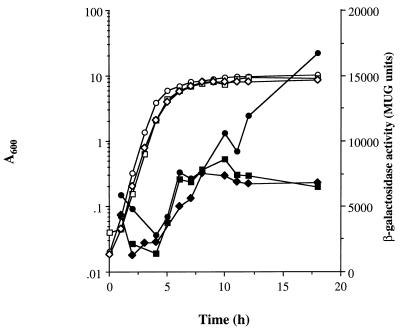

Strain MC100 contains a stable, single copy of sigB::lacZ fusion in a sigB+ background. The kinetics of sigB expression were monitored during growth in highly aerated cultures and were found to rise steadily throughout the growth period, with the highest levels attained during the late stationary phase of growth (17,000 methylumbelliferyl-β-d-galactopyranoside [MUG] units, T = 18 h; Fig. 1). For strains grown in CDM under identical conditions, a similar profile was observed, whereby maximal sigB::lacZ levels were attained during late stationary phase (results not shown).

FIG. 1.

Expression of sigB::lacZ during growth. S. aureus MC100 (sigB::lacZ) was grown in BHI (circles) or BHI supplemented with 1 M NaCl (squares) at 37°C. S. aureus MC102 (sar, sigB::lacZ) was grown in BHI (diamonds) at 37°C. Bacterial growth was measured as the A600 (open symbols), and sigB::lacZ expression was determined by β-galactosidase activity (solid symbols) as described in Materials and Methods.

The effect of different environmental growth conditions on sigB expression were examined. The addition of 1 M NaCl to BHI (10 ml) at the start of growth did not significantly affect the growth rate but led to an approximately twofold decrease in LacZ activity (T = 18 h). This differential sigB::lacZ expression occurred specifically during the postexponential phase after 8 h of growth (Fig. 1). Dot blot RNA studies with a sigB antisense probe showed an approximately twofold decrease in the hybridization signal in 1 M NaCl compared to that in BHI alone at T = 8 h (data not shown). In 18-h cultures, the sigB RNA signal was almost totally abolished under these conditions, suggesting that the high levels of sigB::lacZ expression observed late in growth (Fig. 1) may be a reflection of the stability of β-galactosidase. The effect of the bacteriostatic acid conditions (pH 4 compared to pH 7) or the H2O2 concentration (60 μM) in CDM did not effect sigB::lacZ transcription after the treatment of exponential-phase cells (A600 = 0.5) over a 30-min period with either stress (results not shown). The sublethal concentration of H2O2 used is probably rapidly degraded by catalase.

Role of ςB in sarA and virulence determinant gene expression.

To investigate the role of ςB in the regulation of virulence determinant production, the sigB mutation was introduced into a set of reporter strain fusions to representative virulence determinants (10).

When sarA expression was monitored through growth in PC161 (sarA::lacZ) and PC4030 (sigB::tet, sarA::lacZ) in 10 ml of BHI under aerobic conditions, sarA levels were found to increase gradually throughout growth, reaching a maximum of approximately 6,000 MUG units at T = 12 h (results not shown). There was no significant difference in sarA expression in the wild-type and sigB backgrounds.

A possible regulatory role of SarA on sigB expression was also examined. Surprisingly, our transcriptional studies revealed that sigB::lacZ expression was significantly reduced (by approximately twofold) at 18 h of growth in an sarA mutant (MC102) compared to the wild-type strain (MC100) (Fig. 1). Thus, SarA may be involved in upregulating sigB expression during the postexponential phase. RNA dot blot analysis of sigB transcripts in PC1839 (sarA) showed a two- to fivefold reduction in total sigB transcript during the postexponential phase of growth (T = 8 h) compared to strain 8325-4 (results not shown). The difference in the sigB transcript levels was not apparent until after 8 h of growth, which also suggests that sarA regulation of sigB is growth phase dependent, although it is possible that the transcript stability may be affected.

The effect of a sigB mutation on the transcription of the virulence determinants, hla and spa, was investigated after the introduction of hla::lacZ and spa::lacZ reporter fusions into a sigB mutant background (PC400). There was no significant difference between hla transcription in PC4044 (sigB, hla::lacZ) and PC322 (hla::lacZ) during growth (results not shown). Similarly, a sigB mutation had no effect on spa expression throughout the growth cycle in PC4058 (sigB, spa::lacZ) compared to PC203 (spa::lacZ) (results not shown). The sigB mutation also had no significant effect on the production of lipase, DNase, protease, and α- and β-hemolysin as determined by plate assay; nor did it significantly affect α- and β-hemolysin levels in culture supernatants (results not shown). Exoprotein profiles were also similar in 8325-4 and PC400 (sigB) (results not shown).

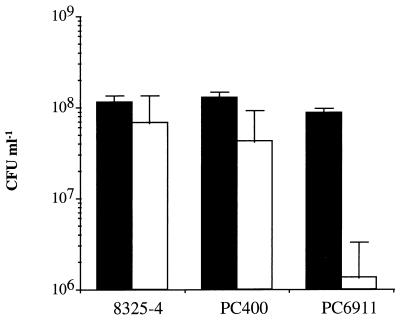

Role of ςB in pathogenicity.

The pathogenicity model was developed to study the ability of S. aureus to cause infection by abscess formation on the skin. After 7 days of infection, ca. 7 × 107 and 4 × 107 CFU of the wild-type (8325-4) and PC400 (sigB) were recovered from the lesion, respectively, values which were not significantly different. In contrast, only 106 CFU of PC6911 (agr) was recovered, which was significantly less than that from either the parent (8325-4) or the sigB (PC400) mutant (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Role of sigB in virulence. Bald mice were inoculated subcutaneously with ≈108 cells of S. aureus strains 8325-4, PC400 (sigB), or PC6911 (agr), as represented by the solid bars. Mice were sacrificed after 7 days, and the number of bacteria recovered from skin lesions was counted (open bars).

Role of ςB in environmental stress resistance.

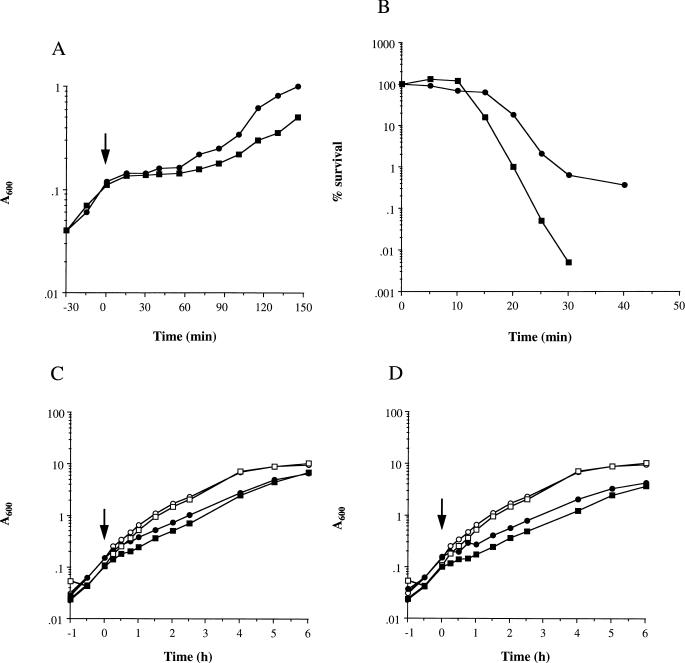

PC400 (sigB) showed increased sensitivity to heat shock compared to 8325-4 (Fig. 3A). When exponential-phase cells of PC400 (A600 = 0.1) grown at 37°C were transiently heat shocked (54°C, 10 min), the lag period before growth resumed was extended by ca. 30 min (T = 60 min) compared to strain 8325-4 (T = 30 min). The increase in the lag period was highly reproducible (±5 min).

FIG. 3.

Role of sigB in the response to different environmental stresses. S. aureus 8325-4 (circles) and PC400 (sigB) (squares) were grown to different growth phases at 37°C and then subjected to various environmental stresses as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Effect of heat shock (54°C for 10 min, T = 0). Growth was measured as the A600. The arrow denotes the initiation of heat shock. (B) Effect of H2O2 (7.5 mM) on stationary-phase cells. (C) Effect of ethanol (6% [vol/vol], solid symbols) or no addition (open symbols) on exponential-phase cells. The arrow indicates when the ethanol was added. (D) Effect of 2 M NaCl (solid symbols) or no addition (open symbols) on exponential-phase cells. The arrow indicates when the NaCl was added.

Upon starvation, S. aureus 8325-4 develops increased resistance to H2O2 (69). Inactivation of sigB (PC400) led to increased sensitivity to H2O2 compared to 8325-4, for both stationary-phase (Fig. 3B) and starved cells (results not shown), whereas no difference was observed for exponential-phase cells. Exposure of late-stationary-phase cells (T = 16 h) to 7.5 mM H2O2 led to an approximate 4-log decrease in the viability of PC400 (sigB) at 30 min compared to a 2-log decrease for 8325-4 (Fig. 3B). Similarly, in 6-day-starved cultures, H2O2-induced death was greater in PC400 (sigB), with an approximately 1-log-greater loss of viability compared to 8325-4 after 25 min (results not shown).

When catalase activity was measured in cells and their culture supernatants, there was no significant difference in the levels of catalase in the sigB mutant (PC400) versus that with the wild type (8325-4) in exponential-phase cells (A600 = 0.5), stationary-phase cells (T = 16 h), or starved cells (7 days) (results not shown).

The role of sigB in ethanol or osmotic shock was also examined. The rate of growth of 8325-4 was perturbed when either 6% (vol/vol) ethanol or 2 M NaCl was added to the exponential-phase cells (T = 0 h, A600 = 0.1). This led to a reduction in the growth rate after the application of the stress (Fig. 3C and D); however, this reduction was independent of ςB.

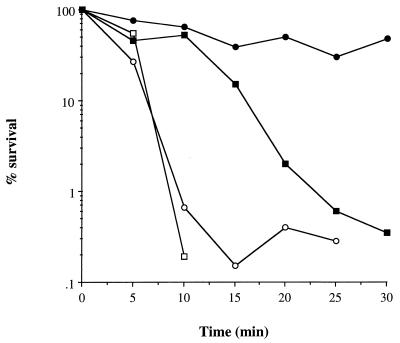

The role of ςB in acid stress resistance.

The role of ςB in acid stress resistance under adapted and nonadapted pH growth conditions was examined (Fig. 4). Exponentially grown cells (A600 = 0.5) of PC400 (sigB) treated at pH 2 were more sensitive to acid stress compared to the parent under nonadapted conditions (Fig. 4). After 15 min of acid treatment, PC400 (sigB) was totally unculturable (>6-log drop in CFU). Interestingly, a dramatic increase in resistance to acid stress at pH 2 was acquired in S. aureus 8325-4 by a preexposure of the bacteria to a pH 4 environment; this was demonstrated by the increased survival of 8325-4 under adapted (no significant cell death after 30 min) compared to nonadapted conditions (>3-log drop) (Fig. 4). Furthermore, this protective acid-adaptive response was also mostly mediated via ςB, since acid-adapted cells of PC400 lost a >2-log viability, whereas 8325-4 lost a <0.5-log viability, after 30 min at pH 2. A similar ςB-dependent acid-adaptive response was noted in overnight (16-h) cultures, where adapted cells of PC400 (sigB) were less tolerant to acid stress (>3-log drop after 20 min) compared to the parent (>3-log drop after 30 min; results not shown). In contrast, ςB does not appear to play a role in the development of acid resistance associated with starvation (69) since there was no difference in the survival kinetics of 7-day-starved cells of PC400 (sigB) and 8325-4 on exposure to pH 2 (results not shown).

FIG. 4.

Role of sigB in the acid stress response. S. aureus strains were grown and treated with acid as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were either resuspended at pH 4 at 37°C for 1 h (solid symbols) or left untreated (open symbols) prior to the pH 2 treatment. Circles, S. aureus 8325-4; squares, PC400 (sigB).

The role of ςB in the starvation-survival and recovery responses.

It has been proposed that ςB may mediate the expression of genes during the stationary phase of growth, leading to the development of starvation-survival potential and the ability to recover rapidly from starvation (18, 47, 69). Surprisingly, PC400 (sigB) did not show defective starvation-survival kinetics compared to 8325-4 under glucose, amino acid, or phosphate nutrient-limiting conditions (results not shown). Similarly, ςB is not essential for the recovery response from the starvation-survival state, since PC400 (sigB) showed no significant alteration in recovery kinetics upon the addition of CDM containing amino acids and glucose relative to 8325-4 (results not shown).

Antimicrobial susceptibility of ςB.

There was no difference in the MICs of methicillin (0.6 μg/ml), gentamycin (0.7 μg/ml), erythromycin (0.2 μg/ml), vancomycin (1 μg/ml), and streptomycin (5 μg/ml) in the sigB mutant and wild-type backgrounds.

DISCUSSION

The discovery of an alternative sigma factor, ςB, in S. aureus that shows high homology and a similar operon organization to that of ςB of B. subtilis (73) led to speculation of an analogous role for ςB in stationary-phase regulation and the environmental stress resistance in S. aureus. In addition, the location of a ςB binding site in a promoter sequence within the sar locus (5) implicated a putative function of ςB in virulence determinant gene regulation in S. aureus. To date, only ςB and ςA (the major housekeeping sigma factor) have been identified in S. aureus (19, 20). In this work, we have characterized the role of ςB in the environmental stress response, starvation-survival and recovery, and in a mouse abscess model of pathogenicity in S. aureus using a sigB mutant created by insertional inactivation.

Recently, Deora et al. (20) showed that ςB in conjunction with core RNA polymerase binds specifically to the sarC promoter of the sar operon in vitro. The sarC transcript, which is preferentially expressed upon entry into stationary phase, encodes both SarA, the active protein which mediates its affects on virulence target genes, and a putative small peptide of unknown function (5). The present study has shown that lack of ςB does not significantly effect the levels of SarA. Since our sarA::lacZ fusion detects all three transcripts, including sarC, in vivo, this suggests that sarC is a minor transcript under standard growth conditions and does not contribute greatly to the overall levels of SarA. ςB also did not have a major role in the control of transcription of a range of virulence determinants or in a mouse subcutaneous abscess model of S. aureus pathogenesis. However, one cannot rule out a role for ςB in the ability of S. aureus to cause other types of infection.

The production of many virulence determinants in S. aureus is highly regulated, with most exoproteins preferentially synthesized in the transition between exponential- and stationary-growth phases. Since both SarA and ςB are expressed at high levels in the postexponential-growth period, we also evaluated whether SarA has a role in mediating ςB expression during the stationary phase. To our surprise, we found that in a SarA mutant sigB transcription was reduced specifically during the stationary phase. This implies SarA upregulates ςB expression at the transcriptional level upon entry into stationary phase. To date, SarA has only been shown to bind to the regulatory region of the P2-P3 promoter of agr (15, 17, 51), and other SarA binding sites have not been reported. Whether SarA acts directly at a sigB promoter site or via an intermediate complex is unclear.

In B. subtilis, a large number of stress proteins have been shown to be induced in response to specific environmental stimuli, such as heat shock, salt concentration, glucose starvation, oxygen limitation, or oxidative stress (32, 33). Of these, the induction of over 40 general stress proteins has been reported to be dependent on ςB (8, 9, 23, 33, 66), as indicated mainly by their differential production in a ςB mutant as measured by two-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (33, 66). The roles of a number of ςB-controlled stress proteins have begun to be identified (4, 46, 62, 67). Also, physiological roles for ςB in oxidative stress resistance and survival under long-term pH stress have been established (3, 4, 22, 28, 62). Very recently, a sigB homologue was found in Listeria monocytogenes that is involved in acid tolerance (71). In S. aureus, the environmental stress response has not been extensively characterized, although several novel proteins induced by heat shock and alkaline pH stress have been identified by differential two-dimensional SDS-PAGE analysis (48, 57).

The function of ςB in S. aureus was examined under various stresses. ςB has a role in acid tolerance (pH 2). A low-pH environment is characteristic of the phagolysosome, being one of the major modes of killing by human neutrophils (49). Adaptive acid tolerance responses have been well characterized in the human pathogen S. typhimurium and have been suggested to have a protective role against acid conditions encountered in vivo in the macrophage phagolysomes during infection (26). The evidence that preexposure of S. aureus to a sublethal environment of pH 4 was found to increase its rate of survival at pH 2 is the first report of an acid-adaptive response in this organism. S. aureus is able to grow over a wide range of pH levels, and changes in pH can affect production of virulence determinants (60). Hence, the ability of S. aureus to induce an acid-adaptive response at pH 4 (a nonlethal pH), thus conferring protection against a harsher acid treatment, may give it an effective resistance against host defense mechanisms.

Bacteria respond to shifts in growth temperatures by means of increased thermal tolerance as part of the heat shock response (29). Previously, a role for ςB in the heat shock response was postulated, since a novel 1.5-kb sigB transcript was specifically induced, and a 1.2-kb sigB mRNA was enhanced, following exposure of log-phase cells to 48°C for 30 min (47). In the present study, a ςB mutant showed increased sensitivity to heat shock (54°C for 10 min) compared to the parental strain. Recently, several heat-induced proteins, some related to known heat shock proteins, were identified after a thermal upshift of S. aureus cells to 46°C (57). In B. subtilis, ςB is nonessential for the survival of the bacterium following heat shock, since a ςB null mutant was as temperature resistant as the wild type and was also still able to produce the major heat-inducible proteins (7, 66).

In B. subtilis both ethanol and high-salt stress can strongly induce ςB expression (7, 8, 66). Also, in S. aureus ethanol shock (4% [vol/vol]) slightly enhanced the levels of the 1.2-kb sigB transcript (47). However, in this study exposure to ethanol (6% [vol/vol]) or osmotic shock (2 M NaCl) during exponential phase did not result in an altered response between the ςB mutant and its wild-type counterpart.

Cells subject to oxidative stress may respond by producing catalases that confer a greater resistance to the bacteria against the detrimental effects of hydrogen peroxide (52). The rpoS gene was originally identified as a mutation leading to a catalase deficiency and was later shown to be a global regulator of stationary-phase gene expression in E. coli (43). In B. subtilis, expression studies have shown that KatE, a catalase, is unequivocally under the direct control of ςB (23), as are other genes with a role in oxidative stress (3, 4). Superoxide dismutases may also form part of the bacteria’s armory against oxidative stress by converting superoxide free radicals produced by host defenses into hydrogen peroxide, which is then removed by the catalases (24). This idea is consistent with the recent identification in our laboratory of the major superoxide dismutase (SodA) of S. aureus as having a role in starvation-survival (70). In the present study, the ςB mutant showed increased sensitivity to killing by H2O2, suggesting that ςB may be involved in response to oxidative stress in exponential cells. Interestingly, this was not directly due to an alteration in catalase activity, suggesting that other oxidative stress resistance components are involved. In E. coli, a DNA binding protein DPS, synthesized during starvation, forms extremely stable complexes with DNA and plays a role in protecting DNA from oxidative damage (2). In B. subtilis a DPS homologue has recently been shown to be partially under the control of ςB (4).

The similar organization of the sigB operon in S. aureus and B. subtilis suggests a homologous role for the regulatory proteins RsbU, RsbV, and RsbW (47, 73). In B. subtilis, the molecular mechanism involved in the regulation of ςB has been extensively studied and is complex, involving both different pathways dependent on the metabolic or environmental cues and other unknown additional components (1, 31). Many of the environmental stress signals release the RsbW (anti-ςB) inhibition of ςB, resulting in increased sigB activity, a process also dependent on RsbV, an antagonist of RsbW (31). An autocatalytic activity of ςB was also reported which ensures that slight changes in levels of ςB will lead to a dramatic stress response (1). However, RNA transcript analysis suggests that the transcriptional control of the sigB locus involving the cis-acting regulatory elements may be different in S. aureus and B. subtilis (47), although the posttranslational effects on ςB activity in S. aureus are unknown. Interestingly, in S. aureus the sigB operon lacks the upstream genes encoding RsbR, RsbS, and RsbT, which in B. subtilis combine with RsbU to form a complex module primarily responsible for activating ςB in response to environmental (heat or salt concentration) rather than energy stress (stationary or starvation) signals (1, 40).

While our study was in progress, the sequence of the sigB operon of S. aureus 8325 was published (47) and was found to contain an 11-bp deletion within rsbU compared to the initial published sequence of S. aureus COL (73). This deletion was predicted to result in a 70-amino-acid truncation of the encoded RsbU protein. We have confirmed that the deletion is also present in the S. aureus strain 8325-4 used in this study (results not shown). In B. subtilis, rsbU is essential for stress-induced activation of ςB but is not required for activation of ςB during the stationary phase of growth (65). However, the transcriptional regulation of the sigB operon in S. aureus 8325, in response to growth phase, heat, and ethanol shock was comparable to that of the clinical isolate S. aureus 14627 (47). S. aureus 8325-4 has been well characterized in several respects (10, 11, 18, 51, 69, 70), which has allowed the role of ςB to be established. However, it is possible that rsbU+ strains of S. aureus may show alterations in responses.

Bacteria encountering nutrient limitation coordinately regulate their gene expression to produce components important for survival. We have identified several starvation-survival components involved in nutrient scavenging, protection against oxidative stress, and the SOS response that are necessary for survival (70). How nutrient limitation stimuli are transduced to allow long-term survival and increased stress resistance in S. aureus is unknown. In many gram-negative strains, these processes are mediated by RpoS (36) which, like ςB in B. subtilis, alters gene expression at the onset of starvation (9). We were unable to demonstrate in S. aureus a similar global role for ςB in starvation-survival. However, ςB was found to be required for stress resistance and the acid-adaptive response in exponential-phase cells. The stress resistance associated with long-term starvation is mostly independent of that of exponential-phase cells. Hence, ςB is not a functional homologue of RpoS as it does not have a major role in starvation-survival and its associated resistance levels. No regulatory element has so far been identified in S. aureus that controls starvation-survival-associated processes. Intriguingly, our findings that SarA affects sigB transcription infer a putative role for SarA in the stress response. It is already well established that SarA is a major regulator of virulence determinant production in S. aureus (11, 13, 14). Thus, the hierarchical regulation of virulence determinant gene expression and the response to environmental stresses are linked and involve a close and complex interaction between SarA and ςB; this interaction determines the efficient transduction of environmental signals so as to allow bacterial adaptation and survival.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research program was supported by MAFF (P.F.C.), BBSRC/Celsis Connect (M.O.C.), and the Royal Society (S.J.F.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Akbar S, Kang C M, Gaidenko T A, Price C W. Modulator protein RsbR regulates environmental signalling in the general stress pathway of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:567–578. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3631732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almiron M, Link A J, Furlong D, Kolter R. A novel DNA-binding protein with regulatory and protective roles in starved Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2646–2654. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antelmann H, Engelmann S, Schmid R, Hecker M. General and oxidative stress responses in Bacillus subtilis: cloning, expression, and mutation of the alkyl hydroperoxide reductase operon. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6571–6578. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6571-6578.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antelmann H, Engelmann S, Schmid R, Sorokin A, Lapidus A, Hecker M. Expression of a stress- and starvation-induced dps/pexB-homologous gene is controlled by the alternative sigma factor ςB in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7251–7256. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7251-7256.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayer M G, Heinrichs J H, Cheung A L. The molecular architecture of the sar locus in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4563–4570. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4563-4570.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beers R F, Jr, Sizer I W. A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J Biol Chem. 1952;195:267–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benson A K, Haldenwang W G. The ςB-dependent promoter of the Bacillus subtilis sigB operon is induced by heat shock. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1929–1935. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.7.1929-1935.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boylan S A, Redfield A R, Brody M S, Price C W. Stress-induced activation of the ςB transcription factor of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7931–7937. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7931-7937.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boylan S A, Redfield A R, Price C W. Transcription factor ςB of Bacillus subtilis controls a large stationary-phase regulon. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3957–3963. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.3957-3963.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan P F, Foster S J. The role of environmental factors in virulence determinant regulation of in Staphylococcus aureus 8325-4. Microbiology. 1998;144:2469–2479. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-9-2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan P F, Foster S J. Role of SarA in virulence determinant production and environmental signal transduction in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6232–6241. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6232-6241.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen C Y, Buchmeier N A, Libby S, Fang F C, Krause M, Guiney D G. Central regulatory role for the RpoS sigma factor in expression of Salmonella dublin plasmid virulence genes. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5303–5309. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.18.5303-5309.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheung A L, Koomey J M, Butler C A, Projan S J, Fischetti V A. Regulation of exoprotein expression in Staphylococcus aureus by a locus (sar) distinct from agr. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6462–6466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheung A L, Ying P. Regulation of α- and β-hemolysins by the sar locus of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:580–585. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.580-585.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheung A L, Bayer M G, Heinrichs J H. sar genetic determinants necessary for transcription of RNAII and RNAIII in the agr locus of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3963–3971. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.3963-3971.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheung A L, Eberhardt K, Heinrichs J H. Regulation of protein A synthesis by the sar and agr loci of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2243–2249. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2243-2249.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chien Y, Cheung A L. Molecular interactions between two global regulators, sar and agr, in Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2645–2652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clements M O, Foster S J. Starvation recovery of Staphylococcus aureus 8325-4. Microbiology. 1998;144:1755–1763. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-7-1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deora R, Misra T K. Characterisation of the primary ς factor of Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21828–21834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.21828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deora R, Tseng T, Misra T K. Alternative transcription factor ςSB of Staphylococcus aureus: characterization and role in transcription of the global regulatory locus sar. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6355–6359. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6355-6359.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dufour A, Haldenwang W G. Interactions between a Bacillus subtilis anti-sigma factor (RsbW) and its antagonist (RsbV) J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1813–1820. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.1813-1820.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engelmann S, Hecker M. Impaired oxidative stress resistance of Bacillus subtilis sigB mutants and the role of katA and katE. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;145:63–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engelmann S E, Lindner C, Hecker M. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and regulation of katE encoding a ςB-dependent catalase in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5598–5605. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5598-5605.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farrant J L, Sansone A, Canvin J R, Pallen M J, Langford P R, Wallis T S, Dougan G, Kroll J S. Bacterial copper and zinc-cofactored superoxide dismutase contributes to the pathogenicity of systemic salmonellosis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:785–796. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5151877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foster S J. Cloning, expression, sequence analysis and biochemical characterisation of an autolytic amidase of Bacillus subtilis 168 trpC2. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:1987–1998. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-8-1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foster J W, Hall H K. Adaptive acidification tolerance response of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:771–778. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.771-778.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foster J W, Spector M P. How Salmonella survive against the odds. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:145–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaidenko T A, Price C W. General stress transcription factor B and sporulation transcription factor H each contribute to survival of Bacillus subtilis under extreme growth conditions. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3730–3733. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3730-3733.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gross C A. Function and regulation of the heat shock proteins. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B Jr, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 1382–1399. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guérout-Fleury A-M, Shazand K, Frandsen N, Stragier P. Antibiotic-resistance cassettes for Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1995;167:335–336. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00652-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haldenwang W G. The sigma factors of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:1–30. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.1-30.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hecker M, Völker U. General stress proteins in Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1990;74:197–214. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hecker M, Schumann W, Voelker U. Heat-shock and general stress response in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:417–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.396932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hedegaard L, Danchin A. The cya gene region of Erwinia chrysanthemi B374: organisation and gene products. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;201:38–42. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heinrichs J H, Bayer M G, Cheung A L. Characterization of the sar locus and its interactions with agr in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:418–423. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.418-423.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hengge-Aronis R. Survival of hunger and stress: the role of rpoS in early stationary phase gene regulation in E. coli. Cell. 1993;72:165–168. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90655-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hussain M, Hastings J G M, White P J. A chemically defined medium for slime production by coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Med Microbiol. 1991;34:143–147. doi: 10.1099/00222615-34-3-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iandolo J J. The genetics of staphylococcal toxins and virulence factors. In: Iglewski B H, Clark V L, editors. Molecular basis of bacterial pathogenesis. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 399–426. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ji G, Beavis R C, Novick R P. Cell density control of staphylococcal virulence mediated by an octapeptide pheromone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:12055–12059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang C M, Brody M S, Akbar S, Yang X, Price C W. Homologous pairs of regulatory proteins control activity of Bacillus subtilis transcription factor ςB in response to environmental stress. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3846–3853. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3846-3853.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kemp E H, Sammons R L, Moir A, Sun D, Setlow P. Analysis of transcriptional control of the gerD spore germination gene of Bacillus subtilis 168. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4646–4652. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.15.4646-4652.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kjelleberg S, Albertson N, Flardh K, Holmquist L, Jouperjaan A, Marouga J, Ostling R, Svenblad B, Weichart D. How do nondifferentiating bacteria adapt to starvation? Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1993;63:331–341. doi: 10.1007/BF00871228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kolter R, Siegele D A, Tormo A. The stationary-phase of the bacterial life-cycle. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:855–874. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.004231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kornblum J, Kreiswirth B N, Projan S J, Ross H, Novick R P. agr: a polycistronic locus regulating exoprotein synthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. In: Novick R P, editor. Molecular biology of the staphylococci. New York, N.Y: VCH Publishers; 1990. pp. 373–402. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kreiswirth B, Löfdahl S, Betley M J, O’Reilly M, Schleivert M P, Bergdoll M S, Novick R P. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature. 1983;305:709–712. doi: 10.1038/305709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kruger E, Msadek T, Hecker M. Alternate promoters direct stress-induced transcription of the Bacillus subtilis clpC operon. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:713–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kullik I, Giachino P. The alternative sigma factor ςB in Staphylococcus aureus: regulation of the sigB operon in response to growth phase and heat shock. Arch Microbiol. 1997;167:151–159. doi: 10.1007/s002030050428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuroda M, Ohta T, Hayashi H. Isolation and the gene cloning of an alkaline shock protein in methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;207:978–984. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mandell G L. Bactericidal activity of aerobic and anaerobic polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1974;9:337–341. doi: 10.1128/iai.9.2.337-341.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morfeldt E, Janzon L, Arvidson S, Löfdahl S. Cloning of a chromosomal locus (exp) which regulates the expression of several exoprotein genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;211:435–440. doi: 10.1007/BF00425697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morfeldt E, Tegmark K, Arvidson S. Transcriptional control of the agr-dependent virulence gene regulator, RNAIII, in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1227–1237. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.751447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mulvey M R, Switala J, Borys A, Loewen P C. Regulation of transcription of katE and katF in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6713–6720. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6713-6720.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Novick R P. Properties of a cryptic high-frequency transducing phage in Staphylococcus aureus. Virology. 1967;33:155–166. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(67)90105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Novick R P. Genetic systems in staphylococci. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:587–636. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04029-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Novick R P, Ross H F, Projan S J, Kornblum J, Kreiswirth B, Moghazeh S. Synthesis of staphylococcal virulence factors is controlled by a regulatory RNA molecule. EMBO J. 1993;12:3967–3975. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Novick R P, Projan S J, Kornblum J, Ross H F, Ji G, Kreiswirth B, Vandenesch F, Moghazeh S. The agr P2 operon: an autocatalytic sensory transduction system in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;248:446–458. doi: 10.1007/BF02191645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ohta T, Saito K, Kuroda M, Honda K, Hirata H, Hayashi H. Molecular cloning of two new heat shock genes related to the hsp70 genes in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4779–4783. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4779-4783.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peng H-L, Novick R P, Kreiswirth B, Kornblum J, Schlievert P. Cloning, characterization, and sequencing of an accessory gene regulator (agr) in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4365–4372. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4365-4372.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Recsei P, Kreiswirth B, O’Reilly M, Schlievert P, Gruss A, Novick R P. Regulation of exoprotein gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus by agr. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;202:58–61. doi: 10.1007/BF00330517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Regassa L B, Betley M J. Alkaline pH decreases expression of the accessory gene regulator (agr) in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5095–5100. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.5095-5100.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scharf C, Riethdorf S, Ernst H, Engelmann S, Volker U, Hecker M. Thioredoxin is an essential protein induced by multiple stresses in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1869–1877. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1869-1877.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schenk S, Laddaga R A. Improved methods for electroporation of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;94:133–138. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90596-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Voelker U, Dufour A, Haldenwang W G. The Bacillus subtilis rsbU gene product is necessary for RsbX-dependent regulation of sigma B. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:114–122. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.114-122.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Voelker U, Voelker A, Maul B, Hecker M, Dufour A, Haldenwang W G. Separate mechanisms activate sigma B of Bacillus subtilis in response to environmental and metabolic stress. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3771–3780. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.13.3771-3780.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Völker U, Engelmann S, Björn M, Riethdorf S, Völker A, Schmid R, Mach H, Hecker M. Analysis of the induction of general stress proteins of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 1994;140:741–752. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-4-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Von Blohn C, Kempf B, Kappes R M, Bremer E. Osmostress response in Bacillus subtilis: characterization of a proline uptake system (OpuE) regulated by high osmolarity and the alternative transcription factor sigma B. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:175–187. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4441809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Waldvogel F A. Staphylococcus aureus (including toxic shock syndrome) In: Mandell G L, Douglas R G, Bennet J E, editors. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. New York, N.Y: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. pp. 1489–1510. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Watson S P, Clements M O, Foster S J. Characterization of the starvation-survival response of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1750–1758. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1750-1758.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Watson, S. P., M. Antonio, and S. J. Foster. Isolation and characterisation of Staphylococcus aureus starvation-induced, stationary-phase mutants defective in survival or recovery. Microbiology 144:3159–3169. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Wiedmann M, Arvik T J, Hurley R J, Boor K J. General stress transcription factor B and its role in acid tolerance and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3650–3656. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3650-3656.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wise A, Price C W. Four additional genes in the sigB operon of Bacillus subtilis that control activity of the general stress factors ςB in response to environmental stress. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:123–133. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.123-133.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu S, de Lencastre H, Tomasz A. Sigma-B, a putative operon encoding alternate sigma factor of Staphylococcus aureus RNA polymerase: molecular cloning and DNA sequencing. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6036–6042. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.6036-6042.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Youngman P, Perkins J B, Losick R. Construction of a cloning site near one end of Tn917 into which foreign DNA may be inserted without affecting transposition in Bacillus subtilis or expression of the transposon-borne erm gene. Plasmid. 1984;12:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(84)90061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]