Supplemental Digital Content is Available in the Text.

Key Words: HIV in Asia, HIV dynamics, modeling, software, data synthesis, key populations

Abstract

Background:

Thirteen Asian countries use the AIDS Epidemic Model (AEM) as their HIV model of choice. This article describes AEM, its inputs, and its application to national modeling.

Setting:

AEM is an incidence tool used by Spectrum for the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS global estimates process.

Methods:

AEM simulates transmission of HIV among key populations (KPs) using measured trends in risk behaviors. The inputs, structure and calculations, interface, and outputs of AEM are described. The AEM process includes (1) collating and synthesizing data on KP risk behaviors, epidemiology, and size to produce model input trends; (2) calibrating the model to observed HIV prevalence; (3) extracting outputs by KP to describe epidemic dynamics and assist in improving responses; and (4) importing AEM incidence into Spectrum for global estimates. Recent changes to better align AEM mortality with Spectrum and add preexposure prophylaxis are described.

Results:

The application of AEM in Thailand is presented, describing the outputs and uses in-country. AEM replicated observed epidemiological trends when given observed behavioral inputs. The strengths and limitations of AEM are presented and used to inform thoughts on future directions for global models.

Conclusions:

AEM captures regional HIV epidemiology well and continues to evolve to meet country and global process needs. The addition of time-varying mortality and progression parameters has improved the alignment of the key population compartmental model of AEM with the age–sex-structured national model of Spectrum. Many of the features of AEM, including tracking the sources of infections over time, should be incorporated in future global efforts to build more generalizable models to guide policy and programs.

INTRODUCTION

The AIDS Epidemic Model (AEM), previously known as the Asian Epidemic Model, began development in 1998 to address critical policy and program relevant questions about the most influential drivers of the HIV epidemics of Asia.1,2 It was a model birthed in the data-rich environment of Southeast Asia in the late 1990s, where HIV surveillance systems in many countries were robust and growing in scope, ongoing behavioral data collection was rapidly becoming a norm, and size estimation exercises were increasingly common.3–10 As such, AEM was constructed as a process model, taking trends in key behavioral, epidemiological, and size estimate data as inputs and using them to simulate the processes of HIV transmission among and between both key populations and those not in key populations through vaginal sex, anal sex, and needle sharing.

The first national applications of AEM were in Thailand in 2000 and Cambodia in 200211,12 where they helped to demonstrate the past impact of the countries' prevention efforts and guide national responses toward a greater impact. Because AEM produces key population-specific annual new infections, current infections, and deaths and is instrumented to capture sources of infections for each subpopulation over time, countries can identify the primary drivers of both current and downstream infections and validate them against observed outcomes in key populations, making it a valuable tool for targeting responses for impact as the drivers in an epidemic evolve.

These features made it attractive to Asian countries, and by 2015, AEM had become the national model in 9 Asian countries. Although countries were using AEM to explore key population dynamics, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) global HIV estimates process13 was built around Spectrum,14,15 developed by Avenir Health. Spectrum was based on a single age- and sex-structured national population, taking incidence from an incidence model, for example, the UNAIDS Estimation and Projection Package (EPP)16,17 that fits mathematical models to prevalence data, and applying age and sex differences in mortality and HIV progression to calculate national HIV prevalence. In 2015, Spectrum was modified to accept AEM as an incidence source, allowing countries to use their key population-structured AEM projections as part of the UNAIDS-led global estimates process, whereas still maintaining the national age–sex structure of Spectrum.18 As shown in Figure 1, today 13 Asian countries use AEM as the basis of their national projections and the incidence source for their Spectrum files.

FIGURE 1.

Countries using AEM in 2023 as their national model, shown in dark blue, and countries having applied AEM subnationally in some provinces or states, shown in light blue.

This article describes the AEM methodology and approach as of version 5.2. It presents the internal structure of AEM, explains how AEM calculates HIV transmission, lists the required inputs, outlines the process of fitting AEM to national key population trends, and shows the multiple outputs generated. Results for Thailand are presented and then strengths, limitations, and future directions are discussed.

METHODS

Overview of the AEM Internal Model Structure

The compartmental structure of AEM is built around key populations with 2 additional male and female groups containing all those not in key populations, labeled non-KP (Fig. 2). The structure for male and transgender persons has compartments for

clients of female sex workers (FSWs) (clients);

men who have sex with men (2 groups, MSM1 and MSM2);

male sex workers (MSWs);

male populations who inject drugs (male PWID [people who inject drugs]);

transgender persons: those who sell sex, those with casual partners, and those with regular partners; and

non-key population males (non-KP males), that is, those males not in one of the preceding groups.

FIGURE 2.

Internal structure of AEM for (A) male population and transgender persons and (B) female population. Internally, AEM is built around key populations important in HIV epidemics: FSWs and clients, people who inject drugs, MSM, transgender persons, and non-KP males and females. The arrows indicate movement allowed between groups in the model.

The female structure includes

female sex workers (2 groups, FSW1 and FSW2),

sex workers who inject (2 groups, ISW1 and ISW2),

female population who inject drugs (female PWID), and

non-key population females (non-KP females).

All AEM compartments contain all people in the specified group older than 15 years. People enter this structure at age 15 years, can move between compartments according to key population size changes and duration input parameters,19 and leave the structure by death. There is no explicit age structure in AEM; each compartment contains all individuals aged 15 years and older meeting the compartment's definition. The effects of ART are accounted for by having separate compartments within each population for those on-ART and off-ART, as described in Supplemental Digital Content 1 (see Figures 1–4, http://links.lww.com/QAI/C135 for details). As in Spectrum, the annual numbers/percentages on ART are specified as inputs, either by total male and female populations or by specifying ART numbers/percentages within each subpopulation. ART then modifies both survival and transmission in internal calculations.

The 2 compartments for MSM and FSW give countries flexibility in applying the model. Countries define those local subcategories of MSM and FSW falling into each group and then input the appropriate behaviors, prevalence, and other inputs for those groups. For example, in Cambodia, the 2 FSW groups were originally defined as direct sex workers, mostly brothel-based, and indirect sex workers, at entertainment establishments.11 When Indonesia wished to add waria, a transgender population, to AEM, the transgender compartments were added. They were categorized into 3 groups: those who sold sex, those with casual partners, and those with regular partners only based on the data available in Asian studies at the time.20–23 For male and female populations who inject drugs, they are subdivided into 2 compartments for those in high-risk and low-risk networks. The proportion in the high-risk compartment is set empirically in AEM by matching the saturation prevalence levels seen among PWID in the country.

If desired, most groups can be excluded by setting their size to 0. AEM also allows for movement between the compartments, that is, turnover, based on user-supplied durations of stay in the compartment. As an example, Mongolia uses 1 group of sex workers with a duration of 5.7 years based on recent integrated biological and behavioral surveys.24,25

Simulating the Epidemic: New Infections, Deaths, and Current Infections in AEM

New Infections

AEM calculates HIV transmission as follows: First, each compartment is subdivided into uninfected persons (HIV‒) and persons living with HIV (HIV+). Within each compartment, an equation as shown in Figure 3 moves people from the uninfected to the infected subcompartment.

FIGURE 3.

Conceptual view of new infection calculations in AEM. For each subpopulation and partner type, AEM has a similar equation to estimate new infections in that subpopulation from that partner type.

For example, to calculate new infections among FSW1, start with the number of HIV‒ sex workers, calculate the number of contacts with infected clients (frequency of contacts times client HIV prevalence), remove those protected by condom use giving the number of unprotected contacts, and then multiply those contacts by the probability of transmission from male population to female population for vaginal sex. Then correct for the transmission-enhancing effects of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) for sex workers with an STI by applying an STI cofactor. For female to male transmission, for example, from sex worker to client, a protective circumcision cofactor is applied to reduce transmission. For those on ART, new infections of partners are reduced by user-supplied values for the ART transmission reduction for each major transmission mode.

Mixing Between Model Compartments

Specific interactions that transmit HIV between compartments are specified within the AEM code. For example, clients of sex workers can contract HIV from interactions with both injecting and noninjecting sex workers, wives, wives who are PWID, TGs in all 3 categories, and casual sex with non-KP females. A fuller list of the compartmental interactions allowed is provided at the end of Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/QAI/C136. The frequency of contact is specified in ways related to how data are often collected for the specific population in question. For example, rates of interactions with sex workers are specified in clients per day and days worked per week, which are then used to calculate an annualized rate of contacts. For MSM, the focus is on anal sex as the dominant mode of transmission, so the data are entered as anal sex contacts per week among those having anal sex. See Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/QAI/C136 for more detail on these inputs.

Entries and Exits: Deaths, Turnover, and Shifting Population Sizes

Deaths and movement in and out of the HIV+ and HIV− compartments are then calculated. Those without HIV have only background mortality applied. For people living with HIV, the calculation includes both AIDS and non-AIDS deaths and the effects of ART on survival. The calculation of deaths among people living with HIV (PLHIV) uses an implementation of the CD4 model for HIV progression and ART developed for Spectrum,26 with background mortality for PLHIV obtained from Spectrum. Supplemental Digital Content 1 describes the ART model (Figures 1–3, http://links.lww.com/QAI/C135) and the mortality calculations. Finally, if there is turnover, for example, between FSW and the non-KP female population, AEM moves a fraction each year (defined as 1/duration) from the FSW compartment to the non-KP female compartment. Turnover is applied to both the HIV+ and HIV− subcompartments. Those leaving are replaced with the number of new women from the non-KP needed to match the size estimate for the sex workers in that year. All newly entering 15-year-old individuals are initially placed into the non-KP HIV− compartments.

Initiating an Epidemic in AEM

The epidemic starts with the introduction of 3 strategic HIV infections. Based on the original waves of the epidemic by Weniger et al,27 the user specifies 3 separate start years for heterosexual, injecting, and male same-sex components of the epidemic. In the specified start year, 1 infection is seeded into the client, male PWID, and MSM1 populations, respectively, for each component. A given component of the epidemic may not be delayed until the specified start year if infections cross over from other populations that began their epidemic earlier. For example, epidemics among PWID often seed the heterosexual epidemic when male PWID are clients of sex workers.28

After introducing the initial infections, AEM progresses each compartment in 10th of a year time steps with 1 simple equation:

| (1) |

where is prevalent infections at time , is new infections, is deaths (including both AIDS and non-AIDS deaths), and is the movement in or out of the compartment. Because no HIV is present until initial infections are introduced, no new infections are generated before those introductions. Once any infections enter the system, they generate new infections in every subsequent time step. AEM then progresses the epidemic by calculating new infections, deaths, and movement for each compartment at each time step. These values are then used to calculate current infections in the compartment at the next time step. One of AEM's additional features is that it tracks not only the key indicators (new and current infections and AIDS and non-AIDS deaths) for each compartment but also the sources of infection in that compartment. For each new infection in a compartment, AEM records the compartment of the partner contact that leads to HIV transmission. This allows the calculation of the proportion of new infections in each compartment resulting from contacts with those in other compartments. This information is stored annually, allowing a detailed reconstruction of past epidemic dynamics.

AEM Inputs are Defined by the Needs of the Calculations

The needs of this calculation dictate the key inputs required for each key population.

-

Sexual behavior trends

o Frequency of sex and condom use with different partner types and duration of sex work/clienthood.

-

Injecting behavior trends

o Frequency of injection, percent who share injections, percent of injections shared among those who share injections, and duration of injecting.

Sizes for key populations and national/regional population trends by sex.

-

Biological trends

o HIV prevalence, STI prevalence, and male circumcision levels.

The user enters all trends into the AEM Baseline workbook, an Excel workbook that stores all inputs, fitting parameters, and outputs of an AEM projection. The Baseline workbook serves as a self-contained repository of the entire AEM projection that accurately reproduces the AEM fit. The full set of inputs is entered on several defined Baseline workbook input sheets, for example, one for heterosexuals, another for those who inject, another for MSM, etc. The full set of inputs is too complex to list here, but Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/QAI/C136 summarizes each page's content and provides Baseline workbook screenshots showing the specific inputs. The supplement also discusses the need to ensure that entries are representative of the key population examined. When data are not available, reasonable assumptions can be made but must be documented for transparency. For more information, see the A2 guidelines29 (https://www.fhi360.org/resource/analysis-action-a2-approach).

Prevalence in key populations plays an important role in AEM fitting. Thus, it is critically important that prevalence inputs in the Baseline workbook are representative of the national or regional area being modeled. For each key population and year, 1 prevalence value can be specified. This annual value ideally represents the average national/regional prevalence in that population in the given year. Accordingly, all necessary collation of multiple data sources, cleaning, removal of outliers, calibrations, and other adjustments to data should be completed before this final value is calculated and entered in the workbook.

Fitting the Epidemic: Probabilities, Cofactors, and Start Years

After processing the data and entering input trends, the AEM software is launched from a Baseline workbook menu. AEM reads the workbook inputs and opens a prevalence fitting interface, shown in Figure 4, where the historical prevalence trends in the key populations are compared against calculations from the model.

FIGURE 4.

AEM prevalence fitting interface. The graphs show each of the major populations in AEM with input data in green and the other solid lines being model calculated prevalence. The interface is interactive and dynamic. Because the user adjusts the values in the lower left part of the screen, the model recalculates the prevalence and the model curves in the display adjust automatically.

The graphs show the prevalence in each major AEM population. From the upper left, they are PWID, FSW, MSM and MSW, Non-KP females and males, FSW who inject, clients, transgender persons, and overall male and female population. The green lines show the annual prevalence value inputs from the Baseline workbook, and the solid lines show prevalence calculated by AEM based on supplied behavioral inputs and the start years, and probabilities of transmission and cofactors shown in the lower left of the AEM interface. The following epidemic parameters can be adjusted in the fitting parameters panel at the lower left of Figure 4.

Start years (3): the year in which 1 HIV infection is introduced to each of clients, MSM, and PWID.

Probabilities of transmission (5): two for transmission through vaginal sex male to female (M->F) and female to male (F->M), one for transmission by sharing of injecting equipment, and 2 for anal sex transmission from insertive to receptive partner [Anal(R)] and from receptive to insertive partner [Anal(I)].

Cofactors for HIV transmission (5): two describe the enhancement of heterosexual infection for (1) a male if either partner has an STI (Het M STI) and (2) for a female (Het F STI). The third is an increase in transmission for uncircumcised male population relative to circumcised. The final 2 represent enhancements due to STIs in anal sex for the receptive and insertive partners, respectively.

PHI cofactor: the primary HIV infection (PHI) cofactor is a multiplier on transmission during the first time step after infection.

In practice, users adjust these fitting parameters within scientifically plausible ranges until they obtain a reasonable agreement with observed prevalence trends. The fitting parameters and projection results are then saved from the AEM software and imported into the Baseline workbook. At this point, the Baseline workbook contains the full set of inputs, fitting parameters, and outputs for the projection. Normally at this stage, as part of the process of finalizing the model, users validate their projection against other sources of data: M/F ratios in the country, trends in case reporting, incidence studies among key populations, mortality among those on ART, and other available data in-country. National models are also normally vetted by national AIDS programs and local HIV experts before use in policy exercises. Examples of the key population-specific outputs in the AEM Baseline workbook can be seen in the Results section of this article.

Importing AEM Into Spectrum

The final step is to import the AEM Baseline into Spectrum as an incidence source, performed from Spectrum's AIM menu. This adds value in 3 ways.

• Spectrum provides a full set of pediatric outputs derived from adult incidence and pediatric program data.

• Spectrum calculates key indicators in different age groups, giving countries a picture of evolution of the epidemic by age.

• The Spectrum file with AEM can then be used in the global estimates framework coordinated by UNAIDS.

In the past, the lack of age structure in AEM produced increasing divergence in epidemic trends between Spectrum and AEM over time. However, in the latest AEM versions, steps have been taken to better synchronize Spectrum and AEM. The changes made and the methodology used for this are described briefly below and in detail in Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/QAI/C135.

Recent Changes to AEM: Improving Spectrum–AEM Mortality Alignment and Preexposure Prophylaxis

After AEM 4.0 became a Spectrum incidence source in 2015, it was found that for a given incidence input, Spectrum and AEM would produce different prevalence and PLHIV mortality trends over time. Figure 1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/QAI/C135, shows a comparison for 3 countries when both Spectrum and AEM were restored to the Spectrum 2020 defaults for the CD4 model. Significant differences in the number of AIDS deaths were frequently seen, and although prevalence was generally closer, there were sometimes important differences.

This was not unexpected. The lack of age structure in AEM, where each key population compartment contains everyone older than 15 years, produces the same type of age–sex divergence between Spectrum and AEM known to exist between Spectrum and the non-age–sex-structured version of EPP.26 The source of this divergence is shifts in the age–sex distribution of PLHIV as the epidemic ages. Pre-5.0 versions of AEM used fixed averages of Spectrum CD4 model parameters (distribution of new infections by CD4, on-ART and off-ART mortality rates, and CD4 transition rates) for its internal CD4 model, whereas Spectrum used age–sex–CD4-specific values for each of these parameter sets.

The CD4 model calculates deaths in both AEM and Spectrum. Thus, as the epidemic progresses and the age distribution of people living with HIV shifts to older ages, Spectrum sees an age–sex-dependent evolution in the rate of deaths it is calculating, whereas AEM does not. This applies to both non-AIDS background mortality (background mortality rates increase with age) and HIV-related mortality. Then as deaths diverge, the relationship between new infections and current infections as specified in Equation (1) will change, resulting in the prevalence and death disconnect between the models, shown in Figure 1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/QAI/C135.

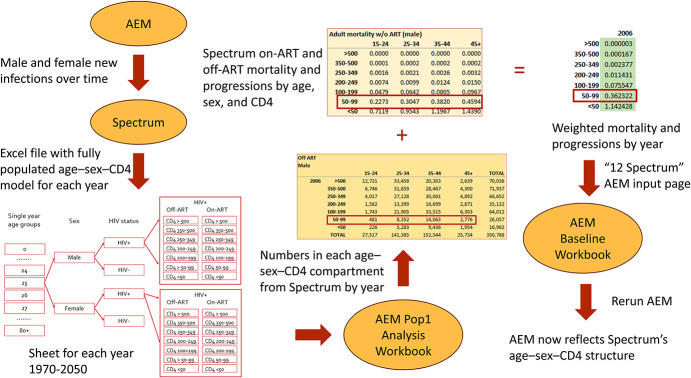

To better align the calculations of death, and therefore prevalence, the fixed CD4 model parameters in earlier versions of AEM were replaced by time-varying parameters for each CD4 and sex compartment in AEM. The approach taken was as follows:

AEM incidence is fed to Spectrum, which then generates a full age–sex–CD4-structured model, populating its own age–sex–CD4 compartments and progressing them through the epidemic according to Spectrum's full set of age–sex and CD4-structured parameters.

This Spectrum distribution of PLHIV in age–sex–CD4 compartments is then captured for each year and outputted to an Excel file.

An AEM auxiliary workbook reads this file and calculates weighted averages of the CD4 transition, mortality, and distribution of new infection parameters from the Spectrum distribution to give time-varying annual parameters for each AEM CD4 and sex compartment. These are entered in the Baseline workbook on a Spectrum input page (see Figure 1–7, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/QAI/C135).

AEM then uses these time-varying parameters in place of its former fixed ones, bringing the calculated deaths between AEM and Spectrum much closer.

Figure 5 illustrates the major steps of this process and its overall flow.

FIGURE 5.

Flow for generating weighted mortality and CD4 progression parameters for creating AEM projections that better reflect the mortalities and progressions produced by the age–sex–CD4 structure of Spectrum. This shows how male off-ART mortalities for 2006 are generated. The same process is repeated in the AEM Pop1 Analysis workbook for each year from 1970 to 2050.

A comparison of Figures 1–8 in Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/QAI/C135 shows the closer alignment of death calculations in Spectrum and AEM with this procedure, but there are still some differences. This is expected because the internal models in AEM and Spectrum are still quite different: Spectrum has a full demographic model; AEM uses a key population structured one. Because new infections occur at different rates in each key population in AEM, whereas Spectrum applies aggregate new infections across a single age–sex-structured demographic model, some differences are expected to arise. The detailed procedure for creating these time-varying parameters is described in Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/QAI/C135.

The newest addition to AEM 5.2, currently being piloted, is preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) by key population. The implementation has been designed to be transparent on its inputs, adaptable as new forms of PrEP develop, and useful as a framework for PrEP discussions in-country. The features are as follows:

The user can define up to 10 forms of PrEP.

Each of AEM's populations can have up to 3 forms of PrEP applied.

Each of these forms has user-provided coverage, efficacy, effective use, and unit cost entries, any of which can be changed on an annual basis if desired. There is also a risk multiplier that can be specified for each population and type of PrEP that describes the elevation of risk among those going onto PrEP.

Changes in condom use and STIs can be specified by population for those on PrEP, although given the challenges in assessing levels of risk compensation and STI change for PrEP users,30,31 countries will be discouraged from using this feature initially.

These values are then used to generate a multiplier, , on the number of susceptibles in each key population, , of

where is the coverage of PrEP type in key population (percentage of the susceptible population receiving PrEP on an annualized basis), is the efficacy (percentage transmission reductions associated with full adherence to the PrEP regimen), and is the effective use (percentage of those on PrEP who use PrEP appropriately during periods of risk to achieve high levels of protection against HIV acquisition). All AEM calculations then use this reduced number of susceptibles, which captures the impact of PrEP on the epidemic.

RESULTS

Thailand first applied AEM as a national model in 2000 and has performed a major update every 5 years since.12,32 The 2023 Thailand projection is shown in Figure 6. It agrees well with the prevalence trends in key populations. This reflects 2 factors: the nationwide coverage of FSW and PWID surveillance throughout much of the epidemic and the high quality of behavioral data generated from extensive behavioral studies over the years. The early MSM projections are low compared with the surveillance, but these early surveillance data are known to come from male sex workers. Only in later years did Thailand establish integrated biological and behavioral surveys among MSM, but still in a limited number of provinces, so the later observed prevalence values have been weighted to be more nationally representative.

FIGURE 6.

Thailand projection for 2023 in AEM. The agreement with key population prevalence data is good, except for pre-2000 MSM surveillance, which was high because it was predominantly in male sex workers.

Figure 7 shows the evolving key population distribution of new and current infections because the 100% condom program rapidly reduced new infections among clients in the early 1990s, after which husband-to-wife transmission came to dominate in the early 2000s (infections among non-KP females, largely spouses of clients and exclients). In recent years, MSM transmission and spousal transmission dominate, as shown in the AEM source of infection graphs in Figure 8. The preponderance of current infections among non-key populations in 2023 often leads people to think most of the transmission is occurring there, but the current infections largely reflect turnover of former key population members and transmission from key population members to spouses and regular partners over the years. For fuller discussion of this issue see Brown and Peerapatanapokin.33

FIGURE 7.

Dynamic evolution of new infections in Thailand by key population groups as seen in current (left graph) and new (right graph) infections in AEM. The early dominance of infections among clients and PWID was quickly overtaken by husband-to-wife transmission (non-KP F) from clients and ex-clients as the 100% condom use program drove down infections in sex work.

FIGURE 8.

AEM distribution of new infections (left) and source of infection graphs (right) for Thailand in 2023. A combination of male same-sex, spousal, and casual sex transmission dominates new infections.

The AEM results, combined with strong data systems, have informed Thai national strategic plans and helped adapt Thailand's responses as the epidemic evolved. Shifting from the 100% condom emphasis in the 1990s, today's prevention response is focused heavily on male same-sex and spousal transmission. However, AEM modeling has helped the country recognize they will not achieve the end of AIDS without also addressing other routes of transmission including casual sex. Although beyond the scope of this article, AEM also provides Intervention and Impact Analysis workbooks that can provide an organizing framework for strategic planning discussions and help evaluate alternative responses (see Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/QAI/C137).

DISCUSSION

Strengths and Limitations of AEM

The diversity of inputs required by AEM is a limitation. Collecting and analyzing these data for the first time to produce representative trends is a time-consuming undertaking, especially in the data-rich environments of Asia. Thus, first-time AEM applications in countries typically take 6 months to a year, normally through a series of workshops. Later updates are quicker because only the most recent epidemiological, behavioral, and program data need to be added and the model refit. One of the challenges of the depth and intensity of the data analysis is that documentation is often not well-maintained, especially when time-challenged national staff are doing the fitting, and the origins of some input trends have been lost. AEM also has a limited value in countries with poor data systems or a limited time-series of data, although this has not been an issue in most of Asia.

At present AEM fitting is performed manually, which produces less than optimal fits. Preliminary versions of an IMIS fitting algorithm have been implemented like those in EPP,34,35 but they typically require several hours to run. The fit in Figure 4 was made with this version. Further coding work and fast external servers are likely needed to make this feature more widely available to countries. The manual nature of current fits makes it important to validate the resulting model against as many external sources of information as possible, and AEM training stresses this strongly.

Sustaining in-country AEM capacity has been challenging. AEM has a steep learning curve because it requires working with the full range of epidemiological, behavioral, and program data, using the workbooks and software, and interpreting the results. Some countries have successfully built strong and sustained national AEM teams, experienced in data analysis, skilled at working with AEM, and able to prepare scenarios on their own. Others have had issues with staff turnover and depend to a significant extent on external support.

With that said, AEM has many strengths. The ability to track sources of infection throughout the epidemic allows it to build understanding of epidemic dynamics in complex epidemics. It lets countries see the evolving sources of new infections and use them to adapt programs appropriately. Used in projection/intervention mode, as described in Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/QAI/C137, AEM can also be used to evaluate the impact of past responses and assess the effects of alternative future resource allocation strategies among key populations. Two of its major applications have been to national strategic planning and optimizing the impacts of donor funding proposals. The AEM process itself has been designed to engage numerous stakeholders at every step along the way and this serves the valuable function of exposing more people to the data and models, thus improving their understanding of the epidemic and the potential impacts of response alternatives.

AEM also serves an inherent triangulation function. Because it depends on both behavioral and prevalence inputs, they provide checks on one another. For example, if the trend of condom use in sex work is incorrect, AEM will not be able to reproduce the prevalence trends observed among sex workers. During the AEM process, these types of discrepancies often encourage closer review of problematic inputs, expanded data collection efforts, and improvements to the inputs.

Increasingly, countries such as Myanmar, Bangladesh, Thailand, and the Philippines are moving to subnational AEM models at the regional or provincial levels. Several of these countries have replaced national models with a combination of regional models, giving more granular information for targeting responses. Work is currently being conducted in Thailand to systematize this process with input databases across provinces, making it easier to generate models at multiple levels (national, regional, and provincial).

Areas for Future Improvement and Adaptation

There are several areas for future improvement. AEM was formulated in the era before uncertainty analysis was generally expected, as such it lacks an inherent capacity to estimate uncertainties around fits. This capability will be built into future versions of AEM, in conjunction with the finalization of the IMIS fitting routines.

Better and simpler to use tools are needed for working with multiple projections at the subnational level. Like Sub-Saharan African countries, Asian countries are rapidly moving to subnational models. A set of more systematic tools for more easily aggregating results and exploring regional contributions has been developed in the past year and has been shared with the AEM country teams.

There are several other features now under consideration including

adding in migration for PLHIV in AEM as Spectrum does,

developing approaches to better quantify cumulative key population turnover and present downstream impacts to help decision makers visualize the important role key populations play in current epidemics,33 and

developing report templates for inputs, outcomes, and scenarios to make documentation easier to generate and maintain in an updated fashion.

A longer term prospect is building age structure directly into AEM, but this will need to take into consideration future unified model development by UNAIDS and its partners.

CONCLUSIONS

AEM has proven a useful tool for national epidemic modeling in many Asian countries. Despite its more intense data requirements compared with curve-fitting models such as EPP, which require mainly prevalence and population size data, countries recognize the value of AEM in providing unique insights into the dynamics of key population-centered epidemics that help them target responses appropriately. This has driven its expansion to 13 Asian countries at present, with AEM work increasingly moving to subnational levels.

To support this effort, the AEM team continues to develop new tools for combining subnational projections, comparing scenarios, and preparing analyses. The team also adapts the AEM software to meet evolving needs. When sex workers who injected were found to be at substantially higher prevalence in Ho Chi Minh City,36 compartments were added to the model for this group. The need to focus more attention on and expand services for waria in Indonesia37 and the high prevalence observed in surveillance of transgender persons38 led to adding transgender compartments to the model. To address the divergence between Spectrum and AEM results over time, the approach described herein of adjusting AEM mortality and progression parameters over time to synchronize with Spectrum was developed. AEM has continuously evolved to meet country and global estimate needs.

Over the next few years, the UNAIDS Reference Group on Estimates, Modelling, and Projections is seeking to guide global estimates modeling in the direction of a comprehensive tool for country use that will incorporate multiple data sources, consolidate different modeling approaches, and provide more in-depth outputs. This future unified tool development would benefit from incorporating source of infection tracking as a core feature as AEM applications have demonstrated countries' strong interest in understanding epidemic dynamics. Next-generation tools must meet not only the needs of the global estimates process but also the needs of countries for concrete policy and program analyses. This has been a major driver of AEM adoption in Asia. The capacity to conduct such analyses should be a central feature in the design and development of next-generation tools.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of numerous donors for the development and application of AEM over the years. These donors have included the US Agency for International Development; UNAIDS; Family Health International; Avenir Health; the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria; the World Bank; the World Health Organization; and the East-West Center. The authors wish to express their deepest appreciation to their Asian country counterparts who apply AEM in their own national and subnational modeling work. Without them, the national AEM models discussed here would not exist. Their hard work, feedback, and suggestions have helped to continuously improve AEM and its associated tools for the past two decades. The authors thank the members of the UNAIDS Reference Group on Estimates, Modeling, and Projections for their inputs and guidance during the process of incorporating AEM projections into the global estimates process and during the recent work to better synchronize Spectrum and AEM.

Footnotes

Agencies providing support to the development and country application of AEM, which spans 2 and a half decades, include the US Agency for International Development; UNAIDS; Family Health International; Avenir Health; the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria; the World Bank; the World Health Organization; and the East-West Center.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

W.P., T.B., and R.P. have been the primary coders of the AEM software in Java. W.P. and T.B. implemented the first version in 1998, whereas R.P. implemented the current interface in AEM 5.2, consolidating input mechanisms and internal data structures. NS has been the primary developer of the AEM workbooks in Excel, based on extensive input from users in the field, with assistance from W.P. and T.B. All 4 authors have assisted in regional and national training workshops and in-country applications of AEM with national counterparts. T.B. wrote the initial draft of the paper, but all authors have provided their input and revisions for the final version. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (www.jaids.com).

Contributor Information

Wiwat Peerapatanapokin, Email: wiwat@hawaii.edu.

Nalyn Siripong, Email: nas230@pitt.edu.

Robert Puckett, Email: puckettr@eastwestcenter.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown T, Peerapatanapokin W. The Asian Epidemic Model: a process model for exploring HIV policy and programme alternatives in Asia. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(suppl 1):i19–i24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chin J, Bennett A, Mills S. Primary determinants of HIV prevalence in Asian-Pacific countries. AIDS. 1998;12(suppl B):S87–S91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills S, Saidel T, Bennett A, et al. HIV risk behavioral surveillance: a methodology for monitoring behavioral trends. AIDS. 1998;12(suppl 2):S37–S46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mills S, Ungchusak K, Srinivasan V, et al. Assessing trends in HIV risk behaviors in Asia. AIDS. 1998;12(suppl B):S79–S86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amon J, Brown T, Hogle J, et al. Behavioral Surveillance Surveys (BSS): Guidelines for Repeated Behavioral Surveys in Populations at Risk of HIV. Arlington, TX: Family Health International; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mills S, Saidel T, Magnani R, et al. Surveillance and modelling of HIV, STI, and risk behaviours in concentrated HIV epidemics. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(suppl 2):ii57–ii62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aceijas C, Friedman SR, Cooper HL, et al. Estimates of injecting drug users at the national and local level in developing and transitional countries, and gender and age distribution. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(suppl 3):iii10–iii17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caceres C, Konda K, Pecheny M, et al. Estimating the number of men who have sex with men in low and middle income countries. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(suppl 3):iii3–iii9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vandepitte J, Lyerla R, Dallabetta G, et al. Estimates of the number of female sex workers in different regions of the world. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(suppl 3):iii18–iii25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loo V, Saidel T, Reddy A, et al. HIV surveillance systems in the Asia Pacific region. Western Pac Surveill Response J. 2012;3:9–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Cambodia Working Group on HIV/AIDS Projection, NCHADS . Projections for HIV/AIDS in Cambodia: 2000–2010. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: NCHADS; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thai Working Group on HIV/AIDS Projection . Projections for HIV/AIDS in Thailand: 2000–2020. Bangkok, Thailand: Thailand Ministry of Public Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahy M, Brown T, Stover J, et al. Producing HIV estimates: from global advocacy to country planning and impact measurement. Glob Health Action. 2017;10:1291169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stover J. Projecting the demographic consequences of adult HIV prevalence trends: the Spectrum Projection Package. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(suppl 1):i14–i18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stover J, Glaubius R, Kassanjee R, et al. Updates to the spectrum/AIM model for the UNAIDS 2020 HIV estimates. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(suppl 5):e25778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eaton JW, Brown T, Puckett R, et al. The estimation and projection package age-sex model and the r-hybrid model: new tools for estimating HIV incidence trends in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2019;33(suppl 3):S235–S244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghys PD, Brown T, Grassly NC, et al. The UNAIDS estimation and projection package: a software package to estimate and project national HIV epidemics. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(suppl 1):i5–i9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stover J, Brown T, Puckett R, et al. Updates to the spectrum/estimations and projections package model for estimating trends and current values for key HIV indicators. AIDS. 2017;31(suppl 1):S5–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fazito E, Cuchi P, Mahy M, et al. Analysis of duration of risk behaviour for key populations: a literature review. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(suppl 2):i24–i32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chariyalertsak S, Kosachunhanan N, Saokhieo P, et al. HIV incidence, risk factors, and motivation for biomedical intervention among gay, bisexual men, and transgender persons in Northern Thailand. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pisani E, Girault P, Gultom M, et al. HIV, syphilis infection, and sexual practices among transgenders, male sex workers, and other men who have sex with men in Jakarta, Indonesia. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:536–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prabawanti C, Bollen L, Palupy R, et al. HIV, sexually transmitted infections, and sexual risk behavior among transgenders in Indonesia. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:663–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Safika I, Johnson TP, Cho YI, et al. Condom use among men who have sex with men and male-to-female transgenders in Jakarta, Indonesia. Am J Mens Health. 2014;8:278–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erdenetungalag E Oyunjargal M Mandal O, et al. AIDS Epidemic Model Report of Mongolian HIV/AIDS Prevention Program Impact Analysis, 2018. Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia: Mongolia National Center for Communicable Disease; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO, CDC, UNAIDS, FHI 360 . Biobehavioral Survey Guidelines for Populations at Risk for HIV. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stover J, Brown T, Marston M. Updates to the spectrum/estimation and projection package (EPP) model to estimate HIV trends for adults and children. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(suppl 2):i11–i16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weniger BG, Limpakarnjanarat K, Ungchusak K, et al. The epidemiology of HIV infection and AIDS in Thailand. AIDS. 1991;5(suppl 2):S71–S85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saidel T, Des Jarlais DC, Peerapatanapokin W, et al. Potential impact of HIV among IDUs on heterosexual transmission in Asian settings: scenarios from the Asian Epidemic Model. Int J Drug Policy. 2003;14:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- 29.The A2 Partners . From Analysis to Action: The A2 Approach. Bangkok, Thailand: FHI, EWC, RTI and Futures Group International; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holt M, Murphy DA. Individual versus community-level risk compensation following preexposure prophylaxis of HIV. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:1568–1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quaife M, MacGregor L, Ong JJ, et al. Risk compensation and STI incidence in PrEP programmes. Lancet HIV. 2020;7:e222–e223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thai Working Group on HIV/AIDS Projection . The Asian Epidemic Model (AEM) Projections for HIV/AIDS in Thailand: 2005–2025. Bangkok, Thailand: FHI and Bureau of AIDS, TB and STIs, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown T, Peerapatanapokin W. Evolving HIV epidemics: the urgent need to refocus on populations with risk. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2019;14:337–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown T, Bao L, Raftery AE, et al. Modelling HIV epidemics in the antiretroviral era: the UNAIDS Estimation and Projection package 2009. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(suppl 2):ii3–ii10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raftery AE, Bao L. Estimating and projecting trends in HIV/AIDS generalized epidemics using incremental mixture importance sampling. Biometrics. 2010;66:1162–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen AT, Nguyen TH, Pham KC, et al. Intravenous drug use among street-based sex workers: a high-risk behavior for HIV transmission. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:15–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poudel KC, Jimba M. HIV care continuum for key populations in Indonesia. Lancet HIV. 2018;5:e539–e540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baral SD, Poteat T, Stromdahl S, et al. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]