Abstract

The maintenance of stable mating type polymorphisms is a classic example of balancing selection, underlying the nearly ubiquitous 50/50 sex ratio in species with separate sexes. One lesser known but intriguing example of a balanced mating polymorphism in angiosperms is heterodichogamy - polymorphism for opposing directions of dichogamy (temporal separation of male and female function in hermaphrodites) within a flowering season. This mating system is common throughout Juglandaceae, the family that includes globally important and iconic nut and timber crops - walnuts (Juglans), as well as pecan and other hickories (Carya). In both genera, heterodichogamy is controlled by a single dominant allele. We fine-map the locus in each genus, and find two ancient (>50 Mya) structural variants involving different genes that both segregate as genus-wide trans-species polymorphisms. The Juglans locus maps to a ca. 20 kb structural variant adjacent to a probable trehalose phosphate phosphatase (TPPD-1), homologs of which regulate floral development in model systems. TPPD-1 is differentially expressed between morphs in developing male flowers, with increased allele-specific expression of the dominant haplotype copy. Across species, the dominant haplotype contains a tandem array of duplicated sequence motifs, part of which is an inverted copy of the TPPD-1 3’ UTR. These repeats generate various distinct small RNAs matching sequences within the 3’ UTR and further downstream. In contrast to the single-gene Juglans locus, the Carya heterodichogamy locus maps to a ca. 200–450 kb cluster of tightly linked polymorphisms across 20 genes, some of which have known roles in flowering and are differentially expressed between morphs in developing flowers. The dominant haplotype in pecan, which is nearly always heterozygous and appears to rarely recombine, shows markedly reduced genetic diversity and is over twice as long as its recessive counterpart due to accumulation of various types of transposable elements. We did not detect either genetic system in other heterodichogamous genera within Juglandaceae, suggesting that additional genetic systems for heterodichogamy may yet remain undiscovered.

Keywords: heterodichogamy, walnut, pecan, Juglandaceae, Juglans, Carya, supergene, trans-species polymorphism, balanced polymorphism, T6P, trehalose phosphate phosphatase, flowering time, structural variation

Introduction

Flowering plants have evolved a remarkable diversity of sexual heteromorphisms (e.g. dioecy, heterostyly, gynodioecy, and mirror-image flowers) that have long fascinated evolutionary biologists (Darwin 1877; Charlesworth and Charlesworth 1979; Barrett 2010). Such systems present key opportunities to test evolutionary theories of sexual reproduction and to understand its ecological and genetic consequences. Heterodichogamy presents an intriguing and relatively under-explored example of a balanced polymorphism in the sexual organization of some angiosperms, in this case not in space but in time. In Darwin’s words, heterodichogamous populations “consist of two bodies of individuals, with their flowers differing in function, though not in structure; for certain individuals mature their pollen before the female flowers on the same plant are ready for fertilisation and are called proterandrous [protandrous]; whilst conversely other individuals, called proterogynous [protogynous], have their stigmas mature before their pollen is ready”(1877). This system generates strong disassortative mating between morphs (Bai et al. 2007), thus classical sex ratio theory predicts a 50/50 ratio of protandrous and protogynous individuals at equilibrium (Gleeson 1982). Although heterodichogamy has likely evolved at least a dozen times in angiosperms (Renner 2001; Endress 2020), to our knowledge the genetic loci controlling the inherited basis of this mating system have not been described at the molecular level in any species. Thus, it is not known whether similar genetic mechanisms control heterodichogamy in different taxa, nor whether the loci involved experience similar evolutionary dynamics as sex chromosomes and other supergenes that underpin other complex mating polymorphisms (Charlesworth 2016; Gutiérrez-Valencia et al. 2021).

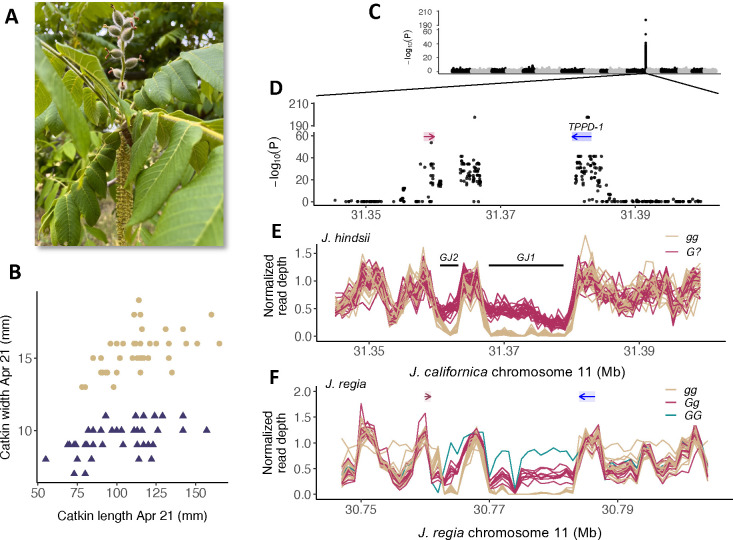

Heterodichogamy is well-known within Juglandaceae (Delpino 1874; Darwin 1876; Pringle 1879; Stuckey 1915, Fig. 1A,B), the family that includes two major globally important nut and timber-producing groups of trees - the walnuts (Juglans) and hickories (Carya, includes cultivated pecans). The ancestor of Juglandaceae evolved unisexual, wind-pollinated flowers from an ancestor with bisexual flowers near the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary (Friis 1983; Sims et al. 1999), and a rich fossil history shows a radiation of Juglandaceae during the Paleocene (Manchester 1987, 1989). In both walnuts and hickories, protogyny is inherited via a dominant Mendelian allele (dominant allele - G, recessive allele - g, Gleeson 1982; Thomp- son and Romberg 1985). Other genera phylogenetically closer to Juglans (Cyclocarya, Platycarya) are also known to be heterodichogamous (Fukuhara and Tokumaru 2014; Mao et al. 2019). These observations have suggested a single origin of the alleles controlling heterodichogamy in the common ancestor of these taxa. Here, we identify and characterize the evolutionary history of the genetic loci controlling heterodichogamy in both Juglans and Carya. We find two distinct and substantively different genetic underpinnings for heterodichogamy in these genera, and show that each genetic system is an ancient trans-species balanced polymorphism for a structural variant.

Figure 1:

A) A protogynous individual of J. ailantifolia with developing fruits and catkins that are shedding pollen. Photo by JSG. B) Protandrous (tan) and protogynous (dark blue) morphs of J. hindsii are readily distinguished by catkin size in the first half of the flowering season. C) GWAS of flowering type in 44 individuals of J. hindsii from a natural population, against a long-read assembly of the sister species, J. californica. D) The GWAS peak occurs across and in the 3’ region of TPPD-1, a probable trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase gene (blue rectangle, arrow indicates direction of transcription). Red bar shows the position of a NDR1/HIN1 -like gene. E) Normalized average read depth in 1 kb windows for 44 J. hindsii from a natural population against a genome assembly for J. californica. Black bars show positions of identified indels. F) Normalized average read depth in 1 kb windows for 26 J. regia individuals in the region syntenic with the J. hindsii G-locus. Colored bars and arrows indicate positions of orthologous genes bordering the G-locus.

Ancient regulatory divergence controls heterodichogamy across Juglans

In a natural population of Northern California black walnut (J. hindsii), protandrous and protogynous morphs were found to occur in roughly equal proportions (43 vs. 38, P=0.47 under null hypothesis of equal proportions). A genome-wide association study (GWAS) for dichogamy type in this population recovered a single, strong association peak, consistent with the known Mendelian inheritance of heterodichogamy type in Juglans (Fig. 1C, Gleeson 1982). This region is syntenic with the top GWAS hit location for dichogamy type in J. regia (Fig. S1, Bernard et al. 2020) as well as a broad region associated with dichogamy type in J. nigra (Chatwin et al. 2023). The association peak extends roughly 20 kb (hereafter, the G-locus) across a probable trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase gene (TPPD-1, Fig. 1D, corresponding to LOC108984907 in the Walnut 2.0 assembly). TPPs catalyze the dephosphorylation of trehalose-6-phosphate to trehalose as part of a signaling pathway essential for establishing regular flowering time in Arabidopsis (Wahl et al. 2013) and inflorescence architecture in maize (Satoh-Nagasawa et al. 2006). TPP genes were recently identified as differentially expressed across the transition to flowering in both J. sigillata and J. mandshurica (Lu et al. 2020; Li et al. 2022b). In J. regia, TPPD-1 is expressed in a broad range of vegetative and floral tissues (Fig. S2), and we detected full-length transcripts from multiple tissues related to flowering in J. regia homozygotes for both G-locus haplotypes (Table S2). Consistent with the width of the GWAS hit, we observed strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) extending across this region, suggesting locally reduced recombination in the genealogical history of the sample for both J. hindsii and J. regia (Fig. S3).

We identified copy number variation consistent with three >1 kb indels distinguishing G-locus haplotypes (GJ1 and GJ2 present in the G haplotype; gJ3 in the g haplotype, Figs. 1E, S1). Consistent with the known dominance, all J. hindsii protogynous individuals (G?) appear to be hemizygous for these indels, while protandrous individuals (gg) are homozygous for gJ3. The apparent absence of any homozygotes for the G haplotype in our J. hindsii sample is consistent with disassortative mating at the G-locus in a natural population (P=0.059). Strikingly similar copy number patterns were seen in J. regia (Fig. 1F, S1), with a known homozygote for the protogynous allele (‘Sharkey’, GG, Gleeson 1982) lending further support for these indels. To look for the presence of this structural variant across Juglans species, we generated whole-genome resequencing data from both morphs from 5 additional Juglans species (Table S1) combined with existing data from known morphs in two additional species (Stevens et al. 2018). Parallel patterns of read depth at the G-locus indicate that the same structural variant segregates in perfect association with dichogamy type across all nine species examined (Fig. 1F, S4). As our species sampling spans the deepest divergence event in the genus (Manchester 1987; Mu et al. 2020), this suggested that the G-locus haplotypes may have diverged in the common ancestor of Juglans.

Consistent with the Juglans G-locus being an ancient balanced polymorphism, nucleotide divergence between G-locus haplotypes is exceptionally high compared to the genome-wide background (falling in the top 1% of values across the entire aligned chromosome in several species, Fig. 2D), and is comparable to the divergence observed between Juglans and Carya in the same region (Fig. S6). Applying a molecular clock, we estimated the age of the G-locus haplotypes to be 41–69 Mya (methods). As both fossil and molecular evidence place the most recent common ancestor of Juglans in the Eocene (Manchester 1987; Mu et al. 2020; Zhou et al. 2021), this estimate is consistent with G-locus haplotypes originating in the common ancestor of extant Juglans.

Figure 2:

A) Schematic of the G-locus structural variant in Juglans. Presence/absence of indels are indicated by continuous lines vs. open parentheses. Maroon and blue bars show bordering genes. Black arrow across TPPD-1 indicates direction of transcription. Colored arrows represent subunits of the repeat motif within the GJ1 indel and paralogous sequence outside of the indel. Each repeat motif (numbered 1,2,...) is comprised of subunits a, b, and c. Subunit a, which is homologous with the 3’ UTR of TPPD-1, is inverted within the indel. B) Dotplots showing pairwise alignment of alternate haplotypes for three species representing the major clades within the genus. Maroon and blue rectangles indicate the locations of the genes bordering the G-locus as in (A). C) Phylogeny of GJ1 repeats. Sample codes from L-R indicate: haplotype (for Juglans only), abbreviated binomial, optional additional identifier, and repeat number (as in A) (see Table S3 for full taxon list and data sources). Sequences from g haplotypes (gold) and G haplotypes (blue) form two sister clades (*, 99% bootstrap support) whose most recent common ancestor predates the radiation of Juglans. Daggers and diamonds highlight representative sequences from J. californica and J. regia that show the trans-species polymorphism. D) Average nucleotide divergence in 500 bp windows between alternate G-locus haplotypes for three within-species comparisons. Dotted gray lines indicate the chromosome-wide average, and shaded gray regions indicate 95% quantiles. Maroon and blue bars indicate positions of genes as in (A).

We next examined variation within the TPPD-1 gene sequence. In a comparison of both haplotypes from three species spanning the earliest divergence events within Juglans, we find several genus-wide trans-specific polymorphic SNPs within the 3’ UTR of TPPD-1, but none within coding sequence, indicating recombination over deep timescales and a lack of shared functional coding divergence (Fig. S5B). However, we see numerous coding polymorphisms that are fixed differences between haplotypes within species and that are shared across more closely related species (Fig. S5C), suggesting the intriguing possibility of recruitment and turnover of functional divergence within the TPPD-1 gene sequence.

We next investigated the three indels between the G and g haplotypes (Fig. 2A). The indels GJ2 and gJ3 are not obvious functional candidates. For example, gJ3 is derived from an insertion of a CACTA-like DNA transposon in g haplotypes of Juglans, which lacks evidence of gene expression or strong sequence conservation across species (Fig. S7). Nonetheless, given their conserved presence it seems plausible that these indels have some role in the establishment of dichogamy types.

Turning to the GJ1 indel closer to TPPD-1, using pairwise alignments we found that GJ1 contains a series of ~1kb tandem repeats that are paralogous with sequence in the 3’ region of TPPD-1 (Fig. 2A,B). We find no evidence for the inclusion of the repeat in full length TPPD-1 transcripts from a GG J. regia individual. Each repeat, ordered GJ1–1 up to GJ1–12 moving downstream of TPPD-1, consists of three subunits. One subunit (GJ1a) is an inverted ~250–300bp motif homologous with the 3’ UTR of TPPD-1. The other two subunits (GJ1b and GJ1c) are non-inverted ~300bp motifs homologous with regions within 1kb downstream of the 3’ UTR. These tandem duplicates are present in G haplotypes across multiple species with long read assemblies, varying in number from 8–12 copies (Fig. 2B). Consistent with G-locus haplotypes having arisen in the ancestor of Juglans, a maximum-likelihood phylogeny of concatenated aligned sequence from GJ1 repeats and their homologous sequence immediately downstream of the TPPD-1 (Table S3) shows that all G haplotype sequences form a sister clade to all g haplotype sequences (Fig. 2C). Among more closely related species (J. microcarpa and J. californica, ~5–10 Mya species divergence) we found evidence of conservation of specific repeats, with some repeats from the same relative positions in different species clustering together in the phylogeny. On the other hand, for deeper divergences (~40–50 Mya species divergence), evolution of GJ1 repeats is characterized by lineage-specific turnover due to expansion and contraction of the repeat array and/or possible gene conversion. For example, the majority of repeats within J. regia are most closely related to repeats at other positions within the same species, and likewise for J. mandshurica.

The developmental basis of heterodichogamy in J. regia is driven by a differential between protogynous and protandrous morphs in the extent of both male and female floral primordia differentiation in the growing season prior to flowering (Luza and Polito 1988; Polito and Pinney 1997). Correspondingly, we found that protandrous and protogynous morphs of J. regia differ in the size of male catkin buds by mid-summer (Fig. S9). Given the conserved non-coding G haplotype indels, and the lack of Juglans-wide trans-specific coding polymorphism in TPPD-1, we hypothesized that the developmental differential between dichogamy types may be due to differential regulation of TPPD-1 during early floral development. We reanalyzed RNA-seq data collected from male and female flower buds of J. mandshurica, where a TPP gene was one of a number of differentially expressed genes over the course of flowering (Li et al. 2022b). Across two separate J. mandshurica datasets (Qin et al. 2021; Li et al. 2022b), the TPPD-1 ortholog shows increased expression in male buds from samples with protogynous genotypes (Figs. S10, S11). Allelic depth at G-locus SNPs in these data indicated that this is driven by higher allele-specific expression of the G haplotype TPPD-1 (Figs. S10, S11). We found a parallel bias in allele expression in transcriptomic data from multiple tissues of a single individual of J. regia that is heterozygous at the G-locus (Fig. S12) (Dang et al. 2016). To explore possible mechanisms by which variation at the G-locus might regulate TPPD-1 expression, we screened publicly available small RNA sequence libraries from male and female floral buds of a protandrous and protogynous morph in J. mandshurica (Li et al. 2023). We found numerous 18–24 bp small RNAs in protogynous male buds (fewer in female buds and none in a protandrous sample) that map to various repeats within the GJ1 indel and downstream of the coding region of TPPD-1 (Figs. S13, S14). The most abundant of these small RNAs maps to the GJ1c subunit, at a conserved site among repeats across species, with the small RNA closely matching a G haplotype sequence just downstream of the 3’ UTR that is absent from g haplotypes (Fig. S15). A number of the other distinct small RNAs sequences show perfect sequence matching with the 3’ UTR of TPPD-1; some matching both G-locus alleles, and some that match only G alleles (Fig. S16).

Taken together, multiple independent lines of evidence support that the control of dichogamy type in Juglans is governed by TPPD-1 regulatory variation that predates the radiation of the genus: (1) the genus-wide balanced polymorphism of the array of (≥8) 3’ UTR homologous repeats, (2) the production of small RNAs by this G haplotype repeat unit matching sites within and downstream of the 3’ UTR, (3) and differences in TPPD-1 expression between the morphs due to higher allele-specific expression of the G haplotype TPPD-1. (4) Finally, the presumed substrate of TPPD-1, T6P, has been found in model systems to play a critical role in regulating the transition to flowering. In Arabidopsis for instance, overexpression of a heterologous TPP delays flowering (Schluepmann et al. 2003), as does knock down of a T6P synthase gene (Wahl et al. 2013). These facts are consistent with the idea that higher expression of TPPD-1 in developing male flowers of protogynous walnuts could be responsible for delayed male flowering. While the mechanistic basis of the expression difference is not clear, we note that some small RNA pathways upregulate gene expression (Li et al. 2006; Shibuya et al. 2009; Fröhlich and Vogel 2009). Further investigation of the functional role of these RNAs is clearly warranted, given an emerging view of the general importance of small RNAs in plant sex-determining systems (Akagi et al. 2014; Müller et al. 2020).

Finally, we note that while the divergence of G-locus haplotypes predates the Juglans radiation, our phylogeny inference suggests it is more recent than the divergence of Juglans with its closest cousins, Pterocarya and Cyclocarya, and the relationships of non-Juglans sequences resemble previously estimated species trees for these taxa (Fig. 2C). Consistent with this, we found no evidence of the G-locus structural variant in resequencing data from multiple individuals from each of Cyclocarya, Pterocarya, and Platycarya (Fig. S8).

A supergene controls heterodichogamy in Carya

While heterodichogamy has been suggested as the ancestral state of Juglandaceae, our results indicate that the Juglans G-locus is specific to walnuts. To identify the basis of the trait in pecan (C. illinoinensis), we generated whole-genome resequencing data from 18 pecan varieties of known dichogamy type and combined these with existing data for 12 additional varieties (Xiao et al. 2021) to perform a GWAS for dichogamy type. We identified a single peak of strong association at a locus on chromosome 4, with many alleles in strong LD (Fig. 3, S17), consistent with previous QTL mapping (Bentley et al. 2019). This pecan G-locus region is not homologous with the Juglans G-locus, implying either convergent origins of heterodichogamy within Juglandaceae, or a single origin followed by turnover in the underlying genetic mechanism.

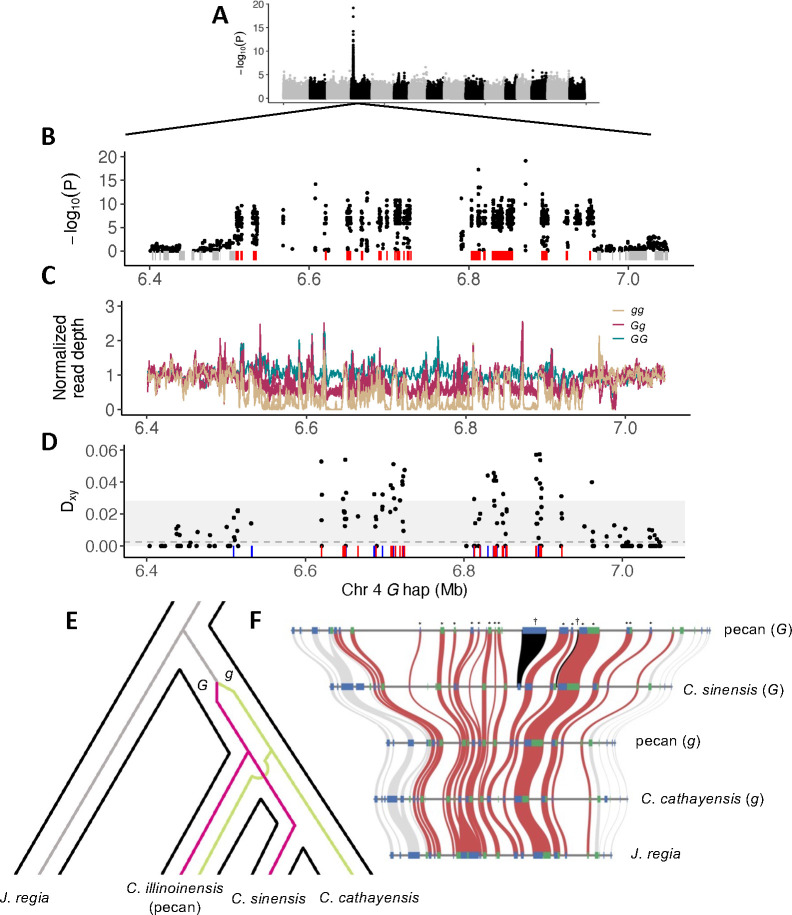

Figure 3:

The G-locus in Carya. A) GWAS for dichogamy type in 30 pecan varieties identifies a single peak of strong association on chromosome 4. B) Zoomed in view of the GWAS peak. Boxes underneath plot indicate positions of predicted genes. Red boxes are those that fall within the region of strong association. C) Normalized average read depth in 1 kb windows across the location of the GWAS hit reveals a structural variant segregating in perfect association with dichogamy type. D) Nucleotide divergence between G-locus haplotypes within coding sequence is strongly elevated against the genome-wide background. Dotted line shows the genome-wide average for coding sequence, shaded interval shows 99% quantile. Colored tick marks at bottom show locations where other Carya species are heterozygous for SNPs that are fixed between pecan G-locus haplotypes. Blue - North American, red - East Asian. E) The phylogeny of the G-locus is discordant with the species tree, reflecting trans-species polymorphism. Carya G-locus haplotypes diverged after the split with Juglans and were present in the most recent common ancestor of Carya. F) Gene-level synteny for assemblies of both G-locus haplotypes in pecan and East Asian Carya, and J. regia. G haplotypes are longer than g haplotypes in both major Carya clades due to accumulation of transposable elements. Colored boxes show positions of genes in each assembly, with color indicating the strand (blue - plus, green - minus). Red bands connect orthologous genes that fall within the GWAS peak in pecan; gray bands connect genes outside the region. Individual gene trees that support the trans-species polymorphism are indicated with asterisks along the top. Black bands and daggers indicate two genes that appear to be uniquely shared by North American and East Asian G haplotypes.

We identified a large segregating structural variant in pecan (445 kb in the primary haplotype-resolved assembly of ‘Lakota’, Gg diploid genotype) overlapping the location of the GWAS peak that is perfectly associated with dichogamy type (Fig. 3C), and confirmed the genotype of two known protogynous allele homozygotes (GG), ‘Mahan’ and ‘Apache’ (Thompson and Romberg 1985; Bentley et al. 2019). Coverage patterns indicated the primary assembly of ‘Lakota’ is of the G haplotype. Consistent with this, coverage patterns against the alternate assembly of ‘Lakota’ and against the reference assembly of ‘Pawnee’ (protandrous, gg) identified both as g haplotype assemblies (Fig. S20).

In contrast to the Juglans G-locus, the Carya G-locus contains approximately 20 predicted protein-coding genes (Fig. 3B, red boxes, Table S4). Gene-level synteny is highly conserved between the Carya G-locus haplotypes (Fig. 3F). Segregating copy number variation is largely localized to intergenic regions, though we see several indels within coding sequence (Fig. S18). Several of these genes have well-characterized homologs involved in flowering (e.g. FIL1, EMS1, SLK2, CEN, see Table S4) with plausible roles in the development of alternate dichogamy types. We found 237 nonsynonymous fixed differences between the pecan haplotypes across these 20 genes, suggesting many potential functional candidates. However, applying the McDonald-Kreitman test to each gene, the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitutions vs. polymorphisms did not identify any signals of adaptive evolution. We note however that two of these genes with annotated functional roles in flowering, EMS1 and FIL1, were previously identified in a small set of highly differentially expressed genes between male catkin buds of protandrous and protogynous cultivars in the season prior to bloom near when a differential in anther development is first established (Rhein et al. 2023). Arabidopsis mutants of EMS1 fail to form pollen tetrads (Zhao et al. 2002), and protogynous pecans have a delayed progression from pollen tetrads to mature pollen as compared to protandrous pecans (Stuckey 1915). FIL1 homologs are expressed uniquely or predominantly in stamens (Nacken et al.1991, Fig. S19) and were found to be a downstream target of the B class MADS-box transcription factor DEFICIENS in Antirrhinum (Nacken et al. 1991) (the ortholog of Arabidopsis AP3).

We found strongly elevated nucleotide divergence between Carya G-locus haplotypes against the genome-wide background, suggesting that they could have been maintained as an ancient balanced polymorphism (Fig. 3D). To search for evidence of trans-species polymorphism of the Carya G-locus, we compared the North American pecan to two long-read genome assemblies from species in the East Asian Carya clade (C. sinensis and C. cathayensis, Zhang et al. 2023), spanning the deepest split within the genus (see Fig. 3E for species tree). Patterns of read depth of the pecan whole-genome resequencing reads against these two assemblies suggested that the C. cathayensis and C. sinensis assemblies represent the g and G haplotypes, respectively (Fig. S21). This was further supported by elevated nucleotide divergence between the assemblies in this region (Fig. S22) and shared nonsynonymous coding polymorphisms with pecan haplotypes (Fig. S18). We next constructed a maximum-likelihood consensus phylogeny from concatenated protein-coding sequence from the 20 G-locus genes, and found that it conflicts with the species tree, with C. cathayensis clustering with the pecan g haplotype and C. sinensis clustering with the pecan G haplotype (both 100% bootstrap support). Finally, we used whole-genome resequencing data from 16 individuals (15 from Huang et al. 2019, 1 from this study) representing 15 different Carya species to examine heterozygosity at the G-locus across the genus. We ascertained in pecan a set of 454 SNPs in coding sequence that were fixed between G-locus haplotypes. We found 8/16 individuals in this sample that are highly heterozygous at these SNPs (25–74%, the other half being 1–5%), consistent with these individuals being heterozygous for the G-locus and with dichogamy types being maintained at 50/50 proportions in species across the entire genus (Figs. S23, S24). We conclude from these multiple lines of evidence that the Carya G-locus haplotypes are at least as old as the divergence between Eastern North American and East Asian clades of Carya, a depth of ~25 Mya (Zhang et al. 2013; Mu et al. 2020; Zhou et al. 2021).

If variation at the Carya G-locus controlled dichogamy types in the ancestor of Juglans and Carya, we would expect that nucleotide divergence between the Carya G-locus haplotypes should match nucleotide divergence between pecan and the orthologous sequence in Juglans. Divergence between Carya G-locus haplotypes at four-fold degenerate sites across the core set of Carya G-locus genes that group by haplotype was significantly less than that between either Carya haplotype and J. regia (0.055 vs. 0.067, P < 0.001), implying that the Carya G-locus haplotypes diverged more recently than the Juglans-Carya split. Assuming a molecular clock and a divergence time of 58–72 Mya between Juglans and Carya (Zhang et al. 2013; Mu et al. 2020; Zhou et al. 2021), we estimate the age of the Carya G-locus haplotypes to be 48–59 Mya.

The G haplotype is rarely found in homozygotes due to strong disassortative mating under heterodichogamy, and it seems to experience little recombination (Fig. S17), so it may experience similar evolutionary forces to non-recombination portions of Y chromosomes (Bachtrog 2013). The pecan G haplotype (445 kb) is over twice as large as the g haplotype (200 kb), largely due to a difference in transposable element content within the region of reduced recombination (g: 40%, G: 65%, genome average: 53%, Fig. S25) . Part of the transposable element expansion in the G haplotype may be ancient, given parallel coverage patterns and assembly lengths for the East Asian G-locus haplotypes; the C. sinensis G assembly is ~350 kb, while the C. cathayensis g assembly is ~230 kb. This proliferation of transposable elements within G haplotypes might reflect reduced efficacy of selection on the G haplotype due to its lower effective population size and the enhanced effects of linked selection due to its low recombination rate (Charlesworth and Charlesworth 2000). Consistent with G haplotypes having a reduced effective population size and/or stronger linked selection, we observe a ~6 fold reduction in genetic diversity in coding regions for G haplotypes compared to g haplotypes (π = 0.0111 vs. 0.0018, P < 0.013).

Theory and data suggests that supergenes (e.g. sex chromosomes) may progressively assemble over time, perhaps through the accumulation of morph-antagonistic variation. While broad synteny of 20 predicted protein-coding genes across Carya G-locus assemblies is conserved as far back as the divergence with oaks (~90 Mya, Larson-Johnson 2016) (Fig. S26), we do note several predicted protein-coding genes that differ among Carya G-locus assemblies (Fig. 3F, Table S5). Notably, two of these appear to be derived and shared between North American and East Asian G haplotypes and so warrant further attention (Table S5, methods). While the majority of gene trees across the G-locus support the trans-species polymorphism for the four Carya assemblies, we also note that the three genes at the left border (including EMS1) and the gene at the right border instead support the species phylogeny for these four taxa (Fig. 3F). Furthermore, we do not see clear evidence for trans-species polymorphism within these genes in the East Asian clade (Figs. 3D, S24). These observations, and the lower divergence between pecan G-locus halotypes in the three genes at the left border, suggest the boundary of recombination suppression at the G-locus may have changed since the divergence of the North American and East Asian Carya, perhaps after the appearance of genetic variation in neighboring genes with antagonistic fitness effects between the two dichogamy morphs.

Genetic systems for heterodichogamy in other genera

Our estimate of the age of the Carya G-locus haplotypes suggests that we do not expect to find these haplotypes segregating in other known heterodichogamous genera within Juglandaceae - Cyclocarya, Platycarya, and likely Pterocarya - which are all more closely related to Juglans than to Carya. Nonetheless, we considered the possibility that a subset of the pecan G-locus variation could be ancestral across heterodichogamous genera, or that there has been convergent use of the same region. Therefore, we examined heterozygosity at the region syntenic with the Carya G-locus in a sample of 13 Pterocarya, 12 diploid Cyclocarya (including protandrous and protogynous individuals, Qu et al. 2023), and 3 Platycarya strobilaceae, but we found no evidence of increased polymorphism in this region comparable to the patterns seen in Carya (Fig. S27). As our analyses also indicate that heterodichogamy in these genera is not controlled by the Juglans G-locus (Fig. 2C, S8, S28), this suggests the intriguing possibility that additional genetic systems controlling heterodichogamy in other Juglandaceae genera remain undiscovered.

Discussion

The genetic mechanisms underlying heterodichogamy appear to be more diverse than previously appreciated. Within Juglandaceae, two distinct ancient structural variants underlie this mating polymorphism in different genera. The identification of these loci opens further opportunities to study the ecology and the molecular and cellular mechanisms of this mating system with potential agricultural benefits in these important crop species. Our data cannot rule out the possibility that these genetic systems originated independently through the convergent evolution of heterodichogamy. However, given the clade-wide presence of heterodichogamy across Juglandaceae, it seems plausible that a heterodichogamous mating system evolved once in the ancestor and that genetic control of dichogamy type has been subject to turnover. Similar dynamics have been discovered in sex determination systems as new data and experiments improve both the phylogenetic scale and resolution of sex-chromosome turnover (Myosho et al. 2012; Jeffries et al. 2018; Hu et al. 2023). As heterodichogamy unites concepts of inbreeding avoidance, sexual interference, and sex-ratio selection, these systems may offer an important complement for testing theories on the evolution of the control and turnover of sexual systems (Sargent et al. 2006; Van Doorn and Kirkpatrick 2007; Kozielska et al. 2010; Blaser et al. 2013; Saunders et al. 2018). In summary, the evolution of heterodichogamy within Juglandaceae showcases both dynamic evolution and remarkable stability.

Materials and Methods

Phenotyping

We phenotyped 81 individuals of a naturally-occuring population of J. hindsii from the UC Davis Putah Creek Riparian Reserve, along a ~2 mile creek-side path, in spring of 2022 and 2023. Dichogamy type was ascertained visually based on the relative developmental stages of male and female flowers. To validate our assessment of flowering phenotype we measured the length and width of 1–3 catkins of each tree on the same day and plotted the size distribution of catkins in the sample (Fig. 1A). We similarly obtained dichogamy phenotypes for individuals of J. ailantifolia, J. californica, J. cathayensis, J. cinerea, and J. major from trees at USDA Wolfskill Experimental Orchard in spring 2023. Phenotypes of newly sequenced C. illinoinensis from UC Davis orchards were also scored. Dichogamy phenotypes were available for 26 previously sequenced individuals of J. regia from UC Davis walnut breeding program records (Stevens et al. 2018). Flowering phenotypes for J. microcarpa and J. hindsii trees that were previously sequenced in Stevens et al. (2018) were obtained from the USDA Wolfskill Experimental Orchard database (Chuck Leslie, personal communication). Phenotypes of previously sequenced J. nigra individuals (Stevens et al. 2018) were obtained from Chatwin et al. (2023). Phenotypes of previously sequenced varieties of pecan (Xiao et al. 2021) were obtained from Bentley et al. (2019). Phenotypes of newly sequenced pecan varieties were scored visually in spring of 2023 or otherwise obtained from Bentley et al. (2019) and the USDA database (https://cgru.usda.gov/carya/pecans/).

We measured the length of dormant catkin buds in 30 J. regia individuals on July 20, 2023. Measurements were made blind with respect to phenotype with the exception of 3 varieties which were known a priori. We took an average measurement of 6–12 of the largest easily accessible catkins using hand calipers. We tested for a difference in length using a linear model with leafing date as a covariate (Fig. S9).

Genomic sequencing and data curation

We generated whole-genome resequencing (mean coverage ~35x) data for 46 J. hindsii; 2 individuals each from J. ailantifolia, J. californica, J. cathayensis, J. cinerea, J. major; 19 C. illinoinensis; 1 C. ovata; 13 Pterocarya stenoptera; 2 Pterocarya rhoifolia; 1 Pterocarya macroptera; and 2 Platycarya strobilaceae (Table S1). Samples of J. hindsii were a subset of trees phenotyped from the UC Davis Putah Creek Riparian Reserve, CA, plus two additional trees without dichogamy phenotypes from the same population. Other sequenced Juglans trees were from USDA Wolfskill Experimental Orchard. Samples of Pterocarya stenoptera were obtained from Wolfskill and UC Davis campus. Samples of Carya illinoinensis were obtained from UC Davis orchards and the original orchard of Linwood Nursery in Turlock, California. Leaf tissue was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and preserved at −80 degrees Celsius. DNA was extracted using the Qiagen DNeasy Plant Pro Kit.

We accessed published whole-gene resequencing data from 87 individuals of J. regia from Ding et al. (2022); Ji et al. (2021), 60 individuals of J. mandshurica from (Xu et al. 2021), and 26 J. regia, 11 J. hindsii, 12 J. microcarpa, and 13 J. nigra from Stevens et al. (2018). Published resequencing data for Cyclocarya and Platycarya were obtained from Qu et al. (2023) and Zhang et al. (2019), respectively. We used publicly available long-read genome assemblies of plants within Fagales generated by Zhu et al. (2019); Marrano et al. (2020); Fitz-Gibbon et al. (2023); Zhang et al. (2021); Lovell et al. (2021); Zhang et al. (2023); Ding et al. (2023); Ning et al. (2020); Li et al. (2022a); Zhang et al. (2020); Sork et al. (2022); Qu et al. (2023); Cao et al. (2023); Guzman-Torres et al. (2023).

We accessed mRNA transcriptome sequence data from floral tissues of J. mandshurica from Qin et al. (2021) and Li et al. (2022b). We accessed small RNA sequencing libraries from floral buds of a protogynous and protandrous individual of J. mandschurica from Li et al. (2023).

We accessed whole-genome resequence data for 34 varieties of C. illinoinensis from Xiao et al. (2021). We verified the variety identity for 12 of these samples by comparison of genetic relatedness at overlapping sets of SNPs to reduced representation sequence data from 83 varieties of cultivated pecan from Bentley et al. (2019). The remainder of these samples were not used in the analysis, as several were labelled as varieties that did not match their predicted identity using data from Bentley et al. (2019). We chose the data from Bentley et al. (2019) as the standard as dichogamy type was rigorously documented for the trees in this data set. Whole-genome resequencing for 15 Carya individuals of different species were obtained from Huang et al. (2019).

Sequence alignment, variant calling, and coverage analyses

We mapped short read sequencing libraries to available long-read reference genomes using bwa 0.7.17 (Li and Durbin 2009) with default parameters. To examine structural differences between G-locus haplotyes, we used BLAST (Altschul et al. 1990) to identify and align syntenic regions containing TPPD-1 orthologs. We used both minimap2 (Li 2018) and Anchorwave (Song et al. 2022) to align entire chromosomes and G-locus regions for variant calling and divergence calculations. In one analysis, we aligned all available genomes to the Walnut 2.0 (g haplotype) (Fig. S7). For divergence calculations, we aligned genomes containing alternate G-locus haplotypes within species for J. regia, J. californica, and J. mandschurica using Anchorwave. As Anchorwave uses a genome annotation in the alignment, we used liftoff (Shumate and Salzberg 2021) to port the Walnut 2.0 annotation onto assemblies lacking an annotation. Variant calling was done with bcftools 1.17 (Danecek et al. 2021). Variants were filtered in vcftools 0.1.16 (Danecek et al. 2011). Filters were set at minDP 10 and minGQ 30 for most analyses, but were adjusted on a per-analysis basis. We measured read depth in windows across G-loci in Juglans and Carya using samtools depth (Danecek et al. 2021). Read depth was normalized for each individual by the average read depth across a different chromosome which was chosen arbitrarily.

We used Salmon (Patro et al. 2017) to align RNA-seq data transcripts to a transcriptome of J. mandshurica and tximport (Soneson et al. 2015) to quantify normalized transcript abundances. We used STAR 2.7.6 (Dobin et al. 2013) to align transcripts to the reference genome to measure relative allelic depths at J. mandshurica G-locus SNP positions with fixed differences. SNPs were ascertained from whole-genome resequencing of 60 J. mandshurica, where we phased variants using Beagle 5.4 (Browning et al. 2021) with a dummy SNP at the location of the GJ1 indel. For small RNA sequence data, we first trimmed adapter sequences using skewer (Jiang et al. 2014) and filtered for reads 18–36 bp in length. Reads were aligned to an assembly of the protogynous assembly of J. mandshurica using bowtie 1.3.0 (Langmead et al. 2009). We used two mapping approaches, one which reported only uniquely-mapping reads with one mismatch (−v 1 −m 1), and one which reported reads that map to at most 10 locations in the genome with a single mismatch (−v 1 −m 10).

GWAS and linkage disequilibrium

We performed GWAS for dichogamy type separately in 44 individuals of J. hindsii, 26 J. regia individuals, and 30 Carya illinoinensis individuals. GWAS was done in GEMMA 0.98.3 (Zhou and Stephens 2012), which controls for genome-wide relatedness among samples. We calculated genotypic LD as the r2 value between genotypes at pairs of loci using vcftools, filtering sites for a minimum distance of 100 bp or 5 kb.

Phylogenetic analyses and synteny

To construct a phylogeny of GJ1 repeats and their homologs, we extracted the genomic coordinates of individual repeat subunits from pairwise BLAST alignments. We aligned subunits a, b, and c separately using muscle (Edgar 2004) and then concatenated alignments. We constructed a maximum-likelihood phylogeny using IQ-Tree (Nguyen et al. 2015) and obtained node support values using the program’s ultrafast bootstrap approximation algorithm. We constructed a species phylogeny for Carya genome assemblies and J. regia, from concatenated alignments of 12,101 single copy orthologs identified in OrthoFinder (Emms and Kelly 2019). The phylogeny of the Carya G-locus was inferred similarly using just the 20 genes within the G-locus, as well as for each gene individually. We inferred and visualized synteny across the Carya G-locus using MCscan (Tang et al. 2008) which leverages collinearity of orthologs.

While G-locus haplotypes show strong conservation of synteny, we note a small number of predicted genes that are not shared between haplotypes (see Fig. 3F). None of these was annotated independently in two assemblies. However, we investigated whether homologous sequence in other assemblies may have been missed by the annotation pipeline. We therefore used BLAST to search for sequence homologous to these uniquely annotated genes in other Carya G-locus assemblies (Table S5). For two genes that were uniquely annotated in the C. sinensis assembly, we found significant BLAST hits within syntenic regions of the ‘Lakota’ primary assembly (Fig. 3F), but not within G-locus regions of the other assemblies (although we find hits elsewhere in the assemblies). This result suggests that these are ancient duplications, perhaps with conserved function. However, further validation of these predicted genes with gene expression and additional de novo assemblies is needed to fully address the role of gene duplications in the assembly of G-locus haplotypes.

Haplotype nucleotide divergence and dating

We calculated nucleotide divergence across the region encompassing the Juglans G-locus in 500 bp windows from genome alignments using custom R scripts. We find that the divergence between G-locus haplotypes is comparable to the divergence between Juglans and Carya, indicating deep divergence of Juglans G-locus haplotypes, potentially occurring close in time to the split between Juglans and Carya (~70 Myr). We used a molecular clock approach with substitution rates estimated from nonsynonymous coding regions in Juglans (Ding et al. 2023; Zhu et al. 2019). Here, we used alignments between G-locus haplotypes within three species (J. regia, J. californica, J. mandschurica), and took the average of the maximum divergence value within any 500 bp window on either side of the G-locus indels within 4 kb. We then adjusted this average value of for multiple hits using the Jukes and Cantor (1969) distance correction. We then calculated the divergence time as . Using two reported estimates of the substitution rate ( per bp per year (Ding et al. 2023), and per bp per year (Zhu et al. 2019)), we obtain estimates of 68.8 Mya and 41.3 Mya, respectively. We note there is considerable uncertainty about the substitution rate for this region. Furthermore, evidence of rare recombination between haplotypes within the TPPD-1 sequence over deep timescales (Fig. S5) suggests that the genealogies of these linked regions in contemporary G-locus haplotypes may differ from the genealogy of the causal variants. Nonetheless, these estimates accord well with the fact that the divergence between Juglans G-locus haplotypes is comparable in magnitude to the divergence between Juglans and Carya in this region (Fig. S6). We also note that it is consistent with trans-specific SNPs across the deepest split within Juglans, the inferred GJ1 phylogeny, and read depth analyses in supporting haplotype divergence in the common ancestor of Juglans.

To calculate divergence between pecan G-locus haplotypes, we aligned coding regions from the ‘Lakota’ and ‘Pawnee’ primary assemblies and calculated using pixy. pixy was also used to calculate individual-level heterozygosity in other Carya species at pecan G-locus SNPs and SNPs that differentiated the two East Asian Carya G-locus haplotypes, and to calculate heterozygosity for Pterocarya and Cyclocarya individuals across regions syntenic with Juglans and Carya G-loci. We used the R package ape (Paradis and Schliep 2019) to calculate divergence at fourfold degenerate sites within aligned coding sequences from the Carya G-locus. To estimate a divergence time, we used the ratio of the between Carya haplotypes and from the average of both Carya haplotypes to J. regia, adjusting divergence values for multiple hits using Jukes and Cantor (1969).

Polymorphism within haplotypes and tests of selection

We examined polymorphism within G-locus haplotypes in a sample of 113 Juglans regia, containing individuals sampled from across the species’ range and without reference to dichogamy type (Ding et al. 2022; Ji et al. 2021; Stevens et al. 2018). In this sample, we observed 60 gg, 50 Gg, and 2 GG individuals for the G-locus structural variant. Thus, proportions of protandrous and protogynous individuals are close to 50/50 in this broad sampling (P=0.46 under null hypothesis of equal proportions). The proportion of GG genotypes is lower than expected under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P=0.036), consistent with disassortative mating at the G-locus or selection against GG genotypes.

In Juglans, to test for an excess of nonsynonymous fixed differences between G-locus haplotypes relative to polymorphism (or conversely, an excess of nonsynonymous polymorphism), we performed a McDonald-Kreitman test for TPPD-1 coding sequence (McDonald and Kreitman 1991) in sample of 113 J. regia and in a sample of 46 J. hindsii. To obtain data partitioned by haplotype, variants were first filtered for a minor allele count of 2 and then phased haplotypes using Beagle 5.4 (Browning et al. 2021). In order to assign haplotype identities to phased haplotypes, we added a line to the VCF with a dummy SNP representing an individual’s genotype for the G-locus structural variant. In J. regia, we discarded one heterozygote which showed an erroneous phase switch between its two haplotypes; aside from this we saw no other evidence of phasing errors TPPD-1 in heterozygotes in either species sample. Furthermore, phasing resulted in two distinct clusters of haplotypes with non-overlapping distributions of the number of variants compared to the reference. We used a custom R script to calculate nonsynonymous and synonymous polymorphism and divergence in the sample, and performed the MK test using Fisher’s exact test. We ignored singletons within haplotype groups in determining fixed differences between haplotype groups.

In J. regia, we found 9 fixed nonsynonymous variants and 6 fixed synonymous variants in TPPD-1 coding sequence. Using a long read alignment between J. regia and an outgroup (pecan) to polarize SNPs, we identified 5 nonsynonymous and 3 synonymous fixed differences derived in the J. regia G lineage, 4 nonsynonymous and 2 nonsynonymous derived in the g lineage, and one synonymous site with an ambiguous ancestral state. We found limited polymorphism within haplotype groups in TPPD-1 coding sequence: 2 nonysnonymous and 1 synonymous in g haplotypes, and 4 nonysnonymous and 1 synonymous in G haplotypes. In J. hindsii, we observed 8 nonsynonymous and 5 synonymous fixed differences between haplotypes. We observed a near complete lack of polymorphism within TPPD-1 coding sequence in this population, with only one polymorphism segregating in multiple g haplotype copies, and zero polymorphisms segregating in multiple G haplotype copies.

In pecan, we similarly phased SNPs in coding regions across the Carya G-locus along with with a dummy SNP placed in the center of the G-locus to represent the structural variant. We saw no evidence of phasing errors by checking for haplotype switching in heterozygotes. Using J. regia as an outgroup to polarize SNPs, we identified 235 G-locus coding SNPs that fixed in G lineage, 118 of these nonsynonymous changes. We identified 215 that fixed in g lineage, 103 of these nonsynonymous changes. Fifteen remaining fixed differences had an ambiguous ancestral state where J. regia showed a different allele than either pecan haplotype. We tested for a difference in values between the G and g lineages using a Chi Squared test, which did not yield a statistically significant result.

We used pixy to estimate pairwise nucleotide divergence () between the sets of homozygous individuals within coding sequence at the Carya G-locus (gg: 13, GG: 2). The two GG indivduals are not known to be close relatives from pecan pedigree records, and they do not show an unusually high kinship coefficient compared to other pairs of individuals in our analysis set. To test for significance, we estimated for all combinations of two gg individuals, and checked whether in any case the estimated value was equal to or lower than the value observed for GG individuals. We separately estimated Watterson’s Theta from phased haplotypes and found an 8.7-fold reduction for G haplotypes compared to g haplotypes ().

PacBio IsoSeq

Tissues were collected from various locations at the University of California in Davis and the USDA’s National Clonal Germplasm Repository in Winters, CA. Collected tissue was wrapped in foil and immediately immersed in liquid nitrogen in the field to preserve RNA quality. Frozen tissues were subsequently pulverized in liquid nitrogen in a mortar and pestle for extraction.

The extraction buffer used was 4M guanidine isothiocyanate, 0.2 M sodium acetate pH 5.0, 2mM EDTA, 2.5% (w/v) PVP-40. To this we added 400 uL Lysis buffer to 100 mg tissue and homogenize with pestle for 30 seconds, then 600 uL Lysis buffer (1 mL total)was added and vortexed for 20 seconds. From this, 500 uL of the homogenate was processed using the RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s protocol (centrifugations steps were performed at 12,000 rpm for 30 seconds). RNA was eluted with 50 uL nuclease-free water at Step 9 in manufacturer’s protocol. This was followed by DNase digestions with Turbo DNA-free kit (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s protocols. Finally, RNA samples were cleaned up using HighPrep RNA Elite beads (MagBio Genomics) according to the manufacturer’s 96 well format protocol for 10 uL reaction volume. Final elution was performed with 20 uL of nuclease-free water that was heated at 60C for ~10 minutes before adding to sample.

For quality control and quantitation, samples were subsequently checked for purity on Nanodrop, quantified on Qubit, and checked on Bioanalyzer.

SMRTbell libraries were constructed and sequenced at the University of California Davis Genome center. Sequencing was performed on the Pacbio Sequel II. Demultiplexing and post processing of sequence data to create high quality full length non-chimera consensus transcripts (FLNC) was performed using the PacBio bioinformatics pipeline (ccs v4.2.0, lima v1.11.0, isoseq v3).

To determine the presence of a transcribed sequence in an IsoSeq library of (full-length non-chimeric) FLNC reads, command line blastn 2.12.0+ was used with default parameters. The sequence for the TPPD-1 was queried against each individual library separately. Matches with a percent identity greater than or equal to 90 were considered positives.

Transposable Element Annotation

We performed de-novo whole genome annotation of transposable elements (TEs) for long-read assemblies of both G-locus haplotypes in J. regia, J. californica, and J. mandshurica using EDTA (Ou et al. 2019), and compared coordinates of annotated TEs to the coordinates of the derived gJ3 insertion. EDTA predicted the presence of a CACTA-like DNA transposon at the coordinates of gJ3. We separately identified the presence of terminal inverted repeats near the gJ3 insertion endpoints and evidence of target site duplication.

We also used EDTA to annotate assemblies of ‘Pawnee’ and ‘Lakota’ pecan as well as assemblies of Carya sinensis and C. cathayensis. We computed the proportion of sequence covered by predicted TEs for three categories - (1) within the G-locus (defined by endpoints of genes falling inside the pecan GWAS peak, (2) in 300kb of sequence surrounding the G-locus (150kb on either side), and (3) across the whole genome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to UC Davis Putah Creek Riparian Reserve, Gene Cripe of Linwood Nursery, CA, USDA Wolfskill Experimental Orchard, Sonoma Botanical Garden, and UC Botanical Garden at Berkeley for access to leaf tissue from natural and cultivated collections of Juglandaceae. We thank Chuck Leslie for providing phenotype records for trees from the USDA germplasm database. We thank Jeff Ross-Ibarra, Quentin Cronk, the Dandekar lab at UC Davis, and the Coop lab for helpful discussions. Funding was provided by the United States Department of Agriculture (NIFA SCRI-Award no. 2012-51181-20027 awarded to PJB, CHL), the National Institutes of Health (NIH R35 GM136290 awarded to GC), and the National Science Foundation (NSF DISES 2307175 to GC, and NSF 1650042 awarded to JSG).

References

- Akagi T, Henry IM, Tao R, Comai L. 2014. A Y-chromosome–encoded small RNA acts as a sex determinant in persimmons. Science. 346:646–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology. 215:403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachtrog D. 2013. Y-chromosome evolution: Emerging insights into processes of Y-chromosome degeneration. Nature Reviews Genetics. 14:113–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai WN, Zeng YF, Zhang DY. 2007. Mating patterns and pollen dispersal in a heterodichogamous tree, Juglans mandshurica (Juglandaceae). New Phytologist. 176:699–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett SC. 2010. Darwin’s legacy: the forms, function and sexual diversity of flowers. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 365:351–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley N, Grauke L, Klein P. 2019. Genotyping by sequencing (GBS) and SNP marker analysis of diverse accessions of pecan (Carya illinoinensis). Tree Genetics & Genomes. 15:1–17.30546292 [Google Scholar]

- Bernard A, Marrano A, Donkpegan A, Brown PJ, Leslie CA, Neale DB, Lheureux F, Dirlewanger E. 2020. Association and linkage mapping to unravel genetic architecture of phenological traits and lateral bearing in Persian walnut (Juglans regia L.). BMC genomics. 21:1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser O, Grossen C, Neuenschwander S, Perrin N. 2013. Sex-chromosome turnovers induced by deleterious mutation load. Evolution. 67:635–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning BL, Tian X, Zhou Y, Browning SR. 2021. Fast two-stage phasing of large-scale sequence data. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 108:1880–1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Almeida-Silva F, Zhang WP, Ding YM, Bai D, Bai WN, Zhang BW, Van de Peer Y, Zhang DY. 2023. Genomic insights into adaptation to karst limestone and incipient speciation in East Asian Platycarya spp. (Juglandaceae). Molecular Biology and Evolution. 40:msad121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S, Britton M, Martínez-García P, Dandekar AM. 2016. Deep RNA-Seq profile reveals biodiversity, plant–microbe interactions and a large family of NBS-LRR resistance genes in walnut (Juglans regia) tissues. AMB Express. 6:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B, Charlesworth D. 2000. The degeneration of Y chromosomes. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 355:1563–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth D. 2016. The status of supergenes in the 21st century: recombination suppression in Batesian mimicry and sex chromosomes and other complex adaptations. Evolutionary Applications. 9:74–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth D, Charlesworth B. 1979. The evolutionary genetics of sexual systems in flowering plants. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences. 205:513–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatwin W, Shirley D, Lopez J, Sarro J, Carlson J, Devault A, Pfrender M, Revord R, Coggeshall M, Romero-Severson J. 2023. Female flowers first: QTL mapping in eastern black walnut (Juglans nigra L.) identifies a dominant locus for heterodichogamy syntenic with that in Persian walnut (J. regia L.). Tree Genetics & Genomes. 19:4. [Google Scholar]

- Danecek P, Auton A, Abecasis G, Albers CA, Banks E, DePristo MA, Handsaker RE, Lunter G, Marth GT, Sherry ST et al. . 2011. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 27:2156–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danecek P, Bonfield JK, Liddle J, Marshall J, Ohan V, Pollard MO, Whitwham A, Keane T, McCarthy SA, Davies RM et al. . 2021. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience. 10:giab008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang M, Zhang T, Hu Y, Zhou H, Woeste KE, Zhao P. 2016. De novo assembly and characterization of bud, leaf and flowers transcriptome from Juglans regia L. for the identification and characterization of new EST-SSRs. Forests. 7:247. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. 1876. The Effects of Cross and Self Fertilisation in the Vegetable Kingdom. John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. 1877. The Different Forms of Flowers on Plants of the Same Species. John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Delpino F. 1874. Ulteriori osservazioni e considerazioni sulla dicogamia nel regno vegetale. Appendice. Dimorfismo nel noce (Juglans regia) e pleiontismo nelle piante. Atti della Societa Italiana Scientia Naturale. 17:402–407. [Google Scholar]

- Ding YM, Cao Y, Zhang WP, Chen J, Liu J, Li P, Renner SS, Zhang DY, Bai WN. 2022. Population-genomic analyses reveal bottlenecks and asymmetric introgression from Persian into iron walnut during domestication. Genome Biology. 23:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding YM, Pang XX, Cao Y, Zhang WP, Renner SS, Zhang DY, Bai WN. 2023. Genome structure-based Juglandaceae phylogenies contradict alignment-based phylogenies and substitution rates vary with DNA repair genes. Nature Communications. 14:617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. 2013. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 29:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research. 32:1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emms DM, Kelly S. 2019. Orthofinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biology. 20:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endress PK. 2020. Structural and temporal modes of heterodichogamy and similar patterns across angiosperms. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 193:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fitz-Gibbon S, Mead A, O’Donnell S, Li ZZ, Escalona M, Beraut E, Sacco S, Marimuthu MP, Nguyen O, Sork VL. 2023. Reference genome of California walnut, Juglans californica, and resemblance with other genomes in the order Fagales. Journal of Heredity. esad036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friis E. 1983. Upper Cretaceous (Senonian) floral structures of juglandalean affinity containing Normapolles pollen. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 39:161–188. [Google Scholar]

- Fröhlich KS, Vogel J. 2009. Activation of gene expression by small RNA. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 12:674–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuhara T, Tokumaru Si. 2014. Inflorescence dimorphism, heterodichogamy and thrips pollination in Platycarya strobilacea (Juglandaceae). Annals of Botany. 113:467–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson SK. 1982. Heterodichogamy in walnuts: inheritance and stable ratios. Evolution. pp. 892–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Valencia J, Hughes PW, Berdan EL, Slotte T. 2021. The genomic architecture and evolutionary fates of supergenes. Genome Biology and Evolution. 13:evab057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman-Torres CR, Trybulec E, LeVasseur H, Akella H, Amee M, Strickland E, Pauloski N, Williams M, Romero-Severson J, Hoban S et al. . 2023. Conserving a threatened North American walnut: a chromosome-scale reference genome for butternut (Juglans cinerea). bioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2023.05.12.539246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu N, Sanderson BJ, Guo M, Feng G, Gambhir D, Hale H, Wang D, Hyden B, Liu J, Smart LB et al. . 2023. Evolution of a ZW sex chromosome system in willows. Nature Communications. 14:7144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Xiao L, Zhang Z, Zhang R, Wang Z, Huang C, Huang R, Luan Y, Fan T, Wang J et al. . 2019. The genomes of pecan and Chinese hickory provide insights into Carya evolution and nut nutrition. GigaScience. 8:giz036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries DL, Lavanchy G, Sermier R, Sredl MJ, Miura I, Borzée A, Barrow LN, Canestrelli D, Crochet PA, Dufresnes C et al. . 2018. A rapid rate of sex-chromosome turnover and non-random transitions in true frogs. Nature Communications. 9:4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji F, Ma Q, Zhang W, Liu J, Feng Y, Zhao P, Song X, Chen J, Zhang J, Wei X et al. . 2021. A genome variation map provides insights into the genetics of walnut adaptation and agronomic traits. Genome Biology. 22:1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Lei R, Ding SW, Zhu S. 2014. Skewer: a fast and accurate adapter trimmer for next-generation sequencing paired-end reads. BMC Bioinformatics. 15:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jukes TH, Cantor CR. 1969. Evolution of protein molecules. Mammalian Protein Metabolism. 3:21–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kozielska M, Weissing F, Beukeboom L, Pen I. 2010. Segregation distortion and the evolution of sex-determining mechanisms. Heredity. 104:100–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. 2009. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biology. 10:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson-Johnson K. 2016. Phylogenetic investigation of the complex evolutionary history of dispersal mode and diversification rates across living and fossil Fagales. New Phytologist. 209:418–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. 2018. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 34:3094–3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 25:1754–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhang M, Wu J, Qin B, Liu C, Zhang L. 2023. Identification and analysis of key miRNA for sex differentiation in hermaphroditic Juglans mandshurica Maxim. Preprint (Version 1, 26 May 2023). Research Square. doi: 10.1101/2023.05.12.539246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li LC, Okino ST, Zhao H, Pookot D, Place RF, Urakami S, Enokida H, Dahiya R. 2006. Small dsRNAs induce transcriptional activation in human cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103:17337–17342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Cai K, Zhang Q, Pei X, Chen S, Jiang L, Han Z, Zhao M, Li Y, Zhang X et al. . 2022a. The Manchurian walnut genome: insights into juglone and lipid biosynthesis. GigaScience. 11:giac057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Han R, Cai K, Guo R, Pei X, Zhao X. 2022b. Characterization of phytohormones and transcriptomic profiling of the female and male inflorescence development in Manchurian walnut (Juglans mandshurica Maxim.). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23:5433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell JT, Bentley NB, Bhattarai G, Jenkins JW, Sreedasyam A, Alarcon Y, Bock C, Boston LB, Carlson J, Cervantes K et al. . 2021. Four chromosome scale genomes and a pan-genome annotation to accelerate pecan tree breeding. Nature Communications. 12:4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Chen Ln, Hao Jb, Zhang Y, Huang Jc. 2020. Comparative transcription profiles reveal that carbohydrates and hormone signalling pathways mediate flower induction in J. sigillata after girdling. Industrial Crops and Products. 153:112556. [Google Scholar]

- Luza JG, Polito VS. 1988. Microsporogenesis and anther differentiation in Juglans regia L.: A developmental basis for heterodichogamy in walnut. Botanical Gazette. 149:30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Manchester SR. 1987. The fossil history of the Juglandaceae. Monographs in Systematic Botany from the Missouri Botanical Garden. 21:1–137. [Google Scholar]

- Manchester SR. 1989. Early history of the Juglandaceae. Plant Systematics and Evolution. pp. 231–250. [Google Scholar]

- Mao X, Fu XX, Huang P, Chen XL, Qu YQ. 2019. Heterodichogamy, pollen viability, and seed set in a population of polyploidy Cyclocarya paliurus (Batal) Iljinskaja (Juglandaceae). Forests. 10:347. [Google Scholar]

- Marrano A, Britton M, Zaini PA, Zimin AV, Workman RE, Puiu D, Bianco L, Pierro EAD, Allen BJ, Chakraborty S et al. . 2020. High-quality chromosome-scale assembly of the walnut (Juglans regia L.) reference genome. GigaScience. 9:giaa050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JH, Kreitman M. 1991. Adaptive protein evolution at the Adh locus in Drosophila. Nature. 351:652–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu XY, Tong L, Sun M, Zhu YX, Wen J, Lin QW, Liu B. 2020. Phylogeny and divergence time estimation of the walnut family (Juglandaceae) based on nuclear RAD-Seq and chloroplast genome data. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 147:106802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller NA, Kersten B, Leite Montalvão AP, Mähler N, Bernhardsson C, Bräutigam K, Carracedo Lorenzo Z, Hoenicka H, Kumar V, Mader M et al. . 2020. A single gene underlies the dynamic evolution of poplar sex determination. Nature Plants. 6:630–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myosho T, Otake H, Masuyama H, Matsuda M, Kuroki Y, Fujiyama A, Naruse K, Hamaguchi S, Sakaizumi M. 2012. Tracing the emergence of a novel sex-determining gene in medaka, Oryzias luzonensis. Genetics. 191:163–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacken WK, Huijser P, Beltran JP, Saedler H, Sommer H. 1991. Molecular characterization of two stamen-specific genes, tap1 and fil1, that are expressed in the wild type, but not in the deficiens mutant of Antirrhinum majus. Molecular and General Genetics MGG. 229:129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, Von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 32:268–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning DL, Wu T, Xiao LJ, Ma T, Fang WL, Dong RQ, Cao FL. 2020. Chromosomal-level assembly of Juglans sigillata genome using Nanopore, BioNano, and Hi-C analysis. GigaScience. 9:giaa006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou S, Su W, Liao Y, Chougule K, Agda JR, Hellinga AJ, Lugo CSB, Elliott TA, Ware D, Peterson T et al. . 2019. Benchmarking transposable element annotation methods for creation of a streamlined, comprehensive pipeline. Genome Biology. 20:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis E, Schliep K. 2019. ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics. 35:526–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patro R, Duggal G, Love MI, Irizarry RA, Kingsford C. 2017. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nature Methods. 14:417–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polito V, Pinney K. 1997. The relationship between phenology of pistillate flower organogenesis and mode of heterodichogamy in Juglans regia L. (Juglandaceae). Sexual Plant Reproduction. 10:36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pringle C. 1879. Dimorpho-dichogamy in Juglans cinerea, L. Botanical Gazette. 4:237–237. [Google Scholar]

- Qin B, Lu X, Sun X, Cui J, Deng J, Zhang L. 2021. Transcriptome-based analysis of the hormone regulation mechanism of gender differentiation in Juglans mandshurica Maxim. PeerJ. 9:e12328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Shang X, Fang S, Zhang X, Fu X. 2023. Genome assembly of two diploid and one auto-tetraploid Cyclocarya paliurus genomes. Scientific Data. 10:507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner SS. 2001. How common is heterodichogamy? Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 16:595–597. [Google Scholar]

- Rhein HS, Sreedasyam A, Cooke P, Velasco-Cruz C, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, Jenkins J, Kumar S, Song M, Heerema RJ et al. . 2023. Comparative transcriptome analyses reveal insights into catkin bloom patterns in pecan protogynous and protandrous cultivars. PloS One. 18:e0281805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent RD, Mandegar MA, Otto SP. 2006. A model of the evolution of dichogamy incorporating sex-ratio selection, anther-stigma interference, and inbreeding depression. Evolution. 60:934–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh-Nagasawa N, Nagasawa N, Malcomber S, Sakai H, Jackson D. 2006. A trehalose metabolic enzyme controls inflorescence architecture in maize. Nature. 441:227–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders PA, Neuenschwander S, Perrin N. 2018. Sex chromosome turnovers and genetic drift: a simulation study. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 31:1413–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluepmann H, Pellny T, van Dijken A, Smeekens S, Paul M. 2003. Trehalose 6-phosphate is indispensable for carbohydrate utilization and growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100:6849–6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya K, Fukushima S, Takatsuji H. 2009. RNA-directed DNA methylation induces transcriptional activation in plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106:1660–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumate A, Salzberg SL. 2021. Liftoff: accurate mapping of gene annotations. Bioinformatics. 37:1639–1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims HJ, Herendeen PS, Lupia R, Christopher RA, Crane PR. 1999. Fossil flowers with Normapolles pollen from the Upper Cretaceous of southeastern North America. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 106:131–151. [Google Scholar]

- Soneson C, Love MI, Robinson MD. 2015. Differential analyses for RNA-seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Research. 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B, Marco-Sola S, Moreto M, Johnson L, Buckler ES, Stitzer MC. 2022. AnchorWave: Sensitive alignment of genomes with high sequence diversity, extensive structural polymorphism, and whole-genome duplication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119:e2113075119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sork VL, Cokus SJ, Fitz-Gibbon ST, Zimin AV, Puiu D, Garcia JA, Gugger PF, Henriquez CL, Zhen Y, Lohmueller KE et al. . 2022. High-quality genome and methylomes illustrate features underlying evolutionary success of oaks. Nature Communications. 13:2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens KA, Woeste K, Chakraborty S, Crepeau MW, Leslie CA, Martínez-García PJ, Puiu D, Romero-Severson J, Coggeshall M, Dandekar AM et al. . 2018. Genomic variation among and within six Juglans species. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics. 8:2153–2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey HP. 1915. The two groups of varieties of the Hicora pecan and their relation to self-sterility. Georgia Experiment Station. Bulletin No. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Wang X, Bowers JE, Ming R, Alam M, Paterson AH. 2008. Unraveling ancient hexaploidy through multiply-aligned angiosperm gene maps. Genome Research. 18:1944–1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson T, Romberg L. 1985. Inheritance of heterodichogamy in pecan. Journal of Heredity. 76:456–458. [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorn G, Kirkpatrick M. 2007. Turnover of sex chromosomes induced by sexual conflict. Nature. 449:909–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl V, Ponnu J, Schlereth A, Arrivault S, Langenecker T, Franke A, Feil R, Lunn JE, Stitt M, Schmid M. 2013. Regulation of flowering by Trehalose-6-Phosphate signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 339:704–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Yu M, Zhang Y, Hu J, Zhang R, Wang J, Guo H, Zhang H, Guo X, Deng T et al. . 2021. Chromosome-scale assembly reveals asymmetric paleo-subgenome evolution and targets for the acceleration of fungal resistance breeding in the nut crop, pecan. Plant Communications. 2:100247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu LL, Yu RM, Lin XR, Zhang BW, Li N, Lin K, Zhang DY, Bai WN. 2021. Different rates of pollen and seed gene flow cause branch-length and geographic cytonuclear discordance within Asian butternuts. New Phytologist. 232:388–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang BW, Xu LL, Li N, Yan PC, Jiang XH, Woeste KE, Lin K, Renner SS, Zhang DY, Bai WN. 2019. Phylogenomics reveals an ancient hybrid origin of the Persian walnut. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 36:2451–2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zhang W, Ji F, Qiu J, Song X, Bu D, Pan G, Ma Q, Chen J, Huang R et al. . 2020. A high-quality walnut genome assembly reveals extensive gene expression divergences after whole-genome duplication. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 18:1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JB, Li RQ, Xiang XG, Manchester SR, Lin L, Wang W, Wen J, Chen ZD. 2013. Integrated fossil and molecular data reveal the biogeographic diversification of the eastern Asian-eastern North American disjunct hickory genus (Carya Nutt.). PLoS one. 8:e70449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang WP, Cao L, Lin XR, Ding YM, Liang Y, Zhang DY, Pang EL, Renner SS, Bai WN. 2021. Dead-end hybridization in walnut trees revealed by large-scale genomic sequence data. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 39:msab308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang WP, Ding YM, Cao Y, Li P, Yang Y, Pang XX, Bai WN, Zhang DY. 2023. Uncovering ghost introgression through genomic analysis of a distinct East Asian hickory species. bioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2023.06.26.546421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao DZ, Wang GF, Speal B, Ma H. 2002. The EXCESS MICROSPOROCYTES1 gene encodes a putative leucine-rich repeat receptor protein kinase that controls somatic and reproductive cell fates in the Arabidopsis anther. Genes & Development. 16:2021–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Hu Y, Ebrahimi A, Liu P, Woeste K, Zhao P, Zhang S. 2021. Whole genome based insights into the phylogeny and evolution of the Juglandaceae. BMC Ecology and Evolution. 21:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Stephens M. 2012. Genome-wide efficient mixed-model analysis for association studies. Nature Genetics. 44:821–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T, Wang L, You FM, Rodriguez JC, Deal KR, Chen L, Li J, Chakraborty S, Balan B, Jiang CZ et al. . 2019. Sequencing a Juglans regia × J. microcarpa hybrid yields high-quality genome assemblies of parental species. Horticulture Research. 6:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.