Abstract

Introduction

Two cases of late presentation (>5 years) of bilateral pseudophakic macula edema related to oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors are described. These cases are the first of their type in the published literature. A review of ocular inflammatory complications of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the current literature is explored.

Case Presentation

Case 1 is an 83-year-old female who has been stable on ibrutinib (Imbruvica®) for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. She presented with bilateral blurred vision from severe cystoid macula edema, 7 years following routine cataract surgery. She was treated with intravitreal steroids with complete resolution without relapse. Case 2 is a 76-year-old female who was on therapy for polycythemia vera with ruxolitinib (Jakafi®). She presented with bilateral blurred vision from mild cystoid macula edema, 6 years following routine cataract surgery. She responded well to topical steroids without relapse. In both cases, oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor agents were presumed to be the underlying cause and were ceased. Over the last 5 years, there have been increasing reports in the literature of the inflammatory effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors on the retina, uvea, and optic nerve.

Conclusion

Late presentation of pseudophakic macula edema following routine cataract surgery is rare. Such presentations should prompt investigation of chronic use of systemic medications, especially oral kinase inhibitors. Patients who must remain on these agents require ongoing ophthalmologic assessment in view of their long-term inflammatory side effects.

Keywords: Pseudophakic macula edema, Kinase inhibitors, Ocular toxicity

Introduction

The incidence of pseudophakic macula edema in the literature is reported in the range of 1.46–2.5% [1]. In the majority of cases, this presents in the first 3 months following routine cataract surgery. Late presentations, after 1 year, are atypical. In patients with delayed presentations, toxicity from systemic medications should be considered. One such group of medications is small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors which are oral chemotherapeutic agents targeted for use in acute and chronic phase blood-borne cancers, other cancers, and autoimmune disease. With recent FDA approval, the use of these agents has increased together with their reported adverse ocular toxicities [2]. Table 1 summarizes 10 published case reports of cystoid macule edema which have been reported in patients on long-term oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor agents. We describe 2 cases of delayed presentations of bilateral cystoid macular edema in pseudophakic patients following chronic use of two different tyrosine kinase drugs.

Table 1.

Summary of case reports/series of oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors causing macula edema (Literature review: PubMed, Embase) [2, 3]

| Publication | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor agent | Indication | Ocular toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Masood et al. [4] (2005) | Imatinib (Gleevec) | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) | Cystoid macula edema |

| Georgalas et al. [5] (2007) | Imatinib (Gleevec) | Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) | Cystoid macula edema |

| McClelland et al. [3] (2010) | Imatinib (Gleevec) | Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) | Periorbital edema |

| Kusumi et al. [6] (2004) | Imatinib (Gleevec) | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) | Cystoid macula edema |

| Georgalas, [7] (2007) | Imatinib (Gleevec) | Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) | Cystoid macula edema |

| Roth et al. [8] (2009) | Imatinib (Gleevec) | Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) | Macula ischemia |

| Dogan et al. [9] (2009) | Imatinib (Gleevec) | Solid tumor (gastrointestinal stromal) | Cystoid macula edema, conjunctival hemorrhage, optic neuritis |

| Bajel et al. [10] (2008) | Imatinib (Gleevec) | Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) | Cystoid macula edema |

| Saenz-de-Viteri et al. [11] (2019) | Ibrutinib (Imbruvica) | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) | Cystoid macula edema |

| Mirgh et al. [12] (2020) | Ibrutinib (Imbruvica) | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) | Cystoid macula edema |

Case Report

Case 1

An 83-year-old female diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) 9 years ago and commenced on 400 mg ibrutinib (Imbruvica®) and remained stable on this dose. She underwent uneventful cataract surgery in both eyes 7 years ago and retained glasses for reading. She recently presented to the ophthalmologist with a 6-month history of increasing reading difficulty. On presentation, her best corrected visual acuity (Snellen BCVA) was 6/12 in the right eye and 6/9 in the left eye. Her intraocular pressures (IOPs) were 12 mm Hg in each eye. The anterior segment of each eye showed clear, centrally placed posterior chamber intraocular lenses with no evidence of posterior capsular opacification. An optical coherence tomogram (OCT) revealed moderate to severe bilateral macula edema as shown in Figure 1. OCT angiography revealed a classic petaloid appearance of pseudophakic macula edema as shown in Figure 2. She was otherwise well; she was not diabetic; and her only other medications were oral vitamin D supplements. Ibrutinib (Imbruvica®) was presumed to be the cause of her cystoid macula edema.

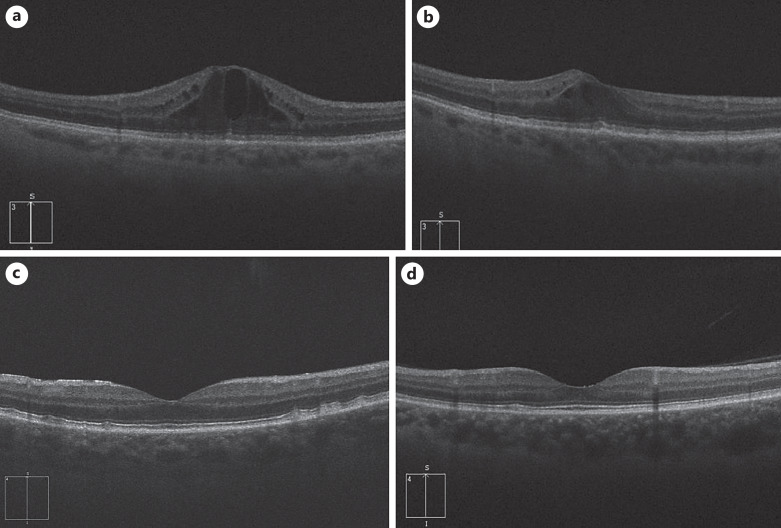

Fig. 1.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging of right and left eyes, respectively, of case 1. a Right eye at presentation with macula edema, central macular thickness (CMT) = 650 μm. b Left eye at presentation with macula edema, CMT = 500 μm. c Right eye posttreatment with resolution of macula edema, CMT = 277 μm. d Left eye posttreatment with resolution of macula edema, CMT = 248 μm.

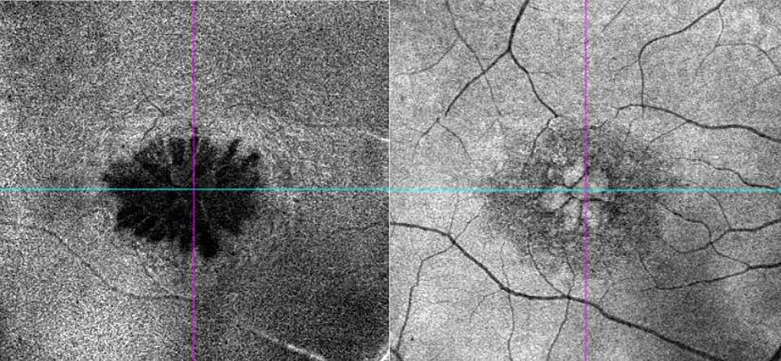

Fig. 2.

OCT angiography (OCT-A) of case 1 (right eye macula) showing classic petaloid appearance of cystoid macula edema typical of pseudophakic macula edema.

On discussion with her oncologist, she was instructed to temporarily cease ibrutinib (Imbruvica®). She was commenced on a course of topical steroids (prednisolone acetate 1% one drop 4 times a day). At subsequent follow-up 4 weeks later, there was a modest reduction in the bilateral macula edema. Topical treatment was discontinued. She was consented for intravitreal injection of steroids (triamcinolone acetate [Kenalog® 40 mg/mL, total volume 0.05 mL intravitreal injection]) in each eye, and was simultaneously commenced on topical anti-ocular hypertensive (brimonidine 0.2% and timolol 0.5% [Alphagan P®]) twice a day. She was closely followed with a 2-week and 4-week review for monitoring IOP which was not seen to rise. At the 2-month follow-up, she reported her vision had improved. Her BCVA was 6/6 bilaterally, IOP was within normal range, and there was complete resolution of the macula edema bilaterally. At 6 months, she remained stable with no further intervention needed. Her oncologist recommended permanent cessation of ibrutinib (Imbruvica®) pending periodic blood tests and is to consider alternative chemotherapeutic agent if required in the future.

Case 2

A 76-year-old female with polycythemia vera was commenced on ruxolitinib (Jakafi®) 8 years ago. She was switched to this medication after being intolerant to her previous drug treatment. She underwent uncomplicated cataract surgery 6 years ago with bilateral multifocal intraocular lenses and remained glasses-free. She presented to her ophthalmologist with blurred vision in both eyes for 2 months, more symptomatic in her right eye. On presentation, her best corrected visual acuity (Snellen BCVA) was 6/9 in the right eye and 6/7.5 in the left eye. Her IOPs were 16 mm Hg in each eye. The anterior segment of each eye showed clear, centrally placed posterior chamber multifocal intraocular lenses with no evidence of posterior capsular opacification. An optical coherence tomogram (OCT) revealed mild bilateral macule edema, most prominent in the right eye as shown in Figure 3. She was otherwise well, and apart from having radiation to an enlarged spleen, she had no other medical interventions. She did not take any other medication. Ruxolitinib (Jakafi®) was presumed to be the cause of her cystoid macula edema. She was commenced on a course of topical steroids (prednisolone acetate 1%, one drop 4 times a day) in each eye. At 4-week follow-up, there was resolution in the macula edema which completely resolved at 8-week follow-up. On advice from her oncologist, she was weaned from Ruxolitinib (Jakafi®) and remains stable. The CARE Checklist has been completed by the authors for this case report and is attached as supplementary material (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000535801).

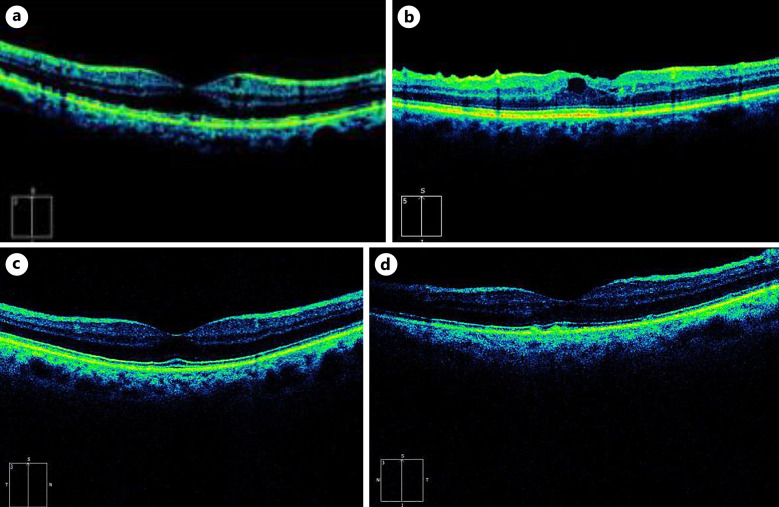

Fig. 3.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging of right and left eyes, respectively, of case 2. a Right eye at presentation with macula edema, central macular thickness (CMT) = 398 μm. b Left eye at presentation with macula edema, CMT = 309 μm. c Right eye posttreatment with resolution of macula edema, CMT = 212 μm. d Left eye posttreatment with resolution of macula edema, CMT = 215 μm.

Discussion

Pseudophakic macula edema or Irvine-Gass syndrome is one of the most common causes of reversible visual loss following routine cataract surgery. The etiology is believed to be due to an upregulation of inflammatory mediators in the aqueous fluid and vitreous gel after surgery causing a breakdown of the blood retinal barrier increasing vascular permeability [13, 14]. The classic cystic appearance at the level of the outer/inner plexiform retinal layer is the pathognomonic clinical sign seen as evidenced in the OCT angiography imaging of the right macula shown in Figure 2 from case 1. Some patients may have a higher predisposition for pseudophakic macula edema due to certain inherent risk factors, and these patients should be counseled accordingly prior to cataract surgery. Table 2 summarizes the common pre-disposing factors [15].

Table 2.

Risk factors for pseudophakic macula edema

| Routine cataract surgery | Complicated cataract surgery |

|---|---|

| Type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus | Iris manipulation/trauma |

| History of uveitis | Posterior capsular tear |

| Use of topical glaucoma medications (prostaglandin analogs (latanoprost), beta-blocker (timolol) | Vitreous loss/traction |

| Preexisting retinal vein occlusion | Anterior chamber IOL |

In the absence of these risk factors and in the presence of routine cataract surgery, the incidence of pseudophakic macula edema presenting within the first 3 months is low. An incidence of 1.46% has been reported in one large national case series of patients undergoing routine small-incision phacoemulsification surgery [16]. Other international studies report a comparable incidence in the range of 0.1–2.35%. Presentations of chronic pseudophakic macula edema after 3 months of initial surgery are rare as described in the literature [17, 18]. A late presentation of cystoid macula edema in a pseudophakic patient should therefore prompt clinicians to consider an alternative underlying cause such as chronic systemic medications. As Table 1 highlights, oral tyrosine kinase drugs are a well-known cause of macula edema, and this is further supported by our small case series in which these agents were the only long-term medication these patients were taking [3–12].

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are a unique group of drugs which target specific protein kinases responsible for abnormal growth. In doing so, they can help mediate a transformation from an uncontrolled neoplastic or autoimmune process into a state of chronic remission. However, their ocular toxicities are underestimated and likely also significantly underreported [19]. The mechanism of macula edema caused by these agents is still unclear. One patient in our series was on ibrutinib (Imbruvica®), a receptor binding tyrosine kinase, and the other on ruxolitinib (Jakafi®), an intracellular tyrosine kinase. Both drugs impact on downstream signaling of the inflammatory cascade [20]. A postulated theory that has been made in relation to some tyrosine kinase drugs causing uveitis is that they may contribute to dysregulation of tight junctions in endothelial cells in the uvea [21]. A similar theory may be applied at the level of the retinal vessels, leading to increased vascular permeability resulting in macula edema. The method of action of topical and intravitreal steroids in treating this macular edema relates to their anti-inflammatory properties which target proinflammatory mediators released due to increased vascular permeability. This has been well described in the literature [22].

It is important to note that in our patients as well as the cases reported in the literature, there was a variability in presentation of macula edema. In our case series, case 1 was not amenable to topical steroid treatment and required intravitreal steroid injection, while case 2 presented with milder signs that responded well to a short course of topical steroids. This highlights the need for clinicians to first astutely identify the underlying systemic medication, communicate with the patient’s physician to consider cessation or alternative treatment, and initiate first-line topical treatment prior to escalation of therapy. As in all ocular cases where long-term steroids are employed in treatment, cautious follow-up for IOP rises is paramount.

In both our patient cases, vision returned to premorbid levels. It seems likely this was as a result of localized ocular treatment in combination with cessation of the oral kinase drugs. However, this may not always be possible, especially in the challenging scenario where an alternative effective therapy may not exist and patients may need to continue with oral kinase therapy in the medium term. It has been recommended that these patients in particular be closely comanaged with regular ophthalmic follow-up. The important reason for this being that chronic macula edema if left untreated can cause disruption to the neurosensory retina, resulting in permanent reduction in vision [23].

Conclusion

Late presentations of pseudophakic macula edema must be approached with caution. Oral tyrosine kinase agents are being increasingly used in elderly patients to manage chronic autoimmune or neoplastic processes. These agents have been shown to cause ocular toxicity in particular chronic cystoid macula edema. Early identification, communication with the treating physician to consider alternative therapies, and prompt treatment of the macula edema can be vision-saving in these patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank clinical orthoptist Harini Prabakar for compilation of the figures used in this manuscript.

Statement of Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from each of the patients in this case series in order for permission for publication of the details of their medical case and any accompanying images, all of which have been de-identified. This was a retrospective review of patient clinical files and, as such, did not require ethical approval in accordance with local/national guidelines.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This study was not supported by any sponsor or funder.

Author Contributions

The authors of this manuscript are solely responsible for the case series, design, data collection, interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation. Dr. Christolyn Raj and Dr. Lewis Levitz contributed to data collection, analysis, and manuscript preparation. Ms. Harini Prabakar was involved in construction of Figures and Tables published in the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version.

Funding Statement

This study was not supported by any sponsor or funder.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated, collated, and analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author, Dr. Christolyn Raj.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Rotsos T, Moschos M. Cystoid macular edema. Clin Ophthalmol. 2008;2(4):919–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chiu Z, Goh J, Ling C, Lin M, Hall A. Ibrutinib-related uveitis: a case series. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022;25:101300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McClelland CM, HarocoposCuster GP. Periorbital edema secondary to imatinib mesylate. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;4:427–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Masood I, Negi A, Dua S. Imatinib as a cause of cystoid macular edema following uneventful phacoemulsification surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31(12):2427–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. GeorgalasPavesio IC, Ezra E. Bilateral cystoid macular edema in a patient with chronic myeloid leukaemia under treatment with imanitib mesylate: report of an unusual side effect. Graefe’s Archive Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;245(10):1585–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kusumi E, Arakawa A, Kami M, Kato D, Yuji K, Kishi Y, et al. Visual disturbance due to retinal edema as a complication of imatinib. Leukemia. 2004;18(6):1138–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Georgalas I. Imatinib. React Wkly. 2007;16:1176. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Roth D, Akbari S, Rothstein A. Macular ischemia associated with imatinib mesylate therapy for chronic myeloid leukemia. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2009;3(2):161–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dogan S, Esmaeli B. Ocular side effects associated with imatinib mesylate and perifosine for gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23(1):109–14, ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bajel A, Bassili S, Seymour JF. Safe treatment of a patient with CML using dasatinib after prior retinal oedema due to imatinib. Leuk Res. 2008;32(11):1789–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saenz-de-Viteri M, Cudrnak T. Bilateral cystoid macular edema in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019;60(3):842–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mirgh P, Ahmed R, Agrawal N, Bothra S, Mohan B, Garg A, et al. Knowing the flip side of the coin: ibrutinib associated cystoid macular edema. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2020;36(1):208–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yonekawa Y, Kim I. Pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23(1):26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sigler E, Randolph J, Kiernan DF. Longitudinal analysis of the structural pattern of pseudophakic cystoid macular edema using multimodal imaging. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254(1):43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Benitah N, Arroyo J. Pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2010;50(1):139–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. LevitzHodgeGrzybowski LCA, Kim S. Dual therapy for cystoid macular edema treatment after phacoemulsification surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2020;46(12):1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Henderson B, Kim J, Ament C, Ferrufino-Ponce ZK, Grabowska A, Cremers SL. Clinical pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Risk factors for development and duration after treatment. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33(9):1550–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Loewenstein A, Zur D. Postsurgical cystoid macular edema. Dev Ophthalmol. 2010;47:148–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Szilveszter K, Németh T, Mócsai A. Tyrosine kinases in autoimmune and inflammatory skin diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ferguson F, Gray NS. Kinase inhibitors: the road ahead. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17(5):353–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Niro A, Strippoli S, Alessio G, Sborgia L, Recchimurzo N, Guida M. Ocular toxicity in metastatic melanoma patients treated with mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitors: a case series. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160:959–967.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grzybowski A, Sikorski BL, Ascaso FJ, Huerva V. Pseudophakic cystoid macular edema: update 2016. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:1221–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johnson M. Etiology and treatment of macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147(1):11–21.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated, collated, and analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author, Dr. Christolyn Raj.