Abstract

Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis remains the gold standard treatment for patients with ulcerative colitis who desire restoration of intestinal continuity. Despite a significant cancer risk reduction after surgical removal of the colon and rectum, dysplasia and cancers of the ileal pouch or anal transition zone still occur and are a risk even if an anal canal mucosectomy is performed. Surgical care and maintenance after ileoanal anastomosis must include consideration of malignant potential along with other commonly monitored variables such as bowel function and quality of life. Cancers and dysplasia of the ileal pouch are rare but sometimes difficult-to-manage sequelae of pouch surgery.

Keywords: ileoanal pouch, anal transition zone, dysplasia, ulcerative colitis, pouch cancer, anal neoplasia

Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) provides the opportunity for improved lifestyle and quality of life by affording patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) the ability to maintain intestinal continuity following complete removal of the diseased colon and rectum. Cancer risk reduction is one indication for and result of proctocolectomy. Although UC-associated dysplasia or cancer risk is significantly reduced following this operation, dysplasia and cancer of the pouch remain long-term risks. Regardless of ileoanal anastomotic technique, the anal transition zone (ATZ) and pouch may be exposed to a long period of inflammation and subsequent neoplastic change. In the following discussion, we describe the contemporary understanding of the incidence, risk factors, treatment, and surveillance of dysplasia and cancer in UC patients with an ileoanal pouch.

IPAA and the Anal Transition Zone

History of the Ileoanal Anastomosis

In 1959, proctocolectomy was determined to be the gold standard surgical therapy for UC at the first bipartite meeting of the American Society of Proctology and Section of Proctology of the Royal Society of Medicine, 1 leading to an era of unprecedented colorectal innovation targeting improved quality of life for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Sir Alan Parks utilized a previously described mucosectomy technique 2 3 to join an ileoanal anastomosis using a reservoir constructed of ileum to the muscular wall of the anal canal in a procedure that he termed the restorative proctocolectomy (RPC). 4

Half a century and several design modifications later, RPC, or IPAA, remains the desired and most commonly performed operation for most patients with UC. Since its popularization, technical innovation has improved the IPAA design and increased application of the operation with the introduction of J-configuration. 5 The advent of surgical stapling tools further revolutionized the ileoanal anastomosis by decreasing operative times, standardizing a manual anastomosis, and shortening the rectal cuff. 6 7 Nonetheless, the optimal manner of ileoanal anastomosis remains a point of disagreement among many pouch surgeons as it relates to prevention of pouch neoplasia.

Anal Transition Zone

Two large studies have compared the two described anastomotic IPAA techniques, stapled versus handsewn, and demonstrated superiority of the double-stapled IPAA due to its technical ease and improved function. Importantly, these studies noted no significant difference in rates of dysplasia in the ATZ. 8 9 Additional work has demonstrated safety of preserving the ATZ without increasing risk for cancer development. 10

The ATZ is defined as a 5 to 10 mm area between the dentate line and the columnar epithelium of the distal rectum. 11 Histologically, the squamous epithelium of the anus transitions to the columnar epithelium of the rectum. 12 The ATZ is removed during a mucosectomy with handsewn IPAA and is preserved during a double-stapled IPAA. One might surmise that performing a handsewn anastomosis with mucosectomy beginning at the dentate line reduces cancer risk by manual removal of all inflamed, diseased mucosa to the dentate line. 13 However, when this theory was tested in the 1980s, researchers identified that islets of rectal mucosa persist in 20% of patients following mucosectomy with handsewn IPAA. 14 A subsequent study disproved the additional hypothesis that rectal mucosa regenerates after J-pouch creation. 15 Further studies have demonstrated the persistent risk of cancer even after a handsewn anastomosis. 16 Unlike the handsewn configuration, the stapled IPAA technique creates a mechanical double-stapled anastomosis 1 to 2 cm above the ATZ, leaving a cuff of distal rectum to help improve control of bowel function and sampling. Data evaluating malignant potential after this technique showed no evidence of increased cancer formation after double-stapled IPAA. 17 It is important to note that surgeons with significant expertise and experience in pelvic pouch construction recommend an individualized plan for each patient undergoing IPAA as to the optimal manner for reconstruction. For example, a mucosectomy with handsewn IPAA is strongly preferred for patients with dysplasia or cancer in the lower third of the rectum. 18

Epidemiology

Incidence

Cancers of the ileoanal pouch are rare but have important long-term complications of which to remain keenly aware. The epidemiology of this unusual entity is poorly understood. Research literature is primarily composed of case reports, systematic reviews, and a few meta-analyses, with a more recent consortium of experts publishing guidelines on management of pouch neoplasia with hopes of standardizing care and identifying ideal surgical and surveillance strategies for these challenging patients. 19

Dysplasia and Adenocarcinoma

Patients frequently present with advanced disease, leading to poor prognosis and making treatment very difficult. Cancers of the pouch or ATZ can be difficult to identify, as symptoms of pain, frequency, and bleeding can commonly be attributed to benign pouch pathologies such as pouchitis. When they do occur, in the authors' personal experience, they often present as advanced cancers requiring treatment modalities beyond simple pouch excision, such as pelvic exenteration. A recent systematic review estimated the risk of high-grade dysplasia and cancer in the ATZ and pouch to be 2 to 4.5% at 20 years following RPC. 20

In a large meta-analysis, Scarpa et al identified over 2,000 patients across a nearly 30-year period and reported a pooled 1.13% incidence of dysplasia in the ATZ, rectal cuff, and pouch body. 21 One of the largest prospective studies to date conducted by Remzi et al demonstrated a 4.5% incidence of dysplasia at 10 years. It is important to note that these patients were successfully managed with active surveillance and intervention such that no cancer developed during the study period. 10

Adenocarcinoma of the pouch has been reported to arise from both the rectal cuff and the ileal pouch mucosa. Selvaggi et al demonstrated an extremely low pooled incidence of pouch and cuff cancer of approximately 0.35% over a 20-year period. 22 Other cancers of the pouch have also been reported including squamous cell carcinoma 23 and lymphoma. 24

Risk Factors

Risk factors for development of pouch cancer in UC patients include preexisting dysplasia, disease duration over 10 years, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), villous atrophy, or chronic atrophic pouchitis (CAP). Pouch cancer risk is increased by a personal history of cancer or dysplasia, which, as discussed earlier, is not eliminated by mucosectomy and handsewn IPAA. PSC has been linked to pouch dysplasia and cancer. 25 Furthermore, duration of disease increases risk, particularly after 10 years. Chronic inflammation, often the result of long-standing severe pouchitis, leads to mucosal adaptation termed “type C” changes or CAP. 26 Some authors are investigating granular mechanisms such as colonic metaplasia, bile acids in pouchitis, and the microbiome. 27 28

Determining risk factors for pouch neoplasia is a critical part of individualizing care for patients undergoing IPAA. The risk for neoplasia must be a part of the detailed preoperative discussion prior to embarking on IPAA surgery, with the patient understanding his or her own risk factors, and the importance of considering these for the life of the pouch.

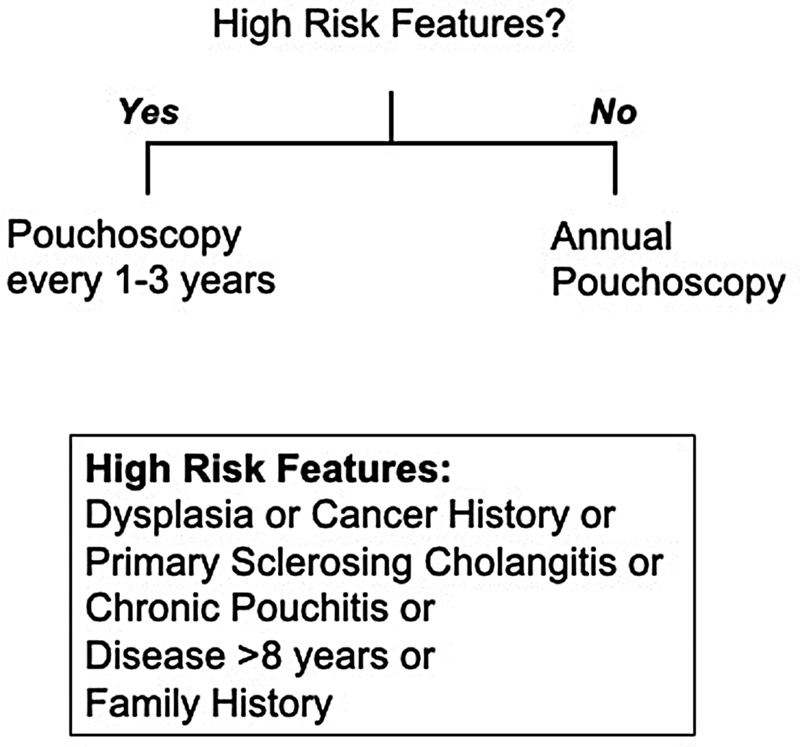

Endoscopic Surveillance

Given the limited data for incidence and limited understanding of risk for neoplasia after IPAA, the ideal manner in which to survey the pouch and ATZ is a highly debated topic. 29 Despite the presence of professional society guidelines regarding endoscopic pouch surveillance, a recent survey demonstrated significant heterogeneity in practice patterns. 30 Recently, the International Ileal Pouch Consortium was created to assimilate the available data on the topic and put forth its expert recommendation for endoscopic surveillance based on individual risk stratification. 19 The group recommended annual pouchoscopy in patients undergoing RPC/IPAA for existing dysplasia or malignancy. Other high-risk patients with PSC, refractory pouchitis or cuffitis, UC of more than 8 years, Crohn's disease of the pouch, or a family history of colorectal cancer are encouraged to undergo pouchoscopy at 1- to 3-year intervals, as summarized in Fig. 1 . For patients without high-risk features, pouchoscopy is recommended at 3-year intervals. The authors of this text emphasize again the importance of individualized, multidisciplinary care of these complex patients, with a thorough preoperative discussion to ensure that the patient understand the risk for pouch pathologies such as neoplasia and critical role for pouch surveillance for a lifetime.

Fig. 1.

Summary of recommendations from the International Ileal Pouch Consortium.

Management Options

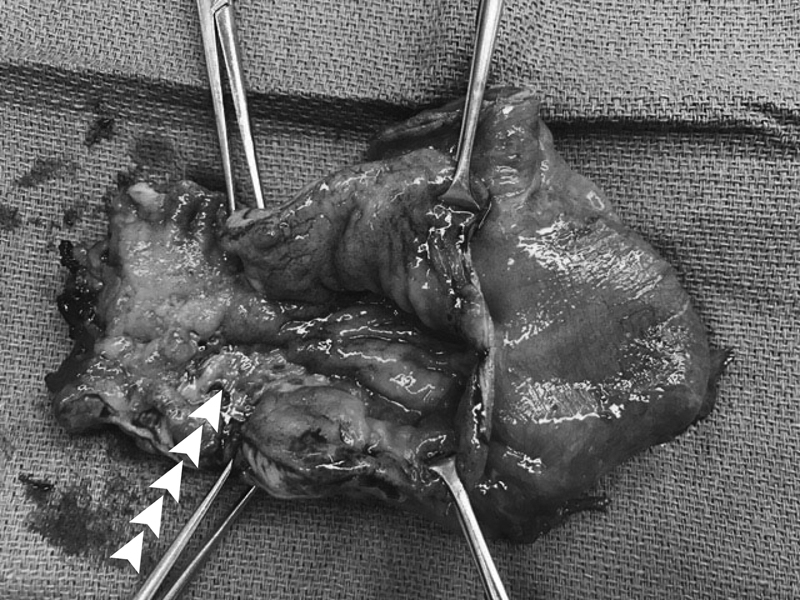

When dysplasia or cancer arises in the IPAA, the patient should ideally be referred to an IPAA center if not already being managed at one, to benefit from the experience and expertise of clinicians who are well versed in a largely uncommon occurrence. In general, management strategies for dysplasia and carcinoma of the pouch vary depending on the severity of disease presentation. One study reported on ATZ dysplasia and showed that dysplasia can be successfully managed by excision, mucosectomy, or pouch advancement 10 with individualized care. Cancers involving the rectal cuff and pouch should be treated by total pouch excision ( Fig. 2 ). Depending on the involvement of other pelvic organs, surgical extirpation may necessitate abdominoperineal pouch excision (APR) or pelvic exenteration. 31 Pedersen et al reported a cautionary tale of adenocarcinoma in a patient treated without anusectomy; a mucosectomy was performed but the anal sphincter/rectal cuff were left in place due to fibrosis with subsequent development of cancer in the residual rectal cuff over a decade later. 32 Taken together, these studies suggest that in certain patients, dysplasia may be locally excised with care, and that multidisciplinary, patient-centered plans are required to appropriately manage neoplasia and prevent cancer formation. When invasive malignancy presents, one must strongly consider pouch excision with APR or other proper oncologic management, which should supersede preserving continence. The authors of this text, in their personal experience, caution readers that these cancers are sometimes difficult to diagnose and often present in late stages or with involvement of adjacent pelvic organs, and aggressive and attentive management of dysplasia should occur to prevent cancer before it occurs, or to adequately treat it if it arises.

Fig. 2.

Specimen from ileal pouch excision for cancer ( arrows mark tumor).

It is unusual to have the opportunity to offer the patient control of continence after surgery for IPAA or ATZ cancers as the anal sphincter complex is removed. However, in highly selected individuals, continent ileostomy (CI) may be offered to provide an alternative to conventional ileostomy after IPAA excision. The CI can be performed safely with low complication rates at experienced referral centers. IPAA can often be converted to CI when the IPAA fails for nonneoplastic conditions if it is still usable. 33 34 However, the authors of this text do not recommend pouch salvage during conversion from IPAA to CI in the setting of neoplasia.

Outcomes

Dysplasia and cancer of IPAA are rare but have devastating complications in patients undergoing RPC for UC. Many patients with cancer of the pouch prevent with advanced disease. Kariv et al described a 30% mortality rate in patients with pouch adenocarcinoma. Of 11 pouch cancer patients identified from a population of 3,203 UC patients, 3 patients died within a year of diagnosis. 24 Unfortunately, the length of follow-up after surgical extirpation limits a better understanding of survival after diagnosis and management. 22

Conclusions

RPC with IPAA significantly reduces risk of UC-related dysplasia and carcinoma but does not completely eliminate risks of pouch cancers regardless of excisional surgical technique. Patients at highest risk for neoplasia include those with a preexisting dysplasia or cancer diagnosis. Surveillance should be considered in all, but certainly tailored to those at greatest lifetime risk. Management strategies vary based on disease severity, but cancer of the pouch should be managed aggressively and necessitate complete pouch removal. Every effort must be made to manage these very complex patients in a specialty center that offers multidisciplinary, experienced care of this uncommon but very important pathology.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Reichman H R.Indications for surgical treatment of chronic idiopathic ulcerative colitis Proc R Soc Med 195952(suppl 1):15–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devine J, Webb R. Resection of the rectal mucosa, colectomy, and anal ileostomy with normal continence. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1951;92(04):437–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peck D A, German J D, Jackson F C. Rectal resection for benign disease: a new technic. Dis Colon Rectum. 1966;9(05):363–366. doi: 10.1007/BF02617104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parks A G, Nicholls R J.Proctocolectomy without ileostomy for ulcerative colitis BMJ 19782(6130):85–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Utsunomiya J, Iwama T, Imajo M et al. Total colectomy, mucosal proctectomy, and ileoanal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1980;23(07):459–466. doi: 10.1007/BF02987076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fazio V W, O'Riordain M G, Lavery I Cet al. Long-term functional outcome and quality of life after stapled restorative proctocolectomy Ann Surg 199923004575–584., discussion 584–586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heald R J, Allen D R. Stapled ileo-anal anastomosis: a technique to avoid mucosal proctectomy in the ileal pouch operation. Br J Surg. 1986;73(07):571–572. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800730719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lovegrove R E, Constantinides V A, Heriot A G et al. A comparison of hand-sewn versus stapled ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) following proctocolectomy: a meta-analysis of 4183 patients. Ann Surg. 2006;244(01):18–26. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000225031.15405.a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirat H T, Remzi F H, Kiran R P, Fazio V W.Comparison of outcomes after hand-sewn versus stapled ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in 3,109 patients Surgery 200914604723–729., discussion 729–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Remzi F H, Fazio V W, Delaney C P et al. Dysplasia of the anal transitional zone after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: results of prospective evaluation after a minimum of ten years. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46(01):6–13. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6488-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson-Fawcett M W, Mortensen N J. Anal transitional zone and columnar cuff in restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg. 1996;83(08):1047–1055. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holder-Murray J, Fichera A. Anal transition zone in the surgical management of ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(07):769–773. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Régimbeau J M, Panis Y, Pocard M, Hautefeuille P, Valleur P.Handsewn ileal pouch-anal anastomosis on the dentate line after total proctectomy: technique to avoid incomplete mucosectomy and the need for long-term follow-up of the anal transition zone Dis Colon Rectum 2001440143–50., discussion 50–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heppell J, Weiland L H, Perrault J, Pemberton J H, Telander R L, Beart R W., Jr Fate of the rectal mucosa after rectal mucosectomy and ileoanal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26(12):768–771. doi: 10.1007/BF02554744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Connell P R, Pemberton J H, Kelly K A. Motor function of the ileal J pouch and its relation to clinical outcome after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. World J Surg. 1987;11(06):735–741. doi: 10.1007/BF01656596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Riordan J M, Kirsch R, Mohseni M, McLeod R S, Cohen Z. Long-term risk of adenocarcinoma post-ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27(03):405–410. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.M'Koma A E, Moses H L, Adunyah S E. Inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancer: proctocolectomy and mucosectomy do not necessarily eliminate pouch-related cancer incidences. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26(05):533–552. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1137-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirat H T, Remzi F H. Technical aspects of ileoanal pouch surgery in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2010;23(04):239–247. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1268250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen B, Kochhar G S, Kariv R et al. Diagnosis and classification of ileal pouch disorders: consensus guidelines from the International Ileal Pouch Consortium. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(10):826–849. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Cosquer G, Buscail E, Gilletta C et al. Incidence and risk factors of cancer in the anal transitional zone and ileal pouch following surgery for ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14(03):530. doi: 10.3390/cancers14030530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scarpa M, van Koperen P J, Ubbink D T, Hommes D W, Ten Kate F J, Bemelman W A. Systematic review of dysplasia after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg. 2007;94(05):534–545. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selvaggi F, Pellino G, Canonico S, Sciaudone G. Systematic review of cuff and pouch cancer in patients with ileal pelvic pouch for ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(07):1296–1308. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pellino G, Kontovounisios C, Tait D, Nicholls J, Tekkis P P. Squamous cell carcinoma of the anal transitional zone after ileal pouch surgery for ulcerative colitis: systematic review and treatment perspectives. Case Rep Oncol. 2017;10(01):112–122. doi: 10.1159/000455898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kariv R, Remzi F H, Lian Let al. Preoperative colorectal neoplasia increases risk for pouch neoplasia in patients with restorative proctocolectomy Gastroenterology 201013903806–812., 812.e1–812.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ståhlberg D, Veress B, Tribukait B, Broomé U. Atrophy and neoplastic transformation of the ileal pouch mucosa in patients with ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis: a case control study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46(06):770–778. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6655-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veress B, Löfberg R, Bergman L. Microscopic colitis syndrome. Gut. 1995;36(06):880–886. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.6.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuisma J, Mentula S, Luukkonen P, Jarvinen H, Kahri A, Farkkila M. Factors associated with ileal mucosal morphology and inflammation in patients with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46(11):1476–1483. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6796-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duffy M, O'Mahony L, Coffey J C et al. Sulfate-reducing bacteria colonize pouches formed for ulcerative colitis but not for familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45(03):384–388. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6187-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Derikx L A, Nissen L H, Oldenburg B, Hoentjen F. Controversies in pouch surveillance for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn's Colitis. 2016;10(06):747–751. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gu J, Remzi F H, Lian L, Shen B. Practice pattern of ileal pouch surveillance in academic medical centers in the United States. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2016;4(02):119–124. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gov063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ault G T, Nunoo-Mensah J W, Johnson L, Vukasin P, Kaiser A, Beart R W., Jr Adenocarcinoma arising in the middle of ileoanal pouches: report of five cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(03):538–541. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e318199effe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pedersen M E, Rahr H B, Fenger C, Qvist N. Adenocarcinoma arising from the rectal stump eleven years after excision of an ileal J-pouch in a patient with ulcerative colitis: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(07):1146–1148. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9238-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aytac E, Ashburn J, Dietz D W. Is there still a role for continent ileostomy in the surgical treatment of inflammatory bowel disease? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(12):2519–2525. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aytac E, Dietz D W, Ashburn J, Remzi F H. Is conversion of a failed IPAA to a continent ileostomy a risk factor for long-term failure? Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62(02):217–222. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]