Summary

Background

Previous research has suggested that people with severe mental illness are at elevated risk of both violence perpetration and violent victimisation, with risk of the latter being perhaps greater than the former. However, few studies have examined risk across both outcomes.

Methods

Using a total population approach, the absolute and relative risks of victimisation and perpetration were estimated for young men and women across the full psychiatric diagnostic spectrum. Information on mental disorder status was extracted from national registers and information on violent victimisation and perpetration outcomes from police records. The follow-up was from age 15 to a maximum of 31 years, with most of the person-time at risk pertaining to cohort members aged in their early twenties. Both absolute risk (at 1 and 5 years from onset of illness) and relative risk were estimated.

Findings

Both types of violent outcome occurred more frequently amongst those with mental illness than the general population. However, whether risk of one was greater than the other depended on a range of factors, including sex and diagnosis. Men with a mental disorder had higher absolute risks of both outcomes than women [victimisation: Cin (5 year) = 7.15 (6.88–7.42) versus Cin (5 year) = 4.79 (4.61–4.99); perpetration: Cin (5 year) = 8.17 (7.90–8.46) versus Cin (5 year) = 1.86 (1.75–1.98)], as was the case with persons in the general population without a recorded mental illness diagnosis. Women with mental illness had higher absolute risk of victimisation than perpetration, which was also true for men and women without mental illness. However, the opposite was true for men with mental illness. Men and women with diagnoses of personality disorders, substance use disorders, and schizophrenia-spectrum disorders were at highest risk of victimisation and perpetration.

Interpretation

Strategies developed to prevent violent victimisation and violence perpetration may need to be tailored for young adults with mental disorders. There may also be a benefit in taking a sex-specific approach to prevention in this group.

Funding

This study was supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant awarded to the first author.

Keywords: Victimisation, Perpetration, Risk, Violence, Mental illness

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Prior research has suggested that people with severe mental illness are at greater risk of both violent victimisation and violence perpetration than those without mental illness. However, few studies have examined both outcomes within the same sample, and the limited available evidence shows mixed findings.

Added value of this study

This study used population-level data from Denmark to examine both the absolute and relative risks of police-reported violent victimisation and violence perpetration in young adults with mental illness. We reported on data from men and women separately, which is particularly important in this area as criminal justice contact patterns vary by sex. Additionally, we compared risk across the full psychiatric diagnostic spectrum over time.

Implications of all the available evidence

The current available evidence suggests that young adults with mental illness are at greater risk of violent victimisation and violence perpetration than those without mental illness, though the absolute and relative risks of these outcomes are dependent on variables such as sex and diagnosis. Men with mental illness generally show higher absolute risk of both outcomes than women with mental illness. Whereas women with mental illness have higher absolute risks of victimisation, men with mental illness have higher risk of perpetration. The risk of both outcomes is particularly elevated for individuals with personality disorders, substance use disorders, and schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Notably, considering the source of the data—including whether a study was based on self-report or official records—is crucial when analyzing risk for violent outcomes. Evidence-informed strategies to reduce the risks of violent victimisation and violence perpetration are urgently needed.

Introduction

Mental illness is associated with a higher likelihood of criminal justice system contact. An increased risk of contact following perpetration of violence is well established1 while, more recently, risk of justice contact related to experiences of violent victimisation has also been demonstrated to be elevated among persons with mental illness.2 The recent focus on risk of violent victimisation, as opposed to perpetration, has to some extent been motivated by the need to address stigmatising views propagated by the media and held by the public about those with mental illness, with anti-stigma campaign statements often made about the risk of victimisation being greater than perpetration for those with mental illness.3 Supporting this approach, an influential review of US studies published over a decade ago concluded that “victimization is a greater public health concern than perpetration” (p.153), although the lack of studies examining both outcomes within the same study cohort was acknowledged.4 There have, however, been few studies that have attempted to bridge this evidence gap.

A recent systematic review identified only three studies that have examined both violent victimisation and violence perpetration risk within a cohort that included both individuals with mental illness and general population controls.5 One Ethiopian study found a higher rate of victimisation than perpetration for persons with mental illness based on self-report data.6 Two larger register-based studies conducted in Sweden and Denmark found higher cumulative incidence rates of perpetration than victimisation based on data obtained from official records,7,8 although in both studies victimisation data was obtained from health records. Crime victimisation is not routinely recorded in health records, and while health contact for treatment of injuries can be a proxy for identifying violent victimisation, it is a measure that has two serious flaws. Firstly, many people who are victims of violence do not require or receive hospital treatment. Secondly, many individuals presenting to health services and coded as sustaining an injury during an episode of interpersonal violence will not be assault victims. With numerous physical altercations a clear distinction between perpetrator and victim is not evident; for instance, when two persons, or two groups of people, have fought each other by mutual consent, or when the injured individual initiated the violence. In the current study, we used police records to identify occurrences of both violent victimisation and violence perpetration, improving the validity of measurement of victimisation and relying on a common data source for both victimisation and perpetration.

In this population-based study focusing on young adults, we aimed to establish the absolute risk of violent victimisation and violence perpetration leading to criminal justice contact at 1 year and 5 years after onset of mental illness, across the full psychiatric diagnostic spectrum, and in men and women separately. Examination of sex differences is important given the evidence that patterns of criminal justice contact for those with mental illness vary greatly between men and women.9 In addition to establishing absolute risk following onset of mental illness, we also aimed to determine relative risks (incidence rate ratios) for people with mental illnesses compared to the general population.

Method

Data sources and study cohort

Cohort members were all persons born in Denmark between January 1, 1985, and December 31, 2001, and who were living in Denmark on their 15th birthday. We constructed the cohort using the Danish Civil Registration System (CRS; 10), which contains complete information since 1968 on the unique personal identification number, sex, age, and daily updated information on migration and vital status. A flowchart outlining the steps of exclusion and the resulting included study cohort can be found in Supplementary Figure S1.

Violent victimisation and perpetration outcome measures

We examined two violent crime outcomes:

-

1.

First date of being a victim of any police-recorded violent crime (date of victimisation event).

-

2.

First date of being a perpetrator of any police-recorded violent crime (date of conviction for violence perpetration).

From the Central Crime Register, we extracted information on all penal code violations11; the violent crimes captured in this study thus include all types and severity of violent crime, with the exception of sexual offences. Only guilty verdicts resulting in custodial sentences, suspended sentences, conditional withdrawal of charges, fines, and sentences to psychiatric treatment were included. We defined violent crime perpetration or being a victim of a violent crime where there was a guilty verdict referring to offence codes starting with “12” in the Central Crime Register (Supplementary Table S1) and the relevant date used was the date of victimisation event for violent victimisation and conviction for violence perpetration. The age of criminal responsibility in Denmark is 15, meaning that the follow-up period spans from 15th birthday to a maximum follow-up age of 31 years, thereby focusing on young adulthood.

Mental disorder exposure measures

We extracted information on mental disorder status using data from the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register,12 including data on all admissions to psychiatric wards/hospitals since 1969 and all psychiatric outpatient treatment episodes since 1995. Additionally, we obtained information from the Danish National Patient Register13 for data on all admissions to somatic wards/hospitals since 1977 and outpatient contacts since 1995. In the ICD-10 period from 1994,14 we defined diagnosed mental disorder as usage of any code in the F-chapter. Similarly, in the ICD-815 period (up to and including 1993), we defined mental disorder as usage of any code in the range 290xx–315xx. We defined 10 subgroups of mental disorder16 as shown in Supplementary Table S2. We used the ICD-8 codes to ensure that we could identify the first recorded contact with services among the oldest cohort members. Given the extent of mental disorder co-morbidity apparent at a population level,17 diagnostic subgroups were not mutually exclusive. For each mental disorder, date of onset was defined as the first day of the first psychiatric contact for the diagnosis of interest.

Statistical analysis

Cohort members were followed from Jan 1, 2001, or from their 15th birthday, whichever came last, and until first event of interest (i.e., first victim/perpetrator offence conviction), or until death, emigration, or the study's observation period end date (December 31, 2016), whichever came first. We applied Poisson Regression to approximate Cox regression to analyse time to first victimisation/perpetration event.18 First contact with any F-diagnosis, and then with each diagnostic subgroup, was treated as a time-dependent covariate. Thus, individuals with first contact prior to the start of follow-up were treated as being exposed throughout the follow-up period. For the incidence rate ratios, which measured the relative risk of the outcome, we compared persons with each F-diagnosis to those without. First incidents were examined in one-year groups, stratified by sex, with age and calendar time treated as covariates.

We also calculated the absolute risk (cumulative incidence) of experiencing a violent victimisation/perpetration event (for 1 year and 5 years after first psychiatric service contact). Follow-up for first victimisation/perpetration event commenced on the inpatient discharge date or end of outpatient treatment for the first mental disorder contact. We censored individuals with a record of being a violent crime victim or perpetrator before their first recorded inpatient or outpatient psychiatric hospital episode. For the overall group with any mental disorder, 44.1% were censored for this reason in the analysis of victimisation risk and 42.3% were censored in the analysis of perpetration risk. We applied the Aalen-Johansen estimator to calculate the cumulative incidence functions (CIFs) of first victimisation/perpetration considering competing risks from all-cause mortality and emigration.18 Due to follow-up for the outcome being impossible prior to age 15 years, individuals with first psychiatric services contact prior to this age were excluded from the calculation of absolute risk. Thus, we were unable to calculate absolute risks for those mental disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood. To enable comparison of absolute risks for the two outcomes in individuals with an F-diagnosis versus the equivalent absolute risks in the general population, we included a population-based comparison group matched by sex and exact birthday by randomly selecting 10 persons for each cohort member with an F-diagnosis. The comparators had not been exposed before matching but could be exposed after the matching date. Absolute risk was calculated as a function of time since onset of diagnosis within one year and five years. Absolute risk of victimisation, perpetration and a combined outcome variable (i.e., either victimisation or perpetration) were calculated separately. An overview of parental income for persons at risk of victimisation and perpetration respectively can be found in Supplementary Tables S3–S6. All analyses were carried out using SAS software (version 9.4.).

Study approval

The Danish Data Protection Agency and the Danish Health Data Authority approved this study. According to Danish law, informed consent is not required for register-based studies. All data were de-identified and are not recognisable at the individual level. The data that support the findings of this study are available from Statistics Denmark. Data access requires the completion of a detailed application form from the Danish National Board of Health, and Statistics Denmark. For more information on accessing the data, see https://www.dst.dk/en.

Results

For analyses examining violent victimisation as the outcome, a total of 1,119,583 individuals were at risk at least on the first day of follow-up resulting in 8,786,886 person-years at risk (and a mean follow-up duration of 7.77 years). Mean age at the end of follow-up (due to censoring or being a victim of violence) was 23.0 years old. A total of 55,465 individuals (68.6% men) were victims and the mean age at the time of victimisation was 19.83 years (SD = 3.45).

For analyses examining violence perpetration as the outcome, a total of 1,131,106 individuals were at risk at least on the first day of follow-up resulting in 8,974,864 person-years at risk (and a mean follow-up of 8.02 years). Mean age at the end of follow-up (due to censoring or being a perpetrator) was 22.9 years old. A total of 36,932 individuals (85.3% men) were perpetrators of violence and the mean age at the time of perpetration was 19.30 years (SD = 3.05).

Absolute risks (cumulative incidence) up to 1 year

As shown in Table 1, amongst men with onset of any type of mental disorder, 1.85% experienced violent victimisation within the first year (compared to 0.83% of matched comparators); 2.31% of were convicted of a violent offence as perpetrators (0.65% of comparators), and 3.63% experienced either outcome (1.35% of comparators). Absolute risks for both outcomes were lower for women - 1.11% of those with any mental disorder experienced violent victimisation (0.32% of comparators) within a year of illness onset, 0.50% were convicted for a violent offence (0.08% of comparators), and 1.48% had either outcome (0.34% of comparators).

Table 1.

Sex-specific absolute risks (cumulative incidence) of violent crime victimisation and perpetration up to 1 year following onset of mental disorder.

| Men |

Women |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n events | Cumulative incidence % (95% CI) | n events | Cumulative incidence % (95% CI) | |

| Violent crime victimisation (1 year) | ||||

| No mental disorder | 4032 | 0.83 (0.80–0.85) | 2186 | 0.32 (0.31–0.34) |

| Any mental disorder | 857 | 1.85 (1.73–1.98) | 727 | 1.11 (1.03–1.19) |

| 1. Substance use disorders | 600 | 2.45 (2.26–2.65) | 349 | 1.80 (1.62–2.00) |

| 2. Schizophrenia-spectrum | 83 | 1.28 (1.03–1.58) | 22 | 1.00 (0.77–1.28) |

| 3. Mood disorders | 258 | 1.53 (1.29–1.79) | 147 | 1.18 (1.04–1.33) |

| 4. Neurotic disorders | 355 | 1.88 (1.70–2.08) | 469 | 1.28 (1.17–1.40) |

| 5. Eating disorders | – | – | 41 | 0.46 (0.34–0.62) |

| 6. Personality disorder | 102 | 2.40 (1.97–2.89) | 224 | 1.71 (1.50–1.95) |

| Violent crime perpetration (1 year) | ||||

| No mental disorder | 3219 | 0.65 (0.62–0.66) | 607 | 0.08 (0.07–0.10) |

| Any mental disorder | 1088 | 2.31 (2.19–2.46) | 344 | 0.50 (0.45–0.56) |

| 1. Substance use disorders | 853 | 3.45 (3.23–3.68) | 232 | 1.13 (0.99–1.28) |

| 2. Schizophrenia-spectrum | 191 | 2.93 (2.54–3.36) | 56 | 0.90 (0.69–1.16) |

| 3. Mood disorders | 150 | 1.52 (1.29–1.77) | 96 | 0.42 (0.34–0.51) |

| 4. Neurotic disorders | 429 | 2.21 (2.01–2.42) | 202 | 0.52 (0.46–0.60) |

| 5. Eating disorders | – | – | 13 | 0.14 (0.08–0.24) |

| 6. Personality disorder | 179 | 4.27 (3.69–4.92) | 126 | 0.89 (0.75–1.06) |

| Violent crime victimisation or perpetration (1 year) | ||||

| No mental disorder | 6401 | 1.35 (1.32–1.38) | 2634 | 0.34 (0.37–0.40) |

| Any mental disorder | 1563 | 3.63 (3.47–3.81) | 962 | 1.48 (1.39–1.58) |

| 1. Substance use disorders | 1120 | 5.11 (4.82–5.41) | 489 | 2.59 (2.37–2.83) |

| 2. Schizophrenia-spectrum | 208 | 3.63 (3.16–4.13) | 102 | 1.76 (1.44–2.12) |

| 3. Mood disorders | 232 | 2.57 (2.26–2.92) | 321 | 1.47 (1.32–1.64) |

| 4. Neurotic disorders | 610 | 3.51 (3.25–3.80) | 591 | 1.63 (1.50–1.76) |

| 5. Eating disorders | – | – | 50 | 0.57 (0.43–0.74) |

| 6. Personality disorder | 207 | 5.67 (4.95–6.46) | 497 | 2.28 (2.03–2.55) |

NB. Diagnostic categories are not mutually exclusive/hierarchical.

NB. ‘No mental disorder’ cohort is a matched cohort (matched 10:1 for age and sex with the any mental disorder cohort; index date matches first diagnosis).

NB. ‘Any mental disorder’ includes all ICD-10 code F diagnoses (i.e., mental and behavioural disorders) and is not limited to the specific disorder groups presented.

NB. Total sample sizes were as following: 1,119,583 (51.2% male) individuals included in victimisation analysis, 1,131,106 (51.3% male) individuals included in perpetration analysis, and 1,119,462 (51.2% male) individuals included in the analysis of either outcome.

Specific mental disorders

When onset of specific mental disorders was considered (Table 1), violence perpetration being more common than victimisation for men persisted for all diagnostic subgroups; in women victimisation was more common that perpetration across the diagnostic spectrum. The absolute risk of violent victimisation for men at one year varied from 1.28% for those with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders to 2.45% for those with substance use disorders. For violence perpetration, the proportion at one-year varied from 1.52% for mood disorders to 4.27% for those with personality disorders. For perpetration and violence combined, the variation by diagnostic group was similar, varying from 2.57% for mood disorders to 5.67% for personality disorders. For women, at one-year post-onset, the absolute risk of violent victimisation was highest for those with substance use disorders (1.80%; lowest for those with eating disorders, 0.46%). The same was true of both violence perpetration (1.13% for substance use disorders; 0.14% for eating disorders) and when either outcome was considered (2.59% for substance use disorders; 0.57% for eating disorders).

For absolute risks up to 1 year, it should be noted that the temporal order of exposure and outcome cannot be assured given the fact that the date of illness onset in relation to health service contact and the date of offense in relation to conviction are not identical.

Absolute risks (cumulative incidence) up to 5 years

These results are presented in Table 2. When follow-up from onset of mental illness was extended to 5 years, 7.15% of men with any type of mental illness experienced violent victimisation, 8.17% violence perpetration, and 12.81% either outcome, all substantially higher than for individuals without mental disorder. For women, absolute risk for those with any mental illness also remained much higher than for those without illness but again the proportions affected were less than seen for men. Violent victimisation was experienced by 4.79% of women with any mental disorder within 5 years of onset; the rate for violence perpetration was 1.86% and the risk of either outcome occurring was 5.89%.

Table 2.

Sex-specific absolute risks (cumulative incidence) of violent crime victimisation and perpetration up to 5 years following onset of mental disorder.

| Men |

Women |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n events | Cumulative incidence % (95% CI) | n events | Cumulative incidence % (95% CI) | |

| Violent crime victimisation (5 years) | ||||

| No mental disorder | 8740 | 3.79 (3.72–3.79) | 14,573 | 1.68 (1.64–1.71) |

| Any mental disorder | 2659 | 7.15 (6.88–7.42) | 2465 | 4.79 (4.61–4.99) |

| 1. Substance use disorders | 1819 | 8.92 (8.52–9.32) | 1109 | 7.01 (6.61–7.43) |

| 2. Schizophrenia-spectrum | 612 | 6.32 (5.64–7.01) | 214 | 4.68 (4.08–5.34) |

| 3. Mood disorders | 403 | 5.41 (4.89–5.96) | 762 | 4.41 (4.10–4.73) |

| 4. Neurotic disorders | 987 | 6.89 (6.47–7.33) | 1481 | 5.29 (5.03–5.57) |

| 5. Eating disorders | – | – | 180 | 2.65 (2.28–3.06) |

| 6. Personality disorder | 287 | 8.35 (7.43–9.33) | 687 | 6.75 (6.26–7.26) |

| Violent crime perpetration (5 years) | ||||

| No mental disorder | 11,222 | 2.83 (2.78–2.88) | 2072 | 0.38 (0.36–0.40) |

| Any mental disorder | 3157 | 8.17 (7.90–8.46) | 1027 | 1.86 (1.75–1.98) |

| 1. Substance use disorders | 2450 | 11.73 (11.29–12.18) | 614 | 3.52 (3.25–3.80) |

| 2. Schizophrenia-spectrum | 527 | 10.03 (9.21–10.89) | 191 | 3.99 (3.45–4.59) |

| 3. Mood disorders | 435 | 5.63 (5.11–6.18) | 292 | 1.62 (1.44–1.81) |

| 4. Neurotic disorders | 1174 | 7.72 (7.28–8.17) | 654 | 2.20 (2.03–2.37) |

| 5. Eating disorders | – | – | 53 | 0.79 (0.60–1.03) |

| 6. Personality disorder | 406 | 11.57 (10.51–12.69) | 376 | 3.34 (3.01–3.69) |

| Violent crime victimisation or perpetration (5 years) | ||||

| No mental disorder | 22,121 | 5.87 (5.79–5.95) | 10,075 | 1.92 (1.88–1.96) |

| Any mental disorder | 4479 | 12.81 (12.45–13.17) | 3032 | 5.89 (5.68–6.10) |

| 1. Substance use disorders | 3171 | 17.17 (16.61–17.73) | 1411 | 8.99 (8.54–9.45) |

| 2. Schizophrenia-spectrum | 608 | 13.32 (12.31–14.36) | 335 | 7.44 (6.67–8.26) |

| 3. Mood disorders | 611 | 8.77 (8.09–9.47) | 925 | 5.41 (5.07–5.77) |

| 4. Neurotic disorders | 1591 | 11.83 (11.27–12.41) | 1824 | 6.57 (6.27–6.87) |

| 5. Eating disorders | – | – | 214 | 3.19 (2.78–3.65) |

| 6. Personality disorder | 471 | 15.47 (14.17–16.82) | 870 | 8.71 (8.15–9.29) |

NB. Diagnostic categories are not mutually exclusive/hierarchical.

NB. ‘No mental disorder’ cohort is a matched cohort (matched 10:1 for age and sex with the any mental disorder cohort; index date matches first diagnosis).

NB. ‘Any mental disorder’ includes all ICD-10 code F diagnoses (i.e., mental and behavioural disorders) and is not limited to the specific disorder groups presented).

NB. Total sample sizes were as following: 1,119,583 (51.2% male) individuals included in victimisation analysis, 1,131,106 (51.3% male) individuals included in perpetration analysis, and 1,119,462 (51.2% male) individuals included in the analysis of either outcome.

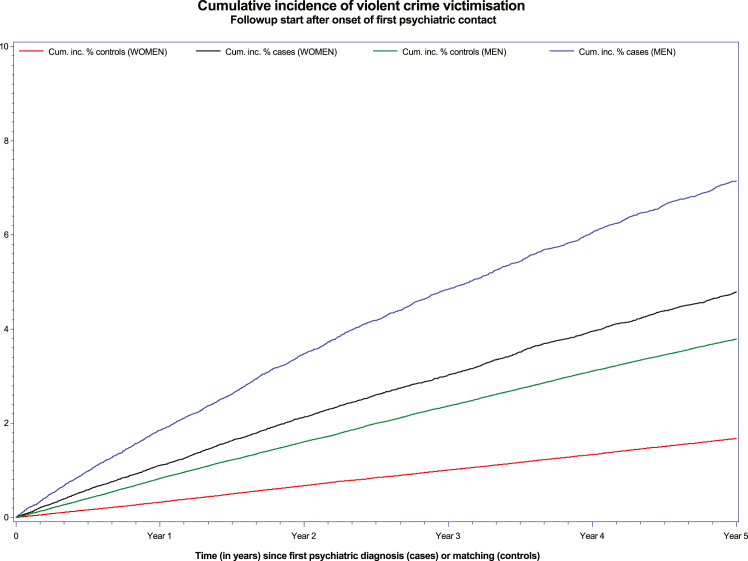

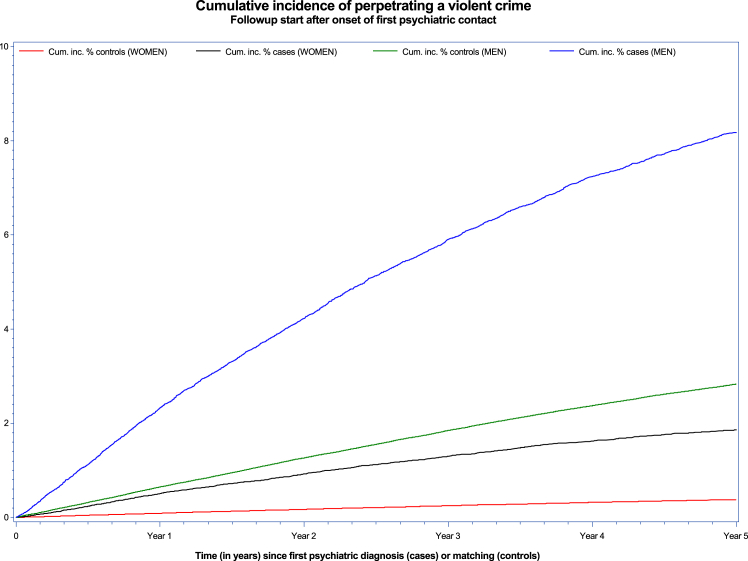

Figs. 1 and 2 present the absolute risk for violent victimisation and perpetration over time elapsed since onset, with findings presented separately for men and women, and for those with onset of any mental disorder compared to those with no mental disorder. For violent victimisation, absolute risk was highest across the period for men with any mental disorder, followed by women with mental disorder, male comparators, and then female comparators. For violence perpetration, a slightly different pattern emerged, with the highest absolute risk seen for men with any mental disorder, followed by male comparators, women with any mental disorder, and, finally, female comparators.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative incidence of violent crime victimisation for women and men with psychiatric diagnosis and matched controls.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidence of violent crime perpetration for women and men with psychiatric diagnosis and matched controls.

Specific mental disorders

Across the diagnostic spectrum, absolute risks at 5 years post-onset were higher for both outcomes, compared to those without disorder, for both men and women. For men, the absolute risk of violence perpetration remained higher than violent victimisation across the diagnostic subgroups but the gap between the two outcomes was narrower than at 1 year post-onset. For women, the absolute risk of violent victimisation at 5 years post-onset was higher than for violence perpetration across the diagnostic subgroups, with the gap between the two outcomes narrowest for those with schizophrenia (as at 12 months). The highest absolute risk of either outcome at 5 years was for those with substance use disorders (17.17% for men; 8.99% for women).

Relative risks (incidence rate ratios)

Overall, men showed a greater risk of both outcomes compared to women, with a victimisation rate of 2.15 (2.11, 2.19) times as high and a perpetration rate of 5.66 (5.50, 5.83) times as high as the rate for women, adjusted for age and calendar time. Compared to men without mental disorder, the incidence of violent victimisation following illness onset was 1.83 (95% CI 1.78–1.87) times higher amongst those with any mental disorder; the incidence rate ratio for violence perpetration was 2.58 (2.52–2.64) (Table 3). For women, the incidence rate ratio was 3.07 (2.97–3.17) for violent victimisation and 5.48 (5.19–5.79) for perpetration.

Table 3.

Sex-specific relative risks (incidence rate ratios) for violent crime victimisation and perpetration following onset of mental disorder compared to no mental disorder (follow-up from age 15 years, 2001–2016).

| Men |

Women |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n events | Person years at risk | rate per 1000 person years | Incident rate ratio (95% CI) | n events | Person years at risk | Rate per 1000 person years | Incident rate ratio (95% CI) | |

| Violent crime victimisation | ||||||||

| No mental disorder | 30,661 | 3,865,378 | 7.93 | 1 | 12,143 | 3,785,050 | 3.21 | 1 |

| Any mental disorder | 7402 | 561,914 | 13.17 | 1.83 (1.78–1.87) | 5259 | 574,544 | 9.15 | 3.07 (2.97–3.17) |

| 1. Substance use disorders | 2818 | 156,562 | 18.00 | 2.47 (2.38–2.57) | 1763 | 131,711 | 13.39 | 3.85 (3.67–4.05) |

| 2. Schizophrenia-spectrum | 456 | 36,865 | 12.37 | 1.73 (1.58–1.90) | 338 | 35,609 | 9.49 | 2.57 (2.30–2.86) |

| 3. Mood disorders | 592 | 54,220 | 10.92 | 1.55 (1.43–1.68) | 1098 | 127,441 | 8.62 | 2.44 (2.29–2.59) |

| 4. Neurotic disorders | 1873 | 142,646 | 13.13 | 1.78 (1.70–1.87) | 2735 | 263,414 | 10.38 | 3.12 (2.99–3.25) |

| 5. Eating disorders | 70 | 7040 | 9.94 | 1.26 (0.99–1.59) | 376 | 70,833 | 5.31 | 1.39 (1.26–1.54) |

| 6. Personality disorder | 379 | 23,167 | 16.36 | 2.29 (2.07–2.53) | 945 | 71,965 | 13.13 | 3.74 (3.50–4.00) |

| Violent crime perpetration | ||||||||

| No mental disorder | 23,667 | 3,944,843 | 6.00 | 1 | 3245 | 3,847,589 | 0.84 | 1 |

| Any mental disorder | 7818 | 573,842 | 13.62 | 2.58 (2.52–2.64) | 2202 | 608,590 | 3.62 | 5.48 (5.19–5.79) |

| 1. Substance use disorders | 3448 | 155,752 | 22.14 | 4.19 (4.04–4.35) | 949 | 142,725 | 6.65 | 8.80 (8.19–9.46) |

| 2. Schizophrenia-spectrum | 708 | 35,932 | 19.70 | 3.75 (3.48–4.04) | 273 | 37,672 | 7.25 | 8.32 (7.36–9.40) |

| 3. Mood disorders | 611 | 56,464 | 10.82 | 2.07 (1.91–2.24) | 405 | 135,840 | 2.98 | 3.62 (3.27–4.02) |

| 4. Neurotic disorders | 1994 | 147,067 | 13.56 | 2.43 (2.32–2.54) | 1156 | 282,739 | 4.09 | 5.14 (4.81–5.49) |

| 5. Eating disorders | 39 | 7361 | 5.30 | 0.84 (0.61–1.14) | 117 | 73,227 | 1.60 | 1.59 (1.32–1.91) |

| 6. Personality disorder | 519 | 22,260 | 23.31 | 4.47 (4.10–4.88) | 495 | 78,783 | 6.28 | 8.52 (7.75–9.37) |

NB. Diagnostic categories are not mutually exclusive/hierarchical.

NB. Any mental disorder includes all ICD-10 code F diagnoses (i.e., mental and behavioural disorders) and is not limited to the specific disorder groups presented.

NB. Victimisation: Overall estimate of men versus women (ref = 1): 2.15 (2.11, 2.19), adjusted for age and calendar time.

NB. Perpetration: Overall estimate of men versus women (ref = 1): 5.66 (5.50, 5.83), adjusted for age and calendar time.

NB. Victimisation or perpetration: Overall estimate of men versus women (ref = 1): 2.88 (2.84, 2.93), adjusted for age and calendar time.

Specific mental disorders

Across mental disorder subgroups, the incidence rate ratios were higher for women than men, but for some specific disorders the direction of association was lower than one or non-significant. For men, the ratio for violent victimisation ranged from 1.26 (0.99–1.59) for those with eating disorders to 2.47 (2.38–2.57) for those with substance use disorders. Incidence rate ratios for violence perpetration for men ranged from 0.84 (0.61–1.14) for those with eating disorders to 4.47 (4.10–4.88) for those men with onset of personality disorder. Amongst women, the post-onset incidence rate ratios for violent victimisation ranged from 1.39 (1.26–1.54) for eating disorders to 3.85 (3.67–4.05) for substance use disorders. When violence perpetration by women was considered, the incidence rate ratios varied from 1.59 (1.32–1.91) for eating disorders to 8.80 (8.19–9.46) for substance use disorders.

Discussion

In this large national register-based longitudinal study of the absolute and relative risks of police-recorded violence victimisation and perpetration following onset of mental illness in young adults, a complex pattern of associations was uncovered. While both types of violent experiences occurred more frequently amongst persons with mental illness, whether risk of one was greater than the other depended on a range of factors, including sex and diagnosis. While there was no consistent pattern of findings indicating that people with mental illness were more likely to experience violent victimisation than to perpetrate violence, this was true for the absolute risks experienced by women following onset of mental illness. Men and women diagnosed with personality disorders, substance use disorders, and schizophrenia-spectrum disorders were at highest risk of violence victimisation and perpetration. Although most young adults with onset of mental illness experienced neither victimisation nor perpetration, even up to five years after onset, the risks of these serious adverse outcomes are significant and justify efforts to better understand the underlying drivers of risk to inform more effective preventative strategies.

Sex differences

Consistent with previous research on violence perpetration,9,19 absolute risks tended to be higher for men with mental illness (Tables 1 and 2 and Figs. 1 and 2; e.g., 2.31% of men by 12 months compared to 0.50% of women), while relative risks indicated a stronger relationship between mental illness and violence risk for women (Table 3; e.g., IRR for perpetration 5.48, 5.19–5.79 for women compared to 2.58, 2.52–2.64 for men). The current study identified a similar pattern for victimisation risk (i.e., absolute risks higher for men, relative risks greater for women), although the differences between men and women were less pronounced.

Fewer previous studies have examined the influence of sex on associations between mental illness and victimisation, with meta-analysis showing no significant association between victimisation and sex in a sample of adults with psychotic disorders.20 The modifying influence of sex on associations between mental illness and risks of violent outcomes is complex, and likely to depends on a range of factors, including offence type and diagnosis. However, the striking magnitude of relative risks for violence perpetration for women has been noted before and thought to relate to the very low rates of perpetration by women in the general population.19 It seems that the protective factors keeping female rates of violence perpetration so low are undermined by the onset of mental illness and its associated adversities.

Comparison with other studies

Only three previous studies have examined in the same cohort the dual outcomes of violent victimisation and perpetration amongst individuals with and without mental illness.5 One Ethiopian study relied on self-reported experiences of violence and found higher rates of victimisation than perpetration6 while the other two European studies utilised official records and found the opposite.7,8 While violence perpetration data was obtained from justice records in these latter studies, violent victimisation status was based on whether these individuals had presented to secondary healthcare services8 or were admitted to hospital for their injuries,7 limiting the direct comparability of risks.

The current study's findings, along with those from the three previous comparable studies, suggest that risk of one type of violence experience is not consistently greater than the other and that a range of factors are likely to be important in determining the relative magnitude of absolute and relative risks for victimisation and perpetration among young adults with a mental illness. For example, after one year and five years, men with mental illness showed higher absolute risks of perpetration than victimisation whereas women with mental illness showed higher rates of victimisation than perpetration. However, in addition to factors such as sex and diagnosis, the nature of the data on which research relies is likely to be key, with official records being more likely to underestimate victimisation risk to a greater extent than risk of perpetration, compared to self-report.

Previous research confirms an overlap in the risk factors identified for violent victimisation and perpetration amongst those with mental illness (e.g., socioeconomic disadvantage, co-morbid substance use problems, early life trauma/abuse; 21,22). The overlap of individuals at elevated risk of both outcomes amongst those with mental illness is also well recognised,23 with experiences of both victimisation and perpetration actually being more common than experience of only one of the two outcomes.24 Thus, it is not surprising that onset of mental illness might be associated with an increased risk of both outcomes, along with a range of other adverse events.7 Further research is needed to examine the nuances of the overlap between victimisation and perpetration in relation to young adults with mental illness.

While the patterns of violence risk in the current study were largely consistent across diagnostic groups, the frequency of comorbidity or overlap between disorders is likely to have been substantial.17 However, risks were particularly high for those with personality disorders, substance use disorders and schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. The latter diagnostic group is more often the focus of research and clinical service or practice developments in relation to violence, while those with primary personality and/or substance use disorders have tended to be neglected in clinical research and health service provision. Interventions demonstrated to reduce risk of violence victimisation and/or perpetration following onset of psychiatric illnesses remain lacking.25,26 In particular, violent victimisation is rarely considered a key outcome of interest in studies of mental health interventions. However, calls for this to be addressed have been increasing27,28 and some promising progress has been made, including in relation to reducing risk of domestic and family violence for women with mental illness29,30 and with regard to increasing the ability of mental health clinicians to recognise victimisation risk.31 Besides interventions embedded within mental healthcare services and the criminal justice system, adequate housing and social supports along with efforts to combat stigma and its consequence will play key roles in any successful violence prevention strategy aimed at people with mental illness.32

Strengths and limitations

Beyond the key strength of including data on police-recorded incidents of both violent victimisation and perpetration for individuals with and without mental illness, its other strengths include examination of a large longitudinal population-based cohort of young adults, as well as utilisation of interlinked national registers to minimise selection, attrition, and information biases. In addition, the full spectrum of psychiatric diagnoses was examined, in both men and women separately, and absolute and relative risks were also both estimated. The main advantage of estimating absolute risks is that they indicate the probability that a person will develop the outcome of interest. For example, the current study indicates that approximately 6 out of 100 males first diagnosed with schizophrenia-spectrum disorder will become a violent crime victim within five years (Table 2). Finally, data on onset of mental illness were importantly derived from psychiatric and somatic hospital inpatient and outpatient contacts.

There are, however, several limitations that must be considered, particularly those arising from reliance on officially recorded health and justice data. Official police records of violent crime victimisation and perpetration exclude incidents not reported to police, and the factors influencing whether or not a violent crime was reported are likely to vary in relation to the sex, socioeconomic circumstances, and cultural context of the individuals directly involved, as well as between communities and over time. There is evidence, for example, that rates of crime reporting vary between countries and are typically higher in more affluent places.33 Reporting of violent victimisation or recording of violence perpetration is also likely to vary between individuals with and without mental illness, with the former being perhaps more reluctant or less able to report victimisation experiences to the police,34 including as a result of stigma, lack of support, and social isolation. Persons with mental illness who report violent victimisation may be less likely to be believed by the authorities or to be perceived as victims by adjudicators. Violence perpetration by individuals with mental illness, on the other hand, may be more likely to be observed and reported, including by health service staff. Another limitation regarding police recording of violence perpetration is our reliance on the date of conviction rather than the date of the crime, giving rise to the possibility that in some cases a person may have been the perpetrator of a violent crime prior to a diagnosis but with the conviction only recorded subsequently. Finally, in the current study we focused on first incidents of violent crime following onset of mental illness and grouped all types and severity of violence into a single category. Future research could examine the occurrence of repeated violent events and the extent to which there are any differences in patterns of risk for specific types of violent offence.

Reliance on secondary care electronic health records also has inherent limitations regarding both the underestimation of mental disorders (i.e., due to exclusion of those presenting to primary care only and those who do not present to any health services) and diagnostic accuracy. Many of the diagnostic categories (e.g., schizophrenia, dementia, affective disorders, depressive disorder, childhood disorders) that we examined have, however, been successfully validated.35,36 It should be noted that all recorded diagnoses were made by treating clinicians, often based on a period of clinical observation rather than a single clinical or research interview, thus enabling results to be more readily generalised to routine clinical settings. It is also important to note that illness onset may be more closely related to first health service contact for some disorders (e.g., schizophrenia-spectrum) than others (e.g., personality disorders). It is therefore possible that an individual's risk of violence, victimisation or perpetration, may have increased prior to actual contact, as the true onset of mental health problems may have been much earlier. Additionally, mental disorder categories characterised by lower rates of outpatient, emergency department, or inpatient contact (e.g., anxiety disorders) are likely to be under-recorded. Consequently, the results for those diagnostic groups will reflect the risk of victimisation and perpetration for those with more severe disorders, co-morbid problems, or other adversity necessitating mental health care beyond the level of primary care.

Another methodological factor to consider is use of the discharge date as the start of the follow-up period. Using the end date of health service contact for an inpatient stay avoids the potential for bias arising from the reduced likelihood of formally recorded victimisation or perpetration occurring during a period of hospitalisation. However, taking the same approach for outpatient health service contact, particularly if lengthy, means that instances of violence occurring after commencement but before completion of the outpatient treatment are not considered post-illness-onset outcome events. The effect of the latter would be to underestimate the strength of association between mental illness and incidence of violent outcomes.

Finally, the follow-up period focused on people between the ages of 15 and a maximum of 31 years, meaning that some individuals would not have been followed up long enough to have developed mental illnesses, particularly those known to have later ages of onset (e.g., bipolar disorder).

Conclusions

While statements made about individuals with mental illness being at greater risk of violent victimisation than perpetration are commonly made to counter prevailing stigmatising perceptions, the evidence to support such general statements is lacking. Overall, men with a mental disorder had higher absolute risks of victimisation and perpetration than women. Women with mental illness faced higher absolute risks of officially reported violent victimisation compared to perpetration, and vice versa for men. This work presents strong evidence that the risks for both victimisation and perpetration are elevated for young adults with mental illness, though violence risks are complex. Evidence-informed and tested strategies to reduce these risks are urgently needed. Strategies developed to prevent violent victimisation and violence perpetration may need to be tailored for persons with mental disorders. There may also be a benefit in taking a sex-specific approach to prevention in this group.

Contributors

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

TML had full access to all the data in the study, and KD had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. KD, TML, RTW and EA contributed substantially to the study design and interpretation of findings. KD and CM undertook the literature search. KD wrote all the drafts and the final version of the paper. All authors made important intellectual contributions to the preparation of the report and all authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant awarded to the first author. Dr Dean is also funded by Justice Health & Forensic Mental Health Network, NSW, Australia, and the University of New South Wales, Australia. Drs Agerbo and Laursen are supported financially by the Stanley Medical Research Institute and The Lundbeck Foundation Initiative for Integrative Psychiatric Research, iPSYCH. Dr Webb is supported financially by the European Research Council. The funders/sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100781.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Whiting D., Lichtenstein P., Fazel S. Violence and mental disorders: a structured review of associations by individual diagnoses, risk factors, and risk assessment. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(2):150–161. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30262-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dean K., Laursen T.M., Pedersen C.B., Webb R.T., Mortensen P.B., Agerbo E. Risk of being subjected to crime, including violent crime, after onset of mental illness: a Danish national registry study using police data. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(7):689–696. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thornicroft G. People with severe mental illness as the perpetrators and victims of violence: time for a new public health approach. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(2):e72–e73. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choe J.Y., Teplin L.A., Abram K.M. Perpetration of violence, violent victimization, and severe mental illness: balancing public health concerns. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(2):153–164. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.2.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marr C., Webb R.T., Yee N., Dean K. A systematic review of interpersonal violence perpetration and victimization risk examined within single study cohorts, including in relation to mental illness. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2023 doi: 10.1177/15248380221145732. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36737885/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsigebrhan R., Shibre T., Medhin G., Fekadu A., Hanlon C. Violence and violent victimization in people with severe mental illness in a rural low-income country setting: a comparative cross-sectional community study. Schizophr Res. 2014;152(1):275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walter F., Carr M.J., Mok P.L., et al. Multiple adverse outcomes following first discharge from inpatient psychiatric care: a national cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):582–589. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30180-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sariaslan A., Arseneault L., Larsson H., Lichtenstein P., Fazel S. Risk of subjection to violence and perpetration of violence in persons with psychiatric disorders in Sweden. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(4):359–367. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fazel S., Gulati G., Linsell L., Geddes J.R., Grann M. Schizophrenia and violence: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedersen C.B. The Danish Civil registration system. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7):22–25. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen M.F., Greve V., Hoyer G., Spencer M. 3rd ed. DJOF Publishing; Copenhagen: 2006. The principal Danish criminal acts. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mors O., Perto G.P., Mortensen P.B. The Danish psychiatric central research register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7):54–57. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynge E., Sandegaard J.L., Rebolj M. The Danish national patient register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7):30–33. doi: 10.1177/1403494811401482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO . Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines; Geneva: 1992. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO . 1982. Klassification af sygdomme (8th revision) Copenhagen. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen C.B., Mors O., Bertelsen A., et al. A comprehensive nationwide study of the incidence rate and lifetime risk for treated mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):573–581. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Plana-Ripoll O., Pedersen C.B., Holtz Y., et al. Exploring comorbidity within mental disorders among a Danish national population. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(3):259–270. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen P.K., Perme M.P., van Houwelingen H.C., et al. Analysis of time-to-event for observational studies: guidance to the use of intensity models. Stat Med. 2021;40(1):185–211. doi: 10.1002/sim.8757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens H., Laursen T.M., Mortensen P.B., Agerbo E., Dean K. Post-illness-onset risk of offending across the full spectrum of psychiatric disorders. Psychol Med. 2015;45(11):2447–2457. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Vries B., van Busschbach J.T., van der Stouwe E.C.D., et al. Prevalence rate and risk factors of victimization in adult patients with a psychotic disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2018;45(1):114–126. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witt K., Van Dorn R., Fazel S. Risk factors for violence in psychosis: systematic review and meta-regression analysis of 110 studies. PLoS One. 2013;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Mooij L.D., Kikkert M., Lommerse N.M., et al. Victimisation in adults with severe mental illness: prevalence and risk factors. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(6):515–522. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.143370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson K.L., Desmarais S.L., Tueller S.J., Grimm K.J., Swartz M.S., Van Dorn R.A. A longitudinal analysis of the overlap between violence and victimization among adults with mental illnesses. Psychiatry Res. 2016;246:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson K.L., Desmarais S.L., Van Dorn R.A., Grimm K.J. A typology of community violence perpetration and victimization among adults with mental illnesses. J Interpers Violence. 2015;30(3):522–540. doi: 10.1177/0886260514535102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolf A., Whiting D., Fazel S. Violence prevention in psychiatry: an umbrella review of interventions in general and forensic psychiatry. J Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2017;28(5):659–673. doi: 10.1080/14789949.2017.1284886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevens H., Agerbo E., Dean K., Mortensen P.B., Nordentoft M. Reduction of crime in first-onset psychosis: a secondary analysis of the OPUS randomized trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(5):e439–e444. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howard L.M. Routine enquiry about violence and abuse is needed for all mental health patients. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210(4):298. doi: 10.1192/bjp.210.4.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fazel S., Sariaslan A. Victimization in people with severe mental health problems: the need to improve research quality, risk stratification and preventive measures. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):437–438. doi: 10.1002/wps.20908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iverson K.M., Gradus J.L., Resick P.A., Suvak M.K., Smith K.F., Monson C.M. Cognitive–behavioral therapy for PTSD and depression symptoms reduces risk for future intimate partner violence among interpersonal trauma survivors. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(2):193. doi: 10.1037/a0022512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruijne R., Mulder C., Zarchev M., et al. Detection of domestic violence and abuse by community mental health teams using the brave intervention: a multicenter, cluster randomized controlled trial. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(15-16):Np14310–NP14336. doi: 10.1177/08862605211004177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albers W.M.M., Nijssen Y.A.M., Roeg D.P.K., Bongers I.M.B., van Weeghel J. Development of an intervention aimed at increasing awareness and acknowledgement of victimisation and its consequences among people with severe mental illness. Community Ment Health J. 2021;57(7):1375–1386. doi: 10.1007/s10597-021-00776-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swartz M.S., Bhattacharya S. Victimization of persons with severe mental illness: a pressing global health problem. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):26–27. doi: 10.1002/wps.20393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Dijk J., van Kesteren J., Smit P. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute; The Hague: 2008. Criminal victimisation in international perspective: key findings from the 2004-2005 ICVS and EU ICS; p. 257. [Google Scholar]

- 34.MIND . MIND; 2007. Another assault: mind's campaign for equal access to justice for people with mental health problems. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kessing L. Validity of diagnoses and other clinical register data in patients with affective disorder. Eur Psychiatry. 1998;13(8):392–398. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(99)80685-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uggerby P., Østergaard S.D., Røge R., Correll C.U., Nielsen J. The validity of the schizophrenia diagnosis in the Danish psychiatric central research register is good. Dan Med J. 2013;60(2):A4578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.