Abstract

Objective:

This study isolated the chemical compounds and evaluated the cytotoxic activity of the crude hexane extract of Cleome rutidospermae herb (CRH).

Methods:

The isolate was purified using silica gel, column chromatography, and preparative thin layer chromatography (PTLC). Furthermore, the structure of the compounds was identified by spectroscopic methods using 1D, 2D NMR, and mass spectrometry. The cytotoxic activity of CRH at a concentration of 20 ug/mL was also tested against MCF-7, A549, KB, KB-VIN, and MDA-MB-231 cancer cells using the sulforhodamine B (SRB) method.

Results:

The CRH contained compounds of unsaturated fatty acid, saturated fatty acid, lipid, glycerol, ω-3 fatty acid, and cholesterol. Two compounds were obtained from the plant, and their structures were identified as (1) Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol (STML) and (2) 1,2-Benzene dicarboxylic acid, 1,2-bis (2-Ethylhexyl) esters (DEHP). These compounds were reported in this plant for the first time. In comparison, CRH had % growth inhibition in the proliferation of MCF-7 cells up to 28.1%, with cancer cells A549, KB, KB-VIN, and MDA-MB-231 by >50% Compared to the negative DMSO of 0.20%, while the positive control could inhibit the growth of all cancer cells (100%).

Conclusion:

Our findings suggested that crude herb from the plant CRH was the potential for breast cancer treatment.

Key Words: Cleome rutidospermae, Stigmasta-5, 22-dien-3-ol, Bis(2-Ethylhexyl) esters (DEHP), Cytotoxic

Introduction

Medicinal plants have been proven to be an alternative approach for treating various health conditions. Although synthetic drugs have taken traditional healing to some degree, the revival and attention of herbal medicines are very important (Mirzaeian et al., 2021). Medicinal plants are affordable and eco-friendly, with fewer side effects than synthetic drugs. In fact, among the modern medicines currently in use, approximately 40% come from nature, while 60% of anticancer and 75% of infectious diseases drugs are natural or derivatives. Furthermore, some of these plants have attracted scientists’ interest in investigating cancer treatment. Additionally, phytoconstituents have been essential in developing clinically valuable prospects for treating neoplasms (Gupta et al., 2021).

Cleome rutidospermae is an annual herbaceous plant known as the Fringed Spider Flower. Besides being a weed, it is also an important medicinal plant widely found in the tropics. Furthermore, it is ayurvedically, Greek, and local Kabiraj used to manufacture bread. Its roots or seeds are used as a stimulant, antiscorbutic, anthelminthic, rubefacient, vesicant, and carminative. The plant is also an analgesic, antipyretic, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-seizure, anti-diabetic, and diuretic, with wound healing and laxative activity (Ghosh et al., 2019). Its herb contains water (81.0 g), energy (239 kJ/57 kcal), protein (5.5 g), fat (0.9 g), carbohydrate (10.1 g), Fiber (1.7 g), Ca (454 mg), Mg (38 mg), P (59 mg), and Fe (2.7 mg) per 100 g of edible portion, tannins, lipids, amino acids, flavonoids, cardiac glycosides, alkaloids, steroids, saponins, terpenoids, polyphenols, and phlorotannin pentose and reducing sugars (Ghosh et al., 2019).

Natural ingredients are considered an essential source of discovery for anticancer treatments, and many cytotoxic drugs in clinics and hospitals today are derived from plants and other natural sources (Sammar et al., 2019). Phytochemicals from plant extracts are included in important sources of natural products that have shown excellent cytotoxic activity. However, plants of different origins show diverse chemical compositions and bioactivity. Therefore, discovering new plant-based anticancer agents from other parts is always challenging (Khan et al., 2022).

In this study, two compounds were isolated, namely (1) Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol (STML) and (2) 1,2-Benzene dicarboxylic acid, 1,2-bis (2-Ethylhexyl) esters (DEHP) using 1D, 2D NMR, and mass spectrometry. Meanwhile, the activity of CRH was tested against several cancer cell pathways using the SRB method. These compounds have never been reported or isolated from this plant.

Materials and Methods

Plant material

The CRH was obtained from Makassar City, Tamalanrea Sub-District, South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia. The plant identification was conducted at the Botanical Laboratory in the Department of Biology, Mathematics, and Natural Sciences, Universitas Negeri Makassar. Furthermore, the plant samples were washed with running water, wet sorted, cut into small pieces, dried in a 40-50 oC oven for three days, dry sorted, and stored in containers tightly sealed with silica gel.

Extraction and isolation

The extraction of Cleome rutidospermae herb (2 kg) with hexane solvent (1:10 ml) was conducted using the maceration method at room temperature for three days (Tiwari et al., 2011; Yasir et al., 2022). It was stirred once daily and filtered using a vacuum pump with whatmanTM no 42-filter paper. Subsequently, the liquid extract was evaporated to obtain a 35 g viscous extract using rotavapor and a water bath. The extract was partitioned using petroleum ether and methanol (1:1) three times as much as 250 ml. The petroleum ether and methanol extracts obtained were 29.2 g and 5.74 g, respectively.

The methanol extract was partitioned with hexane and methanol-water comparison (1:1) 3 times as much as 300 ml to obtain methanol-water and hexane partitioned extract of 0.4753 g and 5.3247 g, respectively. The hexane partitioned extract was isolated using a normal phase (NP) silica chromatography column, with hexane and ethyl acetate mobile phase (3:1) 3 times as much as 300 ml. The partitioned using 200 ml ethyl acetate and 200 ml methanol to give 1-5 sub-fraction, sub-fraction (2) 0.0514 g washed with hexane, and insoluble hexane (b) 0.0230 g. Subsequently, the soluble hexane (a) 0.0284 g was isolated using an NP silica chromatography column with hexane mobile phase and ethyl acetate (4:1). This aims to obtain (1) STML 0.0202 g amorphous powder. Sub-fraction (3) 0.0644 g was washed with acetone to obtain soluble and insoluble acetone of (b) 0.0086 g and (a) 0.0438 g, respectively. The insoluble acetone was isolated using PTLC, NP silica with hexane mobile phase, and ethyl acetate (5:1) to obtain (2) DEHP 0.0335 g yellowish oil compound.

Cytotoxicity activity

The samples of CRH weighed as much as 1 mg with a 20 μg/ml concentration. The test used five lines of human tumor cells, namely A549 (lung carcinoma), MDA-MB-231 (estrogen receptor-negative, progesterone receptor-negative, and HER2-negative breast cancer), MCF-7 (estrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer), KB (isolated initially from epidermoid carcinoma of the nasopharynx), and KB-VIN (vincristine (VIN)-resistant KB subline showing MDR phenotype by overexpressing P-gp). All the cell lines were obtained from Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center (UNC-CH) or ATCC. Furthermore, 4,000−12,000 cells were seeded in the microtiter plate of 96 wells, with each test sample in DMSO (negative control). Subsequently, 10% trichloroacetic acid was added after 72 hours, followed by the 0.04% sulforhodamine B method. DMSO substances with 0.1% v/v concentration showed no inhibitory effect on cancer cells (Rahim et al., 2018). The growth (%) was calculated on a plate-by-plate basis for tested wells compared to the control. It was also articulated using the following formula, Average absorbance of test wells × 100 / Average absorbance of control wells (Houghton et al., 2007; Lamkanfi et al., 2008).

Results

Isolation compound

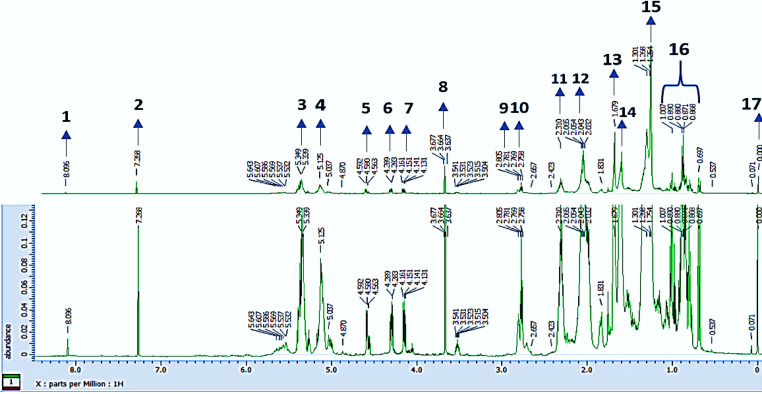

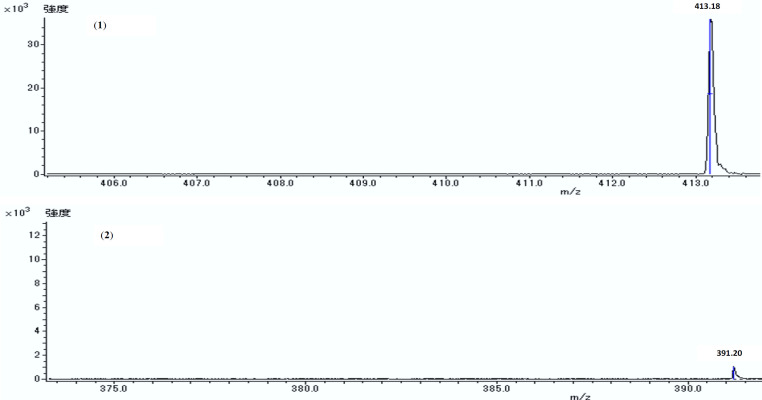

The CRH was checked profile using 1H NMR (Figure 1) and contained unsaturated fatty acids, saturated fatty acids, lipids, glycerol, ω-3 fatty acids, cholesterol, and position of functional groups in Table 1. It was partitioned using petroleum ether, and MeOH with the ratio of (1:1). The soluble layer of MeOH was evaporated and further partitioned into a combination of hexane, MeOH-H2O (1:1) as much as 300 ml. A combination of various chromatography techniques was also used to separate the hexane layer from obtaining the following compounds (1) STML and (2) DEHP with reported 1D spectroscopic, 2D NMR, and mass spectrometry data. The STML (1) is a white amorphous powder and steroid group compound based on ESI+ MS m/z 413.18 [M + H]+ spectrometry mass data with the molecular formula C29H48O Figure 3. According to the 1H NMR spectroscopy in Table 2 showing the presence of 5 methyl group signals, the proton methine, which appeared at position δH 5.35 (1H, br d, J=5.50 Hz), δH 5.17 (1H, dd, J=8.24 Hz), δH 4.99 (1H, dd, J=8.70 Hz), and δH 3.52 (1H, septet) were emerging hydroxyl group signal positions or methylene protons. That is observed in carbon positions using DEPT 135 data. Furthermore, the 13C NMR showed the compound had 29 carbons, and DEPT 135 data indicated the function of carbon with 5 protons methyl and methylene group. Meanwhile, the carbon position of methine was δC 71.82, which binds to hydroxyl groups, δC 121.72, δC 138.32, δC 129.27 as a double bond, and carbon without protons at position δC 140.75, δC 36.51, and δC 42.21.

Figure 1.

1H NMR Spectra of Cleome Rutidospermae Herb Hexane Extract (CRH). Assignments (A) 1 to 17 are reported in table 1 (400 MHz, CDCl3). (A) = Major signal; (B) = (A) An expanded

Table 1.

1H NMR Spectra Signal from Cleome Rutidospermae Herb Hexane Extract (CRH) Assignments (A) 1 to 17

| Peak (A) | δ (ppm) | Multiplicity | Compound/proton | References δ (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.1 | s | Trans olefinic | 8.1, d (Hasan et al., 2007) |

| 2 | 7.24 | s | Chloroform (solvent)/(CHCl3) | 7.26 (de Combarieu et al., 2015; Gottlieb et al., 1997) |

| 3 | 5.37-5.30 | m | All unsaturated fatty acids/(CH = CH) Methylene protons/(CH2) |

5.36 (de Combarieu et al., 2015) 5.37 – 5.30, m 2H (Shirey et al., 2018) |

| 4 | 5.12-5.07 | m | Glycerol (triacylglycerols)/CHOCOR, Glycerol (sn-1,2-diacylglycerols)/CHOCOR Methynic (CH), Aliphatic/(CH2) |

5.27; 5.08 (de Combarieu et al., 2015) 5.12; 5.07 (Que et al., 2000; Sivakumar et al., 2013) |

| 5 | 4.57 | d, J=6.9 Hz | Glycerol (all acylglycerols)/CH2OCOR | 4.30 (de Combarieu et al., 2015) |

| 6 | 4.28 | dd, J=11.9, 4.3 Hz | Vinyl protons Glycerol (all acylglycerols)/CH2OCOR |

4.28 (d, J = 3.2 Hz) (Breen et al., 2005) 4.15 (de Combarieu et al., 2015) |

| 7 | 4.13 | q, J=6.0 Hz | Glycerol (sn-1,3-diacylglycerols)/CHOH Methylene group/(CH2O) |

4.07 (de Combarieu et al., 2015) 4.13; q, J = 6 Hz (Reheim & Tolba, 2016) |

| 8 | 3.64 | s | Fatty alcohols/(CH2OH) Polyethylene glycol/(OCH2CH2) |

3.64 (de Combarieu et al., 2015) 3.64, s (Fang et al., 2014) |

| 9 | 2.78 | t | Linoleyl and linolenyl/(CH=CHCH2CH = CH) Methylene/(CH2) |

2.81 (de Combarieu et al., 2015) 2.78, t (Flores et al., 2013) |

| 10 | 2.74-2.79 | t, m | ω-3 fatty acids, Ethylene (CH2CH2) |

2.74, t; 2.80−2.73, m (Li et al., 2018; Vicente et al., 2015) |

| 11 | 2.25 | m | Methylenic/(CH2) | 2.25 (Durand et al., 2020) |

| 12 | 1.94-2.09 | m | Allylic (CHCHCH2) | 1.94–2.15 (Hwang et al., 2017) |

| 13 | 1.65 | s | All acyl chains/(CH2CH2COOH) Methylene/(CH2) |

1.64 (de Combarieu et al., 2015) 1.65 (Tshilanda et al., 2014) |

| 14 | 1.57-1.58 | s-m | Lipids/(CH2CCO) | 1.58 (Righi et al., 2014) |

| 15 | 1.2-1.4 | m | Saturated fatty acids/(CH)n | 1.2-1.4, m (Knothe & Kenar, 2004) |

| 16 | 1.83-0.66 | m | Cholesterol and methyl groups/(CH3) | 0.66; 1.83 (Park et al., 2011; J. Zhao et al., 2011) |

| 17 | 0 | s | Tetramethylsilane/(TMS) | 0.02, s (Hoffman, 2006) |

Figure 3.

Data Mass Spectra of (1) Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol (STML) ESI+ m/z 413.18 [M + H]+ and (2) 1,2-Benzene dicarboxylic acid, 1,2-bis (2-Ethylhexyl) ester (DEHP) m/z 391.20 [M + H]+ using Electrospray Ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry

Table 2.

Data 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and DEPT 135 of (1) Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol (STML) and (2) 1,2-Benzene dicarboxylic acid, 1,2-bis (2-Ethylhexyl) ester (DEHP)

| STML (1) | DEHP (2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | DEPT | 13C (ppm) | 1H (ppm) | Position | DEPT | 13C (ppm) | 1H (ppm) |

| 1 | CH2 | 37.25 | br d, 5.35 (1H) J=5.50 Hz | 1 | C | 132.53 | septet, 3.51 (1H) |

| 2 | CH2 | 31.66 | dd, 5.17 (1H) J=8,24 Hz | 2 | C | 132.53 | br d, 5.33 (1H) |

| 3 | CH | 71.82 | dd, 4.99 (1H) J=8,70 Hz | 3 | CH | 128.88 | dd, 5.22 (1H) |

| 4 | CH2 | 42.30 | septet, 3.52 (1H) | 4 | CH | 130.95 | dd, 5.16 (1H) |

| 5 | C | 140.75 | m, 0.82 (3H) | 5 | CH | 130.95 | br q, 2.42 (1H) |

| 6 | CH | 121.72 | m, 0.82 (3H) | 6 | CH | 128.88 | br s, 4.68 (2H) |

| 7 | CH2 | 25.41 | d, 1.02 (3H) J=7,79 | 7 | C | 167.83 | |

| 8 | CH | 31S.90 | s, 1.03 (3H) | 8 | CH2 | 68.23 | |

| 9 | CH | 50.15 | m, 0.80 (3H) | 9 | CH | 38.8 | |

| 10 | C | 36.51 | m, 0.68 (3H) | 10 | CH2 | 23.81 | |

| 11 | CH2 | 21.09 | 11 | CH3 | 11.04 | ||

| 12 | CH2 | 39.77 | 12 | CH2 | 30.43 | ||

| 13 | C | 42.21 | 13 | CH2 | 29 | ||

| 14 | CH | 56.87 | 14 | CH2 | 23.06 | ||

| 15 | CH2 | 24.37 | 15 | CH3 | 14.13 | ||

| 16 | CH2 | 28.93 | |||||

| 17 | CH | 55.94 | |||||

| 18 | CH3 | 12.26 | |||||

| 19 | CH3 | 19.41 | |||||

| 20 | CH | 40.51 | |||||

| 21 | CH3 | 21.26 | |||||

| 22 | CH | 138.32 | |||||

| 23 | CH | 129.27 | |||||

| 24 | CH | 51.24 | |||||

| 25 | CH2 | 39.68 | |||||

| 27 | CH | 56.76 | |||||

| 28 | CH3 | 18.98 | |||||

| 26 | CH3 | 12.05 | |||||

| 29 | CH3 | 11.87 | |||||

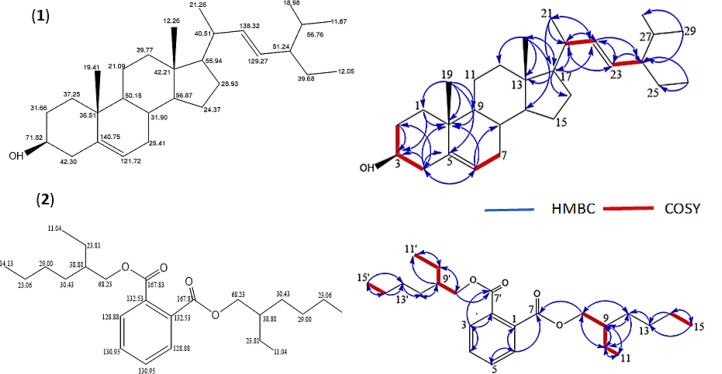

NMR’s 2-dimensional data, including HMQC and HMBC, showed the correlation between hydrogen and carbon in Figure 2, blue line, i.e., methyl proton δH 1.02 (3H, d, J = 7.79 Hz) correlated with carbon δC 36.51 (C-10), δC 37.25 (C-1), δC 50.15 (C-15 9), and δC 140.75 (C-5). Proton methyl δH 1.03 (3H, s) correlated with δC 40.51 (C-20), δC 55.94 (C-17), and δC 138.32 (C-22). Furthermore, δH 0.68 (3H, m) correlated with δC 55.94 (C-17), δC 42.21 (C-13), and δC 39.77 (C-12), while δH 0.80, δC 11.87 (3H, m) correlated with carbon δC 18.98 (C-28) and δC 51.24 (C-24). In addition, δH 0.80, δC 12.05 (3H, m) correlated with δC 39.68 (C-25) and δC 51.24 (C-24).

Figure 2.

Structure of Compound (1) Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol (STML) and (2) 1,2-Benzene dicarboxylic acid, 1,2-bis (2-Ethylhexyl) ester (DEHP)

The correlation data with protons using 1H-1H Cosy in figure 2, the thick red line showed proton H3 δH 3.52 (1H, septet) correlated with H2 and H4, H6 δH 5.35 (1H, br d, J=5.50 Hz) with H7, H22 δH 5.17 (1H, dd, J=8.24 Hz) correlated with H20 and H23 δH 4.99 (1H, dd, J=8.70 Hz) and proton H24. Furthermore, 1D and 2D NMR data indicated that this compound first reported in the plant was steroid (1) STML.

The DEHP (2) is a yellow oil and phthalate group compound. According to spectrometry, mass data gave a molecular weight of ESI+ MS m/z 391.20 [M + H]+ with the C24H38O4 formula Figure 3. The same compound was previously isolated from Aloe vera plants and discovered to have antileukemic as well as antimutagenic effects (Lee et al., 2010). The 1H NMR spectroscopy data in Table 2 showed the presence of 4 methyl group signals, ten methylene protons, and four methines observed at the proton position using DEPT 135 and HMBC data. According to 13C NMR , this compound has 24 carbons, while DEPT 135 data showed a carbon position with two methyl protons at δC 14.13 and δC 11.04, respectively, with methylene carbon at δC 23.06, δC 29.00, δC 39.43, δC 23.81. Each of the four methylene protons can be observed at HMQC and HMBC positions, and the 2 proton acetolactone position δC 68.23 (CH2OCO). Furthermore, the part of two carbon methines on the benzene framework is located at δC 128.88 and δC 130.95 and had a proton correlation with carbon at δC 130.95.

NMR’s 2-dimensional data including HMQC and HMBC showed the correlation between hydrogen and carbon at (Figure 2, blue line) i.e. 2 methyl protons δH 0.90 (3H, m) (C-15, C-15’) correlated with carbon δC 23.06 (C-14, C-14’), and δC 29.00 (C-13, C-13’). Also, 0.92 (3H, s) (C-11, C-11’) correlated with δC 23.81 (C-10, C-10’), and δC 38.80 (C-9, C-9’), δH 4.22 (2H, n) (C-8) with carbon carbonyl position δC 167.83 (C-7, C-7’). Furthermore, two protons methine δH 1.42 (1H, m) (C-9, C-9’) correlated with carbon (C-11, C-11’, C-10, C-10’, C-12, C-12’), methylene protons δH 1.32 (2H, m) (C-10, C-10’) correlated with carbon δC 38.80 (C-9, C-9’) and δC 23.81 (C-10, C-10’). δH 1.33 (2H, m) (C-13, C-13’) correlated with δC 30.41 (C-12, C-12’), and two methylene protons 1.30 (2H, m) (C-14, C-14’) correlated with δC 29.00 (C-13, C-13’) and δC 14.13 (C-15, C-15’). In addition, the proton methine H-3 δH 7.70 (1H, m) correlated with carbon δC 130.95 (C-4), δC 132.53 (C-2), and methine H-6 δH 7.70 (1H, m) with carbon δC 130.95 (C-5), and δC 132.53 (C-1).

The correlation data with protons using 1H-1H Cosy (Figure 2, thick red line) showed that proton methyl H-15, H-15’ δH 0.90 (3H, m) correlated with H-14, H-14’. Furthermore, H-11, H-11’ 0.92 (3H, s) correlated with H-10, H-10’ δH 1.32 (2H, m), while H-10, H-10’ correlated with methine H-9, H-9’ δH 1.42 (1H, m), and proton H-9, H-9’ with H-8, H-8’ δH 4.22 (2H, n).

Also, 1D and 2D NMR data indicated that this compound was a group of phthalate acid (2) DEHP and was first reported in this plant. In addition, it was isolated from Streptomyces bangladeshensis sp. Nov (Al-Bari et al., 2005), Aspergillus awamori (Lotfy et al., 2018), Aloe vera (Lee et al., 2010), Calotropis gigantea flower (Linn.) (Habib and Karim, 2009), Penicillium janthinellum (El-sayed et al., 2015), Acinetobacter sp. SN13 (Xu et al., 2017), and Benincasa hispida flower (Du et al., 2006).

Cytotoxic study

The preliminary test results of the CRH against cytotoxic cancer cells with 20 ug/mL showed that the % growth of MCF-7 cancer cells was 28.1%, A549 at 60.6%, and MDA-MB-231 at 68.4%. Furthermore, KB 58.1% and KB-VIN 86.3%, compared to the negative DMSO of 0.20%, control the growth of all cancer cells (100%).

The inhibition of these cells correlated with the contents which were successfully isolated in CRH, such as (1) STML that have inhibition of cancer cells >50% in ES2 and OV90 (Bae et al., 2020), SGC-7901, and MGC-803 (Zhao et al., 2021), as well as MCF-7 and NIH/3T3 cancer cells (Ayaz et al., 2019), which are chemopreventive (Ali et al., 2015). Also, (2) DEHP is effective as an anticancer. Therefore, as the compound concentrations increase, it inhibits the growth of cancer cells MCF-7, HEPG2, HELA, and HCT116 (Lotfy et al., 2018). This compound has potent cytotoxicity for MCF-7 cancer cells with IC50 of 6.941 μg/ml, moderate cytotoxicity for a HEPG2 cancer cell, and IC50 of 26.73 μg/ml for HELA cancer cell and showed no activity against colon carcinoma (HCT116) (Lotfy et al., 2018). Subsequently, it inhibits basal alveolar epithelial cells A-549 370 μg/mL (El-sayed et al., 2015).

Discussion

Many studies have been published regarding the anticancer potential of various plant extracts that can be good candidates for cancer drug discovery and development one example was the paclitaxel compound isolated from Taxus brevifolia for chemotherapy use (Liebmann et al., 1993). This STML (1) was first reported to be found in this species. However, this compound has been reported in several species of Cleome. STML, also known as stigmasterol once isolated from the Cleome gynandra (Ranjitha et al., 2009), Cleome paradoxa (Abdel-Monem, 2012), and Cleome viscosa. It was reported that STML compounds have the potential to be anticancer for new treatments in ovarian cancer (Bae et al., 2020), gastric cancer (Zhao et al., 2021), glycolysis in triple-negative breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231), and lung cancer (Dong et al., 2021). This compound has an anticancer mechanism through the induction of cell apoptosis, ROS production, and excess calcium in ES2 and OV90 cells. STML stimulates cell death by activating ER-mitochondria, suppressing cell migration and angiogenesis genes in human ovarian cancer cells (Bae et al., 2020). In addition, this compound also induces apoptosis and autophagy by inhibiting the Akt/mTOR pathway in gastric cancer cells (Zhao et al., 2021) and regulating retinoic acid associated with orphan C receptors (Dong et al., 2021).

The DEHP (2) compound is one of the compounds successfully isolated in this plant and first reported in this species. This compound has been reported to be found in Cleome serrata (Mcneil et al., 2012). In addition, compounds 2-ethyl-cyclohexane-2-ene-6-hydroxy-methylene-1- carboxylic acid and 3β-hydroxy-lup-20(29)-en-28-oic acid were also found in this plant (Rahman et al., 2008). DEHP (2) is known to have the potential to be an anticancer in the treatment of cancers such as breast cancer, liver cancer, cervical cancer, and colon cancer (Lotfy et al., 2018). Compound Bisphenol A combination with DEHP mainly induced the expression of HDAC6, inhibited tumor suppressor gene PTEN upregulated the expression of oncogene c-MYC. Eventually, it elevated the susceptibility to thyroid tumors (Zhang et al., 2022).

Author Contribution Statement

BY and AR conceptualized and designed the study; BY performed the experiments and collected the data; S, YS, KNG, and BY analyzed and interpreted the results; BY prepared the initial manuscript; AR and GM reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Medical, Pharmaceutical and Health Sciences, Kanazawa University, Kanazawa, 920-1192, Japan. And providing the essential laboratory facilities, we are grateful to Dr. Masuo Goto (The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, US) for the cytotoxicity assay.

Funding Statement

The authors would like to thank this research was supported scholarship by Kanazawa University Short-Term Exchange Program for Science and Technology (KUEST) 2019 – 2020 from Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO).

Statement of conflict Interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Abdel-Monem AR. A new alkaloid and a new diterpene from Cleome paradoxa B. Br. (Cleomaceae). Nat Prod Res. 2012;26:264–9. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2010.535156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Bari MAA, Bhuiyan MSA, Flores ME, et al. Streptomyces bangladeshensis sp ov isolated from soil, which produces bis-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:1973–77. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63516-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali H, Dixit S, Ali D, et al. Isolation and evaluation of anticancer efficacy of stigmasterol in a mouse model of DMBA-induced skin carcinoma. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:2793–800. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S83514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayaz M, Sadiq A, Wadood A, et al. Cytotoxicity and molecular docking studies on phytosterols isolated from Polygonum hydropiper L. Steroids. 2019;141:30–5. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae H, Song G, Lim W. Stigmasterol causes ovarian cancer cell apoptosis by inducing endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial dysfunction. Pharmaceutics. 2020:12. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12060488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen LE, Schepp NP, Tan CHE. Photochemical generation and 1H NMR detection of alkyl allene oxides in solution. Can J Chem. 2005;83:1347–51. [Google Scholar]

- de Combarieu E, Martinelli EM, Pace R, Sardone N. Metabolomics study of Saw palmetto extracts based on 1H NMR spectroscopy. Fitoterapia. 2015;102:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Chen C, Chen C, et al. Stigmasterol inhibits the progression of lung cancer by regulating retinoic acid-related orphan receptor C. Histol Histopathol. 2021;2021:18388. doi: 10.14670/HH-18-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Q, Shen L, Xiu L, Jerz G, Winterhalter P. Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate in the fruits of Benincasa hispida. Food Addit Contam. 2006;23:552–5. doi: 10.1080/02652030500539758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand PL, Grau E, Cramail H. Bio-based thermo-reversible aliphatic polycarbonate network. Molecules. 2020;25:1–12. doi: 10.3390/molecules25010074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-sayed O, Asker MMS, Shash SM, Hamed SR. Isolation, Structure elucidation and Biological Activity of Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate Produced by Penicillium janthinellum 62. Int J Chemtech Res. 2015;2015:58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Fang DL, Chen Y, Xu B, et al. Development of lipid-shell and polymer core nanoparticles with water-soluble salidroside for anticancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:3373–88. doi: 10.3390/ijms15033373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores AFC, Blanco RF, Souto AA, Malavolta JL, Flores DC. Synthesis of fatty trichloromethyl-β-diketones and new 1H-pyrazoles as unusual FAMEs and FAEEs. J Braz Chem Soc. 2013;24:2059–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh P, Chatterjee S, Das P, et al. Natural Habitat, Phytochemistry And Pharmacological Properties Of A Medicinal Weed-Cleome Rutidosperma Dc (Cleomaceae): A Comprehensive Review. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2019;10:1605. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb HE, Kotlyar V, Nudelman A. NMR Chemical Shifts of Common Laboratory Solvents as Trace Impurities. J Org Chem. 1997;62:7512–5. doi: 10.1021/jo971176v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta PK, Saraff M, Gahtori R, et al. Phytomedicines targeting cancer stem cells: Therapeutic opportunities and prospects for pharmaceutical development. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14:1–25. doi: 10.3390/ph14070676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib MR, Karim MR. Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Activity of Di-(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate and Anhydrosophoradiol-3-acetate Isolated from Calotropis gigantea (Linn ) Flower. Mycobiology. 2009;37:31. doi: 10.4489/MYCO.2009.37.1.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan A, Rasheed L, Malik A. Synthesis and characterization of variably halogenated chalcones and flavonols and their antifungal activity. Asian J Chem. 2007;19:937–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman RE. Standardization of chemical shifts of TMS and solvent signals in NMR solvents. Magn Reson Chem. 2006;44:606–16. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton P, Fang R, Techatanawat I, et al. The sulphorhodamine (SRB) assay and other approaches to testing plant extracts and derived compounds for activities related to reputed anticancer activity. Methods. 2007;42:377–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang HS, Winkler-Moser JK, Liu SX. Reliability of 1H NMR Analysis for Assessment of Lipid Oxidation at Frying Temperatures. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2017;94:257–70. [Google Scholar]

- Khan M, Khan M, Adil SF, Alkhathlan HZ. Screening of potential cytotoxic activities of some medicinal plants of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2022;29:1801–7. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knothe G, Kenar JA. Determination of the fatty acid profile by 1H-NMR spectroscopy. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2004;106:88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD, van Damme P, et al. Targeted peptidecentric proteomics reveals caspase-7 as a substrate of the caspase-1 inflammasomes. Mol Cell Proteom. 2008;7:2350–63. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800132-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KH, Kim JH, Lim DS, Kim CH. Anti-leukaemic and Anti-mutagenic Effects of Di(2-Ethylhexyl)phthalate Isolated from Aloe vera Linne. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2010;52:593–8. doi: 10.1211/0022357001774246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Zhang P, Liu T, et al. Use of Hempseed-Oil-Derived Polyacid and Rosin-Derived Anhydride Acid as Cocuring Agents for Epoxy Materials. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2018;6:4016–25. [Google Scholar]

- Liebmann JE, Cook JA, Lipschultz C, et al. Cytotoxic studies of pacfitaxel (Taxol®) in human tumour cell lines. Br J Cancer. 1993;1993:1104–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotfy MM, Hassan HM, Hetta MH, El-Gendy AO, Mohammed R. Di-(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate, a major bioactive metabolite with antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity isolated from River Nile derived fungus Aspergillus awamori. Beni-Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci. 2018;7:263–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mcneil MJ, Porter RBR, Williams LAD. Chemical Composition and Biological Activity of the Essential Oil from Jamaican Cleome serrata. Nat Prod Commun. 2012;7:1231–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaeian R, Sadoughi F, Tahmasebian S, Mojahedi M. The role of herbal medicines in health care quality and the related challenges. J HerbMed Pharmacol. 2021;10:156–65. [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Jones DP, Ziegler TR, et al. Metabolic effects of albumin therapy in acute lung injury measured by proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of plasma: A pilot study. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:2308–13. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822571ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que NLS, Ribeiro AA, Raetz CRH. Two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy and structures of six lipid A species from Rhizobium etli CE3: Detection of an acyloxyacyl residue in each component and origin of the aminogluconate moiety. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28017–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004009200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahim A, Saito Y, Miyake K, et al. Kleinhospitine e and Cycloartane Triterpenoids from Kleinhovia hospita. J Nat Prod. 2018;81:1619–27. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.8b00211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman SMM, Munira S, Hossain MA. PHYTOCHEMICAL STUDY OF THE ARIAL PARTS OF Cleome rutidosperma DC PLANT. Indo J Chem. 2008;8:459–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjitha J, Bakiyalakshmi K, Anand M, Sudha PN. Phytochemical Investigation of n-Hexane Extract of Leaves of Cleome gynandra. Asian J Chem. 2009;21:3455–8. [Google Scholar]

- Reheim MAMA, Tolba AMES. Synthesis and Spectral Identification of Novel Stable Triazene: As Raw Material for the Synthesis Biocompatible Surfactants-Pyrazole-Isoxazole-Dihydropyrimidine-Tetrahydropyridine Derivatives. Int J Org Chem. 2016;6:44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Righi V, Apidianakis Y, Psychogios N, et al. In vivo high-resolution magic angle spinning proton NMR spectroscopy of Drosophila melanogaster flies as a model system to investigate mitochondrial dysfunction in Drosophila GST2 mutants. Int J Mol Med. 2014;34:327–33. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammar M, Abu Farich B, Rayan I, Falah M, Rayan A. Correlation between cytotoxicity in cancer cells and free radical scavenging activity: In vitro evaluation of 57 medicinal and edible plant extracts. Oncol Lett. 2019;18:6563–71. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.11054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirey RJ, Globisch D, Eubanks LM, Hixon MS, Janda KD. Noninvasive Urine Biomarker Lateral Flow Immunoassay for Monitoring Active Onchocerciasis. ACS Infect Dis. 2018;4:1423–31. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar B, Murugan R, Baskaran A, et al. Identification and characterization of process-related impurities of trans-resveratrol. Sci Pharm. 2013;81:683–95. doi: 10.3797/scipharm.1301-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari P, Kumar B, Kaur M, Kaur G, Kaur H. Phytochemical screening and Extraction: A Review. Int Pharm Sci. 2011;1:98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Tshilanda DD, Mpiana PT, Onyamboko DNV, et al. Antisickling activity of butyl stearate isolated from Ocimum basilicum (Lamiaceae) Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014;4:393–8. doi: 10.12980/APJTB.4.2014C1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente J, de Carvalho MG, Garcia-Rojas EE. Fatty acids profile of Sacha Inchi oil and blends by 1H NMR and GC-FID. Food Chem. 2015;181:215–21. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.02.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Lu Q, de Toledo RA, Shim H. Degradation of di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) by an indigenous isolate Acinetobacter sp SN13. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation. 2017;117:205–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yasir B, Astuti A, Raihan M, et al. Optimization of Pagoda (Clerodendrum paniculatum L ) Extraction Based By Analytical Factorial Design Approach, Its Phytochemical Compound, and Cytotoxicity Activity. Egypt J Chem. 2022;65:421–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Guo N, Jin H, et al. Bisphenol A drives di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate promoting thyroid tumorigenesis via regulating HDAC6/PTEN and c-MYC signaling. J Hazard Mater. 2022;425:127911. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Zhang X, Wang M, Lin Y, Zhou S. Stigmasterol Simultaneously Induces Apoptosis and Protective Autophagy by Inhibiting Akt/mTOR Pathway in Gastric Cancer Cells. Front Oncol. 2021:11. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.629008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Avula B, Joshi VC, et al. NMR fingerprinting for analysis of Hoodia species and Hoodia dietary products. Planta Med. 2011;77:851–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1250583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]