Abstract

Stereoselective α-amino C–H epimerization of exocyclic amines is achieved via photoredox catalyzed, thiyl-radical mediated, reversible hydrogen atom transfer to provide thermodynamically controlled anti/syn isomer ratios. The method is applicable to different substituents and substitution patterns about aminocyclopentanes, aminocyclohexanes, and a N-Boc-3-aminopiperidine. The method also provided efficient epimerization for primary, alkyl and (hetero)aryl secondary, and tertiary exocyclic amines. Demonstration of reversible epimerization, deuterium labeling, and luminescence quenching provide insight into the reaction mechanism.

Graphical Abstract

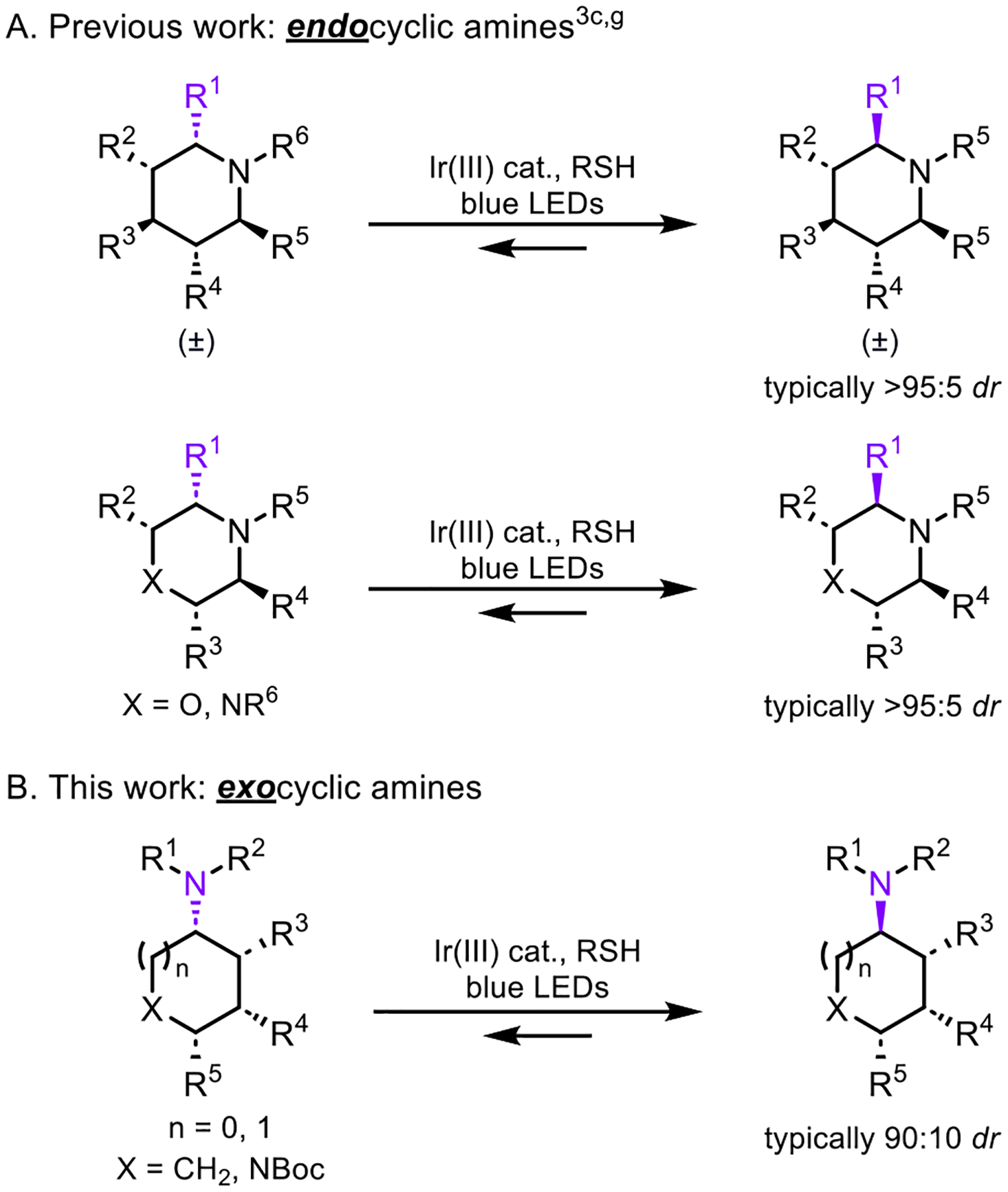

Changing the stereochemistry at a single stereogenic center in a molecule can have a profound effect on its biological activity. Consequently, mild and efficient single-step processes for site-selective epimerization are increasingly sought after. Photoredox-mediated epimerization at specific sites of a molecule via radical intermediates have become intensively investigated,1 and both contra-thermodynamic2 and thermodynamic epimerization approaches have been achieved, including diastereoselective epimerization of molecules with multiple stereogenic centers.3,4 We have previously reported on the light-mediated site-selective diastereoselective epimerization of piperidines, morpholines, and piperazines to form a more stable stereoisomer (Scheme 1A).3c,g For these transformations, mechanistic studies established that epimerization proceeds by reversible hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) at the weakest C–H bond located α to the endocyclic amine present in the saturated heterocycle.

Scheme 1.

Photoredox-Catalyzed Thermodynamic Epimerization

Herein, we report the light-mediated stereoselective α-amino epimerization of exocyclic amines (Scheme 1B), which are common motifs in drug structures and are versatile handles for further functionalization.5 A range of exocyclic amines with various functionalities and substitution patterns epimerized efficiently under the reaction conditions. Mechanistic studies, including equilibrium reactions, deuterium labeling, and luminescence quenching were performed to support that exocyclic amine epimerization proceeds via reversible thiyl-radical mediated hydrogen atom abstraction and donation at the C–H bond located α to the exocyclic amine.

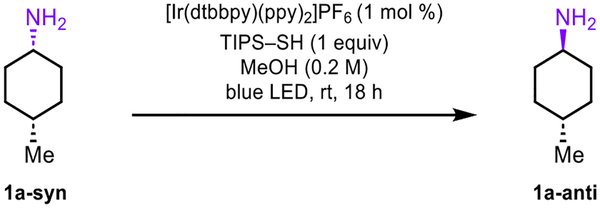

The epimerization reaction was optimized utilizing primary exocyclic amine 1a-syn (Table 1). Effective reaction conditions were identified with [Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2]PF6 as the photocatalyst, 1 equiv of triisopropylsilanethiol (TIPS–SH) as the HAT reagent in methanol under irradiation with blue light (entry 1). Reduction of the catalyst loading from 1 to 0.25 mol % provided a comparable yield and diastereomer ratio (entry 2). A range of thiols with S–H bond strengths that are weaker (entries 3 to 5) and stronger (entry 6) than TIPS–SH were explored,6 but all resulted in lower diastereoselectivities. However, reducing the stoichiometry of TIPS–SH to 0.5 equiv did not result in any reduction in the anti/syn ratio (entry 7). In contrast, 0.1 equiv of TIPS–SH provided only modest epimerization efficiency (entry 8). Moreover, MeCN was an effective solvent for the transformation (entry 9). Finally, a more strongly oxidizing photoredox catalyst was detrimental to the reaction diastereoselectivity (entry 10).

Table 1.

Optimization Studiesa

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | variation from standard conditions | Yield (%) | Dr (anti/syn) |

| 1 | none | 99 | 91:9 |

| 2 | 0.25 mol % [Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2]PF6 | 99 | 91:9 |

| 3 | 1-adamantanethiol | 99 | 85:15 |

| 4 | 1-butanethiol | 96 | 67:33 |

| 5 | cyclohexanethiol | 99 | 78:22 |

| 6 | thioacetic acid | 97 | 2:98 |

| 7 | TIPS-SH (0.5 equiv) | 94 | 91:9 |

| 8 | TIPS-SH (0.1 equiv) | 99 | 55:45 |

| 9 | MeCN as solvent | 89 | 90:10 |

| 10 | [Ir{dF(CF3)ppy}2(dtbpy)]PF6 | 84 | 21:79 |

Conditions: Reaction performed at 0.1 mmol of 1a-syn with the schlenk flask submitted to 3 freeze/pump/thaw cycles prior to irradiation in the photoreactor. Yields and diastereoselectivities determined by 1H NMR analysis of unpurified material with 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard.

We next evaluated the scope of primary exocyclic amines (Scheme 2). Cyclohexylamines with a variety of different functionalities at the 4-position of the ring epimerized with good selectivity and high yields, including a primary alcohol (1b), an N-Boc amine (1c), and a tertiary trifluoromethyl alcohol (1d). Cyclohexylamines with substituents at the 2-position were also effective substrates as demonstrated for 2-methylcyclohexylamine ((±)-1e) and a β-amino ester derivative ((±)-1f). However, for these more sterically encumbered substrates, a longer reaction time of 40 h was necessary to reach full equilibrium. Also, for (±)-1f, ethanol in place of methanol was used as solvent because significant transesterification to the methyl ester occurred when the reaction was performed in methanol.

Scheme 2.

Epimerization of Primary Exocyclic Aminesa

aIsolated yields on a 0.3 mmol scale; dr was determined by 1H NMR analysis. Crude yields and dr are noted in parenthesis and were determined by 1H NMR analysis with 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard. bCrude yield and dr were determined on a 0.1 mmol scale. c0.25 mol % instead of 1 mol % [Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2]PF6. dIsolated as HCl salt. e40 h reaction time. fEtOH instead of MeOH. g5 equiv of thiol. hIsolated as TFA salt.

Notably, N-Boc-3-amino-4-methylpiperidine ((±)-1g), which incorporates a privileged piperidine core that is a key fragment of the approved drug tofacitinib, also epimerized efficiently and in good yield.

Additionally, aminocyclopentanes were examined, with the derivative incorporating an ester at the 2-position ((±)-1h) epimerizing in high yield and good diastereoselectivity. As expected for 1,3-disubstituted cyclopentanes, while efficient epimerization was observed for (±)-1i, the anti- and syn-stereoisomers were obtained in approximately equivalent amounts. It should also be noted that under the standard reaction conditions, visible decomposition of 1h and 1i were observed by NMR analysis. However, increasing the amount of thiol from 1 to 5 equiv minimized decomposition, presumably by increasing the rate of HAT to outcompete undesired radical-based pathways.3g,7

We next explored the epimerization of exocyclic amines with a variety of different nitrogen substituents (Scheme 3). Secondary amines were evaluated with phenethyl substituted amines 1j – 1l, which epimerized in high yields and diastereoselectivities. Moreover, the desired anti-products could be obtained in diastereomerically pure form by chromatography. Significantly, epimerization of 1j was performed on a larger 1 mmol scale with similar reactions outcomes to that observed at 0.3 mmol scale.

Scheme 3.

Epimerization of Secondary and Tertiary Exocyclic Aminesa

aIsolated yields on a 0.3 mmol scale; dr was determined by 1H NMR analysis. Crude yields and dr are noted in parenthesis and were determined by 1H NMR analysis with 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard. bReaction performed on a 1.0 mmol scale at 0.6 M. c5 equiv of thiol. d40 h reaction time. e4-CzIPN instead of [Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2]PF6. fMeCN instead of MeOH. g1 equiv of quinuclidine added as an exogenous base.

The branched alkyl amine 1m provided a slightly higher anti/syn ratio than the unbranched phenethylamines 1j – 1l. However, the more sterically encumbered 2-methylcyclohexane derivative (±)-1n provided a more modest diastereoselectivity, and both 1m and (±)-1n required longer 40 h reaction times. We also evaluated the tertiary alkyl amine 1o, which epimerized to afford the product with a 91:9 anti/syn ratio. After chromatography, 1o-anti was also obtained in good yield and in diastereomerically pure form.

We next examined exocyclic N-(hetero)aryl amine derivatives. Exocyclic amines with N-phenyl (1p), electron-rich N-(4-methoxy)phenyl (1q), and electron-deficient N-(3-trifluoromethyl)phenyl (1r) substituents all epimerized without decomposition to give moderate anti/syn ratios, and in each case the anti-isomer was obtained in diastereomerically pure form after chromatography. Additionally, the N-pyridyl derivative 1s underwent epimerization without decomposition. However, perhaps due to the reduced basicity of this amine, the addition of quinuclidine as an exogenous amine base resulted in a modest increase in the rate of epimerization.

We did encounter some limitations to the substrate scope. No epimerization was observed for the approved drug tofacitinib (1t-syn), which incorporates an exocyclic tertiary amine with an electron-deficient purine substituent. Moreover, we did not detect any epimerization of acetamide 1u-syn or the Boc-protected amine 1v-syn under the standard reaction conditions. Given that amine derivatives 1t, 1u, and 1v have very modest basicity, we added quinuclidine to act as an exogenous base for deprotonation of TIPS–SH, but once again, no epimerization was detected.3f We also explored a variety of HAT thiol reagents with varying S–H bond strengths, with and without quinuclidine, and with photocatalysts with different oxidizing potentials, but in no instance was appreciable epimerization observed (Table S1). To achieve epimerization of these substrates, a more dramatic departure from our standard epimerization conditions will be required.

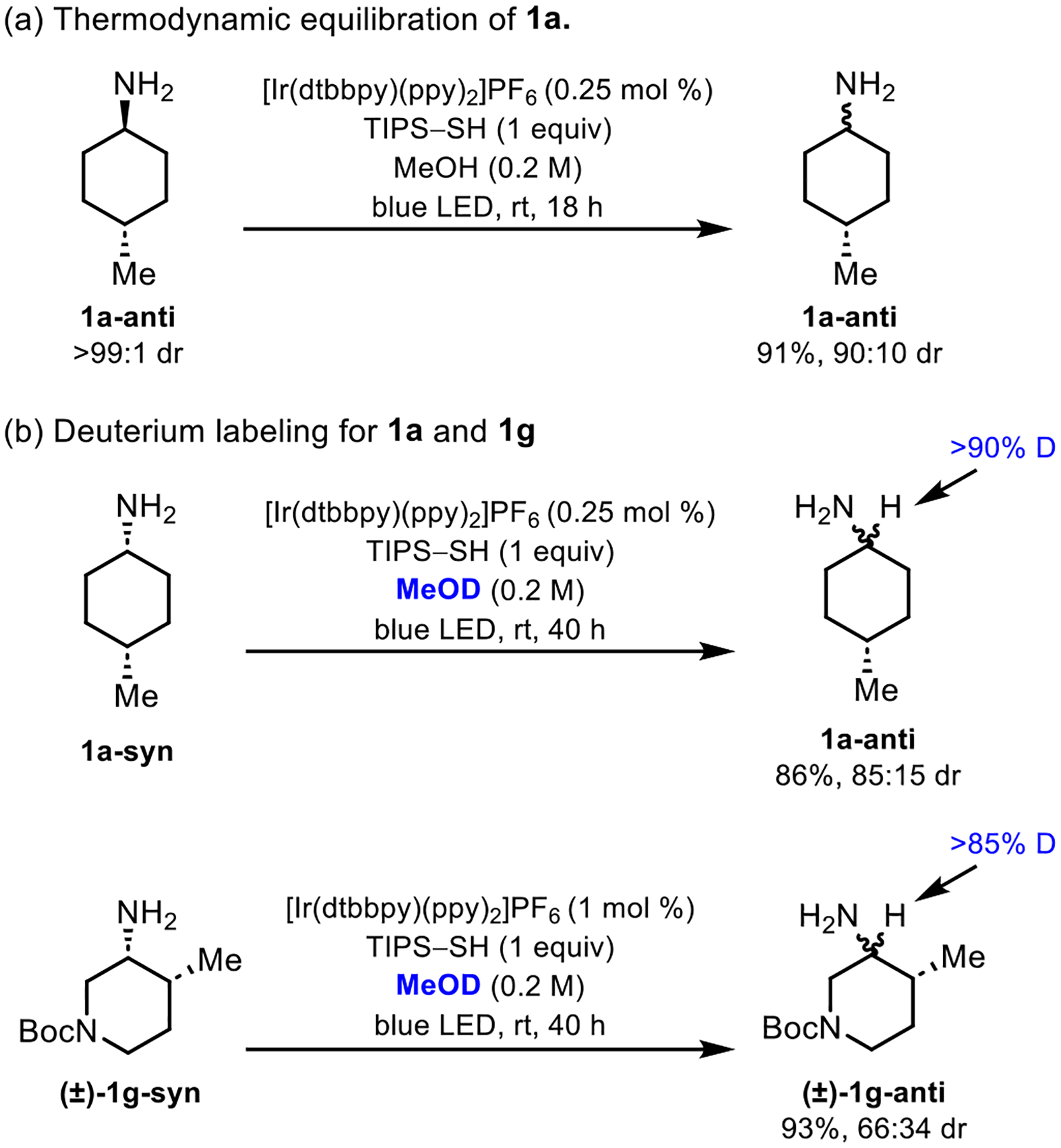

Several studies were performed to investigate the mechanism of epimerization (Figure 1). First, epimerization was determined to proceed through a reversible process that reached an equilibrium anti/syn isomer ratio. Specifically, when diastereomerically pure 1a-anti was subjected to epimerization, a 90:10 anti/syn ratio of isomers was obtained (Figure 1a), which coincides with the 91:9 anti/syn ratio obtained when 1a-syn was subjected to the same reaction conditions (see Scheme 2).

Figure 1.

Mechanistic studies.

Deuterium labeling experiments were also performed (Figure 1b). In the presence of excess methanol-d4 as the reaction solvent, TIPS–SH undergoes diffusion-controlled deuterium exchange to form TIPS–SD. Under these reaction conditions, 1a epimerized more slowly than when the reaction was performed in MeOH. However, at a 40 h reaction time, an 85:15 anti/syn isomer ratio was obtained along with extensive deuterium incorporation at the α-amino site as determined by 1H and 13C NMR (see SI). Moreover, via 2D NMR, we confirmed that deuterium was solely incorporated at the α-amino site. Similarly, for substrate (±)-1g, extensive deuteration was observed at the α-amino site while no deuterium was incorporated at the tertiary α-methyl site.

Finally, luminescence quenching experiments were performed on 1a-syn. These results establish that the mixture of TIPS–SH and 1a-syn quenched the photoexcited iridium catalyst much faster that the thiol or amine alone, with a bimolecular quenching constant of 2.13 × 108 M−1s−1 (see SI).

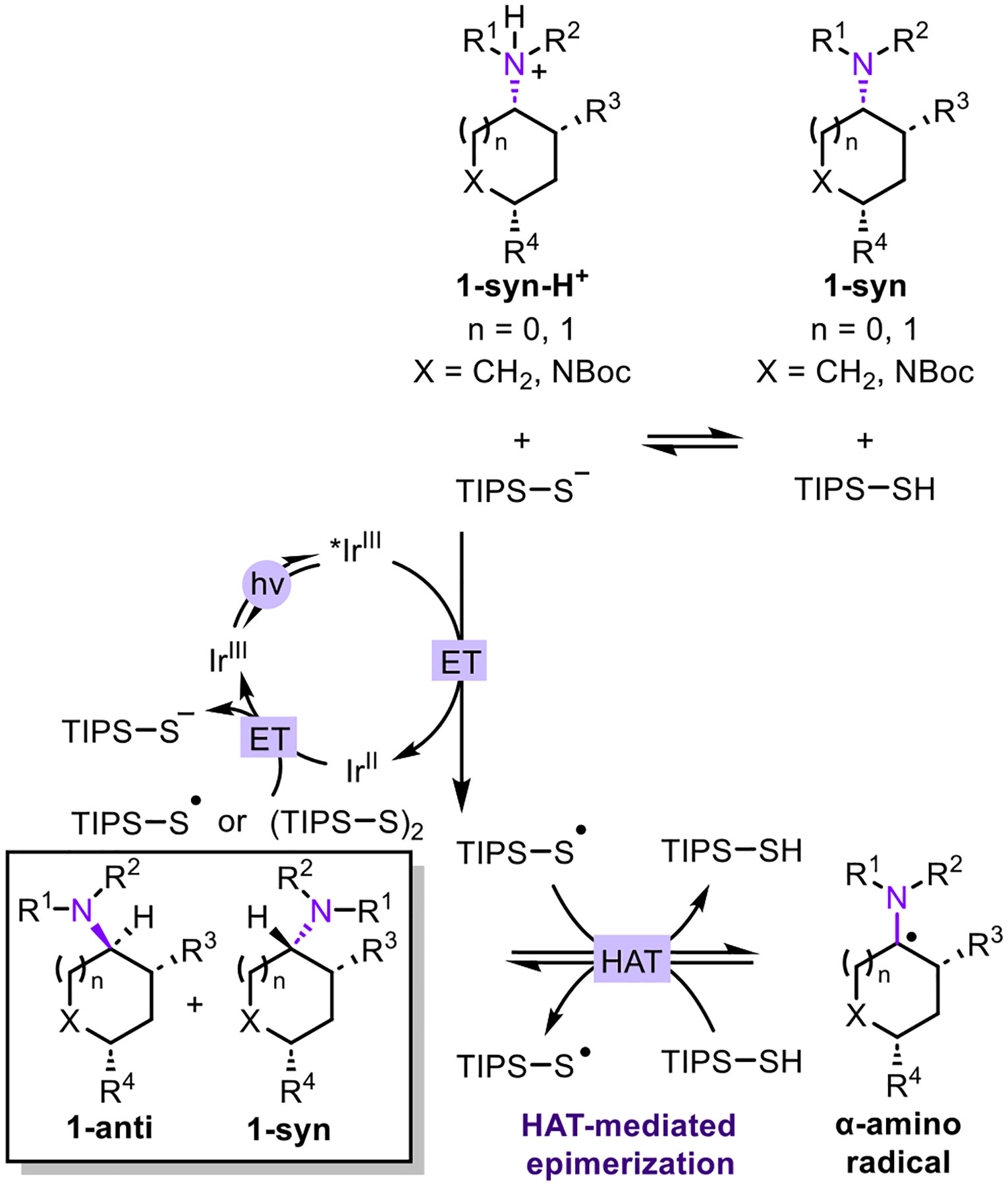

A plausible mechanism is depicted in Figure 2 based upon the aforementioned experiments and prior mechanistic studies on the epimerization of piperidines and morpholines.3c,g Acid-base equilibrium between TIPS–SH and the exocyclic amine 1 provides the thiolate anion, which quenches the photoexcited *IrIII catalyst to generate the thiyl radical and the reduced IrII catalyst. HAT between the thiyl radical and exocyclic amine 1 provides TIPS–SH and the α-amino radical, which is not configurationally stable. Reversable HAT with TIPS–SH then generates a thermodynamic mixture of 1-syn and 1-anti. Notably, for equilibration to be achieved by a reversible HAT reaction, the S–H bond dissociation energy of TIPS–SH should match with the bond dissociation energy of the α-amino C–H.7 Finally, the ground state IrIII catalyst is regenerated by electron transfer of the reduced IrII species with either the thiol radical or the disulfide.

Figure 2.

Proposed mechanism.

In conclusion, the stereoselective photocatalytic epimerization of primary, secondary, and tertiary exocyclic amines is herein described. This method results in selective epimerization at the α-amino site and provides a thermodynamically controlled anti/syn isomer ratio. Mechanistic experiments, including equilibration experiments, deuterium labeling, and luminescence quenching revealed that epimerization occurs via a reversible thiyl-radical mediated pathway.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Eric Paulson (Yale) for assistance with the fluorometer and discussions on deuterium labeling studies. The authors also thank Dr. Fabian Menges (Yale) for assistance with mass spectrometry and Noah Gibson (Yale) for assistance with the Series 5000 Parr Multiple Reactor System. This work was supported by NIH grant No. R35GM122473 (to J.A.E.) and R35GM12247306S1 (to M.A.V.-R.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Experimental procedures; characterization data; NMR spectra; deuterium labeling and other mechanistic data (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online supplementary material.

REFERENCES

- (1).DeHovitz JS; Hyster TK Photoinduced Dynamic Radical Processes for Isomerizations, Deracemizations, and Dynamic Kinetic Resolutions. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 8911–8924. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Wang P-Z; Xiao W-J; Chen J-R Light-Empowered Contra-Thermodynamic Stereochemical Editing. Nat. Rev. Chem 2023, 7, 35–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Wang Y; Carder HM; Wendlandt AE Synthesis of Rare Sugar Isomers Through Site-Selective Epimerization. Nature 2020, 578, 403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Walker MM; Koronkiewicz B; Chen S; Houk KN; Mayer JM; Ellman JA Highly Diastereoselective Functionalization of Piperidines by Photoredox-Catalyzed α-Amino C–H Arylation and Epimerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 8194–8202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shen Z; Walker MM; Chen S; Parada GA; Chu DM; Dongbang S; Mayer JM; Houk KN; Ellman JA General Light-Mediated, Highly Diastereoselective Piperidine Epimerization: From Most Accessible to Most Stable Stereoisomer. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 126–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Oswood CJ; MacMillan DWC Selective Isomerization via Transient Thermodynamic Control: Dynamic Epimerization of trans to cis Diols. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 93–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang Y-A; Gu X; Wendlandt AE A Change from Kinetic to Thermodynamic Control Enables trans-Selective Stereochemical Editing of Vicinal Diols. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 599–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Kazerouni AM; Brandes DS; Davies CC; Cotter LF; Mayer JM; Chen S; Ellman JA Visible Light-Mediated, Highly Diastereoselective Epimerization of Lactams from the Most Accessible to the More Stable Stereoisomer. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 7798–7803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Shen Z; Vargas-Rivera MA; Rigby EL; Chen S; Ellman JA Visible Light-Mediated, Diastereoselective Epimerization of Morpholines and Piperazines to More Stable Isomers. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 12860–12868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Park S; Kang G; Kim C; Kim D; Han S Collective Total Synthesis of C4-Oxygenated Securinine-type Alkaloids via Stereocontrolled Diversifications on the Piperidine core. Nat. Commun 2022, 13, 7482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Carder HM; Wang Y; Wendlandt AE Selective Axial-to-Equatorial Epimerization of Carbohydrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 11870–11877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Zhang Y-A; Palani V; Seim AE; Wang Y; Wang KJ; Wendlandt AE Stereochemical Editing Logic Powered by the Epimerization of Unactivated Tertiary Stereocenters. Science 2022, 378, 383–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Wen L; Ding L; Wang S; An Q; Wang H; Zuo Z Multiplicative Enhancement of Stereoenrichment by a Single Catalyst for Deracemization of Alcohols. Science 2023, 382, 458–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).For a seminal report on thermodynamically controlled radical C-H isomerization using a hypervalent iodine reagent and H2O, see:; Wang Y; Hu X; Morales-Rivera CA; Li G-X; Huang X; He G; Liu P; Chen G Epimerization of Tertiary Carbon Centers via Reversible Radical Cleavage of Unactivated C(sp3)–H Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 9678–9684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Roughley SD; Jordan AM The Medicinal Chemist’s Toolbox: An Analysis of Reactions Used in the Pursuit of Drug Candidates. J. Med. Chem 2011, 54, 3451–3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Trowbridge A; Walton SM; Gaunt MJ New Strategies for the Transition-Metal Catalyzed Synthesis of Aliphatic Amines. Chem. Rev 2020, 120, 2613–2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Luo Y-R Comprehensive Handbook of Chemical Bond Energies; CRC Press, 2007; pp 1–1688. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Escoubet S; Gastaldi S; Vanthuyne N; Gil G; Siri D; Bertrand MP Thiyl Radical Mediates Racemization of Benzylic Amines. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2006, 2006, 3242–3250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online supplementary material.