Abstract

Objective

Diagnostic-quality neuroimaging methods are vital for widespread clinical adoption of low field MRI. Spiral imaging is an efficient acquisition method that can mitigate the reduced signal-to-noise ratio at lower field strengths. As concomitant field artifacts are worse at lower field, we propose a generalizable quadratic gradient-field nulling as an echo-to-echo compensation and apply it to spiral TSE at 0.55 T.

Materials and methods

A spiral in–out TSE acquisition was developed with a compensation for concomitant field variation between spiral interleaves, by adding bipolar gradients around each readout to minimize phase differences at each refocusing pulse. Simulations were performed to characterize concomitant field compensation approaches. We demonstrate our proposed compensation method in phantoms and (n = 8) healthy volunteers at 0.55 T.

Results

Spiral read-outs with integrated spoiling demonstrated strong concomitant field artifacts but were mitigated using the echo-to-echo compensation. Simulations predicted a decrease of concomitant field phase RMSE between echoes of 42% using the proposed compensation. Spiral TSE improved SNR by 17.2 ± 2.3% compared to reference Cartesian acquisition.

Discussion

We demonstrated a generalizable approach to mitigate concomitant field artifacts for spiral TSE acquisitions via the addition of quadratic-nulling gradients, which can potentially improve neuroimaging at low-field through increased acquisition efficiency.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance imaging, Neuroimaging, Low-field MRI, Turbo spin echo, Non-cartesian, Concomitant field

Introduction

Imaging with lower field strength MRI, such as at 0.55 T, has garnered recent interest due to the potential for increased accessibility to neuroimaging, in addition to novel opportunities such as pulmonary and emergency imaging [1–5]. For widespread clinical adoption of 0.55 T, diagnostic efficacy should be comparable to that at clinical standard field strengths. One fundamental neuroimaging sequence is a multi-echo spin-echo sequence, often known as turbo spin-echo (TSE). Turbo spin-echo offers high signal for many applications and is opportune for low-field imaging, which suffers from intrinsically lower signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) compared to 1.5 T and 3 T.

Spiral imaging methods using long readouts have been shown to compensate for the reduced SNR at low field by exploiting longer and increased acquisition efficiency [6]. Spiral TSE has been successfully demonstrated at 3 T, but at 0.55 T, where the acquisition efficiency may be best appreciated, this technique will be more susceptible to concomitant (Maxwell) fields artifacts [7].

Concomitant fields are produced in response to applied gradients in an MRI scanner, as predicted by Maxwell’s equations. These additional concomitant fields are inversely proportional to field strength , and scale quadratically with gradient amplitude and distance from magnet isocenter [8–11]:

| (1) |

Concomitant fields generate an additional spatially varying phase accrual and can cause signal shading, blurring, or cancellation. Though single-echo acquisitions can generally be corrected using reconstruction methods that compensate for the phase accrual [8, 12], multi-echo imaging is more sensitive to signal loss due to the additional fields and signal refocusing. Gradient waveform-based compensation is preferred for concomitant terms as the spatial dependency of concomitant phase will not be correctable using RF phase adjustments, and tailored RF pulses would be SNR-inefficient [13].

Li, et al. demonstrated concomitant field compensation at 3 T for spiral readouts by using quadratic gradient-field nulling between excitation and refocusing pulses [14, 15], as originally described by Zhou, et al. [10]. However, it may be insufficient at lower fields to use only quadratic nulling between the 90° and first 180° pulse. When using unique gradients per spiral readout, the CPMG condition may be disrupted if the inter-echo phase variation caused by concomitant-fields is sufficiently large and will lead to unrecoverable signal loss. At lower field, where concomitant field effects are inherently larger, the inter-echo phase variation may lead to significant image artifacts.

In this study, we aim to implement spiral TSE for increased SNR-efficiency at 0.55 T and demonstrate a sequence-based compensation for concomitant fields that is generalizable to arbitrary readout gradient waveforms.

Methods

Compliance with ethical standards

Imaging was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03331380) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Sequence-based concomitant-field compensation

In spiral TSE, a unique gradient waveform can be used for spatial encoding at each echo. Spiral interleaves are rotated to distribute k-space sampling, and each spiral readout gradient will produce a unique concomitant-field (Supplementary Fig. 1). We propose to minimize the residual self-squared gradient terms (Eq. 1) through quadratic nulling [10]. For ideal concomitant phase compensation at 0.55 T, a “full-train” compensation is achieved by ensuring that the phase at the echo time is nulled and that the concomitant phase prior to each refocusing pulse is constant, thus maintaining the CPMG condition. By comparison, we refer to “first-echo” compensation as the additional gradient waveform between the excitation and first refocusing pulse which corrects only for the first acquisition in the TSE train.

The full-train compensation concept could be generalized to any arbitrary readout waveform (Fig. 1). In the schematic, the concomitant field induced phase , as calculated by the gradient self-squared integral , is shown for three compensation strategies: none (grey), “first-echo” (black) and the proposed “full-train” compensation (red). The most severe image artifacts will be produced from “no compensation” due to large variations in phase between echoes. The “first echo” compensation gradient between the 90° and 180° pulse (solid black outline) will correct the for the phase from first readout in the TSE train , such that the induced phase at the first and the second refocusing pulse are both . Typically, the first-echo compensation is calculated so there is no self-squared phase at the acquisition echo-time, i.e.: . In Fig. 1, the second readout will induce a larger concomitant field phase , producing a net different phase by the next refocusing pulse, which can lead to image artifacts. The proposed “Full Train” compensation (solid red outline) adds extra bipolar gradients, tailored for each readout as determined by the self-squared terms, that increase the induced concomitant field phase to a sequence-specific target value at each refocusing pulse in the echo train. However, these additional bipolar gradients will reduce the acquisition efficiency.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating a turbo spin-echo sequence with arbitrary readout gradient waveforms , with quadratic gradient nulling modules for concomitant field-compensation. Readout gradients are indicated with dashed lines and concomitant field compensation gradients are represented with solid lines. The “first echo” compensation gradient is outlined in a solid black box and the “full-train” solid red boxes represent the proposed additional bipolar compensation gradients such that the self-squared concomitant terms are consistent for the entire echo-train. The schematic plots the gradient-self squared integral, which is proportional to the phase induced by concomitant fields , for three situations: no compensation (grey curve), “first-echo” compensation (black curve) and the “full-train” compensation (red curve). For the CPMG condition to be met, the phase at each refocusing pulse should be equal. For no compensation, the phase between the first (1) and the second (2) refocusing pulse is different because of the phase induced by the first readout , leading to non-recoverable signal loss. The first-echo compensation will induce half the concomitant field phase of the first readout before the first and second refocusing pulses (1 and 2). However, the next readout may not generate the same concomitant field phase (e.g., ) such that at the following refocusing pulse (3). For full-train compensation, the compensation bipolar gradients adjust the self-squared gradient term to a sequence-specific target phase , maintaining the CPMG condition at every refocusing pulse along the echo-train

In this study, we used spiral in–out readouts (Fig. 2), and the self-squared quadratic nulling was calculated based on the prescribed spiral readout gradients in the logical axes (phase, read, slice) during sequence preparation, and therefore flexible to changes in resolution, field-of-view, and spiral design. Full-train compensation was practically achieved by calculating the self-squared integrals of each spiral arm rotation, selecting the maximum as the target phase, and then adding bipolar gradients before and after each spiral in–out readout for all echoes.

Fig. 2.

Pulse sequence diagram showing the spiral in–out turbo spin-echo acquisition with inter-echo “full-train” concomitant field-compensation (red gradients) and slice-only spoiling as used for the in-vivo imaging. A ‘spiral-out’ gradient, i.e., half of the ‘in–out’ readout, played between the 90° and 180° RF pulses, is the ideal pre-compensation for the first echo, and an additional bipolar is played to adjust the concomitant field phase to a target value for compensation of all the echoes in the train

Simulations

Concomitant field simulations of the imaging plane were calculated using Eq. 1, for first-order and cross-term effects. Simulations were performed in the sagittal orientation (no obliqueness) for a field of view and resolution matching the in vivo acquisition, using a spiral in–out read-out with a maximum gradient amplitude of 34 mT/m for six echoes at 0.55 T. Concomitant phase was calculated by integrating the gradients between the excitation and first refocusing pulse, and over each echo-spacing separately. The phase at each echo time was determined by inverting the phase at each refocusing pulse and adding the next echo-spacing’s accrued phase. The simulation code can be found at https://github.com/NHLBI-MR/concomitant_field_simulations.

Simulations were performed for the conditions described in Table 1. The simulations were chosen to compare practical situations and previous literature. First, a worst-case simulation (case 1 in Table 1) was performed to demonstrate the severity of applying no concomitant field corrections. Next, we simulated the idealized zero concomitant field induced phase at echo-time (case 2), where the same spiral in–out readout was used for all six echoes, and the spiral-out gradient (i.e., half of the waveform) was used between the excitation and refocusing pulse for ‘first-echo’ compensation. However, this acquisition approach, akin to the waveform symmetrization proposed by Zhou et al., is relatively inefficient to fully sample an image.

Table 1.

Concomitant field simulations with varied first-echo and full train concomitant field compensation methods, and different spiral arm distribution across the 6 echoes

| Case | First-echo compensation | Inter-echo compensation | Echo-train sampling |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 1 | None | None | 60° step size (spiral arms distributed evenly across echoes) |

| 2 | Spiral-out | None (First-echo only) | 0° (same spiral arm, idealized for no concomitant field at echo time) |

| 3 | Bipolar (Li et al.) | None (First-echo only) | 60° step size (distributed evenly) |

| 4 | Bipolar (Li et al.) | Full-train bipolar | 60° step size (distributed evenly) |

| 5 | Spiral-out | None (First-echo only) | 60° step size (distributed evenly) |

| 6 | Spiral-out | Full-train bipolar | 60° step size (distributed evenly) |

| 7 | Spiral-out | Full-train bipolar | 15° step size (spiral arms partially cover k-space) |

Two first-echo compensation methods were simulated: a bipolar gradient (case 3) versus a spiral-out waveform (case 5). The bipolar gradient was designed to match the first spiral interleave’s self-squared gradient integral, as proposed by Li et al. [14], where the bipolar gradients are designed in a 1–2-1 or 1–2-2–2–1 pattern to minimize cross terms. An analogous approach is commonly used for Cartesian TSE. Alternatively, using the spiral-out portion of the first readout of the echo-train will provide ideal compensation for the first echo as the cross terms and self-squared terms are both accounted for (case 5 and 6). The two first-echo compensation strategies were tested for both first-echo only (cases 3 and 5) and full-train (cases 4 and 6) compensation.

Most of these simulations distributed the spiral rotations around k-space, e.g., for an echo train length of 6, the angular step size is (360/6) 60° for full k-space coverage – a typical approach for a single shot acquisition [16]. Alternatively, a configuration using smaller rotation angles (15°) between successive spiral readouts in the echo-train was also simulated (case 7). This configuration will have more similar spiral waveforms for each echo and is therefore expected to have less concomitant field variation between echoes but will only partially cover k-space.

To evaluate the effects of the concomitant field compensation gradient nulling, the mean root-sum-square (RSS) error of the induced phase across the refocusing pulses were evaluated within a region of interest covering the central 50% of the field-of-view.

MRI Protocols

Imaging was performed on a prototype 0.55 T system (MAGNETOM Aera, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany), with a maximum gradient strength of 40 mT/m, maximum slew rate of 180 mT/m/ms, and a 16-channel head coil.

A turbo-spin-echo pulse sequence was applied with two readouts: Cartesian and a spiral in–out. Spiral imaging was matched to Cartesian for resolution and scan-time. T2-weighted imaging parameters for both sequences included: TR = 3280 ms, matrix = 320 × 320, FOV = 24 × 24 cm2, in-plane resolution = 0.75 × 0.75 mm2, and slice-thickness 5 mm (1.25-mm gap between slices) with 11 slices centered around isocenter. The Cartesian acquisition used the following parameters: effective TE = 102 ms, ETL = 16, echo-spacing = 12.7 ms, refocusing flip angle = 150°, readout bandwidth 124 Hz/px (8.1 ms sampling time), averages = 3, and scan time = 3 m 22 s. The spiral acquisition used the following parameters: effective TE = 147 ms, ETL = 6, echo-spacing = 42 ms, refocusing flip angle = 180°, 24-shot spiral in–out with a 27.9 ms sampling time, averages = 16 (8 averages × 2 interleave orders), scan time = 3 m 30 s. For the sequence configuration used in this study, the full-train compensation gradients added a maximum time penalty of 3.4 ms per echo.

Spiral imaging was performed with T2-compensation which reverses the interleave order in paired averages to minimize k-space signal variation due to evolving T2 contrast [14], i.e., 8 complete averages of two interleave orders were acquired. Spiral waveforms were designed using Hargreaves’ variable density spiral code (available at https://mrsrl.stanford.edu/~brian/vdspiral/) using a maximum gradient amplitude of 20 mT/m and 34 mT/m, and a 25% reduction in FOV at the edge of k-space [17]. Spiral readouts are rotated two-fold the designed interleave number to reduce the fold-over artifacts.

Imaging experiments

To demonstrate the effects of compounding concomitant field compensation and spoiling, phantom imaging using a NiSO4 doped water bottle (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) was performed with no compensation, first-echo compensation, and full-train compensation in the axial plane with two refocusing spoiling modes: slice only and both read- and slice-spoiling. Spoiling on two-axes is common in sagittal neuroimaging, and the full-train compensation is likely necessary when spoiling is integrated with the readout waveforms.

Additionally, compounding concomitant field compensation, was further demonstrated in a structural phantom doped with CuSO4, NiCl2 for the T1 array, and MnCl2 for the T2 array (NIST/ISMRM system phantom, CaliberMRI, Colorado, USA) and a human volunteer were imaged in the sagittal plane using the above spiral TSE protocol with a maximum gradient of 34 mT/m.

Brain imaging using the full-train compensation was acquired in 8 healthy volunteers (mean age = 27.8 ± 4.8 years old, M/F = 4/4) and compared to Cartesian acquisitions. Images were aligned to diagnostic axial and sagittal planes, and Cartesian and spiral acquisitions were acquired sequentially.

Analysis

All image reconstruction was performed using the ISMRM raw data format and tools based from open-source MATLAB code (https://github.com/hansenms/ismrm_sunrise_matlab and https://github.com/andyschwarzl/gpuNUFFT) [18]. A multi-frequency interpolation (maximum frequency 505 Hz, using 16 bins) reconstruction method proposed by King, et al. [8] was used to correct residual concomitant field blurring, due to phase accrued during the spiral readout. Phantom experiments with compounding concomitant field compensation were assessed by normalized root-mean-square-error (RMSE) compared to the fully corrected images, from a region of interest encompassing the phantom signal.

Signal-to-noise (SNR) was estimated using the pseudo-replica method, using 100 replicas for both Cartesian and spiral acquisitions [19]. Regions of interest (ROI) were manually drawn to cover the whole brain for SNR analysis, and grey/white matter regions were manually drawn in the frontal cortex in an axial and sagittal slice for contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) assessment. SNR and CNR was averaged across the ROIs, CNR was calculated from the difference in SNR between white and grey matter, and a paired t-test was used to compare Cartesian and spiral imaging.

Results

Simulations

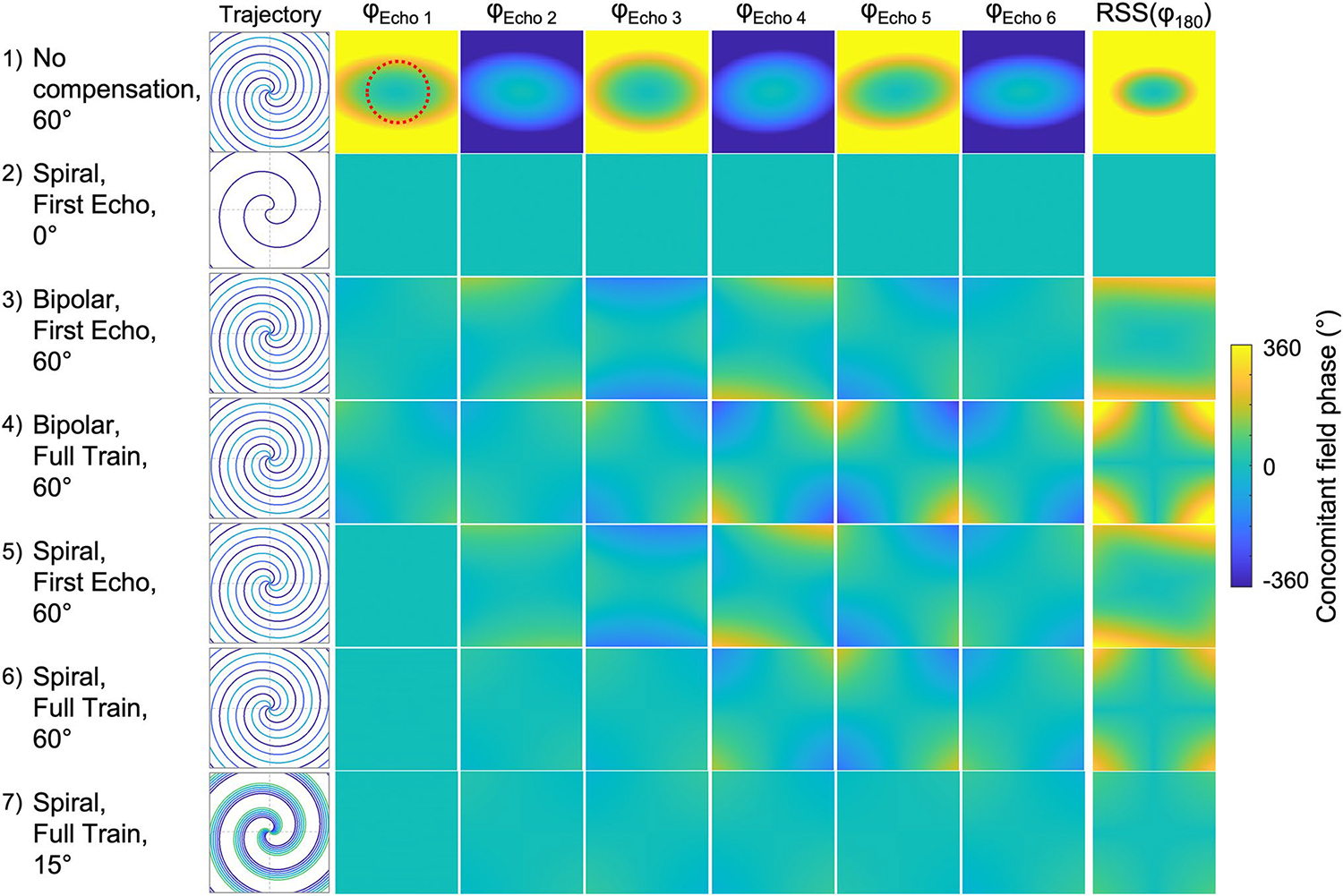

Figure 3 shows the simulated concomitant phase accruing for each echo in a sagittal imaging plane at 0.55 T, for the different acquisition and correction strategies outlined in Table 1. These simulations highlight the spatial variation of the concomitant field phase due to cross terms in Eq. 1 that are not compensated with our proposed approach (demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 2). We have observed that if the concomitant field-induced phase difference between refocusing pulses equals 90°, 270°, etc. degrees, this will lead to non-recoverable signal loss for turbo spin-echo (Supplementary Fig. 3). In the worst-case scenario, with no concomitant field compensations at all, it is clear to see that all echoes will be severely affected, with a mean RSS phase between the echoes of 245.6° within the central ROI. As expected, in the concomitant-phase ideal acquisition (case 2), using a spiral first-echo compensation and repeating the same spiral in–out readout throughout the echo train, the concomitant phase is 0° at each echo time.

Fig. 3.

Simulations of concomitant phase for six echoes with spiral TSE at 0.55 T. Concomitant phase accrued across the imaging plane at each echo-time (φEcho) and seven different sequence configurations are compared (see Table 1). The sampled trajectory for each configuration is shown on the left, and the root-sum-square (RSS) showing the accumulated phase from all refocusing pulses (φ180), and the potential for signal loss, is shown on the right. As the spiral-step size increases, the concomitant field variation increases, and the concomitant field phase becomes more difficult to compensate. Full-train compensation offers the most mitigation. The mean RSS phase from the central region-of-interest (red dotted line) was 245.6°, 0.0°, 20.6°, 25.1°, 22.5°, 13.0°, 3.0° for cases 1–7, respectively

The other simulations (cases 3–7) use a distributed k-space sampling over the echo-train, as done experimentally for maximal efficiency. It is apparent that using only a bipolar first-echo gradient and not correcting for inter-echo readout variations (case 3) will accrue a significant amount of concomitant phase (mean RSS phase in ROI = 20.6°) at 0.55 T. The full-train compensation with bipolar first-echo gradient (case 4) redistributes the concomitant-field phase in space, but within the central ROI the mean RSS phase increases to 25.1° (+ 22%). Using a spiral-out first-echo compensation and evenly distributing the spiral interleaves resulted in a mean RSS phase of 22.5° for first-echo (case 5) and 13.0° for full-train (case 6) compensation, a relative reduction of −42% compared to case 3. Finally, rotating the spirals by a smaller angle (case 7), such that the waveforms are more similar, but with limited k-space coverage, resulted in a small mean RSS phase of 3.0°.

Overall, as the spiral-step size increases for improved k-space coverage, the concomitant field variation between echoes increases, which limits the ability of the sequence-based compensation to minimize artifacts arising from the disrupted CPMG condition. The distribution of the phase variation between echoes is highly dependent on the concomitant field compensation strategy. Full-train compensation offers a minimal phase variation in the center of the field-of-view and allows for flexible sequence design for spiral arm distribution and readout strategy.

Phantom imaging

Image degradation and signal loss in phantom images, due to concomitant fields in a spiral turbo-spin-echo acquisition, are illustrated in Fig. 4. As expected, images with no compensation show severe signal loss at 0.55 T. Spoiling on both the slice and readout axes yields significant artifacts with only first-echo compensation compared to slice-only spoiling. In comparison to full-train compensated images, slice-only spoiling had a NRMSE of 38% and 9% respectively for the no-compensation and first-echo compensation, and slice-and-read spoiling had a NRMSE 75% and 59% respectively for the no-compensation and first-echo compensation.

Fig. 4.

Effect of full-train concomitant field compensation at 0.55° T with different spoiling regimes in a doped water bottle phantom in an axial plane. ‘No compensation’ has no read-out direction compensation between the excitation and refocusing pulse, to visualize the potential extent of signal loss and artifacts (arrows). First-echo compensation shows residual concomitant field differences between spiral rotations. Spoiling in both the readout and slice directions is common for spine imaging, and it is clear from the signal loss that full train compensation is necessary for this spoiling regime

Figure 5, top row, visualizes the effects of compounding sequence-based concomitant field corrections in sagittal images of a phantom, using slice-only spoiling. Black bands appear where the phase accrued from the spiral waveforms substantially disrupts the CPMG condition. Compensating only the first echo improves this greatly, but still yields residual image artifacts due to the concomitant field variation between subsequent spiral interleaves. Full-train compensation minimizes signal loss due to concomitant fields. The reconstruction-based correction can successfully deblur the effects of additional phase accrual during the readout induced by concomitant fields. Residual artifacts seen in the full-train compensation images are attributed to the strong edges of the phantom structure as well as the non-physiologic T2 values of the fluid bath (> 2.6 s) leading to large stimulated-echoes.

Fig. 5.

Example sagittal spiral TSE images with slice-only spoiling demonstrating the effects of compounding corrections for concomitant gradients in both a phantom (top row) and in vivo (bottom row). Left-to-right, images are shown with increasing levels of concomitant field compensation: none, first-echo, full-train, and full-train with image reconstruction based deblurring

In vivo imaging

In vivo imaging of the brain at 0.55 T (Fig. 5, bottom row) shows that the first-echo compensation prevented visible banding for slice-only spoiling configurations but retains some artifacts. Full-train compensation improved overall image fidelity with residual blurring. Finally, the combination of full-train sequence correction and reconstruction-based correction for blurring form a robust approach that can be generalized for imaging approaches.

Figure 6 provides example axial and sagittal images from 5 healthy volunteers, comparing spiral TSE to standard Cartesian TSE. Image quality using spiral TSE was comparable to its Cartesian counterpart, with no visible artifacts or signal shading. Signal-to-noise ratio measurements across 8 healthy subjects demonstrated a significant increase using a spiral readout for both axial (Cartesian = 18.2 ± 1.1 vs. spiral = 21.3 ± 1.2, p < 0.0001) and sagittal (Cartesian = 18.0 ± 1.8 vs. spiral = 21.0 ± 2.0, p < 0.0001) imaging for identical scan time and image resolution. However, CNR was not significantly different between the two techniques (axial: Cartesian = 3.3 ± 2.4 vs Spiral = 5.2 ± 1.7, p = 0.053 and sagittal: Cartesian = 4.6 ± 1.6 vs Spiral = 4.9 ± 1.3, p = 0.295).

Fig. 6.

Example images from five healthy volunteers for Cartesian and spiral TSE, for axial and sagittal imaging orientations, and the corresponding signal-to-noise ratios (whole-brain) and contrast-to-noise ratios (frontal cortex) from 8 healthy volunteers. Spiral imaging exhibited significant improvement in SNR across both orientations (p < 0.0001 for both axial and sagittal), but no significant improvement in CNR (p > 0.05)

Discussion

We have demonstrated a quadratic gradient-field nulling method to mitigate self-squared concomitant fields in multi-spin-echo sequences and applied this to 2D spiral TSE at 0.55 T. Full compensation of the echo train is necessary to avoid non-recoverable signal loss by equalizing phase accrual at the time of each echo and each refocusing pulse. We have presented this generalizable approach for compensating concomitant fields in TSE readouts and demonstrated the value at lower field strengths where these artifacts are exacerbated.

Low-field MRI has been of recent interest to make MRI more accessible in low-resource areas, and for new clinical applications including ultra-low-field portable systems [2–4, 20]. It is paramount that low field MRI systems maintain robust and rapid neuroimaging capabilities. SNR-efficient protocols that use long readouts, leveraging the longer and improved -homogeneity, can mitigate the reduced SNR with lower magnetic field strengths [1, 6, 12, 21].

First-echo compensation is common for most Cartesian TSE implementations, and was previously demonstrated for spiral 2D TSE implementations at 3 T to produce high quality images [14]. Imaging at 3 T generates approximately 5.5 × less concomitant field than predicted at 0.55 T, and the variation in induced concomitant field between spiral interleaves would be less significant on image quality. We observed that the concomitant field artifacts were amplified when the sequence protocol employed integrated read spoiling in addition to the slice spoiling, commonly used in axial -weighted TSE spine imaging to allow for flow compensation in the slice direction. For our application at 0.55 T, we determined that full-train compensation was necessary to mitigate artifacts and to enable maximum flexibility in sequence design (e.g., spiral arm ordering and spoiling). The full-train approach is generalizable such that concomitant fields can be compensated at each echo time, making alternative readout strategies feasible, such as a 2D ring sampling for specific TE selection or partitioned 3D TSE imaging [16, 22–24].

Our sequence used a spiral-out gradient between the excitation and first refocusing pulse, as originally proposed by Li et al. [14, 15], which will provide optimal compensation for both the self-squared terms and cross-terms. For a spiral in–out design, the echo-time is dependent on the spiral waveform, so the use of a spiral gradient for compensation here will not alter the minimum echo-time. In addition, this waveform could potentially be used for a reference acquisition, such as a field map.

Our spiral 2D TSE approach employed the -compensation strategy as demonstrated by Li, et al. [14]. This is an effective approach to minimize the PSF blurring due to contrast variations in k-space, but this may still yield image blurring due to long echo-train durations when combined with long readouts. This method limits the TE choice for spiral TSE, as it will be halfway through the train where the signal averages out. A dynamic selection in contrast may be achievable by resolving the whole echo train using KWIK filtering, model-based reconstruction, or -shuffling [25–27].

The SNR advantage of the spiral imaging comes from the relative scan efficiency of the sequences. The Cartesian sequence has more echoes in its TSE train, thus the refocusing pulses are an acquisition “inefficiency”. Though the measured gain in SNR from the spiral readouts in this study was small, it matched expectations from the relative sampling times. The ratio of data sampling time to TR, was approximately 3.9% vs. 5.1% for the Cartesian and full-train compensated spiral TSE, respectively. Using the total acquisition time from the different scan efficiencies, the spiral acquisition sampled 38.4% more data, and as SNR scales with data sampling time , this translates to ~ 18% more SNR, compared to the measured 17.2 ± 2.3%. The increased SNR however did not lead to an increase in measured CNR between white and gray matter measured in the frontal cortex. This may be due to the effective averaged contrast in the spiral sequence, as mentioned above. Previous literature has shown skipping the first echo acquisition can increase the contrast though at a cost of acquisition efficiency [14].

Though the spiral readouts are long to maximize the scan efficiency, there are two major sources of sequence inefficiency in this implementation: First, the time between the excitation and refocusing pulse extends with the longer readout duration in the echo train. This “dead-time” can be potentially salvaged with a reference imaging readout such as for coil-sensitivity or field mapping. Second, the bipolar gradients implemented in this proof-of-concept study are acquisition inefficient: to be conservative, we did not overlap the bipolar gradients with the refocusing spoiler gradients, which added a maximal penalty of 3.4 ms per echo (~ 12% or the readout duration). It is possible to design a sequence where the user can choose how long a time penalty the compensation gradients will incur, at a predictable loss to the fidelity of the concomitant gradient correction. Another potential solution would be to combine the spiral readout with a target M0 refocusing lobe which achieves a consistent self-squared concomitant field per interleave. Open-source toolboxes such as GrOpT (https://github.com/cmr-group/gropt) could help efficiently implement this on MRI systems [28]. As demonstrated by the simulations, a sequence designed to use the same interleave throughout the echo-train would negate the need for the full-train compensation gradients and be the optimal acquisition-efficient sequence. However, this sequence is less efficient at sampling k-space as it will require the designed interleaves number of excitations to form a fully-sampled image.

The simulations demonstrated that the concomitant field compensations designed from the gradient self-squared terms will not be able to correct for all points in the imaging plane, but overall reduce the potential artifacts. From phantom imaging and simulation, we determined that a rule-of-thumb “livable” value for the self-squared integral of a gradient, before artifacts become severe at 90° induced additional phase, is approximately 800 (mT/m)2 ms for sagittal TSE imaging with a 24-cm field of view (supplementary Fig. 3). The proposed technique would be applicable at larger field-of-views, for example as used for spine imaging, though gradient derating or small spiral rotations may be necessary to minimize the phase accrual within the region of interest between successive echoes. Ultimately, the optimal approach will be application-specific, depending on the target organ and k-space sampling approach.

Limitations

This study focused on sequence implementations to mitigate image degradation due to concomitant gradients and did not implement advanced reconstruction techniques such as deblurring and model-based reconstruction for post-hoc image quality improvement. A reconstruction correction that deblurs concomitant gradients was implemented here to demonstrate the influence of concomitant fields at low static field strength. Deblurring of spiral readouts is a common requirement at higher fields, but at low-field the increased field homogeneity facilitates long readouts without the need for additional reconstruction corrections. A combined correction for off-resonance and concomitant gradients may be possible employing a conjugate phase or expanded-encoded model reconstruction “MaxGIRF” [7, 29, 30].

In the concomitant gradient compensation implemented here, the quadratic nulling is calculated in the logical axes. This will yield a discrepancy when imaging in radiological views, though we determined the phase error in slightly oblique imaging used in brain was < 5% in the field-of-view. However, more oblique imaging, such as cardiac and spine applications, may require per-physical axis gradient corrections. In addition, the quadratic nulling is based on the gradient self-squared integral and given the spatial dependency of concomitant field fields and the cross-terms, these will not be a perfect correction.

Conclusion

We have shown that spiral TSE with long readouts to maximize SNR efficiency can be applied at 0.55 T for diagnostic-quality brain imaging. We demonstrated a method of echo-to-echo concomitant field compensation, which is necessary for spiral TSE low-field, but also applicable to all field strengths and generalizable to other readout trajectories.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NHLBI DIR (Z01-HL006213, Z01-HL006257) and the University of Virginia-Coulter Translational Research Partnership. We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Siemens Healthcare in the modification of the MRI system for operation at 0.55T under an existing cooperative research agreement between NHLBI and Siemens Healthcare.

Funding

NHLBI Division of Intramural Research, Z01-HL006213, Adrienne E. Campbell-Washburn, Z01-HL006257, Adrienne E. Campbell-Washburn

Abbreviations

- TSE

Turbo Spin-Echo

- SNR

Signal-to-noise ratio

- CNR

Contrast-to-noise ratio

- CPMG

Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill Sequence

- RMSE

Root mean square error

- RSS

Root sum square

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with the subject matter of the manuscript.

Ethical approval Imaging was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03331380) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10334-023-01103-0.

References

- 1.Campbell-Washburn AE, Ramasawmy R, Restivo MC, Bhattacharya I, Basar B, Herzka DA, Hansen MS, Rogers T, Bandettini WP, McGuirt DR, Mancini C, Grodzki D, Schneider R, Majeed W, Bhat H, Xue H, Moss J, Malayeri AA, Jones EC, Koretsky AP, Kellman P, Chen MY, Lederman RJ, Balaban RS (2019) Opportunities in interventional and diagnostic imaging by using high-performance low-field-strength MRI. Radiology 293(2):384–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wald LL, McDaniel PC, Witzel T, Stockmann JP, Cooley CZ (2020) Low-cost and portable MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 52(3):686–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarracanie M, LaPierre CD, Salameh N, Waddington DEJ, Witzel T, Rosen MS (2015) Low-cost high-performance MRI. Sci Rep 5(1):15177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat SS, Fernandes TT, Poojar P, da Silva FM, Rao PC, Hanumantharaju MC, Ogbole G, Nunes RG, Geethanath S (2021) Low-Field MRI of stroke: challenges and opportunities. J Magn Reson Imaging 54(2):372–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhattacharya I, Ramasawmy R, Javed A, Chen MY, Benkert T, Majeed W, Lederman RJ, Moss J, Balaban RS, Campbell-Washburn AE (2021) Oxygen-enhanced functional lung imaging using a contemporary 0.55 T MRI system. NMR Biomed 34 (8):e4562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Restivo MC, Ramasawmy R, Bandettini WP, Herzka DA, Campbell-Washburn AE (2020) Efficient spiral in-out and EPI balanced steady-state free precession cine imaging using a high-performance 0.55T MRI. Magn Reson Med 84 (5):2364–2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee NG, Ramasawmy R, Lim Y, Campbell-Washburn AE, Nayak KS (2022) MaxGIRF: Image reconstruction incorporating concomitant field and gradient impulse response function effects. Magn Reson Med 88(2):691–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King KF, Ganin A, Zhou XJ, Bernstein MA (1999) Concomitant gradient field effects in spiral scans. Magn Reson Med 41(1):103–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weavers PT, Tao S, Trzasko JD, Frigo LM, Shu Y, Frick MA, Lee SK, Foo TK, Bernstein MA (2018) B0 concomitant field compensation for MRI systems employing asymmetric transverse gradient coils. Magn Reson Med 79(3):1538–1544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou XJ, Tan SG, Bernstein MA (1998) Artifacts induced by concomitant magnetic field in fast spin-echo imaging. Magn Reson Med 40(4):582–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tao S, Weavers PT, Trzasko JD, Huston J 3rd, Shu Y, Gray EM, Foo TKF, Bernstein MA (2018) The effect of concomitant fields in fast spin echo acquisition on asymmetric MRI gradient systems. Magn Reson Med 79(3):1354–1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Javed A, Ramasawmy R, O’Brien K, Mancini C, Su P, Majeed W, Benkert T, Bhat H, Suffredini AF, Malayeri A, Campbell-Washburn AE (2022) Self-gated 3D stack-of-spirals UTE pulmonary imaging at 0.55T. Magn Reson Med 87 (4):1784–1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nunes RG, Malik SJ, Hajnal JV (2014) Single shot fast spin echo diffusion imaging with correction for non-linear phase errors using tailored RF pulses. Magn Reson Med 71(2):691–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Z, Karis JP, Pipe JG (2018) A 2D spiral turbo-spin-echo technique. Magn Reson Med 80(5):1989–1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Z, Srivastava SP, Karis JP (2021) Technical note: A spiral fluid-attenuated inversion recovery magnetic resonance imaging technique for stereotactic radiosurgery treatment planning for trigeminal neuralgia. Med Phys 48(11):6881–6888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hennig J, Barghoorn A, Zhang S, Zaitsev M (2022) Single shot spiral TSE with annulated segmentation. Magn Reson Med 88(2):651–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JH, Hargreaves BA, Hu BS, Nishimura DG (2003) Fast 3D imaging using variable-density spiral trajectories with applications to limb perfusion. Magn Reson Med 50(6):1276–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inati SJ, Naegele JD, Zwart NR, Roopchansingh V, Lizak MJ, Hansen DC, Liu CY, Atkinson D, Kellman P, Kozerke S, Xue H, Campbell-Washburn AE, Sorensen TS, Hansen MS (2017) ISMRM Raw data format: A proposed standard for MRI raw datasets. Magn Reson Med 77(1):411–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robson PM, Grant AK, Madhuranthakam AJ, Lattanzi R, Sodickson DK, McKenzie CA (2008) Comprehensive quantification of signal-to-noise ratio and g-factor for image-based and k-space-based parallel imaging reconstructions. Magn Reson Med 60(4):895–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marques JP, van Kemenade W, Gazzo S, Grodzki D, Knopp EA, Stainsby J (2021) ESMRMB annual meeting roundtable discussion: “when less is more: the view of MRI vendors on low-field MRI.” MAGMA 34(4):479–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y, Leong ATL, Zhao Y, Xiao L, Mak HKF, Tsang ACO, Lau GKK, Leung GKK, Wu EX (2021) A low-cost and shielding-free ultra-low-field brain MRI scanner. Nat Commun 12(1):7238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu HH, Lee JH, Nishimura DG (2008) MRI using a concentric rings trajectory. Magn Reson Med 59(1):102–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Z, Wang D, Robison RK, Zwart NR, Schar M, Karis JP, Pipe JG (2016) Sliding-slab three-dimensional TSE imaging with a spiral-In/Out readout. Magn Reson Med 75(2):729–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Z, Allen SP, Feng X, Mugler JP 3rd, Meyer CH (2022) SPRING-RIO TSE: 2D T(2) -Weighted Turbo Spin-Echo brain imaging using SPiral RINGs with retraced in/out trajectories. Magn Reson Med 88(2):601–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamir JI, Taviani V, Alley MT, Perkins BC, Hart L, O’Brien K, Wishah F, Sandberg JK, Anderson MJ, Turek JS, Willke TL, Lustig M, Vasanawala SS (2019) Targeted rapid knee MRI exam using T2 shuffling. J Magn Reson Imaging 49(7):e195–e204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song HK, Dougherty L (2000) k-space weighted image contrast (KWIC) for contrast manipulation in projection reconstruction MRI. Magn Reson Med 44(6):825–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fessler JA (2010) Model-Based Image Reconstruction for Mri. IEEE Signal Process Mag 27(4):81–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Middione MJ, Loecher M, Moulin K, Ennis DB (2020) Optimization methods for magnetic resonance imaging gradient waveform design. NMR Biomed 33(12):e4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilm BJ, Barmet C, Gross S, Kasper L, Vannesjo SJ, Haeberlin M, Dietrich BE, Brunner DO, Schmid T, Pruessmann KP (2017) Single-shot spiral imaging enabled by an expanded encoding model: Demonstration in diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med 77(1):83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen W, Sica CT, Meyer CH (2008) Fast conjugate phase image reconstruction based on a Chebyshev approximation to correct for B0 field inhomogeneity and concomitant gradients. Magn Reson Med 60(5):1104–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.