Abstract

Context:

Menstrual cycle synchronization is a phenomenon in which menstrual onset shifts progressively closer with time. It is an adoptive conditional phenomenon seen in the females who associate closely and share a common environment.

Aims:

To ascertain whether menstrual cycle synchrony exists in the roommates living in a closed space in a medical hostel.

Settings and Design:

This is a prospective observational study comprising 62 female medical students of a mean age of 22 years living in twin sharing accommodation with a history of regular menses (26–32 days).

Methods and Material:

These participants were followed on a monthly basis for 13 months. Menstrual cycle history was obtained using standardized Google forms. Menstrual cycle initial and final onset differences, expected cycle cut-off values, and absolute differences were calculated. The menstrual cycle synchrony score was obtained by subtracting the expected difference from the onset difference. Wilson's absolute difference method was used for determining menstrual synchrony between pairs.

Statistical Analysis Used:

The descriptive analysis was done using mean and standard deviation. One sample t-test was used to assess the synchrony between roommates. P value ≤0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results:

The initial onset difference of the menstrual cycle was 7.58 ± 4.25 days, whereas the final onset difference was 6.06 ± 3.92 days. The calculated synchrony score was -9.28 ± 5.05, which was statistically significant. Menstrual cycle synchrony was observed in 17 pairs (54.8%) and asynchrony in eight pairs (25.8%).

Conclusions:

Long-term association between roommates has potential to cause menstrual cycle synchrony. It has significant implications in reproductive medicine for reproductive scheduling and family planning.

Keywords: Female medical students, menstrual cycle, menstrual cycle synchrony, roommates

Introduction

Menstrual cycle synchronization, also known as McClintoc effect or menstrual concordance, is a phenomenon of convergence of the onset date of the menstrual flow in which menstrual onset shifts progressively closer with time. It is seen in the females who associate closely, such as living in the close proximity for a longer duration and sharing a common environment.[1,2]

The first scientific work on synchronization of menstrual cycles was reported by Martha McClintoc in 1971 in the college students living together in a dormitory for a long duration. These findings received a great deal of attention, and the accumulated scientific literature almost unequivocally continued to confirm the original findings of McClintoc.[1,2]

Menstrual synchrony is claimed to occur in specific settings and among certain groups of women who spend a significant amount of time together, such as room partners, close friends, and co-workers. It is an adoptive conditional phenomenon which is determined by the frequency and intensity of contact between women, degree of closeness, friendship, emotional attachment, individual hormonal status, common activities (similar eating and sleeping patterns and shared stress periods), and so on.[2,3,4,5,6]

Past studies have noted a significant decrease in the onset dates of the menstrual cycle in the pairs of female undergraduates living in a university campus, mothers and daughters living in their residence, the Suri Girls of Southwest Ethiopia, basket-ball players, sisters–roommates, and so on.[4,7,8,9,10]

Conversely, studies on cohabiting lesbian couples,[11] natural fertility populations,[12] Chinese women living in dorms for a long period, and so on have failed to statistically establish significant patterns of menstrual cycle synchrony.[11,12,13]

The conflicting results reported in the previous research studies might be due to the differences in the study environment, duration, sample size, age group of study subjects, use of oral contraceptives by the subjects, irregular cycle lengths, and so on. These variables are suggested in the past research as the probable underlying reasons for not observing the phenomenon of synchrony.[13,14,15]

Furthermore, it was reported in the past studies that the phenomenon is mediated by sensory communication between the women (olfactory, by pheromones, or by other senses) who can accelerate or delay the luteinizing hormone surge and thereby shortened or lengthened menstrual cycles. However, despite ongoing research, the cycle-altering pheromone has yet to be chemically identified and isolated.[5,6]

Till date, no decisive answer is available in the scientific literature for the mechanism underlying the phenomenon of menstrual synchrony; it remained an open question and subject of scholarly discussion. Furthermore, studies addressing this issue from the Indian population are hard to find in the literature.

Keeping all these factors into consideration, the present study aimed to find out whether the menstrual cycles of the female roommates synchronize or not over a period of time under near-optimal conditions conducive to menstrual synchrony.

The study hypothesizes that if menstrual cycle synchronization takes place, then the mean difference of menstrual onsets of the roommates gradually decreases with time.

Material and Methods

In this observational research study, a convenient sample comprising 70 female medical students of a mean age of 22 years with a history of regular menses (26–32 days) were enrolled. Eight participants were excluded from the study due to various reasons (irregular cycles, use of hormonal medications, not willing for participate in the study, etc). Date of ethical committee clearance was 31.03.2022, (No: 35/ IEC / NSCGMCK/2022 dated 01.04.2022).

The remaining 62 participants were paired in 31 hostel rooms on a twin sharing basis. Considering each room pair as a unit of closely interacting females, they were followed on a monthly basis consecutively for 13 months.

Data collection was done by the investigator of the project after obtaining ethical clearance from the institutional ethics committee (IEC) and written consent from the study participants.

Anthropometric measurements (weight and height) of the study participants were done using a standard protocol. Menstrual cycle history was obtained on a monthly basis using a standardized Google form-based proforma which comprises parameters like age of menarche, date of last menstrual period, date of onset of the next menstrual cycle and average duration, its regularity, duration of menstrual bleeding, and number of sanitary pads used.

Menstrual synchrony between roommates was determined as per the standard protocol proposed in the previous research studies.[13,14,16] Wilson's absolute difference method, which is considered as standard in this line of research, was used for determining menstrual synchrony between pairs: [A1-B1], [A1-B2], and [A2-B1]. Here, A and B represent the first and second girls of a pair; numbers 1 and 2 represent the first and second cycle onset dates, respectively. The initial onset difference of the menstrual cycle was calculated by selecting the smallest value from these three equations. The absolute onset difference was obtained by subtracting the final onset from the initial onset difference.[14] To obtain the expected difference in the menstrual cycle (i.e., cut-off value), the mean cycle length was determined, and it is divided by four.[13] The menstrual cycle synchrony score was obtained by subtracting the expected difference from the onset difference. If the final onset difference of a pair is significantly lower than the initial onset difference, it indicates menstrual synchrony in that pair.[16] One sample t-test was used to test synchrony score, where P value ≤ 0.05 indicates synchrony.[6]

Statistical analysis

The data collected from all the 31 pairs of the study participants were coded to keep the identities of the participants confidential and stored in the Microsoft Excel sheet.

The descriptive analysis was done using mean and standard deviation. One-sample t-test was used to assess the synchrony between roommates. A P value ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were performed on SPSS software.

Results

The demographic and menstrual characteristics of the study participants (n = 62) living in the hostel on a twin sharing basis for the entire study duration are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Anthropometric characteristics of study population

| Parameter | Mean±SD |

|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 22.27±2.04 |

| Weight (kg) | 53.51±12.93 |

| Height (cm) | 157.85±5.54 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.36±4.15 |

The mean age and weight of the of the study participants were 22.27 ± 2.04 (yrs) and 53.51 ± 12.93 (kg). Similarly, the height and body mass index were 157.85 ± 5.54 (cm) and 21.36 ± 4.15 (kg/m2), respectively.

Table 2 depicts menstrual onset differences at the beginning and at the end of the study. The initial onset difference of the menstrual cycle was 7.58 ± 4.25 days, whereas the final onset difference was 6.06 ± 3.92 days. The calculated synchrony score was -9.28 ± 5.05, which was statistically significant. A decrease in the difference between pairs' onset dates and synchrony score (negative value) was observed, clearly indicating a trend toward synchrony.

Table 2.

One-sample t-test for menstrual cycle synchrony assessment

| Menstrual Cycle differences | Mean±SD | t-statistic | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial onset difference | 7.58±4.25 | 9.916 | 0.000*** |

| Final onset difference | 6.06±3.92 | 8.606 | 0.000*** |

| Expected difference | 7.76±0.22 | 193.89 | 0.000*** |

| Synchrony score | -9.28±5.05 | 10.23 | 0.000*** |

***P-value highly significant <0.0001

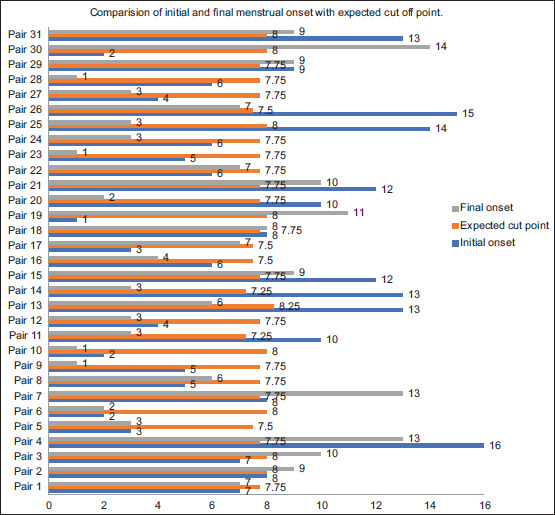

A comparison of the initial and final onsets of the menstrual cycle of the study pairs with cycle cut-off values is depicted in Figure 1. Menstrual cycle synchrony was observed in 18 pairs (54.8%), in which the final onset dates of the menstrual cycle converge toward the expected cycle cut-off value. On the contrary, in eight pairs (25.8%), the final onset difference was greater than the initial onset difference and the values diverge from the expected cycle cut point, indicating asynchrony.

Figure 1.

Comparison of initial and final menstrual onset with expected cut off point (in days)

Discussion

Existence of menstrual synchrony in humans is still an open and debatable question, and contrasting findings were reported in the previous studies regarding its existence in human beings.[2,3,4,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]

In this study, an attempt has been made to address this issue by quantitative examination of prospective onset differences of menstrual cycles to ascertain whether menstrual cycle synchrony exists in the roommates living in a closed space in a medical hostel.

This study is one of the few studies in which all the 31 pairs of girls sharing a common accommodation in the medical hostel were followed up consecutively for 13 months. The existence of menstrual cycle synchrony has been decided on the basis of three separate analyses of menstrual cycle onset differences as proposed by Wilson.[9,13,14,16,17]

The results of the study suggest 54.8% shift toward occurrence of menstrual cycle synchrony; the cycle onset dates in 18 pairs have converged toward the expected cycle cut-off value. The mean values of menstrual onset differences have decreased with time from 7.58 ± 4.25 days to 6.06 ± 3.92 days [Table 2]. These findings are in consonance with past studies, in which women living together in closed spaces have experienced a closer onset of menstrual cycles over a period of time.[1,2,3,4,7,8,9,10,16]

Ovarian-based pheromones were reported in the past studies as putative agents responsible for regulating the time of ovulation and lengthening or shortening of cycles.[3,6] These chemicals (3alpha-androstenol and 5alpha-androstenone) are present in the odors emanating from the axillary sweat of the roommates. Past research studies had noted that women who are synchronized have a higher sensitivity to 3alpha-androstenol as compared to non-synchronized women. The exposure to these pheromones is dependent on the frequency and intensity of contact between women, which in turn influences the cycle length.[8] Conversely, the synchronizing effect of pheromones gets weakened if their mid cycle exposure has been prevented, clearly highlighting the underlying role of pheromones in cycle synchrony.[3,5,6,14,18,19]

The results of the present study further indicate that out of the total 31 pairs studied, eight pairs (25.8%) did not show shift toward menstrual cycle synchrony, their final onset difference was greater than the initial onset difference, and the values diverge from the expected cycle cut point. It is possible that these girls had already synchronized with their close friends living in other rooms, to whom they were in frequent contact and spending more time with them. The past literature had reported that women who are close friends were significantly more synchronous than women who were not.[3,16] Since the amount of time that individuals spent together is determined by the level of friendship, it is a more significant factor in development of menstrual cycle synchrony rather than sharing a common accommodation.[14,16] Moreover, the interaction among close friends may produce synchronization of biological rhythms by increasing responsiveness of the individuals to the factors altering the timings of biological clocks.[19,20,21,22,23]

In the present study, the observed 54.8% shift toward occurrence of menstrual cycle synchrony clearly suggests that menstrual synchrony is an adoptive phenomenon which does occur in humans sharing a common accommodation over a period of time. The phenomenon is probably the result of exposure to pheromones present in the odors of the roommates and friends which are capable of changing the cycle length of the women. Furthermore, the phenomenon is dependent on the intensity and frequency of contact between the women, whether they share or not share the accommodation.[5,17,19]

However, more rigorously controlled research studies on larger databases which are equipped with new sophisticated methods of testing and new mathematical techniques for proper detection of synchrony are required. There is dire need to chemically isolate the cycle-altering pheromone to establish its decisive role in menstrual synchrony. This will permanently remove the scepticism and controversy revolving around the existence of menstrual cycle synchrony in humans.

Implications of the study

The present study may open new research avenues in reproductive medicine for the search of potential signals or candidates responsible for synchronization and timing of ovulation. This could have significant implications for reproductive scheduling and family planning. Moreover, it could have a positive impact on women's health, sexuality, well-being, and social status.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths: The long follow-up of 13 months and use of the novel analytical techniques to decide menstrual cycle synchrony have been the strengths of the present study, which increase the reliability of the results, eliminate the bias due to inherent variability in women's menstrual cycles, and minimize the chances of spurious finding of menstrual synchrony or no synchrony.

Limitations

The small sample size which is confined to the limited strata of female medical students' population is not a true representative of the entire population, and lack of data to assess the degree of friendship among these participants and cycle synchronization were among the limitations of this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.McClintock MK. Menstrual synchrony and suppression. Nature. 1971;229:244–5. doi: 10.1038/229244a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldman SE, Schneider HG. Menstrual synchrony: Social and personality factors. J Soc Behav Pers. 1987;2:243.. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham CA. Menstrual synchrony: An update and review. Hum Nat. 1991;2:293–311. doi: 10.1007/BF02692195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham CA, McGrew WC. Menstrual synchrony in female undergraduates living on a coeducational campus. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1980;5:245–52. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(80)90028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jahanfar S, Awang CH, Rahman RA, Samsuddin RD, See CP. Is 3alpha-androstenol pheromone related to menstrual synchrony? J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2007;33:116–8. doi: 10.1783/147118907780254042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ziomkiewicz A. Menstrual synchrony: Fact or artifact? Hum Nat. 2006;17:419–32. doi: 10.1007/s12110-006-1004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbink J. Menstrual synchrony claims among Suri Girls (Southwest Ethiopia). Between culture and biology. Cah Etud Afr. 2015;6:279–302. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weller L, Weller A, Avinir O. Menstrual synchrony: Only in roommates who are close friends? Physiol Behav. 1995;1(58):883–9. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)00142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weller A, Weller L. Menstrual synchrony under optimal conditions: Bedouin families. J Comp Psychol. 1997;111:143–51. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.111.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weller A, Weller L. Examination of menstrual synchrony among women basketball players. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1995;20:613–22. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00007-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trevathan WR, Burleson MH, Gregory WL. No evidence for menstrual synchrony in lesbian couples. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1993;18:425–35. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(93)90017-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strassmann BL. The biology of menstruation in Homo sapiens: Total lifetime menses, fecundity, and nonsynchrony in a natural fertility population. Curr Anthropol. 1997;38:123–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Z, Schank JC. Women do not synchronize their menstrual cycles. Hum Nat. 2006;17:433–47. doi: 10.1007/s12110-006-1005-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson HC. A critical review of menstrual synchrony research. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1992;17:565–91. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(92)90016-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morofushi M, Shinohara K, Funabashi T, Kimura F. Positive relationship between menstrual synchrony and ability to smell 5alpha-androst-16-en-3alpha-ol. Chem Senses. 2000;25:407–11. doi: 10.1093/chemse/25.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weller L, Weller A, Avinir O, Koresh-Kamin H, Ben-Shoshan R. Menstrual in a sample of working women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1999;24:449–59. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarrar N. Dirasat: Human and Social Sciences; 2020. Examining the Phenomenon of Menstrual Synchrony at an International Co-Educational Boarding High School in Jordan. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stern K, McClintock MK. Regulation of ovulation by human pheromones. Nature. 1998;392:177–9. doi: 10.1038/32408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weller L, Weller A. Human menstrual synchrony: A critical assessment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1993;27:427–39. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarett LR. Psychological and biological influences on menstruation: Synchrony, cycle length, and regularity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1984;9:21–8. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(84)90018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weller A, Weller L. Menstrual synchrony between mothers and daughters and between roommates. Physiol Behav. 1993;53:943–9. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90273-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Britto DR, Karthikeyan K, Rizvana AMS, Andrea D, Bruntha R, Chithruba KS. Menstrual synchrony-A questionnaire-based cross-sectional study among girls living in a hostel. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2022;9:2246–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haugen KK. A game theory explanation for menstrual synchrony: The harem paradox. Math Appl. 2022;11:33–43. [Google Scholar]