Abstract

What did the first cells on Earth look like? This is an unanswered mystery investigated by researchers in the origins of life field. While at some point cells must have developed membranes, genetic components, and catalytic cycles and catalysts, when the earliest cells developed these is not clear. One system which could shed light into the structure and function of the first cells on Earth is membraneless compartments generated from phase separation, perhaps before or as a precursor to the advent of membrane-bound compartmentalization. Here, we briefly comment on two prebiotically relevant membraneless compartment systems: coacervates and polyester microdroplets. This discussion seeks to highlight the current understanding of these systems and to pose unanswered questions as a challenge to the field at large.

Keywords: Phase separation, Origins of life, Protocells, Prebiotic chemistry, Membraneless compartments

Introduction

Comprehending how primitive cells assembled from the available chemistries on early Earth, and evolved into modern cells, is essential not only to understand the origins of life on Earth, but also may help to shed some much needed light to the historical evolution of modern cells. To this effect, research on primitive compartments, sometimes termed protocells, seeks to understand the structures and functions of such structures. A number of protocell models have been studied within the origins of life field, some of which are related to modern biological systems (such as lipid membrane vesicles or coacervates), and some of which are more deeply connected with the geologies and chemistries available on early Earth (such as mineral pores or polyester microdroplets) (Ghosh et al. 2021). In particular, membraneless compartments generated from phase separation can assemble from simple, prebiotically available polymers (such as peptides, nucleic acids, polyesters) while cellular compartments of similar structure are observed in extant biology in the form of membraneless organelles. This suggests that there may be a link between primitive membraneless compartments and modern membraneless organelles, which is a strong motivating factor to pursue this line of research. Here, we discuss how primitive membraneless compartments can lead to further understanding on the emergence and function of the first cells on Earth.

Coacervates

Complex coacervates are condensed phase droplets generated from binding of oppositely charged polyions, such as between oppositely charged peptides or between cationic peptides and nucleic acids with anionic backbones. Given that at some point in the emergence of life such peptides and nucleic acids necessarily existed and played a role in primitive living systems, it is not difficult to see the plausibility of complex coacervate assembly on an early Earth environment. As primitive compartments, complex coacervates provide a number of potential functions as a protocellular system including catalysis, growth, and compartmentalization (Ghosh et al. 2021). In particular, one area of current research with potential to provide more answers into the role of coacervates at the origins of life is understanding the limits of emergent complexity (including structural and functional complexity) exhibited in prebiotically relevant coacervates.

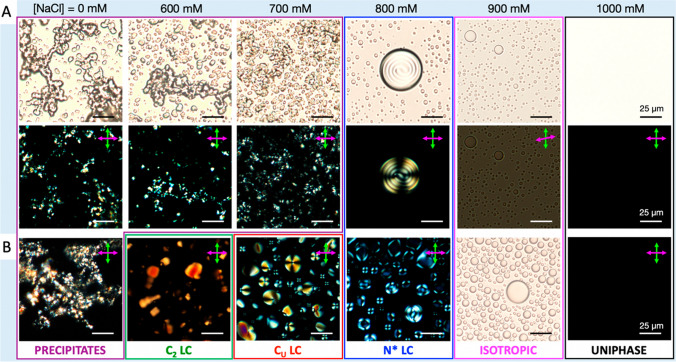

One such coacervate system is a peptide-DNA coacervate which increases structural complexity based on self-assembly of the DNA component. DNA oligomer duplexes and monomers of specific sequence and/or concentration can stack end-to-end to form long columnar rods which lead to assembly of supramolecular liquid crystals (LCs) (Fraccia et al. 2016). Researchers have sought to discover conditions which allow co-assembly of DNA LCs within a coacervate droplet (Fraccia and Jia 2020). Two components used in such coacervation studies are poly-l-lysine (PLL), a cationic peptide, and a short palindromic dsDNA sequence which exhibits LC assembly in bulk conditions (Fraccia and Jia 2020). Variation of the salinity after mixing of PLL and the dsDNA revealed that intermediate salinity conditions were most conducive to LC-coacervate co-assembly (Fraccia and Jia 2020). Annealing of the system resulted in emergence of even more structurally complex LC phases which can co-assemble with the coacervates (Fig. 1), and the DNA component was concentrated within the coacervates by up to three orders-of-magnitude (Jia and Fraccia 2020). In fact, modulation of the salinity and temperature of the system through dehydration/rehydration and further heating/cooling cycles allows the LC-coacervate to proceed unimpeded through all observed LC mesophases, suggesting that simple environmental changes indeed drive structural transitions. Subsequent elucidation of this system has even revealed that non-enzymatic DNA ligation can occur within the LC-coacervate interior, which further drives structural complexity transitions through emergence of multiphase LC-coacervates due to changes in DNA length (Fraccia and Martin 2023). Further demonstrations of coacervate function such as this one would serve to show the possibility of genotype–phenotype coupling (in this case, polymerization-structure coupling) in coacervate systems, which could serve to demonstrate the ability of coacervates to evolve, a critical step in the origins of life.

Fig. 1.

A Increasing salinity results in an LC-coacervate system progressing through different known LC and coacervate mesophases, with LC-coacervate colocalization at intermediate NaCl concentrations. B After annealing, emergence of even more structural complexity in the form of columnar LC-coacervate co-assemblies are observed at lower salinities. Reprinted with permission from (Fraccia and Jia 2020) under a creative commons license

Polyester microdroplets

While the coacervate system introduced above has roots in more biological systems (i.e., a more top-down design taking inspiration from prebiotically plausible biomolecules), there are also systems which are derived from more geochemical origins. Specifically, while it is known that biomolecules (such as amino acids or nucleotides) could have appeared on Earth through a variety of geochemical/environmental processes, such as spark discharge, meteoritic delivery, or UV irradiation, the same processes produced orthogonal molecules that do not play such a large role in modern biology (Chandru et al. 2020). One such type of “non-biological” molecule produced abundantly by such processes are alpha hydroxy acids (AHAs), which although can be occasionally seen as structural or metabolic components are not viewed as “essential” to life compared to central dogma-related biomolecules such as amino acids/peptides or nucleotides/nucleic acids. These AHAs can in fact polymerize through simple dehydration processes (on early Earth, this could be through evaporation) to produce polyester polymers. Initial studies showed that this primitive polyester synthesis process was applicable to a wide range of prebiotically plausible AHAs, and both homopolyesters and heteropolyesters could be produced when different mixtures/stoichiometries of AHAs were subjected to dehydration (Chandru et al. 2018).

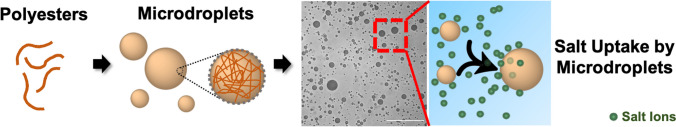

The ability of primitive AHAs and polyesters to assemble into primitive compartments has also been studied (Jia et al. 2019). Dehydration synthesis of AHAs to produce polyesters resulted in a gel-like product, further rehydration of which then led to the assembly of spherical membraneless polyester microdroplets (Jia et al. 2019). These microdroplets could coalesce upon increases in salinity, while also showing the ability to segregate a number of small organic dyes as well as certain biomolecules such as RNA. Further broadening of the AHA chemical complexity by introducing basic AHA residues into polyester chains resulted in a greater ability of the polyester microdroplets to segregate RNA, suggesting their potential to compartmentalize essential primitive genetic or catalytic biomolecules (Jia et al. 2021). The most recent advance in understanding of this system suggests that primitive polyester microdroplets can differentially uptake various salts, with certain cations (such as K+) preferred over others (Fig. 2) (Chen et al. 2023). While this mechanism is still under study, the salts were found to localize to the surface of the droplet membrane, neutralizing the generally negative surface charge, and driving further droplet coalescence and growth. Future work could focus on the coupling of environmental cycles of high salinity to drive droplet growth interspersed with periods of turbulence (such as through waves or underwater geophysical motion such as ocean currents) to effect droplet division which could lead to droplet recombination over time, potentially leading to further chemical evolution and the emergence of new droplet properties.

Fig. 2.

Microdroplets resulting from assembly of polyesters synthesized via dehydration of AHAs differentially uptake salts. Adapted/reprinted with permission from (Chen et al. 2023) under a creative commons license

Conclusion

While we have illustrated some unique properties of two prebiotically plausible membraneless compartment systems, there are still a number of functions of a wide variety of membraneless compartment systems that are yet to be discovered. In particular, did such compartments assist in the emergence or scaffolding of primitive membranes? In this case, perhaps primitive membraneless compartments could have acted as cytoplasmic mimics. In contrast, could the membraneless compartments have evolved independently of biological membranes, eventually being integrated into primitive cells (which evolved separately), leading to modern membraneless organelles? Such important questions are the subject of future study, the results of which will contribute to the understanding of how primitive membraneless compartments led to the first cells on Earth.

Acknowledgements

T.Z.J. is supported by JSPS Grant-in-aid 21K14746 and the Mizuho Foundation for the Promotion of Science. T.Z.J. thanks the 2023 Michèle Auger Award for Young Scientists’ Independent Research judging panel and Biophysical Reviews for providing an opportunity for this commentary.

Author contribution

T. Z. J. wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

No new data was generated in this study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Chandru K, Guttenberg N, Giri C, et al. Simple prebiotic synthesis of high diversity dynamic combinatorial polyester libraries. Commun Chem. 2018;1:30. doi: 10.1038/s42004-018-0031-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandru K, Mamajanov I, Cleaves HJ, II, Jia TZ. Polyesters as a model system for building primitive biologies from non-biological prebiotic chemistry. Life. 2020;10:6. doi: 10.3390/life10010006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Yi R, Igisu M et al (2023) Spectroscopic and biophysical methods to determine differential salt-uptake by primitive membraneless polyester microdroplets. Small Methods 2300119. 10.1002/smtd.202300119 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fraccia TP, Jia TZ. Liquid crystal coacervates composed of short double-stranded DNA and cationic peptides. ACS Nano. 2020;14:15071–15082. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c05083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraccia TP, Martin N. Non-enzymatic oligonucleotide ligation in coacervate protocells sustains compartment-content coupling. Nat Commun. 2023;14:2606. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38163-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraccia TP, Smith GP, Bethge L, et al. Liquid crystal ordering and isotropic gelation in solutions of four-base-long DNA oligomers. ACS Nano. 2016;10:8508–8516. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b03622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh B, Bose R, Tang T-YD. Can coacervation unify disparate hypotheses in the origin of cellular life? Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2021;52:101415. doi: 10.1016/j.cocis.2020.101415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia TZ, Fraccia TP. Liquid crystal peptide/DNA coacervates in the context of prebiotic molecular evolution. Crystals. 2020;10:964. doi: 10.3390/cryst10110964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia TZ, Chandru K, Hongo Y, et al. Membraneless polyester microdroplets as primordial compartments at the origins of life. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:15830–15835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1902336116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia TZ, Bapat NV, Verma A, et al. Incorporation of basic α-hydroxy acid residues into primitive polyester microdroplets for RNA segregation. Biomacromol. 2021;22:1484–1493. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.0c01697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was generated in this study.