Summary

China has hundreds of millions of children and adolescents aged 10–24 years, accounting for one-sixth of their total counterparts worldwide. We perform this study to clarify the priority of noncommunicable disease (NCD) control among youth in China via the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2019. The highest disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) from NCDs among youth in China remain in mental disorders, while the most increasing incidence is from diabetes and kidney diseases during 1990–2019. Bullying victimization and high BMI are the top risk factors for DALYs from mental disorders and diabetes mellitus, respectively. The most substantial gender differences are found for alcohol use disorders among the 20–24 age subgroup, which is also the top risk factor for neoplasm DALYs. Targeted interventions for NCDs among youth in China should focus on high body mass, alcohol usage, and bullying victimization, providing crucial information for resource-limited settings across the world.

Keywords: non-communicable diseases, global burden of diseases, adolescents, China, mental disorders, diabetes mellitus, high body mass, alcohol usage, bullying victimization, disability-adujusted life years

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

China has one-sixth of the youths in the world

-

•

Mental disorders cause the highest DALYs from NCDs in this population

-

•

Diabetes mellitus had the largest increase in incidence of NCDs in this population

-

•

Top risk factors included high body mass, alcohol usage, and bullying victimization

Zhang et al. clarify that mental disorders, diabetes, and kidney disease as priorities of noncommunicable disease (NCD) control among youth in China and identify high body mass, alcohol usage, and bullying as top risk factors for disability-adjusted life years from NCDs among this population.

Introduction

In 2019, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) accounted for 74% of all deaths globally.1 Additionally, NCDs, known as chronic diseases, tend to be of long duration and are the result of a combination of genetic, physiological, environmental, and behavioral factors. Children and adolescents are most sensitive and vulnerable to these factors. From the life course perspective, the early onset of NCDs in children and adolescents also impacts the risk of adverse health outcomes and healthcare costs in adulthood.2

As one of the most populated countries, China has hundreds of million children and adolescents aged 10–24 years.3 In recent decades, China has reduced death from communicable diseases by 68.7% among children and adolescents.4 Additionally, in recent decades, China has experienced rapid social transformation, urbanization, and globalization, leading to widespread risk factors for NCDs such as inactivity, sedentary lifestyle, and smartphone addiction among the youth. The prevalence of diabetes in all populations in China has exceeded 10%, and the average age of patients has become younger.5 There are 15.6% preschool-aged children and 31.8% school-aged children predicted to be overweight or obese in China, which will lead to US $61 billion in medical costs in 2030.6 After COVID-19, China continued to prioritize tackling the large burden of NCDs among its population.7,8 Additionally, NCD control requires early intervention, especially targeting its early onset among the young population. However, the lack of analysis on the priority and trends of NCDs in children and adolescents in China hinders future interventions and policies.

This study aimed to clarify the specific priorities in NCDs with the highest speed of increasing incidence, the highest disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), and the largest mortality in children and adolescents aged 10–24 years in China from 1990 to 2019. We aimed to stratify the above burden by gender and age subgroups and analyze their contributing risk factors.

Results

DALYs from NCDs and the trend

In 2019, NCDs were the leading level 1 causes of DALYs among adolescents aged 10–24 years in China, with 12.10 million (95% confidence interval [CI] 9,281,284–15,404,688) cases (Table S1). In 2019, the top three level 2 causes of DALYs from NCDs in adolescents in China were mental health (1,173.68, 95% uncertainty interval [UI] 832.99–1591.16), skin and subcutaneous diseases (769.13 [493.96–1,148.77]), and neurological disorders (629.63 [223.30–1,247.90]) (Table 1). The top three level 3 causes of DALYs from NCDs were headache disorder (469.72 [95% CI 57.9–1,093.03]), anxiety disorders (405.73 [268.22–588.56]), and lower back pain (390.11 [246.73–585.81]) (Table S2).

Table 1.

The disability-adjusted years, incidence, and mortality of level 1 and level 2 NCDs and their average annual percentage changes among children and adolescents in China from 1990 to 2019

| Cases in 1990 (95% UI) | Rate in 1990 (95% UI, per 100,000 population) | Cases in 2019 (95% UI) | Rate in 2019 (95% UI, per 100,000 population) | AAPC in rate, 1990–2019 (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DALYs from level 1 NCDs | 23,489,731 (18,689,221–29,113,737) | 6,487.86 (5,161.96–8,041.20) | 12,104,572 (9,281,284–15,404,688) | 5,317.01 (4,076.86–6,766.61) | −0.79 (−0.86 to −0.73) | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 11,515,587 (9,301,768–13,999,766) | 6,194.47 (5,003.61–7,530.76) | 6,121,685 (4,751,218–7,610,361) | 5,051.57 (3,920.67–6,280.02) | −0.83 (−0.90 to −0.75) | <0.001 |

| Female | 11,974,144 (9,309,539–15,187,814) | 6,797.47 (5,284.83–8,621.81) | 5,982,887 (4,498,393–7,745,420) | 5,619.12 (4,224.88–7,274.48) | −0.75 (−0.82 to −0.69) | <0.001 |

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| 10–14 | 48,089,14 (3,774,942–6,032,808) | 4,679.07 (3,673.02–5,869.92) | 2,795,547 (2,106,992–3,605,162) | 3,956.67 (2,982.12–5,102.55) | −0.73 (−0.82 to −0.63) | <0.001 |

| 15–19 | 8,188,926 (6,542,180–10,175,854) | 6,453.96 (5,156.11–8,019.92) | 3,981,507 (3,015,947–5,147,407) | 5,299.05 (4,013.97–6,850.77) | −0.87 (−0.94 to −0.80) | <0.001 |

| 20–24 | 10,491,892 (8,301,087–12,916,809) | 7,924.40 (6,269.71–9,755.92) | 5,327,517 (4,098,564–6,662,146) | 6,507.51 (5,006.35–8,137.74) | −0.97 (−1.08 to −0.85) | <0.001 |

| DALYs from level 2 NCDs | ||||||

| Cardiovascular diseases | 1,822,609 (1,570,734–2,087,024) | 503.40 (433.84–576.44) | 671,481 (571,309–767,777) | 294.95 (250.95–337.25) | −1.82 (−2.01 to −1.62) | <0.001 |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | 797,506 (612,290–1,011,663) | 220.27 (169.11–279.42) | 329,451 (238,021–466,789) | 144.71 (104.55–205.04) | −2.08 (−2.44 to −1.73) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes and kidney diseases | 643,812 (556,465–741,407) | 177.82 (153.70–204.78) | 224,651 (184,390–273,010) | 98.68 (80.99–119.92) | −1.45 (−1.63 to −1.26) | <0.001 |

| Digestive diseases | 778,143 (662,784–922,147) | 214.92 (183.06–254.70) | 200,606 (156,328–257,332) | 88.12 (68.67–113.03) | −3.49 (−3.65 to −3.33) | <0.001 |

| Mental disorders | 4,719,896 (3,377,636–6,390,010) | 1,303.63 (932.9–1,764.92) | 2,671,972 (1,896,369–3,622,406) | 1,173.68 (832.99–1,591.16) | −0.44 (−0.47 to −0.41) | <0.001 |

| Musculoskeletal disorders | 2,113,553 (1,413,752–3,016,756) | 583.76 (390.48–833.23) | 1,345,113 (913,722–1,909,373) | 590.85 (401.36–838.70) | 0.14 (−0.01 to 0.29) | 0.06 |

| Neoplasms | 2,432,037 (2,081,533–2,788,113) | 671.73 (574.92–770.08) | 985,129 (855,145–1,116,674) | 432.72 (375.63–490.51) | −1.99 (−2.22 to −1.75) | <0.001 |

| Neurological disorders | 2,327,037 (953,471–4,399,919) | 642.73 (263.35–1,215.26) | 1,433,387 (508,367–2,840,949) | 629.62 (223.30–1,247.90) | −0.11 (−0.19 to −0.04) | 0.004 |

| Other NCDs | 2,907,415 (2,202,796–3,860,706) | 803.03 (608.41–1,066.33) | 1,317,972 (976,169–1,779,946) | 578.93 (428.79–781.85) | −1.18 (−1.23 to −1.13) | <0.001 |

| Sense organ diseases | 893,610 (551,539–1,281,439) | 246.81 (152.33–353.93) | 556,185 (352,376–796,597) | 244.31 (154.78–349.91) | −0.09 (−0.25 to 0.07) | 0.25 |

| Skin and subcutaneous diseases | 2,570,766 (1,655,172–3,820,287) | 710.04 (457.16–1,055.16) | 1,750,987 (1,124,537–2,615,268) | 769.13 (493.96–1,148.77) | 0.26 (0.22–0.30) | <0.001 |

| Substance use disorders | 1,483,347 (1,122,307–1,876,612) | 409.70 (309.98–518.32) | 617,638 (424,575–842,131) | 271.30 (186.50–369.91) | −1.88 (−2.13 to −1.62) | <0.001 |

| Incidence of level 1 NCDs | 488,311,068 (444,365,351–530,660,101) | 134,871.34 (122,733.55–146,568.13) | 307,135,729 (279,004,570–333,584,045) | 134,911.29 (122,554.50–146,528.88) | 0.02 (−0.01 to 0.04) | 0.19 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 232,572,674 (210,740,094–253,858,748) | 125,105.60 (113,361.41–136,555.81) | 152,112,778 (137,827,486–166,104,925) | 125,522.44 (113,734.31–137,068.66) | 0.02 (−0.01 to 0.05) | 0.15 |

| Female | 25,5738,394 (233,026,837–277,791,496) | 145,177.35 (132,284.47–157,696.43) | 155,022,951 (141,586,132–168,127,912) | 145,597.26 (132,977.43–157,905.42) | 0.02 (0.00–0.05) | 0.03 |

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| 10–14 | 132,157,866 (107,785,083–159,593,933) | 128,589.53 (104,874.83–155,284.81) | 90,543,687 (72,297,782–110,420,845) | 128,150.72 (102,326.43–156,283.79) | −0.02 (−0.05 to 0.01) | 0.18 |

| 15–19 | 164,620,765 (144,387,123–183,778,458) | 129,742.99 (113,796.19–144,841.79) | 98,897,806 (87,190,435–110,234,906) | 1316,24.68 (116,043.15–146,713.41) | 0.03 (0.02–0.04) | <0.001 |

| 20–24 | 191,532,438 (174,920,276–207,250,571) | 144,662.22 (132,115.25–156,533.95) | 117,694,237 (108,838,777–127,504,928) | 143,762.27 (132,945.42–155,745.93) | −0.03 (−0.05 to −0.01) | <0.001 |

| Incidence of level 2 NCDs | ||||||

| Cardiovascular diseases | 323,565 (250,098–404,369) | 89.37 (69.08–111.69) | 169,483 (131,015–211,289) | 74.45 (57.55–92.81) | −0.58 (−0.74 to −0.41) | <0.001 |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | 1,196,342 (803,816–1,688,498) | 330.43 (222.01–466.36) | 698,974 (452,443–1,011,631) | 307.03 (198.74–444.37) | −1.79 (−2.29 to −1.30) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes and kidney diseases | 356,034 (276,706–452,949) | 98.34 (76.43–125.10) | 275,321 (212,140–351,983) | 120.94 (93.18–154.61) | 2.64 (1.95–3.32) | <0.001 |

| Digestive diseases | 6,945,542 (5,711,802–8,521,688) | 1,918.36 (1,577.60–2,353.69) | 4,117,366 (3,379,196–5,036,845) | 1,808.58 (1,484.33–2,212.47) | −0.03 (−0.15 to 0.08) | 0.55 |

| Mental disorders | 1,389,0880 (11,535,137–16,782,761) | 3,836.66 (3,186.00–4,635.39) | 6,908,606 (5,874,407–8,198,869) | 3,034.65 (2,580.37–3,601.40) | −1.03 (−1.14 to −0.91) | <0.001 |

| Musculoskeletal disorders | 7,335,029 (5,625,579–9,336,562) | 2,025.93 (1,553.78–2,578.76) | 4,321,186 (3,335,637–5,493,611) | 1,898.11 (1,465.20–2,413.10) | −0.28 (−0.43 to −0.13) | 0.001 |

| Neoplasms | 5,192,235 (3,411,495–7,274,140) | 1,434.09 (942.25–2,009.11) | 2,878,109 (1,984,113–3,967,231) | 1,264.23 (871.53–1,742.63) | −0.47 (−0.55 to −0.39) | <0.001 |

| Neurological disorders | 31,566,360 (25,079,204–38,736,012) | 8,718.62 (6,926.87–10,698.87) | 21,226,822 (16,997,197–2,581,7391) | 9,324.01 (7,466.12–11,340.45) | 0.27 (0.22–0.32) | <0.001 |

| Other NCDs | 23,8545,047 (199,257,673–274,980,310) | 65,886.06 (55,034.90–75,949.46) | 149,323,697 (125,205,712–172,258,507) | 65,591.37 (54,997.39–75,665.63) | 0.01 (−0.03 to 0.04) | 0.71 |

| Sense organ diseases | 0 (0–0) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0 (0–0) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | N/A | N/A |

| Skin and subcutaneous diseases | 180,215,061 (163,286,075–198,583,881) | 49,775.34 (45,099.56–54,848.80) | 11,5728,845 (105,316,476–127,136,317) | 50,834.62 (46,260.92–55,845.42) | 0.09 (0.08–0.10) | <0.001 |

| Substance use disorders | 2,744,973 (2,155,776–3,569,043) | 758.16 (595.42–985.77) | 1,487,320 (1,164,994–1,900,113) | 653.31 (511.73–834.64) | −0.66 (−0.87 to −0.44) | <0.001 |

| Mortality from level 1 NCDs | 100,278 (87,171–114,158) | 27.75 (24.08–31.53) | 32,610 (28,280–37,320) | 14.32 (12.42–16.39) | −2.71 (−2.91 to −2.50) | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 59,276 (48,872–68,977) | 31.89 (26.29–37.10) | 20,986 (17,463–25,104) | 17.32 (14.41–20.72) | −2.43 (−2.60 to −2.26) | <0.001 |

| Female | 41,002 (34,104–49,417) | 23.28 (19.36–28.05) | 11,624 (9,585–13,818) | 10.92 (9.00–12.98) | −3.11 (−3.44 to −2.77) | <0.001 |

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| 10–14 | 18,126 (16,199–20,178) | 17.64 (15.76–19.63) | 5,530 (4,910–6,219) | 7.83 (6.95–8.80) | −3.15 (−3.51 to −2.78) | <0.001 |

| 15–19 | 35,911 (30,874–40,870) | 28.30 (24.33–32.21) | 10,032 (8,688–11,558) | 13.35 (11.56–15.38) | −3.08 (−3.28 to −2.89) | <0.001 |

| 20–24 | 46,241 (39,236–53,475) | 34.93 (29.63–40.39) | 17,048 (14,571–19,752) | 20.82 (17.80–24.13) | −2.56 (−2.91 to −2.22) | <0.001 |

| Mortality from level 2 NCDs | ||||||

| Cardiovascular diseases | 22,279 (18,865–25,897) | 6.15 (5.21–7.15) | 7,443 (6,219–8,742) | 3.27 (2.73–3.84) | −2.18 (−2.39 to −1.97) | <0.001 |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | 4,493 (3,144–5,399) | 1.24 (0.87–1.49) | 577 (487–702) | 0.25 (0.21–0.31) | −6.03 (−6.31 to −5.76) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes and kidney diseases | 7,050 (6,053–8,114) | 1.95 (1.67–2.24) | 1,755 (1,506–2,024) | 0.77 (0.66–0.89) | −3.62 (−3.88 to −3.37) | <0.001 |

| Digestive diseases | 7,274 (6,207–8,473) | 2.01 (1.71–2.34) | 1,144 (972–1,333) | 0.50 (0.43–0.59) | −5.47 (−5.69 to −5.25) | <0.001 |

| Mental disorders | 5 (3–9) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 9 (7–11) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 3.63 (3.09–4.17) | <0.001 |

| Musculoskeletal disorders | 991 (817–1,503) | 0.27 (0.23–0.42) | 648 (486–793) | 0.28 (0.21–0.35) | 0.28 (−0.19 to 0.76) | 0.24 |

| Neoplasms | 33,928 (29,010–38,914) | 9.37 (8.01–10.75) | 13,572 (11,734–15,445) | 5.96 (5.15–6.78) | −2.00 (−2.23 to −1.78) | <0.001 |

| Neurological disorders | 6,177 (5,207–7,138) | 1.71 (1.44–1.97) | 2,299 (1,971–2,729) | 1.01 (0.87–1.20) | −2.24 (−2.45 to −2.03) | <0.001 |

| Other NCDs | 11,644 (10,095–13,323) | 3.22 (2.79–3.68) | 3,952 (3,451–4,562) | 1.74 (1.52–2.00) | −2.58 (−2.87 to −2.30) | <0.001 |

| Sense organ diseases | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Skin and subcutaneous diseases | 279 (148–339) | 0.08 (0.04–0.09) | 42 (35–59) | 0.02 (0.02–0.03) | −6.13 (−6.68 to −5.59) | <0.001 |

| Substance use disorders | 6,159 (5,199–7,189) | 1.70 (1.44–1.99) | 1,168 (963–1,390) | 0.51 (0.42–0.61) | −6.33 (−7.16 to −5.51) | <0.001 |

During 1990–2019, the DALYs from NCDs decreased from 6,487.86 (95% UI 5,161.96–8,041.20) to 5,317.01 (4,076.86–6,766.61) per 100,000 population (average annual percent change [AAPC] −0.79 [95% CI −0.86 to −0.73]) (Table 1). This decreasing rate was less than one-third of the decreasing rate in communicable diseases among the same population during the same period (AAPC −0.79 [95% CI −0.86 to −0.73] vs. AAPC −2.54 [−2.82 to −2.25]) (Table S1). The largest decreases in level 2 causes for DALYs were found in digestive diseases (AAPC −3.49 [95% CI −3.65 to −3.33]), with the largest reduction in level 3 causes as cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases (AAPC −4.93 [−5.12 to −4.74]). The second largest decrease in level 2 causes for DALYs was found in chronic respiratory diseases (AAPC −2.08 [95% CI −2.44 to −1.73]), with the largest reduction in level 3 causes of pneumoconiosis (AAPC −5.27 [−5.47 to −5.07]). The only substantial increases in level 2 causes for DALYs from NCDs were found in skin and subcutaneous diseases (AAPC 0.26 [95% CI 0.22–0.30]) (Tables 1 and S2).

Incidence of NCDs and the trend

In 2019, there were 307.14 million (95% CI 279,004,570 to 333,584,045) incident cases of NCDs among individuals aged 10–24 years in China (Table S1). The leading level 2 NCD causes of incidence in 2019 were skin and subcutaneous diseases (5,0834.62 [95% CI 46,260.92–55,845.42]), neurological disorders (9,324.01 [7,466.12–11,340.45]), and mental disorders (3,034.65 [2,580.37–3,601.40]) except for other NCDs (Table 1). The most incident level 3 NCD causes in each category were scabies (16,397.91 [95% CI 12,946.91–20,522.15]), headache disorder (9,299.28 [7,446.13–11,311.13]), and depressive disorders (1,595.53 [1,230.34–2,051.45]), respectively (Table S3). The top three NCD level 3 causes of the incident in 2019 were oral disorders (58,011.28 [95% CI 47,245.65–67,898.00], including caries of deciduous teeth, caries of permanent teeth, chronic periodontal disease, and other oral disorders), scabies (16,397.91 [12,946.91–20,522.15]), and fungal skin diseases (10,147.73 [7,857.61–13,078.76]), followed by headache disorders (9,299.28 [7,446.13–11,311.13]) (Table S3).

During 1990–2019, no substantial trend in the incidence of NCDs was observed (from 13,4871.34 [95% UI 122,733.55–146,568.13] in 1990 to 134,911.29 [122,554.50 to 146,528.88] per 100,000 population in 2019 with AAPC 0.02 [95% CI −0.01 to 0.04]), while the incidence of communicable disease significantly decreased (AAPC −0.05 [−0.07 to −0.03]) (Table S1). The largest increase in level 2 causes for incidence of NCDs was diabetes and kidney diseases (AAPC 2.64 [95% CI 1.95–3.32]), and the largest increase in level 3 causes was diabetes mellitus (AAPC 3.83 [2.96–4.71]). The largest decreases in level 2 causes for the incidence of NCDs were found in chronic respiratory diseases (AAPC −1.79 [95% CI −2.29 to −1.30]) (Tables 1 and S3).

Although the incidence of total neoplasms decreased (AAPC −0.47 [95% CI −0.55 to −0.39]), the incidence of testicular cancer (AAPC 5.82 [5.49–6.15]), kidney cancer (AAPC 4.69 [4.09–5.30]), malignant skin melanoma (AAPC 4.50 [4.19–4.80]), and multiple myeloma (AAPC 4.06 [3.34–4.78]) substantially increased (Tables 1 and S3).

Mortality from NCDs and the trend

In 2019, there were 32,610 (95% UI 28,280–37,320) mortality cases of NCDs among individuals aged 10–24 years in China, accounting for 37.23% of the total mortality in these age groups (Table S1). The leading level 2 NCD cause of mortality in individuals aged 10–24 years in China in 2019 was neoplasms (5.96, 95% UI 5.15–6.78), with the top level 3 cause being leukemia (2.04 [1.65–2.37]) (Table S4).

During 1990–2019, the mortality from NCD substantially decreased in adolescents in China from 27.75 (95% UI 24.08–31.53) to 14.32 (12.42–16.39) per 100,000 population (AAPC −2.71 [95% CI −2.91 to −2.50]) (Table 1). Its decreasing rate was half the decreasing rate in communicable diseases among the same population during the same period (AAPC −2.71 [95% CI −2.91 to −2.50] vs. AAPC −6.34 [−6.69 to −5.99]) (Table S1). Mortality from neoplasms decreased (AAPC −2.00 [95% CI −2.23 to −1.78]), but several cancers had substantially increased mortality, including multiple myeloma (AAPC 2.95 [2.21–3.70]) and kidney cancer (AAPC 2.09 [1.61–2.56]). The largest decreases in level 2 causes for mortality were found in substance use disorders (AAPC −6.33 [95% CI −7.16 to −5.51]), with the greatest reduction in drug use disorder (AAPC −8.25 [−9.34 to −7.16]). The only increase in level 2 causes for mortality was found in mental disorders (AAPC 3.63 [95% CI 3.09–4.17]), specifically eating disorders (AAPC 3.63 [3.09–4.17]) (Table S4).

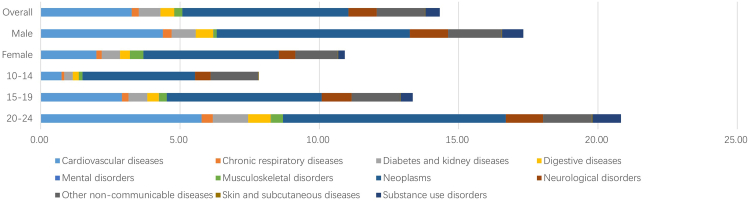

Age differences in NCDs

In 2019, young adults aged 20–24 years had the highest DALYs from NCDs (6,507.51 [95% UI 5,006.35–8,137.74]) and the highest incidence of NCDs (143,762.27 [132,945.42–155,745.93]) (Table 1). Notably, mental disorders were the leading level 2 causes for DALYs in all age groups (Table S5), specifically anxiety disorders (438.54 [95% CI 276.70–641.52]) in younger adolescents aged 10–14 years and headache disorders in adolescents aged 15–19 years (493.07 [62.90–1,192.43]) and in young adults aged 20–24 years (588.38 [92.33–1,340.60]) (Figure 1; Table S6). Those aged 20–24 years had the highest incidence and mortality of NCDs in 2019 (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

DALYs from NCDs by age subgroups and genders among children and adolescents aged 10–24 years in China in 2019

Figure 2.

Incidence of NCDs by age subgroups and genders among children and adolescents aged 10–24 years in China in 2019

Figure 3.

Mortality from NCDs by age subgroups and genders among children and adolescents aged 10–24 years in China in 2019

From 1990 to 2019, the DALYs from NCDs decreased in all age subgroups. However, the incidence of NCDs increased only in adolescents aged 15–19 years old, with an AAPC of 0.03 (95% CI 0.02–0.04), but decreased in young adults aged 20–24 years (−0.03 [−0.05 to −0.01]) (Table 1).

Gender differences in NCDs

In 2019, females had both higher DALYs from NCDs per 100,000 population than males (5,619.12 [95% UI 4,224.88–7,274.48] vs. 5,051.57 [3,920.67–6,280.02]) and a higher incidence of NCDs than males (145,597.26 [132,977.43–157,905.42] vs. 125,522.44 [113,734.31–137,068.66]) (Table 1). During 1990–2019, females had a smaller reduction in DALYs from NCD than males (AAPC −0.75 [95% CI −0.82 to −0.69] vs. AAPC −0.83 [−0.90 to −0.75]) (Table 1). In 2019, the gender differences of DALYs were most substantial in adolescents aged 20–24 years in terms of alcohol use disorders (males: 266.91 [95% CI 167.57–406.10] vs. females: 60.40 [34.96–98.89]) and headache disorders (males: 457.99 [89.79–1,020.91] vs. females: 731.00 [93.27–1,704.41]) (Table S7).

Risk factors

The leading risk factors at the most detailed level for DALY rates of diabetes mellitus, mental disorders, and neoplasms among adolescents in China during 1990–2019 were analyzed. For DALYs from diabetes mellitus in 2019, high fasting plasma glucose and high BMI contributed 34.88 (95% CI 25.12–49.18) and 7.50 (2.31–15.86) per 100,000 population, respectively, increasing with AAPCs of 1.41 (0.88–1.94) and 6.22 (5.09–7.36) between 1990 and 2019, respectively. For DALYs from neoplasms in 2019, high BMI and alcohol use contributed 3.72 (95% CI 1.16–7.67) and 4.68 (3.40–6.33) per 100,000 population, respectively. For DALYs for mental disorders in 2019, bullying victimization contributed 97.63 (95% CI 33.71–192.37) per 100,000 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Top three leading risk factors at the most detailed level for DALY rates of diabetes mellitus, mental disorders, and neoplasms among adolescents in China, 1990–2019

| Rank | Leading risk 1990 | DALYs rate, 1990 | Rank | Leading risk 2019 | DALYs rate, 2019 | AAPCs in DALYs rate, 1990–2019 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus | |||||||

| 1 | high fasting plasma glucose | 37.41 (29.2–48.63) | 1 | high fasting plasma glucose | 34.88 (25.12–49.18) | 1.41 (0.88–1.94) | <0.001 |

| 2 | high BMI | 3.11 (0.49–8.03) | 2 | high BMI | 7.50 (2.31–15.86) | 6.22 (5.09–7.36) | <0.001 |

| 3 | low temperature | 1.85 (0.84–2.85) | 3 | low temperature | 0.98 (0.47–1.53) | −2.59 (−2.82 to −2.36) | <0.001 |

| Mental disorders | |||||||

| 1 | bullying victimization | 106.58 (34.08–220.01) | 1 | bullying victimization | 97.63 (33.71–192.37) | −0.50 (−0.73 to −0.27) | <0.001 |

| 2 | lead exposure | 25.73 (10.43–46.63) | 2 | lead exposure | 12.92 (4.24–25.06) | −2.57 (−2.66 to −2.48) | <0.001 |

| 3 | intimate partner violence | 16.55 (0.04–44.42) | 3 | intimate partner violence | 8.63 (0.02–23.21) | −1.45 (−2.26 to −0.62) | 0.002 |

| Neoplasms | |||||||

| 1 | alcohol use | 6.41 (4.31–8.90) | 1 | high BMI | 3.72 (1.16–7.67) | 0.94 (0.43–1.45) | 0.001 |

| 2 | unsafe sex | 5.22 (4.02–6.86) | 2 | alcohol use | 4.68 (3.40–6.33) | −1.59 (−2.33 to −0.83) | <0.001 |

| 3 | high BMI | 2.77 (0.42–7.32) | 3 | unsafe sex | 3.18 (1.83–4.13) | −1.51 (−1.73 to −1.28) | <0.001 |

Discussion

This study identified the priority and major risk factors in NCD control among children and adolescents aged 10–24 years in China. In 2019, NCDs caused nearly 70% DALYs in this population. The highest DALYs from NCDs were caused by mental disorders in both genders and every age subgroup of youth in China, while bullying victimization was a major contributor. The highest mortality from NCDs was identified in neoplasms, especially leukemia. The most rapidly increasing incidence was found in diabetes and kidney diseases during 1990–2019. High BMI was the top two risk factor for DALYs from diabetes and neoplasms, and alcohol use disorders was the top risk factor for neoplasm DALYs.

Compared with the NCD burden of their counterparts in other countries and regions, youth in China were bearing much higher DALYs from NCDs.9 Compared to communicable disease control in China, the DALYs from NCDs among youth in China decreased from 1990 to 2019 but with only one-third of the decreasing rate of communicable diseases. Compared to the US CDC, the other largest center for disease control and prevention in the world, the total number of people served by the China CDC for NCDs is 4.2 times that of the other center, but the number of staff is only 1/25 (60/1,500), and the investment is only 1/107.10 Although China has successfully improved the chronic disease prevention and control strategies implementation, largely reducing DALYs from cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases in China, the challenges are still large in future.

Mental disorders contributed the highest DALYs from NCDs among youth in China. While China is experiencing the most rapid social and economic changes, its children and adolescents are the most vulnerable and impacted, both physically and mentally. According to the Report on the Development Plan for National Mental Health in China 2021–2022, depression and loneliness are prevalent, with approximately 15% adolescents aged 10–16 years in China having varying degrees of depression risk, and the prevalence increases with grade. A majority of them have smartphone addiction.11 This report also revealed that the mental disorders among children and adolescents in less developed and rural areas are slightly higher, indicating that achieving educational equity and resource allocation fairness is crucial for mental health problems. There are several reasons behind this phenomenon. The rapid urbanization and economic growth in China have caused 171.7 million rural parents to migrate into urban cities seeking employment, making up an estimated 36% of China’s entire workforce and leading to 7.0 million left-behind children in rural areas and 13.7 million migrant children.12,13 On the other hand, parents in cities focus heavily on their school-age children’s scholastic performance. Both of these parental phenomena provide a breeding ground for victims and bullying. The prevalence of school bullying among adolescents was 33.5%, and from most to least, they are as follows: verbal, relational, and physical bullying.14 Harsh parental discipline positively predicted school bullying among Chinese adolescents.14 There have been efforts invested into the mental health of children and adolescents in China, including the national implementation of the “double reduction policy” (meaning easing both the burden of excessive homework and off-campus tutoring for students). The mental health assessment of primary and secondary school students is being standardized and normalized at least once a year in China, and more training and attention are being provided to school leaders and teachers, helping them understand, adjust to, and intervene in students’ mental health problems early. Fortunately, we observed a decrease in the incidence of mental disorders during 1990–2019, indicating the effectiveness of the above intervention. However, since data during and after COVID-19 were unavailable, we cannot evaluate the situation and trend impacted by this 3-year-long pandemic.

The incidence of diabetes and kidney diseases showed the highest increase among all level 2 NCDs among children and adolescents in China, with diabetes mellitus experiencing the largest increase within this group. Furthermore, high fasting plasma glucose contributed to more than one-third of DALYs from diabetes mellitus in 2019. This rapid increase occurred in the whole population of China. The prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes exceeded 12% and 35%, respectively, among adults living in China.5 This rapidly increasing diabetes incidence in youth in China is the tip of a much larger iceberg of the growing body of impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose among children and adolescents and predicts a growing number of adult patients with diabetes in the future.

Neoplasms were also the leading cause of mortality from NCDs among children and adolescents in China; by contrast, the leading cause of death in adults in China is carcinoma (lung and liver cancers).15 Globally, China has an age-standardized DALY rate among adolescents higher than 61%–80% countries worldwide.16 As leukemia causes the highest mortality, testicular cancer has the most rapid increase in mortality, reflecting the shift from cancers that primarily affect children (e.g., acute lymphoblastic leukemia) to those that occur most often in adolescents and young adults (e.g., testicular cancers).16 The mortality rate of leukemia among children and adolescents in China was more than double that of their counterparts in the European Union (EU),9 even though the cure rate of childhood leukemia in developed countries is more than 80%.17 The high mortality of cancer among children and adolescents without appropriate and timely diagnosis and treatment urges focus on increasing the accessibility of health services for early diagnosis to reduce the disease burden of cancer.18

High BMI was the top risk factor for DALYs from neoplasms and diabetes among children and adolescents in China. Controlling high BMI can reduce DALYs from both diseases. More importantly, high BMI in children not only contributes to higher DALYs from diabetes and cancer in themselves but also predicts a higher risk of metabolic syndrome and other NCDs in adulthood and an even higher risk of still having a high BMI in adolescence and adulthood. Given the alarming increase in the prevalence of high BMI in childhood to adulthood and the precarious course of young adults with chronic comorbidities, the economic and clinical services burden on the healthcare system is expected to rise.19

Another risk factor for neoplasms among children and adolescents in China is alcohol use. According to a meta-analysis, alcohol use among individuals aged 10–24 years in China is very common: their alcohol use in the past 30 days and their lifetime were 27.2% and 59.7%, respectively.20 The Chinese government introduced its first national tobacco control guideline21; however, the social and health issues related to alcohol use and misuse, such as liver and cardiovascular diseases, mental disorders, cancers, and injury, have been largely neglected. In contrast to most countries in the world, the recorded alcohol consumption among individuals aged ≥15 years in China continues to increase.20 Alcohol use disorder among youth in China also had the largest gender difference in individuals aged 20–24 years. We advocate for stricter regulations and laws targeted at alcohol sales toward children and adolescents and interventions for alcohol use disorder targeted at male youth aged 20–24 years.

The study has implications. From a policy perspective, NCD control among children and adolescents requires efforts and implementation in all realms of policy, including strengthening the importance of physical education classes and providing at least 60 min/day activity for school children and adolescents, bully control campaigns, and education for both school staff and parents; alcohol control laws and healthy diet campaigns; and equal education opportunities for both rural and urban students and both migrants and local students. From a research perspective, public health providers and stakeholders need to understand the criticalness of NCD control among children and adolescents for NCD control among the whole population in China due to the chronic characteristics of NCDs and the life course perspective. To cope with the heavy burden of NCDs in China, we must give full play to our institutional, mobilization, and organizational advantages, adhere to prevention-oriented practices, emphasize the role of professional public health institutions, and consolidate and strengthen the disease control system and capacity building.22

The existing NCD burden among children and adolescents in China remained in mental disorders and neoplasms, while the increasing incidence was from diabetes and kidney diseases. Targeted interventions with limited resources should focus on high body mass, alcohol usage, and bullying victimization.

Limitations of the study

Potential limitations of this study include gaps in data source. This study relies solely on the Global Burden of Diseases database and is limited by variations in GBD data quality and missing data. The accuracy of GBD estimates is heavily reliant on the modeling process, which can introduce a degree of uncertainty. Due to limited clinical and research resources, the burden of disease in China can be underreported, which leads to underestimation during modeling process. This study cannot separate data from children and adolescents in rural areas from those in urban areas, who have differences in growing environment and access to healthcare in China. For trend analysis, the only independent variable we consider is the year. A cautious interpretation of the results is warranted.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Deposited data | ||

| Data source of this paper | Global Burden of Diseases 2019. Available at https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ | Global Burden of Diseases 2019 is publicly available as of the date of publication. |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism (version 8.0) | https://www.graphpad.com/features | GraphPad Prism (version 8.0) |

| R (version 4.2.1) | https://www.r-project.org/ | R (version 4.2.1) |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Yongze Li (pandawisp@163.com).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

Data in this paper is available through the online database of Global Burden of Diseases 2019.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyzed the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and study participant details

The population included in the study were children and adolescents aged 10–24 years in China from the public database of Global Burden of Diseases 2019 (GBD). Data from both genders in three age groups (10–14, 15–19, and 20–24) were collected. Data on the children and adolescents in China in GBD 2019 was collected from the China Maternal and Child Surveillance data and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure database. The population included in the GBD estimation are also identified from multiple relevant data sources for each disease or injury, including censuses, household surveys, civil registration and vital statistics, disease registries, health service use, air pollution monitors, disease notifications, and other sources. Each of these types of data is identified from a systematic review of published studies, searches of government and international organization websites, published reports, primary data sources such as the Demographic and Health Surveys, and contributions of datasets by GBD collaborators. As total of 86,249 sources were used in GBD 2019, including 19,354 sources reporting deaths, 31,499 reporting incidence, 1973 reporting prevalence, and 26,631 reporting other metrics. The GHDx makes publicly available the metadata for each source included in GBD as well as the data, where allowed by the data provider.

This study does not contain personal or medical information about identifiable living individuals, and animal subjects were not involved. The institutional review board of the First Hospital of China Medical University determined that the study did not need approval because it used publicly available data. This study followed the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting Guidelines for cross-sectional studies.

Method details

The Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx) includes the global burden of 369 diseases and injuries and 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019,9 including NCDs and non-NCDs, and are provided directly for download. This study data is repeated cross-sectionally. The number of incident cases, deaths, and DALYs, and the incidence rate, mortality rate, and DALY rate were extracted directly from the GBD. All rates are reported per 100,000 population. The 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs) were defined by the 25th and 975th values of the ordered 1,000 estimates based on the GBD’s algorithm. The GBD 2019 cause list is composed of a four-level hierarchy, with each level comprising mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive causes. There are three level 1 causes (including communicable; NCDs; and injuries), 22 level 2 causes, 174 level 3 causes, and 301 level 4 causes. In this study, we exclusively focused on NCD causes. The risk factor and all data of GBD are identified from a systematic review of published studies, searches of government and international organization websites, published reports, primary data sources such as the Demographic and Health Surveys, and contributions of datasets by GBD collaborators to ensure the quality of the surveys.

The above gathered data was processed through standardized steps including input data, age-gender splitting, cause aggregation, and noise reduction. The computational methods including the cause of death ensemble model (CODEm), spatiotemporal Gaussian process regression (ST-GPR), and DisMod-MR. Details of the methodology used in the GBD 2019 have been explained in previous studies.9 The validation of the risk factor and underlying analysis can be found in previously published study.10

Quantification and statistical analysis

Annual Percent Change (APC) is used in this study to characterize global trends of the level 1, level 2 and level 3 NCD incidence, the mortality and DALYs over time. During the Joinpoint regression model, when the Log Transformation option on the Input File tab is ln(y) = xb, the x1, …, xn represent years and y1, …, yn represent the log of the observed rate, then the output calculates the estimated APC along with its confidence interval (CI).11 Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC) is a summary measure of the trend over a pre-specified fixed interval.12 The AAPC can use a single number to describe the average APCs over multiple years. It is also computed during the Joinpoint regression model as a weighted average of the APCs, with weights equal to the length of the APC interval.12 All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 8.0) and R (version 4.2.1).

Additional resources

Alternate contact: Jing Zhang (zhangjing1985zj@163.com)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82000753 and 82304201), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant nos. 2021MD703910 and 2023T160724). The graphical abstract was created with BioRender.com.

Author contributions

Y.L. and J.Z. designed the study. Y.L. and J.Z. analyzed the data and performed statistical analyses. J.Z. and Y.L. drafted the initial manuscript. C.S., Z.L., C.J., L.W., and Y.Z. contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the drafted manuscript for critical content and approved the final version. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. Y.L. is the guarantor.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Inclusion and diversity

We support inclusive, diverse, and equitable conduct of research.

Published: December 19, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101331.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 2020. The top 10 causes of death.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death Available at. Accessed on. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Shlomo Y., Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2002;31:285–293. [published Online First: 2002/05/01] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Bureau of Statistics The 7th National Population Census. 2021. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-05/11/content_5605787.htm Available at. Accessed on.

- 4.Dong Y., Wang L., Burgner D.P., Miller J.E., Song Y., Ren X., Li Z., Xing Y., Ma J., Sawyer S.M., Patton G.C. Infectious diseases in children and adolescents in China: analysis of national surveillance data from 2008 to 2017. Bmj. 2020;369:m1043. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1043. [published Online First: 2020/04/04] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y., Teng D., Shi X., Qin G., Qin Y., Quan H., Shi B., Sun H., Ba J., Chen B., et al. Prevalence of diabetes recorded in mainland China using 2018 diagnostic criteria from the American Diabetes Association: national cross sectional study. Bmj. 2020;369:m997. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m997. [published Online First: 2020/04/30] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y., Zhao L., Gao L., Pan A., Xue H. Health policy and public health implications of obesity in China. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9:446–461. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00118-2. [published Online First: 2021/06/08] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health. 2016-2030. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/the-global-strategy-for-women-s-children-s-and-adolescents-health-(2016-2030)-early-childhood-development-report-by-the-director-general Available at. Accessed on. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Chen P., Li F., Harmer P. Healthy China 2030: moving from blueprint to action with a new focus on public health. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4:e447. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30160-4. [published Online First: 2019/09/09] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armocida B., Monasta L., Sawyer S., Bustreo F., Segafredo G., Castelpietra G., Ronfani L., Pasovic M., Hay S., et al. GBD 2019 Europe NCDs in Adolescents Collaborators Burden of non-communicable diseases among adolescents aged 10-24 years in the EU, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2019. Lancet. Child Adolesc. Health. 2022;6:367–383. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00073-6. [published Online First: 2022/03/28] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X., Wu J., Zhu X. The Enlightenment of the United Nations High Level Conference on Chronic Disease Prevention and Control on the Development of China's Public Health Industry. Chin. J. Prev. Med. 2019;53:545–548. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chinese Academy of Sciences Report on the Development Plan for National Mental Health in China 2021-2022. https://www.cas.cn/cm/202302/t20230227_4875996.shtml Available at. Accessed on.

- 12.Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People's Republic of China . 2018. Data on rural left behind children.https://www.mca.gov.cn/article/gk/tjtb/201809/20180900010882.shtml Available at. Accessed on. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monitoring and Investigation Report on Migrant Workers. 2021. http://www.stats.gov.cn/xxgk/sjfb/zxfb2020/202204/t20220429_1830139.html Available at. Accessed on.

- 14.H Fan L.X., Xiu J., Chen L., Liu S. Harsh parental discipline and school bullying among Chinese adolescents: The role of moral disengagement and deviant peer affiliation. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022:145. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou M., Wang H., Zeng X., Yin P., Zhu J., Chen W., Li X., Wang L., Wang L., Liu Y., et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2019;394:1145–1158. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30427-1. [published Online First: 2019/06/30] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.GBD 2019 Adolescent Young Adult Cancer Collaborators The global burden of adolescent and young adult cancer in 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:27–52. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00581-7. [published Online First: 2021/12/07] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leukemia: A Cancer that Affects Children and Adults. Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center. Available at https://cancerblog.mayoclinic.org/2022/01/18/leukemia-a-cancer-that-affects-children-and-adults/. Accessed on 28th August 2023. .

- 18.Ni X., Li Z., Li X., Zhang X., Bai G., Liu Y., Zheng R., Zhang Y., Xu X., Liu Y., et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in cancer incidence and access to health services among children and adolescents in China: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2022;400:1020–1032. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01541-0. [published Online First: 2022/09/27] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bendor C.D., Bardugo A., Pinhas-Hamiel O., Afek A., Twig G. Cardiovascular morbidity, diabetes and cancer risk among children and adolescents with severe obesity. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020;19:79. doi: 10.1186/s12933-020-01052-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang H., Room R., Hao W. Alcohol and related health issues in China: action needed. Lancet. Glob. Health. 2015;3:e190–e191. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70017-3. [published Online First: 2015/03/22] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu Y., Sun X., Yuan Z., Dong W., Zhang J. Another step change for tobacco control in China? Lancet. 2015;386:339–340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61409-X. [published Online First: 2015/08/01] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X.H., Ma J.X., Wu J., Zhu X.L. Enlightenment of the United Nations high-level summit on non-communicable disease prevention and control on the development of public health system in China. Zhonghua Yufang Yixue Zazhi. 2019;53:545–548. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

Data in this paper is available through the online database of Global Burden of Diseases 2019.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyzed the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.