Abstract

Understanding metabolic performance limitations is key to explaining the past, present and future of life. We investigated whether heat tolerance in actively flying Drosophila melanogaster is modified by individual differences in cell size and the amount of oxygen in the environment. We used two mutants with loss-of-function mutations in cell size control associated with the target of rapamycin (TOR)/insulin pathways, showing reduced (mutant rictorΔ2) or increased (mutant Mnt1) cell size in different body tissues compared to controls. Flies were exposed to a steady increase in temperature under normoxia and hypoxia until they collapsed. The upper critical temperature decreased in response to each mutation type as well as under hypoxia. Females, which have larger cells than males, had lower heat tolerance than males. Altogether, mutations in cell cycle control pathways, differences in cell size and differences in oxygen availability affected heat tolerance, but existing theories on the roles of cell size and tissue oxygenation in metabolic performance can only partially explain our results. A better understanding of how the cellular composition of the body affects metabolism may depend on the development of research models that help separate various interfering physiological parameters from the exclusive influence of cell size.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘The evolutionary significance of variation in metabolic rates’.

Keywords: rictor Δ2 , Mnt 1 , TOR, metabolic performance, hypoxia, thermal limits

1. Introduction

Knowing what shapes and constrains the metabolic performance of organisms is crucial for understanding past, present and future ecological and evolutionary processes. There is no doubt that thermal conditions should be considered one of the most prominent determinants of the ‘window of habitability’, and current data for Earth suggest that this temperature ‘window’ for the growth and reproduction of living things is quite broad, ranging from −15 to 122°C [1,2]. Here, we use fruit flies, Drosophila melanogaster, with genes modified by mutations in cell cycle control mechanisms to investigate an unexplored hypothesis that the physiological upper thermal limits of organisms at different atmospheric oxygen levels are affected by the cellular composition of their body. Originally from Africa, D. melanogaster have spread globally over an unusually wide range of environments located at different latitudes and elevations [3–6], indicating an ability to cope with the challenges imposed by broad environmental gradients of thermal conditions and oxygen concentrations. The thermal environment impacts virtually every aspect of life, from the rates of metabolic processes performed by cells and tissues in organisms to the water balance, nutrient cycling and between-species interactions (e.g. parasitism and predation) in ecosystems, which ultimately shape biodiversity, species geographical distributions, species spatial ranges and evolutionary processes [7]. For Drosophila, the maximum temperature of the warmest month and precipitation level in the driest month were demonstrated to explain the global distribution of different species, matching species-specific differences in heat tolerance [8]. These impacts are now debated in light of progressing global warming (with global temperatures currently being 1.1°C above preindustrial levels) and its associated phenomena, such as rising sea levels and the intensification of droughts, floods, strong winds, sudden heat waves and other extreme weather conditions [9]. For example, the distribution of the tsetse fly Glossina pallidipes across Africa appears to be changing primarily in response to thermal shifts accompanying the current climate changes [10]. This renewed interest in organisms' capabilities to perform over thermal gradients [11] has provided various views on the origin of physiological thermal limits (see [12] for a comprehensive review). If we focus on an ectotherm, we typically see a rise in its metabolic performance with temperature, stabilizing at some maximum level over a range of temperatures [7,13]. At some point, a further temperature increase leads to a dramatic drop in metabolic performance until the cells and entire organism stop functioning and, finally, die (upper thermal limits). This occurs due to irreversible biophysical processes at the molecular level, which involve protein denaturation and membrane physical disorganization [14]. However, it is unclear whether these mechanisms occur prior to the manifestation of other processes that begin to limit ectotherms’ metabolism, e.g. the reduced ability to meet increasing metabolic demand for ATP through its production via mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. For instance, Pörtner [15] postulated that thermal limits are shaped primarily by metabolic constraints, namely, the capacity to meet oxygen demand at the mitochondrial level. However, this mechanism has received greater support for aquatic [16] than terrestrial ectotherms [17,18].

Addressing the idea of metabolic constraints, we hypothesize that oxygen delivery to mitochondria is influenced by the cellular composition of tissues and organs (cell number and size), which ultimately shapes the metabolic performance and thermal responses of the organism. Emerging evidence reveals variance in cell size within and between species [19–24], but the association of this variance with the metabolic performance of organisms across environments is poorly studied (but see [25–27]). Nevertheless, the theory of optimal cell size (TOCS) [23,27–35] considers that the cellular composition of an organism brings metabolic consequences with evolutionary costs and benefits, which vary along with environmental gradients in metabolic demand and supply. On the one hand, small cells in the body bring metabolic costs, as they require additional molecular substrates (elements, organic compounds) and ATP for maintaining plasma membranes (membrane composition, ionic gradients on the cell surface). On the other hand, small-celled organisms should have increased physiological capacity to metabolize resources due to the larger cell surface area for transport, shorter diffusion distances and increased number of nuclei for transcription. Accordingly, a small-celled ectotherm may suffer higher metabolic costs of tissue maintenance, but it is likely to outperform large-celled competitors when faced with increased metabolic demands, e.g. when a flying insect is exposed to elevated temperatures combined with decreased access to atmospheric oxygen. The metabolic performance of terrestrial insects is sometimes viewed as free from oxygen limitation [18], but during active flight, the insect demands for oxygen drastically increase, which can push them closer to such limits [36,37]. In fact, the effects of this limitation are manifested by the association between oxygen levels on a geological time scale and the evolutionary changes in insect sizes [38]. At present, even extant insects can experience numerous combinations of thermal and oxygen conditions in their terrestrial habitats, which include oxygen-poor soil and litter microenvironments, environments at different elevations [39] or hypoxic conditions created by cave environments [40].

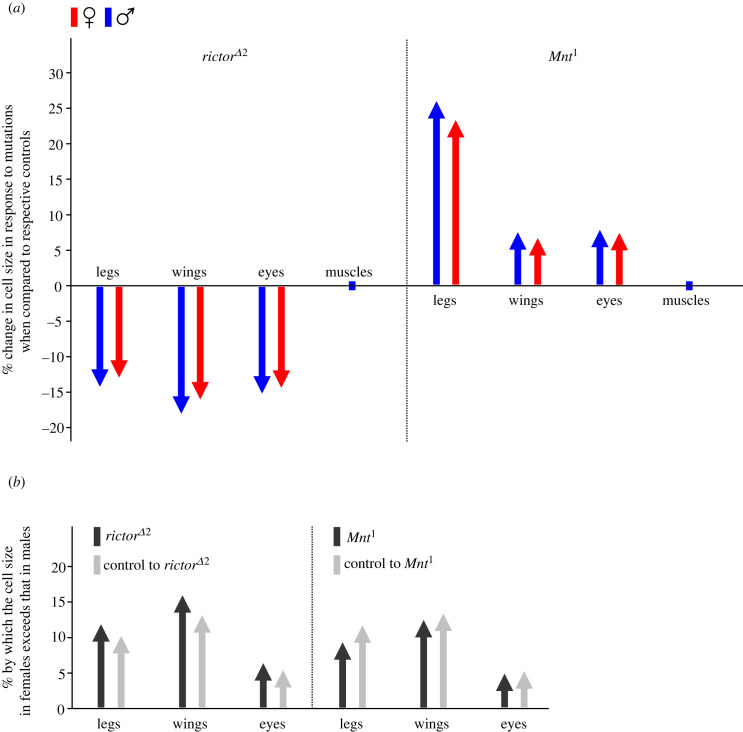

To study heat tolerance in D. melanogaster with well-defined genetic alterations in cell size control mechanisms, we chose two tandems of genetic forms with engineered mutations in the TOR/insulin pathways: the rictorΔ2 mutant and its control, and the Mnt1 mutant and its control (see [41,42] for mutant creation and control characteristics). In addition to being key regulators of cell growth and proliferation, the target of rapamycin (TOR)/insulin pathways also play a role as the major ‘molecular backbone’ in controlling a wide range of metabolic functions, such as autophagy, ribosomal protein synthesis and the metabolic responses to nutrient and energy fluxes and stress through downstream effectors, e.g. Myc and FOXO [43–45]. We have previously demonstrated that these mutations imposed highly correlated cell size shifts throughout the body in two opposite directions (see [46] and figure 1), with rictorΔ2 serving here as a model of small-celled flies and Mnt1 as a model of large-celled flies. When we selected these two mutations for our study, one of our considerations was that they are among the few available mutations of cell cycle pathways that result in viable flies in homozygous states, providing us with a convenient system for involving large groups of individuals in our experiments. We measured heat tolerance by exposing the flies (males and females) to a rapid, steady rise in temperature under normoxia (standard oxygen levels) or hypoxia (reduced oxygen levels) so that we could compare the performance of each mutant against its control under oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor conditions. To study flies engaged in a metabolically demanding activity, the measurements were performed under conditions that forced the flies to fly freely or climb on a vertical surface. We hypothesized that flies challenged by hypoxia would show lower upper critical temperatures, following the general postulates of Pörtner [15] that decreasing amounts of oxygen reaching mitochondria would reduce metabolic performance and thus decrease heat tolerance. Given the effects of cell size on tissue oxygenation postulated by TOCS, we hypothesized that small-celled flies would show increased heat tolerance compared to the large-celled forms, with this difference exaggerating under hypoxia. Our previous work (figure 1) showed that the male flies studied have smaller cells in various tissues throughout the body than the females. We therefore took advantage of such differences in cell size to investigate whether potential sex differences in heat tolerance (if any) could be attributed to cell size effects postulated by TOCS. If so, the sex with smaller cells (males) should show increased heat tolerance compared to the sex with larger cells (females), with the difference in heat tolerance between sexes increasing under hypoxic conditions. The loss of functional proteins in crucial molecular regulatory pathways may disrupt an array of vital metabolic functions, affecting tolerance for extreme environmental conditions through physiological phenomena unrelated to cell size. Therefore, it is possible that any mutation affecting metabolic function, independent of its effect on cell size, could lead to a loss of tolerance to heat and hypoxia. This alternative scenario is considered here without relying on predetermined molecular mechanisms.

Figure 1.

The percentage change in cell size in legs, wings, eyes and flight muscles in Drosophila melanogaster adults in two tandems of the genetic lines studied here (rictorΔ2 mutant versus rictorΔ2 control and Mnt1 mutant versus Mnt1 control). Arrows show mean values (with statistical significance; see below) obtained from Privalova et al. [46], which were estimated by statistical analysis of cell size measurements in individuals derived from the same pool of flies as studied here. (a) In comparison to their respective controls, rictorΔ2 mutant flies were characterized by smaller epidermal cells in legs (p = 0.002) and wings (p < 0.001) and smaller ommatidial cells in eyes (p < 0.001), while Mnt1 mutant flies were characterized by larger epidermal cells in legs (p < 0.001) and wings (p < 0.001) and larger ommatidial cells in eyes (p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the size of dorsal longitudinal indirect flight muscle cells among the genetic lines. (b) In all genetic lines, females had consistently larger cells than males in legs (p = 0.002), wings (p < 0.001) and eyes (p < 0.001). Cell size (µm2 for all cell types) was measured in legs, wings and eyes for both sexes and in flight muscles for males only.

2. Methods

(a) . Animals and experimental setup

The flies were provided by Prof. Ville Hietekangas (University of Helsinki, Finland)—rictorΔ2 and its control; Prof. Peter Gallant (University of Wurzburg, Germany)—Mnt1 and Prof. Robert N. Eisenman (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Centre, the USA)—the control for Mnt1. The flies were maintained in a small stock of D. melanogaster genotypes at the Institute of Environmental Sciences, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland. The stock was kept under controlled constant conditions in thermal cabinets (Pol-Eko-Aparatura, Wodzisław Śląski, Poland) set to 20.5°C and a 12 h : 12 h day : night photoperiod. Open containers with water inside thermal cabinets provided stable 70% relative humidity. The flies were kept in 68 ml vials covered with polyurethane foam plugs containing 20 ml of standard cornmeal yeast food (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, Bloomington, IN, USA). Every three weeks, parental flies were transferred to fresh vials for egg laying, which maintained non-overlapping generations.

To increase the abundance of flies for the experiment, we used a subset of stock flies to produce two successive generations under a controlled density of larvae (a two-transfer procedure). For each transfer, we placed 10 females with four males in a fresh vial for 48 h of egg laying. At the first transfer, we increased the number of vials with flies to 40 per genetic line, randomly creating five sets of eight vials per genetic line, which served as random replicate groups for each genetic line (4 genetic lines × 5 replicate groups = 20 replicate groups in total). At the second transfer, we further increased the number of vials with flies to 24 per replicate group (totalling 120 vials per genetic line). We also used both transfers to spread the emergence of flies for the experiment through time, causing our measurements to be logistically feasible. For this purpose, each transfer was performed over five consecutive days, and each day, the transfer involved flies from only one of five replicates per genetic line. In this way, we synchronized the emergence of flies for the measurements in all four genetic lines, evenly spreading their availability over time. This also helped us maintain a balance in the experimental design, involving representatives of all genetic lines in the measurements carried out on a given day under both experimental regimes (two oxygen conditions).

The entire experiment was executed twice, which created two experimental runs that were treated as random time blocks in our statistical analysis. The second experimental run was performed 21 days after the first one, repeating the two-transfer procedure used in the first run. In the end, each genetic line was represented in the entire experiment by 10 random replicate groups (five in each experiment run). To estimate the upper thermal limits, we used 5–7-day-old adult flies originating from the second generation produced via our two-transfer procedure.

(b) . Experimental measurements

We aimed to measure the upper thermal limits of freely moving flies (walking, flying) at two oxygen levels; we performed these measurements in the system outlined in figure 2 by subjecting flies to gradually increasing temperatures. The dynamic heat tolerance assay has proven to be an effective method for quantifying physiological thermal limits to understand the influence of climate on the spatial distribution of ectotherms, including Drosophila flies [47]. At the beginning of each experimental session, we placed a group of flies in a large vertical measuring chamber with controlled thermal and oxygen conditions. While the oxygen level (either normoxia or hypoxia) remained unchanged throughout a session, the temperature inside the chamber steadily increased over time. At some point, conditions inside the chamber disturbed the flies' capability to grasp the surface and/or perform flight. The knocked-down flies fell down the chamber into collecting vials, which were exchanged every minute for empty vials until all flies were collected from the chamber. After each session, we sexed and counted flies in each vial to associate the cumulative proportions of knocked-down flies with chamber temperatures. The upper thermal limit was expressed as the temperature at which 50% of the loaded flies were knocked down.

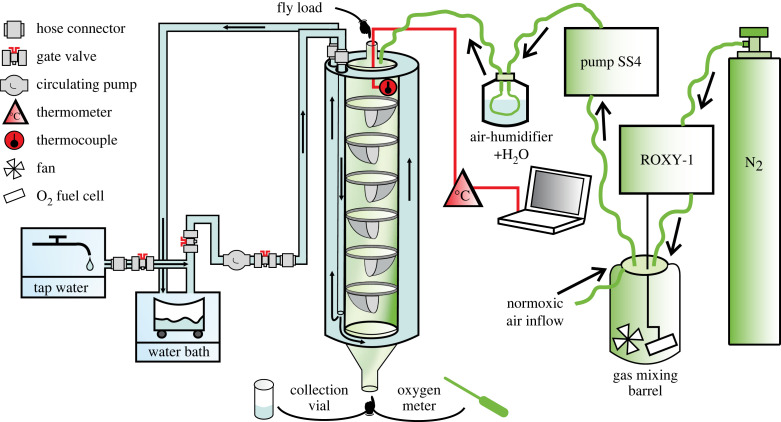

Figure 2.

The system for measuring the upper critical temperatures in Drosophila melanogaster engaged in active flight or climbing. The measuring chamber was made of a double-walled transparent Plexiglass tube, and Plexiglass baffles were arranged along its inner space. To control the temperature inside the apparatus, water flowed in a closed circuit through the water bath and the space between the walls of the chamber. A recirculating water pump controlled a steady flow of water and a uniform rise in temperature inside the chamber. To create hypoxic conditions, the gas-mixing system ROXY-1 added appropriate amounts of N2 from the gas cylinder to the 20 dm3 barrel (gas mixing). To create normoxic conditions, outside air leaked constantly into the barrel, while N2 was not added to the barrel. In both cases, the SS4 pump controlled the gas supply to the measurement chamber, and the gas mixture passed through a humidifier before entering the chamber. The oxygen concentration in the gas-mixing barrel was monitored continuously with the oxygen fuel cell. To confirm the oxygen concentration directly inside the chamber before the measurements, an external oxygen metre was used. The temperature inside the chamber was monitored and recorded every second using a thermocouple thermometer connected to a computer. Once the conditions inside the measurement chamber stabilized at a desired baseline level, the water bath was switched on and a group of flies was loaded into the chamber. The temperature inside the chamber increased at a steady rate. The flies knocked down by conditions fell down the chamber, entering collecting vials that were exchanged every minute. The upper critical temperature was defined as the temperature at which 50% of flies were knocked down.

The measuring system (figure 2) consisted of a measuring chamber for flies, a thermocouple thermometer connected to a computer, a water bath with tubing and a water-circulating pump and a gas-mixing system with a gas cylinder, tubing, gas-mixing barrel and an air-pump. The overall design of the measuring chamber was inspired by earlier works [48], and it was made of a double-wall transparent Plexiglass pipe vertically mounted on a stand. The entire system was placed in a climate-controlled room with stable conditions of 23°C and dim light, which provided consistency in measurement conditions across sessions. At the beginning of each measuring session, we loaded the flies via an entering hole (closed with a plug) on the top part of the measuring chamber. Plexiglass baffles were positioned across the internal space of the chamber in alternating directions. The magnets incorporated into the baffles and chamber walls allowed the baffles to be removed and placed in the desired positions. The baffles’ shape ensured that the knocked-down flies could not stay on the baffles' surface and fell freely to the exit hole in the bottom. To ease the sliding down of flies to the collecting vials, the bottom walls of the chamber narrowed towards the exit hole, making a funnel-like shape. The funnel-shaped bottom walls were coated with a thin fluon layer to further reduce friction. The collecting vials’ diameter fitted the diameter of the exit hole at the bottom of the chamber, preventing the outside air from entering during measurements. The collecting vials contained a small amount of water with dish detergent, which immediately immobilized flies falling into the vial.

The steady air inflow from a gas-mixing 20 l barrel provided the desired oxygen conditions inside the measuring chamber and additionally generated an overpressure inside the chamber, which minimized diffusive entry of normoxic outside air into the chamber. The gas mixture passed through a humidifier (Nafion bottle, Sable Systems International, Las Vegas, AZ, USA) before entering the chamber by tubing connected to its top. The SS4 pump (Sable Systems) controlled the inflow at 650 ml min−1. We used the gas-mixing system ROXY-1 (Sable Systems) to create hypoxia (5% O2), with the oxygen concentration inside the barrel monitored continuously via an FC-1S oxygen sensor (Sable Systems). The cover of the air-mixing barrel provided a constant leak of the normoxic outside air. To create hypoxic conditions, the gas-mixing system added adequate amounts of N2 from a gas cylinder (AirProducts, Siewierz, Poland) to the barrel. To create normoxic conditions (21% O2), we used outside air (no gases added) that constantly entered the barrel. Before loading the flies into the measuring chamber, oxygen conditions inside the chamber were confirmed with a Pocket Oxygen Metre FireStingGO2 by placing an optic oxygen sensor OXROB10 (PyroScience GmbH, Aachen, Germany) into the exit hole of the chamber. After this, we replaced the sensor with a collection vial, and the apparatus was considered ready to take measurements.

The temperature inside the measuring chamber was consistently monitored and recorded every second with a 1 mm fast-response thermocouple (PTTT-TKbWm-O-V-10-1-200/2000-TT, ACSE Sp. z o. o., Kraków, Poland) with a thermocouple thermometer (HD2128.2 DeltaOHM S.r.l., Caselle di Selvazzano (PD) Italy; resolution: 0.05°C in the range ±199.95°C) connected to a computer. The thermocouple entered the chamber from the top through a small hole. To control the thermal conditions inside the chamber, water was constantly run through the volume between the two walls of the chamber. The water entered the chamber through a closed tubing system connected to a water bath (WNB7, Memmert GmbH + Co. KG, Schwabach, Germany). A circulation pump for potable water (OMIS 25-40/180, OMNIGENA, Płochocin, Poland) provided a constant and controlled water flow in the entire system. At the beginning of each session, the water bath was supplied with cold tap water. Then, when the oxygen concentration inside the chamber reached the desired level, the water bath was switched on and set to 80°C, which steadily increased the water temperature in the entire system. The temperature inside the measuring chamber increased linearly over time at 0.79°C per minute, with only slight deviations of this rate between measurement sessions (s.d. = 0.026). Note that in dynamic heat tolerance assays, ectotherms are challenged by a rapid increase in body temperature, which can also involve some degree of stress from desiccation, resulting from physical laws that negatively link air temperature with relative humidity [49]. Therefore, in pre-measurement sessions, we also recorded relative humidity with a Hygrochron DS1923 iButton (Dallas Semiconductors, Dallas, USA) placed inside the measuring chamber. Based on these data, we estimate that an increase in temperature during our measurement sessions was accompanied by a steady decrease in relative humidity at 1.95% points per minute, with relative humidity reaching 76.2% (s.d. = 2.27 between sessions) at 25°C (the starting point of exposure of flies to experimental conditions) and 35.5% (s.d. = 0.55 between sessions) at 40°C (the approximate endpoint of exposure of flies to experimental conditions).

We loaded flies into the measuring chamber at a chamber temperature of 25°C. After loading, we closed the entrance hole and allowed flies to briefly acclimate to the measuring conditions, and waited until the temperature reached 27°C before making any measurements. At this stage, all flies that fell into a collecting vial placed below the existing hole at the bottom of the chamber were considered to show physiological issues with maintaining basic performance under benign conditions. Therefore, they were eliminated from the measurements of the upper thermal limits. The collection of flies to be used in the measurements began by placing a fresh collection vial at the point when the chamber temperature was equal to 27°C (time was set to 0 at this point).

At the beginning of a given session, flies representing one of the replicate groups were placed in the chamber set to either hypoxia or normoxia. Each session involved approximately 200 flies (both sexes included) per replicate group (4 genetic lines × 5 replications × 2 runs) under each oxygen condition, and each replicate group was tested on the same day under both oxygen conditions. Consequently, each measurement session resulted in measurements for each sex collected from the same group of flies loaded together into the measuring chamber (figure 2). To account for this dependence in our measurements, groups of flies involved in each measurement session were treated as a random grouping factor in our statistical analyses (hereafter, measurement session). For collection vials, we used a set of glass vials marked with consecutive numbers. A glass vial was attached to the bottom of the chamber such that knocked-down flies could fall inside freely. As the chamber temperature steadily increased, the collection vials were exchanged every minute and the time of vial exchange was recorded. The time was controlled with a stopwatch application (http://www.estopwatch.net/) and loop-counter software (https://www.online-stopwatch.com/download-stopwatch/) simultaneously. This allowed us to integrate the recorded times of vial exchange with temperature recordings inside the measuring chamber. Ultimately, for each sex and replicate group, we calculated the temperature (°C) at which 50% of flies were knocked down, which was our measure of the upper thermal limits.

(c) . Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed in R 4.1.3 software [50] using the lme4 [51] and lmerTest [52] packages; we used the emmeans [53] and ggplot2 [54] packages to generate graphs. To explore whether genetic lines and oxygen conditions affected the upper thermal limits, we used a general linear mixed model (GLMM). Our model included a genetic line (rictorΔ2 mutant, rictorΔ2 control, Mnt1 mutant, Mnt1 control), oxygen (normoxia and hypoxia), sex (male and female), genetic line × oxygen interaction and sex × oxygen interaction as fixed grouping factors, while experimental runs, replication groups and measurement sessions were considered as random factors. Notably, the effects of the replication group and measurement session were nested within the effects of experimental runs. Each replication group was represented by two measurement sessions, one performed at normoxia and the other at hypoxia, and each session was represented by two sex-specific measures of the upper thermal limits. It is important to note that direct comparisons between two mutants or two controls would not be meaningful in our case, as each mutant was independently created by a different research centre from a different genetic strain of flies that served as a control. Therefore, the GLMM was followed by a contrast analysis: Contrast 1—rictorΔ2 mutant versus rictorΔ2 control and Contrast 2—Mnt1 mutant versus Mnt1 control, which helped to assess the effects of each mutation concerning a relevant control. We used the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and the homogeneity of variance with Levene's test to confirm assumptions of parametric methods.

3. Results

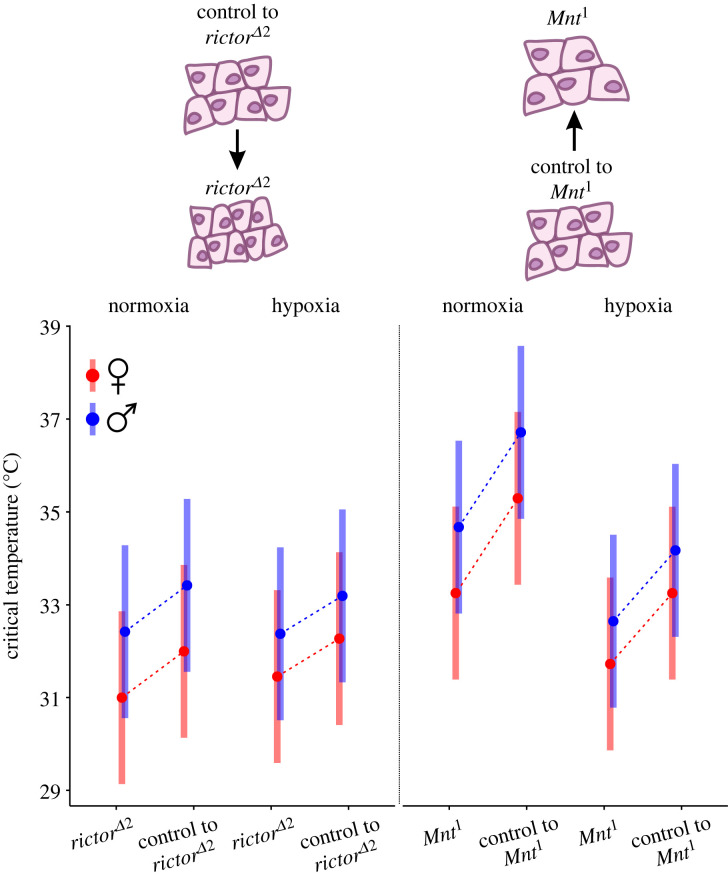

Altogether, our GLMM results (table 1, figure 3) indicated that the heat tolerance of flies decreased in response to each type of mutation, it was lower in females than males, and it dropped in response to lower oxygen availability. Our measure of the upper thermal limit was lower in the rictorΔ2 (p = 0.015) and the Mnt1 (p < 0.001) mutants when compared to their respective control lines. In comparison to females, males could withstand higher temperatures (p < 0.001). The interaction between the effect of sex and oxygen regime appeared to be nonsignificant (p = 0.093), indicating that each sex responded in a similar manner to differences in oxygen conditions. Poor oxygen conditions generally decreased tolerance of higher temperatures, and the strength of the effect depended on a genetic line, indicated by a significant interaction between the genetic line and oxygen regime (p < 0.001). When we analysed GLMM with contrasts, we did not find significance at the p = 0.05 level for the interactions between each contrast and oxygen: p = 0.674 for the interaction with Contrast 1 (rictorΔ2 versus control) and p = 0.233 for the interaction with Contrast 2 (Mnt1 versus control). This meant that within each tandem of genetic lines, a mutant and its control responded similarly to oxygen conditions. This further indicated that the significance of an interaction between a genetic line and oxygen conditions in the primary GLMM (without contrasts) was driven by more pronounced effects of hypoxia in one tandem of genetic lines (Mnt1 mutant and its control) compared to the other tandem of genetic lines (rictorΔ2 and its control; see also figure 3).

Table 1.

Results of the GLMM model for the upper critical temperatures in four genetic lines of adult Drosophila melanogaster (rictorΔ2 mutant and its control, Mnt1 mutant and its control) measured in normoxia and hypoxia (see figure 2 for the measurement system). The analysis included two contrasts, which compared each mutant type with its control. Each measurement session resulted in two sex-specific measures of the upper critical temperature per replicate group. The entire experimental procedure for all flies was replicated twice over time, resulting in two experimental runs. Figure 1 shows the cell size characteristics of the studied flies.

| fixed effects | upper thermal limits (°C) N = 160 |

|

|---|---|---|

| t | p-value | |

| intercept | 82.99 | 0.003 |

| sex | 4.43 | <0.001 |

| genetic line | 2.71 | 0.008 |

| oxygen (normoxia) | 3.38 | 0.001 |

| genetic line × oxygen (normoxia) | 7.15 | <0.001 |

| sex (male) × oxygen (normoxia) | 1.7 | 0.093 |

| contrast 1 (rictorΔ2 versus control) | −2.5 | 0.015 |

| contrast 2 (Mnt1 versus control) | −4.67 | <0.001 |

| contrast 1 × oxygen (normoxia) | −0.42 | 0.674 |

| contrast 2 × oxygen (normoxia) | −1.21 | 0.233 |

| random effects | variance estimates | |

| experimental run (intercept) | 0.25 | |

| replicate group (intercept) | 0.08 | |

| measurement session (intercept) | 0.02 | |

| residual | 0.86 | |

Figure 3.

Adult Drosophila melanogaster showed significant differences in the upper critical temperatures between the studied genetic lines: both rictorΔ2 and Mnt1 mutations decreased heat tolerance in comparison to their respective control lines, with males showing higher heat tolerance than females at both normoxia and hypoxia. Hypoxia resulted in decreased heat tolerance, especially in the tandem of Mnt1 and its control line. The two mutants and their controls represent two tandems of genetic lines with different cell sizes, with rictorΔ2 representing flies with reduced cell size (compared to its control) and Mnt1 representing flies with enlarged cells (compared to its control); see figure 1 for cell size characteristics of the studied flies. The upper critical temperature was measured during a steady increase in temperature, and it represents the temperature at which 50% of flies were knocked down (see figure 2). The means (95% CI) were estimated with a general linear mixed model shown in table 1.

4. Discussion

For D. melanogaster, abundant evidence shows that cell size is sensitive to rearing and selective conditions, with higher or fluctuating temperatures leading to small-celled adults [19,32,55–59]. For the developmental plastic effects, this response has been recently shown to magnify under a decreased supply of environmental oxygen [60]. In nature, low-latitude warmer environments have also been known to drive the evolution of D. melanogaster with smaller cells in the adult body [4,61,62]. Although the metabolic consequences of variation in cellularity are poorly studied, emerging evidence sheds more light on this phenomenon. For example, at high temperatures, small-celled fish species were found to tolerate hypoxia better than large-celled species [27]. In other studies, small-celled forms of adult D. melanogaster were induced developmentally by larval feeding with rapamycin, a drug that downregulates the activity of the TOR kinase in TOR complex 1, reducing downstream signalling coming from this part of the TOR/insulin pathways [63,64]. The small-celled flies in these studies showed better flight performance under hypoxia than large-celled flies, and this effect was temperature-dependent [26], but they suffered increased mortality during early adulthood [63]. Our results here suggest that the effects of variation in cell size between flies may also partially account for changes in heat tolerance when flies are engaged in metabolically demanding activities, such as flight and climbing. Supporting the TOCS that larger cells put metabolism at risk of tissue hypoxia, we found that our large-celled mutant flies (Mnt1) were less heat tolerant than their small-celled controls, and consistently, females, which are the larger cell sex in D. melanogaster (see [65,66] and figure 1 depicting data for the studied flies), showed lower heat tolerance than males. In partial agreement with this pattern, Verspagen et al. [59] reared D. melanogaster at different temperatures, showing that warm-reared flies, which were enclosed with smaller wing epidermal cells, survived longer under acute and intense heat stress than cold-reared flies, but both sexes showed similar survival patterns. Though the two experiments were not fully comparable due to different experimental and measurement protocols, their inconsistent results regarding the sex dependence of D. melanogaster heat tolerance may indicate phenomena related to sex-specific metabolic functions that manifest differently in environmental gradients. Indeed, available evidence suggests that the sex dependence of heat tolerance may vary with the rearing conditions of larvae and differ between Drosophila species [67,68]. Notably, however, most previous studies on thermal response in ectotherms have ignored the existence of potential sex differences in heat tolerance [69]. On a molecular level, heat tolerance relies on the functioning of specific heat stress/hypoxia signalling pathways and proteins (such as HSP and HIF), shaped to some extent by an organism's exposure to developmental environmental conditions [70–74]. Here, we suggest that considering a different and non-exclusive mechanism involving the effect of cell size on metabolic performance may help to better understand sex or developmental differences in tolerance to stressful temperatures.

Our results showed that flies that are engaged in flight and climbing activities lowered their heat tolerance when exposed to hypoxic air, indicating that tissue oxygenation can affect heat tolerance. In agreement with this, Lighton [75] reported that hypoxia led to a decrease in the upper critical thermal maxima in D. melanogaster. Insect flight relies exclusively on aerobic metabolism [76], indicating the central importance of sustainable oxygen supply to mitochondria in the metabolic performance of flight muscles. Indeed, earlier studies demonstrated a decrease in the flight performance of D. melanogaster in response to lower oxygen levels in the air [77,78]. Altogether, these patterns support the most fundamental postulates of Pörtner's theory [15], although obtaining conclusive evidence of whether insufficient oxygen delivery shapes insect heat tolerance in ecologically relevant environments would require further studies with specific experimental designs and measurements. However, some of our results showed inconsistencies with these patterns. Specifically, the effect of oxygen conditions on heat tolerance was incomparably more pronounced in the Mnt1-control tandem than in the rictorΔ2-control tandem. For the latter tandem, we also found that the large-celled genetic form (control) had higher heat tolerance (rather than lower) than the small-celled form (rictorΔ2 mutant). Furthermore, for both tandems, the results showed that regardless of the cell size characteristics of the mutant and its control, oxygen conditions had a similar quantitative effect on heat tolerance in each genetic form. Additionally, oxygen conditions affected the heat tolerance in males and females in a similar way, regardless of the sex differences in cell size. By contrast, given the TOCS, we expected large-celled forms to exhibit higher sensitivity to hypoxia than their small-celled counterparts.

Overall, our results supported the importance of metabolic constraints in shaping upper thermal limits but simultaneously demonstrated that existing theories do not satisfactorily accommodate all mechanisms involved in this phenomenon. Some of the inconsistencies in our results may be due to the knockdown of the rictor and Mnt genes themselves because the ‘loss of function’ mutations in the genes of cell cycle machinery are likely to lead to complex and even detrimental metabolic effects [79,80]. In humans, for example, knockdown of the CDKN2A gene, a product of which plays a pivotal role in cell cycle regulation, leads to pathological increases in insulin levels [81]. The TOR/insulin pathways, to which we relate our study by using mutants in the rictor and Mnt genes, are highly evolutionarily conserved, and are the key regulators of the cell cycle and metabolism [82–84] that remain under strong selective pressure in natural populations. For example, the activity of the TOR/insulin pathways has evolved latitudinal clines in conjunction with the cell size and body size of D. melanogaster [4,6]. Evidence shows that, apart from tissue growth regulation, the product of the rictor gene contributes to the nervous system's anatomy [85,86], suggesting that the non-functional rictor gene could lead to deteriorated motor functions and flight performance. The deficit of Rictor protein in rictorΔ2 mutants reduces the functioning of TOR complex 2, which phosphorylates several AGC family kinases, including Akt, which is known to modulate metabolism [87]. Interestingly, activation of TOR complex 2 promotes the cell-autonomous formation of cytoprotective ribonucleoprotein particles under heat stress [88], suggesting more direct links between deactivation of TOR complex 2 in rictorΔ2 mutants and their lower heat tolerance in our experiment. Compared to the rictor gene, the metabolic effects of mutations in the Mnt gene are less studied. We know that the transcriptional repressor Mnt (absent in our Mnt1 mutant) antagonizes the transcription factor Myc [89], which modulates ribosomal protein synthesis in response to TOR activation [90–92]. Therefore, the Mnt1 flies in our experiment were characterized by reduced downregulation of downstream TOR/insulin signalling, suggesting increased anabolic activity that competes with heat tolerance mechanisms for metabolic resources. Drosophila melanogaster flies with mutations in this gene show reduced longevity [42], indicating metabolic costs imposed by mutations in the Mnt gene, but to our knowledge, their response to heat stress has never been studied.

Physiological limits that provide tolerance of certain thermal gradients and fluctuations vary considerably across the tree of life, and the mechanisms shaping these limits seem to be evolutionarily conserved [93,94]. This, combined with the human-mediated impacts on the levels of species distribution and population sizes [95–98], suggests that physiological constraints may reduce organisms' adaptive adjustments to the rapid pace of climatic change [99]. Indeed, the analysis of the geographical distribution of Drosophila species and data on their heat tolerance suggested that a surprisingly high number of species experience maximal environmental temperatures that already approach species-specific physiological upper limits, showing increased physiological vulnerability to the effects of global warming. Here, we demonstrated that either downregulation of the TOR/insulin pathway activities (rictorΔ2) or poor suppression of its downstream signalling (Mnt1) are associated with decreased heat tolerance in adult D. melanogaster, with female flies showing lower heat tolerance than male flies. This suggested that metabolic processes regulated by the TOR/insulin pathways and by sex-dependent mechanisms, including changes in cell size, can be critically involved in setting ectotherms’ upper thermal limits. Furthermore, our results suggested that for ectotherms engaged in metabolically demanding activities, such as flight in insects, these limits may decrease with a reduced ability to deliver adequate amounts of oxygen to mitochondria, for example, caused by poor environmental oxygen supply. Our results also helped to highlight knowledge gaps by showing inconsistencies between observed empirical patterns and the existing theories. In addition to the need for mastering theories, we also highlighted the need for mastering research systems, which will improve the ability to test theories. On the one hand, we have shown evidence consistent with the views that cell size and oxygen availability affect the thermal tolerance of D. melanogaster. On the other hand, our study system (Mnt1 and rictorΔ2 mutants) challenged us to isolate the metabolic effects of cell size change from other metabolic effects of the mutations under study. This emphasizes a widespread constraint—the absence of easy-to-use study systems (e.g. mutant lines) for examining differences in metabolic effects of cell size. Not surprisingly, the mainstream of genetic modification of organisms for research optimizes mutant traits to address health concerns, such as tumorigenesis [100], neurodegenerative disorders and developmental abnormalities [101] or therapeutic discovery [102], rather than to explore evolutionary questions about the importance of cell size. Consequently, most previous studies investigating the metabolic performance of organisms have neglected the natural variability in cellular composition. Nevertheless, recent findings highlight the impact of this variability on the metabolic performance of organisms, indicating the need to develop more appropriate research models to investigate this phenomenon in depth. Such models would help to better understand the evolutionary significance of the cellular composition of organisms.

Acknowledgements

We thank Pawel Szabla and Natalia Szabla for providing programming support to expedite the creation of the database from raw data. We thank two anonymous reviewers and editors of the special issue for their constructive guidance that helped us improve the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics

This work did not require ethical approval from a human subject or animal welfare committee.

Data accessibility

The raw data and R code can be accessed in electronic supplementary material [103].

Declaration of AI use

We have not used AI-assisted technologies in creating this article.

Authors' Contributions

V.P.: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; Ł.S.: investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing; E.S.: investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing; A.M.L.: supervision, visualization, writing—review and editing; M.C.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Center in Poland (OPUS grant no. 2016/21/B/NZ8/00303 to M.C.) and supported by funds of the Institute of Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Biology, Jagiellonian University (grant no. N18/DBS/000022).

References

- 1.McKay CP. 2014. Requirements and limits for life in the context of exoplanets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 12 628-12 633. ( 10.1073/pnas.1304212111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarke A. 2014. The thermal limits to life on Earth. Int. J. Astrobiol. 13, 141-154. ( 10.1017/S1473550413000438) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoback WW, Stanley DW. 2001. Mini review: insects in hypoxia. J. Insect. Physiol. 47, 533-542. ( 10.1016/S0022-1910(00)00153-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Jong G, Bochdanovits Z. 2003. Latitudinal clines in Drosophila melanogaster: body size, allozyme frequencies, inversion frequencies, and the insulin-signalling pathway. J. Genet. 82, 207-223. ( 10.1007/BF02715819) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dillon ME, Frazier MR. 2006. Drosophila melanogaster locomotion in cold thin air. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 364-371. ( 10.1242/jeb.01999) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabian DK, Kapun M, Nolte V, Kofler R, Schmidt PS, Schlötterer C, Flatt T. 2012. Genome-wide patterns of latitudinal differentiation among populations of Drosophila melanogaster from North America. Mol. Ecol. 21, 4748-4769. ( 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05731.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angilletta MJ Jr. 2009. Thermal adaptation: a theoretical and empirical synthesis. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kellermann V, Overgaard J, Hoffmann AA, Fljøgaard C, Svenning J-C, Loeschcke V. 2012. Upper thermal limits of Drosophila are linked to species distributions and strongly constrained phylogenetically. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 16 228-16 233. ( 10.1073/pnas.1207553109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pörtner HO, et al. 2022. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ( 10.1017/9781009325844) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terblanche JS, Clusella-Trullas S, Deere JA, Chown SL. 2008. Thermal tolerance in a south-east African population of the tsetse fly Glossina pallidipes (Diptera, Glossinidae): implications for forecasting climate change impacts. J. Insect. Physiol. 54, 114-127. ( 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2007.08.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett JM, et al. 2018. Data descriptor: GlobTherm, a global database on thermal tolerances for aquatic and terrestrial organisms. Sci. Data 5, 180022. ( 10.1038/sdata.2018.22) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacMillan HA. 2019. Dissecting cause from consequence: a systematic approach to thermal limits. J. Exp. Biol. 222, jeb191593. ( 10.1242/jeb.191593) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huey RB, Stevenson RD. 1979. Integrating thermal physiology and ecology of ectotherms: a discussion of approaches. Integr. Comp. Biol. 19, 357-366. ( 10.1093/icb/19.1.357) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pauly D, Lam ME. 2023. Too hot or too cold: the biochemical basis of temperature-size rules for fish and other ectotherms. Environ. Biol. Fishes 106, 1519-1527. ( 10.1007/s10641-023-01429-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pörtner HO. 2001. Climate change and temperature-dependent biogeography: oxygen limitation of thermal tolerance in animals. Naturwissenschaften 88, 137-146. ( 10.1007/s001140100216) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pörtner H-O, Bock C, Mark FC. 2017. Oxygen- and capacity-limited thermal tolerance: bridging ecology and physiology. J. Exp. Biol. 220, 2685-2696. ( 10.1242/jeb.134585) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boardman L, Terblanche JS. 2015. Oxygen safety margins set thermal limits in an insect model system. J. Exp. Biol. 218, 1677-1685. ( 10.1242/jeb.120261) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verberk WCEP, Overgaard J, Ern R, Bayley M, Wang T, Boardman L, Terblanche JS. 2016. Does oxygen limit thermal tolerance in arthropods? A critical review of current evidence. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 192, 64-78. ( 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.10.020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arendt J. 2007. Ecological correlates of body size in relation to cell size and cell number: patterns in flies, fish, fruits and foliage. Biol. Rev. 82, 241-256. ( 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00013.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walczyńska A, Franch-Gras L, Serra M. 2017. Empirical evidence for fast temperature-dependent body size evolution in rotifers. Hydrobiologia 796, 191-200. ( 10.1007/s10750-017-3206-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kierat J, Szentgyörgyi H, Czarnoleski M, Woyciechowski M. 2017. The thermal environment of the nest affects body and cell size in the solitary red mason bee (Osmia bicornis L.). J. Therm. Biol. 68, 39-44. ( 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2016.11.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Czarnoleski M, Labecka AM, Starostová Z, Sikorska A, Bonda-Ostaszewska E, Woch K, Kubička L, Kratochvíl L, Kozłowski J. 2017. Not all cells are equal: effects of temperature and sex on the size of different cell types in the Madagascar ground gecko Paroedura picta. Biol. Open 6, 1149-1154. ( 10.1242/bio.025817) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Czarnoleski M, Labecka AM, Dragosz-Kluska D, Pis T, Pawlik K, Kapustka F, Kilarski WM, Kozłowski J. 2018. Concerted evolution of body mass and cell size: similar patterns among species of birds (Galliformes) and mammals (Rodentia). Biol. Open 7, bio029603. ( 10.1242/bio.029603) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schramm BW, Labecka AM, Gudowska A, Antoł A, Sikorska A, Szabla N, Bauchinger U, Kozlowski J, Czarnoleski M. 2021. Concerted evolution of body mass, cell size and metabolic rate among carabid beetles. J. Insect. Physiol. 132, 104272. ( 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2021.104272) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walczyńska A, Labecka AM, Sobczyk M, Czarnoleski M, Kozłowski J. 2015. The temperature–size rule in Lecane inermis (Rotifera) is adaptive and driven by nuclei size adjustment to temperature and oxygen combinations. J. Therm. Biol. 54, 78-85. ( 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2014.11.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szlachcic E, Czarnoleski M. 2021. Thermal and oxygen flight sensitivity in ageing Drosophila melanogaster flies: links to rapamycin-induced cell size changes. Biology (Basel) 10, 861. ( 10.3390/biology10090861) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verberk WCEP, Sandker JF, van de Pol ILE, Urbina MA, Wilson RW, McKenzie DJ, Leiva FP. 2022. Body mass and cell size shape the tolerance of fishes to low oxygen in a temperature-dependent manner. Glob. Chang. Biol. 28, 5695-5707. ( 10.1111/gcb.16319) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szarski H. 1983. Cell size and the concept of wasteful and frugal evolutionary strategies. J. Theor. Biol. 105, 201-209. ( 10.1016/S0022-5193(83)80002-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woods HA. 1999. Egg-mass size and cell size: effects of temperature on oxygen distribution. Am. Zool. 39, 244-252. ( 10.1093/icb/39.2.244) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kozłowski J, Konarzewski M, Gawelczyk AT. 2003. Cell size as a link between noncoding DNA and metabolic rate scaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 14 080-14 085. ( 10.1073/pnas.2334605100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atkinson D, Morley SA, Hughes RN. 2006. From cells to colonies: at what levels of body organization does the ‘temperature-size rule’ apply? Evol. Dev. 8, 202-214. ( 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2006.00090.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Czarnoleski M, Cooper BS, Kierat J, Angilletta MJ. 2013. Flies developed small bodies and small cells in warm and in thermally fluctuating environments. J. Exp. Biol. 216, 2896-2901. ( 10.1242/jeb.083535) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hermaniuk A, Rybacki M, Taylor JRE. 2017. Metabolic rate of diploid and triploid edible frog Pelophylax esculentus correlates inversely with cell size in tadpoles but not in frogs. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 90, 230-239. ( 10.1086/689408) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kozłowski J, Konarzewski M, Czarnoleski M. 2020. Coevolution of body size and metabolic rate in vertebrates: a life-history perspective. Biol. Rev. 95, 1393-1417. ( 10.1111/brv.12615) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glazier DS. 2022. How metabolic rate relates to cell size. Biology (Basel) 11, 1106. ( 10.3390/biology11081106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harrison JF, Roberts SP. 2000. Flight respiration and energetics. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 62, 179-205. ( 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.179) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dudley R. 2002. The biomechanics of insect flight: form, function, evolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harrison JF, Kaiser A, VandenBrooks JM. 2010. Atmospheric oxygen level and the evolution of insect body size. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 1937-1946. ( 10.1098/rspb.2010.0001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoback WW, Stanley DW. 2001. Insects in hypoxia. J. Insect. Physiol. 47, 533-542. ( 10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2017)06-1879-06) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Culver DC, Pipan T. 2018. Insects in caves. In Insect biodiversity: science and society (eds Foottit RG, Adler PH), pp. 123-152. Chichester, UK: Willey-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hietakangas V, Cohen SM. 2007. Re-evaluating AKT regulation: role of TOR complex 2 in tissue growth. Genes Dev. 21, 632-637. ( 10.1101/gad.416307) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loo LWM, Secombe J, Little JT, Carlos L-S, Yost C, Cheng P-F, Flynn EM, Edgar BA, Eisenman RN. 2005. The transcriptional repressor dMnt is a regulator of growth in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 7078-7091. ( 10.1128/mcb.25.16.7078-7091.2005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. 2006. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell 124, 471-484. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grewal SS. 2009. Insulin/TOR signaling in growth and homeostasis: a view from the fly world. Int. J. Biochem. 41, 1006-1010. ( 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.10.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parisi F, et al. 2011. Drosophila insulin and target of rapamycin (TOR) pathways regulate GSK3 beta activity to control Myc stability and determine Myc expression in vivo. BMC Biol. 9, 65. ( 10.1186/1741-7007-9-65) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Privalova V, Labecka AM, Szlachcic E, Sikorska A, Czarnoleski M. 2023. Systemic changes in cell size throughout the body of Drosophila melanogaster associated with mutations in molecular cell cycle regulators. Sci. Rep. 13, 7565. ( 10.1038/s41598-023-34674-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jørgensen LB, Malte H, Overgaard J. 2019. How to assess Drosophila heat tolerance: unifying static and dynamic tolerance assays to predict heat distribution limits. Funct. Ecol. 33, 629-642. ( 10.1111/1365-2435.13279) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huey RB, Crill WD, Kingsolver JG, Weber KE. 1992. A method for rapid measurement of heat or cold resistance of small insects. Funct. Ecol. 6, 489-494. ( 10.2307/2389288) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Terblanche JS, Hoffmann AA, Mitchell KA, Rako L, Le Roux PC, Chown SL. 2011. Ecologically relevant measures of tolerance to potentially lethal temperatures. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 3713-3725. ( 10.1242/jeb.061283) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.RStudio Team. 2022. RStudio: Integrated development environment for R. Version 4.1.3.

- 51.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker BM, Walker SC. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1-48. ( 10.18637/jss.v067.i01) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB. 2017. lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82, 1-26. ( 10.18637/JSS.V082.I13) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lenth RV. 2022. emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R package version 1.7.3. See https://rdrr.io/cran/emmeans/.

- 54.Wickham H. 2016. Ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Partridge L, Barrie B, Fowler K, French V. 1994. Evolution and development of body size and cell size in Drosophila melanogaster in response to temperature. Evolution (NY) 48, 1269-1276. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1994.tb05311.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Azevedo RBR, French V, Partridge L. 2002. Temperature modulates epidermal cell size in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Insect. Physiol. 48, 231-237. ( 10.1016/S0022-1910(01)00168-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Czarnoleski M, Dragosz-Kluska D, Angilletta MJ. 2015. Flies developed smaller cells when temperature fluctuated more frequently. J. Therm. Biol. 54, 106-110. ( 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2014.09.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adrian GJ, Czarnoleski M, Angilletta MJ. 2016. Flies evolved small bodies and cells at high or fluctuating temperatures. Ecol. Evol. 6, 7991-7996. ( 10.1002/ece3.2534) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Verspagen N, Leiva FP, Janssen IM, Verberk WCEP. 2020. Effects of developmental plasticity on heat tolerance may be mediated by changes in cell size in Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Sci. 27, 1244-1256. ( 10.1111/1744-7917.12742) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leiva FP, Boerrigter JGJ, Verberk WCEP. 2023. The role of cell size in shaping responses to oxygen and temperature in fruit flies. Funct. Ecol. 37, 1269-1279. ( 10.1111/1365-2435.14294) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.James AC, Azevedo RBR, Partridge L. 1995. Cellular basis and developmental timing in a size cline of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 140, 659-666. ( 10.1093/genetics/140.2.659) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zwaan BJ, Azevedo RBR, James AC, Van't Lnad J, Partridge L. 2000. Cellular basis of wing size variation in Drosophila melanogaster: a comparison of latitudinal clines on two continents. Heredity (Edinb) 84, 338-347. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2540.2000.00677.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Szlachcic E, Dańko MJ, Czarnoleski M. 2023. Rapamycin supplementation of Drosophila melanogaster larvae results in less viable adults with smaller cells. R. Soc. Open Sci. 10, 230080. ( 10.1098/rsos.230080) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Szlachcic E, Labecka AM, Privalova V, Sikorska A, Czarnoleski M. 2023. Systemic orchestration of cell size throughout the body: influence of sex and rapamycin exposure in Drosophila melanogaster. Biol. Lett. 19, 20220611. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2022.0611) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Testa ND, Ghosh SM, Shingleton AW. 2013. Sex-specific weight loss mediates sexual size dimorphism in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE 8, e58936. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0058936) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sawala A, Gould AP. 2017. The sex of specific neurons controls female body growth in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 15, e2002252. ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.2002252) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hitoshi Y, Ishikawa Y, Matsuo T. 2016. Intraspecific variation in heat tolerance of Drosophila prolongata (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 51, 515-520. ( 10.1007/s13355-016-0425-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kapila R, Kashyap M, Gulati A, Narasimhan A, Poddar S, Mukhopadhaya A, Prasad NG. 2021. Evolution of sex-specific heat stress tolerance and larval Hsp70 expression in populations of Drosophila melanogaster adapted to larval crowding. J. Evol. Biol. 34, 1376-1385. ( 10.1111/jeb.13897) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pottier P, Burke S, Drobniak SM, Lagisz M, Nakagawa S. 2021. Sexual (in)equality? A meta-analysis of sex differences in thermal acclimation capacity across ectotherms. Funct. Ecol. 35, 2663-2678. ( 10.1111/1365-2435.13899) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sørensen JG, Nielsen MM, Kruhøffer M, Justesen J, Loeschcke V. 2005. Full genome gene expression analysis of the heat stress response in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Stress Chaperones 10, 312-328. ( 10.1379/CSC-128R1.1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baird NA, Turnbull DW, Johnson EA. 2006. Induction of the heat shock pathway during hypoxia requires regulation of heat shock factor by hypoxia-inducible factor-1. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 38 675-38 681. ( 10.1074/jbc.M608013200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kristensen TN, Kjeldal H, Schou MF, Nielsen JL. 2016. Proteomic data reveal a physiological basis for costs and benefits associated with thermal acclimation. J. Exp. Biol. 219, 969-976. ( 10.1242/jeb.132696) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harrison JF, Greenlee KJ, Verberk WCEP. 2018. Functional hypoxia in insects: definition, assessment, and consequences for physiology, ecology, and evolution. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 63, 303-325. ( 10.1146/annurev-ento-020117) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Levesque KD, Wright PA, Bernier NJ. 2019. Cross talk without cross tolerance: effect of rearing temperature on the hypoxia response of embryonic zebrafish. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 92, 349-364. ( 10.1086/703178) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lighton JRB. 2007. Hot hypoxic flies: whole-organism interactions between hypoxic and thermal stressors in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Therm. Biol. 32, 134-143. ( 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2007.01.009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Harrison JF, Woods HA, Roberts SP. 2012. Ecological and environmental physiology of insects. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shiehzadegan S, Le Vinh Thuy J, Szabla N, Angilletta MJ, VandenBrooks JM. 2017. More oxygen during development enhanced flight performance but not thermal tolerance of Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE 12, e0177827. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0177827) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Privalova V, Szlachcic E, Sobczyk Ł, Szabla N, Czarnoleski M. 2021. Oxygen dependence of flight performance in ageing Drosophila melanogaster. Biology (Basel) 10, 327. ( 10.3390/biology10040327) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Niu W, Li Z, Zhan W, Iyer VR, Marcotte EM. 2008. Mechanisms of cell cycle control revealed by a systematic and quantitative overexpression screen in S. cerevisiae. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000120. ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000120) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kaplon J, van Dam L, Peeper D. 2015. Two-way communication between the metabolic and cell cycle machineries: the molecular basis. Cell Cycle 14, 2022-2032. ( 10.1080/15384101.2015.1044172) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pal A, et al. 2016. Loss-of-function mutations in the cell-cycle control gene CDKN2A impact on glucose homeostasis in humans. Diabetes 65, 527-533. ( 10.2337/db15-0602) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jia K, Chen D, Riddle DL. 2004. The TOR pathway interacts with the insulin signaling pathway to regulate C. elegans larval development, metabolism and life span. Development 131, 3897-3906. ( 10.1242/dev.01255) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bhaskar PT, Hay N. 2007. The two TORCs and Akt. Dev. Cell 12, 487-502. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Texada MJ, Koyama T, Rewitz K. 2020. Regulation of body size and growth control. Genetics 216, 269-313. ( 10.1534/genetics.120.303095) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Koike-Kumagai M, Yasunaga KI, Morikawa R, Kanamori T, Emoto K. 2009. The target of rapamycin complex 2 controls dendritic tiling of Drosophila sensory neurons through the Tricornered kinase signalling pathway. EMBO J. 28, 3879-3892. ( 10.1038/emboj.2009.312) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shimono K, Fujishima K, Nomura T, Ohashi M, Usui T, Kengaku M, Toyoda A, Uemura T. 2014. An evolutionarily conserved protein CHORD regulates scaling of dendritic arbors with body size. Sci. Rep. 4, 4415. ( 10.1038/srep04415) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Miao R, Fang X, Wei J, Wu H, Wang X, Tian J. 2022. Akt: a potential drug target for metabolic syndrome. Front. Physiol. 13, 822333. ( 10.3389/fphys.2022.822333) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jevtov I, et al. 2015. TORC2 mediates the heat stress response in Drosophila by promoting the formation of stress granules. J. Cell Sci. 128, 2497-2508. ( 10.1242/jcs.168724) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang G, Hurlin PJ. 2017. MNT and emerging concepts of MNT-MYC antagonism. Genes (Basel) 8, 83. ( 10.3390/genes8020083) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pierce SB, Yost C, Anderson SAR, Flynn EM, Delrow J, Eisenman RN. 2008. Drosophila growth and development in the absence of dMyc and dMnt. Dev. Biol. 315, 303-316. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.026) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bellosta P, Gallant P. 2010. Myc function in Drosophila. Genes Cancer 1, 542-546. ( 10.1177/1947601910377490) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Grifoni D, Bellosta P. 2014. Drosophila Myc: a master regulator of cellular performance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1849, 570-581. ( 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.06.021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Joern A, Laws AN. 2013. Ecological mechanisms underlying arthropod species diversity in grasslands. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 58, 19-36. ( 10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153540) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Poff NL, Larson EI, Salerno PE, Morton SG, Kondratieff BC, Flecker AS, Zamudio KR, Funk WC. 2018. Extreme streams: species persistence and genomic change in montane insect populations across a flooding gradient. Ecol. Lett. 21, 525-535. ( 10.1111/ele.12918) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Parmesan C. 2006. Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. 37, 637-669. ( 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110100) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hitch AT, Leberg PL. 2007. Breeding distributions of North American bird species moving north as a result of climate change. Conserv. Biol. 21, 534-539. ( 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00609.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Møller PA, Rubolini D, Lehikoinen E. 2008. Populations of migratory bird species that did not show a phenological response to climate change are declining. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 16 195-16 200. ( 10.1073/pnas.0803825105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Maclean IMD, Wilson RJ. 2011. Recent ecological responses to climate change support predictions of high extinction risk. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 12 337-12 342. ( 10.1073/pnas.1017352108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bennett JM, et al. 2021. The evolution of critical thermal limits of life on Earth. Nat. Commun. 12, 1198. ( 10.1038/s41467-021-21263-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mirzoyan Z, Sollazzo M, Allocca M, Valenza AM, Grifoni D, Bellosta P. 2019. Drosophila melanogaster: a model organism to study cancer. Front. Genet. 10, 51. ( 10.3389/fgene.2019.00051) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hales KG, Korey CA, Larracuente AM, Roberts DM. 2015. Genetics on the fly: a primer on the Drosophila model system. Genetics 201, 815-842. ( 10.1534/genetics.115.183392) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pandey UB, Nichols CD. 2011. Human disease models in Drosophila melanogaster and the role of the fly in therapeutic drug discovery. Pharmacol. Rev. 63, 411-436. ( 10.1124/pr.110.003293) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Privalova V, Sobczyk Ł, Szlachcic E, Labecka AM, Czarnoleski M. 2023. Heat tolerance in Drosophila melanogaster is influenced by oxygen conditions and mutations in cell size control pathways. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6949049) [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data and R code can be accessed in electronic supplementary material [103].