Abstract

The marine environment represents a rich yet challenging source of novel therapeutics. These challenges are best exemplified by the manzamine class of alkaloids, featuring potent bioactivities, difficult procurement, and a biosynthetic pathway that has eluded characterization for over three decades. This review highlights postulated biogenic pathways toward the manzamines, evaluated in terms of current biosynthetic knowledge and metabolic precedent.

1. Introduction

Marine natural products are an important source of bioactive and therapeutically relevant compounds.1 Compared to natural products of terrestrial origins, however, far fewer marine natural products or derivatives thereof have progressed into the clinic.2 This disparity results, in part, from limited access to marine specimens and from the lack of scalable synthetic approaches to produce these compounds in the laboratory. One possible solution to this challenge involves leveraging biosynthetic or semi-synthetic tactics to prepare marine natural products and their derivatives. Identifying marine natural product biosynthetic pathways can be difficult, however, because the organism(s) responsible for producing specific marine compounds is often uncertain.3 This lack of knowledge impedes genomic-based efforts to identify biosynthetic gene clusters and prevents systematic biological evaluation of marine-derived metabolites.

The manzamine alkaloids are prototypic examples of marine natural products with an elusive biosynthetic origin (Fig. 1). The founding member of this family, manzamine A (7), was isolated more than 35 years ago from a Japanese sponge, and was demonstrated to potently inhibit growth of P388 leukemia cells.4 Subsequent reports uncovered new derivatives and expanded the medicinal repertoire of manzamine A to include antimalarial,5 antibacterial,6 and antifungal7 activities. Over the last four decades, the manzamine family has been expanded to include more than 200 members, with diverse structural examples including the halicyclamines (1), cyclostellettamines8 (2), saraines9 (3), nakadomarin10 (4), and madangamines11 (5) as well as ircinal A12 (6), an apparent biosynthetic precursor to 7. Synthetic chemists were inspired to establish a laboratory preparation of 7, culminating in several elegant total syntheses from the groups of Winkler, Martin, Fukuyama, and Dixon.13-16 While heroic and instructive synthetic studies, all four of these efforts produced a total of 11.9 mg of 7, highlighting not only the molecular complexity, but also the difficulties in procuring large quantities of these alkaloids through multi-step synthesis. Over the past 20 years, several other family members of this group have succumbed to total synthesis, including nakadomarin A,17-24 Sarain A,25,26 haliclonacyclamine C,27 madangamines A–E,28,29 and epi-tetradehydrohalicyclamine B.30 In general, though, these compounds do not display bioactivities as potent or as diverse as manzamine A.

Fig. 1.

Representative manzamine alkaloids.

While scalability for some manzamine targets has improved over time,18 the major contribution from synthesis has been the discovery of novel reactivity and invention of strategic design. Generally speaking, synthetic efforts have not enabled an exhaustive biological evaluation of these alkaloids, again highlighting limitations associated with procurement. As several other natural products have been produced biosynthetically in a scalable manner,31,32 the question of how one could obtain manzamines and related alkaloids through bioengineering remains outstanding. To consider this possibility, evaluation of their possible sources and mechanism of biosynthetic production must be critically assessed. To date, no manzamine biosynthetic gene clusters have been identified and no enzymes capable of transforming putative manzamine intermediates have been uncovered.33 As a result, manzamine biosynthesis remains enigmatic; yet these compounds continue to attract broad scientific attention due to their diverse biological activities against many classic medicinal chemistry targets.5,6,34-37 In this review, we highlight recent advances from the fields of natural product discovery, chemical synthesis and microbiology that provide new clues to the biosynthesis of the manzamine alkaloids.

2. Reevaluating past biosynthetic postulates

Initially assigned as having “no obvious biogenic origin,” Baldwin and Whitehead noticed the internal symmetry of the scaffold and proposed a relatively simple biosynthetic pathway towards 7 (Fig. 2A). This proposal involved condensation of two equivalents of acrolein, ammonia, and a 10-carbon dialdehyde to generate a bis-dihydropyridine scaffold (8). A subsequent intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction of this intermediate generates the bicyclic manzamine core (see 9), followed by further oxidation and β-carboline incorporation.38 Notably, Baldwin and co-workers were able to demonstrate the spontaneity of the proposed Diels–Alder step in a dilute buffered solution to obtain keramaphidin B, the reduced form of 9, albeit in low yield (0.3%). This observation suggests that a putative Diels–Alderase might be dispensable for assembly of keramaphidin B and manzamine A. However, as the major side-products aside from 9 in this biomimetic transformation were resultant of dihydropyridine disproportionation, this step may benefit from proteinogenic control or enzymatic recycling of macrocyclic diamine precursors related to 8.39

Fig. 2.

(A) Baldwin and coworkers' hypothesis. (B) Marazano variation.

The initial condensation step of acrolein, ammonia, and an aldehyde, akin to the Chichibabin pyridine synthesis,40 was a convenient and efficient synthetic proposal. However, the evidence for widespread existence of these building blocks is generally lacking in the biochemical literature. Acrolein, a known toxin owing to its broad reactivity with many biomolecules, has no precedent as a biosynthetic building block. Instead, acrolein is usually generated as a by-product of catabolic processes and is rapidly metabolized to less toxic species.41-43 Similarly, an alkyl dialdehyde appears to be an unlikely biosynthetic monomer. Medium and long chain alkyl dialdehydes, as required by the pathway, have not been reported as standalone species, likely due to their innate reactivity and lack of precedent for obvious biological function. Ammonia has strong precedent within biological systems given its ubiquitous role in nitrogen fixation, but it is seldom encountered as a sole entity in secondary metabolism. Instead, amines found in natural products are generally derived from abundant biological nitrogen sources, often via transamination reactions.44,45

A modification to the Baldwin proposal was presented by Marazano and co-workers, in which malondialdehyde (10) and an amino aldehyde (11) replace the Baldwin precursors (Fig. 2B).46 While the plausibility of this substitution also suffers from analogous biological instability, its invocation putatively avoids direct synthesis of a dihydropyridine species, which is susceptible to redox-driven disproportionation reactions that are unproductive towards the generation of 9. Notably, the aminopentadienal (12) species postulated by Marazano would allow synthetic access to the ring systems found in both the halicyclamines and manzamines via 13. In contrast to the Baldwin precursors, for which direct evidence has yet to emerge, the general viability of aminopentadienal species is supported by the biosynthesis of quinolinate. In this pathway, cyclization of 2-amino-3-carboxymuconic semialdehyde is thought to occur nonenzymatically.47 Aside from this observation, the general lack of experimental support for other putative precursors in the Baldwin and Marazano proposals justifies re-evaluating manzamine biosynthesis in light of present-day knowledge.

3. Consideration of traditional polyketide pathways

Each of the representative manzamine alkaloids highlighted in Fig. 1 are notable for the presence of a long-chain alkyl component. An obvious choice for the origin of this feature is a polyketide synthase-based pathway. Indeed, polyketide synthases (PKS) have emerged as a key enzyme family in marine secondary metabolism and alkaloid biosynthesis.48 PKS complexes assemble long-chain carbogens through the iterative condensation of simple carbonyl extender units (e.g. malonyl) by the action of acyl-carrier proteins. Following construction of the linear carbon backbone, the metabolite is tailored via oxidation, cyclization, or amination.44 While a comprehensive review of PKS pathways is beyond the scope of this work, here we consider two recently established PKS systems responsible for biosynthesizing manzamine-like scaffolds.

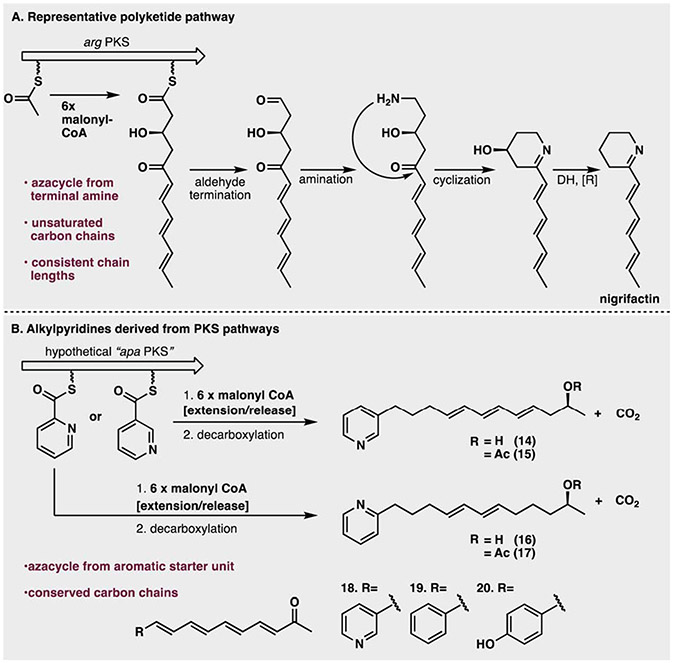

The biosynthesis of the argimycins by Streptomyces argillaceus is an example of a relatively simple PKS system that produces alkyl piperidine natural products. These compounds can be considered structural homologs to the alkyl pyridine moiety found in manzamines (Fig. 3A).49 In the argimycin pathway, an acetyl-CoA starter unit is extended by six malonyl-CoA units to generate a C12 chain. The polyene chain is terminated and released as an aldehyde, which is subsequently aminated and spontaneously cyclizes. Importantly, this pathway leads to 2-substituted azacycles, whereas the putative manzamine A biosynthesis involves a 3-azacyclic precursor. The arg cluster produces eleven structurally distinct argimycins. However, these structures differ only in their post-PKS modifications, not in the carbon-count of the polyketide backbone.49 Similarly, the pattern and position of alkyl chain reductions observed in the various argimycins are conserved. In contrast, a massive diversity of chain lengths and unsaturation patterns have been reported in manzamine alkaloid family members.50

Fig. 3.

(A) Argimycin PKS (adapted from ref. 49). (B) Postulated haminol PKS and related congeners.

The PKS-based biosynthesis of the haminols (14–15) provides a possible solution to the problem of generating 3-alkyl substituted pyridines.51 Isotope feeding studies support nicotinic acid as the nitrogenous starter unit for the haminol pathway. Acetate- and/or malonate-based extension then generates the long-chain alkyl group (Fig. 3B). Examination of several structures related to the haminols, namely the cyano-bacterial phormidinines A and B52 (16–17), and sea slug-derived navenones A–C,53 (18–20) supports the existence of homologous PKS pathways that utilize other aromatic carbonyls as starter units. These include but are likely not limited to picolinic, benzoic or phenolic acids. Like the argimycins, these examples retain consistent unsaturation patterns, chain lengths, and terminal ketones characteristic of their polyketide origins. Such features are not readily apparent within the varied manzamine scaffolds reported to date.

Based on these alkyl-pyridine pathways, several aspects inherent to the manzamine family appear to be outside the scope of canonical polyketide biosynthesis. Firstly, the hypothetical PKS would have to be massively promiscuous in its alkyl carbon count to account for the variety of chain lengths observed in the manzamines, ranging from 8–16 carbons.50 Secondly, the pathway would have to be broadly reductive. Aside from the haminols, no manzamine relatives have been reported to contain polyketide artifacts such as ketones or alcohols. Furthermore, many dihydro and tetrahydropyridine manzamine alkaloids have been characterized. These natural products would require a post-extension reduction of the pyridine ring. Dimerization of the resulting monomeric alkylpyridines would require head-to-tail N-alkylation of pyridine rings, constituting a novel reaction in natural product biosynthesis. Lastly, except for a few rare examples, PKS chain extension produces metabolites with E olefins,54 in direct contrast to the mostly Z configurations observed in the higher-order manzamine alkaloids. While a polyketide-based biogenesis of manzamine alkaloids cannot be ruled out – particularly the monomeric alkylpyridines – such a pathway would appear to require several transformations that are outside the current scope of canonical polyketide-based biosynthetic clusters. These inconsistencies warrant an exploration of alternative possibilities.

4. The fatty acid polyamine pathway

If some examples of the manzamines appear to fall outside the scope of a traditional assembly-line biosynthetic process, is there an alternative pathway that may comprehensively explain the structural class? One potential explanation for the vast diversity of reported alkyl chain lengths of manzamines suggests they may be scavenged from the free fatty acid pool destined for primary metabolic functions. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that alkenes in many manzamine alkaloids are present in the Z configuration, the predominant form of unsaturated fatty acids produced by fatty acid desaturases.55 Likewise, the fatty acid hypothesis is consistent with the requirement for di-functionalization of the alkyl chain termini, as ω-oxidation is a process generally attributed to FAS pathways.56

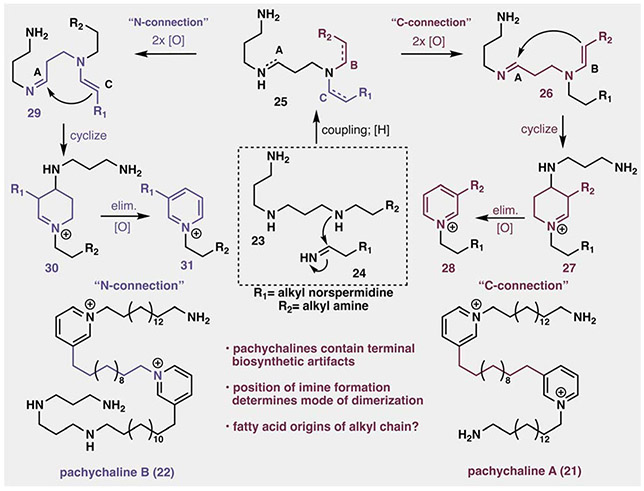

Similarly, if pre-formed pyridine sources like nicotinic acid present biosynthetic obstacles, is there a more broadly applicable nitrogen source to consider? A promising revision was provided upon isolation and characterization of the pachychaline class of linear 3-alkylpyridines (21–22, Fig. 4) by the Thomas group, noting the conserved terminal amines and norspermidine residues present in these structures. The authors proposed a robust biosynthetic mechanism for their formation, utilizing norspermidine as the key 3-carbon nitrogenous unit (Fig. 4).57,58 For example, polyamine 23, presumably derived from the amination of a fatty acid-like species with norspermidine, would be coupled with the oxidized terminal amine of a homologous monomer (24), and, following reduction, would produce the key tertiary polyamine 25. This intermediate can diverge towards two related pyridinium endpoints (28 and 31), termed the “N-” or “C-connection” mechanisms. In one scenario, oxidation at carbons A and B would produce enamine 26, which would cyclize to form iminium 27. Subsequent elimination and oxidation would result in pyridinium 28, which bears a C3–C3 linkage between pyridiniums, evident in the structure of 21. Alternatively, oxidation of carbons A and C in 25 would result in generation of enamine 29, which would undergo an analogous cyclization and oxidation sequence resulting in pyridinium 31 (via 30), producing the “N-connection” observed in pachychaline B (22), as well as most oligomeric manzamine congeners.

Fig. 4.

Thomas biosynthetic proposal toward the pachychalines (adapted from ref. 57 and 58).

More broadly, differences in length and unsaturation pattern of the alkyl component (e.g. R2 in 23) of the described pathway allows for extrapolation to the full suite of manzamine alkaloids (see Fig. 5). The linear polyamine substrate 32 may be transformed along either unimolecular, dimeric, trimeric, or oligomeric pathways. Intramolecular pyridine formation following oxidations at C6 and C10 would yield the theonelladin class of monomeric alkylpyridines (33) following the aforementioned mechanism (vide supra). Oxidation at the ω-carbon allows for subsequent reductive N9 macrocyclization giving the motuporamine class (see 34). The same transformation using a 10-carbon unsaturated alkyl component (see 35) may be envisioned as the precursor of Manzamine C (36), requiring a further oxidation of the norspermidine residue and oxidative incorporation of a tryptamine unit. At another end of the spectrum, the trimeric route is first enabled by two N9 couplings between three equivalents of 32. Cyclization of both N9 and N9′ onto C6 and C6′, respectively, engenders the formation of the bis(pyridinium) found in pachychaline B (22) or hypothetical linear trimer 37, incorporating a 13-carbon substrate. An additional oxidative macrocyclization of 37 followed by pyridinium formation would generate viscosamine (38). Finally, a head-to-tail dimerization of 32 with a 10-carbon unsaturated species would provide a putative precursor for bis(dihydropyridine) formation (see 39). This intermediate can proceed through the Diels–Alder cycloaddition to intercept the Baldwin pathway towards 7. The analogous dimerization with a 13-carbon saturated substrate would provide 40, a putative precursor to cyclostellettamine A (2), which would arise after oxidation of the dihydropyridine units to the observed pyridiniums.

Fig. 5.

Expansion of the polyamine pathway (adapted from ref. 58).

Specifically, the putative dimerization/cyclization fate of the polyamine precursors that would intercept the Baldwin pathway is depicted in Fig. 6. Reductive coupling of fatty acid 41 and norspermidine (42) would result in monomer 43. Bis-oxidation of this monomer would dimerize and cyclize via the “N-connection” pathway, extruding ammonia and 1,3-diaminopropane (44). The bis-dihydropyridine (8) produced through this dimerization was shown by Baldwin39 to undergo Diels–Alder cycloaddition to “pre-keramaphidin B” (9), followed by further oxidations and ring-closure in the downstream genesis of manzamine A (7), providing an attractively simple revision to the pathway.

Fig. 6.

Modified biosynthetic pathway toward manzamine A.

5. A microbial foothold for future investigations?

A major advance in manzamine biosynthesis appeared to have been made in 2014, when Hill and co-workers isolated a sponge associated actinomycete, Micromonospora sp. M42, capable of producing manzamine A.33 This bacterium produced manzamine A in small quantities (~1 mg L−1), but unlike many secondary metabolites, it failed to accumulate in the bacterium's stationary phase. Instead, manzamine A (7) was produced at a very specific time, early in the growth cycle, and then became undetectable as cell densities increased. Unfortunately, the microorganism lost the ability to produce manzamine A following extended culturing, raising the possibility that the associated genes were transcriptionally silenced or encoded on an extrachromosomal plasmid that was subsequently lost. Despite these limitations, M42 represents an attractive resource for future biosynthetic investigations. Leveraging published synthetic routes to several putative manzamine biosynthetic intermediates and feeding these advanced intermediates to M42 could prove useful in validating individual steps in the pathway.

A draft sequence of the M42 genome is publicly available, however these data were obtained using older sequencing technologies that produce short reads (<0.8 kb) requiring extensive assembly to generate the entire 6.7 Mb genome. Micromonospora are bacteria containing genomes with high GC content and repetitive biosynthetic gene clusters, severely impeding genome assembly and identification of discrete biosynthetic genes.59 The lack of a high-quality genome sequence limits the ability to interrogate manzamine biosynthesis in M42 using modern gene cluster mining and genetic disruption methods.60 Thus, revisiting the M42 genome using modern sequencing platforms is warranted.

An intriguing structural feature of the manzamine family members are their various oxidation levels, especially within the azacyclic rings.50 This observation is consistent with widespread oxidative biosynthetic transformations of both linear and macrocyclic alkaloids within the marine community.50 Potentially, these transformations represent attempts by one or more organisms to oxidatively metabolize the alkaloids to less toxic species, similar to vertebrate catabolism of pharmaceutical agents by P450 enzymes in the liver.61 A corollary of this postulate is that manzamine derivatives at the highest oxidation level may represent biosynthetic “dead-ends”, incapable of further facile oxidative biotransformation. This possibility could be tested by feeding cultures of Micromonospora sp. M42 with isotopically labelled compounds in the putative biosynthetic pathway (e.g. cyclostellettamine A).

6. Summary and concluding remarks

In summary, we highlight a revised biosynthetic postulate for the manzamine alkaloids, which merges fatty acid synthesis with polyamine metabolism. This revised proposal offers a potential explanation for why manzamine biosynthesis has remained elusive for decades. It is apparently distinct from other well-characterized PKS- and NRPS-based biosynthetic processes, which are often used to query genomic data sets for discovery of new biosynthetic gene clusters. To this end, it may be useful to look more broadly for predicted, colocalized polyamine and fatty acid genes within sponge-associated microbial genomic sequences in future searches for manzamine biosynthetic enzymes.

8. Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in part, by Florida State University CRC grant number 046346. We also acknowledge Vitalii Basistyi (FSU) for his editorial contributions.

Biographies

Alexander T. Piwko was raised in Connecticut and obtained his BSc in Chemistry in 2019 at Texas A&M University, where he worked with cross-chiral aptamers in the lab of Prof. Jonathan Sczepanski. His current research in Prof. Brian Miller's lab at Florida State University is focused on marine natural products and their biosynthesis.

Brian G. Miller received his PhD in Biochemistry and Biophysics from the University of North Carolina, under the supervision of Prof. Richard Wolfenden. He then moved to the University of Wisconsin as a Damon-Runyon Cancer Research Postdoctoral Fellow in the laboratory of Prof. Ronald Raines. In 2005, he began his independent career as a Professor in the Chemistry and Biochemistry Department at Florida State University, where his group currently investigates the molecular and evolutionary origins of enzyme catalysis and regulation.

Joel M. Smith was born and raised in Raleigh, NC. He graduated in 2010 with a BS in Chemistry and Music from Furman University prior to earning his PhD under the advisory of Prof. Neil K. Garg at UCLA in 2015. He then conducted studies in the laboratory of Prof. Phil S. Baran at Scripps Research as an Arnold Beckman Postdoctoral Fellow until 2018. He then started his career at Florida State University, where he is currently an Assistant Professor of Chemistry. His lab is engaged in the total synthesis of alkaloid natural products and the invention of novel chemical transformations.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

9 Notes and references

- 1.Jiménez C, Marine Natural Products in Medicinal Chemistry, ACS Med. Chem. Lett, 2018, 9(10), 959–961, DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molinski TF, Dalisay DS, Lievens SL and Saludes JP, Drug Development from Marine Natural Products, Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery, 2009, 8(1), 69–85, DOI: 10.1038/nrd2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lane AL and Moore BS, A Sea of Biosynthesis: Marine Natural Products Meet the Molecular Age, Nat. Prod. Rep, 2011, 28(2), 411–428, DOI: 10.1039/C0NP90032J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakai R, Higa T, Jefford CW and Bernardinelli G, Manzamine A, a Novel Antitumor Alkaloid from a Sponge, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1986, 108(20), 6404–6405, DOI: 10.1021/ja00280a055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ang KKH, Holmes MJ, Higa T, Hamann MT and Kara UAK, In Vivo Antimalarial Activity of the Beta-Carboline Alkaloid Manzamine A, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother, 2000, 44(6), 1645–1649, DOI: 10.1128/aac.44.6.1645-1649.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao KV, Santarsiero BD, Mesecar AD, Schinazi RF, Tekwani BL and Hamann MT, New Manzamine Alkaloids with Activity against Infectious and Tropical Parasitic Diseases from an Indonesian Sponge, J. Nat. Prod, 2003, 66(6), 823–828, DOI: 10.1021/np020592u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yousaf M, Hammond NL, Peng J, Wahyuono S, McIntosh KA, Charman WN, Mayer AMS and Hamann MT, New Manzamine Alkaloids from an Indo-Pacific Sponge. Pharmacokinetics, Oral Availability, and the Significant Activity of Several Manzamines against HIV-I, AIDS Opportunistic Infections, and Inflammatory Diseases, J. Med. Chem, 2004, 47(14), 3512–3517, DOI: 10.1021/jm030475b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fusetani N, Asai N, Matsunaga S, Honda K, Yasumuro K and Cyclostellettamines A-F, Pyridine Alkaloids Which Inhibit Binding of Methyl Quinuclidinyl Benzilate (QNB) to Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors, from the Marine Sponge, Stelletta Maxima, Tetrahedron Lett., 1994, 35(23), 3967–3970, DOI: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)76715-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cimino G, Stefano SD, Scognamiglio G, Sodano G and Trivellone E, Sarains: A New Class of Alkaloids from the Marine Sponge Reniera Sarai, Bull. Soc. Chim. Belg, 1986, 95(9–10), 783–800, DOI: 10.1002/bscb.19860950907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi J, Watanabe D, Kawasaki N, Tsuda M and A. Nakadomarin, a Novel Hexacyclic Manzamine-Related Alkaloid from Amphimedon Sponge, J. Org. Chem, 1997, 62(26), 9236–9239, DOI: 10.1021/jo9715377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kong F, Andersen RJ and Allen TM, Madangamine A, a Novel Cytotoxic Alkaloid from the Marine Sponge Xestospongia Ingens, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1994, 116(13), 6007–6008, DOI: 10.1021/ja00092a077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kondo K, Shigemori H, Kikuchi Y, Ishibashi M, Sasaki T and Kobayashi J, Ircinals A and B from the Okinawan Marine Sponge Ircinia Sp.: Plausible Biogenetic Precursors of Manzamine Alkaloids, J. Org. Chem, 1992, 57(8), 2480–2483, DOI: 10.1021/jo00034a052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winkler JD and Axten JM, The First Total Syntheses of Ircinol A, Ircinal A, and Manzamines A and D, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1998, 120(25), 6425–6426, DOI: 10.1021/ja981303k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Humphrey JM, Liao Y, Ali A, Rein T, Wong Y-L, Chen H-J, Courtney AK and Martin SF, Enantioselective Total Syntheses of Manzamine A and Related Alkaloids, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2002, 124(29), 8584–8592, DOI: 10.1021/ja0202964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toma T, Kita Y and Fukuyama T, Total Synthesis of (+)-Manzamine A, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2010, 132(30), 10233–10235, DOI: 10.1021/ja103721s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jakubec P, Hawkins A, Felzmann W and Dixon D, J. Total Synthesis of Manzamine A and Related Alkaloids, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2012, 134(42), 17482–17485, DOI: 10.1021/ja308826x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jakubec P, Cockfield DM and Dixon DJ, Total Synthesis of (−)-Nakadomarin A, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2009, 131(46), 16632–16633, DOI: 10.1021/ja908399s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boeckman RK Jr, Wang H, Rugg KW, Genung NE, Chen K and Ryder TR, A Scalable Total Synthesis of (−)-Nakadomarin A, Org. Lett, 2016, 18(23), 6136–6139, DOI: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b03137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonazzi S, Cheng B, Wzorek JS and Evans DA, Total Synthesis of (−)-Nakadomarin A, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2013, 135(25), 9338–9341, DOI: 10.1021/ja404673s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark JS and Xu C, Total Synthesis of (−)-Nakadomarin A, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2016, 55(13), 4332–4335, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201600990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kyle AF, Jakubec P, Cockfield DM, Cleator E, Skidmore J and Dixon DJ, Total Synthesis of (−)-Nakadomarin A, Chem. Commun, 2011, 47(36), 10037–10039, DOI: 10.1039/C1CC13665H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nilson MG and Funk RL, Total Synthesis of (−)-Nakadomarin A, Org. Lett, 2010, 12(21), 4912–4915 DOI: 10.1021/ol102079z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagata T, Nakagawa M and Nishida A, The First Total Synthesis of Nakadomarin A, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2003, 125(25), 7484–7485, DOI: 10.1021/ja034464j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young IS and Kerr MA, Total Synthesis of (+)-Nakadomarin A, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2007, 129(5), 1465–1469, DOI: 10.1021/ja068047t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker MH, Chua P, Downham R, Douglas CJ, Garg NK, Hiebert S, Jaroch S, Matsuoka RT, Middleton JA, Ng FW and Overman LE, Total Synthesis of (−)-Sarain A, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2007, 129(39), 11987–12002, DOI: 10.1021/ja074300t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garg NK, Hiebert S and Overman LE, Total Synthesis of (−)-Sarain A, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2006, 45(18), 2912–2915, DOI: 10.1002/anie.200600417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith BJ and Sulikowski GA, Total Synthesis of (±)-Haliclonacyclamine C, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2010, 49(9), 1599–1602, DOI: 10.1002/anie.200905732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ballette R, Pérez M, Proto S, Amat M and Bosch J, Total Synthesis of (+)-Madangamine D, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2014, 53(24), 6202–6205, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201402263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suto T, Yanagita Y, Nagashima Y, Takikawa S, Kurosu Y, Matsuo N, Sato T and Chida N, Unified Total Synthesis of Madangamines A, C, and E, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2017, 139(8), 2952–2955, DOI: 10.1021/jacs.7b00807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dalling AG, Späth G and Fürstner A, Total Synthesis of the Tetracyclic Pyridinium Alkaloid Epi-Tetradehydrohalicyclamine B, Angew. Chem, 2022, 134(41), e202209651, DOI: 10.1002/ange.202209651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhuo Y, Zhang T, Wang Q, Cruz-Morales P, Zhang B, Liu M, Barona-Gómez F and Zhang L, Synthetic Biology of Avermectin for Production Improvement and Structure Diversification, Biotechnol. J, 2014, 9(3), 316–325, DOI: 10.1002/biot.201200383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu M and Wright GD, Heterologous Expression-Facilitated Natural Products' Discovery in Actinomycetes, J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol, 2019, 46(3–4), 415–431, DOI: 10.1007/s10295-018-2097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waters AL, Peraud O, Kasanah N, Sims JW, Kothalawala N, Anderson MA, Abbas SH, Rao KV, Jupally VR, Kelly M, Dass A, Hill RT and Hamann MT, An Analysis of the Sponge Acanthostrongylophora Igens' Microbiome Yields an Actinomycete That Produces the Natural Product Manzamine A, Front. Mar. Sci, 2014, 1, 1–15, DOI: 10.3389/fmars.2014.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashok P, Ganguly S and Murugesan S, Manzamine Alkaloids: Isolation, Cytotoxicity, Antimalarial Activity and SAR Studies, Drug Discovery Today, 2014, 19(11), 1781–1791, DOI: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kallifatidis G, Hoepfner D, Jaeg T, Guzmán EA and Wright AE, The Marine Natural Product Manzamine A Targets Vacuolar ATPases and Inhibits Autophagy in Pancreatic Cancer Cells, Mar. Drugs, 2013, 11(9), 3500–3516, DOI: 10.3390/md11093500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simithy J, Fuanta NR, Alturki M, Hobrath JV, Wahba AE, Pina I, Rath J, Hamann MT, DeRuiter J, Goodwin DC and Calderón AI, Slow-Binding Inhibition of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Shikimate Kinase by Manzamine Alkaloids, Biochemistry, 2018, 57(32), 4923–4933, DOI: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rao KV, Kasanah N, Wahyuono S, Tekwani BL, Schinazi RF and Hamann MT, Three New Manzamine Alkaloids from a Common Indonesian Sponge and Their Activity against Infectious and Tropical Parasitic Diseases, J. Nat. Prod, 2004, 67(8), 1314–1318, DOI: 10.1021/np0400095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baldwin JE and Whitehead RC, On the Biosynthesis of Manzamines, Tetrahedron Lett., 1992, 33(15), 2059–2062, DOI: 10.1016/0040-4039(92)88141-Q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baldwin J, Claridge T, Culshaw A, Heupel F, Lee V, Spring DR and Whitehead R, Studies on the Biomimetic Synthesis of the Manzamine Alkaloids, Chem.–Eur. J, 2016, 5(11), 3154–3161, DOI: . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chichibabin Pyridine Synthesis, https://www.drugfuture.com/Organic_Name_Reactions/topics/ONR_CD_XML/ONR073.htm, accessed 2022-06-28.

- 41.Serjak WC, Day WH, Van Lanen JM and Boruff CS, Acrolein Production by Bacteria Found in Distillery Grain Mashes, Appl. Microbiol, 1954, 2(1), 14–20, DOI: 10.1128/am.2.1.14-20.1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stevens JF and Maier CS, Acrolein: Sources, Metabolism, and Biomolecular Interactions Relevant to Human Health and Disease, Mol. Nutr. Food Res, 2008, 52(1), 7–25, DOI: 10.1002/mnfr.200700412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang J, Sturla S, Lacroix C and Schwab C, Gut Microbial Glycerol Metabolism as an Endogenous Acrolein Source, mBio, 2018, 9(1), e019477, DOI: 10.1128/mBio.01947-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Awodi UR, Ronan JL, Masschelein J, de los Santos ELC and Challis GL, Thioester Reduction and Aldehyde Transamination Are Universal Steps in Actinobacterial Polyketide Alkaloid Biosynthesis, Chem. Sci, 2017, 8(1), 411–415, DOI: 10.1039/C6SC02803A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lichman BR, The Scaffold-Forming Steps of Plant Alkaloid Biosynthesis, Nat. Prod. Rep, 2021, 38(1), 103–129, DOI: 10.1039/D0NP00031K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wypych J-C, Nguyen TM, Nuhant P, Bénéchie M and Marazano C, Further Insight from Model Experiments into a Possible Scenario Concerning the Origin of Manzamine Alkaloids, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2008, 47(29), 5418–5421, DOI: 10.1002/anie.200800488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Colabroy KL and Begley TP, The Pyridine Ring of NAD Is Formed by a Nonenzymatic Pericyclic Reaction, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2005, 127(3), 840–841, DOI: 10.1021/ja0446395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khosla C, Structures and Mechanisms of Polyketide Synthases, J. Org. Chem, 2009, 74(17), 6416–6420, DOI: 10.1021/jo9012089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ye S, Braña AF, González-Sabín J, Morís F, Olano C, Salas JA and Méndez C, New Insights into the Biosynthesis Pathway of Polyketide Alkaloid Argimycins P in Streptomyces Argillaceus, Front. Microbiol, 2018, 9, 252, DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Althagbi HI, Alarif WM, Al-Footy KO and Abdel-Lateff A, Marine-Derived Macrocyclic Alkaloids (MDMAs): Chemical and Biological Diversity, Mar. Drugs, 2020, 18(7), 368, DOI: 10.3390/md18070368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cutignano A, Cimino G, Giordano A, d'Ippolito G and Fontana A, Polyketide Origin of 3-Alkylpyridines in the Marine Mollusc Haminoea Orbignyana, Tetrahedron Lett., 2004, 45(12), 2627–2629, DOI: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.01.138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Teruya T, Kobayashi K, Suenaga K and Kigoshi H, Phormidinines A and B, Novel 2-Alkylpyridine Alkaloids from the Cyanobacterium Phormidium Sp, Tetrahedron Lett., 2005, 46(23), 4001–4003, DOI: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2005.04.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sleeper HL, Fenical W and Navenones A-C, Trail-Breaking Alarm Pheromones from the Marine Opisthobranch Navanax Inermis, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1977, 99(7), 2367–2368, DOI: 10.1021/ja00449a072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alhamadsheh MM, Palaniappan N, DasChouduri S and Reynolds KA, Modular Polyketide Synthases and Cis-Double Bond Formation: Establishment of Activated Cis-3-Cyclohexylpropenoic Acid as the Diketide Intermediate in Phoslactomycin Biosynthesis, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2007, 129(7), 1910–1911, DOI: 10.1021/ja068818t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Los DA and Murata N, Structure and Expression of Fatty Acid Desaturases, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Lipids Lipid Metab, 1998, 1394(1), 3–15, DOI: 10.1016/S0005-2760(98)00091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miura Y, The Biological Significance of ω-Oxidation of Fatty Acids, Proc. Jpn. Acad., Ser. B, 2013, 89(8), 370–382, DOI: 10.2183/pjab.89.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laville R, Thomas OP, Berrue F, Reyes F and Amade P, Pachychalines A–C: Novel 3-Alkylpyridinium Salts from the Marine Sponge Pachychalina Sp, Eur. J. Org. Chem, 2008, 2008(1), 121–125, DOI: 10.1002/ejoc.200700741. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Laville R, Amade P and Thomas OP, 3-Alkylpyridinium Salts from Haplosclerida Marine Sponges: Isolation, Structure Elucidations, and Biosynthetic Considerations, Pure Appl. Chem, 2009, 81(6), 1033–1040, DOI: 10.1351/PAC-CON-08-11-14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carro L, Nouioui I, Sangal V, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Trujillo ME, Montero-Calasanz M. d. C., Sahin N, Smith L, Kim KE, Peluso P, Deshpande S, Woyke T, Shapiro N, Kyrpides NC, Klenk H-P, Göker M and Goodfellow M, Genome-Based Classification of Micromonosporae with a Focus on Their Biotechnological and Ecological Potential, Sci. Rep, 2018, 8(1), 525, DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-17392-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Braesel J, Crnkovic CM, Kunstman KJ, Green SJ, Maienschein-Cline M, Orjala J, Murphy BT and Eustáquio AS, Complete Genome of Micromonospora Sp. Strain B006 Reveals Biosynthetic Potential of a Lake Michigan Actinomycete, J. Nat. Prod, 2018, 81(9), 2057–2068, DOI: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.8b00394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Watkins PB, Drug Metabolism by Cytochromes P450 In The Liver And Small Bowel, Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am, 1992, 21(3), 511–526, DOI: 10.1016/S0889-8553(21)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]