Abstract

Before the predicted March 2020 surge of COVID-19, US healthcare organizations were charged with developing resource allocation policies. We assessed policy preparedness and substantive triage criteria within existing policies using a cross-sectional survey distributed to public health personnel and healthcare providers between March 23 and April 23, 2020. Personnel and providers from 68 organizations from 34 US states responded. While half of the organizations did not yet have formal allocation policies, all but 4 were in the process of developing policies. Using manual abstraction and natural language processing, we summarize the origins and features of the policies. Most policies included objective triage criteria, specified inapplicable criteria, separated triage and clinical decision making, detailed reassessment plans, offered an appeals process, and addressed palliative care. All but 1 policy referenced a sequential organ failure assessment score as a triage criterion, and 10 policies categorically excluded patients. Six policies were almost identical, tracing their origins to influenza planning. This sample of policies reflects organizational strategies of exemplar-based policy development and the use of objective criteria in triage decisions, either before or instead of clinical judgment, to support ethical distribution of resources. Future guidance is warranted on how to adapt policies across disease type, choose objective criteria, and specify processes that rely on clinical judgments.

Keywords: COVID-19, Epidemic management/response, Ethics, Ventilator allocation, Triage, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

In early March 2020, leading epidemiological models projected that the surge of COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory failure, caused by SARS-CoV-2, would exceed US intensive care unit (ICU) and ventilator capacities and, thereby, create a public health emergency.1,2 Soon after, frontline reports from Italy attested that providers were compelled by circumstances to refuse ventilators to some patients who, under usual circumstances, would be treated with mechanical ventilation,3 and expectantly treat and palliate older adults, as well as those with preexisting serious illness, without intubation.4 In the United States, Department of Health and Human Services regulations require that all healthcare providers have emergency response plans. Many hospitals and health systems did develop pandemic plans in response to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.5 Nonetheless, the uncommon nature of COVID-19 uncovered gaps in existing plans, demanding rapid revision and development of new plans to address this type of unexpected healthcare shortage.6,7 One study of bioethics program directors found that half of their hospitals had developed policies,8 yet it remains unclear how many US healthcare organizations have prepared a ventilator allocation policy, how many intend to, and to what extent and in which direction a given policy can guide or determine allocation decisions.

Limited research, formal standards, and experiential knowledge applicable to a novel pathogen, combined with the possibility of serious illness, produces numerous ethical and treatment concerns.9 Ventilator allocation, patient triage, and palliative care policies define resource distribution in the context of contingency and crisis standards of care, and, thereby, rely more heavily on individual medical decision makers. Effective policies can not only reduce deaths, but also moral injury and anguish among the healthcare professionals involved in the response. This type of policy development requires planning to build preparedness of hospital systems and staff to assist families as they cope and become more resilient going into their grief processes. Ideally, healthcare providers would have prepared plans during noncrisis periods. Many have the opportunity to do so now to advance their ongoing COVID-19 response and plan for future pandemics.

To facilitate the development of COVID-19 response plans, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response released a checklist on March 5, 2020, which recommended that organizations: “Determine vulnerable supplies and coordinate with vendors and the health care coalition to develop contingency plans/allocation plans” (Activity 2.6); “Develop/update crisis standard of care language in emergency operations plan including the potential for triage decision-making (who, process, communication, considerations)” (Activity 3.26); and “Develop palliative care plans for implementation when needed” (Activity 3.64).10 On March 16, 2020, the Hastings Center published ethical frameworks to further aid institutions responding to COVID-19,11 which included guidelines for institutional ethics services and references to existing Veterans Affairs12 and state13-17 and triage protocols.18,19

We sought to assess US hospital preparedness for ventilator allocation decision making in the weeks surrounding the initial projected surge and to summarize features of hospital triage protocols. We posited that, as of the deployment date of the survey, many healthcare organizations would not yet have developed explicit policies; the policies would have limited actionability and followability due to ambiguous criteria or subjective criteria requiring individual discretion; and the policies and procedures would develop rapidly in response to a novel surge demand. Lastly, we sought to identify when policies adopted explicit criteria, as well as when they allowed clinical judgments to guide complex decisions, perhaps indicating uncertainty in the predictive accuracy of those criteria.

Methods

We distributed a cross-sectional survey to a broad, and potentially overlapping, sampling frame via a convenience sample of public health and healthcare professional society distribution lists, social media, and respondents to the National Survey of Healthcare Organizations and Systems, funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, between March 23 and April 23, 2020. Eligible organizations included health systems, acute care hospitals, provider groups, and state, territorial, tribal, and local health departments/authorities.

All survey items were optional, including: (1) interface to upload policy, protocol, or procedure for ventilator allocation; (2) free-text field to describe the origin of the policy and the process used to develop the policy; (3) institution name; (4) institution address; and (5) respondent name and contact information for a future interview. Survey participation was voluntary, and respondents received no form of compensation.

Inclusion Criteria

We included all policy files submitted, except those with only links to external resources, such as ethical frameworks and state policies, or that did not relate to ventilator allocation.

Analysis

We conducted descriptive analyses of the number and proportion of responding organizational units with existing policies and the sources or origins of those policies. We tracked when policies were made available during our study period, and summarized policy content using manual abstraction and natural language processing. If an organization uploaded more than 1 policy file, we combined them into a single file for analysis.

For the manual abstraction, 1 researcher identified salient features of policies. Using a specifically developed abstraction form, a team of 5 abstracters independently read and abstracted 2 policies. They discussed any disagreements, came to consensus, then clarified the abstraction instructions accordingly (see Supplementary Abstraction Tool, www.liebertpub.com/doi/suppl/10.1089/hs.2020.0166). The team then abstracted the remaining documents, with 2 coders independently coding one-quarter of policies.

For the natural language processing analysis, we collected the submitted policy files (as PDFs, docx, or image files) and processed them into raw text using PyPDF2 (PhaseIt Inc., Miami, FL), python-docx, and Python-tesseract. We then cleaned this raw text and analyzed it with the Natural Language Tool Kit20 and scikit-learn21 to describe the similarity of these texts overall, and over time. Lastly, we compared the manual abstraction results with automated text extraction of short dictionaries composed of the abstraction form terminology to check for false negatives and positives.

Results

Survey Distribution and Response

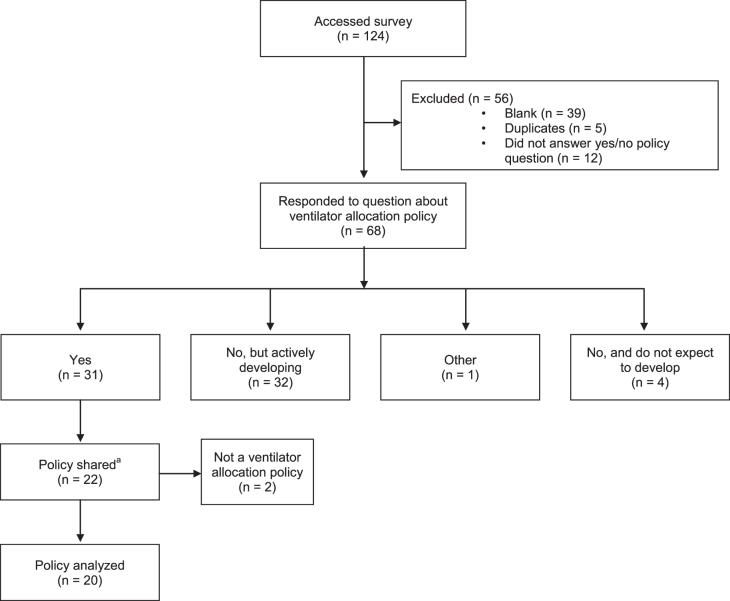

We contacted owners of 12 distribution lists for which we had preexisting professional relationships (Supplementary Table, www.liebertpub.com/doi/suppl/10.1089/hs.2020.0166); 7 agreed to distribute or post the survey link to their membership (American College of Preventive Medicine, Council of Medical Specialty Societies, National Association of County and City Health Officials, American Association of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, Palliative Care Quality Network, and the Global Palliative Care Quality Alliance, and Twitter with the hashtag #PALLICOVID). These distributions occurred on a rolling basis over a period of 4 weeks when the survey was open to an unknown denominator of recipients, resulting in 108 responses. We delivered the survey link to the National Survey of Healthcare Organizations and Systems distribution list of 558 known email addresses on April 1, 2020, with a reminder on April 8, which resulted in 16 additional responses.* We classified responses as complete if they answered whether or not their organization had developed a ventilator allocation policy. In total we received 124 survey responses and 4 emails, 68 (54%) of which were nonduplicate, complete responses (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of survey responses between March 23 and April 23, 2020. aFour policies sent by email are included in the total count (n = 22) for Policy shared.

Characteristics of Respondents

Of the 68 responses, 64 were healthcare systems or acute care hospitals, ranging in the number of ICU beds from 0 to 500 (median 60, IQR = 78); 1 was a community health center, 1 was a hospice, and 2 were public health agencies. Responses were received from 34 US states in all 4 US Census regions: Northeast, Midwest, South, and West (Table 1).

Table 1.

Respondent Organization Characteristics (N = 68)

| Organization Characteristics | n (%) | Median (IQR)) |

|---|---|---|

| ICU beds | 62 (91) | 60 (78) |

| Organization type | ||

| Healthcare system or acute care hospital | 64 (94) | |

| Public health agency | 2 (3) | |

| Other | 2 (3) | |

| Regiona (n = 65) | ||

| Northeast: Massachusetts (1), Maine (1), New Hampshire (2), New Jersey (1), New York (6), Pennsylvania (5), Vermont (1) | 17 (26) | |

| Midwest: Illinois (1), Indiana (1), Michigan (1), Minnesota (3), Missouri (2), Nebraska (1), Ohio (4), Wisconsin (1) | 14 (22) | |

| South: Alabama (1), Arkansas (2), Florida (3), Georgia (1), Kentucky (1), Maryland (1), Mississippi (1), North Carolina (1), Oklahoma (1), Texas (4), Virginia (1), West Virginia (1) | 18 (28) | |

| West: Arizona (1), California (9), Colorado (2), Hawaii (1), Oregon (1), Utah (1), Washington (1) | 16 (24) |

Response did not include a state location (3). Percentages are rounded.

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range.

Ventilator Allocation Policies

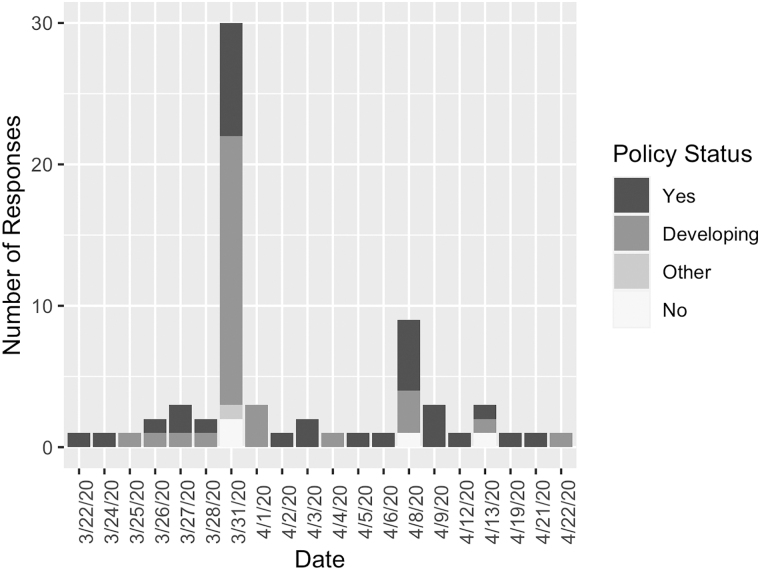

Four (6%) organizations—the community health center, the hospice, and 2 healthcare systems—stated they did not intend to develop a ventilator allocation policy. Thirty-one (46%) organizations reported they did not yet have a policy but were actively developing one, and 33 (48%) reported they did have a policy (Figure 2). Twenty-two respondents shared 1 or more documents. Documents from 20 organizations met inclusion criteria.

Figure 2.

Ventilator allocation policy status survey responses between March 23 and April 23, 2020.

We summarize characteristics of these 20 ventilator allocation policies in Table 2, all of which were from healthcare systems or acute care hospitals and addressed ventilator allocation to patients. None addressed ventilator allocation to hospitals from stockpiles.22 Ten policies specified groups of patients who would be categorically ineligible for a ventilator. Four used exclusion criteria that only exclude those who would typically not be eligible for critical care due to physiologic futility (eg, cardiac arrest without success obtaining a pulse, massive trauma, burns, and catastrophic intracranial bleeding). Notably, these same criteria were referenced indirectly in many of the other 10 policies without explicit exclusion criteria via an inclusion statement such as, “all patients who would, in normal circumstances, be eligible” for critical care. Seven listed conditions that would meet hospice eligibility criteria as explicit exclusions, such as metastatic cancer and end-stage organ failures, as well as dementia (5 of which specified a Functional Assessment Staging scale of 7). One policy excluded patients aged older than 85 years.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Policy Files Shared by Respondents (N = 20)

| Manual Abstraction | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Categorical exclusion criteria | 10 (50) |

| Effort made to make clear what considerations should not be relevant | 14 (70) |

| Criteria are used for patient triagea | |

| Probability of immediate term survivability (eg, SOFA) | 19 (95) |

| Near-term prognosis (near the end of their lives from severe comorbid conditions) | 11 (55) |

| Longer-term life expectancy | 10 (50) |

| Age or life cycle | 11 (55) |

| Essential worker status | 7 (35) |

| Other | 8 (40) |

| Response to mechanical ventilation | 2 (10) |

| Duration of need | 2 (10) |

| Number of dependents | 2 (10) |

| If all else equal, lottery or random allocation system | 4 (20) |

| Authority to make the triage decisions | |

| Triage team | 16 (80) |

| Treating clinician | 1 (5) |

| Triage team and treating clinician | 1 (5) |

| Triage team and other | 1 (5) |

| None specified | 1 (5) |

| Appeals process | 17 (85) |

| Instructions for documentation or recording | 14 (70) |

| Instructions for communication with families | 16 (80) |

| Palliative/supportive care mentioned | 20 (100) |

| Guidance regarding reassessment and/or discontinuation of critical care | 19 (95) |

| Policy Document Text-Based Metrics | Values |

|---|---|

| Lengthb mean (SD) |

6,083 (5,828) |

| Lexical diversityc mean (SD) |

34 (11) |

| Cosine similarity,d median (IQR), and rangee |

|

| Logarithmic |

0.30 (0.12) [0.16-0.99] |

| Natural | 0.41 (0.13) [0.18-1.00] |

Triage criteria are not to be used as exclusion criteria, but as considerations in determining patient priority.

Length is measured by the total count of alphanumeric tokens.

Lexical diversity is the ratio of unique tokens to the total number of tokens as a percentage.

Cosine similarity is the normalized dot product of policy files as term frequency–inverse document frequency (TF–IDF) vectors,  where pi is a row vector of a policy file. Cosine similarly of a given pair of files, k, can range from 0 to 1.

where pi is a row vector of a policy file. Cosine similarly of a given pair of files, k, can range from 0 to 1.

Values reflect IDF reweighting, a constant of 1 added to the numerator and denominator of the IDF, and TF–IDF scores are scaled proportionally by squared average.

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; SOFA, sequential organ failure score; TF–IDF, term frequency–inverse document frequency.

The 10 policies that did not include categorical exclusions instead listed limited near- and long-term prognosis as allowable criteria for triage priority but not exclusion; 7 gave clinical examples and 3 did not. The probability of survival to discharge as measured by sequential organ failure assessment score (SOFA) or modified SOFA (M-SOFA) was the most common criterion for triage in 19 (95%) of 20 policies.

Seven policies specified that essential worker status would be considered, 5 referenced emergency responders and healthcare workers, 3 referenced additional essential staff such as hospital maintenance workers and those who play a critical role in the chain of treating patients and maintaining societal order, and 1 specified healthcare workers only if they could recover in time to return to their duties during the epidemic period.

The majority of policies specified criteria that should not be considered (such as race, socioeconomic status, and disability), separated triage decisions from clinical decision making, offered an appeals process, referenced new documentation procedures, suggested communication with families, and explained periodic clinical reassessment for retriage.

Commonalities included that appeals should be based on questions regarding the accuracy of triage score calculation and/or fidelity of the process, rather than process grounds. Timing of reassessment and reallocation varied from daily (n = 4), 48 hours (n = 4), 48 hours and 120 hours (n = 5), and not specified (n = 7). All policies referenced palliative care for patients when ventilators were withheld or withdrawn.

The policies varied in length considerably, measured by alphanumeric tokens, with moderate variation in the similarity of content, which neither increased nor decreased during our study period, as measured by cosine similarity (Table 2; Supplementary Figure, www.liebertpub.com/doi/suppl/10.1089/hs.2020.0166). Six policies—3 based on Veterans Affairs policy and 3 based on University of Pittsburgh policy—were nearly or completely identical. The most commonly cited origins of policies included preexisting state (n = 5) and federal (Veterans Affairs) policy (n = 3) and the University of Pittsburgh model guidelines promulgated by a March 27, 2020, JAMA publication23 (n = 4; including the latest update to the original policy, contributed by a member of the research team). All of these source policies trace their origins to pandemic flu planning in response to 2009 H1N1 influenza.

The most common organizational committee process described was an ad hoc committee in response to COVID-19 often involving members of an ethics committee (n = 6), and the second most common was a preexisting ethics committee (n = 2). Several referenced preexisting pandemic flu planning processes (n = 7). The most common disciplines involved in committees included ethics (n = 8), administrative leadership (n = 8), palliative care (n = 7), critical care (n = 6), legal (n = 5), and spiritual care (n = 3). We share example quotes in Box 1.

Box 1.

Example Quotes Regarding Policy Origin

| The Cardiopulmonary team came up with a very brief procedure on ventilator allocation. They utilized the University of Pittsburgh protocol on “Allocation of Scarce Critical Care Resources During a Public Health Emergency.” (Acute care hospital, 12 intensive care unit [ICU] beds) |

| Written by myself, who is chair palliative med MD, critical care MD and bioethicist with feedback from CMO [chief medical officer]. Our incident command system team (ICS) reviewed and approved. (Cancer center, 22 ICU beds) |

| Upon activation of our institution's COVID Emergency Response Team, emergency subgroups were formed, including an Ethics Subgroup. The subgroup was led by a senior member of the Ethics Committee and included other members of the Ethics Committee representing hospitalists, chaplaincy, palliative care, psychiatry, critical care clinicians, Executive Physician Leadership, Patient and Family Advisory Council Co-Chairs. The subgroup reviewed existing guidelines from other states/provinces and professional associations, and the Hastings Center, as well as COVID specific publications regarding resource allocation in general and in cancer patient populations in peer-reviewed journals. Upon completion of a draft, they were reviewed and approved by the full Ethics Committee, legal counsel and risk management, institutional operational and clinical Executive Leaders, and Patient and Family Advisory Council. Following approval, [state] guidelines were published and ours were reviewed against them and deemed to be consistent, though specific to our institution. Our guidelines have been communicated to clinical groups. Finally, they were tested in an institutional Mock Emergency table-top exercise including different patient care/resources scarcity scenarios with success. (Acute care hospital, 30 ICU beds) |

| These guidelines were developed in 2010, but recently were vetted by several national VA [Veterans Affairs] groups including ethics and legal. VAs nationally are using these guidelines to develop triage teams who will use SOFA [sequential organ failure assessment] scores to make decisions. When two or more individuals in a category qualify, the VA is recommending a first come first served process—though using a lottery is also acceptable. (VA hospital, ICU beds not reported) |

| [Our state] has had a policy similar to [another state] since 2010 (attachment #3); we updated our policy with a working group (attachment #2) to include explicit language around bias, how we will run our triage committee, as well as updated SOFA scoring. (Health system, 185 ICU beds) |

| This was first designed in 2010 in response to concerns for H1N1, and began modeling out what would happen in the event of a wide-spread flu pandemic. This was designed by an interprofessional team, including clinical ethics; palliative care; pulmonology; emergency medicine; and hospital administration (see document for details). As you can see, the clinical ethics service (CES) played a major role in outlining the goals and values related to scare resource allocation. Since its inception in 2010, it has been edited and updated several times. It has been implemented in the past, most commonly in regards to ECMO [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] circuits. Our hospital has never, to my knowledge, had to activate this guideline for ventilator support until now. (Health system, 250 ICU beds) |

| We are following [our state] Crisis Standards of Care guidance, which is what I have uploaded. [Our institution] has a version that is customized to our particular environment, but the overall guidance and approach aligns with the state document. (Health system, 300 ICU beds) |

Discussion

In this small, nonrepresentative convenience sample, just under half of the healthcare delivery respondents had developed or adopted a policy for ventilator allocation in the weeks surrounding a projected national surge of COVID-19 cases. Many of the prepared organizations had adopted previously vetted federal or state-level policies. Several relied on a model policy published in JAMA days after the start of our study period.23 State-authored allocation policies may incorporate legal standards, contributing to the ease or difficulty of adoption by organizations with single or multistate operations. In contrast, the University of Pittsburgh guidance focuses on medical, ethical, and stakeholder knowledge, facilitating guidance adoption except in instances of explicit legal or organizational disagreement.

Half of the responding organizations did not yet have formal allocation plans, which is inconsistent with the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response checklist released on March 5, 2020.10 However, some of these organizations may have focused on crisis standard of care communications or palliative care planning, and most were actively developing their policies. That nearly half of the responding organizations reported that they were developing a COVID-19 response plan indicates that for many healthcare providers, the existing exemplars do require adaptation before implementation.

Reassuringly, all policies highlighted the importance of palliative care. One marked difference between policies was whether a policy treated life-limiting conditions as categorical exclusions or factored them into the triage point system as decision criteria. Most policies covered a core set of topics, including triage and exclusion criteria, appeals, and communication strategies; these findings support the findings of Antommaria et al.8

Every policy emphasized the use of objective criteria in triage decisions, either before or instead of clinical judgment. All but 1 policy described the use of SOFA or M-SOFA scores as an initial triage criterion for the chance of hospital survival (the University of Pittsburgh model policy described SOFA as an example of an objective measure of the probability of survival to discharge: “SOFA score, or an alternate, validated, objective measure of probability of survival to hospital discharge”). This extensive reliance on SOFA scores suggests that organizations in our sample are prioritizing objective decision making that may be equally applied, even if the scoring function has not been developed for an emerging infection. Even so, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine reported that these scores are “poor predictors of individual patients' survival, particularly for those with primary respiratory failure.”24,25 The incorporation of these scores, even as examples, may reflect organizations' best attempts to avoid inadvertent or systematic discrimination and to comply with applicable disability laws. Moreover, there is no existing scoring system whose accuracy has been established for emerging diseases such as COVID-19.

Notwithstanding these efforts, on March 28, 2020, the Office for Civil Rights issued a bulletin recommending against the use of age or disability as criteria for rationing.26,27 One policy in our sample specified ages over 85 years as an exclusion criterion and several policies specified dementia and other age-related conditions in their criteria. While ethics scholars do not believe it is age discrimination to use disease conditions as exclusion criteria, the Office for Civil Rights concluded that it is invidious discrimination against persons with disabilities to list specific diseases as exclusion criteria. In response, Alabama removed references to specific conditions.28 On April 16, 2020, the Office for Civil Rights approved the Pennsylvania state triage guidelines—based on the University of Pittsburgh model policy—which used life cycle as a tiebreaker, illustrating the complexity of civil rights arguments about what constitutes invidious use of age.

Many of the policies focus on procedural fairness and describe how judgment and consideration processes should apply when objective criteria are unavailable. Complicated procedures are rightly noted but described with minimal detail, indicating the challenge of defining these judgments. For example, some policies described patient reassessment and retriage, but did not define a time interval for these assessments or how to determine an appropriate time interval. Others referenced documentation and recordkeeping, but only a small subset provided new forms for healthcare workers to complete. While many established an appeals process, they left out information about what documentation would be necessary to substantiate a treatment decision if appealed.

These limited descriptions, however, may indicate an alternative strategy. During reassessment, clinicians are advised to assess whether a patient is sufficiently responsive to the ventilator trial. These reassessment judgments rely on a survivability score, clinical judgment, or a combination of both. Prudent planners might reasonably make a conscious decision to not specify duration because there is so much uncertainty about the clinical course of SARS-CoV-2 respiratory failure. Being too specific could lead to worse outcomes if the specification is based on insufficient knowledge of the disease. If current definitions can misperform, individual discretion may be more accurate and ethical.

Organizations appear determined to avoid inadvertent or systematic discrimination, and to comply with applicable disability laws. Usable allocation policy guidance has focused on providing exemplar policies, which require time and deliberation to adapt. In addition, current policies reflect the limited availability of existing objective criteria and the challenge of complying with indefinite guidance on judgment-based processes.

The United States has established national policy (the Final Rule for cadaveric organ donation) and standards (the Uniform Determination of Death Act, though not yet fully enacted by every state) to reduce damages caused by variability in life and death care (eg, poor medical outcomes, imbalanced Medicare reimbursement, litigation costs).29,30 However, unlike these standards for care, the interpretation and implementation of resource allocation policies depend significantly on context. This inclusion of context-dependent decision making is reflected in our sample policies' statements that patient eligibility changes by circumstance, as well as in their reference to crisis standards of care, or “care in the context of disaster.”31 Because organizations can use their discretion to determine relevant contextual features, as well as some crisis circumstances, one allocation policy can produce variable outcomes.

Initial concerns about COVID-19 pointed to inadequate supplies (eg, respirators, ventilators, medical personnel). A technical solution to this problem is an increase in resource supply. Only in the absence of adequate resources for prevention and treatment, do allocation prioritization policies become necessary. Our sample of policies reflects a strong interest in uniform care (incorporation of objective survivability scoring, adoption of exemplar policies with minimal adaptation) and the challenges of circumstantial differences (individual ethics committees, solicitation of public feedback, incorporation of appeals processes).

Our study did have some limitations. We distributed our survey near the onset of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic to healthcare workforce respondents who were likely inundated by pandemic-related demands. We speculate that these circumstances reduced our response rate, which limits the generalizability of our results beyond the reported sample. Nonetheless, similarities among policies, such as the use of SOFA scores, suggests that the limited conclusions drawn from this biased sample may inform the study of US allocation policies broadly. Our convenience sample limits the generalizability of our results, particularly to the organizations that did not respond to our survey request and those that reported policy development intention. Whether organizations acted upon their policy development plans or implemented their policies as planned or otherwise, and what organizations did in the absence of an allocation policy, remains unknown.

Conclusion

Without clear standards for the development of allocation policies for COVID-19, individual organizations reasonably relied on plans developed in response to other diseases (eg, H1N1), state and federal frameworks, and peer organizations. As existing policies were adapted between organizations, healthcare sites could vastly differ in the guidance available to clinical decision makers. Our results suggest that exemplar policy organizations influence the pace of subsequent individualized plans and can further support efforts to strengthen surge preparedness. For example, these organizations could provide guidance or a summary of their planning process, including how they chose objective criteria and how they determined the appropriate level of specification for processes relying on clinical judgments. Exemplar organizations may also contribute recommended evaluation procedures, particularly for triage criteria with known limitations.

Our results suggest a common subset of triage protocol areas that researchers and policymakers can address to improve allocation policies broadly. These include (1) objective criteria to estimate immediate and near-term disease-specific survivability, (2) reassessment and retriage timing, and (3) selection of the next best alternative when no suitable option exists.

The allocation policies in our sample demonstrate rapid advancements of resource allocation planning and draw attention to the persistent challenges of context-dependent triage decisions. Lessons from these initial policy development efforts can progress the ongoing COVID-19 response, including preparation for additional surges and vaccine allocation, and plans for future pandemics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported, in part, by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's (AHRQ's) Comparative Health System Performance Initiative under Grant #1U19HS024075, which studies how healthcare delivery systems promote evidence-based practices and patient-centered outcomes research in delivering care; Levy Cluster in Health Care Delivery, Dartmouth College, the Presidential Scholars Program of Dartmouth College, and by in-kind support from multiple professional organizations. Dr. White was supported by National Institutes of Health-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant K24HL148314.

This distribution list included any respondent to the hospital or health system version of the National Survey of Healthcare Organizations and Systems with an email address on file.

References

- 1. Kissler SM, Tedijanto C, Goldstein E, Grad YH, Lipsitch M. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science. 2020;368(6493):860-868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fink, S. Worst-case estimates for U.S. coronavirus deaths. New York Times. March 13, 2020. Updated March 18, 2020. Accessed April 1, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/13/us/coronavirus-deaths-estimate.html

- 3. Barbaro M. It's like a war. The Daily. March 17, 2020. Accessed April 1, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/17/podcasts/the-daily/italy-coronavirus.html

- 4. Società Italiana Anestesia, Analgesia, Rianimazione e Terapia Intensiva (SIAARTI). Clinical Ethics Recommendations for Admission to Intensive Care and for Withdrawing Treatment in Exceptional Conditions of Imbalance between Needs and Available Resources. Rome: SIAARTI; 2020. https://www.flipsnack.com/SIAARTI/siaarti_-_covid-19_-_clinical_ethics_reccomendations/full-view.html [Google Scholar]

- 5. Medicare and Medicaid programs; emergency preparedness requirements for Medicare and Medicaid participating providers and suppliers. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2016;81(180):63859-64044. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/09/16/2016-21404/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-emergency-preparedness-requirements-for-medicare-and-medicaid [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Klompas M. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): protecting hospitals from the invisible. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):619-620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lipsitch M, Donnelly CA, Fraser C, et al. Potential biases in estimating absolute and relative case-fatality risks during outbreaks. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(7):e0003846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Antommaria AHM, Gibb TS, McGuire AL, et al. Ventilator triage policies during the COVID-19 pandemic at US hospitals associated with members of the Association of Bioethics Program Directors. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(3):188-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mello MM, Persad G, White DB. Respecting disability rights—toward improved crisis standards of care. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(5):e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response. COVID-19 healthcare planning checklist. Accessed April 1, 2020. https://www.phe.gov/emergency/events/COVID19/Documents/COVID-19%20Healthcare%20Planning%20Checklist.pdf

- 11. Berlinger N, Wynia M, Powell T, et al. Ethical framework for health care institutions and guidelines for institutional ethics services responding to the coronavirus pandemic. The Hastings Center. Published March 16, 2020. Accessed March 11, 2021. https://www.thehastingscenter.org/ethicalframeworkcovid19/

- 12. The Pandemic Influenza Ethics Initiative Work Group of the Veterans Health Administration's Center for Ethics in Health Care. Meeting the Challenge of Pandemic Influenza: Ethical Guidance for Leaders and Health Care Professionals in the Veterans Health Administration. Published July 2010. Accessed April 1, 2020. https://www.ethics.va.gov/docs/pandemicflu/Meeting_the_Challenge_of_Pan_Flu-Ethical_Guidance_VHA_20100701.pdf

- 13. New York State Task Force on Life and the Law. Ventilator Allocation Guidelines. Oneonta, NY: New York State Department of Health; 2015. Accessed April 1, 2020. https://www.health.ny.gov/regulations/task_force/reports_publications/docs/ventilator_guidelines.pdf

- 14. Michigan Department of Community Health (MDCH), Office of Public Health Preparedness. Guidelines for Ethical Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources and Services During Public Health Emergencies in Michigan. Version 2.0. Lansing, MI: MDCH; 2012. Accessed April 1, 2020. https://int.nyt.com/data/documenthelper/6857-michigan-triage-guidelines/d95555bb486d68f7007c/optimized/full.pdf

- 15. Minnesota Department of Health (MDH). Minnesota Crisis Standards of Care Framework: Ethical Guidance. St. Paul, MN: MDH; 2020. Accessed April 1, 2020 https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/ep/surge/crisis/framework.pdf

- 16. Minnesota Department of Health (MDH). Minnesota Crisis Standards of Care Framework: Health Care Facility Surge Operations and Crisis Care. St. Paul, MN: MDH; 2020. Accessed March 11, 2021. https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/ep/surge/crisis/framework_healthcare.pdf

- 17. Minnesota Department of Health (MDH). Patient Care Strategies For Scarce Resource Situations. St. Paul, MN: MDH; 2020. Accessed April 1, 2020. https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/ep/surge/crisis/standards.pdf

- 18. Ventilator Document Workgroup, Ethics Subcommittee of the Advisory Committee to the Director. Ethical considerations for decision making regarding allocation of mechanical ventilators during a severe influenza pandemic or other public health emergency. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published July 1, 2011. Accessed April 1, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/about/advisory/pdf/VentDocument_Release.pdf

- 19. White DB, Katz MH, Luce JM, Lo B. Who should receive life support during a public health emergency? Using ethical principles to improve allocation decisions. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(2):132-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bird S, Loper E, Klein, E. Natural Language Processing with Python. Sebastopol, CA: O'Reilly Media Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A, et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. J Mach Learn Res. 2011;12(85):2825-2830. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zaza S, Koonin LM, Ajao A, et al. A conceptual framework for allocation of federally stockpiled ventilators during large-scale public health emergencies. Health Secur. 2016;14(1):1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. White DB, Lo B. A framework for rationing ventilators and critical care beds during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1773-1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Rapid Expert Consultation on Crisis Standards of Care for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2020. Accessed May 4, 2021. 10.17226/25765 [DOI]

- 25. Raschke RA, Agarwal S, Rangan P, Heise CW, Curry SC. Discriminant accuracy of the SOFA score for determining the probable mortality of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation. JAMA. 2021;325(14):1469-1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office for Civil Rights in Action. BULLETIN: civil rights, HIPAA, and the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Accessed May 4, 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr-bulletin-3-28-20.pdf

- 27. Fink S. U.S. Civil Rights Office rejects rationing medical care based on disability, age. New York Times. March 28, 2020. Updated March 30, 2020. Accessed April 1, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/28/us/coronavirus-disabilities-rationing-ventilators-triage.html

- 28. US Department of Health and Human Services. OCR reaches early case resolution with Alabama after it removes discriminatory ventilator triaging guidelines. Updated April 8, 2020. Accessed March 12, 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/04/08/ocr-reaches-early-case-resolution-alabama-after-it-removes-discriminatory-ventilator-triaging.html

- 29. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. 42 CFR §121 (1999).

- 30. President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Defining Death: Medical, Legal and Ethical Issues in the Determination of Death. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1981. Accessed February 11, 2021. https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/bitstream/handle/10822/559345/defining_death.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- 31. Institute of Medicine. Crisis Standards of Care: A Systems Framework for Catastrophic Disaster Response: Volume 1: Introduction and CSC Framework. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. Accessed May 4, 2021. 10.17226/13351 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.