Abstract

Background.

High-resolution impedance manometry (HRiM) is the gold-standard test to accurately diagnose esophageal dysmotility and a component of 24-hour pH testing for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Most commonly, HRiM is performed without sedation in a motility laboratory setting. Occasionally, patients are unable to complete this test due to poor tolerance, inability to traverse the nasopharynx, or inability to navigate through a hypertonic LES or large hiatal hernia. We report our two-center experience utilizing a nasopharyngeal airway (nasal trumpet) to facilitate insertion of the manometry catheter among patients who failed initial placement through the nasopharynx.

Methods.

We used size 24 French nasal trumpets in patients who had failed typical insertion of HRiM catheters during the index unsedated procedure. Topical anesthetic was applied transnasally followed by nasal trumpet insertion. The manometry catheter was introduced through the nasal trumpet, circumventing anatomical barriers to placement.

Results.

We successfully completed HRiM studies in 8 such consecutive patients. Indications for procedure included dysphagia and GERD. Each patient tolerated nasal trumpet use, and there were no complications.

Conclusion.

The addition of the nasal trumpets to the motility lab toolbox can assist with challenging motility catheter placement. This device is inexpensive, widely available, and reduces procedure failure rates due to nasopharyngeal barriers to successful placement.

Keywords: manometry, esophageal motility disorders, nasal trumpet, oropharyngeal airway

Introduction

Esophageal manometry is the gold standard for diagnosing esophageal motility disorders and the initial step in catheter-based 24-hour pH testing.1 High-resolution impedance manometry (HRiM) provides additional qualitative information about esophageal bolus transit.2 Evaluation of dysphagia, regurgitation, atypical chest pain, and reflux may prompt examination with HRiM, as it defines esophageal motor function, and is essential for development of subsequent treatment strategies.3

Although HRiM is indicated to diagnose esophageal dysmotility as a cause for dysphagia, successful completion of the procedure is dependent on patient tolerance and the ability to pass the catheter into the proximal stomach. In a prior study4, 21% of HRiM studies were technically imperfect or failed. At one of our two institutions, imperfect and failed HRiM studies occurred in up to 29% of attempted manometries5, some of whom were referred due to a failure of manometry from another institution. These failures were due to poor patient tolerance (i.e. coughing, gagging) in about 30% of cases, whereas about 50% were due to inability to traverse the nasopharynx, and 20% were caused by inability to traverse the esophagogastric junction (EGJ)/lower esophageal sphincter (LES) or hiatal hernia.5

Troubleshooting techniques to challenging manometry catheter placements are often limited in the motility lab setting. Additional application of topical anesthetics and manipulation of patient positioning are frequently attempted, but results are varied. After initial catheter placement fails, endoscopy-assisted HRiM tests under monitored anesthesia care (MAC)5,6 or moderate sedation7 are reasonable choices that come with patient risk, delay in patient care, and expense. Previously, we have demonstrated success with endoscopy- and MAC-assisted HRiM to diagnose and guide therapy for 14 patients5. We also documented use of the nasal trumpet under MAC and highlighted the scheduling delay for a second HRiM procedure, need for anesthesia and extended endoscopy procedure duration.

Other groups have trialed through-the-scope manometry that showed good correlation of LES pressures to standard manometry. This method was limited by diminished esophageal body peristaltic amplitude that the authors postulated was attributable to dry swallows8. Subsequent groups demonstrated success with direct visualization with video endoscopy and use of an endoscopic-assisted over-the-wire technique to pass the manometry catheter9,10. New technologies such as endoscopic functional lumen imaging probe (EndoFLIP) have been developed to further evaluate esophageal peristalsis11,12. However, EndoFLIP is still regarded as a complementary test for evaluation of disorders of spastic and obstructive esophageal motility disorders.

We report a two-center case series that describes the use of nasal trumpets to salvage previously failed manometry catheter placements in our motility labs.

Methods

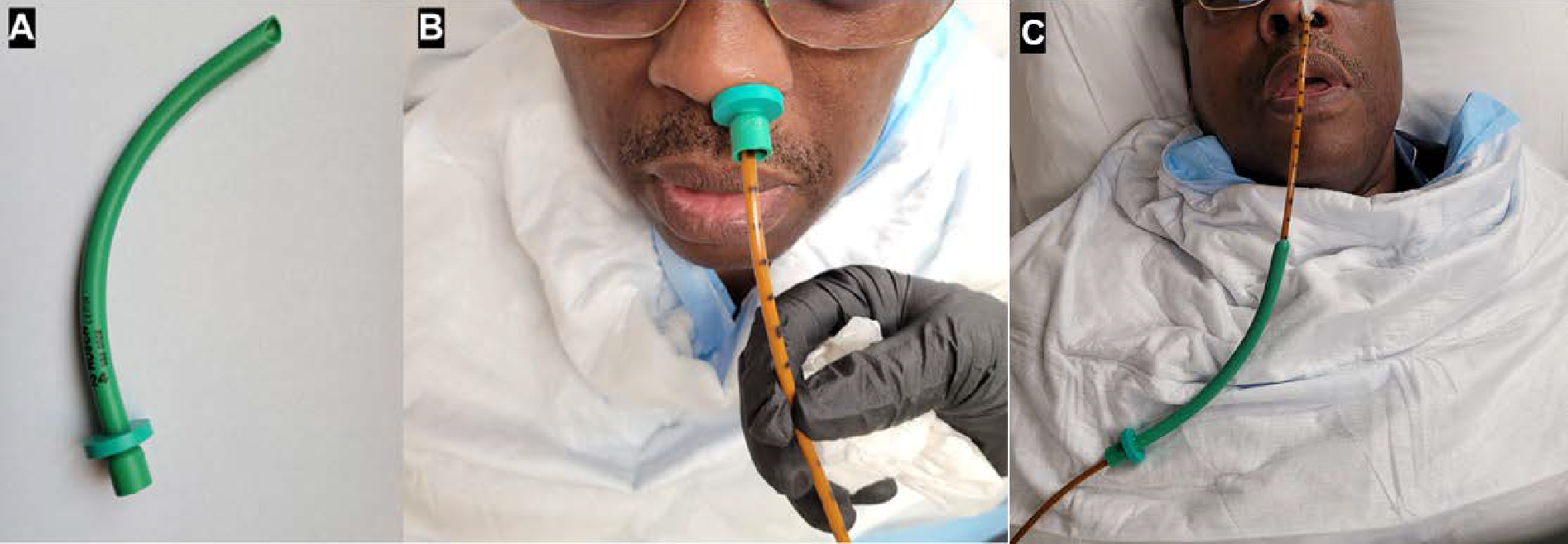

We performed a chart review of esophageal manometry studies performed at two academic centers, the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC), and the Baltimore VA Medical Center (BVAMC) from 4/1/2021 through 9/30/2021. A Diversatek Ultima or INSIGHT g3 HRiM motility catheter was attempted to be passed on all patients. If failed, a nasopharyngeal airway with adjustable flange [size 24 French, OD 8.0 mm (Teleflex Medical Inc.)] was subsequently placed (Figure 1A). This is the smallest diameter nasal trumpet that allows the Diversatek manometry catheter to advance freely without resistance. Nasal trumpets are softer and more flexible (with a natural curve) than the tip of the manometry catheter. By acting as an overtube, nasal trumpet expands the nasal passage and eliminates catheter contact with the sensitive nasopharynx to allow for easier and more comfortable insertion.

Figure 1.

Insertion of HRiM probes via nasal trumpets. A) Nasopharyngeal airway (24 Fr). B) An example of a HRiM probe inserted through the nasopharyngeal airway. C). Nasal trumpet was removed from the nostril prior to HRiM test.

HRiM procedures were performed using a standardized protocol. Patients gargle 10 mL of 2% lidocaine solution for 10 seconds, then 3–5 mL 4% lidocaine viscous solution is applied by syringe transnasally. For patients whom we could not insert the HRiM catheters via either nostril, nasal trumpets were used. Surgical lubricant is applied to nasal trumpet prior to careful insertion into a patient’s nasopharynx. While keeping the patient’s neck in the flexed position, the manometry catheter was inserted through the lumen of the nasal trumpet until it reaches the designed length (Figure 1B). The nasal trumpet was then withdrawn, and the catheter was taped in place before proceeding with testing. Manometry was performed by the same providers: two experienced medical assistants or a nurse practitioner under the supervision of a physician motility specialist.

This study was deemed exempt by the institutional review board at both the University of Maryland Baltimore, and the VA research office at the BVAMC.

Results

Previously, we reported that significant manometry tests failed due to various reasons.5 Most recently, out of 160 HRiM tests, twenty-four (15%) failed. Of these failed attempts, thirteen (54.2%) were due to inability to traverse the nasopharynx; five (20.8%) were due to gagging; four (16.7%) were due to coughing, and two (8.3%) were due to inability to traverse EGJ/LES. For the last eight consecutive patients who failed initial attempt at insertion of the HRiM probe, we started the use of nasal trumpet to complete the tests successfully. Of these 8 patients, 6 were male, and average age of patient was 59.1 ± 11.5.

Five of these eight patients failed initial manometry probe placement due to an inability to traverse the nasopharynx. Two failed due to gagging or coughing, and one failed due to oropharyngeal coiling. Indications for manometry included dysphagia, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and atypical chest pain. 5 patients had normal esophageal motility and 3 were abnormal by Chicago Classification.13,14 One patient subsequently completed a 24-hour pH study. Abnormal esophageal motility patterns identified included EGJ outflow obstruction (EGJOO), hypercontractile (Jackhammer) esophagus, and ineffective esophageal motility. Management of these patients due to the findings of completed manometry studies included medical management with proton pump inhibitor (1), calcium channel blocker (1), interventions with peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) (1) and fundoplication (1) (Table 1). Case presentations of these 8 patients are detailed below.

Table 1.

Demographic data, procedure indications, and outcomes for nasopharyngeal airway-assisted HRiM studies.

| N | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (average; standard deviation) | 59.1 ± 11.5 | |||

| Sex | Male | 6 | 75% | |

| Female | 2 | 25% | ||

| Indication | Dysphagia | 4 | 50% | |

| Heartburn and regurgitation | 2 | 25% | ||

| Chest pain, dysphagia and heartburn | 1 | 12.5% | ||

| Abdominal pain | 1 | 12.5% | ||

| Reason for failed manometry probe insertions | Inability to traverse the nostrils | 5 | 62.5% | |

| Coughing | 1 | 12.5% | ||

| Gagging | 1 | 12.5% | ||

| Oropharyngeal coiling | 1 | 12.5% | ||

| Chicago Classification Diagnosis | Normal | 5 | 62.5% | |

| Jackhammer esophagus | 1 | 12.5% | ||

| EGJOO and Jackhammer | 1 | 12.5% | ||

| Ineffective esophageal motility | 1 | 12.5% | ||

| Management Recommendations | Interventions | POEM | 1 | 12.5% |

| Fundoplication | 1 | 12.5% | ||

| Medical therapy | PPI | 1 | 12.5% | |

| Diltiazem | 1 | 12.5% | ||

| None | 4 | 50% | ||

Patient 1 was a 51-year-old male with a past medical history of post-traumatic stress disorder and GERD referred for worsening heartburn and regurgitation. Symptoms were refractory to twice daily proton pump inhibitor (PPI) plus aluminum hydroxide. EGD was normal. Initial manometry catheter placement failed due to coughing which resolved following nasopharyngeal airway placement. The manometry study was normal, and 24-hour impedance-pH test showed reflux hypersensitivity.

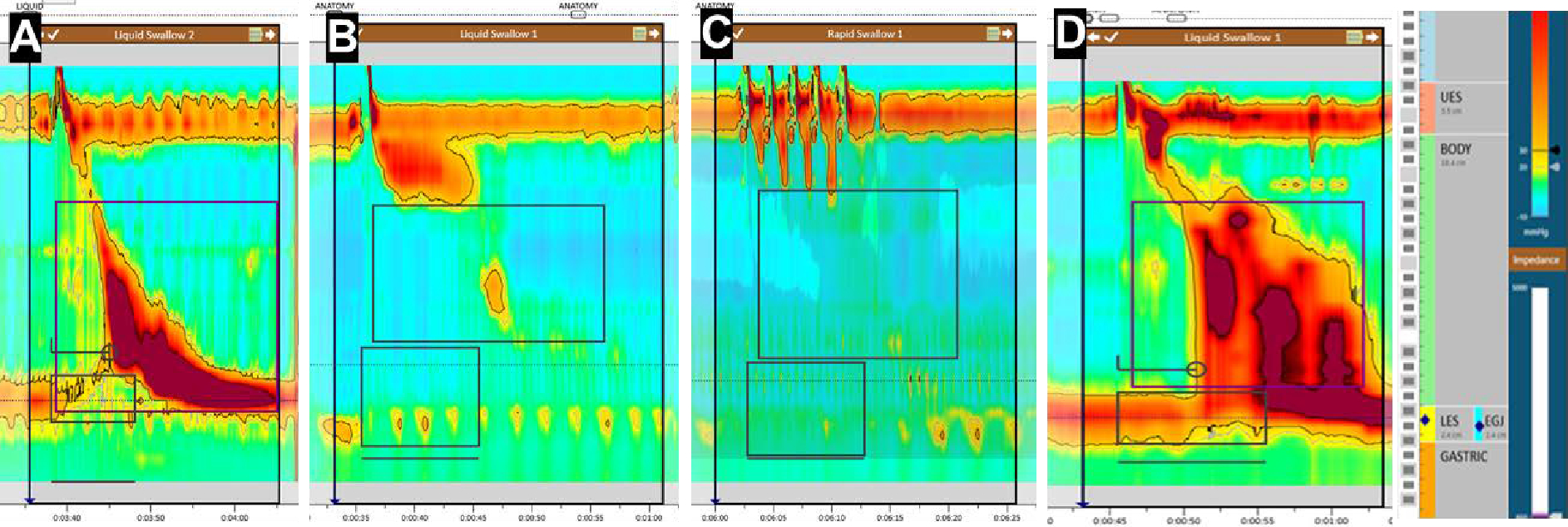

Patient 2 was a 78-year-old male with a past medical history of cirrhosis referred for dysphagia with both solids and liquids. EGD was non-diagnostic and a barium esophagram suggested dysmotility. Initial manometry catheter placement failed due to inability to traverse nasal passage which resolved following nasopharyngeal airway placement. The manometry study identified Jackhammer esophagus (Figure 2A). He was subsequently started on four times daily diltiazem with subjective improvement of symptoms.

Figure 2.

Examples of HRM plots. A) Single swallow on HRM for patient 2 diagnosed with Jackhammer esophagus. Mean distal contractile integral (DCI) = 8585 mmHg-s-cm. B) HRM for patient 7, who was diagnosed with IEM. C) Multiple rapid swallows for patient 7 demonstrating poor peristaltic reserve. D) HRM for patient 8, diagnosed with a mixed motility disorder with features of EGJOO and Jackhammer esophagus. Mean DCI = 8489 mmHg-s-cm; Median integrated relaxation pressure = 65 mmHg; All distal latency > 4.5 sec.

Patient 3 was a 42-year-old female with a past medical history of celiac disease and GERD, referred for symptoms of atypical chest pain, dysphagia to solids, and heartburn on once daily PPI. EGD was normal. Initial manometry catheter placement failed due to inability to traverse nasal passage which resolved following nasopharyngeal airway placement. The manometry study was normal, and her heartburn improved on twice daily PPI.

Patient 4 was a 72-year-old male referred for dysphagia to solids and eructation. EGD showed short segment Barret’s esophagus. Barium esophagram suggested esophageal dysmotility. Initial manometry catheter placement failed due to intractable gagging which resolved following nasopharyngeal airway placement. The manometry study was normal.

Patient 5 was a 56-year-old male with a past medical history of GERD, referred for intermittent dysphagia to solid and liquid food for the past six years. He was diagnosed with esophagogastric junction outlet obstruction (EGJOO) in 2015 according to Chicago Classification v3.0.13 He subsequently underwent pneumatic dilation of the lower esophageal sphincter in 2016, with remarkable improvement in symptoms. Given persistent symptoms, repeat manometry was indicated. Manometry catheter placement failed due to oropharyngeal coiling which resolved following nasopharyngeal airway placement. The manometry study was normal.

Patient 6 was a 57-year-old female with a past medical history of GERD, referred for post prandial bloating with associated abdominal pain and unintentional weight loss. EGD in 2019 showed Barrett’s esophagus, non-erosive gastritis, and biopsy was positive for H. Pylori. Initial manometry catheter placement failed due to inability to traverse nasal passage which resolved following nasopharyngeal airway placement. Manometry demonstrated an elevated median IRP on supine swallows, with normalization of upright median IRP. Her impedance was abnormal. Management included twice daily high dose PPI.

Patient 7 was a 55-year-old male with past medical history of GERD and esophagitis, referred for worsening regurgitation, heartburn, and hiccups while on twice daily PPI and daily H2 blocker. Initial EGD at the onset of symptoms 9 months prior showed only a hiatal hernia. Repeat EGD demonstrated grade D esophagitis and hiatal hernia. Initial manometry catheter placement failed due to inability to traverse nasal passage which resolved following nasopharyngeal airway placement. Manometry showed ineffective esophageal motility with abnormal impedance, and poor peristaltic reserve on multiple rapid swallows (Figure 2B–C). He was referred to surgery for partial fundoplication with hiatal hernia repair.

Patient 8 was a 62-year-old male referred for progressively worsening dysphagia to both solids and liquids over the last 4 years. An EGD two years prior was normal, but a barium esophagram showed transient holdup of the barium tablet at the EGJ. Initial manometry catheter placement failed due to inability to traverse nasal passage which resolved following nasopharyngeal airway placement. Manometry demonstrated a mixed motility disorder with features of EGJOO and Jackhammer esophagus (Figure 2D). He was referred for peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM).

Discussion

We report our experience and success with nasal trumpet-assisted HRiM in eight awake patients. These patients failed the initial HRiM catheter placement due to nasopharyngeal anatomical barriers, excessive gagging, coughing, or oropharyngeal coiling that resolved with the utilization of a nasal trumpet. Placement of the nasal trumpet was well tolerated in all patients without complication. In each patient, diagnoses of normal or esophageal dysmotility were achieved using Chicago Classification version 4.0.14 These diagnoses led to appropriate medical therapy in two patients, procedural intervention in another, and confirmed that absence of dysmotility and need for fundoplication in another. It ruled out esophageal dysmotility in four patients, although one of which had abnormal impedance. This method demonstrates efficacy of alternative methods that can be utilized in a motility lab setting to overcome nasopharyngeal barriers to manometry catheter placement.

Nasal trumpet-assisted HRiM is an inexpensive and widely available tool that can be used to salvage HRiM procedures and reduce procedure failure rates in motility labs. Alternatives to nasal trumpet-assisted HRiM include monitored anesthesia care (MAC)- and EGD-assisted HRiM, which have the limitation of needing repeat scheduling and sedation. One should also consider sedation effects on manometry metrics. EGD- assisted HRiM under sedation continue to be valid options for manometry catheter coiling within the esophagus or when esophageal anatomy is unfavorable for traditional placement (i.e. sigmoid esophagus, epiphrenic hernia, large hiatal hernia, hypertonic LES).5 EndoFLIP can be used as an alternative in institutions where manometry is unavailable. However, it is limited in the assessment of esophageal physiology beyond supportive evidence for obstructive and spastic motility disorders. 9,10

Our study is limited by the use of a single manufacturer, Diversatek, for manometry catheters at each motility lab. Because our study did not include other manufacturer’s products for comparison, it would be important for other motility labs to pre-measure the appropriate nasal trumpet luminal diameter to accommodate their respective catheter sizes and use the smallest diameter possible to minimize patient discomfort. The nasal trumpet can effectively overcome nasopharyngeal barriers to manometry catheter insertion, including narrow nasal passages, coughing, gagging, and oropharyngeal looping. However, nasal trumpets are not useful when catheters loop within the esophagus or unable to traverse the LES. Other limitations include small sample size, retrospective review, and lack of a control group.

In conclusion, nasal trumpet has been shown in our case series to be a well-tolerated and inexpensive tool to salvage HRiM procedures that failed due to nasopharyngeal barriers to catheter placement. This adaptation of the nasopharyngeal airway device requires minimal training to deploy and can be performed in the motility lab when necessary to improve patient tolerance and reduce procedural failure rates.

References

- 1.Kahrilas PJ, Clouse RE, Hogan WJ. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the clinical use of esophageal manometry. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(6):1865–1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pandolfino JE, Fox MR, Bredenoord AJ, Kahrilas PJ. High-resolution manometry in clinical practice: utilizing pressure topography to classify oesophageal motility abnormalities. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21(8):796–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ, American Gastroenterological A. AGA technical review on the clinical use of esophageal manometry. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(1):209–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roman S, Kahrilas PJ, Boris L, Bidari K, Luger D, Pandolfino JE. High-resolution manometry studies are frequently imperfect but usually still interpretable. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(12):1050–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christian KE, Morris JD, Xie G. Endoscopy- and Monitored Anesthesia Care-Assisted High-Resolution Impedance Manometry Improves Clinical Management. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2018;2018:9720243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tariq H, Makker J, Chime C, Kamal MU, Rafeeq A, Patel H. Revisiting the Reliability of the Endoscopy and Sedation-Assisted High-Resolution Esophageal Motility Assessment. Gastroenterology Res. 2019;12(3):157–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Su H, Carlson DA, Donnan E, et al. Performing High-resolution Impedance Manometry After Endoscopy With Conscious Sedation Has Negligible Effects on Esophageal Motility Results. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;26(3):352–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwo PY, Cameron AJ, Phillips SF. Endoscopic esophageal manometry. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(11):1985–1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brun R, Staller K, Viner S, Kuo B. Endoscopically assisted water perfusion esophageal manometry with minimal sedation: technique, indications, and implication on the clinical management. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45(9):759–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cameron AJ, Malcolm A, Prather CM, Phillips SF. Videoendoscopic diagnosis of esophageal motility disorders. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49(1):62–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson DA. Functional lumen imaging probe: The FLIP side of esophageal disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016;32(4):310–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlson DA, Kahrilas PJ, Lin Z, et al. Evaluation of Esophageal Motility Utilizing the Functional Lumen Imaging Probe. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(12):1726–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al. The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(2):160–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yadlapati R, Kahrilas PJ, Fox MR, et al. Esophageal motility disorders on high-resolution manometry: Chicago classification version 4.0((c)). Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(1):e14058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]