Abstract

Working a shift work schedule has been hypothesized to have negative effects on health. One such described consequence is altered immune response and increased risk of infections. Former reviews have concluded that more knowledge is needed to determine how shift work affects the immune system. Since the last review focusing on this subject was published in 2016, new insight has emerged. We performed a search of the topic in PubMed, Scopus and Embase, identifying papers published after 2016, finding a total of 13 new studies. The articles identified showed inconsistent effect on immune cells, cytokines, circadian rhythms, self-reported infections, and vaccine response as a result of working a shift schedule. Current evidence suggests working shifts influence the immune system, however the clinical relevance and the mechanism behind this potential association remains elusive. Further studies need to include longitudinal design and objective measures of shift work and immune response.

Keywords: shift work schedule, immune system, infections

Introduction

Shift work is believed to have a harmful effect on health, a belief supported by research findings. 1 Current evidence suggest shift work is associated with coronary heart disease, 2 stroke, 3 type two diabetes 4 and sleep disturbances 5 among other health related issues.

Working shifts is usually defined as having a working schedule outside the regular working hours from 07.00 to18.00 o'clock, 6 but shift work schedule can vary vastly, being fixed, rotating, split or irregular. Duration of the working hours in each shift duty is also differing between workplaces and occupations, making comparisons between different study groups somewhat challenging. Working shifts negatively affects sleep quality, 7 and both working shifts and sleep disturbances is associated with detriments to health. 8 However, deciding upon the causal relationship between shift work, sleep disturbances and medical and psychological health issues is complicated and not completely mapped out. 9 The potential of healthy worker effect is a risk when conduction research on this topic, as it is plausible that the working population is overall healthier than people not working. 10 It is known that shift work can cause changes in sleep pattern and alter circadian rhythm, 11 12 13 and it has also been suggested that sleep disturbances is a mediator in the association between shift work and some mental 14 and physical health issues. 3

The effect of sleep deprivation and altered sleeping pattern on the immune system is still not fully understood but current evidence point towards an association. 15 Research up until 2016 suggest shift work likely modify immune functions, both through acute and chronical sleep deprivation. 16 However, mechanisms and causal pathways remain elusive as studies investigating cytokines, cell counts, and self-reported infectious illness show conflicting evidence. The aim of this review is to summarize the new knowledge that has emerged since Almeida et al. (2016) published their narrative review, where they compiled the at the time knowledge of the effects of shift work on the immune system. 16

Material and Methods

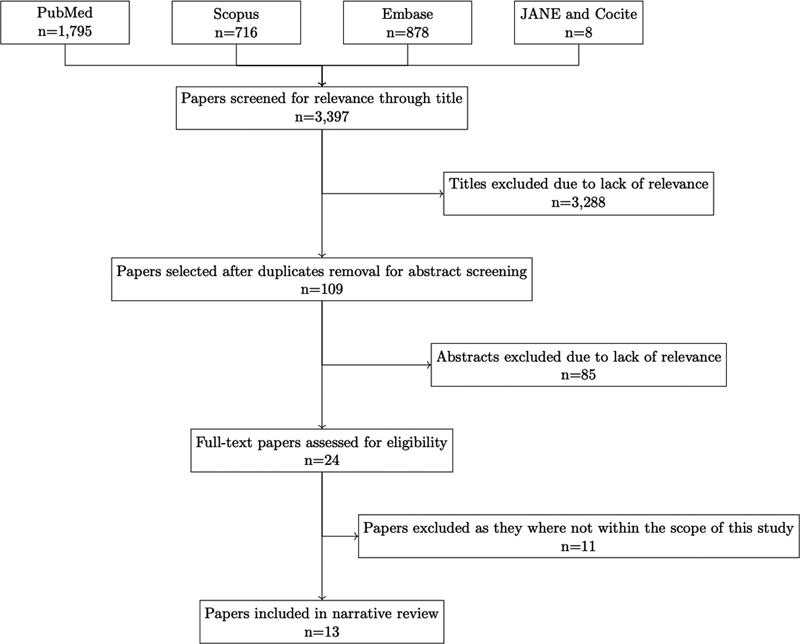

This literary review was constructed based on recommendations on how to write a narrative review from Ferrari (2015), which recommends presenting an intertwined result and discussion section. 17 The search for original articles was done in PubMed, Scopus and Embase, aided by the tools Jane 18 and CoCites 19 to find relevant literature. “Shiftwork”, Shift work”, “Sleep Initiation and Maintenance disorders” were the search terms used for construct shift work combined with OR. “Immune system” and “immune functions” were the terms used for constructing the immune system, combined with OR. The two constructs were thereafter combined with AND. The search was conducted in January 2022 and only original articles published between 2016 and January 2022, available in English in full text, were included ( Figure 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of included studies.

Results and Discussion

Shiftwork and the Immune System

Cells of the innate and adaptive immune systems are known to respond to circadian rhythm, 20 21 and changes in rhythm could potentially be caused by alterations in sleeping pattern as seen with shift work. Working shifts has previously been reported to influence cells involved in the immune response, 22 but more research has been published the last few years exploring the association further. Our current evidence suggests an effect of shift work on cells involved in the immune system but provides somewhat varying results and give little knowledge of clinical relevance (see Table 1 ).

Table 1. Papers investigating the effect of shift on immune cell counts.

| Paper | Study design and population | Main findings | Strengths (+) and weaknesses (-) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zeng et al. 2020 23 | RCT – 12 weeks of light-dark reverse every 4 days in order to disrupt circadian rhythm 6 male mice |

Slight ↓ of NK-cells in lungs and spleen by increased apoptosis and inhibited proliferation. | + Well controlled environment - Small sample size |

| Hanprathet et al. 2019 30 | Retrospective cohort study – 11 years 6,737 male and female workers (a humanitarian organization and a university) |

↑ levels of leukocytes | + Long follow up period + Longitudinal + Large sample size - No baseline data prior to working shifts |

| Wirth et al. 2017 25 | Cross-sectional cohort 464 male and female police officers |

↑ levels of leukocytes, lymphocytes and monocytes | + Accurate information to classify shiftwork + Wide range of covariates to adjust for potential confounders - Generalizability (mostly white males in this study) - Only one blood sampling - Potential healthy worker effect |

| Loef et al. 2019 26 | Cross-sectional cohort 311 male and female hospital workers |

↑ levels of T-cells, lymphocytes and monocytes | - Small sample size - Only one blood sampling |

| Buss et al. 2018 27 | Cross-sectional cohort 8,446 male and female workers |

No difference in mean total leukocyte counts or any cell subsets. | + Large sample size - Self-reported shift work status - No information on time of day for blood sampling |

One cell having recently been investigated is the natural killer (NK) cell, an important cell in the innate immune system, regulating leukocytes by releasing cytokines. When exposing mice to chronic shift-lag, Zeng et al. (2020) found that mice NK-cells displayed disrupted expression of circadian genes, and the proportion and number of NK-cells in the lungs and spleen was slightly decreased compared to mice without disrupted circadian alignment. 23 The authors suggest these changes may impair NK-cell mediated immunosurveillance. These findings correlate with results in a previous study demonstrating that degree of fatigue, due to shift work, had a negative effect on NK-cell function. 24

Evidence from larger epidemiological data shows somewhat conflicting information on the effect of shift work on leukocyte counts. In a study by Wirth et al. (2017) investigating this association in police officers found that leukocyte counts were elevated for those working night shifts on a long-term basis over a 7-day period compared to day shift workers. Night shift work was also associated with higher levels of lymphocytes and monocytes. 25 Similarly, Loef et al. (2019) compared monocyte, granulocyte, lymphocyte, and T cell subsets in hospital employees working either night- or non-shift. Compared with non-shift workers night shift workers having worked night shift the past three days had elevated levels of monocytes and elevated levels of T cells and CD8 T cells. 26 In contrast, Buss et al. (2018) found no evidence of an association between shift work and leukocyte counts. 27 However, the authors point out the possibility of misclassification bias in this study, as shift work status was self-reported.

Epidemiological evidence of increased leukocyte counts in shift workers mostly comes from cross sectional data, as seen in the papers by Buss et al. (2018), Wirth et al (2017). and others. 25 27 28 29 To make up for the lack of ability to establish a cause-effect relationship between shift work and increasing numbers of leukocytes in previous cross-sectional studies, Hanprathet et al. (2019) aimed to use a longitudinal design to evaluate leukocyte counts over a time period. 30 They found that current shift work was associated with an increased number of leukocytes compared to non-shift workers, but leucocyte counts were within normal ranges in both groups. However, an increase in leucocyte count can increase risk of chronic disease and other health outcomes also within normal ranges. 31

Cytokines

Several studies have focused on identifying changes in cytokine levels as a result of shift work (see Table 2 ). In a study from 2016 Cuesta et al. found partially shifted cytokine release in rodents exposed to a night shift schedule, suggesting shift work alters the circadian rhythm of immune function. 32 In a more recent experimental study, simulating three days of night- or dayshift for 14 healthy women and men, Liu et al. (2017) found lower mean circulating TNF-α in participants following a night shift schedule. There were however no significant differences in IL-β, IL-8 or IL-10. Circulating IL-6 was also elevated with increasing time awake in both groups. This meant it was also shifted accordingly to the circadian misalignment that the group exposed to a night shift schedule experienced. 33

Table 2. Papers investigating shift works effect on cytokine levels.

| Paper | Study design and population | Main findings | Strengths (+) and weaknesses (-) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al. 2017 33 | RCT 14 healthy men and women |

● Night shift schedule resulted in ↓ mean TNF-α levels between groups, but no significant differences in IL-β, IL-8 or IL-10. ● ↑ IL-6 levels with increasing hours awake. |

+ Well controlled exposure environment + Multiple blood samplings at controlled time points - Small sample size - Short observational period |

| Bjorvatn et al. 2020 35 | Study 1: Cross-sectional 1,390 nurses Study 2: Longitudinal 55 nurses |

● Study 1: neither work schedule, number of night shifts, sleep duration, poor sleep quality nor shift work disorder was systematically associated with IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-13; MCP-1, INF- γ or TNF-α. ● Study 2: Elevated IL-1β both after a night of work and a dayshift, compared to after a night of sleep. Elevated TNF-α after a dayshift compared to a night of sleep. Reduction in MCP-1 both after a night of work and a dayshift, compared to after a night of sleep. |

+ Large sample size (study 1) - Based on dried blood spot method (study 1) - Only a subset of 55 individuals provided fullblood samples (study 2) - Results have large effect sizes |

| Nevels et al. 2021 36 | Cross-sectional cohort 430 police officers |

Maladaptation to working fixed night shifts potentially lead to increased IL-6 and TNF-α | + Accurate information on shift schedule - Residual confounding - Only one blood sampling |

| Aquino-santos et al. 2020 34 | Cross-sectional cohort 25 police officers and 25 civil men |

Chronic alterations in circadian rhythm caused by shift work impaired pulmonary and systemic immune function. | + Accurate information on shift schedule - Small sample size - Only one blood sampling |

Aquina-Santos et al. (2020) compared policemen working shift schedule to a group of civil men working a fixed schedule. Their aim was to determine whether the different working schedules effected the immune function of the lungs, systemic inflammation, and immune response. Policemen working shift had significantly higher breath concentrates of IL-2 and nitric oxide, but not IL-10 and TNF-γ, indicating increased inflammation in the lungs. Serum IL-2 was elevated while serum IL-10 was reduced in policemen compared to civilians. 34 In contrast, Bjorvatn et al (2020) found no systematic changes in multiple interleukins, interferon-γ and TNF-α with variations in nurses work schedule, sleep duration nor sleep quality when sampling blood after a night of sleep. They did however find that levels of IL-1β and TNF-α were elevated when sampling blood after a dayshift, IL-1β was higher after a night shift and MCP-1 was lower after both day- and nightshifts when compared to a night of sleep. Cytokine levels reported in this study were low for all participants. As of this, the authors suggest shift work itself does not have a strong influence on immune function. They rather debate that the changes seen when sampling blood after a work shift indicate an acute effect of having been to work. 35

It is also believed that people adapt differently to shift work with some adapting well and being able to work shift without adverse events, while others experience maladaptation and are more at risk of disease. This is the foundation for the study performed on a group of police officers where they investigated to see whether maladaptation to shift work influenced cytokines, among other biomarkers. They found that workers who were maladapted to shift work had a higher mean level of IL-6 and TNF-α compared to adapted shift workers. However, the authors point out that although their findings are statistically relevant, they question the biological relevancy. They also did not find CRP levels to be elevated to a level associated with increased risk of disease in either of the groups. 36

Circadian Rhythm

It seems that the human blood transcriptome is influenced by circadian rhytms, and that disrupted circadian rhythm caused by night shift work may change immune functions. 37 38 In a study from 2018 Kervezee et al. investigated the effect of a 4-day simulated rotating night shift routine on the human transcriptome, to better understand the molecular alterations that could potentially cause the ill health outcomes associated with shift work ( Table 3 ). Their findings suggest circadian misalignment could result in changes in transcripts related to NK cells 39 and are in line with the results described by Zeng et al. (2020) as previously mentioned. 23 As the NK cells play a critical part in the killing of tumor and virally infected cells, these changes potentially alter the innate immune response.

Table 3. Papers investigating changes in circadian rhythm with focus on immune function in response to shift work.

| Paper | Study design and population | Main findings | Strengths (+) and weaknesses (-) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kervezee et al. 2018 39 | RCT 4 days simulated night shift protocol with a 10-hour delay of their habitual sleep period 8 healthy individuals (7 men and 1 woman). |

Lost temporal coordination of human circadian transcriptome. This effects most notably the natural killer cell-mediated immune response and Jun/AP1 and STAT pathways. | + Well controlled exposure environment + Multiple blood samplings at controlled time points - Small sample size - Short observational period |

| Abo & layton 2021 40 | Mathematical model simulating the circadian clock in rat lungs. Simulated shift work by an 8-hour phase shift. |

Females produced less pro-inflammatory cytokines than males, with variations of the experienced sequelae throughout the day. | - No direct link between cytokines and clock genes and proteins |

In another study by Abo & Layton et al. (2021) they simulated the circadian regulation of the immune system in rats and found evidence of a sexually dimorphic effect of shift work ( Table 3 ). Female rats produced less pro-inflammatory cytokines compared to male, however the extent depended on time of infection. 40 The authors suggest that the circadian disruption they saw evidence of, is mediated by circadian disruption of REV-ERB and CRY, negatively effecting the expression of IL-6 and IL-10. They also hypothesize the elevated levels of IL-6 and TNFα in males compared to females could leave male rats more vulnerable to sepsis. 40

Self-reported Disease

In a large cross-sectional study by Prather et al. (2021) investigated risk of infections with working shifts in 59,261 individuals participating in the National Interview Health Survey (NIHS). They found that participants working rotating shifts were 20% more likely to report having a cold during the past two weeks compared with participants working only dayshifts ( Table 4 ). The authors suggest these differences could be a result of the effect of rotating shift on circadian rhythm. 41 Their findings are in line with previous research results from 2002, reporting elevated risk of common infections with working a shift schedule. 42 However, it is of importance that both these studies are using self-reported outcomes of infectious disease, and not verified infections, opening the possibility of self-report bias.

Table 4. Paper investigating risk of self-reported disease.

| Paper | Study design and population | Main findings | Strengths (+) and weaknesses (-) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prather et al. 2020 41 | Cross-sectional 59,261 men and women. |

Working shifts was associated with a 20% increased risk of reporting to have a head or chest cold during the past two weeks. | + Large sample size - Self-reported symptoms |

Vaccine Response

Sleep deprivation has previously been shown to be associated with reduction in antibody production after vaccination, in two studies from 2012 and 2011. 43 44 Ruiz et al. (2020) wanted to put this assumption to the test, using a more real-life scenario, by investigated the immune response after meningococcal vaccine in 34 healthy shift workers ( Table 5 ). Their findings are in line with the previous findings of Patel et al. (2011) and Lange et al. (2011), suggesting that night shift workers have a weaker humoral response to vaccination, hypothesizing this to be a result of both chronic sleep restriction and circadian misalignment. 45

Table 5. Paper reporting the effect of shift work on vaccine response.

| Paper | Study design and population | Main findings | Strengths (+) and weaknesses (-) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ruiz et al. 45 | RCT 34 healthy male and female shift workers. |

Sufficient sleep time and synchronized rhythm were important for the development of Ag-specific immune response. | + Well controlled exposure environment + Polysomnographic evaluation of sleep - Small sample size |

Conclusion

Current epidemiological evidence suggests working shifts influence the immune system, however the mechanisms involved remain elusive and causal interpretations are still not possible. The clinical relevancy from current findings on relevant biomarkers are questionable and more quality research with access to accurate information on shift work status together with follow-up design with multiple blood samplings and/or verified infectious illness is needed to get a better understanding of the mechanisms and causal pathways involved.

Funding Statement

Funding This work has received no funding.

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Lise Tuset Gustad and Jan Kristian Damås contributed equally to this paper.

References

- 1.Costa G. Shift work and occupational medicine: an overview. Occup Med (Lond) 2003;53(02):83–88. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqg045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang N, Sun Y, Zhang H et al. Long-term night shift work is associated with the risk of atrial fibrillation and coronary heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(40):4180–4188. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown D L, Feskanich D, Sánchez B N, Rexrode K M, Schernhammer E S, Lisabeth L D. Rotating night shift work and the risk of ischemic stroke. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(11):1370–1377. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vetter C, Dashti H S, Lane J M et al. Night Shift Work, Genetic Risk, and Type 2 Diabetes in the UK Biobank. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(04):762–769. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hulsegge G, Loef B, van Kerkhof L W, Roenneberg T, van der Beek A J, Proper K I. Shift work, sleep disturbances and social jetlag in healthcare workers. J Sleep Res. 2019;28(04):e12802. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Redeker N S, Caruso C C, Hashmi S D, Mullington J M, Grandner M, Morgenthaler T I. Workplace Interventions to Promote Sleep Health and an Alert, Healthy Workforce. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(04):649–657. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ROSTERS Study Group . Barger L K, Sullivan J P, Blackwell T et al. Effects on resident work hours, sleep duration, and work experience in a randomized order safety trial evaluating resident-physician schedules (ROSTERS) Sleep. 2019;42(08):zsz110. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaradat R, Lahlouh A, Mustafa M. Sleep quality and health related problems of shift work among resident physicians: a cross-sectional study. Sleep Med. 2020;66:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.11.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grandner M A. Sleep, Health, and Society. Sleep Med Clin. 2020;15(02):319–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2020.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothman K J, Greenland S, Lash T L.Modern Epidemiology3rd ed:Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW)12 Causal Diagrams;2008198–199. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akerstedt T. Shift work and disturbed sleep/wakefulness. Occup Med (Lond) 2003;53(02):89–94. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqg046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sallinen M, Härmä M, Mutanen P, Ranta R, Virkkala J, Müller K. Sleep-wake rhythm in an irregular shift system. J Sleep Res. 2003;12(02):103–112. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2003.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brito R S, Dias C, Afonso Filho A, Salles C. Prevalence of insomnia in shift workers: a systematic review. Sleep Sci. 2021;14(01):47–54. doi: 10.5935/1984-0063.20190150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng W J, Cheng Y. Night shift and rotating shift in association with sleep problems, burnout and minor mental disorder in male and female employees. Occup Environ Med. 2017;74(07):483–488. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2016-103898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Besedovsky L, Lange T, Haack M. The sleep-immune crosstalk in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(03):1325–1380. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Almeida C M, Malheiro A. Sleep, immunity and shift workers: A review. Sleep Sci. 2016;9(03):164–168. doi: 10.1016/j.slsci.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrari R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writing. 2015;24(04):230–235. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schuemie M.JANE 2007 [Available from:https://jane.biosemantics.org/index.php

- 19.Janssens A CJW, Gwinn M, Brockman J E, Powell K, Goodman M. Novel citation-based search method for scientific literature: a validation study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(01):25. doi: 10.1186/s12874-020-0907-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Born J, Lange T, Hansen K, Mölle M, Fehm H L. Effects of sleep and circadian rhythm on human circulating immune cells. J Immunol. 1997;158(09):4454–4464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lange T, Dimitrov S, Born J. Effects of sleep and circadian rhythm on the human immune system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1193:48–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakano Y, Miura T, Hara Iet al. The effect of shift work on cellular immune function J Hum Ergol (Tokyo) 198211(Suppl):131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng X, Liang C, Yao J. Chronic shift-lag promotes NK cell ageing and impairs immunosurveillance in mice by decreasing the expression of CD122. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(24):14583–14595. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.16088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagai M, Morikawa Y, Kitaoka K et al. Effects of fatigue on immune function in nurses performing shift work. J Occup Health. 2011;53(05):312–319. doi: 10.1539/joh.10-0072-oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wirth M D, Andrew M E, Burchfiel C M et al. Association of shiftwork and immune cells among police officers from the Buffalo Cardio-Metabolic Occupational Police Stress study. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34(06):721–731. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2017.1316732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loef B, Nanlohy N M, Jacobi R HJ et al. Immunological effects of shift work in healthcare workers. Sci Rep. 2019;9(01):18220. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54816-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buss M R, Wirth M D, Burch J B. Association of shiftwork and leukocytes among national health and nutrition examination survey respondents. Chronobiol Int. 2018;35(03):435–439. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2017.1408639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puttonen S, Viitasalo K, Härmä M. Effect of shiftwork on systemic markers of inflammation. Chronobiol Int. 2011;28(06):528–535. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2011.580869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim S W, Jang E C, Kwon S C et al. Night shift work and inflammatory markers in male workers aged 20-39 in a display manufacturing company. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2016;28:48. doi: 10.1186/s40557-016-0135-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanprathet N, Lertmaharit S, Lohsoonthorn V, Rattananupong T, Ammaranond P, Jiamjarasrangsi W. Shift Work and Leukocyte Count Changes among Workers in Bangkok. Ann Work Expo Health. 2019;63(06):689–700. doi: 10.1093/annweh/wxz039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chmielewski P P, Strzelec B. Elevated leukocyte count as a harbinger of systemic inflammation, disease progression, and poor prognosis: a review. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 2018;77(02):171–178. doi: 10.5603/FM.a2017.0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cuesta M, Boudreau P, Dubeau-Laramée G, Cermakian N, Boivin D B. Simulated Night Shift Disrupts Circadian Rhythms of Immune Functions in Humans. J Immunol. 2016;196(06):2466–2475. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu P Y, Irwin M R, Krueger J M, Gaddameedhi S, Van Dongen H PA. Night shift schedule alters endogenous regulation of circulating cytokines. Neurobiol Sleep Circadian Rhythms. 2021;10:100063. doi: 10.1016/j.nbscr.2021.100063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aquino-Santos H C, Tavares-Vasconcelos J S, Brandão-Rangel M AR et al. Chronic alteration of circadian rhythm is related to impaired lung function and immune response. Int J Clin Pract. 2020;74(10):e13590. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bjorvatn B, Axelsson J, Pallesen S et al. The Association Between Shift Work and Immunological Biomarkers in Nurses. Front Public Health. 2020;8:415. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nevels T L, Burch J B, Wirth M D et al. Shift Work Adaptation Among Police Officers: The BCOPS Study. Chronobiol Int. 2021;38(06):907–923. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2021.1895824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Archer S N, Laing E E, Möller-Levet C S et al. Mistimed sleep disrupts circadian regulation of the human transcriptome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(06):E682–E691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316335111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Möller-Levet C S, Archer S N, Bucca G et al. Effects of insufficient sleep on circadian rhythmicity and expression amplitude of the human blood transcriptome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(12):E1132–E1141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217154110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kervezee L, Cuesta M, Cermakian N, Boivin D B. Simulated night shift work induces circadian misalignment of the human peripheral blood mononuclear cell transcriptome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(21):5540–5545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720719115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abo S MC, Layton A T. Modeling the circadian regulation of the immune system: Sexually dimorphic effects of shift work. PLOS Comput Biol. 2021;17(03):e1008514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prather A A, Carroll J E. Associations between sleep duration, shift work, and infectious illness in the United States: Data from the National Health Interview Survey. Sleep Health. 2021;7(05):638–643. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2021.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mohren D C, Jansen N W, Kant I J, Galama J, van den Brandt P A, Swaen G M. Prevalence of common infections among employees in different work schedules. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44(11):1003–1011. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200211000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel S R, Malhotra A, Gao X, Hu F B, Neuman M I, Fawzi W W. A prospective study of sleep duration and pneumonia risk in women. Sleep. 2012;35(01):97–101. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lange T, Dimitrov S, Bollinger T, Diekelmann S, Born J. Sleep after vaccination boosts immunological memory. J Immunol. 2011;187(01):283–290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruiz F S, Rosa D S, Zimberg I Z et al. Night shift work and immune response to the meningococcal conjugate vaccine in healthy workers: a proof of concept study. Sleep Med. 2020;75:263–275. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]