Abstract

Objective To analyze the impact of sleep quality/duration on cardiac autonomic modulation on physically active adolescents with obesity.

Materials and Methods The present cross-sectional study included 1,150 boys with a mean age of 16.6 ± 1.2 years. The assessment of cardiac functions included the frequency domain of heart rate variability (HRV; low frequency – LF; high frequency – HF; and the ratio between these bands –LF/HF –, defined as the sympathovagal balance), and each parameter was categorized as low / high . Physical activity levels and sleep quality/duration were obtained by questionnaires. Abdominal obesity was assessed and defined as waist circumference > 80 th percentile.

Results Poor sleep quality resulted in lower HF (odds ratio [OR]: 1.8; 95% confidence interval [95%CI]: 1.01–3.21]) regardless of physical activity and abdominal obesity. Moreover, the study found no association between sleep duration and HRV parameters in adolescents.

Conclusion Sleep quality, not sleep duration, reduces parasympathetic cardiac modulation apart from other factors such as physical activity and abdominal obesity in adolescents.

Keywords: sleep, autonomic nervous system, adolescent, exercise, cardiovascular system

Introduction

During development, adolescents may experience sleep-related problems: delayed sleep onset, insomnia, and insufficient sleep. Complications of sleep-related illnesses have steadily developed into an increasing issue worldwide. 1 2 Altered sleep-wake cycle impairs concentration, promotes behavior and emotional instability, and is associated with poor prognostic of cardiovascular health problems: hypertension and disordered autonomic nervous function. 3 4 5

Cardiac autonomic modulation regulated by the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems can indicate cardiovascular dysfunction. 6 7 8 In adolescents, a decrease in parasympathetic and an increase in sympathetic modulation is associated with obesity, 9 10 high blood pressure, 11 and low physical activity levels. 12

Based on the aforementioned findings, a correlation between cardiovascular outcomes and sleep quality/duration 3 13 14 suggests that adolescents with shorter or poor sleep quality experience poor cardiac autonomic modulation. 4 Furthermore, sleep quality and variability in sleep duration increased sympathetic modulation and decreased parasympathetic modulation. 4 5

Physical activity and obesity (especially abdominal obesity) are related to cardiovascular risk in adolescents. 15 16 For example, a recent study observed a disrupted balance in autonomic nervous system regulation during all sleep stages only in obese adolescents. 17 Another study recognized that physical activity, not the sleep pattern, relates to sympathetic and parasympathetic autonomic modulation in adolescents. 16 However, as previous studies have analyzed the relationship between cardiac autonomic modulation and sleep stages, whether the overall sleep quality and sleep duration relate to cardiac autonomic modulation in obese adolescents remains unclear. Furthermore, whether physical activity modulates this relationship is still unknown.

Thus, the present study aimed to verify the association between sleep quality and duration and cardiac autonomic modulation in adolescents and to verify if this association occurs independently of obesity and physical activity levels.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Subjects

The present cross-sectional study was approved by the institutional Ethics in Research Committee, and it followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines, 18 a the Brazilian human research ethics evaluation system, composed by the Research Ethics Committees (Comitês de Ética em Pesquisa, CEPs, in Portuguese) and the National Research Ethics Commission (Comissão Nacional de Ética em Pesquisa, CONEP,in Portuguese) called the CEP-CONEP System, and the guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, revised in 1983.

The focus demographic group comprises male adolescents aged between 14 and 19 years, who are students in the public school system of the state of Pernambuco – northeastern Brazil. The adolescents could not have diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, neurological or mental disabilities. Adolescents who used alcohol, tobacco, illicit drugs, or performed moderate to vigorous physical activity within the last 24 hours before evaluation were not included in the study. Procedures were according to previous studies. 8 9 11 19 20 21

Data Collection

Data collection began in May 2011 and ended in October 2011 while the students, adolescents, attended class throughout the day: morning, afternoon, and evening. Cardiac autonomic function parameters (outcomes), sleep quality/duration (independent variable), abdominal obesity, and physical activity (covariates) comprised the data collected using the Global School-based Student Health Survey, as proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) for similar epidemiologic studies in children and adolescents, which is available at www.who.int/chp/gshs/en . 22

Cardiac Autonomic Modulation

The cardiac autonomic modulation was evaluated through the heart rate variability (HRV). After 30 minutes of rest, HRV was registered for 10 minutes using a heart rate monitor, (POLAR, RS 800CX; Polar Electro Oy, Kempele, Finland), without breathing control. All analyses were performed with Kubios HRV software (Biosignal Analysis and Medical Imaging Group, Joensuu, Finland) by a single evaluator blinded to the other study variables, following the recommendations of the Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. 23 The intraclass correlation coefficient of this evaluator was 0.99. 24

The frequency-domain parameters utilized spectral analysis of HRV following the recommendations of the Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. 23 Stationary periods of the tachogram, with at least 5 minutes, were broken down into bands of low (LF) and high (HF) frequencies using the autoregressive method, and the order of the model was chosen according to Akaike's criterion. The power of each spectral component was normalized by dividing the power of each spectrum band by the total variance and subtracting the value of the very low frequency band (< 0.04 Hz), and then multiplying the result by 100.

The spectral components used the autoregressive methods and the order of the model based on Akaike's criterion. The power of each spectral component converts normally by dividing the power of each spectrum band by the total variance and then subtracting the value of the very-low-frequency band (< 0.04 Hz), and then multiplying by 100. Interpretation of the results includes LF and the HF components of the HRV as representatives of predominance of the sympathetic and vagal modulations of the heart respectively. The ratio between these bands (LF/HF) was defined as the cardiac sympathovagal balance. Low HF values (≤ 53.8 n.u.), high LF values (≥ 46.1 n.u.), and high LF/HF (≥ 0.85) were indicators of poor cardiac autonomic modulation. 8

Sleep Variables

Sleep quality assessment required the participants to answer the question, “how do you evaluate the quality of your sleep?” Thus, participants choose one of two options: poor (bad or regular) or good (very good or great). According to the questionnaire, the sleep duration was assessed by the number of hours of sleep per night as follow: “On weekdays and weekends, on average, how many hours do you sleep a day?” Adolescents choose between the options: 4 or less hours, 5 hours, 6 hours, 7 hours, 8 hours, 9 hours, or 10 or more hours.

Abdominal Obesity

Waist circumference (WC) was measured using an inextensible tape, and it was determined as the minimum circumference between the iliac crest and rib cage. Abdominal obesity was assessed and defined as WC > 80 th percentile based on other adolescents. 25

Physical Activity Level

A question on the questionnaire evaluated physical activity level, “During the past 7 days, on how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60 minutes per day?” The low physical activity category consisted of < 5 days per week of moderate to vigorous physical activity. 22 26 Additionally, on the reproducibility indicators of the physical activity levels, the kappa coefficient and the Spearman rank correlation coefficient between 0.60 and 0.82, respectively.

Statistical Analyses

The IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) software, version 20.0, was used in the statistical analysis of the HRV data. The data were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) values, and the categorical variables were summarized as frequencies, whereas the binary logistic regression analyses, albeit done crudely, analyzed the association between the HRV parameters and sleep quality. For analysis, sleep duration was categorized into < 6 hours a day, 7 to 8 hours a day, or 9 hours per day. The analyses adjusted for age, the period of the day (either morning, afternoon, or evening), abdominal obesity (nonobese and obese), and physical activity (low and high physical activity.) The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) received information per parameter. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test evaluated the goodness of fit and the significance level for all analyses was set at p < 0.05.

Results

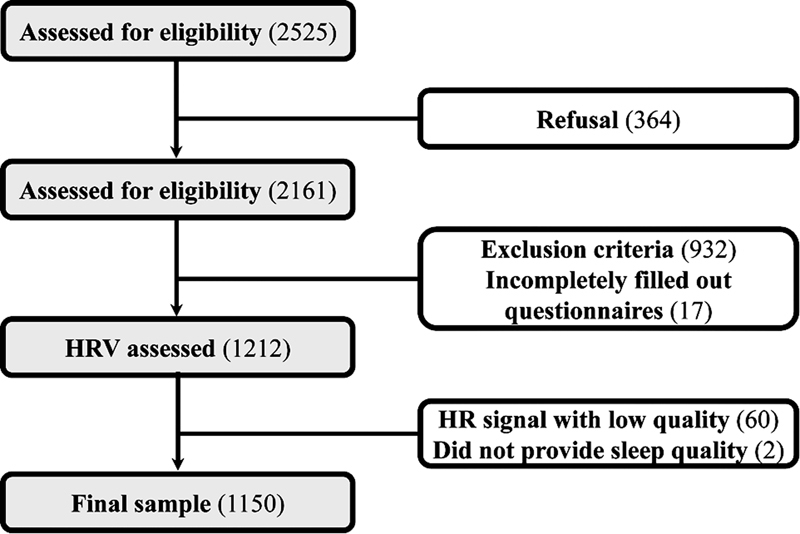

A total of 1,212 boys were enrolled in the study, of whom 60 could no longer participate due to low signal quality (stationary periods of the tachogram length < 5 minutes), and another two for not answering the questions within the allowed time. Therefore, the final analysis included data from 1,150 boys ( Figure 1 ). Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the subjects. Regarding the health outcomes, only 21.7% reported poor sleep quality and 15.4% were classified as obese. On the other hand, most of them (64.4%) reported low levels of physical activity.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the present study.

Table 1. General characteristics of the adolescents ( n = 1,150) in the present study.

| Variable | Values |

|---|---|

| Age (in years): mean ± standard deviation | 16.6 ± 1.2 |

| Weight (in kg): mean ± standard deviation | 63.7 ± 12.6 |

| Height (in cm): mean ± standard deviation | 171.6 ± 7.1 |

| Waist circumference (in cm): mean ± standard deviation | 76.6 ± 9.4 |

| Ethnicity: non-white (%) | 72.0 |

| Class shift: evening (%) | 26.2 |

| Place of residence: urban (%) | 79.2 |

| Abdominal obesity (%) | 15.4 |

| Low physical activity level (%) | 64.4 |

| Poor sleep quality (%) | 21.7 |

| Hours slept on weekdays (%) | |

| ≤ 6 per day | 27.0 |

| 7 to 8 per day | 46.7 |

| ≥ 9 per day | 26.3 |

| Hours slept on weekends (%) | |

| ≤ 6 per day | 20.5 |

| 7 to 8 per day | 35.3 |

| ≥ 9 per day | 44.2 |

The association between HRV parameters and sleep quality in boys is presented in Table 2 . Poor sleep quality leads to lower HF, regardless of age, time of the day, abdominal obesity, and physical activity levels. No significant association was observed between LF and LF/HF.

Table 2. Crude and adjusted binary logistic regression analysis of the association between heart rate variability parameters and sleep quality in boys.

| Low HF | High LF | High LF/HF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted | Crude | Adjusted | Crude | Adjusted | |

| OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | |

| Good sleep quality | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Poor sleep quality | 1.85 (1.05–3.24) | 1.80 (1.02–3.17) | 0.86 (0.65–1.15) | 0.85 (0.64–1.14) | 0.84 (0.63–1.12) | 1.15 (0.62–1.10) |

Abbreviations: 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; HF, high-frequency component in normalized units; LF, low-frequency component in normalized units; OR, odds ratio.

Notes: Adjusted for age, time of day, physical activity level, and abdominal obesity. Hosmer-Lemeshow test for HF: χ 2 = 7.26; p = 0.508; Hosmer-Lemeshow test for LF: χ 2 = 12.00; p = 0.151; Hosmer-Lemeshow test for LF/HF: χ 2 = 10.65; p = 0.222.

Table 3 shows the associations between the number of sleeping hours on weekends and weekdays and HRV parameters in boys. There was no significant association between HRV and sleep duration ( p > 0.05 for all).

Table 3. Association between number of sleeping hours and heart rate variability parameters in boys.

| Low HF | High LF | High LF/HF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted | Crude | Adjusted | Crude | Adjusted | |

| OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | |

| Hours slept on weekdays | ||||||

| ≤ 6per day | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 to 8 per day | 0.99 (0.62–1.58) | 0.98 (0.61–1.57) | 1.25 (0.94–1.66) | 1.21 (0.90–1.62) | 1.26 (0.95–1.69) | 1.22 (0.91–1.64) |

| ≥ 9per day | 1.13 (0.66–1.95) | 1.15 (0.66–2.01) | 1.07 (0.77–1.47) | 0.99 (0.71–1.38) | 1.05 (0.76–1.45) | 0.98 (0.70–1.36) |

| Hours slept on weekends | ||||||

| ≤ 6per day | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 to 8 per day | 1.20 (0.73–2.01) | 1.08 (0.64–1.81) | 1.01 (0.73–1.40) | 0.94 (0.67–1.32) | 1.00 (0.72–1.39) | 0.94 (0.67–1.31) |

| ≥ 9per day | 1.46 (0.88–2.42) | 1.38 (0.83–2.32) | 1.21 (0.88–1.66) | 1.19 (0.86–1.64) | 1.17 (0.85–1.61) | 1.15 (0.83–1.60) |

Abbreviations: 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; HF, high-frequency component in normalized units; LF, low-frequency component in normalized units; OR, odds ratio.

Notes: Adjusted for age, time of day, abdominal obesity, and physical activity level.

Hours slept on weekdays: Low HF– Hosmer-Lemeshow test: χ 2 = 8.63; p = 0.375; High LF – Hosmer-Lemeshow test: χ 2 = 13.30; p = 0.102; High LF/HF – Hosmer-Lemeshow test: χ 2 = 12.94; p = 0.114.

Hours slept on weekends: Low HF – Hosmer-Lemeshow test: χ 2 = 16.10; p = 0.041; High LF – Hosmer-Lemeshow test: χ 2 = 15.00; p = 0.054; High LF/HF – Hosmer-Lemeshow test: χ 2 = 7.87; p = 0.446.

Discussion

Our findings show that the study found that poor sleep quality relates to lower parasympathetic cardiac modulation, independently of abdominal obesity and physical activity levels. On the other hand, sleep duration did not impact the modulation of cardiac functions in adolescents.

Typically, adolescents receive less than the recommended number of hours per night of sleep (eight versus nine hours, respectively). 27 About 20% of them have significant sleeping problems. 27 However, in the present study, we did not observe a significant association between cardiac autonomic modulation and self-reported sleep duration. In children and adolescents, the study perceives an inconsistent relationship between sleep duration and cardiac autonomic dysfunction. 4 5 For example, Michels et al. 5 found no significant association between objectively measured sleep duration and cardiac autonomic modulation in 334 children aged between 5 and 11 years old, whereas Rodríguez-Colón et al. 4 observed that higher habitual sleep duration associated with poor cardiac autonomic modulation in 421 adolescents (mean 16.7 ± 2.3 years old).

Now, for the present study, other factors may affect the result. For example, people can have a difference in opinion when answering how they measure their sleep quality. Differently from the present study, poor sleep quality assessed through the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) ranged between 53 28 and 82% 29 in Brazilian adolescents; however, when analyzing specifically the PSQI domains, 12% of adolescents had poor sleep quality, 28 which is consistent with results of the present study even with a different questionnaire.

Participants may self-report sleep duration as an over or underestimation. Secondly, only ∼ 27 of the adolescents slept below the recommended amount: only extreme sleep deprivation would affect autonomic cardiac modulation. Thirdly, the amount of sleep required for homeostatic sleep regulation may vary between individuals, of course respecting biological individuality: Short sleepers, people who need < 6 hours of daily sleep, and long sleepers, people that need ≥ 9 hours of sleep per day to meet their needs. 30

Insufficient sleep at an adolescent age associates with increased cardiovascular risk. 3 Michels et al., 5 in a study on the relationship between low sleep quality and cardiac autonomic modulation, observed that poor sleep quality could lead to autonomic imbalance, higher sympathetic modulation, and lower parasympathetic modulation in children with no obesity; however, the results may differ from our study, as we used abdominal obesity as an adjustment. In this sense, adiposity in the abdominal region has previously been associated with worse cardiac autonomic modulation 8 and could influence the relationship between the number of hours of sleep per night and HRV.

Divergence results between sleep duration and sleep quality indicate that self-perceived sleep quality influences cardiac autonomic control over the time spent sleeping. Supporting this claim, a study with 300 children (aged between 5 and 11 years), observed that low sleep quality, dismissing the low sleep duration reported by the parent, induced sympathetic dominance. 5 Additionally, another study that analyzed 223 healthy white-collar male workers found a similar response to sympathetic dominance. 31 Poor sleep quality can also directly impact stress levels, affecting norepinephrine and epinephrine, 32 33 34 and cardiac autonomic modulation. 35 Sleep deprivation also increases proinflammatory status, 36 37 38 which leads to reduced autonomic cardiac modulation to the heart. 39 40

Overall, the association between poor sleep quality and reduction in effective cardiac autonomic modulation obtained in the present study clinically reveals the importance of cardiovascular health. 9 11 Regardless of obesity and physical activity, people should develop sleep strategies to improve their quality of sleep understanding that cardiac autonomic modulation within adolescents could lead to better knowledge and clinical care for at-risk cardiovascular adult patients. 14

As limitations of the present study, the cross-sectional design and the correlative nature of the data preclude us from establishing a causal relationship between HRV and sleep variables. Although the ages of the participants were tightly controlled, we could not determine the Tanner stage of the participants. Longitudinal evaluations in multiethnic adolescent populations and both sexes are needed to make these conclusions. The use of self-reported measures for physical activity and sleep variables are important limitations that need to be considered. Finally, although the sleep deficit has been shown to be associated to sleep patterns, 41 it was not assessed in the present study. However, as strong aspects, to our knowledge, population-based study to verify the influence of lifestyle parameters such as physical activity level and obesity in the association between sleep and cardiac autonomic modulation in adolescents. Secondly, HRV analyzed by a single researcher, as part of the double-blind experiment, used a low-cost instrument widely accepted in the literature. Third, we emphasize the large sample number used in the present study, comprising several cities in a state in the northeast region of Brazil.

In conclusion, regardless of the physical activity level and abdominal obesity, sleep quality, but not sleep duration, was associated with lower parasympathetic autonomic modulation in adolescent boys.

Funding Statement

Source of Funding The present work was supported by a grant (grant #481067/2010-8) from the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, in the Portuguese acronym). Additional support was provided by the following agencies: the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES, in the Portuguese acronym).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

- 1.Dahl R E, Lewin D S.Pathways to adolescent health sleep regulation and behavior J Adolesc Health 200231(6, Suppl)175–184. 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00506-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts R E, Roberts C R, Duong H T. Sleepless in adolescence: prospective data on sleep deprivation, health and functioning. J Adolesc. 2009;32(05):1045–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narang I, Manlhiot C, Davies-Shaw J et al. Sleep disturbance and cardiovascular risk in adolescents. CMAJ. 2012;184(17):E913–E920. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodríguez-Colón S M, He F, Bixler E O et al. Sleep variability and cardiac autonomic modulation in adolescents - Penn State Child Cohort (PSCC) study. Sleep Med. 2015;16(01):67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michels N, Clays E, De Buyzere M, Vanaelst B, De Henauw S, Sioen I. Children's sleep and autonomic function: low sleep quality has an impact on heart rate variability. Sleep. 2013;36(12):1939–1946. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malpas S C. Sympathetic nervous system overactivity and its role in the development of cardiovascular disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(02):513–557. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grassi G, Mark A, Esler M. The sympathetic nervous system alterations in human hypertension. Circ Res. 2015;116(06):976–990. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farah B Q, Christofaro D GD, Cavalcante B R et al. Cutoffs of Short-Term Heart Rate Variability Parameters in Brazilian Adolescents Male. Pediatr Cardiol. 2018;39(07):1397–1403. doi: 10.1007/s00246-018-1909-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farah B Q, Andrade-Lima A, Germano-Soares A H et al. Physical Activity and Heart Rate Variability in Adolescents with Abdominal Obesity. Pediatr Cardiol. 2018;39(03):466–472. doi: 10.1007/s00246-017-1775-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farah B Q, Prado W L, Tenório T R, Ritti-Dias R M. Heart rate variability and its relationship with central and general obesity in obese normotensive adolescents. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2013;11(03):285–290. doi: 10.1590/s1679-45082013000300005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farah B Q, Barros M V, Balagopal B, Ritti-Dias R M. Heart rate variability and cardiovascular risk factors in adolescent boys. J Pediatr. 2014;165(05):945–950. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmeira A C, Farah B Q, Soares A HG et al. Associação entre a atividade física de lazer e de deslocamento com a variabilidade da frequência cardíaca em adolescentes do sexo masculino. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2017;35:302–308. doi: 10.1590/1984-0462/;2017;35;3;00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gohil A, Hannon T S. Poor Sleep and Obesity: Concurrent Epidemics in Adolescent Youth. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:364. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuentes R M, Notkola I L, Shemeikka S, Tuomilehto J, Nissinen A. Tracking of systolic blood pressure during childhood: a 15-year follow-up population-based family study in eastern Finland. J Hypertens. 2002;20(02):195–202. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200202000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodríguez-Colón S M, Bixler E O, Li X, Vgontzas A N, Liao D. Obesity is associated with impaired cardiac autonomic modulation in children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6(02):128–134. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2010.490265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henje Blom E, Olsson E M, Serlachius E, Ericson M, Ingvar M. Heart rate variability is related to self-reported physical activity in a healthy adolescent population. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;106(06):877–883. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1089-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chamorro R, Algarín C, Rojas O et al. Night-time cardiac autonomic modulation as a function of sleep-wake stages is modified in otherwise healthy overweight adolescents. Sleep Med. 2019;64:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.STROBE Initiative . von Elm E, Altman D G, Egger M, Pocock S J, Gøtzsche P C, Vandenbroucke J P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmeira A C, Farah B Q, Soares A HG et al. Association between Leisure Time and Commuting Physical Activities with Heart Rate Variability in Male Adolescents. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2017;35(03):302–308. doi: 10.1590/1984-0462/;2017;35;3;00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soares A H, Farah B Q, Cucato G G et al. Is the algorithm used to process heart rate variability data clinically relevant? Analysis in male adolescents. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2016;14(02):196–201. doi: 10.1590/S1679-45082016AO3683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gondim R M, Farah B Q, Santos CdaF, Ritti-Dias R M. Are smoking and passive smoking related with heart rate variability in male adolescents? Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2015;13(01):27–33. doi: 10.1590/S1679-45082015AO3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cole T J, Bellizzi M C, Flegal K M, Dietz W H. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320(7244):1240–1243. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology . Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Circulation. 1996;93(05):1043–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farah B Q, Lima A H, Cavalcante B R et al. Intra-individuals and inter- and intra-observer reliability of short-term heart rate variability in adolescents. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2016;36(01):33–39. doi: 10.1111/cpf.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor R W, Jones I E, Williams S M, Goulding A. Evaluation of waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and the conicity index as screening tools for high trunk fat mass, as measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, in children aged 3-19 y. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(02):490–495. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.2.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cavill N, Bidlle S, Sallis J. Health enhancing physical activity for young people: Statement of United Kingdom expert consensus conference. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2001;13:12–25. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gradisar M, Gardner G, Dohnt H. Recent worldwide sleep patterns and problems during adolescence: a review and meta-analysis of age, region, and sleep. Sleep Med. 2011;12(02):110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cavalcanti L MLG, Lima R A, Silva C RM, Barros M VG, Soares F C.Constructs of poor sleep quality in adolescents: associated factors Cad Saude Publica 20213708e00207420. Doi: 10.1590/0102-311. Doi: X00207420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Almeida G MF, Nunes M L. Sleep characteristics in Brazilian children and adolescents: a population-based study. Sleep Med X. 2019;1:100007. doi: 10.1016/j.sleepx.2019.100007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aeschbach D, Cajochen C, Landolt H, Borbély A A.Homeostatic sleep regulation in habitual short sleepers and long sleepers Am J Physiol 1996270(1 Pt 2):R41–R53. 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.1.R41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kageyama T, Nishikido N, Kobayashi T, Kurokawa Y, Kaneko T, Kabuto M. Self-reported sleep quality, job stress, and daytime autonomic activities assessed in terms of short-term heart rate variability among male white-collar workers. Ind Health. 1998;36(03):263–272. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.36.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagai M, Hoshide S, Kario K. Sleep duration as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease- a review of the recent literature. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2010;6(01):54–61. doi: 10.2174/157340310790231635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meerlo P, Sgoifo A, Suchecki D. Restricted and disrupted sleep: effects on autonomic function, neuroendocrine stress systems and stress responsivity. Sleep Med Rev. 2008;12(03):197–210. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J, Ma R C, Kong A P et al. Relationship of sleep quantity and quality with 24-hour urinary catecholamines and salivary awakening cortisol in healthy middle-aged adults. Sleep. 2011;34(02):225–233. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang Y, Mai W, Hu Y et al. Poor sleep quality, stress status, and sympathetic nervous system activation in nondipping hypertension. Blood Press Monit. 2011;16(03):117–123. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e328346a8b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hurtado-Alvarado G, Pavón L, Castillo-García S A et al. Sleep loss as a factor to induce cellular and molecular inflammatory variations. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013:801341. doi: 10.1155/2013/801341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosa Neto J C, Lira F S, Venancio D P et al. Sleep deprivation affects inflammatory marker expression in adipose tissue. Lipids Health Dis. 2010;9:125. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-9-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faraut B, Boudjeltia K Z, Vanhamme L, Kerkhofs M. Immune, inflammatory and cardiovascular consequences of sleep restriction and recovery. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(02):137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.von Känel R, Carney R M, Zhao S, Whooley M A. Heart rate variability and biomarkers of systemic inflammation in patients with stable coronary heart disease: findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100(03):241–247. doi: 10.1007/s00392-010-0236-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matulewicz N, Karczewska-Kupczewska M. Insulin resistance and chronic inflammation. Postepy Hig Med Dosw. 2016;70(00):1245–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carissimi A, Dresch F, Martins A C et al. The influence of school time on sleep patterns of children and adolescents. Sleep Med. 2016;19:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]