Abstract

Background:

Social connectedness and mental health have been associated with infant birth weight, and both were compromised by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Aims:

We sought to examine whether changes in maternal prenatal social contact due to the COVID-19 pandemic were associated with infant birth weight and if maternal prenatal mental health mediated this association.

Study Design:

A longitudinal study of mothers and their infants born during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Subjects:

The sample consisted of 282 United States-based mother-infant dyads.

Outcome Measures:

Depressive symptoms were measured with the Beck Depression Inventory-II, anxiety was measured with the State Anxiety Inventory, and stress was measured using the Perceived Stress Scale 14. We also asked participants about pandemic-related changes in social contact across domains. Adjusted birth weight was calculated from birth records or participant-report when birth records were unavailable.

Results:

Decreases in social contact during the pandemic were associated with lower adjusted infant birth weight (B = 76.82, SE = 35.82, p =.035). This association was mediated by maternal prenatal depressive symptoms [Effect = 15.06, 95% CI (0.19, 35.58)] but not by prenatal anxiety [95% CI (−0.02, 32.38)] or stress [95% CI (−0.31, 26.19)].

Conclusion:

These findings highlight concerns for both mothers and infants in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, since birth weight can have long-term health implications and the social restructuring occasioned by the pandemic may lead to lasting changes in social behavior.

Keywords: adjusted birth weight, coronavirus, mental health, maternal, perinatal, social support

Introduction

Birth weight may predict adult health risks, with associations found between low birth weight and cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, cancer, and psychiatric problems [1]. The relationship between birth weight and adult diseases has been explained by fetal programming hypotheses, which posit that maternal stress and nutrition during pregnancy can alter fetal development in ways that predispose individuals to adverse outcomes [2]. Prenatal maternal social support has been linked with birth weight in multiple studies [3–6]. However, to date, no research has explored the relationship between social contact and birth weight during the COVID-19 pandemic, a time of dramatic restructuring in social connection.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected individuals’ pregnancy experiences in multiple ways. Preterm birth rates dropped in the first months of lockdown, perhaps due to reductions in air pollution and occupational demands on pregnant women [7]. A comparison of over 300,000 women who gave birth in the U.S. during the first 16 months of the pandemic with women who delivered infants the prior year did not find differences in infant birth weight [8]. These findings suggest that pandemic lockdowns were not linked with large-scale adverse gestational outcomes. However, this does not preclude individual differences in pandemic responses that may affect maternal and infant well-being. Several studies have linked maternal stress and anxiety during the pandemic with lower infant birth weight [9–11]. For example, higher stress about being unprepared for birth due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions predicted lower birth weight in a U.S. cohort after adjustment for gestational age [6], and fear of COVID-19 during pregnancy predicted lower birth weight in a Canadian sample [9]. The current study is the first to examine how mother-reported changes to social contact early in the pandemic predict subsequent infant birth outcomes.

Social Support and Birth Weight

Pre-pandemic research motivates the hypothesis that pandemic-related changes in prenatal maternal social contact may predict birth weight. One study found low social support as an independent predictor of low birth weight in the context of neighborhood disadvantage [5]. In contrast, other research has found that women with more extensive social networks have babies with higher birth weights [3]. However, some studies have found mixed or null results when assessing the association between social support and birth weight [6,12,13]. For example, in a community sample of first-time mothers, prenatal perceived social support did not significantly predict any birth outcomes, including birth weight [14]. Hence, more work is needed, especially given the COVID-19 pandemic’s widespread and disruptive effects on social connection.

Perinatal Mental Health

The relationship between prenatal social support and birth weight may be mediated by prenatal mental health. Decreases in prenatal social support may put women at risk for developing depression and anxiety and reduce their ability to regulate stress [15–18]. A robust body of research links prenatal mental health complications with infant birth weight [19,20]. For example, research has shown that as exposure to prenatal stressful life events increases, infant birth weight decreases [21], and higher symptoms of depression and anxiety help to explain this association [13,19,22]. Studies of natural disasters have informed this literature. For example, expectant mothers in the New York City area who developed mental health problems following the 9/11 attacks were more likely to deliver lower birth weight infants [23].

Associations between perinatal social contact, mental health, and birth weight during the COVID-19 pandemic have not yet been thoroughly investigated. Maternal mental health concerns have risen during the pandemic, with studies finding increased prenatal stress, anxiety, and depression compared to pre-pandemic groups [24–29]. Social isolation and loneliness may heighten the risk of mental health problems during the pandemic. In a sample recruited early in the COVID-19 pandemic, 40–44% of pregnant women reported low mood due to loneliness and disconnection from friends and family [30,31]. Another sample of new mothers in Spain reported less contact with supportive relatives during and after the birth of their infant [32], and expectant parents in the UK reported less supportive interactions with healthcare providers [33]. Among pregnant Chinese women, higher perceptions of social support during the pandemic were associated with lower levels of anxiety [34]. Associations between social contact and mental health among prenatal samples warrant more exploration.

Objectives and Hypothesis

This study aims to explore birth outcomes among infants born to individuals who were pregnant during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, starting when COVID-19 was declared a national emergency by the CDC in March 2020; based on an analysis of rising and falling case rates, the first wave of the pandemic has been defined as March-July 2020 [35].

Researchers have shown that prenatal social support may be associated with infant birth weight through processes involving fetal growth rather than the timing of delivery [4]. Additionally, a systematic review found that disasters of various types may reduce fetal growth but do not appear to affect gestational age at birth [36]. Therefore, our key outcome was birth weight adjusted for gestational age rather than birth weight or gestational age alone. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the association between prenatal social contact during the COVID-19 pandemic and infant birth weight, as well as the first to assess maternal mental health as a mediator. We tested the following hypotheses:

Individuals who were pregnant during the COVID-19 pandemic will report significant decreases in social contact as compared to their pre-pandemic lifestyles.

Greater reductions in maternal prenatal social contact during the pandemic will predict lower infant birth weight.

Maternal prenatal stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms will mediate the relationship between social contact and birth weight.

Materials and Methods

Participants

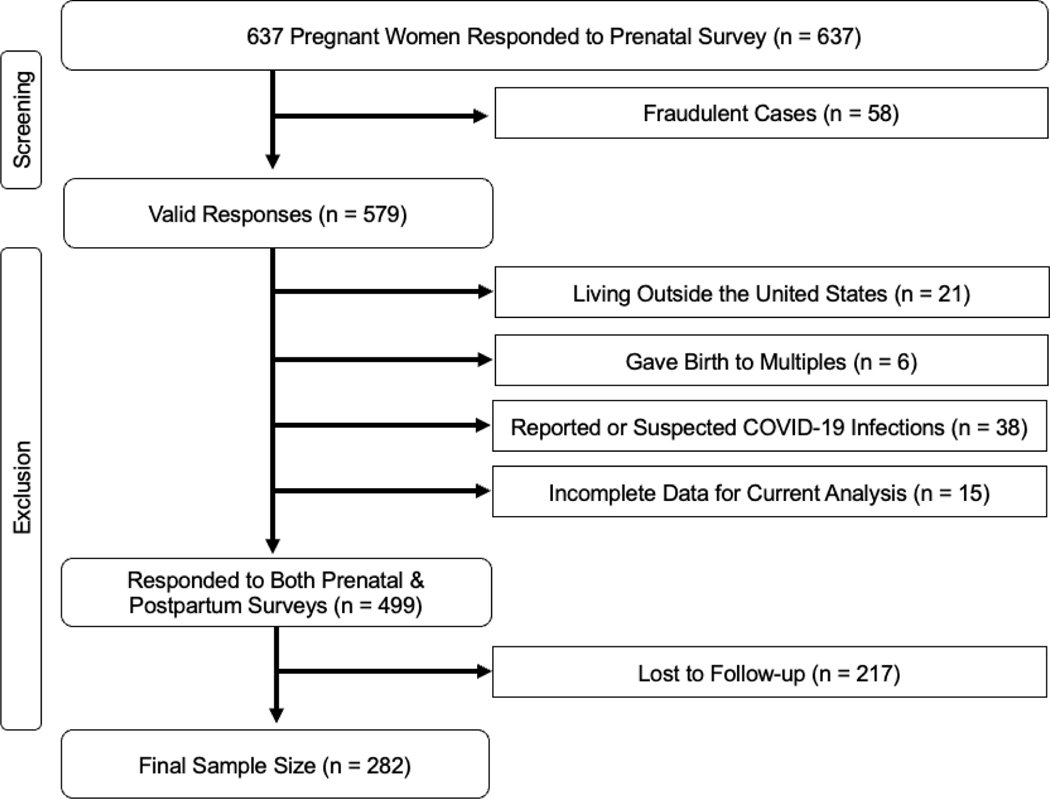

Pregnant individuals were recruited via social media (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, online pregnancy/parenting groups and message boards) to complete the online [study title removed] survey during the first wave of the COVID-19 lockdowns in the United States. Data collection began on April 6th, 2020, corresponding with peak “sheltering in place” behavior in the United States. We closed the survey on July 30th, 2020, meaning that our prenatal data collection aligned with the first wave of the pandemic [37]. Participants provided consent and completed a 20–30-minute questionnaire through the Qualtrics platform. Participants were contacted again via email at three months postpartum to complete a follow-up questionnaire. We also requested participant consent to access birth records. All study procedures were approved by the [university name removed] Institutional Review Board, and participants were offered a downloadable list of mental health resources following survey completion. Participants were incentivized to complete the prenatal survey via entry into a gift card raffle and were paid to participate in the postpartum survey. Data were monitored for fraudulent responses (described in Figure 1), and fraudulent data were excluded from all analyses.

Figure 1: Flowchart of study participants.

Breakdown of study participants and exclusions.

* To determine fraudulent data, participant responses were investigated if data was invalid (i.e., four-digit zip code), the baby’s birthday exceeded their due date by over two weeks, or there was a mismatch in data between prenatal and three-month surveys (i.e., respondents stated that they themselves were pregnant during the prenatal survey but that their partner gave birth on the three-month survey). Additionally, participant emails were monitored against fraudulent email lists, and the participant’s zip code was compared to their IP address. Participants were contacted to clarify discrepancies and were deemed fraudulent if major discrepancies remained following attempted clarification.

**To avoid any confounding effects of a COVID-19 infection, we excluded 38 subjects who reported having a confirmed or suspected case of COVID-19 at some point between the start of their pregnancy and three months postpartum. While this may have captured subjects that contracted COVID-19 following birth, we did not have granular enough data to distinguish the timing of COVID-19 infection, and thus, we took a conservative approach in excluding all subjects who reported having COVID-19 at some point prior to the three-month postpartum survey.

Of the initial 637 prenatal surveys, 58 cases were identified as fraudulent and removed from the dataset, and an additional 366 women responded to the three-month postpartum surveys, a retention rate of 57.46%. Of these, 84 participants were excluded for various reasons, as shown in the flow chart in Figure 1. Of the remaining 499 subjects, 217 did not respond to the three-month survey, a retention rate of 56.51%. Participants who were lost to follow-up at the three-month survey did not significantly differ from those who completed the three-month survey on measures of depressive symptoms, anxiety, stress, or social contact. However, participants who completed the 3-month survey were significantly more educated and older than those who did not complete the 3-month survey. Given this difference, we controlled for age and education in all analyses. Within this final group, sample sizes differed slightly by questionnaire, since participants may have skipped items or logged off before completing the full survey. In total, 281 participants completed the stress measure, 272 completed the anxiety measure, and 260 completed the depressive symptoms measure.

Demographic data is shown in Table 1 along with descriptives of psychosocial measures. Participants were recruited at any point during pregnancy, with the majority in the second (49.3%) or third (43.6%) trimester. Notably, this sample was predominantly white (78.0%) and highly educated, with 86.9% having a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Table 1.

Demographics and Sample Descriptives

| n | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth Weight | 282 | 3408.75 | 474.23 |

| Days Pregnant at Prenatal Survey | 282 | 180.68 | 59.39 |

| Days of Fetal Exposure to Pandemic | 282 | 132.84 | 61.18 |

| Maternal age (years) | 282 | 32.54 | 4.14 |

| Social Contact Score | 282 | 1.82 | 0.82 |

| Depressive Symptoms | 260 | 14.17 | 8.54 |

| State Anxiety Symptoms | 272 | 46.99 | 12.63 |

| Stress Symptoms | 281 | 28.40 | 7.79 |

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| First Time Parents | 157 | 55.7 |

| Trimester at Prenatal Survey First |

20 | 7.1 |

| Second | 139 | 49.3 |

| Third | 123 | 43.6 |

| Race / Ethnicity White |

220 | 78.0 |

| Black | 17 | 6.0 |

| Hispanic / Latinx | 24 | 8.5 |

| American Indian / Alaska Native | 0 | 0.0 |

| Asian / Pacific Islander | 15 | 5.3 |

| Multiracial / Other | 6 | 2.1 |

| Education Did Not Complete High School |

1 | 0.4 |

| High School Degree / GED | 15 | 5.3 |

| Some College | 11 | 3.9 |

| Associate Degree | 10 | 3.5 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 82 | 29.1 |

| Master’s Degree | 85 | 30.1 |

| Professional / Doctoral Degree | 78 | 27.7 |

| Preterm Births | 10 | 3.6 |

Measures

Birth Weight

As part of the prenatal survey, participants were asked to report their infant’s due date, and as part of the three-month survey, participants were asked to report their infant’s birth date and birth weight (pounds and ounces). Adjusted birth weight was calculated as birth weight divided by gestational age at birth (in weeks) times 40 weeks.

Participants were also asked to sign a release of information allowing the study team to access their medical birth records directly from the delivery hospital or birth center. 141 participants consented to the release of their birth records, and we were able to obtain 102 records (73.34% of consented records; 36.17% of the current sample). Participant-reported data was available for an additional 180 participants (63.83% of the sample). Both chart-reported and participant-reported birth weight (r = .99, p < .001) and gestational age (r = .98, p < .001) were highly correlated. Therefore, in an effort to maximize sample size, when medical records were unavailable, participant-reported birth weight and gestational age was used.

Social Connection

Pandemic-related changes to prenatal social contact were assessed by asking, “As compared to before COVID-19, how much total contact (including in-person, phone, or online) do you have with …” 1) neighbors/community members, 2) coworkers, 3) friends, and 4) family. Responses were given on a five-point scale (“1, much less” to “5, much more”), and a social contact score was created by averaging their responses across each of the four sets of contacts. Reliability for our social contact score within our current sample was acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha = .75).

Depressive Symptoms

Parental prenatal depressive symptoms were measured using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; [38]), a 21-item self-report questionnaire that has been comprehensively validated and widely used to assess mental and somatic complaints related to depression, including loss of pleasure and changes to sleep and appetite. Respondents rate items on a three-point scale ranging from “0, not at all” to “3, severely.” Scores are summed for a total score ranging from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptoms.

Anxiety

Prenatal anxiety was assessed using the State Anxiety Inventory (STAI; [39]), a widely used and well-validated instrument to assess momentary feelings of anxiety. Participants rate 20 items, such as “I feel nervous” and “I am tense,” using a four-point scale (ranging from “Not at all” to “Very much so”). Responses were summed for a total score of 20 to 80, with higher scores reflecting greater anxiety.

Stress

Prenatal stress was measured using the Perceived Stress Scale 14 (PSS-14; [40]), an extended version of the most widely used psychological instrument for measuring perceived stress (the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale; [41]) that includes 14 self- report items assessing how often participants experienced feelings of stress. Responses for each question, ranging from “0, never” to “4, almost always,” are summed for a score of 0 to 56, with higher scores reflecting higher perceptions of stress.

Analyses

Analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS version 28 [42]. Zero-order correlations (Table 2) were used to assess relationships between key study variables. All assumptions of regression, as tested through statistical testing and visual inspection, were adequately met. Two low-birth-weight outliers (>3 standard deviations from the mean) were confirmed to be valid entries and therefore retained in analyses. Bootstrapping techniques with 5000 bootstrap samples were used for all analyses to deal with outliers and to produce more robust results. Linear regression was used to assess the association between social contact and birth weight. The PROCESS [43] macro was used to test for mediation effects of our mental health variables and variables were mean-centered. All analyses were conducted controlling for maternal age, first-time parenthood, and maternal education due to well- established associations between these factors and birth weight [44–47]. We also controlled for maternal identification as non-White. Because birth weight was not significantly associated with any single racial/ethnic identification within our sample, maternal identification as non-White was used for parsimony. Finally, variations in prenatal exposure to the pandemic, which may have affected the duration of changes in social contact during pregnancy, were accounted for by including the number of days between March 11th, 2020, the day the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic, and the infant’s birth date. These covariates were all entered simultaneously in one regression model.

Table 2.

Zero-Order Correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Birth Weight | - | ||||||||

| 2. Social Contact | .13* | - | |||||||

| 3. Depressive Symptoms | −.19** | −.16** | - | ||||||

| 4. State Anxiety | −.15* | −.15* | .62** | - | |||||

| 5. Stress Symptoms | −.12* | −.14* | .65** | .74** | - | ||||

| 6. Days of Fetal Exposure to Pandemic | −.07 | .05 | −.002 | −.10* | −.11* | - | |||

| 7. Maternal Age | −.01 | −.01 | −.22** | −.12* | −.14* | −.10 | - | ||

| 8. First Time Parent | .13* | −.06 | .02 | −.02 | .05 | −.20** | .20** | - | |

| 9. Highest Education | .03 | .08 | −.22** | −.01 | −.08 | .07 | .34** | −.06 | - |

| 10. Minority Status | .03 | .01 | −.03 | −.06 | −.05 | .17** | −.08 | −.08 | −.03 |

| 11. Black | −.01 | .13 | −.10 | −.10 | −.06 | .13 | −.03 | −.04 | −.12 |

| 12. Hispanic / Latina | .04 | −.14* | −.01 | −.03 | .04 | .05 | −.17** | .02 | −.15* |

| 13. Asian / Pacific Islander | .04 | .19** | −.05 | −.06 | −.12 | .13* | .11 | −.11 | .20** |

| 14. Multiracial / Other | −.02 | −.12 | .08 | .06 | .05 | .001 | .02 | .05 | .04 |

Note:

p < 0.05

p < .01

Of note, we only had information on infant sex for the subjects with birth record data. Because we could not control for infant sex in our larger analyses, we confirmed that maternal prenatal social contact was not systematically different based on infant sex in those with medical record data; t(104) = −1.30, p = .138. Likewise, infant sex was not significantly associated with maternal mental health variables.

Results

Social Contact During COVID-19

As shown in Table 1 and Figure 2, participants reported steep declines in the amount of time interacting with friends, family, coworkers, and community as compared to before the pandemic.

Figure 2: Reported changes in social contact.

Breakdown of participant responses when asked about their contact with family, friends, coworkers, and community as compared with before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Social Contact and Birth Weight

Results of the regression model are shown in Table 3. Consistent with our expectations, women who reported that their social contact decreased during the pandemic subsequently delivered infants of lower birth weight (B = 76.82, SE = 35.82, p = .035) after controlling for maternal age, education, parity, maternal age, and identification as White vs. non-White.

Table 3.

Regression analyses with 5000 bootstrap samples predicting birth weight based on social contact within the pandemic group (n = 282). R2 = .02, F(6, 275) = 2.06, p = .058.

| Model Variables | B | SE | p | CI (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 3228.00 | 233.65 | <.001 | 2774.59, 3682.81 |

| Social Contact | 76.82 | 35.82 | 0.035 | 4.61, 146.97 |

| Fetal Exposure to Pandemic | −0.50 | 0.45 | 0.272 | −1.39, 0.38 |

| Maternal Age | −5.73 | 6.85 | 0.394 | −19.23, 8.02 |

| First Time Parent | 133.91 | 58.94 | 0.024 | 19.20, 252.42 |

| Highest Education | 19.39 | 25.37 | 0.447 | −29.18, 69.19 |

| Non-White Identification | 59.33 | 71.26 | 0.409 | −82.29, 199.81 |

Mental Health

Zero-order correlations (Table 2) indicated that higher prenatal depressive symptoms and state anxiety predicted lower birth weight. Consistent with our hypothesis, maternal prenatal depressive symptoms significantly mediated the relationship between prenatal social contact and birth weight [indirect effect = 15.06, 95% CI (0.19, 35.58), confidence interval not containing zero]. Contrary to our expectations, neither prenatal maternal anxiety nor perceived stress mediated the association between pandemic-related decreases in social contact and infant birth weight; confidence intervals for these models [95% CI (−0.02, 32.38] and [95% CI (−0.31, 26.19)], respectively, both contained zero.

Discussion

This study extended the literature on social support and birth weight by examining pandemic-related changes in social contact among women who were pregnant during the first wave of COVID-19 lockdowns in spring 2020. We found that pregnant individuals in our sample reported substantial declines in time interacting with friends, family, coworkers, and community members during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic as compared to before the pandemic, and that greater decreases in expectant mothers’ overall social contact predicted lower infant birth weights. Moreover, prenatal maternal depressive symptoms mediated the relationship between social contact and infant birth weight. Contrary to our expectations, neither prenatal anxiety nor perceived stress mediated the association between prenatal social contact and infant birth weight, suggesting a specific role for prenatal depressive symptoms in helping to explain the association between changes in social connection and infant birth weight.

This study is consistent with other findings that pandemic-related distress is associated with birth weight and other gestational outcomes [9–11], but is the first to focus specifically on social contact. Our findings provide further evidence for the relationship between social contact and birth weight during a period of widespread social change. Moreover, our finding that depressive symptoms mediated the association between prenatal social contact and infant birth weight is consistent with the robust body of research connecting maternal mental health with birth outcomes and suggests that the effects of social contact during the pandemic on unborn infants are shaped through maternal mental health. Even after the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic has resolved, social behavior continues to be reshaped by changes in workplaces, schools, and other community institutions that may continue to reduce everyday social interaction. Perinatal healthcare providers must continue to focus on social connection and maternal prenatal depression. Decades of research have shown that interventions designed to increase maternal social support may show promise in improving birth outcomes [48, 49]. Interventions aimed at supporting maternal social connectedness can be leveraged to not only improve maternal well- being but also enhance birth outcomes.

Future studies should further probe the relationships between maternal prenatal social contact, mental health, and infant development during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, it is possible that decreases in social contact during the COVID-19 pandemic drove symptoms of depression in pregnant individuals or, alternatively, depressive symptoms during the pandemic may have contributed to social withdrawal. Future work may also aim to understand additional factors and confounds, such as how differences in rates of COVID-19 in various communities may impact this relationship.

As COVID-19 shifts to an endemic illness with enduring impacts on our social world, with rising rates of remote work, the continued impact of parental social connection and mental health on children should be considered. Maternal mental health during the first year postpartum may affect child physical development [50], warranting continued exploration of these effects on the growth and health of a generation of children.

Strengths and Limitations

This study is the first to explore the relationship between pandemic-related changes in social contact and maternal prenatal mental health with birth outcomes among infants born during the first year of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns. Because the risk of contracting COVID-19 increases with more social contact, it can be difficult to tease apart the impacts of social connection and COVID-19 infection. A major strength of this study is that we assessed pregnant women within the first six weeks of pandemic lockdowns, when few participants had yet contracted COVID-19, and we also asked our participants if they had developed COVID-19 again at three months postpartum. We were able to exclude the limited number of suspected or confirmed positive COVID-19 cases and circumvent the confounding relationship between social contact and COVID-19 infection.

Another strength of this study was the exploration of birth weight adjusted for gestational age rather than gestational age at birth or birth weight alone. This allows us to understand potential mechanisms related to fetal growth rather than simply measuring the degree of prematurity. Our findings are consistent with previous work finding that prenatal social support is associated with infant birth weight through processes involving fetal growth rather than the delivery timing [4], as well as previous research showing that natural disasters may reduce fetal growth, but do not appear to impact gestational age at birth [36].

The study is limited by the fact that we assessed a well-educated convenience sample recruited via social media. Higher socioeconomic status is known to predict better perinatal mental health, so we expect that a lower-SES sample with greater racial and ethnic diversity might reveal even more striking levels of mental health vulnerability. In addition, only 56.51% of the prenatal participants responded to the three-month postpartum survey, a retention rate that is in line with other online longitudinal survey studies [51], and participants who responded to the three-month survey tended to be older and more highly educated. Although we adjusted for age and education in analyses, it is still possible that the data were distorted by selection bias. Also, because the study was conducted online, participants may have provided inaccurate information. We sought to limit this possibility by following an extensive protocol for identifying fraudulent data. Additionally, this study is limited by the fact that we were not able to obtain medical chart data from all of the participants. This means that we could not control for infant sex at birth and medical complications at the birth, and we had to rely on self-reported birth weight instead of chart-reported birth weight for many of the participants. Maternal prenatal social contact did not appear to differ by infant sex, and we also did not find differences between chart-reported and self-reported birth weight, suggesting that these limitations do not invalidate our findings.

Finally, our analyses tested the potential mediating effects of prenatal distress in the association between social contact and birth weight. This design assumes that decreases in social contact during the pandemic lead to distress; however, it is also possible that distress and fear during the pandemic lead to decreases in social contact. Similarly, because both distress symptoms and social contact were self-reported, it is possible that more depressed individuals perceived greater decreases in social contact due to the negative cognitive biases associated with depression. Because we assessed social contact and distress at the same time point, we cannot conclusively determine the directionality of this relationship. However, the naturalistic design assessing these factors during the COVID-19 pandemic, when local and national restrictions were placed on social contact, provides a strong basis for our interpretation. Future work should explore the directionality of the impacts of distress and social contact during the COVID-19 pandemic by assessing each at multiple time points.

Table 4.

Mediation analysis with 5000 bootstrap samples of association between social contact and birth weight mediated by depressive symptoms.

| Mediation Pathways | B | SE | p | CI (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a: Social Contact → Depressive Symptoms | −1.48 | 0.64 | 0.02 | −2.73, −0.22 |

| b: Depressive Symptoms → Birth Weight | −10.21 | 3.54 | 0.004 | −17.17, −3.24 |

| c’ (direct): Social Contact → Birth Weight | 61.28 | 36.24 | 0.09 | −10.09, 132.65 |

| ab (indirect): Social Contact → Depressive Symptoms → Birth Weight | 15.06 | 9.16 | >.05 | 0.19, 35.58 |

Highlights.

Longitudinal study of pregnancy during the COVID-19 pandemic verses pre-pandemic

Decreases in prenatal social contact are associated with lower infant birth weight

Prenatal depression mediated association between social contact and birth weight

Reduced social contact during COVID-19 may impact maternal and infant health

Funding Source:

This work was supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Grant (DGE-1418060; Morris), American Psychological Association (APA) Dissertation Award (Morris), Society for a Science of Clinical Psychology (SSCP) Dissertation Award (Morris), University of Southern California Gold Dissertation Fellowship Award (Morris), and the USC Center for the Changing Families: Small Grants for COVID-19 (Morris). Additional support for this project came from the NIH-NICHD R01HD104801 (Saxbe), NSF CAREER #1552452 (Saxbe), and USC Zumberge Special Solicitation: Epidemic & Virus Related Research and Development Award (Saxbe). Funding sources were not involved in any portion of study design, data collection, analysis, or writing.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Belbasis L, Savvidou MD, Kanu C, Evangelou E, Tzoulaki I. Birth weight in relation to health and disease in later life: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. BMC Medicine. 2016;14(1). doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0692-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Belbasis L, Savvidou MD, Kanu C, Evangelou E, Tzoulaki I. Birth weight in relation to health and disease in later life: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. BMC Medicine. 2016;14(1). doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0692-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Collins NL, Dunkel-Schetter C, Lobel M, Scrimshaw SC. Social support in pregnancy: Psychosocial correlates of birth outcomes and postpartum depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65(6):1243–58. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.65.6.1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Feldman PJ, Dunkel-Schetter C, Sandman CA, Wadhwa PD. Maternal social support predicts birth weight and fetal growth in human pregnancy. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2000;62(5):715–25. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Nkansah-Amankra S, Dhawain A, Hussey JR, Luchok KJ. Maternal social support and neighborhood income inequality as predictors of low birth weight and preterm birth outcome disparities: Analysis of South Carolina pregnancy risk assessment and monitoring system survey, 2000–2003. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2009;14(5):774–85. doi: 10.1007/s10995-0090508-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Orr ST. Social Support and pregnancy outcome: A review of the literature. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;47(4):842–55. doi: 10.1097/01.grf.0000141451.68933.9f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Calvert C, Brockway M, Zoega H, Miller JE, Been JV, Amegah AK, et al. Changes in preterm birth and stillbirth during COVID-19 lockdowns in 26 countries. Nature Human Behaviour. 2023;7(4):529–44. doi: 10.1038/s41562-023-01522-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Litman EA, Yin Y, Nelson SJ, Capbarat E, Kerchner D, Ahmadzia HK. Adverse perinatal outcomes in a large United States birth cohort during the covid-19 pandemic. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM. 2022;4(3):100577. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2022.100577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Giesbrecht GF, Rojas L, Patel S, Kuret V, MacKinnon AL, Tomfohr-Madsen L, et al. Fear of covid-19, mental health, and pregnancy outcomes in the pregnancy during the COVID-19 pandemic study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2022;299:483–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Khoury JE, Atkinson L, Bennett T, Jack SM, Gonzalez A. Prenatal distress, access to services, and birth outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from a longitudinal study. Early Human Development. 2022; doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4033380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Preis H, Mahaffey B, Pati S, Heiselman C, Lobel M. Adverse perinatal outcomes predicted by prenatal maternal stress among U.S. women at the COVID-19 pandemic onset. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2021;55(3):179–91. doi: 10.1093/abm/kaab005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Campos B, Schetter CD, Abdou CM, Hobel CJ, Glynn LM, Sandman CA . Familialism, social support, and stress: Positive implications for pregnant latinas. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14(2):155–62. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dunkel Schetter C. Psychological science on pregnancy: Stress processes, biopsychosocial models, and emerging research issues. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62(1):531–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Duroux M, Stuijfzand S, Sandoz V, Horsch A. Investigating prenatal perceived support as protective factor against adverse birth outcomes: A community cohort study. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2021;41(3):289–300. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2021.1991565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bedaso A, Adams J, Peng W, Sibbritt D. The relationship between social support and mental health problems during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reproductive Health. 2021;18(1). doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01209-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Giesbrecht GF, Poole JC, Letourneau N, Campbell T, Kaplan BJ. The buffering effect of social support on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function during pregnancy. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2013;75(9):856–62. doi: 10.1097/psy.0000000000000004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Webster J, Nicholas C, Velacott C, Cridland N, Fawcett L. Quality of life and depression following childbirth: Impact of social support. Midwifery. 2011;27(5):745–9. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2010.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: A synthesis of recent literature. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2004;26(4):289–95. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bussières E-L, Tarabulsy GM, Pearson J, Tessier R, Forest J-C, Giguère Y. Maternal prenatal stress and infant birth weight and gestational age: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Developmental Review. 2015;36:179–99. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2015.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M. Prenatal depression effects on the fetus and newborn: A Review. Infant Behavior and Development. 2006;29(3):445–55. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA, Porto M, Dunkel-Schetter C, Garite TJ. The association between prenatal stress and infant birth weight and gestational age at birth: A prospective investigation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1993;169(4):858–65. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90016-c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Dunkel Schetter C, Tanner L. Anxiety, depression and stress in pregnancy. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2012;25(2):141–8. doi: 10.1097/yco.0b013e3283503680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lipkind HS, Curry AE, Huynh M, Thorpe LE, Matte T. Birth outcomes among offspring of women exposed to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2010;116(4):917–25. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e3181f2f6a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Caparros-Gonzalez RA, Alderdice F. The COVID-19 pandemic and Perinatal Mental Health. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2020;38(3):223–5. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2020.1786910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Corbett GA, Milne SJ, Hehir MP, Lindow SW, O’connell MP. Health anxiety and behavioural changes of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2020;249:96–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Davenport MH, Meyer S, Meah VL, Strynadka MC, Khurana R. Moms are not ok: Covid-19 and Maternal Mental Health. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health. 2020;1. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2020.00001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hessami K, Romanelli C, Chiurazzi M, Cozzolino M. Covid-19 pandemic and Maternal Mental Health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2020;35(20):4014–21. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1843155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Morris AR, Saxbe DE. Mental health and prenatal bonding in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence for heightened risk compared with a prepandemic sample. Clinical Psychological Science. 2021;10(5):846–55. doi: 10.1177/21677026211049430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383(6):510–2. doi: 10.1056/nejmp2008017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Farewell CV, Jewell J, Walls J, Leiferman JA. A mixed-methods pilot study of perinatal risk and resilience during COVID-19. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health. 2020;11:215013272094407. doi: 10.1177/2150132720944074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Milne SJ, Corbett GA, Hehir MP, Lindow SW, Mohan S, Reagu S, et al. Effects of isolation on mood and relationships in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2020;252:610–1. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Fuente-Moreno M, Garcia-Terol C, Domínguez-Salas S, Rubio-Valera M, Motrico E. Maternity care changes and postpartum mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A Spanish cross-sectional study. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2023;1–16. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2023.2171375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Aydin E, Glasgow KA, Weiss SM, Austin T, Johnson M, Barlow J, et al. Expectant parents’ perceptions of healthcare and support during COVID-19 in the UK: A thematic analysis. 2021; doi: 10.1101/2021.04.14.21255490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Yue C, Liu C, Wang J, Zhang M, Wu H, Li C, et al. Association between social support and anxiety among pregnant women in the third trimester during the coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) epidemic in Qingdao, China: The mediating effect of risk perception. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2020;67(2):120–7. doi: 10.1177/0020764020941567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Demir M, Aslan IH, & Lenhart S. (2023). Analyzing the effect of restrictions on the COVID-19 outbreak for some US states. Theoretical ecology, 16(2), 117–129. 10.1007/s12080-023-00557-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Harville E, Xiong X, Buekens P. Disasters and perinatal health: A systematic review. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 2010;65(11):713–28. doi: 10.1097/ogx.0b013e31820eddbe [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Schaul K, Mayes BR, Berkowitz B. Where Americans are still staying at home the most [Internet]. WP Company; 2020. [cited 2023 Jul 15]. Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/national/map-us-still-staying-home-coronavirus/ [Google Scholar]

- [38].Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown G. Beck Depression Inventory–II. Psychological Assessment. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Spielberger CD. State Trait anxiety inventory. The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology. 2010;1–1. doi: 10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0943 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24(4):385. doi: 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. Perceived stress scale. Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists. 1994. Jul 15;10(2):1–2 [Google Scholar]

- [42].IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh (Version 28.0). 2022. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Buka SL. Neighborhood support and the birth weight of Urban infants. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157(1):1–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF. Low birth weight in the United States. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;85(2). doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.2.584s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Norbeck JS, Anderson NJ. Psychosocial predictors of pregnancy outcomes in low-income black, Hispanic, and White Women. Nursing Research. 1989;38(4). doi: 10.1097/00006199-198907000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Rini CK, Dunkel-Schetter C, Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA. Psychological adaptation and birth outcomes: The role of personal resources, stress, and sociocultural context in pregnancy. Health Psychology. 1999;18(4):333–45. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.18.4.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Norbeck JS, DeJoseph JF, Smith RT. A randomized trial of an empirically-derived social support intervention to prevent low birthweight among African American women. Social Science & Medicine. 1996;43(6):947–54. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(96)00003-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Oakley A. Social Support in pregnancy: The ‘soft’ way to increase birthweight? Social Science & Medicine. 1985;21(11):1259–68. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90275-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Farías-Antúnez S, Xavier MO, Santos IS. Effect of maternal postpartum depression on offspring’s growth. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2018;228:143–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Loxton D, Harris ML, Forder P, Powers J, Townsend N, Byles J, et al. Factors influencing web-based survey response for a longitudinal cohort of young women born between 1989 and 1995. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2019;21(3). doi: 10.2196/11286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]