Abstract

The Tol-Pal proteins of Escherichia coli are involved in maintaining outer membrane integrity. They form two complexes in the cell envelope. Transmembrane domains of TolQ, TolR, and TolA interact in the cytoplasmic membrane, while TolB and Pal form a complex near the outer membrane. The N-terminal transmembrane domain of TolA anchors the protein to the cytoplasmic membrane and interacts with TolQ and TolR. Extensive mutagenesis of the N-terminal part of TolA was carried out to characterize the residues involved in such processes. Mutations affecting the function of TolA resulted in a lack or an alteration in TolA-TolQ or TolR-TolA interactions but did not affect the formation of TolQ-TolR complexes. Our results confirmed the importance of residues serine 18 and histidine 22, which are part of an SHLS motif highly conserved in the TolA and the related TonB proteins from different organisms. Genetic suppression experiments were performed to restore the functional activity of some tolA mutants. The suppressor mutations all affected the first transmembrane helix of TolQ. These results confirmed the essential role of the transmembrane domain of TolA in triggering interactions with TolQ and TolR.

The outer membrane of enteric bacteria such as Escherichia coli acts as a permeability barrier against antibiotics, bile salts, and digestive enzymes, limiting the size of nutrients that diffuse through its pores to approximately 700 Da. The uptake of macromolecules is carried out by the two analogous Tol and Ton systems (for reviews, see references 2, 26, 33, and 43).

The Tol system of E. coli K-12 consists of several proteins which form two complexes in the cell envelope. The TolQ, TolR, and TolA proteins are located in the cytoplasmic membrane, where they interact through some of their transmembrane domains. The TolA N-terminal domain can be cross-linked in vivo with TolQ and TolR (12). The transmembrane segment of TolR interacts with the third transmembrane helix of TolQ (TolQIII), while the TolQI and TolQIII domains appear to be in close proximity (28). Pal and TolB form another complex near the outer membrane (4). In fact, the C-terminal parts of TolA, TolR, and Pal as well as the entire TolB are located in the periplasm (27, 30, 32, 41).

A mutation in any of the tol-pal genes leads to a defect in outer membrane integrity which results in the release of periplasmic content, hypersensitivity to bile salts, and formation of outer membrane blebs at the cell surface (3, 27, 41). The TolQRAB proteins are used for uptake of the group A colicins, while the TolQRA proteins are necessary for the entry of filamentous phage DNA (2, 18, 26, 43).

The Ton system consists of the TonB, ExbB, and ExbD proteins (8). It is involved in the energy-dependent uptake of iron-siderophore complexes and vitamin B12 and in the entry of group B colicins and DNA of phages φ80 and T1. TonB and ExbD are located in the periplasm and anchored to the cytoplasmic membrane via an N-terminal hydrophobic sequence (20, 38). ExbB is a cytoplasmic membrane protein with three membrane-spanning fragments, but most of it is exposed to the cytoplasm (21). The TonB, ExbB, and ExbD proteins are required for optimal coupling of the proton motive force to outer membrane transport processes (6, 34). The periplasmic part of TonB has been proposed to be involved in gating the TonB-dependent transport systems (37); indeed, this protein may shuttle between the outer and cytoplasmic membrane for this purpose (29). Much less is known about the role of the Tol system in the uptake of molecules, probably because no physiological compound transported by this system has been identified. The main difference between the Tol and Ton systems is that the Tol proteins are specifically involved in maintaining outer membrane integrity, raising the possibility that the Tol proteins help in the translocation of some outer membrane components (13, 36).

The TolQR and ExbBD proteins are homologous and can partially replace one another (9, 23). The N-terminal membrane anchors of TolA and TonB also exhibit some homology, while their periplasmic regions are organized in a similar way without any obvious sequence homology (7, 14). The C-terminal domain of TonB interacts with outer membrane proteins; in the case of TolA, this region is clearly involved in the entry of colicins (1, 5, 15) and is the coreceptor of filamentous phages (11, 35). The central domains of TolA and TonB present a regular arrangement which differs in each protein (24, 30).

The N-terminal 32 amino acids of TonB are interchangeable with the first 35 amino acids of TolA (22). This region of TonB plays several roles. It anchors the protein to the cytoplasmic membrane, it is involved in the functional interaction with the ExbBD proteins, and it appears to facilitate translocation of TonB across the cytoplasmic membrane (19, 22, 39). This finding raises the possibility that TolA is also involved in some energy-dependent process; however, no evidence for such a role has been obtained, primarily because, in contrast to the Ton system, no easy uptake experiment can be performed in the Tol system.

In this study, we performed an extensive mutagenesis of the N-terminal part of TolA to characterize more accurately the residues involved in the interaction with TolR and TolQ. A suppressor analysis of some tolA mutants was also carried out to identify the residues of TolQ or TolR able to interact with TolA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The E. coli K-12 strains used in this study were all derivatives of strains JC188 (Hfr P4X metB pstS lacI) and JC8056 (F− supE hsdS met gal ΔlacU169). A chromosomal deletion of the orf1 tolQRA region was constructed as follows. A 7,204-bp EcoRV-BamHI fragment carrying the cydA-tolB region localized at min 16.6 to 16.8 of the E. coli genome (ECDC release 28, March 1997) was cloned. It contained fragments 1241 to 3735 of the JO 3939 sequence and 1 to 4721 of the AE00177 sequence. A 2,856-bp EcoRI-EcoRV fragment containing orfI tolQR and most of tolA was replaced by a 952-bp BstBI restriction fragment, carrying the chloramphenicol cassette from pBR328, after filling in the restriction ends with Klenow enzyme. Finally, a 4,706 MluI-BamHI linearized fragment from the resulting plasmid containing the flanking regions of the chloramphenicol cassette was used to transform a recD strain. Chloramphenicol-resistant, ampicillin-sensitive strains were isolated and analyzed for their tol phenotypes. The mutation was moved to JC188 or JC8056 by P1 transduction using the chloramphenicol marker, and the extent of the deletion was analyzed by Southern blot analysis. In addition, the strain did not express the Orf1, TolR, and TolA proteins, as determined by Western blot analysis using the corresponding antibodies. The tolA mutations are described in Table 1 and Fig. 1. An EcoRI-HpaI fragment carrying the orf1 tolQRA region was cloned into the low-copy-number plasmid pJEL250 (40) (giving pJEL-1QRA) or pT7-5 (giving pT7-1QRA). pT7-1QR was constructed by deleting a HindIII-BamHI fragment from pT7-1QRA; pT7-1QA contained a spontaneous deletion that abolished the start codon of TolR (deletion of the three underlined nucleotides in the sequence ATG GCC AGA, where ATG is the start codon of TolR). pT7-1RA was made by first introducing a SpeI restriction site just downstream of the start codon of TolQ. The GTG ACT GAC ATG sequence was changed to GTG ACT AGT ATC (the SpeI restriction site is underlined). The 5′ end generated by SpeI digestion was removed by mung bean nuclease, and the entire tolQ coding region was removed by further digesting the DNA with MscI, a restriction site localized just downstream the TolR initiation codon (ATG GCC AGA; the MscI site is underlined). TolR was expressed from the start codon of TolQ, and its first alanine residue was changed to threonine (the resulting sequence being GTG ACC AGA). As a result, TolR was fully active since the resulting pT7-RA plasmid was able to complement a tolRA deletion. Cells were grown in LB medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics (31).

TABLE 1.

Phenotypes of tolA mutants and their tolQ suppressorsa

| Plasmid-borne mutation (amino acid change) | Release of alkaline phosphatase (%)b | Sensitivity to cholatec | Relative sensitivity to colicind:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | E1 | E2 | E3 | |||

| None (wild type) | 3 | R | 105 | 103 | 104 | 103 |

| tolQ (G26D) | 3 | R | 105 | 103 | 104 | 103 |

| tolQ (I29S) | 3 | R | 105 | 103 | 104 | 103 |

| tolQ (A30V) | 3 | R | 105 | 103 | 104 | 103 |

| tolA (S18L) | 56 | S | 1 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| tolA (S18L) tolQ (G26D) | 4 | R | 104 | 103 | 104 | 103 |

| tolA (S18L) tolQ (I29S) | 11 | R/S | 104 | 103 | 103 | 103 |

| tolA (S18L) tolQ (A30V) | 3 | R | 104 | 103 | 104 | 103 |

| tolA (H22Y) | 15 | S | 103 | 102 | 102 | 10 |

| tolA (H22Y) tolQ (G26D) | 34 | S | 103 | 103 | 103 | 102 |

| tolA (H22Y) tolQ (I29S) | 47 | S | 102 | 102 | 102 | 10 |

| tolA (H22Y) tolQ (A30V) | 41 | S | 102 | 102 | 102 | 10 |

| tolA (H22P) | 57 | S | 1 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| tolA (H22P) tolQ (G26D) | 3 | R | 105 | 103 | 104 | 103 |

| tolA (H22P) tolQ (I29S) | 13 | R/S | 104 | 103 | 103 | 102 |

| tolA (H22P) tolQ (A30V) | 3 | R | 105 | 103 | 104 | 103 |

| tolA (H22R) | 54 | S | 1 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| tolA (H22R) tolQ (G26D) | 4 | R | 105 | 103 | 104 | 103 |

| tolA (H22R) tolQ (I29S) | 52 | S | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| tolA (H22R) tolQ (A30V) | 3 | R | 105 | 103 | 104 | 103 |

| tolA (F26R) | 6 | S | 103 | 102 | ND | ND |

JC188Δorf1tolQRA derivatives carrying pJEL-1QRA-derived plasmids were tested for release of alkaline phosphatase or sensitivity to colicins and sodium cholate as described in Materials and Methods.

Percentage of alkaline phosphatase activity recovered in the growth. Less than 2% of β-galactosidase activity (used as a cytoplasmic marker) was recovered in the extracellular medium under such conditions.

Ability (R [resistance]) or inability (S [sensitivity]) to grow on plates containing 2.5% sodium cholate.

Highest dilution of a standard colicin solution that resulted in clearing of the strain indicated. ND, not done.

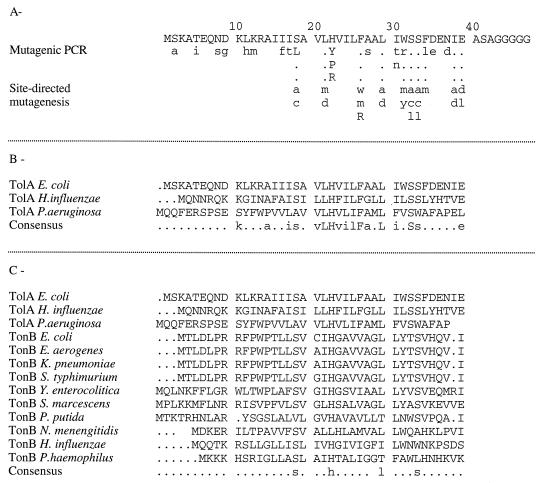

FIG. 1.

(A) Mutations isolated in the N-terminal domain of TolA. The upper line represents the sequence of TolA from E. coli. The substitutions generated in this study are indicated in lowercase letters (no mutant phenotype) or capital letters (tol phenotype). (B) Alignment of TolA sequences from E. coli, Haemophilus influenzae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. (C) Multiple alignment of TolA and TonB sequences (SwissProt release 35.0, GenBank release 104).

Mutagenesis.

We used a mutagenic PCR technique to isolate mutants in this region (10). Briefly, a KpnI site was created in the region between tolR and tolA and did not affect the expression of tolA. A 143-bp KpnI-HindIII fragment was amplified and used to generate the mutants. This region was cloned into pT7-1QRA containing the same KpnI site, and all of the resulting plasmids were used to transform JC8056Δorf1tolQRA. The entire mutated region was sequenced, and only the plasmids containing single mutations were subcloned into pJEL250 and further studied. Additional site-directed mutagenesis was performed with a Quick-Change site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). Suppressor mutants were isolated after treatment of pT7-1QRA with nitrosoguanidine (0.4 mg/ml) as described previously (31), by selection for the ability to restore the growth of tolA mutants in the presence of sodium cholate.

Subcellular fractionation.

Outer and cytoplasmic membranes were separated according to Ishidate et al. (17). All steps were carried out at 4°C as recommended elsewhere (29). For enzymatic analyses, JC188 derivatives were grown in liquid media and the cultures were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was used to assay the release of periplasmic material, while the pellet was resuspended in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). Cells were disrupted after three passages in a French pressure cell, and the resulting crude extract was used to determine the amount of alkaline phosphatase that was not released by the tol mutants. The enzymatic assays for alkaline phosphatase and β-galactosidase have been described elsewhere (27).

Cross-linking experiments.

Cells were recovered in mid- or late exponential phase of growth and cross-linked by using 1% formaldehyde as described by Derouiche et al. (12). Proteins were separated on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–polyacrylamide (12% acrylamide) gel and transferred for 3 h on a nitrocellulose membrane by using a semidry blotter. Immunoblots were revealed with the BM chemiluminescence blotting substrate (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The periplasmic domains of TolA and TolR were tagged at their N termini with six histidines and purified by using the pQE system (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). Antibodies were raised against the periplasmic domains of TolA and TolR.

RESULTS

Mutational analysis of the TolA N-terminal domain.

The N-terminal region of TolA is defined by its 42 first residues, which are separated from the central domain by five glycines (30). It contains a hydrophobic fragment of 21 amino acids (from Ala14 to Phe34) anchoring TolA to the cytoplasmic membrane. We first used a mutagenic PCR technique to isolate mutants in this region. Additional site-directed mutagenesis was performed on three different kinds of residues: (i) residues conserved in TolA or TonB (Fig. 1B and C) which had not been affected by the PCR mutagenesis, (ii) serine residues containing a hydroxyl group able to participate to proton exchange (44), and (iii) aromatic residues which have been proposed to be involved in triggering conformation shifts in some eucaryotic receptors (16).

Mutations were generated in plasmid pT7-1QRA as described in Materials and Methods and subcloned into pJEL250. We isolated 41 independent single mutations affecting 23 of the 42 N-terminal residues of TolA (Fig. 1A). Most of the well-conserved residues of TolA were modified (Fig. 1B). The mutated plasmids were used to transform JC188Δorf1tolQRA, and the phenotype of each mutant was analyzed (Table 1). Five mutations affecting amino acids 18, 22, and 26 affected TolA function. His22 was changed in Arg or Tyr, which also contained dissociable protons, or Pro, able to introduce a turn in the transmembrane helical structure. All these transitions led to an altered TolA protein. Ser residues at position 18, 32, and 33 were changed in Cys (similar size, containing a dissociable proton), Ala (similar size, no dissociable proton), or Leu (larger size, no dissociable proton). Only the Ser18Leu (or S18L, in one-letter code) transition led to an altered tolA phenotype. Therefore, the Ser residues of the TolA transmembrane domain did not appear to be involved in any crucial proton exchange.

TolA N-terminal mutations affect the formation of the TolA-TolQ complex.

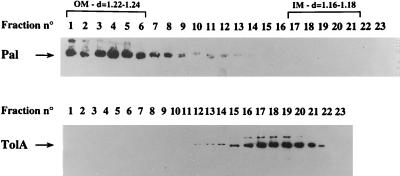

In a first approach to characterize the tolA mutants we investigated the presence and localization of TolA. TolA was recovered in the membrane fraction. The inner and outer membrane were separated on sucrose gradients. All of the mutated proteins were expressed at the same level as the wild-type TolA and localized in the cytoplasmic membrane after separation on sucrose gradients (Fig. 2). The mutated TolA proteins leading to a Tol phenotype appeared to be more unstable than the native polypeptide, as seen by the appearance of degradation products under the band corresponding to TolA (Fig. 3A, lanes 6 to 10). All experiments were performed at 4°C in the conditions mentioned for the compartmentation of TonB, using OmpA and Pal as the outer membrane markers and TolR and the NADH oxidase activity as inner membrane markers (29). In such conditions, TolA was always recovered in the inner membrane fraction at an average density of 1.17. This indicated that in our working conditions, TolA did not appear to shuttle between the inner and outer membrane as it is the case for TonB (29).

FIG. 2.

Subcellular localization of TolA and Pal. Strain JC188 was grown to mid-exponential phase. Inner membranes (IM) and outer membrane (OM) fractions were separated on a sucrose gradient as described in Materials and Methods; 35 fractions were recovered, but only the 23 more relevant are shown. The fraction are shown from the bottom (fraction 1) to the top of the gradient. Densities (d) of the inner and outer membrane fractions are indicated at the top. Only immunoblots of Pal (top) and TolA (bottom) are shown.

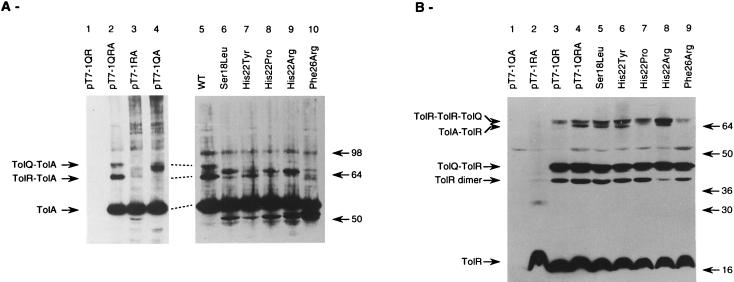

FIG. 3.

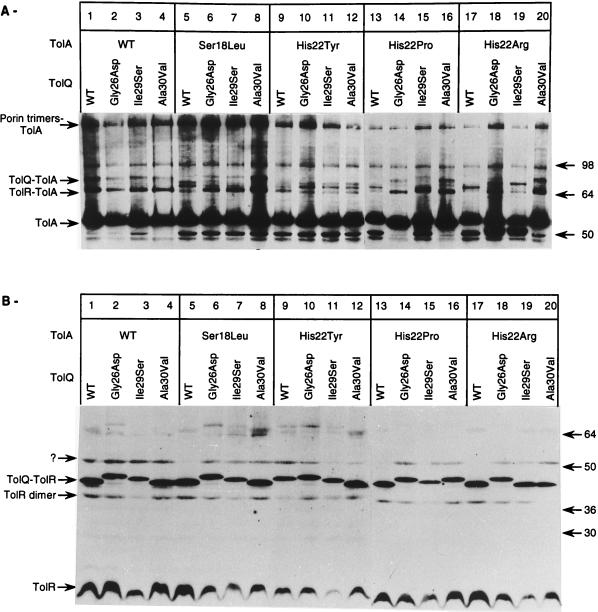

Immunoblot analysis of the TolA and TolR complexes in wild-type and tolA mutant strains cross-linked in vivo for 10 min with 1% formaldehyde. JC188Δorf1tolQRA was transformed with pT7-5 derivatives (controls, 1.5 × 108 cells/well except for pT7-1RA [3 × 108 cells/well]) or with pJEL-1QRA plasmids carrying the tolA mutations (A, lanes 5 to 10, 3 × 108 cells/well). Only results obtained with tolA mutations leading to an altered phenotype are presented. The molecular weights (in thousands) of the standards (See-Blue prestained standards; Novex, San Diego, Calif.) are indicated on the right. Immunoblots were revealed by using antibodies raised against TolA (A) or TolR (B).

In vivo cross-linking experiments were performed to determine the effects of the tolA mutations on the interactions between TolA and TolQ or TolR. These complexes were better visualized when the tolQRA genes were expressed on high-copy-number plasmids, but doing so resulted in a high background of TolA degradation (12). Therefore, we used pJEL250 derivatives to search for a change in complex formation in the tolA mutants as well as to avoid gene dosage effects. Results are presented in Fig. 3. In the parental strain, TolA was detected at a molecular mass of 53 kDa; two additional bands of 64 and 71 kDa were identified with an anti-TolA antibody (Fig. 3A, lane 2). We also detected a 98-kDa band unrelated to TolQ and TolR that might correspond to a TolA dimer. The 64-kDa band was absent in a tolR strain (Fig. 3A, lane 4) and present at a lower level in a tolQ derivative (Fig. 3A, lane 3). As it has been shown that translation of tolR depends on translation of the upstream tolQ region (42), we concluded that this band corresponded to the TolA-TolR complex. The 71-kDa band was absent in a tolQ background (Fig. 3A, lane 3) and present at a lower level in a tolR strain in which intermediate bands that might correspond to degradation products or to an altered mobility of the 71-kDa complex appeared in the region from 64 to 71 kDa (Fig. 3A, lane 4). The 71-kDa band corresponded to a TolQ-TolA complex. These data were in agreement with previously published results (12). The 71-kDa band was absent from all mutants, and in most of them, intermediate bands could be seen in the range of 64 to 71 kDa. The 64-kDa TolA-TolR complex was present but at lower levels, especially in TolA (H22P) strains (Fig. 3A, lane 8), and was absent in TolA (F26R) strains, where intermediate bands could be detected in the range of 58 to 60 kDa (Fig. 3A, lane 10). These bands were not detected by the TolR antibody (Fig. 3B) and probably corresponded to degradation products of the TolQ-TolA complex. From these results, we concluded that tolA mutations affected the formation of correct TolQ-TolA and TolR-TolA complexes.

When TolQ, TolR, and TolA were expressed from pT7-1QRA, we could identify several bands with the TolR antibody (Fig. 3B). TolR migrated at 17 kDa. Two bands of 45 and 68 kDa were absent in a tolQ background (Fig. 3B, lane 2), while a 64-kDa band was missing in a tolA strain (Fig. 3B, lane 3). The 68-kDa band corresponded to a TolQ-TolR-TolR complex, while an additional band of 39 kDa was recently found to be a TolR dimer (19a). The 45- and 64-kDa bands were assumed to be TolQ-TolR and TolR-TolA complexes, respectively. A 53-kDa band corresponded to a contamination since it could be seen even in a strain lacking TolR. Analysis of the tolA derivatives showed that the TolQ-TolR complex was still present in these mutants, while the TolQ-TolA band was greatly reduced in the presence of the TolA(H22P) mutations and absent in the TolA(F26R) background (Fig. 3B, lane 9). Attempts to obtain TolQ antibodies have been unsuccessful, probably because the protein is poorly immunogenic.

Isolation and characterization of tolQ suppressor mutations of tolA (S18L), tolA (H22P), and tolA (H22R).

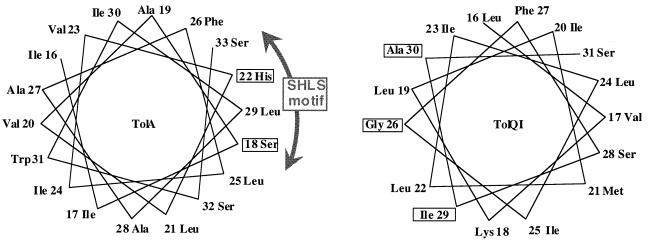

The Ser18 and His22 residues belong to an SHLS motif highly conserved in TolA and TonB (Fig. 1C and reference 23). In a wheel representation of the transmembrane helix of TolA, these residues are clustered in the less hydrophobic face which is most likely to be a zone of protein-protein interaction (Fig. 4). Therefore, we used the four tolA mutants altered in these residues to search for tolQ or tolR extragenic suppressor mutants.

FIG. 4.

Wheel representation of the transmembrane helix of TolA and of the first transmembrane helix of TolQ. Helices were built by using ideal α-helix parameters (3.6 residues/turn).

pT7-1QR was mutagenized with nitrosoguanidine, and the EcoRI-KpnI region carrying the tolQR genes was exchanged with the same fragment of plasmids carrying the tolA mutations. The resulting plasmids were used to transform JC188Δorf1tolQRA, and suppressor mutants able to grow in the presence of sodium cholate were selected. This strain was used to quantify more accurately the release of periplasmic alkaline phosphatase since it constitutively expressed both this enzyme and β-galactosidase, which was used as the cytoplasmic marker. Three independent colonies were obtained, and the mutagenized plasmid region was fully sequenced. We isolated three single tolQ suppressor mutations; tolQ (A30V) and tolQ (I29S) were isolated as suppressor mutants of tolA (S18L), while tolQ (G26D) suppressed tolA (H22R). These residues were on the same face of the first transmembrane helix of TolQ in an helical wheel representation (Fig. 4).

The allele specificity of the suppressor mutants was determined by constructing pJEL250 derivatives carrying the orf1 tolQRA region with all the combinations of the tolA and tolQ alleles. These plasmids were then used to transform JC188Δorf1tolQRA (Table 1). The phenotypes of each strain was carefully checked to control if the tolQ mutants were able to restore all the defects generated by the tolA mutations. In the presence of wild-type TolA protein, none of the tolQ mutations led to an altered tol phenotype, indicating that the changes generated by these mutations were not crucial for TolQ function. The tolQ (A30V) and tolQ (G26D) mutations were able to suppress tolA (S18L), tolA (H22P), and tolA (H22R), while tolQ (I29S) only suppressed partially tolA (S18L) and tolA (H22P). The tolQ suppressors were unable to suppress the tolA (H22Y) mutation and on the contrary enhanced the defects generated by this mutation.

tolQ suppressors restore the ability of tolA mutants to interact with TolQ.

In vivo chemical cross-linking experiments were carried out to evaluate the ability of the mutated TolQ proteins to interact with wild-type and mutated TolA proteins. The 64- and 71-kDa bands corresponding to the TolQ-TolA and TolR-TolA complexes could be seen in strain carrying native TolA together with any of the three tolQ suppressor mutations (Fig. 5). The three tolQ mutants also allowed the formation of the 64- and 71-kDa complexes in the presence of TolA (S18L) protein, although the 71-kDa band was quite faint in the presence of the TolQ (G26D) and TolQ (I29S) mutant proteins (Fig. 5A, lanes 6 and 7). No tolQ mutant was able to restore the 71-kDa band in the tolA (H22Y) mutant (Fig. 5A, lanes 9 to 12). Several bands were present in the range of 64 to 71 kDa. Both TolQ (G26D) and TolQ (A30V) proteins were able to give a correct 64- to 71-kDa pattern with TolA (H22P; Fig. 5A, lanes 14 and 16) and TolA (H22R; Fig. 5A, lanes 18 and 20). However, the TolQ-TolA band was less intense in the TolQ (G26D) background. Here again, several bands of intermediate size could be identified in the presence of the TolQ (I29S) protein. The TolA-porin complexes were present in all genetic backgrounds, confirming the correct interaction between TolAII and porin trimers in the presence of SDS. However, this interaction did not appear to be reproducible in our experimental conditions since such complexes could not be seen in Fig. 3. These results are in agreement with those of Derouiche et al. (13), who showed that these complexes were formed even in the presence of a tolQ nonsense or a tolR null (transposon insertion) mutation. As overnight growth on rich agar plates is roughly equivalent to a late exponential phase of growth in liquid medium, we could compare the phenotypic data to those of the cross-linking experiments. The results presented in Fig. 5 were in agreement with those obtained in Table 1: the recovery of wild-type phenotype by the tolA mutants in the presence of tolQ suppressor mutations corresponded to the presence of even low amounts of TolQ-TolA and TolR-TolA complexes compared to the parental strain.

FIG. 5.

Immunoblot analysis of the TolA and TolR complexes in tolA mutants affected at residue 18 or 22 and in the double tolA tolQ strains. pJEL250 carrying the tolQRA genes was used to transform JC188Δ1QRA. Immunoblots were revealed by using antibodies raised against TolA (A) or TolR (B).

When the immunoblot was revealed with the anti-TolR antibody, the TolQ-TolR band migrated at slightly different molecular weights depending on the tolQ mutation. As the samples were not boiled for a long period to maintain the cross-links, this could reflect a difference in the conformation of the mutated TolQ protein, although a single amino acid change in a protein can lead to differences in migration in SDS-gels. The lack of anti-TolQ antibodies did not allow us to discriminate between these two hypotheses.

DISCUSSION

An extensive mutagenesis of the TolA N-terminal domain has been carried out to characterize the residues essential for its activity. Mutations in only three amino acids led to a mutant phenotype. They did not affect the expression of TolA or its localization into the cytoplasmic membrane. TolA was always recovered in the inner membrane fraction, indicating that TolA did not appear to shuttle between the inner and outer membranes as is the case for TonB (29). Although TolA and TonB are related proteins, their periplasmic parts are rather different. TonB contains an X-Pro region and a C-terminal part which clearly interacted with outer membrane proteins involved in the active transport of vitamin B12 and iron-siderophore complexes. The central domain of TolA contains an alpha-helical structure able to interact with porin trimers in vitro, and its C-terminal domain interacts with colicins during their entry and is the coreceptor of filamentous phage, but no evidence has been obtained that TolA interacts in vivo with any outer membrane protein. However, like its TonB counterpart, it is likely to be at least transiently close to the outer membrane.

All of the TolA mutant proteins were deficient in the formation of the 71-kDa band corresponding to the TolQ-TolA complex (12). In some mutants, as in the tolR control, additional bands that could correspond to degradation products or bands of altered mobility were present. Thus, the stability of the TolQ-TolA complex appeared to be dependent of an appropriate ratio between TolQ, TolR, and TolA.

Our result confirmed the importance of the TolA transmembrane region for its interaction with TolQ and TolR. The highly conserved SHLS motif was subjected to an extensive mutagenesis. To our surprise, only histidine 22 and to a lesser extent serine 18 and phenylalanine 26 residues appeared to play an important role in TolA function. This latter residue is close to histidine 22 and serine 18 in a helical wheel representation of the TolA transmembrane domain and is highly conserved in TolA but not in TonB. The Ser residues of the TolA N-terminal region did not appear to be involved in any proton exchange. Indeed, our mutagenesis showed that many residues of TolA transmembrane domain could be modified without loss of function. None of the single mutations were predicted to affect the overall alpha-helical structure of the transmembrane domain, indicating that Ser18, His22, and Phe26 are important for other functions, including interaction with TolQ.

We could isolate tolQ suppressor mutations of tolA mutants affected at residues 18 and 22. The corresponding mutations affected the first transmembrane domain of TolQ. A wheel representation of both the TolA and TolQI transmembrane helices showed that the involved residues, especially Ser18-His22 of TolA and Gly26-Ala30 of TolQI, were likely to be quite close to each other; this finding probably explains the poor allelic specificity of two of our mutants. In agreement with this localization, the Gly26Asp and Ala30Val tolQ mutants are the most efficient suppressors of the tolA Ser18Leu, His22Pro, and His22Arg mutations. The His22Tyr mutation was not suppressed by any of the tolQ mutants; in this case the tolA-tolQ double mutants were even more altered in their tol phenotypes than the corresponding tolA strain. This probably means that in these double mutants, TolA and TolQ are still unable to interact. Although all of the tolQ suppressor mutants affect the first transmembrane domain of TolQ, their lack of specificity does not allow us to definitely conclude that only this domain is able to interact with TolA.

We could not isolate tolR suppressor mutants of tolA strains altered in residue Ser18 or His22. The most probable explanation is that TolR interacts with other residues of TolA like TolA (F26R); this hypothesis is now being tested in our laboratory. As no ternary complex involving TolQ, TolR, and TolA has been characterized, it would be of interest to identify the residues of TolA associated with TolR to determine whether the interaction between these proteins is sequential or simultaneous.

TolA interacts with TolQ in the same manner as TonB interacts with ExbB (25). This explained why the N-terminal domains of TolA and TonB are interchangeable provided that TolA is associated with TolQR and TonB is associated with ExbBD (22). In view of the results described here and in our previous work (28), as well as the data obtained from the Ton system (25), we propose that TolA, TolQ, and TolR interact in the cytoplasmic membrane via their transmembrane domains. TolA interacts with TolR (12) and TolQI (this report), TolQIII interacts with TolR and TolQI, and the C-terminal domain of TolR should be close to TolQIII (28). Confirmation of this model based on genetic and biochemical data awaits development of a three-dimensional model of these membrane proteins by biophysical methods.

Although we now have a good picture of the potential interactions between the TolQ, TolR, and TolA proteins, several question remain to be answered. We still have no experimental evidence that (i) a ternary complex involving TolQ, TolR, and TolA is formed at least transiently or (ii) any of the TolQRA proteins interacts with the TolB-Pal complex for their function.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Laure Journet and Hélène Bénédetti for sharing results before publication.

This work was supported by grants from the CNRS (Département des Sciences de la Vie) and MESR (ACC-SV6). P.G. was recipient of an AMN fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bénédetti H, Lazdunski C, Lloubès R. Protein import into Escherichia coli: colicins A and E1 interact with a component of their translocation system. EMBO J. 1991;10:1989–1995. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bénédetti H, Géli V. Colicin transport, channel formation and inhibition. In: Konings W N, Kaback H R, Lolkema J S, editors. Handbook of biological physics. Vol. 2. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science B.V.; 1996. pp. 665–691. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernadac A, Gavioli M, Lazzaroni J C, Raina S, Lloubes R. Escherichia coli tol-pal mutants form outer membrane vesicles. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4872–4878. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.18.4872-4878.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouveret E, Derouiche R, Rigal A, Lloubès R, Lazdunski C, Bénédetti H. Peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein-TolB interaction. A possible key to explaining the formation of contact sites between the inner and outer membranes of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11071–11077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouveret E, Rigal A, Lazdunski C, Bénédetti H. The N-terminal domain of colicin E3 interacts with TolB which is involved in the colicin translocation step. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:909–920. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2751640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradbeer C. The proton motive force drives the outer membrane transport of cobalamine in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3146–3150. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.3146-3150.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun V. The structurally related exbB and tolQ genes are interchangeable in conferring TonB-dependent colicin, phage, and albomycin sensitivity. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6387–6390. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.6387-6390.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun V, Günter K, Hantke K. Transport of iron across the outer membrane. Biol Metals. 1991;4:14–22. doi: 10.1007/BF01135552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braun V, Herrmann C. Evolutionary relationship of uptake systems for biopolymers in Escherichia coli: cross complementation between the TonB-ExbB-ExbD and the TolA-TolQ-TolR proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:261–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cadwell R C, Joyce G F. Mutagenic PCR. In: Dieffenbach C W, Dveksler G S, editors. PCR primer, a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. pp. 583–589. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Click E M, Webster R E. Filamentous phage infection: required interactions with the TolA protein. J Bacteriol. 1997;1079:6464–6471. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6464-6471.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derouiche R, Bénédetti H, Lazzaroni J C, Lazdunski C, Lloubès R. Protein complex within Escherichia coli inner membrane: TolA N-terminal domain interacts with TolQ and TolR proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11078–11084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derouiche R, Gavioli M, Bénédetti H, Prilipof A, Lazdunski C, Lloubes R. TolA central domain interacts with Escherichia coli porins. EMBO J. 1996;15:6408–6415. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eick-Helmerich K, Braun V. Import of biopolymers into Escherichia coli: nucleotide sequences of the exbB and exbD genes are homologous to those of the tolQ and tolR genes, respectively. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5127–5134. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5117-5126.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garinot-Schneider C, Penfold C N, Moore G R, Kleanthous C, James R. Identification of residues in the putative TolA box which are essential for the toxicity of the endonuclease toxin colicin E9. Microbiology. 1997;143:2931–2938. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-9-2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hibert M F, Trump-Kallmeyer S, Hofloch J, Bruinuels A. This is not a G-protein coupled receptor. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1993;14:7–13. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90106-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishidate K, Creeger E S, Zrike J, Deb S, Glauner B, MacAlister T J, Rothfield L I. Isolation of differentiated membrane domains from Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium, including a fraction containing attachment sites between the inner and outer membranes and the murein skeleton of the cell envelope. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:428–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James R, Kleanthous C, Moore G R. The biology of E colicins: paradigms and paradoxes. Microbiology. 1996;142:1569–1580. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-7-1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaskula J C, Letain T E, Roof S K, Skare J T, Postle K. The role of the TonB amino terminus in energy transduction between membranes. J Bacteriol. 1994;170:2326–2338. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2326-2338.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19a.Journet, L., and H. Bénédetti. Personal communication.

- 20.Kampfenkel K, Braun V. Membrane topology of the Escherichia coli ExbD protein. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5485–5487. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5485-5487.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kampfenkel K, Braun V. Topology of the ExbB protein in the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1992;268:6050–6057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlsson M, Hannavy K, Higgins C F. A sequence-specific function for the N-terminal signal-like sequence of the TonB protein. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:379–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koebnieck R. The molecular interaction between components of the TonB-ExbBD-dependent and the TolQRA-dependent bacterial uptake systems. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsen R A, Wood G E, Postle K. The conserved proline-rich motif is not essential for energy transduction by Escherichia coli protein. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:943–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larsen R A, Thomas M T, Postle K. Partial suppression of an Escherichia coli TonB transmembrane domain mutation (ΔV17) by a missense mutation in ExbB. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:627–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lazdunski C J. Colicin import and pore formation: a system for studying protein transport across membranes? Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:1059–1066. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazzaroni J C, Portalier R C. The excC gene of Escherichia coli K-12 required for cell envelope integrity encodes the peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein (PAL) Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:735–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lazzaroni J C, Vianney A, Popot J L, Bénédetti H, Samatey F, Lazdunski C, Portalier R, Géli V. Transmembrane α-helix interactions are required for the functional assembly of the Escherichia coli Tol complex. J Mol Biol. 1995;246:1–7. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Letain T E, Postle K. TonB protein appears to transduce energy by shuttling between the cytoplasmic membrane and the outer membrane in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:271–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3331703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levengood S K, Beyer W F, Webster R E. TolA: a membrane protein involved in colicin uptake contains an extended helical region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5939–5943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.5939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller J H. A short course of bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Müller M M, Vianney A, Lazzaroni J C, Portalier R C, Webster R E. Membrane topology of the Escherichia coli TolR protein required for cell envelope integrity. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6059–6061. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.18.6059-6061.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Postle K. TonB and energy transduction between membranes. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1993;25:591–601. doi: 10.1007/BF00770246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Postle K, Skare J T. Escherichia coli TonB protein is exported from the cytoplasm without proteolytic cleavage of its N-terminus. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:11000–11007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riechmann L, Holliger P. The C-terminal domain of TolA is the coreceptor for filamentous phage infection in E. coli. Cell. 1997;90:351–360. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rigal A, Bouveret E, Lloubès R, Lazdunski C, Bénédetti H. The TolB protein interacts with the porins of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7274–7279. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7274-7279.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rutz J M, Liu J, Lyons J A, Goranson J, Armstrong S K, McIntosh M A, Feix J B, Klebba P E. Formation of a gated channel by a ligand-specific transport in the bacterial outer membrane. Science. 1992;258:471–475. doi: 10.1126/science.1411544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skare J T, Postle K. Evidence for a TonB-dependent energy transduction complex in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2883–2890. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Traub I, Gaisser S, Braun V. Activity domains of the TonB protein. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:409–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valentin-Hansen P, Albrechtsen B, Love Larsen J E. DNA-protein recognition: demonstration of three genetically separated operator elements that are required for repression on the Escherichia coli deoCABD promoters by the DeoR repressor. EMBO J. 1986;5:2015–2021. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04458.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vianney A, Lewin T M, Bayer W E, Lazzaroni J C, Portalier R, Webster R E. Membrane topology and mutational analysis of the TolQ protein of Escherichia coli required for the uptake of macromolecules and cell envelope integrity. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:822–829. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.822-829.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vianney A, Muller M, Clavel T, Lazzaroni J C, Portalier R, Webster R E. Characterization of the tol-pal region of Escherichia coli: translational control of tolR expression by TolQ and identification of a new open reading frame downstream of pal encoding a periplasmic protein. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4031–4038. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4031-4038.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Webster R E. The tol gene products and the import of macromolecules into Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1005–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Witkowski A, Nagger J, Witkowska H E, Rhandawa Z I, Smith S. Utilization of an active serine 101-cysteine mutant to demonstrate the proximity of the catalytic serine 101 and histidine 237 residues in thioesterase II. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18488–18492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]