Abstract

Conservation science requires a balance of social and ecological perspectives to understand human–wildlife interactions. We look for an integrative social–ecological framework that emphasizes equal representation across social and ecological conservation sciences. In this perspective, we suggest “social–ecological practice theory”, an integration of general ecological theory and anthropology’s practice theory, for a conservation-minded social–ecological framework to better theorize human–nature relationships. Our approach deliberately pulls from subdisciplines of anthropology, specifically a body of social theory founded by anthropology and social science called practice theory. We then illustrate how to apply social–ecological practice theory to our case study in the Makgadikgadi region of Botswana. We highlight how the practices of people, lions, and cattle—in combination with environmental and structural features—provide the needed context to deepen the understanding of human–wildlife conflict in the region. Social–ecological practice theory highlights the complexity that exists on the landscape, and may more effectively result in conservation strategies for human–wildlife coexistence.

Keywords: Anthropology, Coexistence, Ecology, Human–wildlife conflict, Natural sciences, Social science

Introduction

Human–wildlife conflict (HWC) is characterized as a contentious relationship between wildlife and humans, involving singular events of actions, threats, or perceptions that have negative impacts on either group (Lischka et al. 2018). Overseeing and managing HWC requires an acknowledgment that realized or perceived conflict is driven by local variations across both ecological and social processes (Naughton-Treves and Treves 2005; Dickman 2010; Ban et al. 2013; Bennett et al. 2017; Lischka et al. 2018; Wilkinson et al. 2019). The intertwinement of ecological and social processes is complex; hence, conservation projects aiming to overcome HWC may in fact risk exacerbating it and causing injustices whenever either process is only superficially addressed (Pooley et al. 2017). Addressing the environmental and human dimensions of HWC together requires integrating ecology (Wilkinson et al. 2019) and social sciences (Margulies and Karanth 2018).

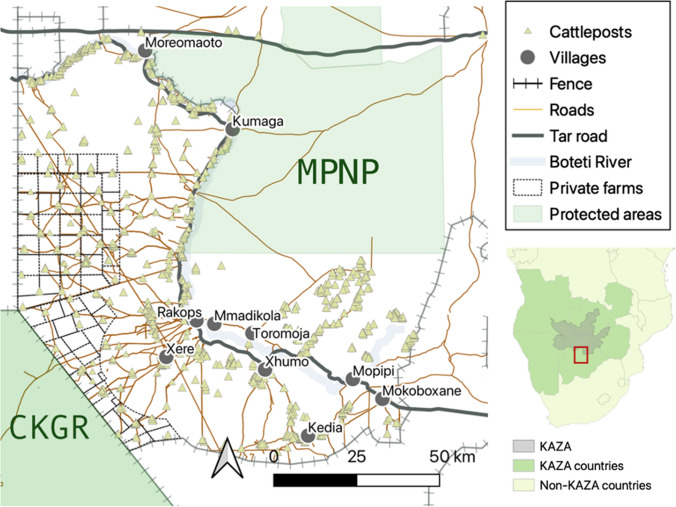

To this end, recent studies of HWC (and positive and negative human–wildlife interactions more broadly) have been drawn to a perspective called Social–Ecological Systems (SES) theory (Pooley et al. 2017; Dressel et al. 2018; Lischka et al. 2018; Lozano et al. 2019). SES explicitly examines the interaction between the ecological and social systems of a given place (Binder et al. 2013). However, the purposes and goals of different SES frameworks are diverse, making it difficult to compare across studies (Binder et al. 2013). What is more, SES theory does not account for how individual characteristics of people and of wildlife shape and are shaped by an amalgamation of environmental, cultural, structural, and socio-political phenomena that span from the individual to the global scale (though see Gadsden et al. 2023). The Central Boteti West sub-district of Botswana, also identified as CT8, is one such place that illustrates the problem. CT8 sits in between the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR) and the Makgadikgadi Pans National Park (MPNP) and has both some of the highest poverty and some of the highest rates of human–wildlife conflict in the country (Valeix et al. 2012; Kesch et al. 2015; Statistics Botswana 2015; Cushman et al. 2018). It is difficult to understand human–wildlife conflict without considering how these phenomena interlink. Thus, generalizations that remain squarely in one discipline can lead to missed opportunities to support human–wildlife coexistence (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study area in the Central Boteti West, also known as CT8, between the Makgadikgadi Pans National Park (MPNP) and the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR) with inset map of the Kavango–Zambezi Transfrontier Area (KAZA) boundary

We propose here a framework called “social–ecological practice theory” (a portmanteau of “social–ecological theory” and “practice theory”) which applies an inductive approach to the integrative understanding of human–nature interdependence. Our blend of social–ecological perspectives intentionally draws on subdisciplines of anthropology—specifically, a body of social theory founded by anthropology and social science called practice theory—to further our understanding of human–wildlife conflict. We demonstrate its application in a case study of human–carnivore conflict in Botswana. We show the ways in which the social and ecological dimensions of a landscape are intermeshed and identify what is gained by incorporating multiple disciplines when studying human–wildlife interactions—specifically of human–carnivore conflict.

Theoretical framework: Social–ecological practice theory, a union of social sciences and general ecology

The practice theory framework was first introduced by Bourdieu (1972) and revolved around the circular relationship between people’s actions (the selected practice) and their societal environment (Bourdieu 1990). Practice theory emerged as a response to the limitations of the structuralist school of thought, which overlooked the active role of individual agents in shaping and perpetuating their social environment and instead believed that the meaning of elements is only relative to other elements. Giddens (1984), another early theorist of practice theory, contributed the idea that social action cannot be explained solely by agency or social structures. Instead, actions are explained by the inseparable reciprocal and nonhierarchical relationship between the two; neither structure nor agency can exist without the other. Giddens championed the study of the mundane activities, rituals, and habits that make up a person’s daily routines (Giddens 1979).

A central idea in practice theory is that an individual's social environment produces internalized mental structures that shape their practice, called habitus, encompassing the social norms and tendencies that guide behavior and thinking, as described by Bourdieu (1972). Habitus consists of dispositions that are formed by both past events and social structures, and they play a significant role in determining an individual's current practices and structures. Furthermore, habitus also influences how individuals perceive and interpret practices (Bourdieu 1990). Habitus is formed within social-spatial arenas, or fields, where individuals engage in the pursuits of capital, such as prestige and financial resources. The social position of an individual within a field is determined by a combination of the specific rules governing that field, the individual's habitus, and their capital. An individual constantly adapts depending on which field they are in through the relative attraction of different practices and access to resources or power relations (Feldman and Orlikowski 2011). Thus, social practices have the capacity to either reproduce existing structures or bring about transformative changes (Whittington 2018). Bourdieu (1990) suggests that practices are analogous to a card game where players make different choices based on their skill and the state of the game. A singular action occurs at a specific place and time, which is influenced by—and adapted to changes in—structures (e.g., rules, habits, routines, cultural norms, materials, technology) and agency (e.g., personal experiences, inner perspectives; Bourdieu and Bourdieu 1977; Giddens 1984).

Borrowing Bourdieu’s language, one could say that wildlife have practices as well, which change as the wildlife-agent attempts to maximize their capital (food, mating opportunities, other resources) based on their roles and relationship (physiology, demography) within their social field in relation to other subjects (species) and objects (environmental variables) (Bleicher 2017; Wilkinson et al. 2019; Balasubramaniam et al. 2020). Wildlife behavior research demonstrates how animals are shaped by structures and individual experiences—including how behavioral variation among individuals in response to benefits and risks contributes to human–wildlife conflict (e.g., landscape of fear; Pettorelli et al. 2011; Bleicher 2017; Wittemyer et al. 2019; Balasubramaniam et al. 2020). This makes the human–wildlife relationship dynamic because each singular human–wildlife conflict event differs, occurring at a specific place and time with specific individuals. Over time, a wildlife-agent internalizes the norms and expectations of their social field based on their experiences and social structures accruing capital, developing habitus, and influencing their practices (actions). In this way, the relationship between carnivores and humans can be seen as constantly adapting and continually being reinterpreted within their social field, including changing socio-political structures. Anthropological studies have previously demonstrated how socio-political structures have shaped human–wildlife conflict (Sjölander-Lindqvist et al. 2015; Margulies and Karanth 2018; Fletcher and Toncheva 2021). For example, Margulies and Karanth (2018) demonstrated that an increase in global prices for coffee had cascading effects on human–carnivore conflict because it affected grazing policies, including the number of cattle owned and places grazed, which in turn altered predatory encounters with carnivores. In this way, labeling a practice as both social and ecological in nature provides a language to enhance understanding of local human–wildlife conflict.

The nonhierarchical relationship between subject and object in practice theory further aligns with the study of human–wildlife interactions. Practice theory and human–wildlife conflict both recognize the importance of nonhuman actors (animals) and objects (environmental features) in shaping social and environmental processes. In the context of human–wildlife interactions, vegetation and landscape topography (objects) affect wildlife actions (e.g., movement paths) and thus affect the practices (the generalized habits, e.g., daily and seasonal foraging movements) of wildlife and their impacts on vegetation. For example, drought-induced reduction of vegetation cover and prey availability can lead to higher livestock depredation by carnivores (Schiess-Meier et al. 2007). Anthropogenic objects also positively and negatively influence wildlife practices. In Scandinavia, wolves increased their proximity to humans by traveling on human-built roads in search of prey, but at the same time, they developed behavior to avoid direct contact with humans (Zimmermann et al. 2014). The spectrum of influence that human-made objects, such as roads, have on wildlife demonstrates how objects can shape systems.

A notable departure in our social–ecological practice theory compared to the original practice theory is who has agency. Giddens and Bourdieu decouple intention from agency, defining it as the capacity for action rather than mere intent (Giddens 1984), capable of adjustment to the future without predetermined plans (Bourdieu 1990). While Bourdieu excludes agency from nonhumans, we employ these definitions to advocate for nonhuman agency. Drawing on Giddens and Bourdieu, we conceptualize agency as the capacity to reorient present and future states through contextualizing the past (Kok et al. 2021). Through this definition of agency, animals become subjects within practices. This concept aligns social–ecological practice theory to have a “more-than-human” perspective, which considers how humans and nonhumans share across the interrelated dimensions of social, historical, ecological, psychological, political, and cultural experiences (van Dooren et al. 2016). While the degree of agency of nonhumans relative to humans may vary, “more-than-human” perspectives make evident the impact that nonhumans may have on social systems and other nonhumans, natural substances, and technical objects (Haraway 2008; Bennett 2010; Arcari 2019; Maller and Strengers 2019), including primates (Parathian et al. 2018), fish (Roe 2006), and plants (Hitchings and Jones 2004). Our social–ecological practice theory approach joins in placing humans and animals as equal participants in human–animal relations, recognizing it’s importance and benefit in doing so. In the realm of conservation efforts and human–wildlife conflict mitigation, representing both human and animals as subjects provides a stronger understanding of these interactions.

Human–wildlife conflict events happen at the level of individuals, but it is also important to study and understand how wider groups of people and institutions affect conflict (Lischka et al. 2018). Practice theory is well suited for this—it can be scaled across individuals’ experiences and worldviews, as well as those of groups, organizations, and institutions—including development organizations, government, etc. (Orlikowski 2002). For example, the practices a community has toward wildlife are shaped by the stories and feelings of the individuals and households living within an area. The practices of individuals herding cattle in a wildlife region in two different areas could be similar or different depending on the influences of their community, broader cultural norms, past experiences, and other local practices. This approach emphasizes how social practices are constructed through discourse and embedded with power dynamics and agency of nonhuman animals through their own practices (Watson 2016). Practice theory can help understand the basis for realized or perceived conflict as driven by local variations across both ecological and social processes involving the actions of individuals, groups, and institutions.

Human–lion interactions in Botswana: A case study with social–ecological practice theory

Social and ecological features on the landscape are intricately intertwined, which is essential to fully understand HWC, and this can be illuminated by social–ecological practice theory. We emphasize this point by examining a case study of human–wildlife interactions in Botswana.

Background

The Central Boteti West sub-district of Makgadikgadi or CT8 (Fig. 1) has been identified as an important corridor for lions (Cushman et al. 2018). It links CKGR through to MPNP and the rest of the Kavango–Zambezi Transfrontier Area (KAZA)—a conservation area that spans across Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. In recent history, CT8 was an important migration route for herbivores—most famously wildebeest—which was cut off in the 1950s when the Kuke fence and other veterinary fences were built to mitigate the spread of foot-and-mouth disease between Cape buffalo and cattle (Table 1).

Table 1.

Timeline of selected events identified by social–ecological practice theory which shape predation in Makgadikgadi today

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| Early 1800s | Tswana kingdoms comprise the area that is now known as Botswana |

| 1885 | The area now known as Botswana becomes a British Protectorate |

| 1905 | The commercialization of cattle begins with the export of beef South African mining towns |

| 1954 | Kuke fence is erected to prevent foot-and-mouth disease |

| 1961 | The Central Kalahari Game Reserve is established |

| 1966 | Botswana independence |

| 1970 | Makgadikgadi Pans National Park is established |

| 1975 | Tribal Grazing Lands Policy |

| 2004 | Boteti fence erected |

| 2008 | Boteti River began to flow again |

| 2014 | Hunting moratorium |

| 2019 | Boteti fence removed |

| 2021 | Boteti fence partially re-instated |

The Boteti region is possibly the origin site of modern humans (Chan et al. 2019). As long ago as the early Holocene, the nutrient-rich grasses in the dried ancestral Lake Makgadikgadi made it an ideal place for both humans and wildlife to inhabit (McLeod 2019). When domesticated animals were introduced to Botswana about 2200 years ago, these grasses became seasonally important for livestock herding (Hillbom 2008).

Today, the landscape between CKGR and MPNP contains seven villages with 1400 individual cattleposts—outposts where livestock are tended by herders—raising an estimated 6800 head of cattle (Statistics Botswana 2015). Because of grazing, plowing, and water requirements, cattleposts are spread across the region rather than solely concentrated around villages. The Tribal Grazing Lands Policy of 1975 divided the region into three separate zones—Commercial, Tribal and Unused—in order to mitigate grazing pressure by large, commercial ranching (Gupta 2013) (Table 1). The policy established private farms and farm syndicates on the western side of CT8 and granted them rights to drill wells to allow for communal tribal grazing, on the basis that they were 20 km from a village or the river. In accordance with Botswana land rights, cattleposts can be erected anywhere and do not need the permission of the Land Board or other governmental bodies. However, cattleposts cannot drill a well without a certificate, and these are issued only if the designated location is at least 5 km away from another well point. As a result, many cattleposts are found within walking distance of the Boteti River. But a 30-year interruption in river flow, due to low rainfall, led residents to hand-dig wells in the riverbed and use portable pumps to draw water up from the water table.

This is an important region for wildlife because of its unique habitat structure. One of the two zebra migrations in Botswana extends from the Okavango Delta to MPNP, driven by access to the grasslands and natural salt pans. Zebra and wildebeest optimize daily energetics by remaining close to water and high-quality grasses, which shape their daily foraging movements and activity cycle (Bartlam-Brooks et al. 2013). Zebras follow the rains in November/December to the Makgadikgadi pans in the eastern side of the park (Bartlam-Brooks et al. 2013); then in March, they migrate to the western side of the park to sustain themselves with water before returning to the Delta (Bartlam-Brooks et al. 2013). The most recent data suggest there are 35 +/− 5 lions in Makgadikgadi (Ngaka 2015) and roughly 150–300 lions in northern CKGR. The lion prides in Makgadikgadi feed primarily on zebra during the migration and venture outside the park and supplementarily feed on livestock when the zebra are no longer in the area (Hemson 2003). The revival of consistent seasonal rainfalls since 2008 has increased water access for local residents and their livestock, as well as supported a greater abundance of wildlife.

Before Botswana became a British Protectorate in 1885, most cattle belonged to the dikgosi—chiefs—and their families (Hjort 2010). The dikgosi also owned the land and made tribal decisions regarding grazing, cattle, and land use (Hillbom 2014). In exchange for herding labor, the dikgosi would then loan their livestock to other families and would give them access to some of the calves, meat, and milk (Peters 1984).

Commercialization of cattle raising in Botswana began in 1905 when the British administration started shipping beef to expanding mining towns in South Africa and later to the United Kingdom and other countries during the World Wars (Darkoh and Mbaiwa 2002). By the time Botswana gained its independence in 1966, beef comprised 85% of its total export earnings (Mphinyane and Omphile 2016).

Practices

The regional practices of cattle rearing influence how individuals run and work on their cattleposts. Livestock husbandry in CT8 is inherently social and based on historical and cultural practices; it requires cooperation and the formation of strong social groups. It is rare for anyone to manage a cattlepost alone; and those who do require help from nearby posts when it is time to brand, vaccinate, sell, or kill a cow. Those who do not live on their cattleposts full time frequent them on weekends and may plan to retire there. Most workers on a cattlepost call themselves herders but based on their day-to-day responsibilities their role is more akin to farm hands or farm workers. Their work includes kraal (livestock pen) upkeep, goat, sheep, and chicken rearing, milking, assisting with breeding, firewood collection, cooking, general maintenance, and assisting nearby cattleposts (Gupta 2013). Herders are also constantly visiting one another, either to make a social call or to track wandering cows. When people are not working on the cattlepost they might walk, ride, or drive into town for provisions and stop along the way to chat with neighbors. The spacing of cattleposts is such that it allows strong social networks to be established, which ensures that most herders are aware of predation events, even if the exact details of when and what was killed are not always conveyed.

The region’s practices around cattle rearing are further shaped by subsistence farmers and more wealthy ranchers in conjunction with the role cattle play in Botswana’s culture, identity, and economic security. Importantly, a man with livestock demonstrates that he can provide for his family. Owning cattle is a mark of status dating back to precolonial times; a form of capital that dominates across multiple fields. The use of cattle for ceremonial and community gatherings perpetuates what cattle symbolize in habitus and as capital; this includes bridewealth, loans, and funerals, and hides for traditional dance attire (Gupta 2013; Ministry of Agriculture Development and Food Security 2018). Cattle are capital which represent a stash of savings to be accessed only in times of need (Gupta 2013), given the cultural restriction on converting livestock to cash (Ferguson 1985; Gupta 2013). Thus, subsistence cattle owners’ interests do not always align with regional or global markets—or even with their neighbor. Seen as an investment rather than a consumable commodity, a farmer sells cattle only for a specific purpose (e.g., to cover funeral costs or school fees; Jefferis 2007), not for profit. Thus, the practices of cattle rearing are shaped both by wider cultural practices (social structures) and by individual needs.

The practices of cattle rearing are shaped not only by cultural norms but also by the individual and group practices of the cattle, and also by cattlepost infrastructure. Variations in how the kraal was built and its placement can cause cattle to stray far from their cattlepost. When there is lots of rain, cattle can remain outside of the safety of their kraals and supplement their water needs from puddles and dew on the grass. Depending on where the kraal is built, rainfall may accumulate as standing water in the kraal, forcing cattle to sleep standing up. Consequently, some cattle will refuse to return to the safety of the kraal at night during the rainy season and instead sleep in the bush. During the dry season, cattle may not return to the kraal every night to optimize energetics by remaining in proximity to water and forage (Matsoga 2021). In both seasons, cattle sometimes roam over large distances to sustain themselves so that they are too far from the cattlepost to return each day. However, many cows return daily to their kraals when they give birth to nurse their young. Calves generally remain near the kraal because they are not released from it until later in the day and they also are provided with drinking water. Often, adult cattle must find alternative sources of water because some boreholes draw highly saline water and cattle must be supplemented with nonsaline water every month or so, or boreholes break down from elephant damage or from general use. When this happens, cattle must be herded to the next nearest water source. During these events, the cattle’s capital and habitus—perception of where the highest quality forage is—is disrupted and their practices change. Cattle must remain farther away from their cattlepost for longer than normal and may get lost in their search for food and water. When cattle are lost, they are more prone to predation, drought, disease, and theft.

Cattle husbandry practices are also influenced by predation events. Cattle predation at any given cattlepost is more often a punctuated event than a constant threat. Between 2007 and 2019, cattle holders within CT8 reported an aggregate average 19% chance that they would lose one cow each year (Matsoga 2021). But predation varies across the landscape, occurring more frequently at cattleposts closer to either CKGR or MPNP and more frequently on cattleposts with higher numbers of cattle. Thus, the aggregate average is not reflective of the wide range of depredation rates (0.08–4.33 cows per year) experienced across all of the cattleposts (Matsoga 2021).

Such variation in depredation differentially affects other aspects of the daily practices on the cattlepost. There are often very few herders working at a single cattlepost, sometimes only two men tending 150 heads of cattle. Unlike areas in East Africa where the position of a herder is revered, herders in Botswana are undervalued and paid minimum wage by the cattle owners (~ USD 100 per month). Because predation events are stochastic and are associated with the practices of individual lions, it is difficult for herders to monitor each cow daily and tend to all of their other responsibilities. The habitus, and practices, around cattle management, thus do not always involve mitigation strategies for depredation. Because of the scarcity of resources in the arid climate, it is often more optimal for farmers to release their livestock to fend for themselves against drought than to actively herd them.

Predation events are broadly influenced by lion demography (Hemson 2003), as well as seasonally dictated by prey migration (Ngaka 2015), and temporally dictated by human activity (Valeix et al. 2012). In Makgadikgadi, male lions are more likely than females to raid livestock. Across KAZA, dispersing males who leave their natal pride are less risk-averse than other lions and thus are more likely to be the primary contributor to human–lion conflict (Elliot et al. 2014). In Makgadikgadi, those that do raid livestock (both male and female) do not shift their home ranges to follow the zebra and wildebeest migration back to the Okavango Delta in the dry season (May–October). Thus, cattle-raiding lions hunt the migratory herds in the wet season (with a 98% +/− 3% home range overlap with the wildebeest herd) but not in the dry season (0% overlap) (Hemson 2003). Lionesses that do not raid cattle maintain a mean 80% (+/− 13%) overlap with wildebeest and zebra in the dry and wet season, and hold home ranges in the center of MPNP (Hemson 2003).

The temporal activity of lions is influenced by human activity. Between 06:00 h–20:00 h, lions demonstrate strong avoidance of the cattleposts (Valeix et al. 2012). Those that raid livestock make most of their attempts between 22:00 h–4:00 h when roughly 80% of cattle are at the cattleposts (Hemson 2003). The nocturnal predation of cattle allow lions to avoid the energetic and reproductive costs of following the zebra migration, as well as the threat of encountering and engaging in conflict with other territorial prides in the Okavango Delta (Valeix et al. 2012). Avoiding these costs seemingly outweighs the potential costs of conflicts with cattlepost owners (Valeix et al. 2012).

Predation events impact cattle rearing practices. There are cultural and indirect losses of capital of losing a cow beyond direct economic costs (Barua et al. 2013; Dickman and Hazzah 2016). These losses of capital can include spending more time, energy, and money on protecting livestock or cultural losses such as the impacts on traditional practices in which livestock play a role (Barua et al. 2013; Dickman and Hazzah 2016). The government offers compensation for cattle that are killed by large predators, including lions, but this does not cover the costs the farmer must incur from filing the report, waiting for the paperwork to process, and replacing the cattle (Barua et al. 2013). There are also numerous restrictions regarding compensation, including proof the cattle were killed by the predator. This proof requires a Department of Wildlife and National Parks (DWNP) officer to visit the scene of the attack, which is often delayed due to a lack of vehicles and personnel. Lion practices, and perceived and actual threats of predation, can intensify feelings and practices toward predators.

While predation causes animosity, it appears that the costs of adapting herding practices to mitigate predation are still higher than any accrued costs (Hemson et al. 2009). In addition, people see hunting to eliminate carnivores as a cheaper and more direct way to stop predation than relying on government compensation. Cattle owners believe that the government should take more responsibility in preventing predation in the first place, by maintaining the predator–proof fences along the boundaries of the national parks. People also overwhelmingly see objects (features of the landscape such as fences and rivers) as effective mitigation strategies, even when these objects do not in reality always dissuade predators.

Fences and rivers play an integral role in social–ecological practices. The fence and the river have been shaped and are shaped by the practices of both lions and people in the region. A predator–proof fence was built in 2004 along the western side of the MPNP in direct response to high levels of livestock predation (Table 1). When originally built, the fence zig-zagged across the dry Boteti riverbed and physically restrained lions from leaving the park and entering the community lands. Lion practices in the region were altered, leading to a decrease in livestock kill reports from 25.3 (+/− 2.9) to 11.2 (+/− 3.4) reports per month. As a result, almost all herders (95.6%) reported that human–lion conflict had decreased (Ngaka et al. 2018; Ngaka 2015). Two years after the fence was built, most people (65.8%) continued to perceive that the level of human–lion conflict was low even though the number of livestock kill reports had rebounded to 27.4 (+/− 3.4) per month (Ngaka 2015; Ngaka et al. 2018). The rise in kill reports was due to the Boteti River beginning to flow again in 2008, thereby drawing wildlife, cattle, and people to the river, destroying the predator–proof fence in the process (Kesch et al. 2015; Ngaka et al. 2018). In 2018, plans were drafted to re-delineate the fence boundaries so that most of it would be on the western side of the river to hold off the wildlife, with the added promise from the government to drill water access points for cattle and people on its eastern side. The old fence was removed in 2019 but the new fence reconstruction was delayed. As of December 2022, the replacement fence still had not been completed, which has increased residents’ frustrations with how the government addresses human–wildlife conflict.

The Boteti River is also an object which has impacted ecological and social subsystems. The severity of the arid climate’s impact on humans, livestock, and wildlife is cyclical and persistent. The river only flows seasonally, but humans and elephants have modified the riverbed to dig water holes when it is dry, and both people and wildlife use each other’s water points to access water. During the river’s dry period, DWNP installed several boreholes for wildlife along the riverbed. This was partially intended to deter wildlife, including lions, from seeking water in the community lands and also to sustain wildlife populations. Thus, access to water from the Boteti River is a function of actions by both humans and wildlife, as well as the rains in the region.

A social–ecological landscape is context- and location-specific. Predation and perceptions of human–wildlife conflict differ between communities. Matsoga (2021) found that youths’ (age 18–35 years old) perceptions of human–lion conflict and its drivers differed between a village along the Boteti River in CT8 and another area in Botswana, the Chobe Enclave (Matsoga 2021). Questionnaires and focus groups, which examined generational and gendered perceptions of human–lion conflict, revealed that a person’s age had different effects on perceptions of conflict between the two areas (Matsoga 2021). Chobe youth perceived natural factors, such as prey availability, to be the main attributes contributing to conflict, whereas Boteti youth, Boteti elders, and Chobe elders all perceived governance as having a stronger impact (Matsoga 2021).

Discussion

Using the Makgadikgadi region as a case study, we outlined how using practice theory, and the study of capital, social fields, and habitus provides us with a stronger understanding of human–wildlife conflict. We examined the interconnected practices of cattle rearing, human–wildlife interactions, and cattle predation by discussing the subjects—the herders, owners, cattle, and lions—in Makgadikgadi. We showed that practices change over time and space, and through the changing of resources. We discussed how different social–ecological objects, including the river system, fences, vegetation, and water points, contribute to creating human–wildlife conflict. Throughout, we demonstrated how people and wildlife have their own practices, and the study of both is required to understand human–wildlife interactions in the Makgadikgadi.

Bourdieu’s Practice theory offers the foundation for developing a social–ecological practice theory that when applied to the Makgadikgadi region of Botswana can increase understanding of human–wildlife conflict, particularly between lions and their interactions with different human communities. Giddens's emphasis on studying the mundane daily routines points to the importance of studying the behaviors and adaptations of both lions and humans in this conflict. The practices of lions and people are dynamic, constantly in flux with one another, with objects, and with their surrounding environment. They change as their social fields and capital change—when there are seasonal differences in resource access or landscape modifications. Lions, as agents seeking resources or capital, adapt to the changing availability of wild prey based on the relative attraction of different practices, access to resources, or power relations involved in seasonal migrations. The habits and routines of cattle are also shaped by their own capital, which includes access to water and grazing pastures. Cattle become familiar with specific areas for grazing and know which boreholes provide fresh water. However, when boreholes break down or grazing pastures become depleted, cattle must develop new practices and adapt their habitus accordingly to find alternative resources. This can lead to higher depredation. For human communities, their capital is a combination of monetary wealth and cattle. The differences between the Chobe and the Boteti communities' perceptions of conflict demonstrate how practices are influenced by their community, broader cultural norms and demographics, and other local practices and are constantly being transformed. As seasons change and zebras migrate from the region, lions impact this human capital by preying on livestock, then community members develop actions and practices aimed at protecting their assets while minimizing further losses. If these lions are forcibly removed, either relocated or shot, then a new pride will come into the area and the entire process will repeat itself.

Objects across this landscape are hybrids of nature and culture. The Boteti River, the predator–proof fence, and the boreholes are nature–culture objects that all modify and have been modified by humans, livestock, and wildlife. These objects also drive individual practices on the landscape through the access to river water, the inhibition of wildlife movement across the landscape, and the quality of water from the boreholes. The predator–proof fence was not only a physical barrier for lions, but it also changed people's attitudes toward human–carnivore conflict even years later after depredation reports rebound. The removal of the predator–proof fence which separated the MPNP from the Boteti communities led both adults and youths to claim that it was the most important variable in human–lion conflict. On the other hand, the Chobe Enclave has never had a predator fence, so it never influenced their perspectives of human–lion conflict in the region. Chobe and Boteti elders and Boteti youths believed the leading cause of livestock predation was the recent moratorium on wildlife hunting (Matsoga 2021). However, the hunting ban has since been lifted and thus practices may have changed since the original survey. Practice theory highlights the role that objects like fences play in human–wildlife conflict.

Using practice theory enables us to understand how historical and political processes shape individual behaviors and routines (Gadsden et al. 2023; Sutherland et al. 2023). HWC in the region primarily originated from the British commercialization of the cattle industry in Botswana, driven by the implementation of a colonial tax. Cattle commercialization emerged as a viable option due to its compatibility with the geography and arid climate. The privatization of communal grazing can be traced back to the Tribal Grazing Lands Policy of 1975 (TGLP), a World Bank-sponsored initiative aimed at expanding the cattle industry and addressing land degradation in Botswana (Darkoh and Mbaiwa 2002). However, the TGLP inadvertently led to overgrazing, exacerbated socio-economic inequalities and adversely impacted both tribal lands and small-scale ranchers (Darkoh and Mbaiwa 2002; Gupta 2013). The TGLP and the commercialization of cattle resulted in the erection of fences across the country, and thus directly shaped the practices of lions today in Makgadikgadi. The TGLP and cattle industry also have shaped the habitus around cattle as well as cattle rearing practices. Utilizing practice theory allows us to grasp the significant societal structures and power structures molding individual behaviors and routines of people, cattle, and lions—pivotal for a comprehensive understanding and potential resolution of complex challenges such as human–wildlife conflict.

Our definition of agency threads practice theory with a “more-than-human” perspective. It facilitates the study of both human and wildlife practices, acknowledging them as equal participants with central roles in HWC. Lions, alongside humans, exhibit agency by having the capacity to orient to the future through historical context. Through this lens, we also see how social, historical, ecological, psychological, political, and cultural experiences of lions shape their practices. This encompasses actions like supplementing food resources with cattle when the zebra migration has left the region and temporally avoiding human presence during activity peaks. This also includes lions shifting their practices in response to changes in this physical landscape, such as fences and rivers. While Bourdieu's omission of nonhuman agency is acknowledged, our application of his and Giddens' definition of agency, as others have also done (e.g., Kok et al. 2021), enables us to attribute agency to nonhumans and taking a “more-than-human” perspective. In our allocation of agency to lions, we are provided with a much more nuanced understanding of human–wildlife interactions in Makgadikgadi.

Our use of Practice theory contributes to our understanding of HWC but also demonstrates some clear limitations. It can scale up from the individual to larger collectives and institutions, proving a versatility that is needed to study something as complex as human–wildlife conflict. Practice theory can draw on both ecological and anthropological theory to uncover nuanced drivers of human–wildlife conflict events. Social–ecological practice theory can help to identify appropriate management strategies benefitting humans, wildlife, and their shared environment (Maller 2021). However, such research takes time, money, and a breadth and depth in social and ecological understanding. The Makgadikgadi region, and our highlighted case study, have benefited from having a long history of social and ecological research that has produced a breadth and depth of available data. This type of study can illuminate social–ecological intricacies and complexity, but it is not readily undertaken in general conservation approaches.

Conclusion

In summary, the application of practice theory to the study of human–wildlife conflict provides a valuable framework for understanding the complex dynamics between humans, wildlife, and their shared environment. Drawing on the insights of Pierre Bourdieu and other practice theorists, we can examine the everyday practices of individuals that exist in a human–wildlife interaction, and their interactions within the social field, thereby uncovering the underlying power dynamics, social norms, and structures that shape conflict. Understanding the human–wildlife conflict through the lens of social–ecological practice theory allows us to appreciate the multifaceted factors at play, including the influence of changing cultural norms, access to resources, power relations, and the adaptive behaviors of people and of predators in response to changes in their fields. Acknowledging agency within nonhumans also provides a “more-than-human” perspective which provides additional nuance to understanding HWC. Social–ecological practice theory can inform more effective and sustainable conservation strategies for the coexistence of humans and predators in shared landscapes.

The study of human–wildlife interactions requires a comprehensive understanding that considers landscape-scale patterns driven by local ecological and social mechanisms. The use of practice theory, in combination with ecological theories and “more-than-human” perspectives, can provide this. The discipline of anthropology offers valuable insights into the relationship between human actions, socio-political structures, and nonhuman elements, providing a more holistic view. Practice theory acknowledges the intricate connections between individual participants in human–wildlife events and the wider socio-political drivers and power dynamics that shape these interactions. By adopting a social–ecological perspective that integrates the disciplines of anthropology and ecology, we can enhance our understanding of human–wildlife conflict and contribute to more effective conservation strategies that promote coexistence between humans and wildlife.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank and acknowledge Dr. Gaseitsiwe Masunga from the University of Botswana’s Okavango Research Institute, Mr. Khumiso Rathipana and Mr. Dikatholo Kedikilwe from Round River Botswana Trust and Round River Conservation Studies for their insights and support over the many years to make this manuscript possible. We also would like to acknowledge the comments and insightful suggestions of our two anonymous reviewers.

Biographies

Kaggie Orrick

is a Doctoral Candidate at the Yale University School of the Environment.

Michael Dove

is a Margaret K. Musser Professor of Social Ecology at the Yale School of the Environment; Professor of Anthropology at Yale University; Curator of Anthropology Peabody Museum; Co-Coordinator of the Joint Yale University School of the Environment/Anthropology Doctoral Program; and Chair Council on Southeast Asian Studies.

Oswald J. Schmitz

is a Oastler Professor of Population and Community Ecology, in the Yale University School of the Environment.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Arcari P. ‘Dynamic’ non-human animals in theories of practice: Views from the subaltern. In: Maller C, Strengers Y, editors. Social practices and dynamic non-humans: Nature, materials and technologies. Cham: Springer; 2019. pp. 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramaniam KN, Marty PR, Samartino S, Sobrino A, Gill T, Ismail M, Saha R, Beisner BA, et al. Impact of individual demographic and social factors on human–wildlife interactions: A comparative study of three macaque species. Scientific Reports. 2020;10:21991. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78881-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban NC, Mills M, Tam J, Hicks CC, Klain S, Stoeckl N, Bottrill MC, Levine J, et al. A social–ecological approach to conservation planning: Embedding social considerations. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2013;11:194–202. doi: 10.1890/110205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlam-Brooks HLA, Beck PSA, Bohrer G, Harris S. In search of greener pastures: Using Satellite images to predict the effects of environmental change on zebra migration. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences. 2013;118:1427–1437. doi: 10.1002/jgrg.20096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barua M, Bhagwat SA, Jadhav S. The hidden dimensions of human–wildlife conflict: Health impacts, opportunity and transaction costs. Biological Conservation. 2013;157:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2012.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J. Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Durham: Duke University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett NJ, Roth R, Klain SC, Chan K, Christie P, Clark DA, Cullman G, Curran D, et al. Conservation social science: Understanding and integrating human dimensions to improve conservation. Biological Conservation. 2017;205:93–108. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Binder CR, Hinkel J, Bots PWG, Pahl-Wostl C. Comparison of frameworks for analyzing social–ecological systems. Ecology and Society. 2013;18:19. doi: 10.5751/ES-05551-180426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bleicher SS. The landscape of fear conceptual framework: Definition and review of current applications and misuses. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3772. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. Esquisse d’une Théorie de La Pratique. Paris: Librairie Droz; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. The logic of practice. Redwood City: Stanford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Chan EKF, Timmermann A, Baldi BF, Moore AE, Lyons RJ, Lee S-S, Kalsbeek AMF, Petersen DC, et al. Human origins in a southern African Palaeo-Wetland and first migrations. Nature. 2019;575:185–189. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1714-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman SA, Elliot NB, Bauer D, Kesch K, Bahaa-el-din L, Bothwell H, Flyman M, Mtare G, MacDonald DW, Loveridge AJ. Prioritizing core areas, corridors and conflict hotspots for lion conservation in southern Africa. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0196213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darkoh MBK, Mbaiwa JE. Globalisation and the livestock industry in Botswana. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography. 2002;23:149–166. doi: 10.1111/1467-9493.00123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman AJ. Complexities of conflict: The importance of considering social factors for effectively resolving human–wildlife conflict: Social factors affecting human–wildlife conflict resolution. Animal Conservation. 2010;13:458–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1795.2010.00368.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman AJ, Hazzah L. Money, myths and man-eaters: Complexities of human–wildlife conflict. In: Angelici FM, editor. Problematic wildlife. Cham: Springer; 2016. pp. 339–356. [Google Scholar]

- Dressel S, Ericsson G, Sandström C. Mapping social–ecological systems to understand the challenges underlying wildlife management. Environmental Science and Policy. 2018;84:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2018.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot NB, Cushman SA, MacDonald DW, Loveridge AJ. The devil is in the dispersers: Predictions of landscape connectivity change with demography. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2014;51:1169–1178. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman MS, Orlikowski WJ. Theorizing practice and practicing theory. Organization Science. 2011;22:1240–1253. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1100.0612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson J. The bovine mystique: Power, property and livestock in rural Lesotho. Man. 1985;20:647. doi: 10.2307/2802755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher R, Toncheva S. The political economy of human–wildlife conflict and coexistence. Biological Conservation. 2021;260:109216. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsden GI, Golden N, Harris NC. Place-based bias in environmental scholarship derived from social–ecological landscapes of fear. BioScience. 2023;73:23–35. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biac095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A. Central problems in social theory: Action, structure, and contradiction in social analysis. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A. Elements of the theory of structuration. New York: Routledge; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta C. A genealogy of conservation in Botswana. PULA: Botswana Journal of African Studies. 2013;27:23. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway D. When species meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hemson G. The ecology and conservation of lions: Human–wildlife conflict in semi-arid Botswana. Oxford: University of Oxford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hemson G, Maclennan S, Mills G, Johnson P, MacDonald D. Community, lions, livestock and money: A spatial and social analysis of attitudes to wildlife and the conservation value of tourism in a human–carnivore conflict in Botswana. Biological Conservation. 2009;142:2718–2725. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2009.06.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hillbom E. Diamonds or development? A structural assessment of Botswana’s forty years of success. The Journal of Modern African Studies. 2008 doi: 10.1017/S0022278X08003194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hillbom E. Cattle, diamonds and institutions: Main drivers of Botswana’s economic development, 1850 to present. Journal of International Development. 2014;26:155–176. doi: 10.1002/jid.2957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchings R, Jones V. Living with plants and the exploration of botanical encounter within human geographic research practice. Ethics, Place and Environment. 2004;7:3–18. doi: 10.1080/1366879042000264741. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hjort J. Pre-colonial culture, post-colonial economic success? The Tswana and the African Economic Miracle: AFRICAN ECONOMIC MIRACLE. The Economic History Review. 2010;63:688–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0289.2009.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferis, K. 2007. Price responsiveness of cattle supply in Botswana. Policy Briefing Paper. Gaborone: Southern Africa Global Competitiveness Hub. http://www.econsult.co.bw/tempex/priceresponsivenessofcattlesupplyinbotswana.pdf.

- Kesch MK, Bauer DT, Loveridge AJ. Break on through to the other side: The effectiveness of game fencing to mitigate human–wildlife conflict. African Journal of Wildlife Research. 2015;45:76–87. doi: 10.3957/056.045.0109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kok KPW, Loeber AMC, Grin J. Politics of complexity: Conceptualizing agency, power and powering in the transitional dynamics of complex adaptive systems. Research Policy. 2021;50:104183. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2020.104183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lischka SA, Teel TL, Johnson HE, Reed SE, Breck S, Carlos AD, Crooks KR. A conceptual model for the integration of social and ecological information to understand human–wildlife interactions. Biological Conservation. 2018;225:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2018.06.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano J, Olszańska A, Morales-Reyes Z, Castro AA, Malo AF, Moleón M, Sánchez-Zapata JA, Cortés-Avizanda A, et al. Human–carnivore relations: A systematic review. Biological Conservation. 2019;237:480–492. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maller C. Turning things around: A discussion of values, practices, and action in the context of social–ecological change. People and Nature. 2021 doi: 10.1002/pan3.10272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maller C, Strengers Y, editors. Social practices and dynamic non-humans: Nature, materials and technologies. Cham: Springer; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Margulies JD, Karanth KK. The production of human–wildlife conflict: A political animal geography of encounter. Geoforum. 2018;95:153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsoga, T.B. 2021. Social and environmental drivers of human–lion conflict in the Boteti and Chobe Enclave regions, northern Botswana. Masters of Philosophy in Natural Resources Management. Maun: University of Botswana, Okavango Research Institute.

- McLeod G. Makgadikgadi Pans. New York: Penguin Random House South Africa; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture Development and Food Security. 2018. Botswana Agricultural Census Report 2015. Statistics Botswana. ISBN 978-99968-418-3-5.

- Mphinyane NW, Omphile UJ. Influence of policy on the transformation of range management from traditional management: A perspective of history of range management in Botswana. Botswana Journal of Agriculture and Applied Sciences. 2016;11:20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Naughton-Treves L, Treves A. Socio-ecological factors shaping local support for wildlife: Crop-raiding by elephants and other wildlife in Africa. In: Woodroffe R, Thirgood S, Rabinowitz A, editors. People and wildlife. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. pp. 252–277. [Google Scholar]

- Ngaka, K. 2015. Dynamics of human–lion conflict in and around Makgadikgadi Pans National Park. Master of Philosophy. Maun: University of Botswana.

- Ngaka K, Rutina L, Hemson G, Maude G. The influence of the Makgadikgadi fence and the re-flowing of the Boteti River on the temporal distribution of human/lion conflict. PULA: Botswana Journal of African Studies. 2018;32:12. [Google Scholar]

- Orlikowski WJ. Knowing in practice: Enacting a collective capability in distributed organizing. Organization Science. 2002;13:249–273. doi: 10.1287/orsc.13.3.249.2776. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parathian HE, McLennan MR, Hill CM, Frazão-Moreira A, Hockings KJ. Breaking through disciplinary barriers: Human–wildlife interactions and multispecies ethnography. International Journal of Primatology. 2018;39:749–775. doi: 10.1007/s10764-018-0027-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters PE. Struggles over water, struggles over meaning: Cattle, water and the state in Botswana. Africa. 1984;54:29–49. doi: 10.2307/1160738. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pettorelli N, Coulson T, Durant SM, Gaillard J-M. Predation, individual variability and vertebrate population dynamics. Oecologia. 2011;167:305–314. doi: 10.1007/s00442-011-2069-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pooley S, Barua M, Beinart W, Dickman A, Holmes G, Lorimer J, Loveridge AJ, Macdonald DW, et al. An interdisciplinary review of current and future approaches to improving human–predator relations. Conservation Biology. 2017;31:513–523. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe EJ. Things becoming food and the embodied, material practices of an organic food consumer. Sociologia Ruralis. 2006;46:104–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.2006.00402.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schiess-Meier M, Ramsauer S, Gabanapelo T, König B. Livestock predation—Insights from problem animal control registers in Botswana. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 2007;71:1267–1274. doi: 10.2193/2006-177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sjölander-Lindqvist A, Johansson M, Sandström C. Individual and collective responses to large carnivore management: The roles of trust, representation, knowledge spheres, communication and leadership. Wildlife Biology. 2015;21:175–185. doi: 10.2981/wlb.00065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Botswana . Population Census Atlas 2011: Botswana. Gaborone: Statistics Botswana; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland IJ, Copes-Gerbitz K, Parrott L, Rhemtulla JM. Dynamics in the landscape ecology of institutions: Lags, legacies, and feedbacks drive path-dependency of forest landscapes in British Columbia, Canada 1858–2020. Landscape Ecology. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s10980-023-01721-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valeix M, Hemson G, Loveridge AJ, Mills G, MacDonald DW. Behavioural adjustments of a large carnivore to access secondary prey in a human-dominated landscape: Wild prey, livestock and lion ecology. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2012;49:73–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2011.02099.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Dooren T, Kirksey E, Münster U. Multispecies studies: Cultivating arts of attentiveness. Environmental Humanities. 2016;8:1–23. doi: 10.1215/22011919-3527695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, M. 2016. Placing power in practice theory. In: The nexus of practices, 181–194. New York: Routledge.

- Whittington R. Greatness takes practice: On practice theory’s relevance to ‘Great Strategy’. Strategy Science. 2018;3:343–351. doi: 10.1287/stsc.2017.0040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson CE, McInturff A, Miller JRB, Yovovich V, Gaynor KM, Calhoun K, Karandikar H, et al. An ecological framework for contextualizing carnivore–livestock conflict. Conservation Biology. 2019 doi: 10.1111/cobi.13469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittemyer G, Northrup JM, Bastille-Rousseau G. Behavioural valuation of landscapes using movement data. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society b: Biological Sciences. 2019;374:20180046. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2018.0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann B, Nelson L, Wabakken P, Sand H, Liberg O. Behavioral responses of wolves to roads: Scale-dependent ambivalence. Behavioral Ecology. 2014;25:1353–1364. doi: 10.1093/beheco/aru134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]