Abstract

Background

Despite advances in cancer and venous thromboembolism (VTE) management, the epidemiology of cancer-associated thrombosis management over time remains unclear.

Objectives

We analyzed data from the RIETE (Registro Informatizado de la Enfermedad Trombo Embólica) registry spanning 2001 to 2020 to investigate temporal trends in clinical characteristics and treatments for cancer-associated thrombosis.

Methods

Using multivariable survival regression, we examined temporal trends in risk-adjusted rates of symptomatic VTE recurrences, major bleeding, and death within 30 days after incident VTE.

Results

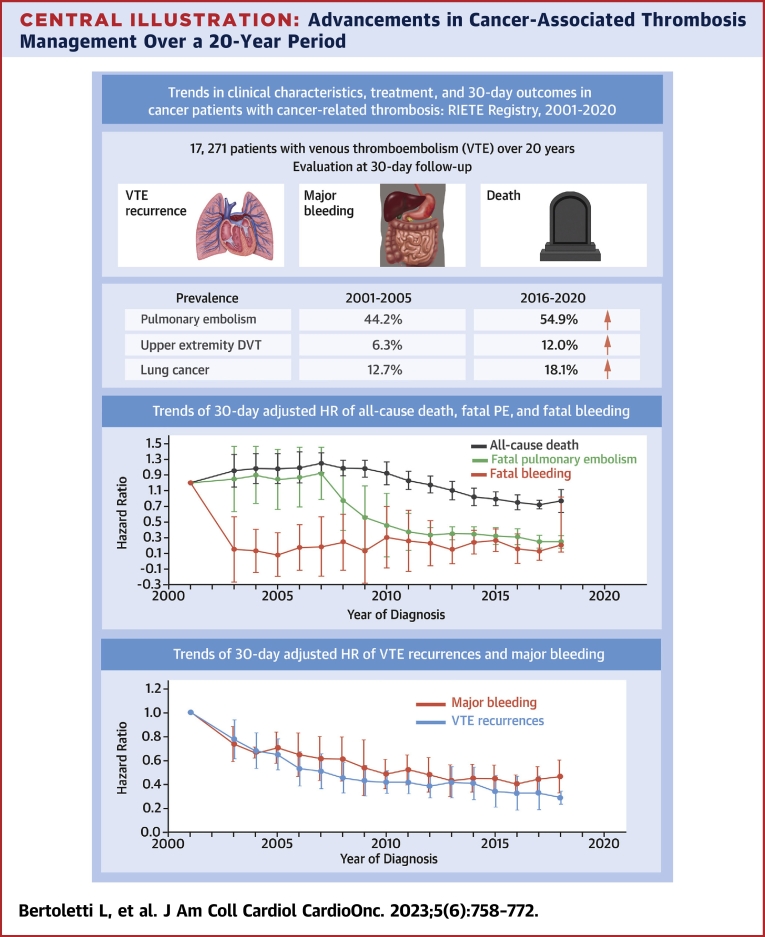

Among the 17,271 patients with cancer-associated thrombosis, there was a progressive increase in patients presenting with pulmonary embolism (from 44% in 2001-2005 to 55% in 2016-2020; P < 0.001 for trend), lung (from 12.7% to 18.1%; P < 0.001) or pancreatic cancer (from 3.8% to 5.6%; P = 0.003), and utilization of immunotherapy (from 0% to 7.4%; P < 0.001). Conversely, there was a decline in patients with prostate cancer (from 11.7% to 6.6%; P < 0.001) or carcinoma of unknown origin (from 3.5% to 0.7%; P < 0.001). At the 30-day follow-up, a reduction was observed in the proportion of patients experiencing symptomatic VTE recurrences (from 3.1% to 1.1%; P < 0.001), major bleeding (from 3.1% to 2.2%; P = 0.004), and death (from 11.9% to 8.4%; P < 0.001). Multivariable analyses revealed a decreased risk over time for VTE recurrence (adjusted subdistribution HR [asHR]: 0.94 per year; 95% CI: 0.92-0.98), major bleeding (asHR: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.96-0.99), and death (aHR: 0.97; 95% CI: 0.96-0.98).

Conclusions

In this multicenter study of cancer patients with VTE, there was a decline in thrombotic, hemorrhagic, and fatal events from 2001 to 2020. (Registro Informatizado de la Enfermedad Trombo Embólica [RIETE]; NCT02832245)

Key Words: anticoagulant, bleeding, cancer, survival, thrombosis

Central Illustration

Cancer significantly increases the risk of thrombosis, including venous thromboembolism (VTE), defined by deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). Overall, about 1 of 5 VTE events occurs in patients with cancer.1 In clinical practice, diagnosing VTE in patients with cancer encounters delays because of the symptoms attributable to VTE not being consistently recognized.2 Furthermore, the presence of cancer-associated VTE poses challenges because it is associated with an increased risk of both VTE recurrence and bleeding compared with VTE patients without cancer.3 VTE in patients with cancer adds to the burden of disease and contributes to mortality and long-term morbidity.4

In recent decades, significant advances have been made in both cancer and VTE management. Cancer patients have experienced improved quality of life and survival because of new therapies.5, 6, 7, 8 In parallel, awareness surrounding cancer-associated VTE has grown as well as an increased knowledge of its epidemiology and risk factors. Also, the advent of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) has introduced new possibilities for treating cancer-associated VTE. DOACs have undergone comparison with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) in several head-to-head trials,9, 10, 11, 12 leading to updates in most international guidelines.13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Despite these advancements in cancer and VTE management, trends in the clinical characteristics, management, and VTE-related outcomes of patients with cancer presenting with acute VTE in clinical practice have not been well-defined. Although data from a multicenter multinational registry have indicated improved short-term outcomes in individuals with VTE,18,19 these trends have remained unexplored in patients with cancer-associated VTE despite the potential temporal changes in cancer care and VTE care.

The RIETE (Registro Informatizado de la Enfermedad Trombo Embólica) registry, an ongoing multicenter registry, comprises consecutive patients with objectively confirmed acute VTE.20 Data from this registry have previously been used to evaluate outcomes after VTE, such as the frequency of recurrent VTE, major bleeding, or mortality, along with the risk factors associated with these outcomes. The aims of the current study are to compare the 30-day rates of symptomatic VTE recurrences, major bleeding events, and death in cancer patients with acute VTE over the last 20 years as well as to explore any changes in their clinical characteristics and treatments.

Methods

Brief summary of the RIETE registry

The RIETE registry is an ongoing, multicenter compilation of consecutive patients with objectively confirmed acute VTE (NCT02832245). The rationale and methodology of RIETE have been previously described.20 Briefly, it includes consecutive patients with objectively confirmed acute VTE. For each patient included, baseline characteristics, such as comorbidities and concomitant drugs, as well as diagnostic information, VTE risk factors, biological results, and initial management (including anticoagulant therapy and modalities, use of inferior vena cava filters, and so on) are prospectively recorded. Every patient is followed for a minimum of 3 months unless they die. During the follow-up period, information on therapeutic management approaches (drugs, compression therapy, surgery, and so on) and outcomes (death, recurrent VTE, bleeding, arterial events, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, post-thrombotic syndrome, and so on) is collected. S & H Medical is the coordinating center and oversees data monitoring, audits, and queries.

Since its establishment in Spain in 2001, the RIETE registry has gained participation from many countries. At present, more than 180 centers across 20 countries contribute to the RIETE registry, which includes more than 100,000 patients with acute VTE. Having prospective clinical data from a multitude of centers across several countries has enabled the RIETE registry to harness the advantages of prospective cohorts, characterized by individual inclusion of well-phenotyped patients, combined with the strength of administrative databases, providing access to a large number of patients.20

Inclusion criteria

Consecutive cancer patients with acute, symptomatic lower or upper limb DVT, and/or PE confirmed by objective tests (compression ultrasonography for suspected DVT; helical computed tomography [CT] scan, ventilation-perfusion lung scintigraphy, or conventional angiography for suspected PE) were eligible for inclusion. Patients were not included in the registry if they were currently participating in a blinded therapeutic clinical trial (a situation that did not occur in the setting of cancer-associated thrombosis during the study period). All patients (or their relatives) provided written or oral informed consent for participation in the registry in accordance with local ethics committee requirements.

For this study, only patients with active cancer at baseline were considered. We defined active cancer when the diagnosis of malignancy was made within 6 months before the index VTE event or in patients with metastatic disease or receiving active therapy (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonal therapy, or supportive or palliative care) at the time of VTE.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes considered in this study were the development of symptomatic, objectively confirmed VTE recurrences; major bleeding events; or death within the first 30 days after VTE diagnosis. The secondary outcomes included fatal PE and fatal bleeding. During each visit, any signs or symptoms suggestive of VTE recurrences or bleeding complications were noted. Each episode of clinically suspected recurrent DVT or PE was investigated through repeat compression ultrasonography, lung scintigraphy, helical CT scan, or pulmonary angiography as deemed appropriate. Recurrent DVT was defined as a new noncompressible vein segment or an increase in the vein diameter by at least 4 mm compared with the last available measurement on venous ultrasonography. Recurrent PE was defined as a new ventilation-perfusion mismatch on a lung scan or a new intraluminal filling defect on a spiral CT of the chest. Fatal PE, in the absence of autopsy, was defined as any death appearing within 10 days after PE diagnosis without any alternative cause of death. Bleeding events were classified as major if they were overt and required a transfusion of 2 or more units of blood or if they occurred in the retroperitoneum, pericardium, spinal column, or intracranially or were fatal.20 Fatal bleeding was defined as any death occurring <10 days after a major bleeding episode without any alternative cause of death.

Other data elements

The following parameters were recorded when the qualifying episode of VTE was diagnosed: baseline characteristics, including demographic characteristics, other VTE risk factors, and comorbidities; signs and symptoms of VTE; cancer site, presence of metastases, and type of oncologic therapy (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, hormonal therapy, or combinations thereof); anticoagulant therapy administered upon VTE diagnosis (drug, dose, start date, and discontinuation date for each drug); concomitant drugs; and outcomes within the first 30 days. Immobilized patients were defined as nonsurgical patients who had been bedridden (ie, total bed rest with or without bathroom privileges) for 4 or more days in the 2 months before the index VTE. Surgical patients were defined as those who had undergone a surgical procedure in the 2 months before the VTE event. Recent major bleeding was considered if it occurred within 30 days before the index VTE. Anemia was defined as hemoglobin levels <13 g/dL for men and <12 g/dL for women. Creatinine clearance (CrCl) levels were measured according to the Cockcroft-Gault formula.20

Treatment and follow-up

Patients received management in accordance with the clinical practices of each participating hospital, with no central standardization of treatment. The type, dose, and duration of anticoagulant therapy were determined by the treating clinicians and recorded by the study staff. After VTE diagnosis, patients were monitored for at least 3 months or until death.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as counts expressed as percentages for categoric variables and as mean ± SEM of the mean for continuous variables.

To evaluate changes in baseline characteristics over time, we used linear regression for continuous variables and logistic regression for categoric variables. For simplicity of representation, baseline characteristics are grouped in 5-year intervals (2001-2005, 2006-2010, 2011-2015, and 2016-2020). However, linear regression (or logistic regression where appropriate) tested for trends for each individual year.

To assess the 30-day death rates over time, we performed Cox regression analysis for the overall cohort. The 30-day rates of VTE recurrences, major bleeding, fatal PE, and fatal bleeding were calculated separately, assuming death as a competing risk using Fine-Gray regression models. Non-PE death was considered the competing risk for VTE recurrence, and nonbleeding death was the competing risk for bleeding events. Our subdistribution hazards regression models adjusted for the following variables: sex, age, body weight, initial VTE presentation (PE vs isolated DVT), chronic heart or lung disease, recent major bleeding, prior VTE, blood tests at baseline (including anemia, leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, and CrCl levels), cancer site, presence of metastases, oncologic therapy, long-term anticoagulant therapy with LMWH, DOACs or vitamin K antagonists (VKAs), concomitant therapy with corticosteroids or antiplatelet drugs, and the country of enrollment. The selection of these potential confounders was based on consensus among the steering committee of the study, and they were chosen before conducting the analyses. The annual trends were calculated by assessing the statistical significance of the coefficient in the regression models (logistic, linear, Cox, or Fine-Gray regression model) for the year variable (calendar year) using 2001 as the reference period. Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS for Windows Release (version 22, IBM Corp). For data sharing inquiries, contact the corresponding author via direct e-mail.

Results

Trend analyses for baseline characteristics and VTE therapy

As of December 2020, the RIETE registry enrolled 17,271 patients with active cancer and symptomatic VTE. Initially, the number of participating hospitals in RIETE increased from 129 centers with 3,072 patients in the first period from 2001 to 2005 to a relatively stable number of approximately 180 centers with over 4,000 patients in the subsequent 5-year periods (Table 1). Among these patients, 8,168 (47%) were women, with a mean age of 67 ± 0.2 years. A total of 8,813 (51%) presented initially as PE (with or without associated DVT), and 9,350 (54%) had metastases. The most common types of cancer included lung (2,820 cases), colorectal (2,378 cases), breast (2,243 cases), prostate (1,468 cases), and hematologic cancer (1,296 cases) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Trends in Baseline Characteristics in 17,271 Patients With Active Cancer and Acute VTE

| 2001-2005 (n = 3,068) | 2006-2010 (n = 4,266) | 2011-2015 (n = 4,864) | 2016-2020 (n = 5,073) | P Value for Trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Female | 1,373 (44.8) | 1,946 (45.6) | 2,366 (48.6) | 2,483 (48.9) | <0.01 |

| Age, y | 67.6 ± 0.2 | 67.4 ± 0.2 | 67.3 ± 0.2 | 67.2 ± 0.2 | 0.12 |

| Body weight, kg | 70.9 ± 0.2 | 71.7 ± 0.2 | 73.1 ± 0.2 | 73.6 ± 0.2 | <0.01 |

| Inpatients | 893 (29.5) | 1,288 (30.5) | 1,378 (29.5) | 1,474 (30.3) | 0.97 |

| Initial VTE presentation | |||||

| Symptomatic PE | 1,356 (44.2) | 2,207 (51.7) | 2,467 (50.7) | 2,783 (54.9) | <0.01 |

| In patients with PE | |||||

| SBP levels <90 mm Hg | 61 (2.0) | 92 (2.2) | 107 (2.2) | 97 (1.9) | 0.91 |

| Heart rate >100 beats/min | 433 (14.1) | 701 (16.4) | 831 (17.1) | 860 (17.0) | <0.01 |

| Saturated O2 levels <90% | 318 (10.4) | 379 (8.9) | 346 (7.1) | 258 (5.1) | <0.01 |

| sPESI >0 points | 1,731 (56.4) | 2,414 (56.6) | 2,664 (54.8) | 2,982 (58.8) | 0.04 |

| Isolated DVT | 1,712 (55.8) | 2,059 (48.3) | 2,397 (49.3) | 2,290 (45.1) | <0.01 |

| Lower limb, proximal | 1,333 (43.4) | 1,492 (35.0) | 1,654 (34.0) | 1,409 (27.8) | <0.01 |

| Lower limb, distal | 162 (5.3) | 212 (5.0) | 224 (4.6) | 284 (5.6) | 0.52 |

| Upper extremity DVT | 192 (6.3) | 304 (7.1) | 508 (10.4) | 609 (12.0) | <0.01 |

| Additional risk factors | |||||

| Recent surgery | 492 (16.0) | 615 (14.4) | 691 (14.2) | 670 (13.2) | <0.01 |

| Recent immobility ≥4 d | 571 (18.6) | 762 (17.9) | 720 (14.8) | 750 (14.8) | <0.01 |

| Estrogen use | 87 (2.8) | 175 (4.1) | 406 (8.3) | 425 (8.4) | <0.01 |

| Pregnancy or postpartum | 1 (0.03) | 5 (0.1) | 6 (0.1) | 6 (0.1) | 0.20 |

| None of the above | 1,937 (63.1) | 2,755 (64.6) | 3,155 (64.9) | 3,343 (65.9) | 0.01 |

| Prior VTE | 437 (14.2) | 474 (11.1) | 553 (11.4) | 538 (10.6) | <0.01 |

| Underlying conditions | |||||

| Chronic heart failure | 122 (4.0) | 212 (5.0) | 292 (6.0) | 239 (4.7) | 0.19 |

| Chronic lung disease | 316 (10.3) | 462 (10.8) | 623 (12.8) | 537 (10.6) | 0.65 |

| Recent major bleeding | 95 (3.1) | 128 (3.0) | 151 (3.1) | 142 (2.8) | 0.53 |

| Blood tests | |||||

| Anemia | 1,775 (57.9) | 2,614 (61.3) | 3,085 (63.4) | 3,033 (59.8) | 0.03 |

| Leukocyte count >11,000/μL | 947 (30.9) | 1,208 (28.3) | 1,351 (27.8) | 1,374 (27.1) | <0.01 |

| Platelet count <100,000/μL | 168 (5.5) | 227 (5.3) | 329 (6.8) | 277 (5.5) | 0.32 |

| CrCl levels <60 mL/min | 1,438 (46.9) | 1,723 (40.4) | 1,460 (30.0) | 1,378 (27.2) | <0.01 |

| Concomitant drugs | |||||

| Corticosteroids | 384 (12.5) | 516 (12.1) | 794 (16.3) | 856 (16.9) | <0.01 |

| Antiplatelets | 228 (7.4) | 447 (10.5) | 764 (15.7) | 676 (13.3) | <0.01 |

| Countries | |||||

| Spain | 3,007 (98.0) | 3,083 (73.3) | 2,935 (60.3) | 3,328 (65.6) | <0.01 |

| Rest of Europe | 50 (1.6) | 840 (19.7) | 1,089 (22.4) | 1,327 (26.2) | <0.01 |

| America | 11 (0.4) | 43 (1.0) | 199 (4.1) | 175 (3.4) | <0.01 |

| Asia | 0 | 287 (6.7) | 638 (13.1) | 188 (3.7) | <0.01 |

Values are n (%) or mean ± SEM. P values for trend are obtained from linear or logistic regression models.

CrCl = creatinine clearance; DVT = deep vein thrombosis; PE = pulmonary embolism; SBP = systolic blood pressure; sPESI = simplified Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index; VTE = venous thromboembolism.

Table 2.

Cancer Characteristics

| 2001-2005 (n = 3,068) | 2006-2010 (n = 4,266) | 2011-2015 (n = 4,864) | 2016-2020 (n = 5,073) | P Value for Trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time from cancer diagnosis, mo | 4 (0-18) | 4 (0-19) | 4 (0-19) | 4 (0-24) | <0.01 |

| Metastases | |||||

| Yes | 1,529 (49.8) | 2,302 (54.0) | 2,664 (54.8) | 2,855 (56.3) | <0.01 |

| Sites of cancer | |||||

| Lung | 390 (12.7) | 679 (15.9) | 835 (17.2) | 916 (18.1) | <0.01 |

| Colorectal | 417 (13.6) | 635 (14.9) | 693 (14.2) | 633 (12.5) | 0.01 |

| Breast | 366 (11.9) | 499 (11.7) | 623 (12.8) | 755 (14.9) | <0.01 |

| Prostate | 358 (11.7) | 402 (9.4) | 372 (7.6) | 336 (6.6) | <0.01 |

| Hematologic | 206 (6.7) | 327 (7.7) | 410 (8.4) | 353 (7.0) | 0.53 |

| Bladder | 207 (6.7) | 235 (5.5) | 221 (4.5) | 238 (4.7) | <0.01 |

| Brain | 172 (5.6) | 194 (4.5) | 164 (3.4) | 170 (3.4) | 0.59 |

| Stomach | 136 (4.4) | 185 (4.3) | 184 (3.8) | 179 (3.5) | 0.02 |

| Uterine | 128 (4.2) | 174 (4.1) | 178 (3.7) | 218 (4.3) | 0.99 |

| Pancreas | 118 (3.8) | 193 (4.5) | 273 (5.6) | 285 (5.6) | <0.01 |

| Ovary | 101 (3.3) | 142 (3.3) | 167 (3.4) | 224 (4.4) | <0.01 |

| Kidney | 71 (2.3) | 94 (2.2) | 100 (2.1) | 133 (2.6) | 0.32 |

| Unknown origin | 107 (3.5) | 110 (2.6) | 81 (1.7) | 37 (0.7) | <0.01 |

| Oropharynx | 43 (1.4) | 81 (1.9) | 76 (1.6) | 89 (1.8) | 0.59 |

| Biliary tract | 42 (1.4) | 44 (1.0) | 86 (1.8) | 48 (0.9) | 0.53 |

| Melanoma | 13 (0.4) | 42 (1.0) | 44 (0.9) | 58 (1.1) | 0.95 |

| Liver | 19 (0.6) | 29 (0.7) | 46 (0.9) | 42 (0.8) | 0.20 |

| Esophagus | 28 (0.9) | 46 (1.1) | 58 (1.2) | 47 (0.9) | 0.66 |

| Other sites | 146 (4.8) | 155 (3.6) | 253 (5.2) | 312 (6.2) | <0.01 |

| Therapy for cancer | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 1,552 (51.3) | 2,164 (52.2) | 2,324 (52.2) | 2,370 (52.1) | 0.79 |

| Radiotherapy | 309 (10.2) | 496 (12.0) | 709 (16.7) | 693 (16.1) | <0.01 |

| Chemo- and radiotherapy | 189 (6.3) | 311 (7.5) | 471 (11.2) | 421 (9.9) | <0.01 |

| Hormonal therapy | 315 (34.2) | 334 (23.4) | 569 (14.0) | 588 (13.9) | <0.01 |

| Immunotherapy | 0 | 2 (2.8) | 13 (2.7) | 243 (7.4) | <0.01 |

| None of the above | 1,212 (39.5) | 1,713 (40.2) | 1,916 (39.4) | 1,935 (38.1) | 0.22 |

Values are median (Q1-Q3) or n (%). P values for trend are obtained from linear or logistic regression models.

Over the 20-year study period, there was a progressive increase in patients initially presenting with PE (from 44.2% in 2001-2005 to 54.9% in 2016-2020; P < 0.001 for trend) or with upper extremity DVT (from 6.3% in 2001-2005 to 12.0% in 2016-2020; P < 0.001 for trend). In contrast, the proportion of patients with proximal DVT of the lower limbs decreased (Supplemental Figure 1). Additionally, the proportion of women increased significantly during the study period (from 44.8% initially to 48.9% in the last period; P < 0.001 for trend), along with an increase in estrogen use (from 2.8% initially to 8.4% in the last period; P < 0.001 for trend). Furthermore, we observed an increase in patients receiving corticosteroids (from 12.5% to 16.9%; P < 0.001 for trend) or antiplatelet drugs (from 7.4% to 13.3%; P < 0.001 for trend) and a progressive decrease in patients with CrCl levels <60 mL/min at baseline (from 46.9% to 27.2%; P < 0.001 for trend) (Table 1).

There was also a progressive increase in patients with metastases (from 49.8% to 56.3%; P < 0.001 for trend) (Table 2). Concerning cancer sites, we observed a progressive increase in patients with lung cancer (from 12.7% to 18.1%; P < 0.001 for trend) or pancreatic cancer (from 3.8% to 5.6%; P = 0.003 for trend). In contrast, there was a progressive decrease in patients with prostate cancer (from 11.7% to 6.6%; P < 0.001 for trend), brain cancer (from 5.6% to 3.4%; P < 0.001 for trend), or carcinoma of unknown origin (from 3.5% to 0.7%; P < 0.001 for trend). There was also a progressive increase in patients receiving radiotherapy (from 10.2% to 16.1%; P < 0.001 for trend) or immunotherapy (from 0% to 7.4%; P < 0.001 for trend) and a decrease in patients on hormonal therapy (from 34.2% to 13.9%; P < 0.001 for trend).

Regarding the initial therapy of VTE, there was a progressive decrease in the use of LMWH (from 92.0% to 87.2%; P < 0.001 for trend) or unfractionated heparin (from 6.8% to 3.5%; P < 0.001 for trend) along with an increase in the use of DOACs (from 0% to 2.9%; P < 0.001 for trend) or pulmonary embolectomy (from 0.3% to 0.7%; P = 0.014 for trend) (Table 3, Figure 1). After the first week of therapy, there was a progressive increase in the use of LMWH (from 49.2% to 68.5%; P < 0.001 for trend) or DOACs (from 0% to 12.3%; P < 0.001 for trend) and a progressive decrease in the use of VKAs (from 43.4% to 9.0%; P < 0.001 for trend) (Table 3, Figure 2).

Table 3.

Venous Thromboembolism Treatment Strategies

| 2001-2005 (n = 3,068) | 2006-2010 (n = 4,266) | 2011-2015 (n = 4,864) | 2016-2020 (n = 5,073) | P Value for Trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial therapy | |||||

| LMWH | 2,823 (92.0) | 3,881 (91.0) | 4,409 (90.6) | 4,424 (87.2) | <0.01 |

| Unfractionated heparin | 208 (6.8) | 252 (5.9) | 237 (4.9) | 178 (3.5) | <0.01 |

| DOACs | 0 | 0 | 35 (0.7) | 149 (2.9) | <0.01 |

| Rivaroxaban | 0 | 0 | 34 (0.7) | 97 (1.9) | <0.01 |

| Apixaban | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.02) | 42 (0.8) | <0.01 |

| Fondaparinux | 0 | 68 (1.6) | 85 (1.7) | 67 (1.3) | <0.01 |

| Thrombolytic drugs | 19 (0.6) | 29 (0.7) | 35 (0.7) | 32 (0.6) | 0.66 |

| Inferior vena cava filter | 124 (4.0) | 232 (5.4) | 255 (5.2) | 235 (4.6) | 0.46 |

| Pulmonary embolectomy | 9 (0.3) | 18 (0.4) | 25 (0.6) | 33 (0.7) | 0.01 |

| Mechanical thrombolysis | 0 | 0 | 5 (0.3) | 26 (0.6) | 0.04 |

| Long-term therapy | |||||

| LMWH | 1,510 (49.2) | 2,690 (63.1) | 3,525 (72.5) | 3,476 (68.5) | <0.01 |

| Vitamin K antagonists | 1,332 (43.4) | 1,144 (26.8) | 823 (16.9) | 455 (9.0) | <0.01 |

| DOACs | 0 | 1 (0.02) | 94 (1.9) | 623 (12.3) | <0.01 |

| Rivaroxaban | 0 | 1 (0.02) | 82 (1.8) | 249 (5.3) | <0.01 |

| Apixaban | 0 | 0 | 7 (0.2) | 216 (4.6) | <0.01 |

| Dabigatran | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.04) | 20 (0.4) | <0.01 |

| Edoxaban | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.06) | 138 (2.9) | <0.01 |

| Fondaparinux | 0 | 66 (1.5) | 71 (1.5) | 56 (1.1) | <0.01 |

Values are n or n (%). P values for trend are obtained from logistic regression models; proportions are crude rates.

DOAC = direct oral anticoagulant; LMWH = low molecular weight heparin.

Figure 1.

Trends in the Use of Anticoagulant Drugs for Initial Venous Thromboembolism Therapy

Low molecular weight heparins (LMWHs) remain the most commonly used anticoagulants for the initial treatment of cancer-associated thrombosis, with a recent increase in the use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) since 2016. UFH = unfractionated heparin; VTE = venous thromboembolism.

Figure 2.

Trends in Anticoagulant Drug Use Beyond the First Week of Venous Thromboembolism Therapy

Beyond the first week of therapy, LMWHs have progressively replaced vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) for cancer-associated thrombosis maintenance therapy. Recently, there has been an increasing adoption of DOACs, especially since 2018. Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Evaluating crude rates during the first 30 days of therapy, we found that 319 patients (1.8%) developed VTE recurrences (recurrent PE, 177; DVT, 145), 414 (2.4%) experienced major bleeding (gastrointestinal, 182; hematoma, 51; intracranial, 46; genitourinary, 45), and 1,760 (10.2%) died (Table 4, Supplemental Table 1 for results according to cancer sites). Of these, 235 (13.4%) died of PE (the index PE, 206; recurrent PE, 29) and 95 (5.4%) died of bleeding. There was a progressive decrease in patients with VTE recurrences (from 3.1% to 1.1%; P < 0.001 for trend), major bleeding (from 3.1% to 2.2%; P = 0.004 for trend), all-cause death (from 11.9% to 8.4%; P < 0.001 for trend), fatal PE (from 2.5% to 0.6%; P < 0.001 for trend), and fatal bleeding (from 1.1% to 0.3%; P < 0.001 for trend) (Figures 3 and 4). The decrease in most of these outcomes was similar in patients initially presenting with PE or with isolated DVT. The 30-day mortality rate decreased from 14.5% to 10.2% (P < 0.001 for trend) in patients with PE and from 2.9% to 2.2% (P < 0.001 for trend) in those with isolated DVT (Table 4).

Table 4.

Thirty-Day Outcomes

| 2001-2005 | 2006-2010 | 2011-2015 | 2016-2020 | P Trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 3,068 | 4,266 | 4,864 | 5,073 | |

| PE recurrences | 50 (1.6) | 48 (1.1) | 44 (0.9) | 35 (0.7) | <0.01 |

| DVT recurrences | 45 (1.5) | 34 (0.8) | 43 (0.9) | 23 (0.5) | <0.01 |

| VTE recurrences | 95 (3.1) | 81 (1.9) | 86 (1.8) | 57 (1.1) | <0.01 |

| Major bleeding | 95 (3.1) | 114 (2.7) | 92 (1.9) | 113 (2.2) | <0.01 |

| Gastrointestinal | 43 (1.4) | 47 (1.1) | 48 (1.0) | 44 (0.9) | 0.01 |

| Intracranial | 11 (0.4) | 9 (0.2) | 6 (0.1) | 20 (0.4) | 0.59 |

| Genitourinary | 15 (0.5) | 16 (0.4) | 6 (0.1) | 8 (0.2) | 0.01 |

| Hematoma | 14 (0.5) | 15 (0.4) | 9 (0.2) | 13 (0.3) | 0.06 |

| Retroperitoneal | 1 (0.0) | 9 (0.2) | 9 (0.2) | 11 (0.2) | 0.20 |

| Overall death | 364 (11.9) | 514 (12.0) | 454 (9.3) | 428 (8.4) | <0.01 |

| Fatal PE | 77 (2.5) | 87 (2.0) | 41 (0.8) | 30 (0.6) | <0.01 |

| Fatal initial PE | 67 (2.2) | 76 (1.8) | 34 (0.7) | 29 (0.6) | <0.01 |

| Fatal recurrent PE | 10 (0.3) | 11 (0.3) | 7 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | <0.01 |

| Fatal bleeding | 33 (1.1) | 30 (0.7) | 17 (0.3) | 15 (0.3) | <0.01 |

| PE patients | 1,356 | 2,207 | 2,467 | 2,783 | |

| PE recurrences | 35 (2.6) | 25 (1.1) | 20 (0.8) | 15 (0.5) | <0.01 |

| DVT recurrences | 16 (1.2) | 10 (0.5) | 18 (0.7) | 10 (0.4) | <0.01 |

| VTE recurrences | 51 (3.8) | 35 (1.6) | 38 (1.5) | 25 (0.9) | <0.01 |

| Major bleeding | 46 (3.4) | 60 (2.7) | 59 (2.4) | 62 (2.2) | <0.01 |

| Overall death | 197 (14.5) | 327 (14.8) | 283 (11.5) | 283 (10.2) | <0.01 |

| Fatal PE | 74 (5.5) | 82 (3.7) | 39 (1.6) | 29 (1.0) | <0.01 |

| Fatal initial PE | 67 (4.9) | 76 (3.4) | 34 (1.4) | 29 (1.0) | <0.01 |

| Fatal recurrent PE | 7 (0.5) | 6 (0.3) | 5 (0.2) | 0 | <0.01 |

| Fatal bleeding | 10 (0.7) | 14 (0.6) | 12 (0.5) | 9 (0.3) | <0.01 |

| DVT patients | 1,712 | 2,059 | 2,397 | 2,290 | |

| PE recurrences | 15 (0.9) | 23 (1.1) | 24 (1.0) | 20 (0.9) | 0.79 |

| DVT recurrences | 29 (1.7) | 24 (1.2) | 25 (1.0) | 13 (0.6) | <0.01 |

| VTE recurrences | 44 (2.6) | 46 (2.2) | 48 (2.0) | 32 (1.4) | <0.01 |

| Major bleeding | 49 (2.9) | 54 (2.6) | 33 (1.4) | 51 (2.2) | <0.01 |

| Overall death | 167 (9.8) | 187 (9.1) | 171 (7.1) | 145 (6.3) | <0.01 |

| Fatal PE | 3 (0.2) | 5 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.04) | <0.01 |

| Fatal bleeding | 23 (1.3) | 16 (0.8) | 5 (0.2) | 6 (0.3) | <0.01 |

Values are n or n (%). Proportions are crude rates not adjusted for competing risks. P values for trend are obtained from Cox regression for overall death and separate competing risk Fine-Gray regression models for all other outcomes.

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Thirty-Day Unadjusted Crude Rates of Outcomes Over a 20-Year Period

The unadjusted curves suggest a decline in death rates resulting from pulmonary embolism (PE) or hemorrhage over the last 20 years. The results are based on crude rates not considering competing risk.

Figure 4.

Thirty-Day Unadjusted Crude Rates of Symptomatic VTE Recurrences and Major Bleeding Over a 20-Year Period

The unadjusted curves suggest a decrease in the rates of symptomatic cancer-associated thrombosis recurrence and bleeding events over the last 20 years. The results are based on crude rates not considering competing risk. VTE = venous thromboembolism.

Trends analysis for clinical outcomes

Fourteen patients (0.08%) had missing values for anemia, 18 (0.1%) for leukocytosis, 17 (0.1%) for thrombocytopenia, and 1 patient (0.005%) had no information on body weight; these cases were excluded from the multivariable analysis.

In the multivariable analyses, we observed a progressive decrease in the risk of VTE recurrences (adjusted subdistribution HR [asHR]: 0.94 per year; 95% CI: 0.92-0.96), major bleeding (asHR: 0.98 per year; 95% CI: 0.96-0.99), all-cause death (asHR: 0.97 per year; 95% CI: 0.96-0.98), fatal PE (asHR: 0.89 per year; 95% CI: 0.87-0.92), and fatal bleeding (asHR: 0.91 per year; 95% CI: 0.88-0.95) (Table 5, Figures 5 and 6). Similarly, after adjusting for temporal trends in patient characteristics around the time of VTE diagnosis, from 2001 to 2005 to 2016 to 2020, the HRs (or subdistribution HRs for competing risk analysis) for VTE recurrences decreased by 0.42 (95% CI: 0.28-0.64), major bleeding by 0.66 (95% CI: 0.45-0.97), all-cause death by 0.60 (95% CI: 0.48-0.74), fatal PE by 0.19 (95% CI: 0.08-0.46), and fatal bleeding by 0.37 (95% CI: 0.20-0.68).

Table 5.

Multivariable HRs for Main Clinical Outcomes at 30 Days

| Recurrent VTE | Major Bleeding | All-Cause Death | Fatal PE | Fatal Bleeding | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 319 | 414 | 1,760 | 235 | 95 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Age >70 y | 0.51 (0.38-0.67) | 1.01 (0.80-1.28) | 1.06 (0.96-1.18) | 1.12 (0.83-1.52) | 1.47 (0.92-2.34) |

| Initial VTE presentation | |||||

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.80 (0.64-1.01) | 1.17 (0.96-1.44) | 1.49 (1.35-1.64) | 20.5 (11.2-37.6) | 0.93 (0.61-1.40) |

| Blood tests | |||||

| Anemia | 1.02 (0.81-1.29) | 1.96 (1.56-2.46) | 1.63 (1.47-1.81) | 1.26 (0.96-1.66) | 2.28 (1.40-3.71) |

| WBC >11,000/μL | 1.82 (1.44-2.30) | 1.63 (1.33-2.01) | 2.59 (2.35-2.86) | 2.18 (1.68-2.83) | 1.85 (1.20-2.87) |

| Platelet count <100,000/μL | 1.34 (0.86-2.09) | 1.75 (1.24-2.48) | 2.55 (2.19-2.96) | 2.88 (1.91-4.35) | 2.09 (1.10-4.00) |

| CrCl levels <60 mL/min | 0.84 (0.64-1.10) | 1.58 (1.26-1.99) | 1.76 (1.58-1.96) | 1.85 (1.38-2.46) | 1.63 (1.03-2.58) |

| Concomitant drugs | |||||

| Corticosteroids | 0.86 (0.62-1.19) | 1.46 (1.13-1.89) | 1.64 (1.46-1.84) | 1.87 (1.37-2.56) | 1.75 (1.04-2.95) |

| Cancer characteristics | |||||

| With metastases | 1.28 (1.01-1.63) | 1.35 (1.09-1.66) | 2.85 (2.53-3.21) | 2.61 (1.91-3.58) | 1.73 (1.09-2.73) |

| Site of cancer | |||||

| Breast | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Gastrointestinal | 1.60 (0.99-2.59) | 1.38 (0.94-2.03) | 1.75 (1.42-2.15) | 1.03 (0.64-1.66) | 2.56 (0.91-7.21) |

| Genitourinary | 1.50 (0.93-2.44) | 1.48 (1.01-2.16) | 1.22 (0.98-1.51) | 1.07 (0.66-1.72) | 2.06 (0.72-5.91) |

| Lung | 2.30 (1.42-3.73) | 0.99 (0.64-1.53) | 1.97 (1.60-2.44) | 0.97 (0.59-1.60) | 2.15 (0.68-6.81) |

| Other sites | 1.55 (0.95-2.55) | 1.29 (0.86-1.94) | 1.60 (1.29-1.99) | 1.10 (0.67-1.81) | 2.88 (0.99-8.36) |

| Cancer therapy | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 0.69 (0.54-0.87) | 0.62 (0.50-0.76) | 0.75 (0.67-0.83) | 0.82 (0.62-1.09) | 0.77 (0.49-1.20) |

| Influence of time | |||||

| Per year | 0.94 (0.92-0.96) | 0.98 (0.96-0.99) | 0.97 (0.96-0.98) | 0.89 (0.87-0.92) | 0.91 (0.88-0.95) |

Values are n or adjusted HR (or subdistribution HR for competing risk analysis) (95% CI). Multivariable time-to-event regression models at 30 days for the respective outcomes of recurrent VTE, major bleeding, all-cause death, fatal PE, and fatal bleeding. Models were adjusted for sex, age, body weight, VTE presentation (PE vs DVT), chronic heart or lung disease, recent major bleeding, prior VTE, anemia, leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, CrCl, cancer site, metastases, oncologic therapy, anticoagulant type, antiplatelet therapy, corticosteroids, and country. This table is the global results of the 5 multivariable analyses, one for each clinical outcome, with adjusted outcomes models using HR (or asHR) as the effect measure for each outcome.

asHR = adjusted subdistribution HR; WBC = white blood cell; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Figure 5.

Trends in 30-Day Fatal Events Over a 20-Year Period

The analysis of trends of 30-day HR (or subdistribution HR for competing risk analysis) (adjusted by moving average) shows a decrease in the HR of death by bleeding or pulmonary embolism (PE) and all-cause death. The risk of death caused by PE exhibits a significant decline beginning in 2007. Trends of 30-day HR (or subdistribution HR for competing risk analysis) adjusted using a moving average are depicted. We applied a smoothing technique by using a fifth-order moving average, with the SD serving as the descriptive measure for the values used in calculating these moving averages.

Figure 6.

Trends in VTE Recurrences and Bleeding Over a 20-Year Period

Trends in the 30-day HR (or sub-HR for competing risk analysis) for venous thromboembolism (VTE) recurrence and major bleeding are presented, with adjustments made using a moving average. The analysis was adjusted for potential confounding factors, showing a decrease in the HR (or sub-HR for competing risk analysis) for recurrent VTE and major bleeding over the last 20 years. However, no increase in bleeding events has been observed during recent years of analysis.

Discussion

Our study, which analyzed a large cohort of consecutive patients with active cancer and symptomatic VTE, has identified several significant changes over time that suggest advances in the management of patients with cancer-associated thrombosis (Central Illustration). We observed a progressive increase in patients initially presenting with PE or upper extremity DVT and a decrease in patients presenting with lower limb DVT. Furthermore, there was an increase in patients receiving radiotherapy or immunotherapy and a decrease in those prescribed hormonal therapy (with the exception of estrogen use). Concerning the treatment of VTE, the progressive increase in DOAC use has been matched by a decrease in VKA use. However, the most clinically relevant findings pertain to the progressive decrease in patients experiencing VTE recurrences, major bleeding events, and all-cause death as well as death caused by bleeding or PE during the first 30 days of therapy. These findings remain robust even after thorough multivariable adjustment. This progressive improvement in 30-day outcomes remains consistent among patients initially presenting with PE or isolated DVT.

Central Illustration.

Advancements in Cancer-Associated Thrombosis Management Over a 20-Year Period

This illustration portrays the trends in the 30-day adjusted HR (or subdistribution HR for competing risk analysis) of symptomatic venous thromboembolism (VTE) recurrences and major bleeding over a 20-year time period. The analysis was adjusted for potential confounding factors, showing a decrease in the HR (or subdistribution HR for competing risk analysis) for the recurrence of cancer-associated thrombosis and major bleeding, which has remained constant throughout the entire 20-year period. However, there has been no increase in bleeding events during the recent years of analysis. Trends are presented with adjustments made using a moving average. DVT = deep vein thrombosis; PE = pulmonary embolism; RIETE = Registro Informatizado de la Enfermedad Trombo Embólica.

The possible reasons behind the increase in PE and upper extremity DVT are not clear. Several hypotheses could explain these results. One possibility is the potential increase in the use of central catheters during the study period, which might contribute to an increased risk of upper limb thrombosis.21

Concerning the increase in the number of PEs, technological improvements, such as the widespread use of multidetector CT, could also play a role. Previous studies have shown that such technological improvements might account for part of the rise in diagnosed PEs.22,23

From 2001 to 2005, the proportions of patients developing VTE recurrences or major bleeding within 30 days were similar, each at 3.1%. However, the progressive decrease in VTE recurrences (0.94 per year) was more pronounced than the decrease in major bleeding (0.98 per year). The decrease in fatal PE (0.89 per year) was also higher than the decrease in fatal bleeding (0.91 per year). Consequently, during the 2016 to 2020 period, the proportion of patients developing VTE recurrences within the first 30 days was half that of patients with major bleeding (1.1% vs 2.2%, respectively). Similarly, although the rate of fatal PE in 2001 to 2005 was more than 2-fold higher than that of fatal bleeding (2.5% vs 1.1%, respectively), both rates were similar in the 2016 to 2020 period (0.6% vs 0.4%).

In other words, if the major challenge in cancer patients with VTE 20 years ago was to prevent fatal PE and VTE recurrences, the current major challenge should be to avoid major (and fatal) bleeding without compromising treatment efficacy. Promising anti–factor XI drugs24 are expected to offer improved safety benefits while maintaining similar efficacy. Ongoing studies in the field of cancer-associated VTE will likely assess these compounds. Another key element involves identifying high-risk patient subgroups for bleeding events, including potential bleeding sites, and monitoring them closely.25

There could be several potential explanations for the reduction in recurrent VTE events, bleeding events, and mortality over time. During the 20 year-study period, there was a progressive increase in patients initially presenting with PE, having metastases, or using corticosteroids or antiplatelet therapies. There also was a progressive decrease in patients with renal insufficiency. However, the progressive decrease in adverse outcomes was consistently observed in patients initially presenting with PE and those with isolated DVT. The reduced all-cause mortality rates (and possibly some of the reduction in VTE recurrences and bleeding) may be also attributable to effective cancer therapies, including the increased use of radiation therapy and immunotherapy in more recent years.26 Moreover, the increasing use of various therapies and interventions, including DOACs, pulmonary embolectomy, and mechanical thrombolysis, was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the rates of death, nonfatal VTE recurrences, and nonfatal major bleeding. Although this study does not imply causality, the decline in VTE-specific and treatment-related complications may reflect the more widespread use of therapies shown in trials and meta-analyses to lower the risk of VTE recurrences and bleeding complications. LMWH has been shown to be more efficient than VKAs in preventing recurrent VTE,27 and DOACs have demonstrated greater efficiency than dalteparin.12 Using administrative claims, Ording et al28 also found a progressive decrease in 30-day mortality (from 15.1% in 2006-2008 to 12.7% in 2015-2017) in 8,167 Danish patients with cancer-associated VTE. However, that study was unable to estimate VTE recurrences or bleeding rates or event rates for fatal PE and fatal bleeding. To our knowledge, the current study is the largest and most comprehensive study reporting the trends in presentation and outcomes specifically for cancer-associated VTE.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, we could not control for certain potential confounders, such as specific cancer details, biomarkers, lifestyle factors, or the use of central vein catheters or surgery within the first 30 days. It is possible that these variables may have influenced event rates. Additionally, the RIETE registry did not systematically collect information on race, which may be a relevant factor. Second, the generalizability of our findings should be considered, and caution should be exercised in extrapolating the results to centers with limited resources. However, it is important to note that the RIETE registry has enrolled patients from 27 countries, including a diverse range of local, regional, and referral hospitals. Third, the data from randomized trials suggesting the safety and efficacy of DOACs in various subgroups of patients with cancer have only emerged recently, and updates by regulatory authorities or guideline committees require additional time. This, along with reservations for use of DOACs in certain luminal cancers, may account for the limited utilization of DOACs in our study despite a growing trend in their use. As such, future analyses in subsequent years should assess whether thrombotic and hemorrhagic outcomes continue to change as clinical practice increasingly adopts DOACs. Finally, our results suggest an association between trends rather than a direct causality. We were not able to control for confounding factors, such as variations in cancer management or the diagnostic approach to VTE.

Conclusions

Our study reveals a progressive decline in the 30-day rates of VTE recurrences, major bleeding events, and death in cancer patients with VTE from 2001 to 2020. Interestingly, the decrease in VTE recurrences was more pronounced than the decrease in major bleeding events. This observation may have therapeutic consequences given that in the last 5 years the rate of major bleeding events was 2-fold higher than that of VTE recurrences. Further prospective studies are warranted to externally validate these findings and determine the best therapeutic approach moving forward.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: Over the past 20 years, the rates of VTE recurrences, major bleeding, and overall death consistently decreased in cancer patients with VTE.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: Further research is needed to confirm the recent trend toward an increased rate of major bleeding and determine the optimal management strategies to further improve morbidity and mortality.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

Dr Bertoletti has received personal fees and nonfinancial support from Aspen, Bayer, BMS-Pfizer, and Léo-Pharma and Johnson & Johnson; and has received grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from Merck Sharp & Dohme outside the submitted work. Dr Jimenez has received grants or contracts from Daiichi-Sankyo, Sanofi, and ROVI; and has received personal fees and honoraria for lectures from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Daiichi-Sankyo, Léo-Pharma, Pfizer, ROVI, and Sanofi outside the submitted work. Dr Bikdeli is supported by the Scott Schoen and Nancy Adams IGNITE Award from the Mary Horrigan Connors Center for Women’s Health and Gender Biology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a Career Development Award from the American Heart Association (#938814). Dr Ay has received honoraria for lectures from Bayer, BMS, Daiichi-Sankyo, Pfizer, and Sanofi outside the submitted work; and has served on Advisory Boards of Bayer, BMS, Daiichi-Sankyo, Pfizer, and Sanofi. Dr Trujillo-Santos has received personal fees and honoraria for lectures from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Daiichi-Sankyo, Léo-Pharma, Pfizer, ROVI, and Sanofi outside the submitted work. Dr Sigüenza has received support for attending meetings for Sanofi, ROVI, and Viatris. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the members of the RIETE organization (see Supplemental Appendix). They also express our gratitude to Sanofi Spain, LEO PHARMA and ROVI for supporting this Registry with an unrestricted educational grant. They also thank the RIETE Registry Coordinating Center, S&H Medical Science Service, for their quality control data, logistic and administrative support and Prof. Salvador Ortiz, Universidad Autónoma Madrid, Statistical Advisor in S&H Medical Science Service for the statistical analysis of the data presented in this paper.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For a list of the coordinators of the RIETE registry as well as supplemental tables and a figure, please see the online version of this paper.

Appendix

References

- 1.Grilz E., Posch F., Nopp S., et al. Relative risk of arterial and venous thromboembolism in persons with cancer vs. persons without cancer-a nationwide analysis. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(23):2299–2307. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baddeley E., Torrens-Burton A., Newman A., et al. A mixed-methods study to evaluate a patient-designed tool to reduce harm from cancer-associated thrombosis: the EMPOWER study. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2021;5(5) doi: 10.1002/rth2.12545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ay C., Pabinger I., Cohen A.T. Cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: burden, mechanisms, and management. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117(2):219–230. doi: 10.1160/TH16-08-0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gervaso L., Dave H., Khorana A.A. Venous and arterial thromboembolism in patients with cancer. J Am Coll Cardio CardioOnc. 2021;3(2):173–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2021.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulder F.I., Horváth-Puhó E., van Es N., et al. Venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: a population-based cohort study. Blood. 2021;137(14):1959–1969. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020007338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markham M.J., Wachter K., Agarwal N., et al. Clinical cancer advances 2020: annual report on progress against cancer from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(10):1081. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haslem D.S., Van Norman S.B., Fulde G., et al. A retrospective analysis of precision medicine outcomes in patients with advanced cancer reveals improved progression-free survival without increased health care costs. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(2):e108–e119. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.011486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeSantis C.E., Lin C.C., Mariotto A.B., et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(4):252–271. doi: 10.3322/caac.21235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raskob G.E., van Es N., Verhamme P., et al. Edoxaban for the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(7):615–624. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1711948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agnelli G., Becattini C., Meyer G., et al. Apixaban for the treatment of venous thromboembolism associated with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1599–1607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young A.M., Marshall A., Thirlwall J., et al. Comparison of an oral factor xa inhibitor with low molecular weight heparin in patients with cancer with venous thromboembolism: results of a randomized trial (SELECT-D) J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(20):2017–2023. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.8034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Planquette B., Bertoletti L., Charles-Nelson A., et al. Rivaroxaban vs dalteparin in cancer-associated thromboembolism: a randomized trial. Chest. 2022;161(3):781–790. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farge D., Frere C., Connors J.M., et al. 2019 international clinical practice guidelines for the treatment and prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(10):e566–e581. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30336-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konstantinides S.V., Meyer G., Becattini C., et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS) Eur Heart J. 2020;41(4):543–603. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens S.M., Woller S.C., Baumann Kreuziger L., et al. Executive summary: antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: second update of the CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel report. Chest. 2021;160(6):2247–2259. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Key N.S., Khorana A.A., Kuderer N.M., et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(5):496–520. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ortel T.L., Neumann I., Ageno W., et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Blood Adv. 2020;4(19):4693–4738. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiménez D., de Miguel-Díez J., Guijarro R., et al. Trends in the management and outcomes of acute pulmonary embolism: analysis from the RIETE registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(2):162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morillo R., Jiménez D., Aibar M.A., et al. DVT management and outcome trends, 2001 to 2014. Chest. 2016;150(2):374–383. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bikdeli B., Jimenez D., Hawkins M., et al. Rationale, design and methodology of the Computerized Registry of Patients with Venous Thromboembolism (RIETE) Thromb Haemost. 2018;118(1):214–224. doi: 10.1160/TH17-07-0511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Decousus H., Bourmaud A., Fournel P., et al. Cancer-associated thrombosis in patients with implanted ports: a prospective multicenter French cohort study (ONCOCIP) Blood. 2018;132(7):707–716. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-03-837153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehdipoor G., Jimenez D., Bertoletti L., et al. Patient-level, institutional, and temporal variations in use of imaging modalities to confirm pulmonary embolism. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13 doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.120.010651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiener R.S., Schwartz L.M., Woloshin S. Time trends in pulmonary embolism in the United States: evidence of overdiagnosis. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(9):831–837. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poenou G., Dumitru T.D., Lafaie L., et al. Factor XI inhibition for the prevention of venous thromboembolism: an update on current evidence and future perspectives. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2022;18:359–373. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S331614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bikdeli B., Moustafa F., Nieto J.A., et al. Clinical characteristics, time course, and outcomes of major bleeding according to bleeding site in patients with venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2022;211:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2022.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Topalian S.L., Weiner G.J., Pardoll D.M. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(36) doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0899. 4828-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahale L.A., Tsolakian I.G., Hakoum M.B., et al. Anticoagulation for people with cancer and central venous catheters. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6(6):CD006468. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006468.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ording A.G., Skjøth F., Søgaard M., et al. Increasing incidence and declining mortality after cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: a nationwide cohort study. Am J Med. 2021;134(7):868–876.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.